1. Introduction

The notion of time to some event, for example, death, progression, or recovery from disease, is fundamental to medical and clinical research. These studies can more commonly be classified as studies of time-to-event data, in which the main interest is how long it takes for an event to occur. Two prevalent statistical approaches that have sought to deal with this type of data are life tables and survival analysis. These methods are particularly helpful when not all subjects in the study experience the event of interest during the study period, resulting in censored cases [

1,

2,

3].

A case is considered censored if the outcome of interest has not been observed until the time of the study [

4]. This may be the case when the subject is alive after the study or withdraws for reasons that are unrelated to the event of interest. These scenarios run into issues with common statistical methods like t-tests or linear regression that assume a complete data set for their cases. To accommodate this problem, Lifetables and the Kaplan-Meier technique for the analysis of survival have been developed, which are useful tools to handle “censored” data and yield valid point estimates of survival proportions at specified points in time [

5,

6,

7,

8].

Life tables discretize the observation period into small time intervals and estimate the probability of experiencing the event in each time interval [

9,

10]. These are assumed to be intervals in which the probability of an event occurring at any given point within the interval is assumed to be constant among those living in that interval [

11]. Conversely, the non-parametric Kaplan-Meier survival analysis does not assume a constant probability of events within time intervals and thus estimates the survival function. This technique is especially useful in cases of smaller sample sizes and sparse data points [

12,

13].

The purpose of this paper is to touch on the theory and applications of the life table and the Kaplan-Meier survival figure, along with points of interest in their use in medicine [

14]. We will see how these techniques lend themselves to estimates of survival probabilities and hazard rates as well as comparisons of treatment or patient sub-groups. In addition, we are going to show how these techniques can be applied using SPSS software as a practical tool for data analysis [

15,

16,

17,

18].

Life tables and Kaplan-Meier analysis allow physicians to determine treatment as well as prognosis. These methods enable a more explicit interpretation of survival patterns, which in turn assist physicians and clinicians in determining optimal care for patients [

19,

20]. Life tables, which display survival of patients on different treatments, and Kaplan-Meier survival curves that graphically depict survival probabilities and lend themselves more readily to comparisons between groups, for instance, are examples of these techniques [

21].

Such analyses can only take place in medicine, for instance, in clinical trials where an experiment is conducted to verify the efficacy of a novel treatment or medication. Similarly, in the study of cancer, life tables and the Kaplan-Meier analyses are utilized to assess the efficacy of a new chemotherapy treatment by ascertaining whether patients on the experimental treatment survive longer than patients on conventional chemotherapy [

22,

23]. Though these may also serve in the assessment of the influence of additional factors such as age, gender, or comorbidities on survival.

Important assumptions of these kinds of statistics will also be covered here, such as the proportional hazard assumption of the Kaplan-Meier analyses and the independence of censoring, and the event. It will discuss how these assumptions affect the analysis and later provide a set of recommendations for “good” survival analysis [

24,

25].

4. Application

To compare two groups of (20) patients with a brain tumor, one of them received treatment A (Group 1) or conventional medication, while the second group received treatment B (Group 2) the new medication through the formation of a life table (Life Table) for a period measured in weeks and the event is the death of the Patient (1) while his survival (0).

The life schedule is analyzed in some steps. We get

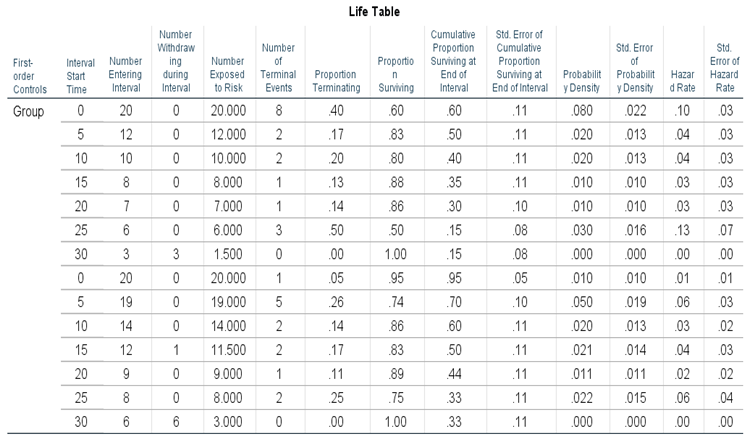

Table 1 results.

A life schedule is a descriptive table that summarizes the time it takes for an event to occur. The table is divided by each group (here we have two groups), including the period (0-30) as determined by the highest value (30), which has a Category length of 5. Then, determine the number of entrants in the corresponding period. Or the number of surviving cases at the beginning of the period. This value decreases steadily with each period as people who have died and for both groups. Here we have (20) people for the first group at the beginning of the study, of whom (8) died for the period from zero to less than (5) and of whom (12) survived, while one person from the second group, which reached (20) people also died, of whom (19) people remained, and so on, the rest of the values reach (3) survivors for the first group and(6) for the second group at the end of the study (30).

And determine the number of controlled cases in this period. These are still alive, but so far they have not existed longer than the indicated period in period. And here, there is only one person who survived outside the study for the period (15-20).

The table also shows that the greatest number and percentage of terminal events occurred during the first period (for the first group), with the highest risk rate, which indicates that patients should be closely monitored during the first period of the first group for their safety.

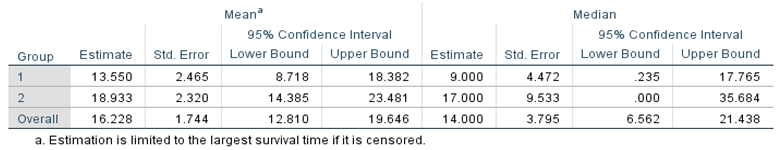

The median survival time (in

Table 2) shows that the second group (who received the new drug) had an average survival time equal to 19.79 weeks and was better than the first group (who received the traditional drug) by an average of 10 weeks.

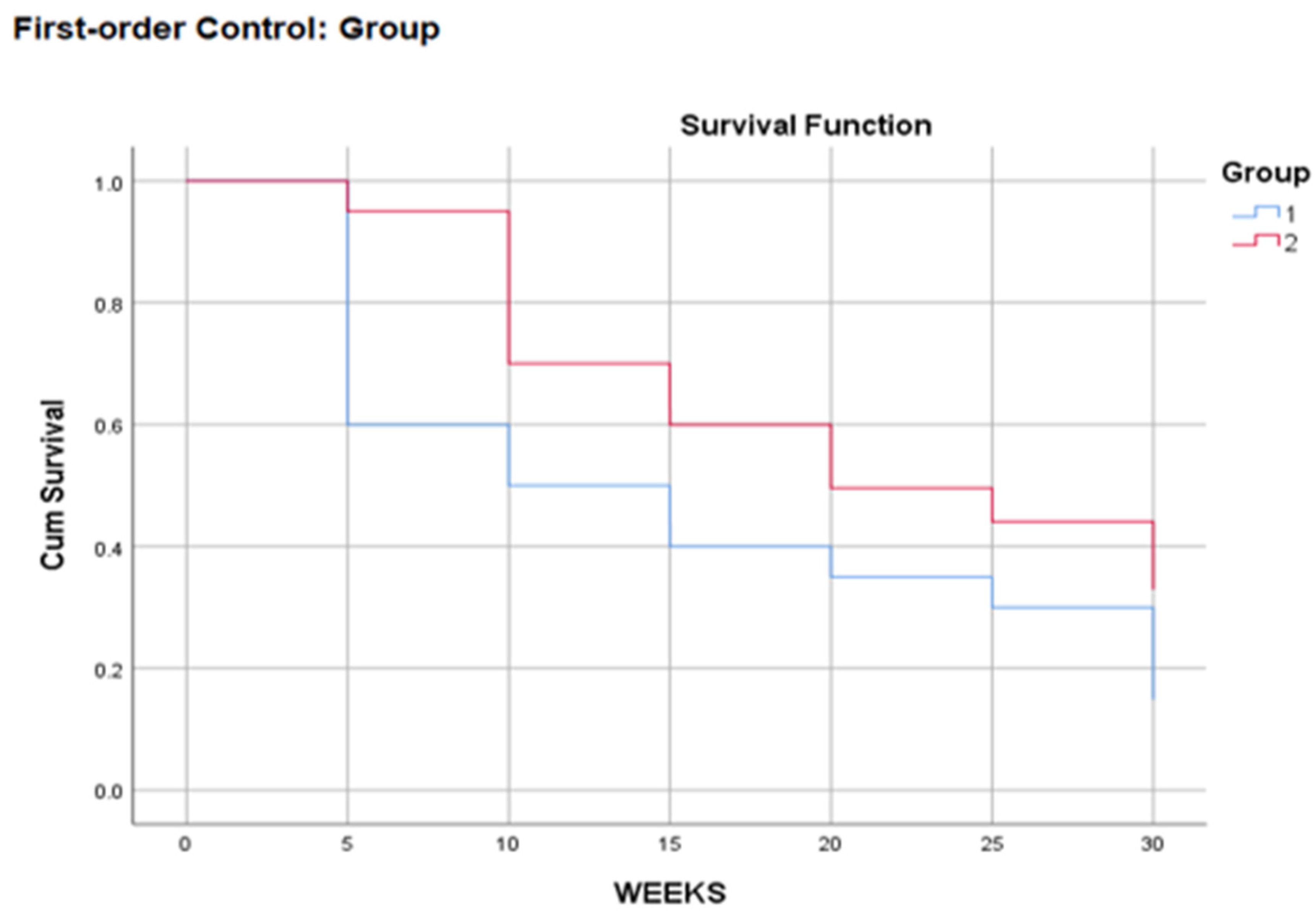

Survival curves give a visual representation of life schedules (

Figure 1). The horizontal axis shows the time of the event. In this figure, the decreases in the survival curve occur at 5-week intervals, as specified in the previous dialog box. The vertical axis shows the probability of survival. Thus, any point on the survival curve shows the probability that the patient will remain in a certain category after that time.

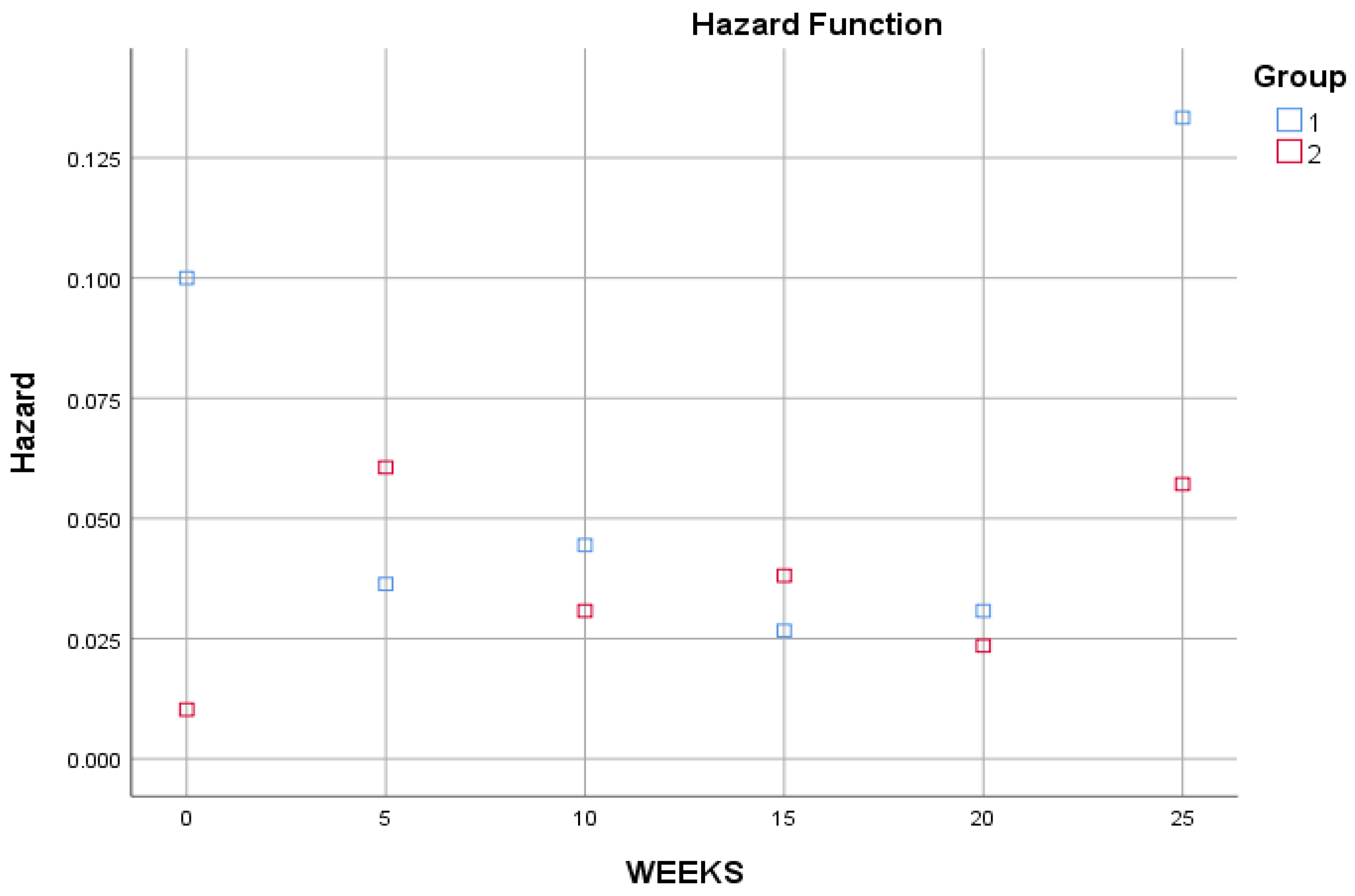

It seems that the patients of the first group have a lower survival curve than the second group, and this is confirmed by the following risk function in

Figure 2:

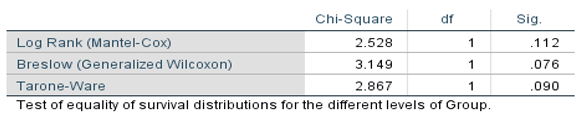

To determine whether these differences are due to chance, look at the tables of comparisons.

Table 3 provides a comprehensive test of the evenness of survival times across groups. The test statistics are based on the differences in the scores of the average group. Roughly speaking, the individual degree of the condition is increased for each comparison in which the survival time is higher and decreases when it has a lower survival time. The average score for the group is the average of the individual scores of the cases in the group. Since the value of p is greater than the morale level (0.05) of the Wilcoxon test (Jehan), you can conclude that the survival curves of the two groups do not differ significantly.

Kaplan-Meier Survival Analysis (Kaplan-Meier Survival Analysis):

There are several situations in which you may want to examine the distribution of times between two events, such as the length of employment (the time between hiring and leaving the company). However, this type of data usually includes some controlled cases. Controlled cases are cases where the second event was not recorded (for example, people were still working for the company at the end of the study). The Kaplan-Meier procedure is a method for estimating time-to-event models in the presence of controlled situations. The Kaplan-Meier model is based on estimating the conditional probabilities at each point in time when an event occurs and taking the resulting target (Limit) of these probabilities to estimate the survival rate at each point in time. For example, does the new AIDS treatment have any therapeutic benefit in prolonging life? You can conduct a study using two groups of AIDS patients, one receiving conventional treatment and the other receiving experimental treatment. The construction of the Kaplan-Meier model from the data will allow you to compare the overall survival rates between the two groups to determine whether the experimental treatment represents an improvement over conventional treatment. Kaplan Meier uses and Assumptions (Kaplan-Meier uses and Assumptions):

The Kaplan-Meier procedure uses a method for calculating life tables that estimate the survival or risk function at the time of each event. The life tables procedure uses an actuarial approach to survival analysis based on dividing the observation period into smaller time intervals and may be useful for dealing with large samples. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis is a descriptive procedure for examining the distribution of time variables to an event. In addition, you can compare the distribution by levels of the factor variable, or the product of separate analyses by levels of the stratification variable.

Assumptions: the probabilities for the event of interest should depend only on the time after the initial event - they are assumed to be stable concerning (positive) time. That is, cases entering the study at different times (for example, patients starting treatment at different times) should behave similarly. There should also be no stereotypical differences between controlled and uncontrolled cases. If many of the controlled cases are, for example, patients with more serious conditions, then your results may be biased. Let's get the following results:

The summary

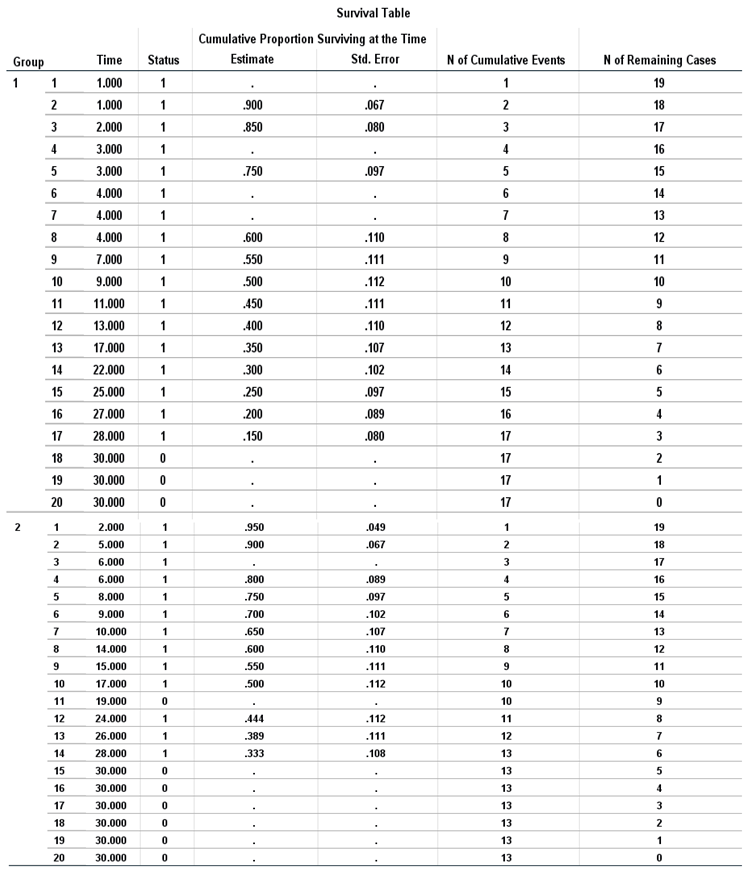

Table 4 of the case Operations shows that there were (40) sightings distributed over two groups of (20) sightings for which the first group took conventional treatment (17) event cases (death) versus (3) surviving cases, while the second group took suggested treatment for (13) death versus (7) surviving cases.

The survival schedule is a descriptive

Table 5, separating the time until the drug takes effect. The table is divided by each level of treatment, and each viewing takes its row in the table. As a result, the table is quite large. Time represents the time of occurrence of the event or control.

Status indicates whether the status has been subjected to the final event or has been censored.

Cumulative Proportion Surviving at the time: the cumulative percentage surviving at that time, that is, the percentage of cases that survived from the beginning of the table to this time. When multiple cases experience the final event at the same time, these estimates are calculated once for that period and apply to all cases where the drug has become effective at that time, with the standard error.

N of Cumulative Events: the number of cumulative events, that is, the number of cases that have gone through the experience of the event from the beginning of the table to this time.

N of Remaining Cases: the number of remaining cases, that is, the number of cases that at this time have not witnessed the final event or were not controlled.

Table 6 of survival averages and medians provides a quick numerical comparison of the "typical" Times of impact for both conventional treatments, proposed, and total. Since there is a lot of overlap in confidence intervals, it is unlikely that there will be a significant (or significant) difference in the "average" survival time.

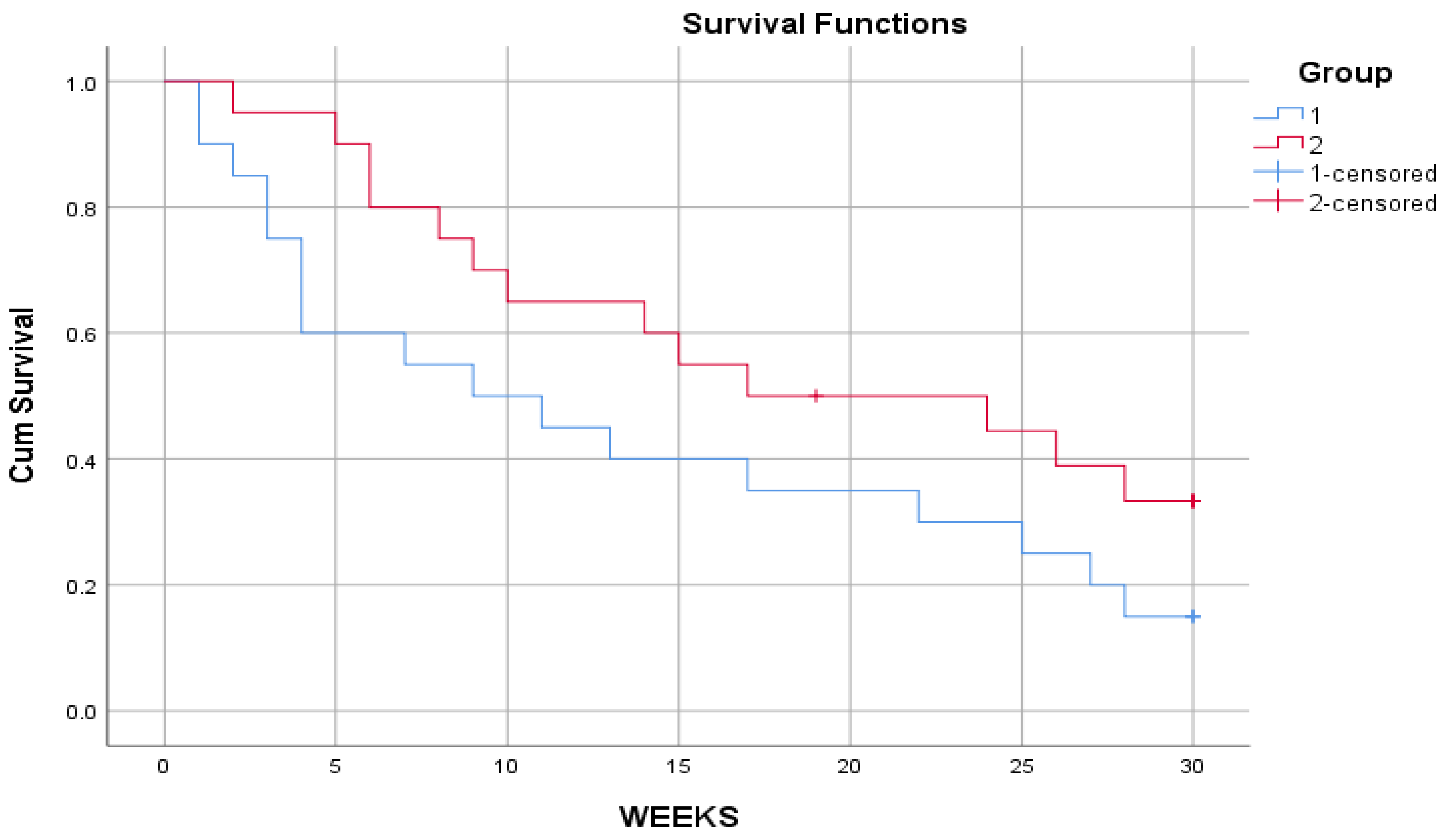

Table 7 presents the three comprehensive tests for the equalization of survival times across groups. Since the values of the tests of the teams are all greater than the morale level of 0.05, it is not possible to determine a significant difference between the survival curve of the first group compared with the second, as in

Figure 3.

The survival curves give a visual representation of the life tables; the horizontal axis shows the time of the event. in this figure, we observe a decrease in the survival curve when the drug is applied to the patient. The vertical axis shows the probability of survival. And therefore, any point on the survival curve shows the probability that the patient undergoing the appointed treatment will not feel comfortable by that time. The curve of the new drug is much steeper than the current one throughout most of the trial period, suggesting that the new drug may give an advantage over the old one. To determine whether these differences are due to chance and the results of which cannot be generalized, look at the table of comparisons.

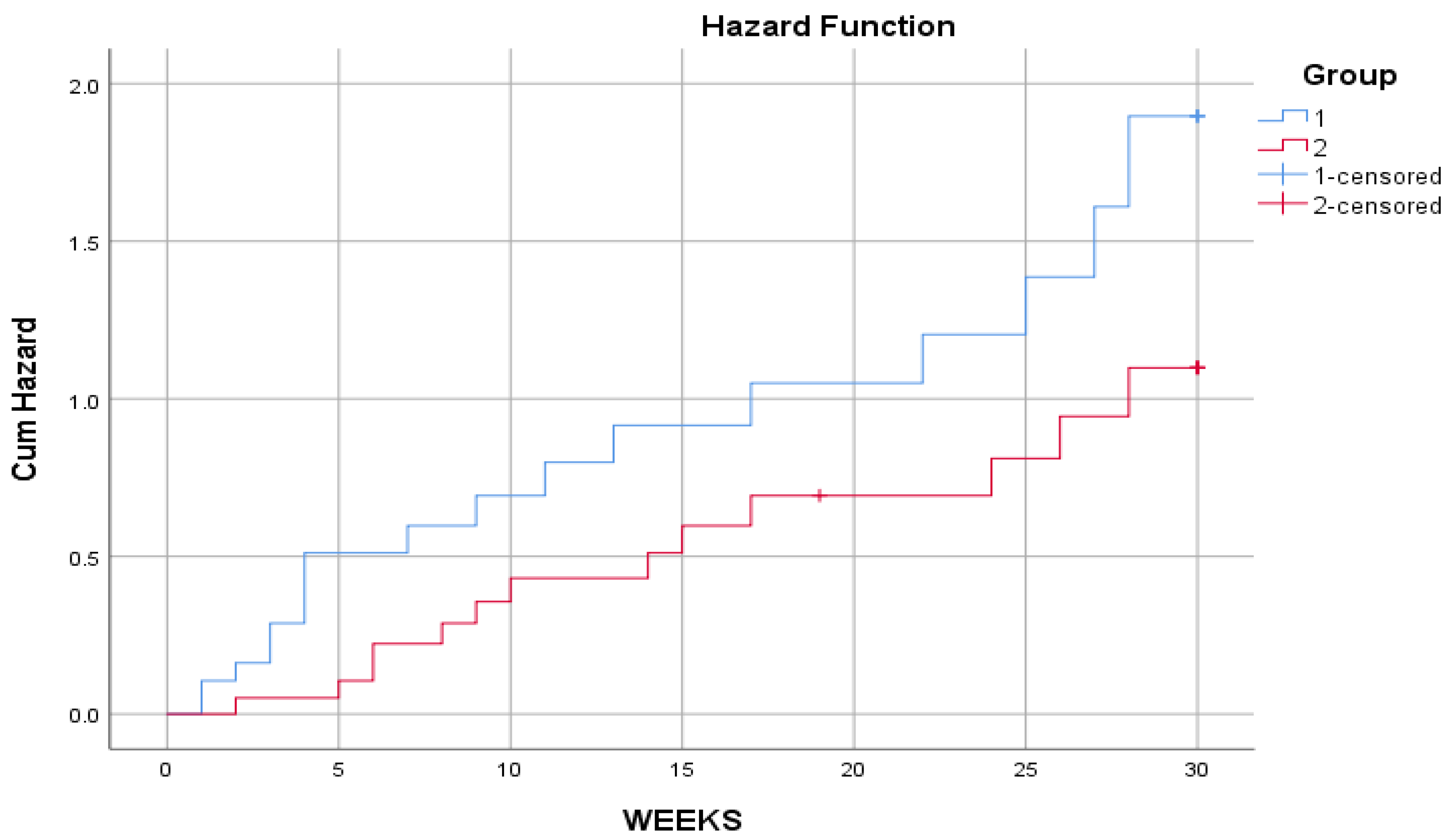

Using the Kaplan-Meier survival analysis procedure, the time distribution of the effect of two different drugs was tested, and comparative tests show that there is no statistically significant difference between them. We also note that the cumulative hazard function curve for the new drug group was lower than the cumulative hazard function curve for the traditional drug group, as shown in

Figure 4: