1. Introduction

Agricultural transformation in rural areas of Latin America faces structural challenges linked to productive informality, limited value addition, inadequate infrastructure, and weak institutional coordination [

1]. In the department of Meta, Colombia, these limitations are further exacerbated by the absence of participatory governance frameworks, the declining recognition of ancestral knowledge, and the limited capacity to meet the quality and safety standards required in formal markets [

2]. These conditions restrict small producers’ access to marketing opportunities and hinder progress toward several Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), including no poverty (SDG 1), zero hunger (SDG 2), and decent work (SDG 8) [

3,

4]. Farmers’ markets, as territorial direct-marketing strategies, have emerged as effective mechanisms to reduce intermediation, promote the consumption of local foods, and strengthen rural economies [

5]. However, ensuring their long-term sustainability requires informed decision-making processes that integrate economic, social, cultural, and environmental criteria—especially in contexts marked by actor diversity and future uncertainty [

6]. In light of this, the following research question arises: How can strategies for the transformation of agricultural products with quality and safety be prioritized in the department of Meta, considering sustainability and associativity criteria under different future scenarios?

In this context, multi-criteria decision-making (MCDA) methods—such as DEMATEL and ANP—have proven effective for modeling complex relationships between factors and stakeholders in diverse socioeconomic systems [

7,

8,

9]. Nevertheless, few studies have applied these techniques within participatory processes focused on farmers’ markets in Latin America, underscoring the innovative nature of the approach proposed here. Moreover, the inclusion of the Stratified Best–Worst Method (SBWM)—recently used in areas such as the sustainable selection of waste collection technologies under future scenarios [

10]—offers a novel tool to capture variations in decision priorities across plausible conditions.

Integrating SBWM with DEMATEL-ANP enables the development of robust multi-criteria models that are adaptable to political, environmental, and economic uncertainties, thus enhancing their potential to inform strategic decisions in rural contexts.

This article proposes a hybrid model that combines stakeholder mapping, needs analysis, scenario building, and multi-criteria techniques (DEMATEL–ANP–SBWM) to prioritize sustainable strategies for agricultural transformation with a focus on quality and safety in the department of Meta. The proposal is grounded in a participatory and associative approach, tailored to local territorial dynamics. The findings aim to provide actionable insights for both public and community actors to promote food sustainability and rural resilience. Although the prioritized farmers’ market operates in an urban setting, its organizational base—a rural producers’ cooperative—and its territorial anchoring in agricultural areas of Meta justify its analysis within conceptual frameworks of rural governance and agri-food sustainability.

3. Materials and Methods

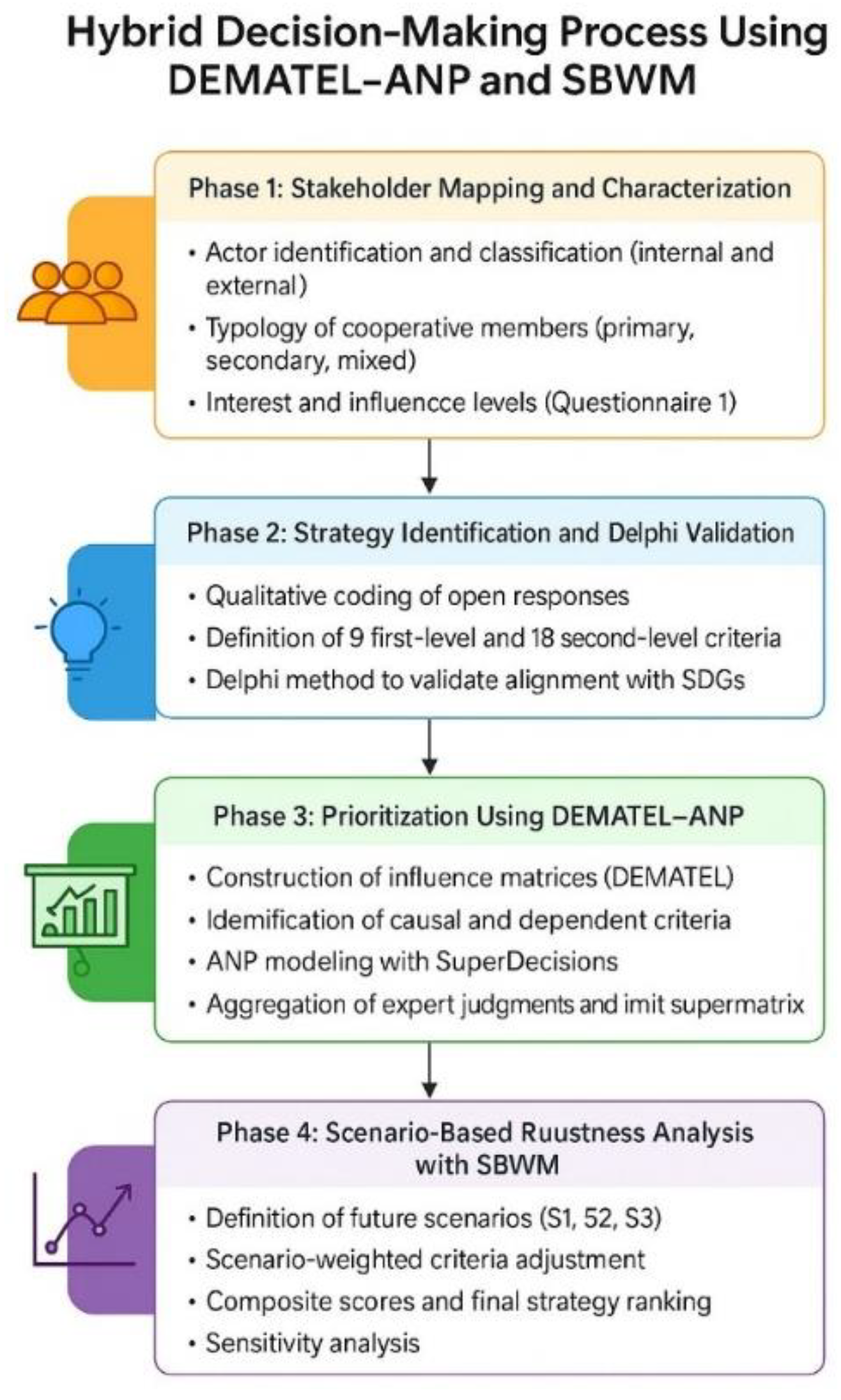

This article adopted a mixed and participatory approach, structured in four methodological phases, described below, aimed at prioritizing strategies for agri-food transformation in the department of Meta (see

Figure 1).

Phase 1. Mapping and characterization of stakeholders linked to the cooperative

In the initial phase of the project, a comprehensive process was undertaken to identify and characterize both internal and external stakeholders involved in the strengthening of farmers’ markets. This mapping was conducted through literature review, semi-structured interviews, and the administration of Questionnaire 1 (see Annex Table A1), which was designed based on stakeholders’ analysis methodologies and adapted to the specific context of the cooperative and its institutional environment. The instrument captured key information regarding levels of interest, influence, and expectations concerning the project’s development, following a participatory approach to stakeholder management [

26]. The sample consisted of the 26 active cooperative members, considered the strategic core of the research, and was complemented by 15 external stakeholders: unaffiliated producers (40%), local market vendors (27%), public officials involved in rural development programs (20%), and regular consumers (13%). This integration of diverse perspectives enhanced the legitimacy of the process, broadened the understanding of the local agri-food system, and guided the identification of strategies from a participatory, multilevel governance perspective. The collected data were systematized to produce an stakeholder’s map, identify key relationships, and define the strategic group that would participate in the following phases—thus ensuring representation aligned with the dynamics of the local agri-food system [

27,

28].

During this first phase, organizational, territorial and functional variables of the internal members were also determined. The cooperative members were classified according to their type of production into three main categories: primary producers (44%), secondary producers (44%) and mixed producers (11%). This typology allowed for the establishment of significant differences in terms of geographic location, levels of commercial coordination, and participation strategies. Regarding the positions held within the governance structure, 59% of the stakeholders served exclusively as cooperative members, 15% were members of the Board of Directors, 15% were inactive members, 7% were members of the Supervisory Board, and 4% served as Legal Representative.

Phase 2: Identification and validation of transformation strategies

The second phase focused on identifying and grouping transformation strategies based on the proposals collected through the questionnaires administered to the various stakeholder groups. Open-ended responses were coded using an inductive approach—that is, through direct analysis of participants’ written narratives, without relying on predefined categories. The procedure involved manually reviewing each response, grouping expressions with similar meanings, and constructing categories that reflected recurring patterns in the discourse. This systematization enabled the organization of the information into five strategic dimensions: associativity, marketing, institutional strengthening, quality production, and territorial development. Based on this structure, nine first-level criteria and eighteen second-level criteria were defined and organized according to the overarching goal of strengthening associative and agro-industrial processes in rural territories (see

Table 1).

Based on the results of Questionnaire 1

, nine strategic alternatives were also defined that summarize the main proposals put forward by the social stakeholders consulted. These strategies emerged from a qualitative analysis of the open-ended responses, which expressed needs, expectations, and possible courses of action. The codification process allowed these proposals to be organized into strategic lines that encompass actions in infrastructure, partnerships, marketing, training, communication, and food sustainability

. Table 2 presents these strategies:

Subsequently, in order to validate the formulated criteria and establish their link with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG), an adapted Delphi technique was used, taking as a methodological basis the proposal of [

29]. This technique was applied to a group of nine experts, who evaluated the relationship of each criterion with the SDGs using a dichotomous matrix (“Related” / “Not related”). A consensus threshold of 75% was defined, which was reached in the first round, so no additional rounds were necessary. This methodology allowed for the consolidation of a selection of criteria aligned with both territorial priorities and international sustainability frameworks. The selection of the nine experts was based on their knowledge of the local context and their active participation in processes to strengthen the organizational, commercial, and territorial structure of farmers’ markets. The panel was formed according to criteria of functional diversity, experience in associative processes and track record in strategic planning spaces, following the methodological recommendations for Delphi studies [

30]. The group was made up of cooperative members, technical staff from public entities, and representatives of allied organizations.

The selection of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) responds to the identification of structural problems and opportunities for transformation in the rural context of the Meta department, particularly in strengthening farmers’ markets and associative dynamics. First, SDG 1 (No Poverty) is included, as it recognizes that agricultural activity represents a direct path to improving income and reducing poverty in rural populations, especially when supported by organizational structures such as cooperatives. Studies have shown that participation in community agriculture and local markets can generate significant impacts in overcoming rural structural poverty through sustainable employment and income [

31]. SDG 2 (Zero Hunger) is also selected due to the central role of agroecological production and food sovereignty in strengthening local food security. Strategies such as “from seed to plate” workshops contribute to diversifying the diet, improving access to healthy foods and promoting sustainable production practices [

32]. In direct connection, SDG 3 (Health and well-being) is included due to the focus on food quality and safety, as well as the promotion of fresh and chemical-free foods that benefit both producers and consumers, improving nutrition and reducing health risks [

33,

34].

SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth) relates to efforts to improve transformation infrastructure, create local employment, and strengthen the territorial economic fabric through farmers associations. These dynamics allow for more inclusive and sustained growth [

35], with the potential for agricultural cooperatives to generate decent employment and reduce structural inequalities. In this sense, SDG 10 (Reduction of inequalities) is also considered, due to the inclusion of traditionally marginalized groups, such as small producers, women and rural inhabitants, promoting their participation in decision-making processes and collective economic strengthening [

36]. Furthermore, SDG 9 (Industry, innovation and infrastructure) is essential due to the interest in developing collection centers, pilot processing plants and adequate technical equipment, which contributes to the technical development and added value in farmers production, as indicated in studies on sustainable agro-industrial development [

37]. SDG 12 (Responsible production and consumption) is aligned with the agroecological and direct marketing practices implemented by the cooperative, which minimize waste, shorten supply chains and encourage more conscious consumption [

32]. SDG 17 (Partnerships for the goals) was included in recognition of the importance of coordinating actions between public, private and social institutions to mobilize resources and knowledge that guarantee the success and sustainability of the proposed strategies, regarding the role of partnerships in the effective implementation of the 2030 Agenda [

38].

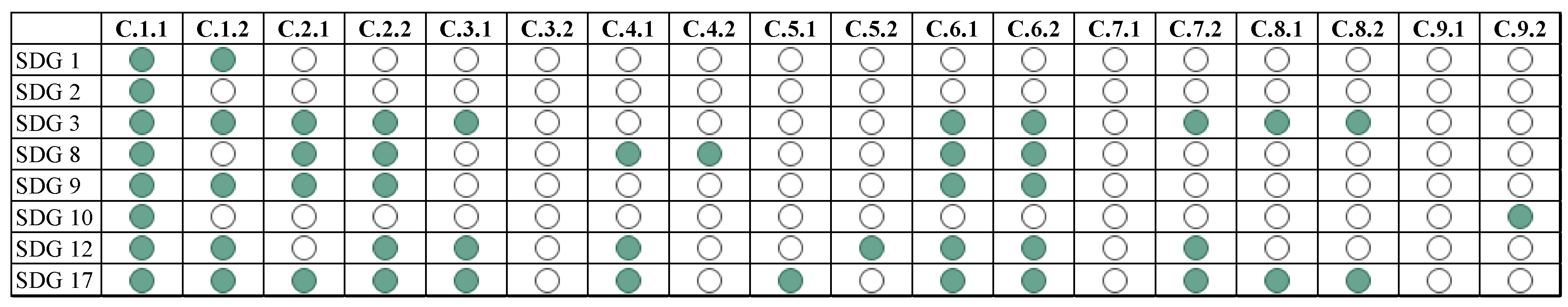

Based on the validation process using the Delphi approach and the correspondence matrix between sub-criteria and Sustainable Development Goals (see

Figure 2), the 18 second-level criteria defined in the previous phase were selected. These criteria were fully incorporated into the ANP-DEMATEL prioritization model, given that they met the established consensus thresholds and reflect both the diversity of strategies and their alignment with the prioritized SDGs.

The selection of the second-level criteria included in the prioritization phase through ANP-DEMATEL was filtered based on the number of relationships validated by consensus with the Sustainable Development Goals. Each point of agreement between a sub-criterion and an SDG was graphically represented in the Delphi matrix, where green dots indicate consensus equal to or greater than 75% among the experts consulted. Since the 18 second-level criteria obtained at least one validation with some priority SDG, it was considered methodologically appropriate to include them in the multicriteria model. This selection criterion ensures consistency between territorial priorities for strengthening farmers’ markets and international sustainability frameworks, and allows for strategies to be evaluated from a comprehensive and contextualized perspective.

Phase 3: Strategy selection through ANP-DEMATEL integration

In this phase, an integrated ANP-DEMATEL approach was implemented to prioritize strategies, considering both the causal structure and the interdependencies between criteria. Questionnaire 2 was used as a data collection instrument, which allowed experts’ assessments to be captured using a scale from 0 (no influence) to 5 (very high influence). Initially, the DEMATEL method was applied to represent the network of cause-effect relationships between the strategic criteria. Based on the experts’ assessments, a matrix of direct relationships was constructed, the normalized version of which gave rise to the total influence matrix. This allowed the identification of driving factors (cause) and dependent factors (effect), establishing the network structure for the next step. On this basis, the

Analytic Network Process (ANP) method was used to model the interdependencies. Pairwise comparison matrices between criteria and strategies were constructed and processed in SuperDecisions software version 3.2.0. The ANP-DEMATEL integration combined DEMATEL’s exploratory capabilities with ANP’s own interconnected network modeling, as documented in previous studies [

9,

29,

39].

As a result, direct influence matrices were generated for each expert.

Table 3 shows the matrix prepared by one of them, where the relationships between second-level criteria (C.1 to C.9) and strategies (E) are assessed. It clearly identifies the factors that have the greatest impact.

The influence matrices were subsequently generated for each expert.

Table 3 shows the matrix prepared by one of them, where the relationships between second-level criteria (C.1 to C.9) and strategies (E) are assessed. It clearly identifies the factors that have the greatest impact.

In order to ensure comparability between experts, this matrix was normalized, obtaining proportional values between 0 and 1. In addition, the relationships between the second-level criteria (e.g., C.1.1, C.1.2) and the first-level criteria were structured using weights obtained from the ANP matrices.

Table 4 shows a representative section of this weighting, focusing on criteria C.1 to C.5.

The weighted matrix was raised to successive powers, as recommended in the ANP methodology, until a stable or convergent supermatrix, called the limit matrix, was reached. In this boundary matrix, all elements reflect the cumulative influence of each second-level criterion on the others within the network, thus capturing both direct and indirect influences (

Table 5).

The 8 iterations progressively redistribute influences among the system elements, so that reciprocal dependencies and feedbacks are fully integrated. When converging, the limit matrix contains stable values that can be interpreted as the overall weights of each node (subcriteria or strategies) within the system. This allows for a robust ranking of available strategies based on their structural connectivity, that is, the degree of influence they exert and receive within the entire strategic system. The complete matrix is in the annex (

Table A3).

Phase 4. Evaluating strategic robustness under future scenarios with SBWM

Once the hierarchy of strategies was established using the ANP-DEMATEL model, the fourth phase focused on evaluating the robustness of these priorities against plausible future scenarios. For this purpose, the Stratified Best–Worst Method (SBWM) was used, an extension of the Best–Worst method that allows uncertainty to be incorporated by simulating different prospective contexts. In this phase we worked with the same 9 experts from phase 3 plus two more.

The SBWM approach combines the logic of comparing extreme criteria (best and worst) with a stratified analysis scheme, which assigns specific weights to decision criteria according to the future context. This article defined three plausible scenarios, considering the difficulties of operating the farmers’ market in urban areas. The three scenarios (S1, S2 and S3) were built from an inductive analysis based on empirical evidence and contextual literature on urban farmers’ markets in Latin America and Colombia, considering scenario planning approaches and territorial analysis [

40,

41] that recommend building contrasting scenarios:

(S1) Continuity without additional institutional support: the farmers’ market operates with logistical limitations and without formal state support, facing space restrictions, low visibility and conflicts over urban land use.

(S2) Institutional support and favorable local regulation: the local government provides incentives and facilitates infrastructure for the establishment of the market, integrating it into urban food supply strategies and recognizing it as a fundamental actor in the solidarity economy.

(S3) Pressure from urban reorganization and eviction: the market faces the threat of displacement or elimination due to urban renewal policies, real estate expansion, or regulations that restrict its presence in central public spaces.

In each scenario, the 9 experts above, plus 2 experts, identified the “best” and “worst” criteria and completed the corresponding comparison matrices. The generated weight vectors were then integrated by weighting according to the probability of occurrence of each scenario, which allowed estimating the potential impact of contextual change on strategic priorities and building a robust and adaptive ranking of strategies, explicitly incorporating territorial uncertainty [

42].

In each scenario, the experts identified the “best” (B) and “worst” (W) criteria and established the required comparisons. The SBWM model is formalized from the following formulation [

43,

44]:

Determine the set of criteria C={C1,C2,...,CN}.

Select the most important criterion CB and the least important (worst) cW.

Obtain the vector of comparisons of the best with the others: AB=[aB1,aB2,…,aBn].

Get the vector of comparisons of the others with the worst: AW=[a1W,a2W,...,anw].

Calculate the optimal weights

W1,W2,...,WN that minimize the deviation function ξ under the following restrictions, where the difference between the weight of the “best” criterion and its comparison with the others must not exceed the allowed deviation ξ (Equation 1). The difference between the weight of each criterion and its comparison with the “worst” must also be within the limit ξ (Equation 2). The sum of all weights must be 1, and no weight can be negative (Equation 3).

Repeat this procedure for each scenario Sk, generating a set of weight vectors w(k).

Consistency evaluation of comparisons: For each scenario, the consistency ratio (ES) was calculated, defined as the quotient between the minimum optimal deviation (ξ*) obtained in the model and the tabulated consistency index (ICₙ), corresponding to the magnitude of the comparison between the best and worst criteria and to the consistency index table (Equation 4). An ES value < 0.2 indicates an acceptable level of consistency in comparisons, allowing the reliability of expert judgments to be validated [

43].

Weighted inter-scenario aggregation: Once the consistency of the weight vectors

w(k) in each scenario was verified, a final aggregate vector w* was calculated, weighting each scenario by its probability of occurrence pₖ. This stratified aggregation allows prioritization to be consolidated considering contextual uncertainty (Equation 5).

It is convenient to clarify that the weighted aggregation expression w∗=∑k=1pk⋅w(k) must be complemented with a subsequent normalization in case the sum of the aggregated vectors is not 1.

- 8.

Final prioritization of strategies: Based on the aggregated vector w*, a final ranking of strategies was established. This ranking reflects the robustness of each alternative in different future scenarios. To do this, the optimal weights for each criterion are multiplied by the corresponding values in the normalized decision matrix, which allows for obtaining the aggregate scores for each strategy and ranking them based on their overall performance.

- 9.

Sensitivity analysis: A sensitivity analysis is performed to assess the stability of the strategy ranking derived from the SBWM model in the face of variations in critical system parameters, i.e., specific thresholds in parameter variation beyond which a significant change in the ranking of prioritized strategies occurs.

4. Results

The results presented in

Table 6 correspond to the overall weightings obtained for the second-level criteria (C.1.1 to C.9.2), from the aggregation of the individual judgments of the experts with ANP-DEMATEL. Each expert built their own decision model, expressing the relationships of influence between the criteria through individual matrices. This matrix was processed using the Aggregation of Individual Judgments (AIJ) approach, through which the geometric means of the normalized priorities were calculated [

45]. The obtained weights constitute the limit matrix of the ANP model and reflect the relative importance of each criterion within the decision network. This resulting hierarchy is used as a basis for analysis in the subsequent phase of the SBWM model, where the robustness of the strategies under different forward-looking scenarios is assessed. Thus, the second-level criteria not only structure the ANP-DEMATEL model, but also allow for the projection of its strategic priorities based on uncertain future contexts.

Based on the results of the ANP-DEMATEL model, a baseline scenario or current scenario (OS) was established. This scenario serves as a benchmark for assessing the stability and consistency of strategic priorities in alternative future contexts. For this purpose, the (SBWM) was applied in three prospective scenarios (S1, S2 and S3). In this way, the robustness of the initially established weights was analyzed, comparing how the assignment of optimal weights varies when environmental conditions change.

Table 7 presents the results obtained for the first prospective scenario (S1), where coincidentally, like ANP-DEMATEL, (C.6.1) was identified as the “best” criterion and (C.8.2) as the “worst”. From the comparisons provided by the experts, the optimal

weights were calculated. The constraint columns show the absolute deviations according to the model equations. The value of ξ 0.0658 reflects the coherence of the system under this scenario. The process is repeated for scenarios S2 and S3.

The consistency of the comparisons made in scenario S1 was assessed using the ES ratio. In this case, a comparison was established between the best criterion (C.6.1) and the worst criterion (C.8.2) was 9, then

. This value is below the acceptability threshold (ES < 0.2), indicating that the comparisons made by the experts were consistent and the derived weights are reliable for strategic analysis (

Table 8).

Once the consistency of the weight vectors

w(k) was verified in each of the scenarios, a final aggregate vector

w* was calculated. Future scenarios were weighted based on expert judgments. At this stage, participants were asked about the probability of each of the proposed scenarios occurring. The experts assigned relative values of occurrence: 0.3% for S1 (Continuity without institutional support), 0.4% for S2 (Institutional support) and 0.3% for S3 (Pressure for urban reorganization). The weighted aggregation of the vectors of each scenario was performed, and w* was normalized (

Table 9).

To prioritize the strategies, another questionnaire was then administered to the experts, asking them to identify the best and worst strategies for each criterion evaluated. Subsequently, the BWM technique was implemented again for each scenario considered. The resulting matrix (

Table 10) was multiplied by the optimal weight matrix of the criteria (

Table 9), in order to obtain the aggregate score for each strategy.

As a result, the strategies previously prioritized with ANP-DEMATEL are presented, and those calculated with SBWM (

Table 11).

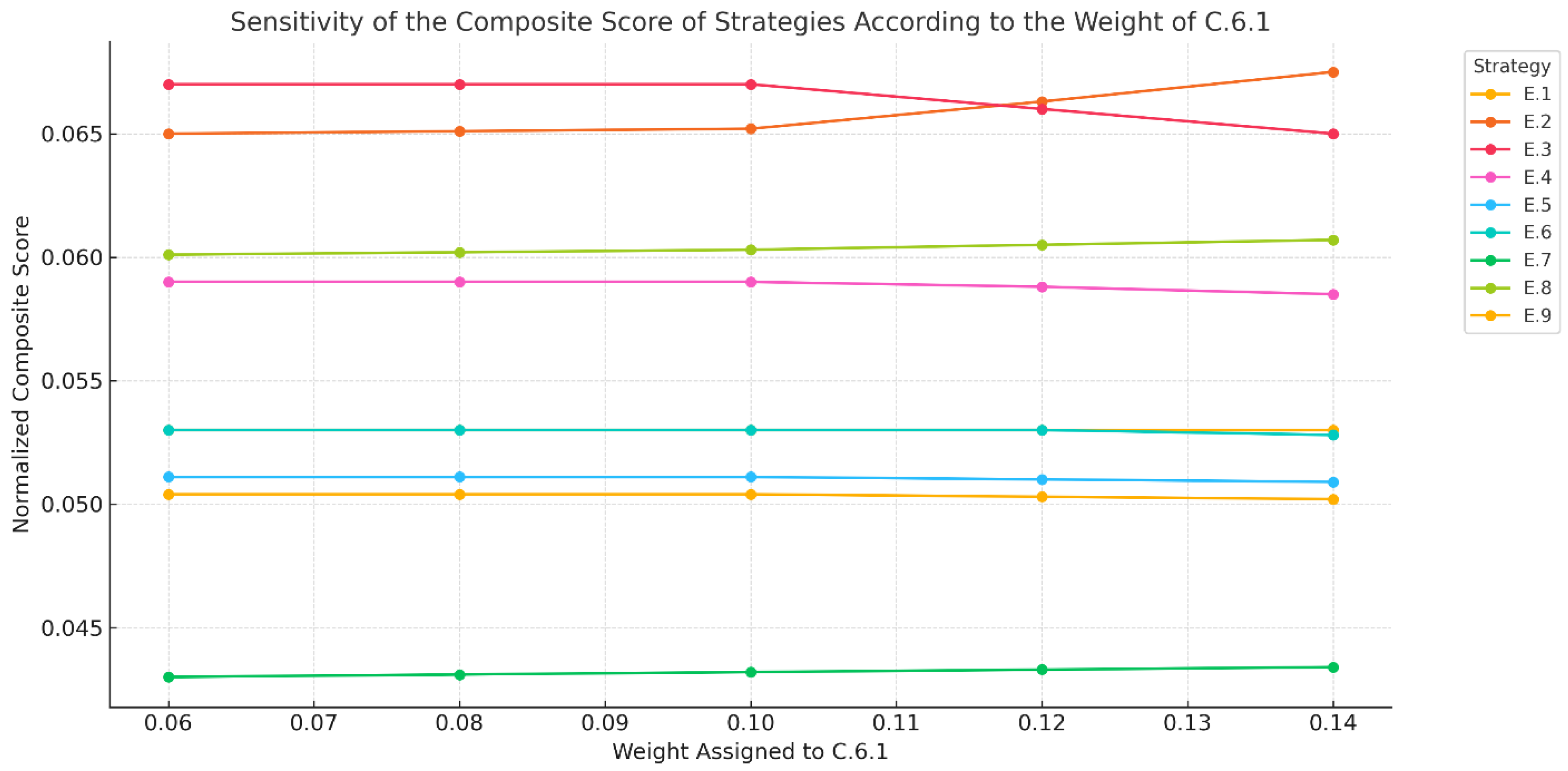

In the ANP-DEMATEL model, the highest-rated strategies were E.2 (infrastructure development) with a weight of 0.1299, followed by E.6 (preparation of ancestral foods) with 0.1278, and E.3 (working tables) with 0.1237. In contrast, in the SBWM model – which incorporates prospective scenarios weighting – E.3 ranked first (0.0669), followed by E.2 (0.0649) and E.8 (participatory workshop “from seed to plate”) with 0.0602. Strategy E.7 (product marketing) ranked last in both models, with weights of 0.0815 and 0.0430, respectively.

To assess the stability of the prioritization model under variations in the criteria, a sensitivity analysis was carried out focusing on criterion C.6.1, which was selected due to its significant weight in the aggregate vector w*. The analysis revealed that strategy E.3 (Working tables) consistently remained in the first position, indicating a high stability of the model in response changes in this criterion. In contrast, strategies E.2 and E.8 revealed variations in their rankings, alternating positions as the weight of the criterion increased. This behavior suggests that their relative priority is partially dependent on the value assigned to local productive transformation. The remaining strategies do not show significant changes in their rankings, which indicates a low sensitivity to the analyzed criterion. Overall, the results confirm the stability of the prioritization structure, although certain specific strategies may vary under scenarios where C.6.1 becomes more relevant (

Figure 2).

5. Discussion

The results obtained from the ANP-DEMATEL and SBWM models reveal significant differences in the prioritization of strategies for strengthening farmers’ markets in the department of Meta. In the structural model (ANP-DEMATEL), physical investment and cultural rescue strategies were prioritized, such as infrastructure development (E.2) and the preparation of ancestral foods (E.6), which reflects a vision focused on the transformation of the productive base. This finding coincides with experiences in countries such as Brazil and Uruguay, where the strengthening of rural agro-industries has allowed for the improvement of value addition and food security in peripheral areas through public policies aimed at modular infrastructure and appropriate technologies [

37,

46]. In contrast, the SBWM model, by incorporating prospective scenarios weighted by experts, provides greater relevance to institutional articulation strategies (E.3: working groups) and participatory training (E.8: from seed to plate). This redistribution suggests that, under conditions of institutional uncertainty or territorial variability, strategies that strengthen organizational capacities and promote collaborative networks acquire greater value. Cases such as Mexico, where sustainable agriculture and local public procurement programs have been accompanied by local governance processes, show similar results [

47,

48].

The sensitivity analysis confirmed the stability of the model against variations in the weight of criterion C.6.1 (pilot transformation plant), maintaining E.3 as the priority strategy. However, E.2 and E.8 swapped positions in some scenarios, demonstrating a moderate sensitivity that can guide flexible implementation decisions. This flexibility is important in rural areas where resources, political will and the regulatory context are highly variable, as is the case in much of Latin America and the Caribbean [

35,

49]. Furthermore, the results reflect that strategies such as E.7 (marketing) and E.5 (quality documents) received a systematically low rating. This could be interpreted as a lack of preconditions for their effective implementation, or a perception that these actions do not generate immediate benefits unless structural limitations such as access to equipment, infrastructure, or technical knowledge are first addressed.

These findings not only guide local investment decisions in farmers’ markets, but also directly align with multiple Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 2 (zero hunger), SDG 8 (decent work), SDG 9 (resilient infrastructure), SDG 12 (responsible consumption and production) and SDG 17 (partnerships for development) [

3,

4]. Prioritizing strategies such as working groups, infrastructure, and participatory workshops strengthens coordination between stakeholders, adds local value, and strengthens community capacities—all key elements in achieving the 2030 Agenda.

From a methodological perspective, the combination of DEMATEL–ANP and SBWM provides depth and adaptability to the multi-criteria decision-making process. While DEMATEL allows capturing causal relationships between criteria, ANP manages hierarchical interdependence, and SBWM adds a scenario-based robustness component. This integration has been validated in recent studies for sustainable agri-food planning [

50,51], although its direct application to farmers’ markets remains scarce, which reinforces the originality of this article. Limitations of the research include the limited sample size of experts, the reliance on qualitative judgments in the construction of comparison matrices, and the lack of empirical validation of the impacts once the strategies were implemented. Future studies could integrate hybrid models that include dynamic criteria such as input prices, access to credit, or climate variability.