Submitted:

21 July 2025

Posted:

22 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

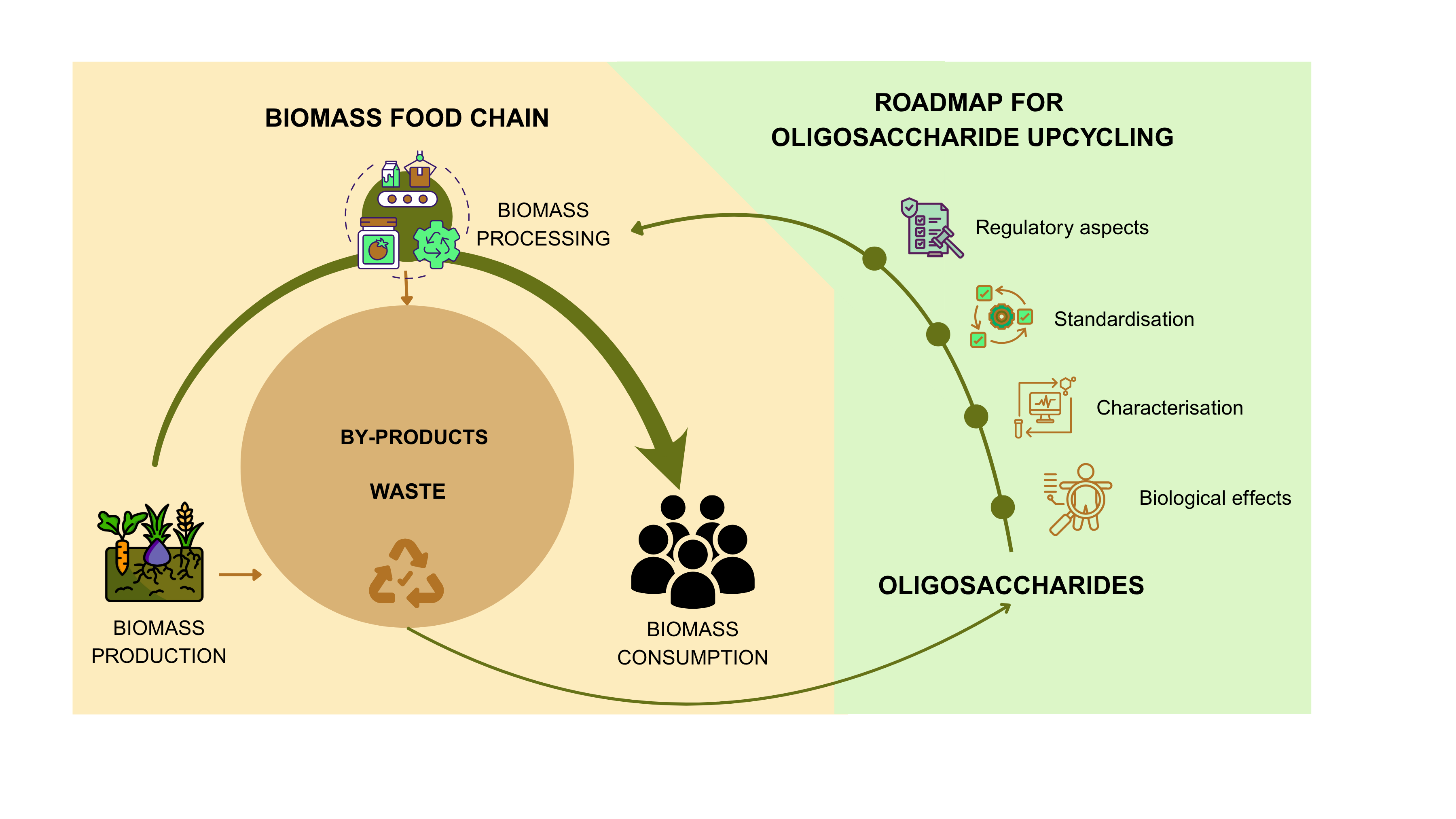

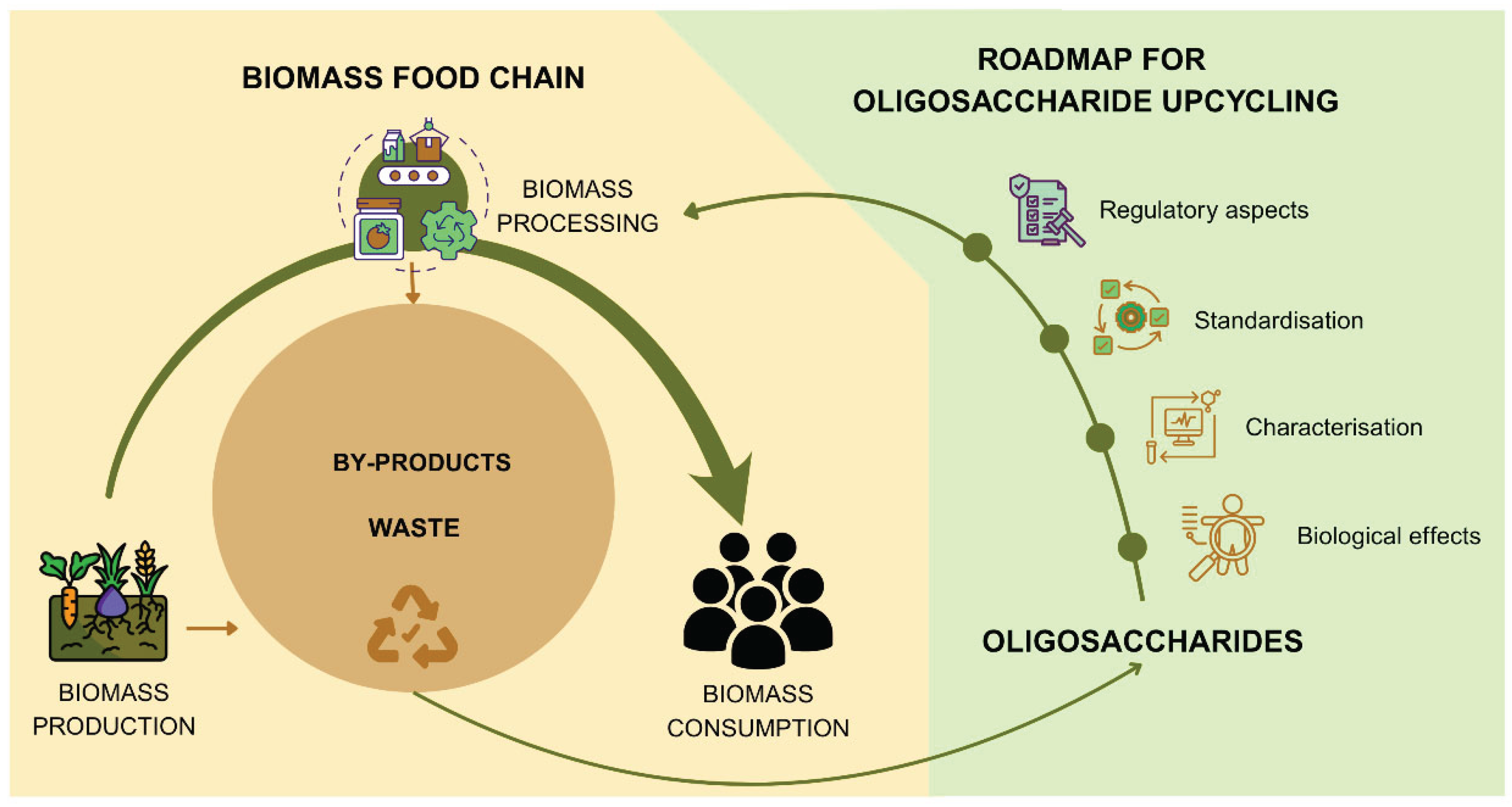

1.1. Relevance of Oligosaccharides in Biomass Valorisation

1.2. Oligosaccharides in Circular Bioeconomy: Expanding Their Functional Perspectives

2. Oligosaccharides from Biomass: Sources and Upcycling Pathways

2.1. Structural Diversity of Oligosaccharides

2.2. Extraction Strategies for Obtaining Oligosaccharides

2.3. Green Chemistry and Enzymatic Synthesis Approaches

3. Oligosaccharides as Bioactive Food Ingredients: Receptor Interactions and Structure-Dependent Host Modulation

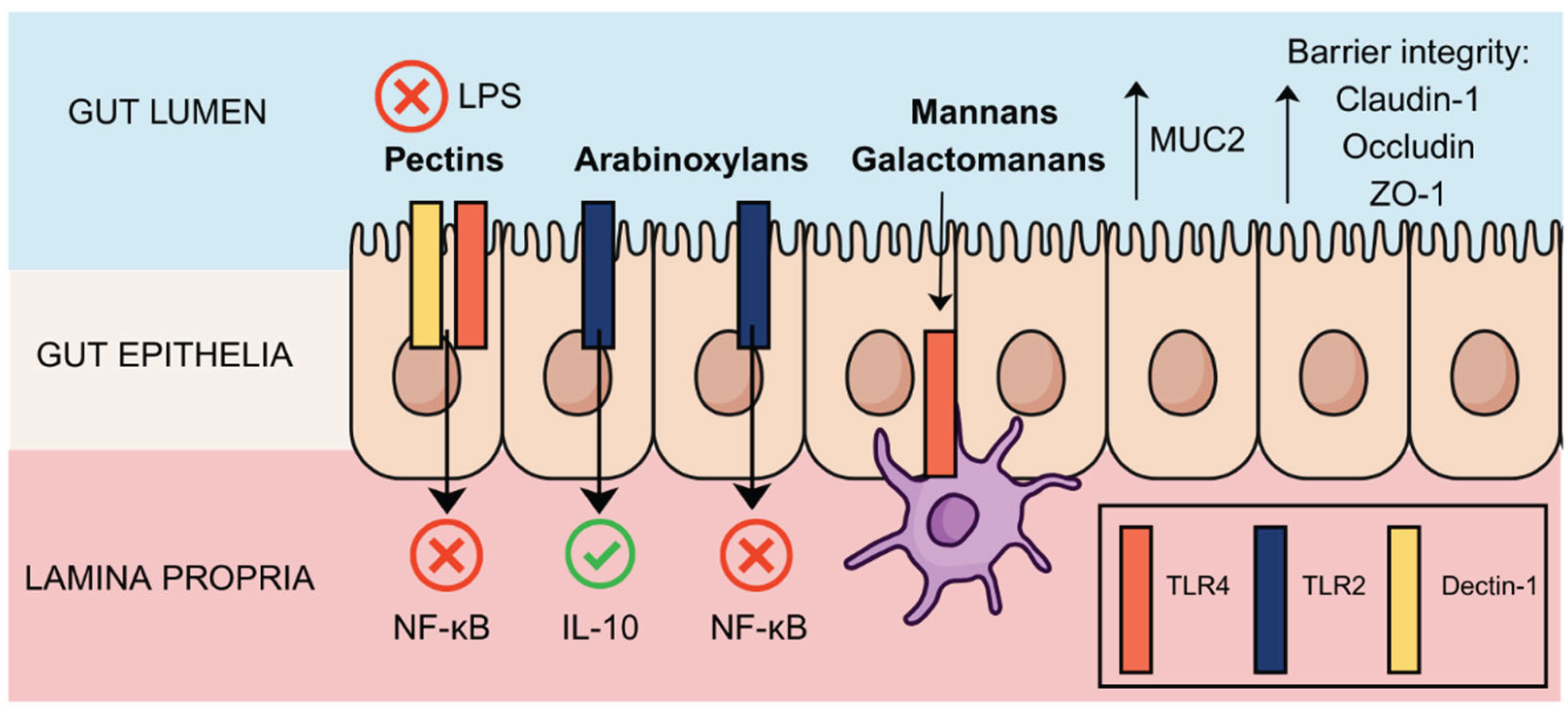

3.1. Host Receptor Targets in the Intestinal and Immune System

3.2. Structure–Activity Relationships: Fine Structural Features Dictate Bioactivity

3.3. Translational Applications and the Path Toward Precision Nutrition

5. Regulatory Pathways for Functional Oligosaccharides

6. Final Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AXOS | Arabinoxylooligosaccharides |

| CLR | C-type lectin receptor |

| DC | Dendritic cell |

| DES | Deep eutectic solvent |

| DP | Degree of polymerization |

| EFSA | European Food Safety Authority |

| EMIM Ac | 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| FFAR2 | Free fatty acid receptor 2 (GPR43) |

| FOS | Fructooligosaccharides |

| GOS | Galactooligosaccharides |

| GPCR | G protein-coupled receptor |

| GRAS | Generally recognised as safe |

| HWE | Hot water extraction |

| IBD | Inflammatory bowel disease |

| IL-10 | Interleukin-10 |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| MAE | Microwave-assisted extraction |

| MOS | Mannooligosaccharides |

| MUC | Mucin |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| POS | Pectic oligosaccharides |

| PPARγ | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma |

| PRR | Pattern recognition receptor |

| SCFA | Short-chain fatty acids |

| SIGN | Specific intercellular adhesion molecule-3-grabbing non-integrin |

| SWE | Subcritical water extraction |

| TFF | Tangential flow filtration |

| TLR | Degree of polymerization |

| UAE | Ultrasound-assisted extraction |

| ZO-1 | Zonulla occludens-1 |

References

- Orrego, D.; Olivares-Tenorio, M.L.; Hoyos, L. V.; Alvarez-Vasco, C.; Klotz-Ceberio, B.; Caicedo, N. Towards a Sustainable Circular Bioprocess: Pectic Oligosaccharides (POS) Enzymatic Production Using Passion Fruit Peels. Lwt 2024, 207, 116681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chockchaisawasdee, S.; Stathopoulos, C.E. Functional Oligosaccharides Derived from Fruit-and-Vegetable By-Products and Wastes. Horticulturae 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arzami, A.N.; Ho, T.M.; Mikkonen, K.S. Valorization of Cereal By-Product Hemicelluloses: Fractionation and Purity Considerations. Food Res. Int. 2022, 151, 110818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madhukumar, M.S.; Muralikrishna, G. Fermentation of Xylo-Oligosaccharides Obtained from Wheat Bran and Bengal Gram Husk by Lactic Acid Bacteria and Bifidobacteria. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2012, 49, 745–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karnaouri, A.; Matsakas, L.; Krikigianni, E.; Rova, U.; Christakopoulos, P. Valorization of Waste Forest Biomass toward the Production of Cello-Oligosaccharides with Potential Prebiotic Activity by Utilizing Customized Enzyme Cocktails. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2019, 12, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Chen, Y.; Chen, R.; Wen, Y.; Huang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, C. Research Status of the Effects of Natural Oligosaccharides on Glucose Metabolism. eFood 2022, 3, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.H.; Seong, H.; Chang, D.; Gupta, V.K.; Kim, J.; Cheon, S.; Kim, G.; Sung, J.; Han, N.S. Evaluating the Prebiotic Effect of Oligosaccharides on Gut Microbiome Wellness Using in Vitro Fecal Fermentation. npj Sci. Food 2023, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortega-González, M.; Ocón, B.; Romero-Calvo, I.; Anzola, A.; Guadix, E.; Zarzuelo, A.; Suárez, M.D.; Sánchez de Medina, F.; Martínez-Augustin, O. Nondigestible Oligosaccharides Exert Nonprebiotic Effects on Intestinal Epithelial Cells Enhancing the Immune Response via Activation of TLR4-NFκB. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2014, 58, 384–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.C.; Chen, H.H.; Chen, Y.K.; Chang, H.C.; Lin, P.Y.; Pan, I.H.; Chen, D.Y.; Chen, C.M.; Lin, S.Y. Rice Bran Feruloylated Oligosaccharides Activate Dendritic Cells via Toll-like Receptor 2 and 4 Signaling. Molecules 2014, 19, 5325–5347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, P.; Brown, C.; Arneth, A.; Finnigan, J.; Moran, D.; Rounsevell, M.D.A. Losses, Inefficiencies and Waste in the Global Food System. Agric. Syst. 2017, 153, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarker, A.; Ahmmed, R.; Ahsan, S.M.; Rana, J.; Ghosh, M.K.; Nandi, R. A Comprehensive Review of Food Waste Valorization for the Sustainable Management of Global Food Waste. Sustain. Food Technol. 2023, 2, 48–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujtaba, M.; Fernandes Fraceto, L.; Fazeli, M.; Mukherjee, S.; Savassa, S.M.; Araujo de Medeiros, G.; do Espírito Santo Pereira, A.; Mancini, S.D.; Lipponen, J.; Vilaplana, F. Lignocellulosic Biomass from Agricultural Waste to the Circular Economy: A Review with Focus on Biofuels, Biocomposites and Bioplastics. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 402, 136815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibas-Dorna, M.; Żukiewicz-Sobczak, W. Sustainable Nutrition and Human Health as Part of Sustainable Development. Nutrients 2024, 16, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chelliah, R.; Kim, N.H.; Park, S.J.; Park, Y.; Yeon, S.J.; Barathikannan, K.; Vijayalakshmi, S.; Oh, D.H. Revolutionizing Renewable Resources: Cutting-Edge Trends and Future Prospects in the Valorization of Oligosaccharides. Fermentation 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Wang, H.; Yang, Z.; Zhao, K.; Li, S.; He, N. The Role of Functional Oligosaccharides as Prebiotics in Ulcerative Colitis. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 6875–6893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, W.; Lu, J.; Li, B.; Lin, W.; Zhang, Z.; Wei, X.; Sun, C.; Chi, M.; Bi, W.; Yang, B.; et al. Effect of Functional Oligosaccharides and Ordinary Dietary Fiber on Intestinal Microbiota Diversity. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maldonado-Gomez, M.X.; Ng, K.M.; Drexler, R.A.; Conner, A.M.S.; Vierra, C.G.; Krishnakumar, N.; Gerber, H.M.; Taylor, Z.R.; Treon, J.L.; Ellis, M.; et al. A Diverse Set of Solubilized Natural Fibers Drives Structure-Dependent Metabolism and Modulation of the Human Gut Microbiota. MBio 2025, 16, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Jian, C.; Salonen, A.; Dong, M.; Yang, Z. Designing Healthier Bread through the Lens of the Gut Microbiota. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 134, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerreiro, C. de A.; Andrade, L.A.D.; Fernández-Lainez, C.; Fraga, L.N.; López-Velázquez, G.; Marques, T.M.; Prado, S.B.R.; Brummer, R.J.; Nascimento, J.R.O.; Castro-Alves, V. Bioactive Arabinoxylan Oligomers via Colonic Fermentation and Enzymatic Catalysis: Evidence of Interaction with Toll-like Receptors from in Vitro, in Silico and Functional Analysis. Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, A.; Li, Z.; Zhao, W.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yao, M.; Yao, W.; Zhang, X.; Meng, X.; Li, Z.; et al. Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Mirror Isomers of β-(1 → 3)-Glucans as Immune Modulators. Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 357, 123477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro-Alves, V.C.; Nascimento, J.R.O. do Size Matters: TLR4-Mediated Effects of α-(1,5)-Linear Arabino-Oligosaccharides in Macrophage-like Cells Depend on Their Degree of Polymerization. Food Res. Int. 2021, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, W.; Bi, D.; Zheng, R.; Cai, N.; Xu, H.; Zhou, R.; Lu, J.; Wan, M.; Xu, X. Identification and Activation of TLR4-Mediated Signalling Pathways by Alginate-Derived Guluronate Oligosaccharide in RAW264.7 Macrophages. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, E.C.; Odle, J.; Blikslager, A.T.; Ziegler, A.L. Probiotics, Prebiotics and Epithelial Tight Junctions: A Promising Approach to Modulate Intestinal Barrier Function. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semin, I.; Ninnemann, J.; Bondareva, M.; Gimaev, I.; Kruglov, A.A. Interplay Between Microbiota, Toll-Like Receptors and Cytokines for the Maintenance of Epithelial Barrier Integrity. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, X.; Zhu, S.; Yang, H.; Wang, X.; Li, J.; Liu, S.; Xing, R.; Li, P.; Li, K. Impact of O-Acetylation on Chitin Oligosaccharides Modulating Inflammatory Responses in LPS-Induced RAW264.7 Cells and Mice. Carbohydr. Res. 2024, 542, 109177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathura, S.R.; Landázuri, A.C.; Mathura, F.; Andrade Sosa, A.G.; Orejuela-Escobar, L.M. Hemicelluloses from Bioresidues and Their Applications in the Food Industry – towards an Advanced Bioeconomy and a Sustainable Global Value Chain of Chemicals and Materials. Sustain. Food Technol. 2024, 2, 1183–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abik, F.; Palasingh, C.; Bhattarai, M.; Leivers, S.; Ström, A.; Westereng, B.; Mikkonen, K.S.; Nypelö, T. Potential of Wood Hemicelluloses and Their Derivates as Food Ingredients. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 2667–2683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Najjoum, N.; Grimi, N.; Benali, M.; Chadni, M.; Castignolles, P. Extraction and Chemical Features of Wood Hemicelluloses: A Review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 311, 143681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gautam, D.; Rana, V.; Sharma, S.; Kumar Walia, Y.; Kumar, K.; Umar, A.; Ibrahim, A.A.; Baskoutas, S. Hemicelluloses: A Review on Extraction and Modification for Various Applications. ChemistrySelect 2025, 10, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahtinen, M.H.; Kynkäänniemi, E.; Jian, C.; Salonen, A.; Pajari, A.M.; Mikkonen, K.S. Metabolic Fate of Lignin in Birch Glucuronoxylan Extracts as Dietary Fiber Studied in a Rat Model. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2023, 67, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Abad, A.; Giummarella, N.; Lawoko, M.; Vilaplana, F. Differences in Extractability under Subcritical Water Reveal Interconnected Hemicellulose and Lignin Recalcitrance in Birch Hardwoods. Green Chem. 2018, 20, 2534–2546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, P.C.; Evtuguin, D. V.; Neto, C.P. Structure of Hardwood Glucuronoxylans: Modifications and Impact on Pulp Retention during Wood Kraft Pulping. Carbohydr. Polym. 2005, 60, 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais De Carvalho, D.; Marchand, C.; Berglund, J.; Lindström, M.E.; Vilaplana, F.; Sevastyanova, O. Impact of Birch Xylan Composition and Structure on Film Formation and Properties. Holzforschung 2020, 74, 184–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, A.; Butler, S.; Al-Rudainy, B.; Wallberg, O.; Stålbrand, H. Enzymatic Conversion of Different Qualities of Refined Softwood Hemicellulose Recovered from Spent Sulfite Liquor. Molecules 2022, 27, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Wang, L.; Chao, Y.; Nawawi, D.S.; Akiyama, T.; Yokoyama, T.; Matsumoto, Y. Relationships between Hemicellulose Composition and Lignin Structure in Woods. J. Wood Chem. Technol. 2016, 36, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saez-Aguayo, S.; Sanhueza, D.; Fuenzalida, P.; Covarrubias, M.P.; Handford, M.; Herrera, R.; Moya-León, M.A. Back to the Wastes: The Potential of Agri-Food Residues for Extracting Valuable Plant Cell Wall Polysaccharides. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vojvodić, A.; Komes, D.; Vovk, I.; Belščak-Cvitanović, A.; Bušić, A. Compositional Evaluation of Selected Agro-Industrial Wastes as Valuable Sources for the Recovery of Complex Carbohydrates. Food Res. Int. 2016, 89, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yapo, B.M.; Lerouge, P.; Thibault, J.F.; Ralet, M.C. Pectins from Citrus Peel Cell Walls Contain Homogalacturonans Homogenous with Respect to Molar Mass, Rhamnogalacturonan I and Rhamnogalacturonan II. Carbohydr. Polym. 2007, 69, 426–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, N.; Kumar, M.; Radha; Rais, N. ; Puri, S.; Sharma, K.; Natta, S.; Dhumal, S.; Damale, R.D.; Kumar, S.; et al. Exploring Apple Pectic Polysaccharides: Extraction, Characterization, and Biological Activities - A Comprehensive Review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 255, 128011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, R.; Fan, R.; Hu, J.; Zhang, X.; Han, L.; Wang, M.; He, C. Valorization of Apple Pomace: Structural and Rheological Characterization of Low-Methoxyl Pectins Extracted with Green Agents of Citric Acid/Sodium Citrate. Food Chem. X 2024, 24, 102010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glaser, S.J.; Abdelaziz, O.Y.; Demoitié, C.; Galbe, M.; Pyo, S.H.; Jensen, J.P.; Hatti-Kaul, R. Fractionation of Sugar Beet Pulp Polysaccharides into Component Sugars and Pre-Feasibility Analysis for Further Valorisation. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2024, 14, 3575–3588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczmarska, A.; Pieczywek, P.M.; Cybulska, J.; Zdunek, A. A Mini-Review on the Plant Sources and Methods for Extraction of Rhamnogalacturonan I. Food Chem. 2023, 403, 134378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, Y.; Lei, R.; Ryan, J.; Arrutia Rodriguez, F.; Rastall, B.; Chatzifragkou, A.; Winkworth-Smith, C.; Harding, S.E.; Ibbett, R.; Binner, E. Understanding the Influence of Processing Conditions on the Extraction of Rhamnogalacturonan-I “Hairy” Pectin from Sugar Beet Pulp. Food Chem. X 2019, 2, 100026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez, M.; Gullón, B.; Yáñez, R.; Alonso, J.L.; Parajó, J.C. Direct Enzymatic Production of Oligosaccharide Mixtures from Sugar Beet Pulp: Experimental Evaluation and Mathematical Modeling. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 5510–5517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeddou, K. Ben; Bouaziz, F.; Helbert, C.B.; Nouri-Ellouz, O.; Maktouf, S.; Ellouz-Chaabouni, S.; Ellouz-Ghorbel, R. Structural, Functional, and Biological Properties of Potato Peel Oligosaccharides. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 112, 1146–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cámara Hurtado, M.; Greve, L.C.; Labavitch, J.M. Changes in Cell Wall Pectins Accompanying Tomato (Lycopersicon Esculentum Mill.) Paste Manufacture. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mudannayake, D.C.; Jayasena, D.D.; Wimalasiri, K.M.S.; Ranadheera, C.S.; Ajlouni, S. Inulin Fructans – Food Applications and Alternative Plant Sources: A Review. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 57, 5764–5780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. yue; Zhuang, D.; Wang, H. yang; Liu, C. yao; Lv, G. ping; Meng, L. juan Preparation, Characterization, and Bioactivity Evaluation of Oligosaccharides from Atractylodes Lancea (Thunb.) DC. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ueno, K.; Oku, S.; Shimura, H.; Yoshihira, T.; Onodera, S. Variation of Fructan and Its Metabolizing Enzymes in Onions with Different Storage Characteristics. J. Appl. Glycosci. 2025, 72, n. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zannini, E.; Bravo Núñez, Á.; Sahin, A.W.; Arendt, E.K. Arabinoxylans as Functional Food Ingredients: A Review. Foods (Basel, Switzerland) 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roubroeks, J.P.; Andersson, R.; Åman, P. Structural Features of (1 → 3),(1 → 4)-β-D-Glucan and Arabinoxylan Fractions Isolated from Rye Bran. Carbohydr. Polym. 2000, 42, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus Schmidt, B.W. and J.H. Comparison of Alkaline/Oxidative and Hydrothermal. Foods 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kulathunga, J.; Islam, S. Wheat Arabinoxylans: Insight into Structure-Function Relationships. Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 348, 122933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schendel, R.R.; Meyer, M.R.; Bunzel, M. Quantitative Profiling of Feruloylated Arabinoxylan Side-Chains from Graminaceous Cell Walls. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malunga, L.N.; Beta, T. Isolation and Identification of Feruloylated Arabinoxylan Mono- and Oligosaccharides from Undigested and Digested Maize and Wheat. Heliyon 2016, 2, e00106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, B.; Meenu, M.; Liu, H.; Xu, B. A Concise Review on the Molecular Structure and Function Relationship of β-Glucan. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikkelsen, M.S.; Jespersen, B.M.; Larsen, F.H.; Blennow, A.; Engelsen, S.B. Molecular Structure of Large-Scale Extracted β-Glucan from Barley and Oat: Identification of a Significantly Changed Block Structure in a High β-Glucan Barley Mutant. Food Chem. 2013, 136, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reichembach, L.H.; Kaminski, G.K.; Maurer, J.B.B.; de Oliveira Petkowicz, C.L. Fractionation and Characterization of Cell Wall Polysaccharides from Coffee (Coffea Arabica L.) Pulp. Carbohydr. Polym. 2024, 327, 121693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanai, N.; Yamada, K.; Sumida, C.; Tanzawa, M.; Ito, Y.; Saito, T.; Kimura, R.; Saito-Yamazaki, M.; Oyama, T.; Isogai, A.; et al. Mannan-Rich Holocellulose Nanofibers Mechanically Isolated from Spent Coffee Grounds: Structure and Properties. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2024, 8, 100539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalidas, N.R.; Saminathan, M.; Ismail, I.S.; Abas, F.; Maity, P.; Islam, S.S.; Manshoor, N.; Shaari, K. Structural Characterization and Evaluation of Prebiotic Activity of Oil Palm Kernel Cake Mannanoligosaccharides. Food Chem. 2017, 234, 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Cui, H.; Xie, F.; Song, Z.; Ai, L. Tamarind Seeds Polysaccharide: Structure, Properties, Health Benefits, Modification and Food Applications. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 155, 110222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Sakurai, N.; Nevins, D.J. Characterization of Kiwifruit Xyloglucan. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2009, 51, 933–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, P.; Hu, Y.; Tian, R.; Bian, J.; Peng, F. Hydrothermal Pretreatment for the Production of Oligosaccharides: A Review. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 343, 126075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trabert, A.; Schmid, V.; Keller, J.; Emin, M.A.; Bunzel, M. Chemical Composition and Technofunctional Properties of Carrot (Daucus Carota L.) Pomace and Potato (Solanum Tuberosum L.) Pulp as Affected by Thermomechanical Treatment. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2022, 248, 2451–2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prado, S.B.R. do; Ferreira, G.F.; Harazono, Y.; Shiga, T.M.; Raz, A.; Carpita, N.C.; Fabi, J.P. Ripening-Induced Chemical Modifications of Papaya Pectin Inhibit Cancer Cell Proliferation. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 16564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedrosa, L. de F.; Kouzounis, D.; Schols, H.; de Vos, P.; Fabi, J.P. Assessing High-Temperature and Pressure Extraction of Bioactive Water-Soluble Polysaccharides from Passion Fruit Mesocarp. Carbohydr. Polym. 2024, 335, 122010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narisetty, V.; Parhi, P.; Mohan, B.; Hakkim Hazeena, S.; Naresh Kumar, A.; Gullón, B.; Srivastava, A.; Nair, L.M.; Paul Alphy, M.; Sindhu, R.; et al. Valorization of Renewable Resources to Functional Oligosaccharides: Recent Trends and Future Prospective. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ávila, P.F.; Goldbeck, R. Fractionating Process of Lignocellulosic Biomass for the Enzymatic Production of Short Chain Cello-Oligosaccharides. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klinchongkon, K.; Khuwijitjaru, P.; Wiboonsirikul, J.; Adachi, S. Extraction of Oligosaccharides from Passion Fruit Peel by Subcritical Water Treatment. J. Food Process Eng. 2017, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Cao, R.; Xu, Y. Acidic Hydrolyzed Xylo-Oligosaccharides Bioactivity on the Antioxidant and Immune Activities of Macrophage. Food Res. Int. 2023, 163, 112152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fogarin, H.M.; Murillo-Franco, S.L.; Santos, M.C.M.; Silva, D.D.V.; Dussán, K.J. Acid Hydrolysis Pretreatment for Extraction of Oligosaccharides Derived from Spent Coffee Grounds: Valorization of a Promising Biomass. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komarova, M.I.; Semenova, M. V.; Volkov, P. V.; Shashkov, I.A.; Rozhkova, A.M.; Zorov, I.N.; Kurzeev, S.A.; Satrutdinov, A.D.; Rubtsova, E.A.; Sinitsyn, A.P. Efficient Hydrolysis of Sugar Beet Pulp Using Novel Enzyme Complexes. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, S.; Karlsson, E.N.; Adlercreutz, P. Extraction of Soluble Arabinoxylan from Enzymatically Pretreated Wheat Bran and Production of Short Xylo-Oligosaccharides and Arabinoxylo-Oligosaccharides from Arabinoxylan by Glycoside Hydrolase Family 10 and 11 Endoxylanases. J. Biotechnol. 2017, 260, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jovanovic-Malinovska, R.; Kuzmanova, S.; Winkelhausen, E. Application of Ultrasound for Enhanced Extraction of Prebiotic Oligosaccharides from Selected Fruits and Vegetables. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2015, 22, 446–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Li, Z.; Liu, Y. Ultrasonic-Assisted Extraction and Purification of Xylo-Oligosaccharides from Wheat Bran. J. Food Process Eng. 2022, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Amo-Mateos, E.; López-Linares, J.C.; García-Cubero, M.T.; Lucas, S.; Coca, M. Green Biorefinery for Sugar Beet Pulp Valorisation: Microwave Hydrothermal Processing for Pectooligosaccharides Recovery and Biobutanol Production. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrutia, F.; Adam, M.; Calvo-Carrascal, M.Á.; Mao, Y.; Binner, E. Development of a Continuous-Flow System for Microwave-Assisted Extraction of Pectin-Derived Oligosaccharides from Food Waste. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 395, 125056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, E.S.; Da Costa Lopes, A.M.; Freire, M.G.; Freire, C.S.R.; Coutinho, J.A.P.; Silvestre, A.J.D. Use of Ionic Liquids and Deep Eutectic Solvents in Polysaccharides Dissolution and Extraction Processes towards Sustainable Biomass Valorization. Molecules 2020, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usmani, Z.; Sharma, M.; Gupta, P.; Karpichev, Y.; Gathergood, N.; Bhat, R.; Gupta, V.K. Ionic Liquid Based Pretreatment of Lignocellulosic Biomass for Enhanced Bioconversion. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 304, 123003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravn, H.C.; Meyer, A.S. Chelating Agents Improve Enzymatic Solubilization of Pectinaceous Co-Processing Streams. Process Biochem. 2014, 49, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babbar, N.; Baldassarre, S.; Maesen, M.; Prandi, B.; Dejonghe, W.; Sforza, S.; Elst, K. Enzymatic Production of Pectic Oligosaccharides from Onion Skins. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 146, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhagwat, P.; Amobonye, A.; Singh, S.; Pillai, S. Deep Eutectic Solvents in the Pretreatment of Feedstock for Efficient Fractionation of Polysaccharides: Current Status and Future Prospects. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2022, 12, 171–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabarlatz, D.; Torras, C.; Garcia-Valls, R.; Montané, D. Purification of Xylo-Oligosaccharides from Almond Shells by Ultrafiltration. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2007, 53, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Han, Q.; Qiu, M.; Jiang, L.; Chen, X.; Fan, Y. Membrane Technologies for the Separation and Purification of Functional Oligosaccharides: A Review. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 346, 127463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imamoglu, E. Green Extraction Processes from Renewable Biomass to Sustainable Bioproducts. Bioresour. Technol. Reports 2024, 27, 101952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Andrés, M.; Aguilera-Torre, B.; García-Serna, J. Hydrothermal Production of High-Molecular Weight Hemicellulose-Pectin, Free Sugars and Residual Cellulose Pulp from Discarded Carrots. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, N.; Takano, Y.; Mizuno, M.; Nozaki, K.; Umemura, S.; Matsuzawa, T.; Amano, Y.; Makishima, S. Production of Feruloylated Arabino-Oligosaccharides (FA-AOs) from Beet Fiber by Hydrothermal Treatment. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2013, 79, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karbuz, P.; Tugrul, N. Microwave and Ultrasound Assisted Extraction of Pectin from Various Fruits Peel. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 58, 641–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campos, D.; Sánchez, J.; Aguilar-Galvez, A.; García-Ríos, D.; Chirinos, R.; Pedreschi, R. Ultrasound-Enhanced Enzymatic Hydrolysis for Efficient Production of Low Molecular Weight Oligogalacturonides from Polygalacturonic Acid. Food Biosci. 2025, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Sabajanes, M.; Yáñez, R.; Alonso, J.L.; Parajó, J.C. Pectic Oligosaccharides Production from Orange Peel Waste by Enzymatic Hydrolysis. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2012, 47, 747–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babbar, N.; Dejonghe, W.; Gatti, M.; Sforza, S.; Elst, K. Pectic Oligosaccharides from Agricultural By-Products: Production, Characterization and Health Benefits. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2016, 36, 594–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iqbal, M.W.; Riaz, T.; Mahmood, S.; Liaqat, H.; Mushtaq, A.; Khan, S.; Amin, S.; Qi, X. Recent Advances in the Production, Analysis, and Application of Galacto-Oligosaccharides. Food Rev. Int. 2023, 39, 5814–5843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garc, A.; Morales, P.C.; Wojtusik, M.; Santos, V.E.; Kovensky, J.; Ladero, M. Production of Oligosaccharides from Agrofood Wastes. Fermentation 2020, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Nordberg Karlsson, E.; Schmitz, E.; Linares-Pastén, J.A.; Adlercreutz, P. Endo-Xylanases as Tools for Production of Substituted Xylooligosaccharides with Prebiotic Properties. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 102, 9081–9088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linares-Pasten, J.A.; Aronsson, A.; Karlsson, E.N. Structural Considerations on the Use of Endo-Xylanases for the Production of Prebiotic Xylooligosaccharides from Biomass. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2016, 19, 48–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Combo, A.M.M.; Aguedo, M.; Goffin, D.; Wathelet, B.; Paquot, M. Enzymatic Production of Pectic Oligosaccharides from Polygalacturonic Acid with Commercial Pectinase Preparations. Food Bioprod. Process. 2012, 90, 588–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Han, T.; Liu, W.; He, J.; Liu, J. Pectic Oligosaccharides: Enzymatic Preparation, Structure, Bioactivities and Application. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 65, 2117–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ávila, P.F.; de Mélo, A.H.F.; Goldbeck, R. Cello-Oligosaccharides Production from Multi-Stage Enzymatic Hydrolysis by Lignocellulosic Biomass and Evaluation of Prebiotic Potential. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2023, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera, C.; Illanes, A.; Guerrero, C. Enzymatic Production of Prebiotic Oligosaccharides. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2021, 37, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Teng, Q.; Zhong, R.; Ye, Z.H. Arabidopsis GUX Proteins Are Glucuronyltransferases Responsible for the Addition of Glucuronic Acid Side Chains onto Xylan. Plant Cell Physiol. 2012, 53, 1204–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endo, M.; Kotake, T.; Watanabe, Y.; Kimura, K.; Tsumuraya, Y. Biosynthesis of the Carbohydrate Moieties of Arabinogalactan Proteins by Membrane-Bound β-Glucuronosyltransferases from Radish Primary Roots. Planta 2013, 238, 1157–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, M.C.C.; Dutra, L.; Fé, L.X.S.G.M.; Freire, D.M.G.; Manoel, E.A.; Cipolatti, E.P. Chapter 15 - Immobilized Biocatalysts for Hydrolysis of Polysaccharides. In Foundations and Frontiers in Enzymology; Goldbeck, R., Poletto, P.B.T.-P.-D.B., Eds.; Academic Press, 2023; pp. 385–407 ISBN 978-0-323-99986-1.

- Prado, S.B.R.; Beukema, M.; Jermendi, E.; Schols, H.A.; de Vos, P.; Fabi, J.P. Pectin Interaction with Immune Receptors Is Modulated by Ripening Process in Papayas. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vos, A.P.; M’Rabet, L.; Stahl, B.; Boehm, G.; Garssen, J. Immune-Modulatory Effects and Potential Working Mechanisms of Orally Applied Nondigestible Carbohydrates. Crit. Rev. Immunol. 2007, 27, 97–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, R.Y.; Määttänen, P.; Napper, S.; Scruten, E.; Li, B.; Koike, Y.; Johnson-Henry, K.C.; Pierro, A.; Rossi, L.; Botts, S.R.; et al. Non-Digestible Oligosaccharides Directly Regulate Host Kinome to Modulate Host Inflammatory Responses without Alterations in the Gut Microbiota. Microbiome 2017, 5, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zenhom, M.; Hyder, A.; de Vrese, M.; Heller, K.J.; Roeder, T.; Schrezenmeir, J. Prebiotic Oligosaccharides Reduce Proinflammatory Cytokines in Intestinal Caco-2 Cells via Activation of PPARγ and Peptidoglycan Recognition Protein 3. J. Nutr. 2011, 141, 971–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson-Henry, K.C.; Pinnell, L.J.; Waskow, A.M.; Irrazabal, T.; Martin, A.; Hausner, M.; Sherman, P.M. Short-Chain Fructo-Oligosaccharide and Inulin Modulate Inflammatory Responses and Microbial Communities in Caco2-Bbe Cells and in a Mouse Model of Intestinal Injury. J. Nutr. 2014, 144, 1725–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yang, L.; Xue, S.; Wang, S.; Zhu, L.; Ma, T.; Liu, H.; Li, R. Molecular Docking and Dynamic Insights on the Adsorption Effects of Soy Hull Polysaccharides on Bile Acids. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 57, 3702–3712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Li, Y.H.; Niu, Y.B.; Sun, Y.; Guo, Z.J.; Li, Q.; Li, C.; Feng, J.; Cao, S.S.; Mei, Q.B. An Apple Oligogalactan Prevents against Inflammation and Carcinogenesis by Targeting LPS/TLR4/NF-ΚB Pathway in a Mouse Model of Colitis-Associated Colon Cancer. Carcinogenesis 2010, 31, 1822–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, H.; Chen, W.; Liu, Q.; Yang, G.; Li, K. Pectin Oligosaccharides Ameliorate Colon Cancer by Regulating Oxidative Stress- and Inflammation-Activated Signaling Pathways. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Pan, X.; Ran, S.; Wang, K. Purification, Structural Elucidation and Anti-Inflammatory Activity in Vitro of Polysaccharides from Smilax China L. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 139, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerreiro, C. de A.; Andrade, L.A.D.; Fernández-Lainez, C.; Fraga, L.N.; López-Velázquez, G.; Marques, T.M.; Prado, S.B.R.; Brummer, R.J.; Nascimento, J.R.O.; Castro-Alves, V. Bioactive Arabinoxylan Oligomers via Colonic Fermentation and Enzymatic Catalysis: Evidence of Interaction with Toll-like Receptors from in Vitro, in Silico and Functional Analysis. Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; de Vos, P. Structure-Function Effects of Different Pectin Chemistries and Its Impact on the Gastrointestinal Immune Barrier System. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 65, 1201–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 114. Sahasrabudhe, N.M.; Beukema, M.; Tian, L.; Troost, B.; Scholte, J.; Bruininx, E.; Bruggeman, G.; van den Berg, M.; Scheurink, A.; Schols, H.A.; et al. Dietary Fiber Pectin Directly Blocks Toll-Like Receptor 2–1 and Prevents Doxorubicin-Induced Ileitis. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 383. [Google Scholar]

- Kikete, S.; Luo, L.; Jia, B.; Wang, L.; Ondieki, G.; Bian, Y. Plant-Derived Polysaccharides Activate Dendritic Cell-Based Anti-Cancer Immunity. Cytotechnology 2018, 70, 1097–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, D.A.; Fadden, A.J.; Drickamer, K. A Novel Mechanism of Carbohydrate Recognition by the C-Type Lectins DC-SIGN and DC-SIGNR. Subunit Organization and Binding to Multivalent Ligands. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 28939–28945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huo, R.; Wuhanqimuge; Zhang, M. ; Sun, M.; Miao, Y. Molecular Dynamics Modeling of Different Conformations of Beta-Glucan, Molecular Docking with Dectin-1, and the Effects on Macrophages. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 293, 139382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendis, M.; Leclerc, E.; Simsek, S. Arabinoxylan Hydrolyzates as Immunomodulators in Lipopolysaccharide-Induced RAW264.7 Macrophages. Food Funct. 2016, 7, 3039–3045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bermudez-Brito, M.; Sahasrabudhe, N.M.; Rösch, C.; Schols, H.A.; Faas, M.M.; de Vos, P. The Impact of Dietary Fibers on Dendritic Cell Responses in Vitro Is Dependent on the Differential Effects of the Fibers on Intestinal Epithelial Cells. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2015, 59, 698–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendis, M.; Leclerc, E.; Simsek, S. Arabinoxylan Hydrolyzates as Immunomodulators in Caco-2 and HT-29 Colon Cancer Cell Lines. Food Funct. 2017, 8, 220–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mavrogeni, M.E.; Asadpoor, M.; Henricks, P.A.J.; Keshavarzian, A.; Folkerts, G.; Braber, S. Direct Action of Non-Digestible Oligosaccharides against a Leaky Gut. Nutrients 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabater, C.; Molina-Tijeras, J.A.; Vezza, T.; Corzo, N.; Montilla, A.; Utrilla, P. Intestinal Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Artichoke Pectin and Modified Pectin Fractions in the Dextran Sulfate Sodium Model of Mice Colitis. Artificial Neural Network Modelling of Inflammatory Markers. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 7793–7805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabater, C.; Blanco-Doval, A.; Margolles, A.; Corzo, N.; Montilla, A. Artichoke Pectic Oligosaccharide Characterisation and Virtual Screening of Prebiotic Properties Using in Silico Colonic Fermentation. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 255, 117367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meijerink, M.; Rösch, C.; Taverne, N.; Venema, K.; Gruppen, H.; Schols, H.A.; Wells, J.M. Structure Dependent-Immunomodulation by Sugar Beet Arabinans via a SYK Tyrosine Kinase-Dependent Signaling Pathway. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro-Alves, V.C.; Nascimento, J.R.O. do Size Matters: TLR4-Mediated Effects of α-(1,5)-Linear Arabino-Oligosaccharides in Macrophage-like Cells Depend on Their Degree of Polymerization. Food Res. Int. 2021, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beukema, M.; Jermendi; van den Berg, M. A.; Faas, M.M.; Schols, H.A.; de Vos, P. The Impact of the Level and Distribution of Methyl-Esters of Pectins on TLR2-1 Dependent Anti-Inflammatory Responses. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 251, 117093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuso, A.; Rosso, F.; Rosso, G.; Risso, D.; Manera, I.; Caligiani, A. Production of Xylo-Oligosaccharides (XOS) of Tailored Degree of Polymerization from Acetylated Xylans through Modelling of Enzymatic Hydrolysis. Food Res. Int. 2022, 162, 112019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, H.Y.; Chen, Y.K.; Chen, H.H.; Lin, S.Y.; Fang, Y.T. Immunomodulatory Effects of Feruloylated Oligosaccharides from Rice Bran. Food Chem. 2012, 134, 836–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akshatha, S.; Gnanesh Kumar, B.S.; Mazumder, K.; Eligar, S.M. Structural Characterization and Bioactivities of Maize Bran Feruloylated Arabinoxylan and Oligosaccharides Obtained by a Combined Hydrothermal and Enzymatic Pre-Treatment. Food Biosci. 2024, 60, 104417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landy, J.; Ronde, E.; English, N.; Clark, S.K.; Hart, A.L.; Knight, S.C.; Ciclitira, P.J.; Al-Hassi, H.O. Tight Junctions in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases and Inflammatory Bowel Disease Associated Colorectal Cancer. World J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 22, 3117–3126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Candelli, M.; Franza, L.; Pignataro, G.; Ojetti, V.; Covino, M.; Piccioni, A.; Gasbarrini, A.; Franceschi, F. Interaction between Lipopolysaccharide and Gut Microbiota in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neyrinck, A.M.; Van Hée, V.F.; Piront, N.; De Backer, F.; Toussaint, O.; Cani, P.D.; Delzenne, N.M. Wheat-Derived Arabinoxylan Oligosaccharides with Prebiotic Effect Increase Satietogenic Gut Peptides and Reduce Metabolic Endotoxemia in Diet-Induced Obese Mice. Nutr. Diabetes 2012, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamiya, T.; Shikano, M.; Tanaka, M.; Ozeki, K.; Ebi, M.; Katano, T.; Hamano, S.; Nishiwaki, H.; Tsukamoto, H.; Mizoshita, T.; et al. Therapeutic Effects of Biobran, Modified Arabinoxylan Rice Bran, in Improving Symptoms of Diarrhea Predominant or Mixed Type Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Pilot, Randomized Controlled Study. Evidence-based Complement. Altern. Med. 2014, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohm, T. V.; Meier, D.T.; Olefsky, J.M.; Donath, M.Y. Inflammation in Obesity, Diabetes, and Related Disorders. Immunity 2022, 55, 31–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, X.; Wang, L.; Wang, Z.; Wan, C. Toll-like Receptor 4 Plays a Vital Role in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Scoping Review. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turck, D.; Bohn, T.; Castenmiller, J.; De Henauw, S.; Hirsch-Ernst, K.I.; Maciuk, A.; Mangelsdorf, I.; McArdle, H.J.; Naska, A.; Pelaez, C.; et al. Safety of the Extension of Use of Galacto-Oligosaccharides (GOS) as a Novel Food in Food for Special Medical Purposes Pursuant to Regulation (EU) 2015/2283. EFSA J. 2022, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turck, D.; Bresson, J.L.; Burlingame, B.; Dean, T.; Fairweather-Tait, S.; Heinonen, M.; Hirsch-Ernst, K.I.; Mangelsdorf, I.; McArdle, H.J.; Naska, A.; et al. Safety of Xylo-Oligosaccharides (XOS) as a Novel Food Pursuant to Regulation (EU) 2015/2283. EFSA J. 2018, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bührer, C.; Ensenauer, R.; Jochum, F.; Kalhoff, H.; Koletzko, B.; Lawrenz, B.; Mihatsch, W.; Posovszky, C.; Rudloff, S. Infant Formulas with Synthetic Oligosaccharides and Respective Marketing Practices. Mol. Cell. Pediatr. 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turck, D.; Bohn, T.; Castenmiller, J.; de Henauw, S.; Hirsch-Ernst, K.I.; Maciuk, A.; Mangelsdorf, I.; McArdle, H.J.; Naska, A.; Pentieva, K.; et al. Guidance on the Scientific Requirements for an Application for Authorisation of a Novel Food in the Context of Regulation (EU) 2015/2283. EFSA J. 2024, 22, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pomeranz, J.L.; Broad Leib, E.M.; Mozaffarian, D. Regulation of Added Substances in the Food Supply by the Food and Drug Administration Human Foods Program. Am. J. Public Health 2024, 114, 1061–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forgo, P.; Kiss, A.; Korózs, M.; Rapi, S. Thermal Degradation and Consequent Fragmentation of Widely Applied Oligosaccharides. Microchem. J. 2013, 107, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, J.M. The Food Matrix: Implications in Processing, Nutrition and Health. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 59, 3612–3629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Extraction Method. | Main processing stage |

Target material |

Main solvents/enzymes used |

Special properties/ Comments |

Examples/Sources |

| Hot water extraction (HWE) | Extraction | Polysaccharides, some oligosaccharides | Water (90–160°C) | Eco-friendly, good for heat-stable material | [52,63] |

| Subcritical water extraction (SWE) | Extraction | Hemicellulosic material (recalcitrant) | Water (>100°C) and pressure (> 10 bar) | Alternative to HWE for recalcitrant material | [31,69] |

| Alkaline extraction | Extraction | Hemicelluloses, lignin removal | NaOH, Ca(OH)₂, others |

Solubilizes hemicellulose, effective lignin disruption | [52,68] |

| Acid hydrolysis | Extraction | Pectic/hemicellulosic oligosaccharides | H₂SO₄, H₃PO₄, others |

Effective but harsh; degradation risk | [70,71] |

| Enzymatic hydrolysis | Hydrolysis or conversion | Oligosaccharides (FOS, XOS, GOS, etc.) | Xylanase, Cellulase, Pectinase, others | Mild, specific, avoids toxic residues | [72,73] |

| Ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE) | Extraction enhancement | Polysaccharides and oligosaccharides | Water, mechanical agitation | Enhances diffusion, reduces energy/time | [74,75] |

| Microwave-assisted extraction (MAE) | Extraction enhancement | Polysaccharides and oligosaccharides | Water/solvent, microwave radiation | Fast, efficient; high energy input | [76,77] |

| Ionic liquid pretreatment | Pretreatment | Cellulose, lignin, hemicelluloses | EMIM Ac, others | Efficient delignification; recovery needed | [78,79] |

| Chelating agent | Pretreatment | Pectin/rich biomass, crosslinked polysaccharides | EDTA, citric acid, others | Removes metal ions, disrupts Ca2⁺ bridges in pectins | [80,81] |

| Deep eutectic solvent (DES) extraction | Pretreatment | Lignin, hemicelluloses | Choline chloride + lactic acid, urea, others | Biodegradable, tunable solvent properties | [78,82] |

| (Tangential flow) filtration (TFF) | Isolation or fractionation | Fractionation of solubilized saccharides | Membrane-based size separation | Industrial-scale separation of high/low MW fractions | [83,84] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).