Submitted:

21 July 2025

Posted:

22 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Neuropsychological Assessments

2.3. Emotional Measures and Subjective Complaints

2.4. Procedure

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

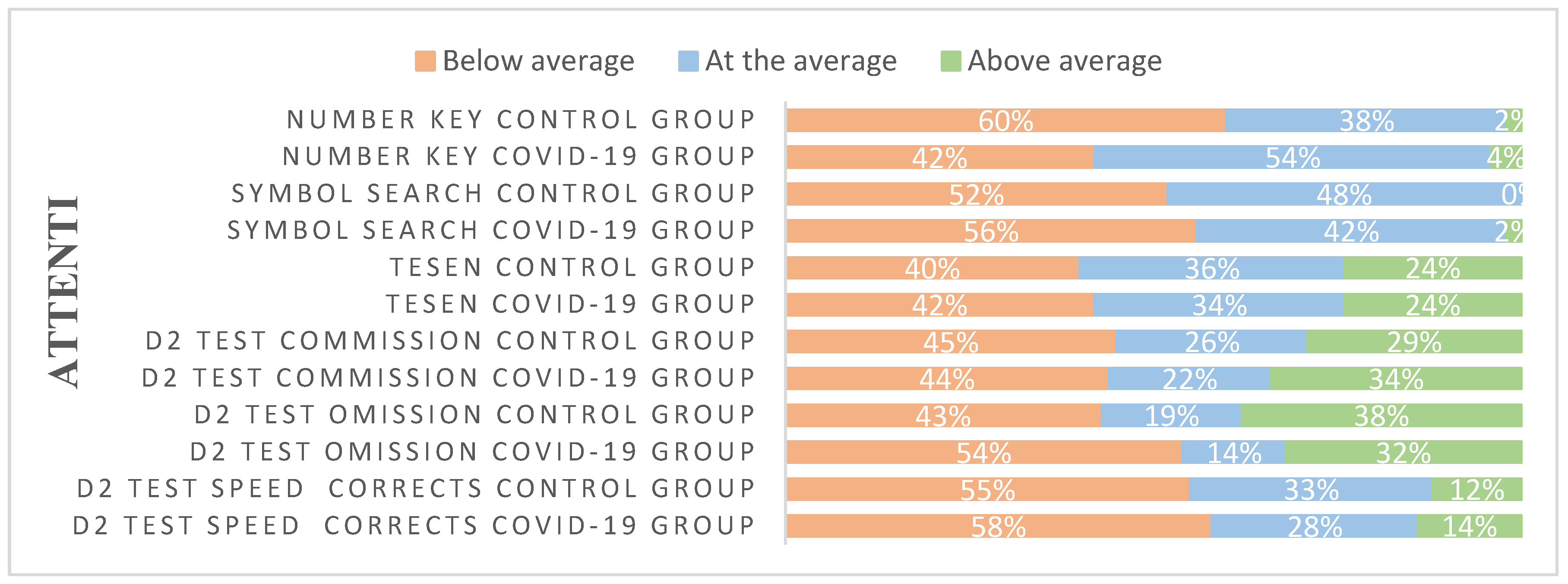

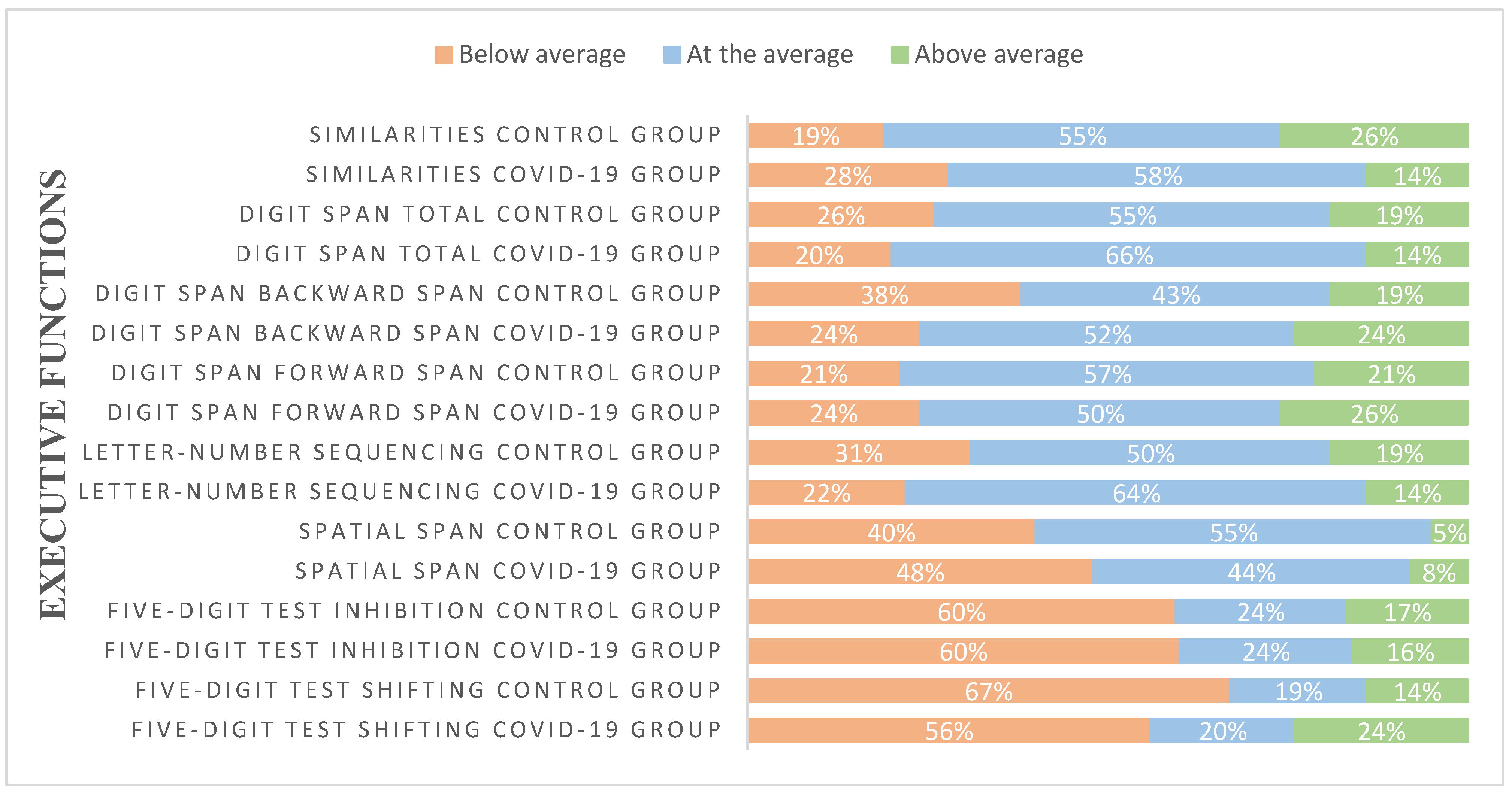

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

3.2. Analyses on Neuropsychological Measures

3.3. Analyses on Emotional Symptomatology and Subjective Complaints

3.4. Relationship Between Neuropsychological Tests and Emotional Symptomatology

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BADS | Behavioral Assessment of the Dysexecutive Syndrome |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| CoVs | Coronavirus |

| HUFA | University Hospital Alcorcon Foundation |

| ISP-20 | Prefrontal Symptom Inventory |

| MBI | Maslach’s Burnout Inventory |

| MFE-30 | Failures in Everyday Life Questionnaire |

| MoCA | Montreal Cognitive Assessment |

| PCL | Post-traumatic Stress Checklist-Civilian |

| PHQ-9 | Patient Health Questionnaire-9 |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 |

| SCL-90 | Symptom Cheklist-90 |

| STAI | State-Trait Anxiety Inventory |

| TESEN | The Test of the Paths |

| TMT | Trail Making Test |

| WAIS-IV | Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Adults-IV |

| WMS-III | Wechsler Memory Scale III |

References

- World Health Organization. A clinical case definition of post COVID-19 condition by a Delphi consensus. Geneva: WHO; 2024.

- Hu, B. , Guo, H., Zhou, P., & Shi, Z. L. (2021). Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 19(3), 141–154. [CrossRef]

- Bailey EK, Steward KA, VandenBussche Jantz AB, Kamper JE, Mahoney EJ, Duchnick JJ. Neuropsychology of COVID 19: Anticipated cognitive and mental health outcomes. Neuropsychology. 2021;35(4):335–51. [CrossRef]

- Boldrini M, Canoll P, Klein RS. How COVID 19 affects the brain. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78(6):682–3. [CrossRef]

- Zhao S, Toniolo S, Hampshire A, Husain M. Effects of COVID 19 on cognition and brain health. Trends Cogn Sci. 2023;27(11):1053–67. [CrossRef]

- Maiese A, Manetti AC, Bosetti C, Del Duca F, La Russa R, Frati P, et al. SARS CoV 2 and the brain: A review of neuropathology in COVID 19. Brain Pathol. 2021;31(6):e13013. [CrossRef]

- Becker JH, Lin JJ, Doernberg M, Stone K, Navis A, Festa JR, et al. Assessment of Cognitive Function in Patients after COVID 19 Infection. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(10):e2130645. [CrossRef]

- Daroische R, Hemminghyth MS, Eilertsen TH, Breitve MH, Chwiszczuk LJ. Cognitive impairment after COVID 19 — a review on objective test data. Front Neurol. 2021;12:699582. [CrossRef]

- Hampshire A, Trender W, Chamberlain SR, Jolly AE, Grant JE, Patrick F, et al. Cognitive deficits in people who have recovered from COVID 19. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;39:101044. [CrossRef]

- Ceban F, Ling S, Lui LMW, Lee Y, Gill H, Teopiz KM, et al. Fatigue and cognitive impairment in Post COVID 19 syndrome: A systematic review and meta analysis. Brain Behav Immun. 2022;101:93–135. [CrossRef]

- Crivelli L, Palmer K, Calandri I, Guekht A, Beghi E, Carroll W, et al. Changes in cognitive functioning after COVID 19: A systematic review and meta analysis. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2022;18(5):1047–66. [CrossRef]

- Tavares Júnior JWL, de Souza ACC, Borges JWP, Oliveira DN, Siqueira Neto JI, Sobreira Neto MA, et al. COVID 19 associated cognitive impairment: A systematic review. Cortex. 2022;152:77–97. [CrossRef]

- Ferrucci R, Dini M, Rosci C, Capozza A, Groppo E, Reitano MR, et al. One year cognitive follow up of COVID 19 hospitalized patients. Eur J Neurol. 2022;29(7):2006–14. [CrossRef]

- Miskowiak KW, Johnsen S, Sattler SM, Nielsen S, Kunalan K, Rungby J, et al. Cognitive impairments four months after COVID 19 hospital discharge. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2021;46:39–48. [CrossRef]

- Ollila H, Pihlaja R, Koskinen S, Tuulio Henriksson A, Salmela V, Tiainen M, et al. Long term cognitive functioning is impaired in ICU treated COVID 19 patients: A comprehensive neuropsychological study. Crit Care. 2022;26(1):92. [CrossRef]

- Román F, Calandri IL, Caridi A, Carosella MA, Palma PA, Llera JJ, et al. Consecuencias neurológicas y psiquiátricas a largo plazo (6 meses) en pacientes con COVID leve de la comunidad. J Appl Cogn Neurosci. 2022;3(1):e00264623. [CrossRef]

- Mattioli F, Stampatori C, Righetti F, Sala E, Tomasi C, De Palma G. Neurological and cognitive sequelae of Covid 19: a four month follow up. J Neurol. 2021;268(12):4422–6. [CrossRef]

- Mazza MG, Palladini M, De Lorenzo R, Magnaghi C, Poletti S, Furlan R, et al. Persistent psychopathology and neurocognitive impairment in COVID 19 survivors: Effect of inflammatory biomarkers at three month follow up. Brain Behav Immun. 2021;94:138–47. [CrossRef]

- García Iglesias JJ, Gómez Salgado J, Martín Pereira J, Fagundo Rivera J, Ayuso Murillo D, Martínez Riera JR, Ruiz Frutos C. Impacto del SARS CoV 2 en la salud mental de los profesionales sanitarios: una revisión sistemática. Rev Esp Salud Pública. 2020;94:e202004011.

- Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, Cai Z, Hu J, Wei N, et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(3):e203976. [CrossRef]

- Arnsten AFT, Shanafelt T. Physician distress and burnout: The neurobiological perspective. Mayo Clin Proc. 2021;96(3):763–9. [CrossRef]

- Batra K, Singh TP, Sharma M, Batra R, Schvaneveldt N. Investigating the psychological impact of COVID 19 among healthcare workers: A meta analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(23):9239. [CrossRef]

- Carmassi C, Dell’Oste V, Bui E, Foghi C, Bertelloni CA, Atti AR, et al. The interplay between acute post traumatic stress, depressive and anxiety symptoms among healthcare workers during the COVID 19 emergency. J Affect Disord. 2022;298:209–16. [CrossRef]

- García Gómez M, Gherasim AM, Roldán Romero JM, Montoya Martínez L, Oliva Domínguez J, Escalona López S. COVID 19 related temporary disability in healthcare workers in Spain during the four first pandemic waves. Prev Med Rep. 2024;43:102779. [CrossRef]

- Brickenkamp R, Zillmer E. Test de atención d2 (D2 Test). Madrid: TEA Ediciones; 2002.

- Portellano JA, Martínez-Arias R. TESEN. Test de los senderos para la evaluación de las funciones ejecutivas. Madrid: TEA Ediciones; n.d.

- Reitan, RM. Trail Making Test: manual for administration and scoring. Tucson (AZ): Reitan Neuropsychology Laboratory; 1992.

- Wechsler, D. WAIS-IV: escala de inteligencia de Wechsler para adultos-IV. Madrid: Pearson; 2012.

- Pereña J, Seisdedos N, Corral S, Arribas-Aguila D, Santamaría P, Sueiro M. WMS-III. Wechsler Memory Scale-III (Spanish adaptation). Madrid: Pearson; 2004.

- Wechsler, D. WMS-III: escala de memoria de Wechsler-III. Madrid: Pearson; 2004.

- Jerskey BA, Meyers JE. Rey complex figure test. In: Kreutzer JS, DeLuca J, Caplan B, editors. Encyclopedia of clinical neuropsychology. New York: Springer; 2011. p. 2176–9. [CrossRef]

- Sedó, MA. Five Digit Test (Test de los cinco dígitos). Madrid: TEA Ediciones; 2007.

- Patterson, J. F-A-S test. In: Kreutzer JS, DeLuca J, Caplan B, editors. Encyclopedia of clinical neuropsychology. New York: Springer; 2011.

- Norris G, Tate RL. The Behavioural Assessment of the Dysexecutive Syndrome (BADS): ecological, concurrent and construct validity. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2000;10(1):33–45.

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–13. [CrossRef]

- Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene RE. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Palo Alto (CA): Consulting Psychologists Press; 1970.

- Derogatis, LR. SCL-90-R: administration, scoring and procedures manual-II. Baltimore (MD): Clinical Psychometric Research; 1992.

- Weathers FW, Litz BT, Herman DS, Huska JA, Keane TM. The PTSD checklist (PCL). San Antonio (TX): National Center for PTSD; 1993.

- Seisdedos, N. Manual MBI, inventario burnout de Maslach. Madrid: TEA Ediciones; 1997.

- Carrasco PM, Peña MM, Sueiro MJ. The Memory Failures of Everyday Questionnaire (MFE-30): internal consistency and reliability. Span J Psychol. 2012;15(2):768–76. [CrossRef]

- Pedrero-Pérez EJ, Ruiz-Sánchez de León JM. Quejas subjetivas de memoria, personalidad y sintomatología prefrontal en adultos jóvenes. Rev Neurol. 2013;57(7):289–96.

- Czerwińska A, Pawłowski T. Cognitive dysfunctions in depression – significance, description and treatment prospects. Psychiatr Pol. 2020;54(3):453–66. [CrossRef]

- Diana L, Regazzoni R, Sozzi M, Piconi S, Borghesi L, Lazzaroni E, et al. Monitoring cognitive and psychological alterations in COVID-19 patients: A longitudinal neuropsychological study. J Neurol Sci. 2023;444:120511. [CrossRef]

- Blazhenets G, Schroeter N, Bormann T, Thurow J, Wagner D, Frings L, et al. Slow but evident recovery from neocortical dysfunction and cognitive impairment in a series of chronic COVID-19 patients. J Nucl Med. 2021;62(7):910–15. [CrossRef]

- Cecchetti G, Agosta F, Canu E, Basaia S, Barbieri A, Cardamone R, et al. Cognitive, EEG, and MRI features of COVID-19 survivors: a 10-month study. J Neurol. 2022;269(7):3400–12. [CrossRef]

- Nogueira J, Gerardo B, Santana I, Simões MR, Freitas S. The assessment of cognitive reserve: a systematic review of the most used quantitative measurement methods of cognitive reserve for aging. Front Psychol. 2022;13:847186. [CrossRef]

- Vance DE, Bail J, Enah C, Palmer J, Hoenig A. The impact of employment on cognition and cognitive reserve: implications across diseases and aging. Nurs Res Rev. 2016;6:61–71. [CrossRef]

- Panico F, Luciano SM, Sagliano L, Santangelo G, Trojano L, Vance DE, et al. Cognitive reserve and coping strategies predict the level of perceived stress during COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. Pers Individ Dif. 2022;190:111703. [CrossRef]

- Rock PL, Roiser JP, Riedel WJ, Blackwell AD. Cognitive impairment in depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2014;44(10):2029–40. [CrossRef]

- Lee BEC, Ling M, Boyd L, Olsson C, Sheen J. The prevalence of probable mental health disorders among hospital healthcare workers during COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2023;330:329–45. [CrossRef]

- Bueno Ferrán M, Barrientos-Trigo S. Caring for the caregiver: the emotional impact of the coronavirus epidemic on nurses and other health professionals. Enferm Clin. 2021;31(Suppl 1):S35–S39. [CrossRef]

- Koutsimani P, Montgomery A. Burnout and cognitive functioning: are we underestimating the role of visuospatial functions? Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:775606. [CrossRef]

- Acheson DT, Gresack JE, Risbrough VB. Hippocampal dysfunction effects on context memory: possible etiology for posttraumatic stress disorder. Neuropharmacology. 2012;62(2):674–85. [CrossRef]

- Bakusic J, Schaufeli W, Claes S, Godderis L. Stress, burnout and depression: a systematic review on DNA methylation mechanisms. J Psychosom Res. 2017;92:34–44. [CrossRef]

| Variables | Percentage or Mean (SD) | Group effect | ||

| Control group | COVID-19 group | Statistic t or χ2 | p-value | |

| Age (years) | 44.24 (11.23) | 45.18 (10.49) | - 0.415 | 0.679 |

| Education | 0.393 | 0.822 | ||

| Intermediate Studies (%) | 33.3 | 32.0 | ||

| Advanced Vocational Qualification (%) | 4.8 | 8.0 | ||

| University studies (%) | 61.9 | 60.0 | ||

| Profession | 7.640 | 0.054 | ||

| Physician (%) | 16.7 | 6.0 | ||

| Nurse (%) | 54.8 | 80.0 | ||

| Physiotherapist (%) | 14.3 | 4.0 | ||

| Other (%) | 14.3 | 10.0 | ||

| Time since COVID-19 symptoms (months) | - | 13 (3.82) | ||

| COVID-19 Symptoms | ||||

| Fever (%) | - | 72.0 | ||

| Dry cough (%) | - | 66.0 | ||

| Tiredness (%) | - | 90.0 | ||

| Aches and pains (%) | - | 78.0 | ||

| Sore throat (%) | - | 52.0 | ||

| Diarrhoea (%) | - | 32.0 | ||

| Conjunctivitis (%) | - | 6.0 | ||

| Headache (%) | - | 84.0 | ||

| Loss of smell (%) | - | 70.0 | ||

| Loss of taste (%) | - | 64.0 | ||

| Dysgeusia (%) | - | 34.0 | ||

| Skin rash or loss of pain (%) | - | 14.0 | ||

| Difficulty breathing or feeling short of breath (%) | - | 48.0 | ||

| Chest pain or pressure (%) | - | 46.0 | ||

| Inability to speak or move (%) | - | 8.0 | ||

| Vomiting or nausea (%) | - | 22.0 | ||

| Itchy skin (%) | - | 12.0 | ||

| Feeling dizzy (%) | - | 32.0 | ||

| Syncope (%) | - | 4.0 | ||

| Confusion (%) | - | 10.0 | ||

| Neuropsychological tests | COVID-19 group | Control group | Statistics (df = 1,90) |

| ATTENTION | |||

| D2 test | |||

| Scanning speed | 432.38 (87.494) | 434.83 (81.874) | F=0.018, p=0.895 |

| Scanning accuracy | 170.10 (43.239) | 165.55 (38.952) | F=0.277, p=0.600 |

| Omission | 12.52 (10.300) | 17.31 (14.146) | F=3.516, p=0.064 |

| Commission | 7.90 (4.807) | 2.45 (4.915) | F=1.957, p=0.165 |

| Effectiveness index | 412.48 (82.240) | 406.93 (86.358) | F=0.099, p=0.753 |

| Concentration index | 162.18 (37.307) | 163.10 (40.975) | F=0.013, p=0.911 |

| Max | 36.96 (6.114) | 36.76 (5.656) | F=0.026, p=0.873 |

| Min | 25.14 (7.709) | 24.40 (6.950) | F=0.227, p=0.635 |

| Variation index | 12.04 (4.882) | 12.36 (5.093) | F=0.093, p=0.762 |

| TESEN | |||

| Path 1Execution | 27.01 (7.695) | 28.67 (5.549) | F=1.357, p=0.247 |

| Path 1 Speed | 92.88 (25.749) | 86.21 (20.290) | F=1.849, p=0.177 |

| Path 1 Accuracy | 98.59 (2.840) | 98.98 (2.473) | F=0.499, p=0.482 |

| Path 2Execution | 25.01 (6.653) | 26.56 (6.200) | F=1.305, p=0.256 |

| Path 2 Speed | 99.46 (25.565) | 94.36 (29.597) | F=0.787, p=0.377 |

| Path 2 Accuracy | 98.33 (3.039) | 98.23 (3.553) | F=0.018, p=0.893 |

| Path 3Execution | 18.31 (4.567) | 18.89 (4.371) | F=0.388, p=0.535 |

| Path 3 Speed | 106.54 (36.249) | 99.81 (25.072) | F=1.032, p=0.312 |

| Path 3 Accuracy | 95.96 (10.791) | 95.69 (7.221) | F=0.018, p=0.894 |

| Path 4Execution | 15.88 (19.016) | 14.39 (4.271) | F=0.250, p=0.619 |

| Path 4 Speed | 144.02 (3.759) | 139.19 (40.697) | F=0.027, p=0.555 |

| Path 4 Accuracy | 95.51 (13.201) | 98.04 (3.387) | F=1.468, p=0.229 |

| Total Execution | 19.57 (4.591) | 20.94 (4.24) | F=2.193, p=0.142 |

| Total Speed | 432.81 (128.36) | 418.62 (104.04) | F=0.331, p=0.567 |

| Total Accuracy | 97.54 (4.125) | 97.83 (2.846) | F=0.151, p=0.699 |

| Symbol search | 37.25 (8.411) | 37.78 (8.568) | F=0.084, p=0.773 |

| Number Key | 75.26 (14.151) | 79.36 (17.072) | F=1.585, p=0.211 |

| MEMORY | |||

| Word list I | |||

| Score 1º recall | 6.62 (1.398) | 6.67 (1.509) | F=0.024, p=0.878 |

| Total recall score | 35.80 (5.063) | 36.10 (4.674) | F=0.083, p=0.774 |

| Interference 1 | 0.92 (1.441) | 0.81 (2.027) | F=0.093, p=0.761 |

| Learning | 3.72 (1.371) | 3.95 (1.738) | F=0.514, p=0.475 |

| Interference 2 | 1.14 (1.552) | 1.21 (1.353) | F=0.059, p=0.809 |

| Word list II | |||

| Recall | 9.04 (2.466) | 9.02 (2.342) | F=0.001, p=0.974 |

| Recognition | 23.39 (1.169) | 23.17 (1.305) | F=0.726, p=0.396 |

| Faces I | 40.87 (3.512) | 40.60 (3.787) | F=0.128, p=0.721 |

| Faces II | 102.65 (15.806) | 100.55 (7.765) | F=0.619, p=0.433 |

| Vocabulary | 36.24 (9.317) | 34.00 (9.904) | F=1.246, p=0.267 |

| Rey-Osterrieth complex figure | |||

| Copy | 33.15 (4.136) | 32.77 (3.239) | F=0.229, p=0.633 |

| Copy time | 125.40 (38.970) | 137.52 (43.747) | F=1.975, p=0.163 |

| Recovery | 18.06 (5.985) | 18.45 (6.288) | F=0.094, p=0.760 |

| Recovery time | 109.84 (37.433) | 117.20 (43.584) | F=0.750, p=0.389 |

| EXECUTIVE FUNCTIONS | |||

| FAS Test | |||

| F (Words/min) | 18.04 (4.256) | 19.60 (3.749) | F=3.299, p=0.073 |

| A (Words/min) | 15.76 (4.461) | 16.31 (3.646) | F=0.408, p=0.525 |

| S (Words/min) | 15.18 (4.308) | 15.60 (3.722) | F=0.240, p=0.626 |

| Semantics (Words/min) | 63.18 (11.208) | 66.93 (10.778) | F=2.644, p=0.107 |

| Five-digit test | |||

| Reading | 20.14 (3.417) | 19.74 (3.507) | F=0.308, p=0.580 |

| Counting | 21.88 (3.409) | 21.19 (3.430) | F=0.929, p=0.338 |

| Choosing | 31.96 (5.525) | 30.52 (5.438) | F=1.565, p=0.214 |

| Shifting | 41.30 (8.812) | 39.07 (7.270) | F=1.709, p=0.194 |

| Inhibition | 11.82 (5.054) | 10.95 (5.860) | F=0.582, p=0.448 |

| Flexibility | 21.16 (7.950) | 19.26 (7.398) | F=1.385, p=0.242 |

| Spatial span | |||

| Forward | 8.60 (1.841) | 8.71 (1.672) | F=0.096, p=0.758 |

| Backward | 8.22 (1.962) | 7.95 (1.766) | F=0.465, p=0.497 |

| Total | 17.00 (3.812) | 16.62 (2.946) | F=0.279, p=0.599 |

| Letter-number sequencing | 19.12 (2.344) | 19.69 (2.552) | F=1.247, p=0.267 |

| Digit span | |||

| Forward | 9.00 (1.959) | 8.69 (2.089) | F=0.536, p=0.466 |

| Forward Span | 6.06 (1.168) | 5.93 (1.237) | F=0.274, p=0.602 |

| Backward | 8.28 (2.286) | 8.29 (1.798) | F=0.000, p=0.990 |

| Backward Span | 4.62 (1.244) | 4.67 (1.052) | F=0.037, p=0.848 |

| Increasing | 8.46 (2.279) | 8,79 (2.280) | F=0.466, p=0.496 |

| Increasing Span | 5.84 (1.695) | 6.29 (2.351) | F=1.111, p=0.295 |

| Total | 25.76 (5.286) | 25.76 (4.616) | F=0.000, p=0.999 |

| Similarities | 21.88 (4.914) | 19.93 (4.566) | F=3.838, p=0.053 |

| Key search | 10.80 (3.774) | 11.52 (3.487) | F=0.900, p=0.345 |

| Key search time | 60.42 (61.305) | 58.26 (57.274) | F=0.030, p=0.863 |

| Zoo test Total | 11.10 (3.898) | 11.40 (3.964) | F=0.137, p=0.712 |

| Emotional measures | Covid-19 group | Control group | Statistics (df = 1,90) |

| STAI-State | 25.08 (4.923) | 24.67 (5.664) | F=0.113, p=0.738 |

| STAI-Trait | 26.52 (5.578) | 24.07 (5.110) | F=4.746, p=0.032 |

| PHQ-9 | 8.06 (5.482) | 7.71 (4.994) | F=1.748, p=0.190 |

| MBI | 11.32 (5.156) | 12.05 (6.231) | F=1.079, p=0.541 |

| PCL | 34.58 (11.500) | 34.55 (17.429) | F=0.639, p=0.426 |

| MFE-30 | 14.42 (8.442) | 13.76 (8.678) | F=1.303, p=0.992 |

| ISP-20 | 15.72 (11.644) | 14.76 (12.689) | F=0.057, p=0.812 |

| SCL-90-R | 78.32 (56.750) | 69.50 (64.569) | F=0.008, p=0.927 |

| Somatizations | 1.01 (0.783) | 1.70 (5.025) | F=0.245, p=0.622 |

| Obsessions and compulsions | 1.28 (0.868) | 2.45 (10.078) | F=0.097, p=0.756 |

| Interpersonal sensitivity | 0.84 (0.773) | 0.58 (0.556) | F=0.909, p=0.343 |

| Depression | 1.13 (0.881) | 0.81 (0.768) | F=0.822, p=0.367 |

| Anxiety | 0.69 (0.642) | 0.68 (0.782) | F=0.674, p=0.414 |

| Hostility | 0.68 (0.705) | 0.41 (0.671) | F=1.433, p=0.235 |

| Phobic anxiety | 0.27 (0.426) | 0.32 (0.535) | F=1.618, p=0.207 |

| Paranoid ideation | 0.66 (0.809) | 0.37 (0.562) | F=1.925, p=0.169 |

| Psychoticism | 0.42 (0.620) | 0.26 (0.362) | F=2.988, p=0.141 |

| Global severity index | 0.84 (0.647) | 0.67 (0.628) | F=0.176, p=0.676 |

| Positive discomfort index | 1.66 (0.575) | 1.76 (0.612) | F=3.672, p=0.059 |

| Total positive symptoms | 41.78 (21.076) | 34.02 (23.912) | F=0.856, p=0.357 |

| Emotional tests | STAI State | STAI Trait | PHQ-9 | MBI | PCL | MFE-30 | ISP20 | SCL-90-R |

| Neuropsychological tests | ||||||||

| ATTENTION | ||||||||

| D2 test | ||||||||

| Scanning speed | -,040 | -,023 | ,038 | -,105 | -,131 | ,037 | ,048 | -,086 |

| Scanning accuracy | ,001 | ,005 | ,028 | -,115 | -,080 | ,007 | ,009 | -,068 |

| Omission | -,084 | ,015 | ,005 | -,034 | -,015 | ,101 | ,126 | -,010 |

| Commission | ,002 | ,066 | -,057 | -,038 | ,017 | -,067 | -,044 | -,006 |

| Effectiveness index | ,000 | -,140 | ,061 | -,205* | -,133 | ,009 | ,033 | -,103 |

| Concentration index | ,000 | -,027 | ,057 | -,104 | -,093 | ,040 | ,030 | -,069 |

| Max | -,073 | ,058 | ,141 | -,104 | -,027 | ,113 | ,105 | ,002 |

| Min | -,104 | -,050 | -,101 | -,207* | -,201* | -,137 | -,006 | -,163 |

| Variation index | ,078 | ,137 | ,328** | ,199 | ,273** | ,328** | ,147 | ,249* |

| TESEN | ||||||||

| Sendero 1Execution | -,024 | -,057 | ,008 | -,179 | -,088 | -,123 | -,039 | -,125 |

| Send1 Speed | -,003 | ,086 | ,067 | ,177 | ,113 | ,110 | ,061 | ,132 |

| Send1 Accuracy | ,024 | ,059 | ,092 | ,024 | ,068 | ,013 | -,051 | -,085 |

| Sendero 2Execution | ,031 | -,152 | -,039 | -,188 | -,209* | -,237* | -,145 | -,182 |

| Send2 Speed | -,038 | ,125 | ,037 | ,215* | ,178 | ,176 | ,137 | ,146 |

| Send2 Accuracy | ,134 | -,112 | -,161 | 004 | -,001 | -,093 | -,087 | -,064 |

| Sendero 3Execution | ,027 | -,016 | ,134 | -,053 | ,053 | ,105 | ,018 | -,026 |

| Send3 Speed | -,089 | -,001 | -,091 | ,075 | -,049 | -,080 | ,004 | ,085 |

| Send3 Accuracy | -,038 | -,008 | ,028 | ,064 | ,074 | ,096 | ,079 | ,079 |

| Sendero 4Execution | ,100 | -,035 | ,189 | -,003 | ,151 | ,247* | ,135 | ,118 |

| Send4 Speed | ,046 | ,204* | ,039 | ,275** | ,176 | ,079 | ,169 | ,217* |

| Send4 Accuracy | ,055 | ,050 | ,015 | -,013 | ,010 | -,031 | -,044 | -,068 |

| Total Execution | -,022 | -,128 | ,022 | -,225* | -,124 | -,100 | -,104 | -,168 |

| Total Speed | -,013 | ,121 | ,037 | ,228* | ,133 | ,106 | ,104 | ,183 |

| Total Accuracy | ,031 | ,006 | -,033 | ,032 | ,046 | -,007 | -,042 | -,044 |

| Symbol search | ,121 | -,001 | ,049 | -,053 | -,012 | ,005 | ,051 | ,022 |

| Number Key | ,079 | ,059 | -,048 | ,016 | -,138 | -,076 | -,021 | -,056 |

| MEMORY | ||||||||

| Word list I | ||||||||

| Score 1º recall | -,044 | ,030 | -,043 | -,129 | -,077 | -,147 | -,091 | -,167 |

| Total recall score | -,087 | ,143 | ,078 | ,007 | ,003 | ,003 | ,022 | -,081 |

| Interference 1 | -,130 | -,047 | -,126 | -,175 | -,130 | -,164 | -,100 | -,095 |

| Learning | -,034 | ,126 | ,150 | ,177 | ,064 | ,155 | ,072 | ,097 |

| Interference 2 | -,082 | ,078 | ,112 | ,117 | ,192 | ,043 | ,014 | ,112 |

| Word list II | ||||||||

| Recall | -,010 | ,111 | ,020 | -,007 | -,096 | ,026 | -,026 | -,095 |

| Recognition | ,070 | ,141 | ,167 | ,078 | ,067 | ,184 | ,170 | ,101 |

| Faces I | -,013 | -,006 | ,011 | -,170 | -,112 | ,050 | -,005 | -,036 |

| Faces II | ,031 | ,104 | ,128 | ,130 | ,134 | ,031 | ,060 | ,094 |

| Vocabulary | -,022 | ,048 | -,225* | -,149 | -,183 | -,125 | -,091 | -,242* |

| Rey-Osterrieth complex figure | ||||||||

| Copy | -,179 | -,016 | -,041 | -,036 | -,161 | -,096 | -,110 | -,178 |

| Copy time | -,018 | ,023 | ,026 | ,261* | ,141 | ,064 | -,024 | ,098 |

| Recovery | -,161 | -,155 | -,046 | -,217* | -,294* | -,101 | -,167 | -,261* |

| Recovery time | ,039 | ,090 | -,035 | -,002 | -,016 | -,101 | -,196 | -,127 |

| EXECUTIVE FUNCTIONS | ||||||||

| F-A-S Test | ||||||||

| F (Words/min) | -,007 | -,016 | -,090 | -,042 | -,049 | -,073 | -,058 | -,063 |

| A (Words/min) | -,053 | -,104 | -,168 | -,022 | -,087 | -,012 | -,056 | -,094 |

| S (Words/min) | -,040 | -,092 | -,108 | -,157 | -,114 | -,073 | -,118 | -,170 |

| Semantics (Words/3min) | -,047 | -,098 | -,182 | -,127 | -,217* | -,065 | -,093 | -,209* |

| Five-digit test | ||||||||

| Reading | -,161 | ,043 | ,159 | -,053 | ,138 | -,020 | -,060 | ,047 |

| Counting | -,113 | ,071 | ,188 | -,021 | ,131 | -,029 | -,023 | ,074 |

| Choosing | -,059 | ,068 | ,067 | -,010 | ,065 | ,035 | ,123 | ,063 |

| Shifting | -,036 | -,053 | -,015 | ,056 | ,067 | ,027 | ,049 | ,105 |

| Inhibition | ,066 | ,064 | -,004 | ,067 | ,011 | ,072 | ,177 | ,064 |

| Flexibility | ,027 | -,083 | -,096 | ,070 | -,001 | ,030 | ,074 | ,081 |

| Spatial span | ||||||||

| Forward | -,029 | -,077 | ,030 | -,026 | -,020 | -,040 | ,017 | -,042 |

| Backward | -,064 | -,068 | -,027 | -,279** | -,167 | -,035 | -,114 | -,263* |

| Total | -,030 | -,039 | -,017 | -,186 | -,109 | -,069 | -,038 | -,179 |

| Letter-number sequencing | ,069 | -,092 | ,026 | -,101 | -,074 | ,043 | -,053 | -,116 |

| Digit span | ||||||||

| Forward | ,040 | -,106 | -,156 | -,257* | -,104 | -,098 | -,144 | -,198 |

| Forward Span | ,016 | -,124 | -,221* | -,279** | -,132 | -,132 | -,211* | -,235* |

| Backward | ,011 | -,111 | -,050 | -,110 | -,055 | -,059 | -,084 | -,102 |

| Backward Span | ,024 | -0,97 | -,020 | -,057 | -,047 | -,046 | -,111 | -,095 |

| Increasing | -,081 | -,274** | -,060 | -,159 | -,091 | ,010 | -,048 | -,147 |

| Increasing Span | ,035 | -,240* | -,004 | -,109 | -,017 | ,115 | -,062 | -,074 |

| Total | -,012 | -,209* | -,109 | -,224* | -,106 | -,061 | -,116 | -,190 |

| Similarities | ,071 | -,036 | -,148 | -,063 | -,141 | ,007 | ,047 | -,096 |

| Key search | ,091 | ,068 | -,019 | ,044 | -,108 | ,029 | ,070 | -,056 |

| Key search time | -,154 | -,120 | ,046 | ,056 | ,061 | ,044 | -,042 | ,021 |

| Zoo test Total | ,081 | ,177 | -,007 | ,163 | -,051 | -,125 | ,061 | -,022 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).