Submitted:

22 July 2025

Posted:

23 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

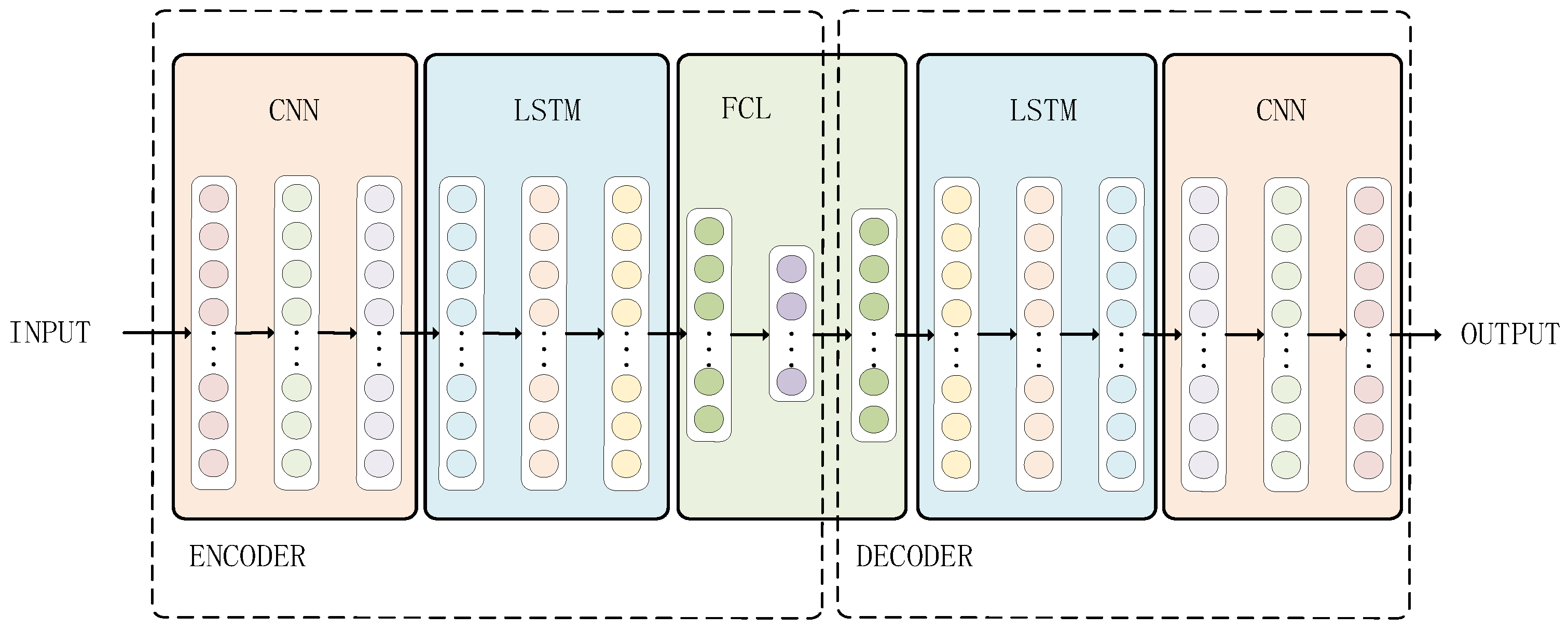

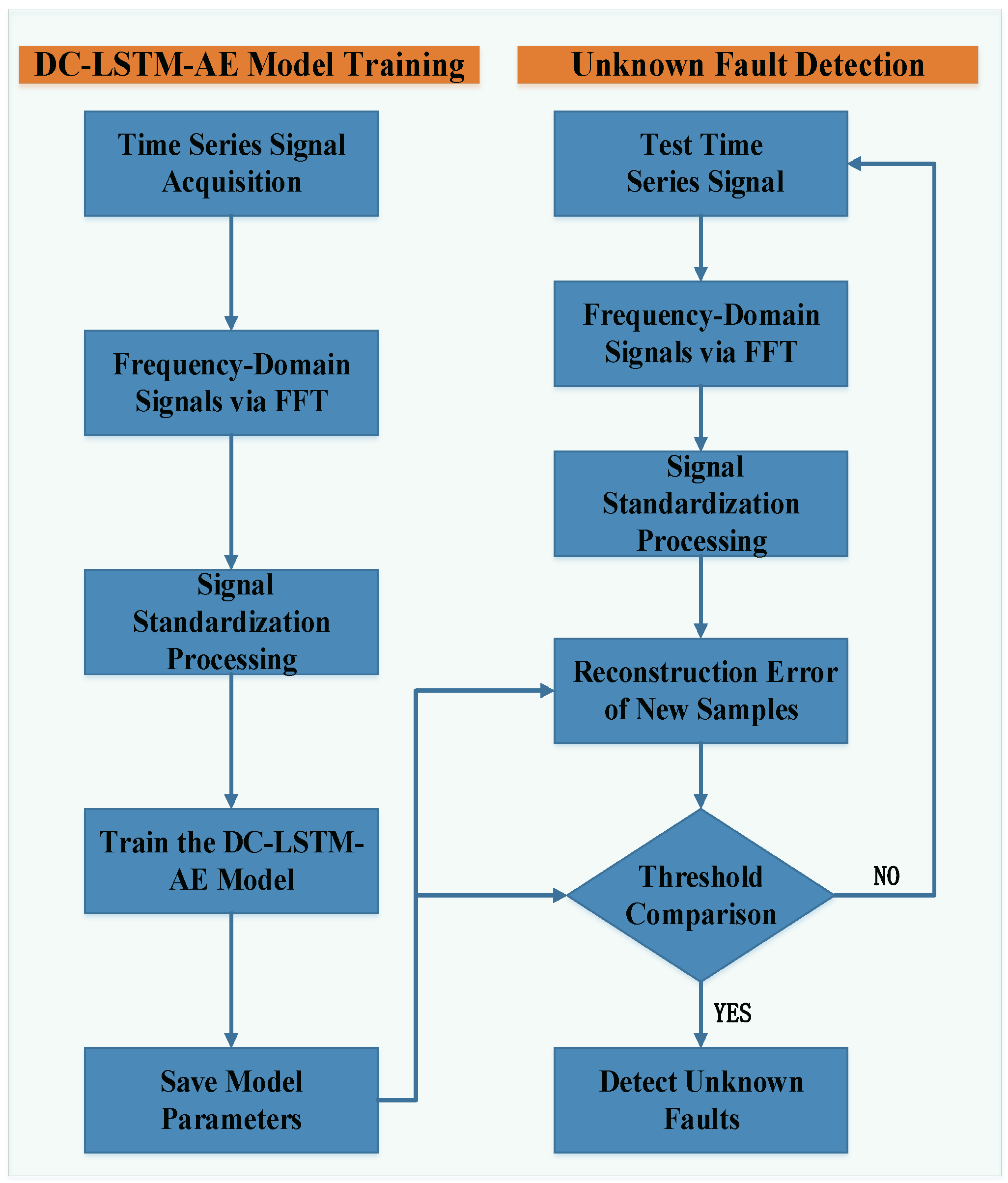

- This paper proposes a DC-LSTM-AE model based on deep CNN and LSTM. The model extracts spatial features via a five-layer CNN and captures the long-term dependencies of time-series data through LSTM, enabling spatiotemporal feature fusion for high-dimensional nonlinear time-series signals in industrial environments. This approach addresses traditional autoencoders’ limitations in extracting features from complex signals and enhances unknown fault detection performance.

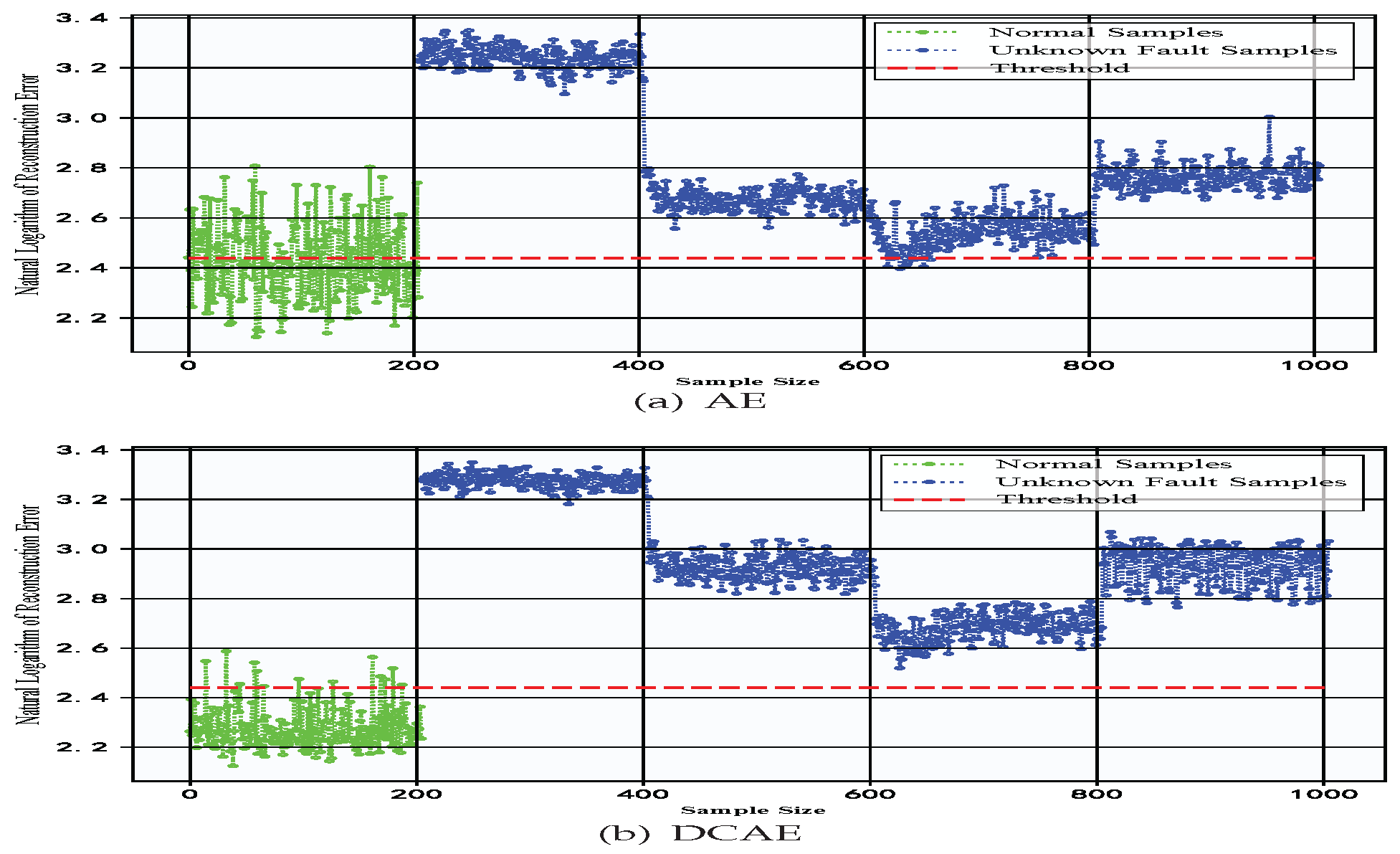

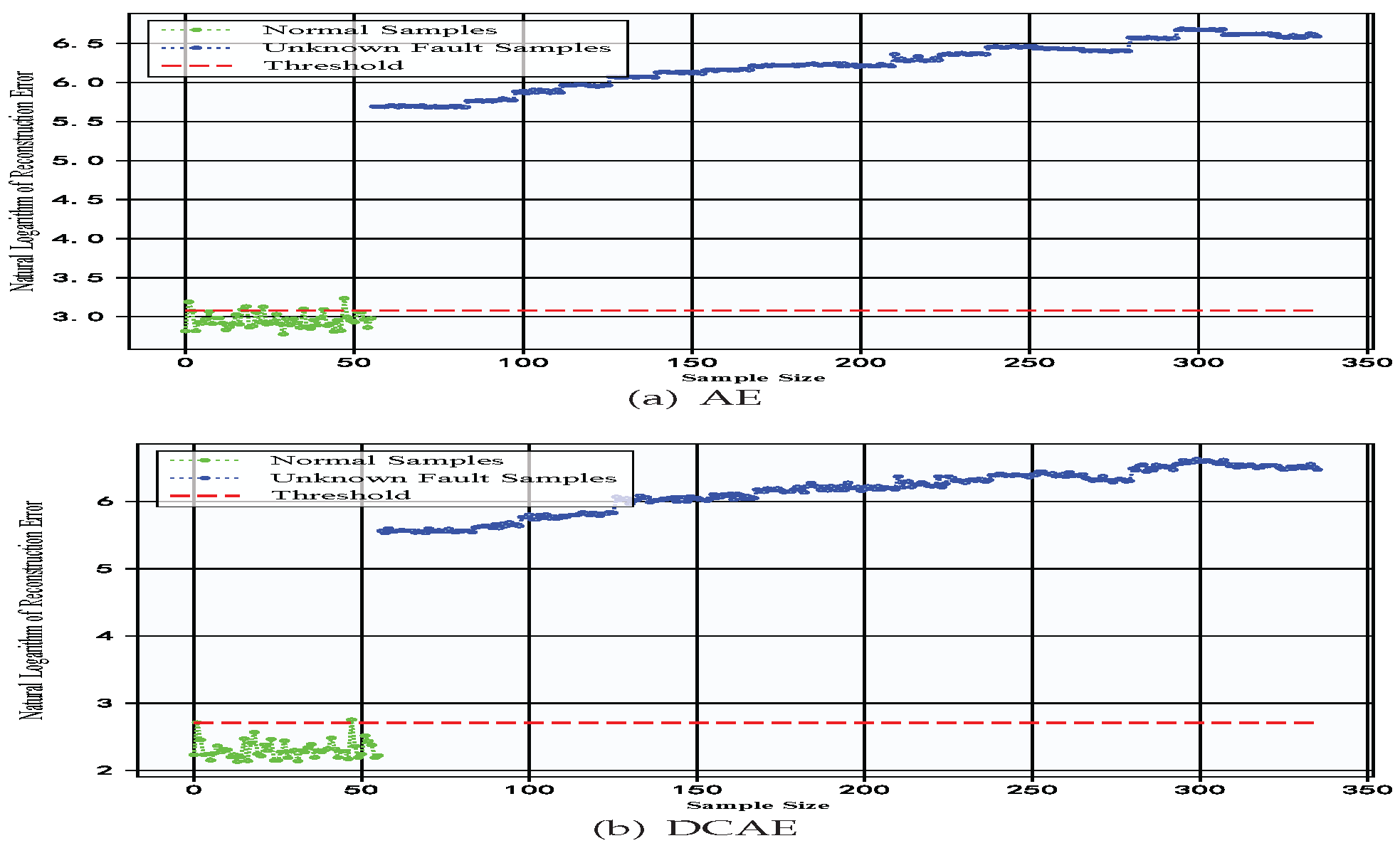

- To address the core problem of scarce fault samples in industrial scenarios, we design a training procedure using only normal samples. By leveraging the reconstruction error characteristics of autoencoders, a benchmark feature space is constructed through training with normal samples. When abnormal samples are input, their absence from the training process leads to significantly increased reconstruction errors. Anomaly detection is achieved by setting thresholds based on the Pauta criterion. This strategy breaks through the dependence of traditional supervised learning on fault samples, providing a feasible solution for early equipment maintenance.

- In this study, we employ sliding windows and fast Fourier transform (FFT) to convert time-series signals into spectral features. This reduces data dimensions while preserving key information, enhances model training stability, and lowers memory consumption. The L2 regularization term is introduced to optimize the loss function, suppress overfitting, and enhance the model’s generalization ability. By dynamically adjusting the regularization coefficient through cross-validation, a balance is achieved between model complexity and detection accuracy, making it suitable for real-time detection requirements in industrial sites.

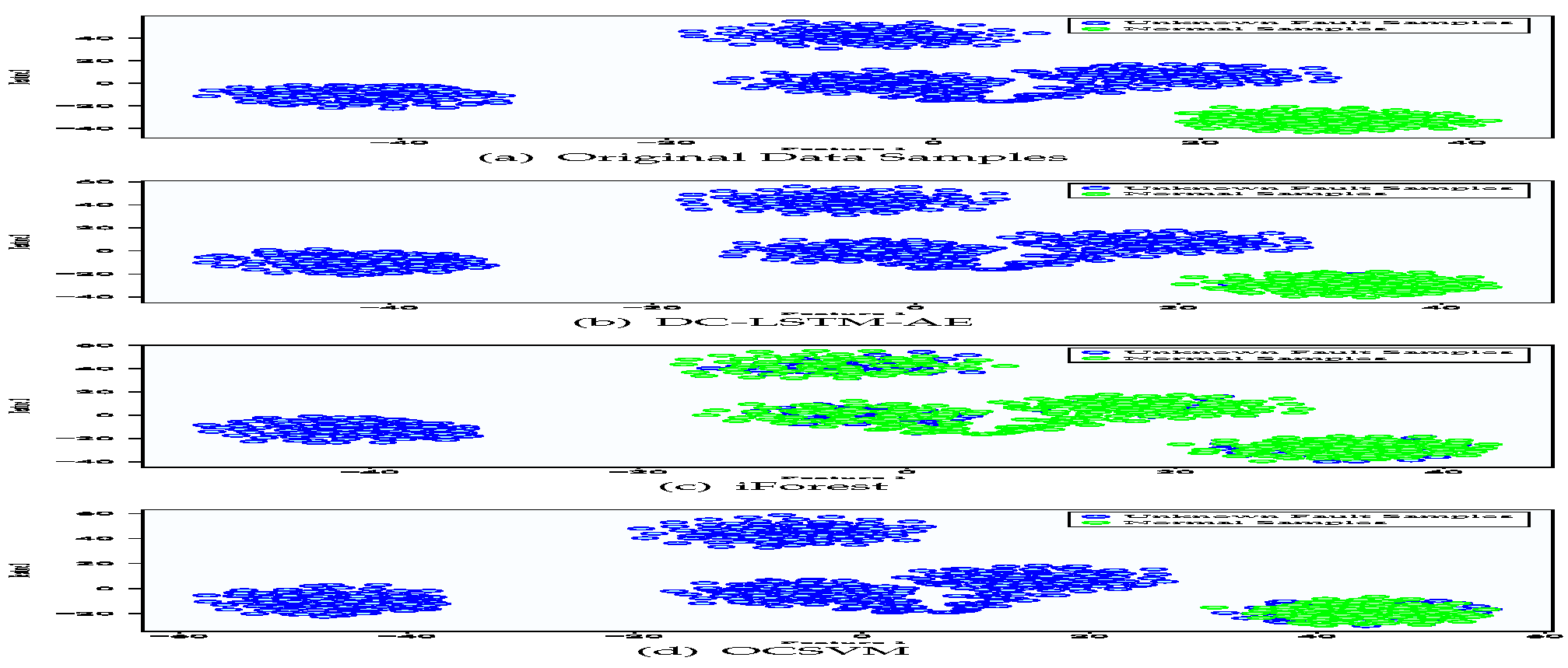

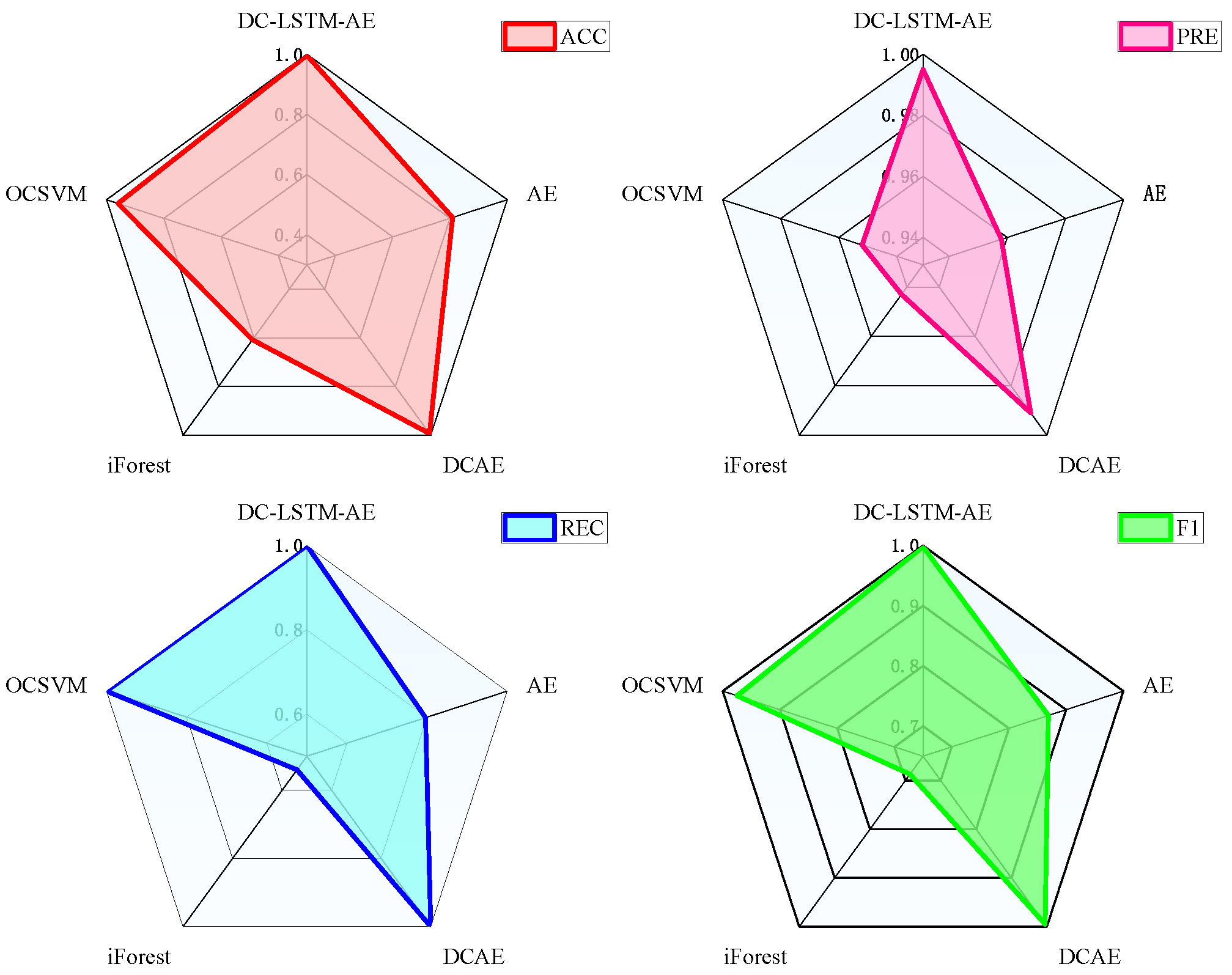

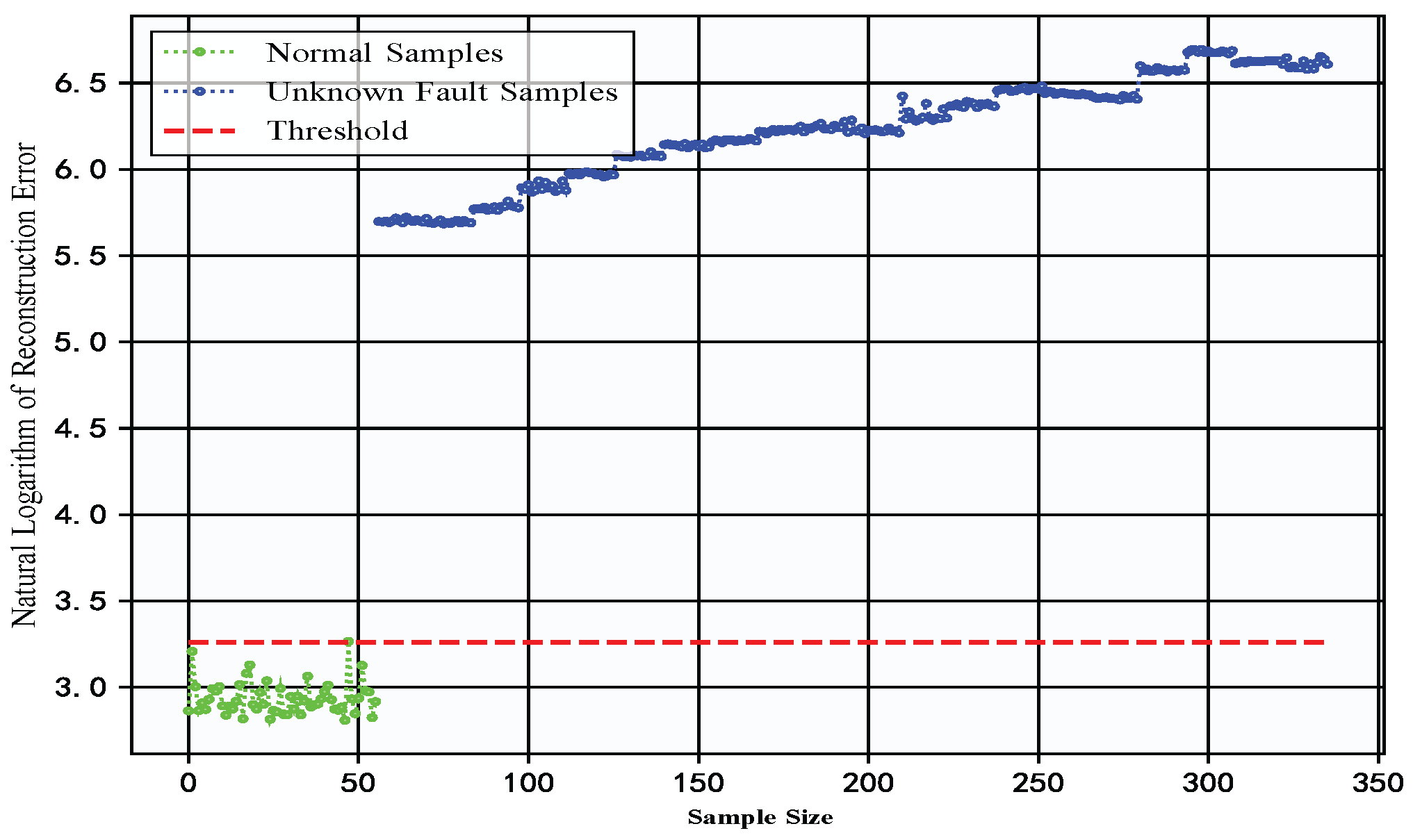

- We evaluate our method using two industrial datasets: the Southeast University gearbox dataset (containing four fault types) and a constant-speed water pump dataset from factory settings (with one fault type). Compared to traditional autoencoders, deep convolutional autoencoders, and some machine learning algorithms, the results show that DC-LSTM-AE significantly outperforms the comparative methods in metrics such as accuracy and precision. Especially when processing unknown faults with high feature similarity, it exhibits more pronounced reconstruction error distinctions. These results conclusively validate the method’s effectiveness and industrial applicability.

2. System Model

3. The Proposed DC-LSTM-AE Algorithms

3.1. The CNN Algorithm

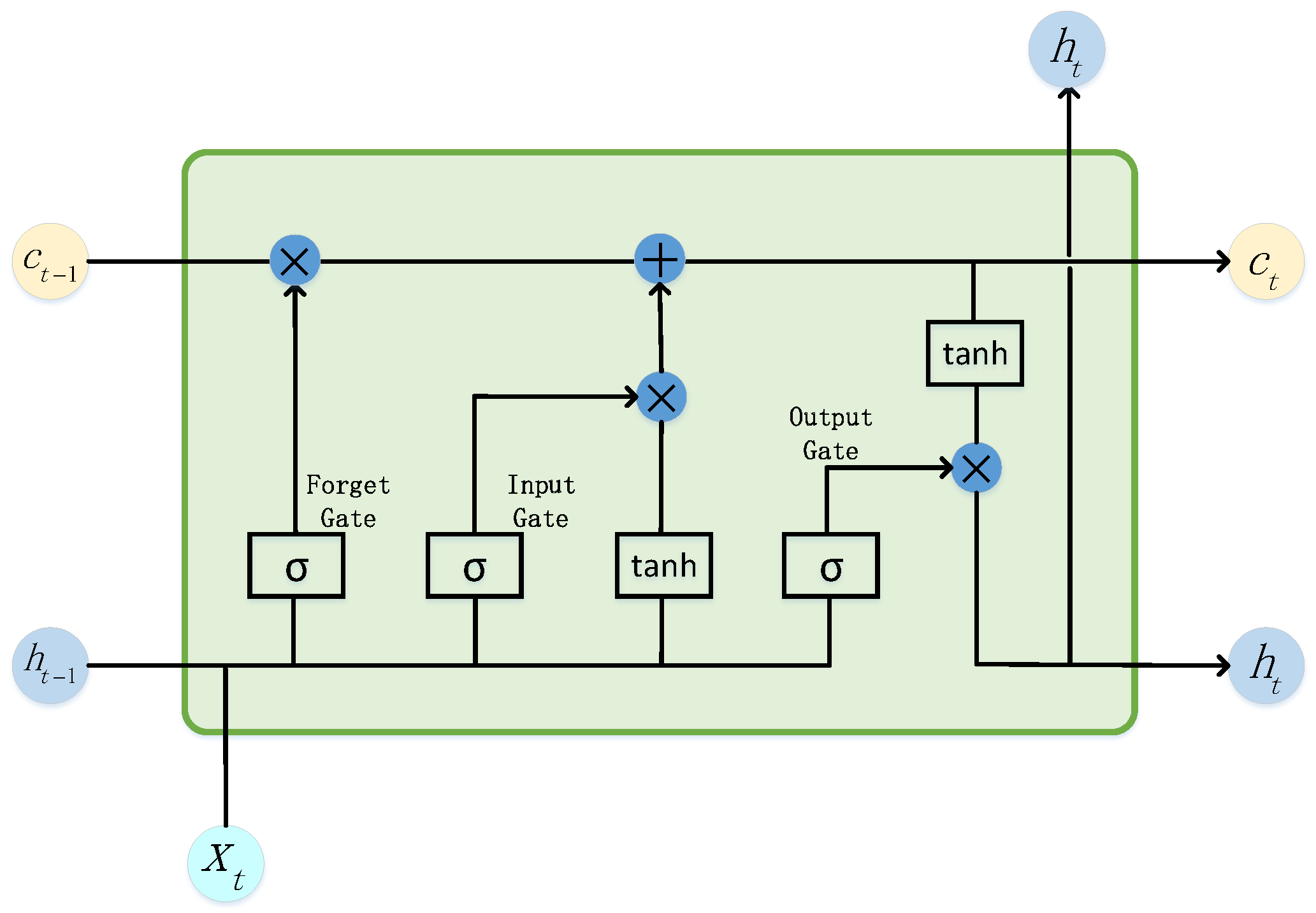

3.2. The LSTM Algorithm

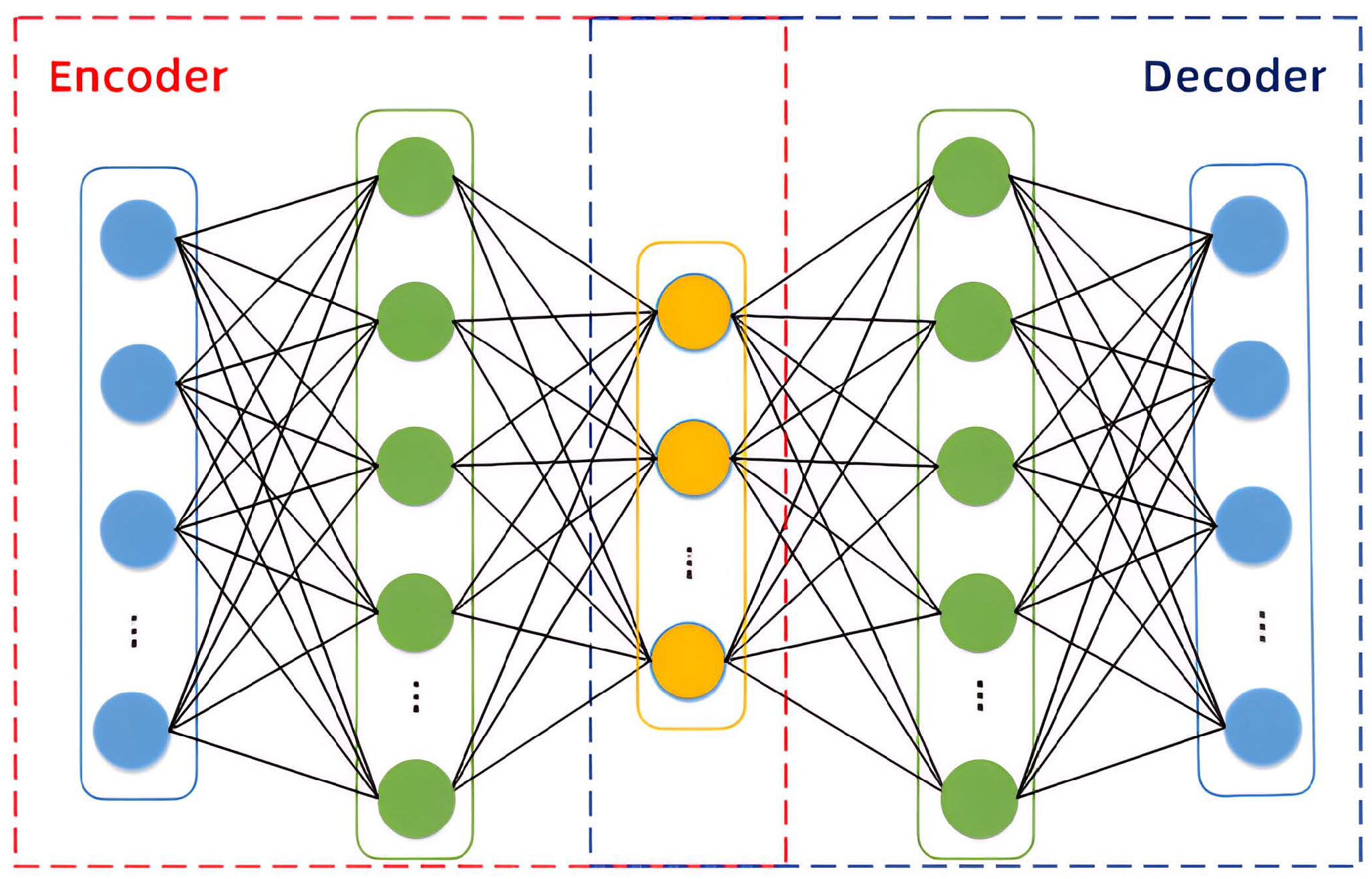

3.3. The AE Algorithm

3.4. The DC-LSTM-AE Algorithm

4. Results Simulation and Discussion

4.1. Experimental Setup

4.2. Experimental Datasets

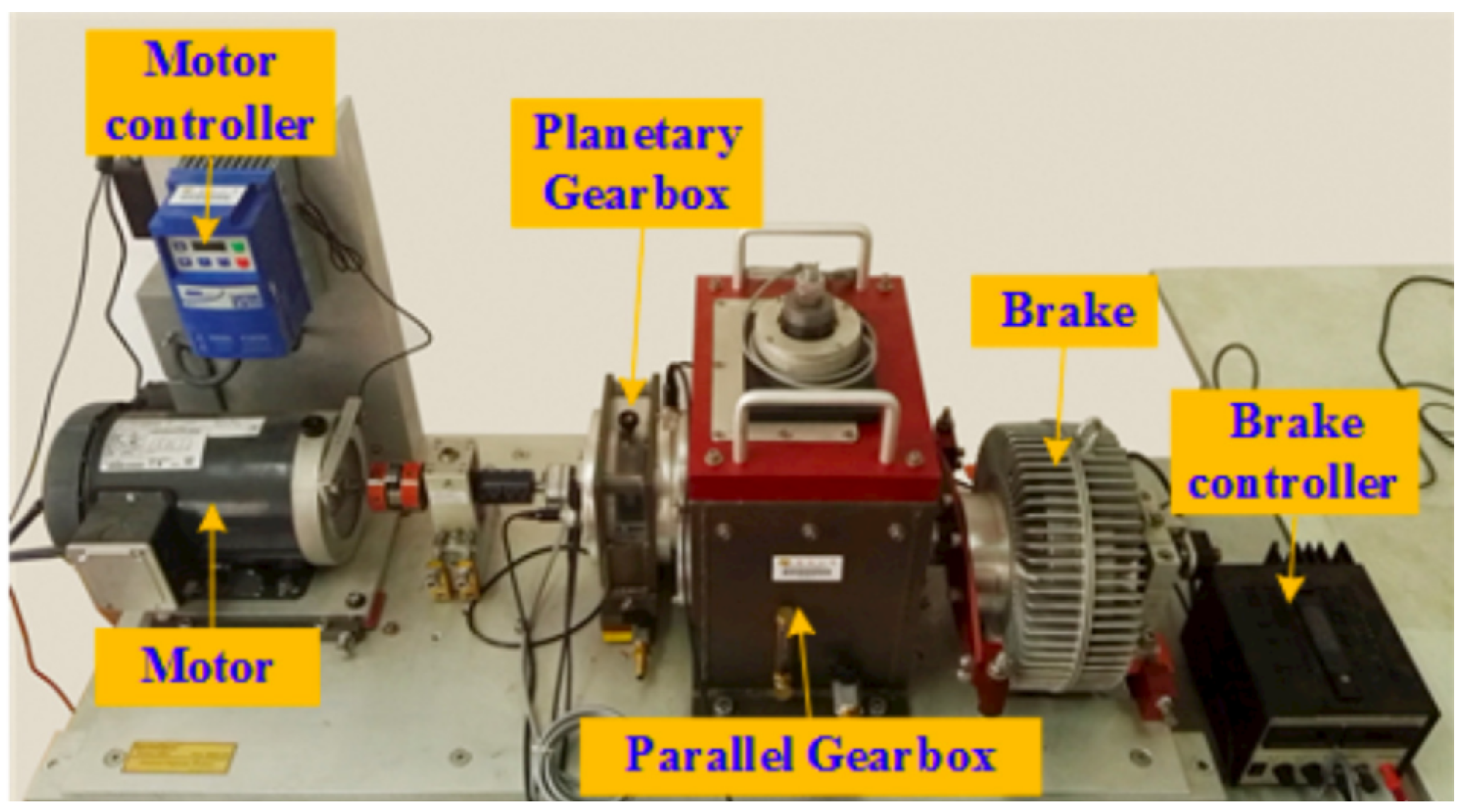

4.2.1. The Gearbox Dataset from Southeast University

4.2.2. Constant-Speed Water Pump Dataset

4.3. Evaluation Metrics

4.4. Experimental Results and Analysis

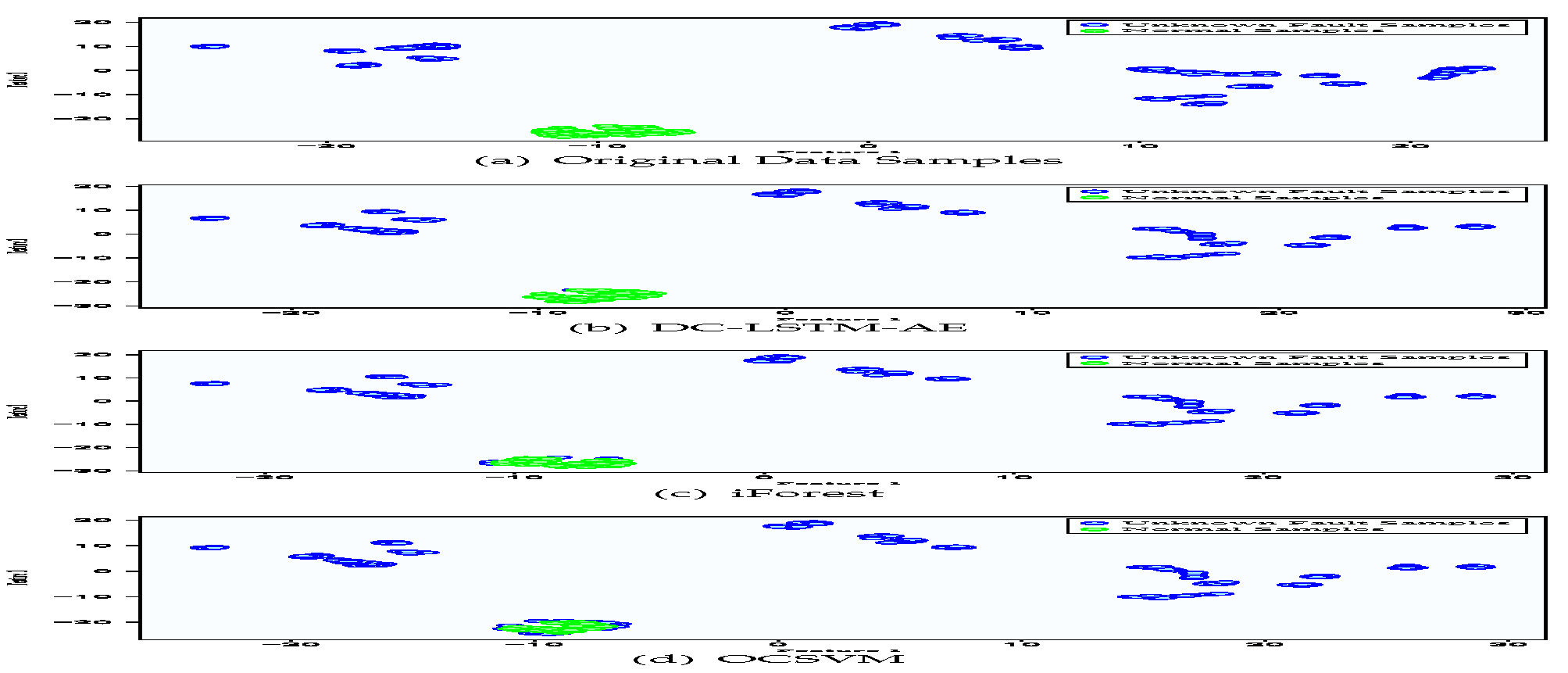

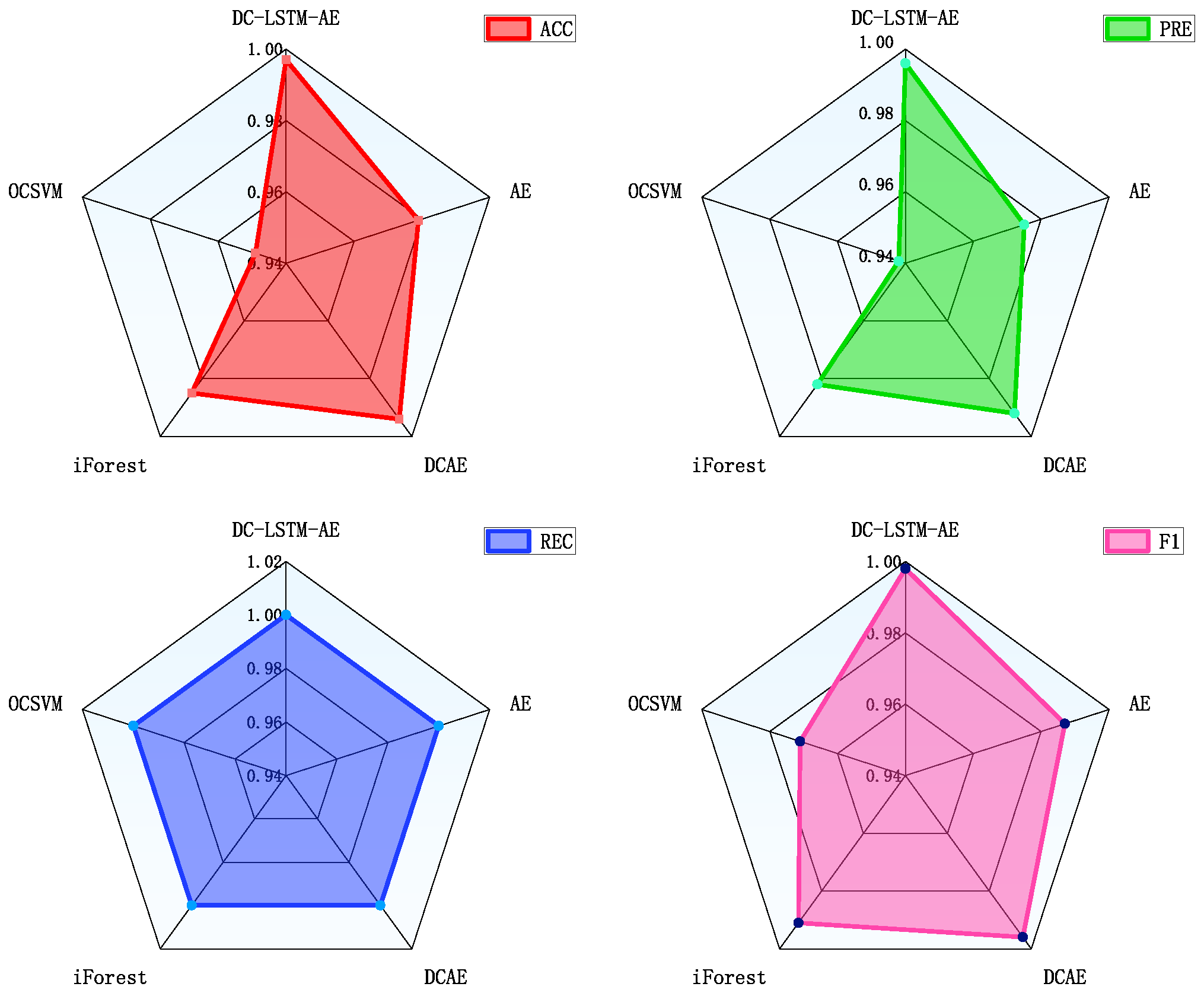

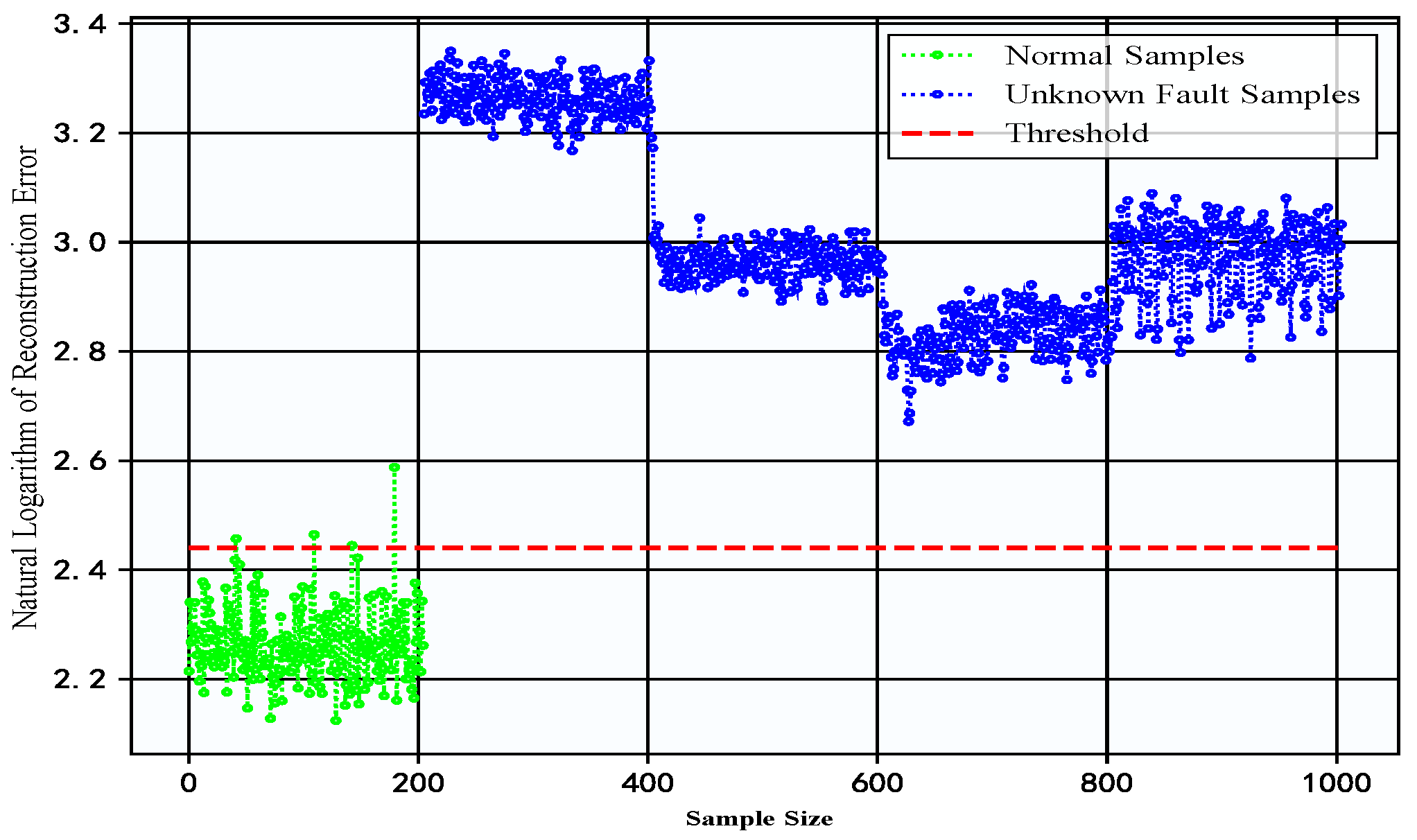

4.4.1. Experimental Verification of Southeast University Gearbox Dataset

4.4.2. Experimental Validation of Constant-Speed Water Pump Dataset

5. Conclusions

References

- Liu, Y.; Chi, C.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, T. 2022. Identification and Resolution for Industrial Internet: Architecture and Key Technology. IEEE Internet of Things Journal. [CrossRef]

- F. Piccialli, N. Bessis, and E. Cambria, “Guest editorial: Industrial internet of things: Where are we and what is next,” IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics, vol. 17, no. 11, pp. 7700–7703, 2021. [CrossRef]

- W. Z. Khan, M. Rehman, H. M. Zangoti, and M. K. Afzal, “Industrial internet of things: Recent advances, enabling technologies and open challenges,” Computers & electrical engineering, vol. 81, p. 106522, 2020.

- A. A. Zainuddin, D. Handayani, and I. H. Mohd Ridza, “Converging for security: Blockchain, internet of things, artificial intelligence - why not together,” in 2024 IEEE 14th Symposium on Computer Applications and Industrial Electronics (ISCAIE), 2024, pp. 181–186.

- L. D. Xu, W. He, and S. Li, “Internet of things in industries: A survey,” IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics, vol. 10, no. 4, pp. 2233–2243, 2014.

- F. Cao, “Research on machine tool fault diagnosis and maintenance optimization in intelligent manufacturing environments,” Journal of Electronic Research and Application, vol. 8, no. 4, pp. 108–114, 2024.

- J. Sun, J. Liu, and Y. Liu, “A blocking method for overload-dominant cascading failures in power grid based on source and load collaborative regulation,” International Journal of Energy Research, vol. 2024, 2024. [CrossRef]

- C. Arindam and S. K. Ghosh, “Predictive maintenance of vehicle fleets through hybrid deep learning-based ensemble methods for industrial IoT datasets,” Logic Journal of the IGPL, 2024.

- S. Hong, “Advanced data-driven fault detection and diagnosis in chemical processes: Revolutionizing industrial safety and efficiency,” Industrial Chemistry, vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 1–2, 2024.

- H. T. Tai, Y.-W. Youn, H.-S. Choi, and Y.-H. Kim, “Partial discharge diagnosis using semi-supervised learning and complementary labels in gas-insulated switchgear,” IEEE Access, vol. 13, pp. 58 722–58 734, 2025.

- X. Cao and K. Peng, “Stochastic uncertain degradation modeling and remaining useful life prediction considering aleatory and epistemic uncertainty,” IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement, vol. 72, pp. 1–12, 2023.

- J. Qi, Z. Chen, Y. Song, and J. Xia, “Remaining useful life prediction combining advanced anomaly detection and graph isomorphic network,” IEEE Sensors Journal, vol. 24, no. 22, pp. 38 365–38 376, 2024.

- K. Choi, J. Yi, and C. Park, “Deep learning for anomaly detection in time-series data: Review, analysis, and guidelines,” IEEE Access, vol. 9, pp. 120 043–120 065, 2021.

- H. Asmat, I. Ud Din, and A. Almogren, “Digital twin with soft actor-critic reinforcement learning for transitioning from industry 4.0 to 5.0,” IEEE Access, vol. 13, pp. 40 577–40 593, 2025.

- J. Zhou, J. Yang, and S. Xiang, “Remaining useful life prediction methodologies with health indicator dependence for rotating machinery: A comprehensive review,” IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement, vol. 74, pp. 1–19, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Z.-L. Ma, X.-J. Li, and F.-Q. Nian, “An interpretable fault detection approach for industrial processes based on improved autoencoder,” IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement, vol. 74, pp. 1–13, 2025.

- M. Lv, Y. Li, and H. Liang, “A spatial-temporal variational graph attention autoencoder using interactive information for fault detection in complex industrial processes,” IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems, vol. 35, no. 3, pp. 3062–3076, 2024.

- D. Drinic, M. Novicic, and G. Kvascev, “Detection of lr-ddos attack based on hybrid neural networks cnn-lstm and cnn-autoencoder,” in 2024 11th International Conference on Electrical, Electronic and Computing Engineering (IcETRAN), 2024, pp. 1–4.

- X. Li, P. Li, and Z. Zhang, “Cnn-lstm-based fault diagnosis and adaptive multichannel fusion calibration of filament current sensor for mass spectrometer,” IEEE Sensors Journal, vol. 24, no. 2, pp. 2255–2269, 2024.

- J. Fu, S. Peyghami, and A. N¨²ez, “A tractable failure probability prediction model for predictive maintenance scheduling of large-scale modular-multilevel-converters,” IEEE Transactions on Power Electronics, vol. 38, no. 5, pp. 6533–6544, 2023.

- Z. Wang, W. Shangguan, and C. Peng, “A predictive maintenance strategy for a single device based on remaining useful life prediction information: A case study on railway gyroscope,” IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement, vol. 73, pp. 1–14, 2024.

- Y. Lecun, Y. Bengio, and G. Hinton, “Deep learning,” Nature, vol. 521, no. 7553, p. 436, 2015.

- F. Jia, Y. Lei, J. Lin, X. Zhou, and N. Lu, “Deep neural networks: A promising tool for fault characteristic mining and intelligent diagnosis of rotating machinery with massive data,” Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing, vol. 72-73, pp. 303–315, 2016. [CrossRef]

- R. M. Souza, E. G. S. Nascimento, and U. A. Miranda, “Deep learning for diagnosis and classification of faults in industrial rotating machinery,” Computers and Industrial Engineering, vol. 153, p. 107060, 2020.

- T. Han, LongwenYin, and ZhongjunTan, “Rolling bearing fault diagnosis with combined convolutional neural networks and support vector machine,” Measurement, vol. 177, no. 1, 2021.

- Y. Sun, H. Zhang, and T. Zhao, “A new convolutional neural network with random forest method for hydrogen sensor fault diagnosis,” IEEE Access, vol. PP, no. 99, pp. 1–1, 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. Yin, Y. Yan, and Z. Zhang, “Fault diagnosis of wind turbine gearbox based on the optimized LSTM neural network with cosine loss,” Sensors (Basel, Switzerland), vol. 20, no. 8, 2020.

- A. Khorram, M. Khalooei, and M. Rezghi, “End-to-end cnn plus lstm deep learning approach for bearing fault diagnosis,” Applied Intelligence: The International Journal of Artificial Intelligence, Neural Networks, and Complex Problem-Solving Technologies, no. 2, p. 51, 2021.

- J. S. A, D. P. B, and Z. P. B, “Planetary gearbox fault diagnosis using bidirectional-convolutional lstm networks,” Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing, vol. 162.

- M. Jalayer, C. Orsenigo, and C. Vercellis, “Fault detection and diagnosis for rotating machinery: A model based on convolutional LSTM, fast fourier and continuous wavelet transforms,” Computers in Industry, vol. 125, 2020.

- Y. Qiao, K. Wu, and P. Jin, “Efficient anomaly detection for high-dimensional sensing data with one-class support vector machine,” IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control, vol. 35, no. 1, p. 14, 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. S. Sadooghi and S. E. Khadem, “Improving one class support vector machine novelty detection scheme using nonlinear features,” Pattern Recognition, p. S0031320318301663, 2018.

- J. Pang, X. Pu, and C. Li, “A hybrid algorithm incorporating vector quantization and one-class support vector machine for industrial anomaly detection,” IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics, vol. 18, no. 12, pp. 8786–8796, 2022.

- X. Song, G. Liu, and G. Li, “An innovative application of isolation-based nearest neighbor ensembles on hyperspectral anomaly detection,” IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters, vol. 21, pp. 1–5, 2024.

- C. Li, L. Guo, H. Gao, and Y. Li, “Similarity-measured isolation forest: Anomaly detection method for machine monitoring data,” IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement, vol. 70, pp. 1–12, 2021.

- H. Sun, S. Yu, and Z. Li, “Fault diagnosis method of turbine guide bearing based on multi-sensor information fusion and neural network,” IOP Publishing Ltd, 2025.

- H. Ding, K. Ding, J. Zhang, Y. Wang, L. Gao, Y. Li, F. Chen, Z. Shao, and W. Lai, “Local outlier factor-based fault detection and evaluation of photovoltaic system - sciencedirect,” Solar Energy, vol. 164, pp. 139–148, 2018.

- J. Qian, Z. Song, and Y. Yao, “A review on autoencoder based representation learning for fault detection and diagnosis in industrial processes,” Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems, 2022.

- S. Plakias and Y. S. Boutalis, “A novel information processing method based on an ensemble of auto-encoders for unsupervised fault detection,” Computers in Industry, p. 142, 2022.

- E. Principi, D. Rossetti, and S. Squartini, “Unsupervised electric motor fault detection by using deep autoencoders,” IEEE/CAA Journal of Automatica Sinica, vol. 6, no. 002, pp. 441–451, 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. Wu, Z. Zhao, and C. Sun, “Fault-attention generative probabilistic adversarial autoencoder for machine anomaly detection,” IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics, vol. 16, no. 12, pp. 7479–7488, 2020.

- J. K. Chow, Z. Su, and J. Wu, “Anomaly detection of defects on concrete structures with the convolutional autoencoder,” Advanced Engineering Informatics, vol. 45, no. 3, p. 101105, 2020.

- C. Zhang, D. Hu, and T. Yang, “Anomaly detection and diagnosis for wind turbines using long short-term memory-based stacked denoising autoencoders and xgboost,” Reliability Engineering and System Safety, vol. 222, 2022.

- E. Karapalidou, N. Alexandris, and E. Antoniou, “Implementation of a sequence-to-sequence stacked sparse long short-term memory autoencoder for anomaly detection on multivariate timeseries data of industrial blower ball bearing units,” Sensors (14248220), vol. 23, no. 14, 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. Yin, S. Zhang, and J. Wang, “Anomaly detection based on convolutional recurrent autoencoder for IoT time series,” IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics: Systems, vol. 52, no. 1, pp. 112–122, 2022.

- H. Xiang, Aijun Su, “Fault detection of wind turbine based on scada data analysis using CNN and LSTM with attention mechanism,” Measurement, vol. 175, no. 1, 2021.

- D. Zhang, L. Zou, X. Zhou, and F. He, “Integrating feature selection and feature extraction methods with deep learning to predict clinical outcome of breast cancer,” IEEE Access, pp. 1–1, 2018.

- J. Jiao, M. Zhao, J. Lin, and K. Liang, “A comprehensive review on convolutional neural network in machine fault diagnosis,” Neurocomputing, vol. 417, 2020. [CrossRef]

- K. O’Shea and R. Nash, “An introduction to convolutional neural networks,” Computer Science, 2015. [CrossRef]

- T. Mikolov, M. Karafi¨¢t, L. Burget, J. Cernock, and S. Khudanpur, “Recurrent neural network based language model,” in Interspeech, Conference of the International Speech Communication Association, Makuhari, Chiba, Japan, September, 2015.

- Y. Yu, X. Si, C. Hu, and J. Zhang, “A review of recurrent neural networks: Lstm cells and network architectures,” Neural Computation, vol. 31, no. 7, pp. 1235–1270, 2019.

- A. Makhzani and B. Frey, “k-sparse autoencoders,” Computer Science, 2013.

- Z. Chen, C. K. Yeo, B. S. Lee, and C. T. Lau, “Autoencoder-based network anomaly detection,” in 2018 Wireless Telecommunications Symposium (WTS), 2018.

- A. Curtis, T. Smith, B. Ziganshin, and J. Elefteriades, “The mystery of the z-score,” Aorta, vol. 4, no. 04, pp. 124–130, 2016.

- M. A. Panza, M. Pota, and M. Esposito, “Anomaly detection methods for industrial applications: A comparative study,” Electronics (2079-9292), vol. 12, no. 18, 2023. [CrossRef]

- V. D. M. Laurens and G. Hinton, “Visualizing data using t-SNE,” Journal of Machine Learning Research, vol. 9, no. 2605, pp. 2579–2605, 2008.

| Encoder | Decoder | ||

| Network Layer | Input Dimension | Network Layer | Output Dimension |

| Input Layer | FC Layer 3 | ||

| Conv Layer 1 | FC Layer 4 | ||

| Conv Layer 2 | LSTM Network | ||

| Conv Layer 3 | Deconv Layer 1 | ||

| Conv Layer 4 | Deconv Layer 2 | ||

| Conv Layer 5 | Deconv Layer 3 | ||

| LSTM Network | Deconv Layer 4 | ||

| FC Layer 1 | Deconv Layer 5 | ||

| FC Layer 2 | Output Layer | ||

| Fault Type | All Samples | Training | Testing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | 1022 | 817 | 205 |

| Crack on gear | 200 | 0 | 200 |

| Broken tooth on gear | 200 | 0 | 200 |

| Crack at gear root | 200 | 0 | 200 |

| Wear on gear surface | 200 | 0 | 200 |

| Fault Type | All Samples | Training | Testing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | 280 | 224 | 56 |

| Bearing Fault | 280 | 0 | 280 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).