1. Introduction

Searching for information is a fundamental daily necessity for humans. To meet the demand for rapid access to desired information, key web search technologies like PageRank [

1,

2,

3] have been developed to support information retrieval systems. These technologies power search engines such as Google, Bing, and Baidu, which efficiently retrieve relevant web pages in response to user queries, offering convenient access to information on the internet. Advances in natural language processing (NLP) [

4] and information retrieval (IR) [

5] have further enhanced machines’ ability to accurately extract content from the vast array of websites available online. However, as user queries become increasingly complex and the demand for precise, contextually relevant, and up-to-date responses grows, traditional search technologies encounter challenges in fully comprehending intricate human intentions. Consequently, users often need to manually open, read, and synthesize information from multiple web pages to answer complex questions.

Recently, Large Language Models (LLMs) [

6] have captured significant attention in both academic and industrial domains. LLMs such as ChatGPT [

7] and LLaMA [

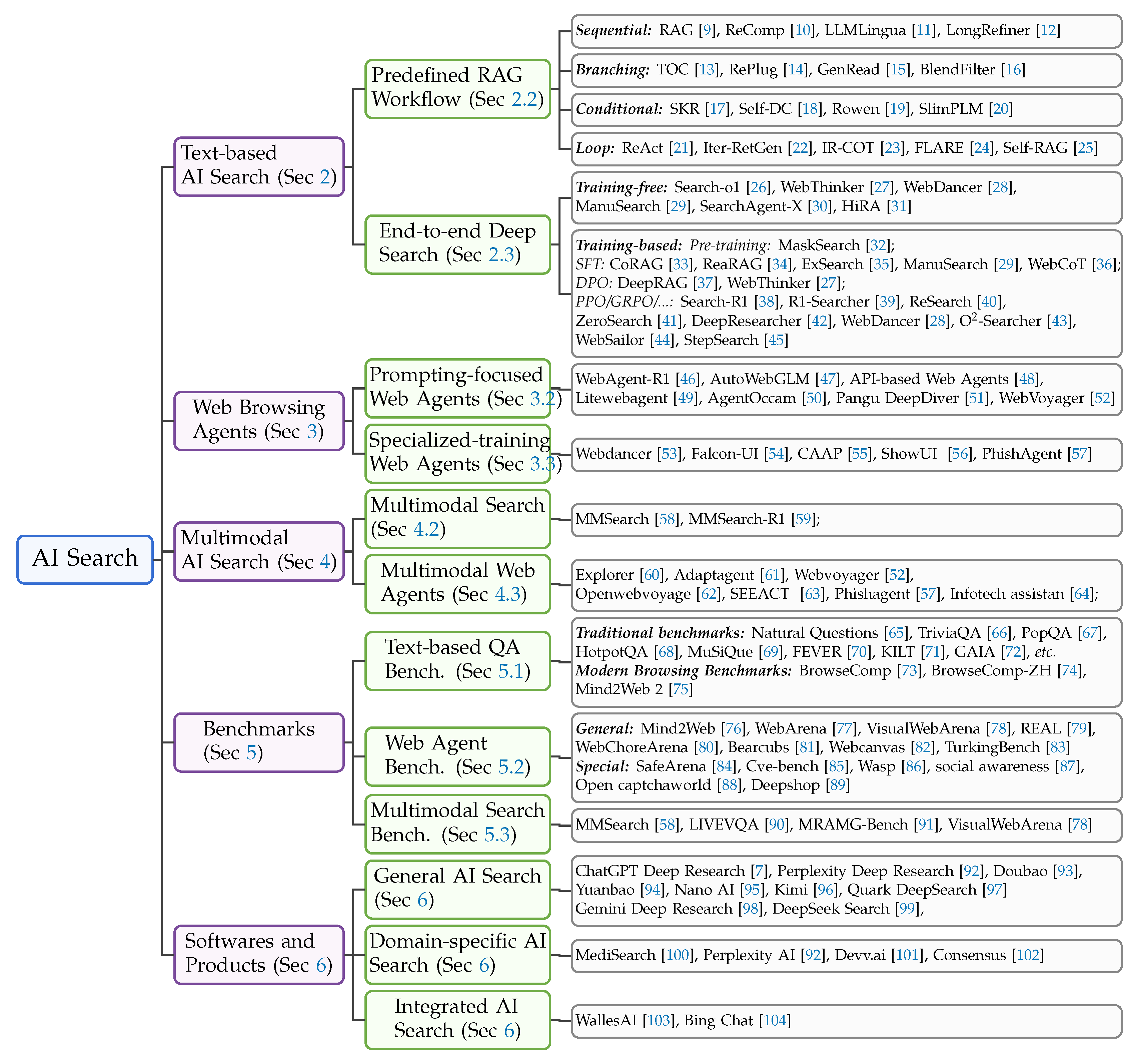

8] have demonstrated remarkable advancements in language understanding, reasoning, and information integration. However, LLMs face limitations in acquiring external knowledge and accessing the most current information. To address these challenges, researchers are integrating the impressive capabilities of LLMs with search engines and websites, aiming to enhance real-time evidence gathering and reflective reasoning. The complementary strengths of LLMs and search engines present an opportunity for synergy, where the reasoning abilities of LLMs are augmented by the vast web information accessible through search engines. This integration is revolutionizing the way we seek and synthesize web-based information, ushering in a new era of search technology known as Artificial Intelligence (AI) Search. In this survey, we provide an overview of recent advancements in the rapidly evolving field of AI Search. As depicted in

Figure 1, we categorize the literature into five primary areas: (1) text-based AI search, (2) Web browsing agents, (3) multimodal AI search, (4) benchmarks, and (5) software and products.

The classic

Text-based AI Search operates through a Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) framework [

105]. In this workflow, RAG retrieves relevant passages from search engines based on the input query and integrates them into the context of a Large Language Model (LLM) for generating responses. This enables the LLM to utilize external knowledge when addressing questions. Another approach within text-based AI Search is the deep search method, which acquires external information by interacting with search engines as part of an end-to-end coherent reasoning process to tackle complex information retrieval challenges. Unlike predefined workflows, this method allows the model to autonomously determine when to employ search-related tools during its reasoning, enhancing flexibility and effectiveness.

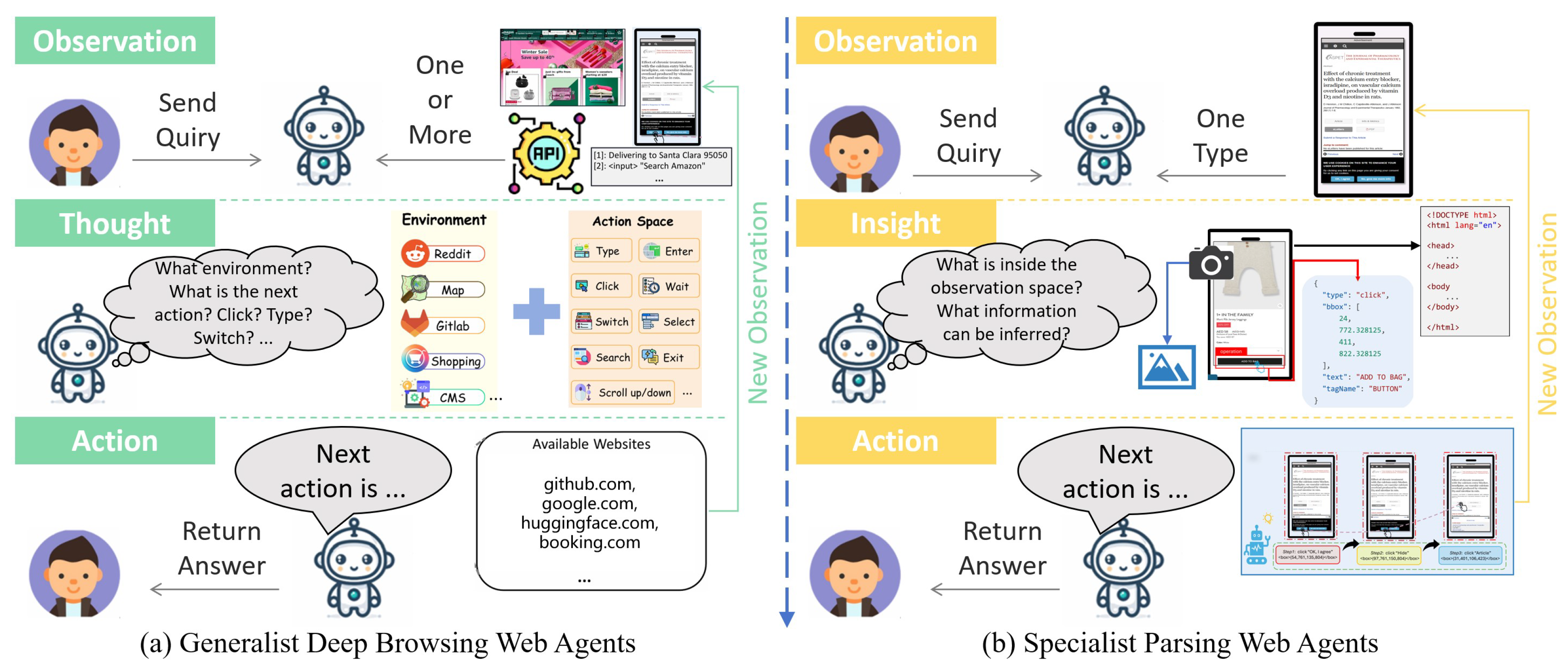

Web Browsing Agent accomplishes specific tasks on target websites through a sequence of actions, utilizing a thought-action-observation paradigm. For instance, if you want a web agent to calculate the driving time from Shanghai to Beijing using an open street map, it would perform this task by interacting with the website. Web agents are classified into two primary paths: Generalist Deep Browsing Web Agents that perform more complex web browsing tasks, especially across multiple types of web pages; Specialist Parsing Web Agents that employ dedicated training procedures to make the model focus specifically on action sequences or interface elements. Additionally, with the emergence of visual web-oriented benchmarks and the development of Multimodal Large Language Models, many agents now incorporate screenshots as sensory input to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the web environment. Unlike

Multimodal AI Search, most current AI search methods are confined to text-only settings, overlooking the multimodal nature of user queries and the intertwined text-image information on websites. This limitation is particularly significant given the complexity and interleaved nature of modern websites. For example, imagine capturing a photo of an antique at a museum without knowing its historical context. A multimodal AI search engine could match the photograph with an interleaved table of images and text retrieved from the Internet, thereby providing you with the history and story behind it. Thus, a multimodal AI search engine is essential for advancing information retrieval and analysis.

Furthermore, this paper offers a review of the

Benchmarks relevant to these methods. Evaluating the search capabilities of AI models, particularly large language models (LLMs), is crucial for assessing their ability to effectively retrieve, filter, and reason over web-based information. This evaluation is essential for understanding the true web-browsing competence of LLMs and their potential to tackle real-world tasks that demand dynamic information retrieval. In recent years, significant efforts have been made to explore AI search from various perspectives. This paper concentrates on three key areas: text-based question-answering benchmarks, web agent benchmarks, and multimodal benchmarks. The

Software and Products of AI Search, such as Perplexity [

92], have the potential to change our daily lives. We introduce a wide array of state-of-the-art open-source and proprietary models, software, and mainstream AI search products, aiming to present a diverse and comprehensive overview of AI Search. Finally, we discuss the limitations of current AI search methods and explore promising future directions. To illustrate the evolution of AI search methods over time,

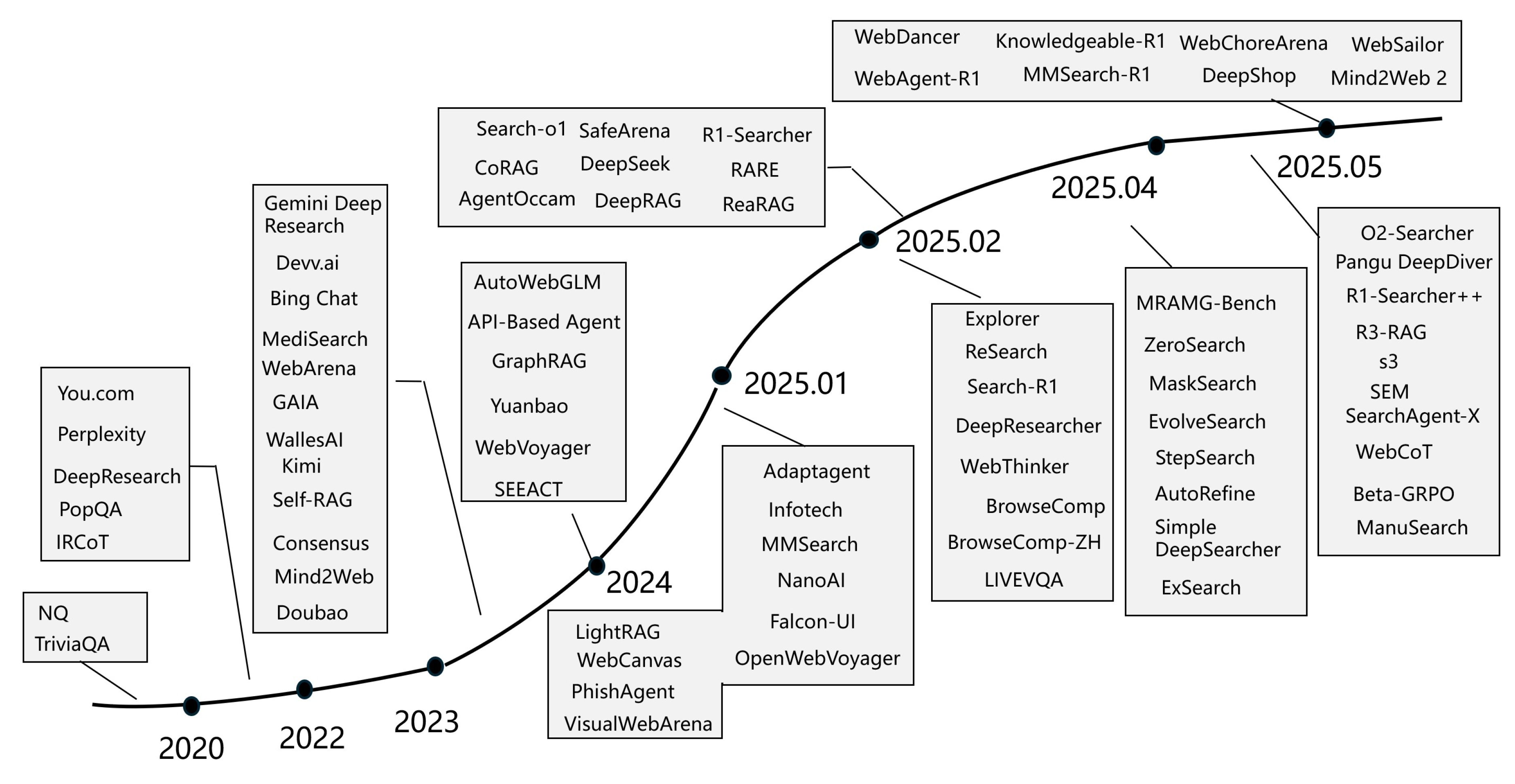

Figure 2 presents a timeline of recent AI search technologies, related methods, and products.

2. Text-Based AI Search

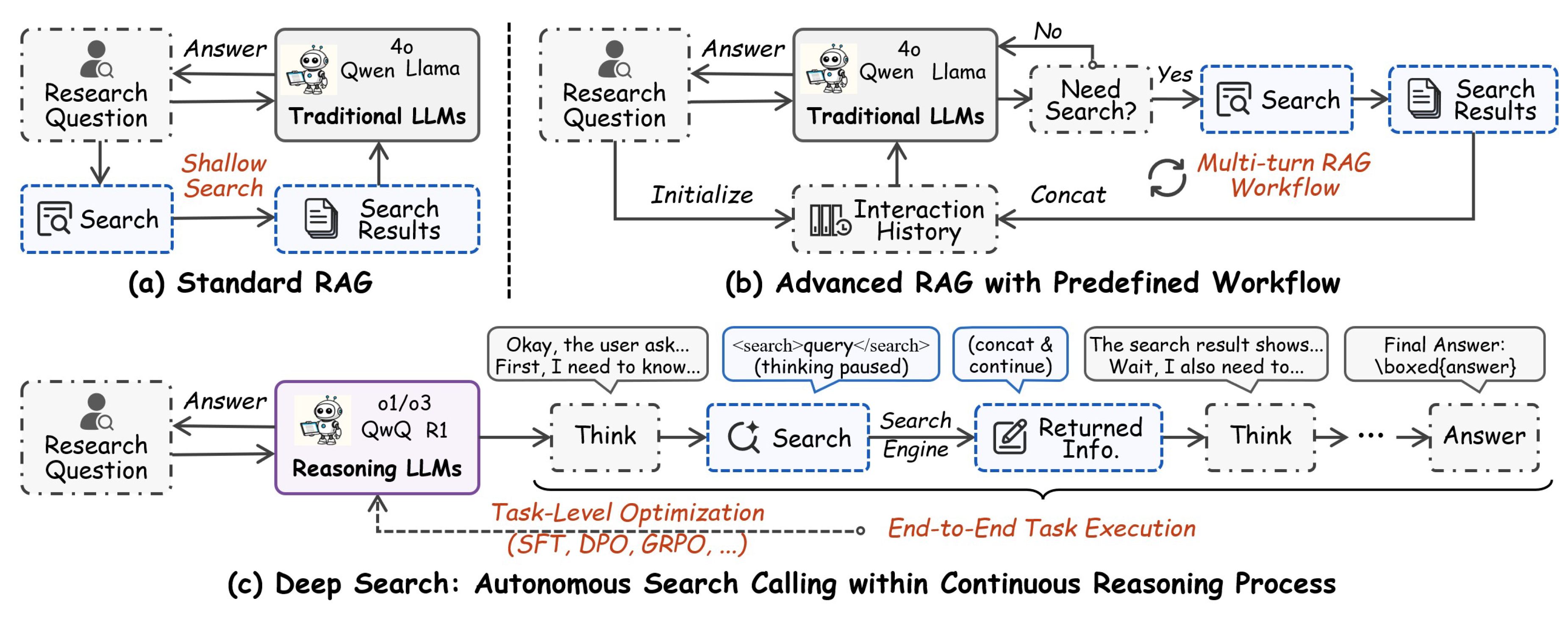

AI search represents a transformative advancement in information retrieval systems, evolving from traditional search engines to sophisticated approaches incorporating RAG workflows and Deep Search capabilities, as shown in

Figure 3. This section provides an overview of the key components and cutting-edge developments in modern text-based AI search technologies.

2.1. Traditional Search Engines

Traditional search engines form the backbone of modern search engines. They employ a variety of techniques to efficiently process user queries and return relevant results. Two key components of these systems are document retrieval and post-ranking, which work in tandem to provide users with the most pertinent information [

106].

Document Retrieval.

Document retrieval is the process of identifying relevant documents from a collection based on a user query. It is a crucial step in information retrieval, as it determines which documents are most relevant to the user’s query. Traditional document retrieval systems typically employ techniques like inverted indexing, term frequency-inverse document frequency (TF-IDF), and BM25 models [

107,

108]. More advanced approaches incorporate semantic matching using dense vector representations and neural ranking models [

109,

110,

111,

112]. The retrieval process often involves query preprocessing, document indexing, similarity computation, and efficient search algorithms to handle large-scale document collections. In recent years, some work has explored LLM-based generative retrieval [

113,

114,

115,

116], eliminating the need to build document indexes and directly generating document identifiers through LLMs.

Post-Ranking.

Post-ranking is the process of refining the results of a search query after the initial retrieval stage. It is used to improve the quality of the search results by applying additional filters and reranking algorithms. Post-ranking systems typically employ learning-to-rank algorithms, neural reranking models, and LLM-based reranking models that combine multiple ranking signals [

117,

118,

119]. This stage is crucial for improving search precision and user satisfaction by promoting the most relevant documents to top positions [

117].

2.2. Retrieval-Augmented Generation with Pre-defined Workflows

Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) enhances generative models by integrating a retrieval mechanism, allowing the model to ground its responses in external, reliable knowledge [

9,

120]. Typically, a RAG system consists of a retriever and a generator, and the interaction between these components gives rise to four main RAG paradigms [

105]:

Sequential RAG.

Sequential RAG follows a linear “retrieve-then-generate” workflow, where the retriever first fetches relevant documents and the generator produces the final response based on these documents [

9,

120,

121,

122,

123,

124]. Early works explored joint or separate training of the retriever and generator, while recent approaches often use a frozen generator and focus on optimizing the retriever [

125,

126,

127]. Pre-retrieval modules (e.g., rewriters [

123]) and post-retrieval compressors [

10,

11,

12,

128,

129,

130] further improve efficiency and response quality.

Branching RAG.

Branching RAG processes the input query through multiple parallel pipelines, each potentially involving its own retrieval and generation steps, and then merges the outputs for a comprehensive answer [

13,

14,

15,

16]. This approach enables finer-grained handling of complex queries, such as decomposing questions into sub-questions [

13], augmenting queries with additional knowledge [

16], or merging generated and retrieved content [

14,

15].

Conditional RAG.

Conditional RAG introduces a decision-making module to adaptively determine whether retrieval is necessary for a given query, improving flexibility and robustness [

17,

18,

19,

20]. Methods include training classifiers to predict the need for retrieval [

17,

20], using model confidence to guide retrieval [

18], or employing consistency checks across perturbed queries [

19].

Loop RAG

Loop RAG features iterative and interactive retrieval-generation cycles, enabling deep reasoning and handling of complex queries [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

131,

132]. These methods alternate between retrieval and generation [

22,

23], dynamically decide when to retrieve [

24,

25], or decompose and answer sub-questions with verification steps to reduce misinformation [

131,

132].

2.3. End-to-end Deep Search within Reasoning Process

Unlike traditional RAG workflows, Deep Search methods acquire external knowledge by calling search engines within an end-to-end coherent reasoning process to solve complex information retrieval problems. This approach does not require predefined workflows; instead, the model autonomously decides when to invoke search-related tools during its reasoning process, making it more flexible and effective [

133,

134,

135].

Training-Free Methods

These methods aim to enhance the reasoning model’s search capabilities by designing instructions that make the model aware of its task and how to use search tools. Initially, Search-o1 [

26] proposed an agentic RAG mechanism that allows the reasoning model to autonomously retrieve external knowledge when encountering uncertain information during the main reasoning process, addressing the knowledge gaps in long Chain-of-Thought (CoT) reasoning. They also introduced a Reason-in-Documents process, which deeply analyzes the content of retrieved documents after each search call in the main reasoning process, returning consice and helpful information to the main reasoning chain. Experiments demonstrated significant performance improvements across mathematical, scientific, coding, and multi-hop question answering tasks.

Following this paradigm, a series of works such as WebThinker [

27], WebDancer [

28], ManuSearch [

29] and HiRA [

31] have proposed advanced frameworks. Typically, these methods introduce browsing of collected webpage URLs to achieve in-depth web exploration. Additionally, to improve search efficiency, SearchAgent-X [

30] proposed an efficient reasoning framework that aims to increase system throughput and reduce latency through high-recall approximate retrieval, priority-aware scheduling, and non-stagnant retrieval mechanisms. Beyond directly answering users’ information seeking questions, some works like WebThinker [

27] have explored autonomously writing research reports while gathering information, offering users more comprehensive and cutting-edge knowledge.

Training-Based Methods

These methods design various training strategies to incentivize or enhance the LLM’s search capabilities within the reasoning process. These strategies span pre-training, supervised fine-tuning (SFT), and reinforcement learning (RL).

During pre-training, the MaskSearch [

32] framework introduces a Retrieval-Augmented Mask Prediction (RAMP) task, which trains the model to use search tools to fill in masked text, thereby enhancing its retrieval and reasoning abilities.

For Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT), several methods focus on synthesizing long chain-of-thought data that incorporates search actions [

28,

29,

33,

34,

35,

36,

44,

136]. Specifically, CoRAG [

33] addresses the lack of intermediate retrieval steps in existing RAG datasets by automatically generating retrieval chains through rejection sampling. ReaRAG [

34] avoids complex reinforcement learning by building a specialized dataset for fine-tuning via policy distillation. ExSearch [

35] introduces an iterative self-incentivization framework based on the Generalized Expectation-Maximization (GEM) algorithm, enabling the model to learn from its own generated search trajectories. SimpleDeepSearcher [

136] simulates user search behavior in a real-world web environment to synthesize multi-turn reasoning trajectories, which are then curated using a multi-criteria strategy. ManuSearch [

29] leverages its multi-agent framework to decompose the deep search process and generate structured reasoning data. Lastly, WebCoT [

36] synthesizes training data by reconstructing successful and failed trajectories, explicitly embedding reasoning skills like reflection, branching, and rollback into the chain of thought.

Furthermore, RL-based training has recently garnered significant attention. Some works leverage Direct Preference Optimization (DPO) [

137]. For instance, DeepRAG [

37] introduces a chain of calibration method to refine the model’s atomic decisions, thereby synthesizing preference data for training. WebThinker [

27] constructs positive and negative pairs based on the model’s ability to correctly complete research tasks while efficiently using tools. By iteratively constructing data and training the model with DPO, it implements on-policy RL training, improving performance on complex reasoning and report generation tasks.

Another line of work has explored training strategies based on PPO [

138], GRPO [

139], REINFORCE++ [

140], and others. Initially, Search-R1 [

38], R1-Searcher [

39], ReSearch [

40], and WebSailor [

141] used the accuracy of the generated answer as a rule-based reward to encourage the LLM to use Wikipedia-based search tools during reasoning, achieving significant performance improvements in multi-hop QA tasks. Subsequently, a series of studies have investigated various enhancement strategies. These include leveraging web search capabilities [

28,

42,

44,

46,

142], refining retrieved information [

42,

43,

143], enabling multi-tool usage [

144], developing improved sampling techniques [

145], designing advanced reward functions [

146], combining outcome and process rewards [

45,

147], enhancing training efficiency [

41], and implementing iterative SFT and RL training cycles [

148]. To optimize search efficiency, methods such as SEM [

149],

-GRPO [

150], and s3 [

151] have been proposed, which design training algorithms and reward functions for more efficient and accurate use of search tools.

3. Web Browsing Agent

The Web Browsing Agent is an AI-driven autonomous program designed to mimic human interactions within web browsers. It excels in tasks like information retrieval, task execution, and adapting to dynamic environments. This section delves into the definition, classification, and cutting-edge technologies related to Web Browsing Agents and Web Agents more broadly.

3.1. Agent

Agent is a system that perceives environments, makes autonomous decisions, and executes tasks, aiming to simulate human cognition. With LLMs’ emergence, LLM-based agents have become a key research direction. The core of LLM-based autonomous agents lies in two key aspects: architecture design and capability acquisition. In terms of architecture design, researchers aim to fully leverage the powerful language understanding and generation capabilities of LLMs through various network structures and modular combinations(e.g., AgentVerse’s unified framework [

152]). Regarding capability acquisition, two primary methods are employed [

153]. First, Fine-tuning optimizes performance for specialized tasks by training the model with domain-specific data. Second, prompt engineering elicits the model’s latent capabilities through carefully designed prompts.

Building upon general agent research, Web Agents’ key distinction lies in handling the diversity and dynamism of web pages, which imposes stricter demands on perception modules and safety-aware design. Most current Web Agent frameworks adopt a Markov Decision Process (MDP) formulation [

49], where each decision step is governed by a 4-tuple (S, A, T, R): S (State Space): Represents the environment state, typically the current webpage’s HTML content. A (Action Space): Encompasses possible web interactions (e.g., button clicks, scrolling, text input). T (Transition Function): Defines how executing action A in state S alters the webpage state. R (Reward Function): Evaluates the quality of interactions to guide learning. While this MDP-based approach serves as the foundation, variants exist where steps are adapted (e.g., simplified or extended) based on practical requirements.

Based on the adopted training strategies, current Web Agents can be categorized into two types shown in

Figure 4: Generalist Deep Browsing Web Agents that enhance the model’s ability to perform more complex web browsing tasks, especially across multiple types of web pages; Specialist Parsing Web Agents that employ dedicated training procedures to make the model focus specifically on action sequences or interface elements [

154].

3.2. Generalist Deep Browsing Web Agents

Due to the open-ended nature of Web Agent applications, conventional static dataset-based training methods exhibit significant limitations, particularly when handling complex web navigation tasks. To enhance Web Agent capabilities in such scenarios, it is crucial to dynamically prompt the model during training to facilitate optimal action selection in corresponding situations. Reinforcement learning (RL) has become a key technology that enables web agents to adapt to dynamic environments in real-time through exploration and interactive feedback.

For instance, WebAgent-R1 is the first purely end-to-end RL-trained Web Agent [

46]. It employs a multi-turn end-to-end RL framework, where the agent is trained through online interactions guided by rule-based outcome rewards. During training, it extends the standard Group Proximal Policy Optimization (GRPO) method into Multi-Group GRPO [

155], utilizing multiple parallel interaction trajectories to enhance training efficacy. Additionally, WebAgent-R1 implements dynamic context compression for the state space (S) in the Markov Decision Process (MDP). When a new state arrives, earlier states are simplified to reduce context length while preserving complete history, thereby minimizing memory consumption. AutoWebGLM adopts a multi-stage training approach, integrating Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT), RL, and Rejection Sampling Fine-Tuning (RFT) [

47]. And it retains erroneous samples during training to facilitate learning from mistakes. Microsoft proposed an “API-first” Web Agent based on the CodeAct architecture [

48], which replaces traditional browser interactions with API calls and selectively accesses browser APIs to retrieve feedback. For websites with limited APIs, the agent directly incorporates complete API documentation into its prompts. For websites with extensive APIs, it first generates a dictionary mapping each API to its documentation and then filters relevant APIs based on task descriptions. This dynamic approach enhances adaptability, with API-based prompts proving more concise and effective than direct browsing. AgentOccam simplifies the action space (A) by replacing multiple operations with functionally equivalent single actions and abstracting knowledge-dependent operations [

50]. And it yields a streamlined yet effective Web Agent workflow by reducing the state space (S) by merging repetitive elements or structures and selectively replaying historical information.

Fine tuning before RL is also critical. This process establishes basic web interaction skills in the action space A. The result of the process directly affects the effect of reinforcement learning in the later stage. For example, Huawei’s Pangu DeepDiver integrates cold-start SFT with reward allocation and scheduling mechanism [

51], transitioning from lenient to strict scoring to stabilize RL training. The action enhances the model’s ability to couple multiple reasoning and action steps.

Multimodality is also one of the methods to improve the effect of RL, and many web agents are developing towards multimodality. For example: WebVoyager leverages both visual (screenshots) and textual (HTML elements) modalities for interaction [

52]. It utilizes the GPT-4V-ACT tool to annotate visual inputs (e.g., screenshots with numbered bounding boxes), which are then mapped to auxiliary text descriptions. This approach bypasses the need to parse complex HTML DOM or accessibility trees, simplifying structural representation. A detailed discussion of multimodal Web Agents is provided in

Section 4.3.

3.3. Specialist Parsing Web Agents

Due to the complexity of web environments and the diversity of user objectives, Web Agents can acquire information from multiple sources. While, in principle, accessing a broader range of information types is preferable, focusing on a specific category for in-depth filtering and analysis can also yield effective results. This approach imposes lower demands on the model, making it suitable for lightweight Web Agents. Consequently, the goal-specific Web Agents—those specialized in target elements or actions—emerges. Training such specialized Web Agents typically requires well-defined objectives and dedicated datasets [

55,

56].

For example, WebDancer specializes in QA pair parsing, aiming to extract high-quality trajectories from QA pairs to guide fine-tuning and reinforcement learning [

28]. To extend the reasoning depth and hop count of existing QA datasets, the authors developed two datasets: CRAWLQA and E2HQA. CRAWLQA collects data from root URLs of official websites such as arXiv, GitHub, and Wikipedia, while E2HQA constructs its corpus by reformulating initially simple questions into more complex, multi-step queries. A ReAct-based Web Agent employs rejection sampling to extract trajectories from these QA datasets, forming both short and long chain-of-thought (CoT) trajectories. During training, the agent proceeds to formal RL using QA data not utilized in the SFT phase, internalizing CoT generation as an active behavioral component of the model. This process leverages the Dynamic Adaptive Policy Optimization (DAPO) algorithm. Falcon-UI is another example [

54], focusing on graphical user interface (GUI) interactions. For its training, raw data was sourced from Common Crawl, followed by standard deduplication and denoising procedures. The researchers then use APIs with varying resolutions and platform types to simulate diverse device environments (e.g., Android, iOS, Windows, and Linux).The data integration platform interacts with the GUI interface and records the generated new interaction data. Unlike traditional full-page textual datasets, Falcon-UI exclusively logs visible elements, mimicking human-like interactions. The resulting hybrid dataset is then used to train Falcon-UI, significantly improving its GUI processing performance.

In some cases, depending on the task requirements, a Web Agent may employ multiple models. For instance, PhishAgent specializes in phishing website detection by identifying target website brands and their domains [

57]. To recognize the brand of a target website, PhishAgent utilizes both textual and visual models. In many scenarios, textual information alone suffices for brand identification, in which case only LLM is used. However, if textual cues are insufficient or obscured by adversarial attacks, PhishAgent activates its brand extractor (IBE) based on multimodal large language model (MLLM), which identifies brand names from webpage screenshots. Upon successful brand recognition, PhishAgent proceeds to cross-reference the target domain with authentic domain information, which is obtained through both offline and online interactions, to determine whether the site is phishing.

4. Multimodal AI Search

Current AI search methods are predominantly confined to text-only environments, often overlooking the multimodal nature of user queries and the intertwined text-image format of website content. This limitation is especially significant considering the example that you take an antique photo at the museum, but are unaware of its specific knowledge. Therefore, the development of a multimodal AI search engine is essential for enhancing information retrieval and analysis.

4.1. Multimodal Large Language Models

Recently, Multimodal Large Language Models (MLLMs) or Large Multimodal Models (LMMs) [

156] have showcased exceptional performance across a range of applications, including visual question answering, visual perception, understanding, and reasoning. Notable closed-source models include GPT-4V [

157], GPT-4o [

158], and Claude 3.5 Sonnet [

159]. On the open-source front, models such as BLIP [

160,

161], LLaVA [

162,

163], Qwen-VL [

164], Gemini [

165], InternVL [

166], and EMU [

167] have made significant strides. The typical MLLM framework is composed of three primary modules: a visual encoder responsible for processing visual inputs, a pre-trained language model that handles multimodal signals and performs reasoning, and a visual-language projector that serves as a bridge to align the two modalities. In recent years, substantial efforts have been dedicated to designing MLLM benchmarks [

168], examining these models from various perspectives.

4.2. Multimodal Search

Inspired by Text-based AI Search, it is necessary to explore a framework for MLLMs to function as multimodal AI search engines. MMSearch [

58] in

Figure 5 proposes a multimodal AI search engine pipeline named MMSEARCH-ENGINE, empowering any MLLMs with advanced search capabilities. MMSEARCH-ENGINE maximizes the utilization of MLLMs’ multimodal information comprehension abilities, incorporating both visual and textual website content as information sources within the searching process: requery, rerank, and summarization. MMSearch-R1 [

59] in

Figure 5 is an initial effort to equip MLLMs with active image search capabilities through an end-to-end RL framework with the assistance of image search tools. This method is to train models not only to determine when to invoke the image search tool but also to effectively extract, synthesize, and utilize relevant information to support downstream reasoning. This work represents a foundational step toward enabling MLLMs to dynamically interact with external tools in a goal-directed manner, thereby enhancing their performance on long-tailed and knowledge-intensive VQA tasks.

Inspired by text-based AI search, there is a growing need to develop a framework that enables MLLMs to function as multimodal AI search engines. MMSearch [

58], illustrated in

Figure 5, introduces a multimodal AI search engine pipeline called MMSEARCH-ENGINE, which enhances any MLLM with advanced search capabilities. MMSEARCH-ENGINE optimizes the use of MLLMs’ ability to comprehend multimodal information by incorporating both visual and textual website content as information sources during the search process, which includes requery, reranking, and summarization. MMSearch-R1 [

59], also shown in

Figure 5, represents an initial attempt to equip MLLMs with active image search capabilities through an end-to-end reinforcement learning framework [

139], utilizing image search tools. This approach trains models not only to decide when to use the image search tool but also to effectively extract, synthesize, and apply relevant information to support downstream reasoning. This work lays the groundwork for enabling MLLMs to dynamically interact with external tools in a goal-oriented manner, thereby improving their performance on long-tail and knowledge-intensive visual question answering tasks.

4.3. Multimodal Web Agents

Websites are the primary Graphical User Interfaces(GUIs) medium through which humans interact with digital devices. Web agents can significantly enhance the user experience. By leveraging the ability of MLLMs to process and interpret web, Multimodal web agents [

169] can autonomously execute user instructions, simulating human-like interactions such as clicking and typing on websites. Recent years have witnessed significant advancements in multi-modal research, with many Web Agents evolving in this direction [

60,

61].

WebVoyager [

170] first instantiates a web browser and then performs operations using visual signals (i.e., screenshots) and textual signals (i.e., HTML elements) from the web. Its successor, OpenWebVoyager [

62], further refines this approach through an iterative “exploration-feedback-optimization” loop.First, OpenWebVoyager adopts the more multimodal-capable Idefics2 model as its backbone LLM. Second, it abandons WebVoyager’s method of tagging screenshots to establish mappings with text, instead leveraging accessibility trees for association. This enhancement enables autonomous optimization in real-world web environments while eliminating WebVoyager’s dependency on closed-source models. As a result, OpenWebVoyager demonstrates improved capability in handling more complex web navigation tasks.

SEEACT [

63] is a generalist web agent that harnesses the power of MLLMs for integrated visual understanding and acting on the web to solve web-based tasks (e.g., “Rent a truck with the lowest rate” in the car rental website). This work leverages an MLLM like GPT-4V to visually perceive websites and generate plans in textual form. The textual plans are then grounded onto the HTML elements and operations to act on the website. Beyond general domains, Multi-modal Web Agents exhibit high versatility in specialized fields [

57]. For example, InfoTech Assistant employs a “retrieve-generate” collaborative mechanism [

64], integrating 41 types of bridge technology data scraped from the FHWA InfoTechnology website with a raw WebAgent to create a specialized agent for bridge evaluation and infrastructure technology.

Open-source MLLM agents have made remarkable progress in offline evaluation benchmarks. However, their performance in more realistic online settings still lags significantly behind human-level capabilities. A major challenge lies in the scarcity of diverse, large-scale trajectory-level datasets across various domains, as collecting such data is both costly and resource-intensive. To address this, Explorer [

171] has synthesized the most extensive and diverse trajectory-level dataset to date. Notably, the work employs comprehensive web exploration and iterative refinement techniques to capture a wide range of task intents, ensuring the dataset’s diversity and utility.

5. Benchmarks

5.1. Text-Based QA Benchmark

As large language models (LLMs) evolve into tool-using agents, the ability to browse the web in real-time has become a critical yardstick for measuring their reasoning and retrieval competence. A variety of widely used English benchmarks have been proposed to assess retrieval capabilities, including TriviaQA, HotpotQA, FEVER, KILT, GAIA, etc. These datasets cover multi-hop reasoning, knowledge-intensive QA, and fact checking, typically relying on structured sources like Wikipedia and StackExchange.

Traditional Benchmarks Natural Questions (NQ) [

65] is a large-scale QA dataset using real Google search queries and corresponding Wikipedia pages, requiring models to provide both long-form and short-form answers. TriviaQA [

66] is a reading comprehension dataset characterized by complex, compositional questions with significant lexical variation from their evidence, often demanding multi-sentence reasoning. PopQA [

67] is an entity-centric QA dataset designed to test factual knowledge recall across a long-tail distribution of entity popularity. HotpotQA [

68] is a multi-hop QA dataset that requires reasoning across multiple documents and providing sentence-level supporting facts, making it a benchmark for explainable QA. 2WikiMultiHopQA [

172] is a more challenging multi-hop QA dataset that integrates Wikipedia with Wikidata, using structured triples to explain complex reasoning paths. MuSiQue [

69] is a multi-hop QA dataset emphasizing connected reasoning and includes unanswerable examples to challenge models that rely on shortcuts. FEVER [

70] is a benchmark for fact verification, requiring systems to classify claims as

SUPPORTED,

REFUTED, or

NOTENOUGHINFO against Wikipedia and provide sentence-level evidence. KILT [

71] unifies 11 knowledge-intensive NLP tasks under a single Wikipedia snapshot, providing a standardized framework for evaluating both task performance and evidence retrieval. GAIA [

72] evaluates general-purpose AI assistants with real-world questions that require a combination of reasoning, tool use, and multi-modality, revealing a large gap between AI and human performance. TREC Health Misinformation Track [

173] provides datasets with binary “yes/no” health questions based on medical consensus to evaluate a system’s ability to combat health misinformation.

Modern Browsing Benchmarks. While traditional benchmarks mentioned above have effectively measured an AI’s ability to retrieve straightforward information through basic queries (e.g., single-hop fact lookup), their simplicity has led to saturation—modern models now achieve near-perfect scores on these tasks. This progress reveals a critical gap: real-world information needs often require persistent navigation through complex data landscapes. These challenges mirror the evolutionary jump from arithmetic tests to mathematical proofs—where success depends less on recall and more on strategic problem-solving.

BrowseComp [

73] is a benchmark dataset introduced to evaluate web-browsing AI agents. It contains 1,266 challenging questions requiring persistent navigation of the internet to find entangled information. Key features include: (1)

High difficulty - questions are designed to be unsolvable by humans within 10 minutes; (2)

Verifiability - short reference answers enable easy validation; (3)

Diverse topics spanning sports, fiction, and academic publications; and (4)

Core capability measurement focusing on persistence, factual reasoning, and creative search strategies. BrowseComp-ZH [

74] benchmark is a high-difficulty Chinese web browsing evaluation dataset consisting of 289 multi-hop questions across 11 domains (e.g., Art, Film&TV, Medicine). Each question is reverse-engineered from verifiable factual answers and undergoes rigorous two-stage quality control to ensure retrieval difficulty and answer uniqueness.

Figure 6 illustrates these two benchmarks and shows some complex and challenging queries. Mind2Web 2 [

75] is also a modern benchmark with 130 realistic, high-quality, and long-horizon tasks that require real-time web browsing and extensive information synthesis.

5.2. Web Agent Benchmark

Web Agent Benchmark refer to a standardized set of test tasks and evaluation frameworks designed to assess the performance of web agents. These benchmarks simulate interactive tasks in real-world web environments to quantify an agent’s capabilities in navigation, operation, and reasoning. A Web Agent Benchmark consists of two key components: tasks (data) and metrics. Tasks refer to a series of operational requirements posed to web agents, mimicking typical human web activities, such as clicking buttons, filling out forms, or navigating between pages. More complex tasks may involve multi-step processes. Metrics are the standards used to evaluate a web agent’s performance, which vary depending on the agent’s functionality and objectives [

78,

79,

81,

83].

Mind2Web [

76] shown in

Figure 7 is the first dataset designed for developing and evaluating general-purpose Web Agents. Its tasks include five top-level domains (travel, shopping, services, entertainment, and information). Each task consists of three core components: Task description: This outlines the high-level goal of the task. Action sequence: This is the sequence of actions required to complete the task on the website. Each action includes the target element and the corresponding operation. Webpage snapshot: It captures the webpage environment during task execution. In short, these three components contain all the task-related information. WebArena [

77] analyzed real-world web browser histories and abstracted four prominent categories: e-commerce, social forums, collaborative software development, and content management. For task design, the authors curated three task types: Information seeking – requiring multi-page navigation. Website navigation – using interactive elements (e.g., search functions and links) to locate specific information in webpages. Content/configuration manipulation – creating, modifying, or configuring content (settings). Task evaluation involves: (1) comparing outputs for information seeking tasks, and (2) reward-based assessment of intermediate states for navigation and manipulation tasks. WebChoreArena [

80] adheres to WebArena’s design principles. However, its benchmark has new tasks. Their key characteristics include: (1)Emphasis on memory-intensive analytical tasks. (2)Reduction of ambiguity in task instructions and evaluation, a notable departure from WebArena. (3)Template-based task construction and expansion. Experiments on GPT-4o indicate that WebChoreArena presents greater challenges than WebArena. WebCanvas [

82] introduces a dynamic evaluation framework using “critical nodes”. Critical nodes refer to essential steps that must be completed in any viable path to accomplish a given web task. To enhance realism, the authors derive Mind2Web-Live from tasks in the Mind2Web dataset. Mind2Web-Live includes critical nodes and meticulously annotated steps. Subsequent experiments demonstrate that in partially web environments, evaluating solely the final state or outcome is insufficient.

For task-specific objectives, general-purpose benchmarks often prove inadequate for evaluating Web Agent performance in their domains, necessitating dedicated benchmarks [

85,

86,

87,

88]. For instance, DeepShop focuses on e-commerce, generating query tasks across five popular online shopping categories [

89]. During assessment, it adopts a fine-grained approach by separately evaluating product attributes, matching accuracy, and ranking performance, ultimately synthesizing a comprehensive evaluation. SafeArena [

84], the first benchmark dedicated to assessing malicious use cases of Web Agents, comprises 250 security tasks and 250 harmful tasks. Its evaluation metrics include the standard Task Completion Rate (TCR), and specialized measures rarely adopted by other benchmarks: Normalized Security Score (NSS) and Rejection Rate.

5.3. MM Search Benchmark

Large language models (LLMs) have made significant strides in understanding and reasoning about live textual content when integrated with search engines. Despite these advancements, a crucial question remains: has the understanding of other modalities, such as visual knowledge in live contexts, been similarly addressed? Are there benchmarks for multimodal search methods?

MMSearch [

58] introduced a multimodal AI search engine benchmark to thoroughly assess the searching performance of MLLMs, marking the first evaluation dataset to measure MLLMs’ capabilities in multimodal searching. LIVEVQA [

90], depicted in

Figure 8, is an automatically collected benchmark dataset specifically designed to evaluate current AI systems on their ability to answer questions requiring live visual knowledge. However, existing benchmarks for this critical task face a significant shortage of suitable datasets and scientifically rigorous evaluation metrics. MRAMG-Bench [

91] is a novel benchmark created to comprehensively evaluate the MRAMG task. It consists of six meticulously curated English datasets, including 4,346 documents, 14,190 images, and 4,800 QA pairs, sourced from three domains: Web, Academia, and Lifestyle, across seven distinct data sources.

VisualWebArena [

78] is primarily designed for visual web agent tasks, incorporating both textual and visual content from real-world environments. It comprises 910 real-world tasks across three distinct web environments. A key feature of VisualWebArena is that all tasks require agents to process and interpret visual information, rather than relying solely on textual or HTML-based cues. For evaluation, the metrics follow WebArena’s framework but extend it by incorporating image verification alongside the original two assessment methods.

6. Softwares and Products

AI search ecosystem has rapidly diversified into general-purpose platforms, domain-specific tools, and integrated assistants, each leveraging large language models (LLMs), retrieval-augmented generation (RAG), and agentic workflows to redefine information retrieval. Below, we will introduce the key products driving this transformation.

Global General-Purpose AI Search Engines. A pioneer in generative AI, ChatGPT Deep Research [

7] integrates Bing’s real-time web search to provide concise, conversational responses, sparking a surge of interest among researchers in large language models. Perplexity Deep Research [

92] combines GPT-4 and Claude 3 with real-time web crawling, providing source-attributed answers. Its Discover feature tracks trending topics, making it ideal for academic literature reviews and technical writing. You.com [

174] prioritizes privacy and personalization, allowing model switching (e.g., GPT-4, Claude) mid-session. Its Smart mode offers free access, while Research mode supports deep investigations with citation exports. Gemini Deep Research [

98] embeds multi-modal capabilities into Pixel phones and Wear OS, enabling real-time translation via camera and health data-driven recommendations, reinforcing its “hardware-software” synergy in high-end markets. Optimized for speed and cost-efficiency, Doubao [

93] integrates seamlessly with Douyin for video-content searches. Yuanbao [

94] redefines “search-as-service” by embedding within WeChat’s ecosystem. Its three-layer architecture—base model (trillion-parameter MoE), industry-specific tuning (e.g., medical diagnostics), and mini-program integration—enables seamless service execution (e.g., generating travel itineraries with bookings). This ecosystem approach has driven rapid adoption. Nano AI [

95] is China’s first “super search agent” that autonomously plans tasks (e.g., travel itineraries, market reports) by integrating data from walled gardens. Its DeepSearch technology parses tables, formulas, and video comments, enabling cross-platform verification for reliable decision-making. Kimi [

96] can process 200 K-context windows, ideal for academic paper analysis. Users highlight its semantic search for Chinese literature. DeepSeek Search [

99] represents a paradigm shift in cost-efficient, open-source AI search. Quark DeepSearch [

97] relies on Qwen-QWQ inference model. Unlike traditional search engines that rely on keyword matching, the model understands natural language and performs semantic analysis to more accurately grasp user intent.

Domain-Specific AI Search Tools. MediSearch [

100] provides evidence-based medical answers (e.g., drug interactions, treatment protocols), trusted by 74% of healthcare professionals for clinical decision support. Devv.ai [

101] is a code-specific search engine offering real-time debugging snippets and GitHub integration. It supports Chinese queries but is limited to programming contexts. Consensus [

102] accesses 200 M+ scientific papers, using NLP to extract hypotheses and methodologies. Researchers report 50% time savings in literature reviews.

Integrated AI Search Assistants WallesAI [

103] is a browser-sidebar assistant that reads PDFs, videos, and webpages, enabling cross-document Q&A and content export. Bing Chat [

104], deeply integrated into Edge’s ecosystem, delivers citation-backed answers through real-time web indexing and source attribution, establishing a unified search-browser experience.

7. Challenges and Future Research

Despite the notable progress, this field still faces many unresolved challenges, and there is considerable room for improvement. We finally highlight several promising directions based on the reviewed progress:

Methods More complex problems lead to a prolonged search process and additional actions, resulting in an extended search context. This extended context can limit the effectiveness of AIS methods and the ability of LLMs, causing search performance to degrade as the inference length increases.

Evaluations There is a strong need for systematic and standardized evaluation frameworks in AI search. The datasets used for evaluation should be meticulously curated to closely resemble real-world scenarios, featuring complex, dynamic, and citation-supported answers.

Applications The potential real-world applications of AI Search are significant. Beyond user scenarios, there are numerous applications across various industries. We hope to see the development of more AIS software and products to enhance the interaction between humans and machines.

8. Conclusions

Seeking and accessing information is a fundamental daily need for humans. In this survey, we provide a thorough overview of the latest research on AI Search based on LLMs. Our goal is to identify and highlight areas that require further research and suggest potential avenues for future studies. We start by introducing the traditional information retrieval systems, large language models (LLMs), and AI Search based on LLMs. Subsequently, we classify existing studies into four categories: Text-based AI Search, Web Browsing Agent, Multimodal AI Search, and Benchmarks. Then, we spotlight a range of current and significant Software and products within the realm of AI search. Finally, we discuss the limitations of the current AI search methods and explore promising future directions.

References

- Brin, S.; Page, L. The anatomy of a large-scale hypertextual web search engine. Computer networks and ISDN systems 1998, 30, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkhin, P. A survey on PageRank computing. Internet mathematics 2005, 2, 73–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burges, C.; Shaked, T.; Renshaw, E.; Lazier, A.; Deeds, M.; Hamilton, N.; Hullender, G. Learning to rank using gradient descent. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 22nd international conference on Machine learning, 2005, pp.

- Nadkarni, P.M.; Ohno-Machado, L.; Chapman, W.W. Natural language processing: an introduction. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 2011, 18, 544–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, M.; Takeda, K. Information retrieval on the web. ACM computing surveys (CSUR) 2000, 32, 144–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.X.; Zhou, K.; Li, J.; Tang, T.; Wang, X.; Hou, Y.; Min, Y.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, J.; Dong, Z.; et al. A survey of large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.18223 2023, arXiv:2303.18223 2023, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Research, C.D. https://openai.com/index/introducing-deep-research, 2022.

- Touvron, H.; Lavril, T.; Izacard, G.; Martinet, X.; Lachaux, M.A.; Lacroix, T.; Rozière, B.; Goyal, N.; Hambro, E.; Azhar, F.; et al. Llama: Open and efficient foundation language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.13971, arXiv:2302.13971 2023.

- Lewis, P.S.H.; Perez, E.; Piktus, A.; Petroni, F.; Karpukhin, V.; Goyal, N.; Küttler, H.; Lewis, M.; tau Yih, W.; Rocktäschel, T.; et al. Retrieval-Augmented Generation for Knowledge-Intensive NLP Tasks. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 33: Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 2020, NeurIPS, December 6-12, , virtual, . 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, F.; Shi, W.; Choi, E. RECOMP: Improving Retrieval-Augmented LMs with Compression and Selective Augmentation. CoRR 2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Wu, Q.; Lin, C.Y.; Yang, Y.; Qiu, L. LLMLingua: Compressing Prompts for Accelerated Inference of Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing. [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Li, X.; Dong, G.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Li, Z.; Ye, Q.; Dou, Z. Hierarchical Document Refinement for Long-context Retrieval-augmented Generation, 2025; arXiv:cs.CL/2505.10413]. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, G.; Kim, S.; Jeon, B.; Park, J.; Kang, J. Tree of Clarifications: Answering Ambiguous Questions with Retrieval-Augmented Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Singapore, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Min, S.; Yasunaga, M.; Seo, M.; James, R.; Lewis, M.; Zettlemoyer, L.; tau Yih, W. REPLUG: Retrieval-Augmented Black-Box Language Models. CoRR, 2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Iter, D.; Wang, S.; Xu, Y.; Ju, M.; Sanyal, S.; Zhu, C.; Zeng, M.; Jiang, M. Generate rather than retrieve: Large language models are strong context generators. arXiv preprint arXiv:2209.10063, arXiv:2209.10063 2022.

- Wang, H.; Zhao, T.; Gao, J. BlendFilter: Advancing Retrieval-Augmented Large Language Models via Query Generation Blending and Knowledge Filtering. 2024; arXiv:cs.CL/2402.11129]. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Li, P.; Sun, M.; Liu, Y. Self-knowledge guided retrieval augmentation for large language models. arXiv, 2023; arXiv:2310.05002 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Xue, B.; Zhou, B.; Zhang, T.; Wang, C.; Chen, G.; Wang, H.; Wong, K.f. Self-DC: When to retrieve and When to generate? Self Divide-and-Conquer for Compositional Unknown Questions. arXiv, 2024; arXiv:2402.13514 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, H.; Pang, L.; Wei, Z.; Shen, H.; Cheng, X. Retrieve Only When It Needs: Adaptive Retrieval Augmentation for Hallucination Mitigation in Large Language Models. 2024; arXiv:cs.CL/2402.10612]. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, J.; Dou, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Guo, P.; Fang, K.; Wen, J.R. Small Models, Big Insights: Leveraging Slim Proxy Models To Decide When and What to Retrieve for LLMs. CoRR, 2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.; Zhao, J.; Yu, D.; Shafran, I.; Narasimhan, K.R.; Cao, Y. ReAct: Synergizing Reasoning and Acting in Language Models. In Proceedings of the NeurIPS 2022 Foundation Models for Decision Making Workshop; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, Z.; Gong, Y.; Shen, Y.; Huang, M.; Duan, N.; Chen, W. Enhancing Retrieval-Augmented Large Language Models with Iterative Retrieval-Generation Synergy. 2023; arXiv:cs.CL/2305.15294]. [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi, H.; Balasubramanian, N.; Khot, T.; Sabharwal, A. Interleaving retrieval with chain-of-thought reasoning for knowledge-intensive multi-step questions. arXiv, 2022; arXiv:2212.10509 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Z.; Xu, F.F.; Gao, L.; Sun, Z.; Liu, Q.; Dwivedi-Yu, J.; Yang, Y.; Callan, J.; Neubig, G. Active Retrieval Augmented Generation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, EMNLP 2023, Singapore, December 6-10, 2023.

- Asai, A.; Wu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Sil, A.; Hajishirzi, H. Self-RAG: Learning to Retrieve, Generate, and Critique through Self-Reflection. CoRR, 2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Dong, G.; Jin, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, P.; Dou, Z. Search-o1: Agentic Search-Enhanced Large Reasoning Models. CoRR, 2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Jin, J.; Dong, G.; Qian, H.; Zhu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Wen, J.; Dou, Z. WebThinker: Empowering Large Reasoning Models with Deep Research Capability. CoRR, 2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Li, B.; Fang, R.; Yin, W.; Zhang, L.; Tao, Z.; Zhang, D.; Xi, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Xie, P.; et al. WebDancer: Towards Autonomous Information Seeking Agency. 2025; arXiv:cs.CL/2505.22648]. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, R.; Yan, J.; Li, J.; Zhao, W.X. ManuSearch: Democratizing Deep Search in Large Language Models with a Transparent and Open Multi-Agent Framework. 2025; arXiv:cs.CL/2505.18105]. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, T.; Yao, Z.; Jin, B.; Cui, L.; Li, Y.; Wang, G.; Liu, X. Demystifying and Enhancing the Efficiency of Large Language Model Based Search Agents. 2025; arXiv:cs.AI/2505.12065]. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, J.; Li, X.; Dong, G.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Qian, H.; Dou, Z. Decoupled Planning and Execution: A Hierarchical Reasoning Framework for Deep Search. 2025; arXiv:cs.AI/2507.02652]. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, W.; Guan, X.; Huang, S.; Jiang, Y.; Xie, P.; Huang, F.; Cao, J.; Zhao, H.; Zhou, J. MaskSearch: A Universal Pre-Training Framework to Enhance Agentic Search Capability. 2025; arXiv:cs.CL/2505.20285]. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Chen, H.; Yang, N.; Huang, X.; Dou, Z.; Wei, F. Chain-of-Retrieval Augmented Generation. 2025; arXiv:cs.IR/2501.14342]. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Z.; Cao, S.; Liu, J.; Zhang, J.; Liu, W.; Che, X.; Hou, L.; Li, J. ReaRAG: Knowledge-guided Reasoning Enhances Factuality of Large Reasoning Models with Iterative Retrieval Augmented Generation. 2025; arXiv:cs.CL/2503.21729]. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Z.; Yan, L.; Yin, D.; Verberne, S.; de Rijke, M.; Ren, Z. Iterative Self-Incentivization Empowers Large Language Models as Agentic Searchers. 2025; arXiv:cs.CL/2505.20128]. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, M.; Fang, T.; Zhang, J.; Ma, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, H.; Mi, H.; Yu, D.; King, I. WebCoT: Enhancing Web Agent Reasoning by Reconstructing Chain-of-Thought in Reflection, Branching, and Rollback. 2025; arXiv:cs.CL/2505.20013]. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, X.; Zeng, J.; Meng, F.; Xin, C.; Lu, Y.; Lin, H.; Han, X.; Sun, L.; Zhou, J. DeepRAG: Thinking to Retrieve Step by Step for Large Language Models. 2025; arXiv:cs.AI/2502.01142]. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, B.; Zeng, H.; Yue, Z.; Yoon, J.; Arik, S.; Wang, D.; Zamani, H.; Han, J. Search-R1: Training LLMs to Reason and Leverage Search Engines with Reinforcement Learning. 2025; arXiv:cs.CL/2503.09516]. [Google Scholar]

- Song, H.; Jiang, J.; Min, Y.; Chen, J.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, W.X.; Fang, L.; Wen, J.R. R1-Searcher: Incentivizing the Search Capability in LLMs via Reinforcement Learning. 2025; arXiv:cs.AI/2503.05592]. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.; Li, T.; Sun, H.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, C.; Wang, H.; Pan, J.Z.; Zhang, W.; Chen, H.; Yang, F.; et al. ReSearch: Learning to Reason with Search for LLMs via Reinforcement Learning. 2025; arXiv:cs.AI/2503.19470]. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, H.; Qiao, Z.; Guo, J.; Fan, X.; Hou, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Xie, P.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, F.; Zhou, J. ZeroSearch: Incentivize the Search Capability of LLMs without Searching. 2025; arXiv:cs.CL/2505.04588]. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y.; Fu, D.; Hu, X.; Cai, X.; Ye, L.; Lu, P.; Liu, P. DeepResearcher: Scaling Deep Research via Reinforcement Learning in Real-world Environments. 2025; arXiv:cs.AI/2504.03160]. [Google Scholar]

- Mei, J.; Hu, T.; Fu, D.; Wen, L.; Yang, X.; Wu, R.; Cai, P.; Cai, X.; Gao, X.; Yang, Y.; et al. O2-Searcher: A Searching-based Agent Model for Open-Domain Open-Ended Question Answering. 2025; arXiv:cs.CL/2505.16582]. [Google Scholar]

- Li, K.; Zhang, Z.; Yin, H.; Zhang, L.; Ou, L.; Wu, J.; Yin, W.; Li, B.; Tao, Z.; Wang, X.; et al. WebSailor: Navigating Super-human Reasoning for Web Agent. 2025; arXiv:cs.CL/2507.02592]. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Zheng, X.; An, K.; Ouyang, C.; Cai, J.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Y. StepSearch: Igniting LLMs Search Ability via Step-Wise Proximal Policy Optimization. 2025; arXiv:cs.CL/2505.15107]. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Z.; Yao, W.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Lu, Q.; Qiu, L.; Yu, C.; Xu, P.; Zhang, C.; Yin, B.; et al. WebAgent-R1: Training Web Agents via End-to-End Multi-Turn Reinforcement Learning. 2025; arXiv:cs.CL/2505.16421]. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, H.; Liu, X.; Iong, I.L.; Yao, S.; Chen, Y.; Shen, P.; Yu, H.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, X.; Dong, Y.; et al. AutoWebGLM: A Large Language Model-based Web Navigating Agent. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 30th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, New York, NY, USA, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Xu, F.; Zhou, S.; Neubig, G. Beyond Browsing: API-Based Web Agents. 2025; arXiv:cs.CL/2410.16464]. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.; Rama, B.; Ni, J.; He, S.; Zhao, F.; Chen, K.; Chen, A.; Cao, J. LiteWebAgent: The Open-Source Suite for VLM-Based Web-Agent Applications. 2025; arXiv:cs.AI/2503.02950]. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, K.; Liu, Y.; Chaudhary, S.; Fakoor, R.; Chaudhari, P.; Karypis, G.; Rangwala, H. AgentOccam: A Simple Yet Strong Baseline for LLM-Based Web Agents. 2025; arXiv:cs.AI/2410.13825]. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, W.; Tan, H.; Kuang, C.; Li, X.; Ren, X.; Zhang, C.; Chen, H.; Wang, Y.; Shang, L.; Yu, F.; et al. Pangu DeepDiver: Adaptive Search Intensity Scaling via Open-Web Reinforcement Learning. 2025; arXiv:cs.CL/2505.24332]. [Google Scholar]

- He, H.; Yao, W.; Ma, K.; Yu, W.; Dai, Y.; Zhang, H.; Lan, Z.; Yu, D. WebVoyager: Building an End-to-End Web Agent with Large Multimodal Models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers). [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Li, B.; Fang, R.; Yin, W.; Zhang, L.; Tao, Z.; Zhang, D.; Xi, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Xie, P.; et al. WebDancer: Towards Autonomous Information Seeking Agency. 2025; arXiv:cs.CL/2505.22648]. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, H.; Liu, C.; Li, G.; Wang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Ma, C.; Ji, X. Falcon-UI: Understanding GUI Before Following User Instructions. 2024; arXiv:cs.CL/2412.09362]. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, J.; Kim, J.; Bae, D.; Choo, J.; Gwon, Y.; Kwon, Y.D. CAAP: Context-Aware Action Planning Prompting to Solve Computer Tasks with Front-End UI Only. 2024; arXiv:cs.AI/2406.06947]. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, K.Q.; Li, L.; Gao, D.; Yang, Z.; Wu, S.; Bai, Z.; Lei, W.; Wang, L.; Shou, M.Z. ShowUI: One Vision-Language-Action Model for GUI Visual Agent. 2024; arXiv:cs.CV/2411.17465]. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, T.; Huang, C.; Li, Y.; Huilin, W.; He, A.; Oo, N.; Hooi, B. PhishAgent: A Robust Multimodal Agent for Phishing Webpage Detection. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 2025, 39, 27869–27877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.; Zhang, R.; Guo, Z.; Wu, Y.; Qiu, P.; Lu, P.; Chen, Z.; Song, G.; Gao, P.; Liu, Y.; et al. MMSearch: Unveiling the Potential of Large Models as Multi-modal Search Engines. In Proceedings of the The Thirteenth International Conference on Learning Representations.

- Wu, J.; Deng, Z.; Li, W.; Liu, Y.; You, B.; Li, B.; Ma, Z.; Liu, Z. MMSearch-R1: Incentivizing LMMs to Search. 2025; arXiv:cs.CV/2506.20670]. [Google Scholar]

- Pahuja, V.; Lu, Y.; Rosset, C.; Gou, B.; Mitra, A.; Whitehead, S.; Su, Y.; Awadallah, A. Explorer: Scaling Exploration-driven Web Trajectory Synthesis for Multimodal Web Agents 2025.

- Verma, G.; Kaur, R.; Srishankar, N.; Zeng, Z.; Balch, T.; Veloso, M. AdaptAgent: Adapting Multimodal Web Agents with Few-Shot Learning from Human Demonstrations. 2024; arXiv:cs.AI/2411.13451]. [Google Scholar]

- He, H.; Yao, W.; Ma, K.; Yu, W.; Zhang, H.; Fang, T.; Lan, Z.; Yu, D. OpenWebVoyager: Building Multimodal Web Agents via Iterative Real-World Exploration, Feedback and Optimization. 2024; arXiv:cs.CL/2410.19609]. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, B.; Gou, B.; Kil, J.; Sun, H.; Su, Y. Gpt-4v (ision) is a generalist web agent, if grounded. arXiv, 2024; arXiv:2401.01614 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Gadiraju, S.S.; Liao, D.; Kudupudi, A.; Kasula, S.; Chalasani, C. InfoTech Assistant: A Multimodal Conversational Agent for InfoTechnology Web Portal Queries. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (BigData); 2024; pp. 3264–3272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwiatkowski, T.; Palomaki, J.; Redfield, O.; Collins, M.; Parikh, A.; Alberti, C.; Epstein, D.; Polosukhin, I.; Devlin, J.; Lee, K.; et al. Natural questions: a benchmark for question answering research. Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics 2019, 7, 453–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, M.; Choi, E.; Weld, D.S.; Zettlemoyer, L. Triviaqa: A large scale distantly supervised challenge dataset for reading comprehension. arXiv preprint arXiv:1705.03551, arXiv:1705.03551 2017.

- Mallen, A.; Asai, A.; Zhong, V.; Das, R.; Khashabi, D.; Hajishirzi, H. When not to trust language models: Investigating effectiveness of parametric and non-parametric memories. arXiv arXiv:2212.10511, arXiv:2212.10511 2022.

- Yang, Z.; Qi, P.; Zhang, S.; Bengio, Y.; Cohen, W.W.; Salakhutdinov, R.; Manning, C.D. HotpotQA: A dataset for diverse, explainable multi-hop question answering. arXiv preprint arXiv:1809.09600, arXiv:1809.09600 2018.

- Trivedi, H.; Balasubramanian, N.; Khot, T.; Sabharwal, A. MuSiQue: Multihop Questions via Single-hop Question Composition. Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics 2022, 10, 539–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorne, J.; Vlachos, A.; Christodoulopoulos, C.; Mittal, A. FEVER: a large-scale dataset for fact extraction and VERification. arXiv preprint arXiv:1803.05355, arXiv:1803.05355 2018.

- Petroni, F.; Piktus, A.; Fan, A.; Lewis, P.; Yazdani, M.; De Cao, N.; Thorne, J.; Jernite, Y.; Karpukhin, V.; Maillard, J.; et al. KILT: a benchmark for knowledge intensive language tasks. arXiv arXiv:2009.02252, arXiv:2009.02252 2020.

- Mialon, G.; Fourrier, C.; Wolf, T.; LeCun, Y.; Scialom, T. Gaia: a benchmark for general ai assistants. In Proceedings of the The Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, J.; Sun, Z.; Papay, S.; McKinney, S.; Han, J.; Fulford, I.; Chung, H.W.; Passos, A.T.; Fedus, W.; Glaese, A. Browsecomp: A simple yet challenging benchmark for browsing agents. arXiv arXiv:2504.12516, arXiv:2504.12516 2025.

- Zhou, P.; Leon, B.; Ying, X.; Zhang, C.; Shao, Y.; Ye, Q.; Chong, D.; Jin, Z.; Xie, C.; Cao, M.; et al. Browsecomp-zh: Benchmarking web browsing ability of large language models in chinese. arXiv preprint arXiv:2504.19314, arXiv:2504.19314 2025.

- Gou, B.; Huang, Z.; Ning, Y.; Gu, Y.; Lin, M.; Qi, W.; Kopanev, A.; Yu, B.; Gutiérrez, B.J.; Shu, Y.; et al. Mind2Web 2: Evaluating Agentic Search with Agent-as-a-Judge. 2025; arXiv:cs.AI/2506.21506]. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, X.; Gu, Y.; Zheng, B.; Chen, S.; Stevens, S.; Wang, B.; Sun, H.; Su, Y. Mind2Web: Towards a Generalist Agent for the Web. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Oh, A.; Naumann, T.; Globerson, A.; Saenko, K.; Hardt, M.; Levine, S., Eds. Curran Associates, Inc., Vol. 36; 2023; pp. 28091–28114. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, S.; Xu, F.F.; Zhu, H.; Zhou, X.; Lo, R.; Sridhar, A.; Cheng, X.; Ou, T.; Bisk, Y.; Fried, D.; et al. WebArena: A Realistic Web Environment for Building Autonomous Agents. 2024; arXiv:cs.AI/2307.13854]. [Google Scholar]

- Koh, J.Y.; Lo, R.; Jang, L.; Duvvur, V.; Lim, M.; Huang, P.Y.; Neubig, G.; Zhou, S.; Salakhutdinov, R.; Fried, D. VisualWebArena: Evaluating Multimodal Agents on Realistic Visual Web Tasks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers). [CrossRef]

- Garg, D.; VanWeelden, S.; Caples, D.; Draguns, A.; Ravi, N.; Putta, P.; Garg, N.; Abraham, T.; Lara, M.; Lopez, F.; et al. REAL: Benchmarking Autonomous Agents on Deterministic Simulations of Real Websites. 2025; arXiv:cs.AI/2504.11543]. [Google Scholar]

- Miyai, A.; Zhao, Z.; Egashira, K.; Sato, A.; Sunada, T.; Onohara, S.; Yamanishi, H.; Toyooka, M.; Nishina, K.; Maeda, R.; et al. WebChoreArena: Evaluating Web Browsing Agents on Realistic Tedious Web Tasks. 2025; arXiv:cs.CL/2506.01952]. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y.; Thai, K.; Pham, C.M.; Chang, Y.; Nadaf, M.; Iyyer, M. BEARCUBS: A benchmark for computer-using web agents. 2025; arXiv:cs.AI/2503.07919]. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Y.; Kong, D.; Zhou, S.; Cui, C.; Leng, Y.; Jiang, B.; Liu, H.; Shang, Y.; Zhou, S.; Wu, T.; et al. WebCanvas: Benchmarking Web Agents in Online Environments. 2024; arXiv:cs.CL/2406.12373]. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, K.; Kordi, Y.; Nayak, T.; Asija, A.; Wang, Y.; Sanders, K.; Byerly, A.; Zhang, J.; Van Durme, B.; Khashabi, D. TurkingBench: A Challenge Benchmark for Web Agents. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2025 Conference of the Nations of the Americas Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies (Volume 1: Long Papers). [CrossRef]

- Tur, A.D.; Meade, N.; Lù, X.H.; Zambrano, A.; Patel, A.; Durmus, E.; Gella, S.; Stańczak, K.; Reddy, S. SafeArena: Evaluating the Safety of Autonomous Web Agents. 2025; arXiv:cs.LG/2503.04957]. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Kellermann, A.; Bowman, D.; Li, P.; Gupta, A.; Danda, A.; Fang, R.; Jensen, C.; Ihli, E.; Benn, J.; et al. CVE-Bench: A Benchmark for AI Agents’ Ability to Exploit Real-World Web Application Vulnerabilities. 2025; arXiv:cs.CR/2503.17332]. [Google Scholar]

- Evtimov, I.; Zharmagambetov, A.; Grattafiori, A.; Guo, C.; Chaudhuri, K. WASP: Benchmarking Web Agent Security Against Prompt Injection Attacks. 2025; arXiv:cs.CR/2504.18575]. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, H.; Fabbri, A.; Agarwal, D.; Huang, K.H.; Tan, S.; Peng, N.; Wu, C.S. Evaluating Cultural and Social Awareness of LLM Web Agents. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: NAACL 2025; Chiruzzo, L.; Ritter, A.; Wang, L., Eds., Albuquerque, New Mexico; 2025; pp. 3978–4005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Li, Z.; Liu, J.; Cui, J.; Zhao, X.; Shen, Z. Open CaptchaWorld: A Comprehensive Web-based Platform for Testing and Benchmarking Multimodal LLM Agents. 2025; arXiv:cs.AI/2505.24878]. [Google Scholar]

- Lyu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yan, L.; de Rijke, M.; Ren, Z.; Chen, X. DeepShop: A Benchmark for Deep Research Shopping Agents. 2025; arXiv:cs.IR/2506.02839]. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, M.; Peng, Y.; Liu, B.; Wan, Y.; Chen, D. LiveVQA: Live Visual Knowledge Seeking. arXiv, 2025; arXiv:2504.05288 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Q.; Xiao, Z.; Li, B.; Wang, Z.; Chen, C.; Zhang, W. MRAMG-Bench: A BeyondText Benchmark for Multimodal Retrieval-Augmented Multimodal Generation. arXiv, 2025; arXiv:2502.04176 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Research, P.D. https://www.perplexity.ai, 2022.

- Doubao. https://www.doubao.com, 2023.

- Yuanbao. https://yuanbao.tencent.com, 2024.

- AI, N. https://www.n.cn, 2025.

- Kimi. https://www.kimi.com, 2023.

- DeepSearch, Q. https://quark.sm.cn, 2025.

- Research, G.D. https://gemini.google/overview/deep-research, 2023.

- DeepSeek. https://www.deepseek.com, 2025.

- MediSearch. https://medisearch.io, 2023.

- Devv.ai. https://devv.ai/zh, 2023.

- Consensus. https://consensus.app, 2022.

- walles.ai. https://walles.ai/, 2023.

- Chat, B. http://bing.com, 2023.

- Gao, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Gao, X.; Jia, K.; Pan, J.; Bi, Y.; Dai, Y.; Sun, J.; Guo, Q.; Wang, M.; et al. A: Generation for Large Language Models, 2024; arXiv:cs.CL/2312.10997].

- Zhu, Y.; Yuan, H.; Wang, S.; Liu, J.; Liu, W.; Deng, C.; Chen, H.; Liu, Z.; Dou, Z.; Wen, J.R. Large language models for information retrieval: A survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.07107, arXiv:2308.07107 2023.

- Ramos, J.; et al. Using tf-idf to determine word relevance in document queries. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the first instructional conference on machine learning.

- Robertson, S.E.; Zaragoza, H. The Probabilistic Relevance Framework: BM25 and Beyond. Found. Trends Inf. Retr. 2009, 3, 333–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpukhin, V.; Oguz, B.; Min, S.; Lewis, P.; Wu, L.; Edunov, S.; Chen, D.; Yih, W.t. Dense Passage Retrieval for Open-Domain Question Answering. In Proceedings of the EMNLP; 2020; pp. 6769–6781. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, L.; Xiong, C.; Li, Y.; Tang, K.F.; Liu, J.; Bennett, P.N.; Ahmed, J.; Overwijk, A. Approximate Nearest Neighbor Negative Contrastive Learning for Dense Text Retrieval. In Proceedings of the ICLR; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Yang, N.; Huang, X.; Jiao, B.; Yang, L.; Jiang, D.; Majumder, R.; Wei, F. Text Embeddings by Weakly-Supervised Contrastive Pre-training. CoRR, 2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, P.; Muennighoff, N.; Lian, D.; Nie, J.Y. C-Pack: Packed Resources For General Chinese Embeddings. 2024; arXiv:cs.CL/2309.07597]. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Jin, J.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, P.; Zhu, Y.; Dou, Z. From matching to generation: A survey on generative information retrieval. ACM Transactions on Information Systems 2025, 43, 1–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, Y.; Tran, V.; Dehghani, M.; Ni, J.; Bahri, D.; Mehta, H.; Qin, Z.; Hui, K.; Zhao, Z.; Gupta, J.P.; et al. Transformer Memory as a Differentiable Search Index. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 35: Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 2022, NeurIPS 2022, New Orleans, LA, USA, 2022, 2022., November 28 - December 9.

- Wang, Y.; Hou, Y.; Wang, H.; Miao, Z.; Wu, S.; Chen, Q.; Xia, Y.; Chi, C.; Zhao, G.; Liu, Z.; et al. A neural corpus indexer for document retrieval. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2022, 35, 25600–25614. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Dou, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, F. Corpuslm: Towards a unified language model on corpus for knowledge-intensive tasks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 47th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, 2024, pp.

- Liu, T.Y.; et al. Learning to rank for information retrieval. Foundations and Trends® in Information Retrieval 2009, 3, 225–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khattab, O.; Zaharia, M. ColBERT: Efficient and Effective Passage Search via Contextualized Late Interaction over BERT. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 43rd International ACM SIGIR conference on research and development in Information Retrieval, SIGIR 2020, Virtual Event, China, July 25-30, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Yan, L.; Ma, X.; Wang, S.; Ren, P.; Chen, Z.; Yin, D.; Ren, Z. Is ChatGPT Good at Search? Investigating Large Language Models as Re-Ranking Agents. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, EMNLP 2023, Singapore, December 6-10, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Izacard, G.; Grave, E. Leveraging passage retrieval with generative models for open domain question answering. arXiv preprint arXiv:2007.01282, arXiv:2007.01282 2020.

- Guu, K.; Lee, K.; Tung, Z.; Pasupat, P.; Chang, M. Retrieval augmented language model pre-training. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR; 2020; pp. 3929–3938. [Google Scholar]

- Borgeaud, S.; Mensch, A.; Hoffmann, J.; Cai, T.; Rutherford, E.; Millican, K.; van den Driessche, G.; Lespiau, J.B.; Damoc, B.; Clark, A.; et al. Improving Language Models by Retrieving from Trillions of Tokens. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, ICML 2022, 17-23 July 2022, Baltimore, Maryland, USA. PMLR, 2022, Vol. 162, Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, pp.

- Ma, X.; Gong, Y.; He, P.; Zhao, H.; Duan, N. Query Rewriting in Retrieval-Augmented Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Singapore, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Ram, O.; Levine, Y.; Dalmedigos, I.; Muhlgay, D.; Shashua, A.; Leyton-Brown, K.; Shoham, Y. In-context retrieval-augmented language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.00083, arXiv:2302.00083 2023.

- Yu, Z.; Xiong, C.; Yu, S.; Liu, Z. Augmentation-adapted retriever improves generalization of language models as generic plug-in. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.17331, arXiv:2305.17331 2023.

- Zhang, P.; Xiao, S.; Liu, Z.; Dou, Z.; Nie, J.Y. Retrieve Anything To Augment Large Language Models. CoRR, 2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yu, Y.; Wang, K.; Zhang, C. ARL2: Aligning Retrievers for Black-box Large Language Models via Self-guided Adaptive Relevance Labeling. 2024; arXiv:cs.CL/2402.13542]. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, N.F.; Lin, K.; Hewitt, J.; Paranjape, A.; Bevilacqua, M.; Petroni, F.; Liang, P. Lost in the Middle: How Language Models Use Long Contexts, 2023. arXiv:2307.03172.

- Cuconasu, F.; Trappolini, G.; Siciliano, F.; Filice, S.; Campagnano, C.; Maarek, Y.; Tonellotto, N.; Silvestri, F. R: Power of Noise, 2024; arXiv:cs.IR/2401.14887].

- Yang, H.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Cheng, N.; Li, M.; Xiao, J. PRCA: Fitting Black-Box Large Language Models for Retrieval Question Answering via Pluggable Reward-Driven Contextual Adapter. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, EMNLP 2023, Singapore, December 6-10, 2023.

- Press, O.; Zhang, M.; Min, S.; Schmidt, L.; Smith, N.; Lewis, M. Measuring and Narrowing the Compositionality Gap in Language Models. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2023, Singapore; 2023; pp. 5687–5711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoran, O.; Wolfson, T.; Ram, O.; Berant, J. Making Retrieval-Augmented Language Models Robust to Irrelevant Context. 2023; arXiv:cs.CL/2310.01558]. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, K.; Fang, M.; Yang, L.; Li, X.; Shang, L.; Xu, S.; Hao, J.; et al. Deep Research Agents: A Systematic Examination And Roadmap. A: Research Agents, 2025; arXiv:cs.AI/2506.18096]. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Li, Y.; Bei, Y.; Luo, J.; Wan, G.; Yang, L.; Xie, C.; Yang, Y.; Huang, W.C.; Miao, C.; et al. From Web Search towards Agentic Deep Research: Incentivizing Search with Reasoning Agents. I, 2025; arXiv:cs.IR/2506.18959]. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, R.; Peng, J. Comprehensive Survey of Deep Research: Systems, Methodologies, and Applications. 2025; arXiv:cs.AI/2506.12594]. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, S.; Song, H.; Wang, Y.; Ren, R.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, J.; Bai, F.; Deng, J.; Zhao, W.X.; Liu, Z.; et al. SimpleDeepSearcher: Deep Information Seeking via Web-Powered Reasoning Trajectory Synthesis. 2025; arXiv:cs.CL/2505.16834]. [Google Scholar]

- Rafailov, R.; Sharma, A.; Mitchell, E.; Ermon, S.; Manning, C.D.; Finn, C. Direct Preference Optimization: Your Language Model is Secretly a Reward Model. 2024; arXiv:cs.LG/2305.18290]. [Google Scholar]

- Schulman, J.; Wolski, F.; Dhariwal, P.; Radford, A.; Klimov, O. Proximal Policy Optimization Algorithms. 2017; arXiv:cs.LG/1707.06347]. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, Z.; Wang, P.; Zhu, Q.; Xu, R.; Song, J.; Bi, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, M.; Li, Y.K.; Wu, Y.; et al. DeepSeekMath: Pushing the Limits of Mathematical Reasoning in Open Language Models. 2024; arXiv:cs.CL/2402.03300]. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Liu, J.K.; Shen, W. REINFORCE++: An Efficient RLHF Algorithm with Robustness to Both Prompt and Reward Models. 2025; arXiv:cs.CL/2501.03262]. [Google Scholar]

- Li, K.; Zhang, Z.; Yin, H.; Zhang, L.; Ou, L.; Wu, J.; Yin, W.; Li, B.; Tao, Z.; Wang, X.; et al. WebSailor: Navigating Super-human Reasoning for Web Agent. 2025; arXiv:cs.CL/2507.02592]. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, W.; Tan, H.; Kuang, C.; Li, X.; Ren, X.; Zhang, C.; Chen, H.; Wang, Y.; Shang, L.; Yu, F.; et al. Pangu DeepDiver: Adaptive Search Intensity Scaling via Open-Web Reinforcement Learning. 2025; arXiv:cs.CL/2505.24332]. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Y.; Li, S.; Wu, C.; Liu, Z.; Fang, J.; Cai, H.; Zhang, A.; Wang, X. Search and Refine During Think: Autonomous Retrieval-Augmented Reasoning of LLMs. 2025; arXiv:cs.CL/2505.11277]. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, G.; Chen, Y.; Li, X.; Jin, J.; Qian, H.; Zhu, Y.; Mao, H.; Zhou, G.; Dou, Z.; Wen, J.R. Tool-Star: Empowering LLM-Brained Multi-Tool Reasoner via Reinforcement Learning. 2025; arXiv:cs.CL/2505.16410]. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.; Wen, Y.; Su, D.; Sun, F.; Chen, M.; Bao, C.; Lv, Z. Knowledgeable-r1: Policy Optimization for Knowledge Exploration in Retrieval-Augmented Generation, 2025; arXiv:cs.CL/2506.05154]. [Google Scholar]