Submitted:

21 July 2025

Posted:

22 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

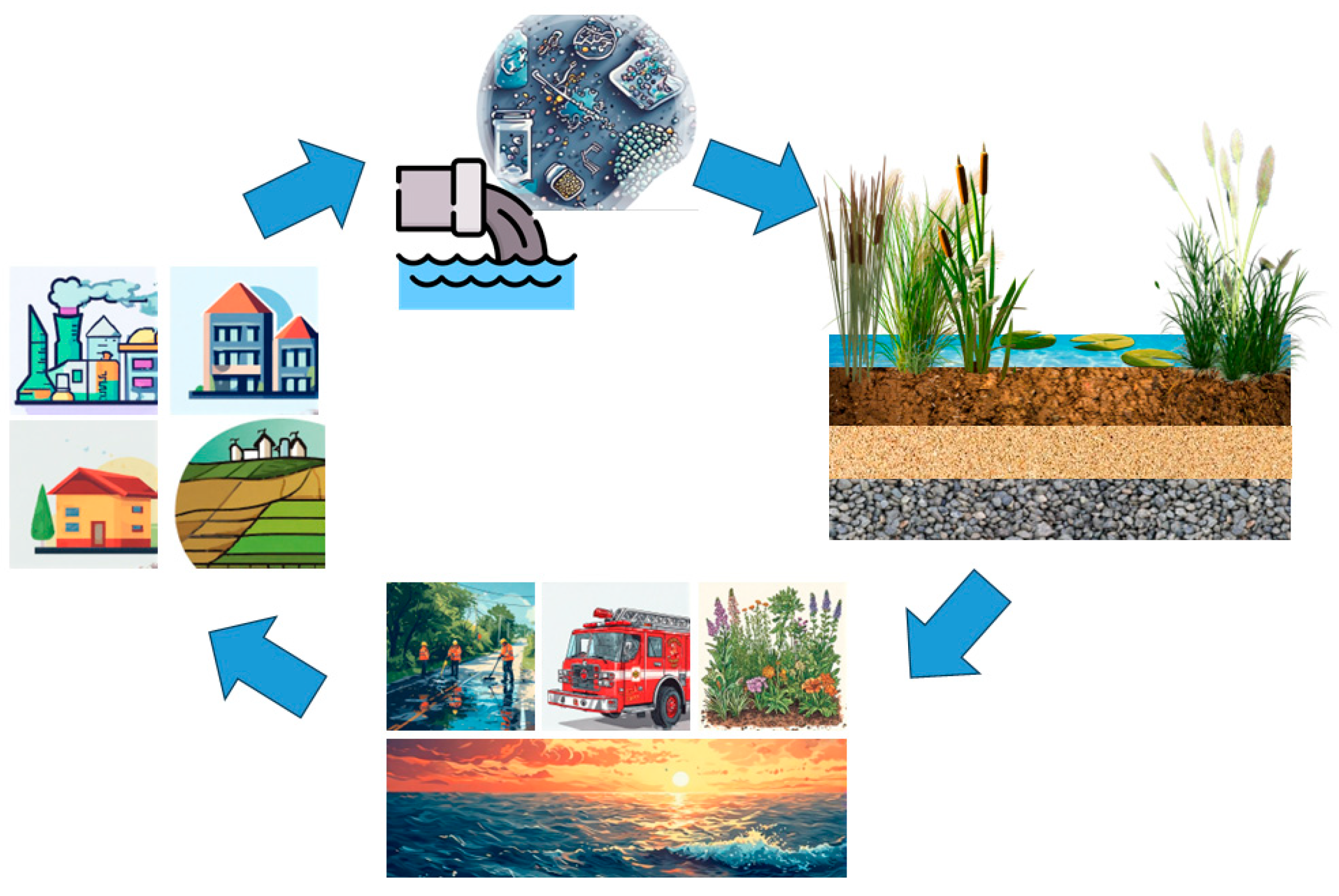

2. Sources and Impacts of Microplastic Pollution

2.1. Sources of Microplastic Pollution

2.2. Impacts of Microplastic Pollution

3. Nature-Based Solutions to Wastewater Treatment of Microplastics

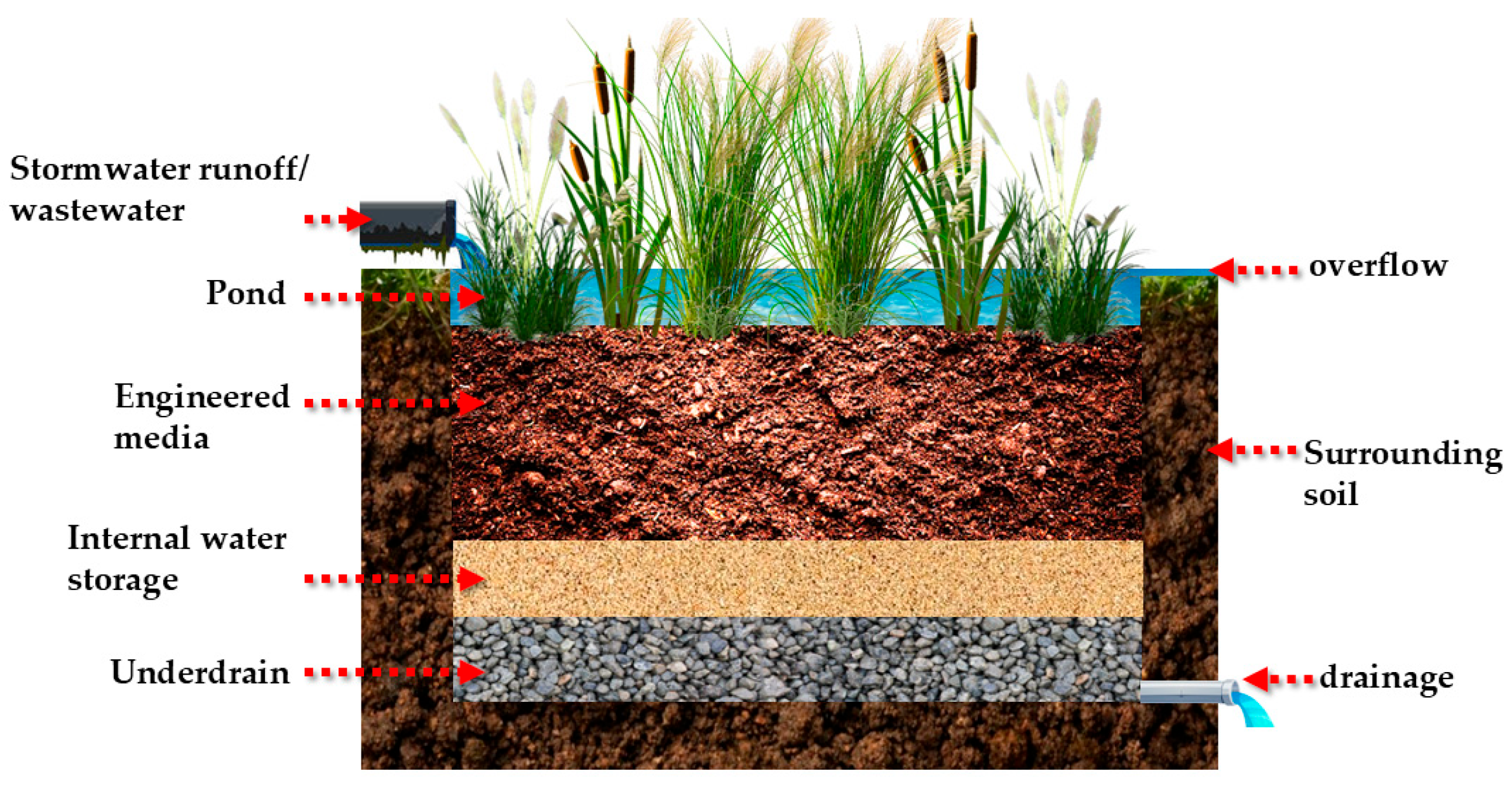

3.1. Constructed Wetlands

3.2. Green Infrastructures

3.3. Microphytes and Macrophytes

4. Prospects, Challenges, and Policy Recommendations

- Development of Supporting Policies and Framework. Comprehensive guidelines should be established for the design, planning, implementation, and maintenance of NbS technologies, including the definition of performance metrics for microplastic removal and environmental impact assessments. NbS should be incorporated into existing water quality regulations and standards to ensure they are recognized as viable alternative treatment options alongside conventional methods.

- Promoting Research and Innovation. R&D initiatives focusing on the effectiveness of NbS in microplastic removal must be funded. Pilot projects must be supported, particularly those that demonstrate the feasibility and effectiveness of NbS, providing valuable data for scaling successful models.

- Partnerships and Information and Education Campaign (IEC). Collaboration among government agencies, academic institutions, non-governmental organizations, civil society, and the private sector must be promoted to exchange knowledge, best practices, and resources related to NbS. Citizen science should be conducted to raise awareness about the benefits of NbS for wastewater treatment and the risks of microplastic pollution, engaging various stakeholders in the process.

- Sustainable Financing Mechanisms. Financial incentives, such as grants, subsidies, or tax breaks, must be provided for municipalities and industries that adopt NbS for wastewater treatment. Green financing options must be explored to support the development and maintenance of NbS, ensuring the accessibility of funding for NbS projects.

- Integration of NbS into Urban Planning. Development and urban planners must be encouraged to integrate NbS into land-use planning and infrastructure development.

- Accessibility and Capacity Building. NbS initiatives must ensure to be accessible, particularly for marginalized and underserved populations. Training and capacity-building programs must be provided for local stakeholders, including community members and wastewater treatment operators, to enhance their understanding and skills related to NbS.

5. Conclusions and Future Research Directions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMR | Antimicrobial resistance |

| CW | Constructed wetland |

| EPS | Extracellular polymeric substances |

| IEC | Information and education campaign |

| MSW | Municipal solid waste |

| NbS | Nature-based solution |

| PET | Polyethylene terephthalate |

References

- OECD. Global Plastics Outlook: Economic Drivers, Environmental Impacts and Policy Options; OECD Publishing: Paris, 2022.

- UNEP. Plastic Pollution. 2025.

- UNEP. Microplastics: The long legacy left behind by plastic pollution. 2023.

- Iyare, P.U.; Ouki, S.K.; Bond, T. Microplastics removal in wastewater treatment plants: A critical review. Environmental Science: Water Research & Technology 2020, 6, 2664-2675. [CrossRef]

- Tang, K.H.D.; Hadibarata, T. Microplastics removal through water treatment plants: Its feasibility, efficiency, future prospects and enhancement by proper waste management. Environmental Challenges 2021, 5. [CrossRef]

- Adetuyi, B.O.; Adetunji, C.O.; Olajide, P.A.; Ogunlana, O.O.; Mathew, J.T.; Inobeme, A.; Popoola, O.A.; Olaitan, F.Y.; Akinbo, O.; Oyewole, O.A.; et al. Removal of Microplastic from Wastewater Treatment Plants. In Microplastic Pollution; 2024; pp. 271-286.

- Sari Erkan, H.; Emik, H.H.; Onkal Engin, G. Microplastics in advanced biological wastewater treatment plant of Kocaeli, Turkey: Point source of microplastics reaching Marmara Sea. International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology 2023, 21, 1263-1284. [CrossRef]

- Asadi, A.; Khodadoost, F.; Daglioglu, N.; Eris, S. A systematic review on the occurrence and removal of microplastics during municipal wastewater treatment plants. Environmental Engineering Research 2024, 30, 240366-240360. [CrossRef]

- Kong, W.; Jalalah, M.; Alsareii, S.A.; Harraz, F.A.; Almadiy, A.A.; Zheng, Y.; Thakur, N.; Salama, E.-S. Microplastics (MPs) in wastewater treatment plants sludges: Substrates, digestive properties, microbial communities, mechanisms, and treatments. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2023, 11. [CrossRef]

- Mareddy, A.R. Technology in EIA. In Environmental Impact Assessment; 2017; pp. 421-490.

- Castelluccio, S.; Alvim, C.B.; Bes-Piá, M.A.; Mendoza-Roca, J.A.; Fiore, S. Assessment of Microplastics Distribution in a Biological Wastewater Treatment. Microplastics 2022, 1, 141-155. [CrossRef]

- Bayo, J.; LÓPez-Castellanos, J.; Olmos, S. Abatement of Microplastics from Municipal Effluents by Two Different Wastewater Treatment Technologies. In Proceedings of the Water Pollution XV, 2020; pp. 15-26.

- Vardar, S.; Onay, T.T.; Demirel, B.; Kideys, A.E. Evaluation of microplastics removal efficiency at a wastewater treatment plant discharging to the Sea of Marmara. Environmental Pollution 2021, 289. [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.S.; Hou, L.; Wang, Y.X.; Li, X.L.; Wang, W.B.; Liang, Q.B. [Effects of Wastewater Treatment Processes on the Removal Efficiency of Microplastics Based on Meta-analysis]. Huan Jing Ke Xue 2023, 44, 3309-3320. [CrossRef]

- Hernández Fernández, J.; Cano, H.; Guerra, Y.; Puello Polo, E.; Ríos-Rojas, J.F.; Vivas-Reyes, R.; Oviedo, J. Identification and Quantification of Microplastics in Effluents of Wastewater Treatment Plant by Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC). Sustainability 2022, 14, doi:10.3390/su14094920.

- Soni, V.; Poonia, K.; Sonu; Raizada, P.; Singh, P.; Hussain, C.M. Wastewater Treatment Plants and Microplastic Degradation. In Microplastics; 2024; pp. 279-294.

- Talvitie, J.; Mikola, A.; Koistinen, A.; Setälä, O. Solutions to microplastic pollution – Removal of microplastics from wastewater effluent with advanced wastewater treatment technologies. Water Research 2017, 123, 401-407. [CrossRef]

- Bodzek, M.; Pohl, A. Removal of microplastics in unit processes used in water and wastewater treatment: A review. Archives of Environmental Protection 2023, 48, 102-128. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.F.; Islam, N.; Tasannum, N.; Mehjabin, A.; Momtahin, A.; Chowdhury, A.A.; Almomani, F.; Mofijur, M. Microplastic removal and management strategies for wastewater treatment plants. Chemosphere 2024, 347. [CrossRef]

- Hidayaturrahman, H.; Lee, T.-G. A study on characteristics of microplastic in wastewater of South Korea: Identification, quantification, and fate of microplastics during treatment process. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2019, 146, 696-702. [CrossRef]

- Bayo, J.; López-Castellanos, J.; Olmos, S. Membrane bioreactor and rapid sand filtration for the removal of microplastics in an urban wastewater treatment plant. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2020, 156. [CrossRef]

- Goh, P.S.; Kang, H.S.; Ismail, A.F.; Khor, W.H.; Quen, L.K.; Higgins, D. Nanomaterials for microplastic remediation from aquatic environment: Why nano matters? Chemosphere 2022, 299. [CrossRef]

- Rebi, A.; Raza, T.; Wang, G.; Irfan, M.; Mushtaq, P.; Ali, M.; Narejo, K.R.; Hussain, A.; Khan, M.A.; Zhou, J. Environmental Sink of Microplastics Associated with Wastewater Treatment and Allied Processes. In Fate of Microplastics in Wastewater Treatment Plants; 2024; pp. 122-135.

- Agaton, C.B.; Guila, P.M.C. Success Factors and Challenges: Implications of Real Options Valuation of Constructed Wetlands as Nature-Based Solutions for Wastewater Treatment. Resources 2024, 13. [CrossRef]

- Adeoba, M.I.; Odjegba, E.E.; Pandelani, T. Nature-based solutions: Opportunities and challenges for water treatment. In Smart Nanomaterials for Environmental Applications; 2025; pp. 575-596.

- Jegatheesan, V.; Pachova, N.; Velasco, P.; Trang, N.T.D.; Thao, V.T.P.; Vo, T.-K.-Q.; Tran, C.-S.; Bui, X.-T.; Devanedara, M.C.; Estorba, D.S.; et al. Replicability and Pathways for the Scaling of Nature-Based Solutions for Water Treatment: Examples from the Philippines, Sri Lanka, and Vietnam. In Water Treatment in Urban Environments: A Guide for the Implementation and Scaling of Nature-based Solutions; Applied Environmental Science and Engineering for a Sustainable Future; 2024; pp. 203-224.

- Agaton, C.B. Real Options Analysis of Constructed Wetlands as Nature-Based Solutions to Wastewater Treatment Under Multiple Uncertainties: A Case Study in the Philippines. Sustainability 2024, 16 . [CrossRef]

- Falkenberg, L.J.; Cornet, J.E.; Joyce, P.W.S. Nature-based solutions to the management of legacy plastic pollution: Filter-feeders as bioremediation tools for coastal microplastics. Science of The Total Environment 2024, 956. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Shi, Y.; Zhu, W.; Luo, D.; Bai, X.; Krause, S. A low-impact nature-based solution for reducing aquatic microplastics from freshwater ecosystems. Water Research 2025, 268. [CrossRef]

- Cole, M.; Artioli, Y.; Coppock, R.; Galli, G.; Saad, R.; Torres, R.; Vance, T.; Yunnie, A.; Lindeque, P.K. Mussel power: Scoping a nature-based solution to microplastic debris. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2023, 453. [CrossRef]

- Büngener, L.; Galvão, A.; Postila, H.; Heiderscheidt, E. Microplastic retention in green walls for nature-based and decentralized greywater treatment. Environmental Pollution 2024, 363. [CrossRef]

- Mancini, M.; Solari, L.; Colomer, J.; Serra, T. Retention of microplastics by interspersed lagoons in both natural and constructed wetlands. Journal of Water Process Engineering 2023, 56. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Shen, C.; Zhang, F.; Wei, K.; Shan, S.; Zhao, Y.; Man, Y.B.; Wong, M.H.; Zhang, J. Microplastics removal mechanisms in constructed wetlands and their impacts on nutrient (nitrogen, phosphorus and carbon) removal: A critical review. Science of The Total Environment 2024, 918. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, T.; Gul, S.; Peng, L.; Mehmood, T.; Huang, Q.; Ahmad, A.; Ali, H.; Ali, W.; Souissi, S.; Zinck, P. Microplastic mitigation in urban stormwater using green infrastructure: A review. Environmental Chemistry Letters 2025, 23, 999-1024. [CrossRef]

- García-Haba, E.; Hernández-Crespo, C.; Martín, M.; Andrés-Doménech, I. The role of different sustainable urban drainage systems in removing microplastics from urban runoff: A review. Journal of Cleaner Production 2023, 411. [CrossRef]

- Fakhri, V.; Hamzehlouy, A.; Janmaleki Dehchani, A.; Moradi, E.; Tavakoli Dare, M.; Jafari, A.; Khonakdar, H.A. Green solutions for blue waters: Using biomaterials to purify water from microplastics and nanoplastics. Journal of Water Process Engineering 2024, 65. [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Wang, C.; Li, G. Defining Primary and Secondary Microplastics: A Connotation Analysis. ACS ES&T Water 2024, 4, 2330-2332. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Chan, F.K.S.; Stanton, T.; Johnson, M.F.; Kay, P.; He, J.; Wang, J.; Kong, C.; Wang, Z.; Liu, D.; et al. Synthesis of dominant plastic microfibre prevalence and pollution control feasibility in Chinese freshwater environments. Science of The Total Environment 2021, 783. [CrossRef]

- UNEP. Microplastics: Trouble in the Food Chain. UNEP Frontiers 2016 Report 2016, 33-43.

- Giechaskiel, B.; Grigoratos, T.; Mathissen, M.; Quik, J.; Tromp, P.; Gustafsson, M.; Franco, V.; Dilara, P. Contribution of Road Vehicle Tyre Wear to Microplastics and Ambient Air Pollution. Sustainability 2024, 16. [CrossRef]

- Bikiaris, N.; Nikolaidis, N.F.; Barmpalexis, P. Microplastics (MPs) in Cosmetics: A Review on Their Presence in Personal-Care, Cosmetic, and Cleaning Products (PCCPs) and Sustainable Alternatives from Biobased and Biodegradable Polymers. Cosmetics 2024, 11. [CrossRef]

- Gaylarde, C.C.; Neto, J.A.B.; da Fonseca, E.M. Paint fragments as polluting microplastics: A brief review. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2021, 162. [CrossRef]

- Thuan, P.M.; Nguyen, M.-K.; Nguyen, D.D. The potential release of microplastics from paint fragments: Characterizing sources, occurrence and ecological impacts. Environmental Geochemistry and Health 2025, 47. [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Xi, H.; Wan, C.; Fu, L.; Wang, Y.; Wu, C. Is the petrochemical industry an overlooked critical source of environmental microplastics? Journal of Hazardous Materials 2023, 451. [CrossRef]

- Avila-Escobedo, K.P.; Moctezuma-Parra, K.Y.; Alvarez-Zeferino, J.C.; Espinosa-Valdemar, R.M.; Sotelo-Navarro, P.X.; Vázquez-Morillas, A.; Cruz-Salas, A.A. Methodology for Analysis of Microplastics in Fine Fraction of Urban Solid Waste. Microplastics 2025, 4. [CrossRef]

- Ledieu, L.; Phuong, N.-N.; Flahaut, B.; Radigois, P.; Papin, J.; Le Guern, C.; Béchet, B.; Gasperi, J. May a Former Municipal Landfill Contaminate Groundwater in Microplastics? First Investigations from the “Prairie de Mauves Site” (Nantes, France). Microplastics 2023, 2, 93-106, doi:10.3390/microplastics2010007.

- Wan, Y.; Chen, X.; Liu, Q.; Hu, H.; Wu, C.; Xue, Q. Informal landfill contributes to the pollution of microplastics in the surrounding environment. Environmental Pollution 2022, 293. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, G.; Uchida, N.; Tuyen, L.H.; Tanaka, K.; Matsukami, H.; Kunisue, T.; Takahashi, S.; Viet, P.H.; Kuramochi, H.; Osako, M. Mechanical recycling of plastic waste as a point source of microplastic pollution. Environmental Pollution 2022, 303. [CrossRef]

- Belioka, M.-P.; Achilias, D.S. The Effect of Weathering Conditions in Combination with Natural Phenomena/Disasters on Microplastics’ Transport from Aquatic Environments to Agricultural Soils. Microplastics 2024, 3, 518-538,. [CrossRef]

- Jani, V.; Wu, S.; Venkiteshwaran, K. Advancements and Regulatory Situation in Microplastics Removal from Wastewater and Drinking Water: A Comprehensive Review. Microplastics 2024, 3, 98-123. [CrossRef]

- Mahagamage, M.G.Y.L.; Gamage, S.G.; Rathnayake, R.M.S.K.; Gamaralalage, P.J.D.; Hengesbugh, M.; Abeynayaka, T.; Welivitiya, C.; Udumalagala, L.; Rajitha, C.; Suranjith, S. Mitigating Microfiber Pollution in Laundry Wastewater: Insights from a Filtration System Case Study in Galle, Sri Lanka. Microplastics 2024, 3, 599-613. [CrossRef]

- Akyildiz, S.H.; Bellopede, R.; Sezgin, H.; Yalcin-Enis, I.; Yalcin, B.; Fiore, S. Detection and Analysis of Microfibers and Microplastics in Wastewater from a Textile Company. Microplastics 2022, 1, 572-586. [CrossRef]

- Visileanu, E.; Altmann, K.; Stepa, R.; Haiducu, M.; Miclea, P.T.; Vladu, A.; Dondea, F.; Grosu, M.C.; Scarlat, R. Comparative Analysis of Airborne Particle Concentrations in Textile Industry Environments Throughout the Workday. Microplastics 2025, 4. [CrossRef]

- Abbas, G.; Ahmed, U.; Ahmad, M.A. Impact of Microplastics on Human Health: Risks, Diseases, and Affected Body Systems. Microplastics 2025, 4,. [CrossRef]

- Gaylarde, C.C.; Baptista Neto, J.A.; da Fonseca, E.M. Indoor Airborne Microplastics: Human Health Importance and Effects of Air Filtration and Turbulence. Microplastics 2024, 3, 653-670. [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S.R.; Dey, A.; Mondal, S.; Gautam, M.K. Environmental microplastics and nanoplastics: Effects on cardiovascular system. Toxicologie Analytique et Clinique 2024, 36, 145-157. [CrossRef]

- Moiniafshari, K.; Zanut, A.; Tapparo, A.; Pastore, P.; Bogialli, S.; Abdolahpur Monikh, F. A perspective on the potential impact of microplastics and nanoplastics on the human central nervous system. Environmental Science: Nano 2025, 12, 1809-1820. [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Guo, X. Impact of soil structure and texture on occurrence of microplastics in agricultural soils of karst areas. Science of The Total Environment 2023, 902. [CrossRef]

- Wolff Leal, T.; Tochetto, G.; Lima, S.V.d.M.; de Oliveira, P.V.; Schossler, H.J.; de Oliveira, C.R.S.; da Silva Júnior, A.H. Nanoplastics and Microplastics in Agricultural Systems: Effects on Plants and Implications for Human Consumption. Microplastics 2025, 4. [CrossRef]

- Igalavithana, A.D.; Mahagamage, M.G.Y.L.; Gajanayake, P.; Abeynayaka, A.; Gamaralalage, P.J.D.; Ohgaki, M.; Takenaka, M.; Fukai, T.; Itsubo, N. Microplastics and Potentially Toxic Elements: Potential Human Exposure Pathways through Agricultural Lands and Policy Based Countermeasures. Microplastics 2022, 1, 102-120. [CrossRef]

- Lackner, M.; Branka, M. Microplastics in Farmed Animals—A Review. Microplastics 2024, 3, 559-588. [CrossRef]

- Pizzurro, F.; Recchi, S.; Nerone, E.; Salini, R.; Barile, N.B. Accumulation Evaluation of Potential Microplastic Particles in Mytilus galloprovincialis from the Goro Sacca (Adriatic Sea, Italy). Microplastics 2022, 1, 303-318. [CrossRef]

- Nabi, G.; Ahmad, S.; Ullah, S.; Zada, S.; Sarfraz, M.; Guo, X.; Ismail, M.; Wanghe, K. The adverse health effects of increasing microplastic pollution on aquatic mammals. Journal of King Saud University - Science 2022, 34. [CrossRef]

- Felline, S.; Piccardo, M.; De Benedetto, G.E.; Malitesta, C.; Terlizzi, A. Microplastics’ Occurrence in Edible Fish Species (Mullus barbatus and M. surmuletus) from an Italian Marine Protected Area. Microplastics 2022, 1, 291-302,. [CrossRef]

- Agaton, C.B.; Ancheta, M.J.J.; Paraiso, K.A.H.; Palomares, Z.F.; Sabo-o, A.J.M. Phenomenological Analysis of The Economic Impacts of a Coastal Disaster on The Tourism Sector of Pola, Oriental Mindoro. BIO Web of Conferences 2025, 176. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Sinha, J.K.; Ghosh, S.; Vashisth, K.; Han, S.; Bhaskar, R. Microplastics as an Emerging Threat to the Global Environment and Human Health. Sustainability 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Anuar, S.T.; Mohd Ali, A.A.; Cordova, M.R.; Charoenpong, C. Editorial: Baselines, impacts and mitigation strategies for plastic debris and microplastic pollution in South East Asia. Frontiers in Marine Science 2025, 12. [CrossRef]

- IUCN. Global Standard for Nature-based Solutions: A user-friendly framework for the verification, design and scaling up of NbS, First ed.; International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN): Gland, Switzerland, 2020.

- Cassin, J. History and development of nature-based solutions: Concepts and practice. In Nature-based Solutions and Water Security; 2021; pp. 19-34.

- Preti, F.; Capobianco, V.; Sangalli, P. Soil and Water Bioengineering (SWB) is and has always been a nature-based solution (NBS): A reasoned comparison of terms and definitions. Ecological Engineering 2022, 181. [CrossRef]

- Llosa, C.D.L.; Reyes Jr, E.M.; Agaton, C.B.; Cordero-Bailey, K.S.A. Thematic and Multicriteria Analyses of the Readiness, Factors, and Strategies for Successful Implementation of Nature-Based Solutions Initiatives in Victoria, Laguna. Journal of Human Ecology and Sustainability 2024, 2, 8. [CrossRef]

- Agaton, C.B.; Guila, P.M.C. Ecosystem Services Valuation of Constructed Wetland as a Nature-Based Solution to Wastewater Treatment. Earth 2023, 4, 78-92. [CrossRef]

- Agaton, C.B.; Guila, P.M.C.; Rodriguez, A.D.H. Economic Analysis of NbS for Wastewater Treatment Under Uncertainties. In Water Treatment in Urban Environments: A Guide for the Implementation and Scaling of Nature-based Solutions; Applied Environmental Science and Engineering for a Sustainable Future; 2024; pp. 55-81.

- Guila, P.M.C.; Agaton, C.B.; Rivera, R.R.B.; Abucay, E.R. Household Willingness to Pay for Constructed Wetlands as Nature-Based Solutions for Wastewater Treatment in Bayawan City, Philippines. Journal of Human Ecology and Sustainability 2024, 2, 5. [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Wang, R.; Yan, P.; Wu, S.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Cheng, C.; Hu, Z.; Zhuang, L.; Guo, Z.; et al. Constructed wetlands for pollution control. Nature Reviews Earth & Environment 2023, 4, 218-234. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, T.; Hu, H.; Ao, H.; Xiong, X.; Shi, H.; Wu, C. Transport and fate of microplastics in constructed wetlands: A microcosm study. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2021, 415. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Hernández-Crespo, C.; Santoni, M.; Van Hulle, S.; Rousseau, D.P.L. Horizontal subsurface flow constructed wetlands as tertiary treatment: Can they be an efficient barrier for microplastics pollution? Science of The Total Environment 2020, 721. [CrossRef]

- Rozman, U.; Klun, B.; Kalčíková, G. Distribution and removal of microplastics in a horizontal sub-surface flow laboratory constructed wetland and their effects on the treatment efficiency. Chemical Engineering Journal 2023, 461. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Hernández-Crespo, C.; Du, B.; Van Hulle, S.W.H.; Rousseau, D.P.L. Fate and removal of microplastics in unplanted lab-scale vertical flow constructed wetlands. Science of The Total Environment 2021, 778. [CrossRef]

- Sotiropoulou, M.; Stefanatou, A.; Schiza, S.; Petousi, I.; Stasinakis, A.S.; Fountoulakis, M.S. Removal of microfiber in vertical flow constructed wetlands treating greywater. Science of The Total Environment 2023, 858. [CrossRef]

- Kesarwani, S.; Panwar, D.; Mal, J.; Pradhan, N.; Rani, R. Constructed Wetland Coupled Microbial Fuel Cell: A Clean Technology for Sustainable Treatment of Wastewater and Bioelectricity Generation. Fermentation 2022, 9. [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, D.G.; Kachienga, L.O.; Rikhotso, M.C.; Abia, A.L.K.; Traoré, A.N.; Potgieter, N. Assessing the current situation of constructed wetland-microbial fuel cells as an alternative power generation and wastewater treatment in developing countries. Frontiers in Energy Research 2024, 12. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; He, L.; Feng, X. Effects of multi-microplastic mixtures on the performance of constructed wetland microbial fuel cells for wastewater treatment. Bioelectrochemistry 2025, 165. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Zhao, Y.; Pang, G.; Jia, X.; Song, Y.; Guo, A.; Wang, A.; Zhang, S.; Ji, M. Microplastic abundance, characteristics and removal in large-scale multi-stage constructed wetlands for effluent polishing in northern China. Chemical Engineering Journal 2022, 430. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; He, J.; Li, Y.; Sun, Z.; Du, H.; Wang, D.; Zhang, P.; Li, H. Abundance, characteristics, and removal of microplastics in the Cihu Lake-wetland microcosm system. Water Science & Technology 2023, 88, 278-287. [CrossRef]

- Vijayaraghavan, K.; Biswal, B.K.; Adam, M.G.; Soh, S.H.; Tsen-Tieng, D.L.; Davis, A.P.; Chew, S.H.; Tan, P.Y.; Babovic, V.; Balasubramanian, R. Bioretention systems for stormwater management: Recent advances and future prospects. Journal of Environmental Management 2021, 292. [CrossRef]

- Laramie, A.R.; Shuster, W.D.; Wager, Y.Z.; Darabi, M. Field assessment of engineered bioretention as microplastics sink through site characterization and hydrologic modeling. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2024, 480. [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Xiong, J.; Zhou, J.; Wang, Z.; Hu, T.; Xu, J. Microplastics removal from stormwater runoff by bioretention cells: A review. Journal of Environmental Sciences 2025, 154, 73-90. [CrossRef]

- Addo-Bankas, O.; Wei, T.; Tang, C.; Zhao, Y. Optimizing greywater treatment in green walls: A comparative analysis of recycled substrate materials. Journal of Water Process Engineering 2024, 67. [CrossRef]

- Kong, J.; Jeong, S.; Lee, J.; Jeong, S. Permeable pavement blocks as a sustainable solution for managing microplastic pollution in urban stormwater. Science of The Total Environment 2025, 966. [CrossRef]

- García-Haba, E.; Benito-Kaesbach, A.; Hernández-Crespo, C.; Sanz-Lazaro, C.; Martín, M.; Andrés-Doménech, I. Removal and fate of microplastics in permeable pavements: An experimental layer-by-layer analysis. Science of The Total Environment 2024, 929. [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Vianello, A.; Vollertsen, J. Retention of microplastics in sediments of urban and highway stormwater retention ponds. Environmental Pollution 2019, 255. [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, L.A.; Liu, F.; Klemmensen, N.D.R.; Lykkemark, J.; Vollertsen, J. Retention of microplastics and tyre wear particles in stormwater ponds. Water Research 2024, 248. [CrossRef]

- Ashiq, M.M.; Jazaei, F.; Bell, K.; Ali, A.S.A.; Bakhshaee, A.; Babakhani, P. Abundance, spatial distribution, and physical characteristics of microplastics in stormwater detention ponds. Frontiers of Environmental Science & Engineering 2023, 17. [CrossRef]

- Afonso, V.; Borges, R.; Rodrigues, B.; Barros, R.; João Bebianno, M.; Raposo, S. Are native microalgae consortia able to remove microplastics from wastewater effluents? Environmental Pollution 2024, 349. [CrossRef]

- Gopalakrishnan, K.; Kashian, D.R. Extracellular polymeric substances in green alga facilitate microplastic deposition. Chemosphere 2022, 286. [CrossRef]

- Hadiyanto, H.; Khoironi, A.; Dianratri, I.; Joelyna, F.A.; Christwardana, M.; Sabhira, A.I.; Baihaqi, R.A. Microplastic removal in aquatic systems using extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) of microalgae. Sustainable Environment 2025, 11. [CrossRef]

- Das, P.; Bal, M. Modeling and optimization study for microplastic removal from aquatic medium using Chroococcidiopsis species. Chemical Engineering Science 2025, 304. [CrossRef]

- Mateos-Cárdenas, A.; van Pelt, F.N.A.M.; O’Halloran, J.; Jansen, M.A.K. Adsorption, uptake and toxicity of micro- and nanoplastics: Effects on terrestrial plants and aquatic macrophytes. Environmental Pollution 2021, 284. [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Goh, Y.L.; Mowe, M.A.D.; Todd, P.A.; Yeo, D.C.J. The effects of microplastics size and type on entrapment by freshwater macrophytes under vertical and lateral deposition. Journal of Limnology 2025, 84. [CrossRef]

- del Refugio Cabañas-Mendoza, M.; Olguín, E.J.; Sánchez-Galván, G.; Melo, F.J.; Barrientos, M.S.A. Contribution of the root system of Cyperus papyrus and Pontederia sagittata to microplastic removal in floating treatment Wetlands in two urban ponds. Ecological Engineering 2024, 206. [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Zhu, T.; Li, X.; Wang, F.; Xu, G. Phytoremediation of microplastics by water hyacinth. Environmental Science and Ecotechnology 2025, 24. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Park, K.; Bak, J.; Choi, S. Iris pseudacorus and Lythrum anceps as Plants Supporting the Process of Removing Microplastics from Aquatic Environments—Preliminary Research. Horticulturae 2024, 10,. [CrossRef]

- Sayanthan, S.; Hasan, H.A.; Abdullah, S.R.S. Floating Aquatic Macrophytes in Wastewater Treatment: Toward a Circular Economy. Water 2024, 16. [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Gao, S.-H.; Ge, C.; Gao, Q.; Huang, S.; Kang, Y.; Luo, G.; Zhang, Z.; Fan, L.; Zhu, Y.; et al. Removing microplastics from aquatic environments: A critical review. Environmental Science and Ecotechnology 2023, 13. [CrossRef]

- Carnevale Miino, M.; Galafassi, S.; Zullo, R.; Torretta, V.; Rada, E.C. Microplastics removal in wastewater treatment plants: A review of the different approaches to limit their release in the environment. Science of The Total Environment 2024, 930. [CrossRef]

- Sadia, M.; Mahmood, A.; Ibrahim, M.; Irshad, M.K.; Quddusi, A.H.A.; Bokhari, A.; Mubashir, M.; Chuah, L.F.; Show, P.L. Microplastics pollution from wastewater treatment plants: A critical review on challenges, detection, sustainable removal techniques and circular economy. Environmental Technology & Innovation 2022, 28. [CrossRef]

- Devanadera, M.C.; Estorba, D.S.; Guerrero, K.M.; Lecciones, A. Social Acceptability Assessment for Nature-Based Solution for Wastewater Treatment. In Water Treatment in Urban Environments: A Guide for the Implementation and Scaling of Nature-based Solutions; Applied Environmental Science and Engineering for a Sustainable Future; 2024; pp. 83-94.

| Treatment Technology | Microbeads | Fibers | Other Microplastics |

Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Treatment | > 98.4% | > 71.8% | > 62.7% | [5,6,7,8] |

| Secondary Treatment | > 100% | > 57.8% | > 96.9% | [5,6,14,15] |

| Tertiary Treatment | > 99.9% | > 57.7% | > 95% | [12,17,20,21] |

| Nature-based Solution | Microplastics Removal Rate |

|---|---|

| Constructed wetlands | < 100% |

| Green infrastructures | 50-99% |

| Macrophytes | > 94% |

| Microphytes | > 82% |

| Microphytes | Microplastics Removal/ Flocculation |

|---|---|

| Spirulina sp. | Most effective |

| Tetraselmis chuii | Effective |

| Chlorella vulgaris | > 94% |

| Dunaliella salina | Less effective |

| Chroococcidiopsis cubana | > 91% |

| Macrophytes | Microplastic size | Removal Efficiency |

Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrilla verticillata | 800-1000 µm | High | Leaf surface area |

| Mayaca fluviatilis | 600-800 µm | Moderate | Surface cellulose |

| Myriophyllum aquaticum | >100 µm | 93.38% | Optimized conditions |

|

Cyperus papyrus, Pontederia sagittata |

Various sizes | 82.4%-81.1% | Root retention |

| Eichhornia crassipes | 0.5-2 µm | 55.3%-69.1% | Root adsorption |

|

Iris pseudacorus Lythrum anceps |

Various sizes Various sizes |

81.5% 77.3% |

Root adsorption Root adsorption |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).