Introduction

Anterior minimally invasive surgery (AMIS) has gained worldwide acceptance as an approach that minimises soft-tissue damage and facilitates rapid functional recovery [

1]. Because exposure and manoeuvrability on the femoral side are inher-ently limited in AMIS, the use of relatively short femoral stems is essential. In cementless total hip arthroplasty (THA), short stems have been clinically proven to attenuate stress shielding and optimise bending behaviour [

2]. By contrast, the potential advantages of stem shortening in cemented fixation remain uncertain because the load-transfer mechanism differs fundamentally.

The AMIS-K stem was created by shortening the polished tapered Charnley–Marcel–Kerboull (CMK) design by approxi-mately 17 % while retaining a proximal collar, thereby enhancing its compatibility with AMIS. Although reducing AMIS-K length to 83 % of the original maximises shoulder-region bending resistance and diminishes micromotion in normal-bone composite models, the implications of this modification for osteoporotic bone remain unexplored.

As the global population ages, THA is increasingly performed in older patients. Most biomechanical investigations have relied on young, high-density bone specimens [

3], failing to capture the fracture risk posed by osteoporosis [

4]. Peripros-thetic fracture (PPF) is a major complication after THA, and clarifying its mechanism—and mitigating its risk—requires experiments that employ osteoporotic bone models [

5].

Clinically, cemented THA with the CMK stem has demonstrated a low early PPF incidence (0.48 %) in patients aged ≥ 70 years [

6]. Biomechanical studies using normal-bone composites have further shown that the CMK stem provides greater fracture resistance than the collarless polished tapered (CPT) and Versys Advocate stems [

7]. Nevertheless, no study has directly compared the fracture resistance of the collar-equipped, short AMIS-K stem with that of its longer CMK pre-decessor in an osteoporotic bone model. The aim of this study was to compare, in an osteoporotic composite femur model, the fracture resistance of the collar-equipped, short cemented AMIS-K stem with that of the longer CMK stem, thereby providing biomechanical evidence to support the use of short cemented stems and to inform strategies for reducing the risk of PPF.

Materials

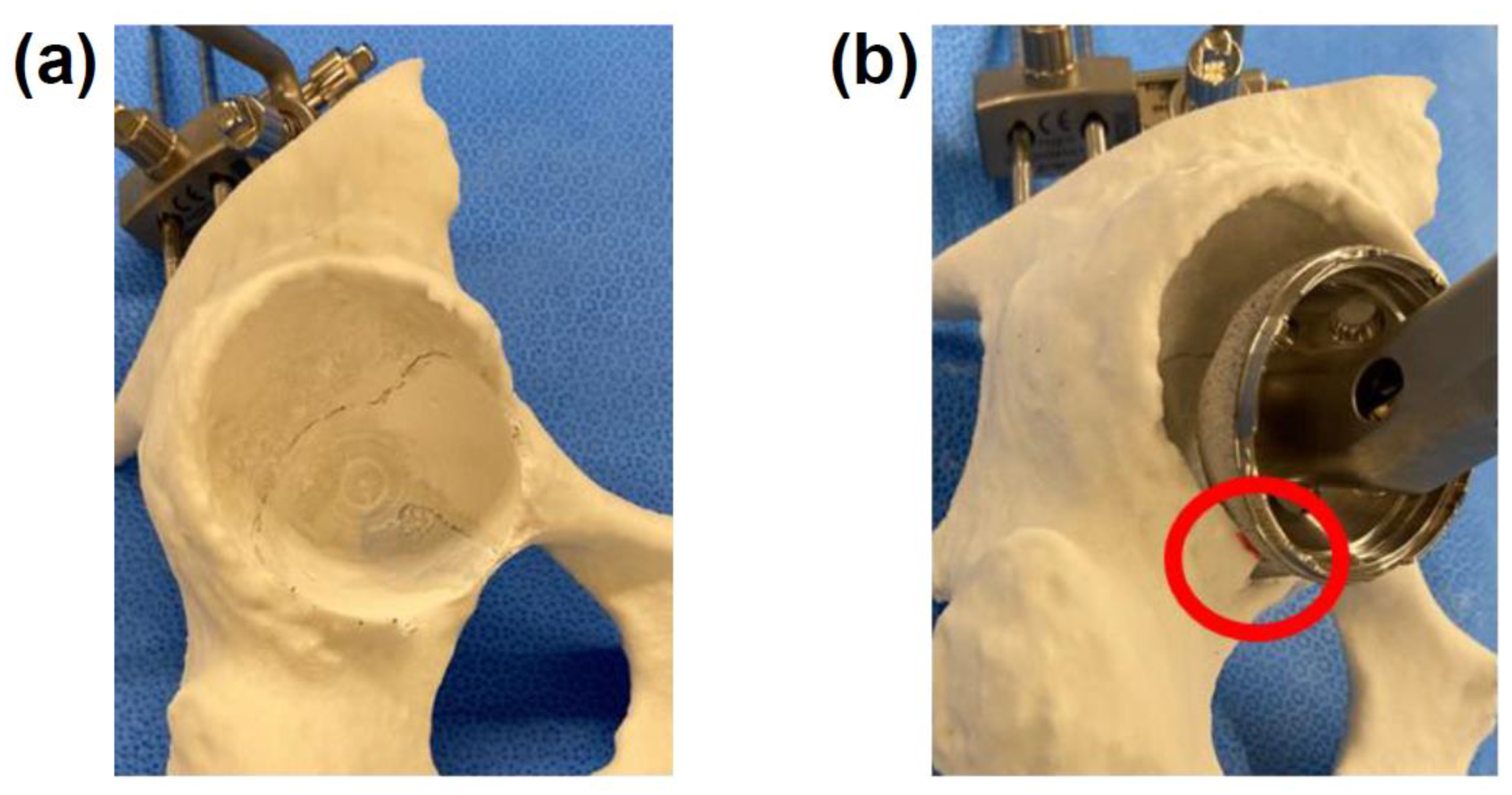

We used two types of stems (

Figure 1a,b). The CMK stem (Zimmer Biomet Valence, Franch) is designed to achieve a press-fit fixation in the anterior-posterior plane with a self-centering effect. The CMK stem has a polished surface with a collar. On the other hand, AMIS-K (Medacta international S.A. Castel San Pietro, Switzerland) stem features a tri-ple-tapered design and reduced lateral flare.

We constructed femoral bone models by cementing each stem into Sawbone models with six samples, which had been calculated by power analysis [

8], for each stem type (Sawbones medium left femur osteoporosis model 3503; Pacific Research Laboratories, USA). Sample size calculation was conducted through power analysis based on a previous biome-chanical study by Morishima et al. (2014), with parameters including an expected effect size (difference in fracture torque) of 40 N·m, standard deviation of 20 N·m, statistical power (1-β) of 80%, and significance level (α) of 0.05. This analysis determined that six samples per stem type were necessary to detect statistically significant differences in fracture resistance while maintaining adequate statistical power. Both CMK and AMIS-K stems were designed and made by an experienced Orthopedic surgeon on this model (TM, the last author). The ABG II centralizer was used for each stem. Eighty gram (g) of Simplex (Stryker Orthopedics, USA) for AMIS-K stem and 80 g of Optipack (Zimmer Biomet, USA) for CMK stem were used, and fixed on Sawbones. Simplex is a medium-viscosity cement product from Stryker. Optipack is a high-viscosity cement product from Zimmer. We mixed the monomer powder and polymer liquid under vacuum conditions for use. The cement hardening time was approximately 10 minutes at a room temperature of 21°C. All stems were inserted with 20 de-grees of anteversion and neutral varus/valgus alignment, using the central axis of the distal tapered portion of the stem as the reference. Anteroposterior and lateral radiographs were examined to confirm that the alignment was within ±1 degree of the intended position.

Those systems were applied torque and axial load to the femoral bones using an Instron machine to mimic frac-ture patterns and defined the maximum measured torque as the fracture torque.

Mechanical Loading Test

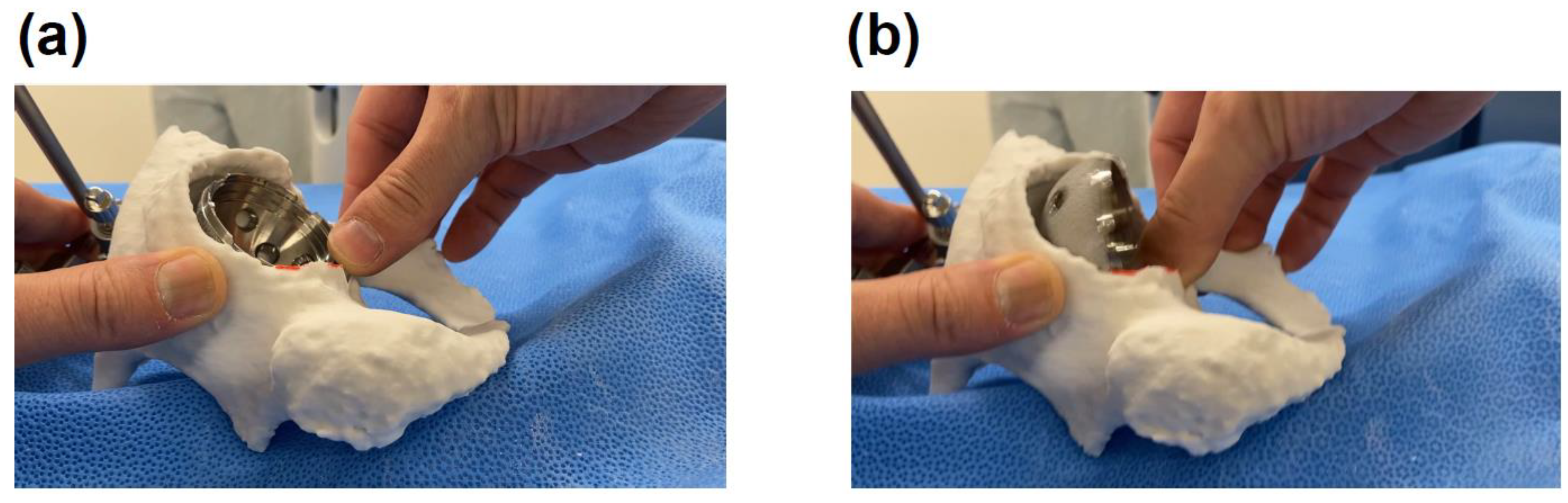

After CT scanning, the Sawbone and designing models based on the CT data, models were created to match the design concepts of both stems. We conducted compression- torsion tests using a CMH Biaxial Material Test System (SAGINOMIYA SEISAKUSHO, Japan). This system allows the performance of a combination test with axial stress and torsional stress by adding biaxial forces to a test piece simultaneously. The phase between the forces can also be freely con-trolled. The proximal femur was held by a mechanical clamp at the center of rotation of the implant head. We set the vertical loading axis of the machine through the center of the femoral head and the inter-condylar notch. The distal end of femur was fixed with special device (

Figure 2.). The femora were tested using combined compression force with torque to imitate fracture patterns in the femora. A preload of 2 N·m in the internal rotation direction and 2kN of compression were applied as previously described [

8,

9]; (

Figure 2.). The compressive load was then maintained, and the implant was internally rotated 40° in one second. Internal rotation of 40° was applied over a period of 1 second constantly. This angle was chosen fol-lowing the methodology established by Morishima et al. [

8] in their similar biomechanical study on cemented stems. The primary purpose of selecting this specific angle was to ensure complete fracture occurrence in all specimens, which is es-sential for reliable measurement of maximum torque values and consistent fracture pattern analysis.

The angle of 40° was determined through preliminary testing to be sufficient to induce complete fracture in our experi-mental model while maintaining consistency across all specimens. Our testing protocol prioritized comparative evaluation between the two stem designs under identical controlled conditions rather than replicating exact in vivo loading scenarios. Fracture torque was defined as the maximum torque measured. We recorded the fracture pattern in reference to the Vancou-ver classification [

10]. Three orthopaedic surgeons independently evaluated the fracture patterns. Their assessments were identical across all specimens.

Statistical Analysis

JMP 14 SAS for Macintosh was used for statistical analyses. Since nonparametric approach was needed due to the non-normal distribution of data in this study, Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon tests were performed. The primary end-point was fracture torque, and p value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Boxplot displays that midlines were median.

Results

Fracture torque

The mean fracture torque was 94.0 N·m (SD 2.4) for AMISK 4S3 and 93.0 N·m (SD 7.6) for CMK 303. The 95% confidence intervals were 91.5-96.5 N·m for AMISK 4S3 and 85.1-101.0 N·m for CMK 303. The standardized effect size (Cohen’s d) was 0.16, indicating a small effect. The p-value from our non-parametric test (p=0.94) showed no significant difference between the stems, with statistical significance set at p<0.05. (

Figure 3.)

Fracture Pattern

The fractures were spirally shaped, and the degree of fracture comminution varied. We observed failure at the cement-bone interface in all cases. The AMIS-K stem showed 1 comminuted oblique fracture of Vancouver type B2 and 5 type C at the tip of the stem. The CMK stem showed 5 comminuted oblique fracture of Vancouver type B2 and 1 type C at the tip of the stem.

Discussion

Cemented stems remain popular and provide excellent long-term results in THA for decades. This study revealed that the fracture torque of AMIS-K stem showed comparable results to those of CMK stem. Note that CMK stem has been widely used with a reputation for stability and fracture resistance. The AMIS-K stem demonstrated similarly good fracture torque, suggesting it may offer equivalent mechanical stability.

Hamadouche et al. reported improved overall fixation when shortening the AMIS-K stem to the limit of accepta-ble maximum torque transfer, concluding that shorter stems are beneficial [

3]. However, this research was conducted under a single condition, where bone length and strength likely significantly influenced the results.

Conversely, Morishima et al. reported contradictory findings, indicating that shorter stems present higher fracture risks [

8]. In our study, we used the AMIS-K stem, which is shorter than the CMK, and achieved comparable results.

Importantly, while Hamadouche et al. simply concluded that ‘shorter stems are beneficial,’ our proposal is more specific. We suggest that shortening the stem itself should not be the primary objective; rather, when using shorter stems, increasing the proximal volume is essential to maintain or enhance fracture resistance. This finding indicates that in stem selection, not only the length but also the shape and volume of the proximal portion are particularly important for reducing fracture risk. Furthermore, our experiments utilized an osteoporosis model, which likely provided results more closely ap-proximating clinical scenarios.

Consequently, AMIS-K stem is comparable to reduce risks of PPF in THA.

In

Figure 3, the AMIS-K stem showed smaller variability in fracture torque, indicating more consistent mechanical perfor-mance. Although both stems have similar overall designs—with polished surfaces and collars—the CMK stem is slightly longer, while the AMIS-K stem has a larger proximal volume.

Both stem length and proximal volume are known to contribute to fracture resistance. However, in this study, the AMIS-K stem with greater proximal volume demonstrated more consistent fracture torque values, suggesting that proximal load transfer may have been more stable and less influenced by variations in stem alignment or cement mantle quality.

In contrast, the longer CMK stem may have transmitted more load distally, making the fracture resistance more sensitive to small differences in positioning or cementation, which could explain the greater variability observed.

These findings suggest that a larger proximal volume may contribute not only to higher fracture resistance, but also to its consistency, and could be a valuable design feature in cemented stem development.

Kaneuji et al. reported that cobalt–chromium (CoCr) polished taper-slip stems exhibit greater subsidence than stainless-steel stems, potentially increasing the risk of periprosthetic fracture (PPF) through excessive sliding at the stem–cement interface [

11]. In contrast, Jain et al., using CPT and Exeter stems, demonstrated that neither stem alloy nor geome-try had a significant effect on resistance to fracture torque [

12]. Furthermore, Hashimoto et al. suggested that when stem size is appropriately optimized, the influence of alloy composition may be effectively masked [

13].

In the present study, the two cemented stems evaluated—AMIS-K (high-nitrogen stainless steel, ISO 5832-9) and CMK (M30NW stainless steel)—belong to the same stainless-steel family but differ in alloy grade. Although the influence of material composition cannot be completely ruled out, both stems were implanted in optimally sized configurations, which likely minimized the relative impact of material differences.

Jain et al. previously have reported on the torque power with cemented polished taper-slip (CPT) stem using os-teoporotic bone model, which is the same bone model as ours [

12]. They conclude that the mechanical resistance to PPF is not affected by stem material or stem geometry using CPT stem and another major polished taper-slip stem, Exeter. Their data show the mean fracture torque, which was 72.88 N·m for the CPT stem, while the mean torque power of CMK stem was 80.1 N·m in our model. In total, CMK stem could have better fracture resistance than that of CPT stem [

12].

PPF is a typical complex complication of cemented THA, which is usually treated by surgery. It likely causes re-duced function, subsequent morbidity, and increased mortality [

14]. Osteoporosis is a well-known and may be one risk factor to cause PPF after THA as described previously [

15]. Even though they have described that osteoporosis can pre-dispose aged patients to developing postoperative fractures, the mechanism is largely unknown. Our osteoporotic femoral bone model clarified the differences in fracture torque and fracture types between 2 different major cemented stems, AMIS-K and CMK stems, in biomechanical study. As a result, there was no significant difference in fracture torque of AMIS-K stem, compared to the CMK stem (p = 0.94). Thus, our findings suggest that AMIS-K stem may be also a reason-able option to reduce the PPF risks in THA.

The present study has several limitations. First, although synthetic bones provide excellent reproducibility and controlled testing conditions, they do not replicate the biological variability found in human femurs, such as differences in bone den-sity, microstructure, and material properties. This limitation should be acknowledged when interpreting our results. The use of cadaveric specimens, while potentially more representative of clinical scenarios, presents significant challenges in main-taining experimental control due to inherent variability between specimens. The standardized nature of synthetic bones was essential for isolating the mechanical variables under investigation in this study. Second, it is important to acknowledge that this study utilized synthetic femurs of a single standardized size and morphology. The length and shape of the femur likely influence fracture biomechanics and periprosthetic fracture patterns. The lack of morphological variation in our ex-perimental model represents a limitation, as clinical scenarios involve diverse femoral geometries. Future research should investigate how differences in femoral length, canal diameter, cortical thickness, and overall morphology might affect the mechanical properties and fracture patterns observed in this study. Third, we discarded the influence of the soft-tissue en-velope in our model. Fourth, we investigated only 2 different types of cemented stems. Fifth, we showed the fracture torque of compressive torsion, but not other mechanisms, such as torsion, bending, and direct impact. Future studies would be needed to confirm our findings. Sixth, our study used different cements based on manufacturer availability (manufactur-er-specific cement when available, and Stryker cement otherwise). While all cements used were of high or middle viscosity, which have shown comparable clinical outcomes unlike low viscosity cements that increase PPF risk, we cannot exclude the possibility that variations in cement properties and their interactions with different stem designs or metals may have influenced our results. Further research controlling for cement type would be valuable to isolate the mechanical effects of stem design alone.

Conclusions

AMIS-K stem showed great fracture resistance, which was equivalent to the CMK stem, suggesting that proximal volume may play a significant role in fracture resistance.

Author Contributions

Kohei Hashimoto: Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Validation, Data curation, Writing—original draft, review and editing. Yukio Nakamura: Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Validation, Data curation, Writing—original draft, review and editing, Visualization. Nobunori Takahashi: Investigation and Supervi-sion. Takkan Morishima: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Validation, Data curation, Writ-ing—original draft, review and Project administrati.

Funding

This study did not receive any specific grants from public, commercial, or nonprofit funding agencies.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study has been performed in accordance with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments, and approved by the ethical committee of Aichi Medical University.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was waived due to its retrospective nature along with the name of the institu-tion by which it has been waived.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed and presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Faldini C, Rossomando V, Brunello M, D’Agostino C, Ruta F, Pilla F, Traina F, Di Martino A. Anterior Minimally In-vasive Approach (AMIS) for Total Hip Arthroplasty: Analysis of the First 1000 Consecutive Patients Operated at a High Volume Center. J Clin Med. 2024 Apr 29;13(9):2617. [CrossRef]

- Barbier O, Rassat R, Caubère A, Dubreuil S, Estour G. Short-stem total hip arthroplasty is equivalent to a stand-ard-length stem procedure in an unselected population at mid-term follow-up. Int Orthop. 2024 Apr;48(4):1017-1022. [CrossRef]

- Hamadouche M, Jahnke A, Scemama C, Ishaque BA, Rickert M, Kerboull L, Jakubowitz E. Length of clinically prov-en cemented hip stems: state of the art or subject to improvement? Int Orthop. 2015;39:411-6.

- Rachner TD, Khosla S, Hofbauer LC. Osteoporosis: now and the future. Lancet. 2011 Apr 9;377(9773):1276-87.

- Palan J, Smith MC, Gregg P, Mellon S, Kulkarni A, Tucker K, Blom AW, Murray DW, Pandit H. The influence of ce-mented femoral stem choice on the incidence of revision for periprosthetic fracture after primary total hip arthroplasty: an analysis of national joint registry data. Bone Joint J. 2016 Oct;98-B(10):1347-1354.

- Laboudie P, Hallé A, Anract P, Hamadouche M. Low rate of periprosthetic femoral fracture with the Hueter anterior approach using stems cemented according to the ‘French paradox’. Bone Joint J. 2024 Mar 1;106-B(3 Supple A):67-73.

- Takegami Y, Seki T, Osawa Y, Imagama S. Comparison of periprosthetic femoral fracture torque and strain pattern of three types of femoral components in experimental model. Bone Joint Res. 2022 May 6;11(5):270–277. [CrossRef]

- Morishima T, Ginsel BL, Choy GG, Wilson LJ, Whitehouse SL, Crawford RW. Periprosthetic fracture torque for short versus standard cemented hip stems: an experimental in vitro study. J Arthroplasty. 2014 May;29(5):1067-71. [CrossRef]

- Ginsel BL, Morishima T, Wilson LJ, Whitehouse SL, Crawford RW. Can larger-bodied cemented femoral components reduce periprosthetic fractures? A biomechanical study. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2015;135(4):517–522. [CrossRef]

- Brady OH, Garbuz DS, Masri BA, Duncan CP. The reliability and validity of the Vancouver classification of femoral fractures after hip replacement. J Arthroplasty. 2000;15(1):59–62. [CrossRef]

- Ayumi Kaneuji , Mingliang Chen , Eiji Takahashi , Noriyuki Takano, Makoto Fukui , Daisuke Soma ,Yoshiyuki Tachi , Yugo Orita , Toru Ichiseki and Norio Kawahara. Collarless Polished Tapered Stems of Identical Shape Provide Differ-ing Outcomes for Stainless Steel and Cobalt Chrome: A Biomechanical Study. J. Funct. Biomater. 2023, 14, 262. [CrossRef]

- Jain S, Lamb JN, Drake R, Entwistle I, Baren JP, Thompson Z, Beadling AR, Bryant MG, Shuweihdi F, Pandit H. Risk factors for periprosthetic femoral fracture risk around a cemented polished taper-slip stem using an osteoporotic com-posite bone model. Proc Inst Mech Eng H. 2024 Mar;238(3):324-331. [CrossRef]

- Kohei Hashimoto , Yukio Nakamura , Nobunori Takahashi and Takkan Morishima . Comparison of Different Materi-als in the Same-Sized Cemented Stems on Periprosthetic Fractures in Bone Models. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2724. [CrossRef]

- Lindahl H, Oden A, Garellick G, Malchau H. The excess mortality due to periprosthetic femur fracture a study from the Swedish national hip arthroplasty register. Bone. 2007;40:1294–1298.; Schmidt AH, Kyle RF. Periprosthetic fractures of the femur. Orthop Clin North Am. 2002;33:143–152. [CrossRef]

- Cook RE, Jenkins PJ, Walmsley PJ, Patton JT, Robinson CM. Risk factors for periprosthetic fractures of the hip: a sur-vivorship analysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008 Jul;466(7):1652-6.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).