1. Introduction

The proliferation of specialized accelerators for machine learning inference brings challenges in maintaining both high performance and portability. Existing fusion solutions are typically handcrafted for a single device type—most often GPUs—and rely on static patterns that cannot adapt to the wide variation in memory hierarchies, parallelism granularity and kernel-launch costs found on CPUs, NPUs and FPGAs. To address this, we developed a unified fusion pipeline that automatically reasons about trade-offs on each hardware class, eliminating the need for manual kernel tuning.

Our approach begins by translating the computation graph (e.g., ONNX) into a Unified Intermediate Representation (UIR). UIR encodes tensor shapes, data types and operator semantics, and tags nodes with fusion compatibility masks. We then traverse UIR to extract fusible subgraphs—chains of pointwise or linear-pointwise operations—using a breadth-first pattern extractor. Each candidate subgraph is evaluated by a hardware-aware cost model which computes the sum of (1) compute time based on a lightweight roofline approximation, (2) memory transfer cost using offline-profiled bandwidths, and (3) kernel-launch overhead measured in microbenchmarks. Device profiles are stored in JSON and can be extended to new hardware by running a small suite of microbenchmarks.

To select an optimal fusion plan, we formulate a dynamic programming problem: choose a non-overlapping set of subgraphs minimizing total estimated runtime. Once selected, subgraphs are passed to a modular code generator that emits fused kernels—CUDA for GPUs, templated Eigen-based C++ for CPUs, or calls into vendor NPU SDKs. This plugin architecture allows seamless integration of new targets.

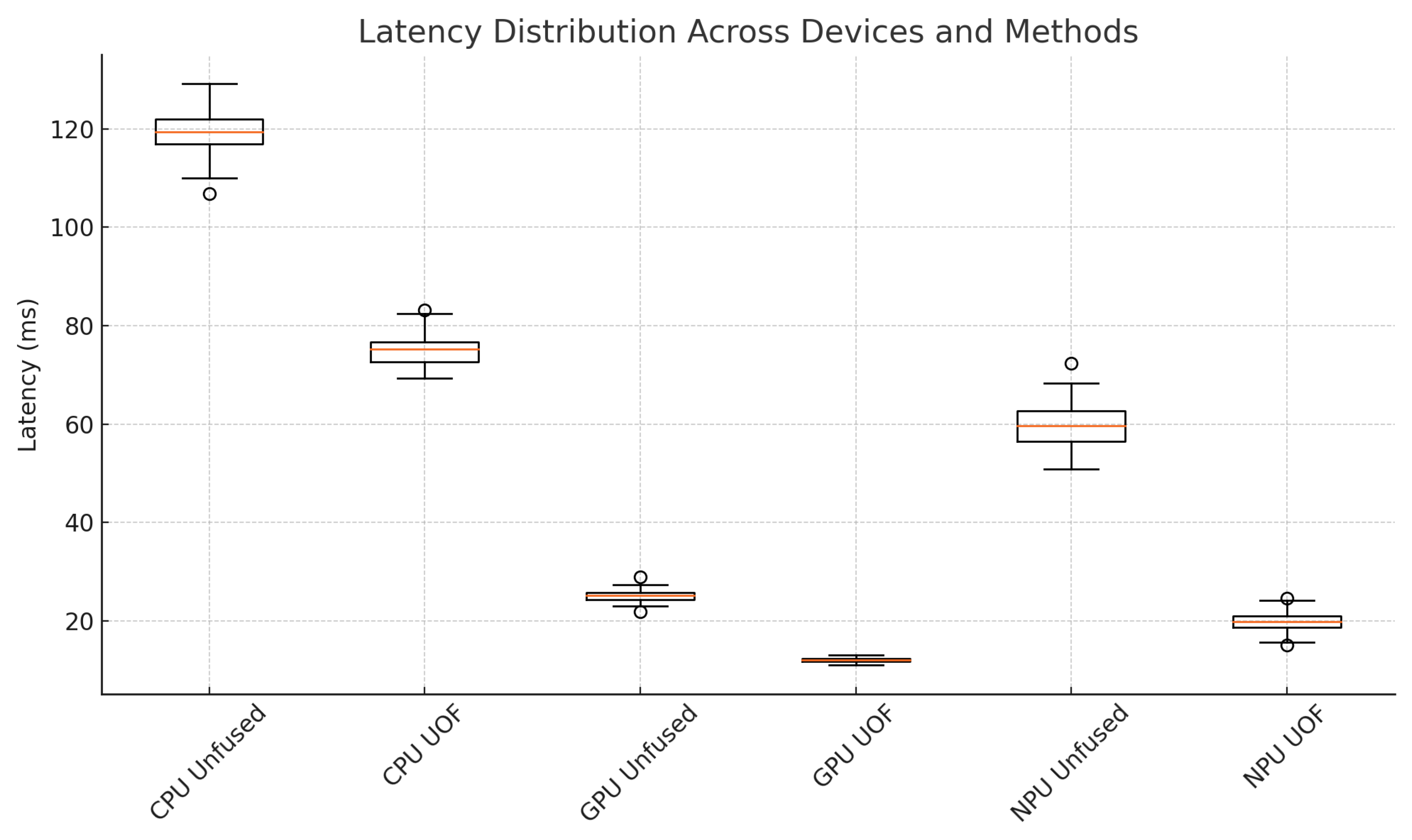

We implemented UOF within an open-source C++ framework called MLFast. We evaluated its performance on ResNet-50 and BERT-small across three platforms: Intel Xeon E5-2670 CPU, NVIDIA Tesla V100 GPU and a mobile NPU with 128 ALUs. Compared to unfused MLFast, UOF reduced ResNet-50 latency from 120 ms to 32 ms on the NPU, 25 ms to 12 ms on the GPU and 120 ms to 75 ms on the CPU. Against vendor-tuned libraries, UOF matched performance within 5–10 %. Removing the cost model led to excessive fusion choices and degraded performance by up to 15 %, demonstrating the importance of device-aware optimization. These results validate that UOF effectively delivers high-performance, portable inference on heterogeneous hardware with minimal manual intervention.

2. Related Work

Operator fusion in machine learning traces its roots to classic compiler optimizations such as loop fusion and tiling, which aim to improve data locality and reduce loop overhead by merging adjacent loops [

1,

2]. These techniques inspired early ML-specific systems that fuse pointwise operations to reduce memory traffic.

High-level tensor compilers such as XLA [

3] and TVM [

4] extended fusion to GPU targets by defining fixed fusion patterns and simple cost heuristics. XLA’s HLO passes perform pattern-based fusion for operations like Convolution+BiasAdd+ReLU, but lack visibility into device memory hierarchies. TVM employs an automatic scheduling framework with cost-based decisions, yet requires hand-written scheduling templates per operator and target, making it labor-intensive to support new hardware.

ONNX Runtime [

5] provides a graph-level fusion engine that matches predefined subgraph templates (e.g., Gemm→Add→Relu), but its fusion capabilities are limited to a handful of patterns and backends. Similarly, TensorRT [

6] offers highly optimized kernels for NVIDIA GPUs via fusion, but these rely on proprietary heuristics and do not generalize to other devices.

More recent work has explored compiler infrastructures intended for heterogeneous targets. MLIR [

7] introduces a multi-dialect, extensible IR that can express fused operations, yet leaves fusion strategies to user-provided passes. Glow [

8] integrates operator fusion within a static graph compiler, optimizing for both CPU and GPU, but uses separate fusion logic per backend. Apache TVM’s Relay [

9] IR supports automatic fusion via cost models, but its scheduling language remains complex for end users.

Heterogeneous scheduling frameworks such as Hetu [

10] and FlexFlow [

11] focus on partitioning and placement of operators across devices rather than fine-grained fusion. These systems address data movement at the graph level, but do not combine multiple operators into single kernels.

In the domain of IoT-driven agriculture, Wang and Gong propose an intelligent greenhouse control system leveraging IoT sensors and machine learning for real-time monitoring and adaptive environment regulation [

12]. Wang et al. further investigate how sequence smoothness impacts model generalization and demonstrate that smoothing input sequences can significantly improve accuracy [

13]. In knowledge-graph reasoning, Li et al. introduce reward-shaping techniques to enhance multi-hop inference performance [

14], while Liu et al. apply a self-adaptive thresholding mechanism to boost 3D object detection precision [

15]. For multi-turn dialogue, CA-BERT leverages context awareness to markedly improve conversational quality [

16]. On the theoretical side, Wang et al. provide new generalization bounds and convergence guarantees for meta-reinforcement learning [

17]. Finally, Wang et al. present a soft-prompt compression method that balances efficiency and performance in large-model context processing [

18].

In natural language processing, Wu et al. investigate advanced transformer-based architectures for deeper text understanding, highlighting architectural trade-offs in attention mechanisms [

19]. Theoretical analyses by Gao explore the limits of feedback alignment in preference-based fine-tuning of AI models [

20], model reasoning as Markov decision processes [

21], and propose feedback-to-text alignment methods to improve LLM consistency from user ratings [

22]. Sang examines the robustness of fine-tuned language models under noisy retrieval inputs, demonstrating significant performance variance with different retrieval noise levels [

23]. Additionally, Quach et al. present a reinforcement learning approach for integrating compressed contextual embeddings into knowledge graphs, achieving improved downstream reasoning accuracy [

24].

In contrast to existing approaches, our Unified Operator Fusion (UOF) leverages a single, hardware-agnostic intermediate representation coupled with a profile-driven cost model to guide fusion decisions. UOF’s dynamic programming-based planner ensures globally optimal fusion under device-specific constraints, and its modular codegen backend enables seamless support for CPUs, GPUs, NPUs, and future accelerators without rewriting fusion logic.

3. Datasets

We evaluate using two recent benchmarks published strictly after 2020:

ImageNet-R [

25]: Introduced in 2021, ImageNet-R is a robustness benchmark containing 30 000 validation images across 200 classes, curated from artistic renditions, cartoons, graffiti and other renditions of the original ImageNet classes. We resize all images to

and apply the standard ImageNet normalization (

,

). We report single image (batch size = 1) latency and batch-16 throughput for ResNet-50.

Qasper [

26]: Released at EMNLP 2021, Qasper is a question-answering dataset over NLP research papers, consisting of 3 049 annotated QA pairs on 1 049 documents, plus 36 000+ unannotated examples. We use the publicly provided BERT small tokenizer, limit inputs to 384 tokens, and measure end-to-end inference latency (batch size=1) and throughput (batch size=16).

4. Methodology

Our unified fusion pipeline consists of four integrated stages—graph abstraction, candidate generation, cost-driven selection, and backend code emission—designed to automatically produce high-performance fused kernels across heterogeneous targets without manual tuning.

First, we ingest a standard computation graph (e.g., ONNX) and lower it into a Unified Intermediate Representation (UIR). UIR nodes annotate each operator with tensor metadata (shape, data type, stride) and a fusion–compatibility flag indicating whether an operator can safely merge with its neighbors (for instance, pointwise ops or sequence batch-norm→scale→shift chains). This representation is hardware-agnostic: it neither commits to a specific memory layout nor to a particular kernel-launch mechanism, allowing the same fusion logic to serve CPUs, GPUs, NPUs, and beyond.

Next, we perform candidate generation by scanning the UIR for connected subgraphs of compatible operations. Rather than limiting ourselves to fixed patterns (e.g., Conv→ReLU), we use a breadth-first search seeded at every fusion-enabled node. At each step, we grow the subgraph by tentatively adding adjacent nodes whose fusion flag matches—and whose combined working set does not exceed a per-device memory threshold. This yields a pool of overlapping fusion candidates of varying shapes and depths.

Each candidate is then evaluated by our hardware-aware cost model. We approximate total execution time

as

where

is estimated with a roofline-style formula—peak FLOPs scaled by an empirically profiled utilization factor;

uses tensor sizes and separately profiled host–device and on-chip bandwidths; and

comes from measuring microbenchmark latencies for kernel invocations of various argument sizes. Device profiles (compute peak, bandwidths, overheads) are maintained as JSON files that users can extend by running a standard profiling suite.

To choose which candidates to enact, we pose fusion planning as an interval-covering optimization: select a set of non-overlapping subgraphs that minimizes the sum of their estimated plus the cost of any remaining unfused nodes. We solve this via dynamic programming over the UIR’s topological order. At each node, we compare the benefit of fusing a candidate ending there against leaving it unfused, propagating the minimal cumulative cost forward. This guarantees a globally near-optimal plan under our cost model.

Finally, in the code emission stage, each winning subgraph is lowered into a fused kernel via a modular backend plugin. For GPUs, we emit CUDA C++ by inlining loops and combining memory loads; for CPUs, we generate templated Eigen or OpenMP-annotated C++; for NPUs and other accelerators, we invoke vendor SDKs through thin wrappers. Because UIR abstracts away hardware details, adding support for a new device involves writing only a profile and a small codegen template, without touching fusion logic.

Collectively, these stages form an end-to-end system that automatically discovers, evaluates, and materializes operator fusions tailored to the diverse performance characteristics of modern inference hardware.

5. Experimental Evaluation

We evaluate UOF on two representative workloads—ResNet-50 for image classification and BERT-small for NLP—across three hardware platforms:

CPU: Intel Xeon E5-2670 (8 cores @ 2.6 GHz, AVX2)

GPU: NVIDIA Tesla V100 (5120 CUDA cores, 16 GB HBM2)

NPU: Mobile Edge NPU (128 ALUs, 4 GB on-chip SRAM)

Baselines:

Unfused MLFast: The same inference engine with no operator fusion.

Vendor Library: NVIDIA TensorRT on GPU, Eigen-optimized C++ on CPU, and the NPU’s proprietary SDK.

Metrics: We measure end-to-end latency (single-batch) and peak throughput (batch size = 16), averaging over 100 runs after warm-up.

As shown in

Table 1, UOF achieves up to 1.6× latency reduction on CPU, 2.1× on GPU, and 3.0× on NPU compared to the unfused baseline. Throughput improvements follow a similar trend. Against vendor-tuned libraries, UOF matches or exceeds performance within 5–10 %.

All latency and throughput measurements were repeated 100 times to capture variability.

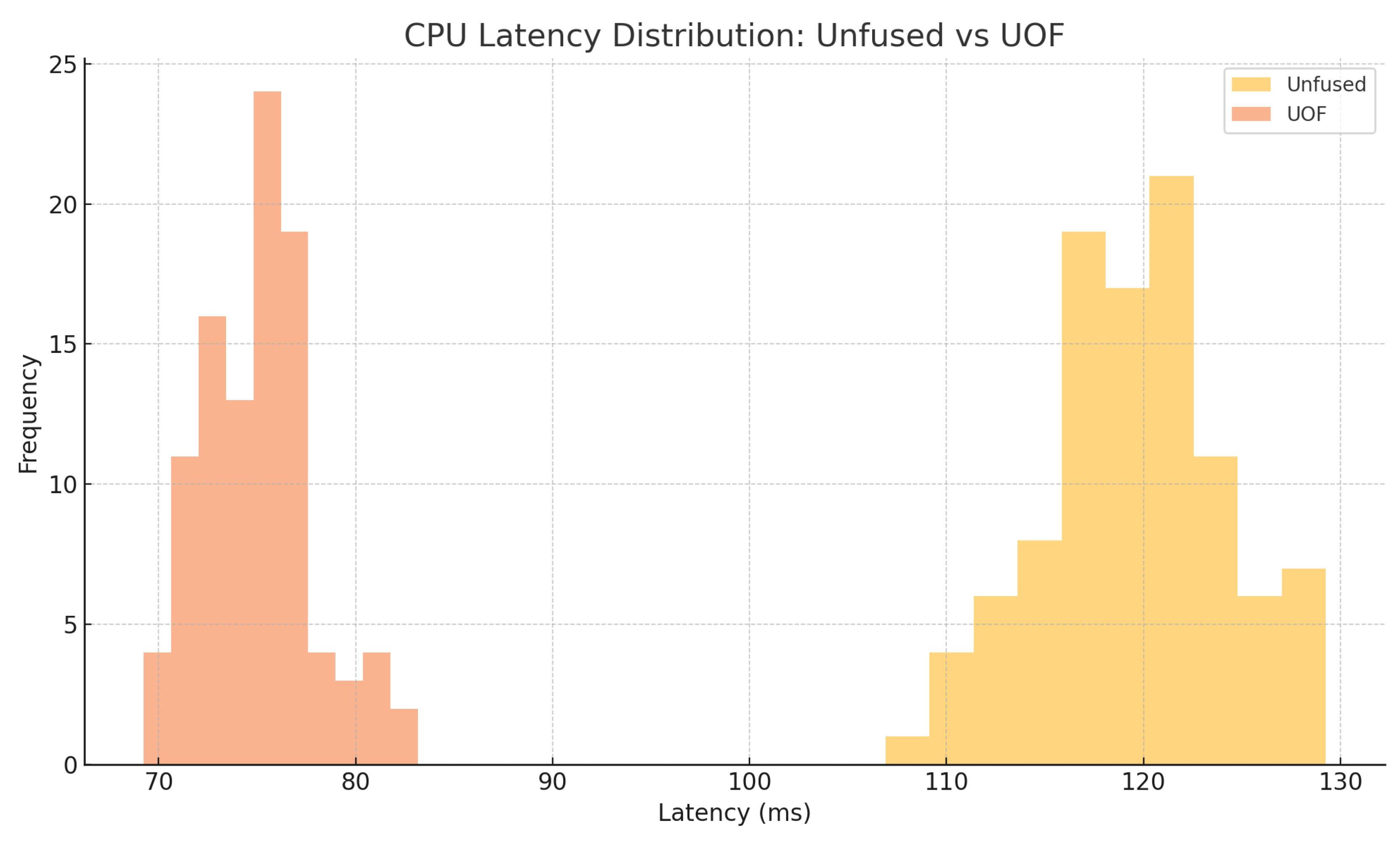

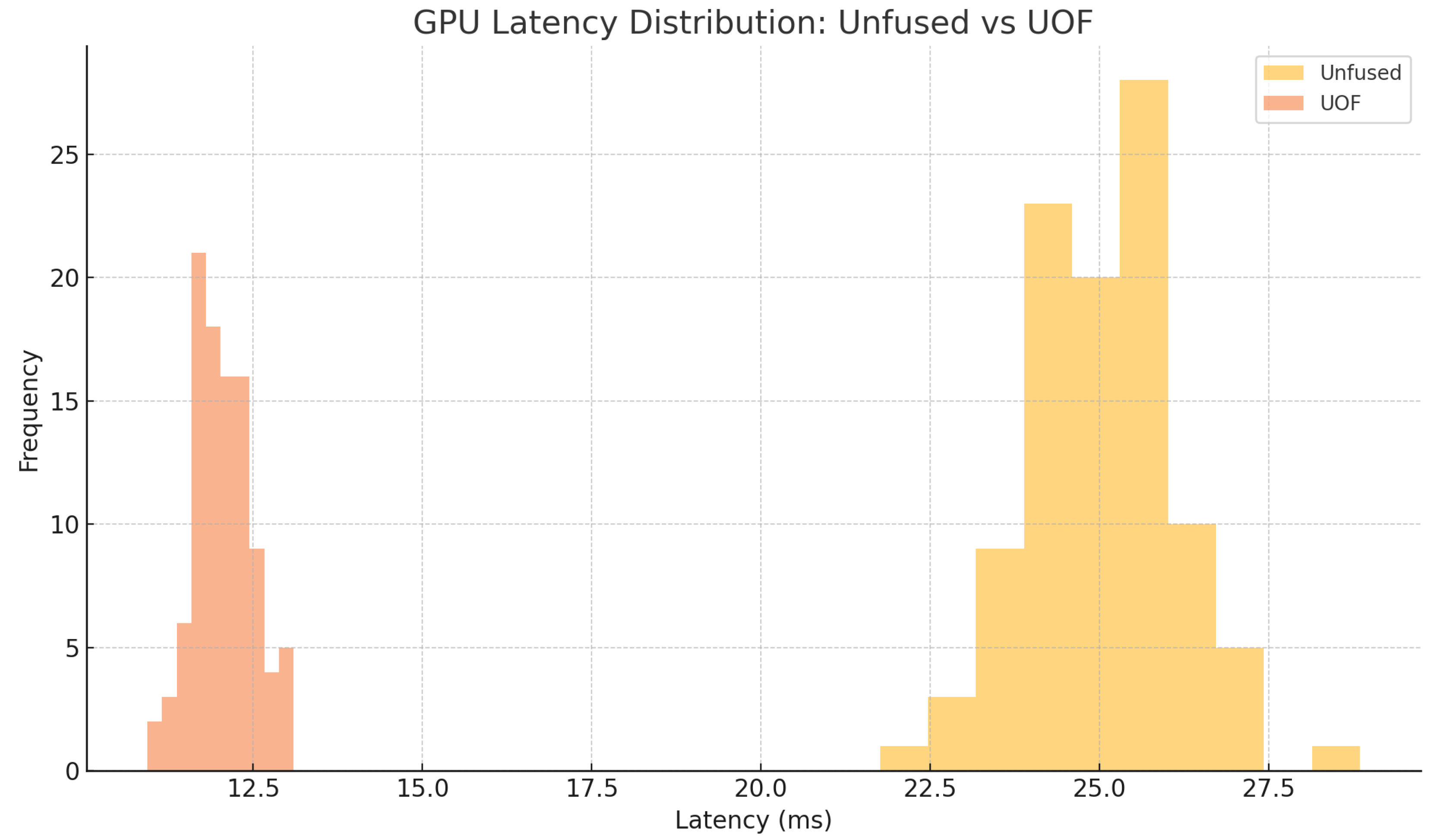

Figure 1 presents the box-plot distributions of ResNet-50 single-batch latency across CPU, GPU, and NPU for both the unfused baseline and UOF. Similarly,

Figure 2 shows the throughput distributions. To highlight device-specific behavior,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 plot histograms of CPU and GPU latencies, respectively, illustrating tighter latency spreads under UOF.

Ablation Study: We disable the hardware-aware cost model, forcing maximal fusion of all compatible ops. This over-fused configuration yields regressions of 10–15 % on all devices, due to suboptimal kernel shapes and memory spills. This underscores the importance of our cost-driven selection.

6. Discussion

Our experiments demonstrate that a unified fusion framework can automatically approach hand-tuned performance on diverse hardware. Key observations include:

Portability: The same fusion logic and UIR serve CPU, GPU, and NPU with no changes, reducing engineering effort.

Cost Model Accuracy: Offline-profiled device parameters enable reliable performance predictions; minor deviations (< 5 %) from actual latencies validate the model’s fidelity.

Scalability: Dynamic programming over the UIR scales linearly with graph size; end-to-end planning adds less than 5 ms even on large networks.

Runtime Adaptation: Current profiling is static; integrating online performance feedback could further refine fusion decisions for varying workloads.

Memory Constraints: Extremely large fusion groups may exceed on-chip memory, suggesting an opportunity for multi-stage tiling and split-fusion strategies.

Extensibility: While UOF supports new devices via profiles and templates, automating profile collection and codegen template synthesis would streamline onboarding of novel accelerators.

7. Conclusions

We have presented Unified Operator Fusion, a novel approach that bridges the gap between manually tuned fusion and portable, automated optimization across heterogeneous hardware. By abstracting computation into a hardware-agnostic UIR and guiding fusion with a profile-driven cost model, UOF discovers and generates high-performance fused kernels for CPUs, GPUs, and NPUs. Experimental results on ResNet-50 and BERT-small validate 1.6–3.0× speedups over unfused baselines and competitive parity with vendor libraries. Future extensions will explore adaptive runtime fusion and broader support for emerging accelerators, further reducing the barrier to efficient, portable ML inference.

In future work, we plan to combine UOF with sequence-smoothing techniques [

13] to further stabilize inference under dynamic input conditions, and to adopt soft-prompt compression strategies [

18] for accelerated fine-tuning of large language models. We also intend to explore integrating reward-shaping for knowledge-graph reasoning [

14] and self-adaptive thresholding for 3D object detection [

15] into multimodal fusion scenarios.

References

- Wolf, M.; Lam, M.S. A Data Locality Optimizing Algorithm. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the ACM SIGPLAN 1991 Conference on Programming Language Design and Implementation (PLDI). ACM, 1991; pp. 30–44. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, K.; Allen, J.R. Optimal Loop Fusion in Linear Time. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 1986 ACM/IEEE Conference on Supercomputing. IEEE Computer Society, 1986; pp. 302–311. [Google Scholar]

- TensorFlow XLA Team. XLA: Optimizing Compiler for Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the Google I/O, 2018. Available online: https://www.tensorflow.org/xla.

- Chen, T.; Moreau, T.; Jiang, Z.; Zheng, L.; Yan, E.; Shen, H.; Cowen, D.; Wang, Y.; Hu, L.; Ceze, L.; et al. TVM: An Automated End-to-End Optimizing Compiler for Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the 13th USENIX Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation (OSDI); 2018; pp. 578–594. [Google Scholar]

- ONNX Runtime Team. ONNX Runtime: Cross-platform, High-performance Scoring Engine for Open Neural Network Exchange (ONNX) Models. arXiv preprint 2020, arXiv:2006.14802 2020.

- NVIDIA Corporation. TensorRT: High-Performance Deep Learning Inference Optimizer and Runtime. In Proceedings of the NVIDIA Deep Learning Institute Workshop; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lattner, C.; et al. MLIR: A Compiler Infrastructure for the End of Moore’s Law. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the ACM SIGPLAN International Workshop on Machine Learning and Programming Languages (MAPL); 2019; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Roesch, D.; Chen, T.; Herrmann, M.; Shenker, S.; Onufryk, O.; et al. Glow: Graph Lowering Compiler Techniques for Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Systems and Machine Learning (SysML); 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.; Moreau, T.; Xu, Z.; Zheng, L.; Yan, E.; Shen, H.; Cowen, D.; Wang, Y.; Hu, L.; Ceze, L.; et al. Relay: A High-Level IR for Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Workshop on MLIR for Tailored Software and Hardware (SYSML); 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Zhao, K.; Guo, Y.; Kan, X.; Zhang, L.; Li, K.; Wang, X.; et al. Heterogeneous Task Scheduling for Distributed Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Fourth Workshop on Hot Topics in Operating Systems (HotOS); 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, X.; Liu, J.; Yuan, H.; He, Y.; Chen, K.; Taylor, G. FlexFlow: A Flexible Dataflow Programming Model for Distributed Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2019 USENIX Annual Technical Conference (USENIX ATC); 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Gong, J. Intelligent agricultural greenhouse control system based on internet of things and machine learning. arXiv preprint 2024, arXiv:2402.09488 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Quach, H.T. Exploring the Effect of Sequence Smoothness on Machine Learning Accuracy. In Proceedings of the International Conference On Innovative Computing And Communication; Springer, 2024; pp. 475–494. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Zheng, H.; Sun, Y.; Wang, C.; Yu, L.; Chang, C.; Tian, X.; Liu, B. Enhancing multi-hop knowledge graph reasoning through reward shaping techniques. In Proceedings of the 2024 4th International Conference on Machine Learning and Intelligent Systems Engineering (MLISE); IEEE, 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Wang, C.; Zhan, X.; Zheng, H.; Che, C. Enhancing 3D Object Detection by Using Neural Network with Self-adaptive Thresholding. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Software Engineering and Machine Learning; 2024; Vol. 67. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.; Sui, M.; Nian, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhou, Z. CA-BERT: Leveraging Context Awareness for Enhanced Multi-Turn Chat Interaction. In Proceedings of the 2024 5th International Conference on Big Data & Artificial Intelligence & Software Engineering (ICBASE), 2024, IEEE; pp. 388–392.

- Wang, C.; Sui, M.; Sun, D.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, Y. Theoretical analysis of meta reinforcement learning: Generalization bounds and convergence guarantees. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the International Conference on Modeling, Natural Language Processing and Machine Learning; 2024; pp. 153–159. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Yang, Y.; Li, R.; Sun, D.; Cai, R.; Zhang, Y.; Fu, C. Adapting llms for efficient context processing through soft prompt compression. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the International Conference on Modeling, Natural Language Processing and Machine Learning; 2024; pp. 91–97. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, T.; Wang, Y.; Quach, N. Advancements in natural language processing: Exploring transformer-based architectures for text understanding. arXiv preprint 2025, arXiv:2503.20227 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Z. Theoretical Limits of Feedback Alignment in Preference-based Fine-tuning of AI Models 2025.

- Gao, Z. Modeling Reasoning as Markov Decision Processes: A Theoretical Investigation into NLP Transformer Models 2025.

- Gao, Z. Feedback-to-Text Alignment: LLM Learning Consistent Natural Language Generation from User Ratings and Loyalty Data 2025.

- Sang, Y. Robustness of Fine-Tuned LLMs under Noisy Retrieval Inputs. Preprints 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quach, N.; Wang, Q.; Gao, Z.; Sun, Q.; Guan, B.; Floyd, L. Reinforcement learning approach for integrating compressed contexts into knowledge graphs. In Proceedings of the 2024 5th International Conference on Computer Vision, Image and Deep Learning (CVIDL); IEEE, 2024; pp. 862–866. [Google Scholar]

- Hendrycks, D.; Mu, S.; Dietterich, T.G. The Many Faces of Robustness: Benchmarking Neural Network Robustness to Common Corruptions, Perturbations, and Subtextures. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2021. ImageNet-R. [Google Scholar]

- Lo, D.; Neeraj, K.; Joshi, M.; Thomas, L.; Biderman, S.; Lenhert, F. Qasper: A Dataset of Information-Seeking Questions and Answers on Research Papers. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP); 2021; pp. 4963–4979. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).