1. Introduction

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is an idiopathic, chronic, and progressive inflammatory disorder affecting the colon, characterized by continuous mucosal inflammation from the rectum to the proximal colon [

1]. The risk of colorectal cancer (CRC) after 20 years of disease duration has been estimated as high as 5-10% and individuals with UC have a 2.48-fold higher risk for colorectal cancer in comparison to the general population [2-7]. The pathogenesis of colitis-associated CRC (UC-CRC) differs significantly from that of sporadic CRC, following an inflammation–dysplasia–carcinoma sequence rather than the classic adenoma–carcinoma progression [

8,

9]. While endoscopic surveillance with random and targeted biopsies remains the gold standard for dysplasia detection in UC, it has inherent limitations, including sampling error, low dysplasia yield, low compliance, interobserver variability in histopathological interpretation, and challenges in distinguishing dysplasia from inflammatory regenerative changes [

10,

11]. Moreover, surveillance is resource-intensive, and subtle lesions may evade detection due to their flat morphology or the presence of field cancerization, wherein genetically altered but histologically normal-appearing mucosa gives rise to neoplasia [

5]. These limitations underscore the need for more precise and sensitive approaches, such as molecular biomarkers, to complement traditional screening strategies.

Tissue-based biomarkers have shown significant potential in addressing these gaps. Genetic mutations, particularly in

TP53, are frequently observed in early colitis-associated neoplasia, and may even precede histological dysplasia [

5,

11]. Additionally, epigenetic changes, such as DNA methylation of tumor suppressor genes and mismatch repair gene promoters, are also early and widespread events, contributing to the field effect seen in UC patients [

5,

6]. Aneuploidy, reflecting chromosomal instability, has also been correlated with progression to high-grade dysplasia and carcinoma, and is emerging as a possible prognostic indicator [

10,

12]. Lastly, several microRNAs (miRNAs) have been identified as early markers of neoplastic changes and hold promise for risk stratification [

5,

12].

This narrative review seeks to examine the current landscape of tissue-based biomarkers for their utility in CRC screening among UC patients. Firstly, we will discuss the pathogenesis of CRC in UC. Secondly, we will map out the available evidence and identifying gaps in point mutations, aberrant methylation changes, and microRNA dysregulation in UC-associated CRC. We aim to inform future research directions and support the notion of integrating tissue-based biomarkers into personalized surveillance strategies for this high-risk population.

2. Materials and Methods

The study design of a scoping review was considered most suitable to explore multiple, emerging key concepts for CRC risk in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) [

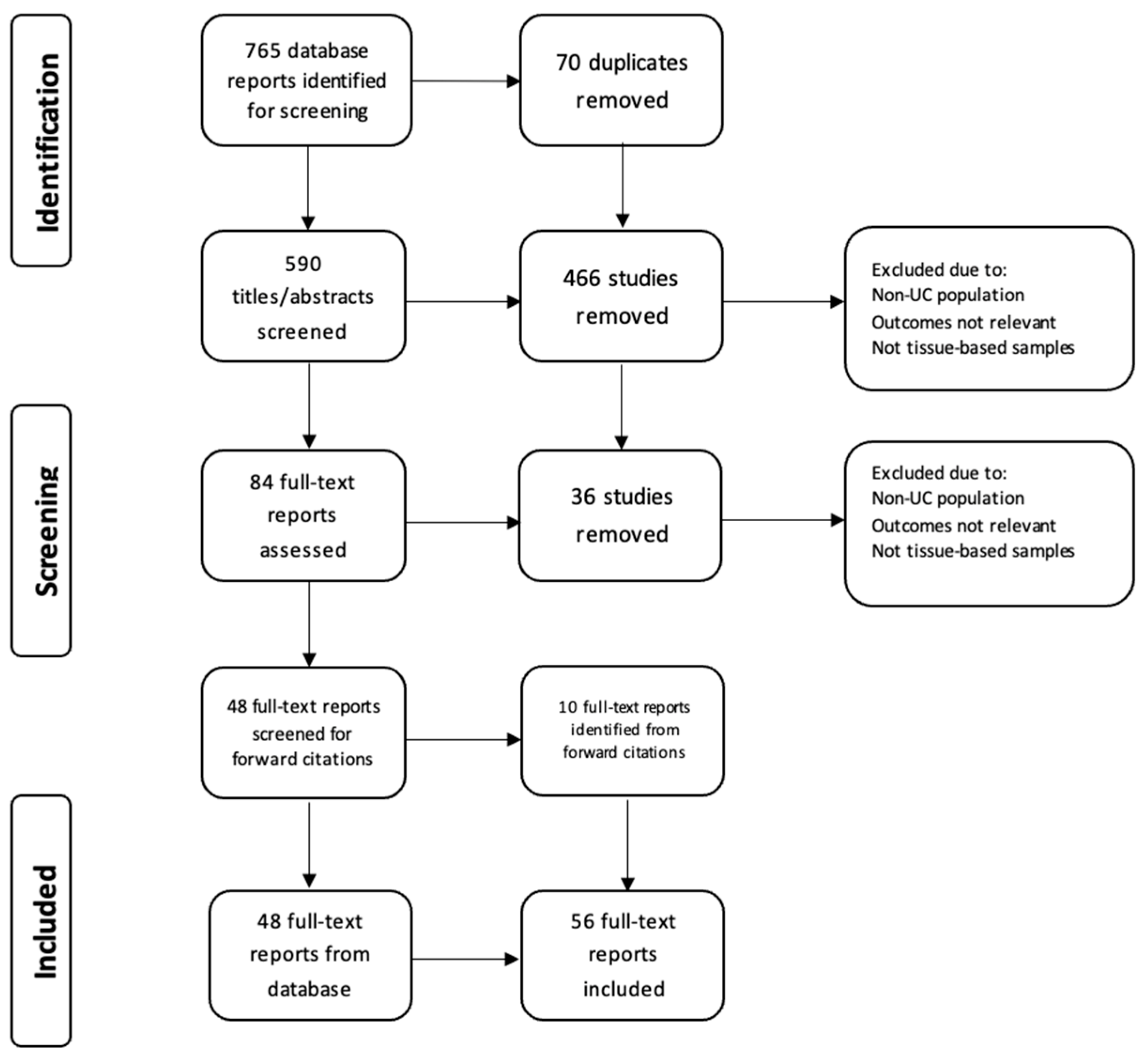

13]. A literature search was conducted on the 31 of March 2025 using the electronic database PubMed, OVID/Medline to identify relevant English language articles published between 1984 and March 31, 2025. In addition, reference lists of the identified articles were screened for additional studies. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) extension for scoping reviews was followed. The following search strategy was used: ((“Colitis, Ulcerative” [Mesh]) OR (Ulcerative colitis OR IBD OR UC OR Inflammatory Bowel Disease OR Colitis OR Proctocolitis OR Pancolitis)) AND (Tumor marker* OR Tumour marker* OR

TP53 OR

KRAS OR oncogene* OR telomere* OR microRNA OR miRNA OR mutation OR biomarker*) AND (Colorectal cancer OR colon cancer OR rectal cancer OR polyps OR dysplasia OR neoplasia OR ulcerative colitis-associated neoplasia) AND (Field effect OR screening OR surveillance). This initial search identified 765 articles, of which 124 were identified following duplication removal and title screen, and 84 articles identified following abstract screening. Original articles were considered eligible if 1) molecular biomarkers were assessed in patients with UC and/or 2) biomarkers were related to clinical outcomes, and/or 3) biomarkers were obtained via colorectal biopsy. Articles were excluded if they were non-human studies or did not examine biomarkers from colorectal tissue. Finally, 58 articles were included in this review (

Figure 1). ChatGPT 4.0 was used in the partial image generation of figure 2.

Figure 1.

: The PRISMA flow diagram details our search and selection process applied during the review.

Figure 1.

: The PRISMA flow diagram details our search and selection process applied during the review.

Figure 2.

: The “field effect” demonstrating how dysplastic and neoplastic tissue develops from a field of genetically altered, histologically normal epithelium.

Figure 2.

: The “field effect” demonstrating how dysplastic and neoplastic tissue develops from a field of genetically altered, histologically normal epithelium.

3. Pathogenesis

Colorectal cancer is a well-recognized complication of longstanding UC, arising via a distinct inflammation-driven pathway that differs from the sporadic adenoma–carcinoma sequence [

8,

9]. In UC, chronic relapsing inflammation initiates a cascade of molecular alterations that promote carcinogenesis across a broad field of the colonic mucosa—a phenomenon known as the “field effect” (figure 1) [

5]. The main predictors clinically are extent, severity of inflammation, duration and probably age at onset of UC. Thus, this field of genetically altered histologically normal tissue provides fertile ground for multifocal neoplastic transformation.

The earliest pathogenic changes are linked to sustained oxidative stress. Inflammatory cells in UC release reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS and RNS), causing direct DNA damage in epithelial cells [

6,

14]. Oxidative DNA injury contributes to point mutations, strand breaks, and chromosomal instability, ultimately promoting neoplastic transformation. Furthermore, aberrations in immune surveillance, such as disrupted epithelial cell–T-cell crosstalk via CD80, are implicated in the progression from low-grade dysplasia to cancer [

6]. Importantly, these effects are compounded by the activation of pro-tumorigenic signaling pathways such as IL-6/STAT3 and TNFα/NF-κB, which enhance epithelial cell survival, proliferation, and resistance to apoptosis [

15].

A defining early event in UC-associated carcinogenesis is the mutation of the tumor suppressor gene

TP53 [

15]. Unlike in sporadic CRC, where

TP53 mutations typically occur later in the mutation cascade, in UC, they are frequently found in non-dysplastic or early dysplastic mucosa, suggesting a role initiating neoplastic change [

6,

16]. Overexpression of the interferon-inducible gene

1-8U has also been observed in severely inflamed and cancerous UC mucosa, indicating its potential utility in distinguishing high-risk areas before morphological dysplasia appears [

16]. Conversely, mutations in

APC and

KRAS, which are early events in sporadic CRC, are less common or delayed in UC-CRC, emphasizing the divergence in molecular pathogenesis [

15,

17].

Epigenetic dysregulation also plays a pivotal role. Promoter hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes and mismatch repair genes leads to gene silencing and contributes to both microsatellite instability and chromosomal instability [

6,

14]. It has been proposed that the increased oxidative stress in patients with UC results in enough DNA damage to exceed the capacity of repair mechanisms, eventually leading to the accumulation of DNA damage and microsatellite instability. Additional molecular changes in keeping with accelerated aging such as telomere shortening and aneuploidy further destabilize the genome, promoting progression from low-grade to high-grade dysplasia and ultimately to invasive carcinoma [

18].

Baker et al. have described three conceptual types of the field effects including 1) etiologic (environment exposures. diet, microbiome, and genetic factors promoting a microenvironment of cancer susceptibility), 2) molecular (point mutations, aneuploidy, telomere shortening, etc), and 3) morphologic (normal tissue, dysplasia, cancer) [

5]. Clinically, dysplasia in UC is often flat or invisible, making detection challenging. These lesions tend to arise diffusely within areas of active or previously inflamed mucosa rather than from discrete polyps [

4,

19]. Notably, flat dysplastic lesions exhibit higher levels of genomic instability, including aneuploidy and widespread DNA copy number alterations, compared to visible polypoid lesions or sporadic adenomas [

19]. Furthermore, patients with early onset UC who develop CRC have been shown to have extensive fields of molecular abnormalities throughout their colons compared to patients who have late onset of disease [

5]. Specifically, large clonal populations with shortened telomeres have been identified within multiple non-dysplastic areas of the colon among UC patients with high-grade dysplasia or cancer, yet almost never in those who had late onset of UC [

5]. This diffuse and unpredictable pattern reinforces the importance of field cancerization as a central concept in UC carcinogenesis [

5].

The pathogenesis of UC-CRC is multifactorial, driven by multiple factors including chronic inflammation, oxidative DNA damage, early TP53 mutations, epigenetic silencing, and genomic instability, summarized in figure 2. The field effect and the presence of flat, genomically unstable dysplasia further distinguish UC-CRC from its sporadic counterpart, underscoring the need for enhanced molecular surveillance strategies.

4. Point Mutations

Genetic mutations, particularly in tumor suppressor genes and oncogenes, are central to the pathogenesis of UC-CRC in UC [

20,

21]. Among the most studied genetic mutations in UC-CRC are those affecting the

TP53 and

KRAS genes. These mutations not only delineate the molecular evolution of UC-CRC but also offer opportunities for early detection and risk stratification through tissue-based surveillance.

TP53 mutations are widely acknowledged as early events in the neoplastic progression of UC and numerous studies have shown that

TP53 mutations are frequently detected in histologically normal or inflamed mucosa, preceding dysplasia and carcinoma [22-32]. Using next generation sequencing (NGS) Singhi et al. examined genetic mutations associated with dysplastic and neoplastic tissue in IBD. Alterations in

TP53 were detected in 71% of specimens with low-grade dysplasia, 83% of those with high-grade dysplasia, and 100% in colorectal adenocarcinoma. By comparison, no mutations of TP53 or other genes were identified within uninvolved colonic tissue [

25]. Brentnall et al. further demonstrated that mutations at codon 248 of

TP53 were found not only in dysplastic and neoplastic tissues but also in adjacent non-dysplastic mucosa, indicating clonal expansion and the phenomenon of field cancerization in UC-CRC development [

28]. This was corroborated by Hirsch et al., who found that

TP53 mutations were present in 87% of UC-CRC cases, a higher frequency than observed in sporadic CRC (61%). These mutations were often unique across different tumor sites in the same patient, suggesting multiple independent neoplastic events driven by chronic inflammation [

27].

Further, studies employing immunohistochemistry (IHC) for

TP53 have demonstrated that its overexpression correlates strongly with dysplasia and cancer. For example, Xie et al. observed a progressive increase in

TP53 nuclear staining from negative mucosa through low- and high-grade dysplasia to carcinoma. They found that combining

TP53 overexpression with cytokeratin 7 positivity significantly improved diagnostic specificity for dysplasia in UC patients [

28]. Horvath et al. expanded on these findings by demonstrating that p53 overexpression in mucosa indefinite for dysplasia predicted subsequent progression to neoplasia in 25% of patients, reinforcing its role as an early biomarker of malignant potential [

30].

Fuji et al. further demonstrated the potential of IHC analysis to detect

TP53 alterations [

33]. In their study, 59.5% (25 of 42) of the neoplastic lesions (dysplasia and carcinoma) and 40.0% of the lesions that were indefinite for dysplasia displayed nuclear accumulation of p53 protein. Thus, IHC analysis of p53 could serve as a useful marker of neoplasia, particularly where discrimination between neoplasia and regenerative epithelium is difficult [

33]. However, the authors importantly note that not all mutations (e.g. nonsense or frameshift mutations) result in accumulation of the p53 protein in the nucleus. In fact, approximately 93% of neoplastic lesions that displayed negative IHC staining for p53 protein demonstrated a

TP53 mutation within exons 5-8 under PCR single-stranded conformation polymorphism, suggesting increased sensitivity of PCR methods for detecting UC-CRC [

33].

KRAS mutations, in contrast, appear less frequently and tend to occur later in the sequence of UC-CRC progression. In a meta-analysis by Du et al.,

KRAS mutations were significantly less common in UC-CRC compared to sporadic CRC (RR = 0.71), whereas

TP53 mutations were more frequent (RR = 1.24) [

20]. Studies analyzing colonic lavage fluid have found

KRAS mutations in a minority of UC patients, often co-occurring with

TP53 mutations and typically in those with longer disease duration [

30]. Given

KRAS mutations have not been shown to be a significant predictor of dysplasia and have low specificity in stool and tissue samples, they are less likely to play a role in future clinical practice [

34,

35].

The integration of these mutations into colorectal cancer surveillance strategies offers promise. TP53 mutations, detectable through PCR-based methods, IHC, or even in colonic lavage fluid, serve as early indicators of neoplastic transformation [22-32]. Importantly, detection in non-dysplastic mucosa underscores their utility in identifying high-risk patients even before histologic changes occur. This is particularly valuable in UC, where dysplasia may be multifocal, flat, and easily missed during routine colonoscopy.

5. Methylation Patterns

Aberrant DNA methylation plays a critical role in the pathogenesis of UC-CRC, functioning as a key epigenetic mechanism that contributes to the silencing of tumor suppressor genes during the inflammation-dysplasia-carcinoma sequence [33,36-38]. Methylation changes, particularly promoter hypermethylation of specific genes, are detectable in non-neoplastic mucosa and are often associated with long-standing disease and extensive colitis, suggesting their potential as early biomarkers of neoplastic transformation [

36,

38].

One of the earliest and most well-studied epigenetic alterations involves the

p14ARF gene. In a prospective study, hypermethylation of

p14ARF was found in 100% of dysplastic tissues and 26% of rectal biopsies from patients without histologic dysplasia, indicating its presence as an early, potentially pre-dysplastic event. Importantly, individuals with

p14ARF hypermethylation were significantly more likely to develop dysplasia during surveillance compared to those without such methylation, underscoring its predictive value for future neoplastic progression [

36].

Similarly, hypermethylation of the tumor-suppressive miRNA gene miR-124a has been identified as a potential biomarker for use in CRC risk stratification among patients with UC. In one study, elevated methylation levels of miR-124a-3 were correlated with known risk factors such as pancolitis and long disease duration. Patients with both pancolitis and long-standing UC had 7.4-fold higher methylation levels than those without these risk factors [

37]. Similarly, miR-9 methylation has been shown to be significantly higher in neoplastic tissue compared to normal tissues [

39]. These findings highlight the potential of epigenetic markers such as DNA methylation that may serve as a quantitative measure of cumulative carcinogenic risk and can potentially distinguish between patients at low and high risk for UC-CRC.

Hypermethylation of

SYNE1 and

FOXE1, two genes involved in cell cycle regulation and tumor suppression, have been investigated as possible biomarkers for risk stratification for the development of UC-CRC [

38]. In a retrospective study by Papadia et al., these genes showed significantly increased promoter methylation in colorectal tissue from patients with dysplasia and UC-CRC compared to those with non-dysplastic colitis and healthy controls. Whereas hypermethylation of both

FOXE1 and

SYNE1 was absent among controls, promoter hypermethylation was detected in biopsies of 60% of patients with colitis-associated colorectal cancer for

FOXE1 and 80% for

SYNE1. Hypermethylation was increasingly likely with increased disease severity, indicating that it may be a specific marker of malignant transformation in the setting of chronic inflammation [

38]. Increased methylation of additional genes such as

ER,

BMP3, and

NDRG4 have been identified as possible markers of high risk for the development of UC-CRC [

33]. Interestingly, high levels of

ER gene methylation have been found not only in regions with neoplasia but also in other areas widely dispersed throughout the colorectum. These results suggest that a single biopsy sample may suffice when attempting to identify high-risk individuals, minimizing the requirement of numerous biopsy samples [

33].

The ENDCAP-C study sought to validate previously identified biomarkers of neoplasia in a retrospective cohort and create predictive models for later validation in a prospective cohort [

40]. In a study including 35 patients with cancer, 78 with dysplasia and 343 without neoplasia undergoing surveillance for UC-CRC across 6 medical centres, a multiplex methylation panel including five markers (

SFRP2, SFRP4, WIF1, APC1A, APC2) was accurate in detecting pre-cancerous and invasive neoplasia (AUC = 0.83; 95% CI: 0.79, 0.88), and dysplasia (AUC = 0.88; (0.84, 0.91). In the setting of non-neoplastic mucosa, modest accuracy was achieved (AUC = 0.68; 95% CI: 0.62,0.73) in predicting associated bowel neoplasia through the methylation patterns of distant non-neoplastic colonic mucosa [

40]. Here, the authors present a model for incorporating tissue-based biomarker panels for the detection of existing neoplasia and prediction of developing UC-CRC from non-neoplastic tissue.

Methylation markers may address current limitations in endoscopic surveillance, such as sampling error and interobserver variability in interpreting indefinite or low-grade dysplasia. Epigenetic testing could help stratify patients more precisely, allowing personalized surveillance intervals based on molecular risk rather than histologic findings alone. DNA methylation patterns—particularly those involving genes like p14ARF, miR-124a, miR-9, SYNE1, and FOXE1—represent a promising avenue for enhancing CRC surveillance in ulcerative colitis

6. microRNA

MicroRNAs (miRNA) have emerged as pivotal molecular regulators in the pathogenesis of CRC in patients with UC. These small non-coding RNAs function post-transcriptionally by binding to target mRNAs to suppress gene expression [41, 42]. miRNA play an important regulatory role in gene expression, protein translation and have been shown to impact the expression of oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes. In UC-CRC, chronic inflammation contributes to dysregulated miRNA expression, affecting key processes like cell proliferation, apoptosis, and immune response modulation [

41]. This unique interaction between inflammatory signaling and miRNA dysregulation plays a fundamental role in the neoplastic transformation of the colonic epithelium. Thus, miRNA expression profiles in dysplastic and neoplastic tissues remains a key area for further investigation and research, as elucidating specific miRNA profiles may serve to identify patients at high risk of developing UC-CRC [

42].

Several miRNAs have been identified as potential tissue-based biomarkers of early neoplastic changes in UC. For instance, miR-21, an oncogenic miRNA, is significantly upregulated in inflamed UC mucosa and even more elevated in UC-CRC, where it likely promotes inflammation-associated carcinogenesis by enhancing proliferative and anti-apoptotic pathways [

38]. miR-135b also shows a stepwise increase in expression from non-dysplastic to dysplastic and then to neoplastic tissues in UC, positioning it as a possible biomarker for tracking malignant progression [

43].

Profiling studies have demonstrated distinct miRNA expression signatures across different stages of neoplastic progression in UC. For example, differential expression of miR-192, miR-194, and miR-215 has been observed between UC and UC-CRC tissues, highlighting their utility in distinguishing neoplastic from inflamed but non-cancerous tissue [

44,

45]. In particular, miR-215 has been shown to be significantly upregulated in non-dysplastic mucosa 1 to 5 years prior to the onset of neoplasia in patients with long-standing UC [

44]. This implies a field effect where molecular changes precede histologic abnormalities. Its elevated expression in UC-CRC and adjacent non-dysplastic mucosa compared to normal controls underlines its role in early tumorigenesis and its potential as a predictive biomarker for cancer development [

44] miR-9, while often studied in the context of methylation, is notable for its epigenetic silencing in UC-CRC. Studies have shown that miR-9 methylation increases with age, disease duration, and proximity to cancer, and is significantly higher in rectal mucosa from UC-CRC patients compared to controls [

34]. Its methylation status can distinguish cancer from non-neoplastic tissues with high accuracy (AUC: 0.94), suggesting that its epigenetic downregulation may be both a marker and a mechanistic contributor to carcinogenesis [

39].

The clinical implications of these findings are substantial. Given their stability in formalin-fixed tissues and even biofluids, miRNAs are ideal candidates for minimally invasive surveillance tools [

46]. They offer the potential to complement or even surpass current histologic approaches, which are limited by sampling error and interpretive variability. Incorporating miRNA signatures into surveillance protocols could enable earlier detection of at-risk mucosa, guide colonoscopy intervals, and tailor preventive interventions to those at highest risk.

7. Other Biomarkers

Additional biomarkers of interest such as telomere shortening, copy number variation (CNV), and aneuploidy offer valuable insights into the molecular pathogenesis of CRC in patients with UC, and serve as promising tools for cancer surveillance in this high-risk population. These markers reflect genomic instability, a key feature of the inflammation-dysplasia-carcinoma sequence unique to UC-associated CRC.

Telomere shortening, often driven by chronic inflammation, plays a significant role in early carcinogenic processes. Salk et al. demonstrated that patients with early-onset UC who developed neoplasia exhibited significantly shorter telomeres in non-dysplastic mucosa compared to individuals who did not develop neoplasia [

47]. These patients also had an increased prevalence of clonal expansions—clonal mutations in polyguanine tracts resulting in fields of genetically altered epithelium–suggesting that telomere erosion may precede and facilitate clonal proliferation and malignant transformation. In this study, clonal expansions were associated with proximity to dysplasia, and the mean percentage of clonally expanded mutations distinguished early-onset progressors from non-progressors with 100% sensitivity and 80% specificity. These results convey the potential of clonal expansions as potential biomarkers for surveillance, particularly in younger patients with extensive disease [

47].

Copy number variations are a hallmark of chromosomal instability and are increasingly recognized in UC-associated neoplasia. A study by Shivakumar et al. using array comparative genomic hybridization identified distinct CNVs in UC-associated neoplasia compared to sporadic CRC. Genes such as

MYC,

CCND1, and

EGFR were amplified in dysplastic and neoplastic tissues, and their expression levels correlated with disease progression [

38]. These CNVs, especially when validated through qRT-PCR and immunohistochemistry, provided moderate predictive value for detecting neoplasia in UC, and may ultimately complement histopathologic evaluation [

48].

Aneuploidy, or abnormal DNA content, has long been associated with malignancy and is a strong indicator of genomic instability in UC [

49]. Meling et al. analyzed DNA ploidy in dysplastic and non-dysplastic mucosa of UC patients and found that DNA aneuploidy was present not only in carcinomas but also in flat mucosa and dysplastic tissues—often in areas devoid of histologic abnormalities [

49]. Importantly, aneuploidy was observed in patients who subsequently developed metastatic CRC, underscoring its prognostic relevance. When comparing histologic dysplasia to DNA flow cytometry, cytometric analysis offers the advantage of higher intra-observer reliability in interpreting DNA histograms. Rubin et al. proposed that aneuploidy detected in biopsies classified as indefinite for dysplasia may forecast future progression [

50]. In their prospective study of 25 high-risk UC patients, five of six individuals with aneuploidy developed dysplasia within 1–2.5 years, whereas none of the nineteen patients without aneuploidy progressed during the same period. Similar findings were reported by Lofberg et al., who observed that aneuploidy preceded, coincided with, or followed the development of dysplasia in a cohort of 59 patients [

50]. Importantly, mutations were not confined to dysplastic lesions but were detected throughout the colon in patients who eventually developed dysplasia. In some cases, mutations were identified during endoscopic procedures in areas without histologic evidence of dysplasia. This could reflect either sampling error or widespread genomic instability. The latter is supported by other molecular markers of instability, including p16 promoter methylation, elevated telomerase activity, and chromosomal aberrations detected by comparative genomic hybridization in resected colons from UC-CRC patients [

51]. Given its occurrence in non-dysplastic tissue, DNA aneuploidy may serve as an adjunctive biomarker, identifying patients who might benefit from intensified surveillance despite the absence of histologic dysplasia [49-51].

The integration of telomere shortening, CNVs, and aneuploidy into UC surveillance strategies offers a molecularly informed approach that can overcome the limitations of conventional histology. These biomarkers not only precede visible dysplasia but also reflect underlying genomic alterations, enabling early detection of cancer risk and personalized surveillance protocols for patients with long-standing UC.

8. Discussion

Tumorigenesis in UC is recognized as a multistep process, progressing from low-grade dysplasia to high-grade dysplasia and ultimately carcinoma [

47,

49]. As discussed in this review, several studies have described the occurrence of a field effect, whereby neoplastic lesions arise from colonic tissue displaying molecular or genetic alterations that precede dysplastic changes [

5,

18,

53]. Current ACG surveillance guidelines recommend that individuals with UC and a disease duration exceeding eight years undergo evaluation with colonoscopy every one to two years for the early detection of dysplasia, while ECCO and BSG utilize stratified guidelines that determine the frequency of surveillance [52,54-56]. Despite advances in endoscopic imaging such as the use of chromoendoscopy, studies have not shown a direct effect in preventing all-cause/cancer-specific mortality or time to interval cancer [

57]. However, the efficacy of this approach is limited by the morphologic characteristics of UC-associated dysplasia, which is frequently flat and endoscopically inconspicuous [

32]. As a result, surveillance typically relies on systematic 4-quadrant random biopsies taken at 10 cm intervals throughout the colon. While this strategy is intended to enhance histologic detection, it is inherently resource-intensive, invasive, and reliant on probabilistic sampling. For example, a previous survey of British gastroenterologists found that only 24% conducted surveillance colonoscopy in patients with left-sided colitis, while only 2% routinely took more than 20 biopsies and only 53% recommended colectomy when high-grade dysplasia was identified [

58]. Consequently, it may preferentially detect more extensive or advanced lesions while missing focal or early neoplastic changes. This underscores a critical gap in current surveillance paradigms—namely, the lack of reliable, sensitive biomarkers capable of identifying molecular alterations that precede histological dysplasia. Incorporating such biomarkers into routine screening could improve early risk stratification, reduce procedural burden, and enhance the precision of colorectal cancer surveillance in UC.

Numerous biomarkers have been proposed as potential candidates to further improve colorectal cancer screen in patients with UC, as discussed in this review and summarized in table 1. While this review does not represent an exhaustive overview of all biomarkers proposed (see Chen et al. for a comprehensive overview), promising markers are discussed and the need for additional prospective research is highlighted [

7]. For example,

TP53 mutations represent a robust early biomarker of neoplastic progression in UC-associated colorectal carcinogenesis. Detection in non-dysplastic tissue supports their role in field cancerization and use as an adjunctive biomarker to identify patients at high risk of developing UC-CRC, who may benefit from additional screening. Additional genetic markers including aneuploidy, telomere shortening, CNVs, epigenetic methylation and miRNA expression patterns hold promise in their ability to stratify patients more precisely. Their association with disease duration, extent, and progression to dysplasia underscores their value not only as early markers of carcinogenesis but potential to inform personalized surveillance intervals based on molecular risk rather than histologic findings alone to be developed.

Recent evidence supports the clinical utility of genomic biomarkers in risk stratification for UC associated neoplasia. In a multicenter case–control study, Al Bakir et al. demonstrated that low-pass whole genome sequencing (lpWGS) of low-grade dysplasia (LGD) lesions in UC patients can robustly predict progression to advanced neoplasia (high-grade dysplasia or colorectal cancer) [59]. They study analyzed 270 LGD samples and found that the burden of somatic copy number alterations (CNAs) was significantly greater in patients who progressed. A genomic CNA score, derived from features such as chromosome 17q loss and microsatellite instability, showed superior predictive performance compared to conventional clinicopathologic factors. When combined with clinical variables like incomplete resection, the multivariate model achieved an AUC of 0.95 at 5 years. These findings suggest that CNA profiling via lpWGS could serve as a scalable and cost-effective adjunct to current surveillance protocols, enabling more precise identification of high-risk patients and reducing unnecessary colectomies [59].

Table 1.

Summary of key biomarkers identified in UC-CRC and their clinical relevance as possible markers in UC-CRC screening.

Table 1.

Summary of key biomarkers identified in UC-CRC and their clinical relevance as possible markers in UC-CRC screening.

| Analyte |

Biomarker |

Clinical Relevance |

Reference |

| DNA |

TP53 |

TP53 mutations are prevalent in UC-associated dysplasia and cancer, detected in 71–100% of lesions, but absent in uninvolved mucosa. These mutations often occur in non-dysplastic tissue, supporting field cancerization. TP53 overexpression on IHC correlates with dysplasia and neoplasia and improves diagnostic specificity when combined with CK7. While some mutations evade IHC detection, PCR analysis detects TP53 mutations in 93% of IHC-negative neoplastic lesions, indicating its value as a sensitive molecular marker. |

5,11,15,16,22-33 |

| KRAS |

KRAS mutations are less frequent in UC-CRC than sporadic CRC, occur later in tumor progression, and often co-occur with TP53 mutations. Due to their low predictive value for dysplasia and poor specificity in stool and tissue samples, KRAS mutations likely have limited clinical utility in UC-CRC surveillance. |

34,35 |

| Aneuploidy |

In a prospective study of 25 high-risk UC patients, five of six individuals with aneuploidy developed dysplasia within 1–2.5 years, whereas none of the nineteen patients without aneuploidy progressed during the same period. Similar findings were reported by Lofberg et al., who observed that aneuploidy preceded, coincided with, or followed the development of dysplasia in a cohort of 59 patients |

10,12,18,48-50 |

| 1-8U |

IFN-inducible gene 1-8U was highly expressed in UC-associated cancers and chronically inflamed UC mucosa but absent in normal tissue. Its expression was independent of disease duration or extent |

16 |

| Telomere shortening |

Shortened telomeres and clonal expansions were common in non-dysplastic mucosa of early-onset UC Progressors, distinguishing them from non-progressors with high sensitivity and specificity. These changes, absent in late-onset cases, suggest telomere shortening may serve as a biomarker for cancer risk in early-onset UC-associated colorectal cancer. |

5,46 |

| Clonal expansions |

Clonal expansions have been associated with proximity to dysplasia, and in one study the mean percentage of clonally expanded mutations distinguished early-onset progressors from non-progressors with 100% sensitivity and 80% specificity |

46 |

| Copy number variations |

Expression levels of amplified genes such as MYC, CCND1, and EGFR amplified in dysplastic and neoplastic tissues are correlated with disease progression. Low-pass whole genome sequencing (lpWGS) of low-grade dysplasia (LGD) lesions in UC patients can robustly predict progression to advanced neoplasia multivariate model achieved an AUC of 0.95 at 5 years. |

47,58 |

microRNA

|

miR-21 |

miR-21 is significantly upregulated in inflamed UC mucosa and even more elevated in UC-CRC, where it likely promotes inflammation-associated carcinogenesis by enhancing proliferative and anti-apoptotic pathways |

38 |

| miR-135b |

miR-135b shows a stepwise increase in expression from non-dysplastic to dysplastic and finally to neoplastic tissues in UC, positioning it as a possible biomarker for tracking malignant progression |

42 |

miR-192

miR-194

miR-215 |

Differential expression of miR-192, miR-194, and miR-215 has been observed between UC and UC-CRC tissues, highlighting their utility in distinguishing neoplastic from inflamed but non-cancerous tissue. In particular, miR-215 has been shown to be significantly upregulated in non-dysplastic mucosa 1 to 5 years prior to the onset of neoplasia in patients with long-standing UC. |

43,44 |

Methylation

|

p14ARF |

In a prospective study, hypermethylation of p14ARF was present in all dysplastic tissues and 26% of non-dysplastic biopsies, suggesting it as an early, pre-dysplastic event. Its presence significantly predicted future dysplasia, supporting its potential role as a biomarker for neoplastic progression in ulcerative colitis. |

36 |

| miR-124a |

elevated methylation levels of miR-124a-3 were correlated with known risk factors such as pancolitis and long disease duration. Patients with both pancolitis and long-standing UC had 7.4-fold higher methylation levels than those without these risk factors |

37 |

| miR-9 |

miR-9 methylation increases with age, disease duration, and proximity to cancer, and is significantly higher in rectal mucosa from UC-CRC patients compared to controls (34). Its methylation status has been used to distinguish cancer from non-neoplastic tissues with high accuracy (AUC: 0.94) |

34,39 |

| SFRP2, SFRP4, WIF1, APC1A, APC2 |

Accurate in detecting pre-cancerous and invasive neoplasia (AUC = 0.83) and dysplasia (AUC = 0.88). For non-neoplastic mucosa a four marker panel (APC1A, SFRP4, SFRP5, SOX7) had modest accuracy (AUC = 0.68; 95% CI: 0.62,0.73) in predicting associated bowel neoplasia through the methylation signature of distant non-neoplastic colonic mucosa. |

40 |

SYNE1 FOXE1

ER

BMP3

NDRG4

|

Hypermethylation of SYNE1 and FOXE1 was detected in 80% and 60% of UC-CRC cases, respectively, but absent in controls, correlating with disease severity. Additional hypermethylated genes (ER, BMP3, NDRG4) have also been linked to high UC-CRC risk. Single biopsy sampling may suffice due to widespread methylation patterns. |

33,38 |

9. Conclusion

Numerous tissue biomarkers with the potential to identify high-risk patients for ulcerative colitis-associated colorectal cancer (UC-CRC) have been discussed in this review. Given their association with dysplasia and widespread presence across colonic mucosa, molecular alterations hold significant promise for improving risk stratification beyond current histologic methods. However, at present, the integration of biomarkers into routine surveillance is limited by a lack of high-quality, prospective evidence confirming their predictive accuracy. Histologic evaluation remains the cornerstone for dysplasia detection.

Future research must prioritize the development and validation of biomarker-based risk models in large, longitudinal UC cohorts. These models should aim to identify patients at greatest risk of neoplastic progression and inform surveillance intensity accordingly. We recommend that future studies investigate composite panels incorporating genetic mutations (e.g., TP53), epigenetic changes (e.g., methylation patterns), miRNA signatures, copy number variants, and aneuploidy. Integration with clinical and endoscopic data may enhance predictive performance and facilitate a precision medicine approach to surveillance.

Ultimately, risk-adapted surveillance protocols that incorporate validated biomarkers could reduce unnecessary colonoscopies in low-risk individuals while enabling earlier detection and intervention in those at highest risk. This approach has the potential to improve patient outcomes and optimize resource utilization in inflammatory bowel disease care.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.K., G.K., G.W.; methodology, J.K., G.K., G.W.; investigation, J.K., G.K.; data curation, J.K.; writing—original draft preparation, J.K.; writing—review and editing, G.K., P.L.L., T.B., and G.W.; visualization, J.K.; supervision, G.K., P.L.L., T.B., and G.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the author(s) used ChatGPT 4.0 for the purposes of generating part of figure 2. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| UC |

Ulcerative colitis |

| UC-CRC |

Ulcerative colitis associated colorectal cancer |

| IBD |

Inflammatory bowel disease |

| CRC |

Colorectal cancer |

| ROS |

Reactive oxygen species |

| RNS |

Reactive nitrogen species |

| NGS |

Next generation sequencing |

| IHC |

Immunohistochemistry |

| CNV |

Copy number variation |

| lpWGS |

Low-pass whole genome sequencing |

References

- Ungaro R, Mehandru S, Allen PB, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Colombel JF. Ulcerative colitis. Lancet. 2017;389(10080):1756-1770. [CrossRef]

- Zhang L, Zhang X, Su T, et al. Colorectal cancer risk in ulcerative colitis: an updated population-based systematic review and meta-analysis. eClinicalMedicine. 2025;84:103269. [CrossRef]

- Lutgens MW, van Oijen MG, van der Heijden GJ, Vleggaar FP, Siersema PD, Oldenburg B. Declining risk of colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease: an updated meta-analysis of population-based cohort studies. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19(4):789-799. [CrossRef]

- Huang LC, Merchea A. Dysplasia and Cancer in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Surg Clin North Am. 2017;97(3):627-639. [CrossRef]

- Baker KT, Salk JJ, Brentnall TA, Risques RA. Precancer in ulcerative colitis: the role of the field effect and its clinical implications. Carcinogenesis. 2018;39(1):11-20. [CrossRef]

- Eaden JA, Abrams KR, Mayberry JF. The risk of colorectal cancer in ulcerative colitis: a meta-analysis. Gut. 2001;48(4):526-535. [CrossRef]

- Chen R, Lai LA, Brentnall TA, Pan S. Biomarkers for colitis-associated colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22(35):7882-7891. [CrossRef]

- Scarpa M, Castagliuolo I, Castoro C, et al. Inflammatory colonic carcinogenesis: a review on pathogenesis and immunosurveillance mechanisms in ulcerative colitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(22):6774-6785. [CrossRef]

- Riddell RH, Goldman H, Ransohoff DF, et al. Dysplasia in inflammatory bowel disease: standardized classification with provisional clinical applications. Hum Pathol. 1983;14(11):931-968. [CrossRef]

- Fujii S, Fujimori T, Chiba T, Terano A. Efficacy of surveillance and molecular markers for detection of ulcerative colitis-associated colorectal neoplasia. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38(12):1117-1125. [CrossRef]

- Bernstein CN. Cancer surveillance in inflammatory bowel disease. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 1999;1(6):496-504. [CrossRef]

- Risques RA, Rabinovitch PS, Brentnall TA. Cancer surveillance in inflammatory bowel disease: new molecular approaches. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2006;22(4):382-390. [CrossRef]

- Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):143. Published 2018 Nov 19. [CrossRef]

- Thorsteinsdottir S, Gudjonsson T, Nielsen OH, Vainer B, Seidelin JB. Pathogenesis and biomarkers of carcinogenesis in ulcerative colitis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;8(7):395-404. Published 2011 Jun 7. [CrossRef]

- Romano M, DE Francesco F, Zarantonello L, et al. From Inflammation to Cancer in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Molecular Perspectives. Anticancer Res. 2016;36(4):1447-1460.

- Hisamatsu T, Watanabe M, Ogata H, et al. Interferon-inducible gene family 1-8U expression in colitis-associated colon cancer and severely inflamed mucosa in ulcerative colitis. Cancer Res. 1999;59(23):5927-5931.

- Shah SC, Itzkowitz SH. Colorectal Cancer in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Mechanisms and Management. Gastroenterology. 2022;162(3):715-730.e3. [CrossRef]

- Choi CR, Bakir IA, Hart AL, Graham TA. Clonal evolution of colorectal cancer in IBD. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14(4):218-229. [CrossRef]

- Choi WT, Kővári BP, Lauwers GY. The Significance of Flat/Invisible Dysplasia and Nonconventional Dysplastic Subtypes in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Review of Their Morphologic, Clinicopathologic, and Molecular Characteristics. Adv Anat Pathol. 2022;29(1):15-24. [CrossRef]

- Du L, Kim JJ, Shen J, Chen B, Dai N. KRAS and TP53 mutations in inflammatory bowel disease-associated colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2017;8(13):22175-22186. [CrossRef]

- Itzkowitz SH. Molecular biology of dysplasia and cancer in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2006;35(3):553-571. [CrossRef]

- George NE, Sarojini, Thomas G. Role of immunohistochemical expression of p53 in intestinal epithelial cells to detect dysplasia in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Diagn Res. 2022;16(2):EC26–EC29. [CrossRef]

- Yin J, Harpaz N, Tong Y, Huang Y, Laurin J, Greenwald BD, Hontanosas M, Newkirk C, Meltzer SJ: p53 point mutations in dysplastic and cancerous ulcerative colitis lesions. Gas- troenterology 1993;104:1633–1639.

- Harpaz N, Peck AL, Yin J, Fiel I, Hontanosas M, Tong TR, Laurin JN, Abraham JM, Greenwald BD, Meltzer SJ: p53 protein expression in ulcerative colitis-associated colorectal dysplasia and carcinoma. Hum Pathol 1994;25:1069–1074.

- Brentnall TA, Crispin DA, Rabinovitch PS, Haggitt RC, Rubin CE, Stevens AC, Burmer GC: Mutations in the p53 gene: an early marker of neoplastic progression in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 1994; 107: 369–378.

- Fujii S, Fujimori T, Chiba T: Usefulness of analysis of p53 alteration and observation of surface microstructure for diagnosis of ulcerative colitis-associated colorectal neopla- sia. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2003;22:107–115.

- Hirsch D, Hardt J, Sauer C, et al. Molecular characterization of ulcerative colitis-associated colorectal carcinomas. Mod Pathol. 2021;34(6):1153-1166. [CrossRef]

- Xie H, Xiao SY, Pai R, et al. Diagnostic utility of TP53 and cytokeratin 7 immunohistochemistry in idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease-associated neoplasia. Mod Pathol. 2014;27(2):303-313. [CrossRef]

- Singhi AD, Waters KM, Makhoul EP, et al. Targeted next-generation sequencing supports serrated epithelial change as an early precursor to inflammatory bowel disease-associated colorectal neoplasia. Hum Pathol. 2021;112:9-19. [CrossRef]

- Horvath B, Liu G, Wu X, Lai KK, Shen B, Liu X. Overexpression of p53 predicts colorectal neoplasia risk in patients with inflammatory bowel disease and mucosa changes indefinite for dysplasia. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf). 2015;3(4):344-349. [CrossRef]

- Gerrits MM, Chen M, Theeuwes M, et al. Biomarker-based prediction of inflammatory bowel disease-related colorectal cancer: a case-control study. Cell Oncol (Dordr). 2011;34(2):107-117. [CrossRef]

- Holzmann K, Weis-Klemm M, Klump B, et al. Comparison of flow cytometry and histology with mutational screening for p53 and Ki-ras mutations in surveillance of patients with long-standing ulcerative colitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2001;36(12):1320-1326. [CrossRef]

- Fujii S, Katsumata D, Fujimori T. Limits of diagnosis and molecular markers for early detection of ulcerative colitis-associated colorectal neoplasia. Digestion. 2008;77 Suppl 1:2-12. [CrossRef]

- Heinzlmann M, Lang SM, Neynaber S, et al. Screening for p53 and K-ras mutations in whole-gut lavage in chronic inflammatory bowel disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;1 4(10):1061-1066. [CrossRef]

- Johnson DH, Taylor WR, Aboelsoud MM, et al. DNA Methylation and Mutation of Small Colonic Neoplasms in Ulcerative Colitis and Crohn's Colitis: Implications for Surveillance. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22(7):1559-1567. [CrossRef]

- Moriyama T, Matsumoto T, Nakamura S, et al. Hypermethylation of p14 (ARF) may be predictive of colitic cancer in patients with ulcerative colitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50(9):1384-1392. [CrossRef]

- Ueda Y, Ando T, Nanjo S, Ushijima T, Sugiyama T. DNA methylation of microRNA-124a is a potential risk marker of colitis-associated cancer in patients with ulcerative colitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59(10):2444-2451. [CrossRef]

- Papadia C, Louwagie J, Del Rio P, et al. FOXE1 and SYNE1 genes hypermethylation panel as promising biomarker in colitis-associated colorectal neoplasia. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20(2):271-277. [CrossRef]

- Okugawa Y, Toiyama Y, Yamamoto A, et al. P1-001 - MicroRNA-9 methylation reflect epigenetic drift and identify patients with risk for C-associated colorectal neoplasia. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(Suppl 6):vi118. [CrossRef]

- Beggs AD, Mehta S, Deeks JJ, et al. Validation of epigenetic markers to identify colitis associated cancer: Results of module 1 of the ENDCAP-C study. EBioMedicine. 2019;39:265-271. [CrossRef]

- Okayama H, Schetter AJ, Harris CC. MicroRNAs and inflammation in the pathogenesis and progression of colon cancer. Dig Dis. 2012;30 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):9-15. [CrossRef]

- Tan YG, Zhang YF, Guo CJ, Yang M, Chen MY. Screening of differentially expressed microRNA in ulcerative colitis related colorectal cancer. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2013;6(12):972-976. [CrossRef]

- Barberio B, Borga C, Giada M, Zingone F, Fassan M, Savarino E. P215 Mir-135b, an Early Biomarker of Sporadic and IBD-Related Colorectal Carcinogenetic Progression. Journal of Crohn's and Colitis. 2024;18. i540-i541. [CrossRef]

- Pekow J, Meckel K, Dougherty U, et al. Increased mucosal expression of miR-215 precedes the development of neoplasia in patients with long-standing ulcerative colitis. Oncotarget. 2018;9(29):20709-20720. Published 2018 Apr 17. [CrossRef]

- Kanaan Z, Rai SN, Eichenberger MR, et al. Differential microRNA expression tracks neoplastic progression in inflammatory bowel disease-associated colorectal cancer. Hum Mutat. 2012;33(3):551-560. [CrossRef]

- Bovell L, Shanmugam C, Katkoori VR, et al. miRNAs are stable in colorectal cancer archival tissue blocks. Front Biosci (Elite Ed). 2012;4(5):1937-1940. Published 2012 Jan 1. [CrossRef]

- Salk JJ, Bansal A, Lai LA, et al. Clonal expansions and short telomeres are associated with neoplasia in early-onset, but not late-onset, ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19(12):2593-2602. [CrossRef]

- Shivakumar BM, Chakrabarty S, Rotti H, et al. Comparative analysis of copy number variations in ulcerative colitis associated and sporadic colorectal neoplasia. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:271. Published 2016 Apr 14. [CrossRef]

- Meling GI, Clausen OP, Bergan A, Schjølberg A, Rognum TO. Flow cytometric DNA ploidy pattern in dysplastic mucosa, and in primary and metastatic carcinomas in patients with longstanding ulcerative colitis. Br J Cancer. 1991;64(2):339-344. [CrossRef]

- Rubin CE, Haggitt RC, Burmer GC, et al. DNA aneuploidy in colonic biopsies predicts future development of dysplasia in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 1992;103(5):1611-1620. [CrossRef]

- Löfberg R, Tribukait B, Ost A, Broström O, Reichard H. Flow cytometric DNA analysis in longstanding ulcerative colitis: a method of prediction of dysplasia and carcinoma development?. Gut. 1987;28(9):1100-1106. [CrossRef]

- Reznicek E, Arfeen M, Shen B, Ghouri YA. Colorectal Dysplasia and Cancer Surveillance in Ulcerative Colitis. Diseases. 2021;9(4):86. Published 2021 Nov 19. [CrossRef]

- Rebello D, Rebello E, Custodio M, Xu X, Gandhi S, Roy HK. Field carcinogenesis for risk stratification of colorectal cancer. Adv Cancer Res. 2021;151:305-344. [CrossRef]

- Kornbluth A, Sachar DB; Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Ulcerative colitis practice guidelines in adults: American College Of Gastroenterology, Practice Parameters Committee [published correction appears in Am J Gastroenterol. 2010 Mar;105(3):500]. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(3):501-524. [CrossRef]

- East JE, Gordon M, Nigam GB, et al. British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines on colorectal surveillance in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. Published Online First: 30 April 2025. [CrossRef]

- Gordon H, Biancone L, Fiorino G, et al. ECCO Guidelines on Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Malignancies. J Crohns Colitis. 2023;17(6):827-854. https://doi.org/10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjac187Iannone A, Ruospo M, Wong G, et al. Chromoendoscopy for Surveillance in Ulcerative Colitis and Crohn's Disease: A Systematic Review of Randomized Trials. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15(11):1684-1697.e11. [CrossRef]

- Eaden JA, Ward BA, Mayberry JF. How gastroenterologists screen for colonic cancer in ulcerative colitis: an analysis of performance. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;51(2):123-128. [CrossRef]

- Al Bakir I, Curtius K, Cresswell GD, et al. Low-coverage whole genome sequencing of low-grade dysplasia strongly predicts advanced neoplasia risk in ulcerative colitis. Gut. 2025;74(5):740-751. Published 2025 Apr 7. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).