Introduction

The outer body shape of humans is characterized by a high degree of bilateral symmetry. This is in sharp contrast to the anatomical situation of most inner organs, which normally display bilaterally asymmetric arrangements. Visceral asymmetry is a phylogenetically conserved feature among vertebrates. It evolves from an initially bilateral symmetric situation during the embryonic period of development. The emergence of visceral asymmetry is usually described as a three-step process [

1,

2]. It starts with the breaking of the initial state of bilateral symmetry at a signaling center - called the node -, which is located in the body midline of the early embryo. At the subsequent step, left-right (L-R) information is transferred, via molecular signaling cascades, from the midline signaling center to the left and right-sided organ forming areas (lateral plate mesoderm) where it induces the bilaterally asymmetric expression of body side-specific transcription factors, such as

PITX2, which defines left-sidedness. The paired organ forming areas thereby adopt a molecular left or right identity. At the third step, the molecular L-R identities of the organ forming areas are translated into bilaterally asymmetric morphology.

The conversion of an initially symmetric situation into a bilaterally asymmetric anatomy may not be important for the function of some organs such as the lungs. It is of utmost importance, however, for the normal function of the cardiovascular system of human beings and other lung-breathing vertebrates. This is because the asymmetric anatomy of the heart and great blood vessels dictates the correct alignments and separations of the systemic and pulmonary flow paths at the center of our cardiovascular system [

3]. It is therefore no wonder, that congenital malformation syndromes with a tendency for bilaterally symmetric patterning of the inner organs - so-called syndromes of

“visceral symmetry

“ or

“visceral isomerism“[

4,

5]. - frequently are associated with complex congenital heart defects such as TOF, DORV, TGA, congenitally corrected TGA, and TAPVC [

4,

5,

6,

7].

The congenital syndrome of visceral symmetry can display either a tendency for bilateral left-sidedness [

5] or a tendency for bilateral right-sidedness [

4], and, for a long time, the status of the spleen was used as the discriminator for the two subsets of the visceral isomerism syndrome. Asplenia was regarded as the pathognomonic sign for bilateral right-sidedness and polysplenia as the pathognomonic sign for bilateral left-sidedness [

6]. The two subsets of the syndrome, therefore, were frequently named

“asplenia syndrome“ and

“polysplenia syndrome“. However, careful examinations of affected patients have shown that the status of the spleen does not regularly correspond to the type of visceral isomerism displayed by affected thoracic organs, especially the type of morphologic symmetry displayed by affected hearts [

8]. With regard to the heart, it has been noted that the morphology of the atriums, specifically the morphology of the atrial appendages, is the best discriminator for the two subsets of the visceral isomerism syndrome [

8]. This finding has led to the currently preferred usage of the terms left and right “atrial isomerism “[

9] or, more exactly, left and right

“isomerism of the atrial appendages“[

10,

11], instead of the terms asplenia or polysplenia syndromes.

While the atrial heart segment of visceral isomerism patients can show a strong tendency for morphologic symmetry of its two chambers, a different situation is found at the level of the ventricular heart segment. In hearts with atrial isomerism, there is no evidence of morphologic isomerism of the ventricular segment [

12,

13,

14]. This means that, in the setting of atrial isomerism, the two ventricular chambers do not display the same morphology but display a different morphologic patterning of their apical trabeculated portions, which still facilitates identification of the morphologically right and left ventricle, respectively. Moreover, the two ventricular chambers never display a bilaterally symmetric positioning along the body midline but usually display a bilaterally asymmetric (handed) positioning along the L-R body axis, which can be either of so-called right-hand (normal ventricular situs) or left-hand topology (mirror-imaged ventricular situs). Therefore, in the setting of the visceral symmetry syndrome, ventricular topology is usually said to be randomized [

15,

16].

The above-described findings in hearts with atrial isomerism can be explained by the embryology of the heart [

17,

18]. The two atrial chambers arise from a common embryonic heart segment that is paired across the body midline. This means that the right-sided atrium is formed by material from the right-sided heart fields and the left-sided atrium is formed by material from the left-sided heart fields. The morphologic identity of the atriums, therefore, evolves in consequence of the molecular patterning of the embryonic heart-forming fields. In other words, morphologic isomerism of the atriums evolves on the basis of molecular isomerism of the embryonic heart forming fields. In contrast to the atrial chambers, the two ventricular heart chambers do not arise from a common embryonic heart segment that is paired across the body midline. Instead, they arise from a non-paired midline tube in which the embryonic primordiums of the so-called ‘left’ and ‘right’ ventricle initially are aligned along the cranio-caudal body axis. Thereby, the original position of the future left’ ventricle is cranial to the future atriums and caudal to the future ‘right’ ventricle [

19]. Therefore, each ventricular chamber primordium is a midline structure that is formed by materials from the left as well as right-sided heart fields. The morphological identities of the mature ventricular heart chambers are not determined by the molecular L-R patterning of the embryonic heart fields but by the patterning along the original cranio-caudal heart axis [

20].

In view of this fact, two questions arise: (1) how do the two ventricular heart chambers normally acquire their definitive topographical relationships; and (2) how is the topogenesis of the ventricular heart segment mechanistically linked to L-R patterning of the embryonic heart? The answer to both questions lies in the process of “ventricular looping”. Ventricular looping is a morphogenetic process that transforms the ventricular segment of the embryonic heart from an initially straight midline tube into a helically coiled tube and thereby brings the future ‘left’ and ‘right’ ventricles into an approximation of their definitive positional relationships [

19]. Ventricular looping principally can go rightward or leftward and thereby can produce two alternative configurations of the mature ventricular heart segment, called D-hand and L-hand topology. From these binary anatomical features only the D-hand topology is normally realized during embryonic development of vertebrates, so the spontaneous occurrence of ventricular L-hand topology is normally a very rare event [

21]. The very strong bias toward the development of ventricular D-hand topology can be regarded as a statistically “asymmetric distribution“ of a binary anatomical feature. It suggests that the direction of ventricular looping is determined by the molecular L-R patterning of the embryonic heart, and this idea seems to be in accord with the above-mentioned fact that ventricular L-hand topology is frequently found in hearts with atrial isomerism.

During the past three decades, research from developmental biologists and clinical geneticists has uncovered a great number of genes involved in visceral L-R patterning of the vertebrate body. Moreover, studies on animal models have shown that visceral asymmetry (visceral situs solitus or visceral situs inversus) evolves on the basis of bilaterally asymmetric expression patterns of body side-specific genes [

17], while visceral symmetry (visceral isomerism) evolves on the basis of bilaterally symmetric expression of left (left isomerism) or right-sided genes (right isomerism) [

1].

It is, however, a hitherto unsolved question as to how the molecular patterning of the embryonic heart controls asymmetric (chiral) looping of its ventricular segment. During the past 100 years, roughly two different types of mechanistic concepts have evolved on the basis of experimental data from developmental biology. The first attributes ventricular looping primary to chiral forces within the ventricular segment. This idea has become a popular hypothesis during the past decade [

22,

23], but its origin can be traced back up to the early 1920s. Experimental data suggest that, before union of the left and right-sided heart forming fields, each body-half has its own intrinsic tendency for helical coiling of the ventricular heart segment. The right-half was found to display an intrinsic tendency for leftward looping whereas the left-half displayed an intrinsic tendency for rightward looping [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29]. Experimental data furthermore suggest that the intrinsic tendency for helical coiling is stronger in the left than the right body-half [

30]. Based on these data, it has been postulated that, after union of the left and right heart forming fields, the looping behavior of the ventricular heart segment is normally dominated by intrinsic forces of its left half, so that ventricular looping normally produces ventricular D-hand topology, only [

28,

30]. If we assume that the intrinsic tendencies for helical coiling of the two halves of the embryonic ventricular heart segment are determined by the molecular patterning of the heart-forming fields, we then should expect that in cases of molecular left isomerism, ventricular looping should almost exclusively generate ventricular D-hand topology, whereas in cases of molecular right isomerism, ventricular looping should almost exclusively generate ventricular L-hand topology.

The second type of mechanistic concepts postulates that ventricular looping does not primarily result from the action of intrinsic forces but from the combined action of intrinsic and extrinsic forces. [

31,

32,

33]. In this scenario, intrinsic forces are responsible only for ventral bending of the ventricular tube along the mid-sagittal body plane. The bending ventricular tube is forced to adopt a helical configuration primarily due to external mechanical constraints provided by the wall of the pericardial cavity. Physical looping models indeed have shown that the complex helical shape of the ventricular heart loop can evolve on the basis of bilaterally symmetric starting conditions. However, in contrast to the normal situation in vertebrate embryos, which is characterized by the strong bias toward development of ventricular D-hand topology, ventricular looping simulations under bilaterally symmetric starting conditions lead to a statistically random (50:50) distribution of the two looping phenotypes [

34]. This suggests that the molecular L-R asymmetry of the heart-forming fields may not be responsible for the helical deformation of the ventricular segment of the embryonic heart tube but rather cause the normal bias toward the development of the D-hand topology phenotype.

To summarize, we can say that, in an individual patient with visceral isomerism syndrome, the tendency for bilateral symmetry of an affected heart is found only at the level of the atrial segment while the ventricular segment never displays a tendency for bilateral symmetry [

12,

13,

14]

. According to embryological concepts, however, we can expect that a tendency for bilateral symmetric development of the ventricular segment may become apparent in the form of statistical distribution patterns of D-hand and L-hand topologies found in large populations of patients with visceral isomerism syndrome. Depending on the mechanistic concept used to explain the embryology of the ventricular situs, we expect to find different patterns. According to the

“intrinsic looping only“ concept, ventricular topology is expected to display a pseudo-randomization since L-hand topology should tend to occur only in the subset of right atrial isomerism while D-hand topology should tend to occur only in the subset of left atrial isomerism. According to the intrinsic/extrinsic looping concept, however, there should be a tendency for true randomization (50:50) in both subsets of the visceral isomerism syndrome. Such a situation can be regarded as a statistically “symmetric distribution“ of a binary anatomical variable reflecting the syndrome specific tendency for bilateral symmetry.

The present study was conducted to determine the statistical distribution of ventricular D-hand and L-hand topology in a relatively large cohort of human patients with cardiac malformations in the setting of visceral isomerism syndrome. This was primarily done to check the validity of the two above-mentioned embryological concepts. Since it is possible that the type of ventricular topology may have an influence on the survival of isomerism patients, and thereby may mask the initial distribution pattern, we have additionally searched for ventricular topology-specific associations with cardiovascular disorders.

Methods

Patient Population

Our study is a retrospective cross-sectional study on a population of 192 patients in which congenital heart defects occurred in the setting of visceral isomerism syndromes (heterotaxy). It was a single centre study conducted in a specialized cardiovascular center (King Abdulaziz Cardiac Center [KACC]) located at King Abdulaziz Medical City in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

We looked systematically through imaging data from echocardiography and abdominal ultrasound, advanced imaging modalities such as cardiac and chest computed tomography (CT) and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) as well as data from ECG’s, 24 hr Holter monitoring for all cases of visceral isomerism that were diagnosed in KACC from January 2000 until March 2023.

The diagnosis of visceral isomerism syndromes was primarily based on echocardiographic imaging data, which were available for every patient. Thereby, our patients were assigned to the sub-groups of left visceral isomerism (LVI) or right visceral isomerism (RVI). We use the terms LVI and RVI instead of “left atrial isomerism “and “right atrial isomerism“ since ultrasonographic imaging does not facilitate accurate analysis of the morphology of the atrial appendages and the morphology and branching patterns of the lungs. RVI was diagnosed if the aorta and inferior caval vein (IVC) were on the same side of the spine, with the IVC slightly anterior (Huhta et al. 1982). LVI was diagnosed if the aorta was in the body midline and the blood from the subdiaphragmatic body half returned to the heart via an enlarged azygos vein, which was located in a posterolateral position [

35]. The accuracy of our primary diagnosis (LVI vs. RVI) was cross-checked by use of additional data from advanced imaging modalities (CT, MRI) if available. Thereby, a confirmatory diagnosis was based on the morphology of the lungs and airways or on the morphology of the atrial appendages as described previously [

36]. Bilateral presence of morphologically left or right lungs/atrial appendages was regarded as confirmatory for LVI or RVI, respectively.

- ▪

All patients with LVI or RVI seen at KACC from January 2000 until March 2023.

- ▪

Patients who did not have good quality echocardiograms due to poor imaging windows.

- ▪

Patients who were erroneously labeled as visceral isomerism patients but found out to be non-isomeric during detailed data review process.

- ▪

Demographic data for the patient including sex and date of birth (DOB)

- ▪

Mortality

- ▪

Duration of follow-up (calculated from date of first echo, date of birth until the date of death or date of last follow-up)

For any patient who had no documented follow-up after January 2021 until the end of our study (March 2023), we have contacted their families by phone using the documented contact information in the system to take additional information about patient’s current clinical condition and if he/she is still alive or not to determine mortality and survival period. Consent was taken from families by phone in accordance to our IRB committed guideline and a witness was present during the conducted phone calls. If we still were not able to contact the patients who had no follow-up documented in our system since January 2021, we considered them as missed follow-up patients.

The cases were then further evaluated for the following heart-specific variables:

- ▪

-

Main variables of cardio-vascular LR asymmetries:

- -

Ventricular topology; D-hand or L-hand

- -

Orientation of the cardiac apex; left-sided, right-sided, or midline

- -

Aortic arch patterning; unilateral left, unilateral right, or bilateral (double aortic arch

- -

Superior caval vein patterning; unilateral left, unilateral right, or bilateral

- -

Inferior caval vein patterning; normal or interrupted

- ▪

-

Associated congenital heart defects:

- -

Anomalies of pulmonary venous drainage; partial or total

- -

Atrioventricular septal defect; balanced or unbalanced

- -

Common atrium

- -

Univentricular heart including the morphological identity of its ventricle

- -

Hypoplastic left heart syndrome

- -

Transposition of the great arteries

- -

Double outlet right ventricle

- -

Anatomy of pulmonary valve; stenosis, atresia, or normal

- -

Aortic arch abnormalities; coarctation, interruption, or hypoplasia

- ▪

-

Associated congenital disorders of excitation and conduction:

- -

-

Generation of atrial activity (determined by the p-wave axis) divided into 4 groups:

Left inferior axis (0 to +90)

Left superior axis (0 to -90)

Right inferior axis (+90 to 180)

Right superior axis (-90 to 180)

- -

-

We further analyzed generation of atrial activity by combining the above 4 axis to another 4 groups

Left axis (combining left inferior axis and left superior axis)

Right axis (combining right inferior axis and right superior axis)

Inferior axis (combining left inferior axis and right inferior axis)

Superior axis (combining left superior axis and right superior axis)

- -

Presence of documented atrial arrhythmias (SVT, atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter, atrial tachycardia)

- -

-

Conduction abnormalities (complete heart block, junctional rhythm whether intermittent or permanent).

NOTE: Complete heart block was grouped into three categories:

-

- ▪

Complete heart block (congenital)

- ▪

Complete heart block (post-op)

- ▪

Complete heart block (acquired)

- -

Ventricular arrhythmias (ventricular fibrillation, ventricular tachycardia)

- -

Permanent pacemaker insertion

After the above listed variables were established, the principal investigator (T.O.) reviewed all the data from echos, cardiac MRIs, cardiac CT, ECG and 24-hr Holters and collected and filed all the data according to the listed variables. The data was reviewed one more time with a senior cardiologist (one of the co-investigators, A.M.A.A.) to confirm that all variables are correct. After collecting all data for and from the two groups, we analyzed our results in the master data file to determine the percentages of each variable from the total number of patients and the relevance between each variable.

Finally, we analyzed our data to search for:

- 1)

the proportions of ventricular D- and L-hand topology in the whole study population.

- 2)

the proportions of ventricular D- and L-hand topology in cases of (a) LVI, and (b) RVI.

- 3)

statistically significant differences in mortality between LVI and RVI patients.

- 4)

statistically significant associations between the type of ventricular topology (D-hand, L-hand) and mortality, (a) in the whole study population, and (b, c) in the two study sub-populations (LVI, RVI).

- 5)

statistically significant associations between the type of ventricular topology (D-hand, L-hand) and orientation of the cardiac apex, aortic arch patterning, and patterning of SVC and IVC; (a) in the whole study population, and (b, c) in the two study sub-populations (LVI, RVI).

- 6)

statistically significant associations between the type of ventricular topology (D-hand, L-hand) and specific congenital heart defects (AVSD, single ventricle, common atrium, TGA, DORV, PV defects, anomalies in pulmonary and systemic venous drainage); (a) in the whole study population, and (b, c) in the two study sub-populations (LVI, RVAI).

- 7)

statistically significant associations between the type of ventricular topology (D-hand, L-hand) and congenital disorders of excitation and conduction;(a) in the whole study population, and (b, c) in the two study sub-populations (LVI, RVI).

Study Design and Data Collection

This study was a retrospective cross-sectional study conducted at a single centre (KACC). All data supporting the findings of this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Data were collected according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria for patients with LVI and RVI, as described in detail above.

We used the following digital programs for data collection: IntelliSpace Cardiovascular 8 (Philips), representing our digital imaging database, MUSE Cardiology Information System NX 10.1.8.20532. (GE HealthCare), representing our ECG and Holter digital database, and BESTCare2.0A, representing our electronic medical record (EMR) system. The data were extracted by our clinical pediatric research technician in the cardiac canter and provided to us in an Excel spreadsheet.

The morphological phenotypes of the hearts were analyzed according to the sequential segmental approach (Loomba et al. 2016). For the diagnosis of the viscero-atrial situs we primarily used the standard echocardiographic view criteria (from abdominal transverse plane of the so-called sub-xiphoid (subcostal) views), including findings that are consistent with either LVI or RVI [

37]. Thereby, the following definitions were used: (1), usual arrangement (situs solitus) is when the aorta and inferior caval vein lie apart, on opposite sides of the spine, with the aorta on the left. (2), Mirror-imagery (situs inversus) is the mirror-imaged arrangement with the aorta on the right and the inferior caval vein on the left. (3), RVI is when the aorta and inferior caval vein are on the same side of the spine, with the vein slightly anterior. (4), LVI is when the aorta is in the midline and the azygos vein is located in a posterolateral position. The accuracy of diagnosis (LVI vs. RVI) was cross-checked by advanced imaging data as described above.

Ventricular topology was determined by one of the co-investigators (A.M.A.A.), who is an expert in advanced cardiac imaging, with detailed review of mainly echocardiography, and chest/cardiac computed tomography (CT) and MRI criteria data, if available.

Associated congenital disorders of excitation and conduction were evaluated by reviewing the ECGs of all patients, including 24-hr Holter monitor data, if available. Electrophysiology consultant colleagues (mentioned in the Acknowledgement section) were consultant for specific questions regarding type of p-wave axis and heart block patterns.

Mortality was defined as all confirmed deaths within the study population. This was determined by aggregating all documented deaths in our database and through follow-up phone calls. Patients were considered alive if they had a documented hospital visit within the two years prior to the end of the study period (January 2021 to March 2024). For patients without documented follow-up, phone contact was attempted with family members after obtaining appropriate consent in accordance with IRB guidelines. Their status (alive or deceased) was then confirmed. Patients without documented follow-up and whose families could not be reached due to incorrect or disconnected phone numbers were categorized as having missed follow-up. For data analysis, these patients were grouped together with confirmed deaths into a single category labeled “Dead or Missed.”

After having identified the relevant patient populations we generated a Data Master-file in Excel (Microsoft Office, Version 2010) for all isomeric patients and add to this file the defined variables mentioned below.

Once all the relevant patient populations and groups were identified, a Data Masterfile was created in Excel (Microsoft Office, Version 2010) with all the defined variables mentioned above to answer the set of questions that we had outlined for our study.

Statistical Analysis

Data was presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables. Data that did not fit a normal distribution was expressed as median and interquartile range (IQR). Categorical variables were presented as numbers and percentages. If required for advanced data analysis, other statistical tools, such as the chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test, were used to compare categorical data, and an independent sample t-test was used to compare continuous data. A difference between compared data was regarded as significant when the p-value was ≤0.05. Survival curves (Kaplan-Meyer curves) were created, and mortality was compared between groups. Analysis was done using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software for Windows (version 22, IBM Corp, Armonk, NY).

Ethical Considerations

This research was approved by the ethical research committee within the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the center’s medical research center with the IRB research protocol number RC19/204/R. Consent to call patient who missed follow up for over 2 years by phone was obtained and they were contacted about the current status of patient now (alive or not). There was no need for a consent form for the rest of the data since our data collection method consisted mainly of a chart review for the remaining variables. Patients’ confidentiality was maintained at all levels as only the PI and co-investigators had access to the data and were able to collect it. In addition, the data collected were kept in a secure place, using computerized methods in 3 specific password- protected computers, and by using coded serial numbers, we insured that the data did not contain any identification of the patients included in the research. None of the patient’s medical record numbers (MRN) were sent with the data for analysis as well.

Results

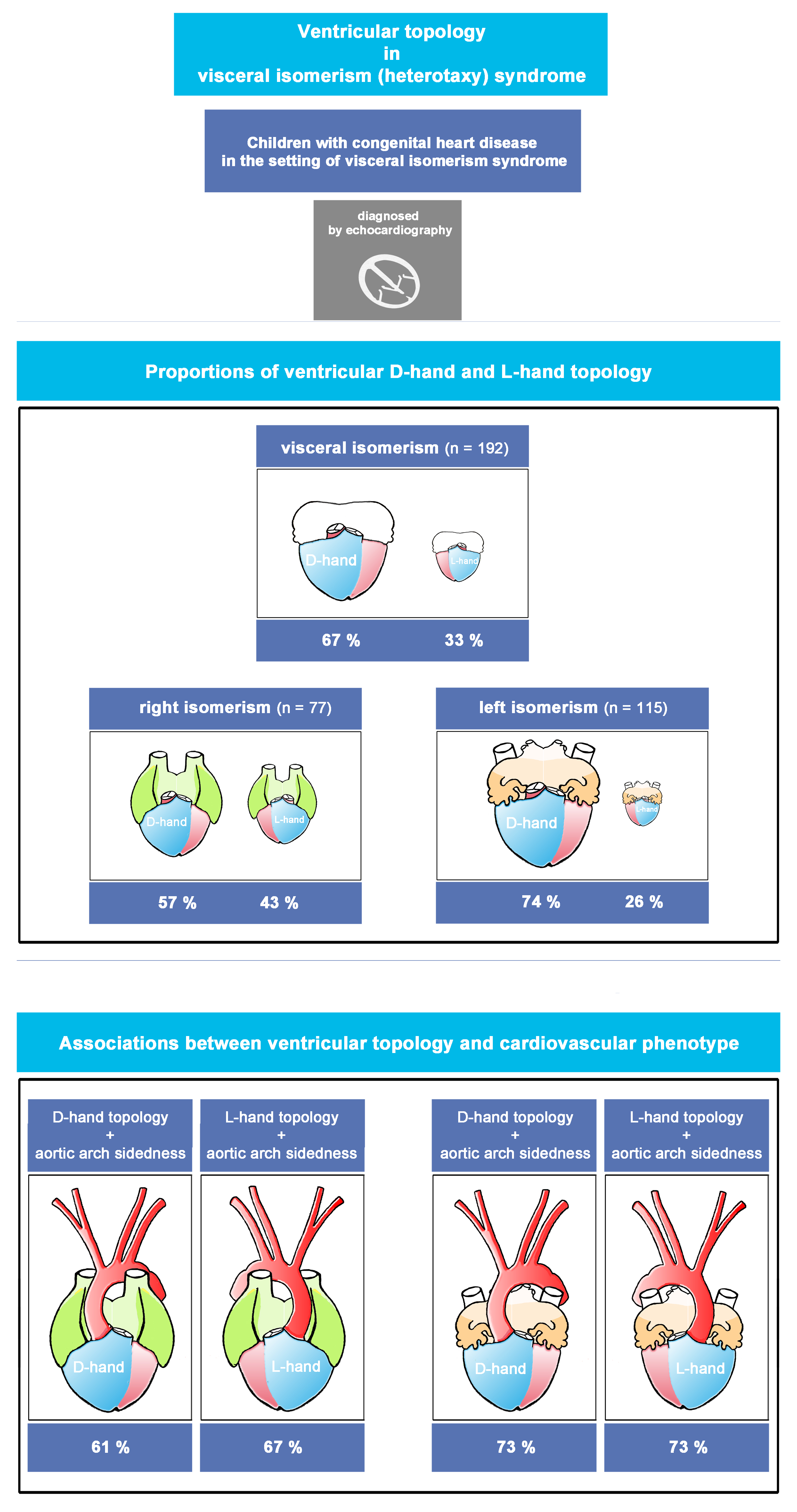

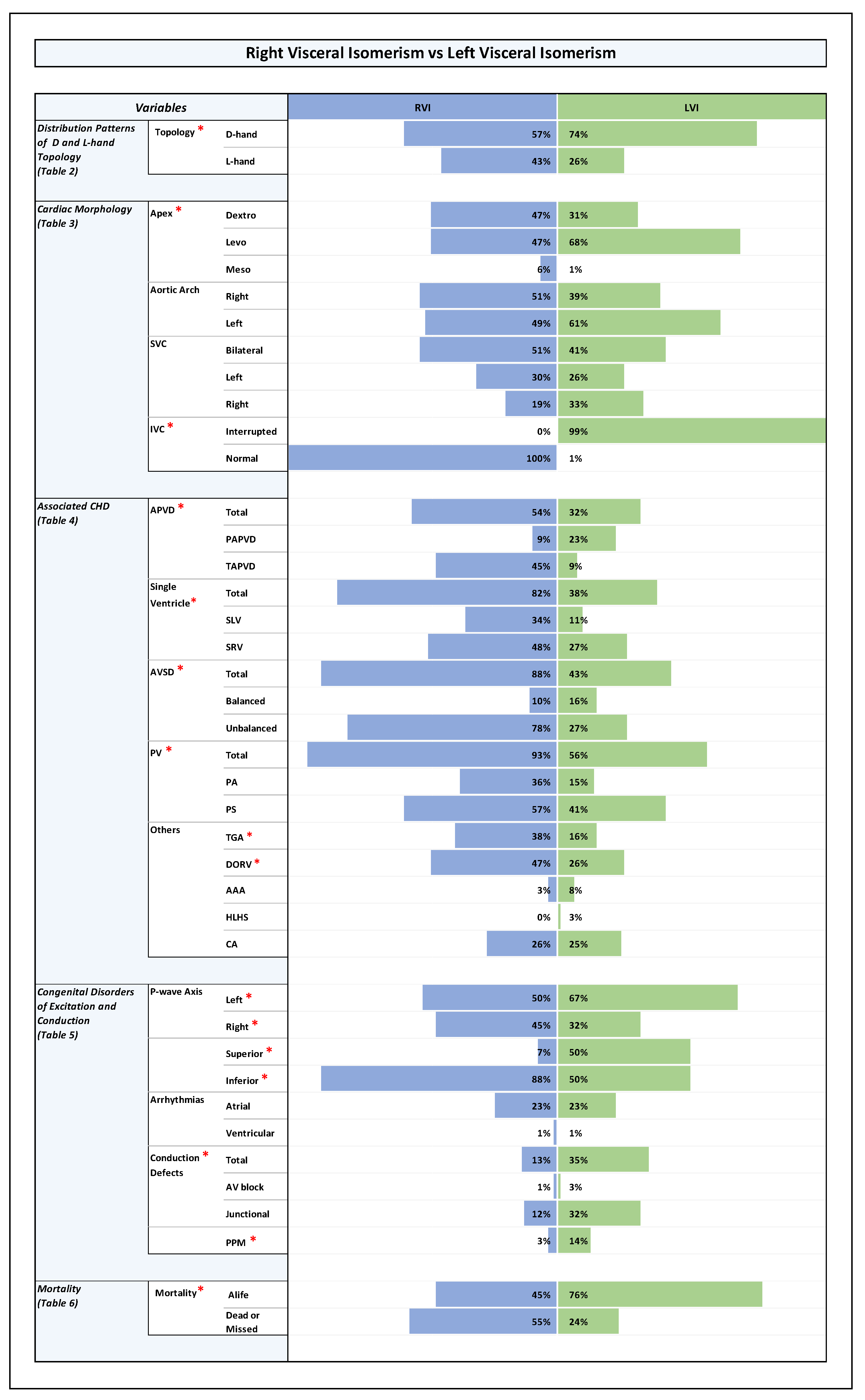

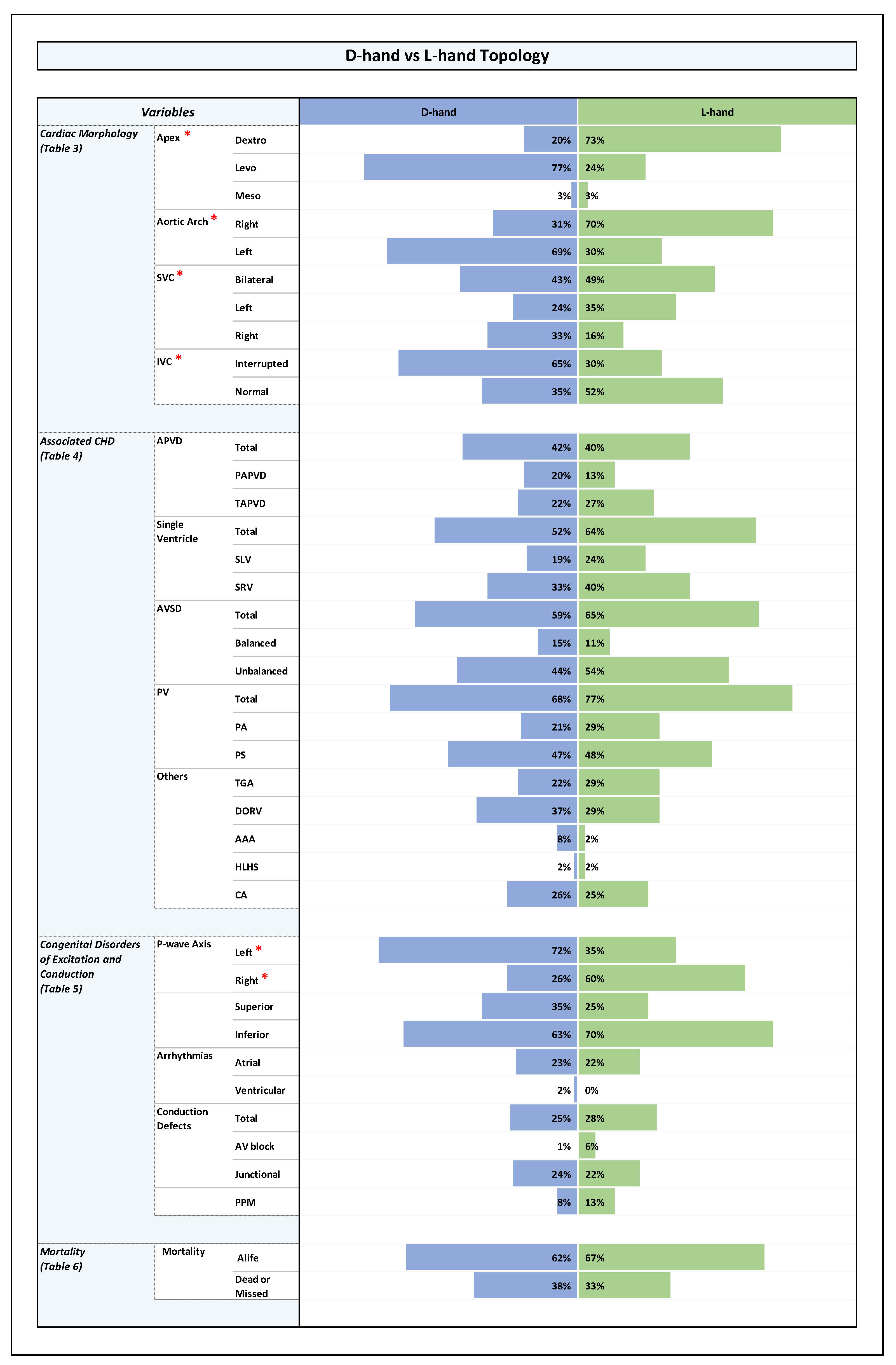

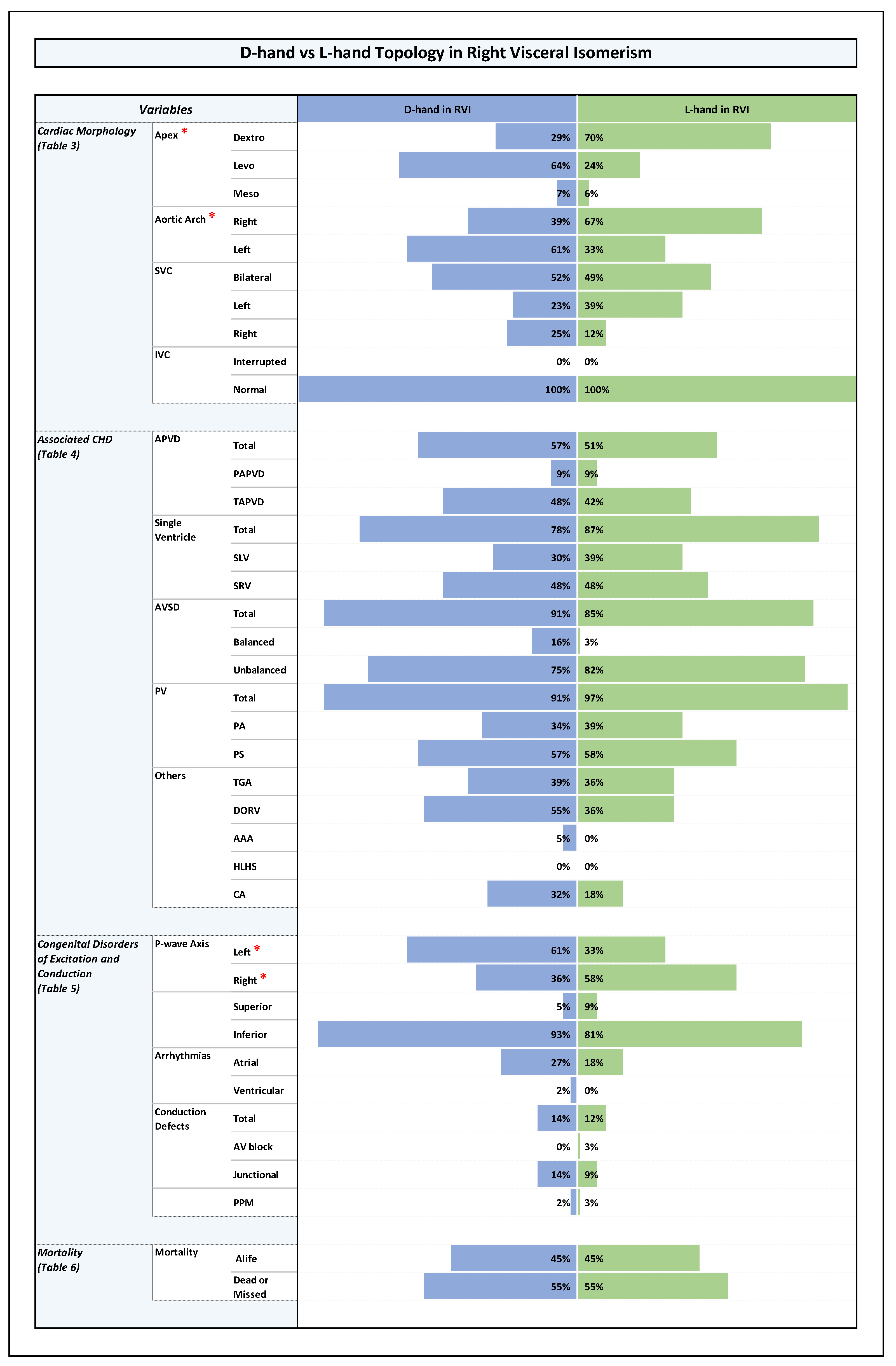

All results of our study have been shown in detail in Tables as Online Data Supplement (Table 1 through Table 7), shown at the end of this manuscript. The key findings in those results have been summarized here, as shown below, in form of visual plates (Plate 1 through Plate 4).

Plate 1.

Right Visceral Isomerism vs Left Visceral Isomerism. Note: Statistically significant P-value results were marked with a red star right next to the significant variable in the list of variables to the left side of the graph.

Plate 1.

Right Visceral Isomerism vs Left Visceral Isomerism. Note: Statistically significant P-value results were marked with a red star right next to the significant variable in the list of variables to the left side of the graph.

Plate 2.

D-Hand vs L-Hand Topology. Note: Statistically significant P-value results were marked with a red star right next to the significant variable in the list of variables to the left side of the graph.

Plate 2.

D-Hand vs L-Hand Topology. Note: Statistically significant P-value results were marked with a red star right next to the significant variable in the list of variables to the left side of the graph.

Plate 3.

D-hand vs L-hand Topology in Right Visceral Isomerism. Note: Statistically significant P-value results were marked with a red star right next to the significant variable in the list of variables to the left side of the graph.

Plate 3.

D-hand vs L-hand Topology in Right Visceral Isomerism. Note: Statistically significant P-value results were marked with a red star right next to the significant variable in the list of variables to the left side of the graph.

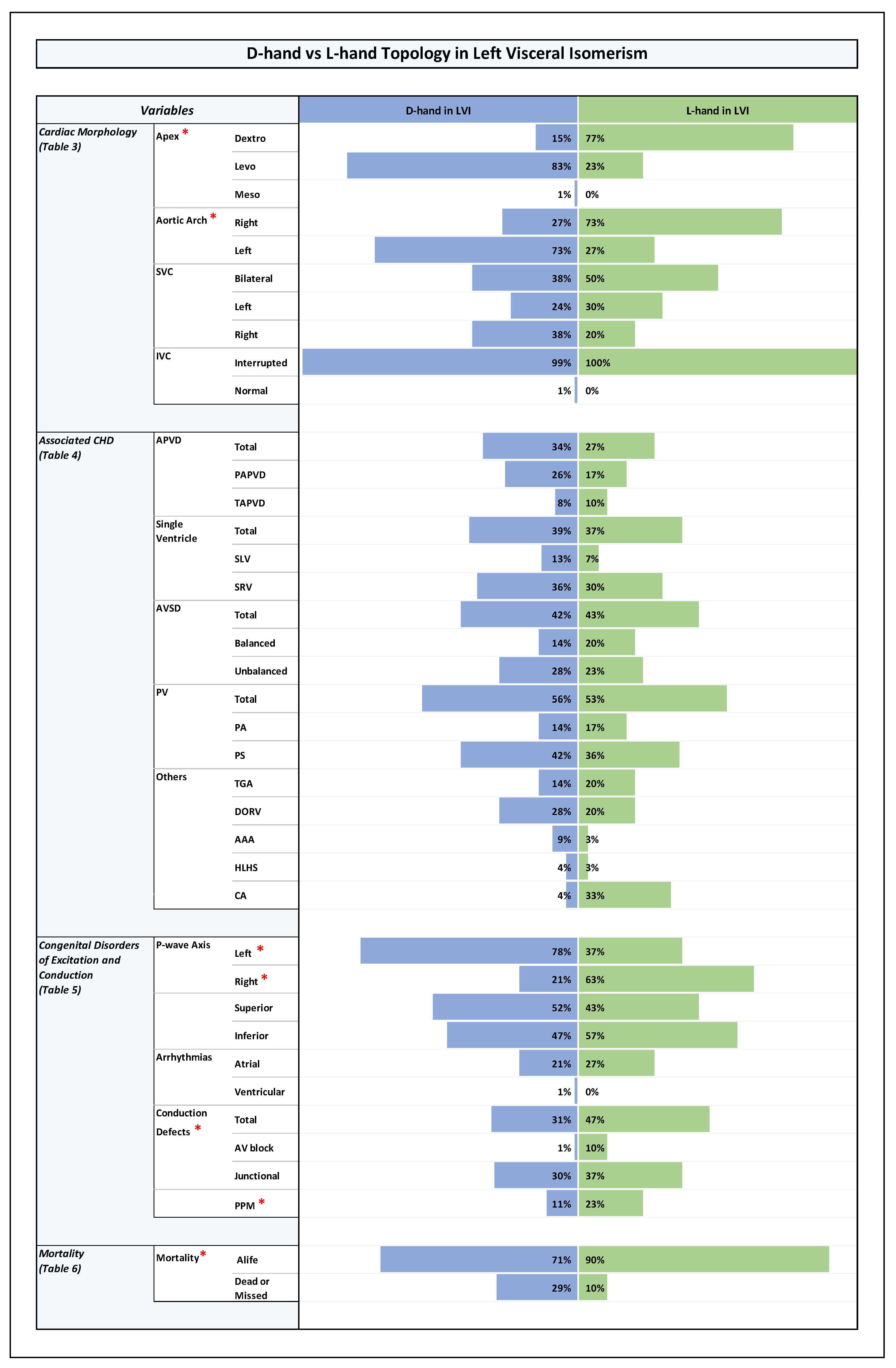

Plate 4.

D-hand vs L-hand Topology in Left Visceral Isomerism. Note: Statistically significant P-value results were marked with a red star right next to the significant variable in the list of variables to the left side of the graph.

Plate 4.

D-hand vs L-hand Topology in Left Visceral Isomerism. Note: Statistically significant P-value results were marked with a red star right next to the significant variable in the list of variables to the left side of the graph.

Sex Distribution

As shown in Table 1 in ODS there was an almost equal distribution of sexes within the whole study population (females (50.5%), males (49.5%)) as well as among the LVI and RVI sub-groups (RVI: females (44%), males (56%); LVI: females (55%), males (45%), p-value 0.149), and among patients with ventricular D-hand and L-hand topologies (D-hand: females (54%), males (46%); L-hand: females (43%), males (57%), p-value 0.138).

Size of Study Population and Sub-Populations (LVI, RVI), and Distribution of Ventricular Topologies

The whole study population comprised 192 patients. The median age at diagnosis was 1.1 months (Interquartile Range (IQR) 0.2- 6.7 months). From these patients, 115 were assigned to the LVI sub-group, while 77 were assigned to the RVI sub-group. With regard to the proportions of ventricular D-hand and L-hand topology, we found that, within the whole study population, there was a bias toward D-hand topology (D-hand (67%); L-hand (33%)). A statistically significant bias toward the presence of ventricular D-hand topology (74%) was also found among LVI patients, while the RVI sub-group showed an almost equal distribution of D-hand (57%) and L-hand topologies (43%), (p-value 0.015), as shown in Table 2 in ODS and Plate 1.

Orientation of the cardiac apex and patterning of aortic arch, SVC, and IVC (Plates 1-4 and Table 3 in ODS)

Among LVI patients, there was a statistically significant bias towards the normal arrangement (levo-position (68%), dextro-position (31%), midline position (1%)), while RVI patients had an almost equal distribution of left-sided (47%) and right-sided cardiac apex (47%) with only 6% having midline cardiac apex, (p-value 0.04).

When we analyzed the relation between ventricular topology and the orientation of the cardiac apex in the whole study population (n = 192), we found that patients with D-hand ventricles had a statistically significantly higher number of left-sided cardiac apex (77%), while the patients with L-hand ventricles had a higher number of right-sided cardiac apex (73%), (p-value 0.0001).

These differences were also consistent within the RVI sub-group: patients with D-hand ventricles had a significantly higher number of left-sided apex (64 %) while patients with L-hand ventricles had a higher number of right-sided apex (70%), (p-value 0.002). The same was true for the LVI sub-group: patients with D-hand ventricles had a significantly higher number of left-sided apex (83%), while patients with L-hand ventricles had a higher number of right-sided apex (77%), (p-value 0.0001).

These results indicate that patients with ventricular D-hand topology are more likely to have a left-sided cardiac apex while patients with ventricular L-hand topology are more prone to have a right-sided cardiac apex, regardless of whether they are found to have LVI or RVI.

Among all of our patients with visceral symmetry syndrome (n=192), we never found a bilaterally symmetric aortic arch patterning (double aortic arch) but always found a bilaterally asymmetric (unilateral) pattern with an almost random occurrence of left-sided (56.25%) and right-sided aortic arches (43.75 %).

The RVI sub-group (n = 77) had an almost equal number of patients with right (51%) and left-sided (49%) aortic arches, while the LVI sub-group (n = 115) had more patients with left-sided aortic arch (61 %). However, this difference between RVI and LVI sub-groups was statistically not significant (p-value 0.115).

When we analyzed the relation between ventricular topology and aortic arch sidedness in the whole study population, we found that patients with D-hand ventricles had a significantly higher number of left-sided aortic arch (69%), while patients with L-hand ventricles had a higher number of right-sided aortic arch (70%), (p-value 0.0001).

These differences were also consistent within the LVI and RVI sub-groups: in the RVI group, patients with D-hand ventricles had a higher number of left-sided aortic arch (61%) while patients with L-hand ventricles had a higher number of right-sided aortic arch (67%), the difference was statistically significant (p-value 0.015). In the LVI sub-group, patients with D-hand ventricles had also a higher number of left-sided aortic arch (73%) while patients with L-hand ventricles had a higher number of right-sided aortic arch (73%), (p-value 0.0001).

These results indicate that patients with ventricular D-hand topology are more likely to have a left-sided aortic arch, while patients with L-hand ventricles are more prone to have a right-sided aortic arch, regardless if they are found to have LVI or RVI.

Among all of our patients with visceral symmetry syndrome (n=192), a bilaterally symmetric SVC patterning was found in 45%, while a bilaterally asymmetric (unilateral) pattern was found in 55% with random occurrence of left-sided (27.5 %) and right-sided SVC (27.5 %).

Principally the same situation was found in the LVI as well as RVI sub-groups (RVI: bilateral (51%), left-sided (30%), and right-sided (19%); LVI: bilateral (41%), left-sided (26%), and right-sided (33%); p-value 0.12).

When we analyzed the relation between ventricular topology and SVC patterning in general, we found that, among the whole study group, there was no statistically significant association between the type of ventricular topology and the occurrence of a bilateral or a unilateral pattern (D-hand: bilateral (43%), unilateral (57%); L-hand: bilateral (49%), unilateral (51%)). The same holds true for the RVI and LVI sub-groups (D-hand in RVI: (52 %) bilateral, unilateral (48%); L-hand in RVI: bilateral (49%), unilateral (51%); p-value 0.18), (D-hand in LVI: bilateral (38%), unilateral (62%); L-hand in LVI: bilateral (50%), unilateral (50%); p-value 0.21).

However, when we analyzed the relation between ventricular topology and the position of a unilateral SVC, we found that there was a statistically significant association between the type of ventricular topology and the sidedness of the vein. Among patients with D-hand ventricles (n=129), there were more cases of a unilateral right SVC (33%) (unilateral left (24%)); and the L-hand group had more cases of a unilateral left SVC (35%), (unilateral right (16%)); (p-value 0.032).

Since the echocardiographic signs for the presence of an interrupted IVC were used for our primary diagnosis of LVI (see M&M), it was expected that, after cross-checking of the primary diagnosis by use of additional data from advanced imaging modalities, only a minority of patients with RVI might display an interrupted IVC, whereas almost all patients with LVI were expected to display interrupted IVC. We indeed found that all of our patients with RVI had normal IVC, whereas almost all patients with LVI (99%) had an interrupted IVC (p-value 0.0001). Among the whole study population, patients with a D-hand ventricle, had a higher incidence of interrupted IVC (65%) compared to cases with normal IVC (35%), whereas there was an almost equal distribution of interrupted (48%) and normal IVC (52%) among patients with a L-hand ventricle, (p-value 0.02). As all RVI patients were found to have normal IVC, no useful statistical analysis could be performed to compare patients with D- and L-hand ventricles within this group. In LVI patients, no statistically significant difference was noticed between patients with D- and L-hand ventricles as all patients with LVI, except for one, had interrupted IVC (p-value 0.35).

Associated Congenital Heart Disease

We compared the incidence of a specific group of associated congenital heart disease that are known to be of relevance in patients with LVI or RVI and checked for the presence of:

- -

Aortic arch abnormalities (coarctation, interruption, or hypoplasia)

- -

Anomalies in pulmonary venous drainage (partially anomalous, totally anomalous)

- -

Atrioventricular septal defect (balanced or unbalanced)

- -

Univentricular heart (single ventricle) and in case of its presence, whether the existing single ventricle is of left or right ventricular morphology

- -

Hypoplastic left heart syndrome

- -

Common atrium

- -

Transposition of the great arteries

- -

Double outlet right ventricle

- -

Anomalies of pulmonary valve (pulmonary stenosis, pulmonary atresia)

When we compared the presence of the above listed associated congenital heart disease between our 4 study groups (Plates 1-4 and Table 4 in ODS), we found the following:

Compared to LVI patients, patients with RVI had a significantly higher rate of:

- (a)

abnormal pulmonary venous drainage, mainly TAPVD (RVI: TAPVD (45%), PAPVD (9%); LVI: TAPVD (9%), PAPVD (23%); p-value 0.0001).

- (b)

AVSD, mainly unbalanced AVSD (RVI: unbalanced AVSD (78%), balanced AVSD (10%); LVI: unbalanced AVSD (27%), balanced AVSD (16%); p-value 0.0001).

- (c)

univentricular heart (single ventricle) pathologies (RVI: SLV (34%), SRV (48%); LVI: SLV (11%), SRV (27%); p-value 0.00001).

- (d)

pulmonary stenosis or atresia (RVI: 93%; LVI:56%; p-value 0.0001).

- (e)

TGA and DORV (RVI: TGA (38%), DORV (47%); LVI: TGA (16%), DORV (26%); p-value 0.001 and 0.003, respectively).

There were no statistically significant differences between LVI and RVI sub-groups in regard to the incidence of aortic arch abnormalities, hypoplastic left heart syndrome or common atrium. However, the total number of patients with aortic arch abnormalities (n=11) and hypoplastic left heart syndrome (n=4) was too small to make a good statistical analysis.

When we analyzed the relation between ventricular topology and congenital heart defects, we did not find significant associations between the type of ventricular topology (D-hand, L-hand) and any of the above-mentioned congenital heart defects. There were also no statistically significant associations between the type of ventricular topology (D-hand, L-hand) and any of these heart defects within the LVI and RVI sub-groups.

Congenital Disorders of Excitation and Conduction (Plates 1-4 and Table 5 in ODS)

With regard to inferior and superior p-wave axis, it was noted that among RVI patients there was a statistically significant higher rate of inferior p-wave axis (88%) compared to LVI patients (50%) (p-value 0.0001), reflecting higher prevalence of sinus node absence or dysfunction, and higher prevalence of ectopic atrial pacemakers in patients with LVI.

Combined with the data on ventricular topology, we did not find a statistically significant difference in the presence of inferior p-wave axis between RVI hearts with D-hand (93%) and L-hand (81%) ventricles (p-value 0.28). The same holds true for patients with LVI, where an inferior p-wave axis was found in 47% of D-hand ventricles and 57% of L-hand ventricles (p-value 0.58).

With regard to left and right p-wave axis, we noted that among RVI patients there was an almost equal distribution of left (50%) and right (45%) p-wave axis. However, in the LVI group, left p-wave axis was predominant (left (77%), right (33%), (p-value 0.02)), reflecting a higher prevalence of a left-sided cardiac apex in patients with LVI compared to patients with RVI.

RVI hearts with ventricular D-hand topology showed a statistically significant higher rate of left axis (61%) compared to right (36%), reflecting the higher tendency for a left-sided cardiac apex in this particular group (see above). RVI hearts with ventricular L-hand topology showed higher rates of right axis (58%), reflecting in turn the high rates of a right-sided cardiac apex in this setting.

LVI hearts with ventricular L-hand topology showed a statistically significantly higher rate of right axis (63%) compared to left axis (37%), while LVI with ventricular D-hand topology showed a higher prevalence of left axis (78%) compared to right (21%) (p-value 0.0001). The data correlates with high prevalence of a right-sided cardiac apex in L-hand group and a left-sided cardiac apex in the D-hand group.

There were no statistically significant differences in prevalence of atrial arrhythmias in all groups:

- (1)

RVI (23%) vs. LVI (23%), (p-value 0.17);

- (2)

ventricular D-hand topology (23%) vs. L –hand topology (22 %) (p-value 0.42);

- (3)

ventricular D-hand topology (27%) in RVI vs. L-hand topology in RVI (18%) (p-value 0.31);

- (4)

ventricular D-hand topology (21%) in LVI vs. L-hand topology in LVI (27%) (p-value 0.71).

When comparing rates of conduction defects whether congenital or acquired, the prevalence in RVI group was almost zero, apart from one patient who had an iatrogenic atrioventricular block requiring insertion of a pacemaker.

And when comparing the total conduction defects (AV block and junctional combined), there was only statistically significant differences when comparing RVI and LVI groups with LVI group having higher conduction defects (35%) compared to RVI group (13%), (P-value 0.003). The high percentage conduction defects in LVI group was mostly sinus node dysfunction (32%) followed by atrioventricular block (3%) while he percentage of sinus node dysfunction in RVI group was 12% and all of them had intermittent junctional rhythm only (p-value 0.003).

The looping pattern showed no much difference between D-hand and L-hand ventricles with near incidence of conduction defects (D-hand: 25%; and L-hand: 28%; p-value 0.21). The D-hand in RVI showed 6 patients with intermittent junctional rhythm compared to 3 patients in L-hand with RVI (p-value 0.33). The L-hand in LVI showed a higher percentage of congenital AV block (2 patients) with no similar incidence in D-hand with LVI. The numbers for junctional rhythm were comparable between the D-hand and L-hand ventricles for LVI (30% and 37%, respectively), with similar distribution for intermittent and permanent junctional rhythms (p-value 0.18).

With regard to mortality, our data showed a statistically significant difference between the RVI and LVI sub-groups (Plate 1 and Table 6 in ODS): in the RVI sub-group, more than half of the patients died or were missed (55 %), while in the LVI sub-group only a fourth of the patients died or were missed (24 %); (p-value 0.0001).

When we analyzed the relation between ventricular topology and mortality, the following findings were made:

Among the whole study population, there was no statistically significant difference in mortality between the patients with ventricular D-hand (38 %) and L-hand (33 %) topology; (p-value 0.53). (Plate 2 and Table 6 in ODS).

The same holds true for the RVI sub-group (D-hand (55 %), and L-hand (55 %); p-value 1). (Plate 3 and Table 6 in ODS).

Among the LVI sub-group, however, there was a significantly lower mortality in patients with ventricular L-hand topology (10 %) compared to the patients with D-hand topology (71 %), (p-value 0.03). (Plate 4 and Table 6 in ODS).

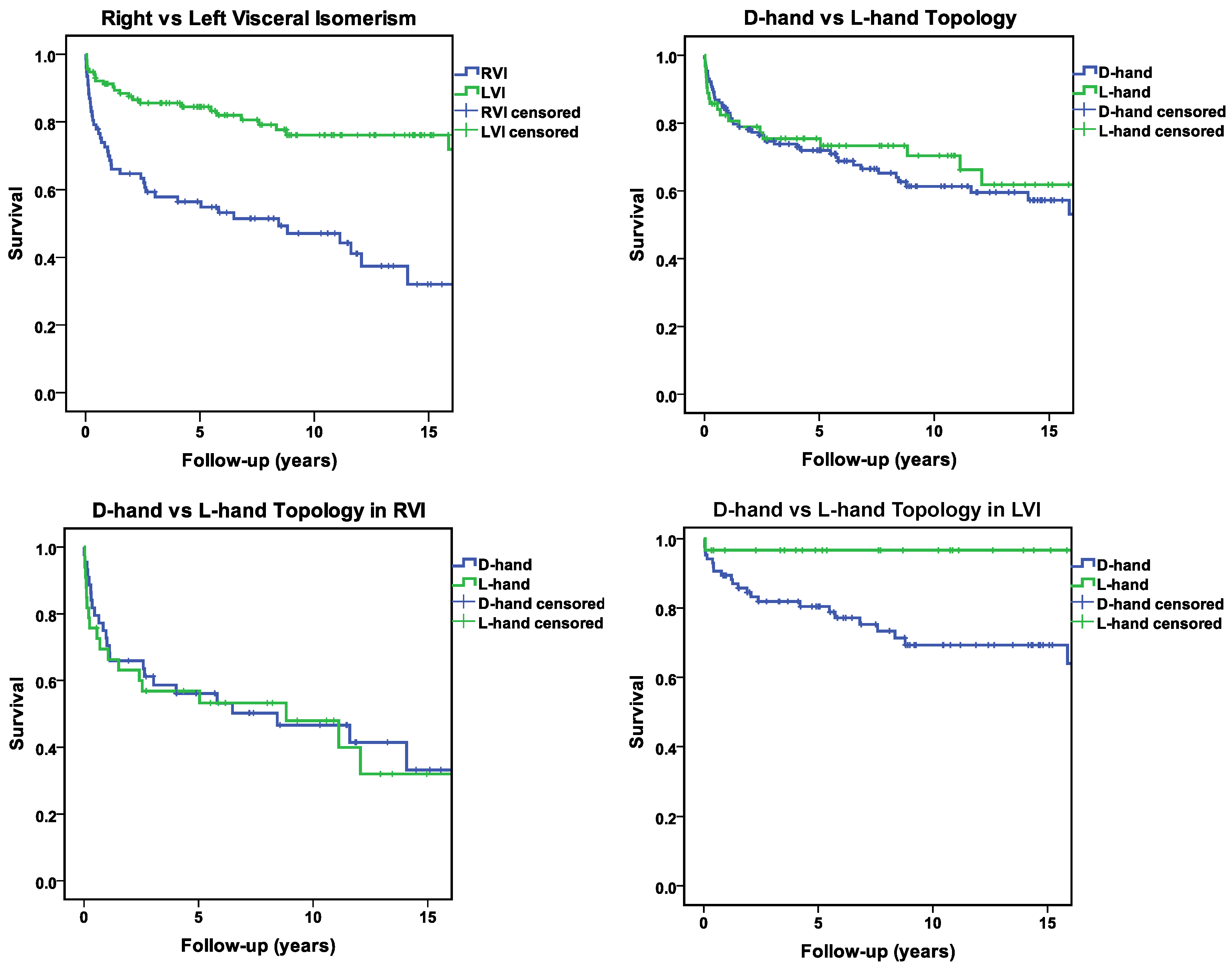

With regard to long-term survival (follow-up of at 5, 10 and 15 years) as shown in Figure 1 and Table 7 in ODS we found that RVI patients had a significantly worse outcome over the years (55%, 43%, and 32 %) at 5, 10, 15 years compared to LVI patients (84 %, 76% and 72 %) at the same period, (p-value 0.0001),

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves illustrating the differences in mortality among different groups over a 15-year follow-up period. Censoring events are marked with crosses on the respective curves.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves illustrating the differences in mortality among different groups over a 15-year follow-up period. Censoring events are marked with crosses on the respective curves.

When we analyzed the relation between ventricular topology and long-term survival, the following findings were made.

Among the whole study population, there was no statistically significant difference in long-term survival between the patient with ventricular D-hand (71 %, 60 %, and 53 %) and L-hand topology (73 %, 66%, and 46 %), (p-value 0.49).

The same holds true for the RVI sub-group (D-hand: 53%, 41 %, and 33 %; L-hand: 53 %, 40%, and 32 %; p-value 0.77).

In the LVI sub-group, however, there was a statistically significant difference in long term survival between the patients with D-hand and L-hand ventricles. Patients with ventricular L-hand topology showed a much better long-term survival (97 %, 97 % and 97 %) than patients with ventricular D-hand topology (79 %, 69 % and 64 %) (p-value 0.014).

Discussion

The main goals of the present study were (1) to document the statistical distribution patterns of ventricular D-hand and L-hand topology in a relatively large cohort of human patients with cardiac malformations in the setting of visceral isomerism syndrome, and (2) to check our patients data for the presence of significant associations between the type of ventricular topology and cardiovascular disorders as well as patient’s survival.

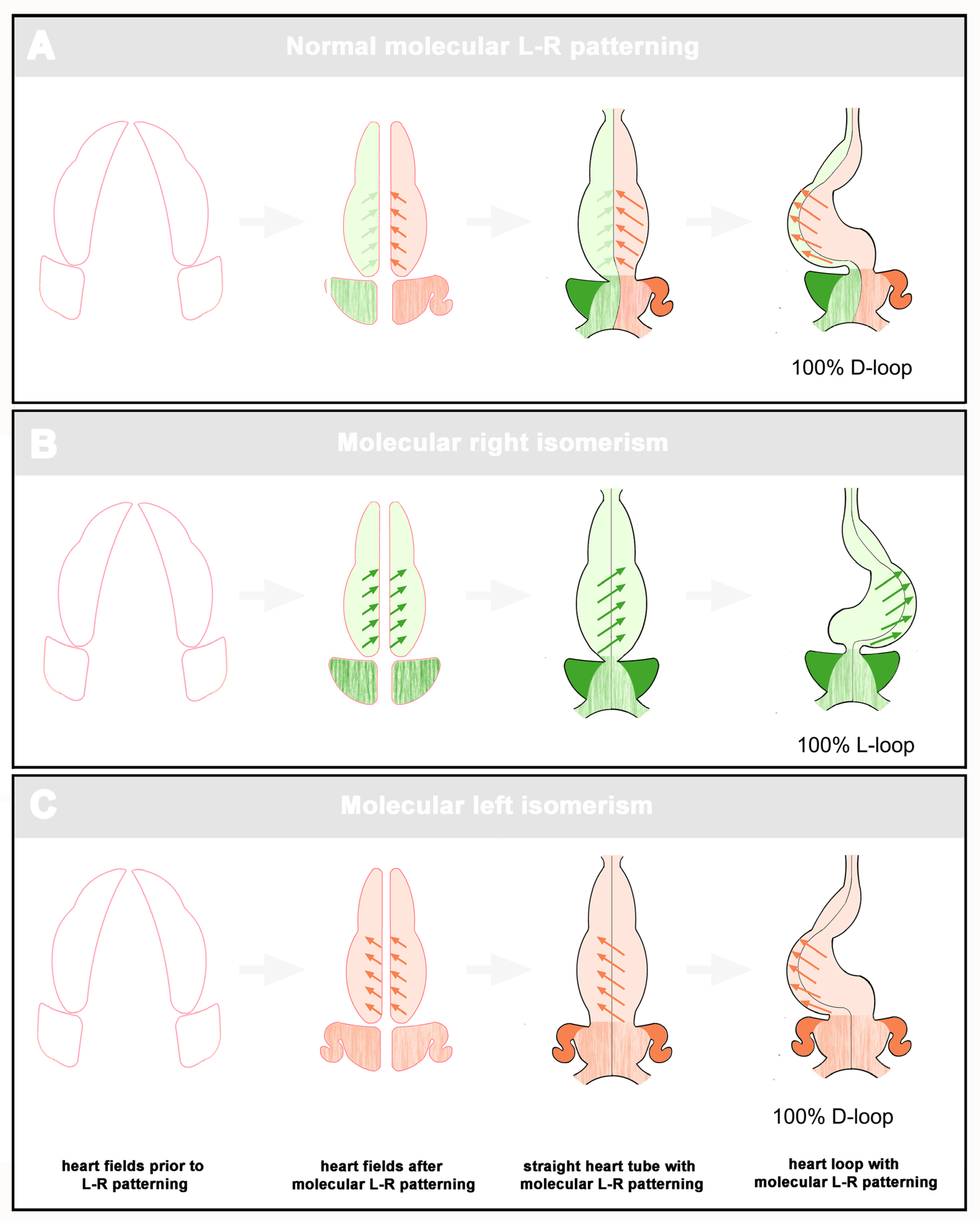

Statistical Distribution Patterns of Ventricular D-Hand and L-Hand Topology

With regard to the distribution pattern of ventricular topology, we found that, among the whole cohort of patients with visceral isomerism syndrome, there was a statistically asymmetric distribution pattern characterized by a bias toward D-hand topology (67% vs. 33%). When we segregated our data with regard to the two subsets of the syndrome, we found that D-hand as well as L-hand topology occurred in both subsets. There was, however, a striking difference between the RVI and LVI groups. While the LVI patients showed a statistically significant bias toward the presence of ventricular D-hand topology (74% vs. 26%), the RVI subset showed an almost equal distribution of D-hand and L-hand topologies (57% vs. 43%). These patterns do not fit to the currently popular idea that ventricular looping is mainly driven by chiral forces intrinsic to the ventricular segment of the embryonic heart. If we assume that the spin (chirality) of these forces is determined by the molecular L-R patterning of the embryonic heart, we should expect that the visceral isomerism syndrome displays a binary distribution pattern in which ventricular L-hand topology should tend to occur only in the RVI subset and D-hand topology should tend to occur only in the LVI subset (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

This scheme depicts the expected scenarios of ventricular looping if this process would be driven by intrinsic chiral forces whose spin (D-handed (red arrows), L-handed (green arrows)) is defined by molecular L-R patterning of the embryonic heart. A: Normal development. Ventricular looping is dominated by the D-handed forces within the left half of the heart tube. B: RVI. Molecular right isomerism induces L-handed forces in both halves of the heart tube. C: LVI. Molecular left isomerism induces D-handed forces in both halves of the heart tube.

Figure 2.

This scheme depicts the expected scenarios of ventricular looping if this process would be driven by intrinsic chiral forces whose spin (D-handed (red arrows), L-handed (green arrows)) is defined by molecular L-R patterning of the embryonic heart. A: Normal development. Ventricular looping is dominated by the D-handed forces within the left half of the heart tube. B: RVI. Molecular right isomerism induces L-handed forces in both halves of the heart tube. C: LVI. Molecular left isomerism induces D-handed forces in both halves of the heart tube.

On the other hand, however, our data also do not seem to fit completely to the alternative hypothesis, which says that the lateral twist of the bending embryonic heart tube mainly evolves in consequence of mechanical loads from the pericardial wall, which constrains ventral bending of the growing heart tube. According to this hypothesis, asymmetric expression of molecular determinants of L-R identities is not responsible for the chiral deformation of the ventricular heart segment but only for generating a bias toward development of one of the two alternative phenotypes (ventricular D-hand or L-hand topology). The bias inducing mechanism is attributed to morphological and/or functional asymmetries located at the venous and arterial poles of the linear heart tube [

31,

32,

33,

34]. In this scenario, both, the RVI as well as LVI subsets are expected to suffer from a lack of ventricular topology bias during the embryonic period of cardiogenesis and, therefore, should display a tendency for statistically symmetric distribution of ventricular D-hand and L-hand topologies; a pattern that may be regarded as reflection of the syndrome-specific tendency for visceral symmetry at the level of the ventricular heart segment. In our patients such a tendency for symmetry was present only in the RVI subset (57 % vs. 43 %) while the LVI subset displayed a statistically significant bias toward D-hand topology (74 % vs. 26 %). In view of the ambiguous situation two questions arise: (1), do our present data correspond to previously published data; and (2), how can we explain the observed deviation from a statistically symmetric distribution pattern?

Information on ventricular topology is provided only in a limited number of studies on patients with cardiac malformations in the setting of visceral isomerism syndrome.

Table 1 presents the distribution patterns of ventricular D-hand and L-hand topology found in these studies. At first sight, an analysis of these data does not seem to disclose a common pattern. Some studies present statistically almost symmetric distributions of ventricular D-hand and L-hand topologies among RVI as well as LVI patients [

13,

38,

39]. Others present distribution patterns similar to our data [

8], and the largest group of studies presents asymmetric distribution patterns that are found in RVI as well as LVI cases and are characterized by a moderate (~ 60:40) bias [

40,

41,

42,

43,

44]. Interestingly, this bias was toward the presence of D-hand topology in all but a single study [

45]. Pooling of the data from all studies shown in Tab. 1 discloses that the bias toward ventricular D-hand topology is stronger in the LVI subset (63.8 %) than in the RVI subset (55.4 %) of the visceral isomerism syndrome. This finding principally corresponds to our data although we observed a much stronger bias toward D-hand topology among our LVI patients (74% vs. 26%).

Table 1.

Ventricular topology in patients with cardiac malformations in the setting of visceral isomerism syndrome (data from previous studies).

Table 1.

Ventricular topology in patients with cardiac malformations in the setting of visceral isomerism syndrome (data from previous studies).

| |

RVI |

|

|

|

LVI |

|

|

|

| Study |

Case no. |

D-hand |

L-hand |

Undetermined |

Case no. |

D-hand |

L-hand |

Undetermined |

Stanger et al. [45]

|

23 * |

34.8 % (8) |

65.2 % (15) |

|

17 * |

70.6 % (12) |

29.4 % (5) |

|

| Carvalho et al. [38] |

13 |

54 % (7) |

46 % (6) |

|

12 |

50 %

(6) |

50 % (6) |

|

| Vairo et al. [39] |

|

|

|

|

28 |

53 % (15) |

47 % (13) |

|

| Francalanci et al. [40] |

33 * |

60.6 % (20) |

39.4 % (13) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Ho et al. [41] |

10 * |

60 % (6) |

40 % (4) |

|

20 * |

65 % (13) |

10 % (2) |

25 %

(5) |

| Uemura et al. [8] |

125 * |

54 % (68) |

42 % (52) |

4 %

(5) |

58 * |

79 % (46) |

16 % (9) |

5 %

(3) |

| Smith et al. [11] |

10 * |

20 % (2) |

20 % (2) |

60 % (6) |

25 * |

60 % (15) |

32 % (8) |

8 %

(2) |

| Yildirim et al. [66] |

43 |

53.5 % (23) |

18.6 % (8) |

27.9 % (12) |

88 |

59.1 % (52) |

22.7 % (20) |

18.2 % (16) |

| Loomba et al. [13] |

37 * |

50 % |

42 % |

8 % |

12 * |

47 % |

53 % |

|

| Tremblay et al. [42] |

131 * |

61 % (80) |

36 % (47) |

3 %

(4) |

56 * |

66 % (37) |

34 % (19) |

|

| Kiram et al. [43] |

184 |

57.6 % (106) |

41.9 % (77) |

0.5 %

(1) |

118 |

66.1 % (78) |

33.1 % (39) |

0.8 %

(1) |

| Oreto et al. [44] |

43 |

60.5 % (26) |

39.5 % (17) |

|

35 |

57 % (20) |

43 % (15) |

|

| Pooled data |

652 |

55.4 %

(361) |

39.9 %

(260) |

4.7 %

(31) |

469 |

63.8 %

(299) |

30.5 %

(143) |

5.7 %

(27) |

How can we explain the above-described deviations from statistically symmetric distribution patterns? At first, we should note that our data as well as the data from the majority of the above-mentioned studies come from postnatal patients. The distribution patterns of ventricular D-hand and L-hand topology among a cohort of postnatal patients with visceral isomerism do not only depend on the syndrome-specific allocation of ventricular topology at embryonic stages of development, but are additionally influenced by the natural history of affected patients during the fetal and perinatal periods of development. Previous data from postmortem hearts obtained from human patients with visceral isomerism syndrome (fetal and postnatal) have provided evidence for a strong association between the presence of ventricular L-hand topology and anomalies in the atrio-ventricular conduction axes among the RVI as well as LVI subset [

11]. Moreover, analyses of the outcome of prenatally diagnosed cases of visceral isomerism have shown that the intrauterine mortality of affected fetuses is high in the presence of hydrops caused by congenital atrio-ventricular block [

46,

47]. In view of these findings, and in view of the fact that congenital heart block preferentially affects LVI patients [

47], it is tempting to speculate that the above-described deviations from a statistically symmetric distribution of ventricular D-hand and L-hand topologies are caused by a higher rate of arrhythmia-related fetal death in isomerism patients with ventricular L-hand topology as compared to patients with ventricular D-hand topology, especially in the subset of LVI. Due to the high rate of terminations of pregnancy subsequent to a prenatal diagnosis of visceral isomerism [

47]. and due to technical difficulties in assessing ventricular topologies of fetal hearts in utero, it is unlikely that this hypothesis can be tested in the near future by documenting the natural history of prenatally diagnosed cases. Analysis of postnatal data for the presence of statistically significant associations between ventricular topology and the occurrence of life-threatening cardiovascular disorders (arrhythmias, malformations), as well as patient’s survival might be an alternative way to test the hypothesis. Our present data, however, did not uncover any statistically significant association between ventricular topology and the presence of life-threatening congenital arrhythmias or complex cardiovascular malformations. Moreover, we made the unexpected and somewhat puzzling finding that, among our LVI patients, the rate of long-term survival was higher in patients with ventricular L-hand topology compared to those with D-hand topology (

Figure 1). We have no sound explanation for this finding. Since previous studies had never looked for possible associations between ventricular topology and mortality/survival, future studies are needed to clarify the situation.

A second possible cause for the above-described deviations from statistically symmetric distribution patterns might be attributed to the composition of study populations. Data from animal models and human patients have shown that the clinical diagnosis

visceral isomerism syndrome or

heterotaxy characterizes a genetically very heterogeneous entity [

48]. Studies on animal models, furthermore, have shown that, with regard to ventricular topology, we principally can distinguish between two different types of genetic animal models for visceral isomerism; (1) those in which the presence of atrial isomerism is regularly associated with randomization of ventricular topology; and (2) those in which atrial isomerism is associated with ventricular D-hand topology, only. While the first type encompasses the vast majority of animal models for visceral isomerism (e.g [

49,

50,

51]), the second type encompasses only a relatively small group, which includes mutations/defects in lefty1 [

52], sonic hedgehog [

53,

54], and Pitx2 [

55]. At the present time, it is unknown why these mutants retain the normal bias toward development of ventricular D-hand topology. In view of this observation, however, we should be aware of the possibility that the statistical distribution pattern of ventricular D-hand and L-hand topology found among cohorts of human patients with visceral isomerism might depend on the proportion of patients carrying mutations in one of the three above-mentioned genes.

Cardiovascular Anomalies in the Setting of Visceral Isomerism, Their Distribution Among RVI and LVI Subsets, and Associations with Ventricular D-Hand and L-Hand Topology

It is well known that the visceral isomerism syndrome is usually associated with complex cardiac malformations and that the two subsets of the syndrome (RVI, LVI) differ from each other with regard to the pattern of associated cardiovascular disorders and with regard to clinical prognosis. [

7,

42]. The patterns found in the present study correspond to these well-known patterns (

Plate 1). When we looked for statistically significant associations between the type of ventricular topology and cardiovascular disorders, we found that, among the whole cohort as well as among the RVI and LVI subsets, there were no significant differences between the two variants of ventricular topology with regard to the prevalence of cardiovascular disorders that have strong influence on the prognosis of patients with visceral isomerism (

Plates 2-4). There were a few anatomical features of minor prognostic importance, however, that displayed a statistically significant association with either the ventricular D-hand or L-hand topology among the whole cohort as well as among the RVI and LVI subsets. These features are: (1) position of the cardiac apex; (2) direction of the p-wave axis; and (3) aortic arch sidedness (

Plates 2-4). In the following paragraphs, these three features will be discussed with regard to the embryology of the anatomical situs of the cardiovascular system.

Position of the cardiac apex. In contemporary as well as older articles on the embryology of visceral asymmetries, the normally left-sided position (levo-position) of the apex of the human heart is frequently described as a feature that reflects the looping morphogenesis of the embryonic heart. According to this view, we should expect that, in the setting of visceral isomerism syndrome, ventricular D-hand topology should be regularly associated with levo-position of the cardiac apex, while ventricular L-hand topology should display a regular association with dextro-position of the cardiac apex. Our present data indeed disclosed statistically significant associations between levo-position of the apex and ventricular D-hand topology (64-83%), and dextro-position and ventricular L-hand topology (70-77%). We should emphasize, however, that our data, which correspond to previous data (see

Figure 1 in Ticho et al [

15]), do not indicate a regular association. We therefore have to conclude that the direction of embryonic heart looping seems to play a strong but not exclusive role in positioning of the cardiac apex.

Direction of p-wave axis. With regard to this feature, we found that the presence of left p-wave axis was associated with D-hand topology (58-63%), while the presence of right p-wave axis was associated with L-hand topology (63-78%). It is well known that the direction of p-wave axis corresponds to the position of the cardiac apex [

56]. Our data therefore seem to reflect the positioning of the cardiac apex.

Aortic arch sidedness. The normal arrangement of the human aortic arch and its major arterial branches is characterized mainly by the presence of a single, left-sided aortic arch and represents a well-known example of visceral asymmetry near to the center of our cardiovascular system. It results from asymmetric remodeling of the originally bilateral symmetric system of paired pharyngeal arch arteries during the embryonic period of prenatal development [

57,

58,

59]. In view of this fact, it is tempting to speculate that, in the setting of visceral isomerism, the aortic arch system should display a tendency for bilateral symmetric arrangements, characterized by a high prevalence of double aortic arch. Surprisingly, however, such arrangements do not characterize the visceral isomerism syndrome of humans [

60]. as well as animal models [

61]. Instead, it is stated that the syndrome is characterized by randomization of aortic arch sidedness [

61]. The presence of a right aortic arch is a rare finding among humans without malformations. Its frequency is estimated at 0.1% in a normal population [

62]. Normal L-R patterning of the human aortic arch system thus is characterized by a strong bias toward the presence of a left aortic arch. This situation resembles the L-R patterning of the ventricular segment of the human heart where spontaneous reversal of topology is estimated at 0.01% [

21]. Our present data show that a right aortic arch is a very frequent finding among patients with visceral isomerism. This finding corresponds to previous data [

62,

63,

64]. With regard to statistical distribution patterns of left and right aortic arches, we found that the whole cohort of our isomerism patients as well as the two subsets of the syndrome, all displayed almost symmetric distribution patterns, that showed only small or moderate but statistically non significant bias toward the occurrence of a left aortic arch (whole cohort: 56.25% vs. 43.75%; RVI: 49% vs. 51%; LVI: 61% vs. 39%). This finding seems to confirm the above-mentioned statement that visceral isomerism is characterized by randomization of aortic arch sidedness [

61]. We should note, however, that our data do not correspond to all previously published data. As shown in

Table 2, there is a great variability among the data from previous studies, which may be explained in part by low case numbers. Pooling of these data discloses distribution patterns that are closer to randomization but show a small (RVI) to moderate (LVI) bias toward the presence of a left aortic arch.

Table 2.

Aortic arch sidedness among patients with cardiac malformations in the setting of visceral isomerism syndrome (data from previous studies).

Table 2.

Aortic arch sidedness among patients with cardiac malformations in the setting of visceral isomerism syndrome (data from previous studies).

| |

RVI |

|

|

|

|

LVI |

|

|

|

|

| Study |

Case no. |

Left

arch

|

Right arch |

Double arch |

Undet. |

Case no. |

Left arch |

Right

arch

|

Double arch |

Undet. |

| Ho et al. [41] |

10 * |

50 % (5) |

50 % (5) |

|

|

20 * |

75 % (15) |

25 % (5) |

|

|

| Francalanci et al. [40] |

33 * |

60.6 % (20) |

39.4 % (13) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Smith et al. [11] |

10 * |

90 % (9) |

10 % (1) |

|

|

25 * |

88 % (22) |

12 % (3) |

|

|

| Loomba et al. [13] |

37 * |

70 %

(26) |

30 %

(11) |

|

|

12 * |

95 %

(11) |

5 %

(1) |

|

|

| Tremblay et al. [42] |

131 * |

63 % (77) |

37 % (46) |

|

8 |

57 * |

75 % (41) |

25 % (15) |

|

1 |

| Kiram et al. [43] |

184 |

46.7 % (86) |

53.3 % (98) |

|

|

118 |

60 % (71) |

40 % (47) |

|

|

| Oreto et al. [44] |

43 |

70 % (30) |

30 % (13) |

|

|

35 |

51 % (18) |

49 % (17) |

|

|

| Pooled data |

448 |

56.5 %

(253) |

41.7 %

(187) |

|

1.8 %

(8) |

267 |

66.6 %

(178) |

33 %

(88) |

|

0.4 %

(1) |

It appears that, in the setting of visceral isomerism, the sidedness of the definitive aortic arch seems to represent a binary anatomical variable that can exist either in the form of a right-sided or left-sided aortic arch. A bilaterally symmetric third form (double aortic arch) virtually does not occur in the syndrome. Thus, the syndrome-specific tendency for bilaterally symmetric arrangement of inner organs usually does not appear in the aortic arch system of individual patients. The present data as well as previously published data, however, suggest that the syndrome-specific tendency for visceral symmetry becomes apparent at the population level where it appears as a tendency for statistically symmetric (randomized) distribution of right and left-sided aortic arches. This situation resembles the above-described situation found at the ventricular heart segment of patients with visceral isomerism. In view of the fact that, in the setting of visceral isomerism, ventricular topology and aortic arch sidedness have previously been described as randomized features, one might wonder that our study is the first to check patients’ data for the presence of statistically significant links between the two anatomical variables. Thus, our data are the first to show that, in the setting of visceral isomerism, there is a statistically significant association between ventricular D-hand topology and the presence of a left aortic arch (whole cohort: 69%; RVI: 61%; LVI: 73%), while ventricular L-hand topology is associated with right aortic arch (whole cohort: 70 %; RVI: 67%; LVI: 73%).

It is the question as to whether these associations might reflect ontogenetic relationships. In the setting of visceral isomerism, the emergence of a unilateral aortic arch can hardly be ascribed to molecular determinants of body sidedness since these determinants should be expressed in bilaterally symmetric fashions. It is therefore tempting to speculate that asymmetric remodeling of the embryonic pharyngeal arch arteries is mainly controlled by other factors such as hemodynamic load. Data from animal models for visceral isomerism and flow simulation studies, indeed, support the hypothesis that asymmetric remodeling of the pharyngeal arch arterial system is mainly driven by asymmetric routing of blood flow in consequence of chiral morphogenesis of the ventricular outflow tract (Yashihiro et al. 2007; Kowalski et al. 2012) [

61,

65]. We therefore think that the associations between ventricular topology and aortic arch sidedness, found in the present study, reflect the dependence of pharyngeal arch arterial remodeling on ventricular looping.

Limitations

Due to the rarity of visceral isomerism syndrome, our present study comprised only a limited number of patients (n = 192), even though we looked through data of around 22 years.

Our diagnosis of visceral isomerism syndrome principally was based on various imaging modalities. We should note however that, after the initial echocardiographic diagnosis, only 149 of our 192 patients had an additional abdominal US, and only 108 patients had an additional cardiac MRI or CT. Moreover, not all of the additional image data had a good quality that allowed detailed analysis of the atrial appendages and thoraco-abdominal situs. Therefore, our diagnosis of visceral isomerism was primarily based on echo criteria, as described in Methods.

With regard to survival and mortality data, we had a few patients (n=23) who had no documented follow-up and could not be reached by phone (wrong or disconnected phone number). We decided to assign these missed cases to the group of confirmed deaths: We assumed that the missed cases most likely deceased due to the complexity of their disease. However, we are aware of the fact that this might skew our data slightly.

With regard to rhythm abnormalities, we should note that some patients might have undocumented arrhythmias that were not seen in Holter or documented during their admission periods. Some patients also had very limited numbers of ECGs documented in the system either because they are still infants, or they died during infancy without having Holters or multiple ECGs done for them to see their rhythm problems in long term. Further, around 5 patients had no documented ECGs in the system, and some patients died in early infancy, which made any judgment regarding late presentations of heart blocks or junctional rhythm impossible. Thus, this also affected the evaluation of the number of patients who needed PPM insertion.