1. Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) remains as one of the most devastatingly formidable global health challenge that substantially contributes to cancer incidence and mortality rates worldwide (1). It is currently the third most diagnosed malignancy and a leading cause of cancer-related deaths globally, imposing a considerable economic strain on health care systems due to treatment costs and productivity loss (2). The pathogenesis of CRC is a complex multifactorial process influenced by an intricate interplay of genetic predisposition, dietary and environmental factors, and chronic inflammatory conditions (3). Genetic susceptibility and predispositions play a critical role in the development of CRC. Inherited mutations in key regulatory genes such as APC, KRAS, and TP53 have been well-documented to elevate the risk of colorectal neoplasia (4, 5). Furthermore, hereditary syndromes like Lynch syndrome and Familial Adenomatous Polyposis (FAP), which arise from germline mutations in DNA mismatch repair genes or the APC gene respectively, account for a clinically significant portion of inherited CRC cases (6). Identifying these genetic risk factors is paramount for implementing targeted genetic screening and early intervention strategies in high-risk individuals and their families, thereby potentially mitigating disease burden (7).Dietary habits also have a profound impact on modulating CRC risk. Consistent epidemiological evidence links high consumption of red and processed meats to an increased likelihood of developing CRC, potentially due to exposure to carcinogenic compounds formed during high-temperature cooking or meat processing (8, 9). Conversely, diets abundant in dietary fiber, fruits, and vegetables are associated with a demonstrable protective effect against CRC (10, 11). Furthermore, adequate intake of micronutrients such as calcium and vitamin D has been suggested to reduce CRC incidence, highlighting the potential of dietary modifications as a cornerstone of primary prevention strategies (12). Chronic inflammation within the gastrointestinal tract, particularly in the context of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), significantly elevates the long-term risk of colitis-associated cancer (13). The persistent inflammatory microenvironment can drive cumulative cellular damage and promote various stages of tumorigenesis. Emerging research also underscores the critical role of the gut microbiota in maintaining colonic health and influencing disease pathogenesis. Specific bacterial species, such as Fusobacterium nucleatum, have been implicated in promoting colorectal carcinogenesis through diverse mechanisms, including the modulation of the tumor microenvironment and host immune responses (14). This evolving understanding suggests that therapeutic strategies targeting chronic inflammation and dysbiotic gut microbial communities could represent viable avenues for CRC prevention and adjunctive therapy (15).

In light of these pathogenic mechanisms, effective screening and early detection remain pivotal in reducing CRC-associated mortality. Colonoscopy is currently a cornerstone for CRC screening, uniquely allowing for both the detection and contemporaneous removal of precancerous adenomatous polyps, thereby interrupting the well-defined adenoma-carcinoma sequence (16). The systematic implementation of regular screening programs has been shown to decrease both the incidence and mortality of CRC significantly in screened populations (17). Concurrently, non-invasive screening methods, such as fecal immunochemical tests (FIT) and stool-based DNA tests, offer valuable alternatives that can enhance screening uptake and adherence across diverse populations (18).

Beyond classical CRC, a spectrum of colonic and intero-colonic disorders, including those potentially influenced by genetic mosaicism where different cell populations within colonic tissue harbor distinct genetic alterations, contribute to gastrointestinal pathology (19). Such genetic heterogeneity can manifest in a wide array of clinical presentations and diverse pathological features, often posing considerable diagnostic challenges (20). Understanding the local epidemiology of these conditions, including their prevalence and distribution within specific populations, is crucial for developing tailored and effective diagnostic and management pathways. This is particularly relevant in regions such as Saudi Arabia, where CRC incidence has been reportedly increasing, with some studies noting a concerning rise in early-onset cases, underscoring the urgent need for robust local data to inform and optimize public health strategies (21-23).

Given the multifaceted nature of colonic disorders and the imperative for region-specific data, this study was undertaken to characterize the epidemiological landscape within a defined patient cohort. Specifically, we aimed to determine the prevalence rates of various colonic and intero-colonic disorders, assess their distribution across key demographic variables such as age and gender, and identify common gastrointestinal pathological features alongside the diagnostic approaches utilized. Furthermore, this investigation sought to explore the associations between patients’ clinical histories, definitive diagnostic findings, and demographic characteristics to delineate clinically relevant implications for improving diagnosis and management strategies in this setting.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This investigation utilized a retrospective observational clinical design, involving the analysis of electronic health records from patients managed between January 2020 and December 2024 Ha’il region, Saudi Arabia This approach facilitated the examination of real-world clinical data pertaining to the epidemiology, diagnostic features, and pathological characteristics associated with a spectrum of colonic and intero-colonic disorders.

2.2. Population and Sampling

The study population comprised 602 individuals whose medical records were available and met the inclusion criteria during the specified study period. Participants were selected from patients who underwent evaluation or treatment for suspected or confirmed colonic disorders at a single, large high-capacity tertiary care hospital. Inclusion criteria stipulated patients to be aged 10 years or older, with documented diagnostic procedures (e.g., colonoscopy, biopsy) and histopathological confirmation of relevant conditions. Records with substantially incomplete data on key diagnostic or demographic variables were excluded. The sampling method involved a review of all accessible patient data from the participating hospital, representing a consecutive series of eligible patients who presented during the study timeframe.

2.3. Data Collection Methods

Data were systematically collected through a comprehensive retrospective review of existing electronic medical records and corresponding histopathology reports. A standardized data extraction form was developed and pilot-tested to ensure consistency and reliability in data collection. The following variables were extracted:

2.4. Demographic Information:

Age at diagnosis (categorized into four age groups: 15-29, 30-49, 50-69, and 70-89 years for age-specific analysis, and dichotomized as 10-49 vs 50-89 years for broader age comparisons) and gender (male/female).

2.5. Diagnostic Information

Final diagnosis categorized as Adenocarcinoma, Tubulovillous Adenoma with dysplasia, Dysplasia (not otherwise specified), Chronic active colitis, No malignancy (normal findings or benign non-neoplastic conditions), Polyps (not otherwise specified, or other benign polyp types), and Differential diagnosis (cases in which a definitive single diagnosis was not reached or multiple possibilities were considered).

2.6. Biopsy and Specimen Information

The type of specimen obtained for diagnostic purposes was recorded and primarily categorized as Colon biopsy (biopsies taken from various parts of the colon excluding the rectosigmoid junction specifically), Rectosigmoid biopsy (biopsies specifically from the rectum and/or sigmoid colon), and Liver biopsy (in cases of suspected metastasis).

2.7. Clinical History

Relevant clinical presentations or historical factors recorded, including presence of colon tumor or polyps, rectosigmoid polyp, abdominal pain/diarrhea/gastritis, chronic bloody diarrhea, endoscopic differentiation features, history of epiploic appendicitis, documented gastrointestinal (GIT) cancer, presence of liver lesions, previous history of lesions with routine follow-up, recurrent peri-anal fistula for IBD, and ulcerative colitis.

2.8. Histopathological Examination

Histopathological diagnoses were based on reports generated by consultant histopathologists following standard institutional laboratory protocols. These typically involved macroscopic examination of specimens, tissue processing (formalin fixation, paraffin embedding, and sectioning), Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) staining, and subsequent microscopic evaluation. Key diagnostic features were assessed according to established pathological criteria including: Adenocarcinoma (e.g., glandular architecture, nuclear atypia, invasion), adenomas with dysplasia (e.g., villous/tubulovillous architecture, degree of dysplasia), and colitis (e.g., inflammatory infiltrates, crypt distortion).

2.9. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics (version 23, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics (frequencies and percentages) were used to summarize the demographic profile of the cohort, as well as the distribution of final diagnoses, biopsy types, and clinical histories. For inferential analysis, associations between categorical variables (e.g., gender and diagnosis, diagnosis and specimen type, clinical history and diagnosis) were assessed using Pearson’s Chi-square (χ²) test or Fisher’s exact test when expected cell counts were less than 5. Effect sizes for binary comparisons were expressed as odds ratios (ORs) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) where applicable. To assess differences in diagnosis distribution between the two broad age groups (10–49 years vs. 50–89 years), the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test was used. A two-tailed p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

2.10. Ethical Considerations

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University (Approval No.H2024-491) and the local Health Cluster Ethics Committee (Approval No. HHC H2024-120). The research was conducted in full accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Given the retrospective nature of the study, the confidentiality of patient data was strictly maintained. All data were anonymized by removing direct personal identifiers prior to analysis. Access to the de-identified dataset was restricted to authorized research personnel and stored securely.

3. Results

3.1. Cohort Demographics and Age-Specific Prevalence of Colonic Disorders

The study cohort included 602 patients, with a predominance of males (n=357; 59.3%) compared to females (n=245; 40.7%) (

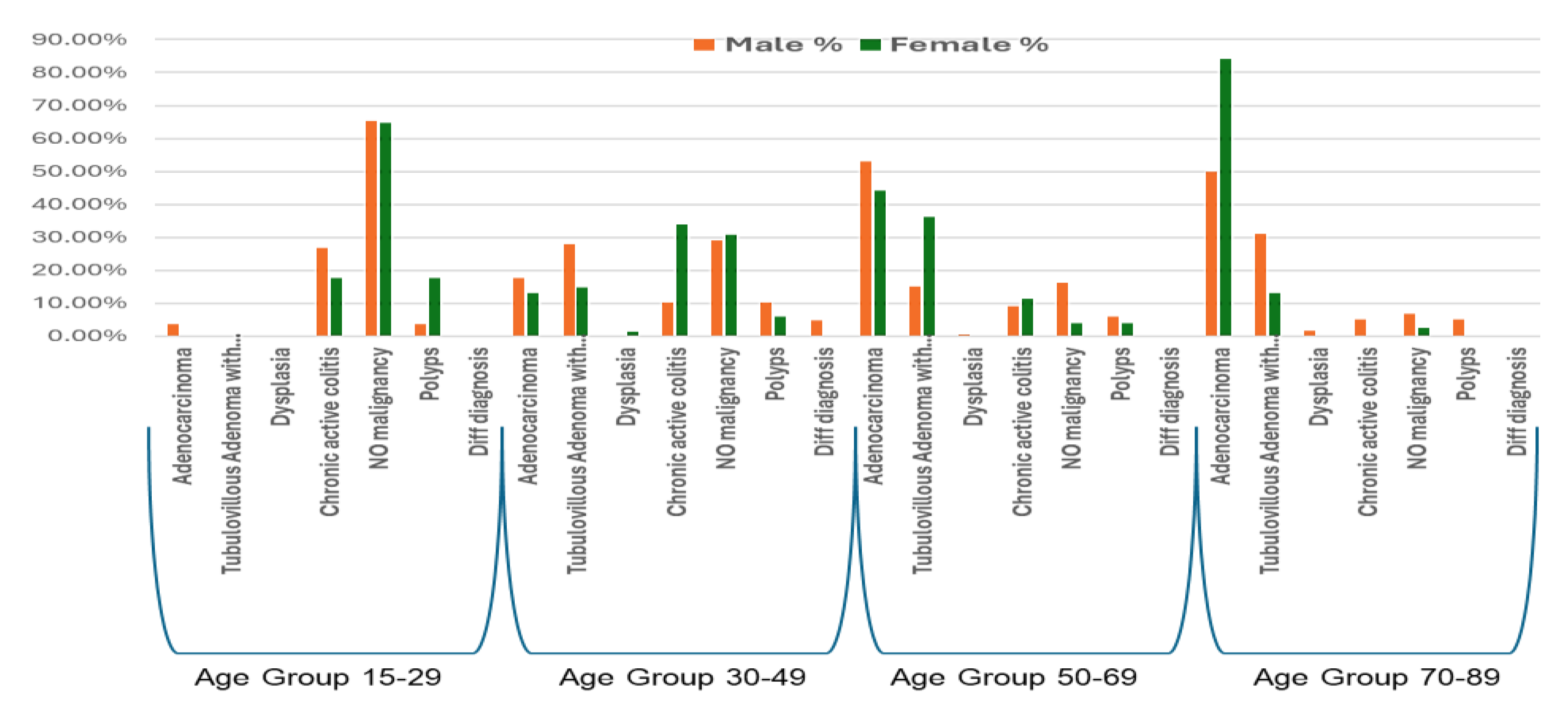

Table 1, upper panel). The prevalence and types of colonic disorders demonstrated distinct patterns across age groups and between genders.In the youngest age group (15-29 years), “No malignancy” was the most frequent finding in both males (65.4%) and females (64.7%). Chronic active colitis was also prominent, identified in 26.9% of males and 17.6% of females. Adenocarcinoma was rare in this age bracket, occurring in 3.8% of males (

n = 1) and not observed in females. Polyps were detected in 3.8% of males and 17.6% of females (

Table 1;

Figure 1).

Among individuals aged 30-49 years, “Tubulovillous Adenoma with dysplasia” was a prominent diagnosis in males (28.0%), whereas “Chronic active colitis” was the most common finding in females (33.8%). “No malignancy” remained a frequent observation in both sexes (males: 29.0%; females: 30.9%). Adenocarcinoma was diagnosed in 17.8% of males and 13.2% of females within this age group. A marked shift towards neoplastic conditions was observed in the 50-69 age group. Adenocarcinoma emerged as the most common diagnosis in males (53.0%) and remained highly prevalent among females (44.3%). “Tubulovillous Adenoma with dysplasia” was also frequently identified, accounting for 15.1% of diagnoses in males and a notable 36.1% in females within this age range. As a result, the proportion of “No malignancy” declined substantially in both sexes.

In the oldest age group (70-89 years), Adenocarcinoma was the overwhelmingly predominant diagnosis, particularly among females, where it accounted 84.2% of all findings within this age group, compared to 50.0% in males. “Tubulovillous Adenoma with dysplasia” remained a notable diagnosis, present in 31.0% of males and 13.2% of females. Other conditions such as chronic active colitis and “No malignancy” were infrequently reported in this age group for both sexes. Differential diagnoses were generally rare across all age groups and genders (

Table 1;

Figure 1).

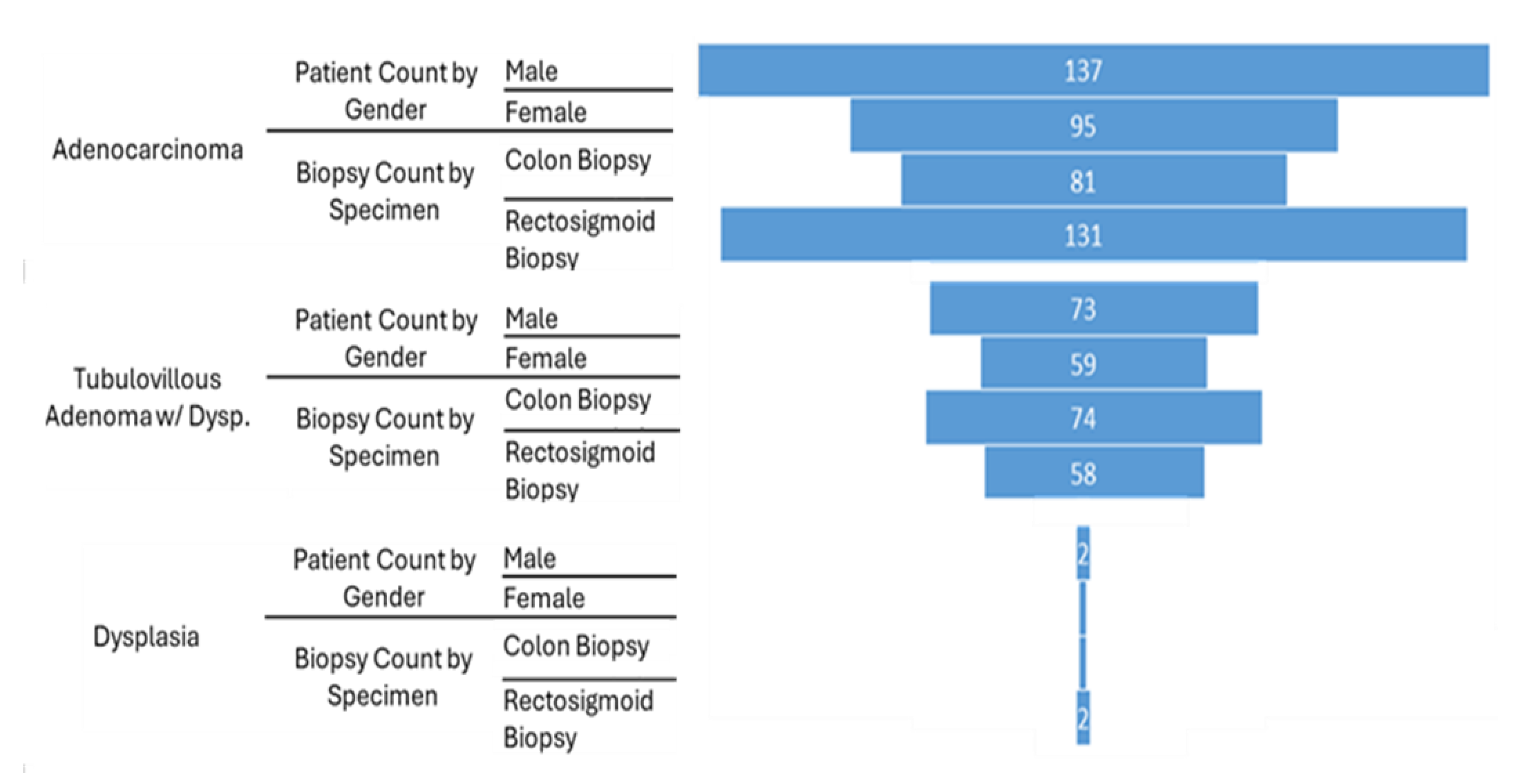

3.2. Overall Gender-Specific Distribution of Dominant Neoplastic Colonic Disorders

Analysis of the overall prevalence of major neoplastic colonic disorders, revealed distinct gender-based patterns across the entire cohort (Figure 2). Adenocarcinoma was more frequently diagnosed in male patients (n=137) compared to female patients (n=95). Similarly, Tubulovillous adenoma with dysplasia was observed more often in males (n=73) than in females (n=59). Dysplasia (not otherwise specified),was infrequent overall but showed a slightly higher count in males (n=2) compared to females (n=1).

3.3. Gender Distribution and Biopsy Specimen Types for Dominant Neoplastic Colonic Diagnoses

We further examined the gender distribution and biopsy types associated with major neoplastic colonic diagnoses (Figure 2). The aim was to identify sex-based differences in the prevalence of these conditions and to infer the common anatomical sites from which these pathologies were diagnosed, thereby reflecting typical diagnostic practices within the studied cohort. For Adenocarcinoma, a greater number of male patients (n=137) were diagnosed compared to female patients (n=95). In terms of the diagnostic approach for Adenocarcinoma, rectosigmoid biopsy was more frequently employed (n=131) than colon biopsy (n=81).

A similar pattern in gender distribution was observed for Tubulovillous Adenoma with dysplasia, with 73 male patients and 59 female patients receiving this diagnosis. To establish this diagnosis, colon biopsy was utilized slightly more frequently (n = 74) than rectosigmoid biopsy (n=58). Dysplasia (not otherwise specified),remained rare, with only two cases in male patients and one case in a female patient. Rectosigmoid biopsy was used in two of these cases, while colon biopsy was used in one (Figure 2).

3.4. Distribution of Biopsy Specimen Types Across Colonic Diagnoses

The biopsy specimens types used to establish definitive diagnoses varied across the spectrum of colonic disorders observed in the cohort (

Table 2). For Adenocarcinoma, rectosigmoid biopsy was the most commonly employed modality, accounting for 42.4% (n=131) of cases in which biopsy type was specified, followed by colon biopsy at 29.7% (n=81). Liver biopsy was performed in 17 cases of Adenocarcinoma, presumably for staging of suspected metastatic disease. For tubulovillous adenoma with dysplasia, colon biopsy was the primary diagnostic method (27.1%, n=74), while rectosigmoid biopsy accounted for 18.8% (n=58). Dysplasia(not otherwise specified), was infrequent and diagnosed through rectosigmoid biopsy in 0.6% (n=2) and colon biopsy in 0.4% (n=1) of cases. Among non-neoplastic conditions, chronic active colitis was equally diagnosed using colon biopsy (13.9%, n=38) and rectosigmoid biopsy (12.3%, n=38). No malignancy was most commonly associated with rectosigmoid biopsy (22.0%, n=68), followed by colon biopsy (17.9%, n=49). Polyps were identified more often through colon biopsy (9.2%, n=25) than rectosigmoid biopsy (3.9%, n=12). Differential diagnoses were primarily informed by colon biopsy (1.8%, n=5).

3.5. Association of Clinical Histories with Colonic Diagnoses

The clinical histories of patients showed variable associations with the final colonic diagnoses (

Table 3). A history of “Colon tumor or polyps” was most strongly linked to a diagnosis of Adenocarcinoma (47.0% of patients with this history), followed by Tubulovillous Adenoma with dysplasia (30.3%). Similarly, a history of “Rectosigmoid polyp” was predominantly associated with Adenocarcinoma (54.8%) and Tubulovillous Adenoma with dysplasia (25.8%). Patients presenting with symptoms of “Abdominal pain, diarrhea, or gastritis” most frequently received a diagnosis of chronic active colitis (28.3%), followed by adenocarcinoma (24.5%) and No malignancy (22.6%). A history of “Chronic bloody diarrhea” was a strong indicator for Chronic active colitis, with 50.0% of patients with this symptom receiving this diagnosis, while 28.0% were found to have No malignancy and 10.0% had Adenocarcinoma. Findings of “Endoscopic differentiation” were most often associated with No malignancy (45.2%) or Chronic active colitis (32.3%). A history of “Epiploic appendicitis” was exclusively linked to a final diagnosis of No malignancy (100.0%). Similarly, a documented “GIT cancer” history was entirely associated with a diagnosis of Adenocarcinoma (100.0%).

The presence of a “Liver lesion” in the clinical history was strongly associated with Adenocarcinoma (94.1%). A “Previous history lesion/routine follow-up” was most commonly linked to a finding of No malignancy (82.4%), with a smaller proportion having Tubulovillous Adenoma with dysplasia (11.8%).

Histories related to IBD showed specific patterns. “Recurrent peri-anal fistula for IBD” was primarily associated with No malignancy (85.7%) and Chronic active colitis (14.3%). A history of “Ulcerative colitis” was most frequently linked to NO malignancy (52.6%) and Chronic active colitis (42.1%) (

Table 3).

3.6. Statistical Analyses of Associations

Statistical tests were performed to evaluate associations between various factors and colonic diagnoses (

Table 4). A Mann-Whitney U test comparing the overall distribution of diagnostic categories between genders yielded a U value of 6507.5 (Wilcoxon W = 11067.5, Z-score = 0). Regarding the diagnostic approach for Adenocarcinoma, rectosigmoid biopsy was more frequently utilized (n=131, 61.8% of adenocarcinoma biopsies) than colon biopsy (n=81, 38.2%).

Chi-square tests indicated statistically significant associations. The Pearson Chi-Square test assessing the relationship between diagnosis and another categorical variable yielded a value of 57.849 (df=18, p < 0.001). The Likelihood Ratio test produced a value of 65.902 (df=18, p < 0.001), and the Linear-by-Linear Association test resulted in a value of 20.354 (df=1, p < 0.001). These results suggest strong, significant relationships between the variables tested. All analyses were based on 602 valid cases.

3.7. Association of Clinical Histories with Tubulovillous Adenoma with Dysplasia and Dysplasia

The association between specific clinical histories and the diagnoses of Tubulovillous Adenoma with dysplasia and Dysplasia was examined (

Table 5). Among patients diagnosed with Tubulovillous Adenoma with dysplasia ( n=132), the most frequently associated clinical history was “colon tumor or polyps,” reported in 92 cases. Other associated histories included “rectosigmoid polyp” (24 cases), and “Abdominal pain, diarrhea, or gastritis” (8 cases), “Endoscopic differentiation” (4 cases), and both “Chronic bloody diarrhea” and “previous history lesion and routine follow up” (2 cases each). Histories of “Epiploic appendicitis,” “GIT cancer,” “Liver lesion,” “Recurrent peri-anal fistula for IBD,” and “Ulcerative colitis” were not reported in association with a diagnosis of Tubulovillous Adenoma with dysplasia in this subset. Among the few patients diagnosed with Dysplasia (n=3), clinical histories included “colon tumor or polyps” (1 case), “rectosigmoid polyp” (1 case), and “Liver lesion” (1 case). No other listed clinical histories were associated with Dysplasia in this group (

Table 5).

4. Discussion

This study provides a unique snapshot on the local epidemiological and clinical landscape of colonic and intero-colonic disorders within a tertiary care setting in the Ha’il region of Saudi Arabia region, highlighting key demographic and diagnostic patterns. The findings emphasize the substantial burden of neoplastic conditions, particularly adenocarcinoma and its precursors, and reveal distinct age and gender-related variations in their prevalence.

The observed male predominance in the overall cohort (59.3%), particularly in diagnoses such as adenocarcinoma and tubulovillous adenoma with dysplasia, is consistent with broader epidemiological trends for colorectal cancer, where males typically exhibit higher incidence rates than females (1). Hormonal influences in females—such as the potential protective role of estrogen— have been postulated to offer some protective effects, potentially delaying the onset or reducing the risk of CRC, though the underlying mechanisms remain complex and not fully understood (24). In addition, gender-related lifestyle factors, including differences in dietary habits, tobacco use, and alcohol consumption, may contribute to the disparities observed (25).

The strong association between increasing age and the prevalence of adenocarcinoma and tubulovillous adenoma with dysplasia is a well- established phenomenon (26). Our findings this trend, with the 50-69 and 70-89 year age groups showing the highest rates of these neoplastic conditions in both males and females. This age-dependent increase is attributed to the progressive accumulation of genetic and epigenetic alterations over time, in conjunction with prolonged exposure to environmental risk factors, which drive the multi-step process of colorectal carcinogenesis (27-29).

The marked difference in diagnostic profiles between younger (10-49 years) and older (50-89 years) patients in our cohort further emphasizes this age-related shift towards malignancy. This observation reinforces the rationale behind current age-based CRC screening guidelines, which typically recommend initiating screening at age 45 or 50 for individuals at average risk. According to established clinical guidelines, routine screening is advised for all adults aged 50 to 75 years, with the option to begin at age 45 based on individual risk factors and patient preference (30). However, the notable presence of tubulovillous adenoma with dysplasia in the 30-49 age group, particularly in males, warrants attention and aligns with regarding the increasing indidence of early-onset CRC (31).

The distribution of biopsy sites provided valuable insights into the anatomical locations of diagnosed pathologies within our cohort. Rectosigmoid biopsies were frequently used for diagnosing adenocarcinoma accounting for 42.4% of cases where biopsy type was specified. This suggests that a considerable proportion of tumors were located in the distal colon and rectum- regions that are more accessible via sigmoidoscopy or may present with symptoms prompting distal examination. This finding is consistent with historical data (32), although a proximal shift in CRC location has been reported in other populations, potentially due to the increased use of screening colonoscopy (33, 34). In contrast, our results indicated that tubulovillous adenomas with dysplasia were more commonly diagnosed via colon biopsy (27.1% of these adenoma diagnoses from colon vs. 18.8% from rectosigmoid biopsies). This difference may reflect the typical anatomical distribution of these precursor lesions or their detection during full colonoscopy procedures performed for comprehensive screening or investigation. The choice of biopsy site and technique is inherently guided by endoscopic findings. Our results showed a significant association between final diagnosis and specimen type, reflecting the targeted nature of biopsies taken from suspicious lesions. Furthermore, the exclusive use of liver biopsies in adenocarcinoma cases underscores the importance of investigating for metastatic disease in this context, a critical component of staging and subsequent treatment planning.

The strong correlation between patients’ clinical histories and their final diagnoses highlights the diagnostic value of comprehensive clinical assessment. For instance, a history of colon tumor or polyps was, as anticipated, frequently linked to findings of adenocarcinoma or tubulovillous adenoma with dysplasia. Similarly, symptoms such as chronic bloody diarrhea were strongly indicative of chronic active colitis. These associations emphasize the importance of symptom evaluation and medical history in guiding endoscopic investigation and risk stratification (35, 36).

Our study also identified a notable prevalence of chronic active colitis, particularly among younger patients aged 30-49 years in both sexes. Chronic intestinal inflammation, as seen in IBD, is a well-established risk factor for CRC (13, 37). While our data do not specify the etiology of colitis in all cases, its presence necessitates appropriate clinical management and long-term surveillance due to the associated increased long-term cancer risk.

The predominance of “No malignancy” diagnosis in the youngest age groups (15-29 years) is reassuring, suggesting that while gastrointestinal symptoms in younger individuals often prompt investigation, serious pathology is less frequently encountered. Nonetheless, the presence of polyps across various age groups emphasizes the importance of polypectomy as a key preventive measure against CRC, given that adenomatous polyps are well-established precursors (38, 39). Adherence to established surveillance guidelines following polypectomy is essential for effective risk management and early detection of potential malignant transformation (40, 41).

This study, although provides significant insights, albeit has certain limitations that can be mitigated in future works. Its retrospective design inherently relies on the accuracy and completeness of existing medical records. Data on specific genetic mutations (e.g., KRAS, BRAF, MSI status for adenocarcinoma cases), as well as detailed lifestyle factors (including dietary patterns, smoking intensity, and physical activity), were not systematically available. Similarly, comprehensive family history data were incomplete, limiting the ability to explore these predisposing factors. Additionally, the study was conducted at a single tertiary care center, which may introduce selection bias, and the findings may not be generalizable to the broader population or other healthcare settings. The inclusion of a “Differential diagnosis” category also reflects some degree of diagnostic uncertainty in a small subset of cases.

Despite these limitations, the findings of this study offer valuable advances in the regional progress about the burden and characteristics of colonic disorders. The observed age and gender-specific patterns, the diagnostic utility of various biopsy approaches, and the strong associations between clinical history and pathological outcomes reinforce many established principles in gastroenterology and oncology. These findings also highlight the ongoing importance of endoscopic surveillance and highlight the need for vigilance regarding neoplastic precursors, even among relatively younger adults.

5. In Conclusions

This study delineates the epidemiological and clinicopathological spectrum of colonic disorders in a large cohort from a tertiary hospital. Adenocarcinoma and its precursors are prevalent, particularly among older males, with rectosigmoid biopsy serving as a common diagnostic modality. These findings support current practices of age-based screening and underscore the importance of comprehensive clinical and pathological assessment in the management of colonic disorders. Further research is warranted to invistigate specific risk factors and the molecular landscapes of these conditions within the local population, with the goal of refining prevention, early detection, and treatment strategies.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Blank form of informed consent was uploaded along with the manuscript. All data from this study was included in the manuscript and not available anywhere else.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Kamaleldin B Said; Data curation, Kamaleldin B Said, Khalid F. Alshammari, Ruba Elsaid Ahmed, Ahmed Aljadani, Ahmed Alsolami, Yosef Zakout, Soha Moursi, Naif Binsaleh, Fahad Alshammary, Arwa Alotaibi, Mohammad. Alzugahibi, Manal IAlshammari, Fayez Alfouzan, Zaid Albayih, Nutilla Osman and Nafea Alshammary; Formal analysis, Kamaleldin B Said, Khalid F. Alshammari, Ruba Elsaid Ahmed, Ahmed Aljadani, Ahmed Alsolami, Yosef Zakout, Soha Moursi, Naif Binsaleh, Fahad Alshammary, Arwa Alotaibi, Mohammad . Alzugahibi, Manal IAlshammari, Fayez Alfouzan, Zaid Albayih, Nutilla Osman and Nafea Alshammary; Funding acquisition, Kamaleldin B Said; Investigation, Kamaleldin B Said; Methodology, Kamaleldin B Said, Khalid F. Alshammari, Ruba Elsaid Ahmed, Ahmed Aljadani, Ahmed Alsolami, Yosef Zakout, Soha Moursi, Naif Binsaleh, Fahad Alshammary, Arwa Alotaibi, Mohammad . Alzugahibi, Manal IAlshammari, Fayez Alfouzan, Zaid Albayih, Nutilla Osman and Nafea Alshammary; Project administration, Kamaleldin B Said and Khalid F. Alshammari; Resources, Kamaleldin B Said, Khalid F. Alshammari, Ruba Elsaid Ahmed, Ahmed Aljadani, Ahmed Alsolami, Yosef Zakout, Soha Moursi, Naif Binsaleh, Fahad Alshammary, Arwa Alotaibi, Mohammad . Alzugahibi, Manal IAlshammari, Fayez Alfouzan, Zaid Albayih, Nutilla Osman and Nafea Alshammary; Software, Kamaleldin B Said, Khalid F. Alshammari, Ruba Elsaid Ahmed, Ahmed Aljadani, Ahmed Alsolami, Yosef Zakout, Soha Moursi, Naif Binsaleh, Fahad Alshammary, Arwa Alotaibi, Mohammad . Alzugahibi, Manal IAlshammari, Fayez Alfouzan, Zaid Albayih, Nutilla Osman and Nafea Alshammary; Supervision, Kamaleldin B Said; Validation, Kamaleldin B Said, Khalid F. Alshammari, Ruba Elsaid Ahmed, Ahmed Aljadani, Ahmed Alsolami, Yosef Zakout, Soha Moursi, Naif Binsaleh, Fahad Alshammary, Arwa Alotaibi, Mohammad . Alzugahibi, Manal IAlshammari, Fayez Alfouzan, Zaid Albayih, Nutilla Osman and Nafea Alshammary; Visualization, Kamaleldin B Said, Khalid F. Alshammari, Ruba Elsaid Ahmed, Ahmed Aljadani, Ahmed Alsolami, Yosef Zakout, Soha Moursi, Naif Binsaleh, Fahad Alshammary, Arwa Alotaibi, Mohammad . Alzugahibi, Manal IAlshammari, Fayez Alfouzan, Zaid Albayih, Nutilla Osman and Nafea Alshammary; Writing—original draft, Kamaleldin B Said; Writing—review & editing, Kamaleldin B Said, Khalid F. Alshammari, Ruba Elsaid Ahmed, Ahmed Aljadani, Ahmed Alsolami, Yosef Zakout, Soha Moursi, Naif Binsaleh, Fahad Alshammary, Arwa Alotaibi, Mohammad . Alzugahibi, Manal IAlshammari, Fayez Alfouzan, Zaid Albayih, Nutilla Osman and Nafea Alshammary.

Funding

“This research was funded by this research has been funded by Scientific Research, Deanship at University of Hail, Saudi Arabia through project number GR-25 005.

Institutional Review Board Statement

“The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board and Ethics Committee for studies involving humans. The Research Ethical Committee (REC) of University of Ha’il, Saudi Arabia, has Approved this research by the number (H-2024-941), dated REC 4112024. In addition, IRB Approval (Log 2024-120, Dec 2024) was obtained from Ha’il Health Cluster, Ha’il to perform this work.

Informed Consent Statement

“Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.” Empty informed consent form in uploaded with this manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

All data created from this study is included in the manuscript and not available anywhere else.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Deanship of Scientific Research and graduate studies at the University of Ha’il. This research has been funded by Scientific Research Deanship at University of Hail, Saudi Arabia through project number GR-25 005.

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflicts of interest.”

References

- Morgan E, Arnold M, Gini A, Lorenzoni V, Cabasag CJ, Laversanne M, et al. Global burden of colorectal cancer in 2020 and 2040: incidence and mortality estimates from GLOBOCAN. Gut. 2023;72(2):338-44.

- Schlesinger S, Siegert S, Koch M, Walter J, Heits N, Hinz S, et al. Postdiagnosis body mass index and risk of mortality in colorectal cancer survivors: a prospective study and meta-analysis. Cancer Causes Control. 2014;25(10):1407-18.

- Lewandowska A, Rudzki G, Lewandowski T, Stryjkowska-Góra A, Rudzki S. Risk Factors for the Diagnosis of Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Control. 2022;29:10732748211056692.

- Stoffel EM, Yurgelun MB. Genetic predisposition to colorectal cancer: Implications for treatment and prevention. Semin Oncol. 2016;43(5):536-42.

- Rebuzzi F, Ulivi P, Tedaldi G. Genetic Predisposition to Colorectal Cancer: How Many and Which Genes to Test? Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(3).

- Mao R, Krautscheid P, Graham RP, Ganguly A, Shankar S, Ferber M, et al. Genetic testing for inherited colorectal cancer and polyposis, 2021 revision: a technical standard of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). Genet Med. 2021;23(10):1807-17.

- Kim HM, Kim TI. Screening and surveillance for hereditary colorectal cancer. Intest Res. 2024;22(2):119-30.

- Chan DS, Lau R, Aune D, Vieira R, Greenwood DC, Kampman E, et al. Red and processed meat and colorectal cancer incidence: meta-analysis of prospective studies. PLoS One. 2011;6(6):e20456.

- Farvid MS, Sidahmed E, Spence ND, Mante Angua K, Rosner BA, Barnett JB. Consumption of red meat and processed meat and cancer incidence: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur J Epidemiol. 2021;36(9):937-51.

- Hidaka A, Harrison TA, Cao Y, Sakoda LC, Barfield R, Giannakis M, et al. Intake of Dietary Fruit, Vegetables, and Fiber and Risk of Colorectal Cancer According to Molecular Subtypes: A Pooled Analysis of 9 Studies. Cancer Res. 2020;80(20):4578-90.

- Song Y, Liu M, Yang FG, Cui LH, Lu XY, Chen C. Dietary fibre and the risk of colorectal cancer: a case- control study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16(9):3747-52.

- Cruz-Pierard SM, Nestares T, Amaro-Gahete FJ. Vitamin D and Calcium as Key Potential Factors Related to Colorectal Cancer Prevention and Treatment: A Systematic Review. Nutrients. 2022;14(22).

- Sato Y, Tsujinaka S, Miura T, Kitamura Y, Suzuki H, Shibata C. Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Colorectal Cancer: Epidemiology, Etiology, Surveillance, and Management. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15(16).

- Zhang Y, Zhang L, Zheng S, Li M, Xu C, Jia D, et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum promotes colorectal cancer cells adhesion to endothelial cells and facilitates extravasation and metastasis by inducing ALPK1/NF-κB/ICAM1 axis. Gut Microbes. 2022;14(1):2038852.

- Fong W, Li Q, Yu J. Gut microbiota modulation: a novel strategy for prevention and treatment of colorectal cancer. Oncogene. 2020;39(26):4925-43.

- Azer, SA. Challenges Facing the Detection of Colonic Polyps: What Can Deep Learning Do? Medicina (Kaunas). 2019;55(8).

- Cardoso R, Guo F, Heisser T, Hackl M, Ihle P, De Schutter H, et al. Colorectal cancer incidence, mortality, and stage distribution in European countries in the colorectal cancer screening era: an international population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(7):1002-13.

- Robertson DJ, Imperiale TF. Stool Testing for Colorectal Cancer Screening. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(5):1286-93.

- Jansen AML, Goel A. Mosaicism in Patients With Colorectal Cancer or Polyposis Syndromes: A Systematic Review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(9):1949-60.

- Molinari C, Marisi G, Passardi A, Matteucci L, De Maio G, Ulivi P. Heterogeneity in Colorectal Cancer: A Challenge for Personalized Medicine? Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(12).

- Alessa AM, Khan AS. Epidemiology of Colorectal Cancer in Saudi Arabia: A Review. Cureus. 2024;16(7):e64564.

- Alsiary R, Aboalola D, Alsolami M, Alsaiari T, Ramadan M. Early-Onset Colorectal Cancer Survival among Unscreened Population -Multicenter Cohort Retrospective Analysis. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2023;24(4):1225-30.

- Basudan AM, Basuwdan AM, Abudawood M, Farzan R, Alfhili MA. Comprehensive Retrospective Analysis of Colorectal Cancer Incidence Patterns in Saudi Arabia. Life (Basel). 2023;13(11).

- Johnson JR, Lacey JV, Jr., Lazovich D, Geller MA, Schairer C, Schatzkin A, et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and risk of colorectal cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(1):196-203.

- Conti L, Del Cornò M, Gessani S. Revisiting the impact of lifestyle on colorectal cancer risk in a gender perspective. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2020;145:102834.

- Kusnik A, Renjithlal SLM, Chodos A, Shanmukhappa SC, Eid MM, Renjith KM, et al. Trends in Colorectal Cancer Mortality in the United States, 1999 - 2020. Gastroenterology Res. 2023;16(4):217-25.

- Daniel M, Tollefsbol TO. Epigenetic linkage of aging, cancer and nutrition. Journal of Experimental Biology. 2015;218(1):59-70.

- Thomas, RD. Age-specific carcinogenesis: environmental exposure and susceptibility. Environ Health Perspect. 1995;103 Suppl 6(Suppl 6):45-8.

- Silva DBd, Pianovski MAD, Carvalho Filho NPd. Environmental pollution and cancer. Jornal de Pediatria. 2025;101:S18-S26.

- Davidson KW, Barry MJ, Mangione CM, Cabana M, Caughey AB, Davis EM, et al. Screening for Colorectal Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Jama. 2021;325(19):1965-77.

- Brown CM, Yow MV, Kumar S. Biological Age Acceleration and Colonic Polyps in Persons under Age 50. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2025;18(2):57-62.

- Parente F, Bargiggia S, Boemo C, Vailati C, Bonoldi E, Ardizzoia A, et al. Anatomic distribution of cancers and colorectal adenomas according to age and sex and relationship between proximal and distal neoplasms in an i-FOBT-positive average-risk Italian screening cohort. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2014;29(1):57-64.

- Schwarz S, Hornschuch M, Pox C, Haug U. Colorectal Cancer After Screening Colonoscopy: 10-Year Incidence by Site and Detection Rate at First Repeat Colonoscopy. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2023;14(1):e00535.

- Braitmaier M, Schwarz S, Kollhorst B, Senore C, Didelez V, Haug U. Screening colonoscopy similarly prevented distal and proximal colorectal cancer: a prospective study among 55-69-year-olds. J Clin Epidemiol. 2022;149:118-26.

- La Vecchia C, D’Avanzo B, Negri E, Franceschi S. History of selected diseases and the risk of colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer. 1991;27(5):582-6.

- Imperiale TF, Monahan PO, Stump TE, Glowinski EA, Ransohoff DF. Derivation and Validation of a Scoring System to Stratify Risk for Advanced Colorectal Neoplasia in Asymptomatic Adults: A Cross-sectional Study. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(5):339-46.

- Kim ER, Chang DK. Colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease: the risk, pathogenesis, prevention and diagnosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(29):9872-81.

- Bailey CE, Hu CY, You YN, Bednarski BK, Rodriguez-Bigas MA, Skibber JM, et al. Increasing disparities in the age-related incidences of colon and rectal cancers in the United States, 1975-2010. JAMA Surg. 2015;150(1):17-22.

- Dave D, Lu R, Klair JS, Kassim T, Ashfaq M, Chandra S, et al. Prevalence and Predictors of Adenomas in Young Adults Undergoing Diagnostic Colonoscopy in a Multicenter Midwest U.S. Cohort. Official journal of the American College of Gastroenterology | ACG. 2019;114.

- Winawer SJ, Zauber AG, Fletcher RH, Stillman JS, O’Brien MJ, Levin B, et al. Guidelines for colonoscopy surveillance after polypectomy: a consensus update by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer and the American Cancer Society. Gastroenterology. 2006;130(6):1872-85.

- Hassan C, Antonelli G, Dumonceau JM, Regula J, Bretthauer M, Chaussade S, et al. Post-polypectomy colonoscopy surveillance: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline - Update 2020. Endoscopy. 2020;52(8):687-700.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).