Submitted:

23 July 2025

Posted:

24 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Definition of EAI

3. Hardware Platforms of EAI

3.1. Major Hardware Platforms of EAI

3.1.1. MCU

3.1.2. MPU

3.1.3. GPU

3.1.4. FPGA

3.1.5. ASIC

3.1.6. AI SoC

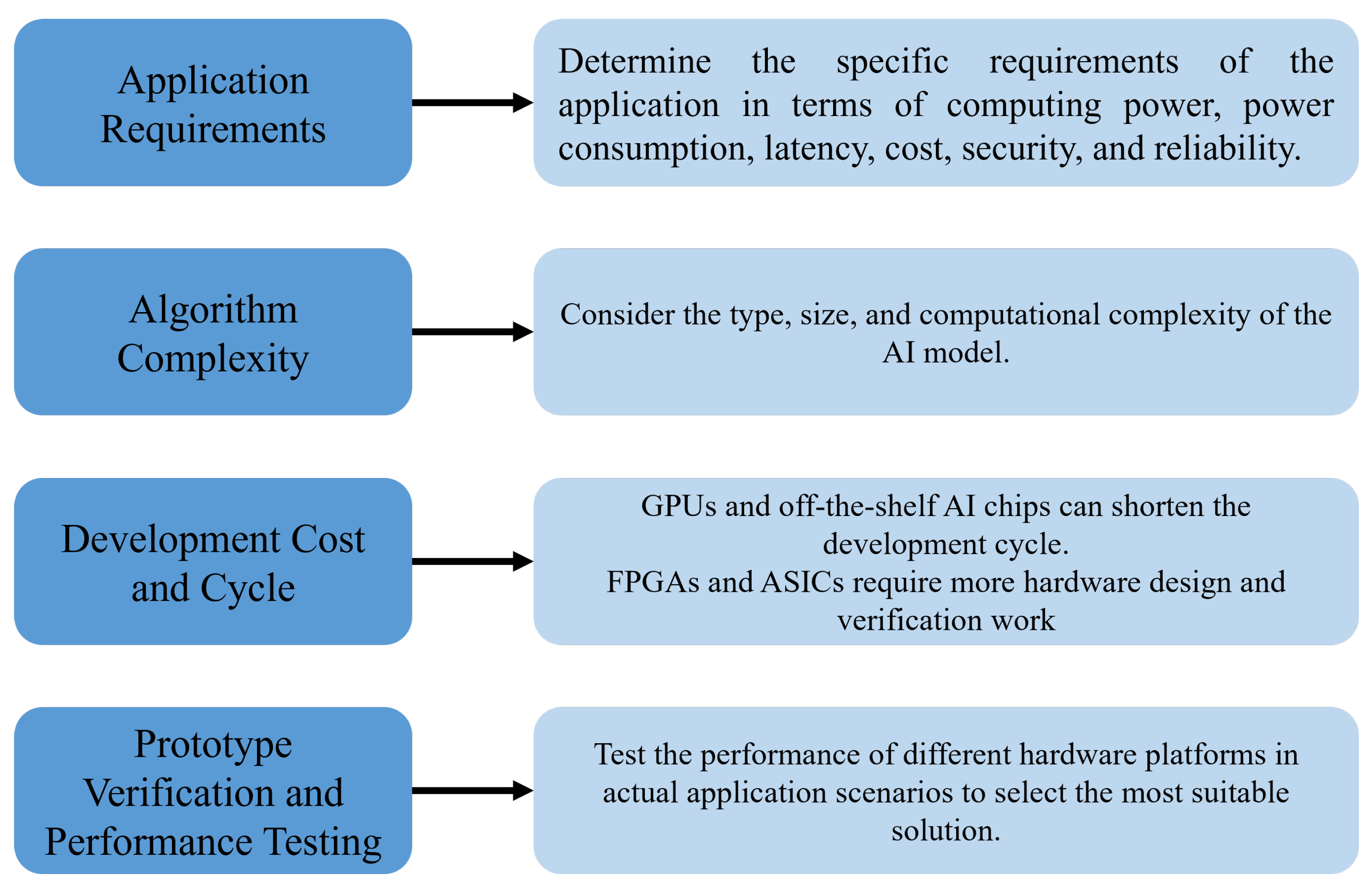

3.2. Hardware Platform Selection Strategy

4. Software Frameworks of EAI

5. Algorithms of EAI

5.1. Traditional ML Algorithms

5.1.1. Decision Trees

5.1.2. Support Vector Machines

5.1.3. K-Nearest Neighbors

5.1.4. Naive Bayes

5.1.5. Random Forests

5.2. Typical Deep Learning Algorithms

5.2.1. Convolutional Neural Network

5.2.2. Recurrent Neural Networks

5.2.3. Transformer Networks

5.3. Lightweight Neural Network Architectures

5.3.1. MobileNet Series

- MobileNetV1 [109]: Proposed by Google, its core innovation is Depthwise Separable Convolutions, which decompose standard convolutions into Depthwise Convolution and Pointwise Convolution, drastically reducing computation and parameters .

- MobileNetV2 [110]: Built upon V1 by introducing Inverted Residuals and Linear Bottlenecks, further improving model efficiency and accuracy .

- MobileNetV3 [111]: Combined NAS technology to automatically optimize network structure and introduced the h-swish activation function and updated Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) modules, achieving better performance under different computational resource constraints.

- MobileNetV4 [112]: builds upon the success of the previous MobileNet series by introducing novel architectural designs, such as the Universal Inverted Bottleneck (UIB) block and Mobile Multi-Head Query Attention (MQA), to further enhance the model’s performance under various latency constraints. MobileNetV4 achieves a leading balance of accuracy and efficiency across a wide range of mobile ecosystem hardware, covering application scenarios from low latency to high accuracy.

5.3.2. ShuffleNet Series

- ShuffleNetV1 [113]: Proposed by Megvii Technology, designed for devices with extremely low computational resources. Its core elements are Pointwise Group Convolution and Channel Shuffle operations, the latter promoting information exchange between different groups of features and enhancing model performance.

- ShuffleNetV2 [114]: Further analyzed factors affecting actual model speed (such as memory access cost) and proposed better design criteria, resulting in network structures that perform better in both speed and accuracy.

5.3.3. SqueezeNet

5.3.4. EfficientNet Series

- EfficientNetV1 [116]: Proposed by Google, it uniformly scales network depth, width, and input image resolution using a Compound Scaling method. It also used neural architecture search to obtain an efficient baseline model B0, which was then scaled to create the B1-B7 series, achieving state-of-the-art accuracy and efficiency at the time.

- EfficientNetV2 [117]: Building on V1, it further optimized training speed and parameter efficiency by introducing Training-Aware NAS and Progressive Learning, and incorporated more efficient modules like Fused-MBConv.

5.3.5. GhostNet Series

- GhostNetV1 [118]: proposed by Huawei Noah’s Ark Lab, introduces the Ghost Module. This module generates intrinsic features using standard convolutions, then applies cheap linear operations to create more "ghost" features, significantly reducing computation and parameters while maintaining accuracy.

- GhostNetV2 [119], also from Huawei Noah’s Ark Lab, enhances V1 by incorporating Decoupled Fully Connected Attention (DFCA) . This allows Ghost Modules to efficiently capture long-range spatial information, boosting performance beyond V1’s local feature focus with minimal additional computational cost.

- GhostNetV3 [120], from relevant researchers, extends GhostNet’s efficiency to ViTs. It applies Ghost Module principles—like using cheap operations within ViT components—to create lightweight ViT variants with reduced complexity and parameters, making them suitable for edge deployment [111-3].

5.3.6. MobileViT

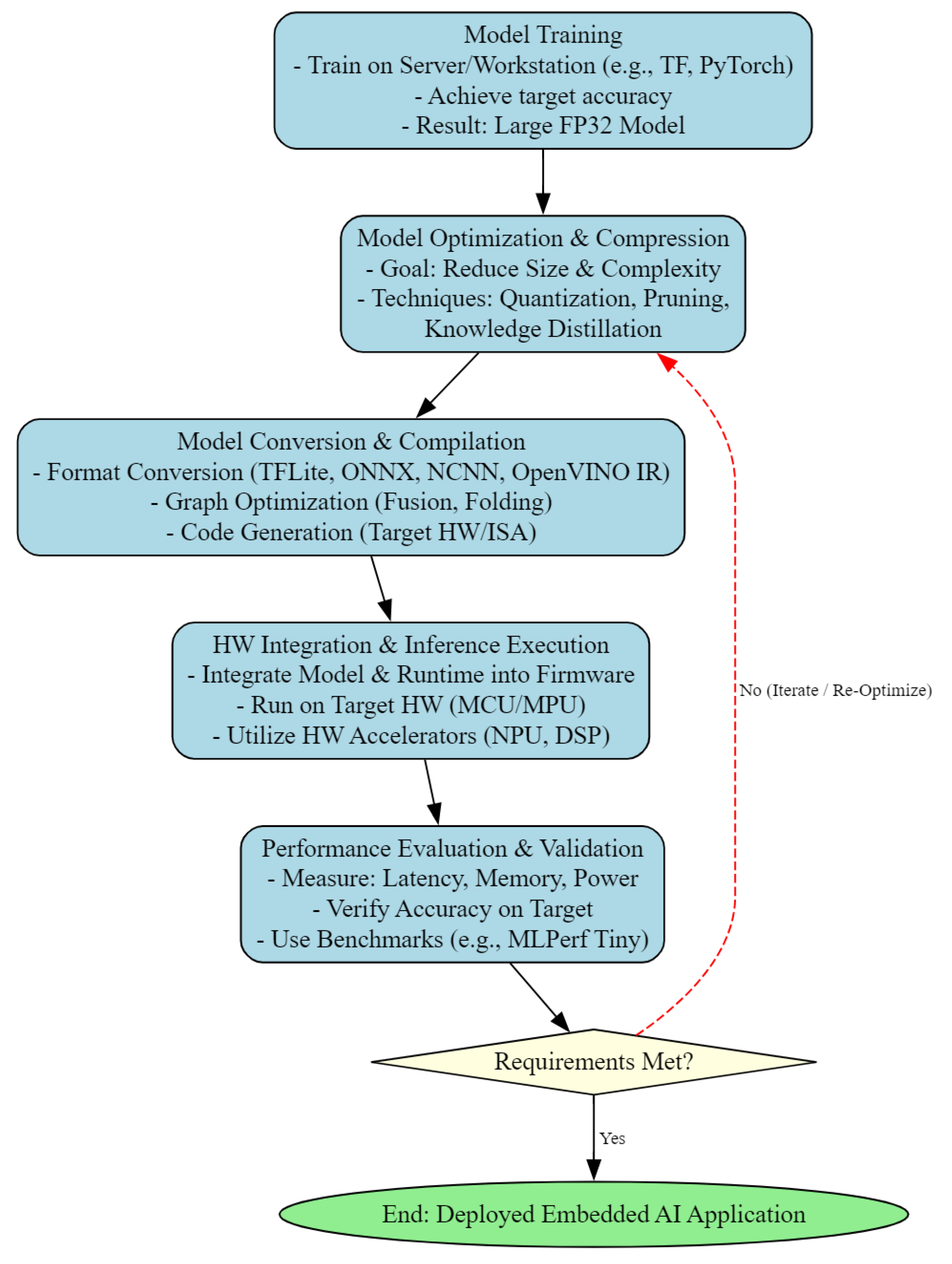

6. Deployment of EAI

6.1. Model Training

6.2. Model Optimization and Compression

- Pruning: Removing redundant weights or structures (e.g., channels, filters) in the model to generate a sparse model, thereby reducing the number of parameters and operations [72].

- Knowledge Distillation: Using a large "teacher" model to guide the training of a smaller "student" model, transferring knowledge to improve the performance of the smaller model [108].

6.3. Model Conversion and Compilation

- Format Conversion: This crucial step is responsible for converting the optimized model from its original training framework (e.g., TensorFlow, PyTorch) or a common interchange format like ONNX [81] into a specific format executable by the target embedded inference engine. For example, TensorFlow Lite Converter [79] generates .tflite files; NCNN [84] uses its conversion toolchain (e.g., onnx2ncnn) to produce its proprietary .param and .bin files; Intel’s OpenVINO [125] creates its optimized Intermediate Representation (IR) format (.xml and .bin files) via the Model Optimizer. Additionally, many hardware vendors’ Software Development Kits (SDKs) also provide conversion tools to adapt models to their proprietary, hardware-acceleration-friendly formats.

- Graph Optimization: Inference frameworks or compilers (e.g., Apache TVM [126]) perform platform-agnostic and platform-specific graph optimizations, such as operator fusion (merging multiple computational layers into a single execution kernel to reduce data movement and function call overhead), constant folding, and layer replacement (substituting standard operators with hardware-supported efficient ones), among others.

- Code Generation: For some frameworks (e.g., TVM) or SDKs targeting specific hardware accelerators (NPUs), this stage generates executable code or libraries highly optimized for the target instruction set (e.g., ARM Neon SIMD, RISC-V Vector Extension) or hardware acceleration units.

6.4. Hardware Integration and Inference Execution

- Integration: Integrating the converted model files (e.g., .tflite files or weights in C/C++ array form) and inference engine libraries (e.g., the core runtime of TensorFlow Lite for MCUs [79], ONNX Runtime Mobile, or specific hardware vendor inference libraries) into the firmware of the embedded project. This typically involves including the corresponding libraries and model data within the embedded development environment (e.g., based on Makefile, CMake, or IDEs like Keil MDK, IAR Embedded Workbench).

- Runtime Environment: The inference engine runs in an embedded operating system (e.g., Zephyr, FreeRTOS, Mbed OS) or a bare-metal environment. It requires allocating necessary memory for it (typically statically allocated to avoid the overhead and uncertainty of dynamic memory management, especially on MCUs [79]).

- Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) Invocation: Application code, by calling APIs provided by the inference engine, completes steps such as model loading, input data preprocessing, inference execution (run() or similar functions), and obtaining output results and post-processing.

- Hardware Accelerator Utilization: If the target platform includes hardware accelerators (e.g., NPUs, GPUs), it is necessary to ensure the inference engine is configured with the correct "delegate" or "execution provider" [83] to offload computationally intensive operations (e.g., convolutions, matrix multiplications) to the hardware accelerator for execution, fully leveraging its performance and power efficiency advantages[117]. This often requires integrating drivers and specialized libraries provided by the hardware vendor (e.g., ARM CMSIS-NN [127] for optimizing operations on ARM Cortex-M).

6.5. Performance Evaluation and Validation

- Key Metrics Measurement: It is necessary to accurately measure the model’s inference latency (time taken for a single inference), throughput (number of inferences processed per unit time), memory footprint (peak RAM and Flash/ROM occupation), and power consumption (Energy per Inference or Average Power).

- Accuracy Validation: Evaluate the accuracy or other task-relevant metrics of the deployed model (after optimization and conversion) on real-world data or representative datasets to ensure it meets application requirements, and compare it with the pre-optimization accuracy to assess whether the accuracy loss due to optimization is within an acceptable range.

- Benchmarking: Standardized benchmarking tools (e.g., MLPerf Tiny [30]) can be run on the target hardware for fair comparison with other implementations or platforms.

- Iterative Optimization: If the evaluation results fail to meet application requirements (e.g., excessive latency, memory overflow, excessive accuracy degradation), it is necessary to return to previous steps for adjustments. This may involve trying different optimization strategies (e.g., adjusting quantization parameters, using different pruning rates), selecting different lightweight models, adjusting model conversion/compilation options, or even redesigning the model architecture or considering a change of hardware platform. This design-optimize-deploy-evaluate cycle may need to be iterated multiple times to achieve the final goal.

7. Applications of EAI

7.1. Autonomous Vehicles

7.2. Smart Sensors and IoT Devices

7.3. Wearable Devices and Healthcare

7.4. Industrial Automation and Robotics

7.5. Consumer Electronics

7.6. Security and Surveillance

7.7. Emerging and Future Applications

8. Challenges and Opportunities

8.1. Challenges

8.1.1. Resource Constraints

8.1.2. Model Optimization

8.1.3. Hardware Acceleration

8.1.4. Security and Privacy

8.1.5. Data Availability

8.2. Opportunities

- Developing novel AI algorithms specifically designed for resource-constrained environments. This includes developing more lightweight and efficient neural network architectures, as well as exploring new ML approaches, such as knowledge-based reasoning and symbolic AI [159]. Both the efficiency and the interpretability of the algorithms should be considered. In some applications, such as medical diagnosis, the decision-making process of AI models needs to be explained for doctors to make judgments. Therefore, there is a need to develop interpretable AI algorithms and research how to integrate knowledge into AI models.

- Exploring new hardware architectures and acceleration technologies. This includes researching novel memory technologies, In-Memory Computing architectures, and developing more efficient specialized AI chips [160]. Photonic Computing is also a potential hardware acceleration technology that uses photons for computation, offering advantages of high speed and low power consumption. Furthermore, Neuromorphic Computing architectures, which mimic the structure and function of the human brain and feature high parallelism and low power consumption, can be investigated.

- Improving the efficiency and robustness of EAI frameworks. This includes developing more efficient compilers, optimizers, and runtime environments, as well as researching new model validation and testing techniques to ensure the reliability and security of EAI systems [122]. There is a need to develop cross-platform EAI frameworks to deploy AI models on different hardware platforms. Additionally, research is needed on how to increase the automation level of EAI frameworks, for example, through automatic model optimization and automatic code generation.

- Addressing the security and privacy challenges associated with EAI deployment. This includes developing new encryption techniques, differential privacy methods, and researching distributed learning methods such as Federated Learning to train AI models while protecting data privacy [161]. Research into hardware security technologies, such as Trusted Execution Environments (TEE), is needed to protect the security of AI models and data. Furthermore, research into Adversarial Attack defense techniques is required to improve the robustness of AI models.

- Developing new applications for EAI across various industries. This includes areas such as smart homes, autonomous driving, healthcare, and industrial automation. EAI is expected to enable more intelligent, efficient, and secure applications in these fields [162]. It is necessary to deeply understand the specific needs of various industries and customize EAI solutions accordingly. Additionally, attention should be paid to emerging application scenarios, such as the Metaverse and Web3.0, where EAI is expected to play a significant role.

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACC | Adaptive Cruise Control |

| ADAS | Advanced Driver-Assistance Systems |

| AEB | Autonomous Emergency Braking |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| AMRs | Autonomous Mobile Robots |

| ASIC | Application-Specific Integrated Circuit |

| BSM | Blind Spot Monitoring |

| CNNs | Convolutional Neural Networks |

| Cobots | Collaborative robots |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| DFCA | Decoupled Fully Connected |

| DRL | Deep Reinforcement Learning |

| EAI | Embedded AI |

| EMG | electromyography |

| FLOPs | Floating point number operations |

| FP16 | 16-bit floating-point |

| FP32 | 32-bit floating-point |

| FPGA | Field-Programmable Gate Array |

| GPU | Graphics Processing Unit |

| GRU | Gated Recurrent Units |

| HPC | High-Performance Computing |

| HRV | heart rate variability |

| IMUs | Inertial Measurement Units |

| INT8 | 8-bit integer |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| IR | Intermediate Representation |

| ISPs | Image Signal Processors |

| KNN | K-Nearest Neighbors |

| KPUs | Knowledge Processing Units |

| LKA | Lane Keeping Assist |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| MCU | Microcontroller Unit |

| ML | machine learning |

| MPU | Micro Processor Unit |

| MQA | Multi-Head Query Attention |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| NAS | Neural Architecture Search |

| NPUs | Neural Processing Units |

| NRE | Non-Recurring Engineering |

| ONNX | Open Neural Network Exchange |

| RAM | Random Access Memory |

| RISC-V | Reduced Instruction Set Computing-V |

| RNNs | Recurrent Neural Networks |

| SDKs | Software Development Kits |

| SIMD | Single Instruction Multiple Datastream |

| SoC | AI System-on-Chip |

| SSD | Single Shot MultiBox Detector |

| SVM | Support Vector Machines |

| TFLite | TensorFlow Lite |

| TPU | Tensor Processing Unit |

| TVM | Tensor Virtual Machine |

| UIB | Universal Inverted Bottleneck |

| ViT | Vision Transformer |

| YOLO | You Only Look Once |

References

- Bengio, Y. Learning Deep Architectures for AI. Foundations and Trends® in Machine Learning 2009, 2, 1–127. [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 2015, 521, 436–444. [CrossRef]

- Silver, D.; Huang, A.; Maddison, C.J.; Guez, A.; Sifre, L.; van den Driessche, G.; Schrittwieser, J.; Antonoglou, I.; Panneershelvam, V.; Lanctot, M.; et al. Mastering the game of Go with deep neural networks and tree search. Nature 2016, 529, 484–489. [CrossRef]

- Heigold, G.; Vanhoucke, V.; Senior, A.; Nguyen, P.; Ranzato, M.; Devin, M.; Dean, J. Multilingual acoustic models using distributed deep neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 26–31 May 2013; pp. 8619–8623. [CrossRef]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Communications of the ACM 2017, 60, 84–90. [CrossRef]

- Satyanarayanan, M. The Emergence of Edge Computing. Computer 2017, 50, 30–39. [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Chang, C.; Yun, K.; Zhang, J. Research on Container Migration Mechanism of Power Edge Computing on Load Balancing. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 6th International Conference on Cloud Computing and Big Data Analytics (ICCCBDA), Chengdu, China, 24-26 April 2021; pp. 386–390. [CrossRef]

- Vermesan, O.; Friess, P.; Guillemin, P.; Sundmaeker, H.; Eisenhauer, M.; Moessner, K.; Le Gall, F.; Cousin, P., Internet of Things Strategic Research and Innovation Agenda. In Internet of Things; River Publishers, 2022; p. 7–151. [CrossRef]

- Moons, B.; Bankman, D.; Verhelst, M., Embedded Deep Neural Networks. In Embedded Deep Learning; Springer International Publishing, 2018; p. 1–31. [CrossRef]

- Warden, P.; Situnayake, D. Tinyml: Machine learning with tensorflow lite on arduino and ultra-low-power microcontrollers; O’Reilly Media, 2019.

- Lane, N.D.; Bhattacharya, S.; Georgiev, P.; Forlivesi, C.; Jiao, L.; Qendro, L.; Kawsar, F. DeepX: A Software Accelerator for Low-Power Deep Learning Inference on Mobile Devices. In Proceedings of the 2016 15th ACM/IEEE International Conference on Information Processing in Sensor Networks (IPSN), Vienna, Austria, 11–14 April 2016; pp. 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Ci, S.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, Y. A survey of energy consumption measurement in embedded systems. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 60516–60530.

- Bonomi, F.; Milito, R.; Zhu, J.; Addepalli, S. Fog computing and its role in the internet of things. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the first edition of the MCC workshop on Mobile cloud computing, Helsinki, Finland, 17 August 2012; pp. 13–16. [CrossRef]

- Madni, A.M.; Sievers, M.; Madni, C.C. Adaptive Cyber-Physical-Human Systems: Exploiting Cognitive Modeling and Machine Learning in the Control Loop. INSIGHT 2018, 21, 87–93. [CrossRef]

- Ray, P.P. A survey of IoT cloud platforms. Future Computing and Informatics Journal 2016, 1, 35–46.

- Shilpa Kodgire, D.; Roopali Palwe, M.; Ganesh Kharde, M., EMBEDDED AI. In Futuristic Trends in Artificial Intelligence Volume 3 Book 12; Iterative International Publishers, Selfypage Developers Pvt Ltd, 2024; p. 137–152. [CrossRef]

- Elkhalik, W.A. AI-Driven Smart Homes: Challenges and Opportunities. Journal of Intelligent Systems and Internet of Things 2023, 8, 54–62. [CrossRef]

- Peccia, F.N.; Bringmann, O. Embedded Distributed Inference of Deep Neural Networks: A Systematic Review. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.03360.

- Zhang, Z.; Li, J. A Review of Artificial Intelligence in Embedded Systems. Micromachines 2023, 14, 897. [CrossRef]

- Kotyal, K.; Nautiyal, P.; Singh, M.; Semwal, A.; Rai, D.; Papnai, G.; Nautiyal, C.T.; G.Malathi.; Krishnaveni, S. Advancements and Challenges in Artificial Intelligence Applications: A Comprehensive Review. Journal of Scientific Research and Reports 2024, 30, 375–385. [CrossRef]

- Serpanos, D.; Ferrari, G.; Nikolakopoulos, G.; Perez, J.; Tauber, M.; Van Baelen, S. Embedded Artificial Intelligence: The ARTEMIS Vision. Computer 2020, 53, 65–69. [CrossRef]

- Dunne, R.; Morris, T.; Harper, S. A Survey of Ambient Intelligence. ACM Computing Surveys 2021, 54, 1–27. [CrossRef]

- Sannasy Rao, K.; Lean, C.P.; Ng, P.K.; Kong, F.Y.; Basir Khan, M.R.; Ismail, D.; Li, C. AI and ML in IR4.0: A Short Review of Applications and Challenges. Malaysian Journal of Science and Advanced Technology 2024, p. 141–148. [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.A. Cyber Physical Systems: Design Challenges. In Proceedings of the 2008 11th IEEE International Symposium on Object and Component-Oriented Real-Time Distributed Computing (ISORC), Orlando, Florida, USA, 5–7 May 2008; pp. 363–369. [CrossRef]

- Marwedel, P. Embedded System Design; Springer International Publishing, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.Y. Embedded Artificial Intelligence: Intelligence on Devices. Computer 2023, 56, 90–93. [CrossRef]

- Sze, V.; Chen, Y.H.; Yang, T.J.; Emer, J.S. Efficient Processing of Deep Neural Networks: A Tutorial and Survey. Proceedings of the IEEE 2017, 105, 2295–2329. [CrossRef]

- Yiu, J., Introduction to ARM® Cortex®-M Processors. In The Definitive Guide to ARM® CORTEX®-M3 and CORTEX®-M4 Processors; Elsevier, 2014; p. 1–24. [CrossRef]

- Ray, P.P. A review on TinyML: State-of-the-art and prospects. Journal of King Saud University-Computer and Information Sciences 2022, 34, 1595–1623.

- Mattson, P.; Reddi, V.J.; Cheng, C.; Coleman, C.; Diamos, G.; Kanter, D.; Micikevicius, P.; Patterson, D.; Schmuelling, G.; Tang, H.; et al. MLPerf: An Industry Standard Benchmark Suite for Machine Learning Performance. IEEE Micro 2020, 40, 8–16. [CrossRef]

- Shankar, V. Edge AI: A Comprehensive Survey of Technologies, Applications, and Challenges. In Proceedings of the 2024 1st International Conference on Advanced Computing and Emerging Technologies (ACET), Ghaziabad, India, 23–24 August 2024; pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- STMicroelectronics. STM32Cube.AI-STMicroelectronics-STM32 AI, 2023. (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- NXP. i.MX RT Crossover MCUs, 2024. (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- ESP-DL. ESP-DL Introduction, 2023. (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Ibrahim, D., Architecture of ARM microcontrollers. In Arm-Based Microcontroller Multitasking Projects; Elsevier, 2021; p. 13–32. [CrossRef]

- Murshed, M.G.S.; Murphy, C.; Hou, D.; Khan, N.; Ananthanarayanan, G.; Hussain, F. Machine Learning at the Network Edge: A Survey. ACM Computing Surveys 2021, 54, 1–37. [CrossRef]

- ARM. Key architectural points of ARM Cortex-A series processors, 2023. (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Zamojski, P.; Elfouly, R. Developing Standardized SIMD API Between Intel and ARM NEON. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Computational Science and Computational Intelligence (CSCI), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 12–14 December 2018; pp. 1410–1415. [CrossRef]

- Mediatek. MediaTek | Filogic 830 | Premium Wi-Fi 6/6E SoC, 2023. (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Raspberry Pi Ltd. raspberry-pi-5-product-brief. (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Intel. What Is a GPU?, 2023. (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Janai, J.; Güney, F.; Behl, A.; Geiger, A. Computer Vision for Autonomous Vehicles: Problems, Datasets and State of the Art. Foundations and Trends® in Computer Graphics and Vision 2020, 12, 1–308. [CrossRef]

- Badue, C.; Guidolini, R.; Carneiro, R.V.; Azevedo, P.; Cardoso, V.B.; Forechi, A.; Jesus, L.; Berriel, R.; Paixão, T.M.; Mutz, F.; et al. Self-driving cars: A survey. Expert Systems with Applications 2021, 165, 113816. [CrossRef]

- NVIDIA. NVIDIA Jetson Orin, 2025. (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Kurniawan, A., Administering NVIDIA Jetson Nano. In IoT Projects with NVIDIA Jetson Nano; Apress, 2020; p. 21–47. [CrossRef]

- NVIDIA. Jetson Developer Kits, 2025. (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Ashbaugh, B.; Lake, A.; Rovatsou, M. Khronos™ group. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 3rd International Workshop on OpenCL (IWOCL ’15), New York , United States, 12–13 May 2015; pp. 1–23. [CrossRef]

- Pipes, M.A. Qualcomm snapdragon “bullet train”. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGGRAPH 2015 Computer Animation Festival. ACM, 2015, SIGGRAPH ’15, p. 124–125. [CrossRef]

- MediaTek. MediaTek | Dimensity | 5G Smartphone Chips, n.d. (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Wang, T.; Wang, C.; Zhou, X.; Chen, H. A survey of FPGA based deep learning accelerators: Challenges and opportunities. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1901.04988.

- Cheremisinov, D.I. Protecting intellectual property in FPGA Xilinx design. Prikladnaya diskretnaya matematika 2014, p. 110–118. [CrossRef]

- Limited, A.E. AC7Z020 SoM with AMD Zynq™ 7000 SoC XC7Z020, 2023. (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Intel. Arria® 10 FPGA and SoC FPGA, 2023. (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Lattice Semiconductor. iCE40 LP/HX, 2025. (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Microchip. SmartFusion® 2 FPGAs, 2025. (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Reuther, A.; Michaleas, P.; Jones, M.; Gadepally, V.; Samsi, S.; Kepner, J. Survey of Machine Learning Accelerators. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE High Performance Extreme Computing Conference (HPEC). Waltham, Massachusetts, USA, 22–24 September 2020; pp. 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Jouppi, N.; Young, C.; Patil, N.; Patterson, D. Motivation for and Evaluation of the First Tensor Processing Unit. IEEE Micro 2018, 38, 10–19. [CrossRef]

- Google LLC. USB Accelerator datasheet, 2025. (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- cambricon. MLU220-SOM, 2025. (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Huawei. Atlas 200I DK A2 Developer Kit, 2025. (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Xiao, Y.; Wang, Z. AIbench: a tool for benchmarking Huawei ascend AI processors. CCF Transactions on High Performance Computing 2024, 6, 115–129. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.H.; Krishna, T.; Emer, J.S.; Sze, V. Eyeriss: An Energy-Efficient Reconfigurable Accelerator for Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. IEEE Journal of Solid-State Circuits 2017, 52, 127–138. [CrossRef]

- Kung, H.T.; Leiserson, C.E. Systolic arrays (for VLSI). In Proceedings of the Sparse Matrix Proceedings 1978. Society for industrial and applied mathematics Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1979; pp. 256–282.

- Shafiee, A.; Nag, A.; Muralimanohar, N.; Balasubramonian, R.; Strachan, J.P.; Hu, M.; Williams, R.S.; Srikumar, V. ISAAC: a convolutional neural network accelerator with in-situ analog arithmetic in crossbars. ACM SIGARCH Computer Architecture News 2016, 44, 14–26. [CrossRef]

- Horizon Robotics. RDK X3 Robot Development Kit, 2023. (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Rockchip Electronics Co., L. Rockchip RV11 Series, 2023. (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Kendryte. Kendryte Developer Community-Product Center, n.d. (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Axera Semiconductor. AX650N, 2025. (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Bavikadi, S.; Dhavlle, A.; Ganguly, A.; Haridass, A.; Hendy, H.; Merkel, C.; Reddi, V.J.; Sutradhar, P.R.; Joseph, A.; Pudukotai Dinakarrao, S.M. A Survey on Machine Learning Accelerators and Evolutionary Hardware Platforms. IEEE Design & Test 2022, 39, 91–116. [CrossRef]

- Benmeziane, H.; Maghraoui, K.E.; Ouarnoughi, H.; Niar, S.; Wistuba, M.; Wang, N. A comprehensive survey on hardware-aware neural architecture search. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2101.09336.

- Gerla, M.; Lee, E.K.; Pau, G.; Lee, U. Internet of vehicles: From intelligent grid to autonomous cars and vehicular clouds. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE World Forum on Internet of Things (WF-IoT), Seoul, Korea, 6–8 March 2014; pp. 241-246. [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Liu, X.; Mao, H.; Pu, J.; Pedram, A.; Horowitz, M.; Dally, B. Deep compression and EIE: Efficient inference engine on compressed deep neural network. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Hot Chips 28 Symposium (HCS), Cupertino, CA, USA, 21–23 August 2016; pp.1–6 . [CrossRef]

- Blaiech, A.G.; Ben Khalifa, K.; Valderrama, C.; Fernandes, M.A.; Bedoui, M.H. A Survey and Taxonomy of FPGA-based Deep Learning Accelerators. Journal of Systems Architecture 2019, 98, 331–345. [CrossRef]

- Presutto, M. Current AI Trends: Hardware and Software Accelerators. Royal Institute of Technology 2018, pp. 1–21.

- Ott, P.; Speck, C.; Matenaer, G., Deep end-to-end Learning im Automotivebereich /Deep end-to-end learning in automotive. In ELIV 2017; VDI Verlag, 2017; p. 49–50. [CrossRef]

- Colucci, A.; Marchisio, A.; Bussolino, B.; Mrazek, V.; Martina, M.; Masera, G.; Shafique, M. A fast design space exploration framework for the deep learning accelerators: Work-in-progress. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Hardware/Software Codesign and System Synthesis (CODES+ ISSS), Shanghai, China, 9 November 2020; pp. 34–36.

- Jacob, B.; Kligys, S.; Chen, B.; Zhu, M.; Tang, M.; Howard, A.; Adam, H.; Kalenichenko, D. Quantization and Training of Neural Networks for Efficient Integer-Arithmetic-Only Inference. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 2704–2713. [CrossRef]

- Banbury, C.R.; Reddi, V.J.; Lam, M.; Fu, W.; Fazel, A.; Holleman, J.; Huang, X.; Hurtado, R.; Kanter, D.; Lokhmotov, A.; et al. Benchmarking tinyml systems: Challenges and direction. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2003.04821.

- Zaman, F. TensorFlow Lite for Mobile Development: Deploy Machine Learning Models on Embedded and Mobile Devices; Apress, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Alla, S.; Adari, S.K., Introduction to Deep Learning. In Beginning Anomaly Detection Using Python-Based Deep Learning; Apress, 2019; p. 73–122. [CrossRef]

- Microsoft Corporation. ONNX, n.d. (accessed on 7 June 2025).

- Ltd., A. Arm NN SDK - Efficient ML for Arm CPUs, GPUs, NPUs, 2023. (accessed on 7 June 2025).

- ARM-software. GitHub - ARM-software/CMSIS-NN: CMSIS-NN Library, 2023. (accessed on 7 June 2025).

- Ni, H.; The ncnn contributors. ncnn, 2017. (accessed on 7 June 2025).

- Chen, T.; Moreau, T.; Jiang, Z.; Shen, H.; Yan, E.Q.; Wang, L.; Hu, Y.; Ceze, L.; Guestrin, C.; Krishnamurthy, A. TVM: end-to-end optimization stack for deep learning. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1802.04799, 11, 20.

- Lugaresi, C.; Tang, J.; Nash, H.; McClanahan, C.; Uboweja, E.; Hays, M.; Zhang, F.; Chang, C.L.; Yong, M.G.; Lee, J.; et al. Mediapipe: A framework for building perception pipelines. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1906.08172.

- mit-han-lab. Tiny Machine Learning[website], 2024. (accessed on 7 June 2025).

- Sanchez-Iborra, R.; Skarmeta, A.F. TinyML-Enabled Frugal Smart Objects: Challenges and Opportunities. IEEE Circuits and Systems Magazine 2020, 20, 4–18. [CrossRef]

- Shafique, M.; Theocharides, T.; Reddy, V.J.; Murmann, B. TinyML: Current Progress, Research Challenges, and Future Roadmap. In Proceedings of the 2021 58th ACM/IEEE Design Automation Conference (DAC), San Francisco, CA, USA, 5–9 December 2021; pp. 1303-1306 . [CrossRef]

- uTensor. uTensor - TinyML AI Inference Library, 2023.

- jczic. GitHub - jczic/MicroMLP: A micro neural network multilayer perceptron for MicroPython (used on ESP32 and Pycom modules), n.d.

- Edgeimpulse, Inc. The Edge AI Platform, 2025. (accessed on 7 June 2025).

- SensiML. SensiML - Making Sensor Data Sensible, 2020. (accessed on 7 June 2025).

- Quinlan, J.R. Induction of decision trees. Machine Learning 1986, 1, 81–106. [CrossRef]

- Cortes, C.; Vapnik, V. Support-vector networks. Machine Learning 1995, 20, 273–297. [CrossRef]

- Cover, T.; Hart, P. Nearest neighbor pattern classification. IEEE Transactions on Information Theory 1967, 13, 21–27. [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, T.; De, D.; Sharma, P.; Sengupta, D. Empirical Copula based Naive Bayes Classifier. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Knowledge Discovery in Concurrent Engineering (ICECONF), Chennai, India, 5-7 January 2023; pP. 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Machine learning 2001, 45, 5–32.

- Lecun, Y.; Bottou, L.; Bengio, Y.; Haffner, P. Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition. Proceedings of the IEEE 1998, 86, 2278–2324. [CrossRef]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1409.1556.

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [CrossRef]

- Szegedy, C.; Liu, W.; Jia, Y.; Sermanet, P.; Reed, S.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Vanhoucke, V.; Rabinovich, A. Going deeper with convolutions. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June, 2015; pp. 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long Short-Term Memory. Neural Computation 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [CrossRef]

- Cho, K.; Van Merriënboer, B.; Gulcehre, C.; Bahdanau, D.; Bougares, F.; Schwenk, H.; Bengio, Y. Learning phrase representations using RNN encoder-decoder for statistical machine translation. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1406.1078.

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, .; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. Advances in neural information processing systems 2017, 30.

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.11929.

- LeCun, Y.; Denker, J.; Solla, S. Optimal brain damage. Advances in neural information processing systems 1989, 2.

- Hinton, G.; Vinyals, O.; Dean, J. Distilling the knowledge in a neural network. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1503.02531.

- Howard, A.G.; Zhu, M.; Chen, B.; Kalenichenko, D.; Wang, W.; Weyand, T.; Andreetto, M.; Adam, H. Mobilenets: Efficient convolutional neural networks for mobile vision applications. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1704.04861.

- Sandler, M.; Howard, A.; Zhu, M.; Zhmoginov, A.; Chen, L.C. MobileNetV2: Inverted Residuals and Linear Bottlenecks. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18-23 June 2018; pp. 4510–4520. [CrossRef]

- Howard, A.; Sandler, M.; Chen, B.; Wang, W.; Chen, L.C.; Tan, M.; Chu, G.; Vasudevan, V.; Zhu, Y.; Pang, R.; et al. Searching for MobileNetV3. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, Korea, 27 October 2019 to 2 November 2019; pp. 1314–1324. [CrossRef]

- Qin, D.; Leichner, C.; Delakis, M.; Fornoni, M.; Luo, S.; Yang, F.; Wang, W.; Banbury, C.; Ye, C.; Akin, B.; et al., MobileNetV4: Universal Models for the Mobile Ecosystem. In Computer Vision – ECCV 2024; Springer Nature Switzerland, 2024; p. 78–96. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhou, X.; Lin, M.; Sun, J. ShuffleNet: An Extremely Efficient Convolutional Neural Network for Mobile Devices. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18-23 June 2018; pp. 6848-6856. [CrossRef]

- Ma, N.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, H.T.; Sun, J., ShuffleNet V2: Practical Guidelines for Efficient CNN Architecture Design. In Computer Vision – ECCV 2018; Springer International Publishing, 2018; p. 122–138. [CrossRef]

- Iandola, F.N.; Han, S.; Moskewicz, a.W.; Ashraf, K.; Dally, W.J.; Keutzer, K. SqueezeNet: AlexNet-level accuracy with 50x fewer parameters and< 0.5 MB model size. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1602.07360.

- Tan, M.; Le, Q. Efficientnet: Rethinking model scaling for convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning, Long Beach, California, USA, 9-15 June 2019; pp. 6105–6114.

- Tan, M.; Le, Q. Efficientnetv2: Smaller models and faster training. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning, Virtual, 18-24 July 2021; pp. 10096–10106.

- Han, K.; Wang, Y.; Tian, Q.; Guo, J.; Xu, C.; Xu, C. GhostNet: More Features From Cheap Operations. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13-19 June 2020; pp. 1577–1586. [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Han, K.; Guo, J.; Xu, C.; Xu, C.; Wang, Y. GhostNetv2: Enhance cheap operation with long-range attention. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2022, 35, 9969–9982.

- Liu, Z.; Hao, Z.; Han, K.; Tang, Y.; Wang, Y. Ghostnetv3: Exploring the training strategies for compact models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.11202.

- Mehta, S.; Rastegari, M. Mobilevit: light-weight, general-purpose, and mobile-friendly vision transformer. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2110.02178.

- Babu, R.G.; Nedumaran, A.; Manikandan, G.; Selvameena, R., TensorFlow: Machine Learning Using Heterogeneous Edge on Distributed Systems. In Deep Learning in Visual Computing and Signal Processing; Apple Academic Press, 2022; p. 71–90. [CrossRef]

- Liang, T.; Glossner, J.; Wang, L.; Shi, S.; Zhang, X. Pruning and quantization for deep neural network acceleration: A survey. Neurocomputing 2021, 461, 370–403.

- Gholami, A.; Kim, S.; Dong, Z.; Yao, Z.; Mahoney, M.W.; Keutzer, K., A Survey of Quantization Methods for Efficient Neural Network Inference. In Low-Power Computer Vision; Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2022; p. 291–326. [CrossRef]

- Vasudevan, S.K.; Pulari, S.R.; Vasudevan, S., Intel OpenVino: A Must-Know Deep Learning Toolkit. In Deep Learning; Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2021; p. 245–260. [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Moreau, T.; Jiang, Z.; Shen, H.; Yan, E.Q.; Wang, L.; Hu, Y.; Ceze, L.; Guestrin, C.; Krishnamurthy, A. TVM: end-to-end optimization stack for deep learning. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1802.04799, 11, 20.

- Lai, L.; Suda, N.; Chandra, V. Cmsis-nn: Efficient neural network kernels for arm cortex-m cpus. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1801.06601.

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You Only Look Once: Unified, Real-Time Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27-30 June 2016; pp. 779–788. [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Szegedy, C.; Reed, S.; Fu, C.Y.; Berg, A.C., SSD: Single Shot MultiBox Detector. In Computer Vision – ECCV 2016; Springer International Publishing, 2016; p. 21–37. [CrossRef]

- Grigorescu, S.; Trasnea, B.; Cocias, T.; Macesanu, G. A survey of deep learning techniques for autonomous driving. Journal of Field Robotics 2019, 37, 362–386. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Wang, Z.; Yang, H.; Yang, L. Artificial intelligence applications in the development of autonomous vehicles: A survey. IEEE/CAA Journal of Automatica Sinica 2020, 7, 315–329.

- Kim, M.; Lee, S.; Ha, J.; Lee, H. Make Your Autonomous Mobile Robot on the Sidewalk Using the Open-Source LiDAR SLAM and Autoware. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Vehicles 2024.

- Shi, W.; Cao, J.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Y.; Xu, L. Edge Computing: Vision and Challenges. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2016, 3, 637–646. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Yan, R.; Chen, Z.; Mao, K.; Wang, P.; Gao, R.X. Deep learning and its applications to machine health monitoring. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 2019, 115, 213–237. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, H.; Haque, A.; Blaabjerg, F. Machine learning in wireless sensor networks for smart cities: a survey. Electronics 2021, 10, 1012.

- Kamilaris, A.; Prenafeta-Boldú, F.X. Deep learning in agriculture: A survey. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2018, 147, 70–90. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Hong, T.; Piette, M.A. Building thermal load prediction through shallow machine learning and deep learning. Applied Energy 2020, 263, 114683. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chen, Y.; Hao, S.; Peng, X.; Hu, L. Deep learning for sensor-based activity recognition: A survey. Pattern Recognition Letters 2019, 119, 3–11. [CrossRef]

- Majumder, S.; Deen, M.J. Smartphone Sensors for Health Monitoring and Diagnosis. Sensors 2019, 19, 2164. [CrossRef]

- Esteva, A.; Kuprel, B.; Novoa, R.A.; Ko, J.; Swetter, S.M.; Blau, H.M.; Thrun, S. Dermatologist-level classification of skin cancer with deep neural networks. Nature 2017, 542, 115–118. [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Qi, W.; Li, Z.; Chen, Z.; Ferrigno, G.; De Momi, E. Deep neural network approach in EMG-based force estimation for human–robot interaction. IEEE Transactions on Artificial Intelligence 2021, 2, 404–412.

- Villani, V.; Pini, F.; Leali, F.; Secchi, C. Survey on human–robot collaboration in industrial settings: Safety, intuitive interfaces and applications. Mechatronics 2018, 55, 248–266. [CrossRef]

- Weimer, D.; Scholz-Reiter, B.; Shpitalni, M. Design of deep convolutional neural network architectures for automated feature extraction in industrial inspection. CIRP Annals 2016, 65, 417–420. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Bagheri, B.; Kao, H.A. A Cyber-Physical Systems architecture for Industry 4.0-based manufacturing systems. Manufacturing Letters 2015, 3, 18–23. [CrossRef]

- Bogue, R. Robots in the laboratory: a review of applications. Industrial Robot: An International Journal 2012, 39, 113–119. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.C.; Papandreou, G.; Kokkinos, I.; Murphy, K.; Yuille, A.L. DeepLab: Semantic Image Segmentation with Deep Convolutional Nets, Atrous Convolution, and Fully Connected CRFs. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2018, 40, 834–848. [CrossRef]

- Shan, C.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Xie, L. Attention-Based End-to-End Speech Recognition on Voice Search. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Calgary, AB, Canad, 15-20 April 2018; pp. 4764–4768. [CrossRef]

- Carrio, A.; Sampedro, C.; Rodriguez-Ramos, A.; Campoy, P. A Review of Deep Learning Methods and Applications for Unmanned Aerial Vehicles. Journal of Sensors 2017, 2017, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Ulku, I.; Akagündüz, E. A Survey on Deep Learning-based Architectures for Semantic Segmentation on 2D Images. Applied Artificial Intelligence 2022, 36. [CrossRef]

- Ramachandra, B.; Jones, M.J.; Vatsavai, R.R. A survey of single-scene video anomaly detection. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 2020, 44, 2293–2312.

- Park, J.; Samarakoon, S.; Bennis, M.; Debbah, M. Wireless Network Intelligence at the Edge. Proceedings of the IEEE 2019, 107, 2204–2239. [CrossRef]

- Vilela, M.; Hochberg, L.R. Applications of brain-computer interfaces to the control of robotic and prosthetic arms. Handbook of clinical neurology 2020, 168, 87–99.

- Ouyang, F.; Jiao, P. Artificial intelligence in education: The three paradigms. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence 2021, 2, 100020. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Han, Y.; Leung, V.C.; Niyato, D.; Yan, X.; Chen, X. Convergence of edge computing and deep learning: A comprehensive survey. IEEE communications surveys & tutorials 2020, 22, 869–904.

- Owens, J.; Houston, M.; Luebke, D.; Green, S.; Stone, J.; Phillips, J. GPU Computing. Proceedings of the IEEE 2008, 96, 879–899. [CrossRef]

- Papernot, N.; McDaniel, P.; Goodfellow, I.; Jha, S.; Celik, Z.B.; Swami, A. Practical Black-Box Attacks against Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2017 ACM on Asia Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Abu Dhabi United Arab Emirates, 2–6 April 2017; pp. 506–519. [CrossRef]

- Dwork, C. Differential privacy: A survey of results. In Proceedings of the International conference on theory and applications of models of computation, Xi’an, China, 25–29 April 2008; pp. 1–19.

- Wang, Y.; Yao, Q.; Kwok, J.T.; Ni, L.M. Generalizing from a Few Examples: A Survey on Few-shot Learning. ACM Computing Surveys 2020, 53, 1–34. [CrossRef]

- Marcus, G. The next decade in AI: four steps towards robust artificial intelligence. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2002.06177.

- Sebastian, A.; Le Gallo, M.; Khaddam-Aljameh, R.; Eleftheriou, E. Memory devices and applications for in-memory computing. Nature Nanotechnology 2020, 15, 529–544. [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Sahu, A.K.; Talwalkar, A.; Smith, V. Federated Learning: Challenges, Methods, and Future Directions. IEEE Signal Processing Magazine 2020, 37, 50–60. [CrossRef]

- Vermesan, O.; Friess, P.; Guillemin, P.; Sundmaeker, H.; Eisenhauer, M.; Moessner, K.; Le Gall, F.; Cousin, P., Internet of Things Strategic Research and Innovation Agenda. In Internet of Things; River Publishers, 2022; p. 7–151. [CrossRef]

| Platforms models1 | Manu-facturer | Arch-itecture | Processor | AI Accelerator | Computational Power | Power Consumption2 | Other Key Features |

| STM32F [32] | ST Microelectronics | MCU | Cortex-M0/M3/M4/ M7/M33 etc. | ART Accelerator/NPU (e.g., STM32U5, H7 with NPU) in some models | Tens to hundreds of DMIPS3, several GOPS4 in some models (with NPU) | Low power (mA-level op., µA-level standby) | Rich peripherals, CubeMX ecosystem, Security features (integrated in some models) |

| i.MX RT [33] | NXP | MCU | Cortex-M7, Cortex-M33 | 2D GPU (PXP), NPU (e.g., RT106F, RT117F) in some models | Hundreds to thousands of DMIPS, NPU can reach 1-2 TOPS | Medium power, performance-oriented | High-performance real-time processing, MIPI interface, LCD interface control, EdgeLock security subsystem |

| ESP32-S3 [34] | Espressif | MCU | Xtensa LX6/LX7 (dual-core), RISC-V | Supports AI Vector Instructions | CPU: Up to 960 DMIPS; AI: Approx. 0.3-0.4 TOPS (8-bit integer, INT8) | Low power (higher when Wi-Fi/BT active) | Integrated Wi-Fi and Bluetooth, Open-source SDK (ESP-IDF), Active community, High cost-performance |

| STM32-MP13x [35,36,37,38] | ST Microelectronics | MPU | ARM Cortex-A7, Cortex-M4 | No dedicated GPU; AI runs via CPU/CMSIS-NN | A7: Max ∼2000 DMIPS; M4: Max ∼200 DMIPS | <1W | Entry-level Linux or RTOS system design |

| MT7986A (Filogic 830) [39] | MediaTek | MPU | ARM Cortex-A53 | Hardware Network Acceleration Engine, AI Engine (NPU, approx. 0.5 TOPS) | CPU: Up to ∼16000 DMIPS | ∼7.5W | High-speed network interface |

| Raspberry Pi 5 [40] | Raspberry Pi | MPU | Broadcom BCM2712 (quad-core ARM Cortex-A76) | VideoCore VII GPU | ∼60-80 GFLOPS5 | Passive Cooling; 2.55W (Idle); 6.66W (Stress)6 | Graphics performance and general-purpose computing capability |

| Jetson Orin NX [44]7 | NVIDIA | GPU | ARM Cortex-A78AE | NVIDIA Ampere GPU, Tensor Cores | 100.0 TOPS (16GB ver.), 70.0 TOPS (8GB ver.) | 10-25W | CUDA, TensorRT |

| Jetson Nano [45] | NVIDIA | GPU | ARM Cortex-A57, NVIDIA Maxwell GPU | NVIDIA Maxwell GPU | 0.472 TFLOPs (16-bit floating-point, FP16) / 5 TOPS (INT8, sparse) | 5-10W (typically) | CUDA, TensorRT |

| Zynq 7000 [52] | AMD (Xilinx) | FPGA | Dual-core Arm Cortex-A9 MPCore | Programmable Logic (PL) for custom accelerators | PS (A9): Max ∼5000 DMIPS | Low power (depends on design and load) | Highly customizable hardware, Real-time processing capability |

| Arria 10 [53] | Intel (Altera) | FPGA | Dual-core Arm Cortex-A9 (SoC versions) | FPGA fabric for custom accelerators | SoC (A9): Max ∼7500 DMIPS | Low power (depends on design and load) | Enhanced FPGA and Digital Signal Processing (DSP) capabilities |

| iCE40HX1K [54] | Lattice | FPGA | iCE40 LM (FPGA family) | FPGA fabric for custom accelerators | 1280 Logic Cells | Very low power | Small form factor, Low power consumption |

| Smart Fusion2 [55] | Microchip | FPGA | ARM Cortex-M3 | FPGA fabric for custom accelerators | MCU (M3): ∼200 DMIPS | Low power | Secure, high-performance for comms, industrial interface, automotive markets |

| Google Tensor G3 [57] | ASIC | 1x Cortex-X3, 4x Cortex-A715 , 4x Cortex-A510 | Mali-G715 GPU | N/A (High-end mobile SoC performance) | N/A (Mobile SoC) | Emphasizes AI functions and image processing | |

| Coral USB Accelerator [58] | ASIC | ARM 32-bit Cortex-M0+ Microprocessor (controller) | Edge TPU | 4.0 TOPS (INT8) | 2.0W | USB interface, Plug-and-play | |

| MLU220-SOM [59] | Cambricon | ASIC | 4x ARM Cortex-A55 | Cambricon MLU (Memory Logic Unit) NPU | 16.0 TOPS (INT8) | 15W | Edge intelligent SoC module |

| Atlas 200I DK A2 [60,61] | Huawei | ASIC | 4 core @ 1.0 GHz | Ascend AI Processor | 8.0 TOPS (INT8), 4.0 TOPS (FP16) | 24W | Software and hardware development kit |

| RDK X3 Module [65] | Horizon Robotics | AI SoC | ARM Cortex-A53 (Application Processors) | Dual-core Bernoulli BPU | 5.0 TOPS | 10W | Optimized for visual processing |

| RK3588 [66] | Rockchip | AI SoC | 4x Cortex-A76 + 4x Cortex-A55 | ARM Mali-G610 MC4, NPU | NPU: 6.0 TOPS | ∼8.04W | Supports multi-camera input |

| RV1126 [66] | Rockchip | AI SoC | ARM Cortex-A7, RISC-V MCU | NPU | 2.0 TOPS (NPU) | 1.5W | Low power, Optimized for visual processing |

| K230 [67] | Kendryte (Canmv) | AI SoC | 2x C908 (RISC-V), RISC-V MCU | NPU | 1.0 TOPS (NPU) | 2.0W | Low power, Supports TinyML |

| AX650N [68] | Axera Semiconductor | AI SoC | ARM Cortex-A55 | NPU | 72.0 TOPS (INT4), 18.0 TOPS (INT8) | 8.0W | Video encoding/decoding, Image processing |

| Framework Name | Vendor | Supported Hardware | Development Languages | Use Cases |

| TensorFlow Lite [79] | iOS, Linux, Microcontrollers, Edge TPU, GPU, DSP, CPU | C++, Python, Java, Swift | Image recognition, Speech recognition, Natural language processing, Sensor data analysis | |

| PyTorch Mobile [80] | Meta (Facebook) | Android, iOS, Linux, CPU | Java, Objective-C, C++ | Image recognition, Speech recognition, Natural language processing |

| ONNX Runtime [81] | Microsoft (and Community/Partners) | CPU, GPU, Dedicated Accelerators (Intel OpenVINO, NVIDIA TensorRT) | C++, C#, Python, JavaScript, Java | Various ML tasks, Model deployment |

| Arm NN [82] | Arm | Arm Cortex-A, Arm Cortex-M, Arm Ethos-NPU | C++ | Image recognition, Speech recognition, Natural language processing, Efficient inference on Arm devices |

| CMSIS-NN [83] | Arm | ARM Cortex-M | C | Neural network programming for resource-constrained embedded systems |

| NCNN [84] | Tencent | Android, iOS | C++ | Image recognition, Object detection, Face recognition, Mobile AI applications |

| TVM [85] | Apache (from UW) | CPU, GPU, FPGA, Dedicated Accelerators (e.g., VTA) | C++, Rust, Java | Various ML tasks, Model deployment, Especially for optimizing for heterogeneous hardware |

| MediaPipe [86] | Android, iOS, Linux, Web | C++, Python, JavaScript | Real-time media processing, Face detection, Pose estimation, Object tracking | |

| TinyML [87,88,89] | N/A (Domain/Concept/ Community) | Microcontrollers (ARM Cortex-M, RISC-V), Sensors | C, C++, Java | Sensor data analysis, Anomaly detection, Voice activation |

| uTensor [90] | Open Source (formerly part of MemryX) | Microcontrollers (ARM Cortex-M) | C++ | Sensor data analysis, Simple control tasks |

| MicroMLP [91] | N/A (Concept/Specific library) | Ultra-low-power microcontrollers | C | Simple classification tasks, Gesture recognition |

| Edge Impulse [92] | Edge Impulse (Company) | Microcontrollers, Linux devices, Sensors | C++, Python , JavaScript | Various embedded ML applications, especially for scenarios requiring rapid prototyping and deployment |

| SensiML [93] | SensiML (a QuickLogic company) | Microcontrollers, Sensors | C++, Python | Various embedded ML applications, especially for sensor data analysis requiring low power and high efficiency |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).