Introduction

Dysfunction in mitochondria is essential to understanding how Parkinson’s Disease (PD) develops [

1], influencing both sporadic and hereditary cases due to reduced ATP synthesis and greater sensitivity to oxidative stress [

2,

3]. The heightened metabolic demands of dopaminergic neurons render them particularly sensitive to such bioenergetic deficits, which, alongside impaired mitochondrial quality control mechanisms, exacerbate neuronal degeneration [

4,

5]. In light of this, fresh therapeutic avenues, encompassing mitochondria-focused and gene therapy techniques [

6], are underway to boost mitochondrial health, alleviate oxidative pressure [

5], and deal with α-synuclein accumulation [

3], possibly influencing the advancement of the disease.

Methylene blue (MB) presents significant therapeutic possibilities for Parkinson’s disease (PD) through its wide-ranging biological mechanisms, such as acting as an alternate electron carrier within the mitochondrial electron transport chain, which raises ATP synthesis and lowers oxidative stress—a vital consideration given the mitochondrial dysfunction evident in PD [

7,

8,

9]. Evidence of MB’s role in safeguarding neurons is reflected in its function to enhance brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and trigger crucial pathways that support the health of dopaminergic neurons [

10]. Concurrently, innovative therapeutic approaches utilizing nanobubbles and gaseous transmitters, like hydrogen sulfide [

11], have exhibited neuroprotective effects by mitigating neurotoxin-induced deficits and enhancing mitochondrial function through improved oxygen delivery [

12]. Furthermore, advancements in nanotechnology facilitate more effective central nervous system drug delivery [

13,

14] and protection against oxidative stress [

15], revealing promising avenues for PD treatment [

16].

The precise mechanisms by which MB, nanobubbles, and gaseous transmitters exert their therapeutic effects need to be further elucidated, particularly in the context of PD’s multifactorial nature. Furthermore, the long-term safety, tolerability, and efficacy of these approaches must be rigorously assessed through well-designed clinical trials before widespread clinical application can be recommended.

Methods

Study Design: This study is a descriptive case report documenting the effects of a combined intravenous nanobubble and methylene blue (MB) therapy in an elderly patient diagnosed with advanced-stage Parkinson’s disease (PD). It was conducted as a longitudinal observational study without a control group and aimed to evaluate changes in motor function and quality of life during and after the intervention period.

Subject: The subject was a 71-year-old male with a 22-year history of idiopathic Parkinson’s disease, classified as Hoehn & Yahr stage III.

Intervention: The therapy consisted of 48 sessions of intravenous infusion over a period of 70 days (April 23 – July 1, 2025), administered five times per week. Each infusion session involved a combination of the following:

Hydrogen–oxygen (HHO) nanobubbles, Gasotransmitters (primarily nitric oxide/NO), Methylene blue (MB), with dosage titrated based on the patient’s clinical tolerance. The composition and volume of the infusates were adjusted according to an internal clinical protocol. The patient was closely monitored during and after each session for any adverse reactions.

Measurements and Evaluation: Quantitative and qualitative evaluations were performed before and after the intervention using the following assessments: Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale Part III (UPDRS-III): to assess motor symptoms specific to PD, Timed Up and Go (TUG) Test: to evaluate mobility and balance, 10-Meter Walk Test (10MWT): to assess gait speed. Measurements were recorded at baseline and after the final infusion session (Day 70). In addition, ongoing clinical observations were conducted throughout the treatment course to document subjective and objective changes in postural stability, speech clarity, tremor, physical stamina, and duration of activity without fatigue.

Safety and Ethics: Adverse events were monitored and recorded throughout the intervention period. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for both the therapy and the publication of this case report.

Result

The patient was a 71-year-old male with a 22-year history of idiopathic Parkinson’s disease (PD), initially classified as Hoehn & Yahr stage III. At baseline, he presented with gait instability, slow ambulation, hypophonia (low voice volume), a right-hand tremor, right-dominant postural rigidity, and fatigue that limited his ability to walk or stand for more than 15 minutes. He was maintained on Madopar® (levodopa/benserazide) 1.5 tablets per day, Equfina® (safinamide), metformin 500 mg BID, a beta-blocker, and vitamin B12 supplementation—none of which were altered during the treatment course.

The intervention consisted of 48 sessions of intravenous infusion over a 70-days period (April 23 – July 1, 2025), administered 5 times per week. Each infusion included hydrogen–oxygen (HHO) nanobubbles, nitric oxide (NO), and other gasotransmitters (GTs), combined with methylene blue (MB). MB dosage was adjusted based on clinical tolerance.

Quantitative outcomes showed clinically meaningful improvements across multiple motor performance metrics. The patient’s Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale Part III (UPDRS-III) motor score improved from 28 to 18, representing a 35.71% reduction. His Timed Up and Go (TUG) time decreased from 15 to 3 seconds, and his 10-Meter Walk Test (10MWT) speed doubled from 0.5 m/s to 1.0 m/s. These improvements are summarized in

Table 1.

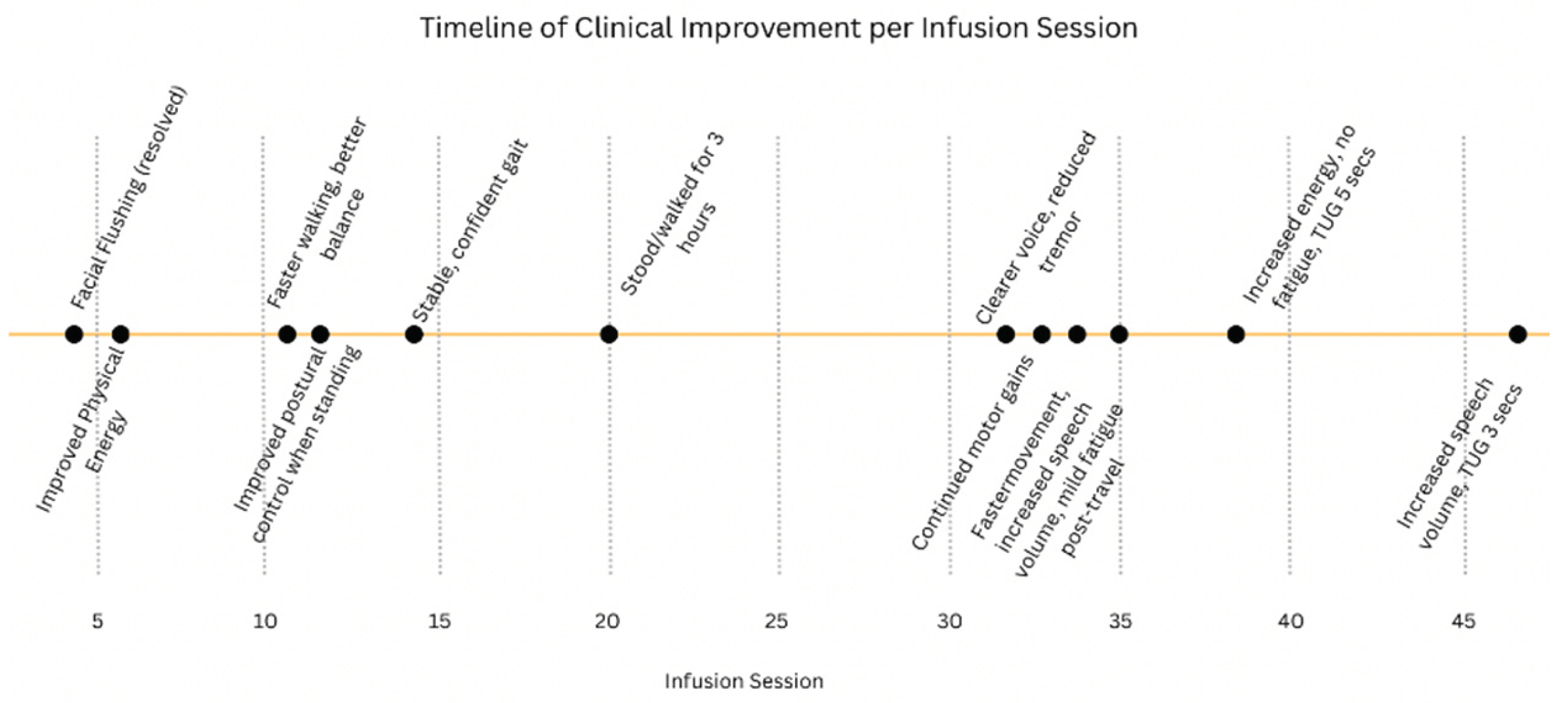

The clinical progression was also monitored qualitatively across infusion sessions. Early signs of improvement began as early as session #6, with reported increases in physical energy. Subsequent sessions were associated with enhanced gait stability, improved postural control, better voice clarity, and decreased tremor. By session #20, the patient could walk and stand for up to three hours without fatigue. The trajectory of these functional improvements is illustrated in

Figure 1.

Aside from a brief episode of facial flushing during infusion #4 that resolved spontaneously, no adverse effects were reported. The patient expressed feeling “stronger, lighter, and more balanced,” with notable improvements in stamina, speech clarity, and reduced tremor. He reported greater independence and satisfaction with his daily function following the therapy.

Discussion

This case report highlights meaningful motor and functional improvements in a 71-year-old patient with advanced Parkinson’s disease (PD) following 48 sessions of intravenous nanobubble and methylene blue (MB) therapy. The observed 10-point reduction in the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale Part III (UPDRS-III) motor score exceeds the minimal clinically important difference (MCID) of 3.25 points, indicating a clinically significant benefit [

17]. Improvements in the Timed Up and Go (TUG) test and the 10-Meter Walk Test (10MWT) further reflect enhanced gait stability and mobility, which are essential for fall prevention and overall quality of life in PD patients [

18].

Emerging evidence suggests that gasotransmitters—such as hydrogen sulfide (H₂S), nitric oxide (NO), carbon monoxide (CO), and hydrogen—offer therapeutic promise in neurodegenerative diseases through their antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-apoptotic properties [

19]. These molecules may protect vulnerable neuronal populations and potentially slow disease progression, thus presenting an avenue beyond traditional symptomatic treatment [

20]. Hydrogen nanobubbles, in particular, have demonstrated both safety and metabolic benefits in preclinical and clinical contexts, supporting their utility in managing neurodegenerative conditions [

21,

22]. Moreover, the nanoscale size of these delivery vehicles may facilitate penetration of the blood–brain barrier (BBB), enhancing the bioavailability of therapeutic agents in affected brain regions [

23].

Methylene blue contributes synergistically to this approach by acting as a mitochondrial enhancer. It serves as an alternative electron carrier in the mitochondrial respiratory chain, supporting complex IV activity and improving ATP production. MB also possesses antioxidant properties and functions as a monoamine oxidase inhibitor—effects that together may counteract the mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress implicated in PD pathogenesis [

21,

22,

24]. The combined use of MB and gasotransmitters may thus address multiple pathological mechanisms of PD, including impaired mitochondrial bioenergetics, neuroinflammation, and oxidative damage—areas often left unaddressed by current dopaminergic therapies [

20,

24].

Despite the encouraging results, several limitations must be acknowledged. This was a single-subject case report without a placebo control or mechanistic biomarkers such as neuroimaging or serum oxidative stress profiles. The observed improvements, while objective, must be interpreted with caution in the absence of long-term follow-up and a control group. Moreover, the durability of these clinical gains remains unknown. Nonetheless, this case aligns with growing evidence that nanotechnology-based drug delivery systems may offer promising adjunctive strategies in PD management by overcoming BBB-related limitations and enhancing the precision of neurotherapeutic targeting [

19,

23]

Looking forward, larger controlled clinical trials incorporating both clinical and mechanistic endpoints are essential to confirm the efficacy of combined nanobubble and MB therapy. Such studies could clarify not only the therapeutic potential but also the biological underpinnings of this multimodal intervention, potentially paving the way for novel, disease-modifying strategies in PD.

This case report has several limitations that must be acknowledged. First, it involves a single subject without a control group, limiting the generalizability of the findings. The absence of placebo control prevents any definitive conclusions about causality, as spontaneous fluctuations in Parkinson’s symptoms or placebo effects cannot be ruled out. Additionally, there were no mechanistic biomarkers, such as neuroimaging or biochemical assays, to objectively confirm the underlying physiological changes associated with the intervention. Finally, the long-term durability of the observed clinical improvements remains unknown, as follow-up beyond the 49-day treatment period was not conducted. These limitations underscore the need for larger, controlled studies with extended observation periods and mechanistic endpoints.

Conclusions

This case supports the potential role of intravenous nanobubbles and methylene blue as a clinically effective intervention in Parkinson’s disease. The observed improvements in motor and functional outcomes justify further investigation through well-powered, controlled clinical trials aimed at validating efficacy and exploring underlying mechanisms.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Patel, M. and McElroy, P.B., 2017. Mitochondrial dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease.

- Henrich, M.T. , Oertel, W.H., Surmeier, D.J. and Geibl, F.F., 2023. Mitochondrial dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease–a key disease hallmark with therapeutic potential. Molecular neurodegeneration, 18(1), p.83.

- Bhatt, V.; Shukla, H.; Tiwari, A.K. Parkinson's Disease and Mitotherapy-Based Approaches towards α-Synucleinopathies. J. Integr. Neurosci. 2024, 23, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, X.-Y.; Yang, T.; Gu, Y.; Sun, X.-H. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Parkinson’s Disease: From Mechanistic Insights to Therapy. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 885500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, O. , 2013. Role of oxidative stress in Parkinson’s disease. Experimental neurobiology, 22(1), p.11.

- Kumar, A.; Gupta, A.K.; Singh, P.K. Novel perspective of therapeutic modules to overcome motor and nonmotor symptoms in Parkinson's disease. AIMS Neurosci. 2024, 11, 312–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poteet, E.; Winters, A.; Yan, L.-J.; Shufelt, K.; Green, K.N.; Simpkins, J.W.; Wen, Y.; Yang, S.-H.; Linden, R. Neuroprotective Actions of Methylene Blue and Its Derivatives. PLOS ONE 2012, 7, e48279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, A.-L.; Poteet, E.; Du, F.; Gourav, R.C.; Liu, R.; Wen, Y.; Bresnen, A.; Huang, S.; Fox, P.T.; Yang, S.-H.; et al. Methylene Blue as a Cerebral Metabolic and Hemodynamic Enhancer. PLOS ONE 2012, 7, e46585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tucker, D.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, Q. From Mitochondrial Function to Neuroprotection—an Emerging Role for Methylene Blue. Mol. Neurobiol. 2017, 55, 5137–5153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhurtel, S.; Katila, N.; Neupane, S.; Srivastav, S.; Park, P.; Choi, D. Methylene blue protects dopaminergic neurons against MPTP-induced neurotoxicity by upregulating brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Ann. New York Acad. Sci. 2018, 1431, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, X.; Cao, L.; Ding, L.; Bian, J.-S. A New Hope for a Devastating Disease: Hydrogen Sulfide in Parkinson’s Disease. Mol. Neurobiol. 2017, 55, 3789–3799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, C. , Manzano, M., Vallet-Regi, M. and Gomez, L., 2023. Oxygen nanobubbles for improving tissue oxygenation in neurodegenerative diseases. Advanced Healthcare Materials, 12(3), p.2201204.

- Dogra, N. , Jakhmola Mani, R. and Pande Katare, D., 2024. Tiny carriers, tremendous hope: nanomedicine in the fight against Parkinson’s. Journal of Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease, 1(1), pp.3-21.

- Cheng, G.; Liu, Y.; Ma, R.; Cheng, G.; Guan, Y.; Chen, X.; Wu, Z.; Chen, T. Anti-Parkinsonian Therapy: Strategies for Crossing the Blood–Brain Barrier and Nano-Biological Effects of Nanomaterials. Nano-Micro Lett. 2022, 14, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padilla-Godínez, F.J.; Ruiz-Ortega, L.I.; Guerra-Crespo, M. Nanomedicine in the Face of Parkinson’s Disease: From Drug Delivery Systems to Nanozymes. Cells 2022, 11, 3445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandal, M. , Mukherjee, A. and Gupta, S., 2018. New vista in Parkinson’s disease treatment: magic of nanotechnology. Journal of the Indian Chemical Society, 95(8), pp.997-1002.

- Goetz, C.G.; Tilley, B.C.; Shaftman, S.R.; Stebbins, G.T.; Fahn, S.; Martinez-Martin, P.; Poewe, W.; Sampaio, C.; Stern, M.B.; Dodel, R.; et al. Movement Disorder Society-sponsored revision of the Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS): Scale presentation and clinimetric testing results. Mov. Disord. 2008, 23, 2129–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, M.E.; Huxham, F.; McGinley, J.; Dodd, K.; Iansek, R. The biomechanics and motor control of gait in Parkinson disease. Clin. Biomech. 2001, 16, 459–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Dan, Q.; Xu, B.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, T. Research progress on gas signal molecular therapy for Parkinson’s disease. Open Life Sci. 2023, 18, 20220658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schapira, A.H. and Jenner, P., 2011. Etiology and pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. Movement Disorders, 26(6), pp.1049–1055.

- Gonzalez-Lima, F.; Auchter, A. Protection against neurodegeneration with low-dose methylene blue and near-infrared light. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, Y.; Li, W.; Poteet, E.C.; Xie, L.; Tan, C.; Yan, L.-J.; Ju, X.; Liu, R.; Qian, H.; Marvin, M.A.; et al. Alternative Mitochondrial Electron Transfer as a Novel Strategy for Neuroprotectionin stroke. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 2011, 5, 567–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunay, M.S.; Ozer, A.Y.; Chalon, S. Drug Delivery Systems for Imaging and Therapy of Parkinson';s Disease. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2016, 14, 376–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabassum, S.; Wu, S.; Lee, C.-H.; Yang, B.S.K.; Gusdon, A.M.; Choi, H.A.; Ren, X.S. Mitochondrial-targeted therapies in traumatic brain injury: From bench to bedside. Neurotherapeutics 2024, 22, e00515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).