1. Introduction

The rapid proliferation of mHealth devices and technologies has transformed patient monitoring environments, remote diagnostics, and PHR operations. As healthcare delivery systems increasingly embed pervasive, persistent wearables, smartphones, and other cloud-connected technology into daily practice, the cybersecurity complexity of these environments increases and permeates ever further into our lives. Cybersecurity risks implicate each of the technical paradigms mentioned above. MHealth technological advancements such as smartwatches, track and transmit continuous streams of physiological data stream (heart rate, blood/oxygen level, sleep cycle) that, if compromised, can put people and systems in jeopardy. Current analyses highlight how an exploitable landscape can emerge from the supply chains and firmware designs of wearables, potentially leading to mass exploitation of users and national infrastructures. For example, the new generations of wearables often communicate with smartphones via BLE. Although this technology has been widely adopted, the exploitation or linking of BLE metadata or sensitive biometric signals depends entirely on the device’s hardening measures [

1,

2,

3].

Of note, healthcare systems have been rapidly adopting containerized architectures and microservices for their flexibility and interoperability, aiming to achieve greater scalability. Microservices and container architectures of both healthcare apps and cloud services are a contemporary technology susceptible to exploitation. Similar to wearables, these services and systems have pushed an even wider attack surface, overlapping insecure configurations or building in shared resources or poor isolation mechanisms. A review of studies in the literature recommends using hybridized cloud-edge approaches to balance security, latency, and real-time analytics of data in corporate clinical workflows [

4,

5]. More crucially for growing mHealth systems incorporating PHR and data, controlling access to PHR and encryption are ongoing challenges. While attribute-based encryption (ABE) and multi-authority encryption are a couple of promising paradigms for systemized app data encryption, it is not practical or feasible for real mHealth applications or research to deploy & validate. Likewise, mobile operating systems like Android, which are open-source, have become prime targets for both pre-installed and third-party apps. Notably, a new generation of apps utilizes abusive permissions and persistent background services, infringing on user privacy rights [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12].

The objective of this paper is to design a pragmatic, multi-level audit, and penetration testing process for the PHGL-COVID cloud-based mobile health platform. The PHGL-COVID platform consisted of an mHealth technology prototype in the wild deployed on an application running on a Docker enabled backend, a Samsung Galaxy A55 mobile device, and a Galaxy Watch 7 wearable device—all of which together monitoring a user’s daily experiences; and then audit each server, mobile, and BLE linked components for vulnerabilities on the platforms to identify risks to confidential PHR and platform integrity, while still providing security recommendations to healthcare developers and system integrators [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17].

This paper gives both theoretical grounding and empirical insights based on vulnerable factors observed in mHealth systems.

Section 2 acknowledges recent literature that focuses on potential cyber threats specific to mobile platforms, wearable devices, and container-based healthcare backend systems with a critical review.

Section 3 identifies the PHGL-COVID platform architectural layout and the pertinent entry points where possible cyber attacks could be launched.

Section 4 describes the methodology and toolset applied at different system layers with the focus on transferability and replicability.

Section 5 describes experimental results from the findings. Finally,

Section 6 summarizes the findings and our publication contributions and research opportunities.

2. Background and Related Work

Platforms such as mHealth have evolved into complex ecosystems comprising cloud-based servers, mobile devices, and wearable sensors. These systems are expected to deliver continuous, personalized healthcare services. However, their multilayered design is rarely protected by consistent cybersecurity measures. The heterogeneous nature of these technologies, which range from Android-based smartphones and Wear OS devices to containerized microservice backends, makes it challenging to maintain a consistent and secure baseline. This heterogeneity also has the potential to leak or alter sensitive data or records, such as PHR, sensor streams, and authentication tokens.

Wearable devices are a growing attack vector due to their direct interaction with users’ physiological signals and their tendency to operate autonomously in low-power states. Several studies have shown that even popular wearables transmit biological data, such as heart rate and sleep patterns, over unencrypted BLE channels. These channels are vulnerable to man-in-the-middle and metadata inference attacks. Furthermore, default configurations often expose Generic Attribute Profile (GATT) services without requiring secure pairing or session integrity, which leads to privacy risks in both clinical and non-clinical settings [

18,

19].

Mobile operating systems compound these risks by enabling overprivileged applications and maintaining persistent background services. Android is particularly vulnerable to permission abuse, third-party software development kit (SDK) injection, and firmware modification because it is an open and widely deployed platform in mHealth. Recent analyses propose multi-authority, ABE mechanisms to strengthen data confidentiality, especially in decentralized mHealth contexts. However, practical implementations remain rare or difficult to verify in production environments [

20].

At the backend, the shift toward containerized deployments, such as Docker or Kubernetes-based services, has enabled scalable mHealth infrastructures. However, these platforms often rely on insecure defaults, exposed management interfaces, or outdated libraries. This introduces new vectors for privilege escalation and lateral movement within healthcare data networks. Several authors emphasize the need for zero-trust container orchestration and hybrid cloud-edge deployments to mitigate latency and improve the real-time response to anomalies [

21].

Despite the variety of proposed solutions, most studies focus on one layer, such as wearable BLE encryption, Android permission models, server-side hardening, or simulating threats without validating them against a live system. In contrast, our study aims to bridge this gap by conducting a multi-layered audit covering server, mobile, and wearable components on real-world mHealth deployment. This practical assessment provides insights into the cumulative risk posed by misconfigurations, permission abuse, insecure Bluetooth usage, and fragmented system design across layers.

2.1. Evolution and Emerging Threats of mHealth

MHealth platforms have developed rapidly in complex ecosystems, including cloud-based servers, mobile devices and wearable sensors to give continuous and personal care. However, the multidimensional design of mHealth platforms often complicates the establishment of effective and uniform cybersecurity practices. The involvement of the multiple device types (i.e., classifications of Android smartphones, Wear OS watches, mobile-oriented containerized microservices and backends) prevents the realization of a comprehensive security baseline. The diversity in devices and operational layers increases the risk of leaking or altering sensitive data or PHR.

By design, wearable devices closely interface with users’ physiology, making them an increasingly attractive attack vector. They also generally operate independently and in low-power states. Studies have shown that even most accepted wearables transmit biometric samples (e.g., heart rate, sleep habits) while using BLE and some devices use unencrypted channels for communications, which considering the operation of BLE are obviously open to man-in-the-middle attacks as well as metadata inference attacks. Also, the default setting generally exposes GATT services without notions of secure pairing or session integrity leading ultimately to a loss in privacy from a clinical or non-clinical perspective [

22].

Mobile operating systems take this a step further by not only permitting overprivileged application, but also by generating ongoing and active service environments that run asymmetrically in the background. Android is a poster child in this regard with its permissive platform often enabling the abuse of permissions, third-party SDK injections, and firmware mutability, characteristics that are particularly concerning given its widespread adoption as an open-source mHealth platform. Different methods to maintain data confidentiality include multi-authority, ABE methods, especially in decentralized mHealth implementations while legitimate options are limited with an operational deployment [

23].

With respect to the backend, the rapid movement toward containerized deployments, using Docker and Kubernetes-based microservices, has enabled elastic and scalable mHealth infrastructures over the last ten years. However, Kubernetes container backends typically run with insecure defaults settings, leading to exposures such as vulnerable web management interfaces or outdated package libraries. As with any types of builds, new paths are available for privilege escalation or lateral movement in healthcare data applications through non-terminated continuous systems. Herein, some authors state or express the need for zero-trust container orchestration, and mixed-hybrid cloud-edge DevOps diversity, to eliminate latency, and speed real-time anomaly response integrated workflows [

24].

Ultimately, while many options have been offered, almost all studies are constrained to one layer (e.g., wearables’ BLE encryption, Android permission models, server-side updates, etc.) and document systems of simulated threats without the actual validation of a live system. This study can be seen as addressing this gap relative to a multi-layered audit involving the server, mobile device, and wearable. In fact, the described mHealth deployment represents an example of a comprehensive, all-layer audit. Elements of their practical assessments place practitioners squarely within cumulative risk, clearly demonstrating vulnerabilities caused by misconfiguration, permission abuse, poor Bluetooth device practices, and fundamentally weak system design across all layers.

2.2. Vulnerabilities in Wearables, Android, and BLE

Modern healthcare increasingly depends on mHealth as an essential component. It gives patients with mobile and wearable technologies that provide access, real-time monitoring, and personal diagnostic capabilities. MHealth is growing rapidly in part related to the telehealth shift and the COVID pandemic where patients were subject to logistical, epidemic, and other barriers to non-emergency healthcare. So, more medical institutions, startups, and public health programs are incorporating all parts of domains such as service design, data, decision support, and care data with more mobile-centric products.

While mHealth technology has advanced rapidly, the development of equally robust security measures has lagged behind, offering far fewer safeguards against the aforementioned threats compared to those found in traditional enterprise architectures [

25]. MHealth systems are subject to both explicit and implicit legal protections, which can hinder their ability to detect and mitigate issues related to inconsistent device capabilities, unreliable connectivity, variable sensor processing, and uneven protection as defined by legal or regulatory frameworks. Thus, while mHealth systems can leverage trusted communication channels; some devices do not have the same resilience as others and there exists a reasonable exploitable risk, as there are variable trust boundaries.

Wearable devices have evolved from limited fitness devices to be considered indispensable devices for constant health monitoring with particular emphasis on chronic care and preventive diagnoses. Therefore, integrating wearable devices into clinical workflow practices raises important questions about existing security vulnerabilities. Wearables are often constrained by limited computational resources and communication protocols may have exposable vulnerabilities. BLE, while low power, suffers from poor authentication, initial pairing encryption, and passive eavesdropping susceptibility and active injection attacks [

26,

27].

The GATT, BLE’s functional model for how data is structured and transferred, often has minimal protection against unauthorized access. Various research shows many commercially available wearables expose GATT characteristics without authentication allowing unauthorized third parties to view or modify sensor readings and user metadata. BLE advertisements can leak identifiers (e.g., a device ID) that reveal identifiable information and device capabilities, and when combined with timestamps, they can also expose user specific health patterns. The risks of these vulnerabilities are enhanced within mHealth industry, where the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of data are paramount concerns. These vulnerabilities impact wearables that interact with Android phones and the security concerns surrounding Android phones represent a different security ecosystem. Android’s openness can increase creativity and innovation but also allows third parties to extensively access the system. Many research studies indicate that a significant portion of health-related apps request excessive permissions for accessing system resources, e.g., permission to SMS, location, microphone, and camera with little to no justification of that access [

28,

29].

Some applications, particularly pre-loaded system applications may not even be visible to the user interface but run background services in the OS which have the potential to log user activity, harvest data, or call external servers to run services. Furthermore, firmware fragmentation across Android devices can slow or delay patching. Many users will still be exploitable through publicly disclosed exploits after acknowledging fixes and patches. The most problematic cases are often found in developing regions, where devices run outdated firmware, especially when mobile health platforms are marketed primarily for cost-effectiveness and broad reach, which would be insufficient in more developed contexts. There exists a significant attack surface in mobile health, particularly from the erased trust of end-to-end systems, influenced not only from BLE insecurity and abuse of Android permissions, but repeated firmware lag.

A comprehensive collection of mitigations would imply a directed task-force on specific end user protectability towards mobile health and coordination down the running mobile health chain around BLE session encryption, run-time permissions, firmware integrity, and the habit of behaviorally monitoring system apps and third-party apps. To that end, few mHealth research studies have approached this as a coordinated study across device classes holistically, thus leaving an opportunity for practical multiple-layered security evaluations in a task-based finale as discussed later as a result of this work.

Despite the rapid growth of mobile health technology, the development of effective security frameworks has not kept pace with the risks these systems introduce, especially when compared to traditional enterprise environments. MHealth platforms must contend with device variability, unstable connectivity, limited sensor processing power, and constraints imposed by legal or regulatory requirements. For instance, mobile health systems are not virtual fortresses, and while the channel they are communicating over may be trusted, there are variable trust boundaries among mHealth systems; for example, some devices may not have the same level of protection as others which may make them exploitable risk [

30,

31].

Wearable devices are becoming accepted in the roles from fitness gadgets to valuable tools for continuous monitoring of health (chronic care and preventative diagnosis). This integration of wearable devices in clinical workflows prompts investigations into their security vulnerabilities. Wearable devices typically have limited resource availability, and their communication protocols (i.e., BLE) have clear vulnerabilities. BLE is a low power protocol, however it suffers from poor authentication, lack of pairing encryption, and susceptibility to passive eavesdropping and injection attacks [

32].

To complicate matters further, wearables often communicate with Android-based smartphones, each of which has a separate set of security concerns, being more open than closed. On one hand, Android encourages innovation, but this also enables third-party applications with deep access to the Android platform. Literature suggests that many health-related apps request unnecessary permissions, such as the ability to read SMS, gain user location, access microphone and camera, without proper justification. It is also worth noting that many pre-loaded system apps that do not appear in the user interface may nevertheless run as persistent services that can log activity, harvest data, or communicate with an external server.

Moreover, there is firmware fragmentation across all android devices, each running different security update cycles and patching, leaving many users vulnerable to known exploits or exploits that are publicly disclosed. In developing countries, where much of the population relies on devices running outdated firmware, it is advisable to deploy mobile health platforms carefully, especially when existing platforms already offer cost-effective and wide-reaching solutions. However, BLE insecurity, permission misuse, and firmware lag each contribute to an expanded attack surface and when combined, they undermine end-to-end trust in mHealth systems.

Addressing each issue involves collaborative mitigation, including session encryption, enforcing runtime permissions, firmware integrity checks, and behavioral monitoring of both system and third-party applications. Very few studies have addressed the issue in a comprehensive manner across device classes, specifically, there is a lack of actionability for stakeholders to implement a practical multilayered security assessment as proposed in this research.

2.3. Positioning Our Contribution

As researchers and developers, more papers are being presented from both academia and industry, focusing on security for mHealth systems, each with a limited perspective on some aspects of security (e.g., wearable communication protocols, mobile app permissions, a single cloud server) to their credit. As these papers add valuable information, the nature of the contributions can be limited primarily to only one layer and do not span between the layers or convey the complicated chain of threat scenarios in actual deployments. Additionally, many security assessments are simulated studies, abstract threat modeling, or just static code reviews not verified against an actual operational mHealth platform for comparison.

Several recent studies have identified holistic frameworks for security in mHealth systems where a foundation for multi-layered monitoring with adaptive risk assessments, and coordinated mitigations across devices, networks, and backend services will be included. But such frameworks are typically more theoretical or validated only with modularized testbeds that resemble actual deployments’ complexity, with mHealth paths consisting of Android smartphones, BLE wearables for peripheral linkage, and Docker-based backends for clinical operations [

33,

34].

This paper tries to bridge this gap by undertaking a multi-layered operational security audit on a mHealth prototype called PHGL-COVID. All layers of evaluation included actual device firmware (Samsung Galaxy A55), process evaluations of the BLE linked wearable hardware (Galaxy Watch 7), and a containerized backend infrastructure installed in an actual testing space for pre-clinical trials. This effort focuses on assessing what elements can contribute to creating an in-depth approach to identifying threat, which we claim has never been done before, while bringing different methods together from network scanning to examine application behavior, BLE traffic intercession, and container vulnerability assessments.

The security audit in this paper was designed to assess the security at each layer to not only identify security vulnerabilities located at each layer of security, but also whether misconfigurations, or weaknesses at one layer (e.g., mobile device) impact the interdependencies on the rest of the ecosystem and overall security practice. In summary, the authors believe this to be one of the first evaluations of an mHealth prototype’s security end-to-end, for a cross-platform evidence-based mHealth operational infrastructure.

3. System Architecture and Attack Surface

The prototype PHGL-COVID platform for the collection and assembly of remote health data is designed to enable secure and remote health monitoring with a multi-layered infrastructure consisting of wearable devices, mobile clients based on the Android operating system, and a containerized backend system. Architecturally, PHGL-COVID embodies a real-world use case in which health data such as biological readings, activity logs, and patient identifiers are collected from wearable devices and sent to a health server using mobile intermediary devices. This system was initiated to quickly digitize health services that were already transforming and accelerating before the pandemic and to make health care data services scalable, mobile, and accessible to people living in under-resourced areas of the globe [

35,

36,

37].

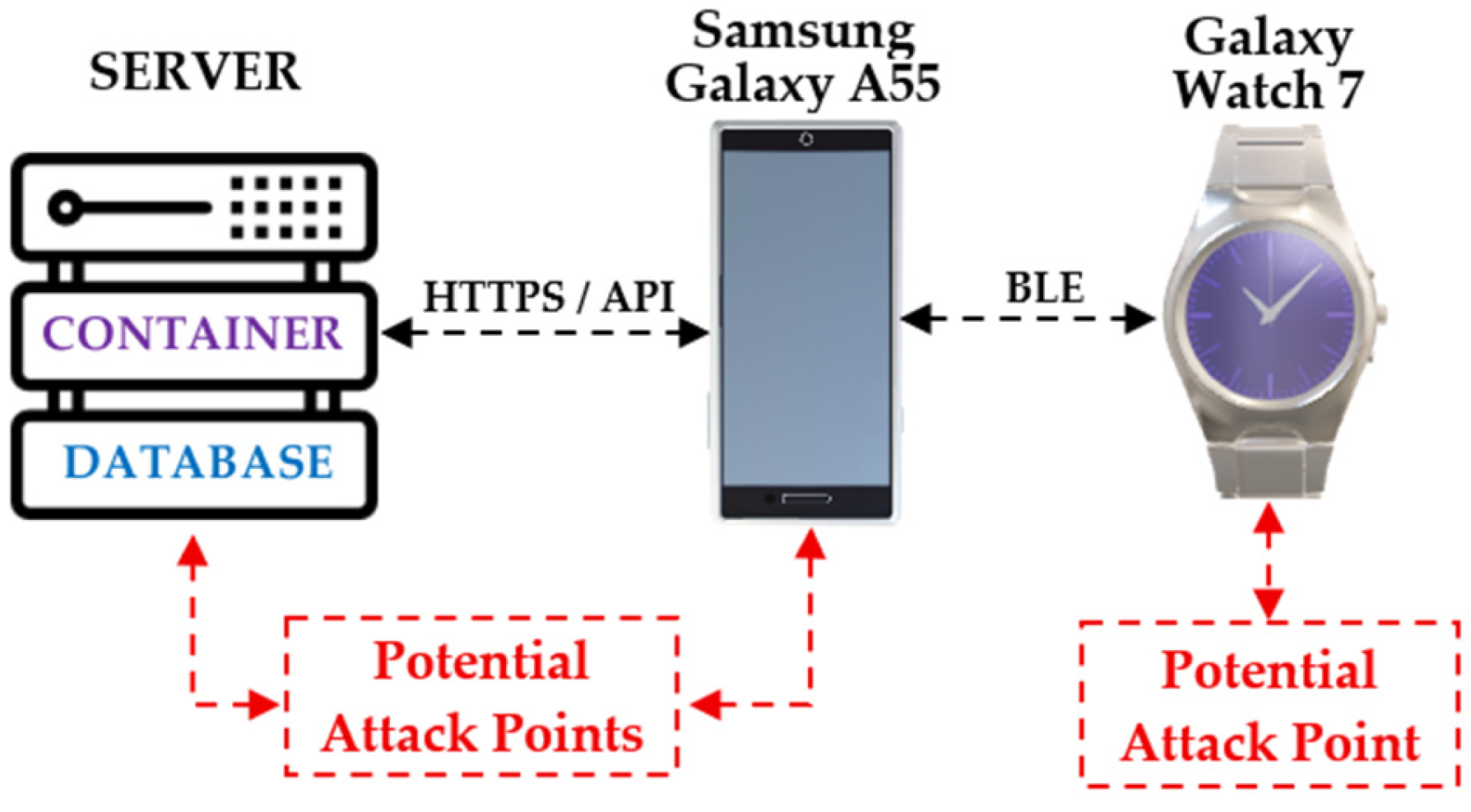

The architecture’s edge is the Samsung Galaxy Watch 7. The Wear OS-based smartwatch captures physiological data, such as pulse, oxygen saturation level, heart rate, and motion pattern, in real-time. The smartwatch communicates with a Samsung Galaxy A55 smartphone via BLE. The Android phone serves as the mobile gateway responsible for aggregating data, executing the PHGL-COVID mobile app, and transmitting data back to the backend via encrypted HTTPS RESTful API calls using Wi-Fi or LTE. The mobile app employs authentication mechanisms such as session tokens, while the data payload is encrypted with AES prior to transmission, which is standard for any mobile SDK [

38,

39,

40].

The backend is deployed as a containerized environment with Docker serving as the isolating technology of essential microservices, such as API endpoints, authentication modules, and database services for electronic health records (EHR) services. The container stack runs on a Linux server (virtual) connected to the Internet. The backend is configured to exposes only essential service ports for EHR image transmission and employs TLS to ensure secure communication. However, its expedited deployment often results in a lack of security auditing, leaving it vulnerable to misconfigurations, deprecated libraries, and insecure service interfaces, particularly those exposing direct endpoints or unprotected mobile APIs [

41,

42,

43].

Each component in the PHGL-COVID system has security risks. For the smartwatch, BLE sniffing and GATT manipulation is possible. For the mobile device, some form of disclosure of unsecured tokens with unwarranted app privileges is possible; or the mobile device runs a variant of compromised firmware. The container back-end could be subject to code injection, privilege escalation, or accidental disclosure based on inadequate isolation of services. The connection between each component, as well as BLE, and API endpoints, may be attacked via man-in-the-middle, payload manipulation, etc. [

44,

45].

Figure 1 illustrates the end-to-end architecture of the PHGL-COV platform, including how the components relate, data flows, trust boundaries, and inter-component communication channels. Each of the three highlighted areas may suffer from inadequate security measures, presenting distinct risks and attack surfaces, demonstrating that devices, communications, and containerized back-ends each have unique security attributes. By applying a network vetting process to the three separates domains (the Device Layer, Communication Layer, and Backend Layer) this assessment identifies the specific security defenses relevant to each, providing a foundation for the layered analysis that follows.

The PHGL-COVID platform is a prototype that was created to allow secure, remote health monitoring as a relatively complex system made up of wearables, mobile client running on Android, and a containerized backend. The architecture simulates a real case where a central healthcare server could have remote and real-time access to health information (physiological readings, activities, and patient identifiers), previously collected for a patient from a wearable device using a mobile gateway. The platform addresses the immediate and urgent need to support newly emerging, rapidly required digital health services developed since the pandemic and is also designed to consider scalability, mobility, and accessibility in low-resourced countries setting [

39,

46].

This comprehensive audit framework demonstrates the increasing complexity of mHealth ecosystems, in which threats can arise not just from discrete endpoints of service delivery, but by integration, interaction, and exchanging data. By focusing on three related layers: wearable, mobile, and server, the framework facilitates both vertical and lateral tracing of vulnerabilities, such as BLE misconfigurations, insecure API authentication, and inappropriate hardening of containerized applications. The processes of packet capture and inspection, application decompilation, and privilege and access review enables the identification of systemic issues which may not be reported as “findings” in the original mobile-only audit. Furthermore, each layer and component was assessed in the context of operational functions: smartwatch during real-time data broadcast of sensors; smartphone in the bridge between encrypted sessions; and backend container under simulated API load. While the intention is to audit the components separately, the layered audit helps identify not only solo misconfigurations, but compounded threats engendered by weak practices of integration across the PHGL-COVID architecture.

4. Methodology

This study adopts a layered auditing methodology designed to evaluate the security posture of the PHGL-COVID platform across its three core components: the wearable device (Galaxy Watch 7), the mobile intermediary (Samsung Galaxy A55), and the containerized backend infrastructure. The assessment combines both manual analysis (configuration inspection, runtime observation, behavioral testing) and automated tools (vulnerability scanners, protocol sniffers, reverse engineering frameworks) to simulate realistic threat scenarios and uncover potential weaknesses [

47].

The evaluation process was divided into four consecutive phases:

Reconnaissance—mapping exposed services, BLE profiles, installed applications, and API endpoints;

Static and dynamic analysis—extracting metadata from firmware and APKs, observing system behaviors and background processes;

Vulnerability testing—active probing using known attack vectors and detection techniques;

Reporting and risk rating—correlating findings across layers and quantifying their potential impact.

Each layer required specific tools adapted to its architecture, privilege model, and interface complexity.

Table 1 summarizes the tools and techniques used throughout the multi-tier audit.

The toolset selected for this audit has been validated in prior literature covering Android security, container vulnerability assessment, and BLE-based communication protocols in wearable devices. However, unlike most works which evaluate layers in isolation, our method emphasizes end-to-end attack surface mapping and the interaction effects across layers [

48,

49,

50,

51,

52].

4.1. Server-Level Audit

A full security audit on the containerized backend infrastructure for the PHGL-COVID platform, which was running on a Linux server, was conducted to gain insight into the resilience against attack. The audit revealed insights into service exposure, container vulnerabilities, and backend misconfiguration, all examined within the context of secure DevOps practices and container orchestration best practices [

53].

The reconnaissance stage, using nmap, discovered all open ports (i.e., 22—SSH, 9090—Zeus Admin, 9500—ISM Server) on the host system. The false assumption made in containerized environments such as mHealth, is that containers insulate processes and exposed services from further attacks downstream. They do not, in fact mHealth is particularly vulnerable due to the presence of services accessible via the internet. The presence of Universal Plug and Play (UPnP) and Admin dashboards exposed to the internet indicates poor network segmentation and insufficient hardening of the infrastructure layer, which is a common theme [

54,

55,

56,

57].

We explored the container vulnerabilities post-deployment using Trivy, an open-source application security scanner that layers CVE feeds with security benchmarks, available to containerized settings. At this stage of the project, we scanned six Docker images corresponding to the various modules, including the Viewer, CRUD, Gateway, and ETL components, as is shown in

Table 2. The Trivy scan produced a total of 613 total vulnerabilities (28 Critical, 103 High) with the most impactful libraries being OpenSSL, SQLite, Kerberos, and libexpat [

58,

59,

60].

Some of the most impactful findings included CVE-2023-45853—a heap-based buffer overflow vulnerability in Zlib affecting decompression routines during back-end processing and API inviting, and CVE-2024-26462—a memory leak vulnerability in the Kerberos authentication module that could enable denial-of-service or persistence-based exploits. While these vulnerabilities have patches available, the fact remains that CVE vulnerabilities, if not patched can compromise confidentiality and attackers can exploit some CVE vulnerabilities for privilege escalation and lateral movement [

61].

To minimize the risk, it is recommended to use hardened base images, stricter container runtime policies, as well as scanning and auditing as part of standardized automated CI/CD pipelines. Further remediation steps aside from rolling out the latest stable releases (i.e., zlib 1.2.14) were to disable UPnP and legacy authentication modules, deploy kernel isolation mechanisms (AppArmor, seccomp profiles), and run the container security tool (Docker Bench) to identify compliance issues against CIS benchmarks. In our audit, this allowed us to point out significant skill gaps for improvement around use of user namespaces, logging and resource quotas.

In contrast to previous work related to containers, which were framed around contexts of change or simulation of change, this security audit was based on a live mHealth deployment. This audit allows us to place operational insights into the propagation of known vulnerabilities under real workflows. Our findings also support the argument that with any form of modularization, periodic and cross-layer audits should be conducted to scrutinize trust boundaries and uncover hidden risks that may not be evident under idealized state configurations [

62].

These findings highlight the systemic risk posed by outdated or poorly maintained third-party libraries embedded in containerized healthcare infrastructures. The presence of critical CVEs in core services, such as zlib, SQLite, and libexpat, some of which have well-documented exploitation vectors in healthcare environments, demonstrates the importance of incorporating automated scanning tools, such as Trivy, directly into CI/CD pipelines. Consistent with previous studies emphasizing the fragility of container isolation in medical data systems, our results highlight the need for continuous patch management, privilege containment, and runtime behavior enforcement in Docker-based mHealth deployments [

63].

4.2. Mobile-Level Audit (Samsung Galaxy A55)

A comprehensive security audit was conducted on the Samsung Galaxy A55 smartphone, which serves as the primary intermediary between wearable devices and the backend server. Due to its dual role of data aggregation and serving as the user interface, the mobile client is a high-value target within the PHGL-COVID architecture. The audit employed static and dynamic techniques using Android Debug Bridge (ADB), system-level dumps (dumpsys, pm list packages, getprop), and reverse engineering frameworks to evaluate risk exposure.

During the reconnaissance phase, ADB was used to enumerate installed applications, inspect system services, and extract device properties. The results revealed a firmware variant specific to a non-European Customer Software Code (CSC), suggesting the use of an unofficial image tailored for a different geographic region. As documented in prior studies, such firmware often lacks timely security updates and may include regional customizations that weaken default sandboxing mechanisms [

64].

Additionally, permission analysis via dumpsys package and MobSF revealed several pre-installed applications with excessive or undocumented permissions, including access to SYSTEM_ALERT_WINDOW, PACKAGE_USAGE_STATS, and location services. Some of these apps were hidden from the user interface and ran persistent background services, which is consistent with previous studies analyzing overprivileged system apps in Android-based mHealth deployments.

The Frida toolkit was used to evaluate dynamic behavior by hooking into selected processes and intercepting API calls. This allowed for the inspection of runtime operations, such as token handling, file access, and Bluetooth stack usage. Several instances were identified where application components accessed insecure shared preferences or retained authentication tokens after sessions had expired. These findings align with prior analyses that identified token leakage and insecure session management as critical attack vectors in mobile medical ecosystems.

Network-level monitoring using Wireshark identified continuous BLE-based communication between the smartphone and the Galaxy Watch 7, including periodic advertisement frames and unencrypted GATT characteristic reads. Although this layer operates outside the main IP stack, it remains accessible to local attackers or malicious apps with Bluetooth permissions, as demonstrated in BLE sniffing attacks outlined in

Section 4.3.

Taken together, the mobile audit revealed that mid-range consumer devices operating under non-standard firmware and loaded with pre-installed opaque apps can introduce significant vulnerabilities into otherwise secure mHealth systems. These risks are amplified by the implicit trust placed in mobile gateways within wearable-cloud infrastructures and highlight the need for strict device baselines, permission auditing, and continuous behavioral monitoring [

65].

4.3. Wearable Device Testing (Galaxy Watch 7)

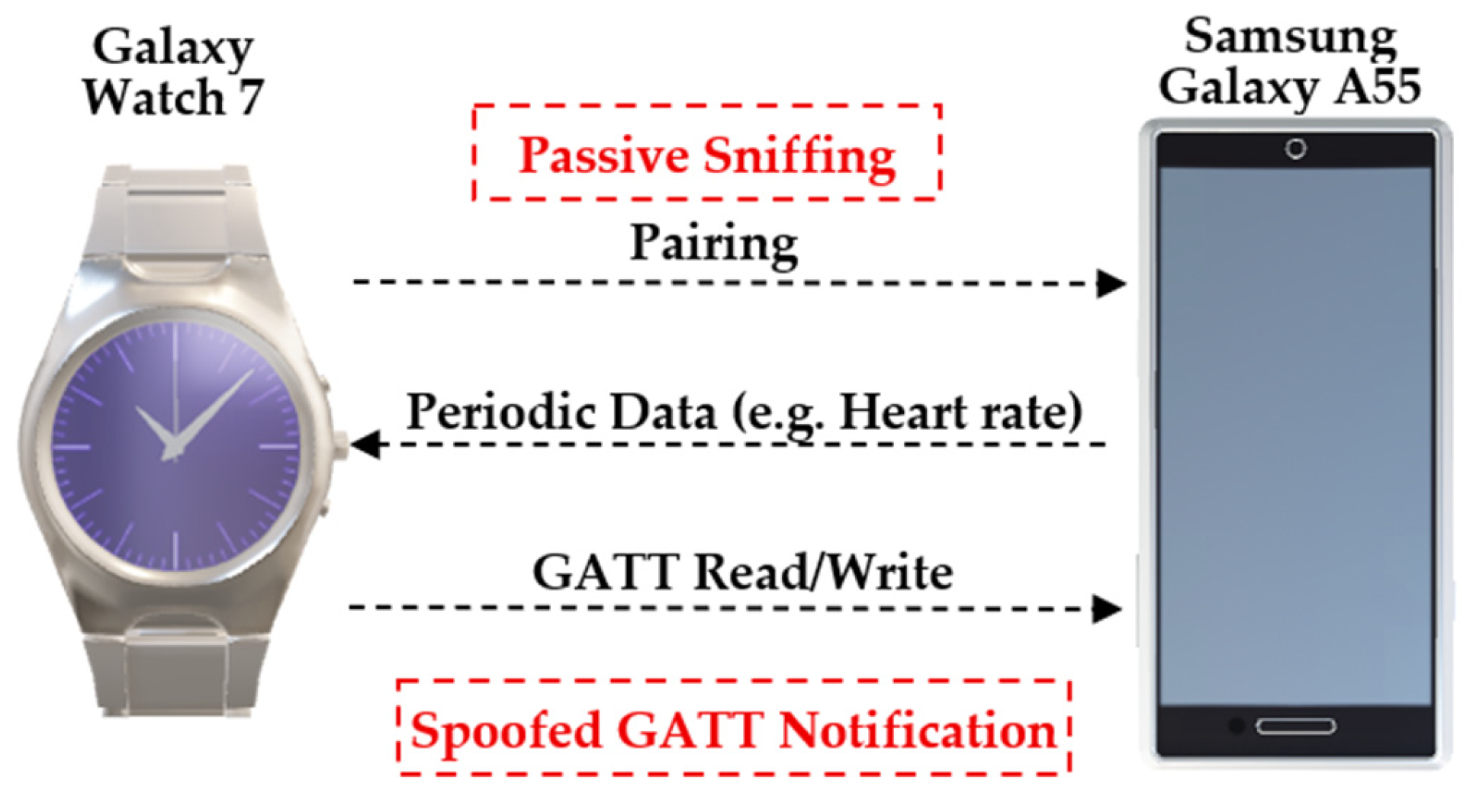

The Galaxy Watch 7 runs Wear OS and plays a central role in the PHGL-COV platform. It collects biometric data, such as heart rate, steps, and oxygen saturation, and relays it to the mobile client via BLE. While this model offers advanced health-tracking capabilities, its permanent Bluetooth pairing and limited UI surface area make it an appealing, yet often overlooked, attack target.

The security audit examined the BLE communication layer, system services on the wearable OS, and interaction patterns with the companion smartphone. Initial pairing and synchronization behaviors were inspected using btmon and hcitool, revealing that several GATT characteristics were exposed without proper encryption or authorization prompts. This enables potential data sniffing or replay attacks, especially in public or shared spaces [

66].

To further the analysis, the nRF Connect tool was used to manually enumerate and read GATT characteristics. Several health-related endpoints (e.g., UUIDs for heart rate, step count, and energy) responded to external BLE clients without rejecting access. As shown in

Table 3, the lack of secure characteristic binding may facilitate unauthorized readouts, particularly in scenarios where BLE advertising is enabled by default.

Runtime inspection via ADB Shell Dumpsys Bluetooth_Manager and Dumpsys Activity revealed constant background services that maintain the BLE connection and push data to the phone approximately every 45 seconds. These services operate without the user’s knowledge and are not restricted to health-specific processes. This creates an expanded attack surface if a rogue mobile client gains pairing status [

67].

Although there weren’t any rooting or bootloader unlocking detected during the audit of the device. The device reported a “green” verified boot state, indicating secure boot, but the potentially problematic permissive SELinux mode (common in Wear OS devices for performance and vendor compatibility reasons), does provide some risk to privilege escalation. And as our audit has shown, even if there is not an explicit compromise, the wearable presents real vulnerabilities into the mHealth ecosystem, particularly when BLE is exposed or unencrypted. The attack surface has expanded beyond mobile, and backend components to the wearable firmware and transitory layers of communication.

Figure 2 illustrates the BLE communication channel between the Galaxy Watch 7 and the Samsung Galaxy A55 smartphone, emphasizing the data flow, connection phases, and associated risk points. The pairing process, periodic data transmission, and GATT-based interactions are all visualized, with specific annotations for attack vectors such as passive sniffing, unauthorized characteristic access, and spoofed notification triggers. This diagram serves to map the real-world BLE behavior observed during our audit and supports a layered threat model that begins at the wearable interface.

As the visual mapping in

Figure 2 reveals, the BLE layer—often overlooked due to its constrained protocol design—plays a pivotal role in shaping the end-to-end security posture of mHealth platforms. Unsecured GATT characteristics and permissive connection policies introduce latent vulnerabilities that can be exploited without physical compromise of the host device, a risk previously underestimated in real-world deployments [

68].

5. Results and Comparative Analysis

This section describes the security audit findings from the three main layers of the PHGL-COV platform: the server-side stack, the mobile mediator, and the wearable endpoint. The audit discovered a range of vulnerabilities including associated outdated system components or unpatched CVEs on containerized services, overprivileged mobile application permissions, and unencrypted Bluetooth communications signals sent to wearable devices.

Instead of analyzing each layer independently, this evaluation explores how the responses of an actor, threat, or adversary can cross architectural boundaries and lead to chains of compound attacks that degrade the confidentiality of the data, disrupt authentication mechanisms and ultimately affect the integrity of the system. By correlating vulnerabilities found across multiple layers, we assess their individual severity, and more importantly, evaluate the compounded impact if exploited sequentially, an often overlooked consideration in mHealth security investigations.

The following subsections provide a layer-by-layer description of the findings and a matrix of these findings in terms of the risk, which estimates the exploitability and likelihood of each threat that was identified. This layer-based analysis demonstrates how decisions made in one layer (for example, wearable communications) can lead to vulnerabilities in another layer (for example, back-end APIs) and illustrates the need for an integrated security solution for all operational layers in mHealth deployments [

52,

53,

54].

5.1. Layered Summary of Findings

A multi-layer audit of the PHGL-COVID platform identified specific and interrelated vulnerabilities at the server backend layer, mobile interface layer, and wearable endpoint layer. Each layer has its own threat profile. Our findings clearly point to several possibilities for risk expansion across boundaries, with loosely coupled or trust-assumed interfaces presenting the most serious concerns moving data from one layer to another.

The server layer and use of defenseless Docker image, which also led to a staggering amount of known CVE’s, 28 critical, impacted libraries such as zlib, libexpat and SQLite. These critical issues are common points of difficulty in containerized healthcare-based deployments where keeping base images up to date is deprioritized with potentially very dangerous consequences, remained susceptible to potential privilege escalation/execution, along with memory corruption exploits. We also identified several exposed ports with legacy protocols such as UPnP all introduced attack surfaces that we neglected to mention because of a purported assumption that the hospital container boundary was a safe network boundary [

55].

The wearable device, Galaxy Watch 7, exhibited vulnerabilities within the BLE communication stack. Multiple health-related GATT characteristics were exposed and significant portions of the BLE communications were available via plaintext BLE sessions with no authenticating barrier. This allowed for passive sniffing and exposure of data, despite secure boot being enabled, the SELinux policy on the system remaining permissive, and BLE advertising being enabled by default. Weaknesses in BLE security were cautiously raised in related literature and it was apparent runtime protections have limited enforcement in Wear OS environments [

57,

58,

62].

The lack of boundary validation between trusted entities (e.g., phone → watch, phone → API) was a repeated finding across layers. That said, while architecture using this assumption is convenient, it is often quickly exploited to chain together low-complexity exploits and create a high-impact breach event and likely situations where health information is compromised.

In the next subsection, we provide a structured comparison of attack vectors, exploitability potential, and mitigation status across layers.

To provide a structured display of vulnerabilities noted across each architectural layer,

Table 4 provides an overview, including important attributes such as attack vectors, estimated likelihood and impact attributes, exploitability potential, and corresponding individual mitigation strategies for locking down the PHGL-COVID platform [

63,

64].

As the comparative matrix shows, the security posture of the PHGL-COVID system cannot be accurately assessed by evaluating individual layers in isolation. Rather, high-confidence exploitation scenarios are enabled by the interplay of moderate-impact vulnerabilities across components, which reinforces the need for unified, cross-layer mitigation strategies.

5.3. Cross-Domain Risk Propagation

While single vulnerabilities have localized effects, it is when the vulnerabilities are successfully exploited against interconnected sequences that they will have their greatest manifestations; thus, this is particularly problematic in multi-layer systems such as PHGL-COVID. In this section, realistic scenarios of cross-domain propagation will be discussed, wherein an attacker could use a single vulnerability in one layer (e.g., wearable) to exploit a higher-privileged layer (e.g., back-end API).

One propagation scenario begins with the Galaxy Watch 7 device, which broadcasts unverified and unencrypted biometric data, not requiring an authentication layer, over its BLE services. An attacker close by can use passive sniffing methods, or they could even spoof GATT notification packets to the Samsung Galaxy A55 device—despite BLE handling, and overprivileged background apps that are secure and verified—the mobile device accepts and processes the data entirely without integrity checks. If the mobile client sends this data to the backend API, the attacker has successfully staged the exploitation again, meaning that he could trigger an injection-based anomaly in the server layer, or bypass the intended service logic on the server [

65,

66,

67,

68].

A second vector is based on user tokens exposed to the mobile layer. As a note, access tokens are observed to persist, in plaintext, even after a session has expired. A local or remote attacker that gains access to the smartphone—via a phishing attempt, malware, or ADB misconfiguration—could reuse these credentials as if they were a legitimate user. Since the server relies on token acceptance, we may see the same propagation and abuse example to the upper levels of the application, and ultimately the server, potentially compromising the endpoints’ associated patient, record, data, or analytics function.

Finally, the components use insecure protocols and allow legacy functionality (e.g., a permissive UPnP network setting on the server, permissive SELinux permissions on the phone and watch), which can support lateral movement. An attacker who compromises a single weak point from either the wearable or mobile layer increases the actors’ privileges, while allowing for a permanent connection to the backend services, further allowing them to take unauthorized actions or make sensitive information available for large scale extraction [

69,

70,

71,

72].

This exploratory example identified a multi-step propagation model showing how even medium-risk findings, with alignment between trust boundaries, can add to compound threat scenarios with an overall critical systemic risk. This addendum reiterates that there is a need for a coherent set of security policies and continuous telemetry around the layers and endpoints in the health data delivery for an organization so that appropriate defense-in-depth actions can be taken at the first compromised layer [

6,

42,

67].

5.4. Interpretation and Real-World Implications

The disclosed vulnerabilities related to PHGL-COVID ecosystem, albeit in a test environment, indicate systemic vulnerabilities noted on many authentic healthcare platforms. In the post pandemic world, mHealth has established itself as the operational backbone of continuous patient monitoring. Each layer exposed from wearable to containerized backend represents not only a technical vulnerability but also a potential source of clinical disruption, legal exposure and patient harm.

First, the BLE breaches identified in the Galaxy Watch 7 demonstrate a common conflict between usability and security. By leaving the physiological characteristics available through unauthenticated reads (ex. heart rate, energy expenditure, etc.) the device allows passive eavesdropping or behavioral profiling especially dangerous in shared environments like hospitals, elder care facilities or fitness clinics. Many adversaries do not require root access or malware to extract identifiable data from a no-device/low-device proximity attack, making wearable communications a high-risk, low-friction attack vector [

73,

74,

75].

On the mobile layer, the persistent access tokens and permissive configuration of firmware layers have more alarming implications. In many contexts smartphones are the de facto identity anchor enabling access to health records, digital prescriptions or remote care’s, giving a compromised device with impersonation authority access to long-term data exfiltration. The BYOD (Bring Your Own Device) healthcare model or public-private telemedicine platform deployed in environments without an administrator provides no recourse or recovery options.

The server-side vulnerabilities, introducing charting edginess from exposed legacy services and updated container images, indicates a larger issue. The transition to microservices and DevOps pipelines in healthcare IT is driven more by efficiency than by security. In this instance, there were over 20 critical CVEs identified in base images running essential services. These are not theoretical vulnerabilities, only those are well documented remotely exploitable conditions with proof-of-concept code available; therefore, the risk of remote code execution denial of service is real and concerning [

76,

77].

Most concerning is the compound risk introduced by the interactions noted between devices. A benign BLE leak can cause erroneous inserted payloads on the smartphone, which could include command injection upon a backend API if it was improperly containerized. This horizontal to vertical command regime is rarely contemplated in mHealth security frameworks, since they seem to treat each type of device or instance as a silo, despite being interdependent chain instances.

Outside of the technical realm, this discloser is serious regulatory and reputational issues. Operating the platform within the European Union or under regulations such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) or the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) requires proper handling of biometric data and session access. Failure to do so may result in fines and legal action. In terms of governance, platforms like PHGL-COVID must provide not only availability and known reliable data but a security context across all device types and protocols involved.

Finally, these findings challenge whether consumer-grade hardware can be safely utilized for medical-grade operations without modification. Whereas wearables and smartphones provide convenience of access, their use in regulated contexts requires a security approach that includes hardening, policy control and continuous auditing before these devices become the weakest link for an otherwise secure environment [

25,

65,

78].

6. Conclusions

This paper provided an in-depth, multi-layer security audit of the PHGL-COVID platform as an mHealth system that intends to include wearable, mobile, and cloud components. Through the use of static analysis, runtime inspection, BLE sniffing, and container vulnerability scanning, we identified systemic vulnerabilities at each level of architecture and illustrated how they could interoperate to execute potential full chain exploitation.

Unlike prior works that consider the mHealth components in silos (e.g., wearables, backends or servers, mobile apps), this study employed a cross-domain threat modeling perspective that examined dependencies between wearable data breaches, mobile token leaks, and server-level misconfigurations. Not only did we discover that there were 28 CVEs, and 12 of them were critical, in 185 containerized images; insecure GATT characteristics found in the Galaxy Watch 7; and Android apps with too much privilege that maintained tokens long past the lifecycle of the associated session, but that all the vulnerabilities were exploitable not only independently, but sequentially to include a full chain exploitation. This exploited scenario included an attacker capturing biometric data over BLE, injecting the data into a device mobile app that had too-high permissions, and then escalated the attack on the servers API, and all done without modification to existing mHealth systems. The identified, and exploited, propagation chain described serious gaps in understandings of pre-existing design assumptions of mHealth systems where trust is often implicitly extended by one device to another without mutual accountability, or privilege boundaries.

When taken from a deployment perspective, the results advocate a considerable architectural rethinking about how security may be enforced across independent but related interfaces. It is no longer sufficient to consider wearables, smartphones, and server-side processes as independent. Healthcare datasets are being created at the domain, or vertical, interfaces: a future mHealth platform will need to architect vertically aligned controls, mutually authenticate across all component interfaces, guard against real-time threats with telemetry, and detect embarrassing anomalies across all interaction layers. Systems need to enforce security controls, such as SELinux, verified boot loading, container hardening, and token lifecycle through semantic as a rule of (not just best) practice; any future and deployment in a clinic, or urgent care setting, should not rely on the assumption that any component of the mHealth system can be trusted to be used in the manner intended.

Finally, regulations should change, across institutions and jurisdictions, to provide explicit guidance regarding the vulnerabilities brought about by repurposing consumer grade hardware, marketed as consumer electronics, for use in medical settings. Outside the manufacturer’s scope and existing legal compliance guidelines, there may be a misconception that compliance equates to resilience.

As works in progress, we have plans to explore real-time attack detection across layers with federated learning techniques, and to prototype a policy enforcement agent that can dynamically modify the behavior of the system, in an informed and contextually aware manner, across all interacting endpoints, moving towards adaptive and contextual awareness security for resource-constrained areas of health sector. Ultimately, ensuring the safety of next generation mHealth systems will require multiple iterations of remedial actions, not only technical solutions, but also a model that reflects systemic shifts with respect to trust, privilege and accountability across every node in the health data digital chain.

This work underscores that the future of mHealth security lies not only in patching individual components, but in reengineering trust itself, treating each layer as both a potential target and a verification point within an ecosystem where medical data integrity, device behavior, and user safety must converge under a unified, adaptive security model.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.M.T. and M.D.; Methodology, E.M.T., S.M., O.G., D.B. and M.P.; Software, E.M.T., S.M., O.G., D.B. and M.P.; Validation, E.M.T., A.D.P., O.G., and D.B.; Investigation, E.M.T., S.M., O.G., D.B. and M.P.; Resources, S.M., O.G., and D.B.; Writing—original draft, E.M.T.; Visualization, E.M.T.; Supervision, M.D., A.D.P. and S.M.; Project administration, E.M.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant of the Ministry of Research, Innovation and Digitization, under the Romania’s National Recovery and Resilience Plan—Funded by EU—NextGenerationEU” program, project “Artificial intelligence-powered personalized health and genomics libraries for the analysis of long-term effects in COVID-19 patients (AI-PHGL-COVID)” number 760073/23.05.2023, code 285/30.11.2022, within Pillar III, Component C9, Investment 8.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ABE |

Attribute-Based Encryption |

| ADB |

Android Debug Bridge |

| BLE |

Bluetooth Low Energy |

| BYOD |

Bring Your Own Device |

| CSC |

Customer Software Code |

| EHR |

Electronic Health Records |

| GATT |

Generic Attribute Profile for BLE |

| GDPR |

General Data Protection Regulation |

| HIPAA |

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act |

| mHealth |

Mobile Health |

| PHR |

Personal Health Records |

| SDK |

Software Development Kit |

| UPnP |

Universal Plug and Play |

References

- B. Konda, A. R. Yadulla, V. K. Kasula, M. Yenugula, and C. Adupa, „Enhancing Traceability and Security in mHealth Systems: A Proximal Policy Optimization-Based Multi-Authority Attribute-Based Encryption Approach”, in 2025 29th International Conference on Information Technology (IT), Feb. 2025, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- H. Alzghaibi, „Barriers to the Utilization of mHealth Applications in Saudi Arabia: Insights from Patients with Chronic Diseases”, Healthcare, vol. 13, no. 6, Art. no. 6, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- P. Shojaei, E. Vlahu-Gjorgievska, and Y.-W. Chow, „Enhancing privacy in mHealth Applications: A User-Centric model identifying key factors influencing Privacy-Related behaviours”, Int J Med Inform, vol. 199, p. 105907, Jul. 2025. [CrossRef]

- H. Alzghaibi, „Healthcare Practitioners’ Perceptions of mHealth Application Barriers: Challenges to Adoption and Strategies for Enhancing Digital Health Integration”, Healthcare, vol. 13, no. 5, Art. no. 5, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- A. Jiménez-Zarco et al., „Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mHealth adoption: Identification of the main barriers through an international comparative analysis”, Int J Med Inform, vol. 195, p. 105779, Mar. 2025. [CrossRef]

- R. K. Ravi, A. Shiva, J. Jacob, P. Baby, B. Pareek, and K. B. V, „Exploring the factors influencing the intention to use mHealth applications in resource scare settings; a SEM analysis among future nurses”, Global Transitions, vol. 7, pp. 199–210, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- K. M. Kezbers, M. C. Robertson, E. T. Hébert, A. Montgomery, and M. S. Businelle, „Detecting Deception and Ensuring Data Integrity in a Nationwide mHealth Randomized Controlled Trial: Factorial Design Survey Study”, J Med Internet Res, vol. 27, p. e66384, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- S. A. Alharthi, „Bridging the Digital Divide in Health for Older Adults: A Repeated Cross-Sectional Study of mHealth in Saudi Arabia”, IEEE Access, vol. 13, pp. 63757–63773, 2025. [CrossRef]

- S. M. S. Islam, A. Singh, S. V. Moreno, S. Akhter, and J. Chandir Moses, „Perceptions of healthcare professionals and patients with cardiovascular diseases on mHealth lifestyle apps: A qualitative study”, Int J Med Inform, vol. 194, p. 105706, Feb. 2025. [CrossRef]

- K. Katsaliaki, S. Kumar, and P. Galetsi, „Patient and societal indicators for mHealth apps’ evaluation using Health Technology Assessment framework”, Technovation, vol. 140, p. 103143, Feb. 2025. [CrossRef]

- J. J. Su et al., „Real-World Mobile Health Implementation and Patient Safety: Multicenter Qualitative Study”, Journal of Medical Internet Research, vol. 27, no. 1, p. e71086, Apr. 2025. [CrossRef]

- J. Alipour, Y. Mehdipour, S. Zakerabasali, and A. Karimi, „Nurses’ perspectives on using mobile health applications in southeastern Iran: Awareness, attitude, and obstacles”, PLoS One, vol. 20, no. 3, p. e0316631, 2025. [CrossRef]

- I. Islomjon and A. Fazliddin, „EFFICIENCY OF MOBILE APPS IN HEALTHCARE: A CASE STUDY OF MED-UZ AI”, Modern American Journal of Medical and Health Sciences, vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 19–24, May 2025.

- S. Siddiqui, A. A. Khan, M. A. Khan Khattak, and R. Sosan, „Mobile Health (m-Health)”, in Connected Health Insights for Sustainable Development: Integrating IoT, AI, and Data-Driven Solutions, Ed., Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland, 2025, pp. 51–68. [CrossRef]

- Insights into the Technological Evolution and Research Trends of Mobile Health: Bibliometric Analysis”. Accessed: Jun 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.mdpi.com/2227-9032/13/7/740.

- P. Geldsetzer, S. Flores, B. Flores, A. B. Rogers, and A. Y. Chang, „Healthcare provider-targeted mobile applications to diagnose, screen, or monitor communicable diseases of public health importance in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review”, PLOS Digital Health, vol. 2, no. 10, p. e0000156, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Krbec et al., „Emerging innovations in neonatal monitoring: a comprehensive review of progress and potential for non-contact technologies”, Front Pediatr, vol. 12, p. 1442753, 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. H. Alsamhi et al., „Federated Learning Meets Blockchain in Decentralized Data Sharing: Healthcare Use Case”, IEEE Internet of Things Journal, vol. 11, no. 11, pp. 19602–19615, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- E. Badidi, „Edge AI for Early Detection of Chronic Diseases and the Spread of Infectious Diseases: Opportunities, Challenges, and Future Directions”, Future Internet, vol. 15, no. 11, Art. no. 11, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Boulemtafes, A. Derhab, and Y. Challal, „Privacy-preserving deep learning for pervasive health monitoring: a study of environment requirements and existing solutions adequacy”, Health Technol (Berl), vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 285–304, 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. Fiorina et al., „Artificial intelligence–based electrocardiogram analysis improves atrial arrhythmia detection from a smartwatch electrocardiogram”, European Heart Journal—Digital Health, vol. 5, no. 5, pp. 535–541, Sep. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Madanian, T. Chinbat, M. Subasinghage, D. Airehrour, F. Hassandoust, and S. Yongchareon, „Health IoT Threats: Survey of Risks and Vulnerabilities”, Future Internet, vol. 16, no. 11, Art. no. 11, Nov. 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. Forsberg and L. Iwaya, „Security Analysis of Top-Ranked mHealth Fitness Apps: An Empirical Study”, 2024.

- „Sensors | Special Issue : Security and Privacy for IoT and Metaverse”. Accessed: Jun 27, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.mdpi.com/journal/sensors/special_issues/security_privacy_IoT_Metaverse.

- M. Anjum, N. Kraiem, H. Min, A. K. Dutta, Y. I. Daradkeh, and S. Shahab, „Opportunistic access control scheme for enhancing IoT-enabled healthcare security using blockchain and machine learning”, Sci Rep, vol. 15, no. 1, p. 7589, Mar. 2025. [CrossRef]

- W. Zhang, J. Xing, and X. Li, „Penetration Testing for System Security: Methods and Practical Approaches”, May 2025, arXiv: arXiv:2505.19174. [CrossRef]

- G. Kołaczek, „Internet of Things (IoT) Technologies in Cybersecurity: Challenges and Opportunities”, Applied Sciences, vol. 15, no. 6, Art. no. 6, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- P. Krawiec, R. Janowski, J. Mongay Batalla, E. Andrukiewicz, W. Latoszek, and C. X. Mavromoustakis, „On providing multi-level security assurance based on Common Criteria for O-RAN mobile network equipment. A test case: O-RAN Distributed Unit”, Computers & Security, vol. 150, p. 104271, Mar. 2025. [CrossRef]

- A .K. B. Arnob, R. R. Chowdhury, N. A. Chaiti, S. Saha, and A. Roy, „A comprehensive systematic review of intrusion detection systems: emerging techniques, challenges, and future research directions”, Journal of Edge Computing, vol. 4, no. 1, May 2025. [CrossRef]

- T. Mirzoev, M. Miller, S. Lasker, and M. Brannon, „Mobile Application Threats and Security”, Feb. 2025, arXiv: arXiv:2502.05685. [CrossRef]

- A .Alanda, D. Satria, H. A. Mooduto, and B. Kurniawan, „Mobile Application Security Penetration Testing Based on OWASP”, IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, vol. 846, p. 012036, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Bojjagani and V. Sastry, VAPTAi: A Threat Model for Vulnerability Assessment and Penetration Testing of Android and iOS Mobile Banking Apps. 2017, p. 86. [CrossRef]

- V. Singla, A. Singh, and G. Bhathal, „Navigating blockchain-based clinical data sharing: An interoperability review”, 2024, pp. 402–408. [CrossRef]

- „Edge Computing in Healthcare: Innovations, Opportunities, and Challenges”. Accessed: Jun 28, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.mdpi.com/1999-5903/16/9/329.

- Patil et al., „Federated Learning in Real-Time Medical IoT: Optimizing Privacy and Accuracy for Chronic Disease Monitoring”, Journal of Electrical Systems, vol. 19, no. 3, Art. no. 3, 2023. [CrossRef]

- K. Davis and T. Ruotsalo, „Physiological Data: Challenges for Privacy and Ethics”, Computer, vol. 58, no. 1, pp. 33–44, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- B. Martínez-Pérez, I. de la Torre-Díez, and M. López-Coronado, „Privacy and security in mobile health apps: a review and recommendations”, J Med Syst, vol. 39, no. 1, p. 181, Jan. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Ravinder, M. Khan, and J. Singh, „Security Challenges in Mobile Cloud Computing”, 2024, p. 9. [CrossRef]

- U. Zaman, Imran, F. Mehmood, N. Iqbal, J. Kim, and M. Ibrahim, „Towards Secure and Intelligent Internet of Health Things: A Survey of Enabling Technologies and Applications”, Electronics, vol. 11, no. 12, Art. no. 12, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- G. Özsezer and Ş. Dağhan, „Effectiveness of wearable technologies used in the monitoring of cardiovascular diseases in the community: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials”, Computers in Biology and Medicine, vol. 189, p. 110013, May 2025. [CrossRef]

- S. Messinis, N. Temenos, N. E. Protonotarios, I. Rallis, D. Kalogeras, and N. Doulamis, „Enhancing Internet of Medical Things security with artificial intelligence: A comprehensive review”, Computers in Biology and Medicine, vol. 170, p. 108036, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- P. Xi, X. Zhang, L. Wang, W. Liu, and S. Peng, „A Review of Blockchain-Based Secure Sharing of Healthcare Data”, Applied Sciences, vol. 12, no. 15, Art. no. 15, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. N. Alruwaill, S. P. Mohanty, and E. Kougianos, „hChain 4.0: A Secure and Scalable Permissioned Blockchain for EHR Management in Smart Healthcare”, May 20, 2025, arXiv: arXiv:2505.13861. [CrossRef]

- D. A. P. Subiramaniyam N. P., „IoT-Enabled Smart Health Monitoring System with Deep Learning Models for Anomaly Detection and Predictive Health Risk Analytics Integrated with LoRa Technology”, International Journal of Engineering Trends and Technology—IJETT, Accessed: Jun 28, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://ijettjournal.org/, https://ijettjournal.org//archive/ijett-v73i1p102.

- D. Farahmandazad and K. Danesh, „ML-Driven Approaches to Combat Medicare Fraud: Advances in Class Imbalance Solutions, Feature Engineering, Adaptive Learning, and Business Impact”, Feb. 21, 2025, arXiv: arXiv:2502.15898. [CrossRef]

- M. Mohammadi, R. Javan, M. Beheshti-Atashgah, and M. R. Aref, „SCALHEALTH: Scalable Blockchain Integration for Secure IoT Healthcare Systems”, Mar. 12, 2024, arXiv: arXiv:2403.08068. [CrossRef]

- U. Zaman, Imran, F. Mehmood, N. Iqbal, J. Kim, and M. Ibrahim, „Towards Secure and Intelligent Internet of Health Things: A Survey of Enabling Technologies and Applications”, Electronics, vol. 11, no. 12, Art. no. 12, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Wang, S. Wang, and Y. Zhang, „Deep learning on medical image analysis”, CAAI Transactions on Intelligence Technology, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 1–35, 2025. [CrossRef]

- H. F. Atlam and Y. Yang, „Enhancing Healthcare Security: A Unified RBAC and ABAC Risk-Aware Access Control Approach”, Future Internet, vol. 17, no. 6, Art. no. 6, Jun. 2025. [CrossRef]

- H. Zhao, D. Sui, Y. Wang, L. Ma, and L. Wang, „Privacy-Preserving Federated Learning Framework for Multi-Source Electronic Health Records Prognosis Prediction”, Sensors, vol. 25, no. 8, Art. no. 8, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. Queipo, J. Barbado, A. M. Torres, and J. Mateo, „Approaching Personalized Medicine: The Use of Machine Learning to Determine Predictors of Mortality in a Population with SARS-CoV-2 Infection”, Biomedicines, vol. 12, no. 2, p. 409, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Rahmati, „Towards Explainable and Lightweight AI for Real-Time Cyber Threat Hunting in Edge Networks”, Apr. 18, 2025, arXiv: arXiv:2504.16118. [CrossRef]

- I. Pekaric, C. Sauerwein, S. Laichner, and R. Breu, „How Do Mobile Applications Enhance Security? An Exploratory Analysis of Use Cases and Provided Information”, Apr. 19, 2025, arXiv: arXiv:2504.14421. [CrossRef]

- G. Olson et al., „The Impact of AI on the Development of Multimodal Wearable Devices in Musculoskeletal Medicine”, HSS Journal, Jun. 2025. [CrossRef]

- N. Kaur et al., „Securing fog computing in healthcare with a zero-trust approach and blockchain”, EURASIP Journal on Wireless Communications and Networking, vol. 2025, no. 1, p. 5, Feb. 2025. [CrossRef]

- S. Inshi, R. Chowdhury, H. Ould-Slimane, and C. Talhi, „Secure Adaptive Context-Aware ABE for Smart Environments”, IoT, vol. 4, no. 2, Art. no. 2, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Mekruksavanich and A. Jitpattanakul, „Wearable Sensor-Based Behavioral User Authentication Using a Hybrid Deep Learning Approach with Squeeze-and-Excitation Mechanism”, Computers, vol. 13, no. 12, Art. no. 12, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Kapsecker and S. M. Jonas, „Cross-device federated unsupervised learning for the detection of anomalies in single-lead electrocardiogram signals”, PLOS Digital Health, vol. 4, no. 4, p. e0000793, Apr. 2025. [CrossRef]

- V. Vakhter, B. Soysal, P. Schaumont, and U. Guler, „Security for Emerging Miniaturized Wireless Biomedical Devices: Threat Modeling with Application to Case Studies”, IEEE Internet Things J., vol. 9, no. 15, pp. 13338–13352, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. M. Ali et al., „Wearable and Flexible Sensor Devices: Recent Advances in Designs, Fabrication Methods, and Applications”, Sensors, vol. 25, no. 5, Art. no. 5, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Akif, I. Butun, A. Williams, and I. Mahgoub, „Hybrid Machine Learning Models for Intrusion Detection in IoT: Leveraging a Real-World IoT Dataset”, Feb 17, 2025, arXiv: arXiv:2502.12382. [CrossRef]

- P. Kasralikar, O. R. Polu, B. Chamarthi, R. Veer Samara Sihman Bharattej Rupavath, S. Patel, and R. Tumati, „Blockchain for Securing AI-Driven Healthcare Systems: A Systematic Review and Future Research Perspectives”, Cureus, vol. 17, no. 4, p. e83136, Apr. 2025. [CrossRef]

- D. Guy et al., „Contact tracing strategies for infectious diseases: A systematic literature review”, PLOS Global Public Health, vol. 5, no. 5, p. e0004579, May 2025. [CrossRef]

- D. Martins, S. Lewerenz, A. Carmo, and H. Martins, „Interoperability of telemonitoring data in digital health solutions: a scoping review”, Front. Digit. Health, vol. 7, Apr. 2025. [CrossRef]

- T. Riahi, M. A. H. Bappy, and M. M. Islam, „ElderFallGuard: Real-Time IoT and Computer Vision-Based Fall Detection System for Elderly Safety”, May 17, 2025, arXiv: arXiv:2505.11845. [CrossRef]

- A. Osa Sanchez, J. Ramos-Martinez-de-Soria, A. Mendez-Zorrilla, I. Ruiz, and B. Zapirain, „Wearable Sensors and Artificial Intelligence for Sleep Apnea Detection: A Systematic Review”, Journal of Medical Systems, vol. 49, May 2025. [CrossRef]

- G. Starke et al., „Finding Consensus on Trust in AI in Health Care: Recommendations From a Panel of International Experts”, J Med Internet Res, vol. 27, p. e56306, Feb. 2025. [CrossRef]

- W. Cho, S. A. Immanuel, J. Heo, and D. Kwon, „Fourier-Modulated Implicit Neural Representation for Multispectral Satellite Image Compression”, Jun 11, 2025, arXiv: arXiv:2506.01234. [CrossRef]

- K. Al-hammuri, F. Gebali, and A. Kanan, „ZTCloudGuard: Zero Trust Context-Aware Access Management Framework to Avoid Medical Errors in the Era of Generative AI and Cloud-Based Health Information Ecosystems”, AI, vol. 5, no. 3, Art. no. 3, Sep. 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. Kim et al., „Toward Robust Security Orchestration and Automated Response in Security Operations Centers with a Hyper-Automation Approach Using Agentic AI”, Feb. 27, 2025, Preprints: 2025022134. [CrossRef]

- M. Kaya and H. Shahid, „Cross-Border Data Flows and Digital Sovereignty: Legal Dilemmas in Transnational Governance”, Interdisciplinary Studies in Society, Law, and Politics, vol. 4, no. 2, Art. no. 2, Apr. 2025. [CrossRef]

- T.-C. Wu and C.-T. Ho, „Reconstructing Risk Dimensions in Telemedicine: Investigating Technology Adoption and Barriers During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Taiwan”, Journal of Medical Internet Research, vol. 27, no. 1, p. e53306, Feb. 2025. [CrossRef]

- A. Girma and A. Barrett, „Security Challenges and Solutions in 5G-Enabled IoT Networks”, 2024, pp. 632–643. [CrossRef]

- G. Wang, S. Shanker, A. Nag, Y. Lian, and D. John, „ECG Biometric Authentication Using Self-Supervised Learning for IoT Edge Sensors”, IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform., vol. 28, no. 11, pp. 6606–6618, Nov. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Allouzi and J. Khan, „Enabling Zero Trust Security in IoMT Edge Network”, Feb. 16, 2024, arXiv: arXiv:2402.10389. [CrossRef]

- S. Bose and D. Marijan, „Secure Traversable Event logging for Responsible Identification of Vertically Partitioned Health Data”, Nov. 28, 2023, arXiv: arXiv:2311.16575. [CrossRef]

- T. Hama et al., „Enhancing Patient Outcome Prediction Through Deep Learning With Sequential Diagnosis Codes From Structured Electronic Health Record Data: Systematic Review”, Journal of Medical Internet Research, vol. 27, no. 1, p. e57358, Mar. 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. J. T. Tan and P. V. Benos, „Addressing Intersectionality, Explainability, and Ethics in AI-Driven Diagnostics: A Rebuttal and Call for Transdiciplinary Action”, Jan 15, 2025, arXiv: arXiv:2501.08497. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).