1. Introduction

The Gondwanan mawsoniid coelacanth Axelrodichthys is well-known from the Early Cretaceous (Albian/Aptian) of Brazil (Maisey 1986, 1991; Fragoso et al. 2019), where it was first recognized, and has subsequently been noted from the Early Late Cretaceous of Morocco (provisionally by Cavin et al. 2015), the Late Cretaceous (Santonian/Coniacian) of Madagascar (Gottfried et al. 2004), and the Late Cretaceous (Campanian and Maastrichthian) of southern France (Cavin et al. 2016, 2020), extending the taxon’s distribution from western to eastern Gondwana and into what is now southern Europe. As such the genus has figured in discussions of Cretaceous trans-Gondwanan coelacanth biogeographic patterns and in positing vicariance as a means of explaining those patterns (Carvalho and Maisey 2008, Cavin et al. 2019, Cavin et al. 2020).

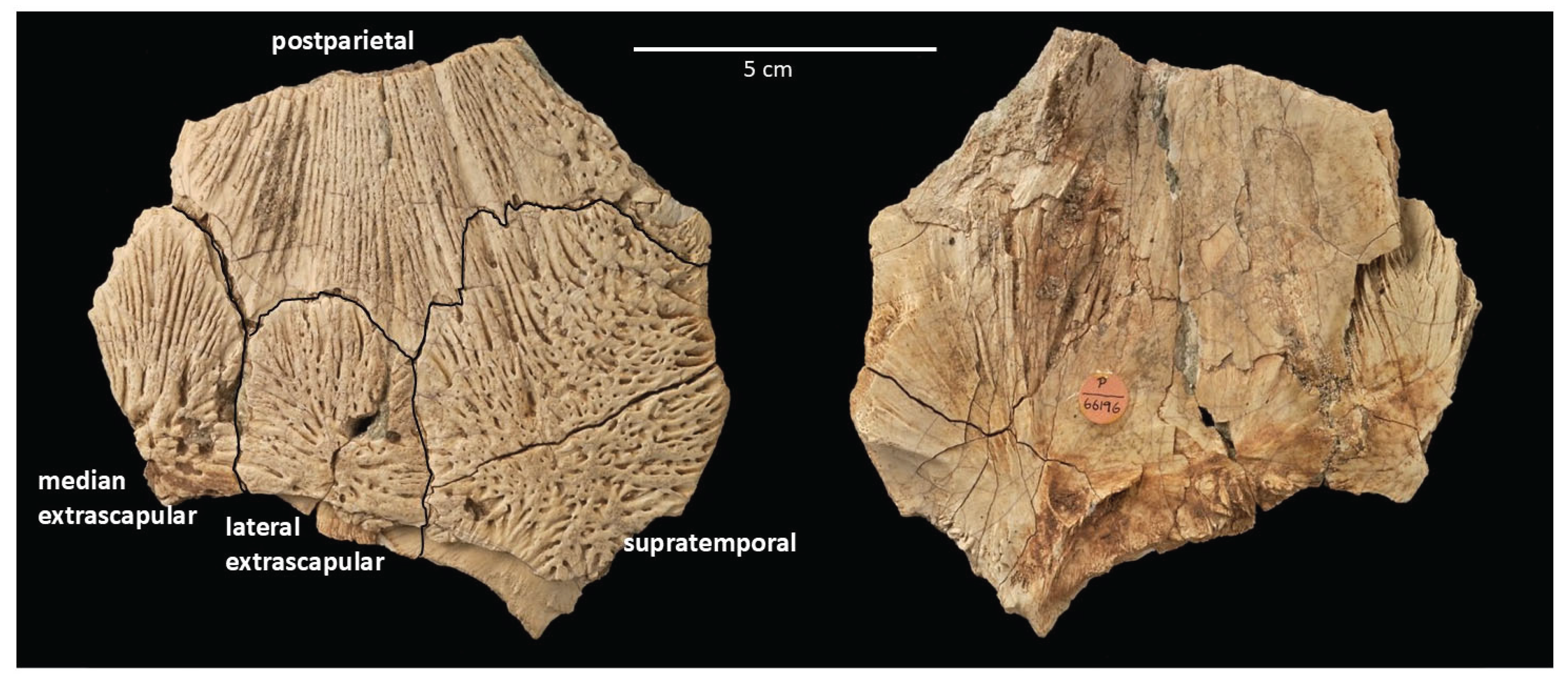

We focus here on a partial coelacanth skull roof and partial extrascapular series from the Early Cretaceous (Aptian) ‘Fish Mountain’ site at Ingal (or Ingall), central western Niger, which is sufficiently diagnostic to be assigned to Axelrodichthys. This record for the taxon, which was briefly mentioned and figured but not described by Gottfried et al. (2004), merits a fuller description in the broader context of the biogeography and temporal and evolutionary history of Cretaceous Gondwanan mawsoniid coelacanths.

2. Materials and Methods

The coelacanth specimen that is the focus of this report was collected at the Early Cretaceous (Aptian) ‘Fish Mountain’ site near Ingal (or Ingall) in central western Niger [~ 16º47′N, 6º56′E] by the 1988 Natural History Museum (London) (NHMUK) Niger Expedition. Gee (1988) summarized the results of this expedition, which recovered camarasaurid sauropod postcrania, carnosaur teeth, aquatic crocodylians, turtles, and fishes including the coelacanth described here as well as toothplates and other fragments of ceratodontid lungfish. The paleoenvironment was described by Gee (1988) as a floodplain deposit sandwiched between braided rivers, with carcasses swept in by floods. The coelacanth specimen is catalogued in the NHMUK collections as P.66196 and consists of a partial posterior skull roof and partial extrascapular series as described below and as mentioned in Gottfried et al. (2004). The specimen was examined using a Leica MZ6 stereo zoom microscope and photographed at the NHMUK Photo Studio.

3. Results

3.1. Systematic Paleontology

Order ACTINISTIA Cope, 1871

Family MAWSONIIDAE Schultze, 1993

Genus AXELRODICHTHYS Maisey, 1986

Axelrodichthys sp.

NHMUK P.66196, right posterolateral portion of the skull roof and partial extrascapular series, including a (partial) postparietal and supratemporal and a lateral extrascapular (all from the right side), and a median extrascapular element (

Figure 1).

3.2. Description

The specimen overall is slightly domed dorsally, with a generally smooth medial surface and very well-preserved ornamentation on the dermal surface of the bones that consists of divergent and in places gently curving sub-parallel raised ridges, some of which bifurcate distally, separated by linear grooves and more rounded pits.

An extensive area of the relatively broad posterior portion of the right postparietal is preserved, contacting the anterolateral margin of the median extrascapular, and the anterior margins of the right lateral extrascapular and right supratemporal. The sutural contact with the supratemporal has a zig-zag pattern nearer the anteromedial corner of the supratemporal. The ornament on the postparietal is more strongly and distinctly linear than on the other preserved elements, with relatively long posteriorly divergent longitudinal ridges interspersed with small pits that are aligned with the ornamentation ridges. Several larger pits and shorter and more irregular ridges contribute to a rougher surface texture on the lateral margin of the postparietal.

The right supratemporal comprises the posterior lateral corner of the skull roof. It is a relatively large roughly quadrangular element that contacts the postparietal anteriorly and the lateral extrascapular medially. The supratemporal ornamentation consists of several relatively broad longitudinal ridges and grooves in the anterior one-third of the bone which grade into shorter and more transversely oriented ridges and grooves and pits on the rest of the element that give this part of the bone a somewhat woven appearance.

The right lateral extrascapular is sandwiched between the supratemporal and median extrascapular and is relatively straight-sided, but more rounded along its convex anterior border where it has a sutural contact with a concavity along the posterior margin of the postparietal. The ornament on this element includes pits and relatively short grooves and ridges that radiate out from the posteromedially positioned ossification center of the bone.

The approximately symmetrical and leaf-shaped median extrascapular on the Niger specimen is very similar in shape to but notably larger than the median extrascapular that was the basis for determining that Axelrodichthys sp. was present in the Late Cretaceous of Madagascar (Gottfried et al. 2004; that specimen was collected from the Santonian/Coniacian Ankazomihaboka beds of northwestern Madagascar). The median extrascapular on NHMUK P.66196 contacts the right lateral extrascapular laterally and the posteromedial margin of the right postparietal. The median extrascapular bears anteriorly divergent ridges and grooves that fan out evenly to the margin of the anterior two-thirds of the bone, and then thicker and more transversely oriented ridges, and a few relatively large pits, on the more posterior part of the bone. The posteromedial corner of the element is not preserved.

The posterior margin of NHMUK P.66196 does not appear to have the strongly pronounced medial extension that was indicated for the Brazilian species Axelrodichthys araripensis by Fragoso et al. (2019), although preservation along the posterior border of the Niger specimen is imperfect. It is also noted that the supratemporal does not appear to extend as far anteriorly along the postparietal as it does on A. araripensis.

Comments on Assignment to Axelrodichthys – The presence of a median extrascapular is integral to assigning the Niger specimen to Axelrodichthys and not to the closely related mawsoniid genus Mawsonia, which has an overall similar pattern of dermal skull bones forming the posterior portion of the skull roof, including an extrascapular series, but lacks an unpaired median extrascapular element (Forey 1998, Gottfried et al. 2004, Fragoso et al. 2019). The specimen from Niger may well represent a new species within Axelrodichthys, as suggested by the dermal ornament and the overall arrangement and proportions of the posterior skull roof and extrascapular elements, but it is here considered inadvisable to erect a new taxon based on one incomplete specimen that precludes detailed comparisons to features on other more complete Axelrodichthys specimens.

4. Discussion

The geographic and temporal pattern of fossil occurrences of Axelrodichthys point to an early Cretaceous origin of the genus in western Gondwana, followed by a late early to early late Cretaceous diversification into eastern Gondwana. This was followed by apparent dispersal further eastward, eventually reaching as far as Madagascar (Gottfried et al. 2004) in the Late Cretaceous (Santonian/Coniacian), and also northward into southern Europe closer to the end of the Cretaceous culminating with the geologically youngest occurrence of Axelrodichthys in the form of A. megadromos from the Campanian and Maastrichthian of southern France (Cavin et al. 2016, 2020). We note here that Cavin et al. (2016) inaccurately stated that the A. megadromos occurrences from France extends the temporal range of Axelrodichthys some 40 million years further forward into the Late Cretaceous than any previous records – in fact the Santonian/Coniacian record from Madagascar (Gottfried et al. 2004) is approximately 5-10 million years older than A. megadromos, as well as being the furthest east recorded occurrence of the genus.

The pattern seen in Axelrodichthys – with closely related species in the same genus occurring in the Cretaceous of both Brazil and North Africa – matches that seen in some other Gondwanan fish taxa, notable among them the Early Cretaceous amiid fish Calamopleurus, which includes the sister-species C. cylindricus from Brazil and C. africanus from Morocco (Forey and Grande 1998). In addition, before Axelrodichthys was recognized to occur in Africa, the sister-taxon to Axelrodichthys within mawsoniid coelacanths – the genus Mawsonia – was found to exhibit a similar pattern, with Early Cretaceous records in both Brazil (M. gigas) and at several sites in North Africa (e.g., M. tegemani, Wenz 1980). This Brazil-Africa pairing of sister taxa has also been noted in other vertebrate groups, including crocodiles and turtles (Buffetaut and Rage 1993). Forey and Grande (1998) invoked vicariance to explain this pattern, given the pre-breakup physical proximity of Brazil in northeastern South America to northwestern Africa in the Early Cretaceous. This has more recently been posited as the Trans-Gondwana biogeographic track (‘Generalized Track 3′ or GT3) in the model developed by Parmera et al. (2017). While vicariance can logically explain the geologically older occurrences of Axelrodichthys in northwestern Africa, which was closely adjacent to Brazil in the Early Cretaceous, it does seem likely that the further spread of the genus, eventually as far east as Madagascar and as far north as southern France, reflects dispersal within and then out of Africa. In this context, the Axelrodichthys specimen from Niger is geographically intermediate between the oldest and youngest eastern Gondwanan records of Axelrodichthys. This dispersal may have been facilitated in its later stages by the initial inception of the trans-Saharan epicontinental transgression, which began in the Cenomanian (Reyment 1980) and could have provided, at least in part, the means for mawsoniid coelacanths to become more widely distributed across Africa by the Late Cretaceous.

Funding

Support for the author’s research visits to the NHMUK in London was provided by travel funds from the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences at Michigan State University.

Acknowledgments

The late Peter Forey first brought the specimen described here to the author’s attention and graciously shared his comprehensive knowledge of coelacanths. Access to and loan of the specimen was arranged through the kind assistance of Emma Bernard and Zerina Johanson (NHMUK). Photographs of the specimen were skillfully taken and generously provided by Kevin Webb of the NHMUK Photo Studio, Communications and Marketing Department.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Maisey, J. Coelacanths from the Lower Cretaceous of Brazil. American Museum Novitates 1986 2866:1-30.

- Maisey, J. Santana Fossils: An Illustrated Atlas. T.F.H. Publications, Neptune City, New Jersey, USA. 459 pp. 1991.

- Fragoso, L.; Brito, P.; Yabumoto, Y. Axelrodichthys araripensis Maisey, 1986 revisited. Historical Biology 2019 31(10):1350-1372. [CrossRef]

- Cavin, L.; Boudad, L.; Tong, H.; Lang, E.; Tabouelle, J.; Vullo, R. Taxonomic composition and trophic structure of the continental bony fish assemblage from the Early Late Cretaceous of southeastern Morocco. PLoS One 2015 10(5):e0125786. [CrossRef]

- Gottfried, M.D.; Rogers, R.R.; Curry Rogers, K. First record of Late Cretaceous coelacanrhs from Madagascar. In Recent Advances in the Origin and Early Radiation of Vertebrates; Arratia, G.; Wilson, M.V.H.; Cloutier, R. Eds. 2004 Verlag Dr. Friedrich Pfeil, Munich, Germany, pp. 687-691.

- Cavin, L.; Valentin, X.; Garcia, G. A new mawsoniid coelacanth (Actinistia) from the Upper Cretaceous of southern France. Cretaceous Research 2016 62:65-73.

- Cavin, L.; Buffetaut, E.; Dutour, Y.; Garcia, G.; Le Loeuff, J.; Mechin, A. The last known freshwater coelacanths: new Late Cretaceous mawsoniid remains (Osteichthyes, Actinistia) from southern France. PLoS One 2020 15(6): e0234183. [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, M.S.S.de; Maisey, J. New occurrence of Mawsonia (Sarcopterygii, Actinistia) from the Early Cretaceous of the Sanfranciscana Basin, Minas Gerais, Brazil. In Fishes and the Break-up of Pangea; Cavin, L.; Longbottom, A.; Richter, M. Eds. Geological Society, London, Special Publications 2008 295:109-144.

- Cavin, L.; Cupello, C.; Yabumoto, Y.; Fragoso, L.; Deesri, U.; Brito, P.M. Phylogeny and evolutionary history of mawsoniid coelacanths. Bulletin Kitakyushu Museum of Natural History Series A 2019 17:3-13.

- Gee, H. Cretaceous unity and diversity. Nature 1988 332:487.

- Forey, P.L. History of the coelacanth fishes. Chapman & Hall, London. 419 pp. 1998.

- Forey, P.L.; Grande, L. An African twin to the Brazilian Calamopleurus (Actinopterygii: Amiidae. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 1998 123:179-195.

- Wenz, S. A propos du genre Mawsonia, coelacanthe geant du Cretace Inferieur d’Afrique et du Bresil. Memoires de la Societe Geologique de France 1980 59:187-190.

- Buffetaut, E.; Rage, J.-C. Fossil amphibians and reptiles and the Africa-South America connection. In The Africa-South America Connection; George, W.; Lacovat, R. Eds. 1993. Oxford Press, Clarendon, UK, pp. 87-99.

- Parmera, T.C.C.; Gallo, V.; Da Silva, H.; De Figueiredo, F.J. Distributional patterns of Aptian-Albian paleoichthyofauba of Brazil and Africa based on track analysis. Anais de Academia Basileira de Ciencias 2019 91(supplement 2): e20160456.

- Reyment, R.A. Biogeography of the Saharan Cretaceous and Paleocene epicontinental transgressions. Cretaceous Research 1980 1(4):299-327.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).