Submitted:

21 July 2025

Posted:

22 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

Results

Conclusion

Data Availability

References

- Z. Zhussupova, D. Ayaganov, G. Zharmakhanova, G. Nurlanova, L. Tekebayeva, and A. Mamedbayli, “The influence of movement imitation therapy on neurological outcomes in children who have experienced adverse perinatal conditions,” West Kazakhstan Medical Journal, vol. 66, pp. 331–342, 12 2024.

- S. Houzangbe, M. Lemay, and D. E. Levac, “Towards physiological detection of a “just-right” challenge level for motor learning in immersive virtual reality: a pilot study. (preprint),” JMIR Research Protocols, vol. 13, p. e55730, 12 2023.

- C. L. Kok, C. K. Ho, T. H. Aung, Y. Y. Koh, and T. H. Teo, “Transfer learning and deep neural networks for robust intersubject hand movement detection from eeg signals,” Applied Sciences, vol. 14, no. 17, 2024.

- I. A. Ahmed, E. M. Senan, T. H. Rassem, M. A. H. Ali, H. S. A. Shatnawi, S. M. Alwazer, and M. Alshahrani, “Eye tracking-based diagnosis and early detection of autism spectrum disorder using machine learning and deep learning techniques,” Electronics, vol. 11, p. 530, 02 2022.

- S. Kusuda, Y. Aihara, I. Kusakawa, and S. Hosono, Eds., Handbook of Positional Plagiocephaly. Springer Nature Singapore, 2024.

- S. Agrawal, G. S. N. P., B. K. Singh, G. B., and M. V., “Eeg based classification of learning disability in children using pretrained network and support vector machine,” in Biomedical Engineering Science and Technology, B. K. Singh, G. Sinha, and R. Pandey, Eds. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland, 2024, pp. 143–153.

- M. Qasim and E. Verdu, “Video anomaly detection system using deep convolutional and recurrent models,” Results in Engineering, vol. 18, p. 101026, 2023.

- K. H. H. Aung, C. L. Kok, Y. Y. Koh, and T. H. Teo, “An embedded machine learning fault detection system for electric fan drive,” Electronics, vol. 13, no. 3, 2024.

- H. M. Alyahya, M. M. Ben Ismail, and A. Al-Salman, “Intelligent resnet-18 based approach for recognizing and assessing arabic children’s handwriting,” in 2023 International Conference on Smart Computing and Application (ICSCA), 2023, pp. 1–7.

- J. Li, P. Zheng, and L. Wang, “Remote sensing image change detection based on lightweight transformer and multi-scale feature fusion,” IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing, pp. 1–14, 2025.

- B. Bhavana and S. L.Sabat, “A low-complexity deep learning model for modulation classification and detection of radar signals,” IEEE Transactions on Aerospace and Electronic Systems, pp. 1–10, 2024.

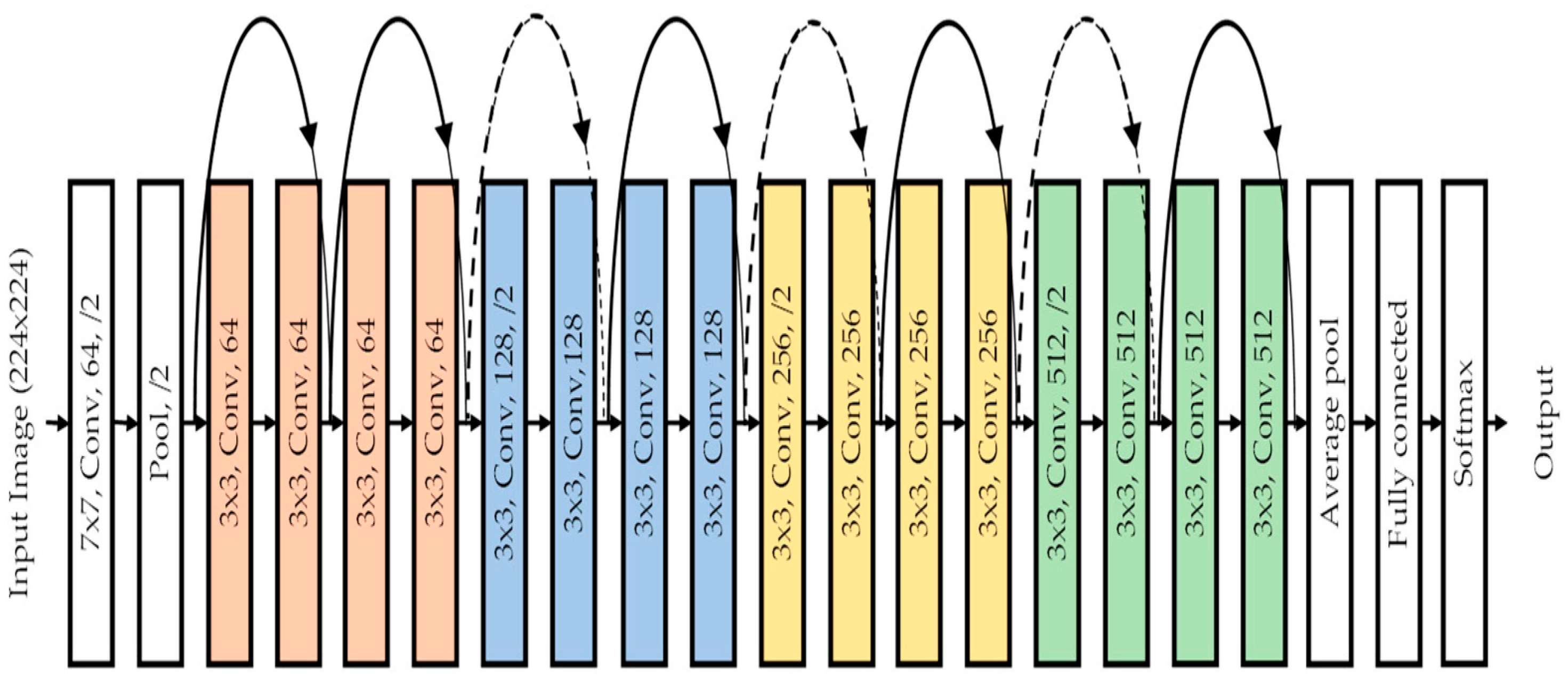

- K. He, X. Zhang, S. Ren, and J. Sun, “Deep residual learning for image recognition,” 2015.

- W. Cheng, “Application and analysis of residual blocks in galaxy classification,” Applied and Computational Engineering, 2023.

- S. Y. B. Mohamed Akrem Benatia, Yacine Amara and A. Hocini, “Block pruning residual networks using multi-armed bandits,” Journal of Experimental & Theoretical Artificial Intelligence, vol. 0, no. 0, pp. 1–16, 2023.

- X. Hu, G. Sheng, D. Zhang, and L. Li, “A novel residual block: replace conv1x1 with conv3x3 and stack more convolutions,” PeerJ Computer Science, vol. 9, p. e1302, 2023.

- K.-L. Chen, C.-H. Lee, H. Garudadri, and B. D. Rao, “Resnests and densenests: Block-based dnn models with improved representation guarantees,” Advances in neural information processing systems, vol. 34, pp. 3413–3424, 2021.

- J. Naranjo-Alcazar, S. Perez-Castanos, I. Martin-Morato, P. Zuccarello, and M. Cobos, “On the performance of residual block design alternatives in convolutional neural networks for end-to-end audio classification,” 2019.

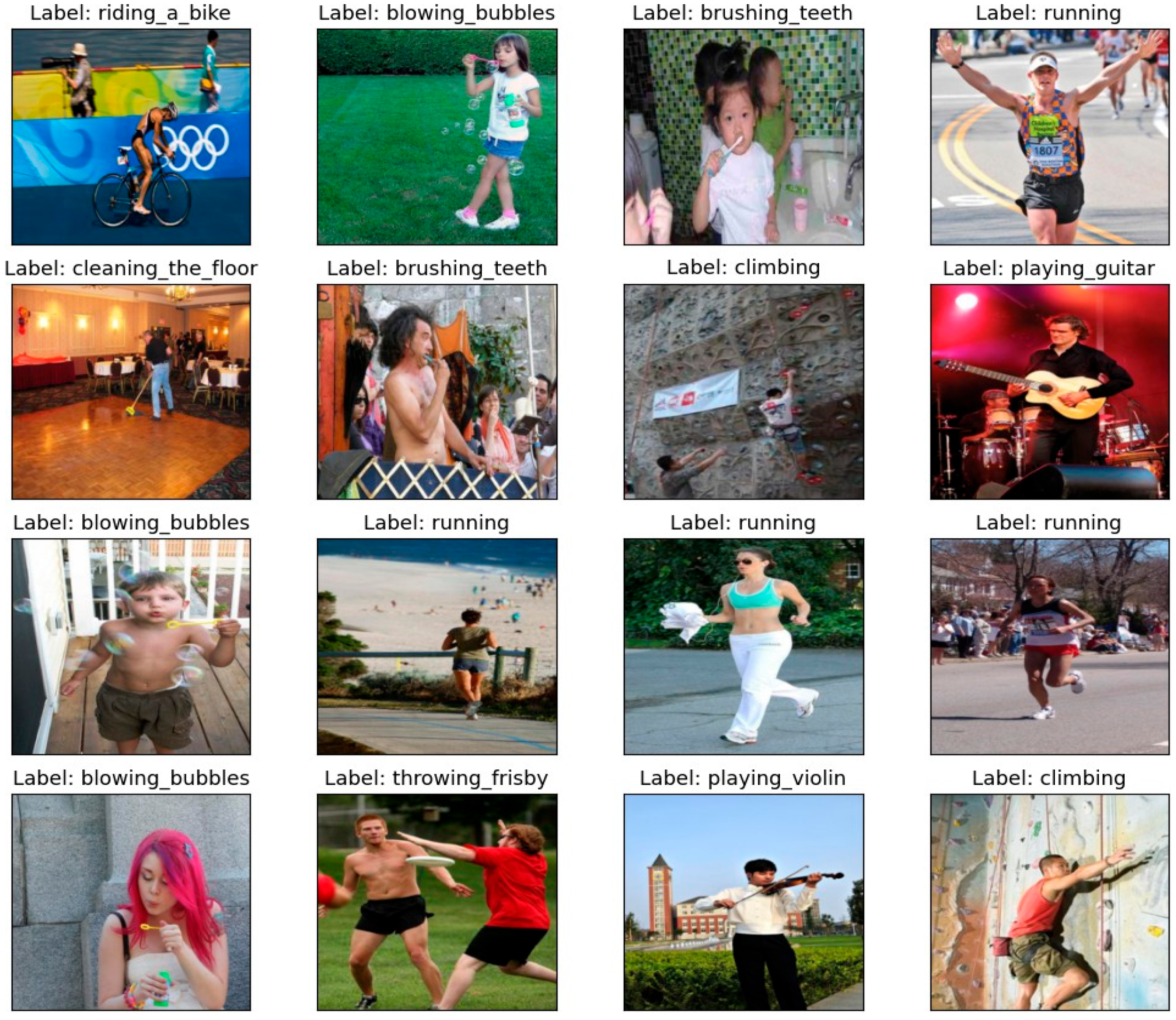

- B. Yao, X. Jiang, A. Khosla, A. L. Lin, L. Guibas, and L. Fei-Fei, “Human action recognition by learning bases of action attributes and parts,” in 2011 International Conference on Computer Vision, 2011, pp. 1331–1338.

- I. Goodfellow, Y. Bengio, and A. Courville, Deep Learning. MIT Press, 2016.

- K. He, X. Zhang, S. Ren, and J. Sun, “Deep residual learning for image recognition,” in Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2016, pp. 770–778.

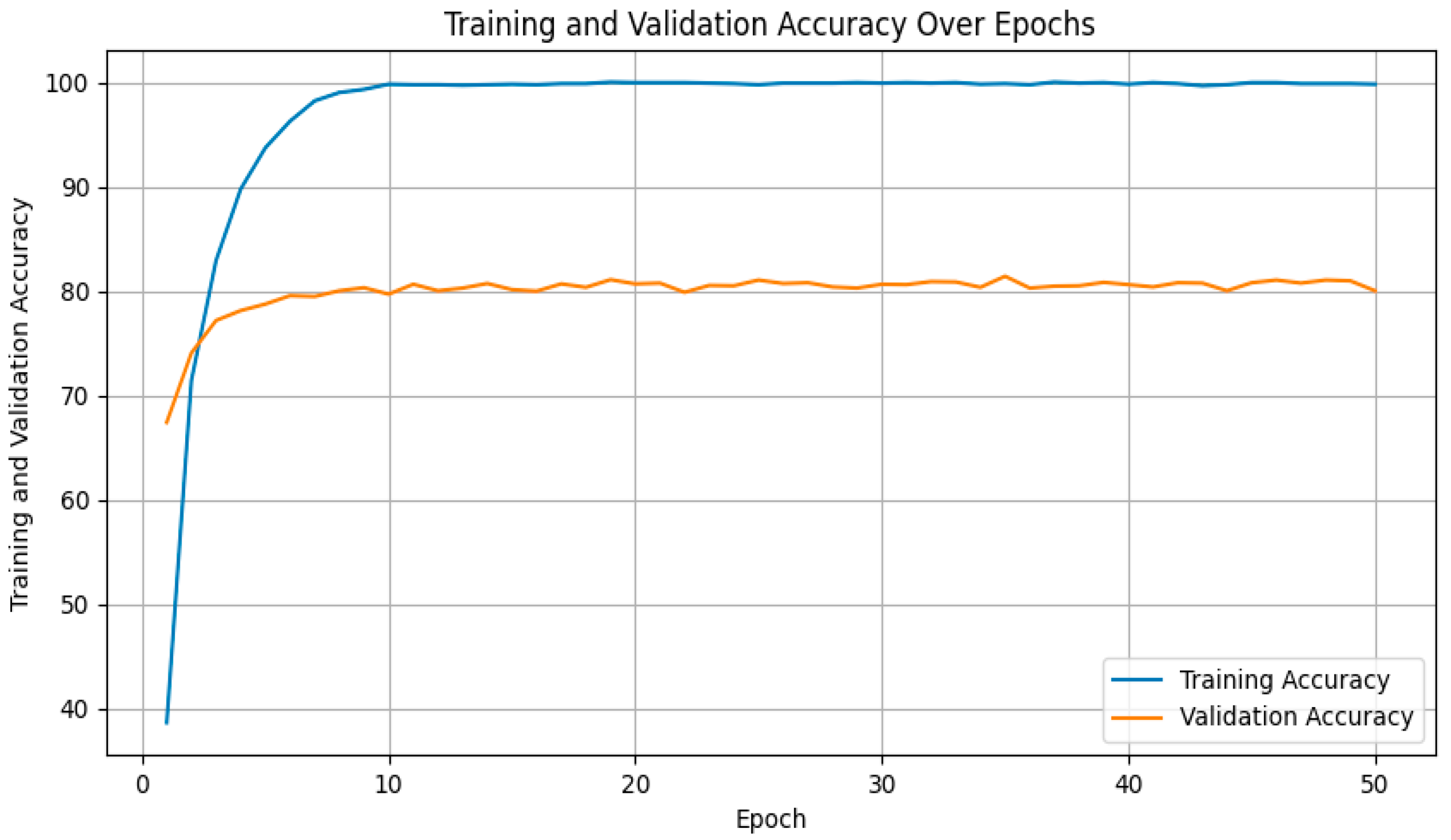

- Y. Bengio, “Practical recommendations for gradient-based training of deep architectures,” in Neural Networks: Tricks of the Trade. Springer, 2012, pp. 437–478.

- C. M. Bishop, Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning. Springer, 2006.

- D. P. Kingma and J. Ba, “Adam: A method for stochastic optimization,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1412.6980, 2014.

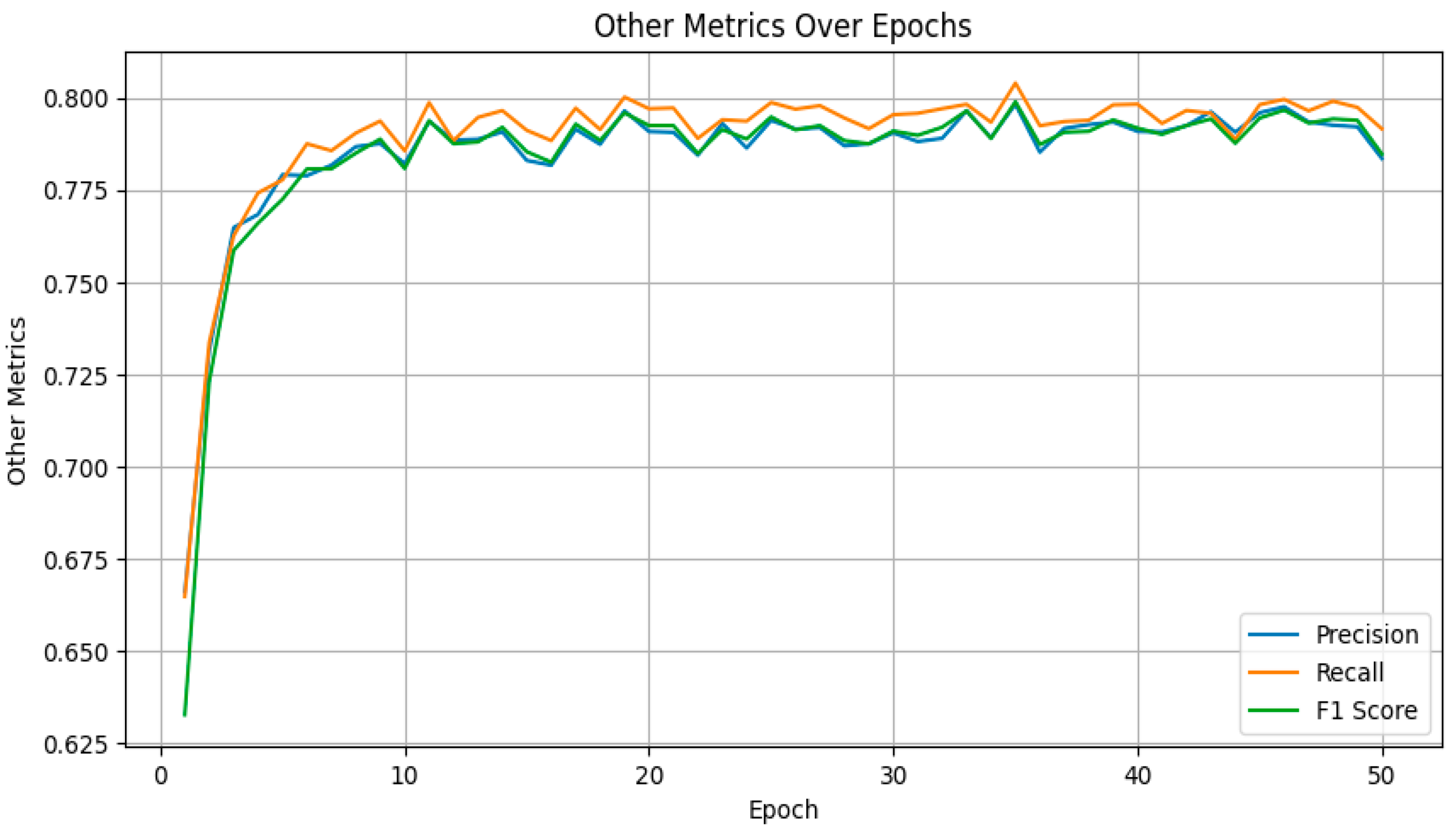

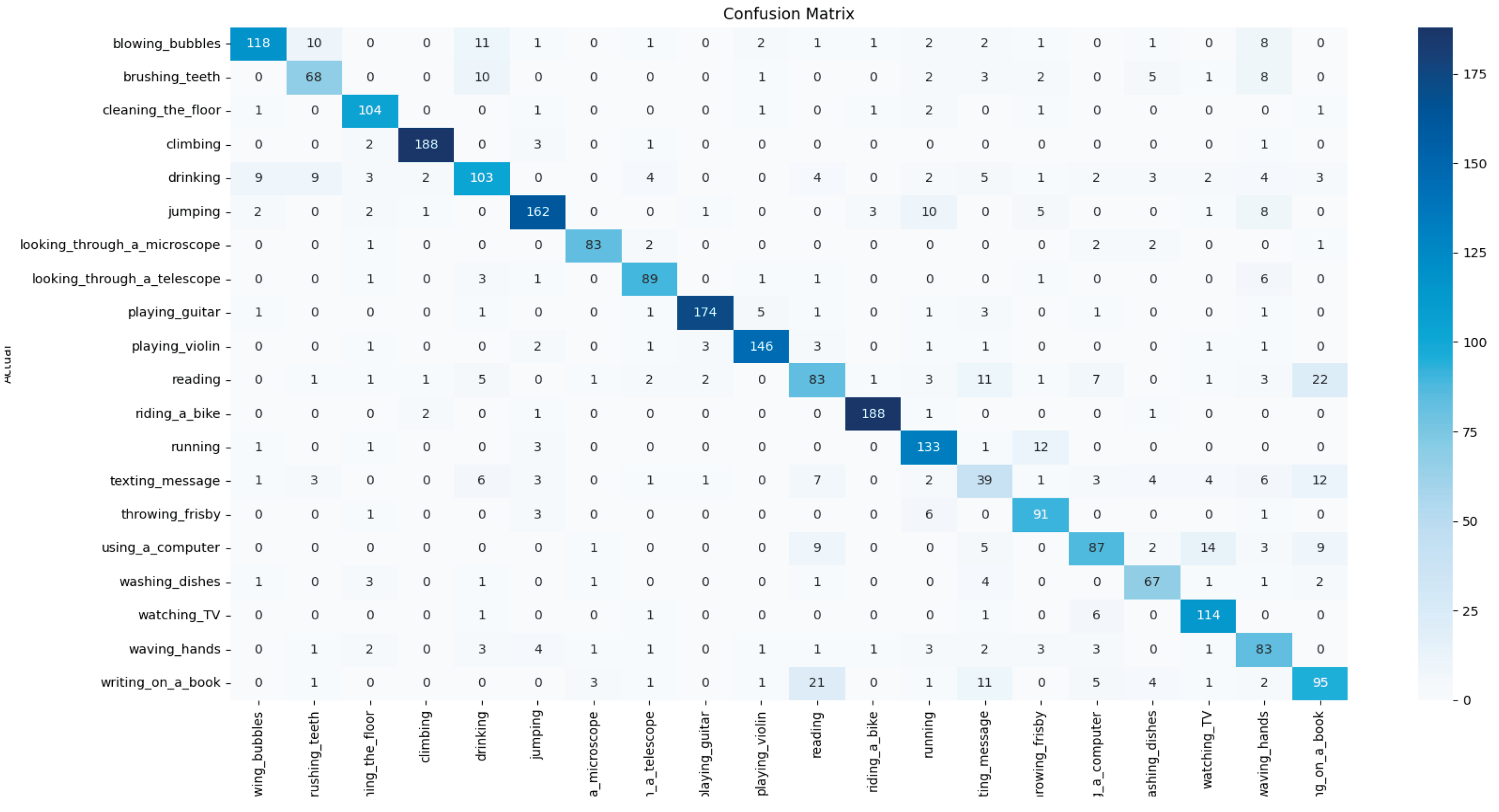

- J. T. Townsend, “Theoretical analysis of an alphabetic confusion matrix,” Perception & Psychophysics, vol. 9, pp. 40–50, 1971.

- L. [Lingxuan, Y. Zejun, M. Zhenwei, and Z. XING], “Method for bearing fault quantitative diagnosis based on mtf and improved residual network,” Journal of Northeastern University (Natural Science), vol. 45, no. 5, pp. 697–706, 2024.

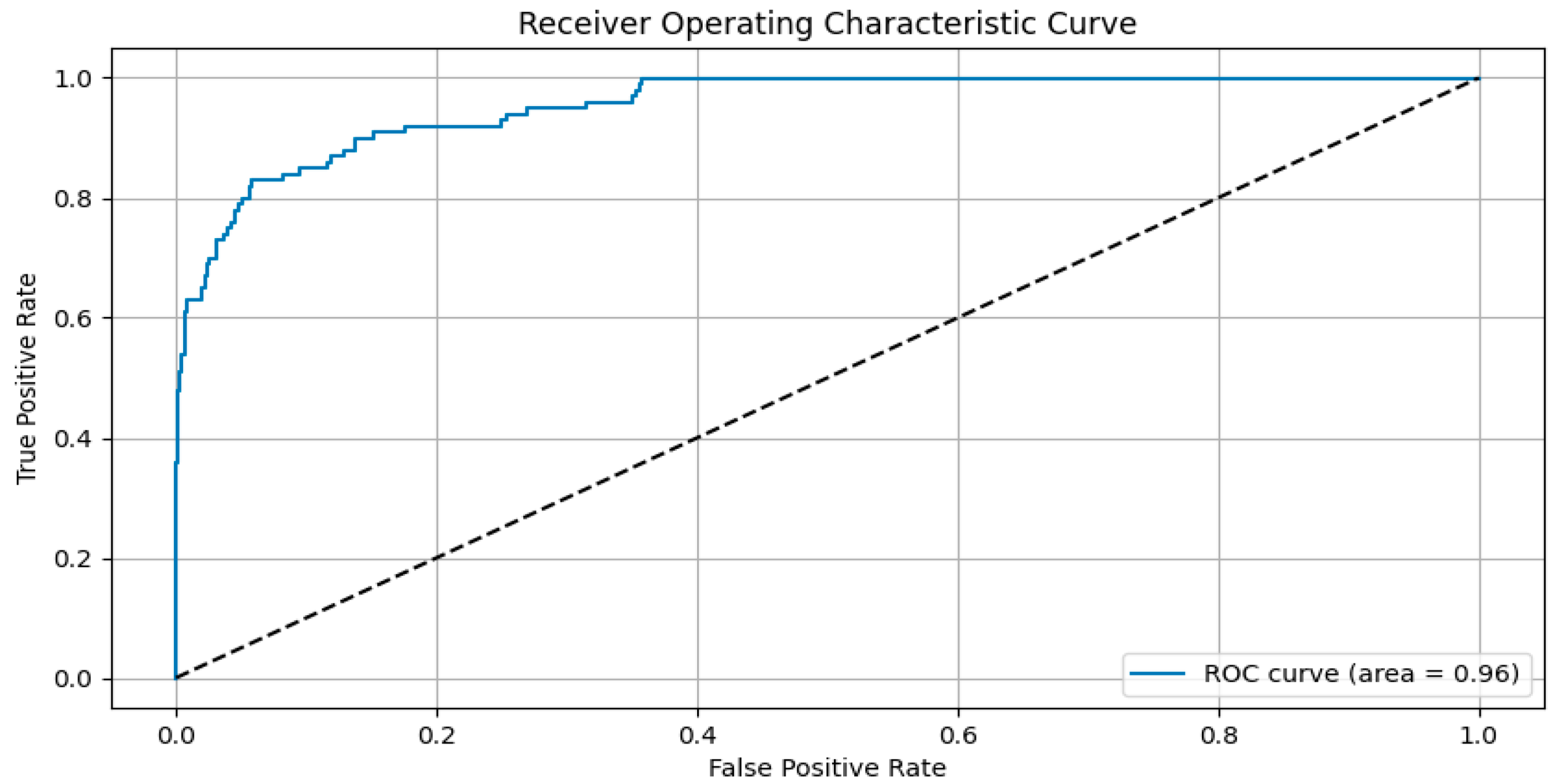

- Z. H. Hoo, J. Candlish, and D. Teare, “What is a roc curve?” Emergency Medicine Journal, vol. 34, no. 6, pp. 357–359, 2017.

- A. Longon, “Interpreting the residual stream of resnet18,” 2024.

- T. Bisla, R. Shukla, M. Dhawan, M. R. Islam, T. Koyasu, K. Teramoto, Y. Kataoka, and K. Horio, “Kid activity recognition: A comprehensive study of kid activity recognition with monitoring activity level using yolov8s algorithms,” in 2024 3rd International Conference on Artificial Intelligence for Internet of Things (AIIoT), 2024, pp. 1–6.

- S. Mohottala, P. Samarasinghe, D. Kasthurirathna, and C. Abhayaratne, “Graph neural network-based child activity recognition,” in 2022 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Technology (ICIT), 2022, pp. 1–8.

- M. Kohli, A. K. Kar, V. G. Prakash, and A. P. Prathosh, “Deep learning-based human action recognition framework to assess children on the risk of autism or developmental delays,” in Neural Information Processing, M. Tanveer, S. Agarwal, S. Ozawa, A. Ekbal, and A. Jatowt, Eds. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore, 2023, pp. 459–470.

- Bosanquet M, Copeland L, Ware R, Boyd R. A systematic review of tests to predict cerebral palsy in young children. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. 2013;55(5):418-426.

- El-Dib M, Massaro AN, Glass P, Aly H. Neurodevelopmental assessment of the newborn: An opportunity for prediction of outcome. Brain and Development. 2011;33(2):95-105.

- Prechtl HFR. Spontaneous motor activity as a diagnostic tool: Functional assessment of the young nervous system. A Scientific Illustration of Prechtl’s Method: GM Trust; 1997.

- Tamboer, P., Vorst, H.C.M., Ghebreab, S., Scholte, H.S.: Machine learning and dyslexia: classification of individual structural neuro-imaging scans of students with and without dyslexia. NeuroImage Clin. 11, 508–514 (2016).

- Al-Barhamtoshy, H.M., Motaweh, D.M.: Diagnosis of Dyslexia using computation analysis. In: 2017 International Conference on Informatics, Health & Technology (ICIHT), pp. 1–7. IEEE.

- Zeiler, M.D., Fergus, R.: Visualizing and understanding convolutional networks. In: Fleet, D., Pajdla, T., Schiele, B., Tuytelaars, T. (eds.) ECCV 2014. LNCS, vol. 8689, pp. 818–833. Springer, Cham (2014).

- J. Liu, B. Kuipers, and S. Savarese. Recognizing human actions by attributes. In CVPR, 2011. 2.

- V. Delaitre, I. Laptev, and J. Sivic. Recognizing human actions in still images: A study of bag-of-features and partbased representations. In BMVC, 2010. 1, 2, 4, 7. 1.

- B. Yao, A. Khosla, and L. Fei-Fei. Combining randomization and discrimination for fine-grained image categorization. In CVPR, 2011. 1.

- P. F. Felzenszwalb, R. B. Girshick, D. McAllester, and D. Ramanan. Object detection with discriminatively trained partbased models. IEEE T. Pattern Anal., 32(9):1627-1645, 2010. 2, 4.

- Wu, Z., Nagarajan, T., Kumar, A., Rennie, S., Davis, L. S., Grauman, K., & Feris, R. (2018). Blockdrop: Dynamic inference paths in residual networks. In Proceedings of the ieee conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA (pp. 8817–8826).

- D. Parikh and K. Grauman. Interactively building a discriminative vocabulary of nameable attributes. In CVPR, 2011. 1, 2.

- G. E. Hinton, N. Srivastava, A. Krizhevsky, I. Sutskever, and R. R. Salakhutdinov Improving neural networks by preventing coadaptation of feature detectors. arXiv:1207.0580, 2012.

- K. Chatfield, V. Lempitsky, A. Vedaldi, and A. Zisserman The devil is in the details: an evaluation of recent feature encoding methods. In BMVC, 2011.

- S. Liu, D. Marinelli, L. Bruzzone, and F. Bovolo, “A review of change detection in multitemporal hyperspectral images: Current techniques, applications, and challenges,” IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Mag., vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 140–158, Jun. 2019.

- G. Montúfar, R. Pascanu, K. Cho, and Y. Bengio On the number of linear regions of deep neural networks. In NIPS, 2014.

- O. Ronneberger, P. Fischer, and T. Brox, “U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation,” in Proc. 18th Int. Conf. Med. Image Comput. Comput.-Assist. Interv., Munich, Germany, 2015, pp. 234–241.

- Y. Jia, E. Shelhamer, J. Donahue, S. Karayev, J. Long, R. Girshick, S. Guadarrama, and T. Darrell Caffe: Convolutional architecture for fast feature embedding. arXiv:1408.5093, 2014.

- I. J. Goodfellow, D. Warde-Farley, M. Mirza, A. Courville, and Y. Bengio Maxout networks. arXiv:1302.4389, 2013.

- C. Yu, H. Li, Y. Hu, Q. Zhang, M. Song, and Y. Wang, “Frequency-temporal attention network for remote sensing imagery change detection,” IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett., vol. 21, 2024, Art. no. 5005305.

- J. Guo, “CMT: Convolutional neural networks meet vision transformers,” in Proc. 2022 IEEE/CVF Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recognit., 2022, pp. 12165–12175.

- A. Alqurashi and L. Kumar, “Investigating the use of remote sensing and GIS techniques to detect land use and land cover change: A review,” Adv. Remote Sens., vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 193–204, 2013.

- Z. Zheng, Y. Zhong, J. Wang, A. Ma, and L. Zhang, “Building damage assessment for rapid disaster response with a deep object-based semantic change detection framework: From natural disasters to man-made disasters,” Remote Sens. Environ., vol. 265, 2021, Art. no. 112636.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).