Submitted:

18 July 2025

Posted:

21 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Background

3. Study Motivation

4. Study Approach

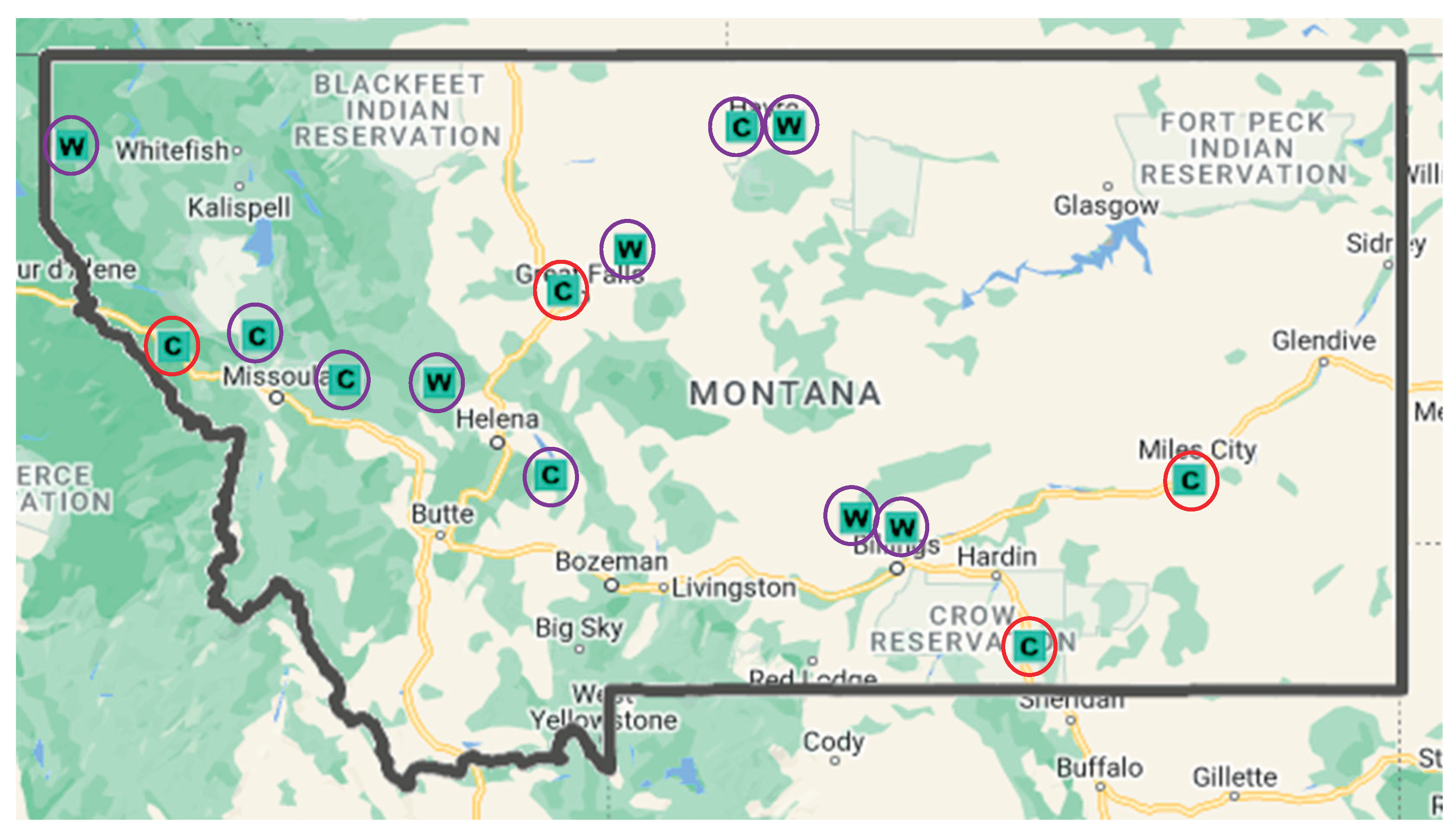

5. Data Collection

6. Analysis and Results

6.1. Method I (Base Condition - Total Traffic)

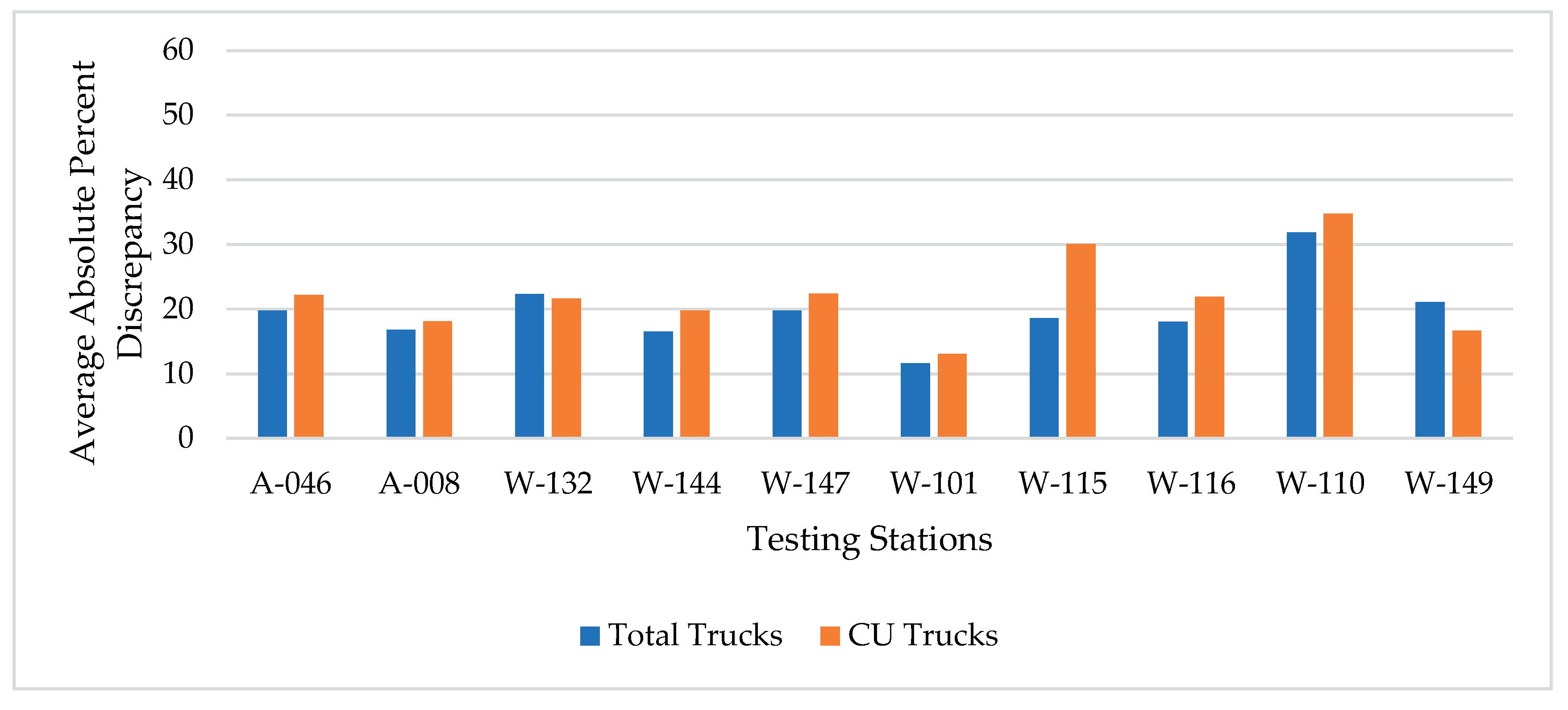

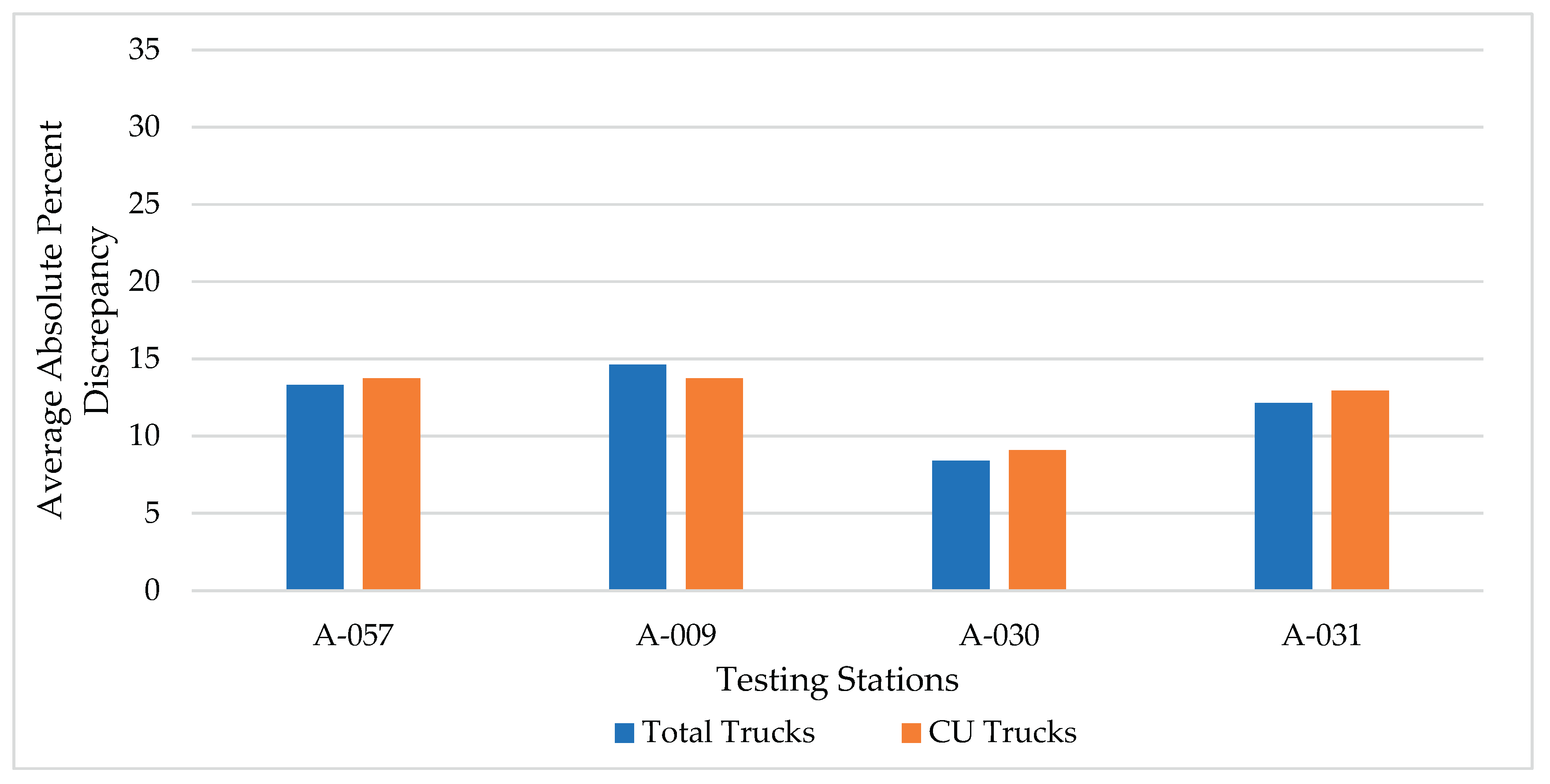

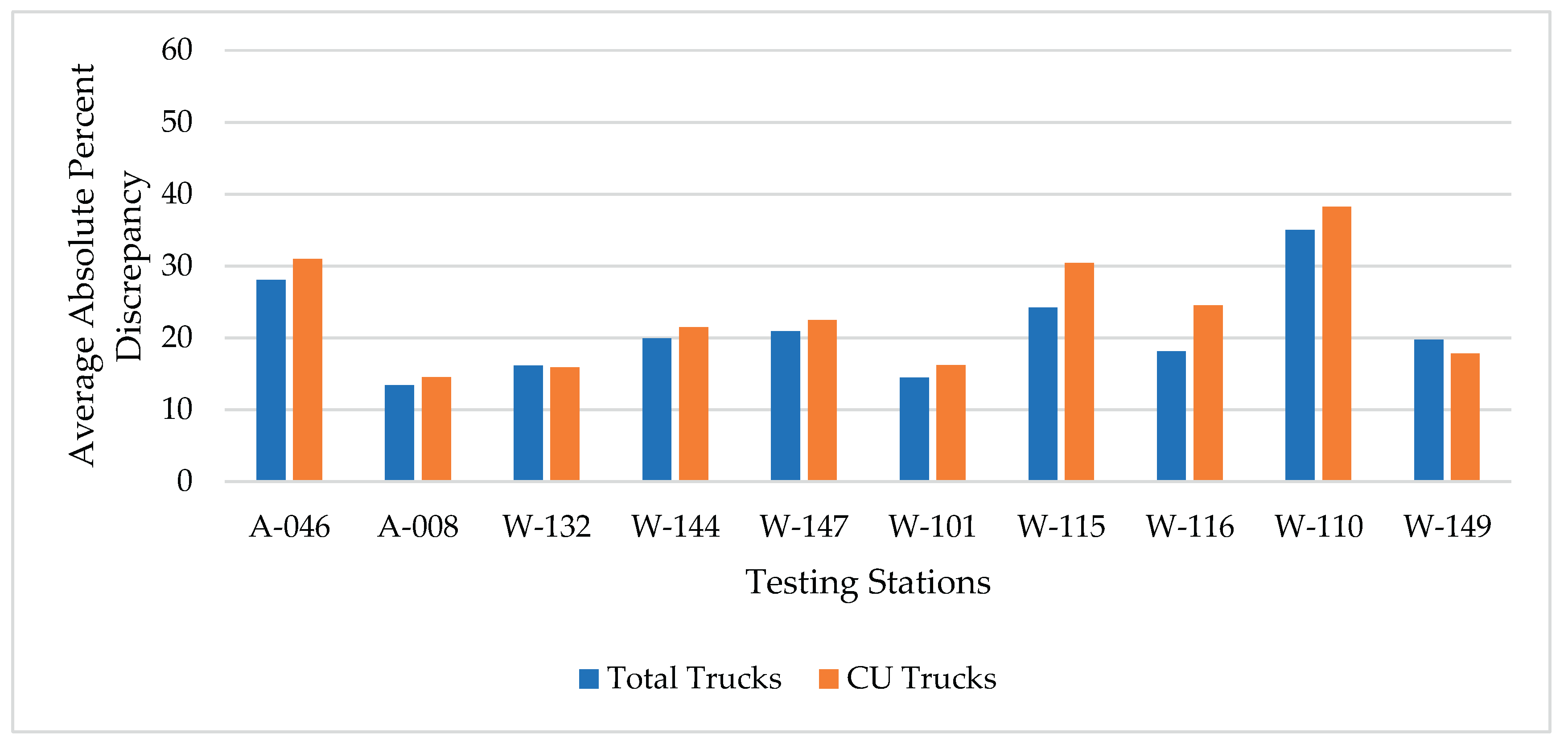

6.2. Method II (Using Total Trucks, Class 5-13)

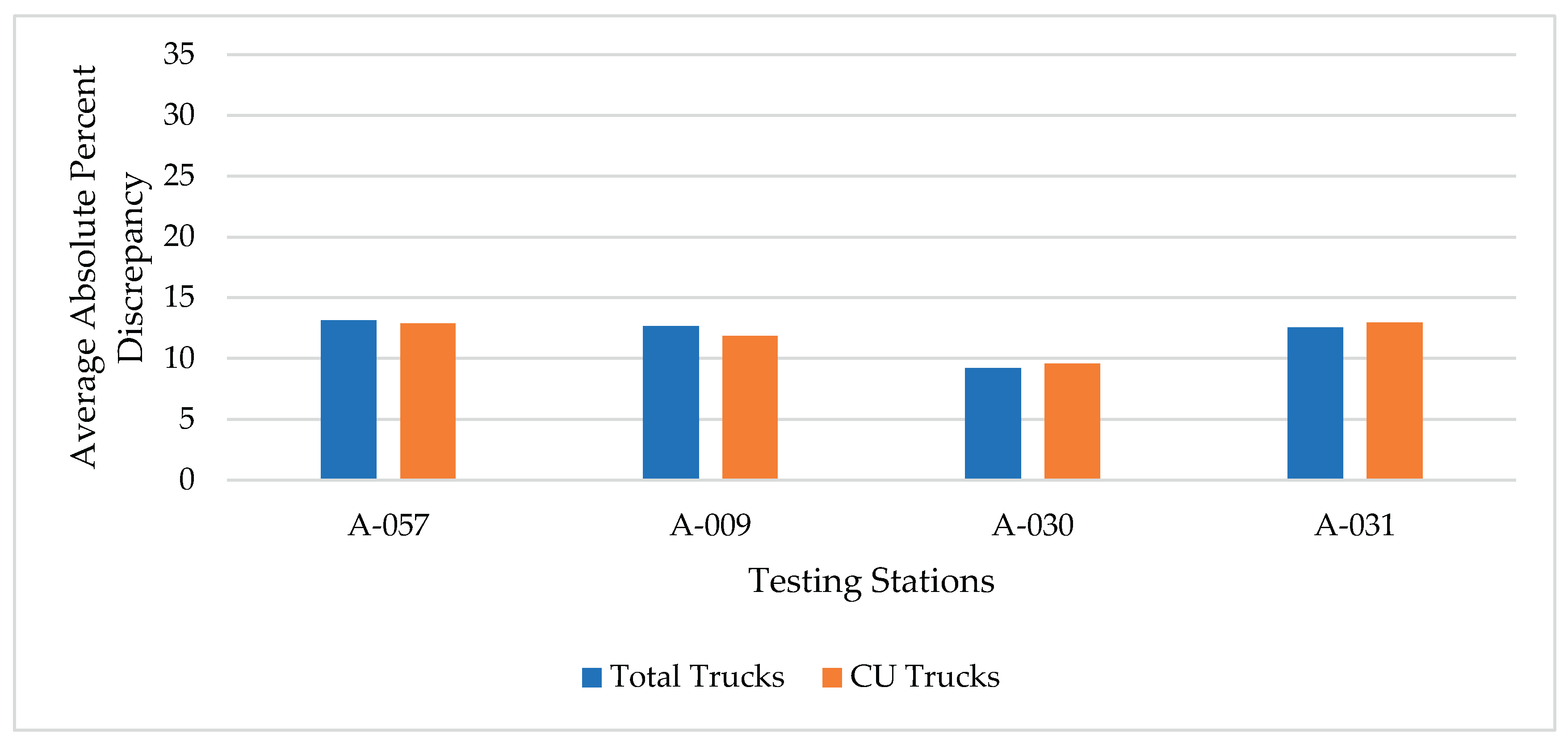

6.3. Method III (Using CU Trucks, Class 8-13)

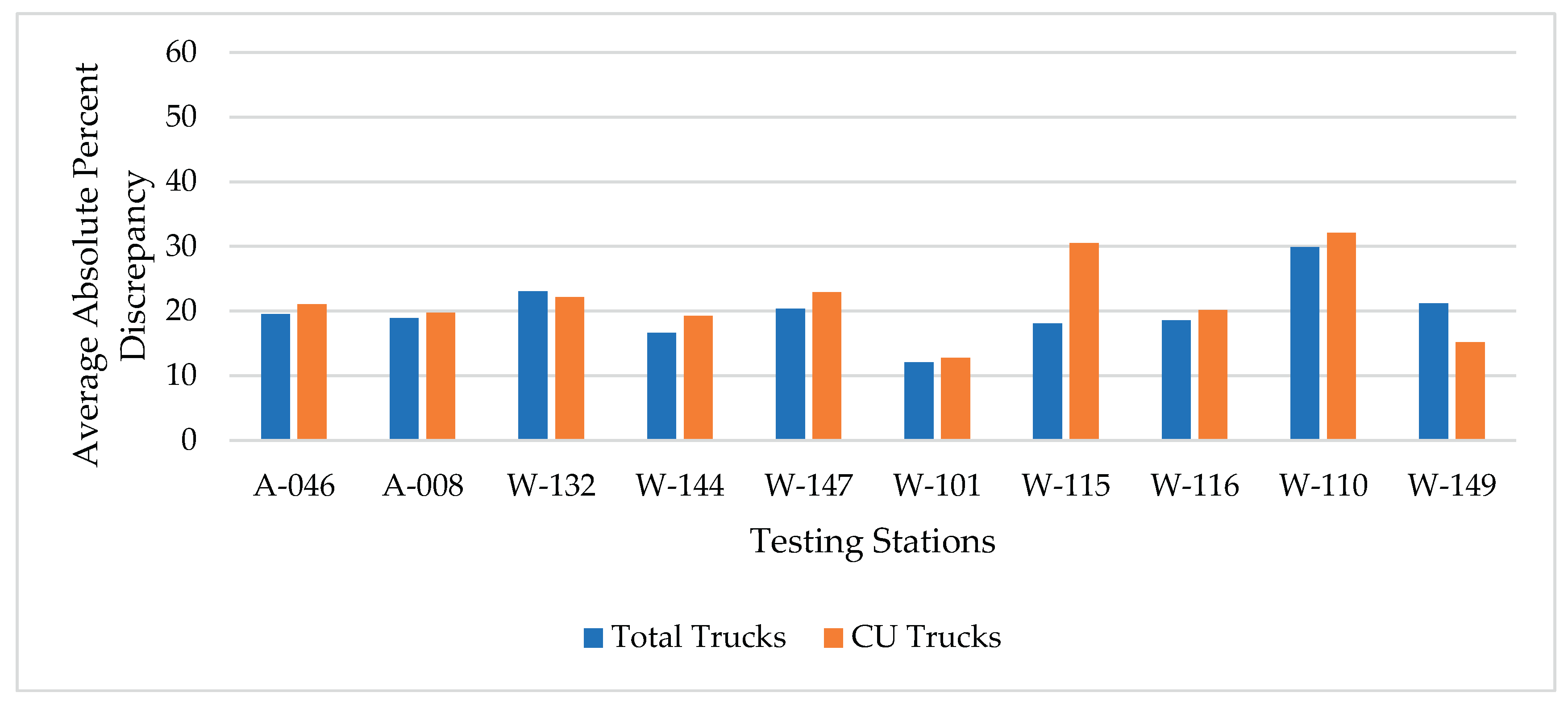

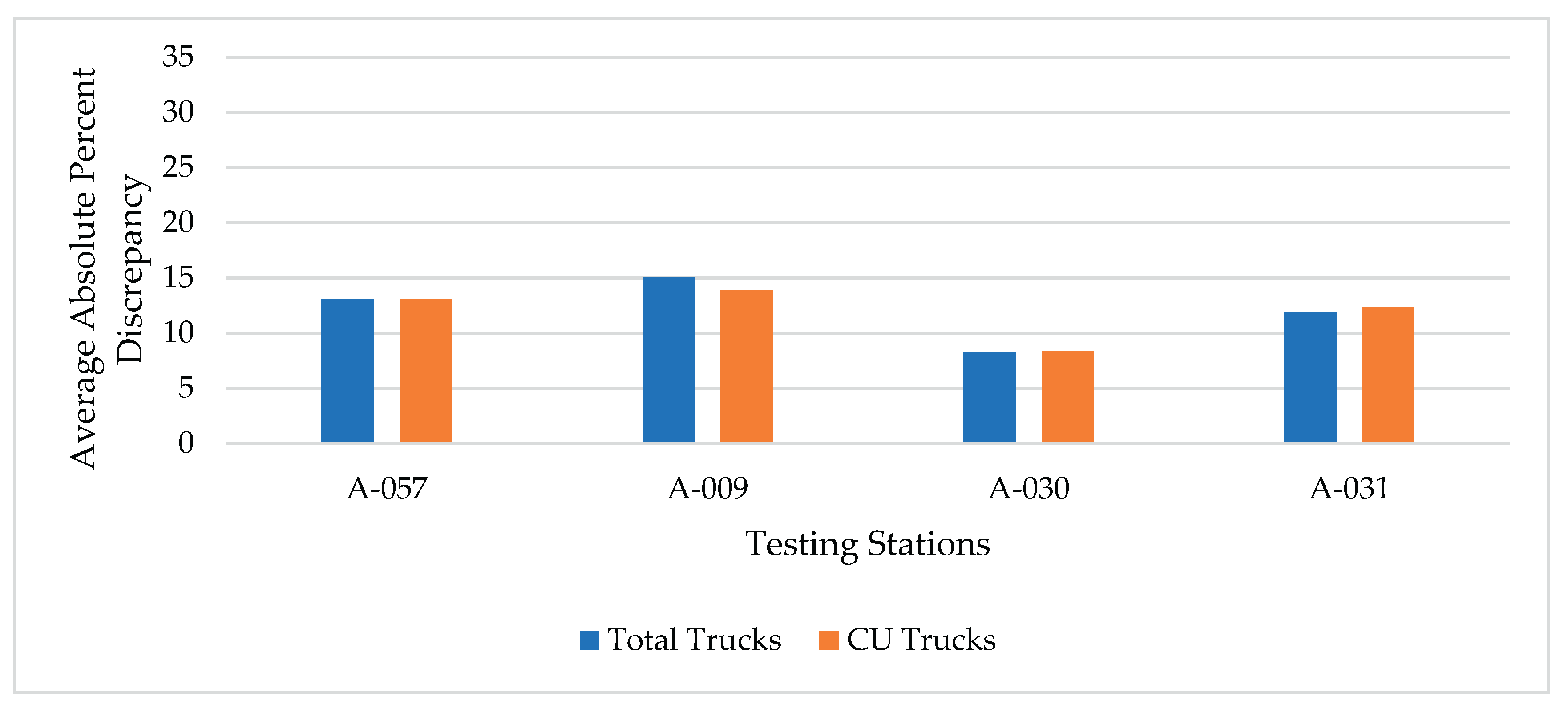

6.4. Method IV (Using Separate Vehicle Classes)

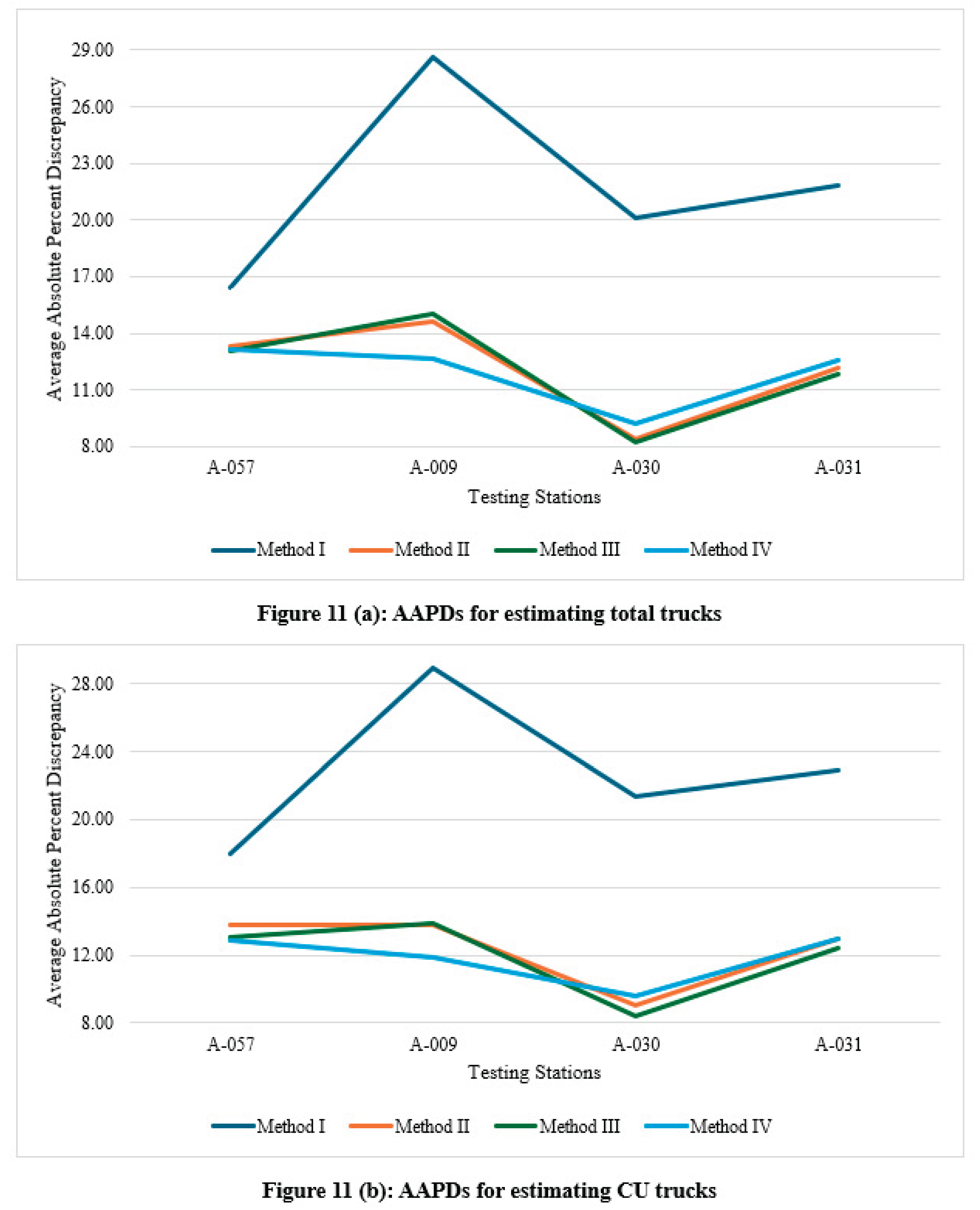

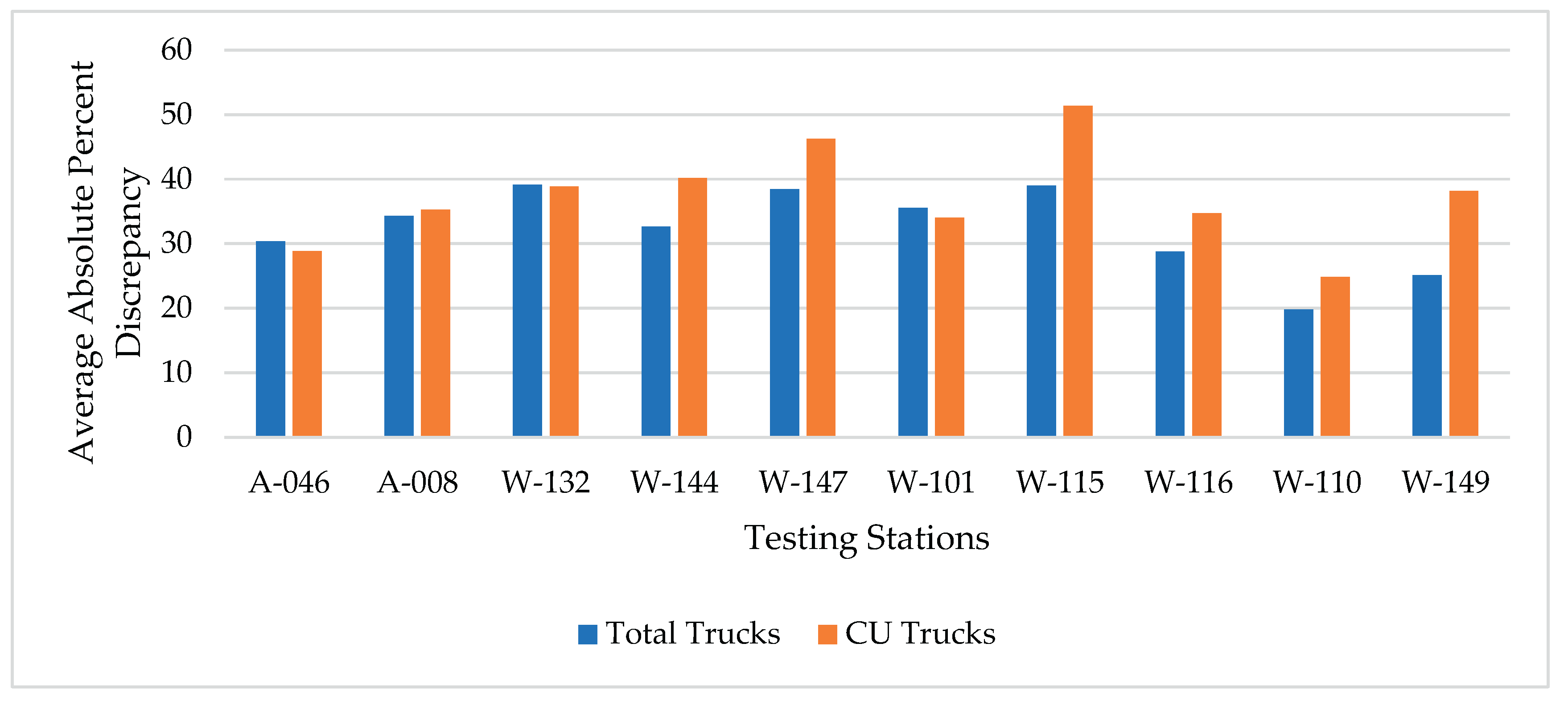

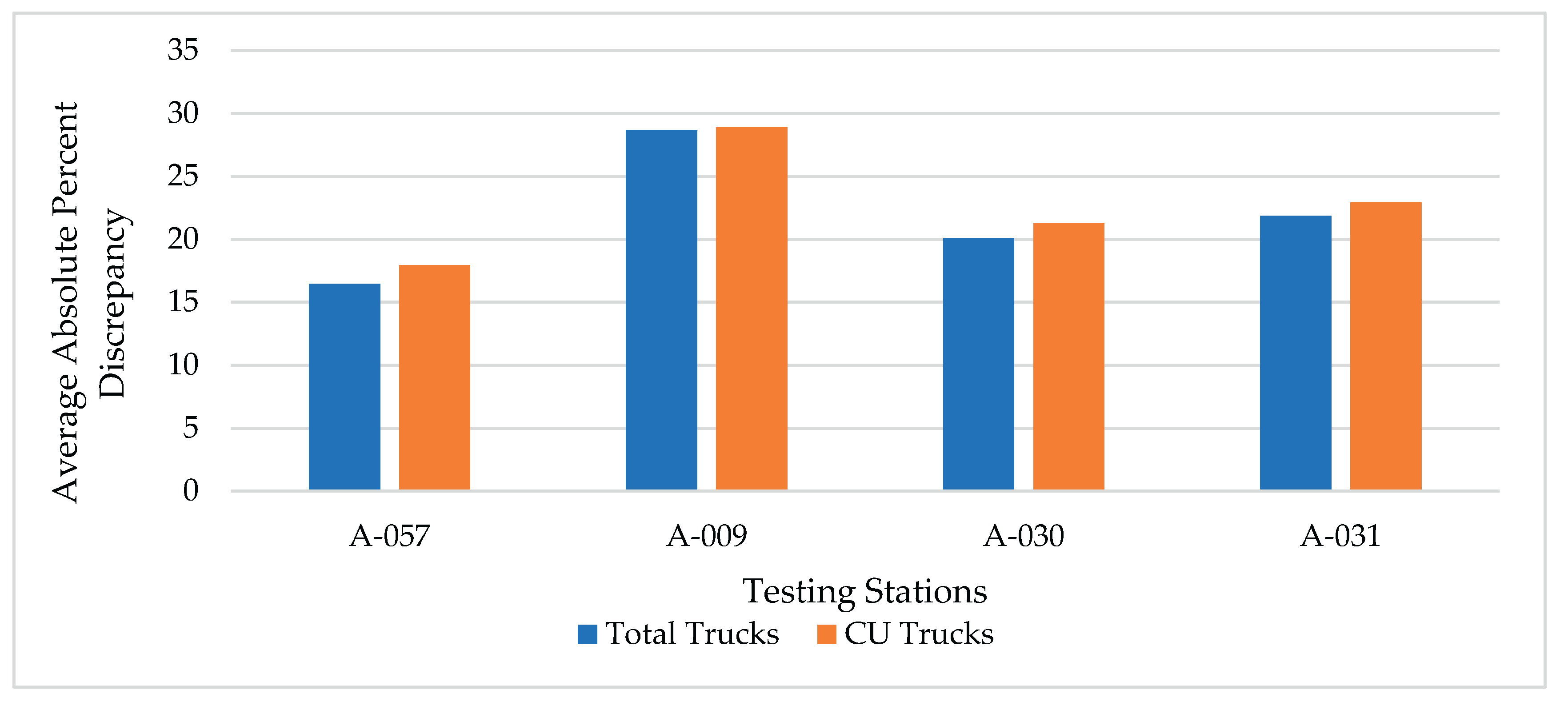

7. Comparison of Different Methods

8. Summary and Conclusions

- i.

- Study results show that method I (traditional approach using total traffic adjustment factors) performed poorly in comparison with the other three methods consistently showing higher discrepancies. This finding is consistent with the fact that the factors affecting the temporal variations in total traffic may not be relevant to the variation in heavy vehicle traffic over time. The discrepancy in heavy vehicle traffic estimation is more profound for RPA-O classification compared to the RPA-I classification. This is somewhat expected given that much of the truck traffic on interstate highways is long-haul through traffic associated with more consistent daily and seasonal variation patterns.

- ii.

- Method II (total truck adjustment factors) and Method III (CU truck adjustment factors) estimated the heavy vehicle traffic with lower discrepancy, and the mean discrepancies at testing stations for both methods were very close. The similar performance of the two methods can be attributed to the fact that trucks in classes 5-7 only constitute a small proportion of trucks at most stations.

- iii.

- Method IV (no aggregation – class-specific adjustment factors) exhibited good performance overall compared to the other methods. However, this method did not exhibit better performance compared to method II or method III. Specifically, the method lagged behind methods II and III for the RPA-O classification (ten testing stations) while it was slightly better than methods II and III for the RPA-I classification (four testing stations). These results suggest that the class-specific adjustment factors (method IV), while more data-intensive and complicated, don’t necessarily yield more accurate estimates for total or CU truck traffic. This finding may be related to the small number of trucks (small sample size) in certain classes which may affect the accuracy of the MDOW factors for those classes.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MDOW | Monthly Day of the Week |

| MDT | Montana Department of Transportation |

| FHWA | Federal Highway Administration |

| ATR | Automatic Traffic Recorder |

| AAPD | Average Absolute Percent Discrepancy |

References

- Shen G, Zhou L, Aydin SG. A multi-level spatial-temporal model for freight movement: The case of manufactured goods flows on the U.S. highway networks. Journal of Transport Geography. 2020; 88:102868. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0966692320309455.

- Bureau of Transportation Statistics. U.S. Ton-Miles of Freight. Available from: https://www.bts.gov/content/us-ton-miles-freight.

- Federal Highway Administration. MAP-21 - Moving Ahead for Progress in the 21st Century. Available from: https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/map21/factsheets/freight.cfm.

- Cohen H, Horowitz A, Pendyala R. National Cooperative Highway Research Program (NCHRP) Report 606: Forecasting Statewide Freight Toolkit. Washington, D.C.; Available from: www.TRB.org.

- Federal Highway Administration (FHWA). Traffic Monitoring Guide. 2022. Available from: https://rosap.ntl.bts.gov/view/dot/74643.

- Stephens J, Al-Kaisy AF, Villwock-Witte N, McCarthy D, Qi Y, Veneziano DA, et al. Montana Weigh-in-Motion (WIM) and Automatic Traffic Recorder (ATR) Strategy. 2017. Available from: https://rosap.ntl.bts.gov/view/dot/32517/dot_32517_DS1.pdf.

- Tsapakis I, Schneider IV WH, Nichols AP. A Bayesian analysis of the effect of estimating annual average daily traffic for heavy-duty trucks using training and validation datasets. Transportation Planning and Technology. 2013 Mar 1;36(2):201–17. Available from: . [CrossRef]

- Spasovic L, Ozbay K, Mittal N, Golias M. Estimation of Truck Volumes and Flows. In 2004. Available from: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:106467251.

- Yuanchang X, Nathan H. Kernel-Based Machine Learning Models for Predicting Daily Truck Volume at Seaport Terminals. Journal of Transportation Engineering. 2010 Dec 1;136(12):1145–52. Available from: . [CrossRef]

- Gu Y, Liu D, Stanford J, Han LD. Innovative Method for Estimating Large Truck Volume Using Aggregate Volume and Occupancy Data Incorporating Empirical Knowledge into Linear Programming. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board. 2022 Jun 9;2676(11):648–63. Available from: . [CrossRef]

- Hou Y, Young SE, Sadabadi K, SekuBa P, Markow D. Estimating Highway Volumes Using Vehicle Probe Data - Proof of Concept: Preprint. In: ITS World Congress. Montreal; 2017. Available from: https://www.osti.gov/biblio/1426856.

- Schewel L, Co S, Willoughby C, Yan L, Clarke N, Wergin J. Non-Traditional Methods to Obtain Annual Average Daily Traffic (AADT). 2021. Available from: https://rosap.ntl.bts.gov/view/dot/64897/dot_64897_DS1.pdf.

- Zhang X, Chen M. Enhancing Statewide Annual Average Daily Traffic Estimation with Ubiquitous Probe Vehicle Data. Transportation Research Record. 2020 Jun 21;2674(9):649–60. Available from: . [CrossRef]

- Grande G, Lesniak M, Tardif LP, Regehr JD. Exploring vehicle probe data as a resource to enhance network-wide traffic volume estimates. Canadian Journal of Civil Engineering. 2021 Jun 23;49(4):558–68. Available from: . [CrossRef]

- Zhang X, Chen M. Statewide Truck Volume Estimation Using Probe Vehicle Data and Machine Learning. Transportation Research Record. 2023 Mar 27;2677(8):588–601. Available from: . [CrossRef]

- Zrobek C, Grande G, Regehr J, Mehran B. Evaluating the Accuracy of Probe-Based Truck Volumes using Continuous and Short-Duration Traffic Counts. Transportation Research Record. 2024 Apr 23;03611981241242070. Available from: . [CrossRef]

- Southworth F. Freight Flow Modeling in the United States. Appl Spat Anal Policy. 2018;11(4):669–91. Available from: . [CrossRef]

- Holguín-Veras J, List GF, Meyburg AH, Ozbay K, Teng H, Yahalom SZ. AN ASSESSMENT OF METHODOLOGICAL ALTERNATIVES FOR A REGIONAL FREIGHT MODEL IN THE NYMTC REGION. In 2001. Available from: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:106903687.

- Dynamic Data Fusion Mining Private Sector Relationships and Public Databases to Enhance and Predict Freight Movement BACKGROUND AND CHALLENGE.

- Andreoli D, Goodchild A, Jessup E. Estimating truck trips with product specific data: a disruption case study in Washington potatoes. Transportation Letters. 2012 Jul 1;4(3):153–66. Available from: . [CrossRef]

- Proussaloglou K, Popuri Y, Tempesta D, Kasturirangan K, Cipra D. Wisconsin Passenger and Freight Statewide Model: Case Study in Statewide Model Validation. Transportation Research Record. 2007 Jan 1;2003(1):120–9. Available from: . [CrossRef]

- Souleyrette RR, Hans ZN. Statewide Transportation Planning Model and Methodology Development Program Final Report November 1996 Researchers. In 1996. Available from: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:10125769.

- Shen G, Zhou L, Aydin SG. A multi-level spatial-temporal model for freight movement: The case of manufactured goods flows on the U.S. highway networks. Journal of Transport Geography. 2020; 88:102868. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0966692320309455.

- Vadali SR, Aldrete RM, Bujanda A. Financial Model to Assess Value Capture Potential of a Roadway Project. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board. 2009 Jan 1;2115(1):1–11. Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.3141/2115-01.

| Functional Classes | Year | ||||

| 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | |

| Rural Principal Arterials – Others | 4 | 2 | 2 | 10 | 4 |

| Rural Principal Arterials – Interstate | 1 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 1 |

| Stations | Methods | |||

| Method I (Base) | Method II | Method III | Method IV | |

| Rural Principal Arterials – Others (RPA-O) | ||||

| A-008 | 34.34* [35.31] ** | 16.83 [18.16] | 18.94 [19.78] | 13.44 [14.53] |

| A-046 | 30.40 [28.89] | 19.75 [22.15] | 19.51 [21.08] | 28.10 [30.95] |

| W-132 | 39.19 [38.87] | 22.33 [21.60] | 23.07 [22.17] | 16.13 [15.88] |

| W-144 | 32.66 [40.22] | 16.56 [19.80] | 16.67 [19.28] | 19.94 [21.49] |

| W-147 | 38.51 [46.30] | 19.76 [22.36] | 20.35 [22.93] | 20.91 [22.46] |

| W-101 | 35.55 [34.05] | 11.62 [13.06] | 12.10 [12.76] | 14.45 [16.21] |

| W-110 | 19.82 [24.87] | 31.82 [34.77] | 29.92 [32.09] | 35.00 [38.24] |

| W-115 | 39.04 [51.37] | 18.62 [30.05] | 18.08 [30.50] | 24.24 [30.41] |

| W-116 | 28.78 [34.73] | 18.08 [21.90] | 18.59 [20.18] | 18.11 [24.54] |

| W-149 | 25.13 [38.16] | 21.10 [16.68] | 21.18 [15.18] | 19.75 [17.80] |

| Mean (RPA-O) | 32.34 [37.28] | 19.64 [22.05] | 19.84 [21.60] | 21.01 [23.25] |

| Rural Principal Arterials – Interstate (RPA-I) | ||||

| A-057 | 16.45 [17.94] | 13.32 [13.74] | 13.05 [13.09] | 13.13 [12.89] |

| A-009 | 28.64 [28.90] | 14.64 [13.76] | 15.06 [13.91] | 12.67 [11.85] |

| A-030 | 20.09 [21.31] | 8.41 [9.079] | 8.27 [8.40] | 9.23 [9.59] |

| A-031 | 21.87 [22.94] | 12.15 [12.96] | 11.86 [12.39] | 12.57 [12.96] |

| Mean (RPA-I) | 21.76 [22.77] | 12.13 [12.39] | 12.06 [11.95] | 11.90 [11.82] |

| Stations | Comparison of Methods | |||||

| MethodI vs MethodII | MethodI vs MethodIII | MethodI vs MethodIV | MethodIIvs MethodIII | MethodIIvs MethodIV | MethodIIIvs MethodIV | |

| Rural Principal Arterials – Others (RPA-O) | ||||||

| A-008 | <0.001* <0.001** |

<0.001 <0.001 |

<0.001 0.2956 |

0.0334 0.4452 |

<0.001 <0.001 |

<0.001 <0.001 |

| A-046 | <0.001 <0.001 |

<0.001 <0.001 |

0.2007 <0.001 |

0.853 0.4381 |

<0.001 <0.001 |

<0.001 <0.001 |

| W-132 | <0.001 <0.001 |

<0.001 <0.001 |

<0.001 <0.001 |

0.5711 0.6651 |

<0.001 <0.001 |

<0.001 <0.001 |

| W-144 | <0.001 <0.001 |

<0.001 <0.001 |

<0.001 <0.001 |

0.9194 0.6376 |

0.0072 0.2151 |

0.0084 0.0987 |

| W-147 | <0.001 <0.001 |

<0.001 <0.001 |

<0.001 <0.001 |

0.6025 0.6647 |

0.328 0.9379 |

0.6368 0.7187 |

| W-101 | <0.001 <0.001 |

<0.001 <0.001 |

<0.001 <0.001 |

0.5528 0.2565 |

0.0023 0.0029 |

0.0135 <0.001 |

| W-110 | <0.001 <0.001 |

<0.001 <0.001 |

<0.001 <0.001 |

0.4615 0.3677 |

0.283 0.1375 |

0.0759 0.0169 |

| W-115 | <0.001 <0.001 |

<0.001 <0.001 |

<0.001 <0.001 |

0.6167 0.3313 |

<0.001 0.0132 |

<0.001 <0.001 |

| W-116 | <0.001 <0.001 |

<0.001 <0.001 |

<0.001 <0.001 |

0.6811 0.2179 |

0.978 0.0992 |

0.710 0.004 |

| W-149 | 0.0033 <0.001 |

0.0043 <0.001 |

<0.001 <0.001 |

0.9535 0.1295 |

0.3711 0.3109 |

0.3448 0.0147 |

| Rural Principal Arterials – Interstate (RPA-I) | ||||||

| A-057 | <0.001 <0.001 |

<0.001 <0.001 |

<0.001 <0.001 |

0.7576 0.4425 |

0.8282 0.3148 |

0.9262 0.8158 |

| A-009 | <0.001 <0.001 |

<0.001 <0.001 |

<0.001 <0.001 |

0.6267 0.3858 |

0.0169 <0.001 |

0.0042 0.0122 |

| A-030 | <0.001 <0.001 |

<0.001 <0.001 |

<0.001 <0.001 |

0.5711 0.9863 |

<0.001 0.0698 |

<0.001 0.6875 |

| A-031 | <0.001 <0.001 |

<0.001 <0.001 |

<0.001 <0.001 |

0.8190 0.4867 |

0.2040 0.9996 |

0.1335 0.5039 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).