Submitted:

22 July 2025

Posted:

23 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Does a trade-off between seed size and number exist in a multispecies natural alpine steppe community?

- Are the trade-off patterns different in different functional groups?

- What is the role of limiting resources in determining seed size and number trade-offs?

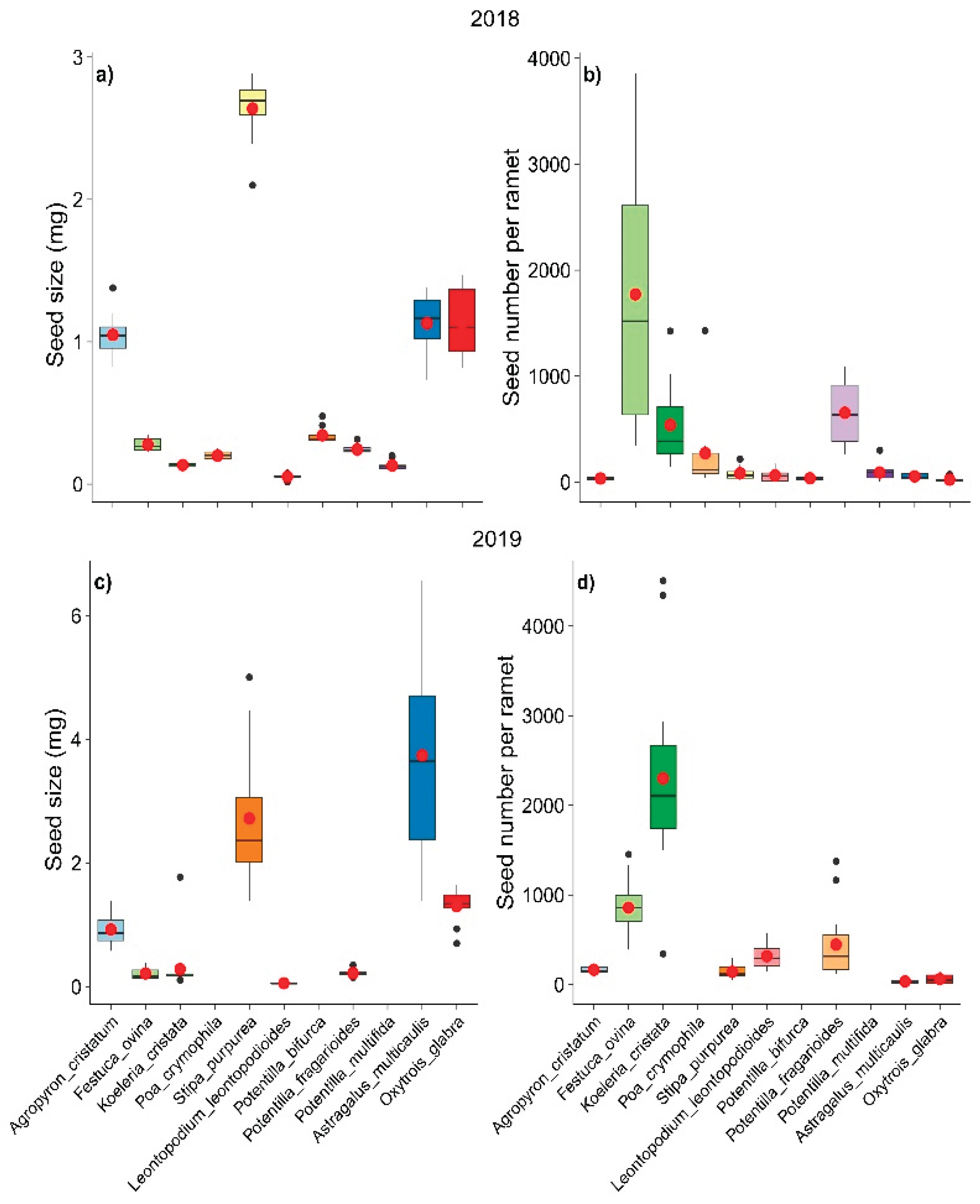

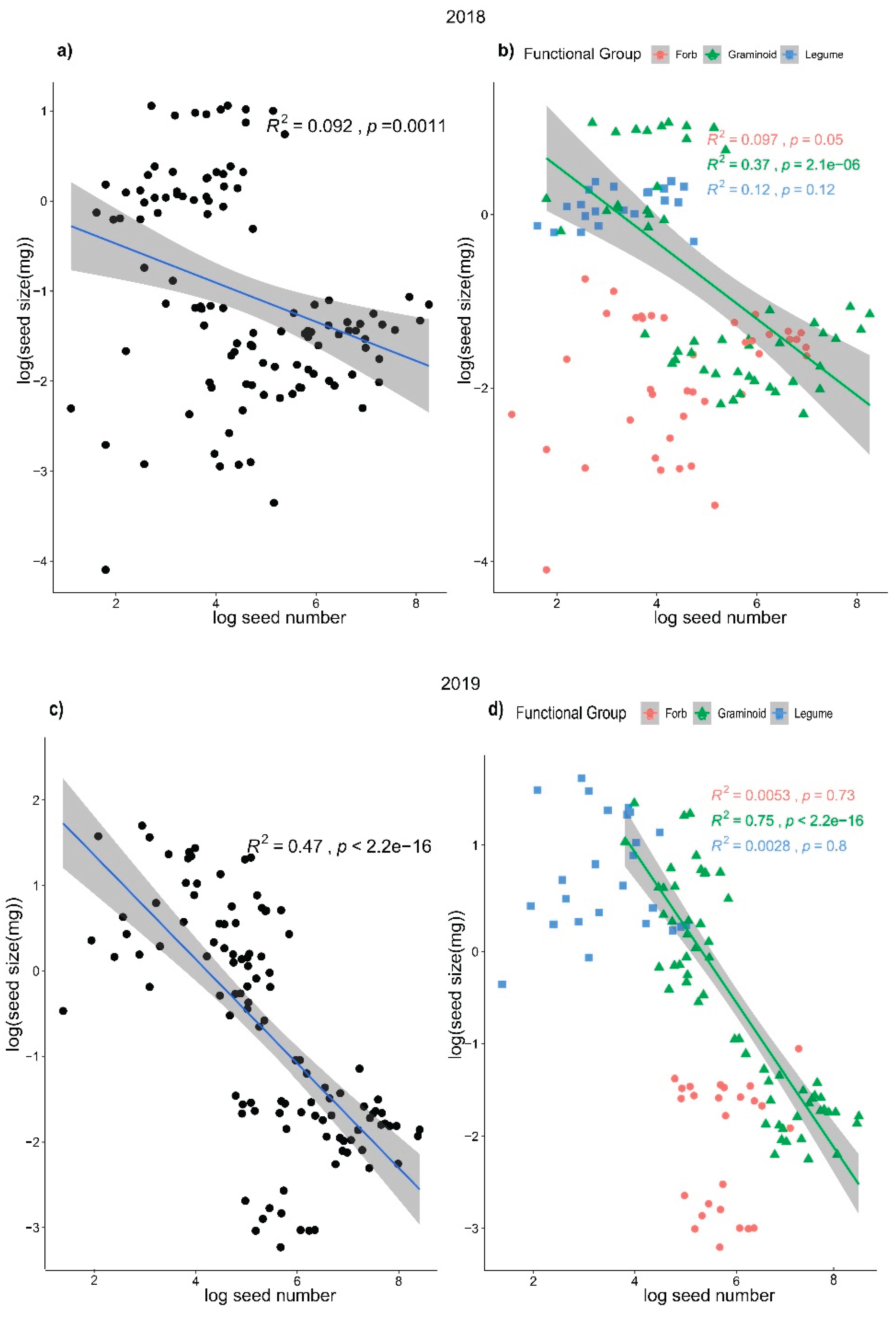

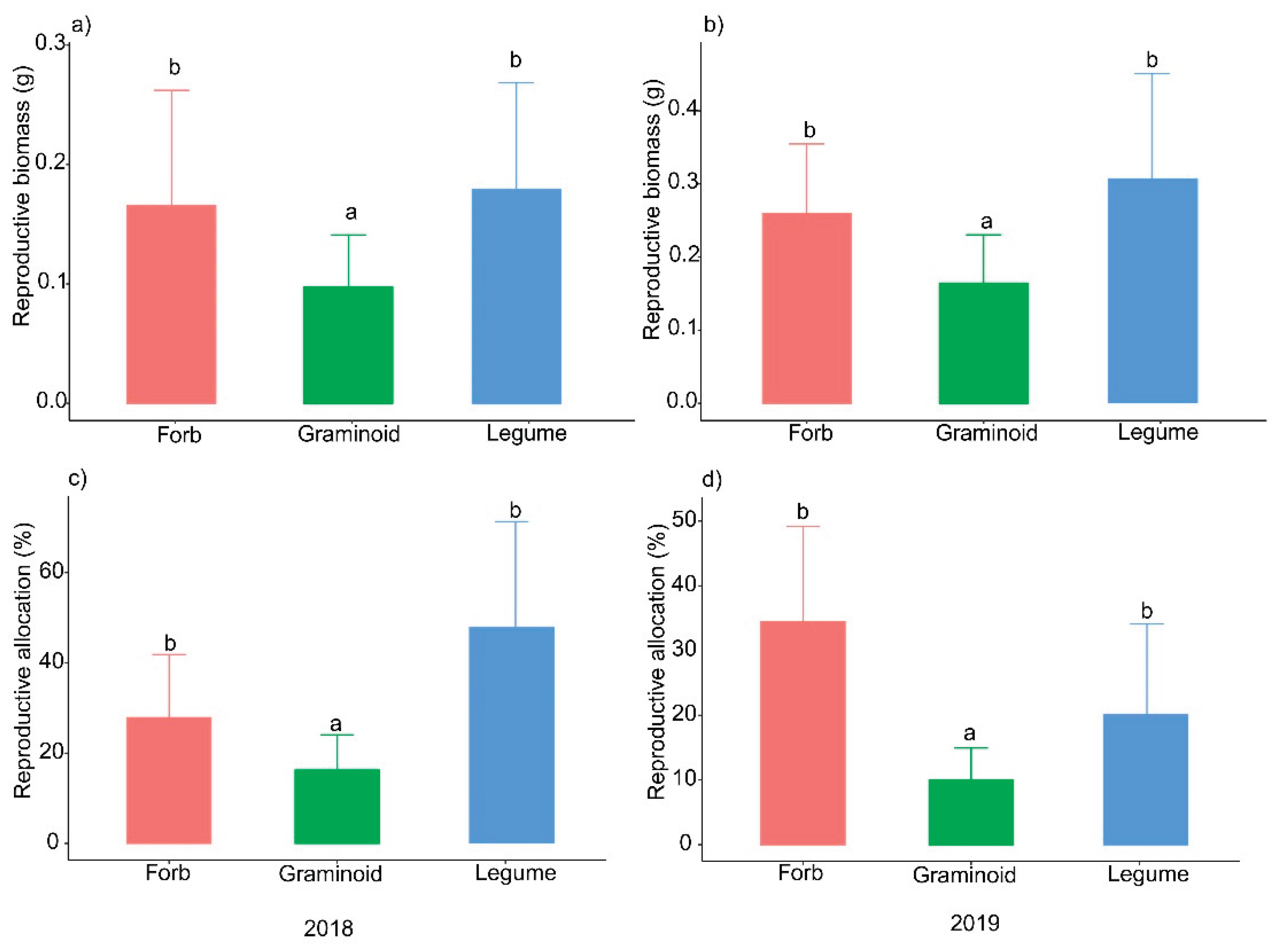

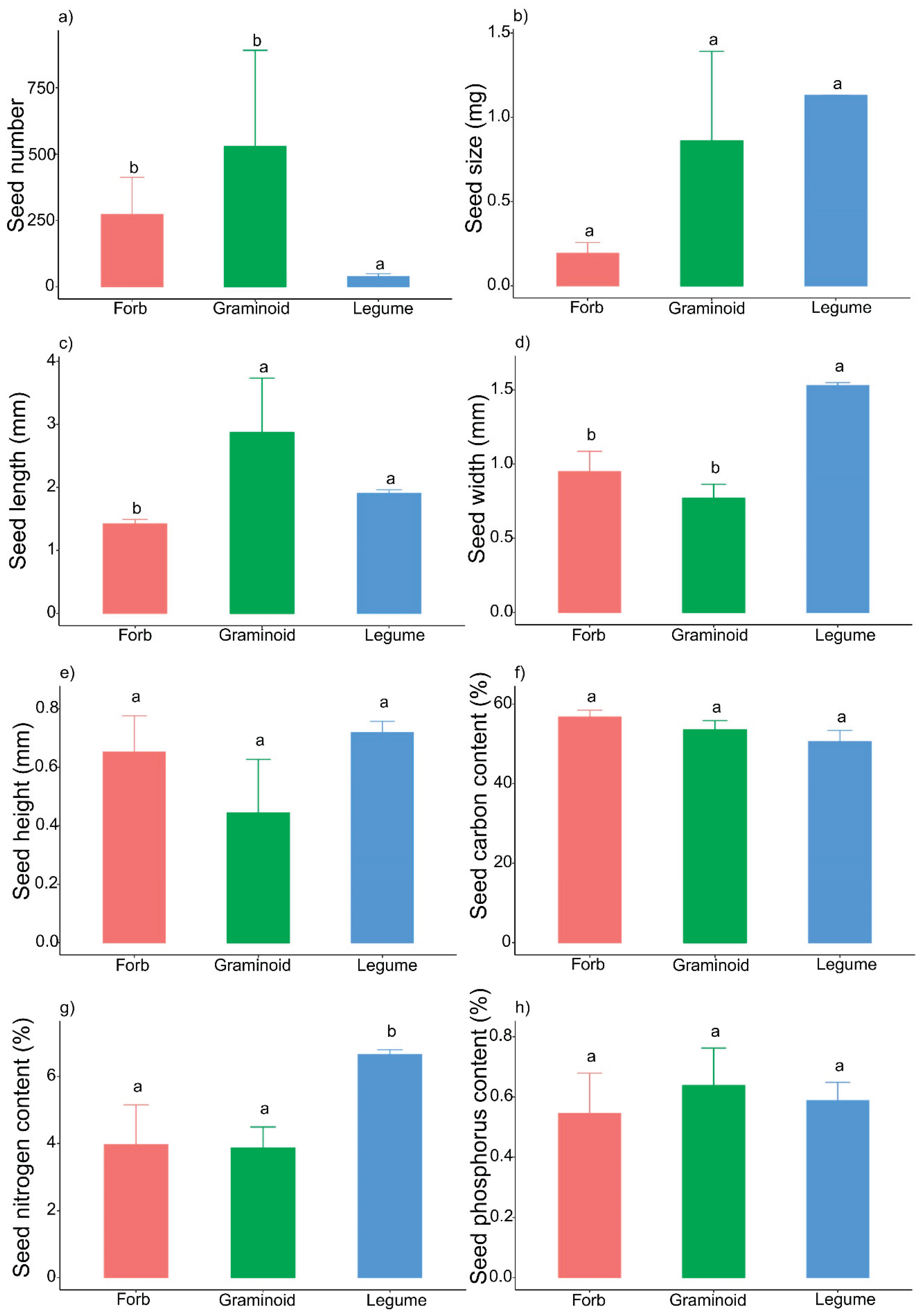

2. Results

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Site

4.2. Experimental Design and Seed Trait Measurements

4.3. Statistical Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PICs | phylogenetically independent contrasts |

| PCA | principal components analysis |

Appendix A

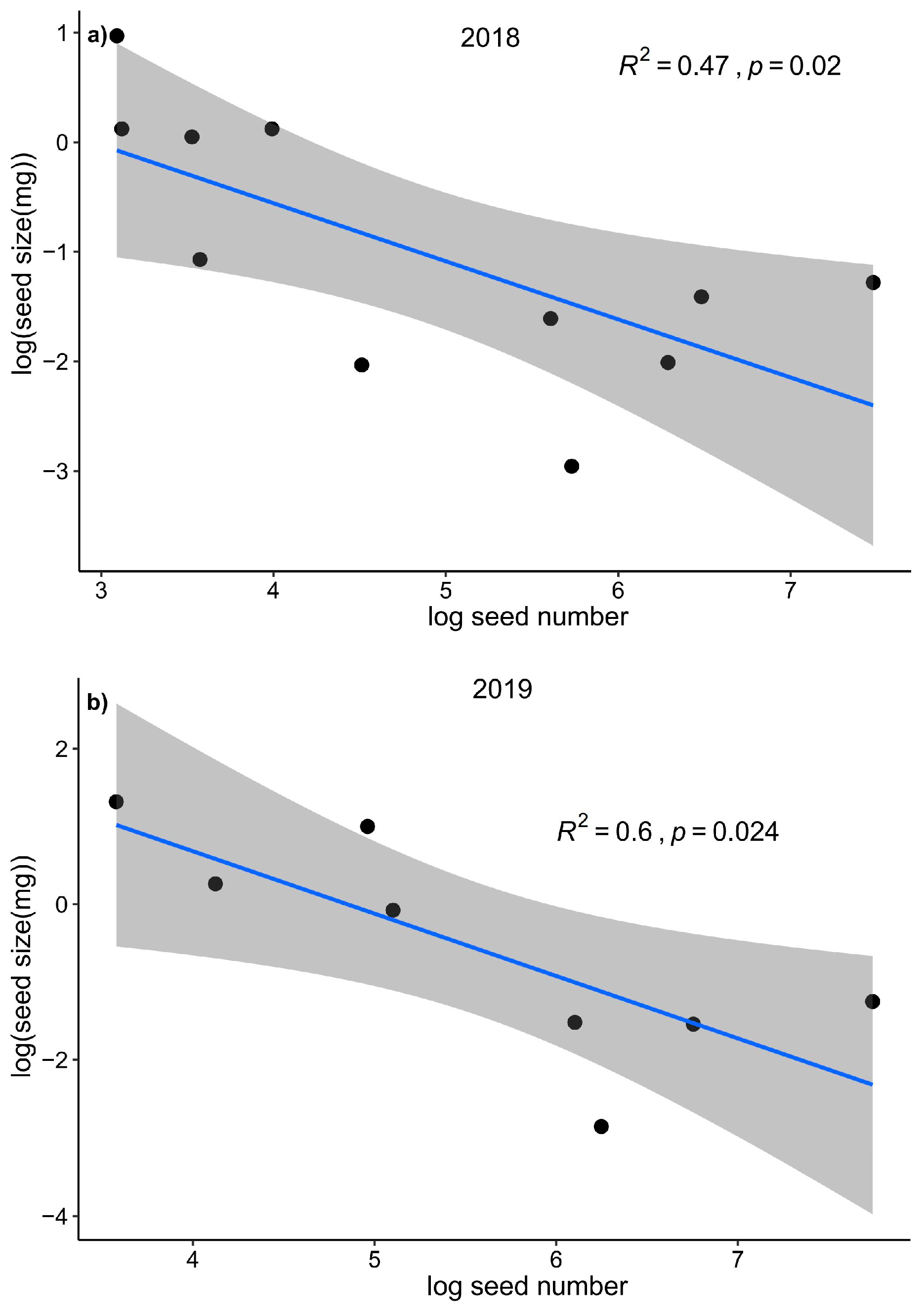

| year | linear regression | linear regression based on PICs | ||||

| slope | R2 | p | slope | R2 | p | |

| 2018 | -0.88 | 0.47 | 0.02 | -0.67 | 0.34 | 0.04 |

| 2019 | -0.74 | 0.60 | 0.02 | -0.64 | 0.45 | 0.06 |

| Species | seed number | seed size (mg) |

length (mm) |

width (mm) |

height (mm) |

C (%) |

N (%) |

P (%) |

| Oxytropis_glabra | 22.63 | 1.13 | 1.99 | 1.56 | 0.77 | 54.55 | 6.45 | 0.50 |

| Astragalus_alpinus | 54.1 | 1.13 | 1.829 | 1.49 | 0.66 | 46.53 | 6.86 | 0.67 |

| Stipa_purpurea | 22 | 2.64 | 5.459 | 1.08 | 1.02 | 54.87 | 2.78 | 0.42 |

| Poa_crymophila | 272.64 | 0.2 | 1.16 | 0.69 | 0.22 | 52.09 | 2.70 | 0.47 |

| Festuca_ovina | 1772 | 0.28 | 2.92 | 0.72 | 0.38 | 53.00 | 3.96 | 0.50 |

| Koeleria_cristata | 538.55 | 0.13 | 3.40 | 0.78 | 0.06 | 47.44 | 4.10 | 0.99 |

| Agropyron_cristatum | 34 | 1.05 | 1.41 | 0.59 | 0.54 | 60.19 | 5.79 | 0.81 |

| Potentilla_bifurca | 35.63 | 0.34 | 1.44 | 1.15 | 0.92 | 54.68 | 1.42 | 0.34 |

| Leontopodium_ leontopodioides |

308 | 0.05 | 1.31 | 0.56 | 0.33 | 61.88 | 6.60 | 0.93 |

| Potentilla_multifida | 91.09 | 0.13 | 1.61 | 1.14 | 0.76 | 54.74 | 2.57 | 0.39 |

| Potentilla_fragarioides | 653.9 | 0.24 | 1.32 | 0.94 | 0.60 | 55.74 | 5.26 | 0.52 |

| Species | Reproductive Biomass (g) |

Seed number |

Seed Size (mg) |

Functional Group |

| Oxytrois_glabra | 0.1307 | 23 | 1.382609 | Legum |

| Oxytrois_glabra | 0.3706 | 63 | 1.350794 | Legum |

| Oxytrois_glabra | 0.0564 | 12 | 0.816667 | Legum |

| Oxytrois_glabra | 0.1233 | 16 | 1.0375 | Legum |

| Oxytrois_glabra | 0.1128 | 13 | 0.984615 | Legum |

| Oxytrois_glabra | 0.0799 | 16 | 1.46875 | Legum |

| Oxytrois_glabra | 0.0718 | 9 | 1.1 | Legum |

| Oxytrois_glabra | 0.0425 | 12 | 1.125 | Legum |

| Oxytrois_glabra | 0.0565 | 5 | 0.88 | Legum |

| Oxytrois_glabra | 0.1422 | 7 | 0.814286 | Legum |

| Oxytrois_glabra | 0.7849 | 73 | 1.469863 | Legum |

| Astragalus_multicaulis | 0.0382 | 28 | 1.053571 | Legum |

| Astragalus_multicaulis | 0.0767 | 14 | 1.335714 | Legum |

| Astragalus_multicaulis | 0.5019 | 94 | 1.380851 | Legum |

| Astragalus_multicaulis | 0.1016 | 35 | 1.011429 | Legum |

| Astragalus_multicaulis | 0.215 | 45 | 1.286667 | Legum |

| Astragalus_multicaulis | 0.1508 | 46 | 1.295652 | Legum |

| Astragalus_multicaulis | 0.079 | 17 | 0.876471 | Legum |

| Astragalus_multicaulis | 0.1719 | 64 | 1.176563 | Legum |

| Astragalus_multicaulis | 0.235 | 114 | 0.734211 | Legum |

| Astragalus_multicaulis | 0.215 | 84 | 1.153571 | Legum |

| Potentilla_multifida | 0.0233 | 93 | 0.097849 | Forb |

| Potentilla_multifida | 0.0186 | 32 | 0.09375 | Forb |

| Potentilla_multifida | 0.0192 | 50 | 0.126 | Forb |

| Potentilla_multifida | 0.0465 | 112 | 0.129464 | Forb |

| Potentilla_multifida | 0.0124 | 9 | 0.188889 | Forb |

| Potentilla_multifida | 0.0329 | 142 | 0.116197 | Forb |

| Potentilla_multifida | 0.0213 | 48 | 0.133333 | Forb |

| Potentilla_multifida | 0.0748 | 300 | 0.125667 | Forb |

| Potentilla_multifida | 0.039 | 113 | 0.199115 | Forb |

| Potentilla_multifida | 0.0115 | 100 | 0.131 | Forb |

| Potentilla_multifida | 0.014 | 3 | 0.1 | Forb |

| Poa_crymophila | 0.0397 | 74 | 0.17973 | Graminoid |

| Poa_crymophila | 0.0754 | 115 | 0.231304 | Graminoid |

| Poa_crymophila | 0.2717 | 1428 | 0.173109 | Graminoid |

| Poa_crymophila | 0.0673 | 177 | 0.158757 | Graminoid |

| Poa_crymophila | 0.1137 | 346 | 0.154046 | Graminoid |

| Poa_crymophila | 0.0858 | 201 | 0.235323 | Graminoid |

| Poa_crymophila | 0.0349 | 83 | 0.206024 | Graminoid |

| Poa_crymophila | 0.0293 | 79 | 0.187342 | Graminoid |

| Poa_crymophila | 0.039 | 109 | 0.202752 | Graminoid |

| Poa_crymophila | 0.028 | 43 | 0.251163 | Graminoid |

| Poa_crymophila | 0.226 | 344 | 0.22064 | Graminoid |

| Festuca_ovina | 0.2495 | 3234 | 0.265121 | Graminoid |

| Festuca_ovina | 0.0572 | 522 | 0.332184 | Graminoid |

| Festuca_ovina | 0.0422 | 636 | 0.227358 | Graminoid |

| Festuca_ovina | 0.0928 | 1272 | 0.286321 | Graminoid |

| Festuca_ovina | 0.092 | 1956 | 0.238957 | Graminoid |

| Festuca_ovina | 0.2663 | 2610 | 0.345057 | Graminoid |

| Festuca_ovina | 0.3495 | 3858 | 0.316952 | Graminoid |

| Festuca_ovina | 0.0216 | 342 | 0.236842 | Graminoid |

| Festuca_ovina | 0.2798 | 1518 | 0.253755 | Graminoid |

| Potentilla_fragarioides | 0.4291 | 894 | 0.237136 | Forb |

| Potentilla_fragarioides | 0.4694 | 976 | 0.25584 | Forb |

| Potentilla_fragarioides | 0.2449 | 518 | 0.251544 | Forb |

| Potentilla_fragarioides | 0.2815 | 392 | 0.316327 | Forb |

| Potentilla_fragarioides | 0.1571 | 423 | 0.201182 | Forb |

| Potentilla_fragarioides | 0.1629 | 322 | 0.229503 | Forb |

| Potentilla_fragarioides | 0.219 | 258 | 0.288372 | Forb |

| Potentilla_fragarioides | 0.33 | 777 | 0.237066 | Forb |

| Potentilla_fragarioides | 0.1664 | 367 | 0.233515 | Forb |

| Potentilla_fragarioides | 0.4743 | 1089 | 0.196143 | Forb |

| Potentilla_fragarioides | 0.3533 | 755 | 0.260795 | Forb |

| Potentilla_fragarioides | 0.5403 | 1076 | 0.216357 | Forb |

| Koeleria_cristata | 0.0264 | 1024 | 0.100391 | Graminoid |

| Koeleria_cristata | 0.0829 | 1424 | 0.133708 | Graminoid |

| Koeleria_cristata | 0.0356 | 832 | 0.145673 | Graminoid |

| Koeleria_cristata | 0.0472 | 584 | 0.128767 | Graminoid |

| Koeleria_cristata | 0.0177 | 276 | 0.162319 | Graminoid |

| Koeleria_cristata | 0.0223 | 288 | 0.126389 | Graminoid |

| Koeleria_cristata | 0.0282 | 252 | 0.11746 | Graminoid |

| Koeleria_cristata | 0.0516 | 384 | 0.146875 | Graminoid |

| Koeleria_cristata | 0.0191 | 140 | 0.165714 | Graminoid |

| Koeleria_cristata | 0.0627 | 524 | 0.135878 | Graminoid |

| Koeleria_cristata | 0.0364 | 196 | 0.112245 | Graminoid |

| Stipa_purpurea | 0.1452 | 69 | 2.886957 | Graminoid |

| Stipa_purpurea | 0.0528 | 15 | 2.88 | Graminoid |

| Stipa_purpurea | 0.3012 | 171 | 2.722807 | Graminoid |

| Stipa_purpurea | 0.092 | 36 | 2.666667 | Graminoid |

| Stipa_purpurea | 0.1299 | 45 | 2.62 | Graminoid |

| Stipa_purpurea | 0.1225 | 60 | 2.765 | Graminoid |

| Stipa_purpurea | 0.0412 | 24 | 2.5875 | Graminoid |

| Stipa_purpurea | 0.2816 | 216 | 2.1 | Graminoid |

| Stipa_purpurea | 0.1076 | 99 | 2.390909 | Graminoid |

| Stipa_purpurea | 0.1947 | 99 | 2.769697 | Graminoid |

| Agropyron_cristatum | 0.0831 | 45 | 1.048889 | Graminoid |

| Agropyron_cristatum | 0.1029 | 55 | 1.378182 | Graminoid |

| Agropyron_cristatum | 0.0646 | 47 | 1.002128 | Graminoid |

| Agropyron_cristatum | 0.0348 | 25 | 1.112 | Graminoid |

| Agropyron_cristatum | 0.0243 | 8 | 0.825 | Graminoid |

| Agropyron_cristatum | 0.0586 | 46 | 0.865217 | Graminoid |

| Agropyron_cristatum | 0.0564 | 6 | 1.2 | Graminoid |

| Agropyron_cristatum | 0.0358 | 25 | 1.08 | Graminoid |

| Agropyron_cristatum | 0.0465 | 20 | 1.04 | Graminoid |

| Agropyron_cristatum | 0.0909 | 63 | 0.939683 | Graminoid |

| Leontopodium_leontopodioides | 0.2242 | 13 | 0.053846 | Forb |

| Leontopodium_leontopodioides | 0.0638 | 174 | 0.035057 | Forb |

| Leontopodium_leontopodioides | 0.8468 | 71 | 0.076056 | Forb |

| Leontopodium_leontopodioides | 0.0672 | 6 | 0.066667 | Forb |

| Leontopodium_leontopodioides | 0.4459 | 59 | 0.052542 | Forb |

| Leontopodium_leontopodioides | 0.1065 | 86 | 0.053488 | Forb |

| Leontopodium_leontopodioides | 0.3173 | 53 | 0.060377 | Forb |

| Leontopodium_leontopodioides | 0.1509 | 109 | 0.055046 | Forb |

| Leontopodium_leontopodioides | 0.0871 | 6 | 0.016667 | Forb |

| Potentilla_bifurca | 0.0341 | 63 | 0.304762 | Forb |

| Potentilla_bifurca | 0.027 | 49 | 0.312245 | Forb |

| Potentilla_bifurca | 0.0129 | 13 | 0.476923 | Forb |

| Potentilla_bifurca | 0.0192 | 41 | 0.302439 | Forb |

| Potentilla_bifurca | 0.0197 | 40 | 0.31 | Forb |

| Potentilla_bifurca | 0.0215 | 20 | 0.32 | Forb |

| Potentilla_bifurca | 0.0168 | 23 | 0.413043 | Forb |

| Potentilla_bifurca | 0.0178 | 36 | 0.305556 | Forb |

Appendix B

References

- Bostock SJ, Benton RA. The reproductive strategies of five perennial compositae. J Ecol. 1979, 67:91-107. [CrossRef]

- Chen R et al. Potential role of kin selection in the transition from vegetative to reproductive allocation in plants. J Plant Ecol. 2023 16:rtad025. [CrossRef]

- Mironchenko A, Kozłowski J. Optimal allocation patterns and optimal seed mass of a perennial plant. J Theor Biol. 2014, 354:12-24. [CrossRef]

- Roach DA. Plant life histories: ecology, phylogeny, and evolution. Pp. 313. 1999, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0 521 57495 1.

- Adler PB et al. Functional traits explain variation in plant life history strategies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014, 111:740-745. [CrossRef]

- Grotkopp E et al. Toward a causal explanation of plant invasiveness: seedling growth and life-history strategies of 29 pine (Pinus) species. Am Nat. 2002, 159:396-419. [CrossRef]

- Saatkamp A et al. A research agenda for seed-trait functional ecology. New Phytol. 2019, 221:1764-1775. [CrossRef]

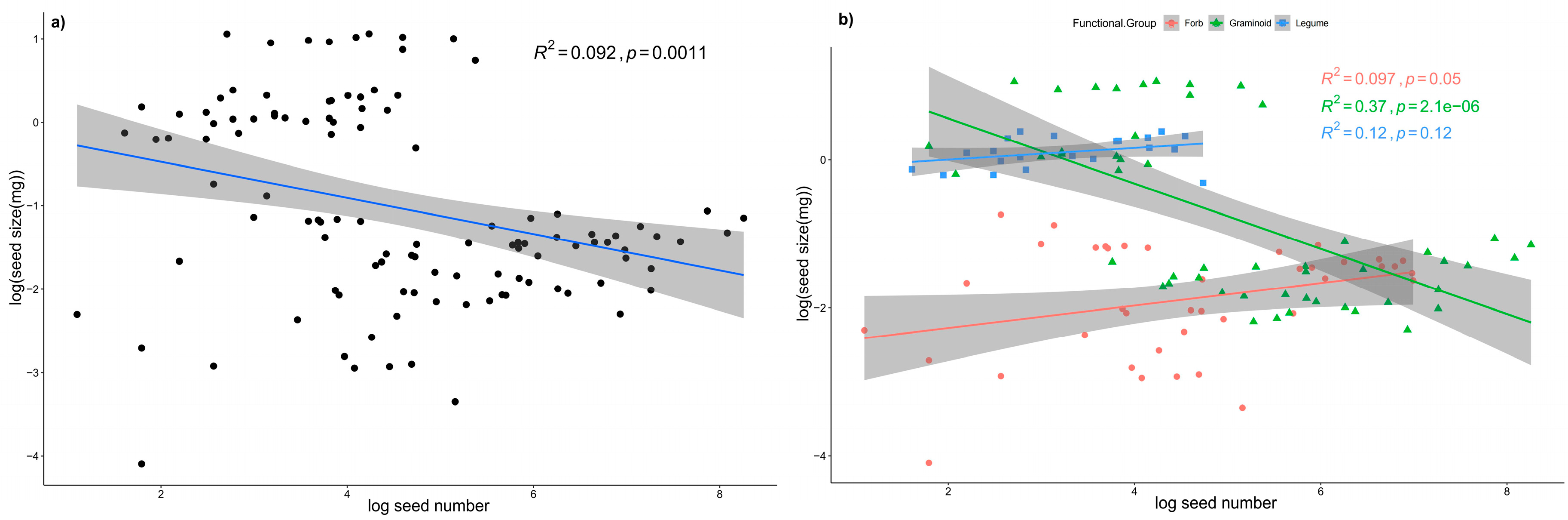

- Zhou X et al. The competition–dispersal trade-off exists in forbs but not in graminoids: A case study from multispecies alpine grassland communities. Ecol Evol. 2019, 9:1403-1409. [CrossRef]

- Geritz SAH. Evolutionarily Stable Seed Polymorphism and Small-Scale Spatial Variation in Seedling Density. Am Nat. 1995, 146:685-707. [CrossRef]

- Kirkby MJ. The theory of island biogeography. Geogr J. 1968, 134:592-592. [CrossRef]

- Westoby M. A leaf-height-seed (LHS) plant ecology strategy scheme. Plant Soil. 1998, 199:213-227. [CrossRef]

- Barthlott W. Epidermal and seed surface characters of plants: systematic applicability and some evolutionary aspects. Nord J Bot. 1981, 1:345-355. [CrossRef]

- Metz J et al. Plant survival in relation to seed size along environmental gradients: a long-term study from semi-arid and Mediterranean annual plant communities. J Ecol. 2010,98:697-704. [CrossRef]

- Agren J. Seed Size and Number in Rubus Chamaemorus: Between-Habitat Variation, and Effects of Defoliation and Supplemental Pollination. J Ecol. 1989, 77:1080-1092. [CrossRef]

- Bogdziewicz M et al. Linking seed size and number to trait syndromes in trees. Glob Ecol Biogeogr. 2023, 32:683-694. [CrossRef]

- Bufford JL, Hulme PE. Seed size–number trade-offs are absent in the introduced range for three congeneric plant invaders. J Ecol. 2021, 109:3849-3860. [CrossRef]

- Qiu T et al. Limits to reproduction and seed size-number trade-offs that shape forest dominance and future recovery. Nat Commun. 2022, 13:2381. [CrossRef]

- Leishman MR, Wright IJ, Moles AT and Westoby, M. The evolutionary ecology of seed size. In Seeds: the ecology of regeneration in plant communities. Wallingford UK: CABI, 2000, pp 31-57. [CrossRef]

- Moles AT et al. Factors that shape seed mass evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005, 102 30:10540-10544. [CrossRef]

- Moles AT, Westoby M. Seed size and plant strategy across the whole life cycle. Oikos. 2006, 113:91-105. [CrossRef]

- Schupp EW et al. Arrival and survival in tropical treefall gaps. Ecology. 1989, 70:562-564. [CrossRef]

- Venable DL, Rees M. The scaling of seed size. J Ecol. 2009, 97:27-31. [CrossRef]

- Han T et al. Are reproductive traits of dominant species associated with specific resource allocation strategies during forest succession in southern China? Ecol. Indic. 2019, 102:538-546. [CrossRef]

- Westoby M, Leishman M, Lord J, Poorter H, Schoen DJ. Comparative ecology of seed size and dispersal. Phil Trans R Soc Lond B. 1996, 351:1309-1318. [CrossRef]

- Venable DL, Brown JS. The selective interactions of dispersal, dormancy, and seed size as adaptations for reducing risk in variable environments. Am Nat. 1988, 131:360-384. [CrossRef]

- Moles AT et al. Global patterns in seed size. Global Ecol Biogeogr. 2006, 16:109-116. [CrossRef]

- Parciak W. Environmental variation in seed number, size, and dispersal of a fleshy-fruited plant. Ecology. 2002, 83:780-793. [CrossRef]

- Venable DL, Lawlor L. Delayed germination and dispersal in desert annuals: Escape in space and time. Oecologia. 1980, 46:272-282. [CrossRef]

- Ashman T-L et al. Pollen limitation of plant reproduction: ecological and evolutionary causes and consequences. Ecology. 2004, 85:2408-2421. [CrossRef]

- Madsen JD. Resource allocation at the individual plant level. Aquat Bot. 1991, 41:67-86. [CrossRef]

- Germain RM, Gilbert B. Hidden responses to environmental variation: maternal effects reveal species niche dimensions. Ecol Lett. 2014, 17:662-669. [CrossRef]

- Lebrija-Trejos E et al. Reproductive traits and seed dynamics at two environmentally contrasting annual plant communities: From fieldwork to theoretical expectations. Isr J Ecol Evol. 2011, 57:73-90. [CrossRef]

- Catling AA et al. Individual vital rates respond differently to local-scale environmental variation and neighbour removal. J Ecol. 2024, 112:1369-1382. [CrossRef]

- Cheplick GP. Plasticity of seed number, mass, and allocation in clones of the perennial grass amphibromus scabrivalvis. Int J Plant Sci. 1995, 156:522-529. [CrossRef]

- Dong B et al. Context-Dependent Parental Effects on Clonal Offspring Performance. Front Plant Sci. 2018, 9:1824. [CrossRef]

- Jakobsson A, Eriksson O. A comparative study of seed number, seed size, seedling size and recruitment in grassland plants. Oikos. 2000, 88:494-502. [CrossRef]

- Wang X et al. Large and non-spherical seeds are less likely to form a persistent soil seed bank. Proc R Soc B. 2024, 291:2023-2764. [CrossRef]

- Thürig B et al. Seed production and seed quality in a calcareous grassland in elevated CO2. Global Change Biology. 2003, 9: 873-884. [CrossRef]

- Guo H et al. Geographic variation in seed mass within and among nine species of Pedicularis (Orobanchaceae): effects of elevation, plant size and seed number per fruit. J Ecol. 2010, 98:1232-1242. [CrossRef]

- Cochrane A et al. Will among-population variation in seed traits improve the chance of species persistence under climate change? Glob Ecol Biogeogr. 2015, 24:12-24. [CrossRef]

- Vandvik V et al. Seed banks are biodiversity reservoirs: species–area relationships above versus below ground. Oikos. 2016, 125:218-228. [CrossRef]

- Leishman MR, Murray BR. The relationship between seed size and abundance in plant communities: model predictions and observed patterns. Oikos. 2001, 94:151-161. [CrossRef]

- Parker VT, Ingalls SB. Seed size–seed number trade-offs: influence of seed size on the density of fire-stimulated persistent soil seed banks. Am J Bot. 2022, 109:486-493. [CrossRef]

- Baker R et al. A multi-level test of the seed number/size trade-off in two Scandinavian communities. PLoS One. 2018, 13:e0201175. [CrossRef]

- Smith CC, Fretwell SD. The optimal balance between size and number of offspring. Am Nat. 1974, 108:499-506. [CrossRef]

- Leishman MR. Does the seed size/number trade-off model determine plant community structure? An assessment of the model mechanisms and their generality. Oikos. 2001, 93:294-302. [CrossRef]

- Sadras VO. Evolutionary aspects of the trade-off between seed size and number in crops. Field Crop Res. 2007, 100:125-138. [CrossRef]

- Turnbull LA et al. Are plant populations seed-limited? A review of seed sowing experiments. Oikos. 2000, 88:225-238. [CrossRef]

- Dani KGS, Kodandaramaiah U. Plant and Animal Reproductive Strategies: Lessons from Offspring Size and Number Tradeoffs. Front Ecol Evol. 2017, 5:38. [CrossRef]

- Lönnberg K, Eriksson O. Rules of the seed size game: contests between large-seeded and small-seeded species. Oikos. 2013, 122:1080-1084. [CrossRef]

- Endara MJ, Coley PD. The resource availability hypothesis revisited: a meta-analysis. Funct Ecol. 2011, 25:389-398. [CrossRef]

- López-Goldar X et al. Resource availability drives microevolutionary patterns of plant defences. Funct Ecol. 2020, 34:1640-1652. [CrossRef]

- Ben-Hur E, Kadmon R. An experimental test of the relationship between seed size and competitive ability in annual plants. Oikos. 2015, 124:1346-1353. [CrossRef]

- Germain RM et al. Maternal provisioning is structured by species’ competitive neighborhoods. Oikos. 2019, 128:45-53. [CrossRef]

- Kang X et al. Regional gradients in intraspecific seed mass variation are associated with species biotic attributes and niche breadth. AoB Plants. 2022, 14:plac013. [CrossRef]

- Venable DL. Size-Number Trade-Offs and the Variation of Seed Size with Plant Resource Status. Am Nat. 1992, 140:287-304. [CrossRef]

- Yang YY, Kim JG. The optimal balance between sexual and asexual reproduction in variable environments: a systematic review. J Ecology Environ. 2016, 40. [CrossRef]

- Hutchings MJ. Differential foraging for resources, and structural plasticity in plants. Trends Ecol Evol. 1988, 3:200-204. [CrossRef]

- Xiao Y et al. Trade-offs among growth, clonal, and sexual reproduction in an invasive plant Spartina alterniflora responding to inundation and clonal integration. Hydrobiologia. 2011, 658:353-363. [CrossRef]

- Lei SA. Benefits and Costs of Vegetative and Sexual Reproduction in Perennial Plants: A Review of Literature. Journal of the Arizona-Nevada Academy of Science. 2010, 42:9-14. [CrossRef]

- Parvinen K. Metapopulation dynamics and the evolution of dispersal. In complex population dynamics: nonlinear modeling in ecology, epidemiology and genetics, 2007, pp 77-107. [CrossRef]

- Cook BI et al. Divergent responses to spring and winter warming drive community level flowering trends. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012, 109:9000-9005. [CrossRef]

- Wu L et al. Reduction of microbial diversity in grassland soil is driven by long-term climate warming. Nat Microbiol. 2022, 7:1054-1062. [CrossRef]

- Zhou X et al. Different categories of biodiversity explain productivity variation after fertilization in a Tibetan alpine meadow community. Ecol Evol. 2017, 7:3464-3474. [CrossRef]

- Li KH et al. Response of alpine grassland to elevated nitrogen deposition and water supply in China. Oecologia. 2015, 177(1): 65-72. https://doi:10.1007/s00442-014-3122-4.

- Reekie EG, Bazzaz FA. Reproductive Effort in Plants Effect of Reproduction on Vegetative Activity. Am Nat. 1987, 129:907-919. [CrossRef]

- Harper JL et al. The Shapes and Sizes of Seeds. Annu Rev Ecol Syst. 1970, 1:327-356. [CrossRef]

- Venable DL. Bet hedging in a guild of desert annuals. Ecology. 2007, 88:1086-1090. [CrossRef]

- Bellés-Sancho P et al. Nitrogen-Fixing Symbiotic Paraburkholderia Species: Current Knowledge and Future Perspectives. Nitrogen. 2023, 4:135-158. [CrossRef]

- Remigi P et al. Symbiosis within Symbiosis: Evolving Nitrogen-Fixing Legume Symbionts. Trends Microbiol. 2016, 24:63-75. [CrossRef]

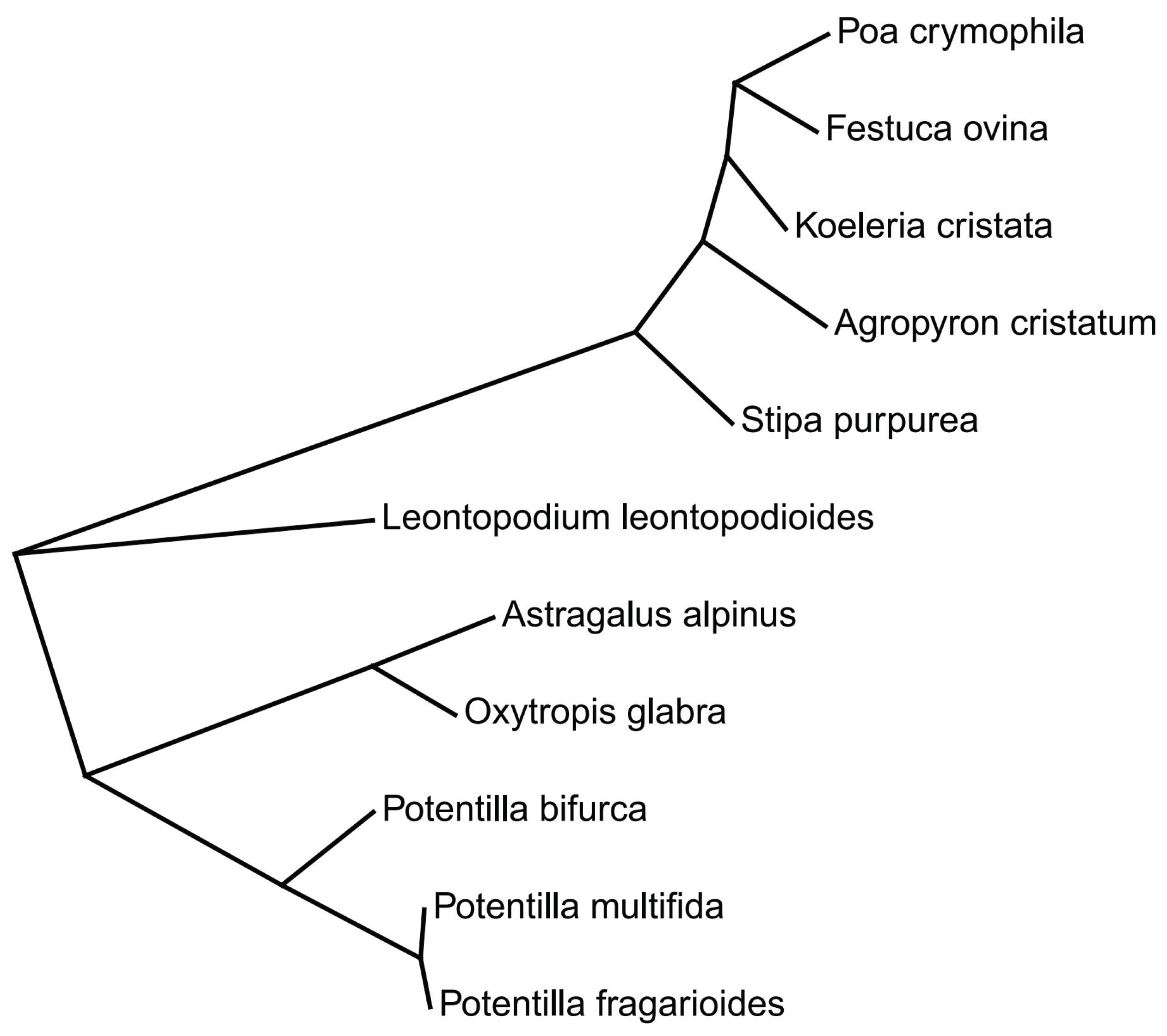

- Webb CO et al. Phylogenies and Community Ecology. Annu Rev Ecol Syst. 2002, 33:475-505. [CrossRef]

- Tamura K et al. MEGA5: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Using Maximum Likelihood, Evolutionary Distance, and Maximum Parsimony Methods. Mol Biol Evol. 2011, 28:2731-2739. [CrossRef]

| Species | Functional group | Seed size (mg) | Seed number | Reproduction type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agropyron cristatum | graminoid | 0.9879 | 98 | sexual+ clonal |

| Festuca ovina | graminoid | 0.2458 | 1315 | sexual+ clonal |

| Koeleria cristata | graminoid | 0.2102 | 1420 | sexual+ clonal |

| Poa crymophila | graminoid | 0.2 | 273 | sexual+ clonal |

| Stipa purpurea | graminoid | 2.68 | 113 | sexual+ clonal |

| Leontopodium leontopodioides | forb | 0.0547 | 191 | sexual |

| Potentilla bifurca | forb | 0.3431 | 36 | sexual |

| Potentilla fragarioides | forb | 0.2315 | 551 | sexual |

| Potentilla multifida | forb | 0.131 | 91 | sexual |

| Astragalus multicaulis | legume | 2.435 | 45 | sexual |

| Oxytrois glabra | legume | 1.216 | 42 | sexual |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).