1. Introduction

When the temperature of carbon dioxide reaches 31.1 °C and the pressure reaches 7.38 MPa, it enters a supercritical state. Supercritical carbon dioxide is characterized by low viscosity and high density, which makes it an ideal heat exchange medium in thermal cycles. Ultra-high parameter carbon dioxide coal-fired power generation technology utilizes the supercritical CO2 Brayton cycle. By absorbing the chemical energy released during combustion, the system generates high-temperature, high-pressure CO2. Compared to steam cycles with the same parameters, this technology can improve power generation efficiency by more than 3% and achieve thermoelectric decoupling [

1]. However, compared to traditional steam boilers, supercritical CO2 boilers remain in the early stages of development in terms of material performance, design, and manufacturing standards. There is still insufficient data available on the corrosion resistance behavior of conventional power plant materials in supercritical CO2 environments.

The corrosion behavior of boiler materials in a supercritical CO2 environment is a critical factor influencing operational safety. On one hand, materials undergo oxidation reactions in this environment, leading to the formation of protective oxide films, on the other hand, carbonization reactions may also occur, which also can compromise the creep strength and other mechanical properties of the materials [

2]. The pressure-bearing equipment of the supercritical carbon dioxide Brayton cycle system will be subjected to prolonged exposure to high temperature and high pressure CO2. Once the oxide film is removed, it may lead to blockage, overheating, and eventual rupture of the boiler tubes. Therefore, during the development and research of the S-CO2 Brayton cycle system, the corrosion resistance of boiler materials has emerged as a critical issue requiring focused attention.

Austenitic steel is extensively utilized as a structural material for high-temperature superheaters and reheaters in conventional coal-fired power plants, owing to its superior thermal conductivity, excellent high-temperature mechanical properties and corrosion resistance [

3]. Relevant researches have been carried out on corrosion of metals in supercritical CO2 environments. Cao et al. [

4] have studied corrosion of 316SS and 310SS and Alloy 800H in supercritical CO2. Alloy 800H exhibited the best corrosion resistance compared with 310SS and 316SS. Oxide spallation occurred in 316 stainless steel. Furukawa et al. [

5] investigated the corrosion behavior of 12% chromium martensitic steel in SC-CO2 environment. The scale formed on Martensitic steels is mainly composed of the iron oxides and a complex oxide of iron and chromium. Tan et al. [

6] carried out the corrosion test of austenitic and ferritic-martensitic steels exposed to supercritical carbon dioxide. It can be found that Alloy 800H had oxidation resistance superior to AL-6XN. The FM steels were less corrosion resistant than the austenitic steels. Experimental research was conducted on 316 stainless steel in a supercritical carbon dioxide environment [

7]. It was found that 316 stainless steel simultaneously underwent oxidation and carburization. He et al. [

8] investigated corrosion behavior of an alumina forming austenitic steel exposed to supercritical carbon dioxide at 450-650 ℃ and 20 MPa. At low temperatures or under short exposure times, the oxide scale was predominantly composed of thin and continuous layers of Al₂O₃ and (Cr,Mn)₃O₄. With increasing temperature and exposure duration, the continuity of the Al₂O₃ scale was compromised, resulting in the formation of a multilayer structure. Corrosion mechanisms have been proposed to elucidate the formation of duplex oxide growth and the occurrence of carburization beneath the oxide scale [

9,

10,

11].

Austenitic stainless steel HR3C, which exhibits excellent creep strength and high resistance to steam oxidation, is extensively utilized in ultra-supercritical coal-fired power plants [

12]. This study selects austenitic stainless steel HR3C as the research subject and performs corrosion experiments in a supercritical carbon dioxide environment at temperatures ranging from 550 to 600 °C under a pressure of 25 MPa. The corrosion behavior of HR3C under these conditions is investigated to provide reference data for its potential application in advanced coal-fired power generation systems.

2. Materials and Methods

Commercial-grade austenitic stainless steel HR3C was used in the experiment. The chemical composition of HR3C, as provided by the manufacturer, is presented in

Table 1. The material was machined into specimens measuring 20 mm × 10 mm × 2 mm using a wire-cutting machine. The surfaces of the specimens were ground with SiC sandpapers of grit sizes 200#, 400#, 600#, 800#, and 1000#, followed by ultrasonic cleaning. Ultra-pure CO₂ gas (purity ≥ 99.999%) was employed in the experiment.

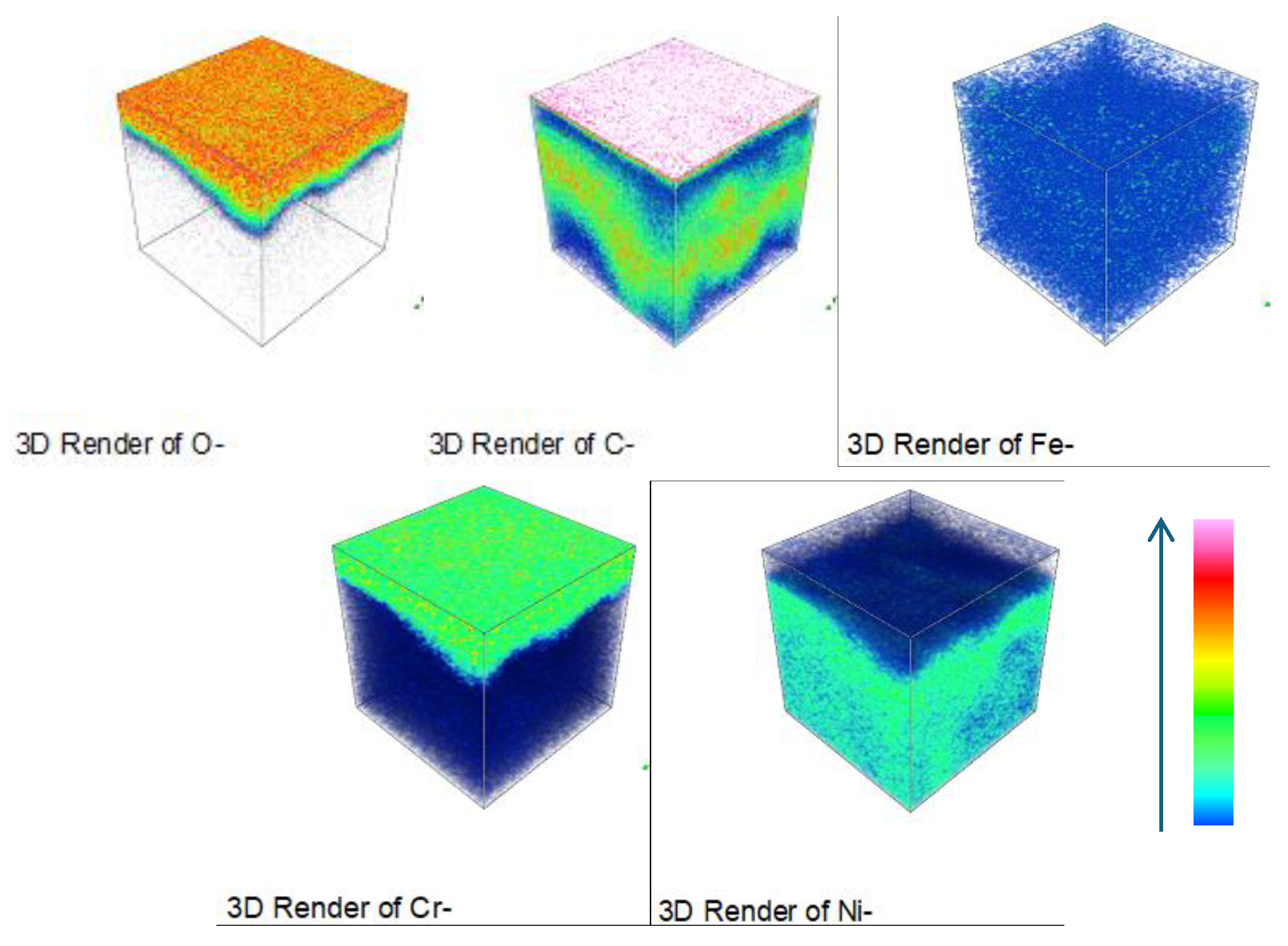

Figure 1 shows the high-temperature corrosion test system. The specimens were placed on ceramic supports. To obtain corrosion weight gain data, the mass of each specimen before and after the experiment was measured using an electronic balance with a precision of 0.01 mg. In each experimental group, three parallel samples were employed. The experiments were carried out with periodic interruptions at 200-hour intervals, and data were collected at 200 h, 400 h, 600 h, 800 h, and 1000 h, respectively. To further investigate the depth distribution of different layer structures and compositional variations, depth profiling and three-dimensional elemental imaging were conducted using secondary ion mass spectrometry (SIMS) equipped with cesium sputtering technology. The surface morphology of the samples was examined using a JEOL JSM-7200F scanning electron microscope (SEM). The elemental composition and content of the oxides were analyzed by energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS). The phase composition of the oxide film was characterized by SmartLab SE X-ray diffraction (XRD) and Thermo ESCALAB 250Xi X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). A TOF-SIMS (IONTOF V) instrument was employed to perform depth profiling and three-dimensional imaging analysis of the oxide film, thereby acquiring detailed information on the depth distribution of different layer structures and compositional variations.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Weight Gain

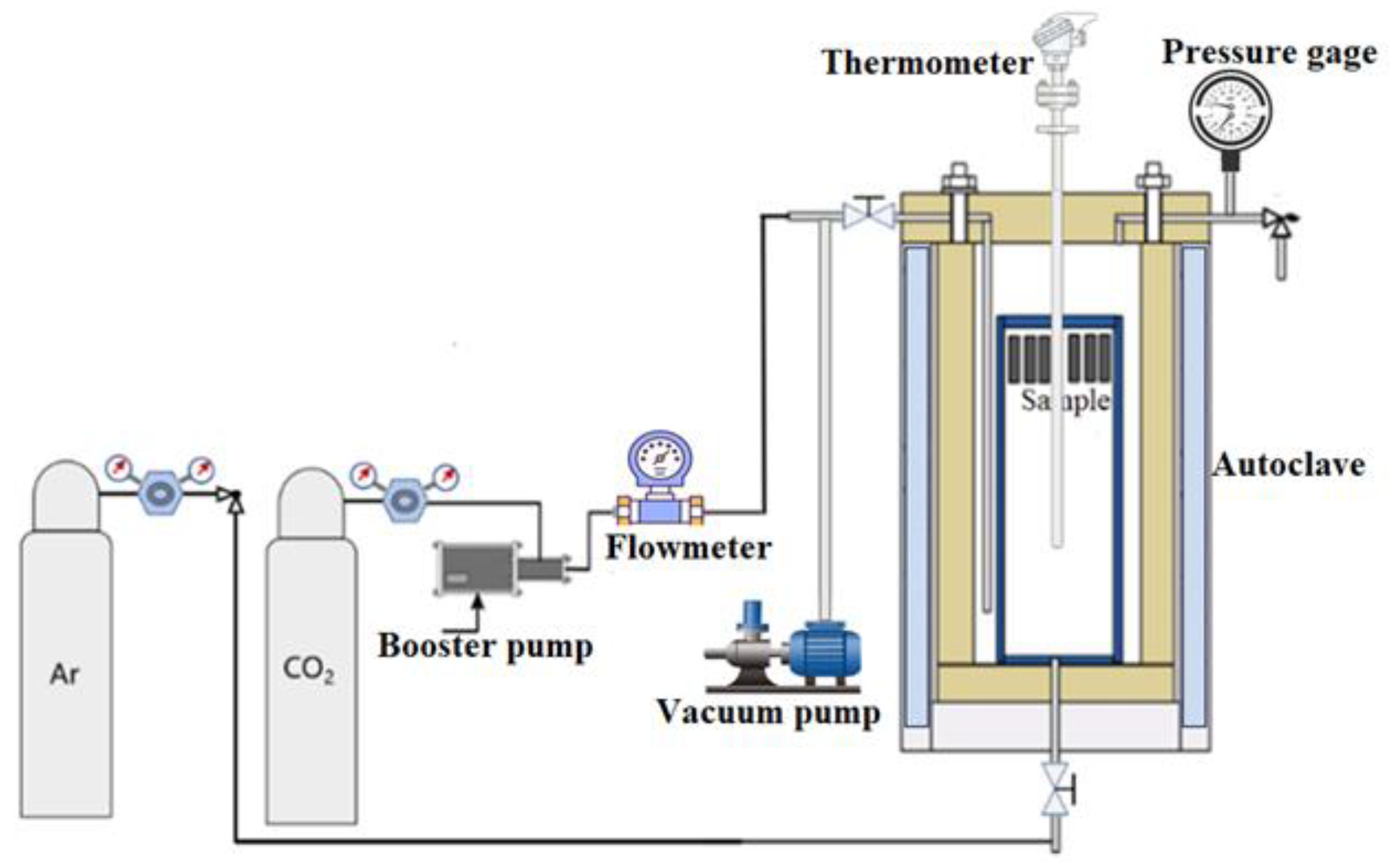

Figure 2 presents the relationship curve between the weight gain of HR3C and exposure time in supercritical CO₂ at temperatures ranging from 550 to 600 °C and a pressure of 25 MPa. The weight gain data and exposure duration were fitted according to Equation (1):

with

, weigh gain in mg/dm

2.

, the parabolic constant for oxidation in mg/dm

2·h. t, oxidation time in h. n, time exponent. As shown in

Figure 2, the time exponents at 550 °C and 600 °C are 0.65 and 0.54, respectively. The corrosion kinetics at 600 °C approximately follow a parabolic rate law, indicating that the corrosion process is governed by ion diffusion. The weight gain after 1000 h of corrosion at 550 °C and 600 °C is 1.53279 mg/dm² and 2.3122 mg/dm², respectively. With an increase in temperature, the corrosion rate of HR3C increases by a factor of 1.5. Compared to the weight gain of 9-12Cr steel exposure in supercritical carbon dioxide environments, HR3C exhibits superior corrosion resistance [

13].

3.2. Surface Morphology and Elemental Composition of the Corrosion Layer

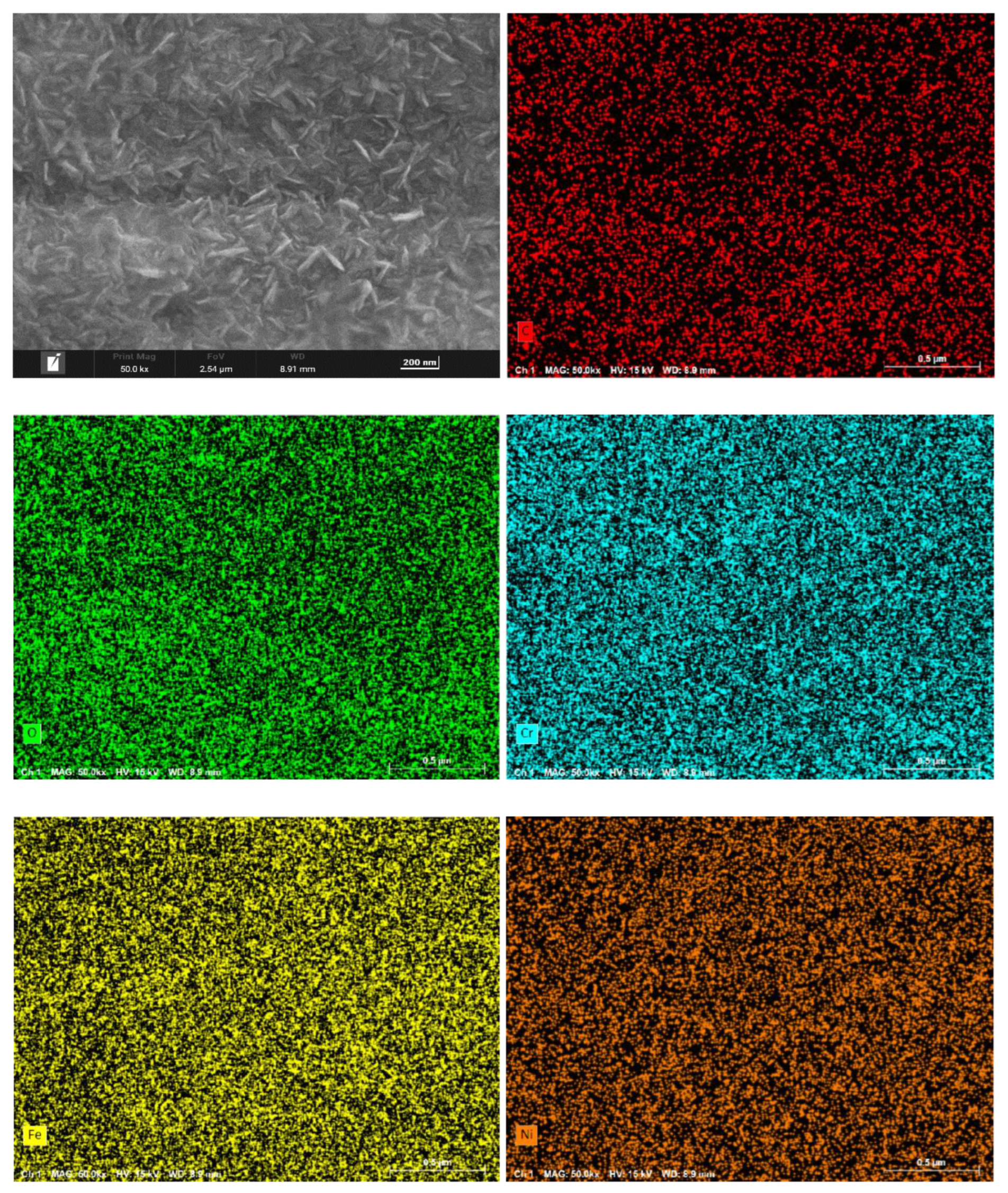

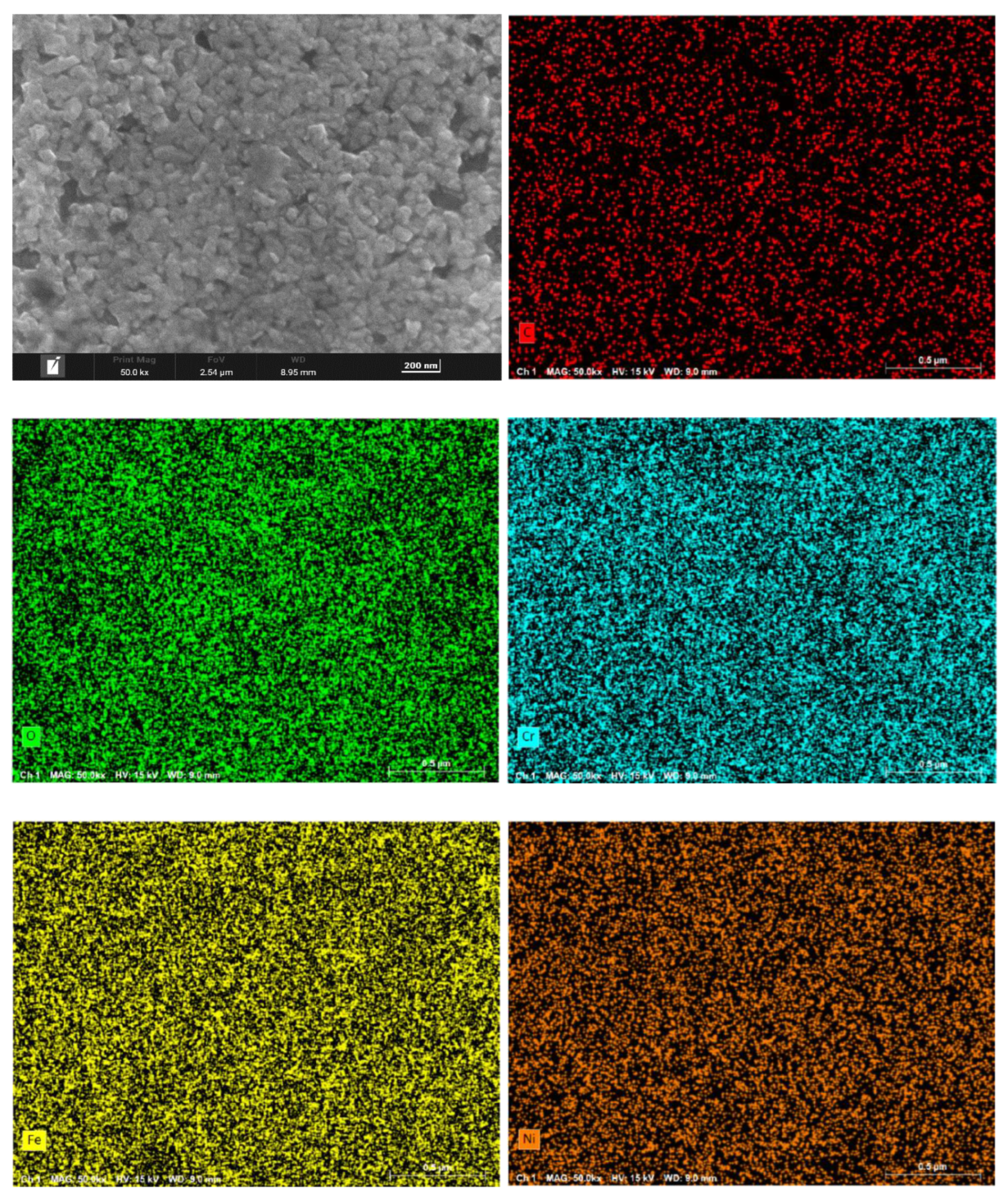

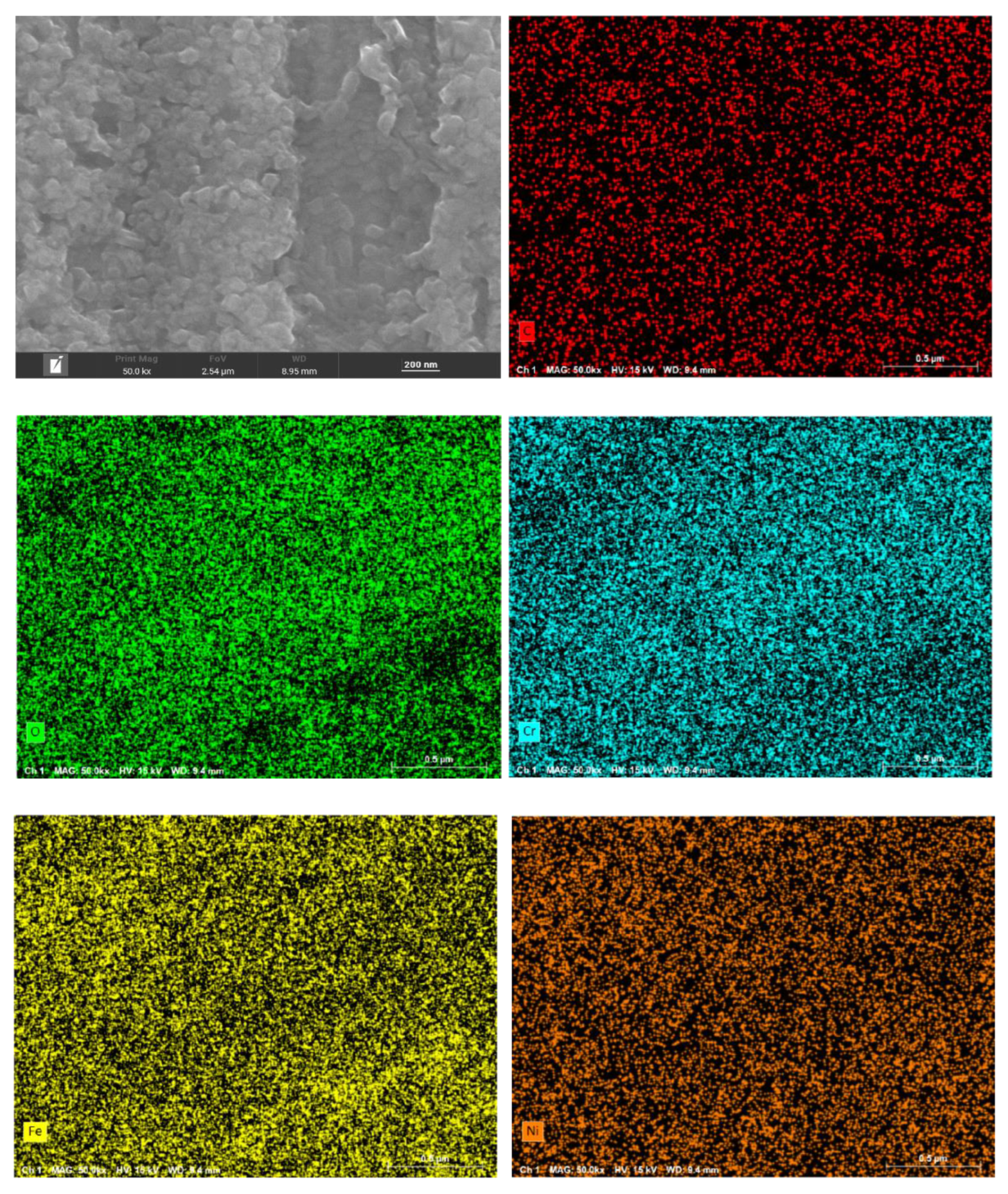

Figure 3-

Figure 6 present the surface morphology and elemental distribution of HR3C after 200 and 1000 hours of corrosion in supercritical CO₂ at 550- 600 °C. As indicated by the surface morphology, a fine and uniformly distributed layer of flaky oxides is observed on the sample surface after 200 and 1000 hours at 550 °C. At 600 °C, nano-sized granular oxides are formed on the surface, with an increase in particle size observed as the temperature rises. The oxide film remains compact overall, with no signs of spallation.

Table 2 shows the primary compositional elements of the surface corrosion layer at 550-600 ℃ for different time. EDS scanning results reveal that the surface oxides primarily consist of C, O, Cr, Fe, and Ni. Surface scanning results further demonstrate that these five elements are uniformly distributed across the sample surface. Based on the elemental composition and content distribution, it can be inferred that carbon is enriched in the outermost layer of the oxide film.

Figure 3.

Surface morphology and element distribution of HR3C exposed to 550℃/25MPa supercritical carbon dioxide for 200 h.

Figure 3.

Surface morphology and element distribution of HR3C exposed to 550℃/25MPa supercritical carbon dioxide for 200 h.

Figure 4.

Surface morphology and element distribution of HR3C exposed to 550℃/25MPa supercritical carbon dioxide for 1000 h.

Figure 4.

Surface morphology and element distribution of HR3C exposed to 550℃/25MPa supercritical carbon dioxide for 1000 h.

Figure 5.

Surface morphology and element distribution of HR3C exposed to 600℃/25MPa supercritical carbon dioxide for 200 h.

Figure 5.

Surface morphology and element distribution of HR3C exposed to 600℃/25MPa supercritical carbon dioxide for 200 h.

Figure 6.

Surface morphology and element distribution of HR3C exposed to 600℃/25MPa supercritical carbon dioxide for 1000 h.

Figure 6.

Surface morphology and element distribution of HR3C exposed to 600℃/25MPa supercritical carbon dioxide for 1000 h.

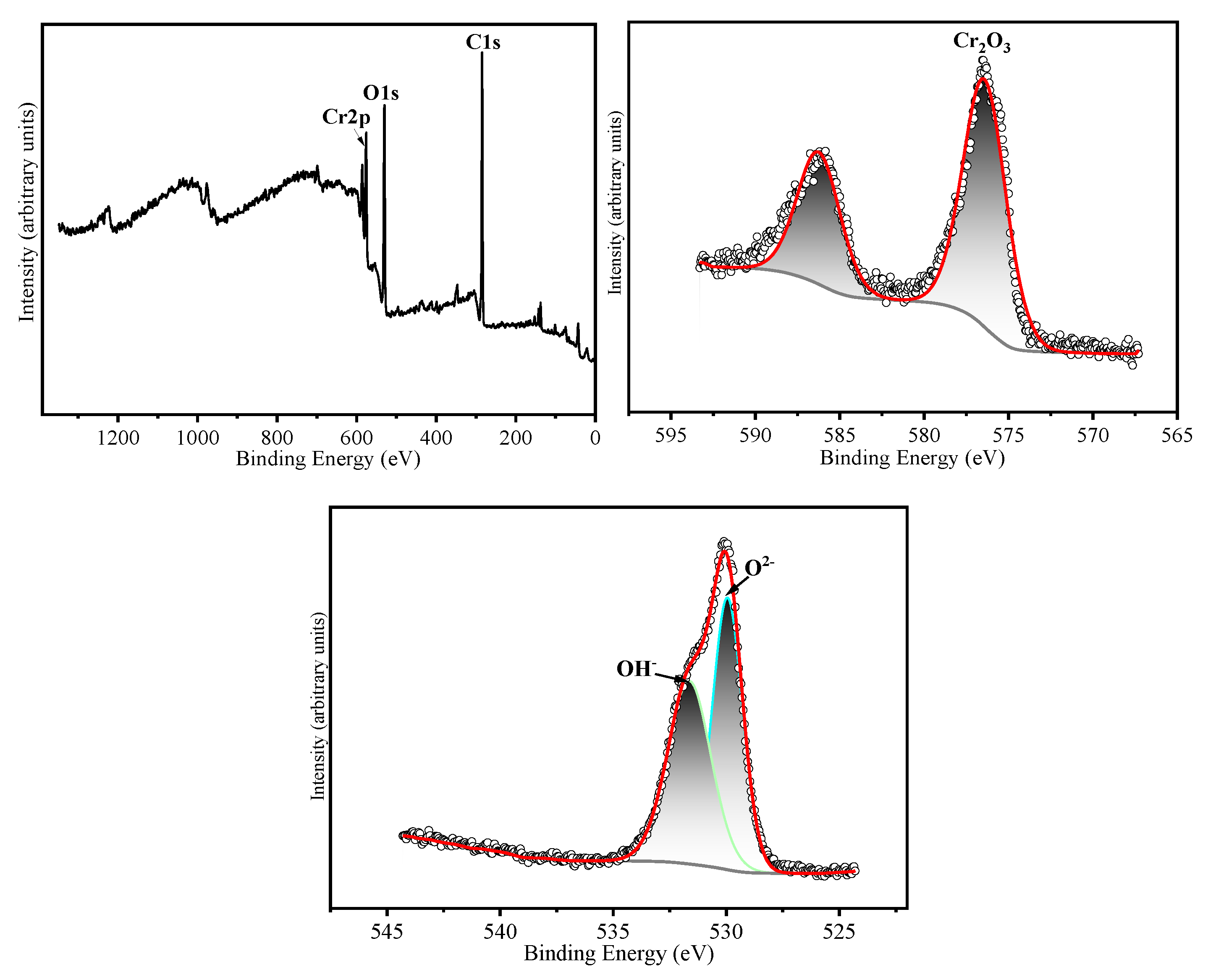

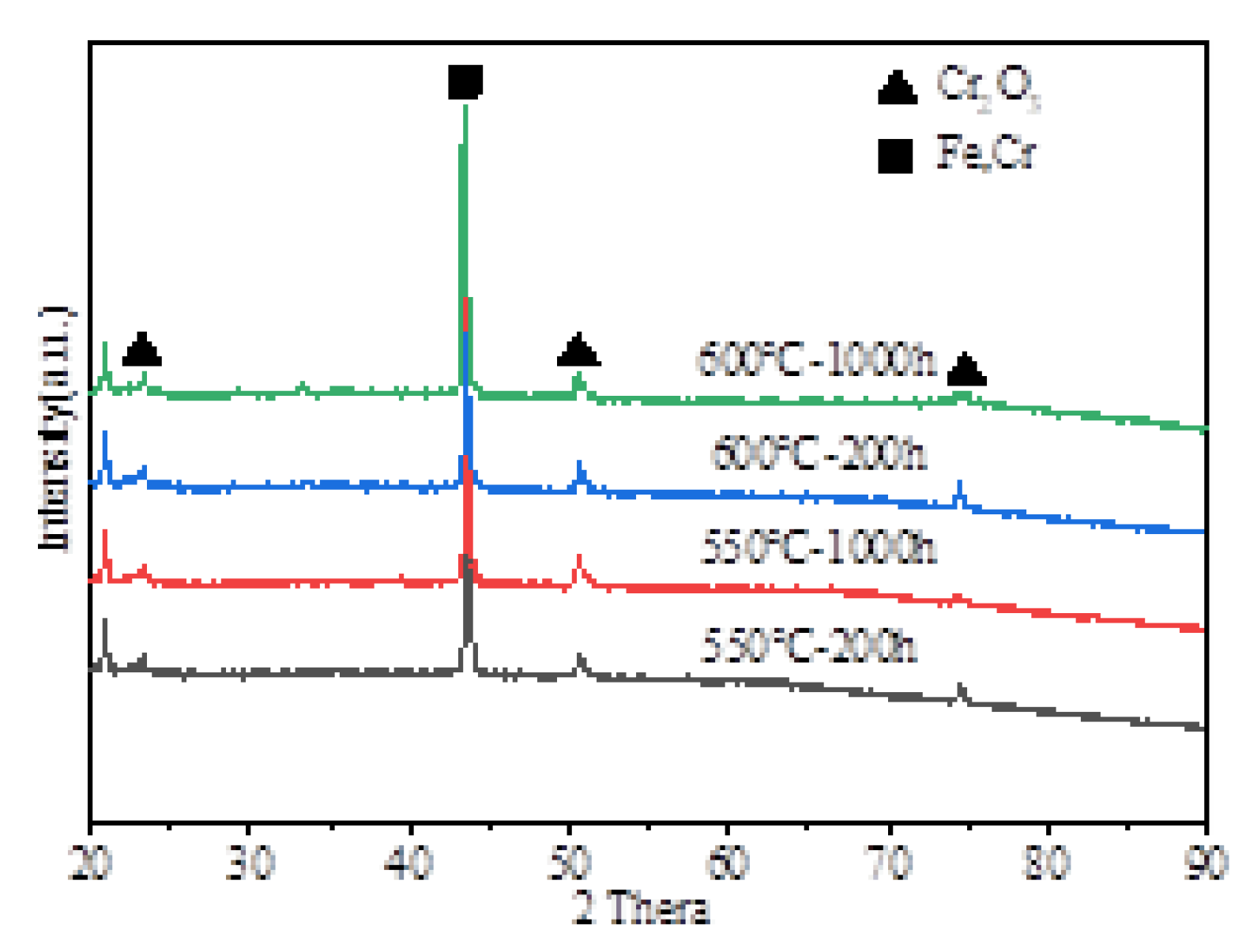

3.3. Phase Composition of the Corrosion Layer

Figure 7 presents the phase composition of the corrosion products formed on the surface of HR3C steel after oxidation for 200 and 1000 hours in a supercritical CO₂ environment at temperatures ranging from 550 to 600 °C. XRD analysis reveals that the primary oxide component is Cr₂O₃. Furthermore, the presence of substrate peaks indicates that the oxide film developed on the sample surface is relatively thin. The corrosion rate of HR3C in supercritical CO₂ is significantly reduced due to the slow ion diffusion within the Cr₂O₃ protective layer.

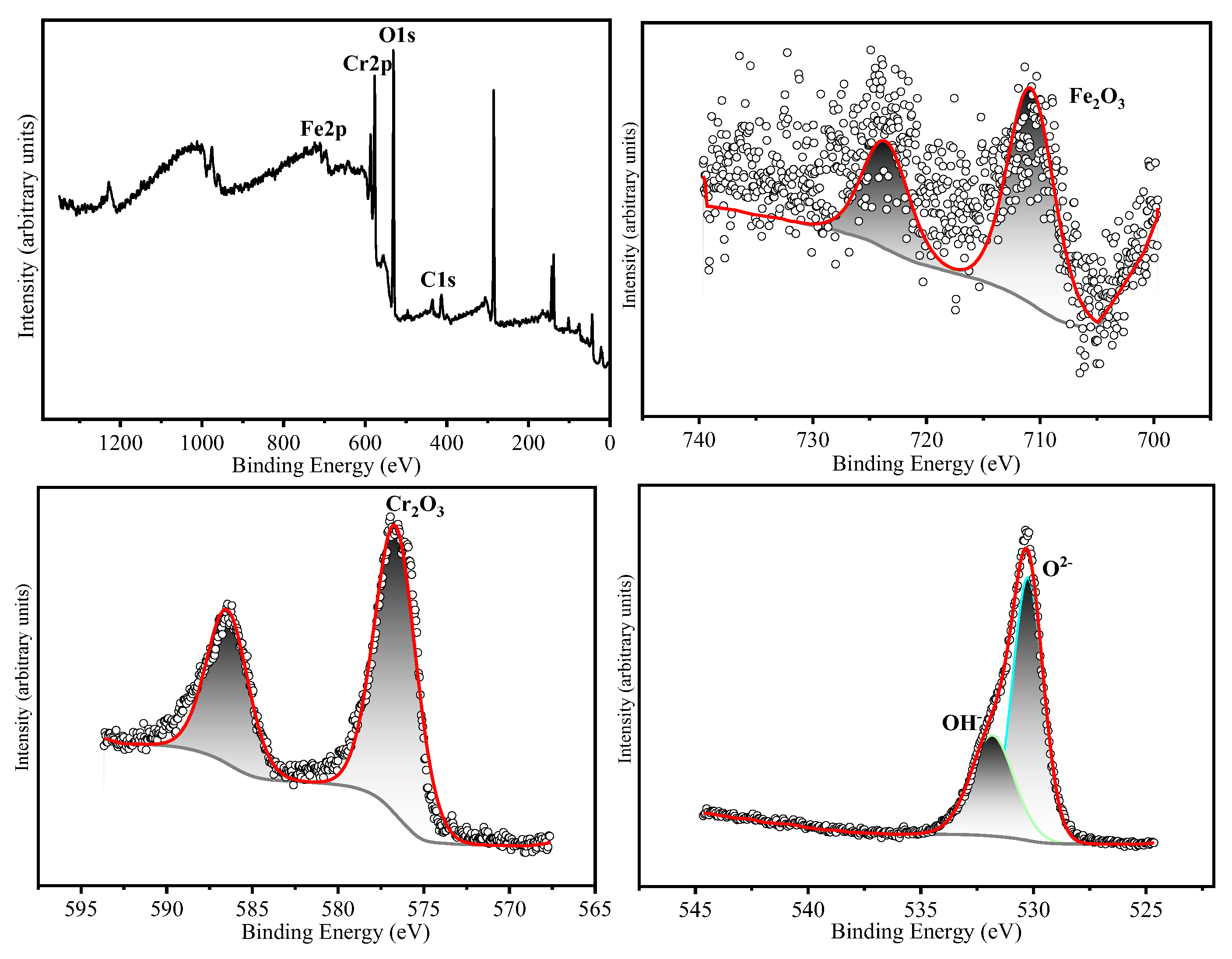

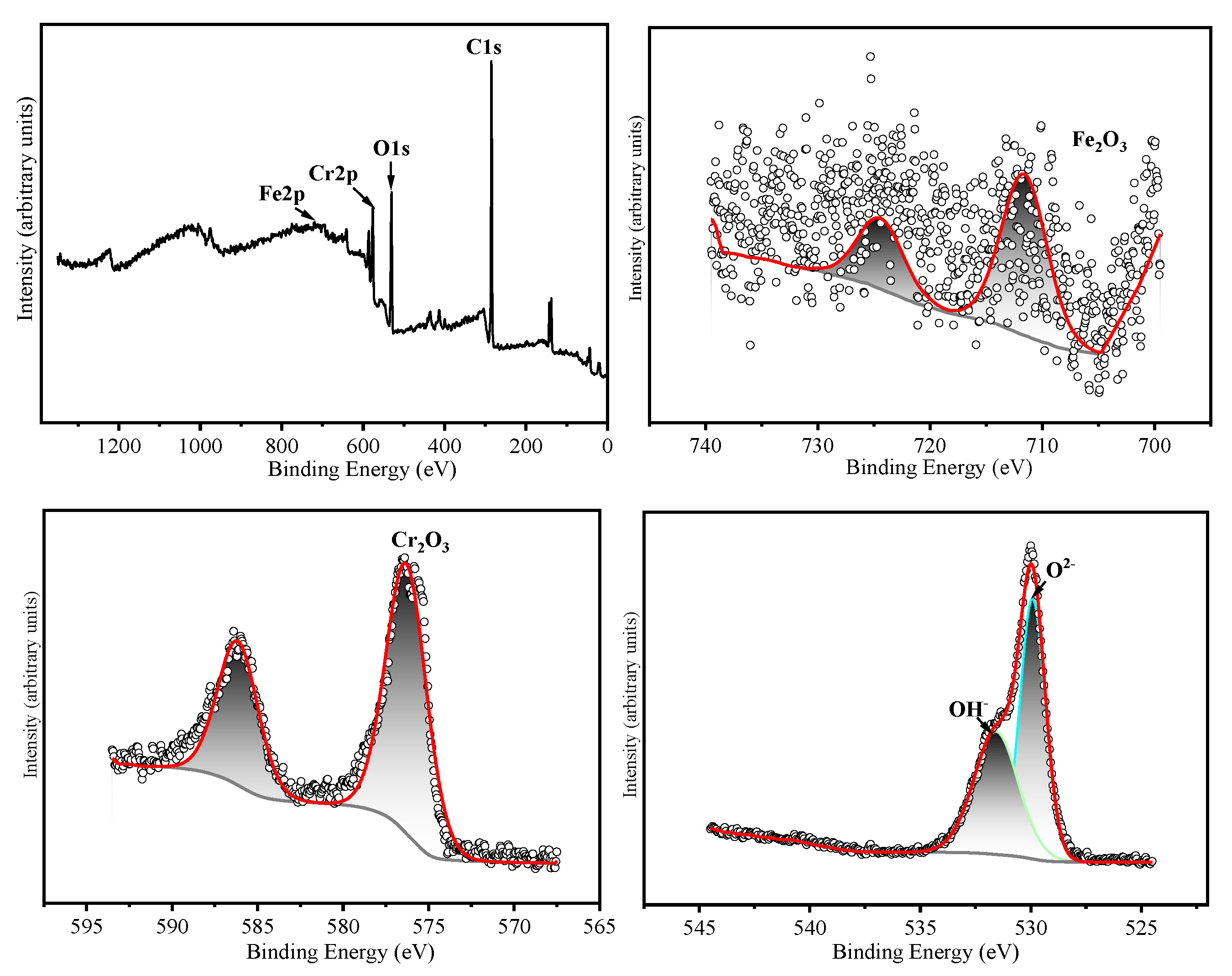

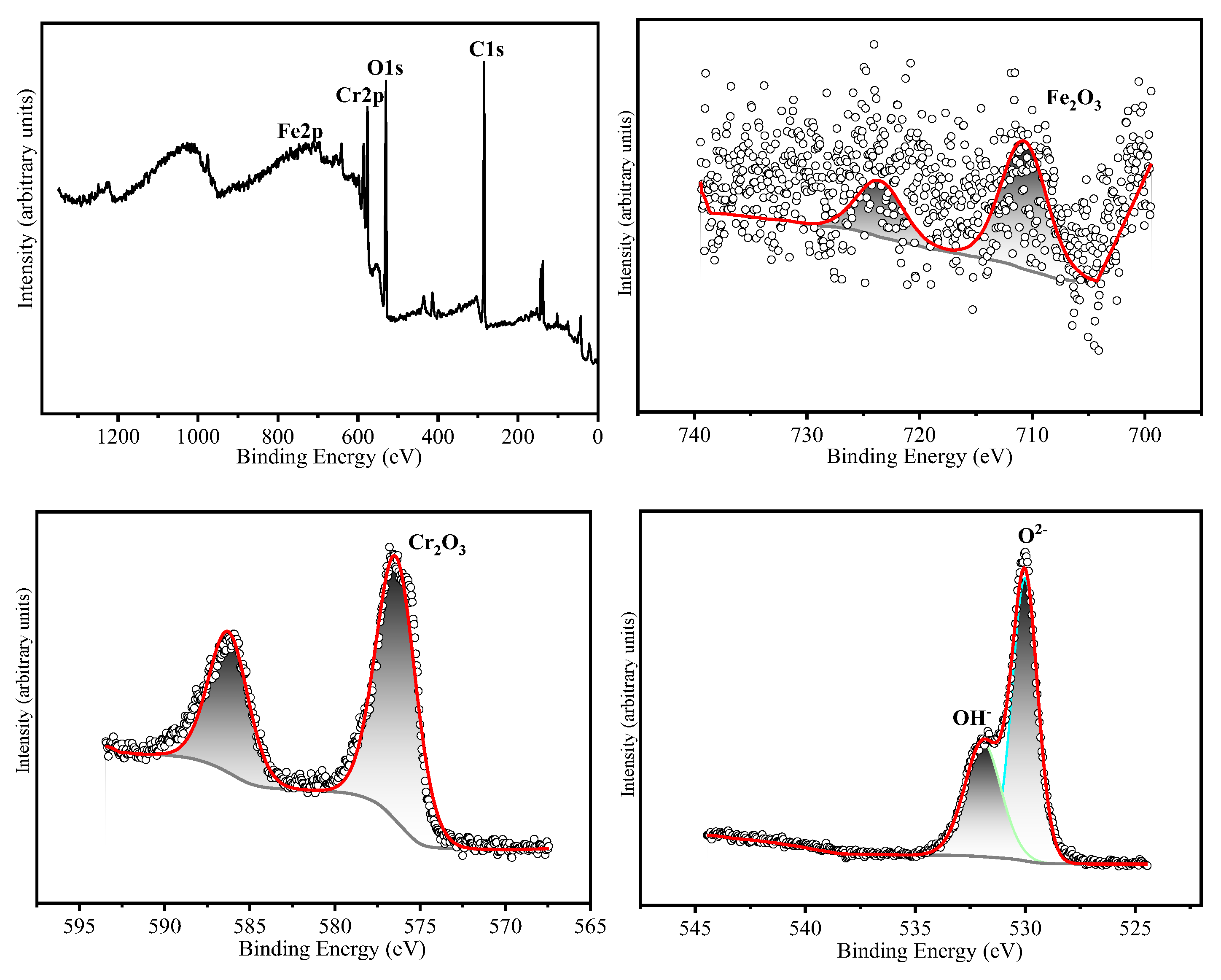

The chemical states of the constituent elements in the oxide film formed on HR3C after oxidation for 200 h and 1000 h in a supercritical CO₂ environment at 550-600 °C were analyzed using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). The corresponding results are presented in

Figure 8-

Figure 11.

Table 3 presents the binding energies corresponding to the various elements. The narrow-scan XPS spectrum of Cr 2p₃/₂ reveals that the Cr 2p₃/₂ peak is located at 576.4 ± 0.3 eV, which corresponds to the binding energy characteristic of Cr₂O₃ [

14,

15]. The Fe 2p₃/₂ peak is located at 710.5 ± 0.3 eV, which corresponds to Fe₂O₃ as the predominant oxide phase [

16]. The narrow-scan O 1s spectrum exhibits binding energies at 530.5 ± 0.3 eV and 531.3 ± 0.3 eV, which correspond to O²⁻ and OH⁻ species, respectively [

17]. Based on the XRD and XPS results, it can be inferred that after 200 hours of oxidation at 550 °C, the oxide layer is predominantly composed of Cr₂O₃. Following 1000 hours of oxidation, the oxide layer consists primarily of both Cr₂O₃ and Fe₂O₃. After oxidation for 200 and 1000 hours at 600 °C, the oxide layers contain both Cr₂O₃ and Fe₂O₃. Cox et al. [

18] calculated the diffusion rates of iron and chromium ions within the Cr₂O₃ layer, and the results indicate that the ion diffusion coefficients follow the order D

Fe > D

Ni > D

Cr. Consequently, Fe, Ni, and Cr were detected on the surface of the oxide film.

Figure 8.

XPS analyses of HR3C exposed in SC-CO2 at 550 ℃/25 MPa for 200 h. (a) XPS spectra of the surface of HR3C, (b) Fe 2p core level spectra and (c) Cr 2p core level spectra, (d) O 1s core level spectra.

Figure 8.

XPS analyses of HR3C exposed in SC-CO2 at 550 ℃/25 MPa for 200 h. (a) XPS spectra of the surface of HR3C, (b) Fe 2p core level spectra and (c) Cr 2p core level spectra, (d) O 1s core level spectra.

Figure 9.

XPS analyses of HR3C exposed in SC-CO2 at 550 ℃/25 MPa for 1000 h. (a) XPS spectra of the surface of HR3C, (b) Cr 2p core level spectra, (c) O 1s core level spectra.

Figure 9.

XPS analyses of HR3C exposed in SC-CO2 at 550 ℃/25 MPa for 1000 h. (a) XPS spectra of the surface of HR3C, (b) Cr 2p core level spectra, (c) O 1s core level spectra.

Figure 10.

XPS analyses of HR3C exposed in SC-CO2 at 600 ℃/25 MPa for 200 h. (a) XPS spectra of the surface of HR3C, (b) Fe 2p core level spectra and (c) Cr 2p core level spectra, (d) O 1s core level spectra.

Figure 10.

XPS analyses of HR3C exposed in SC-CO2 at 600 ℃/25 MPa for 200 h. (a) XPS spectra of the surface of HR3C, (b) Fe 2p core level spectra and (c) Cr 2p core level spectra, (d) O 1s core level spectra.

Figure 11.

XPS analyses of HR3C exposed in SC-CO2 at 600 ℃/25 MPa for 1000 h. (a) XPS spectra of the surface of HR3C, (b) Fe 2p core level spectra and (c) Cr 2p core level spectra, (d) O 1s core level spectra.

Figure 11.

XPS analyses of HR3C exposed in SC-CO2 at 600 ℃/25 MPa for 1000 h. (a) XPS spectra of the surface of HR3C, (b) Fe 2p core level spectra and (c) Cr 2p core level spectra, (d) O 1s core level spectra.

3.4. Corrosion Mechanism

According to the XRD and XPS results, it can be inferred that the oxide formed by HR3C in the supercritical CO₂ environment is predominantly Cr₂O₃. It is generally accepted that when the chromium content in an alloy exceeds 20%, sufficient chromium diffuses to the alloy surface to form a continuous, chromium-rich oxide layer [i].

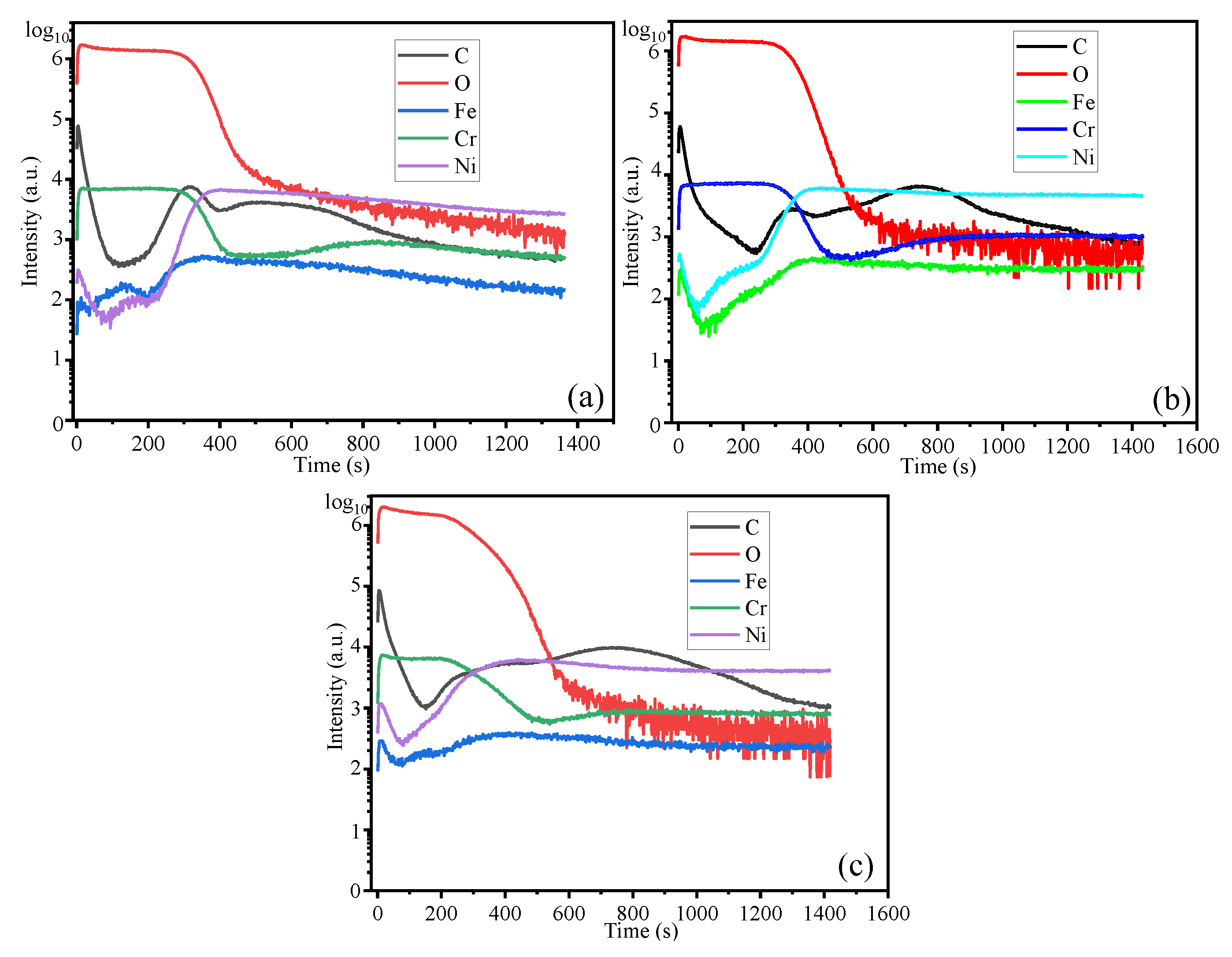

Figure 12 presents the thickness distribution of the oxide film obtained through SIMS analysis. As both temperature and exposure time increase, the oxide film thickness also increases. Along the thickness direction of the oxide film, the primary constituents are Cr and O, although Fe, Ni, and C are also present. The formation of Fe₂O₃ and Cr₂O₃ can be described by the following reactions [

1,

20,

21]:

According to the Boudouard reaction [

22], the carbon monoxide generated by reaction equations (2) and (3) may lead to the formation of elemental carbon, as illustrated in the following reaction equation:

Figure 12 illustrates the presence of elemental carbon at the outermost layer of the oxide film. This observation suggests that the generation of CO in Equation (4) predominantly occurs at the oxide film/environment interface. Reactions (2) and (3) primarily take place at the oxide film/environment interface, which contributes to the growth of the oxide film.

Figure 13-

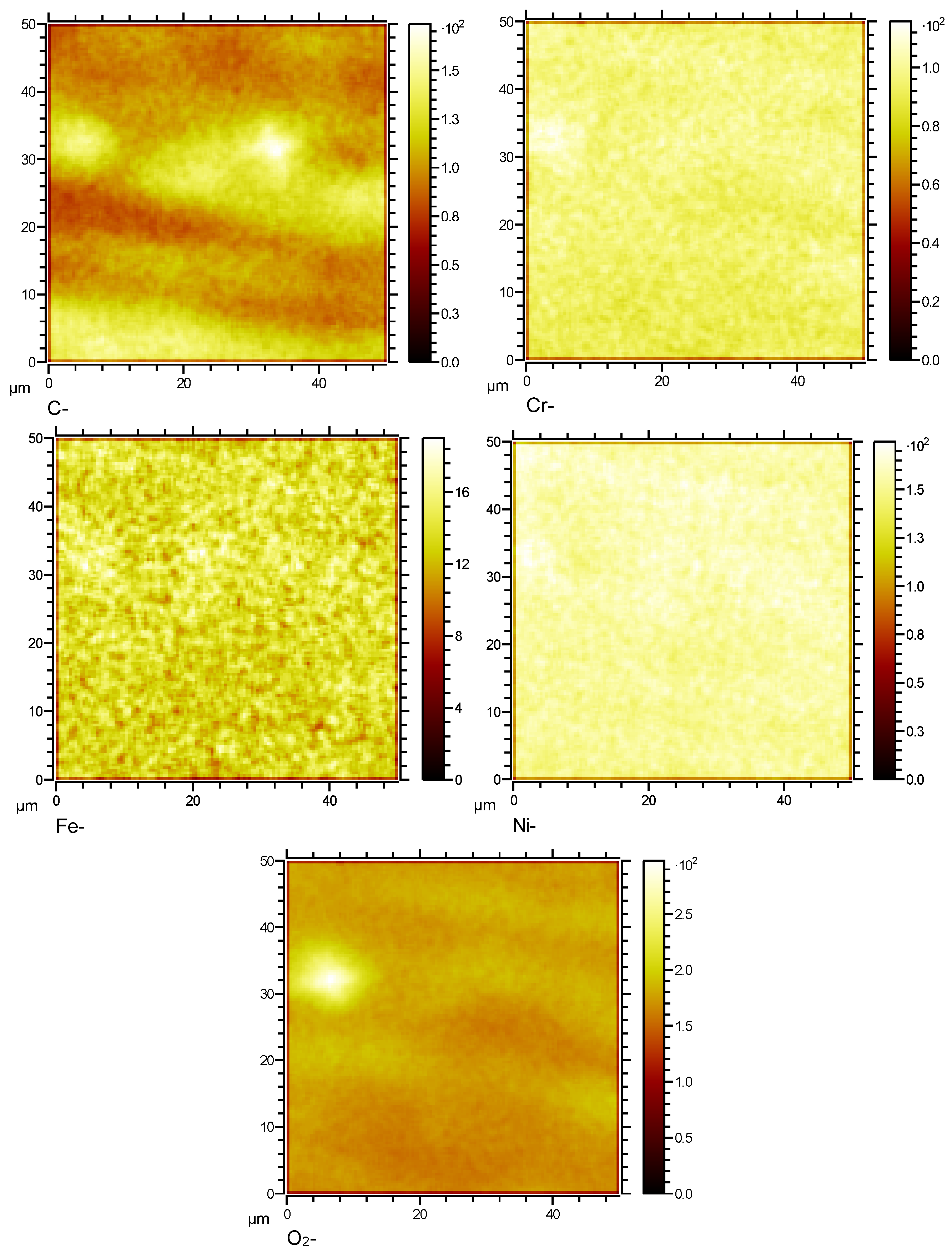

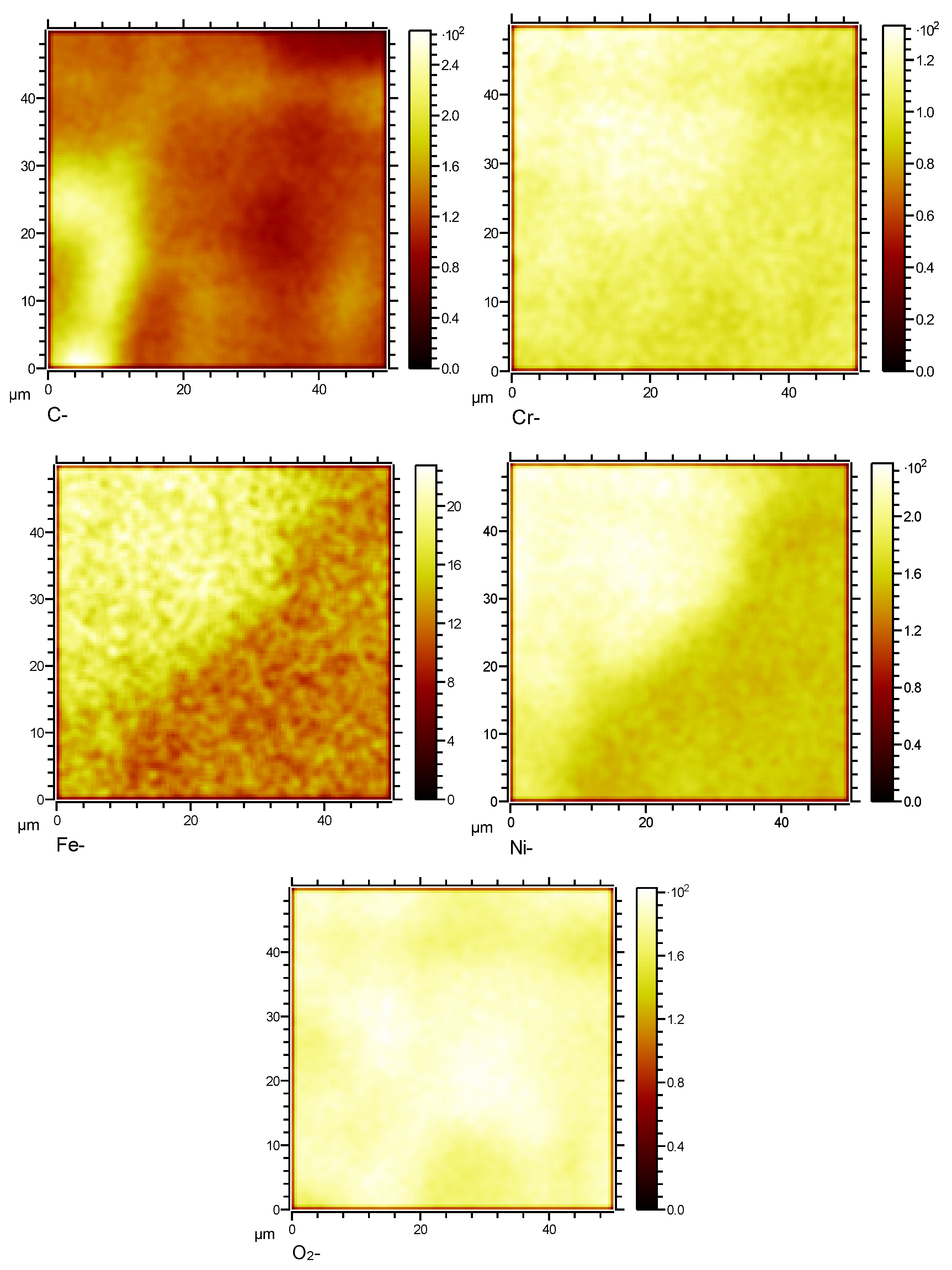

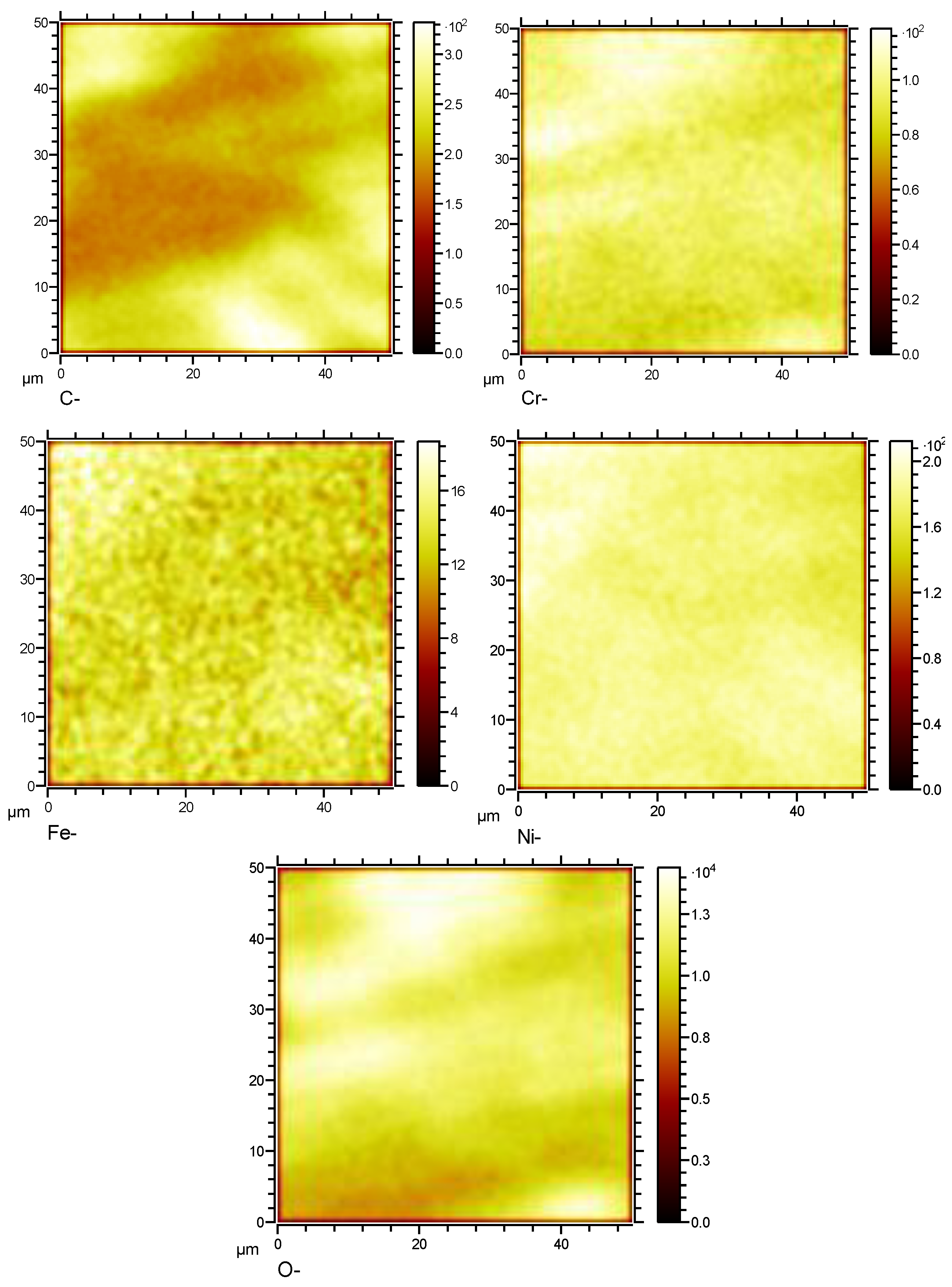

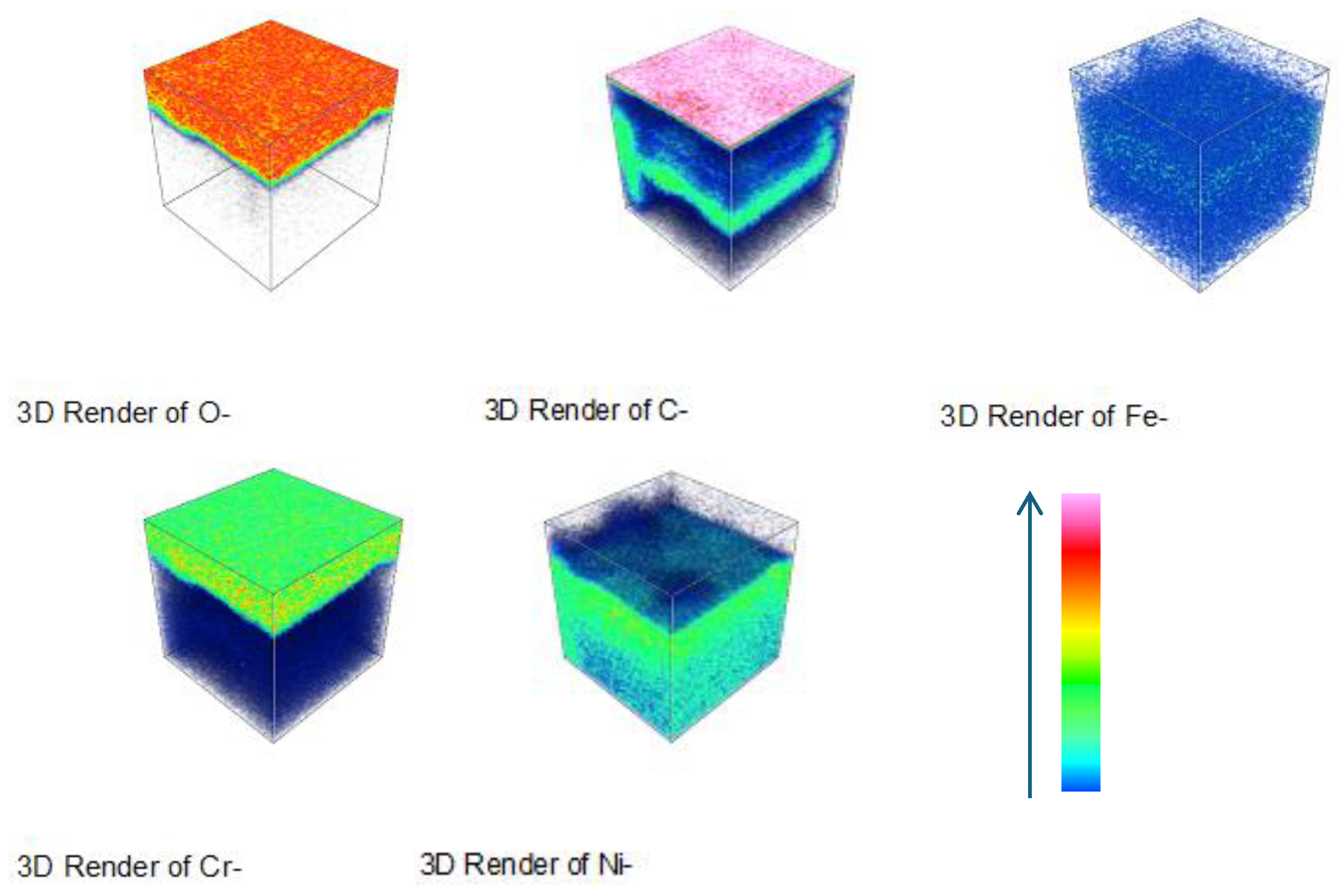

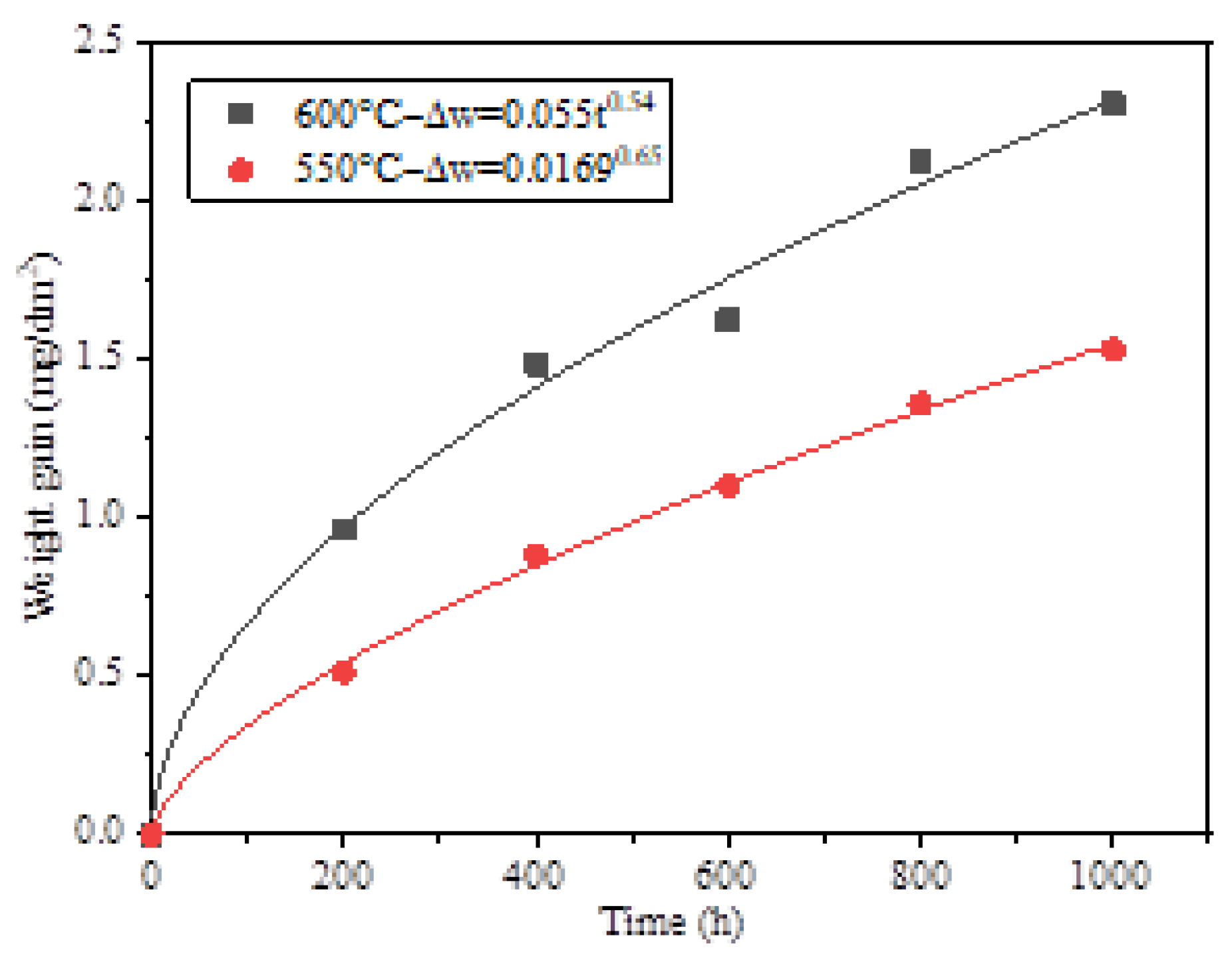

Figure 15 display the elemental distribution on the surface of the oxide film.

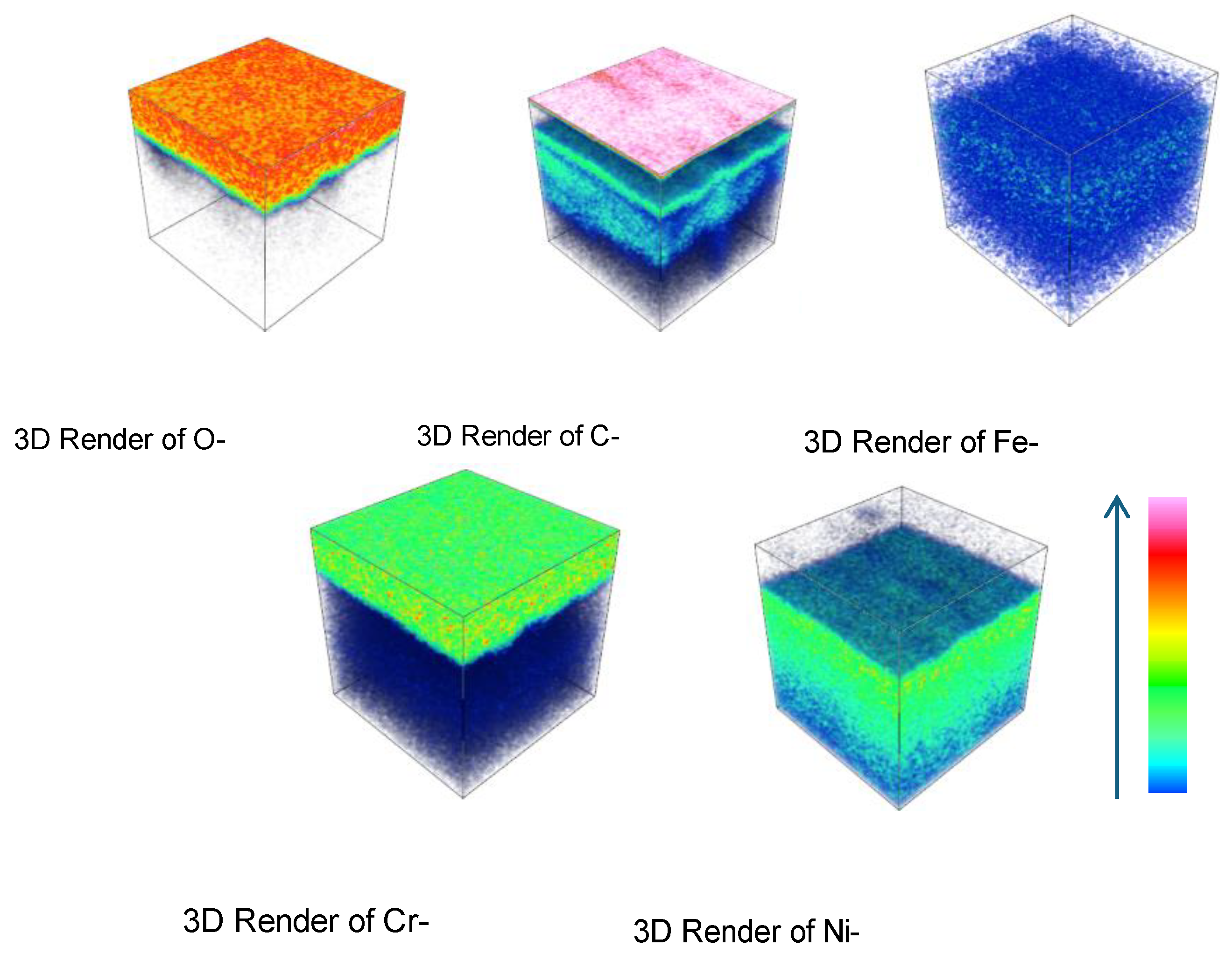

Figure 16-

Figure 18 depict the three-dimensional elemental distribution across the cross-section of HR3C after corrosion in supercritical CO₂ at 550- 600 °C for various exposure durations. Based on

Figure 13-

Figure 18, it can be observed that, in addition to its enrichment at the outermost layer of the oxide film, a minor portion of carbon diffuses to the oxide film/matrix interface, with carbon also being detected within the matrix. It was also observed that carbon was distributed throughout the thickness of the oxide film formed on 316 stainless steel [

2]. The enrichment of carbon at the oxide film/matrix interface and within the metal matrix may be associated with the inward diffusion of CO or CO₂ through the oxide film. The diffusion of carbon into the metal matrix is highly likely to result in the formation of carbides involving chromium and other alloying elements.

Figure 12.

Elemental depth profile of HR3C steel after oxidation in S-CO2 at 550-600°C for virous time. (a) 550℃-1000 h, (b) 600℃-200 h, (c) 600℃-1000 h.

Figure 12.

Elemental depth profile of HR3C steel after oxidation in S-CO2 at 550-600°C for virous time. (a) 550℃-1000 h, (b) 600℃-200 h, (c) 600℃-1000 h.

Figure 13.

Surface element distribution of HR3C in supercritical CO2 at 550℃for 1000 h.

Figure 13.

Surface element distribution of HR3C in supercritical CO2 at 550℃for 1000 h.

Figure 14.

Surface element distribution of HR3C in supercritical CO2 at 600℃for 200 h.

Figure 14.

Surface element distribution of HR3C in supercritical CO2 at 600℃for 200 h.

Figure 15.

Surface element distribution of HR3C in supercritical CO2 at 600℃for 1000 h.

Figure 15.

Surface element distribution of HR3C in supercritical CO2 at 600℃for 1000 h.

Figure 16.

Three-dimensional element distribution diagram of HR3C steel after oxidation in S-CO2 at 550 ℃ for 1000 h.

Figure 16.

Three-dimensional element distribution diagram of HR3C steel after oxidation in S-CO2 at 550 ℃ for 1000 h.

Figure 17.

Three-dimensional element distribution diagram of HR3C steel after oxidation in S-CO2 at 600 ℃ for 200 h.

Figure 17.

Three-dimensional element distribution diagram of HR3C steel after oxidation in S-CO2 at 600 ℃ for 200 h.

Figure 18.

Three-dimensional element distribution diagram of HR3C steel after oxidation in S-CO2 at 600 ℃ for 1000 h.

Figure 18.

Three-dimensional element distribution diagram of HR3C steel after oxidation in S-CO2 at 600 ℃ for 1000 h.

4. Conclusions

The oxidation behavior of HR3C in supercritical carbon dioxide at approximately 600 °C follows a parabolic rate law, whereas at 550 °C, the oxidation kinetics deviate from this parabolic relationship. HR3C exhibits a relatively low oxidation weight gain, indicating superior oxidation resistance. The oxide layer formed on the surface of HR3C is predominantly composed of Cr₂O₃, with a minor amount of Fe₂O₃ also detected. As a protective oxide layer, Cr₂O₃ effectively reduces the ionic diffusion rate. Carbon is enriched at the interface between the oxide film and the supercritical CO₂ environment, and a limited amount of carbon is also observed at the oxide film/matrix interface and within the matrix.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.Y.; Methodology, K.Y.; Software, S.L.Zhang.; Validation, X.W.Fu.; Formal analysis, X.W.Fu.; Investigation, S.L.Zhang.; Data curation, Z.L. Z.; Writing-original draft, S.L.Zhang.; Writing-review & editing, Z.L. Z.; Visualization, Z.L. Z; Supervision, K.Y.; Project administration, Z.L. Z; Funding acquisition, K.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Please add: This research was funded by the Science and Technology Program of CSEI, grant number 2023youth16.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the

appropriate author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- He, L.-F.; Roman, P.; Leng, B.; Sridharan, K.; Anderson, M.; Allen, T.R. Corrosion behavior of an alumina forming austenitic steel exposed to supercritical carbon dioxide[J]. Corrosion Science 2014, 82, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, G.; Firouzdor, V.; Sridharan, K.; Anderson, M.; Allen, T.R. Corrosion of austenitic alloys in high temperature supercritical carbon dioxide [J]. Corrosion Science 2012, 60, 246–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Jiang, D.; et al. Oxidation behavior of austenitic steel Sanicro25 and TP347HFG in supercritical water[J]. Materials and Corrosion 2019, 70, 1087–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, G.; Firouzdor, V.; Sridharan, K.; Anderson, M.; Allen, T.R. Corrosion of austenitic alloys in high temperature supercritical carbon dioxide [J]. Corrosion Science 2012, 60, 246–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furukawa, T.; Inagaki, Y.; Aritomi, M. Corrosion behavior of FBR structure minerals in high temperature supercritical carbon dioxide [J]. J. Power Energy Syst. 2010, 4, 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.; Anderson, M.; Taylor, D.; Allen, T.R. Corrosion of austenitic and ferritic-martensitic steels exposed to supercritical carbon dioxide[J]. Corrosion Science 2011, 53, 3273–3280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivares, R.I.; Young, D.J.; Marvig, P.; et al. Alloys SS316 and hastelloy-C276 in supercritical CO2 at high temperature[J]. Oxidation of Metals 2015, 84, 585–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.-F.; Roman, P.; Leng, B.; Sridharan, K.; Anderson, M.; Allen, T.R. Corrosion behavior of an alumina forming austenitic steel exposed to supercritical carbon dioxide [J]. Corrosion Science 2014, 82, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, A.; Smart, D.W. Transport of nickel and oxygen during the oxidationof nickel and dilute nickel/chromium alloy. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1988, 135, 2886–2893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, J.; Manning, M.I. Criteria for formation of single layer duplex layer,and breakaway scales on steels. Mater. Sci. Technol. 1988, 4, 1064–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, D.; Huczkowski, P.; Olszewski, T.; Huttel, T.; Singheiser, L.; Quadakkers, W.J. Non-steady state carburisation of martensitic 9–12%Cr steels in CO2 rich gases at 550◦C. Corros. Sci. 2014, 88, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.M.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, P.; Yan, J.B. Effect of carbon on microstructure and mechanical properties of HR3C type heat resistant steels [J]. Materials Science and Engineering: A 2020, 784, 138943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouillarda, F.; Furukawa, T. Corrosion of 9-12Cr ferritic–martensitic steels in high-temperature CO2 [J]. Corrosion Science 2016, 105, 120–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlenbrock, S.; Scharfschwerdt, C.; Neumann, M.; et al. The influence of defects on the Ni 2p and O 1s XPS of NiO [J]. J. Phys-Condens Mat 1992, 40, 7973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Wu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Han, E.-H. Analyses of oxide films grown on Alloy 625 in oxidizing supercritical water[J]. J. of Supercritical Fluids 2008, 47, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.; Han, E.-H.; Wu, X. Corrosion behavior of Alloy 690 in aerated supercritical water [J]. Corrosion Science 2013, 66, 369–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Tang, H.; et al. Oxidation behaviors of porous Haynes 214 alloy at high temperatures [J]. Mater. Charact, 2015, 107, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, M.G.E.; McEnaney, B.; Scott, V.D. Diffusion and Partitioning of Elements in Oxide Scales on Alloys. Nature Physical Science 1972, 237, 140–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleave, C. Study of mechanism of corrosion of some ferritic steels in high pressure carbon dioxide with the aid of oxygen-18 as tracer. Proc. Royal Soc. London A 1982, 379, 427–429. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, J.Y.; Mckrell, T.J.; Eastwick, G.; Ballinger, R.H. Corrosion of materials in supercritical dioxide environment. In Proceedings of the NACE-2008, New Orleans, LA, March; 2008; pp. 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Rouillard, F.; Moine, G.; Tabarant, M.; et al. Corrosion of 9Cr steel in CO2 at intermediate temperature II: mechanism of carburization [J]. Oxid Met. 2012, 77, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firouzdor, V.; Sridharan, K.; Cao, G.; Anderson, M.; Allen, T.R. Corrosion of a stainless steel and nickel-based alloys in high temperature supercritical carbon dioxide environment[J]. Corrosion Science 2013, 69, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).