1. Introduction

Virtual Reality (VR) software applications for learning STEM subjects offers a transformative approach to education by providing immersive, interactive, and engaging environments that enhance understanding of complex and abstract concepts. VR's ability to simulate real-world scenarios and environments that are otherwise inaccessible makes it a valuable tool in STEM education. Various VR platforms and frameworks have been developed for STEM education, including ScienceVR for science laboratories [

1] , Unity-based modules for K-12 education [

2], and smartphone-based VR plotting systems [

3]. These tools enable the creation of 3D visualizations and interactive simulations, enhancing students' understanding of complex concepts. Studies have demonstrated that VR can improve learning efficiency, especially when incorporating environmental traversal capabilities. [

4]

VR has been successfully implemented in various STEM fields, such as engineering and chemical experiments, demonstrating its effectiveness in improving spatial skills and knowledge retention, student motivation, engagement and overall learning outcomes. [

5,

6]

Starting from the advantages of STEM education through virtual reality (VR), in our research, we aim to assess the effectiveness of an original software designed for acquiring knowledge in hydrodynamics. The information provided by the software enables the assimilation of the necessary knowledge for understanding the basic principles of building a small-scale submarine and experimenting how the shape and properties of the ensemble affects the way it behaves in a simulated underwater environment. This software has been tested during the Underwater Engineering course, at Ecole de Mines Paris, offering students an additional opportunity to prototype and iterate on their ideas.

On the other hand, gaining a deep understanding of the unique characteristics of the VR-based learning process is essential, as it empowers students to actively contribute to the iterative refinement of educational software aimed at fostering specialized expertise. Before the software was used in the classroom, in relation with a specific set of learning outcomes, we were interested to assess if this software accomplishes the criteria of a VR-based application suitable for learning.

While numerous VR applications support STEM learning, few combine realistic water simulations with intuitive, rapid skill acquisition. Existing educational tools often rely on generic physics engines unsuitable for accurately representing complex underwater forces. This gap limits their educational effectiveness, particularly in advanced engineering courses requiring high-fidelity simulations. Addressing this, our application introduces a specialized, custom-developed physics engine explicitly tailored for hydrodynamics and submarine modelling, significantly enhancing realism and practical applicability. Furthermore, the software is designed for rapid mastery compared to traditional CAD tools, facilitating wider accessibility and improved learning outcomes for engineering students.

Virtual laboratories have been increasingly utilized in STEM higher education curricula for over twenty years, indicating a significant shift towards digital learning environments. One of the primary advantages of virtual labs is their cost-effectiveness. They provide a viable alternative for any academic field that may not have the financial resources to maintain physical laboratory spaces and equipment.

Mobile VR platforms and low-cost solutions make VR an affordable technology, more accessible to educational institutions, allowing for broader implementation in teaching activities. [

5,

7] The software should be accessible to educational institutions, with low-cost hardware options like head-mounted displays and haptic gloves. [

8] Usually, STEM faculties have developed various techniques to integrate virtual labs into both classroom and laboratory activities. This adaptability showcases the versatility of virtual labs in enhancing educational experiences.

Another advantage is that virtual labs serve as a safe alternative for conducting experiments that could pose risks to individual safety. VR creates three-dimensional digital environments that allow students to interact with and explore complex STEM concepts in a controlled, safe setting. This is particularly beneficial for experiments that are dangerous or impossible to conduct in a traditional classroom setting. [

6,

9] The sense of presence and active learning through movement and gestures in VR environments enhances the learning experience, making abstract concepts more tangible. [

10]

However, difficult challenges remain in designing effective VR experiences for education, with researchers proposing design principles and guidelines to optimize learning outcomes. [

10,

11,

12,

13]. This study explores the application of VR in facilitating underwater engineering education for students, focusing on its use within a highly non-intuitive environment that is hard to mentally construct and visualize.

More precisely, the research questions we wanted to answer during this research were:

How effective was the new VR software for the proposed learning outcomes?

Have the students been able to achieve a state of flow during the learning process while immersed into the digital learning environment?

How aligned were the design decisions of the software to the satisfaction scores expressed by the students?

2. Features of VR for STEM education

To assure an effective learning environment, the VR software should accomplish a set of criteria, aiming to assure the standard for an educational tool. The literature identifies key features that the VR software should exemplify, while advancing arguments regarding the methodological approach to designing our new product.

Efficient VR software for STEM education is characterized by its ability to create high levels of immersion, interactivity, and engaging learning environments. These features are crucial for motivating students and improving their learning outcomes in STEM disciplines.

2.1. Immersive Learning Environment

Immersive features of Virtual Reality (VR) software are pivotal in creating engaging and realistic experiences across various domains, including STEM. The sense of presence that immersive VR provides, which enhances engagement and learning experiences. The immersive nature of VR is achieved through a combination of technological and design elements that simulate real-world experiences in a virtual environment. These features leverage advanced visualization, interaction, and sensory integration to enhance user engagement and understanding. Additionally, the design of VR environments must ensure sufficient fluidity and immersion to avoid negatively impacting learning outcomes. [

5,

14]

VR's immersive features allow for personalized learning experiences, helping students understand and explore complex and abstract concepts that are often difficult to replicate in traditional educational settings through interactive and engaging methods. [

15] VR is used in training scenarios to replicate real-world tasks, utilizing scripting and game engines to create customizable and adaptive training environments. [

16]

The effectiveness of immersive features in educational VR applications is mixed, highlighting the need for careful alignment of design features with educational goals. [

17] While immersive features in VR software offer significant potential for enhancing user experiences, they also present challenges that need to be addressed. VR applications should provide a high degree of immersion, allowing students to feel present within the virtual environment. This is essential for engaging students and enhancing their learning experience. [

10,

14] The effectiveness of VR in translating immersive experiences into academic performance requires further exploration. [

18]

2.2. Interaction: 360-Degree Video and Head-Mounted Displays

These technologies are crucial in VR documentaries, allowing viewers to explore environments from all angles, thereby increasing emotional engagement and empathy. [

19]

VR software utilizes high-resolution graphics and 3D modelling to create realistic environments. This is evident in applications like digital media interactive art, where deep learning models enhance the immersive experience by improving modelling accuracy and the sense of presence.[

20] Platforms like CAVE and head-mounted displays provide a profound sense of immersion by creating a neuropsychological sense of 'being there'. [

21]

Multisensory virtual environments, such as the Multi-Sensory Virtual Decision -Making Center, facilitate collaborative learning by allowing multiple users to engage in real-time decision-making. This approach not only improves the educational experience but also enhances teamwork and communication skills among students.

The design of VR experiences must be carefully aligned with the intended outcomes to maximize their effectiveness. As VR technology continues to evolve, it is expected that these challenges will be mitigated, leading to more widespread adoption and innovation across various fields.

2.3. Interactive Learning

VR applications, such as educational games and simulations, have been shown to increase student motivation and engagement by making learning more interactive and enjoyable. [

6,

22] Applications should enable students to interact with virtual objects and environments, facilitating hands-on learning and exploration. This can be achieved through advanced interfaces like hand gesture recognition. [

5,

23] VR applications should offer customizable environments that cater to individual learning needs, allowing students to explore topics at their own pace and according to their interests. [

14]

The promotion of active learning through movement and gestures in a three-dimensional virtual environment can lead to a deeper understanding and retention of knowledge. [

5] Effective Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) is central to immersive experiences, allowing users to interact with virtual environments seamlessly. [

24] In educational settings, VR applications often include interactive elements that allow users to manipulate and explore abstract concepts, although narrative and social features are less commonly integrated. [

17]

The software should adapt to the learner's progress, providing tailored feedback and challenges to optimize learning outcomes. [

25,

26] It should be scalable to accommodate different educational settings, from individual learners to large classrooms. [

27]

Efficient VR software should support collaborative learning, enabling students to work together in virtual spaces, share ideas, and solve problems collectively. Incorporating social elements can enhance engagement and motivation, making learning more enjoyable and effective. [

28] While VR offers significant advantages for STEM education, challenges such as the need for teacher training and the integration of VR into existing curricula must be addressed.

2.4. Gamification in STEM VR Education

Different game design elements within virtual reality environments have the role to enhance learning experiences in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. This approach aims to increase student engagement, motivation, and knowledge retention. The use of gamification and personalized learning in VR environments can further captivate students' attention and encourage exploration and discovery. [

29]

Common gamification mechanisms in VR include rewards, challenges, and avatars. Elements such as content unlocking, point systems, task difficulty levels, and achievement systems are frequently used to create engaging learning environments. These elements are designed to motivate students by providing immediate feedback and a sense of progression. [

30]

VR platforms like the VR Escape Room and VR Coding provide interactive and immersive experiences that encourage critical thinking and problem-solving. These environments allow students to actively participate in their learning process, moving away from passive listening to engaging with the content in a meaningful way. [

31]

The Atomic Structure Virtual Lab exemplifies how VR can be personalized to meet individual learning needs. It incorporates gamification elements and instant feedback, making it accessible to a diverse range of students, including those with hearing impairments. This personalization helps cater to different learning paces and styles, enhancing the overall educational experience. [

29]

Studies have shown that gamified VR environments significantly improve student engagement and motivation. For instance, the use of a gamified 3D virtual world for teaching computer architecture resulted in higher engagement levels and improved learning outcomes among engineering students. [

32]

While gamification can enhance learning, it is essential to balance game elements to avoid negative impacts on intrinsic motivation. For example, the use of high scores and achievements can lead to increased competition, which may detract from the learning experience. [

33]

3. Original VR software to teach hydrodynamics

Building on the above-mentioned aspects, a software application was designed to be used for learning the fundamentals of hydrodynamics, necessary for designing a submarine.

Submarine Simulator is a custom-made application created by us in Unity that facilitates engineering education both in Virtual Reality (VR) and Augmented Reality (AR). The application consists of three main modes:

-

Environment Selection: once immersed in VR, the students can choose a virtual environment before beginning the construction process of a small-scale submarine model. The application currently allows students to choose from immersing themselves into an open world, a garage, a hangar or an open space in nature (

Figure 1). At this stage, students have the option to switch to augmented reality (AR) instead of virtual reality (VR). This allows them to perceive their surrounding physical environment while utilizing a real table as a blended digital-physical canvas to initiate the construction process.

-

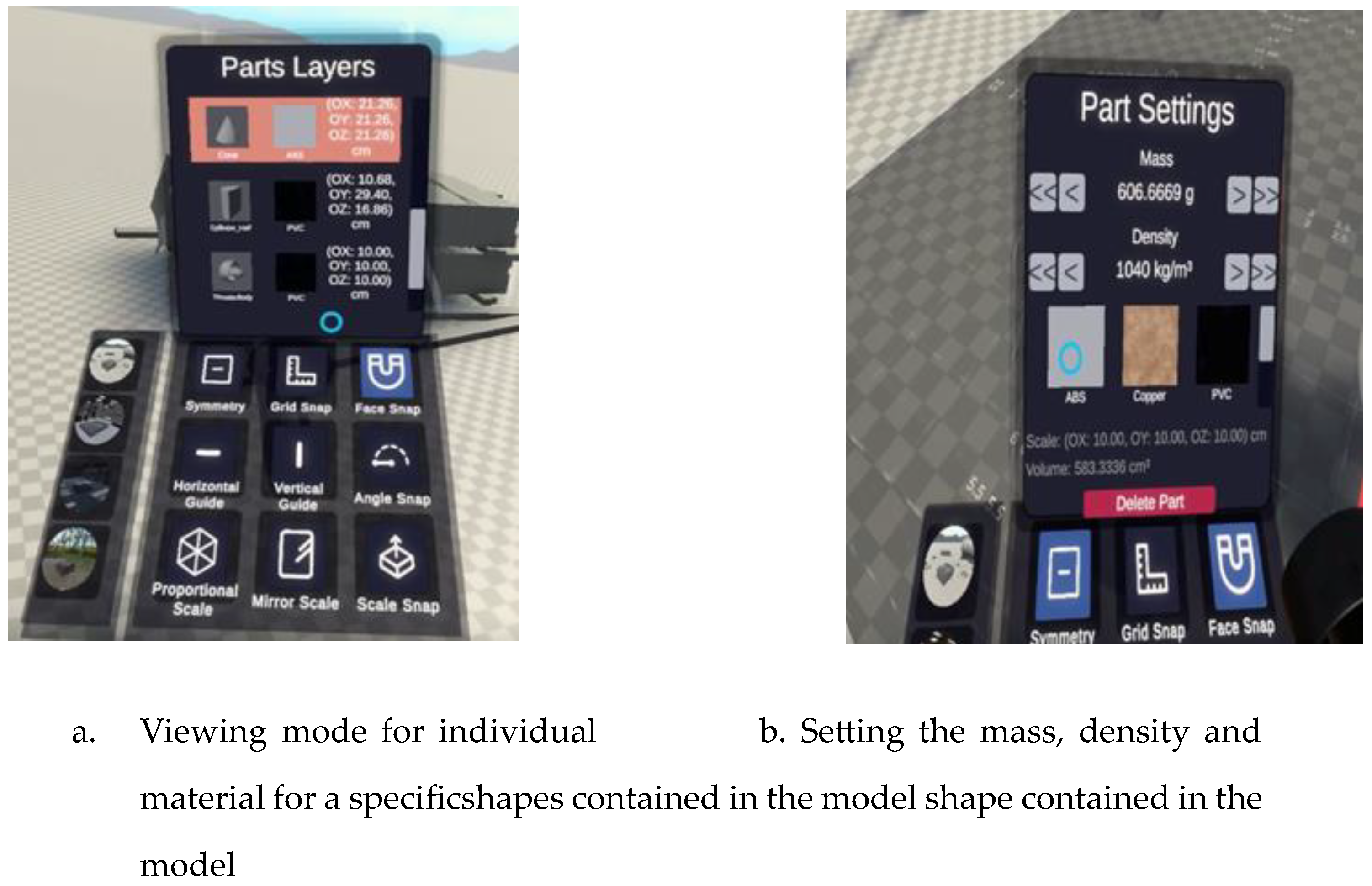

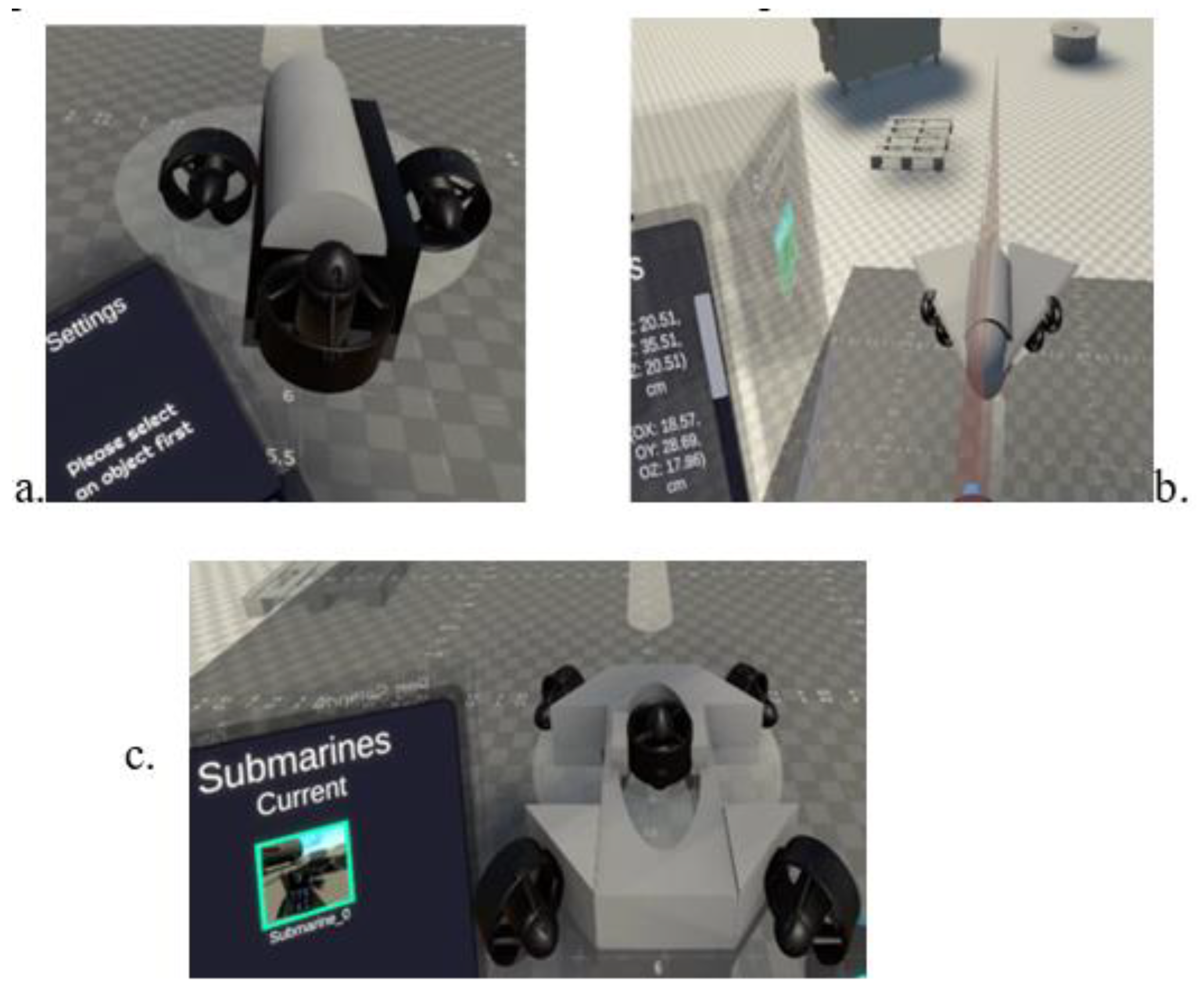

Construction Scene: after picking their favourite virtual environment, the students can use the VR controllers to drag, drop and combine different 3D shapes to create a submarine model. (

Figure 2) They have multiple construction instruments and functions that allow for building with precision. Additionally, the students can change the weight, density and material of each of the shapes added to the environment. Once the students decide that the shape of the submarine is complete, they may also attach motors. If the student has selected to use AR, all the previously - mentioned activities will be made by manipulating holograms which will be blended with the real space around them.

-

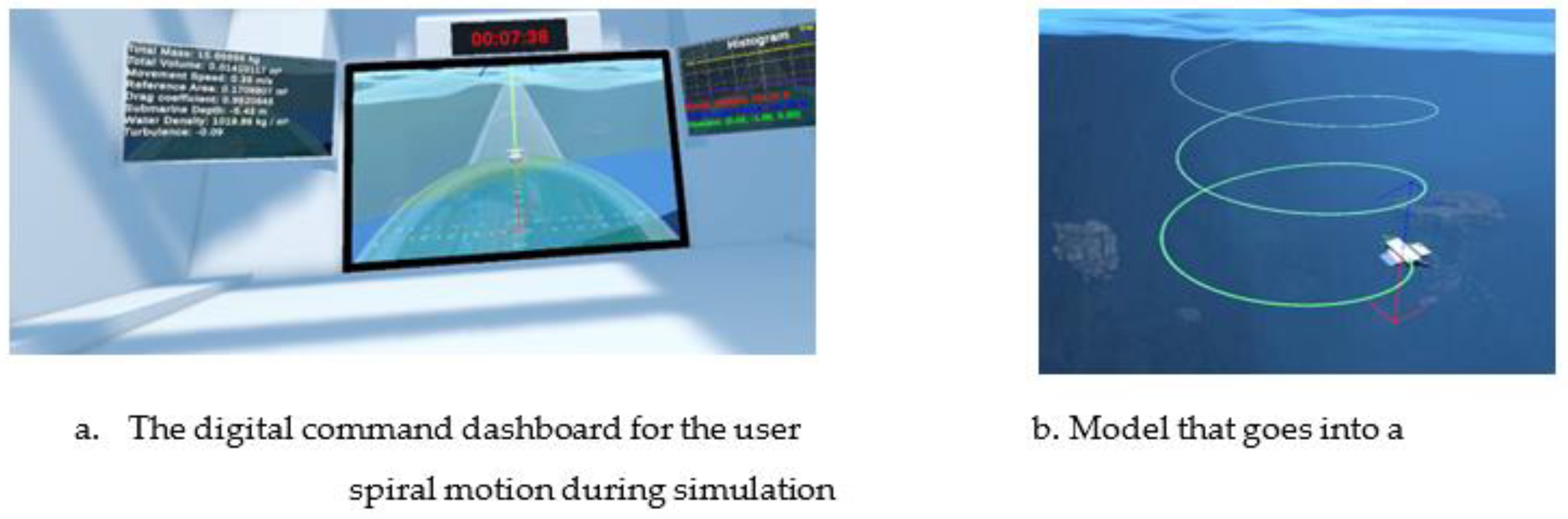

Simulation Scene: after completing the submarine model, the students can test it in a simulated underwater scene. (

Figure 3) Based on preference, they can control the submarine either from a 3

rd person or 1

st person perspective. The scene includes a hyper-realistic water simulator that supports the player in understanding how the previously created model behaves underwater. Using the motors attached previously, they can control the submarine, navigate underwater, visually understand how the thrust and the previously defined characteristics of the submarine model interact with the water environment based on hydrodynamic principles.

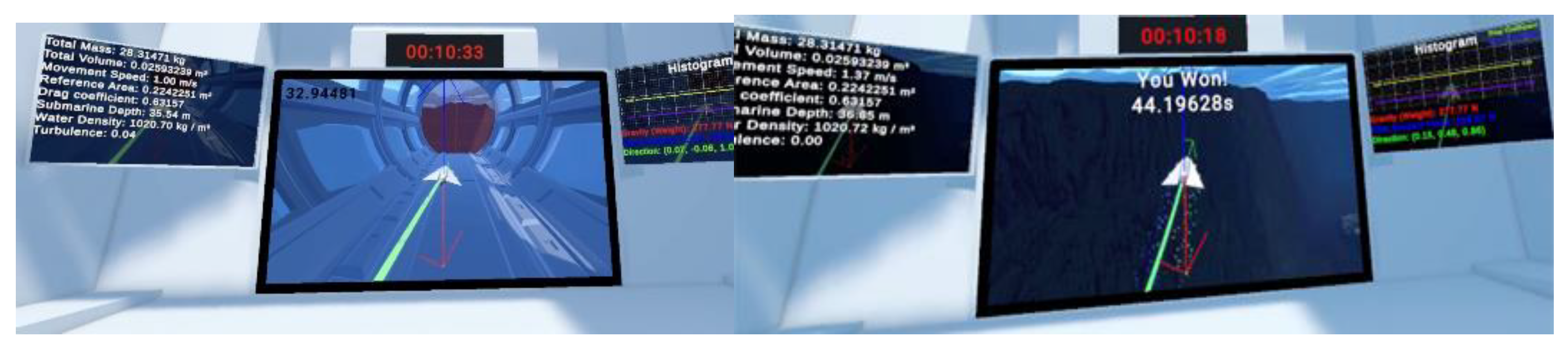

Gamification - Gamification in VR has been linked to better knowledge retention and understanding. (

Figure 4) The integration of game elements helps students grasp complex concepts more effectively, as seen in the positive feedback from students using the VR Coding system for learning computational thinking. [

31,

32,

33]. Our setup leverages gamification principles—such as points, leaderboards, real-time competition, and immediate feedback—to transform the learning process into an interactive and motivating experience. These principles deepen comprehension by encouraging problem-solving in a dynamic VR context, where failures and successes provide direct learning opportunities.

In our testing process, participants had the opportunity to test their custom-designed 3D submarine models by competing in virtual underwater racetracks, all simulated within the immersive VR environment. Upon successfully completing a race, students earned points based on their performance and could view their final completion time for the specific track. To enhance engagement, the system supported real-time multiplayer racing, where users could compete against their colleagues. This was facilitated through visual "shadow" representations of peers' submarines, allowing participants to see and react to others' progress dynamically throughout the course. Ultimately, students achieving the highest cumulative scores across races were declared winners, fostering a competitive and collaborative learning atmosphere.

Worth noting that the facilitator of this VR/AR educational experience will be able to see in real-time everything that the students can see through their glasses. By doing so, they can guide and support their students accordingly.

4. Methodology

The assessment of the value inherent in virtual reality (VR) software requires a comprehensive methodology that encompasses various dimensions, including performance, usability, user engagement, and the context in which the software is employed. The evaluation process is very important for the identification of potential challenges and for ensuring that the software effectively fulfils its intended objectives.

4.1. Research Objectives

The main objective of the research was to verify the effectiveness of the original software (named Submarine Simulator) in the Underwater Engineering course, within the 4th year of study, Engineering bachelor's program at Ecole des Mines Paris (France).

4.2. Research methods

Core Elements of Gaming Experience (CEGE) questionnaire was applied at the end of the third practice session (or Phase 3, as described in the research design subchapter 4.4) in VR and was used to assess performance metrics related to the VR software.

Performance encompasses technical parameters including refresh rate, and resolution, which are essential for facilitating a seamless and engaging virtual reality experience. According to literature [

34], the Mean Opinion Score (MOS) was employed to measure these parameters, offering a subjective evaluation of quality derived from user feedback.

Usability testing represents a prevalent methodology for assessing virtual reality applications, emphasizing the efficacy of user interaction with the software. This process encompasses the evaluation of the user interface, navigation mechanisms, and the comprehensive user experience to detect any potential design deficiencies. [

35,

36] For the usability evaluation, the Affordance test was used, as it can highlight this specific feature of the software.

The Flow State Scale (FSS) was applied at the second practice session (or Phase 2, as described in the research design subchapter 4.4) of the experience and was used to assess the efficiency with which the virtual reality software application engages and sustains user interest. The user experience was assessed through feedback and engagement analytics, providing valuable insights into the software’s ability to deliver a fully immersive and focused experience.

Experience Quality: The calibre of the user experience is further appraised through variables such as motion sickness, which can profoundly influence user comfort and overall satisfaction. Instruments have been devised to evaluate the propensity of virtual reality software to elicit simulator sickness, consequently enhancing user tolerability. [

37] To assess the engagement and experience quality the Affordance questionnaire was applied after the first practice session (or Phase 1, as described in the research design subchapter 4.4)

From the contextual and stakeholder perspective [

36], it is essential in the development and evaluation of VR applications to understand the values and objectives of different stakeholders, which can guide the design and evaluation process to ensure the software meets its intended goals. So, for educational VR applications, evaluation methods often include the Technology Acceptance Model and flow tests to assess how well the software supports learning objectives. In our case, we already assessed the immersivity through the CEGE, FSS and Affordance.

Statistical methods. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) using path models is useful because, unlike other statistical techniques, it allows for the investigation of structural relationships between latent and observed variables. It provides a coherent explanatory model of causal mechanisms, highlighting both the direct and indirect effects of independent variables on a dependent variable within a theoretically specified network of relationships. A CFA Path Analysis was conducted to determine the relationship between the software features, as evaluated by students, by using SmartPLS.[

38,

39]

4.3. Target group

The software was tested on 26 students, in their 4th year at Ecole des Mines Paris, engineering specialisation. Each student completed all three phases described in the research design subchapter 4.4.

All students agreed to participate in the evaluation of the VR software. To maintain the anonymity of the participants, no student names were used at any stage of the evaluation. Only randomly assigned numerical codes have been used for reference purposes.

4.4. Research design

The research was designed as a succession of three sessions in which students have been given different tasks to become proficient in using the VR software.

Duration: 5 weeks of experiments. Each student went through 3 phases. Phases 2 and 3 have been conducted after approximately 7 days after the previous.

This study was embedded within a 3-month, on-site course dedicated to the design and prototyping of mid-sized underwater remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) ranging from 50 to 150 cm in length. The participant cohort consisted of a highly homogeneous group of 26 students, all with similar backgrounds in engineering, comparable prior experience in basic robotics, electronics, programming and computer vision, alongside demographic uniformity (predominantly aged 22–28, from the same university program). This homogeneity was intentionally maintained to control variables such as skill disparity, prior knowledge gaps, and varying learning paces, thereby enabling a more standardized assessment of the VR software.

The following phases were designed and executed by each of the participants:

Phase 1 – The students have been introduced to the capabilities of the software using a 10-min video explanation. Afterwards, the students were invited to get immersed into VR and have been guided step-by-step tutorial by a facilitator to understand the basic commands and functions for constructing and testing small-scale submarine models. Lastly, once showing a basic level of understanding and comfort while using the software, the students were given a construction task such as:

“Please build a submarine model made from 4 shapes and 2 motors. The purpose of the submarine is to be as stable and controllable as possible. The submarine should be able to move forwards, left and right with a high level of control.”

The students had complete creative freedom during the construction process and were allowed to ask questions to the facilitator during the experience. The task had a hard deadline of 15 minutes. No students have stayed for more than 45 minutes in VR during this session.

Phase 2 – This phase has been conducted after approximately 7 days after the first one. Once immersed, students have been given 2-3 minutes to re-accommodate to the VR software and to remember all controllers and building functions. After that, they were given two construction tasks – to create a submarine model that moves in a tight spiral and another submarine model that moves in a loose spiral. (

Figure 5)

The minimum number of shapes to be used was set to 5 and the minimum number of motors to be used was set to 2. The students had 30 minutes to complete both tasks in any order they wanted.

Phase 3 – This phase has also been conducted after approximately 7 days after the second phase. Once immersed, students had to create a submarine model that had to move successfully through an obstacle course using different construction functionalities. (

Figure 6)

There were three obstacle courses - a simple, straight line, one which forced students to control the submarine left and right and one which forced students to also control the submarine up and down.

To determine the relationship between user perception and the software features provided by the technical solution, the following variables have been found as critical and relevant in our analysis (

Table 1).

5. Results

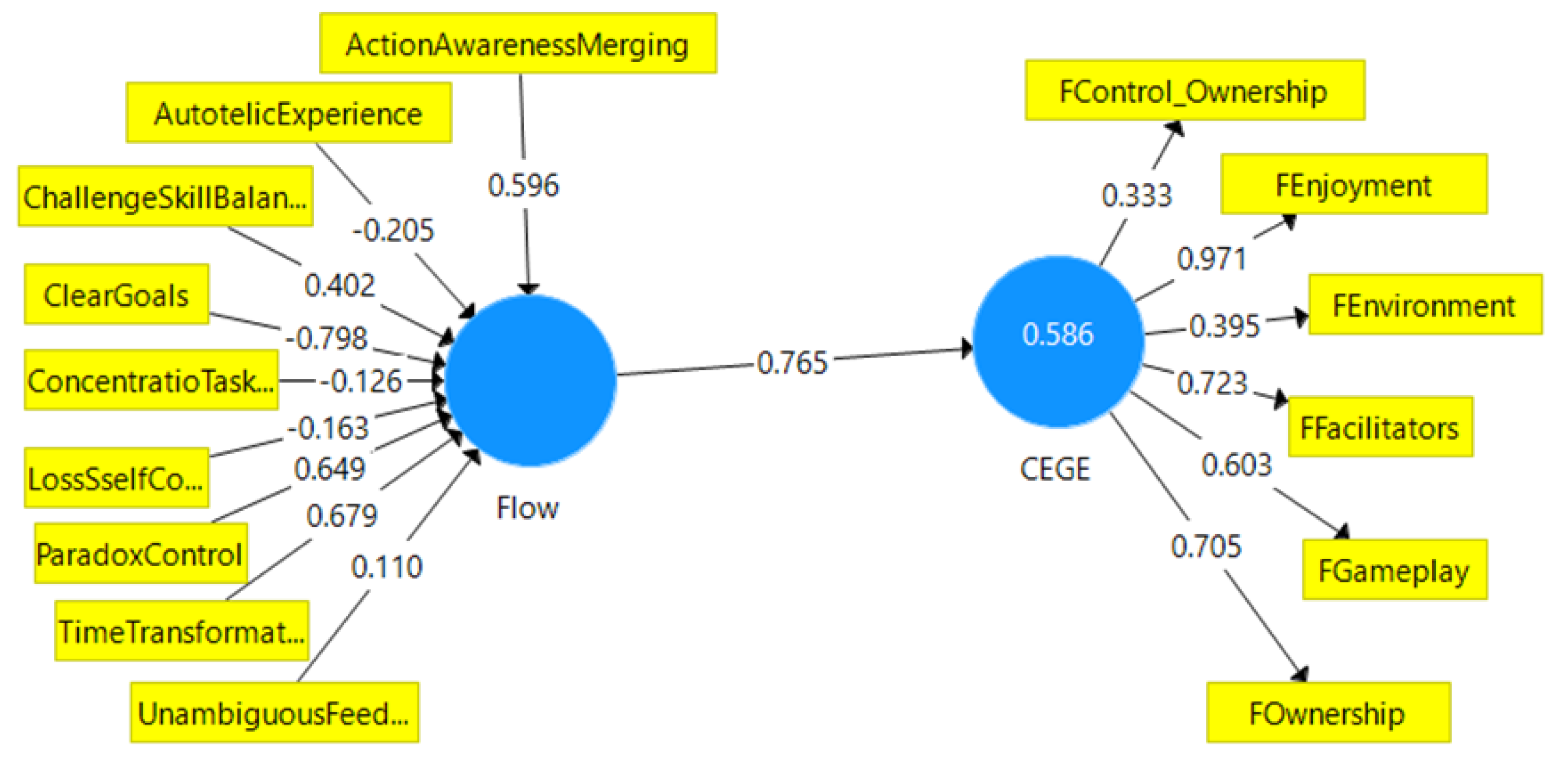

To answer the research questions, a CFA Path factor analysis has been applied, which resulted in a model comprising the formative variables: Flow State (FLOW), Affordance/Usability (AFF) and the reflective variable: the Core Elements of the Gaming Experience (CEGE), with the items presented in

Table 1.

The statistical analysis provides robust evidence that the immersive and usability affordances of the VR software substantially influence user engagement and the quality of their learning experience. Specifically, the high path coefficients (0.811 and 0.765) indicate strong predictive relationships, demonstrating practically that intuitive interaction and realism directly contribute to achieving an optimal learning state (flow) among students. (

Figure 7)

However, some statistical validity measures discussed below (such as AVE below recommended thresholds) suggest that particular survey questions might not fully capture all nuances of user experiences or that responses reflected varied interpretations of questionnaire items. Practically, these results imply that minor refinements in measurement items or additional clarifications during data collection could further strengthen empirical validation of the software's educational benefits.

Regarding research question 1, we identified that affordances significantly shape the user's state of flow.

The very high value of path coefficient of the model (0.811) proved the relation verified through the question 1.

Table 2 prints the Coefficient of Determination (R²) that indicates the predictive power of the model, showing the proportion of variance explained by independent variables. Flow (R² = 0.658) shows that 65.8% of the variance in Flow is explained by Affordance, indicating a strong model fit for this relationship. The R² Adjusted (0.644) corrects for model complexity and remains high, showing model stability.

Table 3 prints the effect size for predictors (f²) measuring the impact of an independent variable on a dependent variable. Affordance has a very large effect on Flow, highlighting that ease of use and immersive design are critical drivers of user engagement. This is an exceptionally strong relationship, indicating that VR affordances significantly shape the user's state of flow.

Focus on improving usability, control, and immersion in the VR experience to boost user Flow and enjoyment.

Table 4 presents reliability and validity metrics for the constructs Affordance (AFF) and Flow in the VR environment. AFF is formative variable and no calculus was done. Flow is a reflective variable. Cronbach’s Alpha (CA) for Flow: 0.842 indicates good internal consistency. AFF is formative variable and no calculus was done. The Speraman rho_A coefficient for Flow: 0.862 shows a good reliability. Composite Reliability (CR) for Flow: 0.839 indicates good construct reliability. Average Variance Extracted (AVE) for Flow: 0.407 is below the recommended threshold, meaning it may not explain enough variance in its indicators.

Flow has good internal consistency and reliability (Cronbach’s Alpha, rho_A, and CR are all above 0.7). However, Flow's AVE is low (0.407), which suggests potential validity concerns. This could mean that the indicators for Flow may not sufficiently capture the construct or that there is measurement error.

Table 5 presents Discriminant Validity using the Fornell-Larcker Criterion, which checks whether a construct is distinct from others in a model. Square Root of AVE (Diagonal Values): AFF is likely 0.811. Flow: 0.638 (which is the square root of AVE). The correlation between AFF and Flow (0.811) is strong. Flow’s square root of AVE (0.638) is lower than its correlation with AFF (0.811). This suggests poor discriminant validity, meaning Flow and Affordance might not be clearly distinguishable from one another in the model.

In

Table 6, SRMR (Standardized Root Mean Square Residual) value: 0.121 is not very closed to the maximum threshold 0.10, suggesting the model has a low fit with room for improvement.d_ULS (Unweighted Least Squares Discrepancy) and d_G (Geodesic Discrepancy) Lower values indicate a better fit. Chi-Square Value 81.449 for estimated model is at least equal with the saturated value, thus we can count on model fit NFI=0.509 < 0.80 indicates a poor fit. Low NFI could be due to sample size issues.

The very high value of path coefficient of the model (0.765) confirms the supposed relation between the software characteristics, through flow state and CEGE. (

Figure 8)

Table 7 prints the Coefficient of Determination (R²) that indicates the predictive power of the model, showing the proportion of variance explained by independent variables. CEGE (R² = 0.586) shows that 58.6% of the variance in CEGE is explained by Flow, indicating a strong model fit for this relationship. The R² Adjusted (0.569) corrects for model complexity and remains high, showing model stability.

Table 8 prints the effect size for predictors (f²) measuring the impact of an independent variable on a dependent variable. Flow has a very large effect on CEGE, highlighting that ease of use and immersive design are critical drivers of user engagement. This is an exceptionally strong relationship, indicating that VR affordances significantly shape the user's state of flow.

Focus on improving usability, control, and immersion in the VR experience to boost user Flow and enjoyment.

Table 9 presents reliability and validity metrics for the constructs CEGE and Flow in the VR environment. AFF is formative variable and no calculus was done. Flow is a reflective variable.

Cronbach’s Alpha (CA) for CEGE: 0.793 indicates good internal consistency. Flow is formative variable and no calculus was done. The Speraman rho_A coefficient for Flow: 0.869 shows a good reliability. Composite Reliability (CR) for CEGE: 0.803 indicates good construct reliability. Average Variance Extracted (AVE) for CEGE: 0.432 is below the recommended threshold, meaning it may not explain enough variance in its indicators.

CEGE has good internal consistency and reliability (Cronbach’s Alpha, rho_A, and CR are all above 0.7). However, CEGE's AVE is low (0.407), which suggests potential validity concerns. This could mean that the indicators for Flow may not sufficiently capture the construct or that there is measurement error.

SRMR (Standardized Root Mean Square Residual) Value: 0.107 is very close to the maximum threshold 0.10, suggests the model is very close to be acceptable with room for improvement. d_ULS (Unweighted Least Squares Discrepancy) and d_G (Geodesic Discrepancy) Lower values indicate a better fit. Chi-Square Value 88.938 for estimated model is at least equal with the saturated value, thus we can count on model fit. NFI=0.641 < 0.80 indicates a poor fit. Low NFI could be due to sample size issues. This sample has been made on 26 subjects; thus, we are not worried about the NFI value. (

Table 10)

4. Discussions

Virtual reality (VR) has emerged as a promising tool for STEM education, offering immersive experiences and active learning opportunities. In accordance with the specialized literature, the software we developed meets a series of quality criteria such as usability, fidelity, and pedagogical effectiveness, in accordance with the guidelines provided in the relevant literature. [

8,

10,

16]. Our results indicate that the VR submarine simulator software was moderately to highly effective, as evidenced by pre- and post-test improvements in knowledge retention and self-reported competency among engineering students. This aligns with prior research on VR's role in STEM education, where immersive simulations have been shown to outperform traditional methods in fostering conceptual understanding, particularly in abstract fields like hydrodynamics and physics.

The positive affordance questionnaire responses—where most students reported the software application as intuitive and supportive of task completion—suggest that the VR environment successfully bridged the gap between theoretical knowledge and simulated practice. Our VR application for submarine design and testing provides users with an intuitive and engaging platform to explore complex engineering principles. The application attempts to represent hydrodynamic forces as accurately as possible for a real-time computation, allowing for realistic experimentation and observation. This immersive environment fosters a deeper understanding of theoretical concepts by enabling direct manipulation and real-time feedback, transforming abstract equations into tangible outcomes, in accordance with the learning objectives. [

17].

Secondly, the data reveal that a majority of participants experienced flow, with self-reported metrics (via the Flow State Scale questionnaire) indicating high levels of absorption and enjoyment. Notably, the strong correlation between affordance perceptions and flow suggests that the software's design elements, such as clear navigational cues and responsive interactions, facilitated this state by minimizing frustration and maximizing agency.

This correlation extends to CEGE, including aspects like challenge, control, and feedback, which collectively enhanced immersion. Drawing from Csikszentmihalyi's flow theory, these results imply that VR's ability to create a "presence" in non-intuitive underwater settings—through sensory realism and adaptive difficulty—promotes flow more effectively than passive learning tools.

Furthermore, the application's design actively promotes problem-solving, critical thinking, and iterative design processes. All these are essential conditions for an efficient learning process. [

6,

22,

29] Users can rapidly prototype, test, and refine their submarine models, learning from failures and optimizing their designs in a risk-free virtual space. This hands-on approach, difficult to replicate in traditional educational settings, significantly enhances knowledge retention and skill development.

The interdependencies among affordance, flow, and CEGE offer a compelling theoretical contribution, suggesting an expanded model for VR in education: affordances act as precursors to engagement, mediating flow through gamified structures. This builds on existing models like the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), incorporating psychological flow as a key variable for non-intuitive domains. Practically, these insights advocate for VR developers to prioritize iterative user testing focused on affordances to optimize flow and engagement, potentially revolutionizing underwater engineering pedagogy by making it more experiential and accessible.

For educators, the results imply scalable VR adoption, such as hybrid curricula combining VR with collaborative debriefs to reinforce learning outcomes. Institutions could leverage these correlations to justify VR integration, emphasizing its role in preparing students for industry demands where simulation training is standard.

Our VR submarine application exemplifies the potential of immersive technologies to improve STEM education. We believe it empowers students to not only grasp complex scientific and engineering principles but also to innovate and apply their knowledge in a practical, meaningful way. By prioritizing active learning strategies, the original software design aligns with Johnson and Glenberg’s (2019) call for a transformation in educational practices—one that centers on student interaction and engagement, which are crucial for effective STEM education. [

10]

5. Conclusions

The originality of our VR application is rooted in several key elements that differentiate it from existing educational tools. A cornerstone of this novelty is the customized physics engine specifically designed for the underwater simulation scene. Recognizing the limitations of generic physics engines in accurately representing complex hydrodynamics, we carefully re-engineered over 60% of the code. This extensive process delivered a better level of fidelity and realism to users when testing submarine models, far from simplistic games and into simulation territory. The realistic simulation of buoyancy, drag and fluid dynamics allows for a truly authentic experience that attempts to mirror real-world underwater environments, a critical factor for effective engineering education.

Furthermore, the perceived quality and usability of the application have been independently validated through the Affordance questionnaire, with results indicating a very high rating. This high rating underscores the intuitive design and ease of interaction within the virtual environment, ensuring that users can focus on learning and experimentation rather than struggling with the interface.

Perhaps the most compelling element of novelty is the absence of any other publicly available and mature application that offers a similar comprehensive platform for virtual submarine design and testing. While isolated simulations or design tools may exist, none integrate the full spectrum of design, testing, and realistic physics within an immersive VR environment to the degree our application does. This unique positioning fills a significant gap in STEM education tools, offering an unparalleled opportunity for students and professionals to engage with complex naval architecture and engineering principles in an accessible and engaging way.

Finally, a crucial aspect distinguishing our VR application, particularly from conventional engineering software, is its remarkably low learning curve. Unlike complex Computer-Aided Design (CAD) software, which often requires extensive training and a significant time investment to master, our VR application's intuitive interface and immersive nature allow for rapid acquisition of its building capabilities. During experimental trials, it has been demonstrated that users could effectively learn to utilize the building and testing mode of the VR application in less than one hour. This swift onboarding process dramatically reduces the barrier to entry for learners, making sophisticated design and engineering principles accessible to a much broader audience, including those without prior experience in complex design software. This ease of use not only enhances engagement but also maximizes valuable learning time, allowing users to quickly move from understanding the interface to actively experimenting and innovating.

5.1. Limits and Future Work

In the evaluation process of this software, we highlight an initial limitation related to the relatively small number of participants. Repeating the study with a larger sample size should be linked to accessing a group with similar characteristics. Future studies will focus on the relationship between the effectiveness of the training process and the characteristics of the participants involved in it.

While the evaluation of VR software for educational purposes is comprehensive, it is important to recognize the inherent challenges and limitations in the process itself. One significant limitation lies in standardizing evaluation metrics across diverse VR applications. The immersive and interactive nature of VR introduces variables not typically found in traditional software, such as motion sickness the difficulty in isolating the specific pedagogical gains directly attributable to the VR experience versus other learning modalities. Quantifying the subtle, yet powerful, influence of presence and immersion on learning outcomes remains a complex area of research.

There are some limitations concerning the statistical validity of certain measures. Specifically, AVE and discriminant validity indicators fell below standard thresholds, raising concerns about measurement precision. These issues may result from a small sample size, ambiguous questionnaire formulations or language barriers. To address these limitations in future studies, we recommend refining survey items to more explicitly align with VR affordance and flow constructs. Clearer wording or adding illustrative examples to certain survey questions may improve participant comprehension and response accuracy, enhancing subsequent statistical robustness.

Another challenge involves the long-term retention and transfer of knowledge gained in VR environments. While initial studies often show strong immediate learning, more longitudinal research is needed to determine how well these skills and understandings translate to real-world applications and how durable they are over time. Furthermore, the accessibility and cost of VR hardware can present significant barriers to widespread adoption, particularly in educational institutions with limited budgets. This creates a disparity in access to these advanced learning tools.

Future research should therefore focus on optimizing these environments to maximize their educational potential while addressing these challenges. This includes developing more robust and universally applicable evaluation frameworks that account for the unique characteristics of VR. Exploring how VR can be seamlessly integrated with other teaching methods to create blended learning experiences will be key to unlocking its full potential, ensuring that it complements, rather than replaces, traditional educational approaches.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.B.S., S.T. and R.V.R.; methodology, A.B.S., S.T. and R.V.R..; software, A.B.S..; validation, A.B.S.; formal analysis, A.B.S., S.T. and R.V.R.; investigation, A.B.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.B:S.; writing—review and editing, A.B.S., S.T. and R.V.R.; supervision, S.T. and R.V.R.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created.

Acknowledgments

The research was run within doctoral studies and supervised by the coordinators from École des Mines de Paris and National University of Science and Technology “POLITEHNICA” Bucharest.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Qorbani, H.S. ; Arya, A;, Nowlan, N.S.; Abdinejad, M. ScienceVR: A Virtual Reality Framework for STEM Education, Simulation and Assessment. 2021 IEEE International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Virtual Reality (AIVR), 267-275. [CrossRef]

- Ward, T.; Ortega-Moody, J.; Khoury, S.; Wheatley, M.; Jenab, K. Virtual reality platforms for K-12 STEM education. Management Science Letters. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.R.; Snapp, B.; Madar, S.; Brown, J.R; Fowler, J.; Andersen, M.; Porter, C.D.; Orban, C. A SmartphoneBased Virtual Reality Plotting System for STEM Education. PRIMUS, 1: 33; :1. [CrossRef]

- Nersesian, E.; Vinnikov, M.; Lee, M.J. Travel Kinematics in Virtual Reality Increases Learning Efficiency. 2021 IEEE Symposium on Visual Languages and Human-Centric Computing (VL/HCC), 1-5. [CrossRef]

- Ha, O. Development of a low-cost immersive virtual reality solution for STEM classroom instruction: A case in Engineering Statics. In 2020 2nd International Workshop on Artificial Intelligence and Education (WAIE 2020). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, pp.64–68. [CrossRef]

- Janonis, A.; Kiudys, E.; Girdžiūna, M.; Blažauskas, T.; Paulauskas, L.; Andrejevas, A. Escape the Lab: Chemical Experiments in Virtual Reality, 2020, pp. 273–282. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Laseinde, O. T.; Dada, D. Enhancing teaching and learning in STEM Labs: The development of an android-based virtual reality platform, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Chang, D. Y; Stocksdale, G.; Gunasekera, M.; Rizwan-uddin, R. Recent Advances in VR Labs for Use in STEM Education. Polytechnic University of Valencia Congress, Tenth International Conference on Higher Education Advances, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Klän, W. (2023). Using Virtual Reality to Improve STEM Education. [CrossRef]

- Johnson-Glenberg, M. C. The Necessary Nine: Design Principles for Embodied VR and Active Stem Education, 2019 (pp. 83–112). Springer, Singapore. [CrossRef]

- Semerikov, S.; Mintii, M.; Mintii, I. Review of the course "Development of Virtual and Augmented Reality Software" for STEM teachers: implementation results and improvement potentials. International Workshop on Augmented Reality in Education, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Pirker, J.; Dengel, A.R.; Holly, M.S.; Safikhani, S. Virtual Reality in Computer Science Education: A Systematic Review. Proceedings of the 26th ACM Symposium on Virtual Reality Software and Technology, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Mystakidis, S.; Fragkaki, M.; Filippousis, G. Ready Teacher One: Virtual and Augmented Reality Online Professional Development for K-12 School Teachers. Computers, 1: 10(10). [CrossRef]

- Deck, C. Virtual reality and science, technology, engineering, and mathematics education, 2023, pp. 189–197. Elsevier eBooks. [CrossRef]

- Paskova, A. Features of application of immersive technologies of virtual and augmented reality in higher education. Vestnik Majkopskogo Gosudarstvennogo Tehnologičeskogo Universiteta, 2022, 14(3). [CrossRef]

- Zikas, P.; Papagiannakis, G.; Lydatakis, N.; Kateros, S.; Ntoa, S. ; Adami, I; Stephanidis, C. Immersive visual scripting based on VR software design patterns for experiential training. The Visual Computer, 1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matovu, H. Immersive virtual reality for science learning: Design, implementation, and evaluation. Studies in Science Education. [CrossRef]

- Danmali, S. S. , Onansanya, S. A., Atanda, F. A., & Abdullahi, A. (2024). Application of Virtual Reality in STEM Education for Enhancing Immersive Learning and Performance of At-Risk Secondary School Students. International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Science, VIII(IIIS), 3971–3984. [CrossRef]

- Li, S. An Analysis of Immersive Communication in VR Documentary: A Case Study of Planet Earth II. Communications in Humanities Research. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J. (2023). Immersive Experience Design of Digital Media Interactive Art Based on Virtual Reality. Computer-Aided Design and Applications. [CrossRef]

- Harris, T.M. Immersive virtual reality and spatial analysis, Chapters, in: Sergio J. Rey & Rachel S. Franklin (ed.), Handbook of Spatial Analysis in the Social Sciences, 2022, chapter 20, pages 336-351, Edward Elgar Publishing. Available at https://ideas.repec.org/h/elg/eechap/19110_20.

- Truchly, P.; Medvecky, M. ; Podhradsky, P; Vanco, M. P. Virtual Reality Applications in STEM Education. 2018 16th International Conference on Emerging eLearning Technologies and Applications (ICETA), Stary Smokovec, Slovakia, 2018, pp. 597-602. [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Xiao, X.; Wee, W. G.; Han, C. Y.; Zhou, X. A 3D Virtual Learning System for STEM Education. In: Shumaker, R., Lackey, S. (eds) Virtual, Augmented and Mixed Reality. Applications of Virtual and Augmented Reality. VAMR 2014. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 8526. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Drossis, G.; Birliraki, C.; Stephanidis, C. Interaction with Immersive Cultural Heritage Environments Using Virtual Reality Technologies. In: Stephanidis, C. (eds) HCI International 2018 – Posters' Extended Abstracts. HCI 2018. Communications in Computer and Information Science, vol 852, pp. [CrossRef]

- Gómez, P. M. M.; Gómez, R. J. M. ; Antonio, D; Borré, F. Virtual Immersion in STEM Education: A MICMAC Study on How Virtual Reality Impacts the Understanding and Application of Scientific Concepts. EVOLUTIONARY STUDIES IN IMAGINATIVE CULTURE, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.; Mamani, B.; Salas, C. CollabVR: VR Testing for Increasing Social Interaction between College Students. Computers. 2024; 13(2):40. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers13020040Lynch, T.; Ghergulescu, I. Review of virtual labs as the emerging technologies for teaching stem subjects. INTED2017 Proceedings, 2017, 6082–6091. https://doi.org/10.21125/INTED.2017.1422.

- Lytras, M. D.; Papadopoulou, P.; Misseyanni, A.; Marouli, C.; Alhalabi, W.; Daniela, L. Moving virtual and augmented reality in the learning cloud: design principles for an agora of active visual learning services in stem education. EDULEARN17 Proceedings, 2017, 7673–7678. [CrossRef]

- Mo, J. Improving the Middle School STEM Education in Rural China Through Virtual Reality. 4th International Conference on Educational Reform, Management Science and Sociology. ERMSS, 2023, vol.9. [CrossRef]

- Lynch, T.; Ghergulescu, I. Review of virtual labs as the emerging technologies for teaching stem subjects. INTED2017 Proceedings, 2017, 6082–6091. [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Chen, Q. The Design, Implementation and Evaluation of Gamified Immersive Virtual Reality (IVR) for Learning: A Review of Empirical Studies. Proceedings of the 17th European Conference on Games Based Learning, Vol. 17 No. 1, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Gerini, L.; Delzanno, G.; Guerrini, G.; Solari, F.; Chessa, M. Gamified Virtual Reality for Computational Thinking. Gamify 2023: Proceedings of the 2nd International Workshop on Gamification in Software Development, Verification, and Validation, pp.13-21. [CrossRef]

- Ruscanu, A.-M; Ciupe, A.; Meza, S. arPcTECHture – a gamified educational 3D virtual world for introductory concepts in computer architecture. IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference, 2022, 1437–1442. [CrossRef]

- Tiefenbacher, F. Evaluation of Gamification Elements in a VR Application for Higher Education. In: Yilmaz, M., Niemann, J., Clarke, P., Messnarz, R. (eds) Systems, Software and Services Process Improvement. EuroSPI 2020. Communications in Computer and Information Science, vol 1251. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Xing, L.; Perkis, A.; Jiang, Y. On the Properties of Mean Opinion Scores for Quality of Experience Management. IEEE International Symposium on Multimedia, 2011, pp. 500-505.

- Flowers, L. O. Virtual Laboratories in STEM. International Journal of Science and Research Archive. 1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlGerafi, M.A.M.; Zhou, Y.; Oubibi, M.; Wijaya, T.T. Unlocking the Potential: A Comprehensive Evaluation of Augmented Reality and Virtual Reality in Education. Electronics. 3953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingueti, D.B; Dias, D.R.C.; Guimarães, M.d.P.; Carvalho, D.B.F. Evaluation Methods Applied to Virtual Reality Educational Applications: A Systematic Review. In: Gervasi, O., et al. Computational Science and Its Applications – ICCSA 2021. ICCSA 2021. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 12958. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Bernhard, K.; Henning, S. Development of a software-tool to evaluate the tolerability of different VR-movement types. Health Technol,. [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C. M. , Wende, S., and Becker, J.-M. (2015) "SmartPLS3" Boenningstedt: SmartPLS GmbH. http://www.smartpls.com.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).