1. Introduction

Colon cancer (CC) is the third most common cancer in the United States, but it can be effectively treated if detected early through regular screening [

1]. However, an estimated 106,590 new cases of CC are expected in the United States in 2024, highlighting the ongoing need for screening and prevention efforts [

2]. Despite the increasing representation of racial and ethnic minorities in medical research, a disparity remains in the availability of studies specifically addressing CC prevalence in Asian American populations.

Asian Americans (AA), comprising about 6.0% of the U.S. population (nearly 20 million individuals), represent a diverse group with at least 21 subgroups [

3]. While the overall colorectal cancer incidence in AA (28.6 per 100,000 people from 2015 to 2019) is lower than that of other racial groups, disparities remain. For example, Japanese Americans have higher colorectal cancer incidence rates than Whites (25% higher in men and 11% higher in women) [

4,

5,

6]. Although CC is frequently grouped with rectal cancer under the term colorectal cancer, they differ notably in risk factors, anatomic locations, and surgical treatments [

7]. Focusing specifically on CC allows us to address unique disparities in screening and prevention, particularly in the AA population where differences in CC prevalence may be overlooked when combined with rectal cancer.

Risk factors that may increase CC risk among Asian immigrants and subsequent generations include acculturation, Western diets, and sedentary lifestyles [

8]. Immigration status has been associated with colorectal cancer, as Asian immigrants in the U.S. have colorectal cancer rates higher than those of their country of origin, likely due to changes in diet (including increased red meat consumption), sedentary lifestyle, and obesity [

8]. Genetics also play a role in susceptibility, with South Asians potentially having a lower incidence due to protective genetic factors [

5]. Phenotypic differences in CC formation have been noted, with AA being more likely than Whites to develop left-sided adenomas and less likely to have sessile serrated polyps [

9]. However, most studies do not disaggregate CC from rectal cancer, limiting our understanding of CC-specific risks within AA subgroups.

Barriers to healthcare access further exacerbate disparities in CC screening rates among AA. The American Cancer Society reports that only 50% of AA aged 45 and older undergo colorectal cancer screening, compared to 61% of Whites and Blacks, and 52% of Hispanics [

6]. AA people who have lived in the United States for more than 15-20 years and have higher levels of acculturation tend to have increased colorectal cancer screening rates [

9] while language barriers, unfamiliarity with the U.S. healthcare system, and lower health literacy hinder screening efforts among recent immigrants [

10,

11].

Geographical disparities in colorectal cancer incidence exist within the AA population. From 2006 to 2016, colorectal cancer incidence in AA declined in the West but remained unchanged in the Midwest and South [

12]. This variation may be attributed to lower socioeconomic status, lack of insurance, and risk factors such as diet and physical inactivity. While these studies focus broadly on colorectal cancer, the distinct regional and socioeconomic challenges likely apply to CC as well.

Our study utilizes data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS), which provides comprehensive information on health utilization, costs, insurance, and quality of healthcare. By analyzing annual trends of CC prevalence among AA across different age groups and geographic regions and integrated state and county-level socioeconomic data, our study aims to provide insights into factors influencing CC prevalence in this demographic. We excluded rectal cancer from our analysis to provide a more focused examination of CC. The findings will help provide insights for policy changes to improve access to CC screening and promote culturally competent care.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources

The primary data for this study was from 2017-2021 MEPS administered by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Data before this time period was not used due to the survey redesign in 2017 [

13]. MEPS is a national survey of noninstitutionalized individuals to study healthcare use, expenditures, and sources of payment while collecting information on demographics and socioeconomic status. MEPS uses stratification, clustering, and multiple stages of selection to form its nationally representative survey pool, and its method to calculate standard errors is available online [

14]. To obtain accurate estimates from MEPS data, each yearly consolidated file includes the individual’s weight, stratum, and primary sampling unit (PSU) variables.

To examine factors related to age-adjusted CC rates, data of county-level social determinants of health was drawn from the 2017-2021 County Health Rankings (CHR). CHR is an annual database that measures social, behavioral, and clinical factors for each county in all 50 of the United States and the District of Columbia [

15]. To merge the data from both MEPS and CHR, we submitted a request for confidential data files and used “county” as a linkage term to merge the two datasets. After the merger, all geographic information was removed again to protect individual privacy. Our study focused exclusively on CC among the AA population. Rectal cancer was not analyzed in this study, and since it is classified as a rare disease, it was excluded from the dataset by MEPS to safeguard patient privacy.

2.2. Study Sample

This study focused on adults aged 18 and older who self-reported their demographics and health conditions to MEPS. The unweighted sample size of adults was 23,733 in 2017, 23,027 in 2018, 21,965 in 2019, 21,879 in 2020, and 22,785 in 2021, and of them, there were 1,501, 1,217, 1,149, 1,176, and 1,163 AA adults from 2017 to 2021. Thirteen cancer questions were asked, and only those who responded “Yes” to colon cancer were considered our target population. The unweighted sample size of adults with CC was 133 in 2017, 114 in 2018, 129 in 2019, 147 in 2020, and 154 in 2021.

2.3. Measurements

Our outcomes included the crude CC rate and age-adjusted rate. Two Supplementary tables (

Appendix A) provide the denominators and numerators used to calculate the age-specific rates. We first divided the full sample by every 10 years of age to get the ratio of AAs in each age group in each year from 2017 to 2021 (Formula 1). The adjustment was accomplished by multiplying the age-specific rates of AAs with CC by age-specific weights among all AAs (Formula 2). Finally, we summed all age-specific rates across six age groups to yield the final age-adjusted rate for each of five years (Formula 3).

Age-Specific Rate = (Number of AA for each age group ÷ Number of AA) x 100% (1)

Crude CC Rate = (Number of AA with CC for each age group ÷ Number of AA with CC) x 100% (2)

Age-Adjusted CC Rate = Σ (Crude Rate x Age-Specific Rate) (3)

Our first independent variable, “Year,” was used to examine the trend of crude CC and adjusted rates among AAs over five years. Our second independent variable, “State,” was used to identify which state has the highest number of AAs with CC. Our third risk factor included two individual-level characteristics: whether the survey respondent spoke English or another language and whether the respondent had insurance at the time of the survey. Our last set of risk factors includes 12 county-level characteristics from the 2017-2021 CHR data: percentages of older adults, children or adolescents; physical and mental distress; food and housing insecurity; percentage of children in poverty; uninsured and unemployed rates; percentage of Native Americans; and daily PM 2.5 level (a measure of air pollution consisting of particles less than 2.5 micrometers in diameter). The source and definition of each measurement can be found on the CHR website [

15]. Finally, the study tested several other characteristics such as marital status, rural/urban classification, residential segregation index, and health conditions (e.g., high blood pressure), but found no significant differences (results not shown). Therefore, this study reported only the 14 factors that yielded significant results.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

We first examined yearly trends in the percentage of those with CC in five racial/ethnic groups: White, Black, Hispanic, Asian, and Other. Weighted frequency, row percentages, and column percentages were used to examine intra-racial and inter-racial changes over five years. Next, we adjusted the crude prevalence rate of CC by each year’s age distribution. The age-specific rate was obtained for every 10 years of age, and the age-adjusted rate was obtained by summing all 6 age groups’ rates. Third, we presented the age-adjusted rate and standard deviation of AAs with CC in each of the 50 states. We conducted one-way ANOVA using the state of Alaska as the reference group to determine if each state’s rate was significantly higher than that of Alaska. Finally, we compared CC rates by two personal-level characteristics and 12 county-level characteristics. Chi-squared tests were used for categorical variable risk factors (e.g., insured vs. uninsured) and t-tests were used for continuous variable risk factors (e.g., unemployment rate). All analyses were done by STATA v18 (StataCorp, Inc., College Station, TX), and any p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

Table 1 showed the numbers and percentages of adults with CC by race/ethnicity and year. There were 377,995 AA adults over five years and the column percentages showed that the CC rate within the AA group increased from 6.1% to 31.8% from 2017 to 2021. Next, the weight sample size remains plateau from 1,451,992 in 2017 to 1,388,760 in 2021. However, the row percentages showed that the percentage of AA accounting for the CC populations increased from 1.6% in 2017 to 8.6% in 2021. We also found increases in the percentages of Native Americans and multiracial groups with CC, but the differences across five racial groups were not statistically significant (p=0.1689).

Table 2 provides the percentage of AA in the population as well as the rate of AAs with CC within each age group per year. Because age is a significant risk factor for having any illness [

16,

17], we adjusted each prevalence by yearly age distribution and obtained an age-adjusted rate of CC per year, which increased from 155 per 100,000 in 2017 to 753 per 100,000 in 2021, approximately 4.86 times higher.

Table 3 compared the age-adjusted rate among the 50 states and the District of Columbia by using the state of Alaska (AL) as the reference group. We found that Arkansas (AR=0.00716), New Hampshire (NH=0.00691), and Rhode Island (RI=0.00691) had significantly higher rates of CC prevalence, while South Carolina (SC=0.00248), Vermont (VT=0.00256), and Wyoming (WY=0.00228) had significantly lower rates than Alaska (p<0.05). Among the 51 regions, AAs in Arkansas had the highest CC prevalence rate, at 716 per 100,000, while those in Wyoming had the lowest rate, at 228 per 100,000, representing approximately a 3.14-fold difference between the two states.

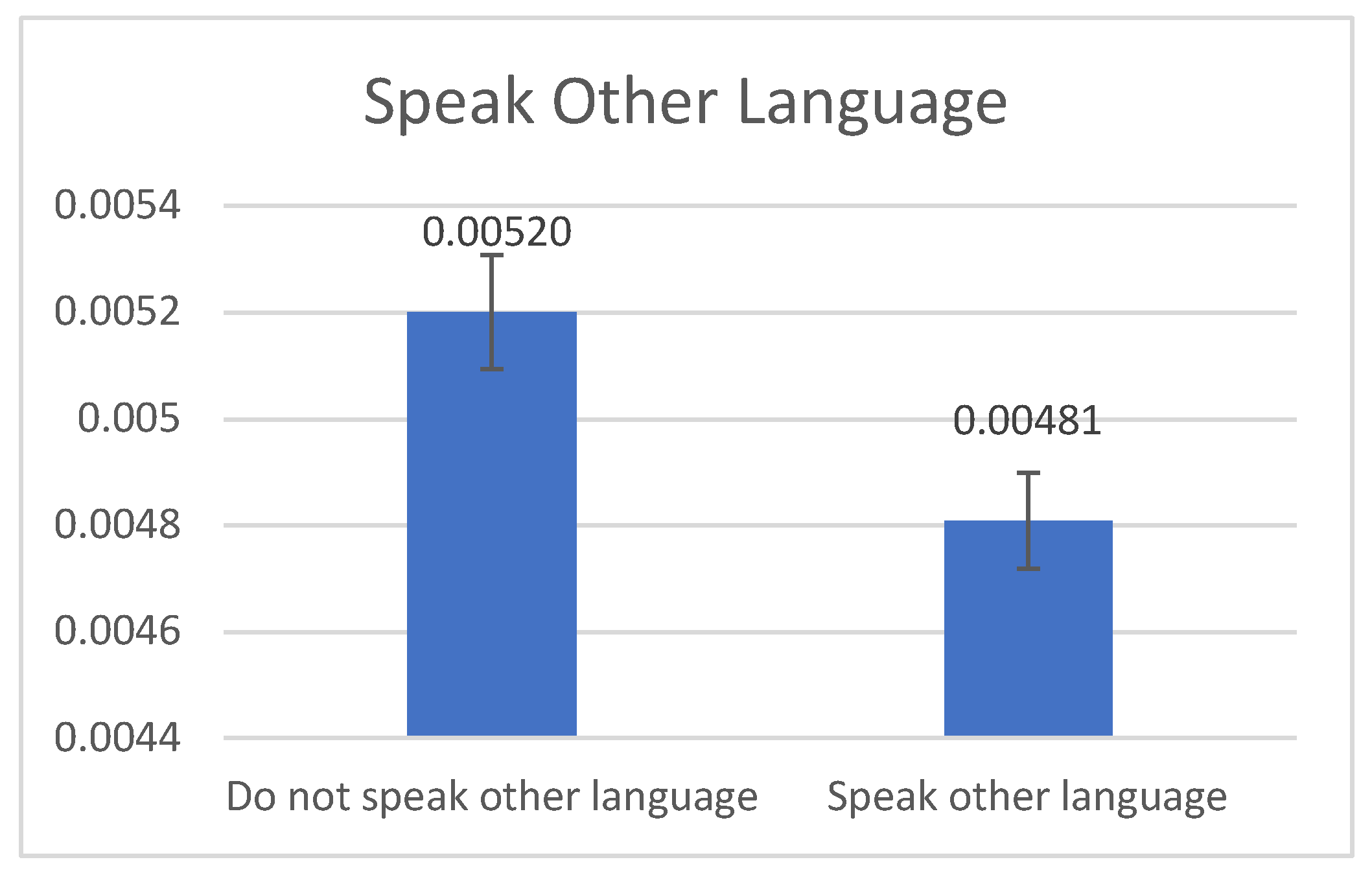

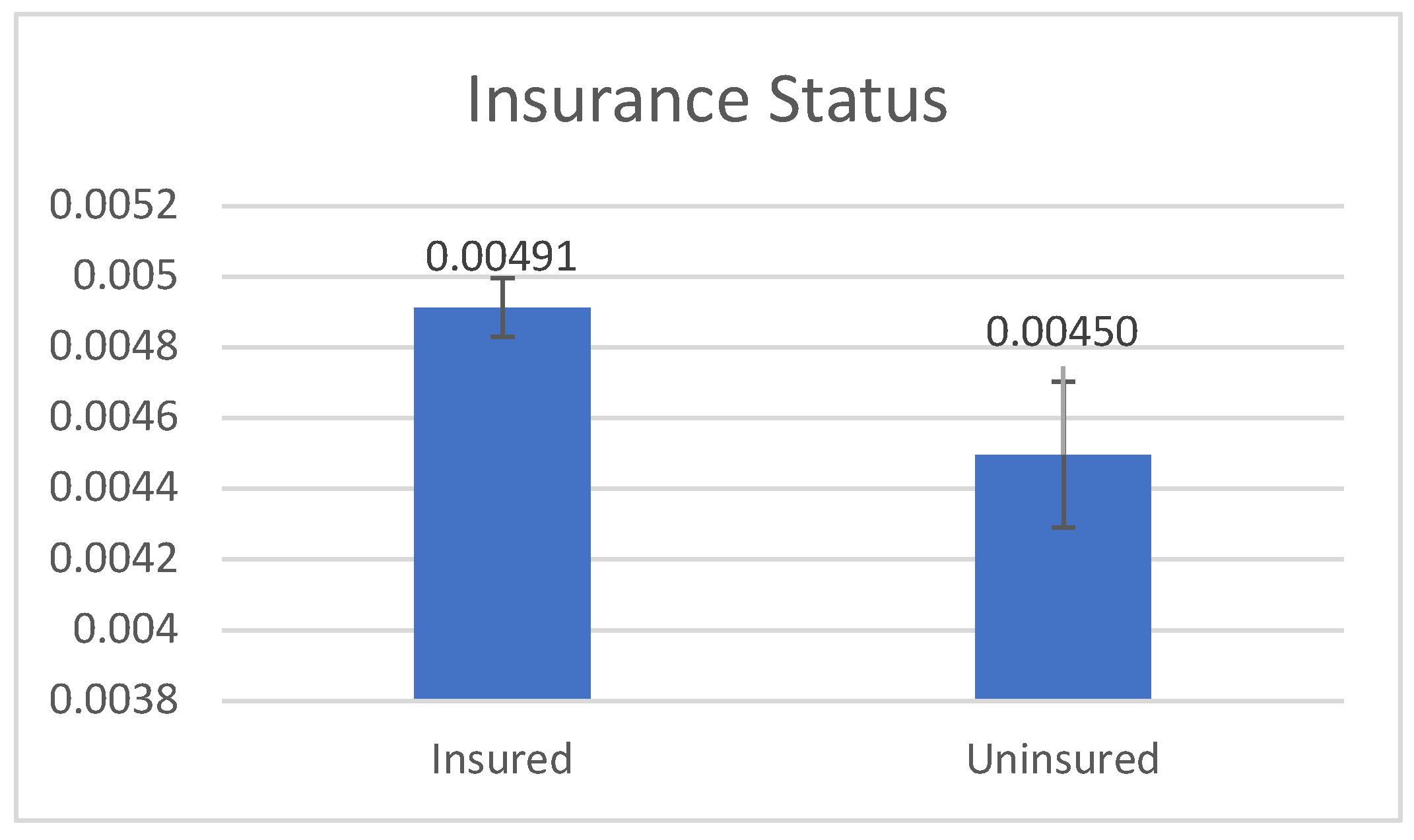

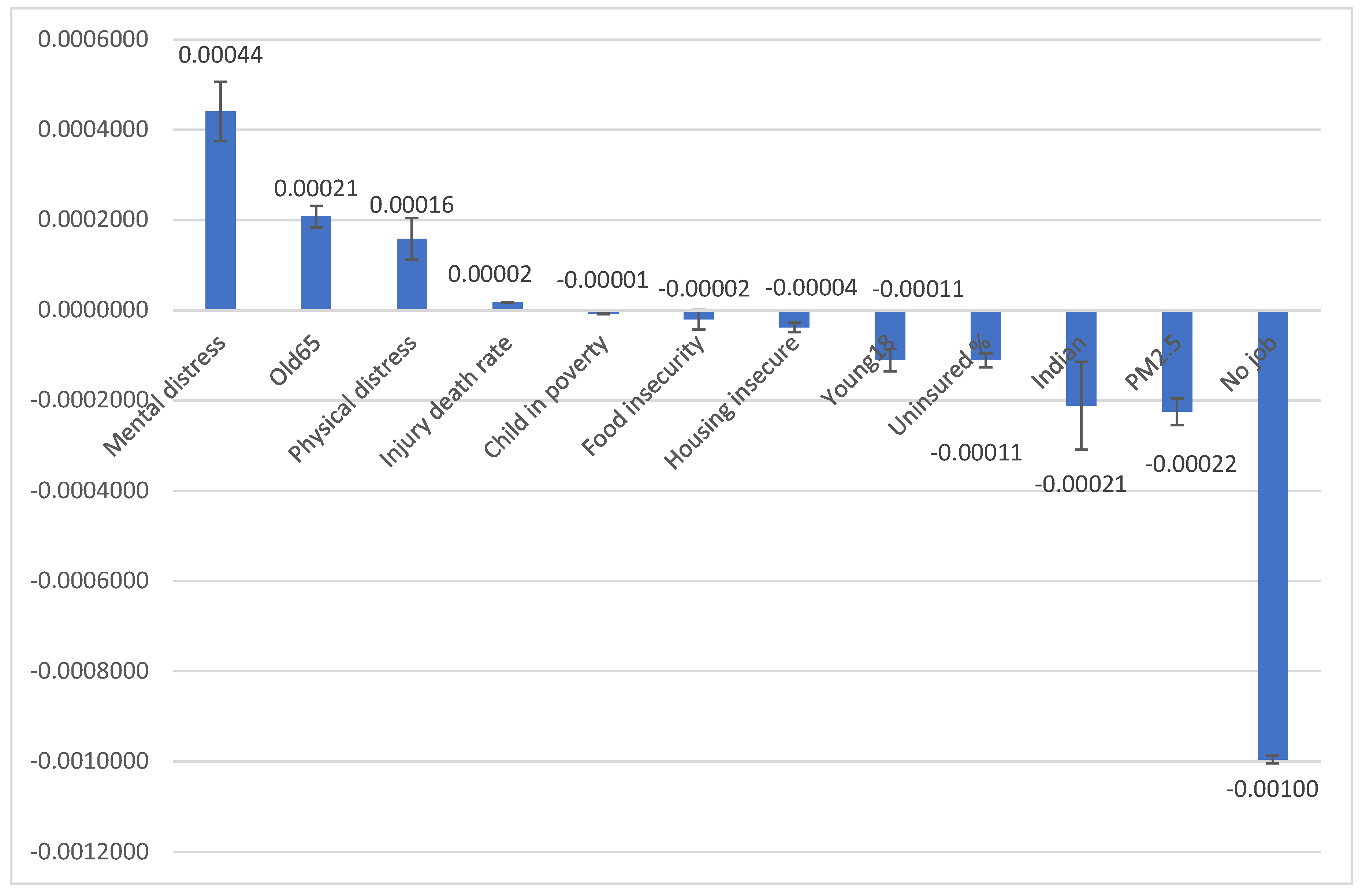

Three figures show the differences in the age-adjusted rates and standard deviations of 14 characteristics found to be statistically significant.

Figure 1 illustrates that age-adjusted rates were positively associated with AAs speaking English (mean: 520>480 per 100,000, p=0.001). No significant difference was found in CC rates between American-born and foreign-born AAs. However,

Figure 1 implies that people who speak other languages may be exposed to different diets and non-Western medicine practices that may act as a protective factor.

Figure 2 shows that the age-adjusted CC rate was positively associated with health insurance status (mean: 491>450 per 100,000, p=0.039), implying that AAs with health insurance are more likely to have access to CC screening and detection.

Figure 3 illustrates the 12 county-level characteristics with the age-adjusted CC rate and 95% Confidence Interval. The age-adjusted rate of CC was positively associated with four factors: a higher percentage of people with mental distress, a higher percentage of people aged 65 and older, a higher percentage of people with physical distress, and a higher injury-related death rate (p<0.05). Meanwhile, the age-adjusted rate of CC was negatively associated with eight factors: a higher percentage of children in poverty, a higher percentage of food insecurity, a higher percentage of housing insecurity, a higher percentage of people aged 18 and younger, a higher percentage of uninsured individuals, a higher percentage American Natives or Native Alaskans, higher average daily PM 2.5, and a higher percentage of unemployment (p<0.05). This finding suggests that CC prevalence is related to access to preventive care and CC screening. Areas with lower socioeconomic status may have less access to screening and therefore have a lower CC prevalence than more wealthy areas where screening is more accessible.

4. Discussion

4.1. Increasing Trend of Age-Adjusted Colon Cancer (CC) Rates

Our study provides a comprehensive analysis of CC prevalence among AAs, revealing a concerning trend of rising rates. The annual CC prevalence increased significantly, from 6.1% in 2017 to 31.8% in 2021, a rise potentially driven by either a rise in CC risk factors or more widespread adoption of CC screening practices. The proportion of CC prevalence among AA compared to the general population rose from 1.6% to 8.6% during this period, and the age-adjusted CC prevalence rate climbed from 155 per 100,00 to 753 per 100,000, as shown in

Table 2. A previous study on colorectal cancer from 2015 to 2019 in Asian American and Pacific Islanders found an incidence rate of 33.9 per 100,000 for men and 24.3 per 100,00 for women [

18]. Our age-adjusted rate accounts for the higher susceptibility of older individuals to cancer, making the stable increase concerning, especially considering that AA patients are more likely than white patients to present with advanced stages of CC and experience longer delays before surgery [

19]. Understanding these trends will be crucial for developing targeted interventions to address the rising CC rates in the AA population and improve outcomes.

Our study is the first to use MEPS and CHR data to analyze CC prevalence at the state and county levels among AAs, one of the fastest growing minority groups. Cultural factors may influence screening behaviors in AAs. One study found that Chinese and Korean immigrants were less likely to undergo colonoscopies due to time constraints or lack of symptoms, and preventive healthcare is not prioritized by many, who believe they can manage their health through diet and exercise [

20]. The perception of colon cancer as a predominantly “Western disease” further reduces the urgency of screening among AA immigrants [

20]. Collectivist values may lead some to avoid screening to prevent burdening their families with a potential diagnosis [

20]. More acculturated AA have higher screening rates, likely due to their familiarity with the healthcare system [

11]. Social factors such as being married and receiving positive feedback about screening from friends and family also contribute to greater openness to screening [

11]. Future studies should continuously monitor the screening rate among AAs.

4.2. State-Level Variations in CC Rates

State-level CC prevalence data highlights potential socioeconomic and geographical disparities in healthcare access. Arkansas (716 per 100,000), Rhode Island (691 per 100,000), and New Hampshire (691 per 100,000) had the highest CC prevalence rates among AA. Arkansas’ high rate is likely influenced by lifestyle and dietary factors typical of the South [

21]. However, the high prevalence in Rhode Island and New Hampshire, both located in New England, suggests that other factors may be at play. One theory proposes that reduced sunlight exposure in more northern regions contributes to vitamin D deficiency, which is linked to increased colorectal cancer risk [

22]. Additionally, these three states had AA median household incomes (MHI) well above the state averages [

23], a factor associated with better healthcare access and enhanced screening rates, and thus more detected cases of CC [

24].

In contrast, Wyoming (228 per 100,000), South Carolina (248 per 100,000), and Vermont (256 per 100,000) had the lowest CC prevalence rates among AA. The reasons for these lower rates are not entirely clear, although geographic and demographic factors may provide some explanation. These states, especially Wyoming, have barriers to healthcare access due to their predominantly rural nature. Wyoming’s sparsely populated regions face challenges in primary care availability and affordability [

25], thus contributing to decreased screening rates [

26]. Additionally, all three states have relatively small AA populations that are generally dispersed across small towns and cities, limiting the formation of ethnic enclaves and access to culturally sensitive healthcare services that promote screenings [

27]. More research is needed to understand the specific factors driving these regional disparities.

4.3. Personal Characteristics Associated with CC Rates

The higher CC prevalence found in our study among English-only speaking AA and those with health insurance may be largely attributed to increased access to screening, and thus, detection of cancer [

10,

28,

29,

30]. English proficiency is a significant protective factor for CC screening among AA, as those with high English proficiency often experience enhanced communication with healthcare providers, increased knowledge of CC, and greater compliance with screening guidelines [

10,

28,

31,

32,

33,

34]. In contrast, lower acculturation levels and limited English proficiency are linked to a decline in the perceived quality of healthcare services and decreased health literacy, resulting in lower CC screening rates [

35]. Efforts to improve colorectal cancer screening in AA by addressing the need for culturally sensitive care have met with mixed results. A pilot program for culturally sensitive education on colorectal cancer screening from community health workers did not significantly change screening intentions in Chinese, Korean, and Vietnamese adults [

36]. However, bilingual health educators increased colorectal cancer screening rates in Hmong Americans, suggesting that culturally sensitive care can be effective in populations with limited English proficiency [

37]. Therefore, English proficiency among AA is a key factor that facilitates better communication with healthcare providers and adherence to screening guidelines. For people without bilingual capacity, translation services would help promote higher screening rates and potentially greater detection of CC.

Health insurance is another significant protective factor in CC prevention by increasing access to preventive care and screenings. Early detection is critical, with the U.S. Preventative Services Task Force (2021) advising colorectal cancer screening for all adults aged 45 to 75 utilizing stool-based tests (e.g., guaiac fecal occult blood test, fecal immunochemical test, and stool DNA test) and direct visualization tests (e.g., colonoscopy, CT colonography, and flexible sigmoidoscopy) [

38,

39]. Lack of insurance is a known barrier to CC screening, as uninsured individuals are less likely to have regular preventive visits and routine screenings [

29,

30]. However, even people with insurance may not get full coverage for screening [

40]. For example, colorectal cancer screening rates remain lower among insured AA in California compared to insured whites (54.9% vs. 59.4%), despite expanded coverage under the Affordable Care Act [

41]. Overall, health insurance coverage significantly enhances CC screening rates among AA, although more targeted interventions are necessary to close the remaining gaps.

4.4. County-Level Characteristics Associated with CC Rates

Our study also measured 12 county characteristics that support the existing literature linking socioeconomic status to CC screening. Counties with higher levels of personal and health distress, older populations, and higher injury death rates also had higher CC prevalence. These factors suggest that counties facing greater stressors and older populations may be subject to more risk factors, leading to higher CC rates. While older age is a known risk factor for colon cancer, it is also associated with increased screening [

29]. Individuals in these counties may also be likely to have regular visits to primary care providers, a factor positively associated with increased CC screening in AA [

29,

42].

Counties with higher levels of poverty, food insecurity, housing insecurity, uninsured status, exposure to PM 2.5, and unemployment had lower CC prevalence, likely reflecting reduced access to preventive healthcare services, resulting in lower reported CC cases. The American Cancer Society reports that only 21% of uninsured adults aged 45 and older in the general population received colorectal cancer screening, with lower-income adults showing similar trends [

6]. Higher MHI contributes to improved healthcare, earlier detection, timely treatment, better quality of care, and better long-term survival rates [

24]. Additionally, MHI influences non-healthcare factors such as access to education, healthier lifestyles, and reduced environmental exposures [

24]. This association highlights the socioeconomic barriers that contribute to CC prevalence.

4.5. Limitations

Our study has some limitations. First, a study using 2009-2014 national data showed that Filipinos had a higher screening rate (55.0%) than Chinese (50.0%) or Asian Indians (48.6%) [

29]. However, our data does not disaggregate Asian subgroups, which include at least 21 subgroups with distinct cultural and dietary practices. Second, the vast cultural and socioeconomic differences between states were not fully explored in this analysis. Our study could provide an analysis of only county- and personal-level risk factors. Thirdly, the data from MEPS and CHR is self-reported and may be subject to recall bias. Lastly, CC is often grouped with rectal cancer under the umbrella of colorectal cancer. Since rectal cancer is considered a rare disease, it was removed by MEPS from the data to protect patient privacy. Thus, the findings of this study should be interpreted within the context of CC only. Many of the studies referenced in this paper focus on colorectal cancer without disaggregating colon and rectal cancer. This limitation underscores the need for targeted research on CC specifically within AA populations.

5. Conclusions

Our study demonstrated a rising incidence of colon cancer in AAs since 2017. As the third most commonly diagnosed cancer in the United States, it is critical to understand the contributing factors. Our study found that colon cancer is more likely to be diagnosed in AA populations who have increased access to care and familiarity with medical screenings. Future studies should determine whether early diagnosis of CC in AA communities leads to better outcomes and earlier intervention/access to treatment. To address the rising rate of CC diagnosis in the AA community, we also need to address the barriers to accessing routine preventive screening measures.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.-C.L. and C.H.D.; methodology, W.-C.L.; software, W.-C.L.; validation, W.-C.L.; formal analysis, W.-C.L.; investigation, W.-C.L.; resources, W.-C.L.; data curation, W.-C.L.; writing- original draft preparation, C.D., W.-C.L., C.H.D, C.X., K.C.; writing- review and editing, C.D., W.-C.L., C.H.D, C.X., K.C.; visualization, W.-C.L.; supervision, W.-C.L., K.C.; project administration, W.-C.L.; funding acquisition, K.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. C.D. and W.-C.L. served as co-first authors.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) [grant number 1 D34HP49234-01-00].

Institutional Review Board Statement

The use of 2017-2021 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey has been approved by the Institutional Review Board (#23-0190) at the University of Texas Medical Branch. County Health Rankings & Roadmaps is a public dataset available online.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Norma A Pérez Raifaisen, MD, DrPH, CPC-ELI-MP, Director of the UTMB Center of Excellence for Professional Advancement and Research (COEPAR), for assistance with manuscript preparation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Unweighted Sample Size by Year and Race/Ethnicity.

Table A1.

Unweighted Sample Size by Year and Race/Ethnicity.

| Year |

White |

Black |

Hispanic |

Asian |

Others |

Total |

| 2017 (all) |

11,461 |

3,987 |

6,052 |

1,501 |

732 |

23,733 |

| 2017 (cc) |

85 (0.74%) |

21 (0.53%) |

19 (0.31%) |

3 (0.20%) |

5 (0.68%) |

133 (0.56%) |

| 2018 (all) |

12,796 |

3,403 |

4,866 |

1,217 |

745 |

23,027 |

| 2018 (cc) |

78 (0.61%) |

12 (0.35%) |

12 (0.25%) |

4 (0.33%) |

8 (1.07%) |

144 (0.50%) |

| 2019 (all) |

12,534 |

3,130 |

4,462 |

1,149 |

690 |

21,965 |

| 2019 (cc) |

92 (0.73%) |

17 (0.54%) |

9 (0.20%) |

5 (0.44%) |

6 (0.87%) |

129 (0.59%) |

| 2020 (all) |

12,217 |

3,065 |

4,791 |

1,176 |

630 |

21,879 |

| 2020 (cc) |

187 (0.88%) |

17 (0.55%) |

11 (0.23%) |

6 (0.51%) |

6 (0.95%) |

147 (0.67%) |

| 2021 (all) |

12,808 |

3,273 |

4,856 |

1,163 |

388 |

22,785 |

| 2021 (cc) |

106 (0.83%) |

21 (0.64%) |

11 (0.23%) |

6 (0.52%) |

10 (1.45%) |

154 (0.68%) |

Table A2.

Weighted Sample Size of Asian Americans by Year and Age Category (Numbers Used to Calculate Age-Adjusted Rates in

Table 2).

Table A2.

Weighted Sample Size of Asian Americans by Year and Age Category (Numbers Used to Calculate Age-Adjusted Rates in

Table 2).

| |

Age (in years) |

| Year |

<30 |

31-40 |

41-50 |

51-60 |

61-70 |

71+ |

| 2017 (all) |

3,690,366 |

3,009,523 |

3,190,829 |

2,054,585 |

1,687,733 |

1,337,459 |

| 2017 (cc) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

23,209 |

| 2018 (all) |

3,647,937 |

3,239,001 |

3,281,121 |

1,942,190 |

1,853,426 |

1,447,776 |

| 2018 (cc) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

27,965 |

23,401 |

| 2019 (all) |

3,691,646 |

3,334,173 |

3,028,825 |

2,396,794 |

1,591,024 |

1,490,186 |

| 2019 (cc) |

0 |

0 |

17,425 |

0 |

28,315 |

32,073 |

| 2020 (all) |

3,587,151 |

3,086,144 |

3,036,222 |

2,526,148 |

1,695,181 |

1,561,851 |

| 2020 (cc) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

17,280 |

88,217 |

| 2021 (all) |

3,562,757 |

3,106,470 |

2,993,299 |

2,740,715 |

1,733,848 |

1,795,663 |

| 2021 (cc) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

23,660 |

96,449 |

References

- National Cancer Institute. Colon Cancer Treatment (PDQ) - Patient Version. National Cancer Institute. September 13, 2024. Accessed September 20, 2024. https://www.cancer.gov/types/colorectal/patient/colon-treatment-pdq.

- American Cancer Society. Cancer Statistics Center. American Cancer Society. Accessed September 20, 2024. https://cancerstatisticscenter.cancer.org/.

- Bureau UC. 20.6 Million People in the U.S. Identify as Asian, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander. Census.gov. Accessed September 20, 2024. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2022/05/aanhpi-population-diverse-geographically-dispersed.html.

- Jin, H.; Pinheiro, P.S.; Xu, J.; Amei, A. Cancer incidence among Asian American populations in the United States, 2009-2011. Int. J. Cancer 2016, 138, 2136–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, M.; Thapa, S. Colorectal cancer in the United States and a review of its heterogeneity among Asian American subgroups. Asia-Pacific J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 16, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Cancer Society. Colorectal Cancer Facts & Figures 2023. Am Cancer Soc. Published online 2023.

- van der Sijp, M.P.; Bastiaannet, E.; Mesker, W.E.; van der Geest, L.G.M.; Breugom, A.J.; Steup, W.H.; Marinelli, A.W.K.S.; Tseng, L.N.L.; Tollenaar, R.A.E.M.; van de Velde, C.J.H.; et al. Differences between colon and rectal cancer in complications, short-term survival and recurrences. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2016, 31, 1683–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, R.J.; Madan, R.A.; Kim, J.; Posadas, E.M.; Yu, E.Y. Disparities in Cancer Care and the Asian American Population. Oncol. 2021, 26, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardamean, C.I.; Sudigyo, D.; Budiarto, A.; Mahesworo, B.; Hidayat, A.A.; Baurley, J.W.; Pardamean, B. Changing Colorectal Cancer Trends in Asians: Epidemiology and Risk Factors. Oncol. Rev. 2023, 17, 10576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, C.A.; Gomez, S.L.; Chan, A.; Chan, J.K.; McClellan, S.R.; Chung, S.; Olson, C.; Nimbal, V.; Palaniappan, L.P. Patient and Provider Characteristics Associated with Colorectal, Breast, and Cervical Cancer Screening among Asian Americans. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers Prev. 2014, 23, 2208–2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, I.; Gawron, A.J.; Byrne, K.R.; Inadomi, J.M. Disparities in Colorectal Cancer Screening Among Asian American Populations and Strategies to Address These Disparities. Gastroenterology 2024, 166, 549–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang CP, Lin JJ, Shah SC, Kim MK, Colorectal Cancer Screening Working Group. Geographic Variation in Colorectal Cancer Incidence Among Asian Americans: A Population-Based Analysis 2006-2016. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol Off Clin Pract J Am Gastroenterol Assoc. 2023;21(2):543-545.e3. [CrossRef]

- Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. MEPS HC-201: 2017 Full Year Consolidated Data File. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. August 2019. Accessed October 17, 2024. https://meps.ahrq.gov/data_stats/download_data/pufs/h201/h201doc.shtml.

- Machlin S, Yu W, Zodet M. Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Computing Standard Errors for MEPS Estimates. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. January 2005. Accessed October 17, 2024. https://meps.ahrq.gov/survey_comp/standard_errors.jsp.

- University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute. Methods. County Health Rankings & Roadmaps. Accessed October 17, 2024. https://www.countyhealthrankings.org/health-data/methodology-and-sources/methods.

- Montégut, L.; López-Otín, C.; Kroemer, G. Aging and cancer. Mol. Cancer 2024, 23, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niccoli, T.; Partridge, L. Ageing as a Risk Factor for Disease. Curr. Biol. 2012, 22, R741–R752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.L.; Wagle, N.S.; Cercek, A.; Smith, R.A.; Jemal, A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2023. CA: A Cancer J. Clin. 2023, 73, 233–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, B.; Bajaj, S.S.; Patel, T.A.; Vapiwala, N.; Lam, M.B.; Mahal, B.A.; Muralidhar, V.; Amen, T.B.; Nguyen, P.L.; Sanford, N.N.; et al. Colon Cancer Disparities in Stage at Presentation and Time to Surgery for Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders: A Study with Disaggregated Ethnic Groups. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2023, 30, 5495–5505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, M.Y.; Holt, C.L.; Ng, D.; Sim, H.J.; Lu, X.; Le, D.; Juon, H.-S.; Li, J.; Lee, S. The Chinese and Korean American immigrant experience: a mixed-methods examination of facilitators and barriers of colorectal cancer screening. Ethn. Heal. 2018, 23, 847–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, R.L.; Medhanie, G.A.; Fedewa, S.A.; Jemal, A. State Variation in Early-Onset Colorectal Cancer in the United States, 1995–2015. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2019, 111, 1104–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abboud, Y.; Fraser, M.; Qureshi, I.; Srivastava, S.; Abboud, I.; Richter, B.; Jaber, F.; Alsakarneh, S.; Al-Khazraji, A.; Hajifathalian, K. Geographical Variations in Early Onset Colorectal Cancer in the United States between 2001 and 2020. Cancers 2024, 16, 1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggles S, Flood S, Sobek M, et al. IPUMS USA: Version 15:0 [dataset]. IPUMS USA. 2024. Accessed October 17, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Hu, F.-H.; Jia, Y.-J.; Zhao, D.-Y.; Zhang, W.-Q.; Tang, W.; Hu, S.-Q.; Ge, M.-W.; Du, W.; Shen, W.-Q.; et al. Socioeconomic status on survival outcomes in patients with colorectal cancer: a cross-sectional study. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 149, 15641–15655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, C.; Koller, C.F. Wyoming: A Rural/Interior State Perspective on Public Health Priorities. Am. J. Public Heal. 2019, 109, 705–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyabsi, M.; Meza, J.; Islam, K.M.M.; Soliman, A.; Watanabe-Galloway, S. Colorectal Cancer Screening Uptake: Differences Between Rural and Urban Privately-Insured Population. Front. Public Heal. 2020, 8, 532950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, A.; Pruitt, S.L.; Henry, K.A.; Lin, K.; Meltzer, D.; Canchola, A.J.; Rathod, A.B.; Hughes, A.E.; Kroenke, C.H.; Gomez, S.L.; et al. Asian American Enclaves and Healthcare Accessibility: An Ecologic Study Across Five States. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2023, 65, 1015–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sentell, T.L.; Tsoh, J.Y.; Davis, T.; Davis, J.; Braun, K.L. Low health literacy and cancer screening among Chinese Americans in California: a cross-sectional analysis. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e006104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sy, A.U.; Lim, E.; Ka’opua, L.S.; Kataoka-Yahiro, M.; Kinoshita, Y.; Stewart, S.L. Colorectal cancer screening prevalence and predictors among Asian American subgroups using Medical Expenditure Panel Survey National Data. Cancer 2018, 124, 1543–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Augustine, N.T.; Kwon, S.S. Preventive Cancer Screening in Asian Americans: Need for Community Outreach Programs. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2022, 23, 393–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Holt, C.L.; Chen, J.C.; Le, D.; Chen, J.; Kim, G.-Y.; Li, J.; Lee, S. Is Colorectal Cancer A Western Disease? Role of Knowledge and Influence of Misconception on Colorectal Cancer Screening among Chinese and Korean Americans: A Mixed Methods Study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev APJCP 2016, 17, 4885–4892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsoh, J.Y.; Tong, E.K.; Sy, A.U.; Stewart, S.L.; Gildengorin, G.L.; Nguyen, T.T. Knowledge of colorectal cancer screening guidelines and intention to obtain screening among nonadherent Filipino, Hmong, and Korean Americans. Cancer 2018, 124, 1560–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, K.M.; An, K.; Lee, M.; Shin, C.; Steves, S.L. Colorectal cancer screening disparities in Asian Americans: the influences of patient-provider communication and social media use. Cancer Causes Control. 2023, 34, 813–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morey, B.N.; Valencia, C.; Lee, S. The Influence of Asian Subgroup and Acculturation on Colorectal Cancer Screening Knowledge and Attitudes Among Chinese and Korean Americans. J. Cancer Educ. 2022, 37, 1806–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Y.; Tauscher, J.; Cardel, M. Distrust in Health Care and Cultural Factors Are Associated With Uptake of Colorectal Cancer Screening in Hispanic and Asian Americans. Cancer 2018, 124, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carney, P.A.; Lee-Lin, F.; Mongoue-Tchokote, S.; Mori, M.; Leung, H.; Lau, C.; Le, T.D.; Lieberman, D.A. Improving colorectal cancer screening in Asian Americans: Results of a randomized intervention study. Cancer 2014, 120, 1702–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, E.K.; Nguyen, T.T.; Lo, P.; Stewart, S.L.; Gildengorin, G.L.; Tsoh, J.Y.; Jo, A.M.; Kagawa-Singer, M.L.; Sy, A.U.; Cuaresma, C.; et al. Lay health educators increase colorectal cancer screening among Hmong Americans: A cluster randomized controlled trial. Cancer 2017, 123, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S. Screening for Colorectal Cancer. Hematol. Clin. North Am. 2022, 36, 393–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Colorectal Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2021;325(19):1965-1977. [CrossRef]

- Murray T. Here’s How to Get Your Colonoscopy Costs Covered. Health. October 17, 2023. Accessed October 17, 2024. https://www.health.com/money/colonoscopy-costs.

- McMenamin, S.B.; Pourat, N.; Lee, R.; Breen, N. The Importance of Health Insurance in Addressing Asian American Disparities in Utilization of Clinical Preventive Services: 12-Year Pooled Data from California. Heal. Equity 2020, 4, 292–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; E Lee, E. Access to Health Care, Beliefs, and Behaviors about Colorectal Cancer Screening among Korean Americans. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev APJCP 2018, 19, 2021–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).