Submitted:

21 July 2025

Posted:

22 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

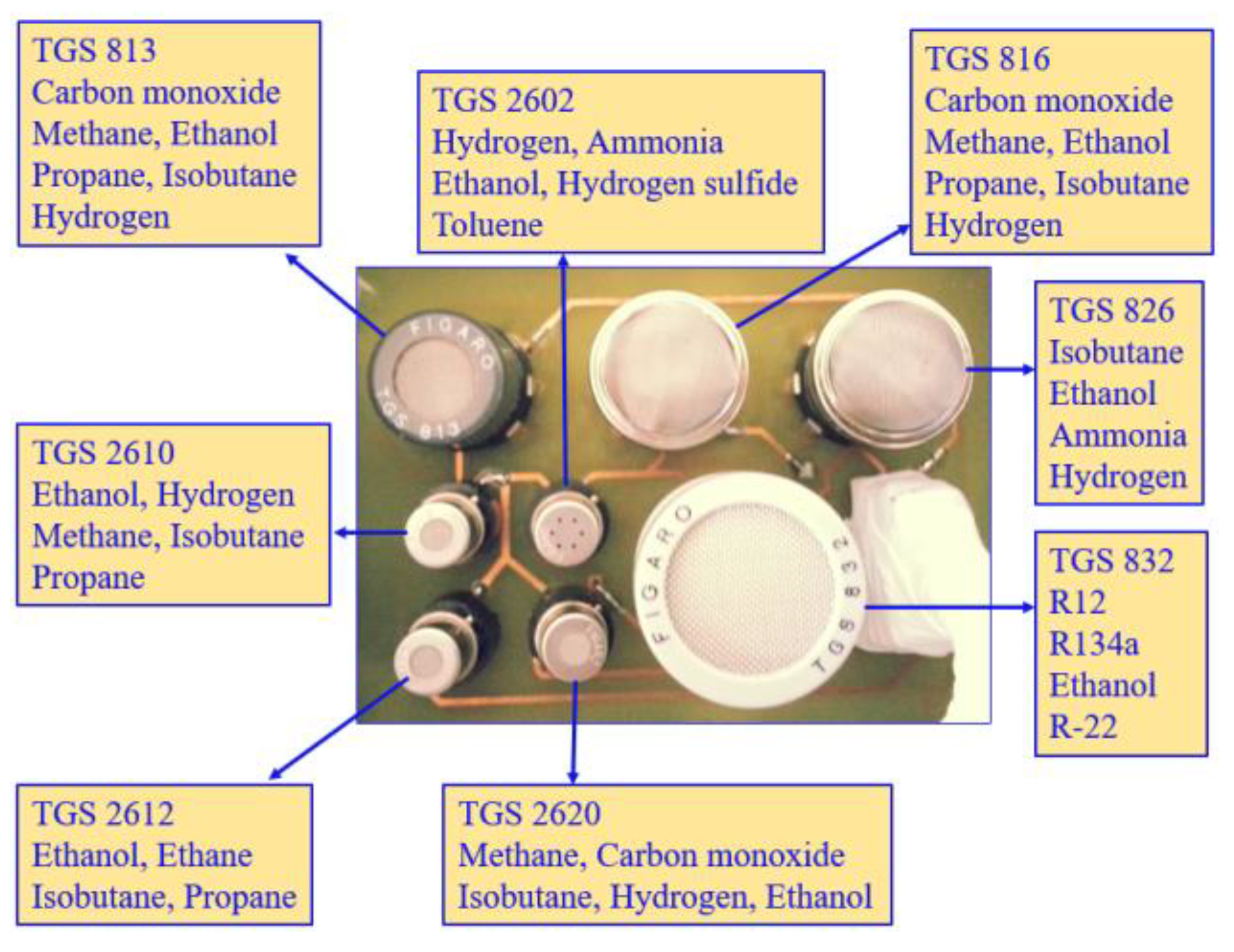

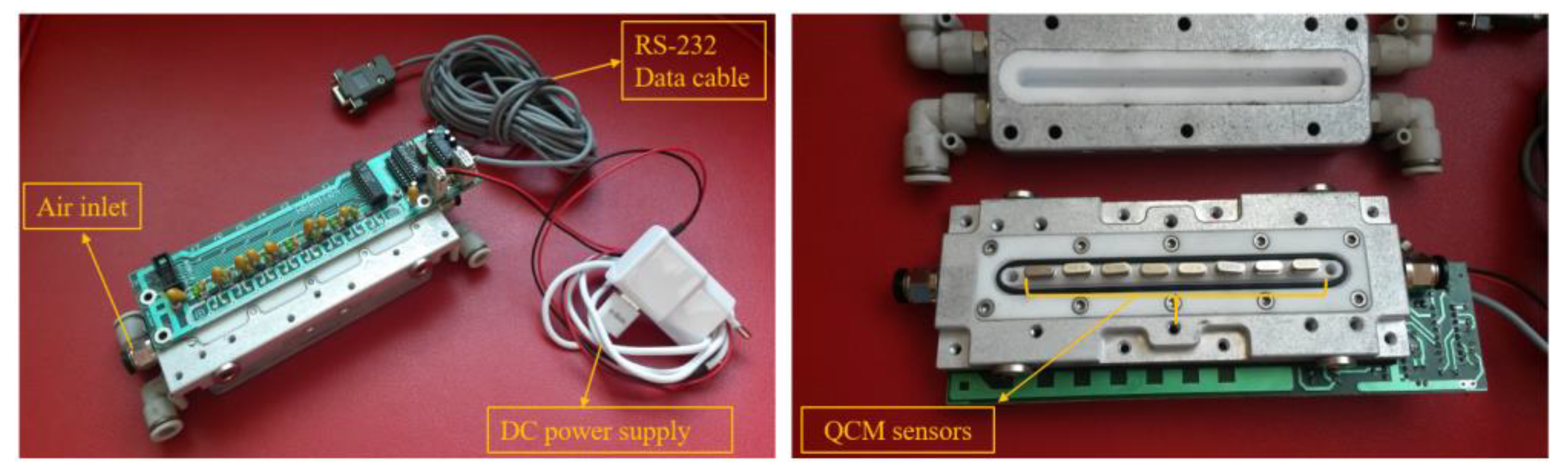

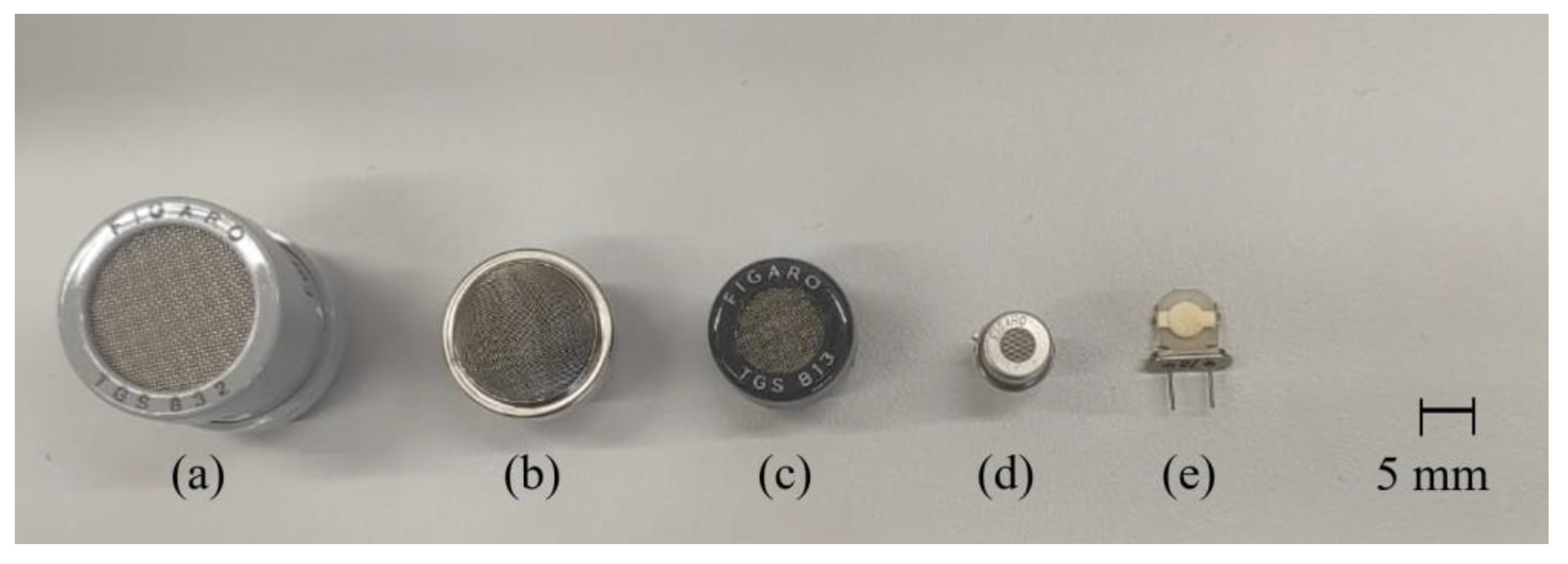

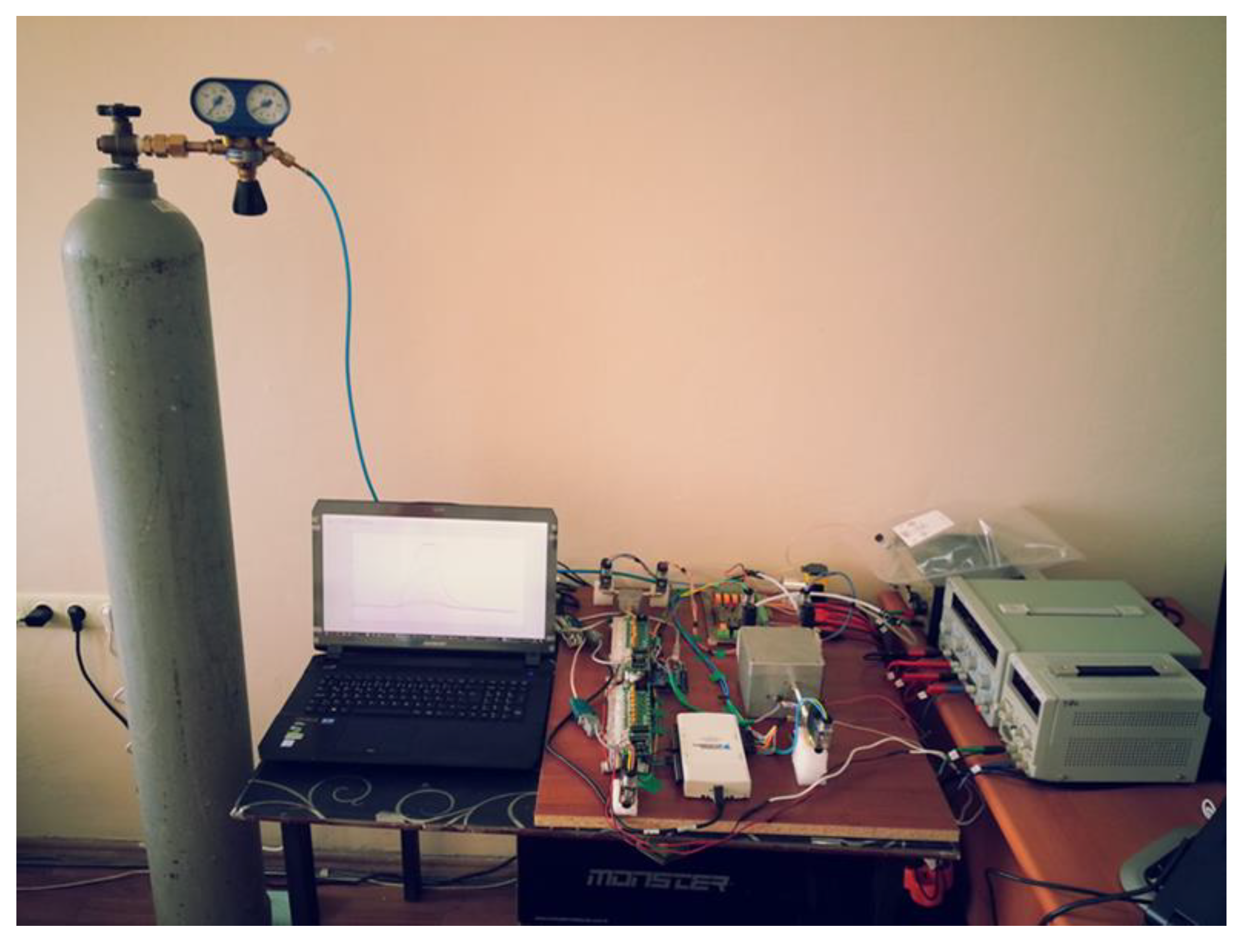

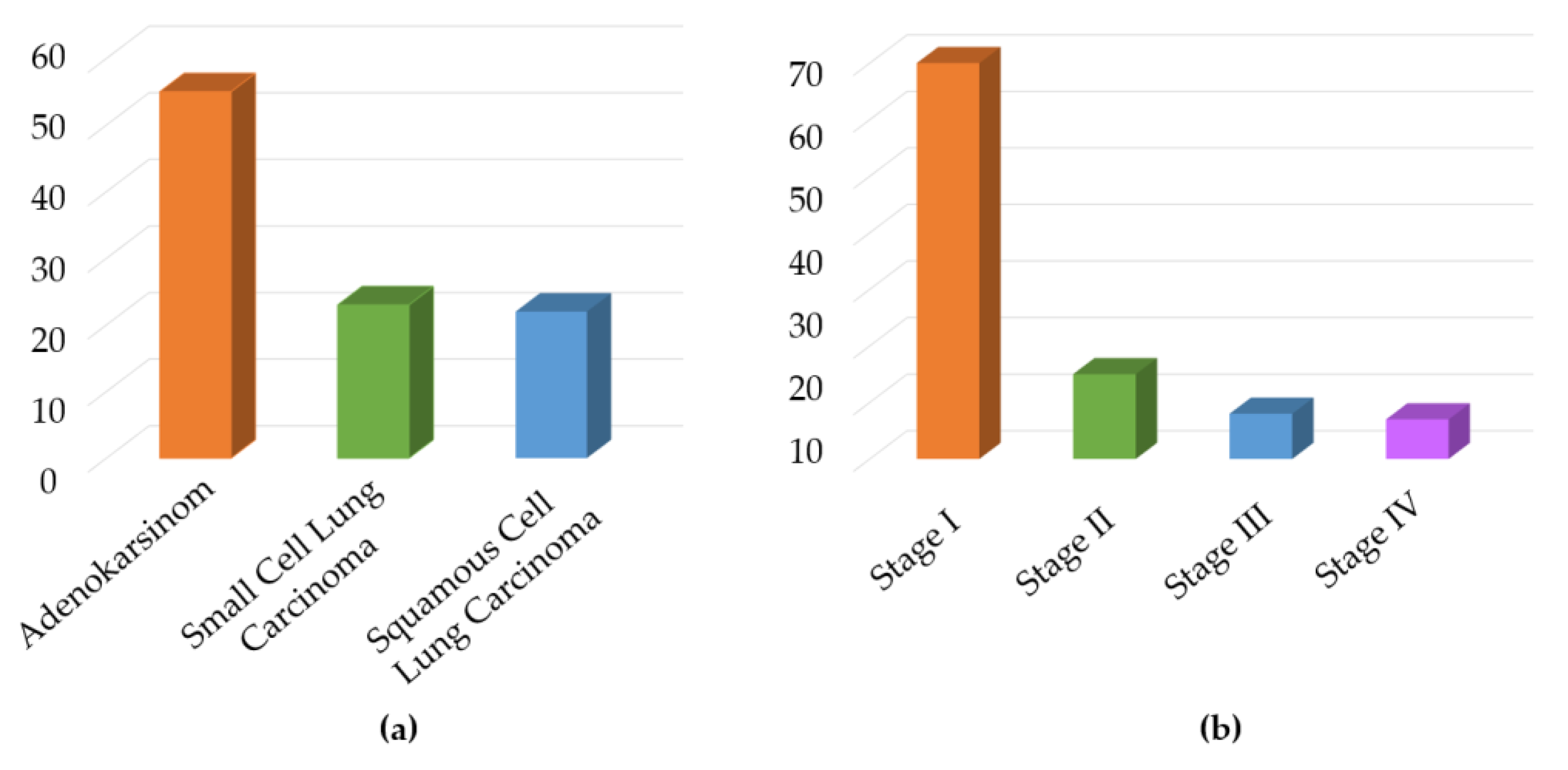

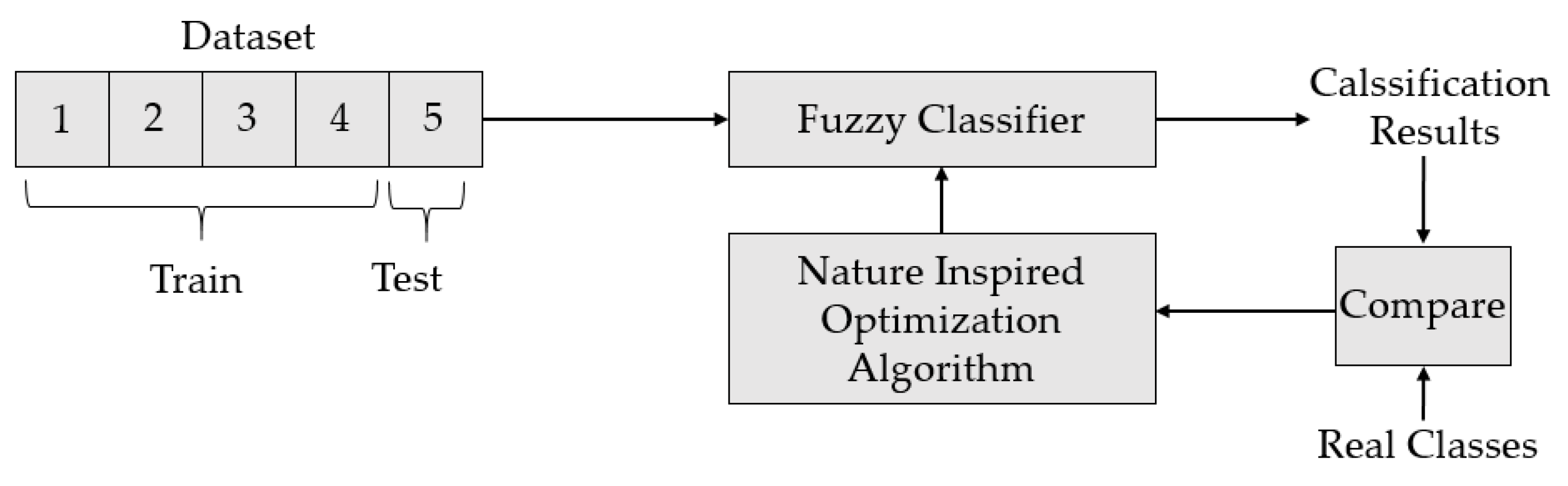

2. Materials and Methods

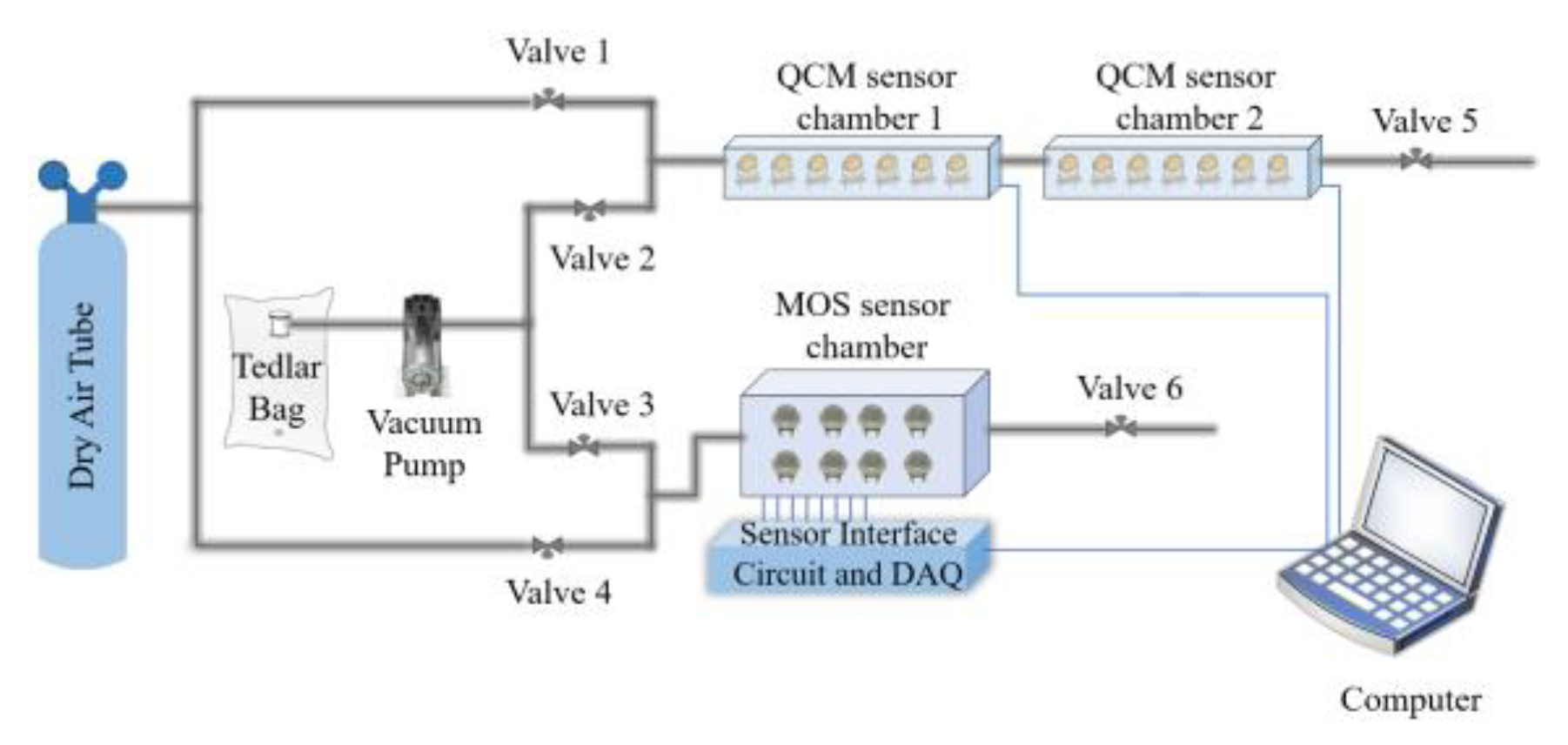

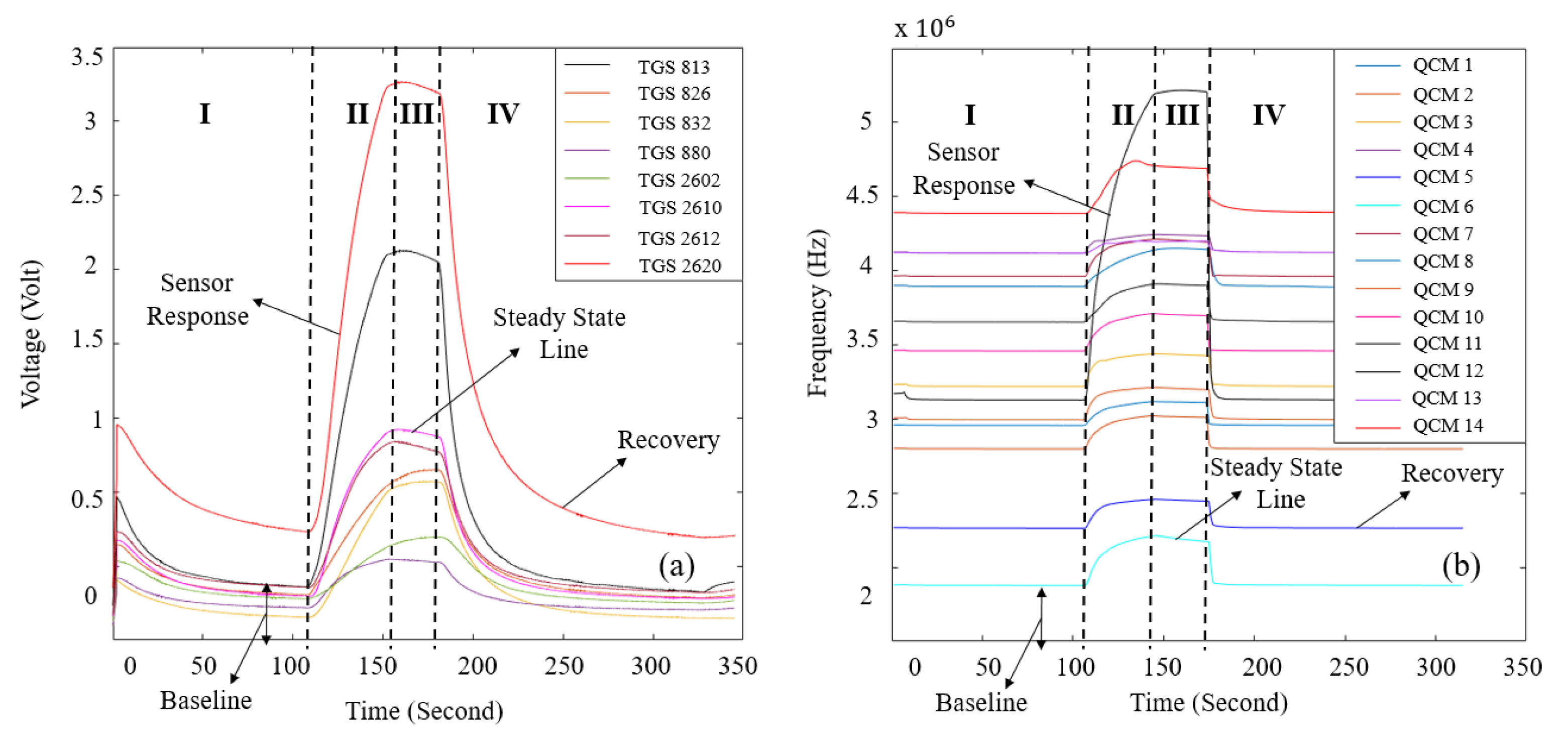

2.1. Experimental Setup

2.2. Collection of Breath Samples

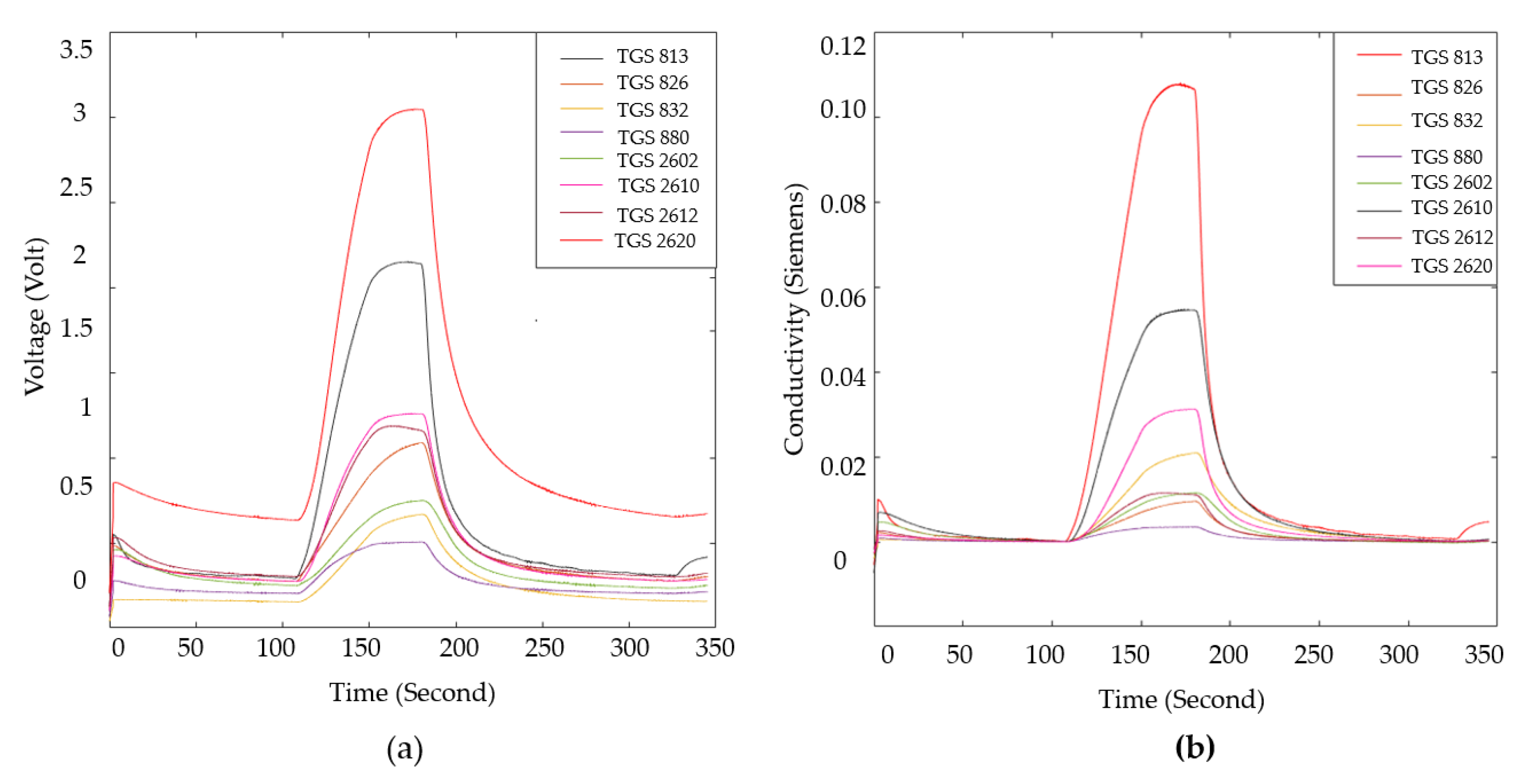

2.3. Analysis of Data and Extraction of Features

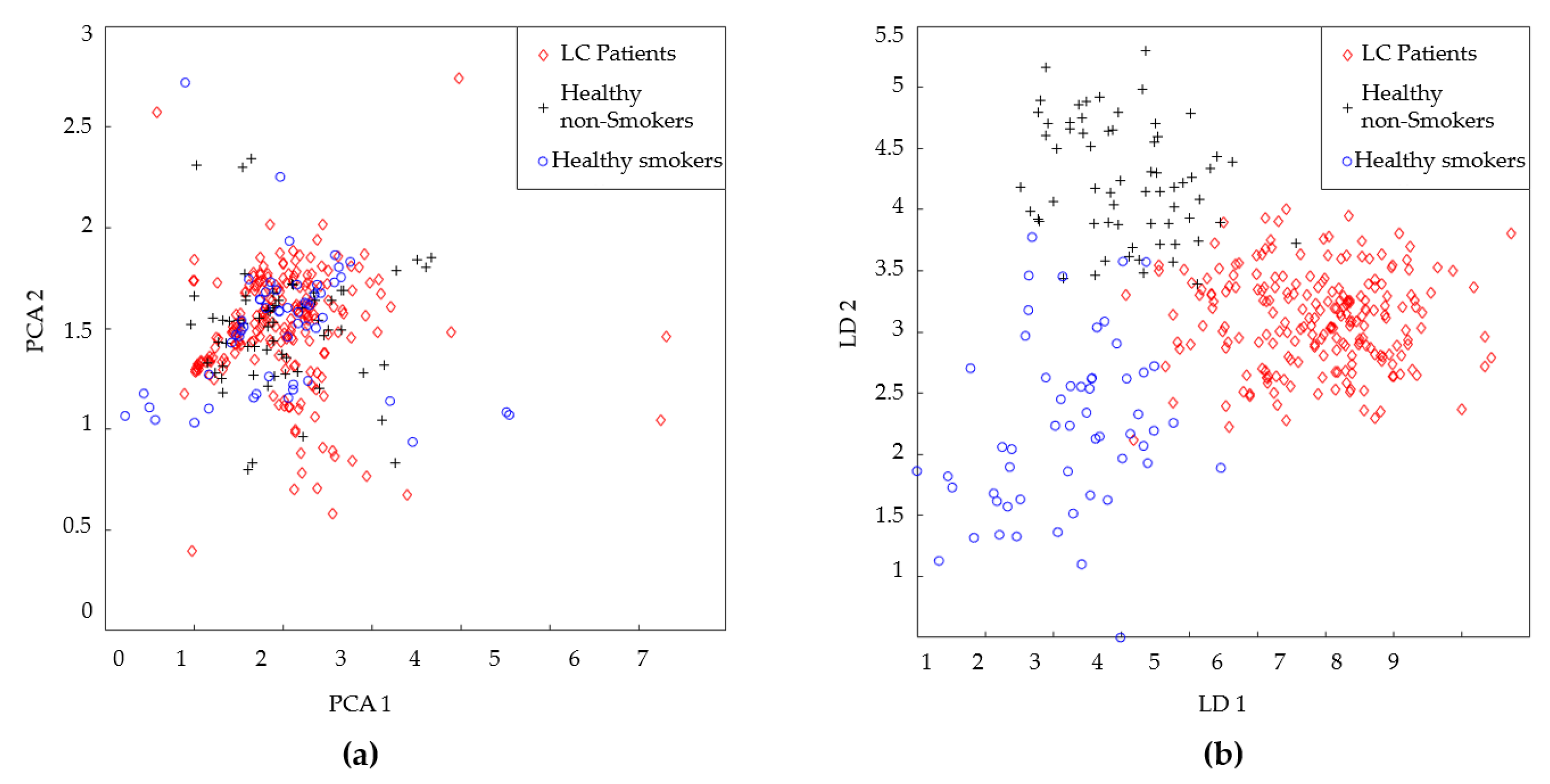

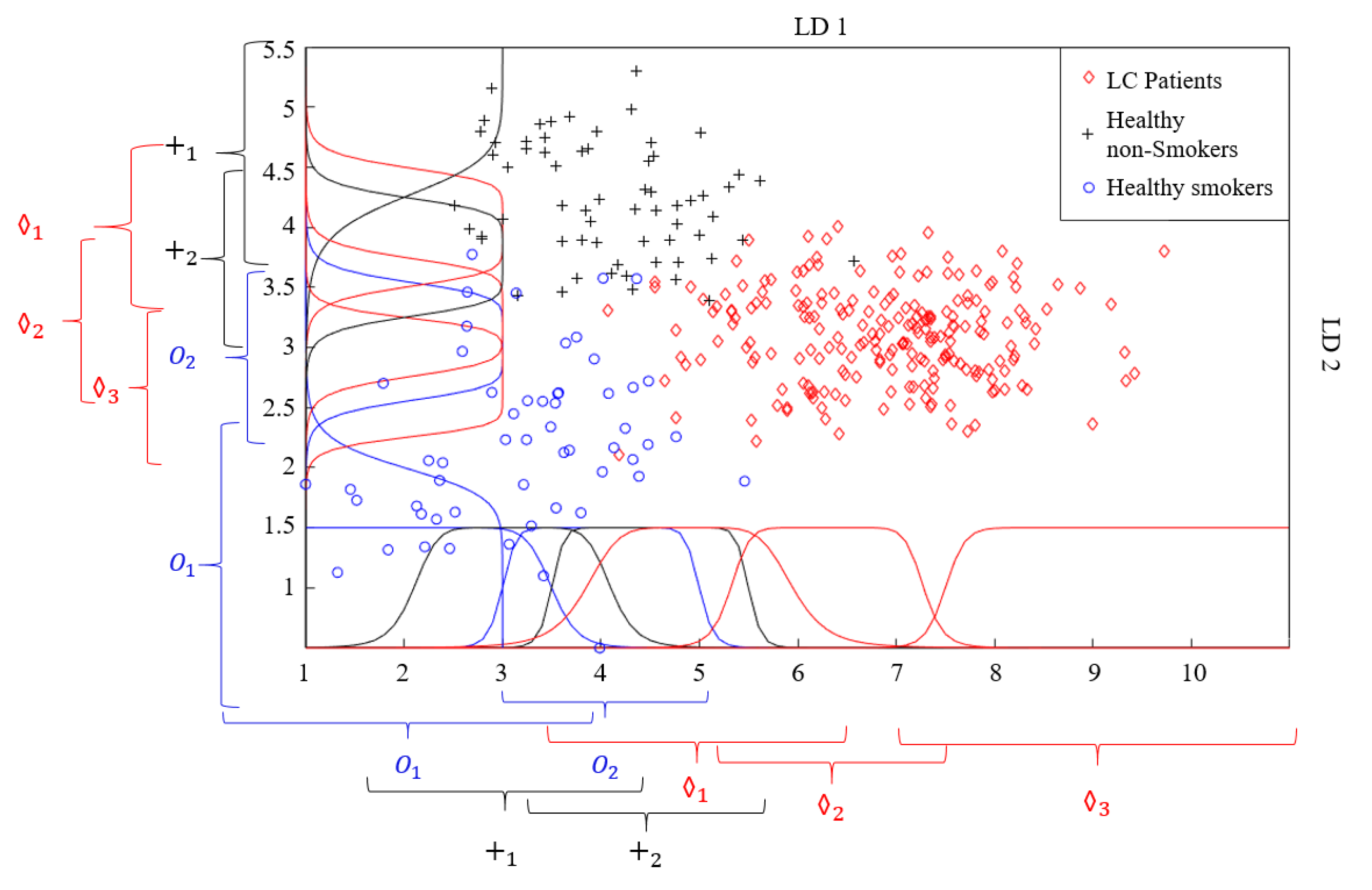

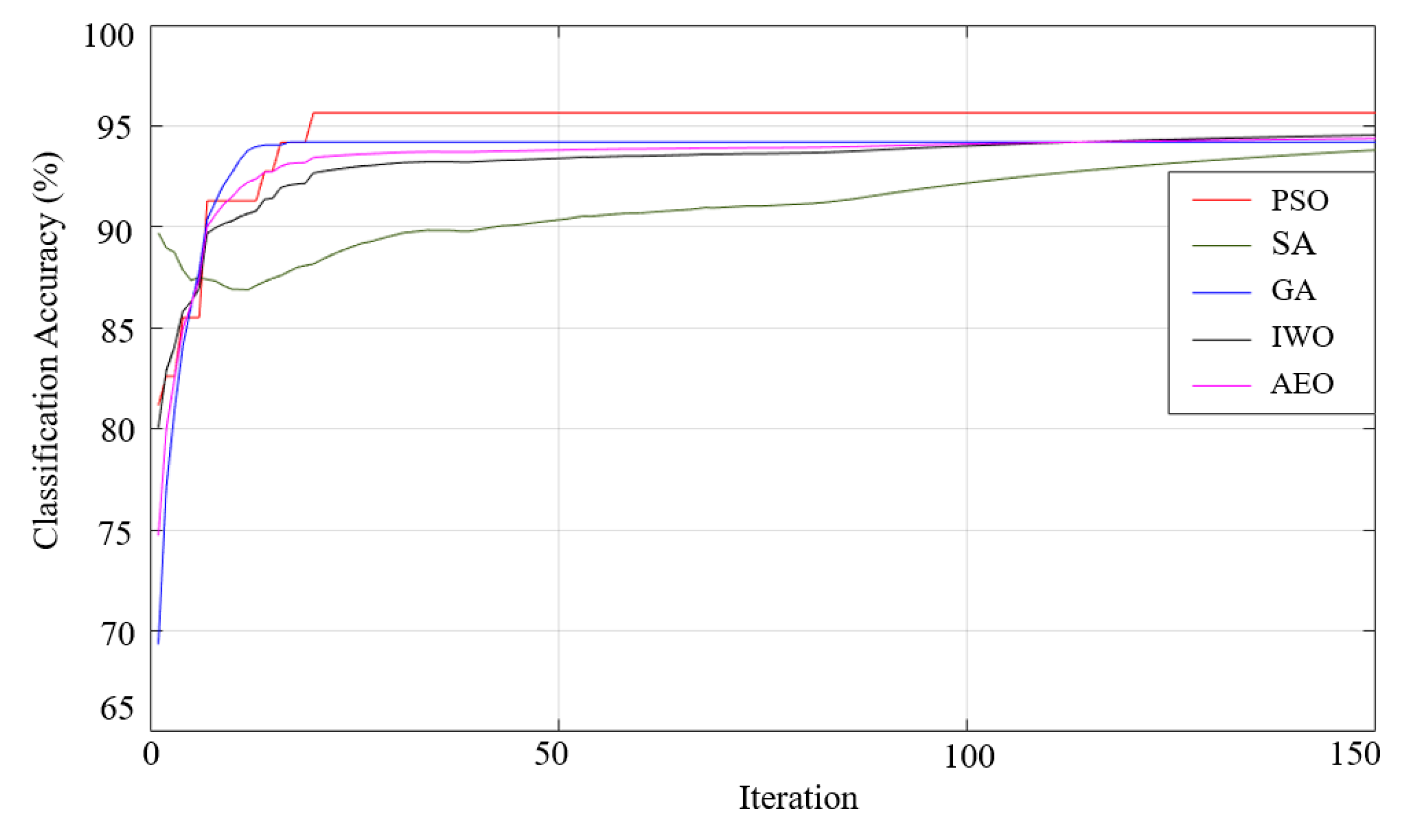

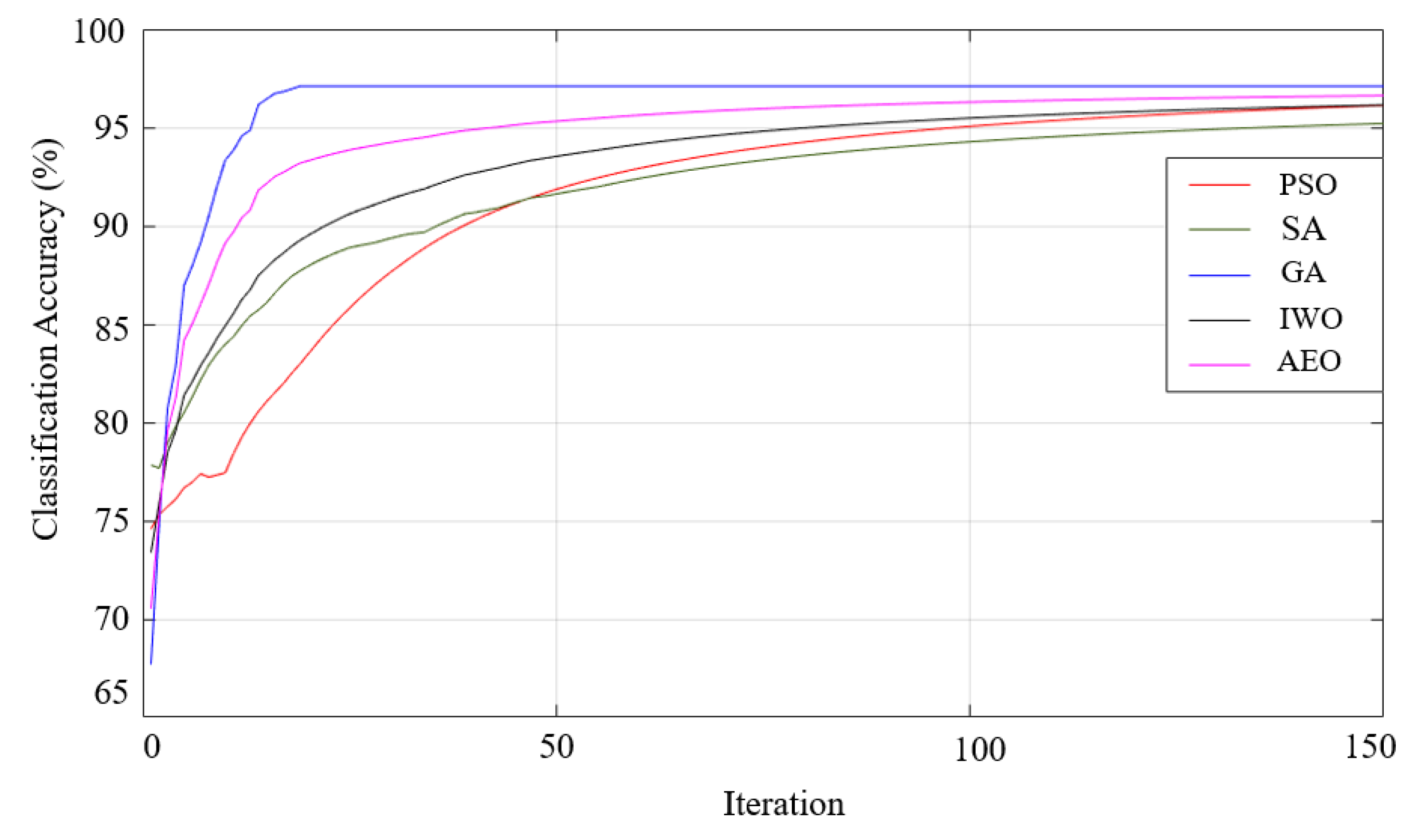

3. Data Classification and Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LC | Lung cancer |

| WHO | World health organization |

| VOC | Volatile organic molecules |

| GC-MS | Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry |

| E-NOSES | Electronic noses |

| QCM | Quartz crystal microbalance |

| MOS | Metal oxide semiconductor |

| TUBITAK | The Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey |

| FL | Fuzzy logic |

| AJCC | American Joint Committee on Cancer |

| LDA | Linear discriminant analysis |

| HnS | Healthy non-smokers |

| HS | Healthy smoker |

| DT | Decision tree |

| RF | Random forest |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| k-NN | k-nearest neighbor |

| SVM | Support vector machine |

| GA | Genetic algorithm |

| PSO | Particle swarm optimization |

| SA | Simulated annealing |

| IWO | Invasive weed optimization |

| AEO | Artificial ecosystem-based optimization |

References

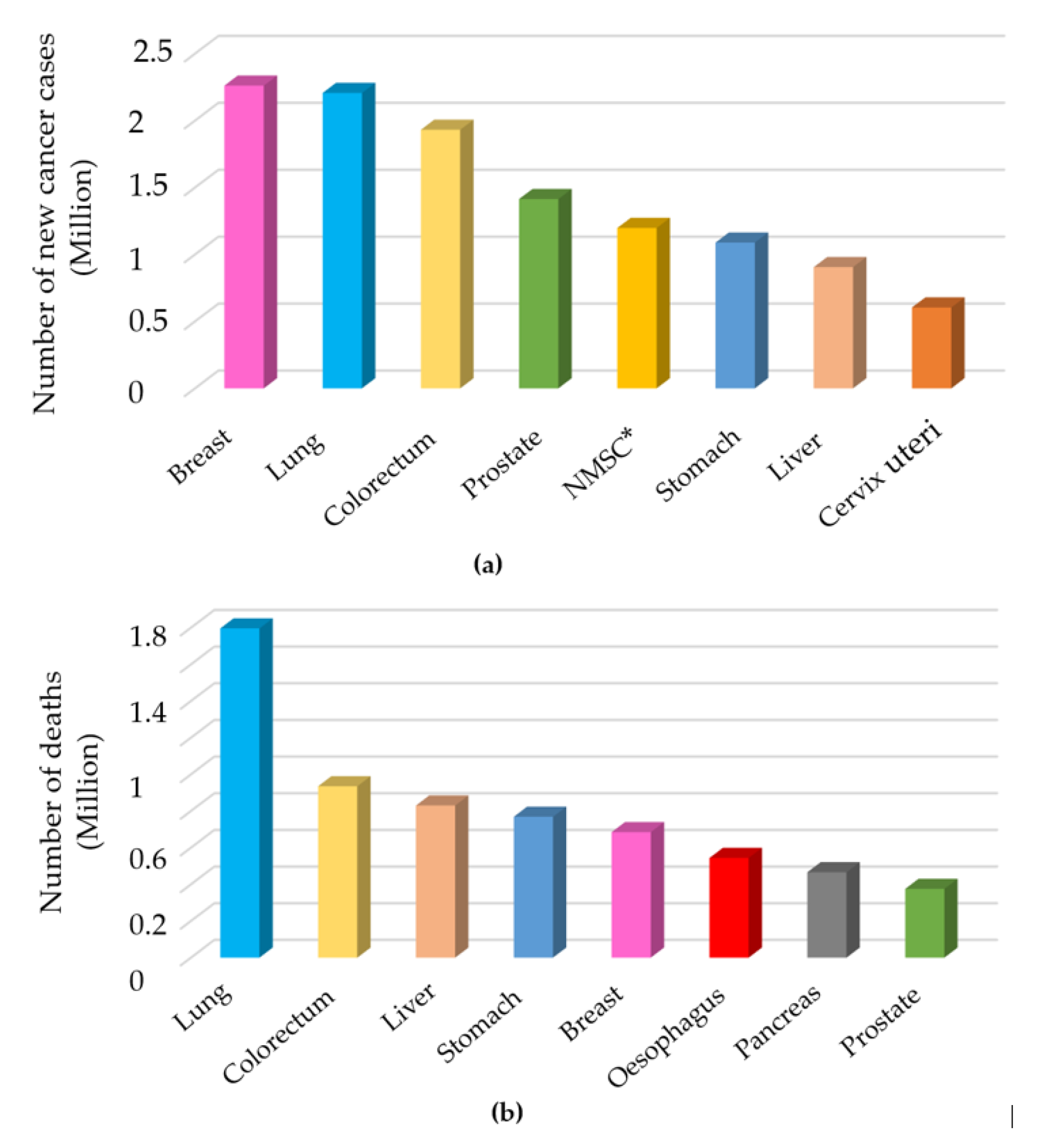

- Thandra, K. C.; Barsouk, A.; Saginala, K.; Aluru, J. S.; Barsouk, A. Epidemiology of lung cancer. Contemp. Oncol. 2021, 25, 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Ferlay, J.; Colombet, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Parkin, D. M.; Piñeros, M.; Znaor, A.; Bray, F. Cancer statistics for the year 2020: An overview. Int. J. Cancer 2021, 149, 778–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R. L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leiter, A.; Veluswamy, R. R.; Wisnivesky, J. P. The global burden of lung cancer: current status and future trends. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 20, 624–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

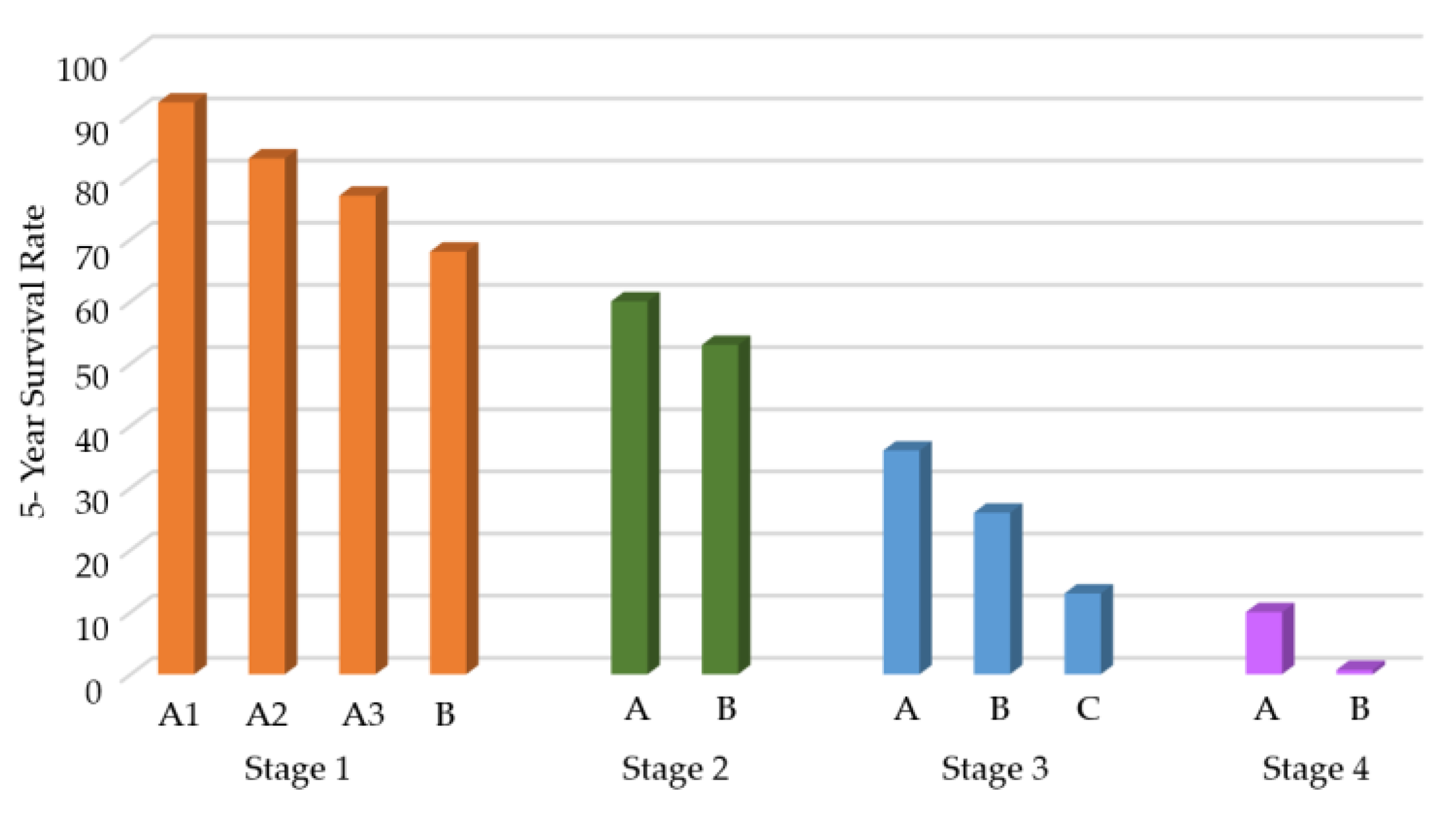

- Spigel, D. R.; Faivre-Finn, C.; Gray, J. E.; Vicente, D.; Planchard, D.; Paz-Ares, L.; Antonia, S. J. Five-year survival outcomes from the PACIFIC trial: durvalumab after chemoradiotherapy in stage III non–small-cell lung cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 1301–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VanderLaan, P. A.; Roy-Chowdhuri, S.; Griffith, C. C.; Weiss, V. L.; Booth, C. N. Molecular testing of cytology specimens: overview of assay selection with focus on lung, salivary gland, and thyroid testing. J. Am. Soc. Cytopathol. 2022, 11, 403–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morais, C. L.; Lima, K. M.; Dickinson, A. W.; Saba, T.; Bongers, T.; Singh, M. N.; Bury, D. Non-invasive diagnostic test for lung cancer using biospectroscopy and variable selection techniques in saliva samples. Analyst 2024, 149, 4851–4861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bano, A.; Yadav, P.; Sharma, M.; Verma, D.; Vats, R.; Chaudhry, D.; Bhardwaj, R. Extraction and characterization of exosomes from the exhaled breath condensate and sputum of lung cancer patients and vulnerable tobacco consumers—potential noninvasive diagnostic biomarker source. Journal of Breath Research 2024, 18, 046003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, P.; Zhou, Q.; Dao, D. Y.; Lo, Y. D. Circulating biomarkers in the diagnosis and management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 19, 670–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.; Muscat, J. E.; Sinha, R.; Sun, D.; Xiu, G. Proteomics of exhaled breath condensate in lung cancer and controls using data-independent acquisition (DIA): a pilot study. J. Breath Res. 2021, 15, 026002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nooreldeen, R.; Bach, H. Current and future development in lung cancer diagnosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakur, S. K.; Singh, D. P.; Choudhary, J. Lung cancer identification: a review on detection and classification. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2020, 39, 989–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quasar, S. R.; Sharma, R.; Mittal, A.; Sharma, M.; Agarwal, D.; de La Torre Díez, I. Ensemble methods for computed tomography scan images to improve lung cancer detection and classification. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2024, 83, 52867–52897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C. Y. Effectiveness of early cancer detection method: magnetic resonance imaging and X-ray technique. Proc. Int. Conf. Mod. Med. Glob. Health 2023, N/A, N/A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimazaki, A.; Ueda, D.; Choppin, A.; Yamamoto, A.; Honjo, T.; Shimahara, Y.; Miki, Y. Deep learning-based algorithm for lung cancer detection on chest radiographs using the segmentation method. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lancaster, H. L.; Heuvelmans, M. A.; Oudkerk, M. Low-dose computed tomography lung cancer screening: Clinical evidence and implementation research. J. Intern. Med. 2022, 292, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Issitt, T.; Wiggins, L.; Veysey, M.; Sweeney, S. T.; Brackenbury, W. J.; Redeker, K. Volatile compounds in human breath: critical review and meta-analysis. J. Breath Res. 2022, 16, 024001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

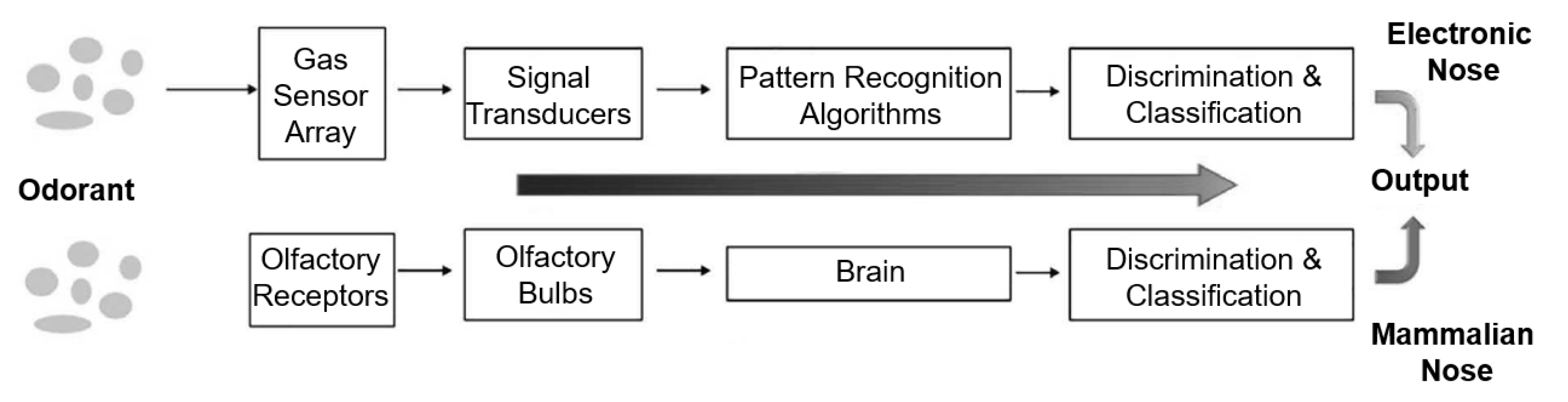

- Behera, B.; Joshi, R.; Vishnu, G. A.; Bhalerao, S.; Pandya, H. J. Electronic nose: A non-invasive technology for breath analysis of diabetes and lung cancer patients. J. Breath Res. 2019, 13, 024001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaim, O.; Bouchikhi, B.; Motia, S.; Abelló, S.; Llobet, E.; El Bari, N. Discrimination of diabetes mellitus patients and healthy individuals based on volatile organic compounds (VOCs): analysis of exhaled breath and urine samples by using e-nose and VE-tongue. Chemosensors 2023, 11, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, M. J.; Li, Y. J.; Wu, C. C.; Lee, Y. C.; Zan, H. W.; Meng, H. F.; Tian, Y. C. Breath ammonia is a useful biomarker predicting kidney function in chronic kidney disease patients. Biomedicines 2020, 8, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, G.; Jiang, D.; Wu, J.; Sun, X.; Deng, M.; Wang, L.; Chen, M. An ultrasensitive fluorescent breath ammonia sensor for noninvasive diagnosis of chronic kidney disease and Helicobacter pylori infection. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 440, 135979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, G.; Hakim, M.; Broza, Y. Y.; Billan, S.; Abdah-Bortnyak, R.; Kuten, A.; Haick, H. Detection of lung, breast, colorectal, and prostate cancers from exhaled breath using a single array of nanosensors. Br. J. Cancer 2010, 103, 542–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poli, D.; Goldoni, M.; Corradi, M.; Acampa, O.; Carbognani, P.; Internullo, E.; Mutti, A. Determination of aldehydes in exhaled breath of patients with lung cancer by means of on-fiber-derivatisation SPME–GC/MS. J. Chromatogr. B 2010, 878, 2643–2651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, Z.; Patra, A.; Kutty, V. K.; Venkatesan, T. Critical review of volatile organic compound analysis in breath and in vitro cell culture for detection of lung cancer. Metabolites 2019, 9, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, J.; Xu, J. Applications of electronic nose (e-nose) and electronic tongue (e-tongue) in food quality-related properties determination: a review. Artif. Intell. Agric. 2020, 4, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakhleh, M. K.; Amal, H.; Jeries, R.; Broza, Y. Y.; Aboud, M.; Gharra, A.; Haick, H. Diagnosis and classification of 17 diseases from 1404 subjects via pattern analysis of exhaled molecules. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 112–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binson, V. A.; Subramoniam, M.; Mathew, L. Discrimination of COPD and lung cancer from controls through breath analysis using a self-developed e-nose. J. Breath Res. 2021, 15, 046003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Aguilar, M.; de León-Martínez, L. D.; Gorocica-Rosete, P.; Pérez-Padilla, R.; Domínguez-Reyes, C. A.; Tenorio-Torres, J. A.; Flores-Ramírez, R. Application of chemoresistive gas sensors and chemometric analysis to differentiate the fingerprints of global volatile organic compounds from diseases. Preliminary results of COPD, lung cancer and breast cancer. Clin. Chim. Acta 2021, 518, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marzorati, D.; Mainardi, L.; Sedda, G.; Gasparri, R.; Spaggiari, L.; Cerveri, P. A metal oxide gas sensors array for lung cancer diagnosis through exhaled breath analysis. Proc. IEEE EMBC 2019, 2019, 1584–1587. [Google Scholar]

- Saidi, T.; Moufid, M.; de Jesus Beleño-Saenz, K.; Welearegay, T. G.; El Bari, N.; Jaimes-Mogollon, A. L.; Bouchikhi, B. Non-invasive prediction of lung cancer histological types through exhaled breath analysis by UV-irradiated electronic nose and GC/QTOF/MS. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2020, 311, 127932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kort, S.; Brusse-Keizer, M.; Schouwink, H.; Citgez, E.; de Jongh, F. H.; van Putten, J. W.; van der Palen, J. Diagnosing non-small cell lung cancer by exhaled breath profiling using an electronic nose: a multicenter validation study. Chest 2023, 163, 697–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gasparri, R.; Sedda, G.; Spaggiari, L. The electronic nose’s emerging role in respiratory medicine. Sensors 2018, 18, 3029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, A.D.; Baietto, M. Advances in Electronic-Nose Technologies Developed for Biomedical Applications. Sensors 2011, 11, 1105–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, B.; Fu, L.; Nie, B.; Peng, Z.; Liu, H. A Novel Framework with High Diagnostic Sensitivity for Lung Cancer Detection by Electronic Nose. Sensors 2019, 19, 5333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyagi, H.; Daulton, E.; Bannaga, A.S.; Arasaradnam, R.P.; Covington, J.A. Non-Invasive Detection and Staging of Colorectal Cancer Using a Portable Electronic Nose. Sensors 2021, 21, 5440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Y.; Li, Q.; Liang, H.; Lam, H. K. A novel mixed control approach for fuzzy systems via membership functions online learning policy. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2021, 30, 3812–3822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antczak, T. Optimality conditions for invex nonsmooth optimization problems with fuzzy objective functions. Fuzzy Optimization and Decision Making 2023, 22, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Wan, S.; Chen, S. M. Fuzzy best-worst method based on triangular fuzzy numbers for multi-criteria decision-making. Inf. Sci. 2021, 547, 1080–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, W.; Pan, Y. Enhancing Electronic Nose Performance by Feature Selection Using an Improved Grey Wolf Optimization Based Algorithm. Sensors 2020, 20, 4065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai, Z.; Liu, Y.; Li, C.; Wang, D.; Wu, H. Electronic Noses: From Gas-Sensitive Components and Practical Applications to Data Processing. Sensors 2024, 24, 4806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Nadeem, M.; Banka, H. Nature inspired optimization algorithms: a comprehensive overview. Evol. Syst. 2023, 14, 141–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, K.; Zhao, T. Interpretable and robust online self-organizing granule-based fuzzy rule classification for data stream. Int. J. Fuzzy Syst. 2025, N/A, N/A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Xu, X.; Sun, S.; et al. An improved adaptive particle swarm optimization based on belief rule base. Int. J. Fuzzy Syst. 2025, N/A, N/A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| LC patient (60 Person) | Healthy volunteer (40 Person) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (Mean / St. deviation) | 60.7 / 8 | 48.2 / 9 |

| Gender (Female / Male) | 13/47 | 10/30 |

| Smokers / Non-smokers | 0/60 | 20/20 |

| Ex-smokers | 45/60 | 0/40 |

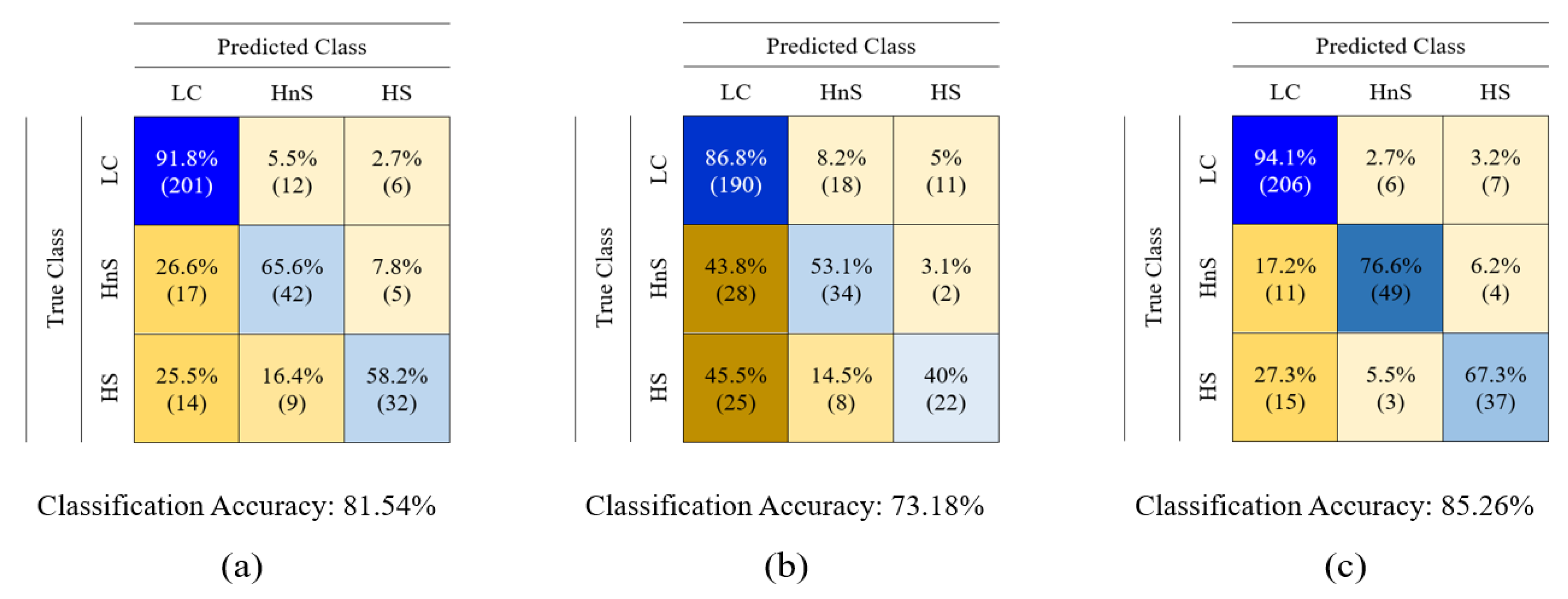

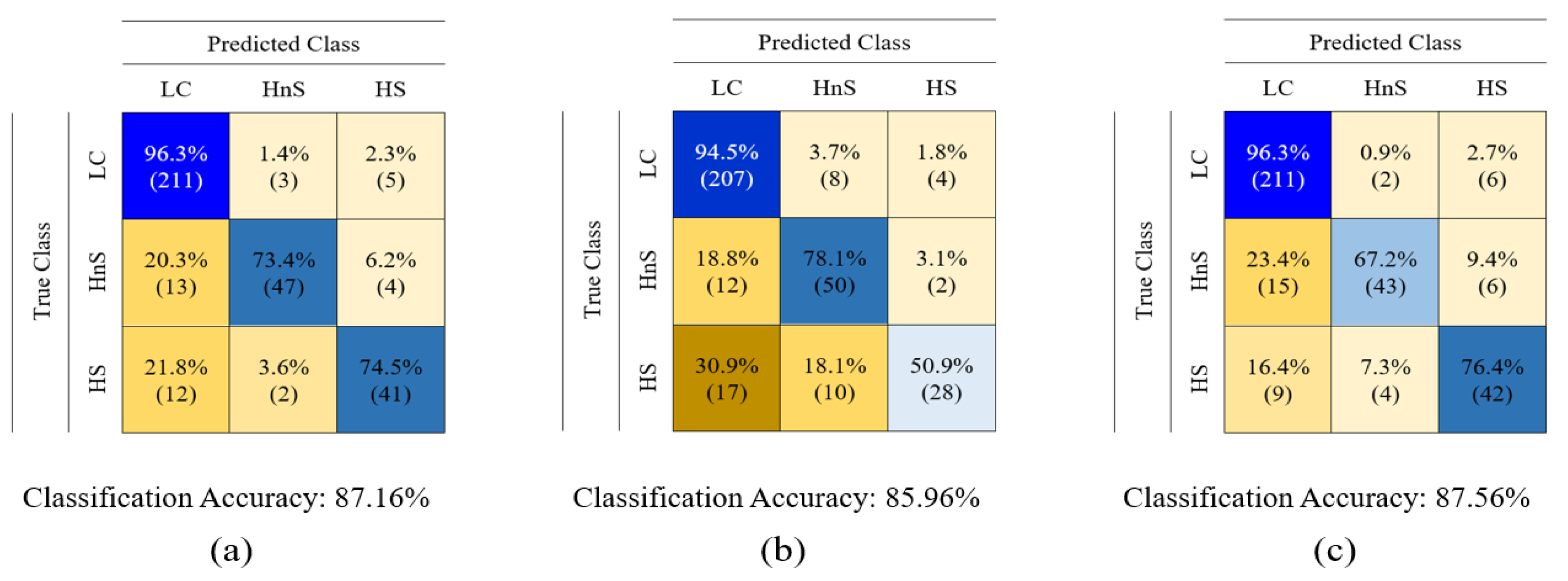

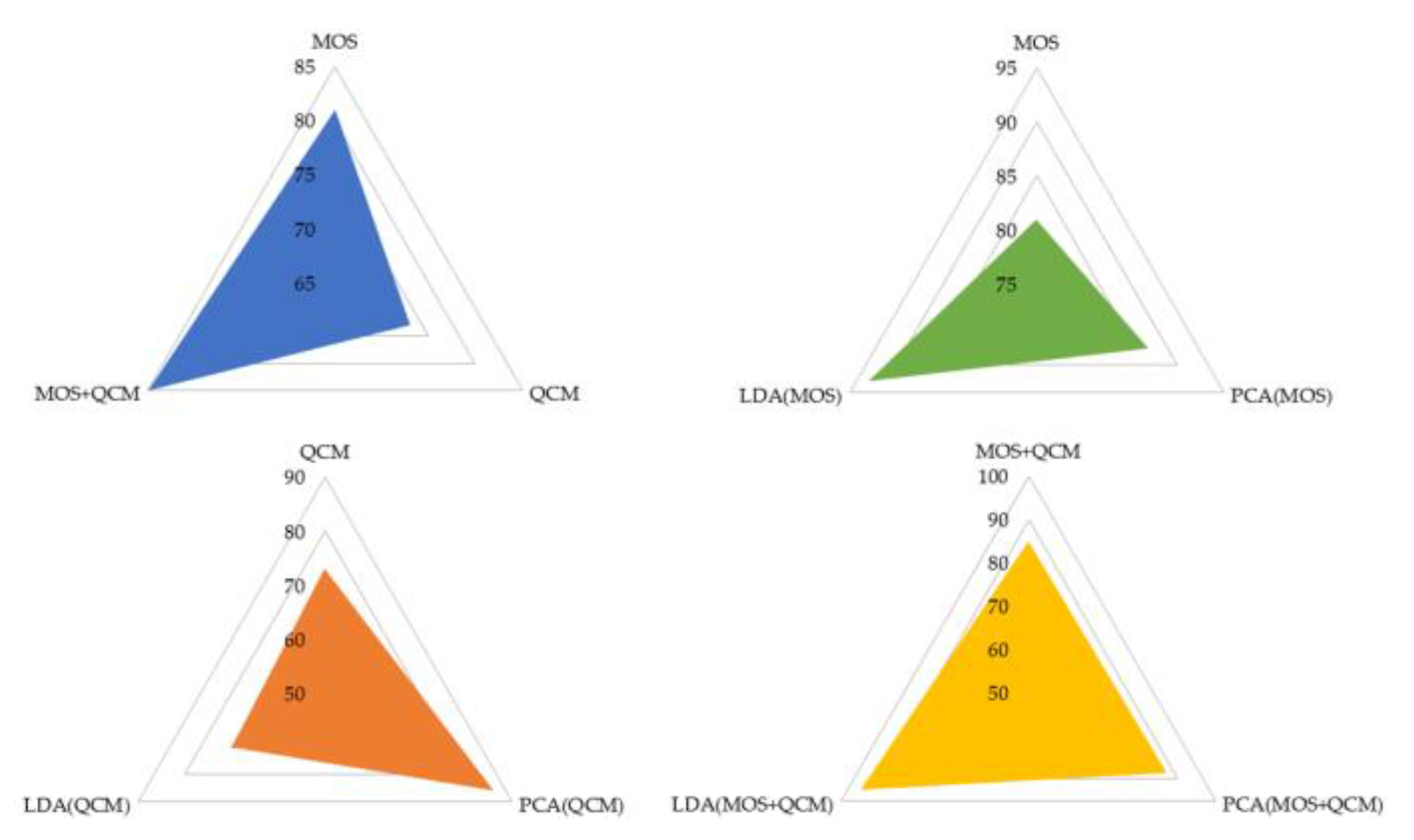

| Types of features | Classification algorithms | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DT | L-SVM | Q-SVM | C-SVM | k-NN | RF | |

| MOS | 75,34 77,8-72,8-1,90 |

75,52 77-74,6-1,08 |

81,12 82,1-79,3-1,17 |

81,28 82-79,3-1,12 |

74,3 79,9-71,3-3,30 |

81,54 82,8-79,9-1,09 |

| PCA(MOS) | 85,20 86,1-84,3-0,67 |

67,86 70,2-64,9-2,17 |

67.66 70,2-64,9-2,11 |

85.76 86,4-84,9-0,62 |

81,06 81,9-79,6-0,90 |

87,16 88,1-86,1-0,88 |

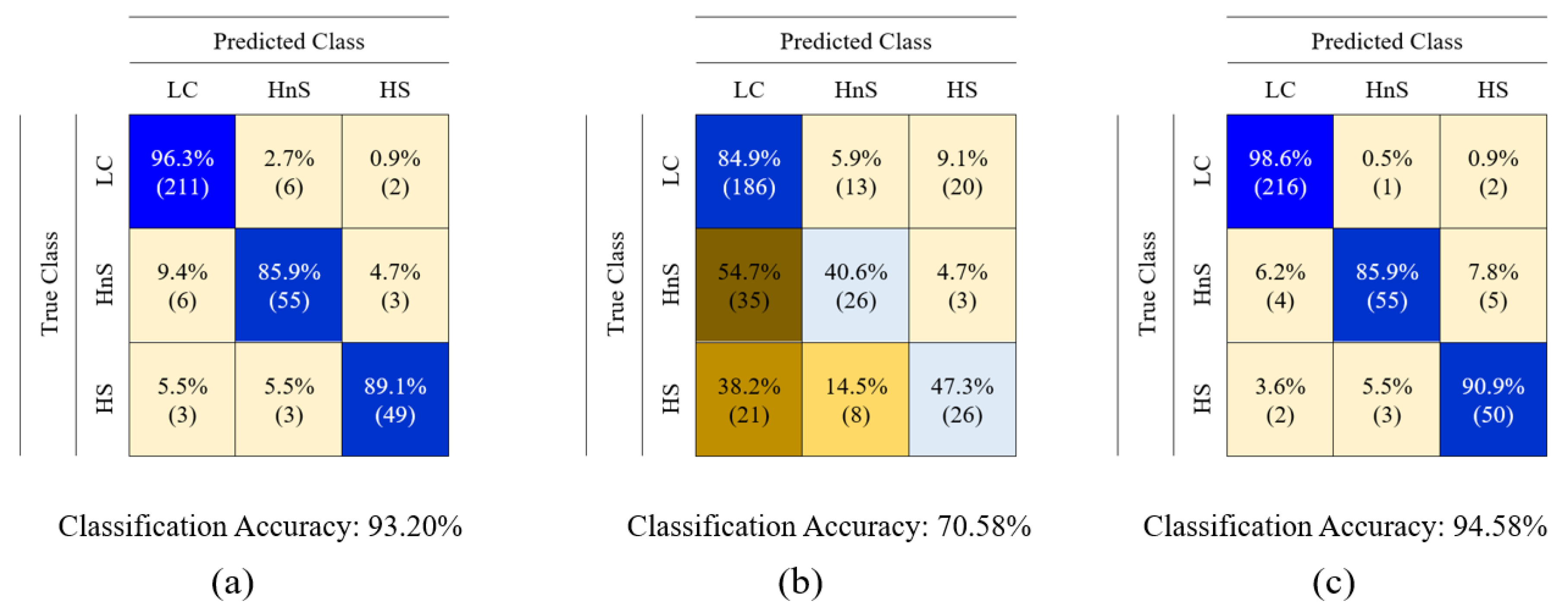

| LDA(MOS) | 88,80 90,1-87,3-1,11 |

93.20 93,1-91,3-0,78 |

92,60 92,9-91,7-0,45 |

91,56 92,8-90,2-1,06 |

90,10 90,8-89,4-0,51 |

90,04 90,8-89,1-0,80 |

| QCM | 66,82 70,7-64,2-2,70 |

64,32 64,8-64-0,43 |

71,96 74,0-70,1-1,46 |

69,66 73,4-66,5-2,51 |

70,50 72,2-68,9-1,33 |

73,18 75,1-70,7-1,77 |

| PCA(QCM) | 74.96 76,9-73,7-1,25 |

67,86 70,2-64,9-2,17 |

67.66 70,2-64,9-2,11 |

82,22 84,3-79,3-1,93 |

85.96 87-84,9-0,89 |

80,20 81,0-79-0,87 |

| LDA(QCM) | 67,30 68,6-65,7-1,30 |

67,86 70,2-64,9-2,17 |

67.66 70,2-64,9-2,11 |

68,92 70,1-68-0,78 |

66,76 70,4-63,3-2,95 |

70,58 71,2-69,9-0,56 |

| MOS+QCM | 76,06 77,8-74-1,43 |

76,84 77,8-75,4-0,96 |

85,26 86,4-83,7-1,05 |

85,18 86,1-84,1-0,79 |

75,38 76-74,9-0,48 |

82,24 82,9-81,4 0,58 |

| PCA (MOS+QCM) |

84,24 84,9-83,4-0,60 |

67,86 70,2-64,9-2,17 |

67,66 70,2-64,9-2,11 |

81,46 82,2-80,8-0,63 |

80,36 85,8-75,4-4,18 |

87,56 88,1-87,2-0,35 |

| LDA (MOS+QCM) |

94,40 94,7-93,8-0,36 |

94,52 94,7-94,4-0,16 |

93,80 94,7-92,9-0,73 |

92.90 94,1-91,6-0,97 |

92,30 93,8-91,4-0,95 |

94,58 95,6-94,1-0,62 |

| PCA(MOS)+ PCA(QCM) |

83,40 85,2-82,0-1,33 |

67,86 70,2-64,9-2,17 |

70,02 70,7-69,2-0,56 |

83,10 83,7-82,2-0,60 |

88,56 88,8-88,2-0,25 |

87,14 88,2-86,10-0,77 |

| LDA(MOS)+ LDA(QCM) |

89,80 90,5-88,9-0,65 |

93,08 93,8-92-0,75 |

92,60 93,8-92-0,73 |

90,74 91,4-89,6-0,80 |

90,60 90,5-89,6-0,35 |

90,92 91,4-90,2-0,54 |

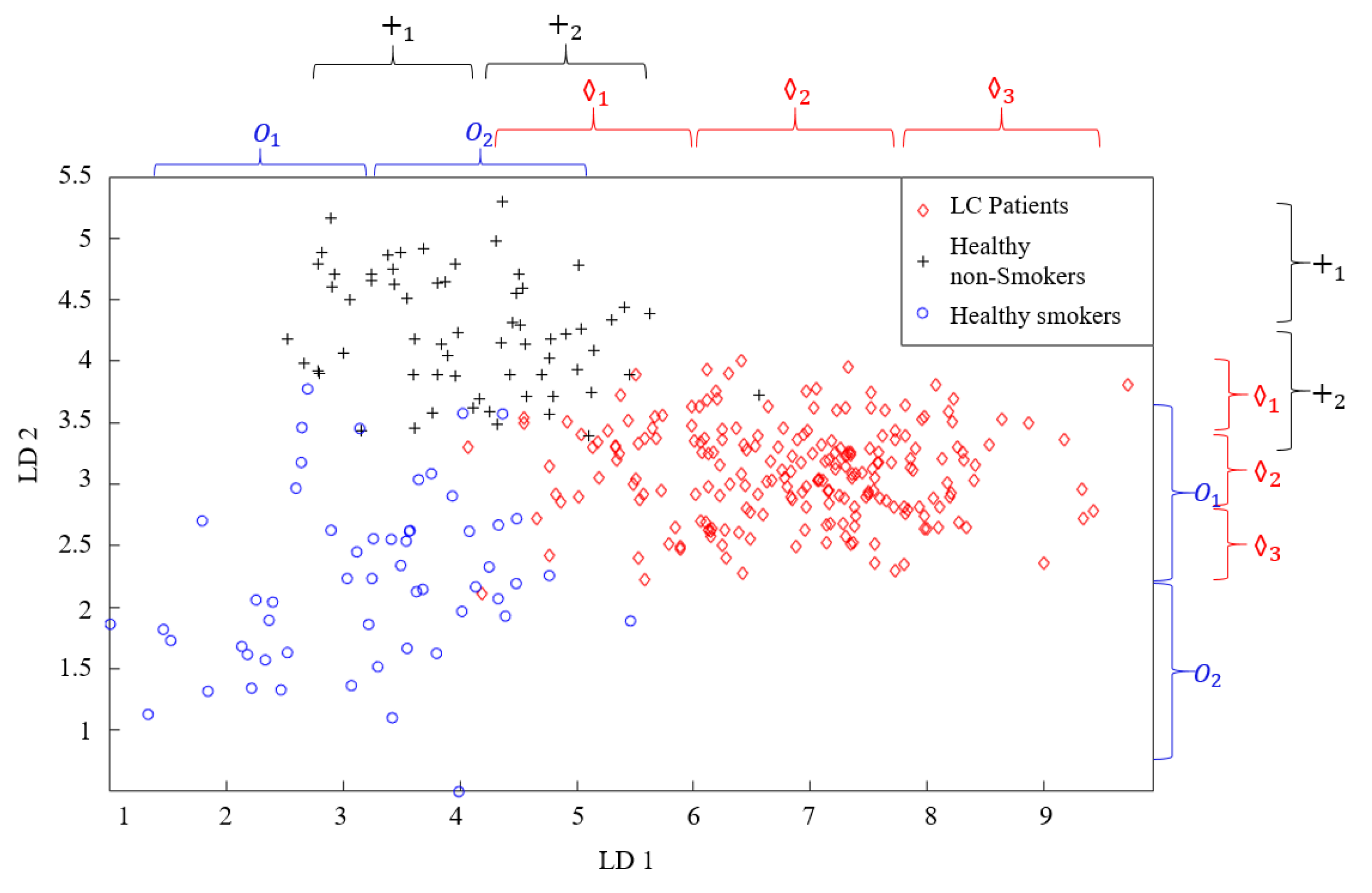

| LD1 | ||||||||

| LD2 | ||||||||

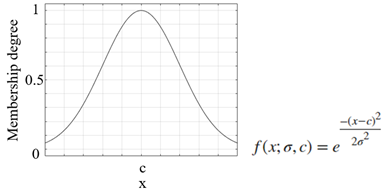

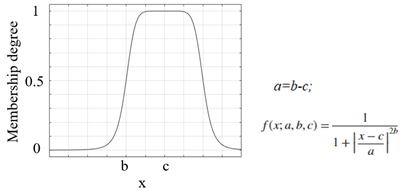

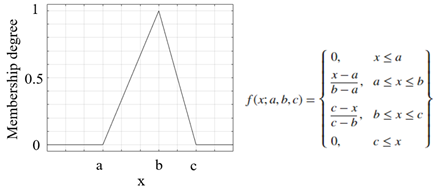

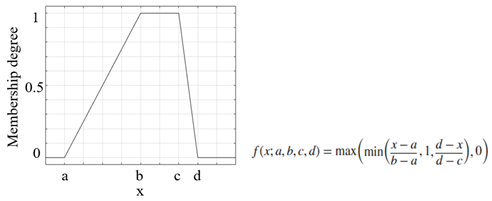

| Membership Function | Graph and equation of membership function |

|---|---|

| Gaussian membership function |  |

| Generalized bell-shaped membership function |  |

| Triangular membership function |  |

| Trapezoidal membership function |  |

| Pi-shaped membership function |  |

| Algorithm | Tuning parameters | Operators |

|---|---|---|

| GA | Crossover rate | Selection crossover rate, Crossover mutation |

| PSO | Social acceleration coefficient, Inertia weight, cognitive acceleration coefficient | Particle velocity update, Particle position update |

| SA | Temperature | Annealing process |

| AEO | Energy transfer mechanism, | Production,Consumption,Decomposition, Reproduction |

| IWO | Invasive weed spread | Spectral spread, Competitive deprivation |

| Algorithm | Source of inspiration | Number of solutions | Nature of algorithm |

|---|---|---|---|

| GA | Biology | Multiple | Stochastic |

| PSO | Biology | Multiple | Stochastic |

| SA | Physics | Single | Stochastic |

| AEO | Biology | Multiple | Stochastic |

| IWO | Biology | Multiple | Stochastic |

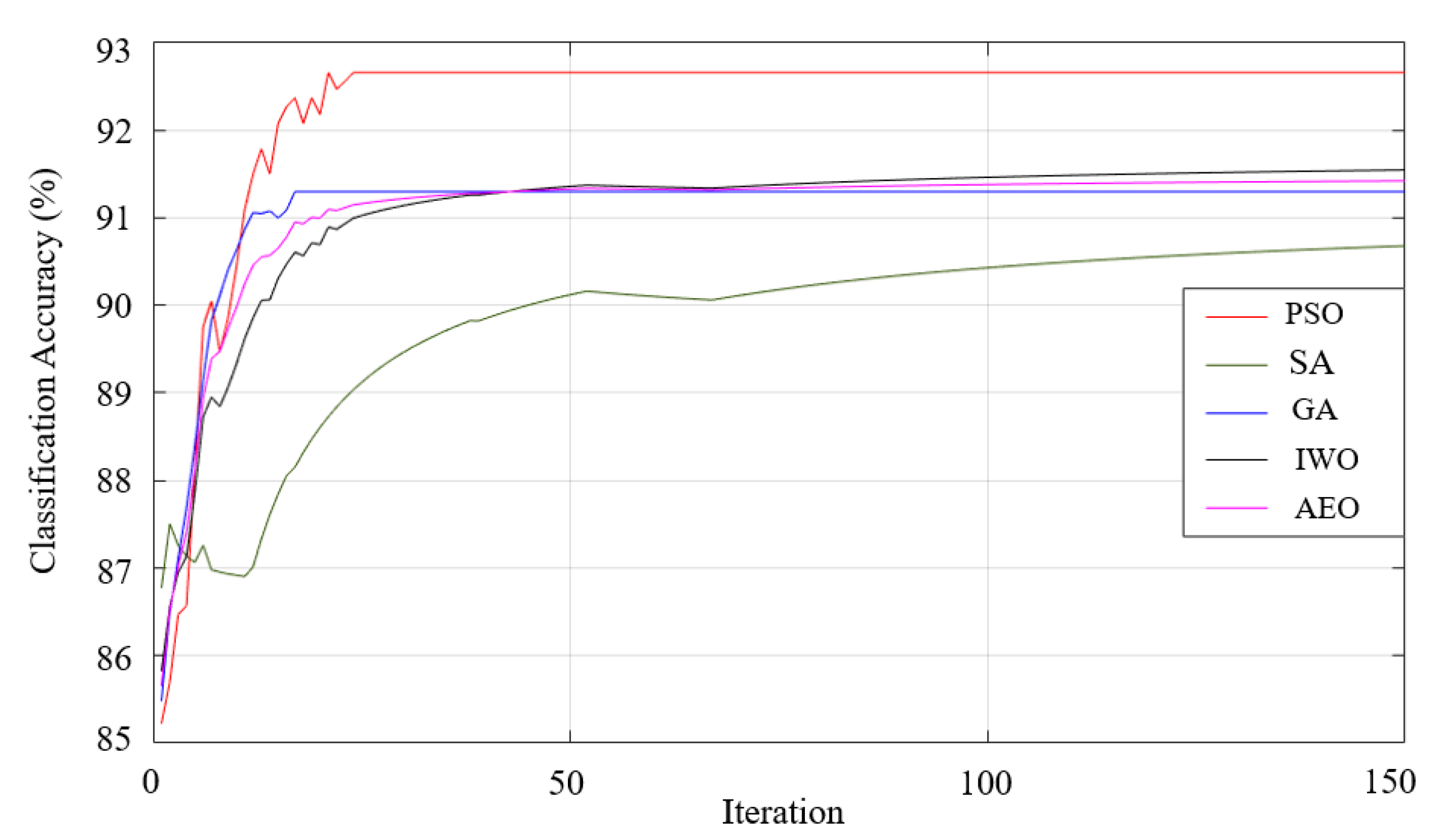

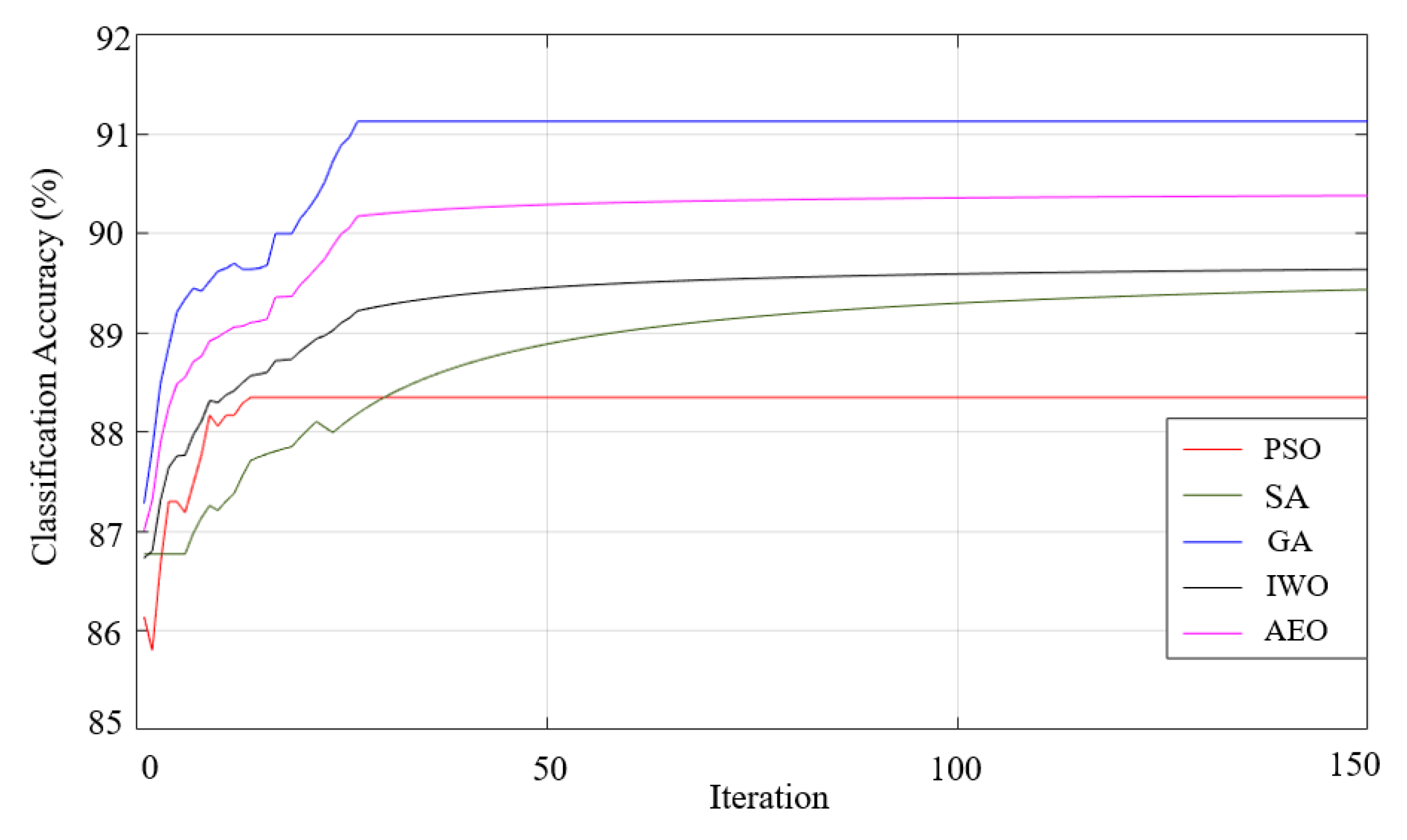

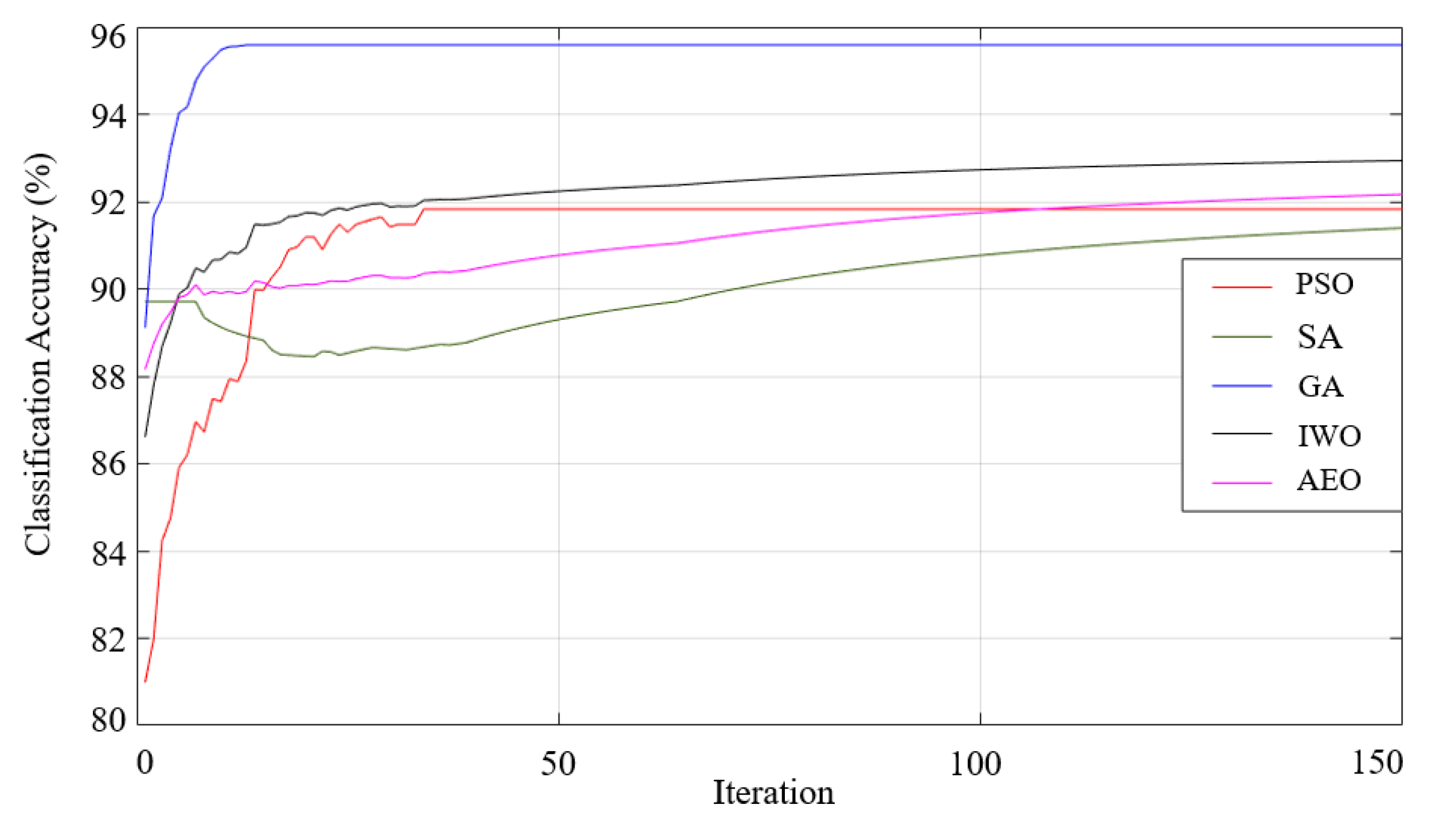

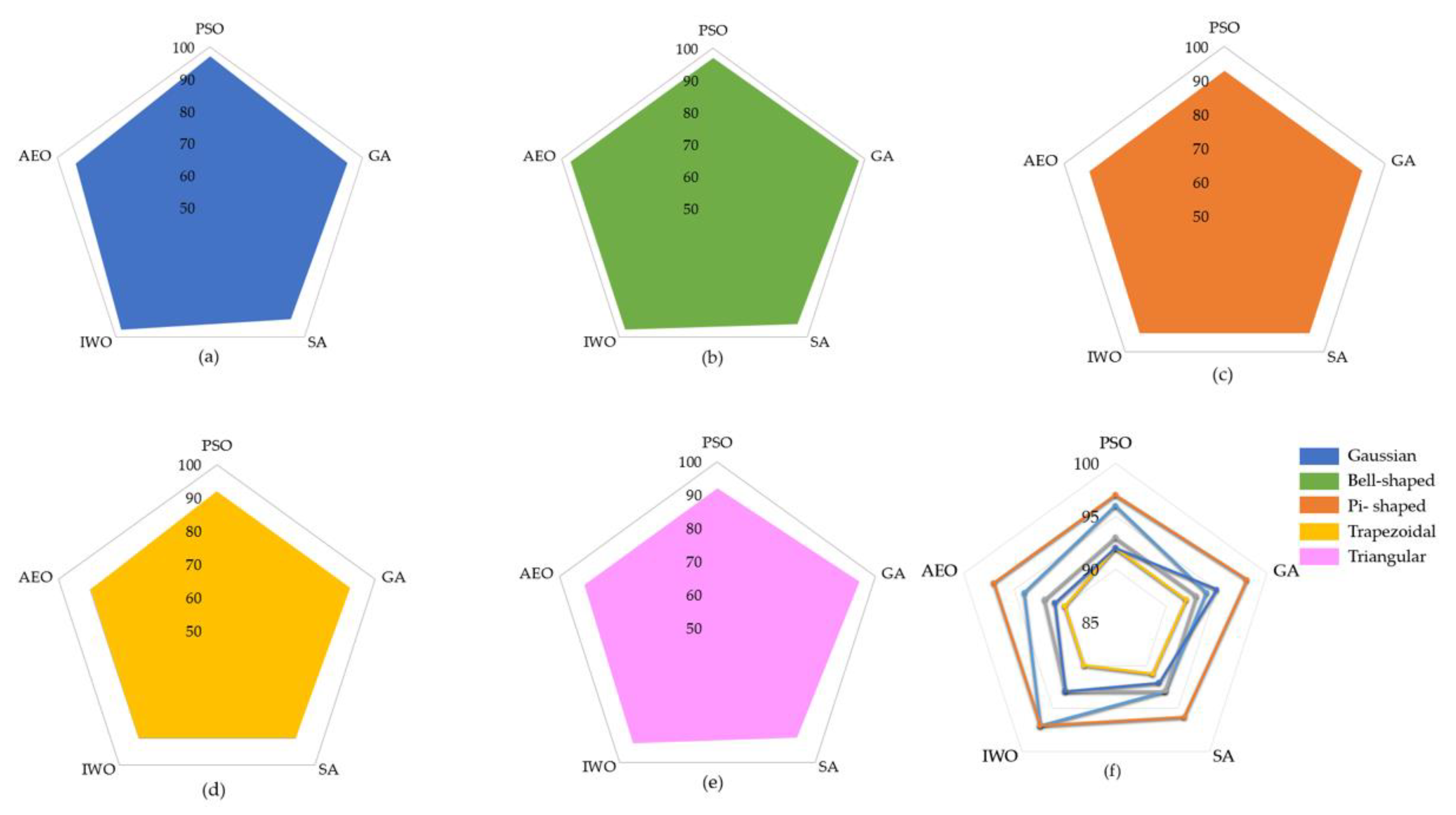

| Membership Functions |

Optimization Algorithms | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSO | GA | SA | IWO | AEO | |

| Gaussian | 95.69 98.07-92.80-2.41 |

94.81 97.95-92.07-2.27 |

92.95 97.36-87.22-3.77 |

97.27 98.81-94.71-1.66 |

93.82 97.06-91.18-2.18 |

| Generalized Bell-shaped |

97.27 99.26-95.30-1.72 |

97.93 100-95.89-1.75 |

95.7 99.11-92.62-2.29 |

97.44 98.56-95.59-1.49 |

97.56 98.56-95.59-1.37 |

| Pi | 92.98 97.06-91.18-2.33 |

92.79 97.06-91.18-2.43 |

92.94 97.06-91.18-2.39 |

93.23 97.06-91.18-2.23 |

92.65 97.06-91.05-2.54 |

| Trapezoidal | 91.74 97.06-88.41-3.35 |

92.01 97.06-89.56-3.07 |

90.79 97.06-86.67-3.79 |

89.95 97.06-86.68-4.22 |

90.3 97.06-86.77-3.95 |

| Triangular | 92.3 95.59-89.55-2.22 |

94.81 95.59-92.07-2.27 |

91.62 95.59-89.71-2.51 |

92.7 97.06-9.71-2.77 |

91.47 95.59-89.56-2.63 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).