1. Introduction

During the past two decades, climbing has transformed from a niche activity to a rapidly expanding global sport. The International Federation of Sport Climbing (IFSC) estimates that approximately 25 million people worldwide participate regularly in climbing, reflecting its power of attraction across different age groups and regions. In the time between 2001 and 2012, the global number of climbing facilities and climbers increased by almost 50% [

1]. The sport’s ascent is further accelerated by its growing media presence and its recognition on the international stage, including its debut at the 2020 Olympic Games in Tokyo [

2]. This event showcased the sport’s unique combination of athleticism, strategy, and creativity, captivating audiences and inspiring a new generation of climbers. Its continued inclusion in Paris 2024 has solidified climbing’s status as a mainstream sport, with the potential to attract even more participants and fans. Since its inclusion in the Olympic program, the competition format and scoring system in sport climbing have undergone significant transformations, resulting in Speed Climbing being established as a separate discipline [

3].

Looking ahead, the Olympic Games 2028 in Los Angeles will mark a significant milestone for the sport: for the first time, all three disciplines will be held as fully separated events, each awarding its own set of medals. This new format will allow the competing countries to win up to three medals in climbing, further enhancing the sport’s visibility and greater recognition for the unique skills required in each discipline.

These changes reflect the specific demands of each climbing discipline: Recent studies highlight substantial differences in exercise characteristics and physiological load [

4,

5], and emphasize the unique requirements of Speed Climbing. Draga et al. [

6] highlight the importance of optimizing body composition and proportions for peak performance in this discipline. Krawczyk et al. [

7] underline the crucial role of biomechanical parameters such as limb strength and power.

Particularly in Speed Climbing, performance has seen remarkable advances. At the Paris 2024 Olympics, both men’s and women’s records were shattered, with finishing times dropping from 6.97 s to 6.06 s for women and from 5.45 s to 4.74 s for men [

8], signaling a breakthrough after stagnation in the years following Tokyo 2020.

These improvements are attributed to movement efficiency, such as optimization of motion patterns in the start section and route strategies, as well as enhanced training methods [

9]. To maintain this rapid progress and further enhance performance of Speed Climbing athletes, the usage of measurement technology and automated analysis tools is essential. These systems provide precise, objective data that support both researchers - investigating biomechanics and exercise physiology - as well as practitioners in making informed decisions and optimizing training methods [

10]. Tools such as video analysis and motion tracking systems have already been successfully integrated in well-established sports, offering valuable insights into athletic performance, identifying areas for improvement, and enabling coaches to tailor training programs more effectively. Their demonstrated success in other sports [

11,

12] highlights the potential for accelerating the development of sport climbing.

Recent advancements in sports science have been driven by the development of automated video analysis systems by the integration of machine learning and computer vision techniques. This enabled a better understanding of athletic performance across different sport disciplines and helped to prevent injuries by identifying risky movement patterns early on [

13]. In particular, the use of Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) for human pose estimation has revolutionized the field and has become a cornerstone for biomechanical analysis, allowing for the extraction of various kinematic and kinetic parameters from video recordings [

14]. The application of deep learning and CNNs, is distinguished, among others, by its ability to automatically extract features from video data, outperforming traditional handcrafted feature approaches in a variety of sports contexts. In soccer, for instance, CNN-based frameworks have been successfully deployed for event detection and classification, enabling the identification of tactical patterns and key actions in video sequences [

15]. But also in a more general context, the deployment of CNNs has shown significant improvements in the analysis of human motion. In upper limb motion analysis, CNNs have demonstrated high accuracy in classifying movement types and detecting kinematic differences between healthy study participants and ones after stroke, providing objective and reproducible assessments that surpass conventional observation methods [

16]. Moreover, CNN-based models are increasingly being used to analyze gait and limb coordination in among others athletic settings [

17]. The integration of such technologies in sports not only enhances performance analysis but also opens new avenues for personalized feedback and targeted training deployments.

Since the introduction of Speed Climbing as an Olympic discipline, the interest in performance analysis and optimization has grown significantly and so has the research in this area. For example, a study have demonstrated how video analysis can provide detailed insights into trajectory efficiency, coordination strategies and movement fluency among elite climbers, offering non-invasive means to access different aspects of performance [

18]. While traditional video analysis methods have provided valuable insights into movement strategies and efficiency, advances in deep learning have enabled even more precise results. A framework based on 3D Residual Networks in [

19] presents automated classification and analysis of Speed Climbing videos. Using an extensive annotated dataset of recorded runs, this approach applies 3D convolutions and residual connections to capture and evaluate different climbing state combinations.

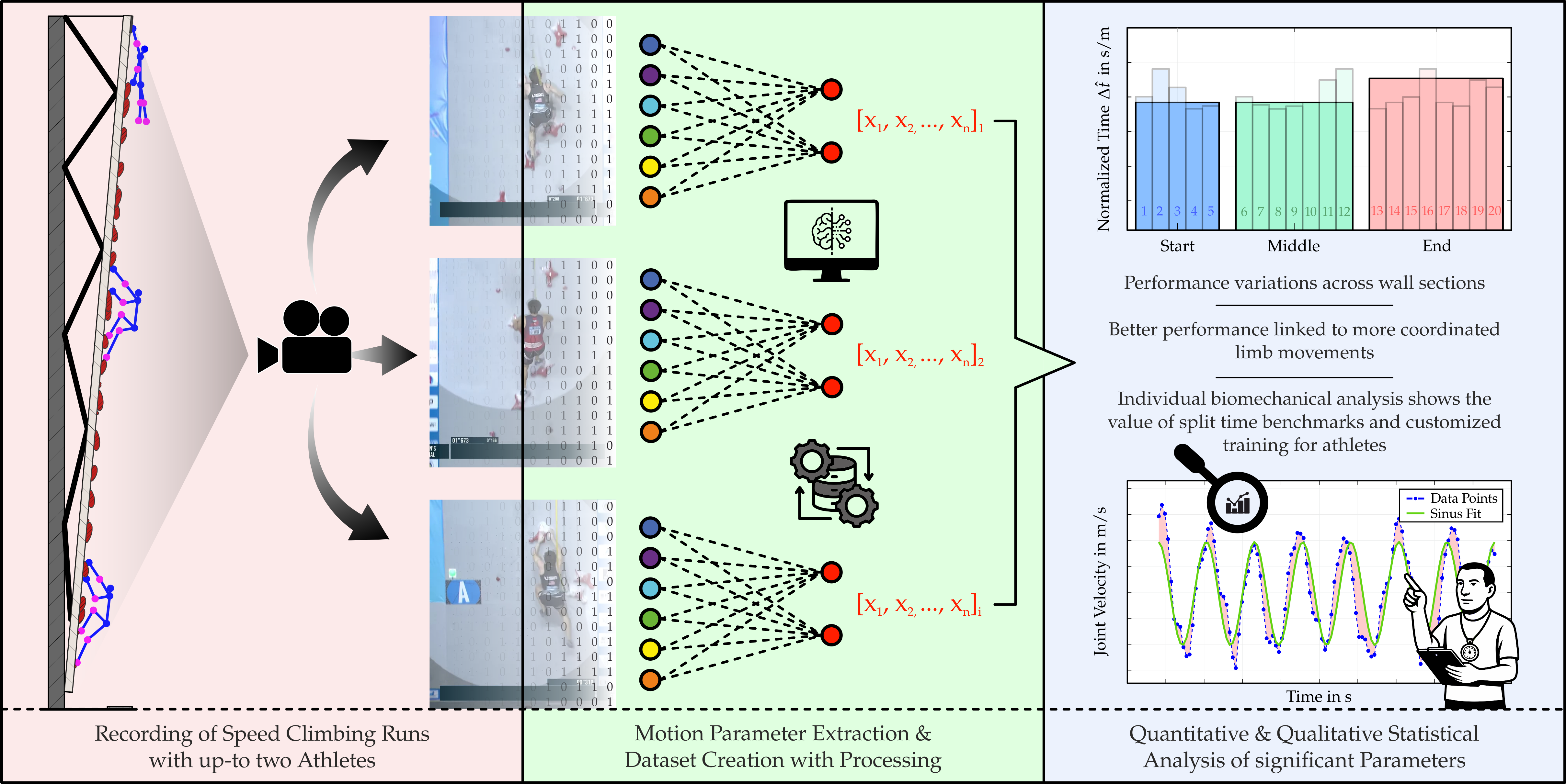

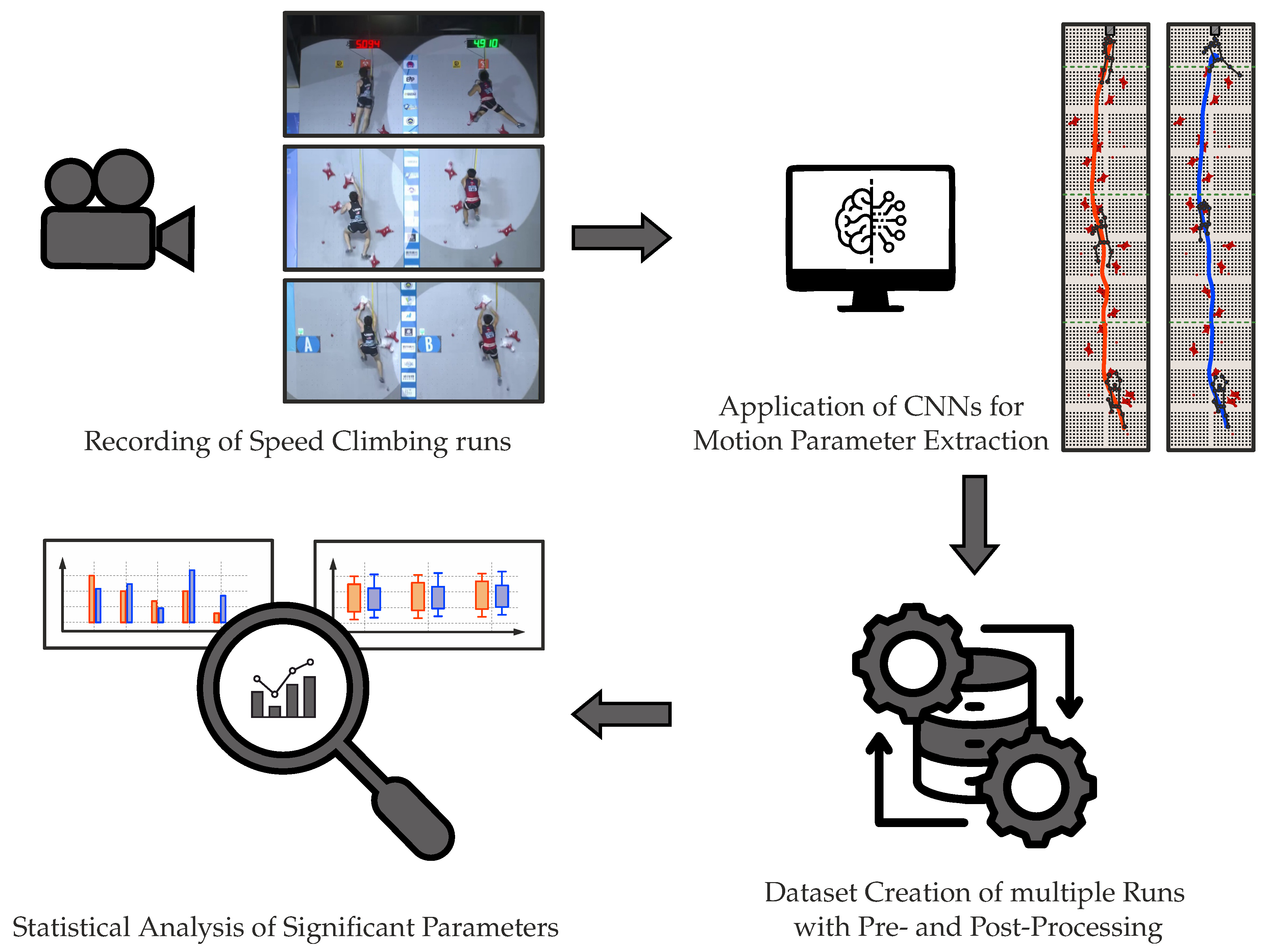

This paper presents an analysis of movement patterns in Speed Climbing using a comprehensive dataset consisting of nearly 900 competition recordings involving approximately 250 athletes. Both quantitative and qualitative evaluations are conducted to gain deeper insights into the performance of Speed Climbing athletes. The study investigates the hypothesis that the athletes’ split times and limb coordination are decisive factors for success and, therefore, correlate with the end time. To be precise, the following research questions are addressed:

How can the analysis of split times and comparison with elite speed climbers serve as a basis for targeted adjustments to training methods that lead to measurable improvements in performance?

Does a proper coordination of individual limb movements correlate with competitive success in Speed Climbing?

Based on this, the methods used to determine the mentioned movement parameters are first presented, followed by a detailed analysis of the results. The findings are then discussed in the context of existing literature, and their implications for training and performance optimization in Speed Climbing are highlighted.

4. Discussion

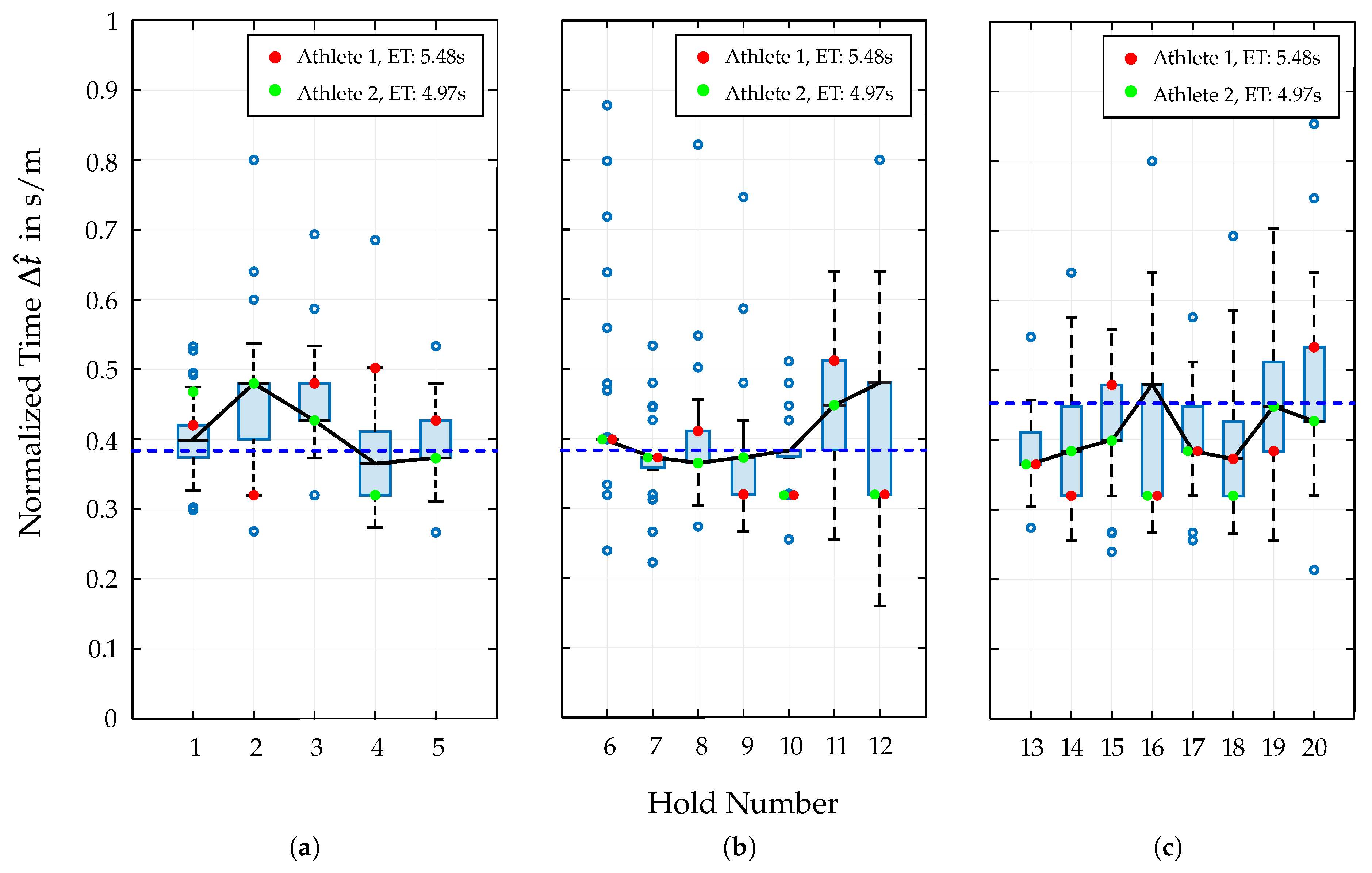

The presented methods and results provide a comprehensive analysis of Speed Climbing athletes’ performance, focusing on a quantitative evaluation of motion patterns in the start, middle and end section of the wall by analyzing split times. The runs of various athletes from a dataset filtered by gender, technique and performance outcome are investigated, revealing significant variations in split times and movement execution. By monitoring the individual split times of all these athletes through normalization, a more accurate assessment of performance analysis is achieved and the influence of different movement patterns in all sections of the Speed Climbing wall is highlighted. This allows the generation of a complete overview of the distribution of time intervals and identification of potential weaknesses or strengths in the athletes’ performance. By evaluating the results of this analysis across the three main sections of the wall, a noticeable increase trend can be observed: The split times in the start section are relatively consistent, with less variability compared to the other sections. This indicates that the start technique, particularly the

Tomoa Skip, is well-established among elite athletes and executed with high efficiency. This special sequence of movements developed about 5 years ago has become indispensable in Speed Climbing and has thus established itself as the standard technique in the start section [

21]. Nevertheless, slight differences can still be recognized when going into more detail. Especially, related to physical characteristics of the athletes, the transition time in the area from Hold 3 to Hold 4 (deep squat position) can vary significantly. This result aligns with the findings of Shunko et al. [

22], who observed that somatic characteristics significantly affect both the achieved end times by speed climbing athletes as well as the technical strategies they adopt. With targeted training and proper execution [

23,

24], however, this arrangement of joint angles and positioning of the COG, originally declared as a disadvantage of this technique, can be optimized to compensate for the resulting drop in velocity.

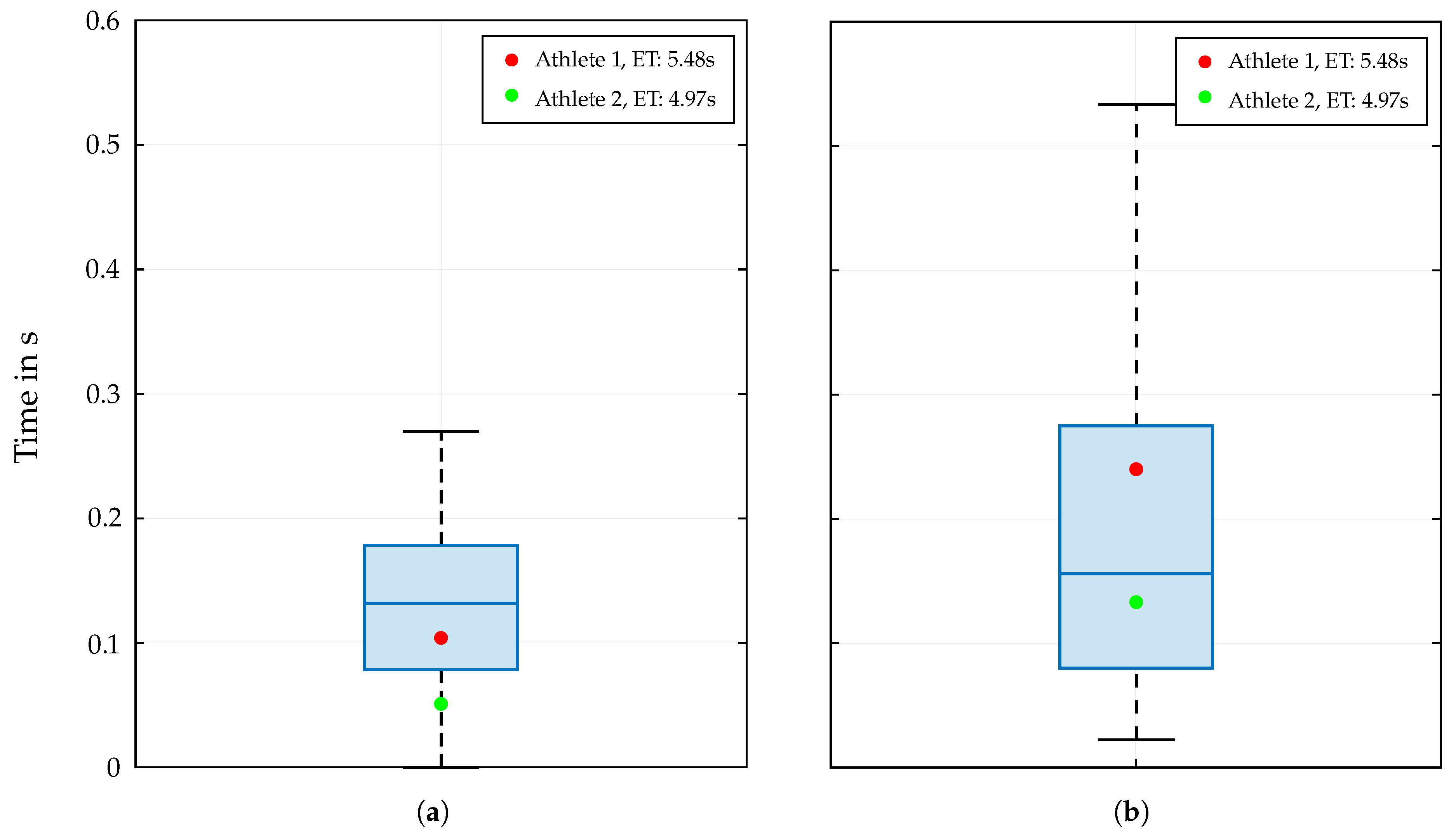

The transfer from the 5th to the 6th hold and thus the movement into the middle section reveals an interesting distribution of data points: the corresponding boxplot (

Figure 2 b) showing about 60% of the data concentrated at the median value of

, and a significant number of outliers scattered around this value. Practically, this pattern highlights Hold 6 as a critical transition point: while most athletes manage the move in a similar time, a notable minority experience much slower or faster transitions, which could appear due to slight differences in technique or execution of motion sequences. This insight can help coaches and athletes focus on this phase to reduce variability and improve overall performance.

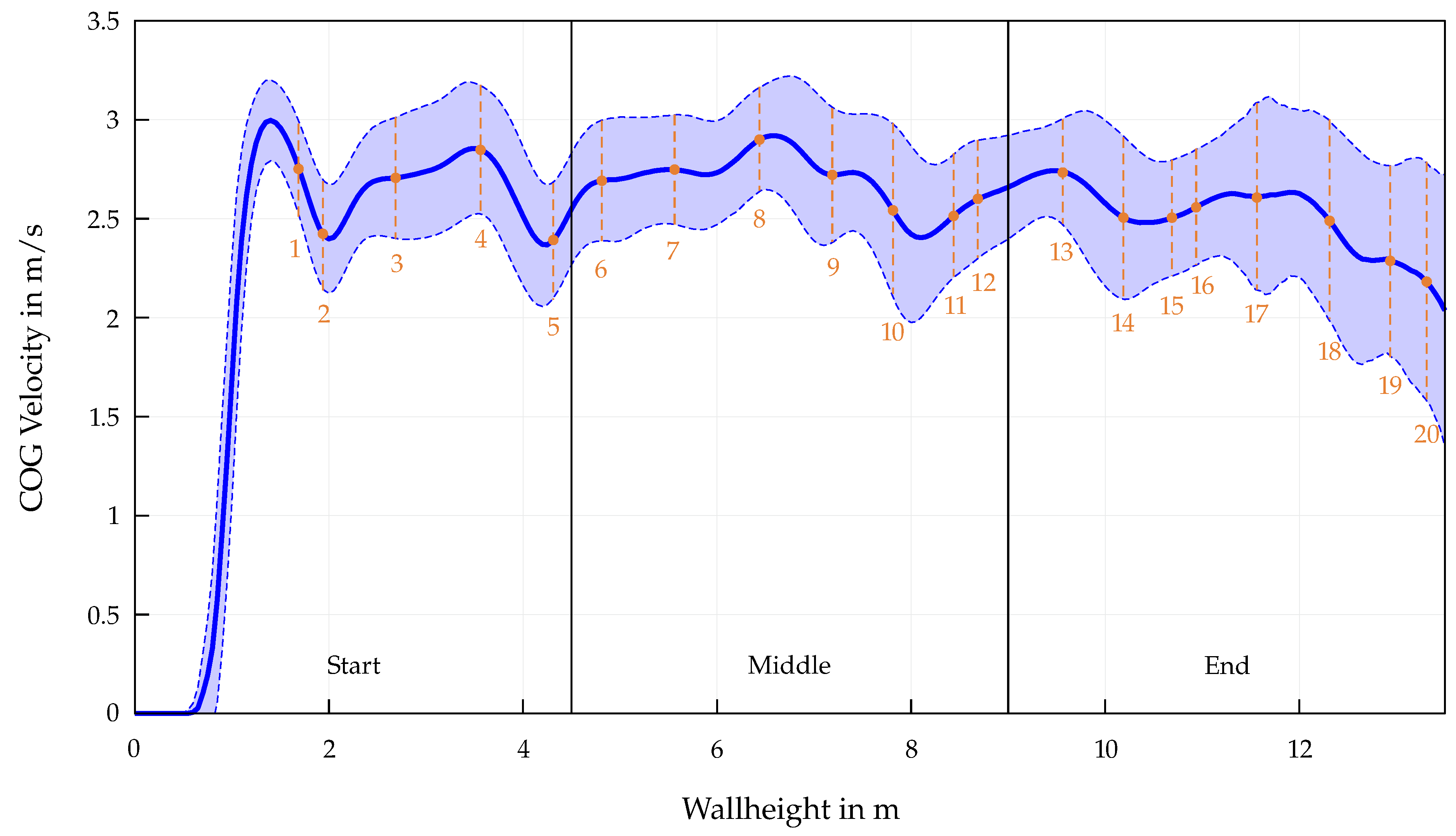

The closer the athletes get to the end of the route, the greater the distribution of the split times. While the mean values for

for the whole start (0.39 s/m) and middle section (0.38 s/m) are almost identical, the end section shows a significant increase (0.45 s/m). This is mostly attributed to the choice of movement patterns in this section, whereby the athlete has to cover large distances by skipping several holds. By shortening the path length to an almost vertical straight line of the COG, the athlete partially loses speed (see

Figure 3). The execution of these movements is reflected in split times, whereby a high degree of variability can be observed (see

Figure 2(c)). A closer look at the course of the velocity in

Figure 3 also reveals the increasing deviation from the mean value as the athletes approach the end of the route and thus the influence of different movement sequences on the overall performance. Furthermore, additional overlapping effects may explain the higher split times observed in this final section. In addition to possible signs of fatigue in the last 5 meters of the Speed Climbing wall or psychological influences triggered by intense duel with another athlete on the second lane, the specific route design makes section-wise training for movement improvements particularly difficult. Although the route map is adapted by lowering the holds of the end section, the training conditions cannot be compared to ones at competition, as it does not account the transition from the middle section.

Besides the split times for the respective hand holds, the reaction time and jump time to the end buzzer also play a crucial role in the overall performance and the results reveal interesting insights. In particular, the distribution of the reaction times over the entire dataset and the location of median (0.13 s) and maximum value (0.27 s) indicate unexpectedly high variability in the athletes’ reaction times. Overall, the range from precise, fast but more risky reactions to significantly slower responses suggests that the athletes’ reaction times are influenced by various factors, including individual training, psychological state, and competition conditions. Similar to the studies of Chen et al. [

25] and Hosseini et al. [

18], no significant correlation between the reaction time and the performance outcome could be identified.

The last time segment measured from passing the last hold to touching the end buzzer, also exhibits a high degree of variability. This is mainly attributed to the different movements sequences at the end of the route. A distinction is primarily made between two movement patterns, which are differentiated by the number of steps and positioning of the feet on the wall starting from Hold 18. While tall athletes prefer to use the previously built up momentum to jump directly to the buzzer, shorter athletes often need to take an additional step to finish the run.

In addition to this quantitative presentation of the results of the split times analysis, two athletes with different physical characteristics (see

Table 1) are separately highlighted. Thereby, their best run from the mentioned dataset are used to illustrate the influence of individual biomechanics on the performance outcome in

Figure 2 and

Figure 4. The distribution of these two data points separately for the three wall sections is particularly interesting: The most striking difference in split times can be seen in the start section. Especially when performing the Tomoa Skip, Athlete 2 with the better overall performance (4.97 s) shows a significantly lower split time than Athlete 1 (5.48 s). The poorer efficiency of Athlete 1 executing the Tomoa Skip could be explained by the fact that the athlete used a different technique in the start section (

Reza Move) in the years before achieving the mentioned personal best time. This could indicate that the athlete has not yet fully adapted to the new technique, resulting in a less efficient execution and thus a longer split time. In the middle and end sections, the two athletes show more similar results, with Athlete 2 largely performing at the respective medians of the distributed data points per hold section, while Athlete 1 fluctuates around these values without leaving the interquartile range (IQR).

The individual results for reaction and jump time show a significant correlation with the achieved end time. While physical constitution has no direct influence on the reaction time, parameters such as height and arm span play a crucial role in the choice of the final movements and thus on the jump time.

In general, the results of the split times analysis highlight the importance of individual biomechanics and techniques in Speed Climbing. The evaluation of certain areas of the wall reveals advantages and disadvantages of the movement patterns used, especially for Athlete 1 but also for Athlete 2, which can be used to optimize training methods and thus the performance in future competitions.

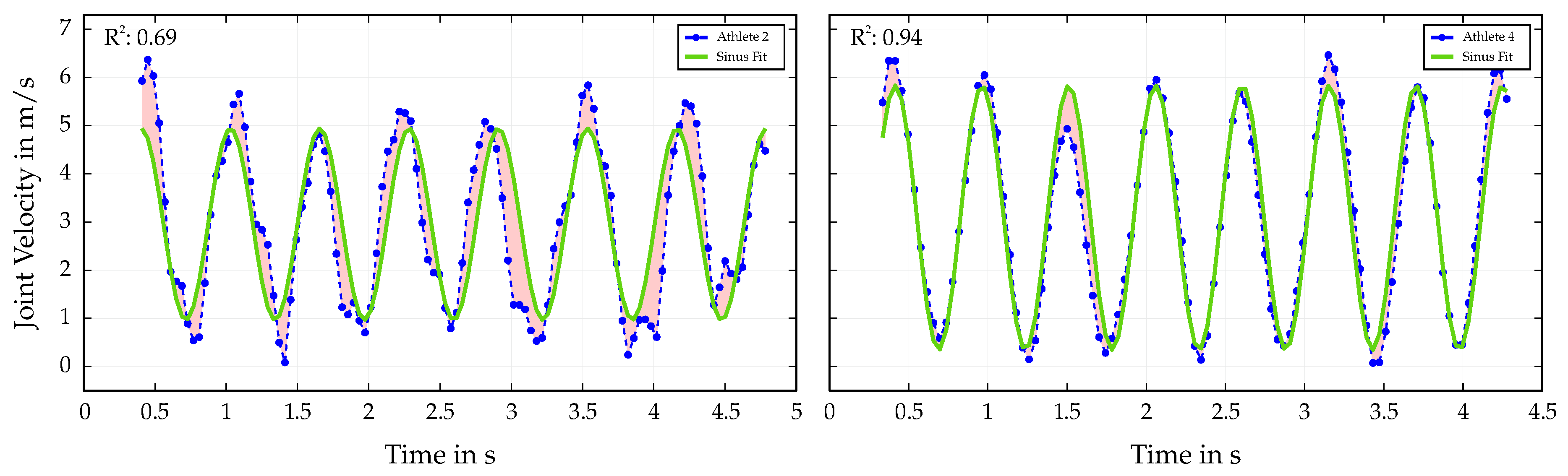

The second part of the presented results focuses on the analysis of the limb frequencies of hands and feet in Speed Climbing and their influence on an athlete’s success. As in other sport disciplines, the coordination of limb movements are crucial for achieving optimal performance in Speed Climbing. A sinusoidal model is fitted to the velocity data of hands and feet, allowing a detailed analysis of the athletes’ movement process. Thereby, the best possible fit of the model to the data with the largest coefficient of determination R

2 is selected for each signal and the deviation is first considered objectively by the residuals (see

Figure 5). The results show that the fitted model describes the joint velocity data of the athletes’ limbs well, with high R

2 values indicating a good fit. However, significant differences in the execution of the movements can be observed, especially between athletes with different performance outcomes. The athlete with the better performance shows a more consistent and stable velocity profile, following the estimated mono-frequent sinus more closely. This visual analysis of the deviations of the velocity signal from the fitted model in

Figure 5 also highlights possible weaknesses in the athletes’ movement patterns in different section of the Speed Climbing wall, which can be used by trainers and athletes to optimize training methods and improve performance. However, it should also be noted that the distribution of the data points for R

2 concentrates in a certain direction toward higher values and lower end times. It turns out that for athletes with end times ≤ 6 s, this parameter may no longer be an indicator for the performance. While top athletes have almost perfected common movement patterns in different sections of the wall through intense training, the results of slower athletes show significant deviations from harmonious movements of the limbs. Accordingly, the inclusion of multi-frequent sinusoidal models could be considered in future work to better capture the complexity of the movement patterns in Speed Climbing.

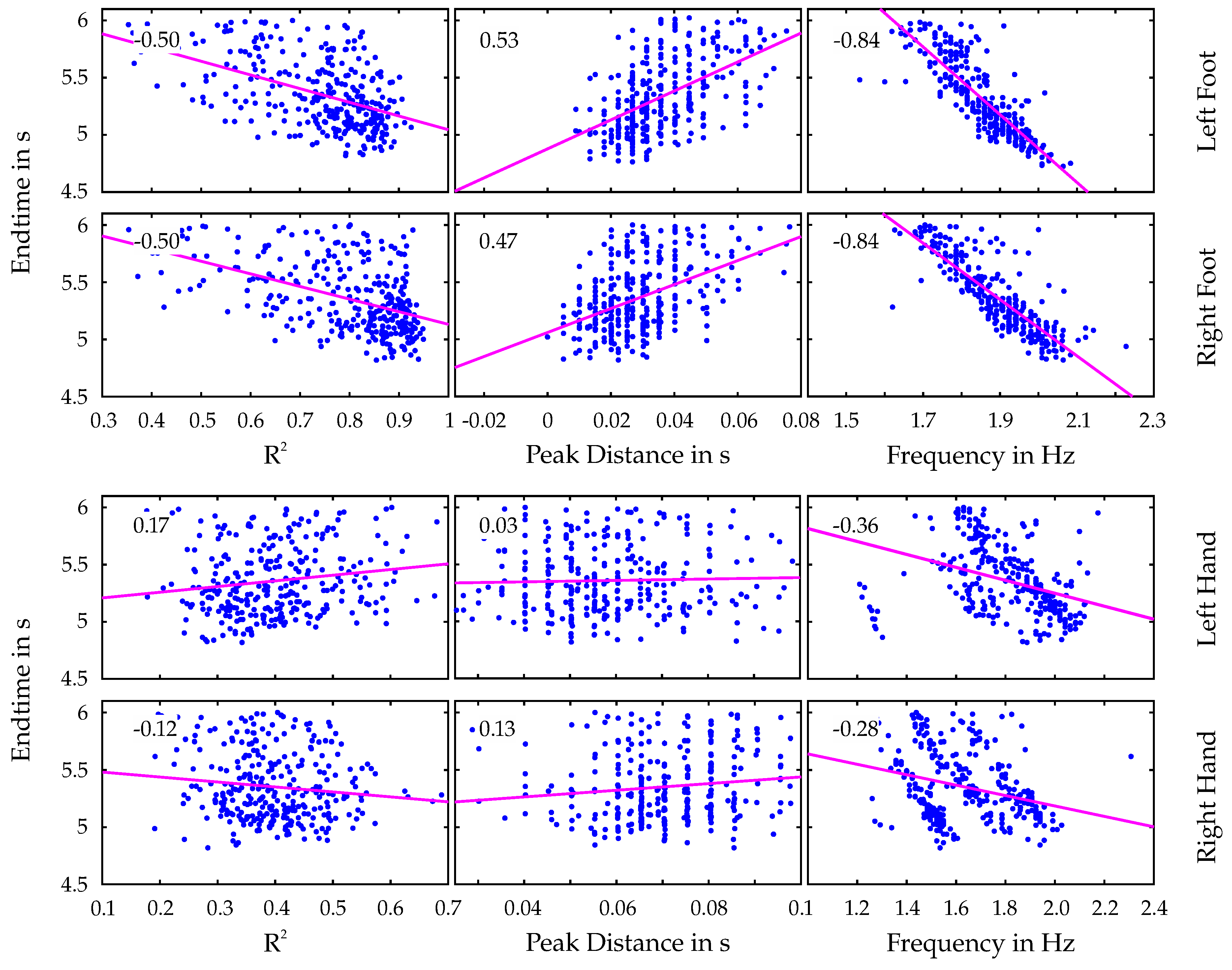

Going into more detail about movement sequences and the dependence on coordination and synchronicity of the limbs, a correlation analysis is performed to investigate the relationship between the athletes’ performance and various parameters. In addition to the already mentioned coefficient of determination R

2, the mean peak distance of the fitted sinusoidal model as well as the dominant frequency of the velocity data of each limb are considered. Initially, large differences between the correlation results for hands and feet separately are observed in

Figure 6. While clear and comprehensive correlations can be identified for the feet data, the correlations of all parameters with the hands data are significantly lower. The discrepancy can be attributed to two factors. First, the accuracy of key point detection for hands is generally lower than for feet, especially in the cases of superimposition with the torso. As their covered position cannot be determined precisely in these cases, the location of the key points and thus the velocity data are interpolated based on proper points detected on neighboring frames, initially by the human pose detector and subsequently in the postprocessing. Second and more importantly, the movement of the hands, unlike those of the feet, lack a regular pattern. While the feet primarily serve the function of pushing off the wall and stabilizing the body, the hands are repetitively used to pull the athletes’ body towards holds to generate the necessary momentum. The associated increase in contact time with the holds lead to a disharmonious movement pattern. Since the periodicity of the velocity data is not as pronounced as for the feet, the fitting of the sinusoidal model fails, resulting in low R

2 values and thus a less reliable analysis of the hands’ movement patterns. Accordingly, only the results of the feet data were subsequently taken into account and examined further in more detail.

The correlations of the mentioned parameters with the end time for the lower limbs clearly confirm the second hypothesis of this study, which states that the coordination of individual limb movements correlate with competitive success in Speed Climbing. The results show that better-performing athletes exhibit higher R

2 values, smaller peak distances and higher frequencies in their limb movements. The high correlation between end time and R

2 values indicates that athletes who can maintain a consistent and coordinated movement pattern are more likely to achieve better performance outcomes. The obtained results are consistent with those of Cordier et al. [

26], who describes the measured parameters as an entropy index.

Figure 5 (right) demonstrates how exceptionally well the data points of a successful athlete adapt to a single-frequency sine wave resulting in a high R

2 value close to 1. Smallest deviations from a regular movement due to technical errors in the execution of the movement sequences are also reflected in the rise of peak distances. Despite its correlation with R

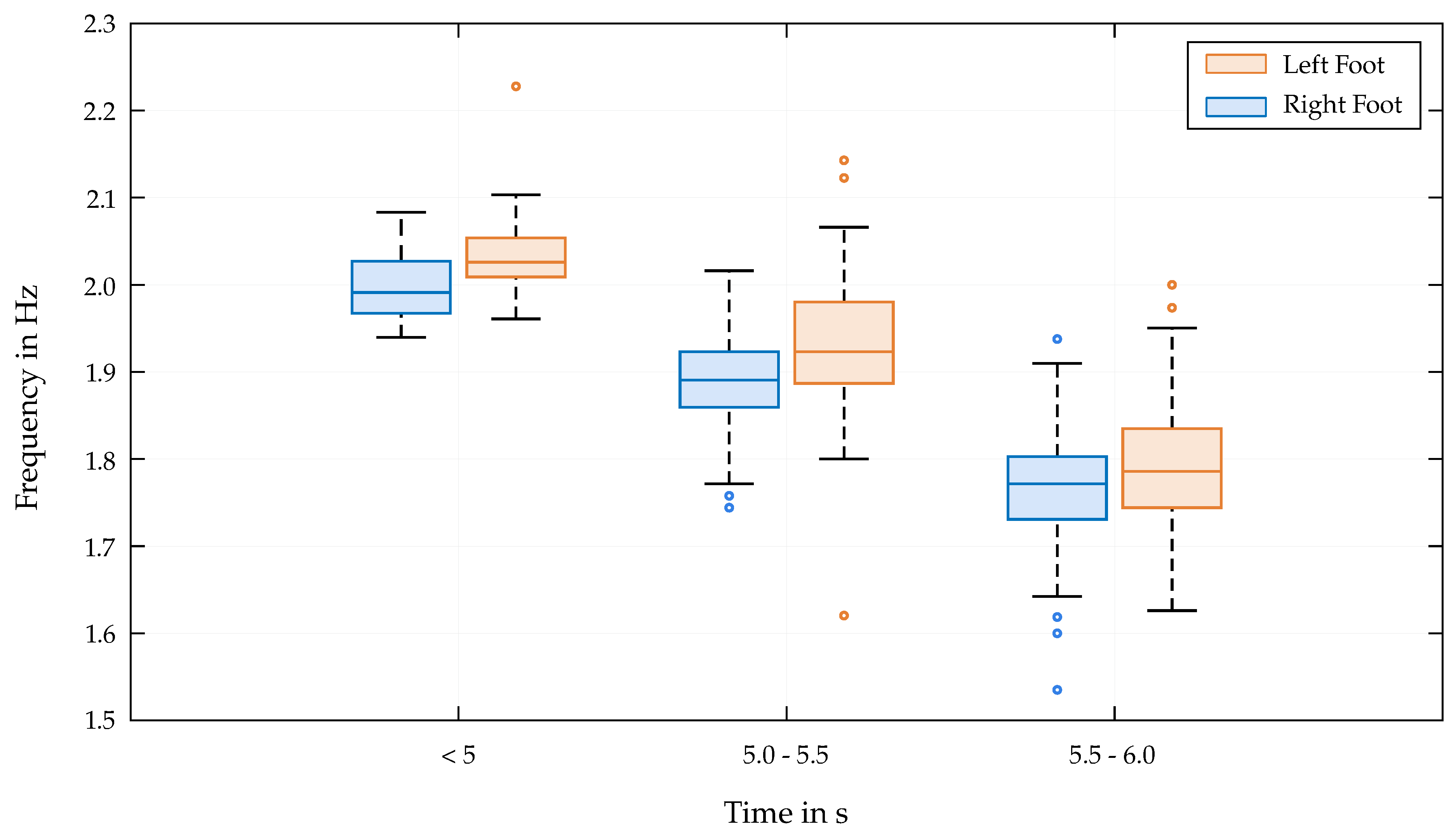

2 (-0.70 for left foot, -0.77 for right foot), the consideration of the peak distances is important, as it provides additional insights and helps to identify potential weaknesses in the athletes’ movement patterns. While a significant correlation between lower end times and higher frequencies is not surprising, the distribution of the frequency over the entire time range is interesting.

Figure 7 shows the scatter of frequencies is greater for athletes with poorer performances. This indicates that an increase in frequency could affect the correct execution of the movements, leading to less efficient patterns or errors. This distribution is substantially lower for the group of athletes achieving remarkable end times below 5 seconds.

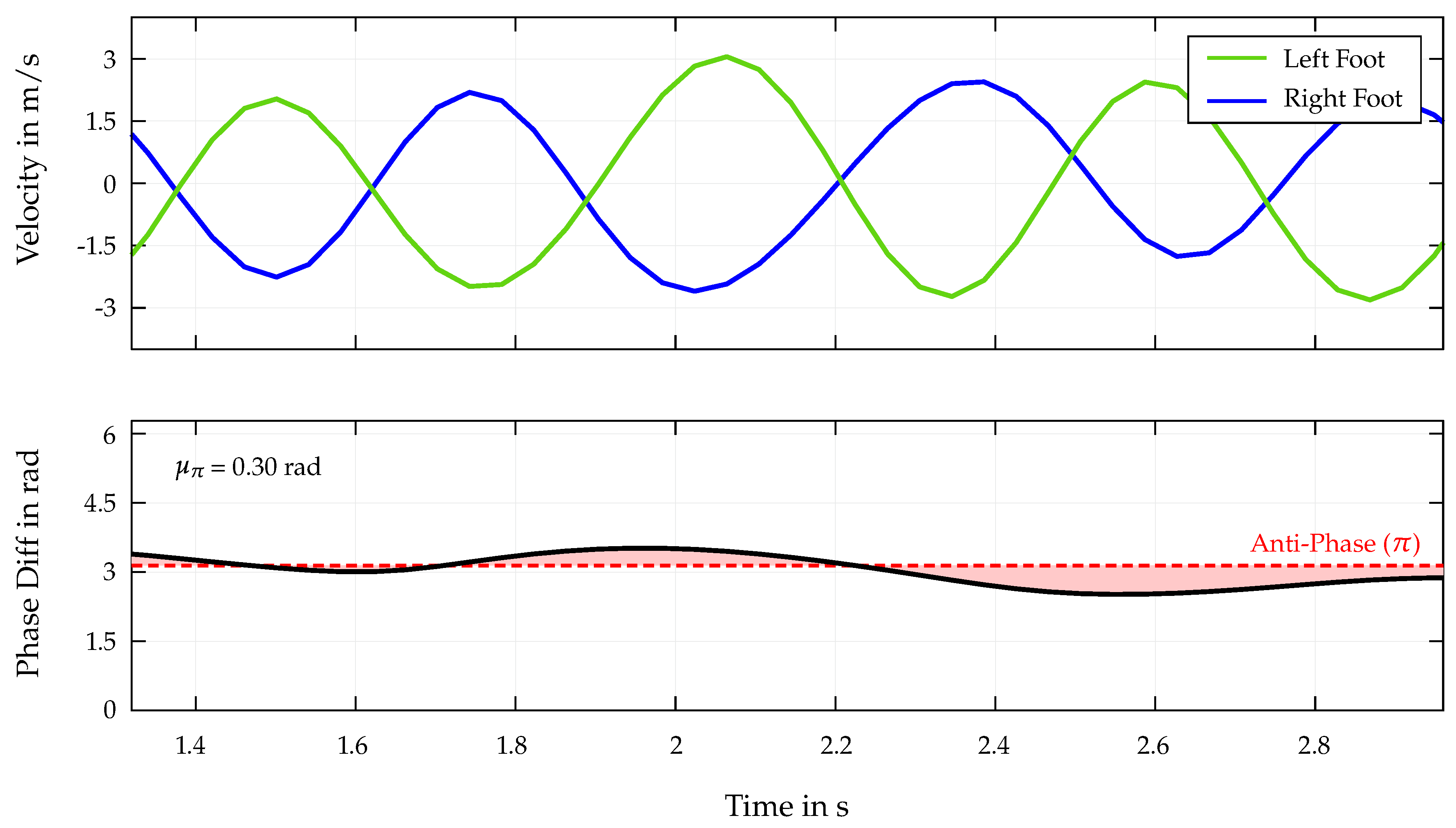

The similarly high correlations for both left and right foot suggest that, in addition to the coordination of the individual limbs separately, a synchronized movement pattern of both feet together is also crucial for achieving optimal performance in Speed Climbing. Regarding

Figure 8, both visually when looking at the two velocity curves and in calculated phase differences and

value, the athlete moves the two limbs in a almost perfect coordinated and opposing manner. The mean absolute deviation from

is calculated to be 0.3, indicating a high degree of anti-synchronicity between the two limbs during the analyzed movement. When looking at the correlation of these values with the end times for the entire dataset, a relatively low value of 0.24 is obtained compared to the other parameters of the correlation matrix in

Figure 6. This indicates that despite existing connecting with successful runs, the athletes in the limited data set for end times < 6 s have generally achieved a high level of coordination and anti-synchronicity between the two feet. Due to the results of the correlation matrix for the upper limbs and the proof of a non-regular movement of the hands in Speed Climbing, an analysis of the anti-synchronized movement of the hands and a synchronous motion of opposite limbs (left hand - right foot, right hand - left foot) is not performed any further.

Finally, it is important to mention the limitations of this study. As already described in the results section, the frame rate of the used recordings used are limited to 25 - 30 Hz. This limitation affects the accuracy of the presented data, especially for the split times, as these can only be determined with a maximum precision of 1/30 of a second. Accordingly, intensive collaboration with the IFSC is already underway via a Memorandum of Understanding, aiming to obtain direct access to official video materials recorded during competitions. This would improve the reliability of the presented parameters and enable more advanced analyses of the athletes’ performance, such as the precise determinations of contact times.