1. Introduction

Alcohol is a worldwide used psychoactive and toxic substance. Data from the World Health Organisation (WHO) show that around 2.6 million deaths were caused by alcohol consumption in 2019 [

1]. Alcohol has a crucial role in several diseases; it can influence the function of the immune system, the microbiome, and increases the risk of inflammation, cirrhosis, and tumor formation. Acute alcohol consumption influences the function of the central nervous system, disrupts cell homeostasis, and affects several signal transduction pathways [

2].

During alcohol metabolism, highly reactive acetaldehyde is produced, which can induce DNA point mutations, double-strand breaks, and other structural changes in chromosomes. Furthermore, alcohol consumption induces the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), leading to oxidative stress, which contributes to ethanol-induced multi-organ damage [

2]. The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is responsible for the synthesis, folding, modification, and quality control of proteins. The alcohol-induced oxidative stress can lead to the formation of abnormally folded proteins. Unfolded and misfolded proteins accumulated in the ER lumen trigger the Unfolded Protein Response (UPR) to maintain the equilibrium of the ER [

3,

4]. This mechanism decreases protein synthesis, increases the activity of the chaperone proteins to correct misfolded proteins, and attenuates the ER stress [

4]. During UPR, three pathways are activated by the dissociation of the chaperone protein, glucose-regulated protein 78 (GRP78/BiP), from three sensor proteins: protein kinase RNA-like ER kinase (PERK), inositol-requiring enzyme 1 (IRE1), and activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6).

During UPR, BiP dissociates from PERK, leading to autophosphorylation and dimerization of the transmembrane protein. The activated PERK phosphorylates the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 (eIF2α), repressing the initiation of translation. Under ER stress, the eIF2α enhances the expression of activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4), inducing C/EBP-homologous protein (CHOP) transcription [

5]. The transcription factor CHOP induces apoptosis by diminishing the expression of anti-apoptotic and enhancing the levels of pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 protein family members [

6].

Dissociation of the BiP protein leads to autophosphorylation of the IRE1 protein and activation of its kinase and ribonuclease activities. The activated IRE1 cleaves the transcription factor X-box binding protein (XBP1) mRNA; thus, the activated spliced XBP1 regulates the expression of chaperone proteins and ER-associated degradation (ERAD) associated proteins (e.g. CHOP) [

6]. The activated IRE1 phosphorylates the stress kinase, Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), leading to the expression of Bim pro-apoptotic and Bcl-2 anti-apoptotic proteins [

3]. The p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (p38 MAPK) is also activated by IRE1, stimulating the phosphorylation of pro-apoptotic proteins [

6].

The transmembrane protein, ATF6 possesses a leucin-zipper transcription factor domain, which is cleaved under ER stress and regulates the expression of UPR genes (XBP1, CHOP, GRP78/BiP) [

5].

Members of the Bcl-2 protein family play a crucial role in the ER stress-induced apoptosis. The multi-domain pro-apoptotic proteins (e.g. Bak, Bax, Bok) form pores in the outer membrane of the mitochondrion to increase its permeability and mediate cytochrome c release. The Bcl-2 protein family members interact directly or indirectly with each other and influence their activity. Anti-apoptotic proteins (e.g. Bcl-2, Mcl-1, Bcl-xL, Bcl-w) bind to multi-domain proteins and limit their activity [

7]. Pro-apoptotic BH3-only proteins (e.g. Bim, Bid, Puma) bind with high affinity to all anti-apoptotic proteins, so they are potent initiators of apoptosis. Anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins can be neutralized by BH3-only proteins; thus, multi-domain pro-apoptotic proteins can form channels in the mitochondrial membrane [

8]. Cytochrome c release leads to the formation of the apoptosome and the activation of caspase-9 proteins, which are the executors of apoptosis [

9].

Cyclic AMP (cAMP)-response element-binding protein 1 (CREB) belongs to the family of leucine zipper transcription factors; its basic leucine zipper (bZIP) DNA binding domain recognizes the cAMP response enhancer element (CRE) of the promoter [

10]. The nuclear protein, CREB is expressed ubiquitously and suggested to regulate more than 4000 genes in several tissues, including the brain. Its activation leads to increased neuronal regeneration, neuronal survival, and enhances several neuronal processes [

11]. CREB regulates the expression of anti-apoptotic and pro-apoptotic members of the Bcl-2 protein family [

12].

We have investigated the role of CREB transcription factor overexpression in ethanol-induced ER stress and apoptosis in PC12 cells, a widely used model system to study various neuronal processes. In our previous experiments on PC12 cells, we have shown that various stressors such as serum starvation, anisomycin, and nitrosative agents induce apoptosis via caspase-dependent PKR activation, eIF2α phosphorylation, and intrinsic and extrinsic pathways [

13,

14]. These results highlight the relevance of this model for studying stress-related signaling and support the current investigation of the role of CREB in ethanol-induced ER stress.

2. Materials and Methods

Cell Cultures

The wild-type PC12 (wtPC12) rat pheochromocytoma cell line was isolated from an adrenal medulla tumor (Greene and Tischler, 1976), and it was a gift from G. M. Cooper. Cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, USA) containing 4,500 mg/l glucose, 4 Mmol L-glutamine, and 110 mg/l sodium pyruvate, at 37 °C and 5% CO

2. The medium was supplemented with 10 % horse serum and 5 % fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA). PC12 cells overexpressing CREB (PC12-CREB, established by M. Pap, see Balogh et al 2014) [

15] were cultured in the same medium containing 200 µg/ml geneticin (G418, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). Both cell lines were treated with absolute ethanol (Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, USA) at a concentration of 4 mg/ml for 24 and 48 hours.

Reverse Transcription Quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

106 cells were seeded onto 100-mm plates, harvested the next day and lysed in 200 µl TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen Waltham, MA, USA). Total RNA was isolated by Direct-zol RNA Miniprep Kit (Zymo Research) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Sample concentrations were determined by a NanoDrop One Spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), and 1000 ng RNA was reverse transcribed into complementary DNA by qPCRBIO cDNA Synthesis Kit (PCR Biosystems, London UK) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The following cDNA synthesis program was used: 25 °C 5 min 30 s, 42 °C 55 min, 48 °C 5 min, and 80 °C 5 min. 1 µg cDNA and 10 pM/µL primers were used to perform the qPCR reaction by a CFX RT-PCR thermocycler (BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA). The program was as follows: initial denaturation 95 °C 3 min, 40 cycles of 95 °C 10 s, 55 °C 30 s, 72 °C 1 min. All samples were amplified in duplicate, and relative gene expression was analyzed using CFX Maestro Software (BioRad), and TATA-box binding Protein (TBP) was used as endogenous control. PrimerQuest software (version 2.2.3), obtained from the IDT website (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, Iowa, USA), was used to design primer pairs. To detect the endogenous CREB expression, the following primer pairs were used: forward primer 5’-GACTGGCTTGGCCACAA-3’, reverse primer 5’- TGTAGTTGCTTTCAGGCAGTT –3’.

To investigate exogenous CREB expression, we designed a primer sequence found only in the plasmid vector (forward primer 5’-GACTGGCTTGGCCACAA-3’, reverse primer 5’- GGCATAGATACCTGGGCTAATG-3’).

Cell Viability Assay

For the detection of cell viability ATP assay (Promega CellTiter-Glo® 2.0 Cell Viability Assay, Madison, WI USA) was used. 2000 PC12 and 1000 PC12-CREB cells per well were plated on a white, flat-bottom 96-well-plate (Greiner, Kremsmünster, Österreich) coated with poly-L-lysine. The next day, the cells were treated with ethanol at 4 mg/ml concentration for 48 hours, and for 24 hours the next day. Measurements were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Luminescence was detected by FLUOstar-OPTIMA V2.20 (BMG Labtech, Offenburg, Germany) luminometer.

Apoptosis Assay (Nuclear Morphology by Hoechst Staining)

105 cells were plated in 24-well plates coated with poly-L-lysine (Sigma St. Louis, MO, USA). The next day, cells were treated with 4 mg/ml ethanol for 48 hours, and for 24 hours the following day. After treatment, cells were fixed with 4 % paraformaldehyde in 1x PBS. The cell nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 (Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, USA) fluorescent DNA dye dissolved in 1x PBS at a concentration of 0,5 μg/ml. Samples were mounted with Vectashield (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) anti-fading mounting medium.

200 cells/sample were counted in randomly chosen view fields to determine the ratio of apoptotic nuclei using an Olympus BX61 fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Center Valley, PA, USA).

Western Blotting Assay

5x106 cells were plated onto 100-mm plates and treated with 4 mg/ml ethanol the next day for 24 and 48 hours. After treatment, cells were harvested and lysed with M-Per Protein Extraction Buffer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with phosphatase inhibitor cocktail and protease inhibitor (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Lysates were boiled for 5 minutes, and 40 µg protein was electrophoresed on 12 % SDS-polyacrylamide gel. After electrophoresis, proteins were transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (PVDF, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, Ill., USA) and blots were blocked with 5% non-fat milk in 1x PBS for 1 hour. After blocking, the membranes were treated with the appropriate primary antibodies according to the manufacturer’s protocols. The following primary antibodies were used in 1:1000 dilution: anti-BiP, anti-CHOP, anti-ATF-6, anti-P-JNK, anti-P-p38, anti-P-p53, anti-Bim, anti-Puma, anti-cleaved Caspase-3, anti-Mcl-1, anti-P-Bad, anti-CREB, anti-β-actin (Cell Signaling Danvers, MA, USA). After washing the blots five times in 1x TBS-T 0,1% Tween-20 buffer for 5 minutes, horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (anti-rabbit, anti-mouse in 1:2000 dilution, Cell Signaling Danvers, MA, USA) were used to detect bound primary antibodies. The results were visualized by G-Box gel documentation system (Syngene, Synoptics Cambridge, UK) after washing the membranes ten times for 5 minutes.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted with the statistical analysis program PAST v2.17c and the significance of the data was analyzed by the Kruskal–Wallis test. The normal distribution was determined by Saphiro-Wilk test. P < 0.05 value was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

Quantification of Exogenous CREB Expression in Stable Transfected PC12-CREB Cells

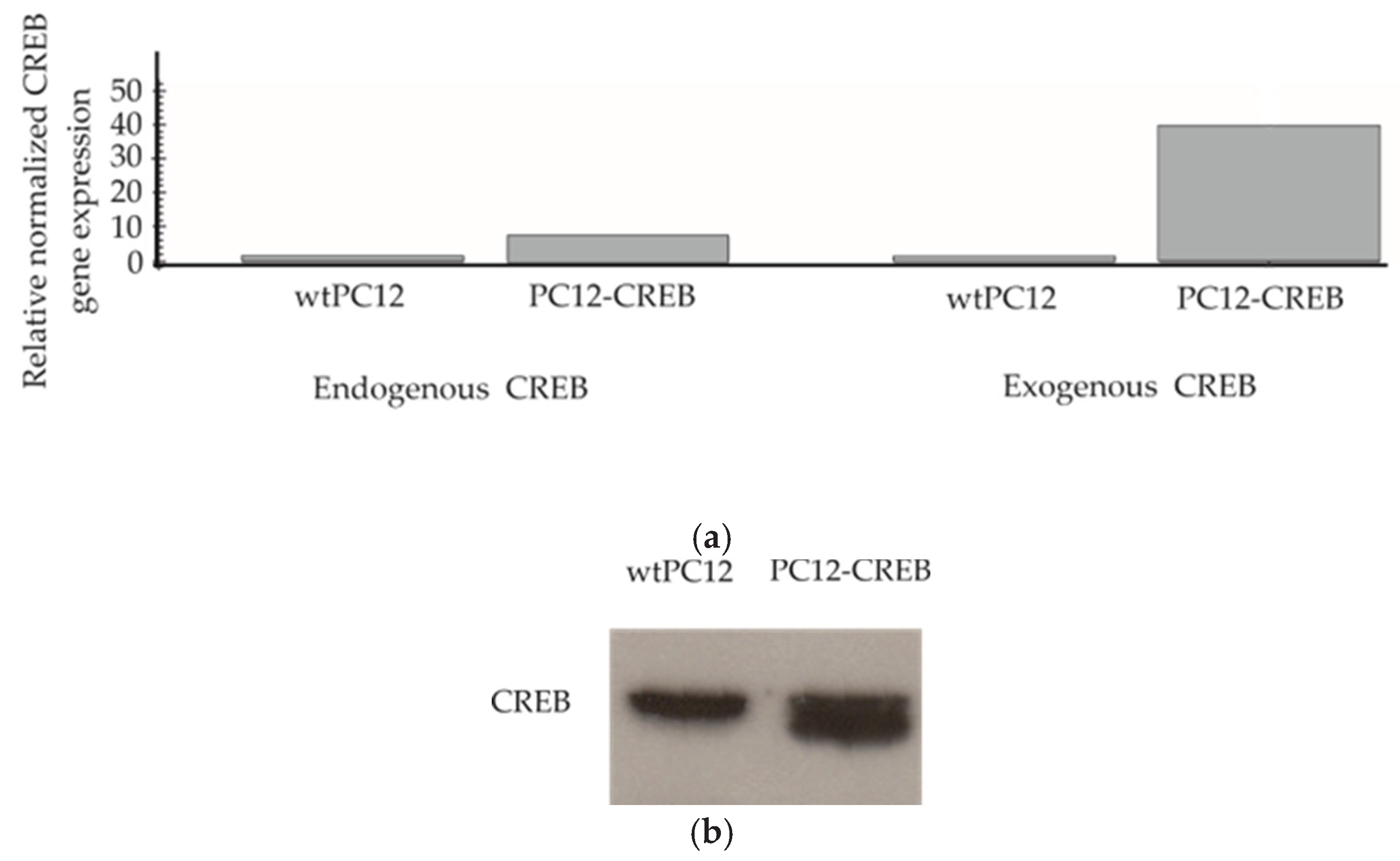

Reverse transcription real-time PCR (RT-qPCR) was used to examine the expression of endogenous CREB and exogenous CREB to demonstrate that stable transfected PC12-CREB cells overexpress CREB mRNA (

Figure 1.a). In wild-type PC12 (wtPC12) cells, neither endogenous CREB nor exogenous CREB mRNA showed elevated levels. In PC12 cells transfected with CREB-expressing plasmids (PC12-CREB), endogenous CREB mRNA expression showed low levels similar to wtPC12 cells. The level of exogenous CREB in transfected PC12-CREB cells showed a significant increase of approximately 40-fold compared to wtPC12 cells. In conclusion, PC12-CREB cells overexpress CREB transcription factor mRNA, whereas wtPC12 cells do not. The expression of CREB protein was also detected by Western blot analysis in both cell lines (

Figure 1.b). PC12-CREB cells express CREB protein at a higher amount compared to the wtPC12 cells.

Effect of Ethanol on the Viability of wtPC12 and PC12-CREB Cells

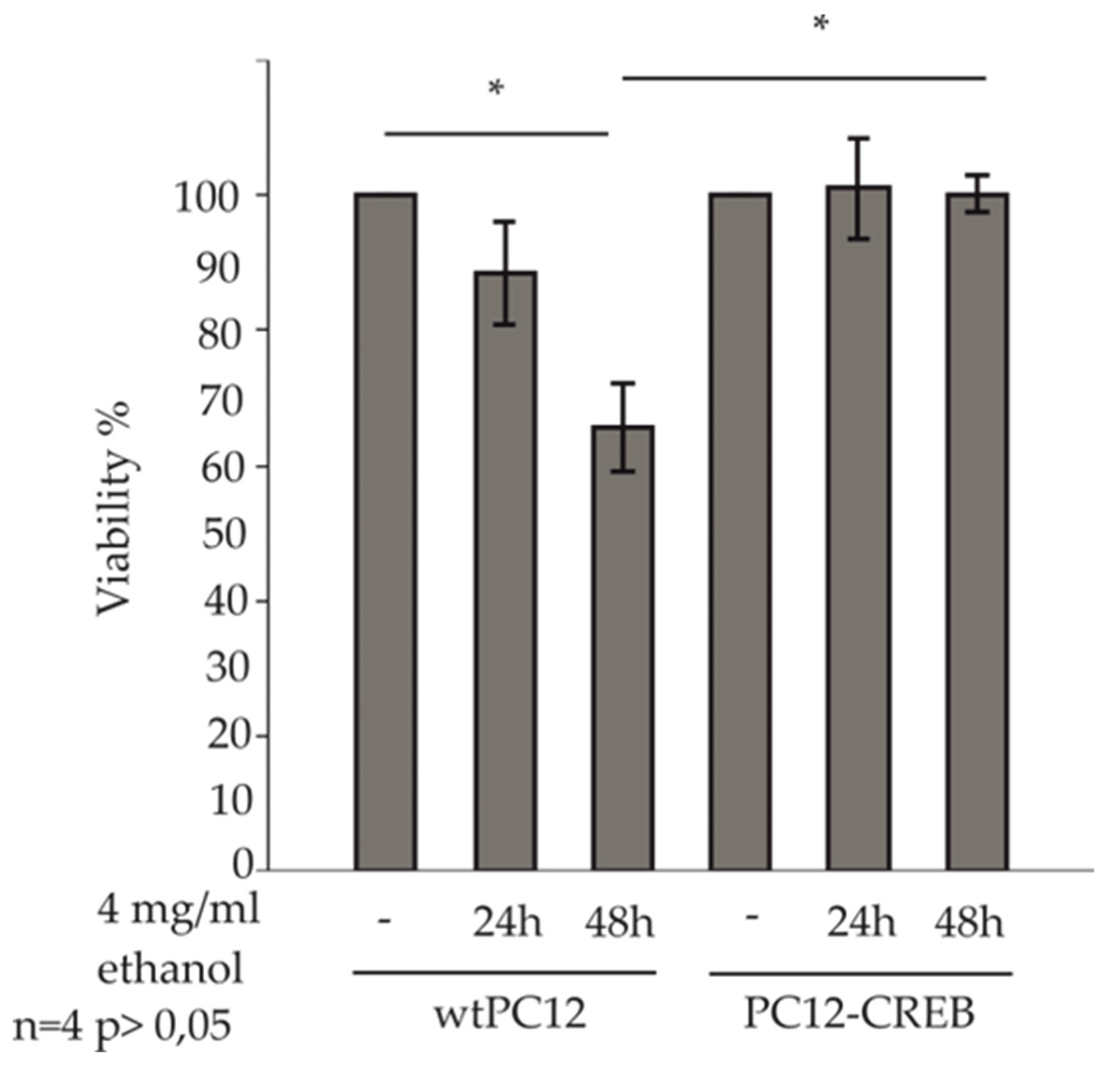

The ATP assay is a widely used and accepted method to study cell viability. This method was used to determine whether alcohol has a differential effect on the viability of wtPC12 and CREB-transfected PC12 cells (

Figure 2).

In our treatments, 4 mg/ml ethanol concentration was used, this was determined according to the scoring in Physiological effects of various blood alcohol levels (Amitava Dasgupta Ph.D., in Alcohol and its Biomarkers, 2015), where a blood alcohol concentration of 0,4 % causes stupor, coma, respiratory depression, hypothermia and is highly toxic to cells.

The viability of treated cells was normalized to the viability of untreated control cells, respectively. Viability of wtPC12 cells decreased after 24 h of ethanol treatment compared to untreated control cells. 48 h of ethanol treatment caused a significant decrease in ATP concentration in wild-type PC12 cells. ATP concentration of wtPC12 cells decreased to 68%, which represents a significantly lower viability compared to untreated control cells. PC12-CREB cell viability did not change after 24 h and 48 h of treatment compared to control cells. The viability of PC12-CREB cells was significantly higher than that of wtPC12 cells after 48 h of treatment.

Effect of Ethanol on Apoptosis in Wild-Type and CREB Overexpressing Cells

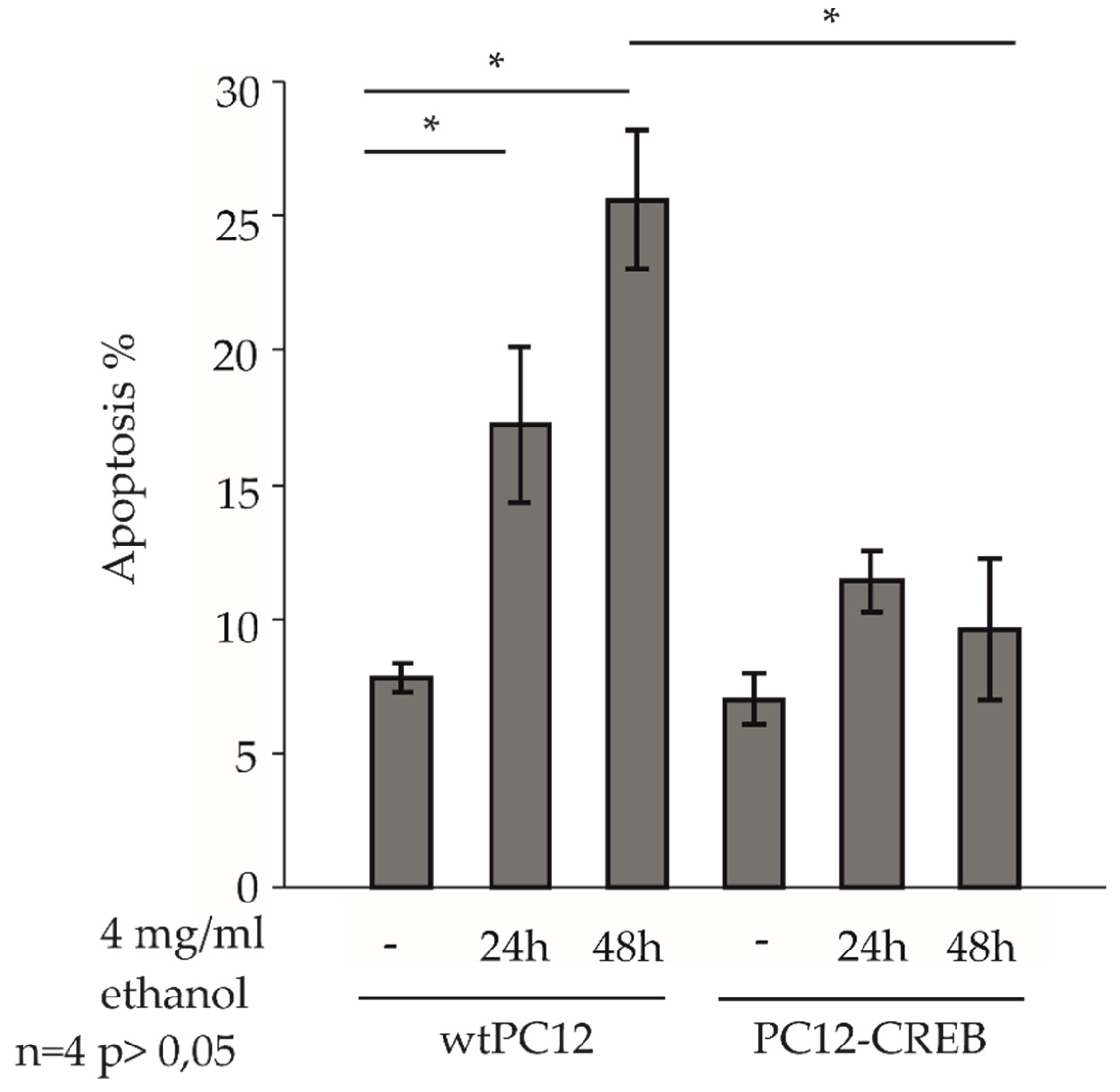

Control and 4 mg/ml ethanol-treated wtPC12 and PC12-CREB cells for 24 and 48 h, were observed in a fluorescence microscope after staining with Hoechst dye, and the percentage of apoptotic cells was counted (

Figure 3.). Untreated cells in both cell lines showed approximately 7-8 % apoptotic levels. After 24 and 48 hours of ethanol treatment, the percentage of apoptotic cells increased in wtPC12 cells. The 24-hour ethanol treatment evoked a significantly higher rate of apoptosis (17 %) compared to untreated wtPC12 cells. The prolonged treatment induced apoptosis in approximately 25 % of the cells, which was significantly higher than in the control cells.

In the stable transfected PC12-CREB cell line, ethanol treatment increased the percentage of apoptotic cells (10-11%) compared to control cells, but was not as pronounced as in the wild-type cell line. The levels of apoptotic cells were not significantly different after 24 or 48 hours of ethanol treatment; the level of apoptotic cells was not as high (10%) as after 24 hours of treatment.

The 48-hour ethanol treatment caused a significantly higher rate of apoptosis in wtPC12 cells than in PC12-CREB cells.

Effects of Ethanol Treatment on ER Stress and Apoptosis

Dissociation of BiP protein from the ER transmembrane sensor proteins is a key step in the ER stress. BiP levels were increased in wtPC12 cells after 24 and 48 hours of ethanol treatment compared to untreated cells. In PC12-CREB cells, Bip expression was decreased by ethanol treatment compared to control samples. ATF6 sensor protein expression was increased after 24 hours of alcohol treatment in both wtPC12 and PC12-CREB cells, but to a much lower extent in the latter CREB overexpressing cell line. The apoptosis regulator transcription factor, CHOP level is also higher after ethanol treatment in the wild-type cells compared to the control cells, while it did not change in the stable CREB-transfected cells. The p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (p38 MAPK) and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) play important roles in mediating ER stress. Both kinases were activated after 48 hours of ethanol treatment in the wtPC12 cells. JNK underwent a strong phosphorylation in wild-type cells after 48 hours of treatment, while the rate of phosphorylation in CREB-transfected cells showed markedly lower levels. 48 hours of ethanol treatment caused an increased p53 phosphorylation in wtPC12 and PC12-CREB cells compared to the untreated cells, but the elevation was higher in the wild-type cells (

Figure 4a). The expression of apoptosis regulator Bcl-2 family member proteins was also influenced by the ethanol treatment. Anti-apoptotic Mcl-1 protein did not show an elevation after ethanol treatment in wtPC12 cells, while the 48-hour ethanol treatment induced the expression of this protein in PC12-CREB cells. Bim is a BH3-only domain pro-apoptotic protein, which is involved in the inhibition of the anti-apoptotic proteins. In the wtPC12 cells, the 24-hour ethanol treatment caused an elevation in the Bim level, while the 48-hour treatment had a stronger effect on Bim expression. It is visible, that CREB overexpression increases the Bim level in the PC12-CREB cells, but the ethanol treatment decreases the Bim expression. Puma, a pro-apoptotic protein showed a higher expression in the wild-type cells after 24 hours treatment and the elevation was more pronounced after 48 hours. The PC12-CREB cells also had an elevated Puma protein level compared to the control, but not as prominent as in the wild-type cells. Bad pro-apoptotic protein underwent phosphorylation after 48 hours ethanol treatment in the wild- type cells, but in the stable transfected cells the phosphorylation status was not changed compared to the untreated cells. Caspase-3 is an important executor of apoptosis [

16], it showed an elevated levels of the cleaved form in both ethanol-treated cell lines compared to the untreated cells, but in the wtPC12 cells, the elevation was more prominent (

Figure 4b).

4. Discussion

Alcohol consumption influences behavioral and cognitive functions in the brain, and compulsive alcohol intake triggers cellular stress responses in the cells that affect the cAMP signaling pathway [

17]. CREB is a leucine zipper transcription factor expressed ubiquitously in various tissues, including the brain, and it binds to cAMP response element (CRE) sequences in gene promoters [

21].

Previous studies report conflicting effects of alcohol on CREB activation. Some findings suggest that alcohol exposure increases CREB phosphorylation, thereby inducing target gene expression [

17]. However, other research indicates that alcohol exposure attenuates CREB activity by reducing intracellular cAMP levels, possibly by inhibiting adenylate cyclase or stimulating phosphodiesterase activity. The suppressive effect of alcohol on CREB activity may contribute to ethanol-induced stress [

18]. Our findings align with the latter, showing that ethanol exposure decreases CREB activation, leading to attenuation of pro-survival genes and increased cellular vulnerability, which could contribute to neurodegeneration in the brain [

19].

Protein misfolding in the ER causes BiP to dissociate from ATF6, allowing ATF6 to translocate to the nucleus and induce ER stress response genes. Increased BiP expression enhances ER protein-folding capacity and mitigates ER stress [

22]. Short-term ethanol treatment increased ATF6 levels, inducing BiP expression in wtPC12 cells. Interestingly, CREB overexpression reduced both ATF6 and BiP levels despite alcohol exposure. Since ATF6 mediates antioxidant effects by inducing the expression of antioxidant proteins that eliminate ROS and reduce ER stress, this modulation may influence neuronal cell death [

22]. Previous studies have noted that ATF6, as a transcription factor induces the expression of UPR genes such as CHOP [

6]. The results of this study indicate that increased levels of ATF6 following alcohol exposure upregulate CHOP genes, while CREB overexpression decreases this effect.

Environmental stress activates the JNK and p38 MAPK signaling pathways [

20]. In our experiments, alcohol exposure increased phosphorylation of JNK stress kinase in wtPC12 cells, but CREB overexpression diminished JNK activation. Similarly, CREB overexpression reduced the activation of p38 MAPK, although this effect was less pronounced compared to JNK. P38 MAPK activates CHOP, while JNK activation can also modulate CHOP activation, which leads to apoptosis [

6]. Our results demonstrate that alcohol exposure increases CHOP levels, and CREB overexpression decreases this effect. As a transcription factor, CHOP regulates the expression of pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family member genes [

6]. In our experiments, CHOP downregulates Mcl-1 anti-apoptotic proteins following alcohol exposure, while CREB overexpression decreases CHOP levels, leading to downregulation of Mcl-1 and the attenuation of apoptosis. Alcohol exposure stimulates the upregulation of Puma pro-apoptotic genes by CHOP, and overexpression of CREB diminishes this effect. Caspase-3 is one of the main executors of apoptosis. This study has found that CREB overexpression decreased caspase-3 activation despite ethanol treatment. These results were confirmed by reduced rate of apoptosis in CREB overexpressing cells and increased viability following ethanol exposure. In general, it therefore seems that CREB overexpression decreases apoptosis rates and increases cell viability.

CREB is known to promote neuroprotective effects by regulating anti-apoptotic proteins [

12]. In our study, CREB-overexpressing cells exhibited increased expression of the anti-apoptotic protein Mcl-1, which plays a critical role in maintaining cell viability. This was supported by cell viability and apoptosis assays showing higher survival and reduced apoptosis rates in CREB-overexpressing cells despite alcohol exposure. Mcl-1 protein exerts its anti-apoptotic function by binding to pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family member proteins such as Puma and Bim [

23]. Consistent with this, CREB overexpression increased Mcl-1 levels while decreasing Puma and Bim expression, resulting in attenuated apoptosis.

Ethanol treatment appeared to reduce the effect of CREB on the expression of BiP and Bim proteins, suggesting that alcohol may interfere with some CREB-mediated protective mechanisms.

5. Conclusions

The cell-damaging effects of ethanol are partly mediated through the activation of ER stress and subsequent apoptosis pathways. Overexpression of the transcription factor CREB is able to attenuate these negative effects, possibly through several targets, including inhibition of CHOP and JNK signaling pathways and enhancement of anti-apoptotic gene expression.

Our results support a potential protective role for CREB in ethanol-induced neuronal damage and may contribute to a better understanding of alcohol neurotoxicity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, M.P. and M.N.; investigation, M.N., B.B., H.L. and P.K-M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.P. and M.N.; writing—review and editing, A.M., T.A.R.; visualization, M.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| WHO |

World Health Organisation |

| ROS |

reactive oxygen species |

| ER |

endoplasmic reticulum |

| UPR |

Unfolded Protein Response |

| GRP78/BiP |

glucose-regulated protein 78 |

| PERK |

protein kinase RNA-like ER kinase |

| IRE1 |

inositol-requiring enzyme 1 |

| ATF6 |

activating transcription factor 6 |

| eIF2α |

eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 |

| ATF4 |

activating transcription factor 4 |

| CHOP |

C/EBP-homologous protein |

| XBP1 |

X-box binding protein |

| ERAD |

ER-associated degradation |

| JNK |

Jun N-terminal kinase |

| p38 MAPK |

p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| CREB |

Cyclic AMP (cAMP)-response element-binding protein 1 |

| CRE |

cAMP response enhancer element |

| wtPC12 |

wild-type PC12, rat pheochromocytoma cell line |

| FBS |

fetal bovine serum |

| PC12-CREB |

PC12 cells overexpressing CREB |

| TBP |

TATA-box binding Protein |

| PVDF |

polyvinylidene difluoride membrane |

| RT-qPCR |

Reverse transcription real-time PCR |

References

- https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/alcohol.

- Rumgay, H., Murphy, N., Ferrari, P., & Soerjomataram, I. (2021). Alcohol and cancer: Epidemiology and biological mechanisms. In Nutrients (Vol. 13, Issue 9). MDPI. [CrossRef]

- Na, M., Yang, X., Deng, Y., Yin, Z., & Li, M. (2023). Endoplasmic reticulum stress in the pathogenesis of alcoholic liver disease. PeerJ, 11. [CrossRef]

- Yang, F., & Luo, J. (2015). Endoplasmic reticulum stress and ethanol neurotoxicity. In Biomolecules (Vol. 5, Issue 4, pp. 2538–2553). MDPI AG. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X., Shi, C., He, M., Xiong, S., & Xia, X. (2023). Endoplasmic reticulum stress: molecular mechanism and therapeutic targets. In Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy (Vol. 8, Issue 1). Springer Nature. [CrossRef]

- Hu, H., Tian, M., Ding, C., & Yu, S. (2019). The C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP) transcription factor functions in endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis and microbial infection. In Frontiers in Immunology (Vol. 10, Issue JAN). Frontiers Media S.A. [CrossRef]

- Warren, C. F. A., Wong-Brown, M. W., & Bowden, N. A. (2019). BCL-2 family isoforms in apoptosis and cancer. In Cell Death and Disease (Vol. 10, Issue 3). Nature Publishing Group. [CrossRef]

- Gogada, R., Yadav, N., Liu, J., Tang, S., Zhang, D., Schneider, A., Seshadri, A., Sun, L., Aldaz, C. M., Tang, D. G., & Chandra, D. (2013). Bim, a proapoptotic protein, up-regulated via transcription factor E2F1-dependent mechanism, functions as a prosurvival molecule in cancer. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 288(1), 368–381. [CrossRef]

- Newton, K., Strasser, A., Kayagaki, N., & Dixit, V. M. (2024). Cell death. In Cell (Vol. 187, Issue 2, pp. 235–256). Elsevier B.V. [CrossRef]

- Steven, A., Friedrich, M., Jank, P., Heimer, N., Budczies, J., Denkert, C., & Seliger, B. (2020). What turns CREB on? And off? And why does it matter? In Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences (Vol. 77, Issue 20, pp. 4049–4067). Springer Science and Business Media Deutschland GmbH. [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, M. A. R., Haq, M. M., Lee, J. H., & Jeong, S. (2024). Multi-faceted regulation of CREB family transcription factors. In Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience (Vol. 17). Frontiers Media SA. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L., Zhang, L., & Chow, B. K. C. (2019). Secretin Prevents Apoptosis in the Developing Cerebellum Through Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL. Journal of Molecular Neuroscience, 68(3), 494–503. [CrossRef]

- Pap, M., & Szeberényi, J. (2008). Involvement of proteolytic activation of protein kinase R in the apoptosis of PC12 pheochromocytoma cells. Cellular and Molecular Neurobiology, 28(3), 443–456. [CrossRef]

- Varga, J., Bátor, J., Péter, M., Árvai, Z., Pap, M., Sétáló, G., & Szeberényi, J. (2014). The role of the p53 protein in nitrosative stress-induced apoptosis of PC12 rat pheochromocytoma cells. Cell and Tissue Research, 358(1), 65–74. [CrossRef]

- Balogh, A., Németh, M., Koloszár, I., Markó, L., Przybyl, L., Jinno, K., Szigeti, C., Heffer, M., Gebhardt, M., Szeberényi, J., Müller, D. N., Sétáló, G., & Pap, M. (2014). Overexpression of CREB protein protects from tunicamycin-induced apoptosis in various rat cell types. Apoptosis, 19(7), 1080–1098. [CrossRef]

- Eskandari, E., & Eaves, C. J. (2022). Paradoxical roles of caspase-3 in regulating cell survival, proliferation, and tumorigenesis. In Journal of Cell Biology (Vol. 221, Issue 6). Rockefeller University Press. [CrossRef]

- Mons, N., & Beracochea, D. (2016). Behavioral neuroadaptation to alcohol: From glucocorticoids to histone acetylation. In Frontiers in Psychiatry (Vol. 7, Issue OCT). Frontiers Media S.A. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z., Liu, Y., Gao, R., Li, H., Dunn, T., Wu, P., Smith, R. G., Sarkar, P. S., & Fang, X. (2014). Ethanol suppresses PGC-1α expression by interfering with the cAMP-CREB pathway in neuronal cells. PLoS ONE, 9(8). [CrossRef]

- Lee, H. Y., Yang, B.-C., Lee, E.-S., Chung, J. I., Koh, P. O., Park, M. S., & Kim, M. O. (2011). Modulation by the GABA B receptor siRNA of ethanol-mediated PKA-α, CaMKII, and p-CREB intracellular signaling in prenatal rat hippocampal neurons . Anatomy & Cell Biology, 44(3), 210. [CrossRef]

- May, V., Lutz, E., MacKenzie, C., Schutz, K. C., Dozark, K., & Braas, K. M. (2010). Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP)/PAC 1HOP1 receptor activation coordinates multiple neurotrophic signaling pathways: Akt activation through phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase γ and vesicle endocytosis for neuronal survival. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 285(13), 9749–9761. [CrossRef]

- Sen, N. (2019). ER Stress, CREB, and Memory: A Tangled Emerging Link in Disease. In Neuroscientist (Vol. 25, Issue 5, pp. 420–433). SAGE Publications Inc. [CrossRef]

- Jin, J. K., Blackwood, E. A., Azizi, K., Thuerauf, D. J., Fahem, A. G., Hofmann, C., Kaufman, R. J., Doroudgar, S., & Glembotski, C. C. (2017). ATF6 Decreases Myocardial Ischemia/Reperfusion Damage and Links ER Stress and Oxidative Stress Signaling Pathways in the Heart. Circulation Research, 120(5), 862–875. [CrossRef]

- Donadoni, M., Cicalese, S., Sarkar, D. K., Chang, S. L., & Sariyer, I. K. (2019). Alcohol exposure alters pre-mRNA splicing of antiapoptotic Mcl-1L isoform and induces apoptosis in neural progenitors and immature neurons. Cell Death and Disease, 10(6). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).