Submitted:

21 July 2025

Posted:

23 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

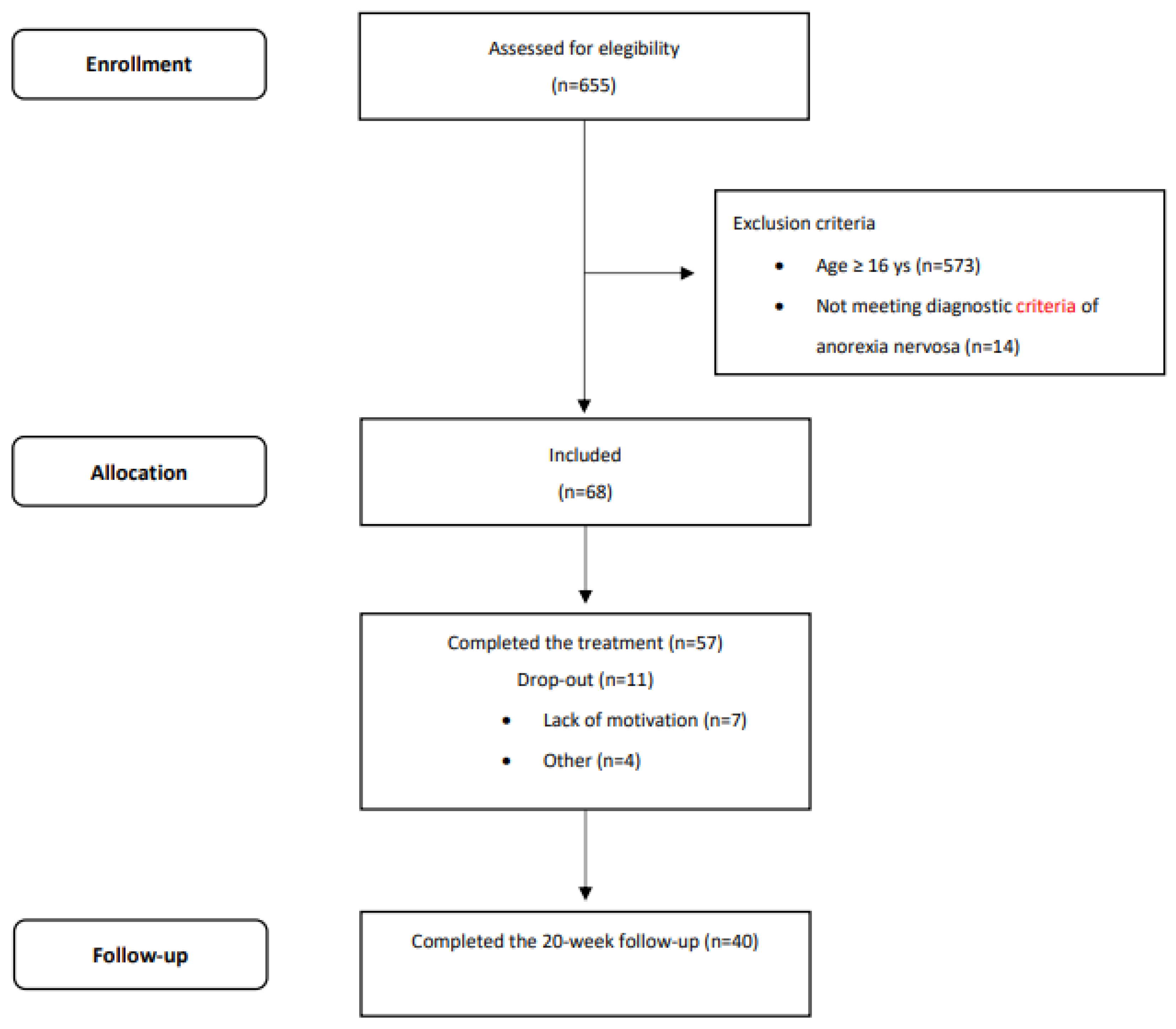

2.2. Participants

2.3. The Treatment

2.4. Assessment

- •

- Demographic and clinical characteristics were collected via interview, including age of onset. Weight and height were measured using calibrated equipment (floor scale and wall-mounted stadiometer) on the first day of admission, with patients wearing only underwear. BMI-for-age percentiles were calculated using CDC growth charts (Kuczmarski et al., 2002) (http://www.cdc.gov/growthcharts/percentile_data_files.html) Percentiles below 1 were recorded as 0.5. Expected body weight (EBW) was calculated using the BMI method (Le Grange et al., 2012).

- •

- Eating disorder psychopathology was assessed using the Italian version of the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q, 6th edition) (Calugi et al., 2017; Fairburn, 2008). The internal consistency in our sample was 0.92.

- •

- General psychopathology was measured using the Italian version of the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) (De Leo et al., 1993; Derogatis, 1992), for which the Cronbach alpha in our sample was 0.97.

- •

- Functional impairment related to eating disorder symptoms was assessed using the Italian version of the Clinical Impairment Assessment (CIA) (Bohn et al., 2008; Calugi et al., 2018), which also demonstrated strong internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.92).

2.5. Outcome Categories

- 1.

- “Good BMI outcome”: Achieving a BMI-for-age percentile equivalent to an adult BMI of ≥18.5 kg/m², representing the lower threshold of a healthy BMI range (Cole et al., 2007; World Health Organization, 2000).

- 2.

- “Full response”: Meeting both the Good BMI Outcome criteria and having a global EDE-Q score below 2.77, which is less than one standard deviation above the community mean (Mond et al., 2006).

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. The Sample

3.2. Intent-to-Treat Findings at EOIT and 20-Week FU

3.3. Predictors of Treatment Outcome

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Accurso, E. C., Ciao, A. C., Fitzsimmons-Craft, E. E., Lock, J. D., & Le Grange, D. (2014). Is weight gain really a catalyst for broader recovery?: The impact of weight gain on psychological symptoms in the treatment of adolescent anorexia nervosa. Behav Res Ther, 56, 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Austin, A., Flynn, M., Richards, K., Hodsoll, J., Duarte, T. A., Robinson, P., Kelly, J., & Schmidt, U. (2021). Duration of untreated eating disorder and relationship to outcomes: A systematic review of the literature. Eur Eat Disord Rev, 29(3), 329-345. [CrossRef]

- Bentz, M., Pedersen, S. H., Moslet, U., Petersen, N., & Pagsberg, A. K. (2025). Predictors of response to family-based treatment for anorexia nervosa in youth: insights from the VIBUS project. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. [CrossRef]

- Berona, J., Richmond, R., & Rienecke, R. D. (2018). Heterogeneous weight restoration trajectories during partial hospitalization treatment for anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord, 51(8), 914-920. [CrossRef]

- Bohn, K., Doll, H. A., Cooper, Z., O'Connor, M., Palmer, R. L., & Fairburn, C. G. (2008). The measurement of impairment due to eating disorder psychopathology. Behav Res Ther, 46(10), 1105-1110. [CrossRef]

- Brown, T. A., Murray, S. B., Anderson, L. K., & Kaye, W. H. (2020). Early predictors of treatment outcome in a partial hospital program for adolescent anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord, 53(9), 1550-1555. [CrossRef]

- Calugi, S., Cattaneo, G., Chimini, M., Dalle Grave, A., Conti, M., & Dalle Grave, R. (2025). Predictors of Intensive Enhanced Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Anorexia Nervosa. Prospective Cohort Study. Int J Eat Disord. [CrossRef]

- Calugi, S., Dalle Grave, A., Chimini, M., Lorusso, A., & Dalle Grave, R. (2024). Illness duration and treatment outcome of intensive cognitive-behavioral therapy in adolescents with anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord, 57(7), 1566-1575. [CrossRef]

- Calugi, S., Dalle Grave, A., Conti, M., Dametti, L., Chimini, M., & Dalle Grave, R. (2023). The Role of Weight Suppression in Intensive Enhanced Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Adolescents with Anorexia Nervosa: A Longitudinal Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 20(4). [CrossRef]

- Calugi, S., Dalle Grave, R., Sartirana, M., & Fairburn, C. G. (2015). Time to restore body weight in adults and adolescents receiving cognitive behaviour therapy for anorexia nervosa. J Eat Disord, 3, 21. [CrossRef]

- Calugi, S., Milanese, C., Sartirana, M., El Ghoch, M., Sartori, F., Geccherle, E., Coppini, A., Franchini, C., & Dalle Grave, R. (2017). The Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire: reliability and validity of the Italian version. Eat Weight Disord, 22(3), 509-514. [CrossRef]

- Calugi, S., Sartirana, M., Milanese, C., El Ghoch, M., Riolfi, F., & Dalle Grave, R. (2018). The clinical impairment assessment questionnaire: validation in Italian patients with eating disorders. Eat Weight Disord, 23(5), 685-694. [CrossRef]

- Cole, T. J., Flegal, K. M., Nicholls, D., & Jackson, A. A. (2007). Body mass index cut offs to define thinness in children and adolescents: international survey. Bmj, 335(7612), 194. [CrossRef]

- Craig, M., Waine, J., Wilson, S., & Waller, G. (2019). Optimizing treatment outcomes in adolescents with eating disorders: The potential role of cognitive behavioral therapy. Int J Eat Disord. [CrossRef]

- Dalle Grave, R., & Calugi, S. (2020). Cognitive Behavior Therapy for Adolescents with Eating Disorders. Guilford Press.

- Dalle Grave, R., Calugi, S., El Ghoch, M., Conti, M., & Fairburn, C. G. (2014). Inpatient cognitive behavior therapy for adolescents with anorexia nervosa: immediate and longer-term effects. Front Psychiatry, 5, 14. [CrossRef]

- Dalle Grave, R., Conti, M., & Calugi, S. (2020). Effectiveness of intensive cognitive behavioral therapy in adolescents and adults with anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord, 53(9), 1428-1438. [CrossRef]

- Dalle Grave, R., Sartirana, M., & Calugi, S. (2019). Enhanced cognitive behavioral therapy for adolescents with anorexia nervosa: Outcomes and predictors of change in a real-world setting. Int J Eat Disord, 52(9), 1042-1046. [CrossRef]

- Dalle Grave, R., Sartirana, M., Dalle Grave, A., & Calugi, S. (2023). Effectiveness of enhanced cognitive behaviour therapy for patients aged 14 to 25: A promising treatment for anorexia nervosa in transition-age youth. Eur Eat Disord Rev. [CrossRef]

- Dancyger, I., Fornari, V., Schneider, M., Fisher, M., Frank, S., Goodman, B., Sison, C., & Wisotsky, W. (2003). Adolescents and eating disorders: an examination of a day treatment program. Eat Weight Disord, 8(3), 242-248. [CrossRef]

- De Leo, D., Frisoni, G. B., Rozzini, R., & Trabucchi, M. (1993). Italian community norms for the Brief Symptom Inventory in the elderly. Br J Clin Psychol, 32 (Pt 2), 209-213.

- Delinsky, S. S., St Germain, S. A., Thomas, J. J., Craigen, K. E., Fagley, W. H., Weigel, T. J., Levendusky, P., & Becker, A. E. (2010). Naturalistic study of course, effectiveness, and predictors of outcome among female adolescents in residential treatment for eating disorders. Eat Weight Disord, 15(3), e127-135. [CrossRef]

- Derogatis, L. R. (1992). The brief symptom inventory (BSI): administration, scoring & procedures manual-II. Clinical Psychometric Research.

- Fairburn, C. G. (2008). Cognitive behavior therapy and eating disorders. Guilford Press.

- Fewell, L. K., Levinson, C. A., & Stark, L. (2017). Depression, worry, and psychosocial functioning predict eating disorder treatment outcomes in a residential and partial hospitalization setting. Eat Weight Disord, 22(2), 291-301. [CrossRef]

- Goddard, E., Hibbs, R., Raenker, S., Salerno, L., Arcelus, J., Boughton, N., Connan, F., Goss, K., Laszlo, B., Morgan, J., Moore, K., Robertson, D., S, S., Schreiber-Kounine, C., Sharma, S., Whitehead, L., Schmidt, U., & Treasure, J. (2013). A multi-centre cohort study of short term outcomes of hospital treatment for anorexia nervosa in the UK. BMC Psychiatry, 13, 287. [CrossRef]

- Gregertsen, E. C., Mandy, W., Kanakam, N., Armstrong, S., & Serpell, L. (2019). Pre-treatment patient characteristics as predictors of drop-out and treatment outcome in individual and family therapy for adolescents and adults with anorexia nervosa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res, 271, 484-501. [CrossRef]

- Grewal, S., Jasper, K., Steinegger, C., Yu, E., & Boachie, A. (2014). Factors associated with successful completion in an adolescent-only day hospital program for eating disorders. Eat Disord, 22(2), 152-162. [CrossRef]

- Hayes, N. A., Welty, L. J., Slesinger, N., & Washburn, J. J. (2019). Moderators of treatment outcomes in a partial hospitalization and intensive outpatient program for eating disorders. Eat Disord, 27(3), 305-320. [CrossRef]

- Homan, K. J., Crowley, S. L., & Rienecke, R. D. (2021). Predictors of improvement in a family-based partial hospitalization/intensive outpatient program for eating disorders. Eat Disord, 29(6), 644-660. [CrossRef]

- Kuczmarski, R. J., Ogden, C. L., Guo, S. S., Grummer-Strawn, L. M., Flegal, K. M., Mei, Z., Wei, R., Curtin, L. R., Roche, A. F., & Johnson, C. L. (2002). 2000 CDC Growth Charts for the United States: methods and development. Vital Health Stat 11(246), 1-190.

- Le Grange, D., Accurso, E. C., Lock, J., Agras, S., & Bryson, S. W. (2014). Early weight gain predicts outcome in two treatments for adolescent anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord, 47(2), 124-129. [CrossRef]

- Le Grange, D., Doyle, P. M., Swanson, S. A., Ludwig, K., Glunz, C., & Kreipe, R. E. (2012). Calculation of expected body weight in adolescents with eating disorders. Pediatrics, 129(2), e438-446. [CrossRef]

- Madden, S., Miskovic-Wheatley, J., Wallis, A., Kohn, M., Hay, P., & Touyz, S. (2015). Early weight gain in family-based treatment predicts greater weight gain and remission at the end of treatment and remission at 12-month follow-up in adolescent anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord, 48(7), 919-922. [CrossRef]

- Martin-Wagar, C. A., Holmes, S., & Bhatnagar, K. A. C. (2019). Predictors of Weight Restoration in a Day-Treatment Program that Supports Family-Based Treatment for Adolescents with Anorexia Nervosa. Eat Disord, 27(4), 400-417. [CrossRef]

- Mond, J. M., Hay, P. J., Rodgers, B., & Owen, C. (2006). Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q): norms for young adult women. Behav Res Ther, 44(1), 53-62. [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Health and Care and Clinical Excellence. (2017). Eating disorders: recognition and treatment | Guidance and guidelines | NICE. Retrieved from https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng69. In.

- Ngo, M., & Isserlin, L. (2014). Body weight as a prognostic factor for day hospital success in adolescents with anorexia nervosa. Eat Disord, 22(1), 62-71. [CrossRef]

- Ornstein, R. M., Lane-Loney, S. E., & Hollenbeak, C. S. (2012). Clinical outcomes of a novel, family-centered partial hospitalization program for young patients with eating disorders. Eat Weight Disord, 17(3), e170-177. [CrossRef]

- Raudenbush, S. W., & Bryk, A. S. (2002). Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods (2nd ed.). Sage.

- Reilly, E. E., Gorrell, S., Duffy, A., Blalock, D. V., Mehler, P., Brandt, H., McClanahan, S., Zucker, K., Lynch, N., Singh, S., Drury, C. R., Le Grange, D., & Rienecke, R. D. (2024). Predictors of treatment outcome in higher levels of care among a large sample of adolescents with heterogeneous eating disorders. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health, 18(1), 131. [CrossRef]

- Rienecke, R. D., & Ebeling, M. (2019). Desired weight and treatment outcome among adolescents in a novel family-based partial hospitalization program. Psychiatry Res, 273, 149-152. [CrossRef]

- Rienecke, R. D., Richmond, R., & Lebow, J. (2016). Therapeutic alliance, expressed emotion, and treatment outcome for anorexia nervosa in a family-based partial hospitalization program. Eat Behav, 22, 124-128. [CrossRef]

- Schlegl, S., Diedrich, A., Neumayr, C., Fumi, M., Naab, S., & Voderholzer, U. (2016). Inpatient Treatment for Adolescents with Anorexia Nervosa: Clinical Significance and Predictors of Treatment Outcome. Eur Eat Disord Rev, 24(3), 214-222. [CrossRef]

- Shek, D. T., & Ma, C. M. (2011). Longitudinal data analyses using linear mixed models in SPSS: concepts, procedures and illustrations. The Scientific World Journal, 11, 42-76. [CrossRef]

- Singer, J. D., & Willett, J. B. (2003). Applied longitudinal data analysis. Oxford Press.

- Solmi, M., Radua, J., Olivola, M., Croce, E., Soardo, L., Salazar de Pablo, G., Il Shin, J., Kirkbride, J. B., Jones, P., Kim, J. H., Kim, J. Y., Carvalho, A. F., Seeman, M. V., Correll, C. U., & Fusar-Poli, P. (2022). Age at onset of mental disorders worldwide: large-scale meta-analysis of 192 epidemiological studies. Mol Psychiatry, 27(1), 281-295. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, M. (2017). Statistical inference in missing data by MCMC and non-MCMC multiple imputation Aagorithms: Assessing the effects of between-imputation iterations. Data Science Journal, 16(37), 1-17. [CrossRef]

- van Hoeken, D., & Hoek, H. W. (2020). Review of the burden of eating disorders: mortality, disability, costs, quality of life, and family burden. Curr Opin Psychiatry, 33(6), 521-527. [CrossRef]

- Van Huysse, J. L., Smith, K., Mammel, K. A., Prohaska, N., & Rienecke, R. D. (2020). Early weight gain predicts treatment response in adolescents with anorexia nervosa enrolled in a family-based partial hospitalization program. Int J Eat Disord, 53(4), 606-610. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (2000). Obesity: Preventing and managing the global epidemic: Report of a WHO consultation. WHO Technical Report Series, 894 (WHO Technical Report Series, Issue.

| Mean and (SE) | Analysis of variance for repeated measures | Linear mixed model | ||||

| Baselinea | EOITb | 20-week FUc | Pairwise Comparisons* | Linear growth | Quadratic growth | |

| BMI-for-age percentile | 5.0 (0.9) | 49.2 (2.3) | 41.2 (7.9) | a<b,c; b>c | β = 167.98 t = 7.90, p < .001 |

β =-149.62, t = 6.43, p < .001 |

| Expected Body Weight | 77.1 (1.2) | 101.8 (1.9) | 99.1 (3.7) | a<b,c; b>c | β = 92.19 t = 20.92, p < .001 |

β =-73.33, t = 17.18, p < .001 |

| Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire | ||||||

| Restraint | 4.1 (0.2) | 0.9 (0.3) | 1.4 (0.5) | a>b,c; b<c | β = -12.40, t = 6.48, p < .001 |

β = 10.96, t = 4.72, p < .001 |

| Eating concern | 3.4 (0.1) | 1.3 (0.1) | 1.2 (0.2) | a>b,c | β = -7.69, t = 9.95, p < .001 |

β = 6.15, t = 5.96, p < .001 |

| Weight concern | 4.0 (0.2) | 2.1 (0.2) | 1.8 (0.2) | a>b,c; b>c | β = -6.83, t = 8.30, p < .001 |

β = 5.02, t = 5.05, p < .001 |

| Shape concern | 4.8 (0.1) | 3.3 (0.2) | 2.9 (0.2) | a>b,c; b>c | β = -4.48, t = 4.94, p < .001 |

β = 2.67, t = 2.46, p = 0.014 |

| Global score | 4.1 (0.1) | 2.1 (0.2) | 1.9 (0.2) | a>b,c | β = -7.85, t = 10.52, p < .001 |

β = 6.20, t = 7.22, p < .001 |

| Brief Symptom Inventory | ||||||

| Global score | 2.1 (0.1) | 1.2 (0.2) | 1.1 (0.5) | a>b,c | β = -3.10, t = 2.85, p = 0.006 |

β = 2.31, t = 1.57, p = 0.140 |

| Clinical Impairment Assessment | ||||||

| Global score | 33.7 (1.3) | 16.4 (1.8) | 15.2 (2.7) | a>b,c | β = -60.27, t = 6.83, p < .001 |

β = 45.68, t = 4.03, p < .001 |

| Dependent variable: drop-out rate | ||||

| Independent variables | β | p-value | OR | 95% CI OR |

| Age | 0.13 | 0.766 | 1.14 | 0.49 − 2.65 |

| Duration of illness | 0.01 | 0.984 | 1.01 | 0.57 − 1.78 |

| BMI-for-age percentile | -0.05 | 0.388 | 0.95 | 0.83 − 1.07 |

| Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE − Q) – global score | 1.34 | 0.086 | 3.81 | 0.83 − 17.54 |

| Brief symptom Inventory (BSI) – global score | -0.48 | 0.578 | 0.62 | 0.11 − 3.41 |

| Clinical Impairment Assessment (CIA) – global score | -0.06 | 0.411 | 0.94 | 0.81 − 1.09 |

| Dependent variable: Good BMI outcome at EOIT | ||||

| Independent variables | β | p-value | OR | 95% CI OR |

| Age | 0.22 | 0.808 | 1.25 | 0.20 − 7.65 |

| Duration of illness | -0.45 | 0.270 | 0.64 | 0.29 − 1.42 |

| BMI-for-age percentile | 12.1 | 0.988 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| EDE − Q – global score | -0.25 | 0.834 | 0.77 | 0.07 − 8.92 |

| BSI – global score | 0.23 | 0.839 | 1.26 | 0.13 − 12.20 |

| CIA – global score | -0.06 | 0.664 | 0.94 | 0.69 − 1.27 |

| Dependent variable: Full response at EOIT | ||||

| Independent variables | β | p-value | OR | 95% CI OR |

| Age | 0.22 | 0.562 | 1.25 | 0.59 – 2.67 |

| Duration of illness | -0.06 | 0.813 | 0.94 | 0.59 − 1.52 |

| BMI-for-age percentile | 0.03 | 0.504 | 1.03 | 0.94 − 1.14 |

| EDE − Q – global score | -0.22 | 0.691 | 0.80 | 0.27 − 2.39 |

| BSI – global score | 0.47 | 0.470 | 1.60 | 0.45 − 5.72 |

| CIA – global score | -0.08 | 0.244 | 0.92 | 0.80 − 1.06 |

| Dependent variable: Good BMI outcome at 20-week FU | ||||

| Independent variables | β | p-value | OR | 95% CI OR |

| Age | -0.03 | 0.951 | 0.97 | 0.33 − 2.85 |

| Duration of illness | 0.04 | 0.903 | 1.04 | 0.56 − 1.93 |

| BMI-for-age percentile | 0.13 | 0.394 | 1.14 | 0.82 − 1.60 |

| EDE − Q – global score | -0.18 | 0.890 | 0.83 | 0.05 − 14.46 |

| BSI – global score | 1.45 | 0.270 | 4.28 | 0.29 − 63.14 |

| CIA – global score | -0.11 | 0.311 | 0.89 | 0.71 − 1.12 |

| Delta BMI-for-age percentile | -0.06 | 0.165 | 0.94 | 0.87 − 1.03 |

| Delta EDE-Q | 0.36 | 0.664 | 1.44 | 0.26 − 7.95 |

| Delta BSI | -1.25 | 0.332 | 0.29 | 0.02 − 4.15 |

| Delta CIA | 0.08 | 0.415 | 1.08 | 0.89 − 1.31 |

| Dependent variable: Full response at 20-week FU | ||||

| Independent variables | β | p-value | OR | 95% CI OR |

| Age | 0.36 | 0.391 | 1.44 | 0.62 – 3.33 |

| Duration of illness | -0.12 | 0.689 | 0.89 | 0.49 − 1.61 |

| BMI-for-age percentile | 0.11 | 0.409 | 1.11 | 0.85 − 1.46 |

| EDE-Q – global score | -0.46 | 0.681 | 0.63 | 0.06 − 6.46 |

| BSI – global score | 1.98 | 0.178 | 7.30 | 0.36 − 148.01 |

| CIA – global score | -0.15 | 0.081 | 0.86 | 0.72 − 1.02 |

| Delta BMI-for-age percentile | -0.03 | 0.338 | 0.96 | 0.89 − 1.04 |

| Delta EDE − Q | 0.34 | 0.722 | 1.40 | 0.19 − 10.127 |

| Delta BSI | -1.79 | 0.093 | 0.17 | 0.02 − 1.37 |

| Delta CIA | 0.14 | 0.155 | 1.15 | 0.94 − 1.40 |

| Dependent variable: BMI-for-age percentile at EOIT | ||||

| Independent variables | β | t | p-value | 95% CI |

| Age | -4.12 | 1.60 | 0.110 | -9.17 − 0.94 |

| Duration of illness | -1.27 | 0.67 | 0.501 | -4.99 − 2.45 |

| BMI-for-age percentile | -0.18 | 0.47 | 0.639 | -0.94 − 0.58 |

| Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q) – global score | 3.12 | 0.81 | 0.425 | -4.72 − 10.96 |

| Brief symptom Inventory (BSI) – global score | 4.47 | 1.01 | 0.312 | -4.22 − 13.17 |

| Clinical Impairment Assessment (CIA) – global score | -0.79 | 1.78 | 0.082 | -1.68 − 0.10 |

| Dependent variable: EDE-Q global score at EOIT | ||||

| Independent variables | β | t | p-value | 95% CI |

| Age | 0.02 | 0.10 | 0.920 | -0.31 − 034 |

| Duration of illness | 0.02 | 0.18 | 0.858 | -0.21 − 0.25 |

| BMI-for-age percentile | -0.02 | 1.07 | 0.287 | -0.07 − 0.02 |

| Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q) – global score | 0.19 | 0.85 | 0.398 | -0.25 − 0.63 |

| Brief symptom Inventory (BSI) – global score | -0.01 | 0.03 | 0.973 | -0.55 − 0.53 |

| Clinical Impairment Assessment (CIA) – global score | 0.02 | 0.58 | 0.561 | -0.04 − 0.07 |

| Dependent variable: BMI-for-age percentile at 20-week FU | ||||

| Independent variables | β | t | p-value | 95% CI |

| Age | 0.93 | 0.10 | 0.917 | -17.58 − 19.43 |

| Duration of illness | -0.89 | 0.15 | 0.880 | -13.13 − 11.34 |

| BMI-for-age percentile | 1.44 | 0.91 | 0.373 | -1.99 − 4.88 |

| EDE-Q – global score | -5.57 | 0.20 | 0.849 | -72.46 − 61.32 |

| BSI – global score | 21.85 | 1.25 | 0.231 | -15.73 − 59.44 |

| CIA – global score | -0.99 | 0.48 | 0.640 | -5.53 − 3.55 |

| Delta BMI-for-age percentile | -0.72 | -1.14 | 0.283 | -2.13 − 0.70 |

| Delta EDE-Q | 7.37 | 0.38 | 0.716 | -37.87 − 52.60 |

| Delta BSI | -18.92 | 0.97 | 0.360 | -64.11 − 26.27 |

| Delta CIA | 0.57 | 0.32 | 0.754 | -3.41 − 4.55 |

| Dependent variable: EDE-Q global score at 20-week FU | ||||

| Independent variables | β | t | p-value | 95% CI |

| Age | -0.38 | 2.07 | 0.039 | -0.75 − -0.02 |

| Duration of illness | 0.12 | 0.80 | 0.427 | -0.17 − 0.41 |

| BMI-for-age percentile | -0.02 | 0.71 | 0.482 | -0.09 − 0.04 |

| EDE-Q – global score | 0.10 | 0.26 | 0.793 | -0.65 − 0.84 |

| BSI – global score | -0.53 | 1.41 | 0.164 | -1.27 − 0.22 |

| CIA – global score | 0.09 | 2.03 | 0.052 | -0.001 − 0.18 |

| Delta BMI-for-age percentile | 0.004 | 0.35 | 0.726 | -0.02 − 0.03 |

| Delta EDE-Q | -0.19 | -0.65 | 0.519 | -0.80 − 0.41 |

| Delta BSI | 0.57 | 1.66 | 0.109 | -0.14 − 1.27 |

| Delta CIA | -0.05 | 1.30 | 0.212 | -0.14 − 0.03 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).