Submitted:

20 July 2025

Posted:

22 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The Hierarchy of Applied Cognition

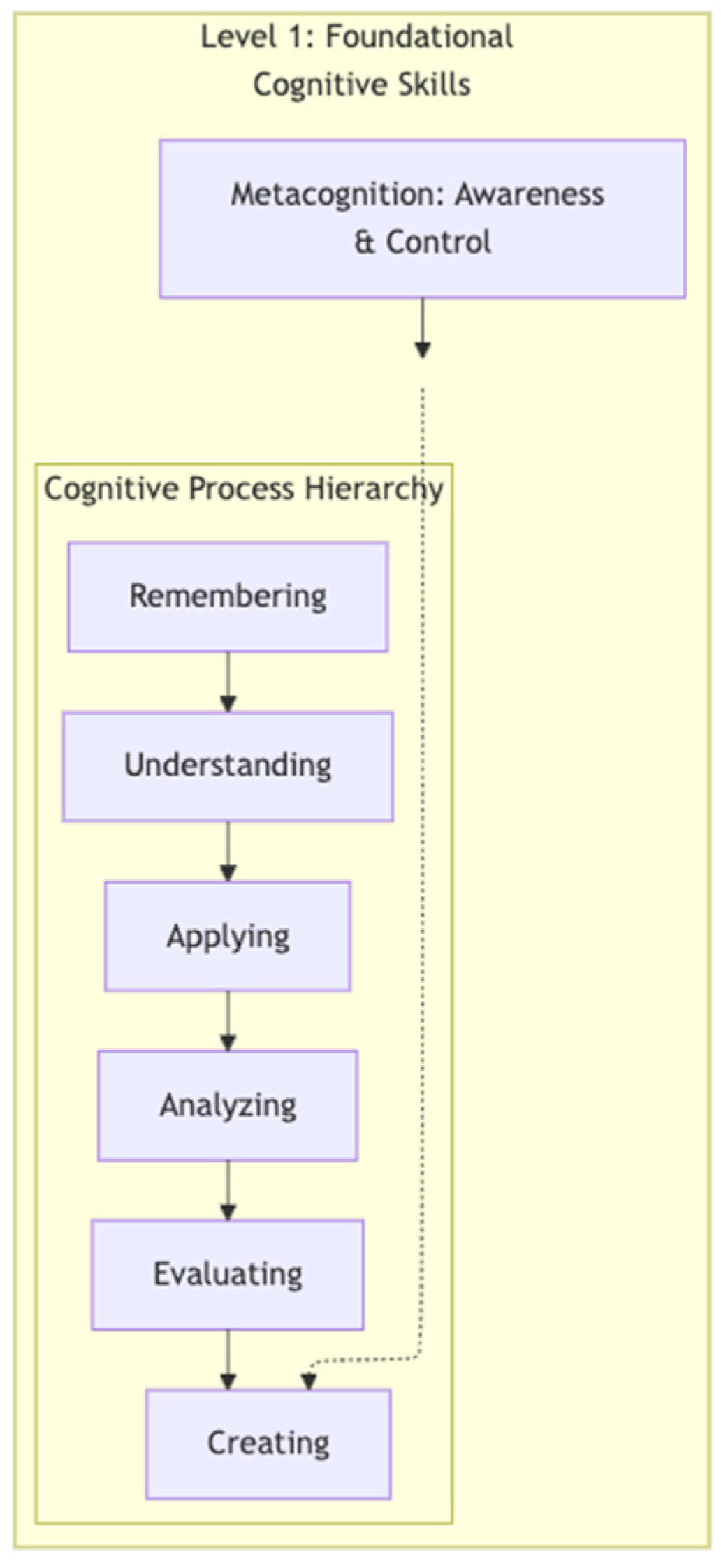

2.1. Level 1: Foundational Cognitive Skills

- Remembering: This is the most basic cognitive skill, involving the retrieval, recognition, and recall of relevant knowledge from long-term memory. It is the foundation upon which all other levels of thinking depend, as one cannot understand or apply knowledge that cannot be recalled (Anderson & Krathwohl, 2001).

- Understanding: This skill involves constructing meaning from various types of information, including oral, written, and graphic messages. The process goes beyond simple recall to include interpreting, exemplifying, classifying, summarizing, inferring, comparing, and explaining. Achieving deep conceptual understanding, rather than rote memorization, is a primary goal of effective learning (Sawyer, 2022).

- Applying: Application refers to the ability to use learned information, procedures, or principles in a new and concrete situation. This skill acts as a bridge between theoretical knowledge and practical problem-solving. The capacity to transfer learning from one context to another is a key indicator of a robust and flexible knowledge base (Perkins & Salomon, 1992).

- Analyzing: This is a higher-order skill that involves breaking down information into its constituent parts to explore relationships and organizational structures. It includes differentiating, organizing, and attributing, allowing the thinker to distinguish between relevant and irrelevant information and to understand how components fit together to form a whole (Anderson & Krathwohl, 2001). Analytical reasoning is a cornerstone of logical and critical thought.

- Evaluating: Evaluation involves making judgments based on criteria and standards. This skill is highly dependent on the preceding ones, as one must first analyze information to evaluate it effectively. It includes checking for inconsistencies or fallacies in an argument and critiquing a work based on specific criteria. The development of evaluative judgement is considered a critical outcome of higher education (Tai et al., 2018).

- Creating: Positioned at the apex of the taxonomy, creating involves putting elements together to form a coherent, functional, or original whole. This can include generating hypotheses, designing experiments, or producing a novel piece of work. It is the essence of innovation and requires a convergence of all other cognitive skills (Anderson & Krathwohl, 2001; OECD, 2022).

- Metacognition: Overarching all these skills is metacognition, often defined as thinking about one’s thinking (Flavell, 1979). It involves the awareness, knowledge, and control of one’s own cognitive processes. This includes planning an approach to a task, monitoring comprehension, and evaluating the effectiveness of one’s strategies. Metacognition is essential for self-regulated learning and is a powerful predictor of academic and problem-solving success (Zimmerman & Schunk, 2011; Zohar & Dori, 2012).

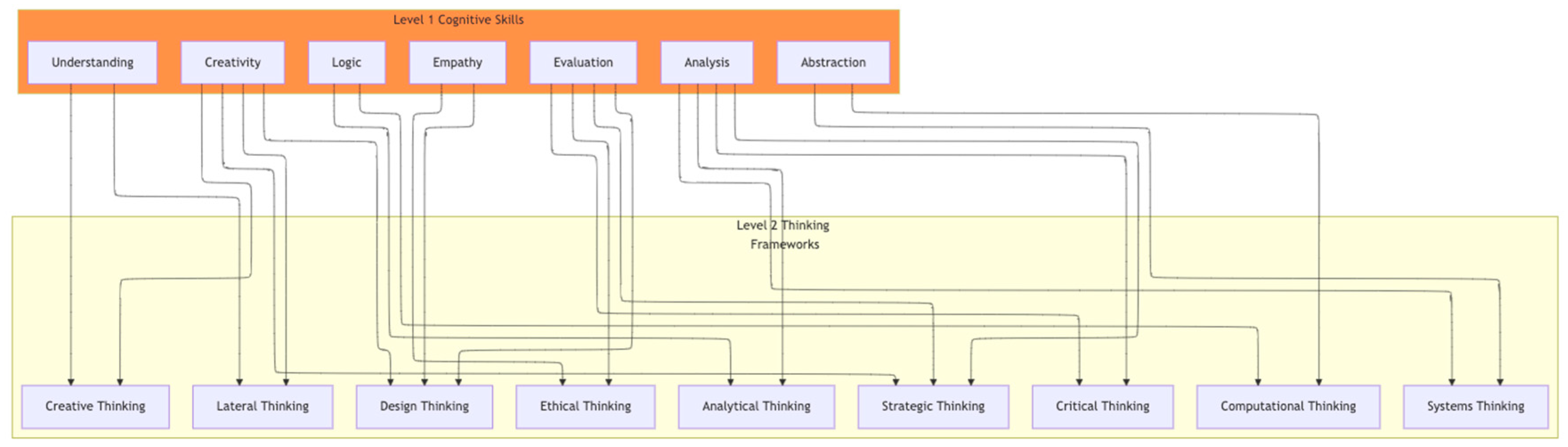

2.2. Level 2: Applied Thinking Frameworks

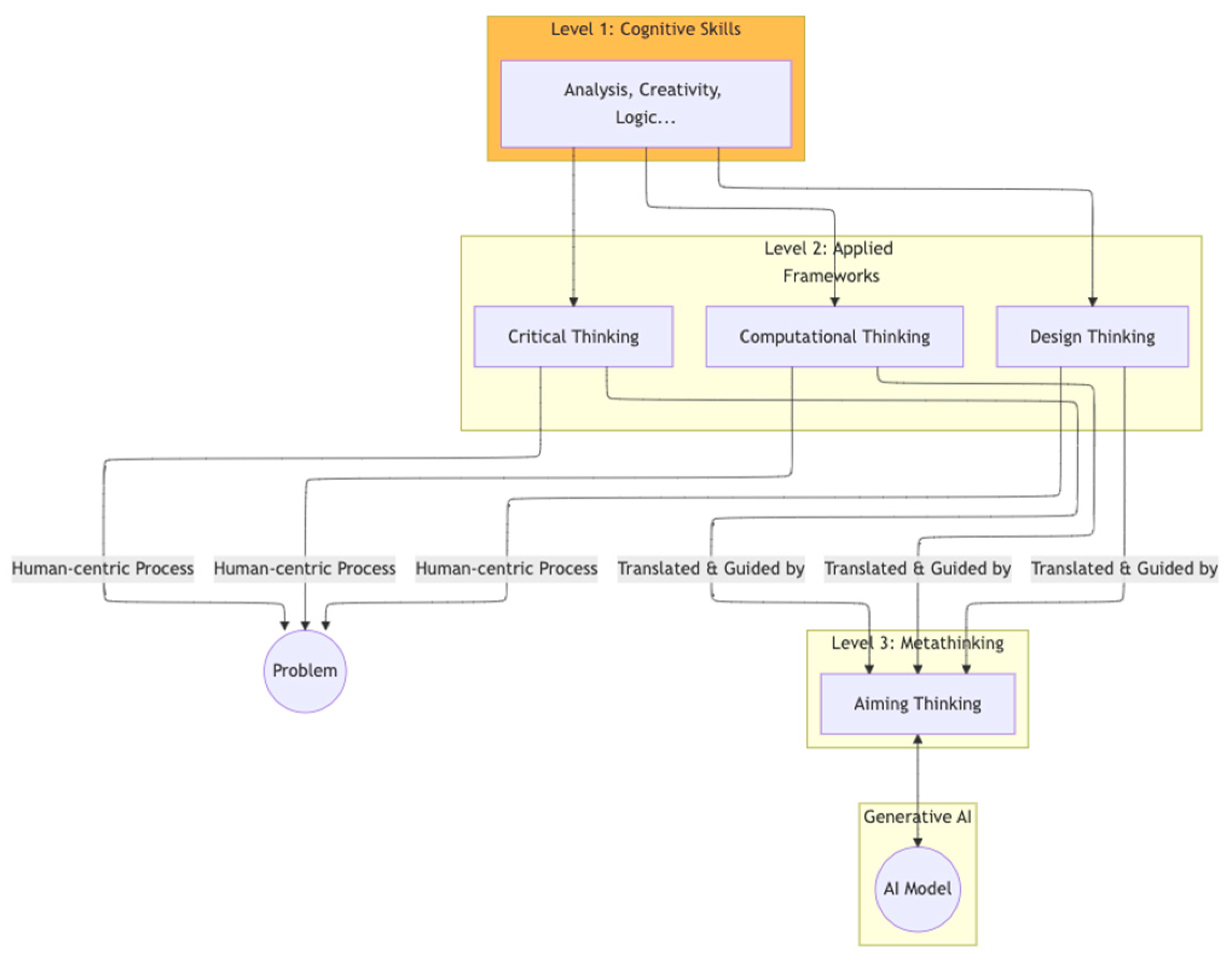

3. Aiming Thinking: The Metathinking Framework for the AI Era

3.1. Defining Aiming Thinking as a Level 3 Metathinking

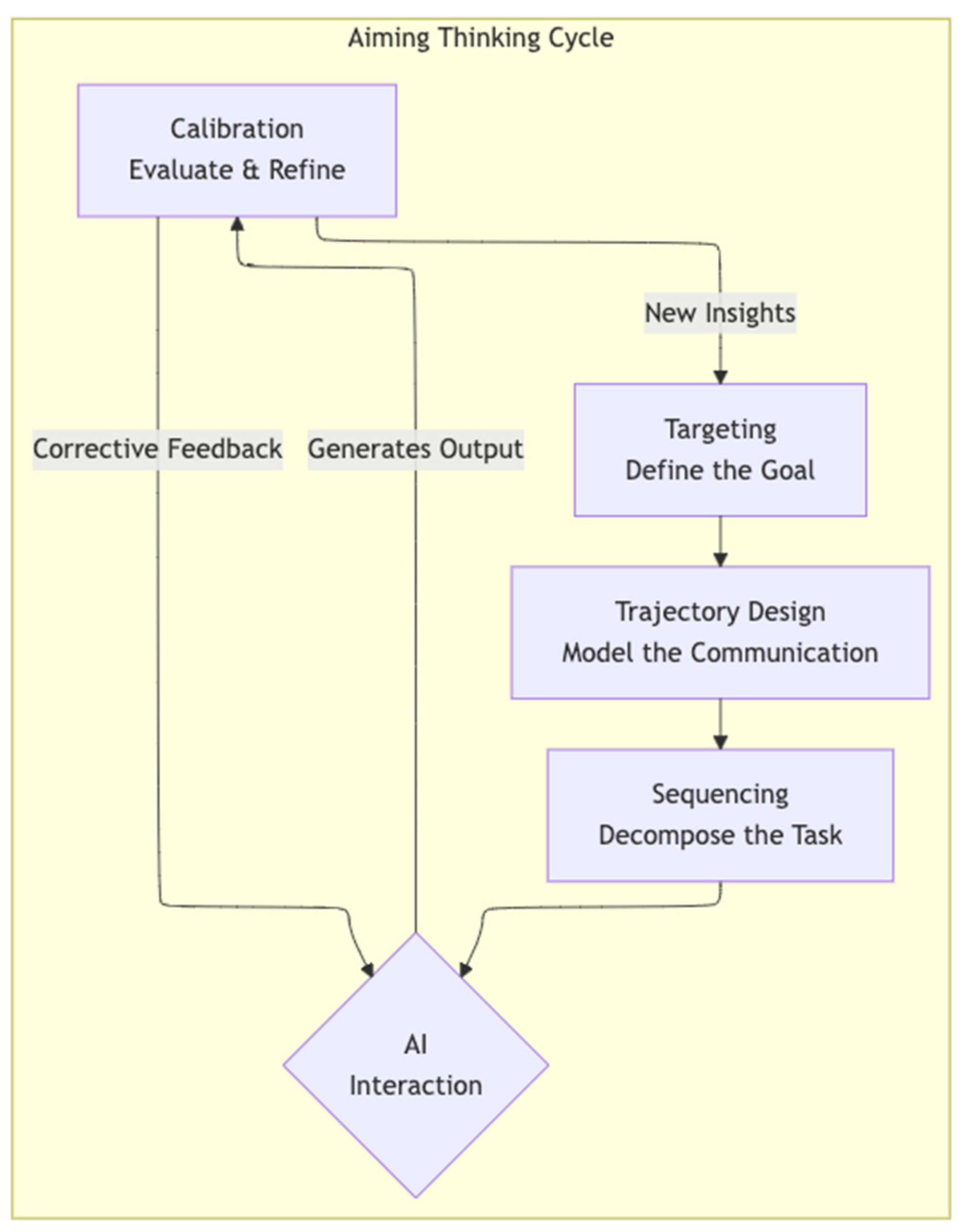

3.2. The Four Pillars of Aiming Thinking

4. The Aiming Thinking Pattern Library

4.1. Patterns for Targeting

Goal and Scope Definition Patterns

-

The Success Definition Pattern

- -

- Problem Context: A user receives a response that is technically correct but does not meet their implicit quality standards or needs (e.g., a summary that is too long, a list that is not prioritized).

- -

- What it Solves: It forces the user to externalize and define their criteria for a good outcome upfront, making success measurable and the AI’s task clearer.

- -

- Generic Application: Begin a prompt by explicitly stating the conditions or characteristics of a successful output.

- -

- Practical Example: I need a title for a blog post about productivity. Success for this task is a title that is under 10 words, creates a sense of urgency, and includes the keyword ‘focus’.

-

The Scope Fencing Pattern

- -

- Problem Context: The AI provides information that is too broad, including irrelevant details or tangential topics that dilute the core message.

- -

- What it Solves: It narrows the AI’s search and generation space, forcing it to concentrate only on what is essential and preventing scope creep.

- -

- Generic Application: Use explicit phrases like Focus only on…, Do not discuss…, or Confine your answer to the period between… to set hard boundaries.

- -

- Practical Example: Explain the causes of the American Revolution. Focus only on the economic factors and do not discuss military or social aspects.

Context and Constraint Setting Patterns

-

The Core Context Pattern

- -

- Problem Context: The AI’s response is generic and lacks relevance because it is unaware of the background or the situation that prompted the request.

- -

- What it Solves: It provides the AI with a situational awareness, allowing it to tailor the response to be more applicable and useful.

- -

- Generic Application: Start the prompt with a brief paragraph labeled Context: that explains the scenario before making the request.

- -

- Practical Example: Context: I am a software manager preparing for a quarterly performance review with a junior developer who has shown great progress but struggles with time management. Based on this, generate three positive feedback points and one constructive suggestion.

-

The Audience Persona Pattern

- -

- Problem Context: The AI generates a response with a level of complexity, tone, or jargon that is inappropriate for the intended end-user.

- -

- What it Solves: It forces the AI to adapt its output to a specific reader, dramatically improving the response’s readability and impact.

- -

- Generic Application: Include a clear statement defining the target audience, such as The audience is… or Explain this to a….

- -

- Practical Example: Explain how a blockchain works. The audience is a group of high school students with no prior technical knowledge, so use simple analogies.

-

The Negative Constraint Pattern

- -

- Problem Context: The AI repeatedly includes undesirable elements in its response (e.g., clichés, specific words, overly complex solutions).

- -

- What it Solves: It provides explicit anti-goals, giving the AI clear instructions on what to avoid, which is often easier for it to follow than abstract positive commands.

- -

- Generic Application: Add a clear instruction stating what not to do, such as Do not use…, Avoid mentioning…, or Do not suggest solutions that require….

- -

- Practical Example: Generate marketing slogans for a new coffee brand. Do not use the words ‘fresh,’ ‘best,’ or ‘aroma’.

4.2. Patterns for Trajectory Design

Instructional Modeling Patterns

-

The Persona Pattern

- -

- Problem Context: The AI’s default persona is often neutral, generic, and unauthoritative, leading to bland or unspecialized responses.

- -

- What it Solves: It instructs the AI to adopt a specific role or character, which instantly frames its knowledge, tone, and style to be more expert and relevant.

- -

- Generic Application: Begin the prompt with the phrase Act as a… or You are a….

- -

- Practical Example: Act as a seasoned financial advisor. Review the following investment portfolio and identify its main strengths and weaknesses.

-

The Master Example Pattern (Few-Shot)

- -

- Problem Context: Explaining a desired format or style with words alone can be ambiguous and lead to incorrect interpretations by the AI.

- -

- What it Solves: It provides a concrete, unambiguous demonstration of the desired output, allowing the AI to learn the pattern by example (Brown et al., 2020).

- -

- Generic Application: Provide one or more complete examples of the input-output pairing before giving the final instruction.

- -

- Practical Example: Translate the following sentences into French in a formal tone. Example: ‘Hey, what’s up?’ -> ‘Bonjour, comment allez-vous?’. Now, translate: ‘We need to talk.’

-

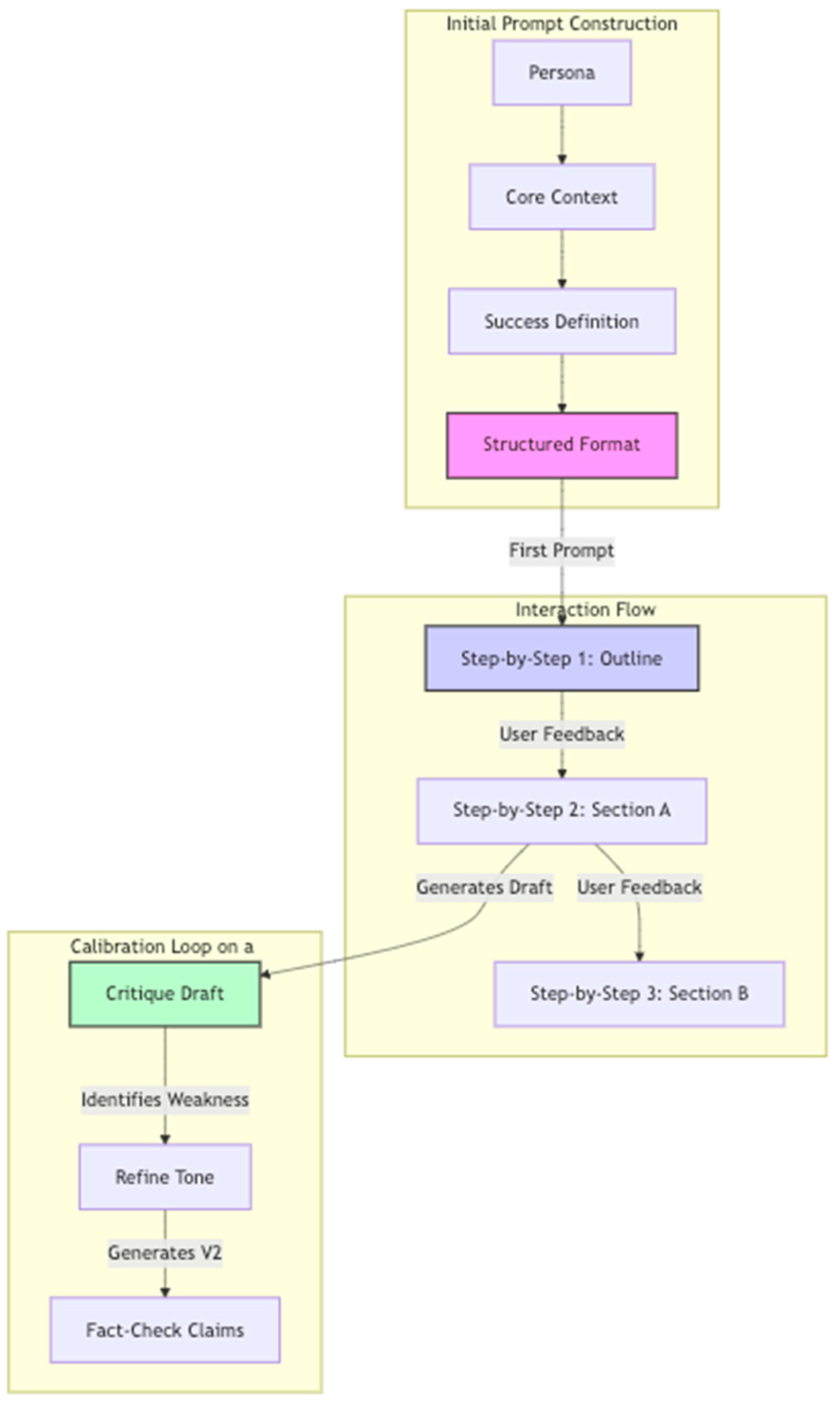

The Structured Format Pattern

- -

- Problem Context: The user needs the output in a format that can be easily parsed by another software or used in a structured document, but the AI defaults to prose.

- -

- What it Solves: It commands the AI to generate its response in a machine-readable format like JSON, XML, or a human-readable structured format like Markdown.

- -

- Generic Application: End the prompt with Provide the response in [FORMAT] format.

- -

- Practical Example: List three project management software options with their pros and cons. Provide the response as a Markdown table.

Content Specification Patterns

-

The Recipe Pattern

- -

- Problem Context: The user needs to ensure that specific key concepts, names, or pieces of information are included in the final response.

- -

- What it Solves: It provides the AI with a checklist of mandatory ingredients, preventing omissions and ensuring the output covers all critical points.

- -

- Generic Application: Include a phrase like Ensure you include the following concepts: A, B, and C.

- -

- Practical Example: Write a summary of the theory of relativity. Ensure you include the concepts of special relativity, general relativity, and the equation E=mc².

-

The Perspective Shift Pattern

- -

- Problem Context: A one-sided or single-perspective analysis is insufficient for a complex topic that requires a holistic understanding.

- -

- What it Solves: It forces the AI to act as a multiperspectival synthesizer, exploring an issue from different angles to provide a more nuanced and comprehensive overview.

- -

- Generic Application: Instruct the AI to analyze a topic from a list of specified viewpoints.

- -

- Practical Example: Analyze the proposal to switch to a four-day work week. First, present the argument from the perspective of an employee. Second, from the perspective of the CEO. Third, from the perspective of a customer.

4.3. Patterns for Sequencing

Task Decomposition Patterns

-

The Step-by-Step Construction Pattern

- -

- Problem Context: Asking the AI to generate a large or complex artifact (e.g., a full report, a software program) in one go often results in a low-quality, incomplete, or incoherent output.

- -

- What it Solves: It breaks the creation process into logical parts, allowing the user to approve and guide each component before moving to the next, ensuring high quality throughout.

- -

- Generic Application: Engage in a series of prompts, each one asking for the next logical part of the whole.

- -

- Practical Example: (1) ‘Create a detailed outline for a business plan.’ (2) ‘Great. Now write the ’Executive Summary’ section based on that outline.’ (3) ‘Perfect. Next, write the ’Market Analysis’ section.’

-

The Topic Expansion Pattern

- -

- Problem Context: The user is not sure what sub-topics are important within a larger theme and wants to explore before committing to a structure.

- -

- What it solves: It allows for an exploratory approach where the user can get a high-level overview first and then dive deeper into the most interesting or relevant points.

- -

- Generic Application: Start by asking for a list or overview, then follow up by asking for more detail on a specific item from that list.

- -

- Practical Example: (1) ‘What were the main schools of thought in ancient Greek philosophy?’ -> AI lists Stoicism, Epicureanism, etc. (2) ‘Tell me more about the core tenets of Stoicism.’

Process Structuring Patterns

-

The Chain-of-Thought Pattern

- -

- Problem Context: For problems requiring logic, math, or multi-step reasoning, the AI may jump to an incorrect conclusion without showing its work.

- -

- What it Solves: It forces the AI to externalize its reasoning process, which has been shown to significantly improve the accuracy of its conclusions (Wei et al., 2022). It allows the user to debug the AI’s logic.

- -

- Generic Application: Append the instruction Think step-by-step or Show your reasoning before giving the final answer.

- -

- Practical Example: A bat and a ball cost $1.10 in total. The bat costs $1.00 more than the ball. How much does the ball cost? Show your reasoning step-by-step.

-

The Funneling Pattern

- -

- Problem Context: When brainstorming, a user needs to move from a wide array of possibilities to a single, refined choice, but struggles to manage the process.

- -

- What it Solves: It structures the creative process into a classic divergent-convergent cycle, using the AI for both large-scale idea generation and criteria-based filtering.

- -

- Generic Application: Use a sequence of prompts that first asks for many ideas, then asks to filter them based on criteria, and finally asks for a detailed analysis of the top choice.

- -

- Practical Example: (1) ‘Generate 30 names for a new tech startup.’ (2) ‘From that list, select the 5 that are easiest to spell and remember.’ (3) ‘For those 5, which one best implies ’speed and reliability’?’

-

The Template Builder Pattern

- -

- Problem Context: The user repeatedly needs to create documents or inputs with the same structure, a tedious and repetitive task.

- -

- What it Solves: It leverages the AI to create a reusable template or scaffold that the user can then quickly fill out for future tasks.

- -

- Generic Application: Ask the AI to create a template for a specific purpose, using placeholders for variable content.

- -

- Practical Example: Create a reusable project update email template. Include placeholders in brackets for [Project Name], [Key Accomplishments], [Next Steps], and [Blockers].

4.4. Patterns for Calibration

Output Refinement Patterns

-

The Tone Refinement Pattern

- -

- Problem Context: The AI-generated text has the right information but the wrong style, voice, or level of formality for the intended context.

- -

- What it Solves: It allows the user to quickly and efficiently alter the stylistic properties of a text without having to re-generate the core information.

- -

- Generic Application: After a response is generated, give a command like Make it more…, Rewrite this but in a… tone, or Adjust the style to be….

- -

- Practical Example: (After the AI generates a business email) Make this more casual and friendly. or Rewrite this with a more authoritative and formal tone.

-

The Reformatting Pattern

- -

- Problem Context: The AI provides information in a prose paragraph, but the user realizes it would be more effective or easier to understand in a different layout.

- -

- What it Solves: It restructures existing content into a more effective format (e.g., list, table, summary) without losing the information.

- -

- Generic Application: Take a previous AI response and ask to Convert this into…, Summarize this as…, or Reformat this as a….

- -

- Practical Example: (After the AI provides a long explanation) Summarize the key points of your previous response in five bullet points.

-

The Merge & Synthesize Pattern

- -

- Problem Context: The user has generated several good pieces of information across multiple prompts but needs to combine them into a single, coherent text.

- -

- What it Solves: It uses the AI’s ability to understand context from a conversation to synthesize disparate pieces of information into a unified whole.

- -

- Generic Application: Refer to previous parts of the conversation and ask the AI to combine them.

- -

- Practical Example: Take the market analysis from our earlier conversation and the three marketing slogans you just generated and write a single paragraph that introduces the product and its target market.

Quality Assurance Patterns

-

The Self-Critique Pattern

- -

- Problem Context: An AI-generated response may seem plausible but contain subtle flaws, biases, or weaknesses in its argument that are not immediately obvious.

- -

- What it Solves: It forces the AI to switch from a generator role to an evaluator role, using its own knowledge to find faults in its previous output, a process that can surface valuable insights.

- -

- Generic Application: Ask the AI to Critique your previous response, What are the weaknesses of this argument?, or Play devil’s advocate against your own point.

- -

- Practical Example: (After the AI proposes a business strategy) Identify three potential risks or downsides to the strategy you just outlined.

-

The Fact-Checking Pattern

- -

- Problem Context: Generative AI models are known to hallucinate or invent facts, statistics, and citations, making their outputs unreliable for factual claims (Ji et al., 2023).

- -

- What it Solves: It creates a routine practice of questioning the AI’s claims, asking for sources, and treating all factual statements as claims to be verified rather than truths to be accepted.

- -

- Generic Application: Follow up any factual claim with questions like What is the source for that statistic?, Can you provide a reference for that claim?, or Verify that this person actually said this.

- -

- Practical Example: (After the AI states, Studies show 80% of customers prefer X) Which specific studies show that 80% of customers prefer X? Please provide citations if possible.

5. Bridging the Gap: Mapping Applied Frameworks to Aiming Thinking

5.1. Conceptual Mapping of Level 2 Frameworks to Aiming Thinking

Computational Thinking (CT) to Aiming Thinking (AT)

| Computational Thinking Concept | Mapped to Aiming Thinking Pillar/Pattern |

| Decomposition | Sequencing: The Step-by-Step Construction and Topic Expansion patterns are direct applications of decomposition in a conversational flow. |

| Pattern Recognition | Trajectory Design: Identifying a problem type and selecting the appropriate Persona or Master Example pattern is a form of pattern recognition. |

| Abstraction | Targeting / Trajectory Design: Defining a clear goal while ignoring irrelevant details (Scope Fencing) is abstraction. Using a Persona is abstracting a role. |

| Algorithm Design | Sequencing / Targeting: The entire sequence of prompts forms a natural language algorithm. The Success Definition pattern defines the algorithm’s goal. |

Design Thinking (DT) to Aiming Thinking (AT)

| Design Thinking Stage | Mapped to Aiming Thinking Pillar/Pattern |

| Empathize | Targeting: The Audience Persona and Core Context patterns are used to define the user’s needs and situation for the AI. |

| Define | Targeting: The Success Definition pattern is used to frame the problem statement or Point of View as a clear objective for the AI. |

| Ideate | Sequencing: The Funneling Pattern perfectly models the divergent (brainstorming) and convergent (filtering) phases of ideation. |

| Prototype | Calibration: Every output generated by the AI is effectively an instant, low-fidelity prototype ready for immediate feedback. |

| Test | Calibration: The user tests the AI-generated prototype by applying Self-Critique or using it in a thought experiment, then provides feedback. |

Critical Thinking (CTr) to Aiming Thinking (AT)

| Critical Thinking Concept (Paul-Elder) | Mapped to Aiming Thinking Pillar/Pattern |

| Elements of Thought (Purpose, Question) | Targeting: Clearly defining the objective and the core question at hand. |

| Intellectual Standards (Clarity, Accuracy) | Calibration: The Fact-Checking and refinement patterns hold the AI’s output to these standards. |

| Analyzing Arguments | Sequencing / Calibration: Using Chain-of-Thought to dissect the AI’s logic and Self-Critique to find flaws in its reasoning. |

| Evaluating Evidence | Calibration: The core function of the Fact-Checking Pattern. |

Systems Thinking (ST) to Aiming Thinking (AT)

| Systems Thinking Concept | Mapped to Aiming Thinking Pillar/Pattern |

| Seeing Interconnections | Sequencing: Asking a series of what if questions to explore how a change in one part of the system affects others. |

| Identifying Feedback Loops | Calibration: After the AI describes an outcome, asking What are the potential unintended consequences of this? to uncover feedback loops. |

| Finding Leverage Points | Trajectory Design: Crafting a Persona or Core Context that forces the AI to focus on high-impact areas of a system. |

| Understanding Dynamic Behavior | Sequencing: Modeling the evolution of a system over time by asking for outcomes at Time+1, Time+2, etc. |

Strategic Thinking (STr) to Aiming Thinking (AT)

| Strategic Thinking Element (Liedtka) | Mapped to Aiming Thinking Pillar/Pattern |

| Systems Perspective | Trajectory Design: The Perspective Shift Pattern can be used to analyze the strategic landscape from the view of competitors, customers, and regulators. |

| Intent-Focus | Targeting: The Success Definition and Core Context patterns ensure all AI-generated outputs are aligned with the overarching strategic intent. |

| Intelligent Opportunism | Calibration: The feedback loop allows the strategist to pivot and explore unexpected opportunities that arise from the AI’s responses. |

| Hypothesis-Driven | Sequencing / Calibration: Generating a strategic hypothesis, using the AI to test it against data or scenarios, and then Calibrating based on the results. |

Creative Thinking (CrT) to Aiming Thinking (AT)

| Creative Thinking Process | Mapped to Aiming Thinking Pillar/Pattern |

| Divergent Thinking (Generating ideas) | Sequencing: The first step of the Funneling Pattern is used to generate a large quantity of ideas without judgment. |

| Convergent Thinking (Filtering ideas) | Sequencing / Calibration: The subsequent steps of the Funneling Pattern use criteria to filter ideas. Calibration refines the best ones. |

| Incubation (Stepping away) | N/A (This remains a human cognitive process, though the AI can hold the context of a project indefinitely). |

| Verification (Developing the idea) | Sequencing: The Step-by-Step Construction Pattern is used to flesh out a selected creative idea into a full concept. |

Analytical Thinking (ATy) to Aiming Thinking (AT)

| Analytical Thinking Stage | Mapped to Aiming Thinking Pillar/Pattern |

| Identifying the Problem | Targeting: Defining a precise, answerable question. |

| Gathering Information | Sequencing / Calibration: Asking the AI to summarize sources, extract key data points, and using Fact-Checking to verify information. |

| Analyzing Information | Trajectory Design: Using Structured Format to organize data logically (e.g., in tables). Using Chain-of-Thought to have the AI explain its analysis. |

| Drawing Conclusions | Calibration: The human analyst critically evaluates the AI’s preliminary conclusions, using the Self-Critique pattern to challenge them. |

Lateral Thinking (LT) to Aiming Thinking (AT)

| Lateral Thinking Technique | Mapped to Aiming Thinking Pillar/Pattern |

| Challenging Assumptions | Calibration: Using the Self-Critique pattern with a prompt like What are the core assumptions in this idea, and how could they be challenged? |

| Provocation | Trajectory Design: Creating a deliberately absurd or provocative prompt to force the AI to generate unexpected connections. |

| Random Entry | Sequencing: (1) Give me a random noun. (2) Now, generate 5 ideas connecting that noun to my problem of [X]. |

| Analogies | Trajectory Design: Using a Persona or specific instruction like Explain my problem using an analogy from biology. |

Ethical Thinking (ET) to Aiming Thinking (AT)

| Ethical Thinking Process | Mapped to Aiming Thinking Pillar/Pattern |

| Framing the Dilemma | Targeting: Using Core Context to lay out the full ethical scenario with all its constraints and stakeholders. |

| Applying Ethical Theories | Trajectory Design: The Perspective Shift Pattern is used to explicitly ask the AI to analyze the dilemma through different ethical lenses (Deontology, Utilitarianism, etc.). |

| Considering Stakeholders | Trajectory Design: The Perspective Shift Pattern is also used to explore the impact on every stakeholder involved. |

| Evaluating Outcomes | Calibration: Critically assessing the AI’s analysis, questioning its moral reasoning, and refining the conclusions. |

5.2. Application Scenarios: Augmenting Frameworks with Aiming Thinking

Scenario 1: Computational Thinking

- Approach without AI (Traditional CT): The developer would start by manually decomposing the problem: (1) find a suitable weather API, (2) read its documentation, (3) write code to handle the HTTP request, (4) write code to parse the JSON response, (5) write code to structure the data, and (6) write code to save it to CSV. This process involves significant time spent on searching for information, understanding external library specifics (like requests and csv), and debugging syntax and logic errors step-by-step. The entire process is linear and relies solely on the developer’s existing knowledge and research skills.

-

Approach with Aiming Thinking (Augmented CT): The developer acts as an architect, guiding the AI to build the script.

- Targeting: The developer starts with a clear goal. I need a Python script that takes a city name as input, fetches the current temperature and humidity from the OpenWeatherMap API, and appends a timestamped record to a CSV file named weather_log.csv.

-

Sequencing (Primary Relevance): The developer uses the Step-by-Step Construction pattern.

- Prompt 1: First, write the function to fetch the data from the API. Include error handling for network issues or an invalid API key.

- Prompt 2: Great. Now, write the function that takes the JSON response from the first function and extracts the temperature and humidity.

- Prompt 3: Perfect. Finally, write the main part of the script that calls these functions and appends the data to the CSV file.

-

Calibration (Primary Relevance): The AI’s first version of the CSV writing code might be inefficient. The developer uses the Self-Critique pattern.

- Prompt: Critique the file-handling logic in this script. Is there a more robust way to handle writing to the CSV file to prevent issues if the script is run multiple times? (The AI might suggest using Python’s with open(...) statement for better resource management).

-

Trajectory Design (Secondary Relevance): In the initial prompt, the developer uses the Structured Format pattern by asking for comments in the code.

- Prompt: Please add comments to the code explaining each major step. This makes the AI-generated code easier to understand and maintain, demonstrating a secondary but highly valuable application of a Trajectory pattern to improve the final artifact’s quality.

Scenario 2: Design Thinking

- Approach without AI (Traditional DT): The team would schedule a multi-hour workshop. They would use a whiteboard and sticky notes for the Ideate phase, generating a large number of ideas. This would be followed by a lengthy process of affinity mapping (grouping ideas), dot-voting, and discussion to converge on a few promising concepts. Prototyping these ideas would be a separate, subsequent step requiring design and engineering resources.

-

Approach with Aiming Thinking (Augmented DT): The product manager uses the AI to facilitate a rapid, iterative design cycle.

- Targeting: We are designing a mobile app to help busy families reduce food waste. Our target users are tech-savvy but time-poor parents. The app’s tone should be encouraging and non-judgmental. (Uses Audience Persona and Core Context).

-

Sequencing (Primary Relevance): The manager uses the Funneling Pattern to replicate the entire workshop in minutes.

- Prompt 1 (Diverge): Generate 30 distinct feature ideas for this app.

- Prompt 2 (Converge): Excellent list. Now, group these ideas into logical categories (e.g., ‘Inventory Management,’ ‘Recipe Suggestions,’ ‘Shopping Lists’).

- Prompt 3 (Refine): From the ‘Inventory Management’ category, select the top 3 ideas and write a short user story for each.

-

Trajectory Design (Primary Relevance): To deepen the empathy, the manager uses the Perspective Shift Pattern.

- Prompt: For the feature ‘AI-powered expiry date tracking,’ describe its value from the perspective of a parent. Then, describe a potential frustration they might have with it.

-

Calibration (Secondary Relevance): After the AI describes the features, the manager uses the Tone Refinement pattern to align the text with the app’s brand voice.

- Prompt: Take the description of the top 3 features and rewrite them to be more exciting and motivational. This secondary refinement ensures the prototype text is not just functional, but its feel, which is central to the Design Thinking ethos.

Scenario 3: Critical Thinking

- Approach without AI (Traditional CTr): The student would read the article and begin a manual, time-consuming research process. They would search for the credentials of the author and the publication, look for corroborating reports from other reputable news sources, and attempt to find the original scientific paper the article is based on, which may be behind a paywall or difficult to interpret.

-

Approach with Aiming Thinking (Augmented CTr): The student uses the AI as a research assistant and a critical sparring partner.

- Targeting: I am evaluating a news article titled ‘[Article Title]’ from ‘[Publication]’. My goal is to assess its scientific credibility and identify potential biases.

-

Calibration (Primary Relevance): The core of the task relies on the Fact-Checking Pattern.

- Prompt 1: The article claims a study found ‘X’. Can you find the original scientific paper this claim is based on? Please provide the title, authors, and journal.

- Prompt 2: The author of the article is [Author’s Name]. What are their credentials? Are they a science journalist or an opinion writer?

- Prompt 3: Does the original paper’s conclusion fully support the strong claims made in the news article’s headline?

-

Calibration (Primary Relevance): The student then uses the Self-Critique pattern to uncover potential flaws.

- Prompt: Read the following excerpt from the article. Identify three ways the language used might be sensationalized or misleading for a lay audience.

-

Trajectory Design (Secondary Relevance): To ensure a balanced view, the student employs the Perspective Shift pattern.

- Prompt: Search for critiques or alternative interpretations of this scientific study. Summarize any counter-arguments from other scientists in the field. This secondary pattern usefully extends the critical inquiry from merely verifying the source to understanding its place in the broader scientific conversation.

Scenario 4: Strategic Thinking

- Approach without AI (Traditional STr): The founder would spend days or weeks conducting manual market research, analyzing competitors’ websites, trying to estimate market size from public reports, and brainstorming strategic options alone or with a small team. The process is often limited in scope due to the sheer effort required to gather and synthesize the information.

-

Approach with Aiming Thinking (Augmented STr): The founder uses the AI as a virtual strategy consultant to broaden their analysis and accelerate planning.

- Targeting: We are a B2B SaaS startup launching a new project management tool for remote teams. Our key differentiator is its AI-powered task prioritization feature. Our budget is limited. The goal is a go-to-market strategy for the first 6 months. (Core Context & Success Definition).

-

Trajectory Design (Primary Relevance): The founder uses the Persona and Perspective Shift patterns to model the competitive landscape.

- Prompt 1: Act as a market analyst from Gartner. Provide a SWOT analysis of our startup based on the context I provided.

- Prompt 2: Now, act as the VP of Marketing for our main competitor, Asana. What would be your counter-strategy to our launch?

-

Sequencing (Primary Relevance): The founder uses the Topic Expansion pattern to build the strategy.

- Prompt 1: List the top 5 most effective marketing channels for a B2B SaaS startup with a limited budget.

- Prompt 2: For the top channel you listed, ‘Content Marketing,’ propose a 3-month content strategy.

-

Calibration (Secondary Relevance): After generating a draft strategy, the founder uses the Self-Critique pattern for risk assessment.

- Prompt: What is the single biggest assumption this go-to-market strategy is based on? What is the greatest risk to its success? This secondary use of a Calibration pattern forces a stress test of the strategy, a key component of robust strategic thinking.

Scenario 5: Creative Thinking

- Approach without AI (Traditional CrT): The team would gather in a room for a brainstorming session, a process that relies heavily on the group’s energy and chemistry. They would use divergent thinking to generate ideas on a whiteboard. This process can be slow and is often dominated by the loudest voices or constrained by the group’s shared biases. The convergent phase of selecting and refining the best idea would involve lengthy debates and subjective decision-making.

-

Approach with Aiming Thinking (Augmented CrT): The lead writer uses AT to facilitate a supercharged creative process.

- Targeting: We need a concept for a new science fiction TV series. It should be high-concept, suitable for a streaming platform, and appeal to fans of ‘Black Mirror’ and ‘The Expanse’. Crucially, do not use concepts involving time travel or alien invasions. (Uses Audience Persona and Negative Constraint).

-

Sequencing (Primary Relevance): The writer uses the Funneling Pattern to manage the creative cycle.

- Prompt 1 (Diverge): Generate 20 unique loglines (one-sentence summaries) for a sci-fi series that fit the criteria.

- Prompt 2 (Converge): Select the top 3 loglines that have the most potential for long-term character development.

-

Sequencing (Primary Relevance): For the winning concept, the writer uses the Topic Expansion pattern to flesh it out.

- Prompt 3: For the logline ‘[Winning Logline]’, create a brief synopsis of the first season.

- Prompt 4: Now, provide character descriptions for the three main protagonists.

-

Trajectory Design (Secondary Relevance): To break a potential creative block, the writer uses the Recipe Pattern in a provocative way.

- Prompt: Let’s make this more unique. Take the current series concept and incorporate the theme of ‘ancient beekeeping’. How could that work? This secondary pattern injects an unexpected element, pushing the concept into a more original space.

Scenario 6: Analytical Thinking

- Approach without AI (Traditional ATy): The analyst would manually read through hundreds or thousands of comments in a spreadsheet. They would create new columns to categorize each comment by theme (e.g., ‘Pricing’, ‘Bugs’, ‘Customer Service’), a subjective and extremely time-consuming process. Finally, they would use pivot tables or other tools to count the occurrences in each category to identify the most frequent complaints.

-

Approach with Aiming Thinking (Augmented ATy): The analyst uses the AI to perform the heavy lifting of categorization and summarization.

- Targeting: I have a dataset of 500 customer feedback comments. My goal is to identify and quantify the top 3 most common complaint categories.

-

Trajectory Design (Primary Relevance): The analyst uses the Structured Format pattern to ensure the output is usable.

- Prompt: (After pasting a sample of the data) Analyze the following customer comments. Your task is to categorize each comment into one of the following categories: ‘Pricing’, ‘Software Bugs’, ‘Feature Request’, or ‘Customer Support’. Provide the output as a two-column Markdown table with the original comment and its category.

-

Calibration (Primary Relevance): After getting the categorized data, the analyst uses the Reformatting Pattern to synthesize the results.

- Prompt: Based on the categorization you just performed, count the number of comments in each category and present the result as a summary.

-

Trajectory Design (Secondary Relevance): To gain deeper insight, the analyst employs the Master Example pattern.

- Prompt: For the ‘Software Bugs’ category, find the comment that is the best example of a clear and actionable bug report. This secondary pattern usefully moves beyond pure quantitative analysis to qualitative insight, helping the analyst find the most representative customer voice.

Scenario 7: Systems Thinking

- Approach without AI (Traditional ST): The manager would convene meetings with various departments (transport, public health, police) to manually map out potential effects on a whiteboard. They would draw diagrams with stocks (e.g., ‘Number of Cyclists’) and flows, trying to anticipate feedback loops. The process is static and relies on the collective imagination and experience of the people in the room.

-

Approach with Aiming Thinking (Augmented ST): The manager uses the AI as a dynamic simulation partner to explore the system’s interconnections.

- Targeting: I want to analyze the systemic effects of introducing a city-wide bike-sharing program. The city has a population of 500,000 and moderate existing public transport.

-

Trajectory Design (Primary Relevance): The manager uses the Perspective Shift Pattern to identify system components.

- Prompt: List the potential positive and negative impacts of this program from the perspective of: a daily car commuter, a local shop owner, a public health official, and a tourist.

-

Sequencing (Primary Relevance): The manager uses a form of Topic Expansion to trace causal chains and loops.

- Prompt 1: Let’s focus on a positive impact: ‘Improved public health.’ What are the likely second-order effects of this? (e.g., lower healthcare costs).

- Prompt 2: Now a negative impact: ‘Bikes left improperly parked.’ What is a potential reinforcing feedback loop that could make this problem spiral? (e.g., clutter annoys residents -> residents complain -> negative press -> lower political will for funding -> program maintenance declines -> more broken/mis-parked bikes).

-

Calibration (Secondary Relevance): The manager uses Self-Critique to challenge the model.

- Prompt: The system you’ve described seems plausible. What is the weakest or most uncertain link in this causal chain? Which variable would have the biggest impact if our assumptions about it are wrong? This secondary pattern usefully stress-tests the system map.

Scenario 8: Lateral Thinking

- Approach without AI (Traditional LT): A creative director would lead a session using de Bono’s techniques. They might physically pick a random object from the room or a word from a dictionary (Random Entry) and spend an hour trying to force connections. Or they might posit a Provocation (What if toothpaste was black?) and see where the discussion leads. The process can be powerful but is highly dependent on the team’s ability to break out of its own cognitive ruts.

-

Approach with Aiming Thinking (Augmented LT): The creative director uses the AI as an inexhaustible source of randomness and provocation.

-

Trajectory Design (Primary Relevance): The director directly implements the Persona pattern with a lateral twist.

- Prompt 1 (Provocation): Act as a creative director who believes toothpaste is boring. Your mission is to make it exciting. Propose a campaign based on the provocative idea that our toothpaste doesn’t clean teeth, it gives them temporary superpowers.

-

Sequencing (Primary Relevance): The director then uses the Random Entry technique via a sequence of prompts.

- Prompt 2: Give me a completely random, unrelated occupation. -> AI: Deep-sea welder.

- Prompt 3: Now, generate three campaign ideas for our toothpaste that are inspired by a ‘deep-sea welder’.

-

Targeting (Secondary Relevance): The director uses a Negative Constraint to force the AI away from clichés.

- Prompt: Generate more ideas, but do not mention ‘shiny smiles,’ ‘fresh breath,’ or ‘fighting cavities’. This secondary pattern is crucial for lateral thinking as it closes off the obvious, well-trodden neural pathways.

-

Scenario 9: Ethical Thinking

- Approach without AI (Traditional ET): The team would research existing laws and best practices. They would hold meetings to discuss potential issues like bias, privacy, and fairness. The process would be guided by the team’s own ethical frameworks and experiences, which might be limited or contain blind spots.

-

Approach with Aiming Thinking (Augmented ET): The policy lead uses the AI to structure a comprehensive and multi-perspective ethical deliberation.

-

Targeting (Primary Relevance): The lead starts by framing the entire dilemma with the Core Context pattern.

- Prompt: Context: We are developing a policy for using an AI tool to screen resumes and conduct initial video interviews for engineering roles. The company values fairness, diversity, and efficiency. The goal is to draft a policy that maximizes benefits while minimizing ethical risks.

-

Trajectory Design (Primary Relevance): The lead then uses the Perspective Shift pattern as the core of the analysis.

- Prompt 1: Analyze the ethical implications of this AI tool through three different ethical lenses: Deontology (duties and rules), Utilitarianism (greatest good), and Virtue Ethics (character and excellence).

- Prompt 2: Now, identify the key ethical concerns from the perspective of: a job applicant, a hiring manager, and a company lawyer.

-

Calibration (Secondary Relevance): To ensure the policy is practical, the lead uses the Self-Critique pattern.

- Prompt: Based on your analysis, draft a 5-point policy. Then, for each point, identify a potential loophole or challenge in its real-world implementation. This secondary pattern moves the ethical discussion from pure theory to practical application, a key step in effective policy-making.

-

6. Discussion and Implications

6.1. Implications for Education

6.2. Implications for Professional Development

6.3. Implications for AI System Design

6.4. Limitations and Human Agency

7. Conclusion and Future Work

References

- Anderson, L. W., & Krathwohl, D. R. (Eds.). (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of educational objectives. Longman.

- Arnold, R. D., & Wade, J. P. (2015). A definition of systems thinking: A systems approach. Procedia Computer Science, 44, 669-678. [CrossRef]

- Brown, T. (2008). Design thinking. Harvard Business Review, 86(6), 84–92.

- Brown, T. B., Mann, B., Ryder, N., Subbiah, M., Kaplan, J., Dhariwal, P., … & Amodei, D. (2020). Language models are few-shot learners. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 33, 1877-1901.

- Brynjolfsson, E., & McAfee, A. (2023). The Turing trap: The promise & peril of human-like artificial intelligence. Daedalus, 152(2), 5-21.

- de Bono, E. (1970). Lateral thinking: Creativity step by step. Harper & Row.

- Flavell, J. H. (1979). Metacognition and cognitive monitoring: A new area of cognitive–developmental inquiry. American Psychologist, 34(10), 906–911. [CrossRef]

- Ji, Z., Lee, N., Frieske, R., Yu, T., Su, D., Xu, Y., … & Fung, P. (2023). Survey of hallucination in natural language generation. ACM Computing Surveys, 55(12), 1-38. [CrossRef]

- Liedtka, J. M. (1998). Strategic thinking: Can it be taught? Long Range Planning, 31(1), 120-129. [CrossRef]

- Liem, G. A. D., & Fegor, M. J. (2023). 21st century skills: The role of cognitive and motivational processes. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education. Oxford University Press. [CrossRef]

- Meadows, D. H. (2008). Thinking in systems: A primer. Chelsea Green Publishing.

- Micheli, P., Wilner, S. J., Bhatti, S. H., Mura, M., & Beverland, M. B. (2019). Doing design thinking: Conceptual review, synthesis, and research agenda. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 36(2), 124-148. [CrossRef]

- OECD (2022). PISA 2021 Creative Thinking Framework (Third Draft). Retrieved from https://www.oecd.org/pisa/publications/PISA-2021-creative-thinking-framework.pdf.

- Paul, R., & Elder, L. (2019). The miniature guide to critical thinking concepts and tools (8th ed.). Rowman & Littlefield.

- Perkins, D. N., & Salomon, G. (1992). Transfer of learning. In International Encyclopedia of Education (2nd ed.). Pergamon Press.

- Sawyer, R. K. (2022). The science of learning: A handbook for teachers. Cambridge University Press.

- Schunk, D. H. (2012). Learning theories: An educational perspective (6th ed.). Pearson.

- Tai, J., Ajjawi, R., Boud, D., Dawson, P., & Panadero, E. (2018). Developing evaluative judgement: enabling students to make decisions about the quality of work. Higher Education, 76(3), 467–481. [CrossRef]

- Tang, X., Yin, Y., Lin, Q., Hadad, R., & Zhai, X. (2023). A systematic review of AI-powered technology for computational thinking education. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 4, 100131. [CrossRef]

- Vallor, S. (2016). Technology and the virtues: A philosophical guide to a future worth wanting. Oxford University Press.

- Wei, J., Wang, X., Schuurmans, D., Bosma, M., Chi, E., Le, Q., & Zhou, D. (2022). Chain-of-thought prompting elicits reasoning in large language models. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 35, 24824-24837.

- White, J., Fu, Q., Hays, S., Sandborn, M., Olea, C., Gilbert, H., … & Schmidt, D. C. (2023). A prompt-based software engineering. In 2023 IEEE/ACM 1st International Workshop on Prompt-Based Software Engineering (PromptBE) (pp. 19-26). IEEE.

- Wing, J. M. (2006). Computational thinking. Communications of the ACM, 49(3), 33–35. [CrossRef]

- World Economic Forum. (2023, April). The Future of Jobs Report 2023. Retrieved from https://www.weforum.org/reports/the-future-of-jobs-report-2023/.

- Zimmerman, B. J., & Schunk, D. H. (Eds.). (2011). Handbook of self-regulation of learning and performance. Routledge.

- Zohar, A., & Dori, Y. J. (Eds.). (2012). Metacognition in science education: Trends in current research. Springer.

- Zamfirescu-Pereira, J., Wong, R. Y., Hartmann, B., & Yang, Q. (2023). Why and how to ground instructional prompting for co-creation with large language models. In Proceedings of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1-21). [CrossRef]

| AT Pattern | CT | DT | CTr | ST | STr | CrT | ATy | LT | ET |

| Targeting | |||||||||

| Success Definition | ● | ● | ○ | ○ | ● | ○ | ● | ○ | ○ |

| Scope Fencing | ● | ○ | ● | ● | ● | ○ | ● | ○ | ● |

| Core Context | ○ | ● | ● | ● | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● |

| Audience Persona | ○ | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Negative Constraint | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● | ○ | ● | ○ |

| Trajectory Design | |||||||||

| Persona Pattern | ○ | ● | ○ | ○ | ● | ● | ○ | ● | ● |

| Master Example | ● | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● | ● | ○ | ○ |

| Structured Format | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● | ○ | ○ |

| Recipe Pattern | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● | ● | ● | ○ | ○ |

| Perspective Shift | ○ | ● | ● | ● | ● | ○ | ○ | ● | ● |

| Sequencing | |||||||||

| Step-by-Step | ● | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● | ● | ○ | ○ |

| Topic Expansion | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ○ | ● | ○ | ○ |

| Chain-of-Thought | ● | ○ | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● | ○ | ○ |

| Funneling Pattern | ○ | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Template Builder | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Calibration | |||||||||

| Tone Refinement | ○ | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Reformatting | ● | ○ | ○ | ● | ○ | ○ | ● | ○ | ○ |

| Merge & Synthesize | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● | ● | ● | ○ | ○ |

| Self-Critique | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ○ | ● | ● | ● |

| Fact-Checking | ○ | ○ | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● | ○ | ● |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).