Submitted:

22 July 2025

Posted:

23 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. CHD epidemiology

2.1. Prevalence of CHD

2.2. Mortality and morbidity in CHD

2.3. Causes and critical outcomes of CHD

3. Most common types of CHD

3.1. Ventricular septal defect

3.2. Atrial septal defect

3.3. Patent ductus arteriosus

3.4. Prevalence of the three most common types of CHD

4. Conventional, transcatheter, and hybrid approaches for correction of ventricular septal defects

4.1. General Considerations on Prognostic Implications and Risk Stratification

4.2. Surgical approaches to treat VSD

4.2.1. Conventional surgical repair of VSD utilizing cardiopulmonary bypass

4.2.2. Percutaneous (transcatheter) approach for VSD closure

4.2.3. Hybrid approach for VSD correction

5. Procedural and technical aspects of hybrid approach in treating ventricular septal defects

5.1. Surgical Steps of the Hybrid Ventricular Septal Defect Closure Technique

5.2. Device delivery approaches

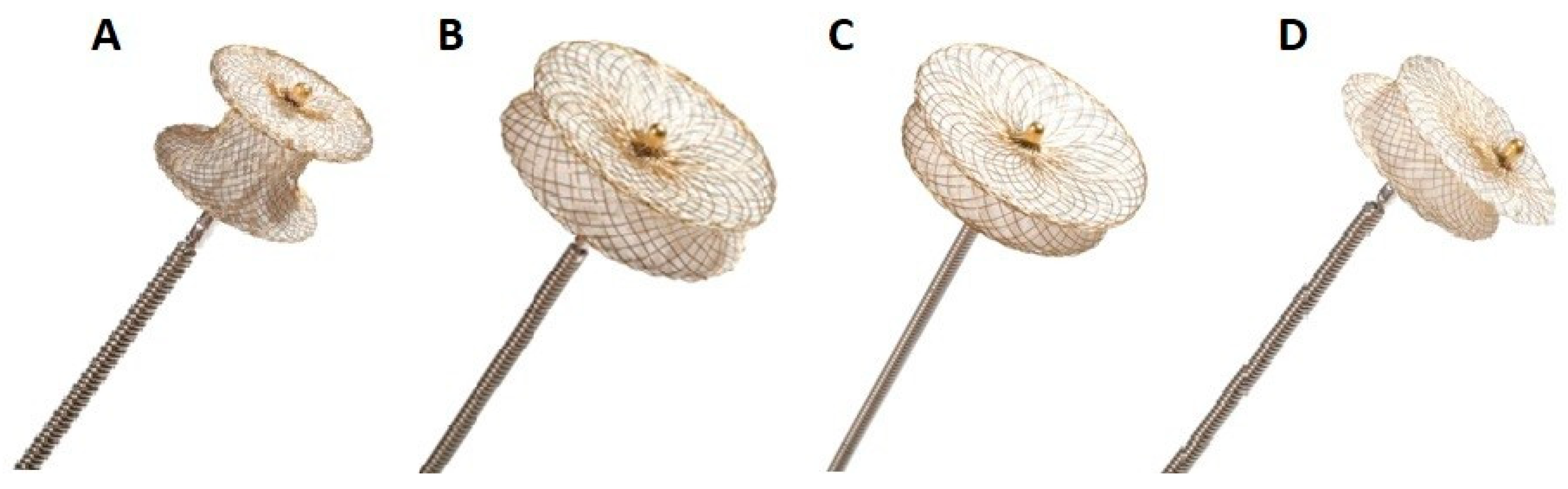

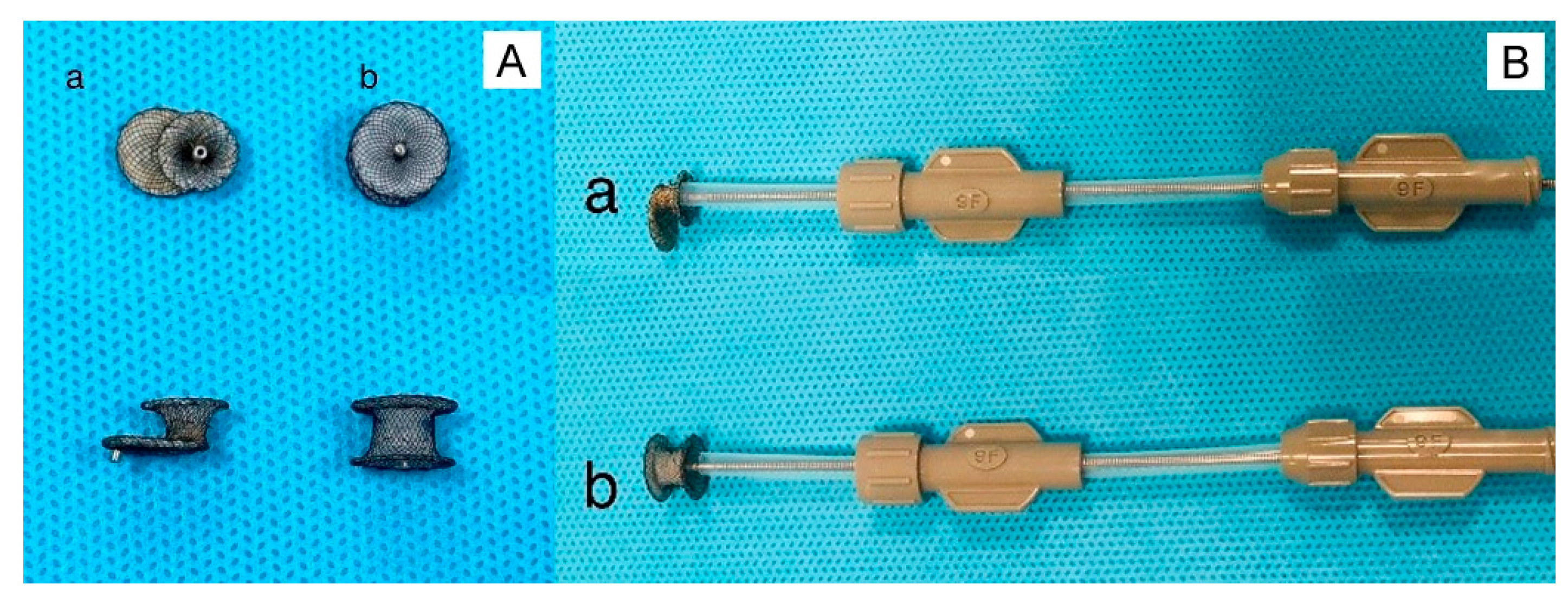

5.3. The types of device used to close VSD

6. Advantages and limitations of hybrid approach for VSD closure

7. Future prospects in using hybrid approach for VSD closure

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADO | Amplatzer Duct Occluder |

| ASD | Atrial Septal Defect |

| CABG | Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting |

| cAVB | complete Atrio-Ventricular Block |

| CHD | Congenital Heart Defect |

| CPB | CardioPulmonary Bypass |

| LV | Left Ventricle |

| LVEF | Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction |

| PDA | Patent Ductus Arteriosus |

| RV | Right Ventricle |

| TEE | Trans-Esophageal Echocardiographic (guidance) |

| VSD | Ventricular Septal Defect |

References

- Forman, J.; Beech, R.; Slugantz, L.; Donnellan, A. A Review of Tetralogy of Fallot and Postoperative Management. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am 2019, 31, 315–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singhi, A.K.; Mukherji, A.; De, A. Perimembranous ventricular septal defect closure in infants with KONAR-MF occluder. Prog Pediatr Cardiol 2022, 65, 101489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurkeyev, B.; Marassulov, S.; Aldabergenov, Y.; Adilbekova, A.; Murzabayeva, S.; Kuandykova, E.; Akhmoldaeva, A. A Clinical Case of Successful Surgical Correction of Tetralogy of Fallot by Using the Right Atrial Appendage as a Neopulmonary Valve. J Clin Med Kaz 2024, 21, 71–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalén, M.; Odermarsky, M.; Liuba, P.; Johansson Ramgren, J.; Synnergren, M.; Sunnegårdh, J. Long-Term Survival After Single-Ventricle Palliation: A Swedish Nationwide Cohort Study. J Am Heart Assoc 2024, 13, e031722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD2017 Congenital Heart Disease Collaborators Global regional national burden of congenital heart disease 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017 Lancet Child Adolesc Health, 2.0.2.0.; 4; 185-200,,,, h.t.t.p.s.:././.d.o.i.o.r.g./.1.0.1.0.1.6./.S.2.3.5.2.-4.6.4.2.(.1.9.).3.0.4.0.2.-X. Erratum in: Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2020, 4, e6. [CrossRef]

- Swanson, J.; Ailes, E.C.; Cragan, J.D.; Grosse, S.D.; Tanner, J.P.; Kirby, R.S.; Waitzman, N.J.; Reefhuis, J.; Salemi, J.L. Inpatient Hospitalization Costs Associated with Birth Defects Among Persons Aged <65 Years - United States, 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2023, 72, 739–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilboa, S.M.; Devine, O.J.; Kucik, J.E.; Oster, M.E.; Riehle-Colarusso, T.; Nembhard, W.N.; Xu, P.; Correa, A.; Jenkins, K.; Marelli, A.J. Congenital Heart Defects in the United States: Estimating the Magnitude of the Affected Population in 2010. Circulation 2016, 134, 101–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo-Valenzuela, N.J.; Peixoto, A.B.; Araujo Júnior, E. Prenatal diagnosis of congenital heart disease: A review of current knowledge. Indian Heart J 2018, 70, 150–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poulsen, C.B.; Damkjær, M. Trends in prescription of cardiovascular drugs to children in relation to prevalence of CHD from 1999 to 2016. Cardiol Young 2018, 28, 1136–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxena, A. Status of Pediatric Cardiac Care in Developing Countries. Children (Basel) 2019, 6, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vervoort, D.; Jin, H.; Edwin, F.; Kumar, R.K.; Malik, M.; Tapaua, N.; Verstappen, A.; Hasan, B.S. Global Access to Comprehensive Care for Paediatric and Congenital Heart Disease. CJC Pediatr Congenit Heart Dis 2023, 2(6Part B), 453–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giang, H.T.N.; Bechtold-Dalla Pozza, S.; Ulrich, S.; Linh, L.K.; Tran, H.T. Prevalence and Pattern of Congenital Anomalies in a Tertiary Hospital in Central Vietnam. J Trop Pediatr 2020, 66, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossano, J.W. Congenital heart disease: a global public health concern. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2020, 4, 168–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tankeu, A.T.; Bigna, J.J.; Nansseu, J.R.; Aminde, L.N.; Danwang, C.; Temgoua, M.N.; Noubiap, J.J. Prevalence and patterns of congenital heart diseases in Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis protocol. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e015633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Linde, D.; Konings, E.E.; Slager, M.A.; Witsenburg, M.; Helbing, W.A.; Takkenberg, J.J.; Roos-Hesselink, J.W. Birth prevalence of congenital heart disease worldwide: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011, 58, 2241–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.Y.; Chao, A.S.; Kao, C.C.; Lin, C.H.; Hsieh, C.C. The Outcome of Prenatally Diagnosed Isolated Fetal Ventricular Septal Defect. J Med Ultrasound 2017, 25, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, S.; Zühlke, L.; Black, G.C.; Choy, M.K.; Li, N.; Keavney, B.D. Global birth prevalence of congenital heart defects 1970-2017: updated systematic review and meta-analysis of 260 studies. Int J Epidemiol 2019, 48, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Chen, L.; Yang, T.; Wang, T.; Zhang, S.; Chen, L.; Ye, Z.; Luo, L.; Qin, J. Birth prevalence of congenital heart disease in China, 1980-2019: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 617 studies. Eur J Epidemiol 2020, 35, 631–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Z.; Wei, J.; Huang, X.; Chen, B.; Liang, L.; Feng, B.; Song, P.; He, J.; Que, T.; Lan, J.; Qin, J.; He, S.; Wei, Q. Epidemiology of Congenital Heart Defects in Perinatal Infants in Guangxi, China. Int J Gen Med 2024, 17, 5381–5396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, D.; Wang, H.; Liu, Z.; Fang, J.; Yang, T.; Zhou, S.; Wang, A.; Qin, J.; Xiong, L. Perinatal outcomes and congenital heart defect prognosis in 53313 non-selected perinatal infants. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0177229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Liu, B.; Li, H.; Wang, C.; Yang, S.; Li, Z. Epidemiology of Congenital Heart Disease in Jinan, China From 2005 to 2020: A Time Trend Analysis. Front Cardiovasc Med 2022, 9, 815137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, F.; Li, J.; Lou, H.; Li, J.; Jin, Y.; Wu, T.; Pan, L.; An, J.; Xu, J.; Cheng, W.; Tao, L.; Lei, Y.; Huang, C.; Yin, F.; Chen, J.; Zhu, J.; Shu, Q.; Xu, W. Geographical and Socioeconomic Factors Influence the Birth Prevalence of Congenital Heart Disease: A Population-based Cross-sectional Study in Eastern China. Curr Probl Cardiol 2022, 47, 101341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, L.; Kang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Yan, H. Prevalence and risk factors of congenital heart defects among live births: a population-based cross-sectional survey in Shaanxi province, Northwestern China. BMC Pediatr 2017, 17, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.F.; Ding, G.C.; Zhang, M.Y.; He, S.N.; Gao, Y.; Wang, J.H. Prevalence of Congenital Heart Disease among Infants from 2012 to 2014 in Langfang, China. Chin Med J (Engl) 2017, 130, 1069–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Q.M.; Liu, F.; Wu, L.; Ma, X.J.; Niu, C.; Huang, G.Y. Prevalence of Congenital Heart Disease at Live Birth in China. J Pediatr 2019, 204, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Zhao, S.; Dong, X.; Liu, J.; Guo, Y.; Ju, W.; Chen, P.; Gao, Y.; Feng, Q.; Zhu, X.; Huang, H.; Lu, X.; Yang, X.; Yang, F.; Cheng, C.; Luo, X.; Cheng, L. Zhong, N; Chinese Consortium for Prenatal Ultrasound Screening of Congenital Heart Defects. Incidence, distribution, disease spectrum, and genetic deficits of congenital heart defects in China: implementation of prenatal ultrasound screening identified 18,171 affected fetuses from 2,452,249 pregnancies. Cell Biosci 2023, 13, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Kumar, P. Echocardiographic Study of Ventricular Septal Defect in 1- to 12-Year-Old Children Visiting a Tertiary Care Center in Patna, India. Cureus 2023, 15, e46363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, A.; Mehta, A.; Sharma, M.; Salhan, S.; Kalaivani, M.; Ramakrishnan, S.; Juneja, R. Birth prevalence of congenital heart disease: A cross-sectional observational study from North India. Ann Pediatr Cardiol 2016, 9, 205–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, R.; Rai, S.K.; Yadav, A.K.; Lakhotia, S.; Agrawal, D.; Kumar, A.; Mohapatra, B. Epidemiology of Congenital Heart Disease in India. Congenit Heart Dis 2015, 10, 437–46, Erratum in: Congenit Heart Dis 2019, 14, 1214. 10.1111/chd.12775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudheer, K.R.; Mohammad Koya, P.K.; Prakash, A.J.; Prakash, A.M.; Manoj Kumar, R.; Shyni, S.; Jagadeesan, C.K.; Jaikrishan, G.; Das, B. Evaluation of risk due to chronic low dose ionizing radiation exposure on the birth prevalence of congenital heart diseases (CHD) among the newborns from high-level natural radiation areas of Kerala coast, India. Genes Environ 2022, 44, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giang, H.T.N.; Hai, T.T.; Nguyen, H.; Vuong, T.K.; Morton, L.W.; Culbertson, C.B. Elevated congenital heart disease birth prevalence rates found in Central Vietnam and dioxin TCDD residuals from the use of 2, 4, 5-T herbicides (Agent Orange) in the Da Nang region. PLOS Glob Public Health 2022, 2, e0001050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed-Saidan, M.A.; Atiyah, M.; Ammari, A.N.; AlHashem, A.M.; Rakaf, M.S.; Shoukri, M.M.; Garne, E.; Kurdi, A.M. Patterns, prevalence, risk factors, and survival of newborns with congenital heart defects in a Saudi population: a three-year, cohort case-control study. J Congenit Heart Dis 2019, 3, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, M.; Sable, C. Congenital heart disease in low-and-middle-income countries: Focus on sub-Saharan Africa. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet 2020, 184, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danso, K.A.; Appah, G.; Akuaku, R.S.; Karikari, Y.S.; Ansong, A.K.; Edwin, F.; Yao, N.A. Prevalence of Congenital Heart Disease in Children and Adolescents Under 18 in Africa: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. World J Pediatr Congenit Heart Surg 2025, 16, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zikarg, Y.T.; Yirdaw, C.T.; Aragie, T.G. Prevalence of congenital septal defects among congenital heart defect patients in East Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0250006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossouw, B. Congenital heart disease in Africa threatens Sustainable Development Goals. South Afr J Crit Care 2021, 37, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleimani, H.; Bahiraie, P.; Tavakoli, K.; Hosseini Mohammadi, N.S.; Hajari, P.; Taheri, H.; Hosseini, K.; Ebrahimi, P. Burden of Congenital Heart Anomalies in North Africa and the Middle East, 1990 to 2021: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. J Am Heart Assoc 2025, 14, e037291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, P.S.; Magalhães, L.R.; Pezzini, T.R.; de Sousa Santos, E.F.; Calderon, M.G. Congenital heart diseases trends in São Paulo State, Brazil: a national live birth data bank analysis. World J Pediatr 2022, 18, 472–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portilla, R.E.; Harizanov, V.; Sarmiento, K.; Holguín, J.; Gracia, G.; Hurtado-Villa, P.; Zarante, I. Risk factors characterisation for CHD: a case-control study in Bogota and Cali, Colombia, 2002-2020. Cardiol Young 2024, 34, 178–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Andrade, F. High Altitude as a Cause of Congenital Heart Defects: A Medical Hypothesis Rediscovered in Ecuador. High Alt Med Biol 2020, 21, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucron, H.; Brard, M.; d'Orazio, J.; Long, L.; Lambert, V.; Zedong-Assountsa, S.; Le Harivel de Gonneville, A.; Ahounkeng, P.; Tuttle, S.; Stamatelatou, M.; Grierson, R.; Inamo, J.; Cuttone, F.; Elenga, N.; Bonnet, D.; Banydeen, R. Infant congenital heart disease prevalence and mortality in French Guiana: a population-based study. Lancet Reg Health Am 2023, 29, 100649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egbe, A.; Uppu, S.; Lee, S.; Stroustrup, A.; Ho, D.; Srivastava, S. Temporal variation of birth prevalence of congenital heart disease in the United States. Congenit Heart Dis 2015, 10, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkes, J.K.; Whitehead, W.E.; Wang, Y.; Morris, S.A. Congenital Heart Disease and Myelomeningocele in the Newborn: Prevalence and Mortality. Pediatr Cardiol 2021, 42, 1026–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stallings, E.B.; Isenburg, J.L.; Aggarwal, D.; Lupo, P.J.; Oster, M.E.; Shephard, H.; Liberman, R.F.; Kirby, R.S.; Nestoridi, E.; Hansen, B.; Shan, X.; Navarro Sanchez, M.L.; Boyce, A.; Heinke, D. ; National Birth Defects Prevention Network Prevalence of critical congenital heart defects selected co-occurring congenital anomalies 2014-2018:,,,, A. U.S. population-based study. Birth Defects Res 2022, 114, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, D.M.; Stabler, M.E.; MacKenzie, T.A.; Zimmerman, M.S.; Shi, X.; Everett, A.D.; Bucholz, E.M.; Brown, J.R. Population-Based Estimates of the Prevalence of Children With Congenital Heart Disease and Associated Comorbidities in the United States. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2024, 17, e010657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mamasoula, C.; Addor, M.C.; Carbonell, C.C.; Dias, C.M.; Echevarría-González-de-Garibay, L.J.; Gatt, M.; Khoshnood, B.; Klungsoyr, K.; Randall, K.; Stoianova, S.; Haeusler, M.; Nelen, V.; Neville, A.J.; Perthus, I.; Pierini, A.; Bertaut-Nativel, B.; Rissmann, A.; Rouget, F.; Schaub, B.; Tucker, D.; Wellesley, D.; Zymak-Zakutnia, N.; Barisic, I.; de Walle, H.E.K.; Lanzoni, M.; Mullaney, C.; Pennington, L.; Rankin, J. Prevalence of congenital heart defects in Europe, 2008-2015: A registry-based study. Birth Defects Res 2022, 114, 1404–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, M.K.; Bergman, J.E.H.; Krikov, S.; Amar, E.; Cocchi, G.; Cragan, J.; de Walle, H.E.K.; Gatt, M.; Groisman, B.; Liu, S.; Nembhard, W.N.; Pierini, A.; Rissmann, A.; Chidambarathanu, S. Sipek A,,,, J.r.; Szabova, E.; Tagliabue, G.; Tucker, D.; Mastroiacovo, P.; Botto, L.D. Prenatal diagnosis and prevalence of critical congenital heart defects: an international retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e028139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourdon, G.; Lenne, X.; Godart, F.; Storme, L.; Theis, D.; Subtil, D.; Bruandet, A.; Rakza, T. Epidemiology of congenital heart defects in France from 2013 to 2022 using the PMSI-MCO (French Medical Information System Program in Medicine, Surgery, and Obstetrics) database. PLoS One 2024, 19, e0298234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giang, K.W.; Mandalenakis, Z.; Fedchenko, M.; Eriksson, P.; Rosengren, A.; Norman, M.; Hanséus, K.; Dellborg, M. Congenital heart disease: changes in recorded birth prevalence and cardiac interventions over the past half-century in Sweden. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2023, 30, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, S.; Zühlke, L.; Babu-Narayan, S.V.; Black, G.C.; Choy, M.K.; Li, N.; Keavney, B.D. Global prevalence of congenital heart disease in school-age children: a meta-analysis and systematic review. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2020, 20, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Zhao, F.; Liu, X.; Liu, F.; Xue, Y.; Liao, H.; Zhan, X.; Lin, W.; Zheng, M.; Jiang, J.; Li, H.; Ma, X.; Wu, S.; Deng, H. Prevalence of congenital heart disease among school children in Qinghai Province. BMC Pediatr 2022, 22, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salari, N.; Faryadras, F.; Shohaimi, S.; Jalili, F.; Hasheminezhad, R.; Babajani, F.; Mohammadi, M. Global prevalence of congenital heart diseases in infants: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neonatal Nurs 2024, 30, 570–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurvitz, M.; Dunn, J.E.; Bhatt, A.; Book, W.M.; Glidewell, J.; Hogue, C.; Lin, A.E.; Lui, G.; McGarry, C.; Raskind-Hood, C.; Van Zutphen, A.; Zaidi, A.; Jenkins, K.; Riehle-Colarusso, T. Characteristics of Adults With Congenital Heart Defects in the United States. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020, 76, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomek, V. Jicínská,,,, H.; Pavlícek, J.; Kovanda, J.; Jehlicka, P.; Klásková,,,, E.; Mrázek, J.; Cutka, D.; Smetanová,,,, D.; Brešták, M.; Vlašín, P.; Pavlíková,,,, M.; Chaloupecký, V.; Janoušek, J.; Marek, J. Pregnancy Termination and Postnatal Major Congenital Heart Defect Prevalence After Introduction of Prenatal Cardiac Screening. JAMA Netw Open 2023, 6, e2334069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, Y.; Lakshminrusimha, S. Perinatal Cardiovascular Physiology and Recognition of Critical Congenital Heart Defects. Clin Perinatol 2021, 48, 573–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rakha, S. Initiating a Fetal Cardiac Program from Scratch in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Structure, Challenges, and Hopes for Solutions. Pediatr Cardiol 2025, 46, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinstein, J.A.; Benson, D.W.; Dubin, A.M.; Cohen, M.S.; Maxey, D.M.; Mahle, W.T.; Pahl, E.; Villafañe, J.; Bhatt, A.B.; Peng, L.F.; Johnson, B.A.; Marsden, A.L.; Daniels, C.J.; Rudd, N.A.; Caldarone, C.A.; Mussatto, K.A.; Morales, D.L.; Ivy, D.D.; Gaynor, J.W.; Tweddell, J.S.; Deal, B.J.; Furck, A.K.; Rosenthal, G.L.; Ohye, R.G.; Ghanayem, N.S.; Cheatham, J.P.; Tworetzky, W.; Martin, G.R. Hypoplastic left heart syndrome: current considerations and expectations. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012, 59(1 Suppl), S1–42, Erratum in: J Am Coll Cardiol 2012, 59(5), 544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raza, S.; Aggarwal, S.; Jenkins, P.; Kharabish, A.; Anwer, S.; Cullington, D.; Jones, J.; Dua, J.; Papaioannou, V.; Ashrafi, R.; Moharem-Elgamal, S. Coarctation of the Aorta: Diagnosis and Management. Diagnostics (Basel) 2023, 13, 2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, M.; Marino, B.; Kaltman, J.; Laursen, H.; Jakobsen, L.; Mahle, W.; Pearson, G.; Madsen, N. Myocardial Infarction in Adults With Congenital Heart Disease. Am J Cardiol 2017, 120, 2272–2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergh, N.; Skoglund, K.; Fedchenko, M.; Bollano, E.; Eriksson, P.; Dellborg, M.; Wai Giang, K.; Mandalenakis, Z. Risk of Heart Failure in Congenital Heart Disease: A Nationwide Register-Based Cohort Study. Circulation 2023, 147, 982–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Chen, L.; Yang, T.; Huang, P.; Wang, L.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, S.; Ye, Z.; Chen, L.; Zheng, Z.; Qin, J. Congenital Heart Disease and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease: A Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies. J Am Heart Assoc 2019, 8, e012030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lytzen, R.; Vejlstrup, N.; Bjerre, J.; Petersen, O.B.; Leenskjold, S.; Dodd, J.K.; Jørgensen, F.S.; Søndergaard, L. Live-Born Major Congenital Heart Disease in Denmark: Incidence, Detection Rate, and Termination of Pregnancy Rate From 1996 to 2013. JAMA Cardiol 2018, 3, 829–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, K.; Park, C.; Lee, J.; Shin, J.; Choi, E.; Choi, M.; Kim, J.; Shin, H.; Choi, B.; Kim, S.J. A Comparison for Infantile Mortality of Crucial Congenital Heart Defects in Korea over a Five-Year Period. J Clin Med 2024, 13, 6480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syssoyev, D.; Seitkamzin, A.; Lim, N.; Mussina, K.; Poddighe, D.; Gaipov, A.; Galiyeva, D. Epidemiology of Congenital Heart Disease in Kazakhstan: Data from the Unified National Electronic Healthcare System 2014-2021. J Clin Med Kaz 2024, 21, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adilbekova, A.; Nurkeev, B.; Marassulov, S.; Kozhakhmetov, S. Mid-Term Outcome of the Hybrid Method of Ventricular Septal Defect Closure in Children. J Clin Med Kaz 2024, 21, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagge, C.N.; Henderson, V.W.; Laursen, H.B.; Adelborg, K.; Olsen, M.; Madsen, N.L. Risk of Dementia in Adults With Congenital Heart Disease: Population-Based Cohort Study. Circulation 2018, 137, 1912–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagge, C.N.; Smit, J.; Madsen, N.L.; Olsen, M. Congenital Heart Disease and Risk of Central Nervous System Infections: A Nationwide Cohort Study. Pediatr Cardiol 2020, 41, 869–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, N.L.; Marino, B.S.; Woo, J.G.; Thomsen, R.W.; Videbœk, J.; Laursen, H.B.; Olsen, M. Congenital Heart Disease With and Without Cyanotic Potential and the Long-term Risk of Diabetes Mellitus: A Population-Based Follow-up Study. J Am Heart Assoc 2016, 5, e003076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, S.; Olsen, M.; Woo, J.G.; Madsen, N. Congenital heart disease and the prevalence of underweight and obesity from age 1 to 15 years: data on a nationwide sample of children. BMJ Paediatr Open 2017, 1, e000127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayfokru, A.; Shewasinad, S.; Ahmed, F.; Tefera, M.; Nigussie, G.; Getaneh, E.; Mengstie, L.A.; Teklehaimanot, W.Z.; Seyoum, W.A.; Gebeyehu, M.T.; Alemnew, M.; Girma, B. Incidence and predictors of mortality among neonates with congenital heart disease in Ethiopia: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Pediatr 2024, 24, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jivanji, S.G.M.; Lubega, S.; Reel, B.; Qureshi, S.A. Congenital Heart Disease in East Africa. Front Pediatr 2019, 7, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mat Bah, M.N.; Kasim, A.S.; Sapian, M.H.; Alias, E.Y. Survival outcomes for congenital heart disease from Southern Malaysia: results from a congenital heart disease registry. Arch Dis Child 2024, 109, 363–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çaylan, N.; Yalçin, S.S.; Tezel, B.; Üner, O.; Aydin, Ş.; Kara, F. Investigation of infant deaths associated with critical congenital heart diseases; 2018-2021, Türkiye. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, S.A.V.D.A.; Guimarães, I.C.B.; Costa, S.F.O.; Acosta, A.X.; Sandes, K.A.; Mendes, C.M.C. Mortality for Critical Congenital Heart Diseases and Associated Risk Factors in Newborns. A Cohort Study. Arq Bras Cardiol 2018, 111, 666–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, K.N.; Morris, S.A.; Sexson Tejtel, S.K.; Espaillat, A.; Salemi, J.L. US Mortality Attributable to Congenital Heart Disease Across the Lifespan From 1999 Through 2017 Exposes Persistent Racial/Ethnic Disparities. Circulation 2020, 142, 1132–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downing, K.F.; Nembhard, W.N.; Rose, C.E.; Andrews, J.G.; Goudie, A.; Klewer, S.E.; Oster, M.E.; Farr, S.L. Survival From Birth Until Young Adulthood Among Individuals With Congenital Heart Defects: CH STRONG. Circulation 2023, 148, 575–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimeno, L.; Brown, K.; Harron, K.; Peppa, M.; Gilbert, R.; Blackburn, R. Trends in survival of children with severe congenital heart defects by gestational age at birth: A population-based study using administrative hospital data for England. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2023, 37, 390–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protopapas, E.; Padalino, M.; Tobota, Z.; Ebels, T.; Speggiorin, S.; Horer, J.; Kansy, A.; Jacobs, J.P.; Fragata, J.; Maruszewski, B.; Vida, V.; Sarris, G. The European Congenital Heart Surgeons Association congenital cardiac database: A 25-year summary of congenital heart surgery outcomes†. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2025, 67, ezaf119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steurer, M.A.; Baer, R.J.; Chambers, C.D.; Costello, J.; Franck, L.S.; McKenzie-Sampson, S.; Pacheco-Werner, T.L.; Rajagopal, S.; Rogers, E.E.; Rand, L.; Jelliffe-Pawlowski, L.L.; Peyvandi, S. Mortality and Major Neonatal Morbidity in Preterm Infants with Serious Congenital Heart Disease. J Pediatr 2021, 239, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aly, S.; Qattea, I.; Kattea, M.O.; Aly, H.Z. Neonatal outcomes in preterm infants with severe congenital heart disease: a national cohort analysis. Front Pediatr 2024, 12, 1326804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laas, E.; Lelong, N.; Ancel, P.Y.; Bonnet, D.; Houyel, L.; Magny, J.F.; Andrieu, T.; Goffinet, F. Khoshnood B; EPICARD study group. Impact of preterm birth on infant mortality for newborns with congenital heart defects: The EPICARD population-based cohort study. BMC Pediatr 2017, 17, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, B.V.; Levy, P.T.; Ball, M.K.; Kim, M.; Peyvandi, S.; Steurer, M.A. Double Jeopardy: A Distinct Mortality Pattern Among Preterm Infants with Congenital Heart Disease. Pediatr Cardiol 2025, 46, 939–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norman, M.; Håkansson, S.; Kusuda, S.; Vento, M.; Lehtonen, L.; Reichman, B.; Darlow, B.A.; Adams, M.; Bassler, D.; Isayama, T.; Rusconi, F.; Lee, S.; Lui, K.; Yang, J.; Shah, P. S; International Network for Evaluation of Outcomes in Neonates (iNeo) Investigators* †. Neonatal Outcomes in Very Preterm Infants With Severe Congenital Heart Defects: An International Cohort Study. J Am Heart Assoc 2020, 9, e015369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma, A.; Morais, S.; Silva, P.V.; Pires, A. Congenital heart defects and preterm birth: Outcomes from a referral center. Rev Port Cardiol 2023, 42, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arriola-Montenegro, J.; Coronado-Quispe, J.; Mego, J.C.; Luis-Ybáñez, O.; Tauma-Arrué, A.; Chavez-Saldivar, S.; Sierra-Pagan, J.E.; Pinto-Salinas, M.; Marquez, R.; Arboleda, M.; Niño de Guzman, I.; Vera, L.; Alvarez, C.; Bravo-Jaimes, K. Congenital heart disease-related mortality during the first year of life: The peruvian experience. Int J Cardiol Congenit Heart Dis 2024, 19, 100557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Zou, Z.; Hay, S.I.; Liu, Y.; Li, S.; Chen, H.; Naghavi, M.; Zimmerman, M.S.; Martin, G.R.; Wilner, L.B.; Sable, C.A.; Murray, C.J.L.; Kassebaum, N.J.; Patton, G.C.; Zhang, H. Global, regional, and national time trends in mortality for congenital heart disease, 1990-2019: An age-period-cohort analysis for the Global Burden of Disease 2019 study. EClinicalMedicine 2022, 43, 101249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suluba, E.; Shuwei, L.; Xia, Q.; Mwanga, A. Congenital heart diseases: genetics, non-inherited risk factors, and signaling pathways. Egypt J Med Hum Genet 2020, 21, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuhara, J.; Garg, V. Genetics of congenital heart disease: a narrative review of recent advances and clinical implications. Transl Pediatr 2021, 10, 2366–2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ossa Galvis, M.M.; Bhakta, R.T.; Tarmahomed, A.; et al. Cyanotic Heart Disease. [Updated 2023 Jun 26]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK500001/.

- Zubrzycki, M.; Schramm, R.; Costard-Jäckle, A.; Grohmann, J.; Gummert, J.F.; Zubrzycka, M. Cardiac Development and Factors Influencing the Development of Congenital Heart Defects (CHDs): Part I. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 7117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villamil, V.I.; Downing, K.F.; Oster, M.E.; Andrews, J.G.; Galindo, M.K.; Patel, J.; Klewer, S.E.; Nembhard, W.N.; Farr, S.L. Comorbidities and Healthcare Utilization Among Young Adults With Congenital Heart Defects by Down Syndrome Status-Congenital Heart Survey to Recognize Outcomes, Needs, and wellbeinG, 2016-2019. Birth Defects Res 2025, 117, e2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saliba, A.; Figueiredo, A.C.V.; Baroneza, J.E.; Afiune, J.Y.; Pic-Taylor, A.; Oliveira, S.F.; Mazzeu, J.F. Genetic and genomics in congenital heart disease: a clinical review. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2020, 96, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimopoulos, K.; Constantine, A.; Clift, P.; Condliffe, R.; Moledina, S.; Jansen, K.; Inuzuka, R.; Veldtman, G.R.; Cua, C.L.; Tay, E.L.W.; Opotowsky, A.R.; Giannakoulas, G.; Alonso-Gonzalez, R.; Cordina, R.; Capone, G.; Namuyonga, J.; Scott, C.H.; D'Alto, M.; Gamero, F.J.; Chicoine, B.; Gu, H.; Limsuwan, A.; Majekodunmi, T.; Budts, W.; Coghlan, G.; Broberg, C. S; for Down Syndrome International (DSi). Cardiovascular Complications of Down Syndrome: Scoping Review and Expert Consensus. Circulation 2023, 147, 425–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geleta, B.E.; Seyoum, G. Prevalence and Patterns of Congenital Heart Defects and Other Major Non-Syndromic Congenital Anomalies Among Down Syndrome Patients: A Retrospective Study. Int J Gen Med 2024, 17, 1337–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dodge-Khatami, A.; Herger, S.; Rousson, V.; Comber, M.; Knirsch, W.; Bauersfeld, U.; Prêtre, R. Outcomes and reoperations after total correction of complete atrio-ventricular septal defect. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2008, 34, 745–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuechner, A.; Mhada, T.; Majani, N.G.; Sharau, G.G.; Mahalu, W.; Freund, M.W. Spectrum of heart diseases in children presenting to a paediatric cardiac echocardiography clinic in the Lake Zone of Tanzania: a 7 years overview. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2019, 19, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaidi, S.; Brueckner, M. Genetics and Genomics of Congenital Heart Disease. Circ Res 2017, 120, 923–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namuyonga, J.; Lubega, S.; Aliku, T.; Omagino, J.; Sable, C.; Lwabi, P. Pattern of congenital heart disease among children presenting to the Uganda Heart Institute, Mulago Hospital: a 7-year review. Afr Health Sci 2020, 20, 745–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomford, N.E.; Biney, R.P.; Okai, E.; Anyanful, A.; Nsiah, P.; Frimpong, P.G.; Boakye, D.O.; Adongo, C.A.; Kruszka, P.; Wonkam, A. Clinical Spectrum of congenital heart defects (CHD) detected at the child health Clinic in a Tertiary Health Facility in Ghana: a retrospective analysis. J Congenit Heart Dis 2020, 4, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majani, N.G.; Koster, J.R.; Kalezi, Z.E.; Letara, N.; Nkya, D.; Mongela, S.; Kubhoja, S.; Sharau, G.; Mlawi, V.; Grobbee, D.E.; Slieker, M.G.; Chillo, P.; Janabi, M.; Kisenge, P. Spectrum of Heart Diseases in Children in a National Cardiac Referral Center Tanzania, Eastern Africa: A Six-Year Overview. Glob Heart 2024, 19, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugnaloni, F.; Felici, A.; Corno, A.F.; Marino, B.; Versacci, P.; Putotto, C. Gender differences in congenital heart defects: a narrative review. Transl Pediatr 2023, 12, 1753–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freilinger, S.; Andonian, C.; Beckmann, J.; Ewert, P.; Kaemmerer, H.; Lang, N.; Nagdyman, N.; Oberhoffer-Fritz, R.; Pieper, L.; Schelling, J.; von Scheidt, F.; Neidenbach, R. Differences in the experiences and perceptions of men and women with congenital heart defects: A call for gender-sensitive, specialized, and integrative care. Int J Cardiol Congenital Heart Dis 2021, 4, 100185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachamadugu, S.I.; Miller, K.A.; Lee, I.H.; Zou, Y.S. Genetic detection of congenital heart disease. Gynecol Obstet Clin Med 2022, 2, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhatwal, K.; Smith, J.J.; Bola, H.; Zahid, A.; Venkatakrishnan, A.; Brand, T. Uncovering the Genetic Basis of Congenital Heart Disease: Recent Advancements and Implications for Clinical Management. CJC Pediatr Congenit Heart Dis 2023, 2(6Part B), 464–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sevim Bayrak, C.; Zhang, P.; Tristani-Firouzi, M.; Gelb, B.D.; Itan, Y. De novo variants in exomes of congenital heart disease patients identify risk genes and pathways. Genome Med 2020, 12, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Øyen, N.; Boyd, H.A.; Carstensen, L.; Søndergaard, L.; Wohlfahrt, J.; Melbye, M. Risk of Congenital Heart Defects in Offspring of Affected Mothers and Fathers. Circ Genom Precis Med 2022, 15, e003533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, S.; Rama Sastry, U.M.; Mahimaiha, J.; Subramanian, A.P.; Shankarappa, R.K.; Nanjappa, M.C. Spectrum of cyanotic congenital heart disease diagnosed by echocardiographic evaluation in patients attending paediatric cardiology clinic of a tertiary cardiac care centre. Cardiol Young 2015, 25, 861–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahid, S.; Khurram, H.; Lim, A.; Shabbir, M.F.; Billah, B. Prediction of cyanotic and acyanotic congenital heart disease using machine learning models. World J Clin Pediatr 2024, 13, 98472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammad, M.; James, A.F.; Qureshi, R.S.; Saraf, S.; Ahluwalia, T.; Mukherji, J.D.; Kole, T. Acute ischemic stroke in a child with cyanotic congenital heart disease due to non-compliance of anticoagulation. World J Emerg Med 2012, 3, 154–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manuel, V.; Miana, L.A.; Solla, D.J.F.; Fernandes, N.; Carrillo, G.; Jatene, M.B. Preoperative level of neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio: Comparison between cyanotic and acyanotic congenital heart disease. J Card Surg 2021, 36, 1376–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downing, K.F.; Oster, M.E.; Klewer, S.E.; Rose, C.E.; Nembhard, W.N.; Andrews, J.G.; Farr, S.L. Disability Among Young Adults With Congenital Heart Defects: Congenital Heart Survey to Recognize Outcomes, Needs, and Well-Being 2016-2019. J Am Heart Assoc 2021, 10, e022440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosig, C.L.; Bear, L.; Allen, S.; Hoffmann, R.G.; Pan, A.; Frommelt, M.; Mussatto, K.A. Preschool Neurodevelopmental Outcomes in Children with Congenital Heart Disease. J Pediatr 2017, 183, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, M.; Chattopadhyay, A.; Gupta, S.K.; Jain, S.; Sastry, U.M.K.; Sudevan, R.; Sharma, M.; Pragya, P.; Shivashankar, R.; Sudhakar, A.; Radhakrishnan, A.; Parveen, S.; Patil, S.; Naik, S.; Das, S.; Kumar, R.K. Neurodevelopmental outcomes after infant heart surgery for congenital heart disease: a hospital-based multicentre prospective cohort study from India. BMJ Paediatr Open 2025, 9, e002943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, B.R.; Rogers, L.S.; Kirschen, M.P. Recent advances in our understanding of neurodevelopmental outcomes in congenital heart disease. Curr Opin Pediatr 2019, 31, 783–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farr, S.L.; Downing, K.F.; Tepper, N.K.; Oster, M.E.; Glidewell, M.J.; Reefhuis, J. Reproductive Health of Women with Congenital Heart Defects. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2023, 32, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Song, M.; Zhang, K.; Lu, W.; Li, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Y. Congenital heart disease: types, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment options. MedComm (2020) 2024, 5, e631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, C.; Wu, C.; Pan, Z.; Li, Y. Minimally invasive closure of transthoracic ventricular septal defect: postoperative complications and risk factors. J Cardiothorac Surg 2021, 16, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, M.E.; Bouhout, I.; Petit, C.J.; Kalfa, D. Transcatheter Closure of Atrial and Ventricular Septal Defects: JACC Focus Seminar. J Am Coll Cardiol 2022, 79, 2247–2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elafifi, A.; Kotit, S.; Shehata, M.; Deyaa, O.; Ramadan, A.; Tawfik, M. Early experience with transcatheter ventricular septal defects closure with the KONAR-MF multifunctional occluder. Front Pediatr 2025, 13, 1528490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diab, K.A.; Cao, Q.L.; Hijazi, Z.M. Perventricular closure of muscular ventricular septal defects: How do I do it? Ann Pediatr Cardiol 2008, 1, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bah, M.N.M.; Sapian, M.H.; Anuar, M.H.M.; Alias, E.Y. Survival and outcomes of isolated neonatal ventricular septal defects: A population-based study from a middle-income country. Ann Pediatr Cardiol 2023, 16, 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihl, C.; Sillesen, A.S.; Norsk, J.B.; Vøgg, R.O.B.; Vedel, C.; Boyd, H.A.; Vejlstrup, N.; Axelsson Raja, A.; Bundgaard, H.; Iversen, K.K. The Prevalence and Spontaneous Closure of Ventricular Septal Defects the First Year of Life. Neonatology 2024, 121, 742–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durden, R.E.; Turek, J.W.; Reinking, B.E.; Bansal, M. Acquired ventricular septal defect due to infective endocarditis. Ann Pediatr Cardiol 2018, 11, 100–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabiniewicz, R.; Huczek, Z.; Zbroński, K.; Scisło, P.; Rymuza, B.; Kochman, J.; Marć, M.; Grygier, M.; Araszkiewicz, A.; Dziarmaga, M.; Leśniewicz, P.; Hiczkiewicz, J.; Kidawa, M.; Filipiak, K.J.; Opolski, G. Percutaneous Closure of Post-Infarction Ventricular Septal Defects-An Over Decade-long Experience. J Interv Cardiol 2017, 30, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khajali, Z.; Firouzi, A.; Jorfi, F.; Keshavarz Hedayati, M. Device closure of a traumatic VSD in a young man with a history of a stab wound to the chest. J Cardiol Cases 2020, 21, 217–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zughaib, M.T.; LaVoie, J.; Multani, N.; Darda, S. An Incidental Case of a Rare Ventricular Septal Defect (VSD): Does Infective Endocarditis Ger-Bode Well? Cureus 2024, 16, e60677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinteză, E.E.; Butera, G. Complex ventricular septal defects. Update on percutaneous closure. Rom J Morphol Embryol 2016, 57, 1195–1205. [Google Scholar]

- Mainzer, G.; Rosenthal, E.; Austin, C.; Morgan, G. Hybrid Approach for Recanalization and Stenting of Acquired Pulmonary Vein Occlusion. Pediatr Cardiol 2016, 37, 983–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.M.; Niu, C.; Liu, F.; Wu, L.; Ma, X.J.; Huang, G.Y. Spontaneous Closure Rates of Ventricular Septal Defects (6,750 Consecutive Neonates). Am J Cardiol 2019, 124, 613–617, Erratum in: Am J Cardiol 2020, 125(2), 302. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2019.10.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, L.; Houyel, L.; Colan, S.D.; Anderson, R.H.; Béland, M.J.; Aiello, V.D.; Bailliard, F.; Cohen, M.S.; Jacobs, J.P.; Kurosawa, H.; Sanders, S.P.; Walters, H.L. 3rd.; Weinberg P.M.; Boris J.R.; Cook A.C.; Crucean A.; Everett A.D.; Gaynor J.W.; Giroud J.; Guleserian K.J.; Hughes M.L.; Juraszek A.L.; Krogmann O.N.; Maruszewski B.J.; St Louis J.D.; Seslar S.P.; Spicer D.E.; Srivastava S.; Stellin G.; Tchervenkov C.I.; Wang L.; Franklin R.C.G. Classification of Ventricular Septal Defects for the Eleventh Iteration of the International Classification of Diseases-Striving for Consensus: A Report From the International Society for Nomenclature of Paediatric and Congenital Heart Disease. Ann Thorac Surg 2018, 106, 1578–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.X.; Wang, J.H.; Yang, S.R.; Liu, M.; Xu, Y.; Sun, J.H.; Yan, C.Y. Clinical utility of the ventricular septal defect diameter to aorta root diameter ratio to predict early childhood developmental defects or lung infections in patients with perimembranous ventricular septal defect. J Thorac Dis 2013, 5, 600–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradian, M.; Alizadehasl, A. Ventricular Septal Defect (VSD). In: Moradian, M., Alizadehasl, A. (eds) Atlas of Echocardiography in Pediatrics and Congenital Heart Diseases. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Mladenova, M.K.; Bakardzhiev, I.V.; Hadji Lega, M.; Lingman, G. Apparently isolated ventricular septal defect, prenatal diagnosis, association with chromosomal aberrations, spontaneous closure rate in utero and during the first year of life: a systematic review. Folia Med (Plovdiv) 2023, 65, 871–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.Y.; Tchah, N.; Lin, C.Y.; Park, J.M.; Woo, W.; Kim, C.S.; Jung, S.Y.; Choi, J.Y.; Jung, J.W. Predictive Scoring System for Spontaneous Closure of Infant Ventricular Septal Defect: The P-VSD Score. Pediatr Cardiol 2025, 46, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, Q.; Lu, M.; Feng, Q.; Qin, L.; Liao, S. Prenatal finding of isolated ventricular septal defect: genetic association, outcomes and counseling. Front Genet 2024, 15, 1447216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bride, P.; Kaestner, M.; Radermacher, M.; Vitanova, K.; von Scheidt, F.; Scharnbeck, D.; Apitz, C. Spontaneous Closure of Perimembranous Ventricular Septal Defects: A Janus-Faced Condition. CASE (Phila) 2019, 4, 103–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adilbekova, A.; Marasulov, S.; Nurkeyev, B.; Kozhakhmetov, S. Evolution of surgery of ventricular septal defect closure. J Clin Med Kaz 2022, 19, 4–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, R.G.; Menon, S.C.; Johnson, J.T.; Armstrong, A.K.; Bingler, M.A.; Breinholt, J.P.; Kenny, D.; Lozier, J.; Murphy, J.J.; Sathanandam, S.K.; Taggart, N.W.; Trucco, S.M.; Goldstein, B.H.; Gordon, B.M. Acute and midterm results following perventricular device closure of muscular ventricular septal defects: A multicenter PICES investigation. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2017, 90, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.L.; Tometzki, A.; Caputo, M.; Morgan, G.; Parry, A.; Martin, R. Longer-term outcome of perventricular device closure of muscular ventricular septal defects in children. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2015, 85, 998–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, M.; Germann, C.P.; Nordmeyer, J.; Peters, B.; Berger, F.; Schubert, S. Short- and Long-term Outcome After Interventional VSD Closure: A Single-Center Experience in Pediatric and Adult Patients. Pediatr Cardiol 2021, 42, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küçükosmanoğlu, M.; Koç, A.S.; Sümbül, H.E.; Koca, H.; Çakır Pekoz, B.; Koç, M. Liver stiffness value obtained by point shear-wave elastography is significantly related with atrial septal defect size. Diagn Interv Radiol 2020, 26, 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinteza, E.; Vasile, C.M.; Busnatu, S.; Armat, I.; Spinu, A.D.; Vatasescu, R.; Duica, G.; Nicolescu, A. Can Artificial Intelligence Revolutionize the Diagnosis and Management of the Atrial Septal Defect in Children? Diagnostics (Basel) 2024, 14, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraisse, A.; Latchman, M.; Sharma, S.R.; Bayburt, S.; Amedro, P.; di Salvo, G.; Baruteau, A.E. Atrial septal defect closure: indications and contra-indications. J Thorac Dis 2018, 10 (Suppl 24), S2874–S2881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menillo, A.M.; Alahmadi, M.H.; Pearson-Shaver, A.L. Atrial Septal Defect. [Updated 2025 Jan 21]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK535440/.

- Rodríguez Fernández, A.; Bethencourt González, A. Imaging Techniques in Percutaneous Cardiac Structural Interventions: Atrial Septal Defect Closure and Left Atrial Appendage Occlusion. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed) 2016, 69, 766–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, R.J.; Love, B.A.; Paolillo, J.A.; Gray, R.G.; Goldstein, B.H.; Morgan, G.J.; Gillespie, M. J; ASSURED Investigators. ASSURED clinical study: New GORE® CARDIOFORM ASD occluder for transcatheter closure of atrial septal defect. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2020, 95, 1285–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brancato, F.; Stephenson, N.; Rosenthal, E.; Hansen, J.H.; Jones, M.I.; Qureshi, S.; Austin, C.; Speggiorin, S.; Caner, S.; Butera, G. Transcatheter versus surgical treatment for isolated superior sinus venosus atrial septal defect. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2023, 101, 1098–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pekoz, B.C.; Koc, M.; Kucukosmanoglu, M.; Koc, A.S.; Koca, H.; Dönmez, Y.; Sumbul, H.E. Evaluation of Liver Stiffness After Atrial Septal Defect Closure. Ultrasound Q 2022, 38, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thingnam, S.K.S.; Mahajan, S.; Kumar, V. Surgical perspective of percutaneous device closure of atrial septal defect. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann 2018, 26, 343–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adhikari, C.M.; Bogati, A.; Prajapati, D.; Dhungel, S.; Najmy, S.; Acharya, K.; Shahi, R.; Subedi, C.; Adhikari, J.; Sharma, D. Atrial Septal Defect Size and Rims on Transesophageal Echocardiogram. Maedica (Bucur) 2019, 14, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, F.; Hameed, M.; Hanif, B.; Aijaz, S. Outcomes and complications of percutaneous device closure in adults with secundum atrial septal defect. J Pak Med Assoc 2022, 72, 385–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, G.B.; Brindis, R.G.; Krucoff, M.W.; Mansalis, B.P.; Carroll, J.D. Percutaneous atrial septal occluder devices and cardiac erosion: a review of the literature. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2012, 80, 157–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendirichaga, R.; Smairat, R.A.; Sancassani, R. Late tissue erosion after transcatheter closure of an atrial septal defect. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2017, 89, 502–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, T.; Tsukano, S.; Tosaka, Y. Pericardial tamponade due to erosion of a Figulla Flex II device after closure of an atrial septal defect. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2019, 94, 1003–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava, S.; Shrivastava, S.; Allu, S.V.V.; Schmidt, P. Transcatheter Closure of Atrial Septal Defect: A Review of Currently Used Devices. Cureus 2023, 15, e40132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hribernik, I.; Thomson, J.; Bhan, A.; Mullen, M.; Noonan, P.; Smith, B.; Walker, N.; Deri, A.; Bentham, J. A novel device for atrial septal defect occlusion (GORE CARDIOFORM). EuroIntervention 2023, 19, 782–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, A.M.; Sommer, R.J.; Morgan, G.; Paolillo, J.A.; Gray, R.G.; Love, B.; Goldstein, B.H.; Sugeng, L.; Gillespie, M. J; GORE ASSURED Clinical Trial Investigators. Long-Term Results of the Atrial Septal Defect Occluder ASSURED Trial for Combined Pivotal/Continued Access Cohorts. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2024, 17, 2274–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Yoon, S.J.; Han, J.; Song, I.G.; Lim, J.; Shin, J.E.; Eun, H.S.; Park, K.I.; Park, M.S.; Lee, S.M. Patent ductus arteriosus treatment trends and associated morbidities in neonates. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 10689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khowaja, W.; Akhtar, S.; Jiwani, U.; Mohsin, M.; Shaheen, F.; Ariff, S. Outcomes of preterm neonates with patent ductus arteriosus: A retrospective review from a tertiary care hospital. J Pak Med Assoc 2022, 72, 2065–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillam-Krakauer, M.; Mahajan, K. Patent Ductus Arteriosus. [Updated 2023 Aug 8]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430758/.

- Morville, P.; Akhavi, A. Transcatheter closure of hemodynamic significant patent ductus arteriosus in 32 premature infants by amplatzer ductal occluder additional size-ADOIIAS. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2017, 90, 612–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.N.; Lin, Y.C.; Hsieh, M.L.; Wei, Y.J.; Ju, Y.T.; Wu, J.M. Transcatheter Closure of Patent Ductus Arteriosus in Premature Infants With Very Low Birth Weight. Front Pediatr 2021, 8, 615919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomasulo, C.E.; Gillespie, M.J.; Munson, D.; Demkin, T.; O'Byrne, M.L.; Dori, Y.; Smith, C.L.; Rome, J.J.; Glatz, A.C. Incidence and fate of device-related left pulmonary artery stenosis and aortic coarctation in small infants undergoing transcatheter patent ductus arteriosus closure. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2020, 96, 889–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellmer, A.; Bjerre, J.V.; Schmidt, M.R.; McNamara, P.J.; Hjortdal, V.E.; Høst, B.; Bech, B.H.; Henriksen, T.B. Morbidity and mortality in preterm neonates with patent ductus arteriosus on day 3. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2013, 98, F505–F510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terrin, G.; Di Chiara, M.; Boscarino, G.; Metrangolo, V.; Faccioli, F.; Onestà, E.; Giancotti, A.; Di Donato, V.; Cardilli, V.; De Curtis, M. Morbidity associated with patent ductus arteriosus in preterm newborns: a retrospective case-control study. Ital J Pediatr 2021, 47, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozé, J.C.; Cambonie, G.; Marchand-Martin, L.; Gournay, V.; Durrmeyer, X.; Durox, M.; Storme, L.; Porcher, R.; Ancel, P. Y; Hemodynamic EPIPAGE 2 Study Group. Association Between Early Screening for Patent Ductus Arteriosus and In-Hospital Mortality Among Extremely Preterm Infants. JAMA 2015, 313, 2441–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission EUROCAT Prevalence charts and tables. Last update in April 2025. Available online: https://eu-rd-platform.jrc.ec.europa.eu/eurocat/eurocat-data/prevalence_en (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Aldersley, T.; Lawrenson, J.; Human, P.; Shaboodien, G.; Cupido, B.; Comitis, G.; De Decker, R.; Fourie, B.; Swanson, L.; Joachim, A.; Magadla, P.; Ngoepe, M.; Swanson, L.; Revell, A.; Ramesar, R.; Brooks, A.; Saacks, N.; De Koning, B.; Sliwa, K.; Anthony, J.; Osman, A.; Keavney, B.; Zühlke, L. PROTEA.; A Southern African Multicenter Congenital Heart Disease Registry and Biorepository: Rationale, Design, and Initial Results. Front Pediatr 2021, 9, 763060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulkadir, M.; Abdulkadir, Z. A systematic review of trends and patterns of congenital heart disease in children in Nigeria from 1964-2015. Afr Health Sci 2016, 16, 367–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, C.; Strange, G.; Ayer, J.; Cheung, M.; Grigg, L.; Justo, R.; Maxwell, R.; Wheaton, G.; Disney, P.; Yim, D.; Stewart, S.; Cordina, R.; Celermajer, D.S. A national Australian Congenital Heart Disease registry; methods and initial results. Int J Cardiol Congenit Heart Dis 2024, 17, 100538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, G.; Zhang, H.; Zheng, S.; Wang, W.; Ma, L. Mid-term Outcomes of Common Congenital Heart Defects Corrected Through a Right Subaxillary Thoracotomy. Heart Lung Circ 2017, 26, 376–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadeta, D.; Guteta, S.; Alemayehu, B.; Mekonnen, D.; Gedlu, E.; Benti, H.; Tesfaye, H.; Berhane, S.; Hailu, A.; Luel, A.; Hailu, T.; Daniel, W.; Haileamlak, A.; Gudina, E.K.; Negeri, G.; Mekonnen, D.; Woubeshet, K.; Egeno, T.; Lemma, K.; Kshettry, V.R.; Tefera, E. Spectrum of cardiovascular diseases in six main referral hospitals of Ethiopia. Heart Asia 2017, 9, e010829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giraldo-Grueso, M.; Zarante, I.; Mejía-Grueso, A.; Gracia, A. Risk factors for congenital heart disease: A case-control study. Revista Colombiana de Cardiología 2020, 27, 324–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwin, F.; Zühlke, L.; Farouk, H.; Mocumbi, A.O.; Entsua-Mensah, K.; Delsol-Gyan, D.; Bode-Thomas, F.; Brooks, A.; Cupido, B.; Tettey, M.; Aniteye, E.; Tamatey, M.M.; Gyan, K.B.; Tchoumi, J.C.T.; Elgamal, M.A. Status and Challenges of Care in Africa for Adults With Congenital Heart Defects. World J Pediatr Congenit Heart Surg 2017, 8, 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eshetu, M.A.; Goshu, D.Y.; Kebede, M.A.; Negate, H.M.; Habtezghi, A.B.; Gregory, P.M.; Wirtu, A.T.; Gemechu, J.M. Patterns and Complications of Congenital Heart Disease in Adolescents and Adults in Ethiopia. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis 2024, 11, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spicer, D.E.; Hsu, H.H.; Co-Vu, J.; Anderson, R.H.; Fricker, F.J. Ventricular septal defect. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2014, 9, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, M.L.; Jacobs, J.P. Operative Techniques for Repair of Muscular Ventricular Septal Defects. Oper Tech Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2010, 15, 2–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J. Percutaneous Transcatheter Closure of Congenital Ventricular Septal Defects. Korean Circ J 2023, 53, 134–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alakhfash, A.A.; Jelly, A.; Almesned, A.; Alqwaiee, A.; Almutairi, M.; Salah, S.; Hasan, M.; Almuhaya, M.; Alnajjar, A.; Mofeed, M.; Nasser, B. Cardiac Catheterisation Interventions in Neonates and Infants Less Than Three Months. J Saudi Heart Assoc 2020, 32, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, M.L.; Staffa, S.J.; Adams, P.S.; Caplan, L.A.; Gleich, S.J.; Hernandez, J.L.; Richtsfeld, M.; Riegger, L.Q.; Vener, D.F. Intraoperative cardiac arrest in patients undergoing congenital cardiac surgery. JTCVS Open 2024, 22, 427–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minette, M.S.; Sahn, D.J. Ventricular septal defects. Circulation Erratum in: Circulation 2007, 115, e205. 2006, 114, 2190–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, R.H.; Spicer, D.E.; Giroud, J.M.; Mohun, T.J. Tetralogy of Fallot: nosological, morphological, and morphogenetic considerations. Cardiol Young 2013, 23, 858–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morray, B.H. Ventricular Septal Defect Closure Devices, Techniques, and Outcomes. Interv Cardiol Clin 2019, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, G. Closure of Defects in Cardiac Septa. Ann Surg 1948, 128, 843–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, C.P.; Lacy, M.H.; Neptune, W.B.; Weller, R.; Arvanitis, C.S.; Karasic, J. Experimental and clinical attempts at correction of interventricular septal defects. Ann Surg 1952, 136, 919–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay, E.B.; Zimmerman, H.A. Surgical repair of intraventricular septal defects: report of a case. J Am Med Assoc 1954, 154, 986–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillehei, C.W.; Cohen, M.; Warden, H.E.; Ziegler, N.R.; Varco, R.L. The results of direct vision closure of ventricular septal defects in eight patients by means of controlled cross circulation. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1955, 101, 446–66. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lillehei, C.W.; Varco, R.L.; Cohen, M.; Warden, H.E.; Patton, C.; Moller, J.H. The first open-heart repairs of ventricular septal defect, atrioventricular communis, and tetralogy of Fallot using extracorporeal circulation by cross-circulation: a 30-year follow-up. Ann Thorac Surg 1986, 41, 4–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, P.M.; Frye, R.L.; DuShane, J.W.; Burchell, H.B.; Wood, E.H.; Weidman, W.H. Prognosis for patients with ventricular septal defect and severe pulmonary vascular obstructive disease. Circulation 1968, 38, 129–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stirling, G.R.; Stanley, P.H.; Lillehei, C.W. The effects of cardiac bypass and ventriculotomy upon right ventricular function; with report of successful closure of ventricular septal defect by use of atriotomy. Surg Forum 1957, 8, 433–438. [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto, Y. [Clinical studies on open heart surgery in infants with profound hypothermia]. Nihon Geka Hokan 1969, 38, 188–207. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kirklin, J.W.; Dushane, J.W. Repair of ventricular septal defect in infancy. Pediatrics 1961, 27, 961–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigmann, J.M.; Stern, A.M.; Sloan, H.E. Early surgical correction of large ventricular septal defects. Pediatrics 1967, 39, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barratt-Boyes, B.G.; Simpson, M.; Neutze, J.M. Intracardiac surgery in neonates and infants using deep hypothermia with surface cooling and limited cardiopulmonary bypass. Circulation 1971, 43(5 Suppl), I25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barratt-Boyes, B.G.; Neutze, J.M.; Clarkson, P.M.; Shardey, G.C.; Brandt, P.W. Repair of ventricular septal defect in the first two years of life using profound hypothermia-circulatory arrest techniques. Ann Surg 1976, 184, 376–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, T.; Pu, L.; Ma, Y.F.; Zhu, Y.L.; Cui, X.; Li, H.; Zhan, X.; Li, Y.X. Safety of Normothermic Cardiopulmonary Bypass in Pediatric Cardiac Surgery: A System Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Pediatr 2021, 9, 757551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Q.; Wu, Q.; Pan, S.; Ren, Y.; Wan, H. Transthoracic device closure of ventricular septal defects without cardiopulmonary bypass: experience in infants weighting less than 8 kg. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2011, 40, 591–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.S.; Huang, S.T.; Sun, K.P.; Hong, Z.N.; Chen, L.W.; Kuo, Y.R.; Chen, Q. Health-related quality of life in children and adolescents undergoing intraoperative device closure of isolated perimembranous ventricular septal defects in southeastern China. J Cardiothorac Surg 2019, 14, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omelchenko, A.; Jha, N.K.; Shah, N.; AbdelMassih, A.; Montiel, J.P.; Rajkumar, B.R. Perventricular device closure of the ventricular septal defects in children-first experience in the United Arab Emirates. J Cardiothorac Surg 2024, 19, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Tiemuerniyazi, X.; Hu, Z.; Feng, W.; Xu, F. Analysis of cardiac arrest after coronary artery bypass grafting. J Cardiothorac Surg 2024, 19, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squiccimarro, E.; Stasi, A.; Lorusso, R.; Paparella, D. Narrative review of the systemic inflammatory reaction to cardiac surgery and cardiopulmonary bypass. Artif Organs 2022, 46, 568–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Nie, Y.; Qiu, G.; Jiang, Y.; Muthialu, N.; Yang, Z. Risk factors for early secondary infections after cardiopulmonary bypass in children with congenital heart disease: a single-center analysis of 265 cases. Transl Pediatr 2025, 14, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaynor, J.W.; Stopp, C.; Wypij, D.; Andropoulos, D.B.; Atallah, J.; Atz, A.M.; Beca, J.; Donofrio, M.T.; Duncan, K.; Ghanayem, N.S.; Goldberg, C.S.; Hövels-Gürich, H.; Ichida, F.; Jacobs, J.P.; Justo, R.; Latal, B.; Li, J.S.; Mahle, W.T.; McQuillen, P.S.; Menon, S.C.; Pemberton, V.L.; Pike, N.A.; Pizarro, C.; Shekerdemian, L.S.; Synnes, A.; Williams, I.; Bellinger, D.C.; Newburger, J. W; International Cardiac Collaborative on Neurodevelopment (ICCON) Investigators. Neurodevelopmental outcomes after cardiac surgery in infancy. Pediatrics 2015, 135, 816–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naguib, A.N.; Winch, P.D.; Tobias, J.D.; Yeates, K.O.; Miao, Y.; Galantowicz, M.; Hoffman, T.M. Neurodevelopmental outcome after cardiac surgery utilizing cardiopulmonary bypass in children. Saudi J Anaesth 2015, 9, 12–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whiting, D.; Yuki, K.; DiNardo, J.A. Cardiopulmonary bypass in the pediatric population. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 2015, 29, 241–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuda, M.; Takemura, H.; Yamashita, A.; Matsuoka, Y.; Sawa, T.; Amaya, F. Post-surgical chronic pain and quality of life in children operated for congenital heart disease. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2019, 63, 745–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Hoogd, S.; Goulooze, S.C.; Valkenburg, A.J.; Krekels, E.H.J.; van Dijk, M.; Tibboel, D.; Knibbe, C.A.J. Postoperative breakthrough pain in paediatric cardiac surgery not reduced by increased morphine concentrations. Pediatr Res 2021, 90, 1201–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Y.; Pan, B.; Liang, X.; Lv, T.; Tian, J. Health-related quality of life in children with congenital heart disease following interventional closure versus minimally invasive closure. Front Cardiovasc Med 2022, 9, 974720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishaly, D.; Ghosh, P.; Preisman, S. Minimally invasive congenital cardiac surgery through right anterior minithoracotomy approach. Ann Thorac Surg 2008, 85, 831–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Li, Q.; Zhang, J.; Wu, Z.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, D.J. Ventricular septal defects closure using a minimal right vertical infraaxillary thoracotomy: seven-year experience in 274 patients. Ann Thorac Surg 2010, 89, 552–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, A.T.; Vu, T.T.; Nguyen, D.H. Ministernotomy for correction of ventricular septal defect. J Cardiothorac Surg 2016, 11, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinisch, P.P.; Wildbolz, M.; Beck, M.J.; Bartkevics, M.; Gahl, B.; Eberle, B.; Erdoes, G.; Jenni, H.J.; Schoenhoff, F.; Pfammatter, J.P.; Carrel, T.; Kadner, A. Vertical Right Axillary Mini-Thoracotomy for Correction of Ventricular Septal Defects and Complete Atrioventricular Septal Defects. Ann Thorac Surg 2018, 106, 1220–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lock, J.E.; Block, P.C.; McKay, R.G.; Baim, D.S.; Keane, J.F. Transcatheter closure of ventricular septal defects. Circulation 1988, 78, 361–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedra, C.A.; Pedra, S.R.; Esteves, C.A.; Pontes, S.C. Jr.; Braga, S.L.; Arrieta, S.R.; Santana, M.V.; Fontes, V.F.; Masura, J. Percutaneous closure of perimembranous ventricular septal defects with the Amplatzer device: technical and morphological considerations. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2004, 61, 403–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masura, J.; Gao, W.; Gavora, P.; Sun, K.; Zhou, A.Q.; Jiang, S.; Ting-Liang, L.; Wang, Y. Percutaneous closure of perimembranous ventricular septal defects with the eccentric Amplatzer device: multicenter follow-up study. Pediatr Cardiol 2005, 26, 216–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, S.; Mukherji, A.; Chattopadhyay, A. Percutaneous closure of moderate to large perimembranous ventricular septal defect in small children using left ventricular mid-cavity approach. Indian Heart J 2020, 72, 570–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillai, A.A.; Rangasamy, S.; Balasubramonian, V.R. Transcatheter Closure of Moderate to Large Perimembranous Ventricular Septal Defects in Children Weighing 10 kilograms or less. World J Pediatr Congenit Heart Surg 2019, 10, 278–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongwaitaweewong, K.; Promphan, W.; Roymanee, S.; Prachasilchai, P. Effect of transcatheter closure by AmplatzerTM Duct Occluder II in patients with small ventricular septal defect. Cardiovasc Interv Ther 2021, 36, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elmarsafawy, H.; Hafez, M.; Alsawah, G.A.; Bakr, A.; Rakha, S. Long-term outcomes of percutaneous closure of ventricular septal defects in children using different devices: A single centre experience from Egypt. BMC Pediatr 2023, 23, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roymanee, S.; Su-angka, N.; Promphan, W.; Wongwaitaweewong, K.; Jarutach, J.; Buntharikpornpun, R.; Prachasilchai, P. Outcomes of Transcatheter Closure in Outlet-Type Ventricular Septal Defect after 1 Year. Congenit Heart Dis 2023, 18, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, M.M.; Zhao, D.X.M. Percutaneous Post-Myocardial Infarction Ventricular Septal Rupture Closure: A Review. Structural Heart 2018, 2, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saurav, A.; Kaushik, M.; Mahesh Alla, V.; White, M.D.; Satpathy, R.; Lanspa, T.; Mooss, A.N.; DelCore, M.G. Comparison of percutaneous device closure versus surgical closure of peri-membranous ventricular septal defects: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2015, 86, 1048–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, K.; You, T.; Ding, Z.H.; Hou, X.D.; Liu, X.G.; Wang, X.K.; Tian, J.H. Comparison of transcatheter closure, mini-invasive closure, and open-heart surgical repair for treatment of perimembranous ventricular septal defects in children: A PRISMA-compliant network meta-analysis of randomized and observational studies. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018, 97, e12583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, N.C.; Viet, N.L.; Nguyen, H.L.T.; Hien, N.S.; Hung, N.D. Early and mid-term outcomes of transcatheter closure of perimembranous ventricular septal defects using double-disc occluders. Front Cardiovasc Med 2025, 12, 1540595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ece, İ.; Bağrul, D.; Kavurt, A.V.; Terin, H.; Torun, G.; Koca, S.; Gül, A.E.K. Transcatheter Ventricular Septal Defect Closure with Lifetech™ Konar-MF Occluder in Infants Under 10 kg with Only Using Venous Access. Pediatr Cardiol 2024, 45, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.C. Transcatheter device closure of muscular ventricular septal defect. Pediatr Neonatol 2011, 52, 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, R.N.; Rizk, C.; Saliba, Z.; Farah, J. Percutaneous closure of ventricular septal defects in children: key parameters affecting patient radiation exposure. Am J Cardiovasc Dis 2021, 11, 65–72. [Google Scholar]

- Knauth, A.L.; Lock, J.E.; Perry, S.B.; McElhinney, D.B.; Gauvreau, K.; Landzberg, M.J.; Rome, J.J.; Hellenbrand, W.E.; Ruiz, C.E.; Jenkins, K.J. Transcatheter device closure of congenital and postoperative residual ventricular septal defects. Circulation 2004, 110, 501–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Wu, Z.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, H.; Ji, X.; Yi, Q.; Li, M. Unplanned Surgery After Transcatheter Closure of Ventricular Septal Defect in Children: Causes and Risk Factors. Front Pediatr 2021, 9, 772138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, R.N.; Sawan, E.B.; Saliba, Z. Word of caution: Severe aortic valve injury linked to retrograde closure of perimembranous ventricular septal defects. J Card Surg 2022, 37, 1753–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butera, G.; Carminati, M.; Chessa, M.; Piazza, L.; Abella, R.; Negura, D.G.; Giamberti, A.; Claudio, B.; Micheletti, A.; Tammam, Y.; Frigiola, A. Percutaneous closure of ventricular septal defects in children aged <12: early and mid-term results. Eur Heart J 2006, 27, 2889–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butera, G.; Carminati, M.; Chessa, M.; Piazza, L.; Micheletti, A.; Negura, D.G.; Abella, R.; Giamberti, A.; Frigiola, A. Transcatheter closure of perimembranous ventricular septal defects: early and long-term results. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007, 50, 1189–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, I.D. Transcatheter closure of perimembranous ventricular septal defect: is the risk of heart block too high a price? Heart 2007, 93, 284–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Zhao, X.X.; Zheng, X.; Qin, Y.W. Arrhythmias after transcatheter closure of perimembranous ventricular septal defects with a modified double-disk occluder: early and long-term results. Heart Vessels 2012, 27, 405–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weeraman, D.; Hilling-Smith, R.; Dooley, M.; Hildick-Smith, D. Transradial and transfemoral percutaneous closure of iatrogenic perimembranous Ventricular Septal Defects using the Amplatzer AVP IV device. Int J Cardiol 2016, 224, 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samaras, A.; Papadopoulos, K.; Giannakoulas, G.; Tzikas, A. First-in-man transradial percutaneous closure of ventricular septal defect with an Amplatzer Duct Occluder IΙ in an adult patient: a case report. Eur Heart J Case Rep 2023, 7, ytad189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oses, P.; Hugues, N.; Dahdah, N.; Vobecky, S.J.; Miro, J.; Pellerin, M.; Poirier, N.C. Treatment of isolated ventricular septal defects in children: Amplatzer versus surgical closure. Ann Thorac Surg 2010, 90, 1593–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejada García, J.; Lara Lezama, L.B.; de la Fuente Blanco, R.; Pérez de Prado, A.; Benavente Fernández, L.; Rico Santos, M.; Fernández Couto, M.D.; Naya Ríos, L.; Couso Pazó, I.; Alba, P.V.; Redondo-Robles, L.; López Mesonero, L.; Arias-Rivas, S.; Santamaría Cadavid, M.; Tejada Meza, H.; Horna Cañete, L.; Azkune Calle, I.; Pinedo Brochado, A.; García Sánchez, J.M.; Caballero Romero, I.; Freijo Guerrero, M.M.; Luna Rodríguez, A.; de Lera-Alfonso, M.; Arenillas Lara, J.F.; Pérez Lázaro, C.; Navarro Pérez, M.P.; Martínez Zabaleta, M. Selection of patients for percutaneous closure in nonlacunar cryptogenic stroke associated with patent foramen ovale. Data from the NORDICTUS cooperative registry. Neurologia (Engl Ed) 2025, 40, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, R.N. Transcatheter treatment of perimembranous ventricular septal defects: challenges, controversies, and a paradigm shift. Future Cardiol 2025, 21, 551–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishberger, S.B.; Bridges, N.D.; Keane, J.F.; Hanley, F.L.; Jonas, R.A.; Mayer, J.E.; Castaneda, A.R.; Lock, J.E. Intraoperative device closure of ventricular septal defects. Circulation 1993, 88(5 Pt 2), II205–9. [Google Scholar]

- Murzi, B.; Bonanomi, G.L.; Giusti, S.; Luisi, V.S.; Bernabei, M.; Carminati, M.; Vanini, V. Surgical closure of muscular ventricular septal defects using double umbrella devices (intraoperative VSD device closure). Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 1997, 12, 450–454, discussion 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okubo, M.; Benson, L.N.; Nykanen, D.; Azakie, A.; Van Arsdell, G.; Coles, J.; Williams, W.G. Outcomes of intraoperative device closure of muscular ventricular septal defects. Ann Thorac Surg 2001, 72, 416–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaturvedi, R.R.; Shore, D.F.; Yacoub, M.; Redington, A.N. Intraoperative apical ventricular septal defect closure using a modified Rashkind double umbrella. Heart 1996, 76, 367–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, Z.; Berry, J.M.; Foker, J.E.; Rocchini, A.P.; Bass, J.L. Intraoperative closure of muscular ventricular septal defect in a canine model and application of the technique in a baby. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1998, 115, 1374–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, A.B.; Green, J.; Bergdall, V.; Yu, J.; Monreal, G.; Gerhardt, M.; Cheatham, J.P.; Galantowicz, M.; Holzer, R.J. Teaching the "hybrid approach": a novel swine model of muscular ventricular septal defect. Pediatr Cardiol 2009, 30, 114–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratnayaka, K.; Saikus, C.E.; Faranesh, A.Z.; Bell, J.A.; Barbash, I.M.; Kocaturk, O.; Reyes, C.A.; Sonmez, M.; Schenke, W.H.; Wright, V.J.; Hansen, M.S.; Slack, M.C.; Lederman, R.J. Closed-chest transthoracic magnetic resonance imaging-guided ventricular septal defect closure in swine. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2011, 4, 1326–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, A.B.; Carlson, J.A.; Nelson, D.A.; Gordon, S.G.; Miller, M.W. Hybrid technique for ventricular septal defect closure in a dog using an Amplatzer® Duct Occluder II. J Vet Cardiol 2013, 15, 217–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacha, E.A.; Marshall, A.C.; McElhinney, D.B.; del Nido, P.J. Expanding the hybrid concept in congenital heart surgery. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg Pediatr Card Surg Annu 2007, 146–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossland, D.S.; Wilkinson, J.L.; Cochrane, A.D.; d'Udekem, Y.; Brizard, C.P.; Lane, G.K. Initial results of primary device closure of large muscular ventricular septal defects in early infancy using perventricular access. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2008, 72, 386–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bacha, E.A.; Cao, Q.L.; Starr, J.P.; Waight, D.; Ebeid, M.R.; Hijazi, Z.M. Perventricular device closure of muscular ventricular septal defects on the beating heart: technique and results. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2003, 126, 1718–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing, Q.; Pan, S.; An, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Li, J.; Li, F.; Wu, Q.; Zhuang, Z. Minimally invasive perventricular device closure of perimembranous ventricular septal defect without cardiopulmonary bypass: multicenter experience and mid-term follow-up. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2010, 139, 1409–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, C.; An, Q.; Lin, K.; Tang, H.; Lui, R.C.; Tao, K.; Pan, W.; Shi, Y. Perventricular device closure of ventricular septal defects: six months results in 30 young children. Ann Thorac Surg 2008, 86, 142–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakkar, B.; Patel, N.; Shah, S.; Poptani, V.; Madan, T.; Shah, C.; Shukla, A.; Prajapati, V. Perventricular device closure of isolated muscular ventricular septal defect in infants: a single centre experience. Indian Heart J 2012, 64, 559–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.; Tanidir, I.C.; Ye, D.; Zhang, X.; Li, B.; Zhu, D.; Deng, G.; Chen, H. Hybrid Transthoracic Periventricular Device Closure of Ventricular Septal Defects: Single- Center Experience. Braz J Cardiovasc Surg 2021, 36, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.L.; Chen, M.; Zeng, C.; Su, C.X.; Jiang, C.L.; Zheng, B.S.; Wu, J.; Li, S.K. Comparison of perventricular and percutaneous ultrasound-guided device closure of perimembranous ventricular septal defects. Front Cardiovasc Med 2023, 10, 1281860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Changwe, G.J.; Hongxin, L.; Zhang, H.Z.; Wenbin, G.; Liang, F.; Cao, X.X.; Chen, S.L. Percardiac closure of large apical ventricular septal defects in infants: Novel modifications and mid-term results. J Card Surg 2021, 36, 928–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.S.; Luo, Z.R.; Chen, Q.; Yu, L.S.; Cao, H.; Chen, L.W.; Zhang, G.C. A Comparative Study of Perventricular and Percutaneous Device Closure Treatments for Isolated Ventricular Septal Defect: A Chinese Single-Institution Experience. Braz J Cardiovasc Surg 2019, 34, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, R.N.; Gaudin, R.; Bonnet, D.; Malekzadeh-Milani, S. Hybrid perventricular muscular ventricular septal defect closure using the new multi-functional occluder. Cardiol Young 2020, 30, 1517–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleuziou, J.; Georgiev, S.; Heinisch, P.P.; Ewert, P.; Hörer, J. Transventricular ventricular septal defect closure with device as hybrid procedure in complex congenital cardiac surgery. JTCVS Tech 2024, 26, 79–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ueyama, H.A.; Leshnower, B.G.; Inci, E.K.; Keeling, W.B.; Tully, A.; Guyton, R.A.; Xie, J.X.; Gleason, P.T.; Byku, I.; Devireddy, C.M.; Hanzel, G.S.; Block, P.C.; Lederman, R.J.; Greenbaum, A.B.; Babaliaros, V.C. Hybrid Closure of Postinfarction Apical Ventricular Septal Defect Using Septal Occluder Device and Right Ventricular Free Wall: The Apical BASSINET Concept. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2023, 16, e013243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adilbekova, A.; Marassulov, S.; Baigenzhin, A.; Kozhakhmetov, S.; Nurkeyev, B.; Kerimkulov, A.; Murzabayeva, S.; Maiorov, R.; Kenzhebayeva, A. Hybrid versus traditional method closure of ventricular septal defects in children. JTCVS Tech 2024, 24, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantinotti, M.; Marchese, P.; Scalese, M.; Medino, P.; Jani, V.; Franchi, E.; Vitali, P.; Santoro, G.; Viacava, C.; Assanta, N.; Kutty, S.; Koestenberger, M.; Giordano, R. Left Ventricular Systolic Impairment after Pediatric Cardiac Surgery Assessed by STE Analysis. Healthcare (Basel) 2021, 9, 1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraji, E.; Bolin, E.H.; Bond, E.G.; Thomas Collins, R. 2nd.; Greiten L.; Daily J.A. Left Ventricular Dysfunction Following Repair of Ventricular Septal Defects in Infants. Pediatr Cardiol 2025, 46, 296–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamson, G.T.; Arunamata, A.; Tacy, T.A.; Silverman, N.H.; Ma, M.; Maskatia, S.A.; Punn, R. Postoperative Recovery of Left Ventricular Function following Repair of Large Ventricular Septal Defects in Infants. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2020, 33, 368–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safa, R.; Dean, A.; Sanil, Y.; Thomas, R.; Singh, G.; Charaf Eddine, A. Effect of Preoperative Volume Overload on Left Ventricular Function Recovery After Ventricular Septal Defect Repair. Am J Cardiol 2023, 203, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.A.; Al-Akhfash, A.; Bhat, Y.; Alqwaiee, A.; Abdulrashed, M.; Almarshud, S.S.; Almesned, A. Myocardial deformation in children post cardiac surgery, a cross-sectional prospective study. Egypt Heart J 2024, 76, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasheen, S.S.; Ahmed, M.K.; Elgayar, M.M. Assessment of Left Ventricular Systolic Function after Surgical and Transcatheter Device Closure of Ventricular Septal Defect Using Speckle Tracking Imaging. Menoufia Medical Journal 2023, 36, Article 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.J.; Jhang, W.K.; Park, J.J.; Yu, J.J.; Kim, Y.H.; Ko, J.K.; Park, I.S.; Seo, D.M. Left ventricular function after left ventriculotomy for surgical treatment of multiple muscular ventricular septal defects. Ann Thorac Surg 2011, 92, 1490–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Tao, K.; An, Q.; Luo, S.; Gan, C.; Lin, K. Perventricular device closure of residual muscular ventricular septal defects after repair of complex congenital heart defects in pediatric patients. Tex Heart Inst J 2013, 40, 534–40. [Google Scholar]

- Mattei, A.; Strumia, A.; Benedetto, M.; Nenna, A.; Schiavoni, L.; Barbato, R.; Mastroianni, C.; Giacinto, O.; Lusini, M.; Chello, M.; Carassiti, M. Perioperative Right Ventricular Dysfunction and Abnormalities of the Tricuspid Valve Apparatus in Patients Undergoing Cardiac Surgery. J Clin Med 2023, 12, 7152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Wang, Q.; Liu, Y.L.; Xu, Y.L.; Guo, Y. Surgical closure of apical multiple muscular septal defects via right ventriculotomy using a single patch with intermediate fixings. Chin Med J (Engl) 2013, 126, 2866–70. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Frandsen, E.L.; Schauer, J.S.; Morray, B.H.; Mauchley, D.C.; McMullan, D.M.; Friedland-Little, J.M.; Kemna, M.S. Applying the Hybrid Concept as a Bridge to Transplantation in Infants Without Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome. Pediatr Cardiol 2024, 45, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Lian, X.; Wen, P.; Liu, Y. Case report: Recovery of long-term delayed complete atrioventricular block after minimally invasive transthoracic closure of ventricular septal defect. Front Cardiovasc Med 2023, 10, 1226139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiberg, J.; Ringgaard, S.; Schmidt, M.R.; Redington, A.; Hjortdal, V.E. Structural and functional alterations of the right ventricle are common in adults operated for ventricular septal defect as toddlers. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2015, 16, 483–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karimi, M.; Hulsebus, E.; Murdison, K.; Wiles, H. A case of hybrid closure of a muscular ventricular septal defect: anatomical complexity and surgical management. Cardiol Young 2012, 22, 356–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bearl, D.W.; Fleming, G.A. Utilizing Hybrid Techniques to Maximize Clinical Outcomes in Congenital Heart Disease. Curr Cardiol Rep 2017, 19, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Zhang, F.; Fan, T.; Zhao, T.; Han, Y.; Hu, X.; Li, Q.; Shi, H.; Pan, X. Minimally-invasive-perventricular-device-occlusion versus surgical-closure for treating perimembranous-ventricular-septal-defect: 3-year outcomes of a multicenter randomized clinical trial. J Thorac Dis 2021, 13, 2106–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, L.Y.; Al-Alawi, K.; Breatnach, C.; Nolke, L.; Redmond, M.; McCrossan, B.; Oslizlok, P.; Walsh, K.P.; McGuinness, J.; Kenny, D. Hybrid Subxiphoid Perventricular Approach as an Alternative Access in Neonates and Small Children Undergoing Complex Congenital Heart Interventions. Pediatr Cardiol 2021, 42, 526–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]