Submitted:

18 July 2025

Posted:

21 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

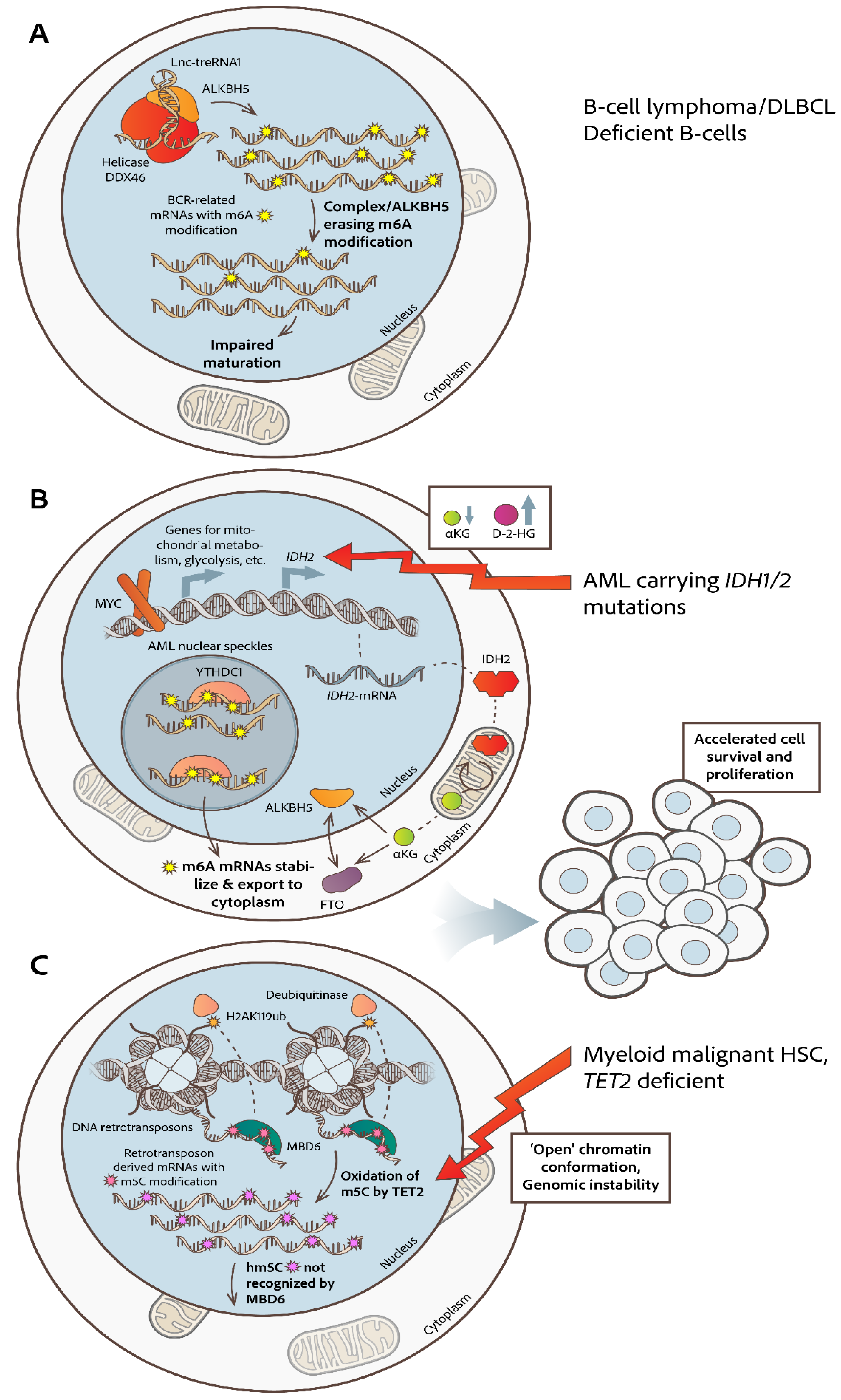

A. Subcellular Dynamics of Chemically Modified RNA Molecules and Their Modifying Enzymes in hematologic malignancies

I. N6-Methyladenosine RNA Modification

II. 5-Methylcytosine (m5C) RNA Modification

III. Pseudouridine (Ψ) RNA Modification

IV. 2′-O-Methylation RNA Modification

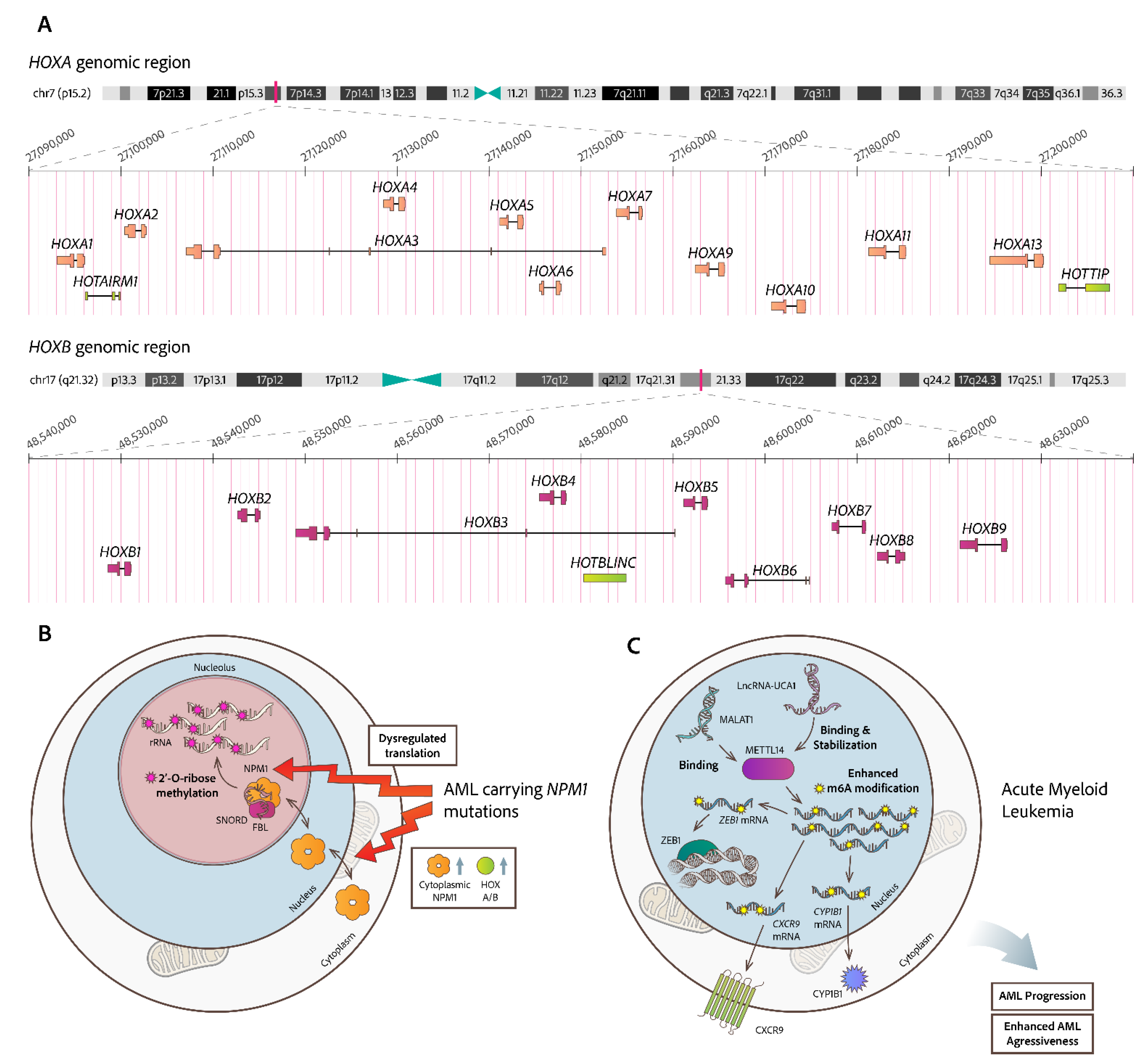

B. Consequences from Altered Subcellular Topology of Non-Coding (nc)RNA Molecules

I. Intracellular Distribution and Function of Micro-RNAs (miRs)

II. Abundance of Long Non-Coding RNAs (lncRNAs) in the Subcellular Compartments

Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kouroukli, O.; Symeonidis, A.; Foukas, P.; Maragkou, M.-K.; Kourea, E.P. Bone Marrow Immune Microenvironment in Myelodysplastic Syndromes. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14, 5656. [CrossRef]

- Godfrey, K.M.; Lillycrop, K.A.; Burdge, G.C.; Gluckman, P.D.; Hanson, M.A. Epigenetic Mechanisms and the Mismatch Concept of the Developmental Origins of Health and Disease. Pediatr Res 2007, 61.

- Boccaletto, P.; MacHnicka, M.A.; Purta, E.; Pitkowski, P.; Baginski, B.; Wirecki, T.K.; De Crécy-Lagard, V.; Ross, R.; Limbach, P.A.; Kotter, A.; et al. MODOMICS: A Database of RNA Modification Pathways. 2017 Update. Nucleic Acids Res 2018, 46, D303–D307. [CrossRef]

- Rebelo-Guiomar, P.; Powell, C.A.; Van Haute, L.; Minczuk, M. The Mammalian Mitochondrial Epitranscriptome. Biochim Biophys Acta Gene Regul Mech 2019, 1862, 429–446.

- van der Werf, I.; Sneifer, J.; Jamieson, C. RNA Modifications Shape Hematopoietic Stem Cell Aging: Beyond the Code. FEBS Lett 2024.

- Khan, I.; Amin, M.A.; Eklund, E.A.; Gartel, A.L. Regulation of HOX Gene Expression in AML. Blood Cancer J 2024, 14, 42. [CrossRef]

- Correction for Garzon et al., Distinctive MicroRNA Signature of Acute Myeloid Leukemia Bearing Cytoplasmic Mutated Nucleophosmin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2024, 121. [CrossRef]

- Falini, B.; Mecucci, C.; Tiacci, E.; Alcalay, M.; Rosati, R.; Pasqualucci, L.; Starza, R. La; Diverio, D.; Colombo, E.; Santucci, A.; et al. Cytoplasmic Nucleophosmin in Acute Myelogenous Leukemia with a Normal Karyotype; 2005;

- Falini, B. NPM1-Mutated Acute Myeloid Leukemia: From Bench to Bedside. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2019004226/1747787/blood.2019004226.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Zardo, G.; Ciolfi, A.; Vian, L.; Starnes, L.M.; Billi, M.; Racanicchi, S.; Maresca, C.; Fazi, F.; Travaglini, L.; Noguera, N.; et al. Polycombs and MicroRNA-223 Regulate Human Granulopoiesis by Transcriptional Control of Target Gene Expression. Blood 2012, 119, 4034–4046. [CrossRef]

- Fazi, F.; Rosa, A.; Fatica, A.; Gelmetti, V.; De Marchis, M.L.; Nervi, C.; Bozzoni, I. A Minicircuitry Comprised of MicroRNA-223 and Transcription Factors NFI-A and C/EBPα Regulates Human Granulopoiesis. Cell 2005, 123, 819–831. [CrossRef]

- Rasko, J.E.J.; Wong, J.J.L. Nuclear MicroRNAs in Normal Hemopoiesis and Cancer. J Hematol Oncol 2017, 10.

- Díaz-Beyá, M.; Brunet, S.; Nomdedéu, J.; Pratcorona, M.; Cordeiro, A.; Gallardo, D.; Escoda, L.; Heras, I.; Ribera, J.M.; Duarte, R.; et al. The LincRNA HOTAIRM1, Located in the HOXA Genomic Region, Is Expressed in Acute Myeloid Leukemia, Impacts Prognosis in Patients in the Intermediate-Risk Cytogenetic Category, and Is Associated with a Distinctive MicroRNA Signature; Vol. 6;.

- Yusufzai, T.M.; Tagami, H.; Nakatani, Y.; Felsenfeld, G. CTCF Tethers an Insulator to Subnuclear Sites, Suggesting Shared Insulator Mechanisms across Species; 2004; Vol. 13;.

- Luo, H.; Zhu, G.; Xu, J.; Lai, Q.; Yan, B.; Guo, Y.; Fung, T.K.; Zeisig, B.B.; Cui, Y.; Zha, J.; et al. HOTTIP LncRNA Promotes Hematopoietic Stem Cell Self-Renewal Leading to AML-like Disease in Mice. Cancer Cell 2019, 36, 645-659.e8. [CrossRef]

- Qing, Y.; Su, R.; Chen, J. RNA Modifications in Hematopoietic Malignancies: A New Research Frontier. Blood 2021, 138, 637–648. [CrossRef]

- Meyer, K.D.; Jaffrey, S.R. The Dynamic Epitranscriptome: N6-Methyladenosine and Gene Expression Control. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2014, 15, 313–326.

- Dominissini, D.; Moshitch-Moshkovitz, S.; Schwartz, S.; Salmon-Divon, M.; Ungar, L.; Osenberg, S.; Cesarkas, K.; Jacob-Hirsch, J.; Amariglio, N.; Kupiec, M.; et al. Topology of the Human and Mouse M6A RNA Methylomes Revealed by M6A-Seq. Nature 2012, 485, 201–206. [CrossRef]

- Ke, S.; Pandya-Jones, A.; Saito, Y.; Fak, J.J.; Vågbø, C.B.; Geula, S.; Hanna, J.H.; Black, D.L.; Darnell, J.E.; Darnell, R.B. M 6 A MRNA Modifications Are Deposited in Nascent Pre-MRNA and Are Not Required for Splicing but Do Specify Cytoplasmic Turnover. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Peng, H. The Role of N6-Methyladenosine (M6A) Methylation Modifications in Hematological Malignancies. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14.

- Trixl, L.; Lusser, A. The Dynamic RNA Modification 5-methylcytosine and Its Emerging Role as an Epitranscriptomic Mark. WIREs RNA 2019, 10. [CrossRef]

- Squires, J.E.; Patel, H.R.; Nousch, M.; Sibbritt, T.; Humphreys, D.T.; Parker, B.J.; Suter, C.M.; Preiss, T. Widespread Occurrence of 5-Methylcytosine in Human Coding and Non-Coding RNA. Nucleic Acids Res 2012, 40, 5023–5033. [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Wang, M.; Gao, S.; Song, G.; Liu, M.; Li, Y.; Sun, P.; Lai, W.; Wang, H.; Yang, Y.G.; et al. RNA M5C Methylation Mediated by Ybx1 Ensures Hematopoietic Stem and Progenitor Cell Expansion. Cell Rep 2025, 44. [CrossRef]

- Cerneckis, J.; Cui, Q.; He, C.; Yi, C.; Shi, Y. Decoding Pseudouridine: An Emerging Target for Therapeutic Development. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2022, 43, 522–535.

- Xiao, W.; Adhikari, S.; Dahal, U.; Chen, Y.S.; Hao, Y.J.; Sun, B.F.; Sun, H.Y.; Li, A.; Ping, X.L.; Lai, W.Y.; et al. Nuclear M6A Reader YTHDC1 Regulates MRNA Splicing. Mol Cell 2016, 61, 507–519. [CrossRef]

- Pendleton, K.E.; Chen, B.; Liu, K.; Hunter, O. V.; Xie, Y.; Tu, B.P.; Conrad, N.K. The U6 SnRNA M6A Methyltransferase METTL16 Regulates SAM Synthetase Intron Retention. Cell 2017, 169, 824-835.e14. [CrossRef]

- Zaccara, S.; Jaffrey, S.R. A Unified Model for the Function of YTHDF Proteins in Regulating M6A-Modified MRNA. Cell 2020, 181, 1582-1595.e18. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Weng, H.; Su, R.; Weng, X.; Zuo, Z.; Li, C.; Huang, H.; Nachtergaele, S.; Dong, L.; Hu, C.; et al. FTO Plays an Oncogenic Role in Acute Myeloid Leukemia as a N6-Methyladenosine RNA Demethylase. Cancer Cell 2017, 31, 127–141. [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Liu, F.; Lu, Z.; Fei, Q.; Ai, Y.; He, P.C.; Shi, H.; Cui, X.; Su, R.; Klungland, A.; et al. Differential m 6 A, m 6 A m , and m 1 A Demethylation Mediated by FTO in the Cell Nucleus and Cytoplasm. Mol Cell 2018, 71, 973-985.e5. [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Yang, Y.; Sun, B.F.; Chen, Y.S.; Xu, J.W.; Lai, W.Y.; Li, A.; Wang, X.; Bhattarai, D.P.; Xiao, W.; et al. 5-Methylcytosine Promotes MRNA Export-NSUN2 as the Methyltransferase and ALYREF as an m 5 C Reader. Cell Res 2017, 27, 606–625. [CrossRef]

- Nachmani, D.; Bothmer, A.H.; Grisendi, S.; Mele, A.; Bothmer, D.; Lee, J.D.; Monteleone, E.; Cheng, K.; Zhang, Y.; Bester, A.C.; et al. Germline NPM1 Mutations Lead to Altered RRNA 2′-O-Methylation and Cause Dyskeratosis Congenita. Nat Genet 2019, 51, 1518–1529. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Aroua, N.; Liu, Y.; Rohde, C.; Cheng, J.; Wirth, A.K.; Fijalkowska, D.; Göllner, S.; Lotze, M.; Yun, H.; et al. A Dynamic RRNA Ribomethylome Drives Stemness in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Cancer Discov 2023, 13, 332–347. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Dou, X.; Chen, C.; Chen, C.; Liu, C.; Michelle Xu, M.; Zhao, S.; Shen, B.; Gao, Y.; Han, D.; et al. N6-Methyladenosine of Chromosome-Associated Regulatory RNA Regulates Chromatin State and Transcription. Science (1979) 2020, 367, 580–586. [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Yin, P. Structural Insights into N6-Methyladenosine (M6A) Modification in the Transcriptome. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics 2018, 16, 85–98.

- Wang, X.; Zhao, B.S.; Roundtree, I.A.; Lu, Z.; Han, D.; Ma, H.; Weng, X.; Chen, K.; Shi, H.; He, C. N6-Methyladenosine Modulates Messenger RNA Translation Efficiency. Cell 2015, 161, 1388–1399. [CrossRef]

- Alarcón, C.R.; Lee, H.; Goodarzi, H.; Halberg, N.; Tavazoie, S.F. N6-Methyladenosine Marks Primary MicroRNAs for Processing. Nature 2015, 519, 482–485. [CrossRef]

- Meyer, K.D.; Patil, D.P.; Zhou, J.; Zinoviev, A.; Skabkin, M.A.; Elemento, O.; Pestova, T. V.; Qian, S.B.; Jaffrey, S.R. 5′ UTR M6A Promotes Cap-Independent Translation. Cell 2015, 163, 999–1010. [CrossRef]

- Hoek, T.A.; Khuperkar, D.; Lindeboom, R.G.H.; Sonneveld, S.; Verhagen, B.M.P.; Boersma, S.; Vermeulen, M.; Tanenbaum, M.E. Single-Molecule Imaging Uncovers Rules Governing Nonsense-Mediated MRNA Decay. Mol Cell 2019, 75, 324-339.e11. [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Zhao, Y.; He, J.; Zhang, Y.; Xi, H.; Liu, M.; Ma, J.; Wu, L. YTHDF2 Destabilizes m 6 A-Containing RNA through Direct Recruitment of the CCR4-NOT Deadenylase Complex. Nat Commun 2016, 7. [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, S.; Zhang, C.; Chen, Y.; Li, W.; Yang, Y.G.; Zhou, Q.; Liu, F. Endothelial-Specific M6A Modulates Mouse Hematopoietic Stem and Progenitor Cell Development via Notch Signaling. Cell Res 2018, 28, 249–252.

- Gao, Y.; Vasic, R.; Song, Y.; Teng, R.; Liu, C.; Gbyli, R.; Biancon, G.; Nelakanti, R.; Lobben, K.; Kudo, E.; et al. M6A Modification Prevents Formation of Endogenous Double-Stranded RNAs and Deleterious Innate Immune Responses during Hematopoietic Development. Immunity 2020, 52, 1007-1021.e8. [CrossRef]

- Weng, H.; Huang, H.; Wu, H.; Qin, X.; Zhao, B.S.; Dong, L.; Shi, H.; Skibbe, J.; Shen, C.; Hu, C.; et al. METTL14 Inhibits Hematopoietic Stem/Progenitor Differentiation and Promotes Leukemogenesis via MRNA M6A Modification. Cell Stem Cell 2018, 22, 191-205.e9. [CrossRef]

- Weng, H.; Huang, H.; Chen, J. N6-Methyladenosine RNA Modification in Normal and Malignant Hematopoiesis. In Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Springer, 2023; Vol. 1442, pp. 105–123.

- Kapadia, B.; Roychowdhury, A.; Kayastha, F.; Lee, W.S.; Nanaji, N.; Windle, J.; Gartenhaus, R. M6A Eraser ALKBH5/TreRNA1/DDX46 Axis Regulates BCR Expression. Neoplasia (United States) 2025, 62. [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Fei, F.; Qiao, F.; Weng, Z.; Yang, Y.; Cao, B.; Yue, J.; Xu, J.; Zheng, M.; Li, J. ALKBH5-Mediated N6-Methyladenosine Modification of TRERNA1 Promotes DLBCL Proliferation via P21 Downregulation. Cell Death Discov 2022, 8. [CrossRef]

- Jaafar, C.; Aguiar, R.C.T. Dynamic Multilayered Control of M6A RNA Demethylase Activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2024, 121. [CrossRef]

- Chang, G.; Xie, G.S.; Ma, L.; Li, L.; Richard, H.T. USP36 Promotes Tumorigenesis and Drug Sensitivity of Glioblastoma by Deubiquitinating and Stabilizing ALKBH5. Neuro Oncol 2023, 25, 841–853. [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; Sheng, Y.; Zhu, A.C.; Robinson, S.; Jiang, X.; Dong, L.; Chen, H.; Su, R.; Yin, Z.; Li, W.; et al. RNA Demethylase ALKBH5 Selectively Promotes Tumorigenesis and Cancer Stem Cell Self-Renewal in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Cell Stem Cell 2020, 27, 64-80.e9. [CrossRef]

- Elkashef, S.M.; Lin, A.P.; Myers, J.; Sill, H.; Jiang, D.; Dahia, P.L.M.; Aguiar, R.C.T. IDH Mutation, Competitive Inhibition of FTO, and RNA Methylation. Cancer Cell 2017, 31, 619–620.

- Qing, Y.; Dong, L.; Gao, L.; Li, C.; Li, Y.; Han, L.; Prince, E.; Tan, B.; Deng, X.; Wetzel, C.; et al. R-2-Hydroxyglutarate Attenuates Aerobic Glycolysis in Leukemia by Targeting the FTO/M6A/PFKP/LDHB Axis. Mol Cell 2021, 81, 922-939.e9. [CrossRef]

- Lin, A.P.; Qiu, Z.; Ethiraj, P.; Sasi, B.; Jaafar, C.; Rakheja, D.; Aguiar, R.C.T. MYC, Mitochondrial Metabolism and O-GlcNAcylation Converge to Modulate the Activity and Subcellular Localization of DNA and RNA Demethylases. Leukemia 2022, 36, 1150–1159. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Z.J.; Lin, A.P.; Jiang, S.; Elkashef, S.M.; Myers, J.; Srikantan, S.; Sasi, B.; Cao, J.Z.; Godley, L.A.; Rakheja, D.; et al. MYC Regulation of D2HGDH and L2HGDH Influences the Epigenome and Epitranscriptome. Cell Chem Biol 2020, 27, 538-550.e7. [CrossRef]

- Stine, Z.E.; Walton, Z.E.; Altman, B.J.; Hsieh, A.L.; Dang, C. V. MYC, Metabolism, and Cancer. Cancer Discov 2015, 5, 1024–1039.

- Cerchione, C.; Romano, A.; Daver, N.; DiNardo, C.; Jabbour, E.J.; Konopleva, M.; Ravandi-Kashani, F.; Kadia, T.; Martelli, M.P.; Isidori, A.; et al. IDH1/IDH2 Inhibition in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Front Oncol 2021, 11.

- Wang, Y.; Zeng, H. min; Xue, Y. juan; Lu, A. dong; Jia, Y. ping; Zuo, Y. xi; Zhang, L. ping The Gene Expression Level of M6A Catalytic Enzymes Is Increased in ETV6/RUNX1-Positive Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Int J Lab Hematol 2021, 43, e89–e91.

- Liu, X.; Huang, L.; Huang, K.; Yang, L.; Yang, X.; Luo, A.; Cai, M.; Wu, X.; Liu, X.; Yan, Y.; et al. Novel Associations Between METTL3 Gene Polymorphisms and Pediatric Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: A Five-Center Case-Control Study. Front Oncol 2021, 11. [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Fan, G.; Li, Q.; Su, Q.; Zhang, X.; Xue, X.; Wang, Z.; Qian, C.; Jin, Z.; Li, B.; et al. IDH2 Contributes to Tumorigenesis and Poor Prognosis by Regulating M6A RNA Methylation in Multiple Myeloma. Oncogene 2021, 40, 5393–5402. [CrossRef]

- Qu, J.; Hou, Y.; Chen, Q.; Chen, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, E.; Gu, H.; Xu, R.; Liu, Y.; Cao, W.; et al. RNA Demethylase ALKBH5 Promotes Tumorigenesis in Multiple Myeloma via TRAF1-Mediated Activation of NF-ΚB and MAPK Signaling Pathways. Oncogene 2022, 41, 400–413. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Xie, W.; Pickering, B.F.; Chu, K.L.; Savino, A.M.; Yang, X.; Luo, H.; Nguyen, D.T.; Mo, S.; Barin, E.; et al. N6-Methyladenosine on MRNA Facilitates a Phase-Separated Nuclear Body That Suppresses Myeloid Leukemic Differentiation. Cancer Cell 2021, 39, 958-972.e8. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Su, R.; Sheng, Y.; Dong, L.; Dong, Z.; Xu, H.; Ni, T.; Zhang, Z.S.; Zhang, T.; Li, C.; et al. Small-Molecule Targeting of Oncogenic FTO Demethylase in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Cancer Cell 2019, 35, 677-691.e10. [CrossRef]

- Cao, K.; Du, Y.; Bao, X.; Han, M.; Su, R.; Pang, J.; Liu, S.; Shi, Z.; Yan, F.; Feng, S. Glutathione-Bioimprinted Nanoparticles Targeting of N6-methyladenosine FTO Demethylase as a Strategy against Leukemic Stem Cells. Small 2022, 18. [CrossRef]

- Selberg, S.; Seli, N.; Kankuri, E.; Karelson, M. Rational Design of Novel Anticancer Small-Molecule RNA M6A Demethylase ALKBH5 Inhibitors. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 13310–13320. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-Z.; Li, H.-Y.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, R.-X.; Xu, J.; Gu, J.; Jiang, Z.; Jiang, Z.-Y.; You, Q.-D.; Guo, X.-K. Discovery of Pyrazolo[1,5-a]Pyrimidine Derivative as a Novel and Selective ALKBH5 Inhibitor for the Treatment of AML. J Med Chem 2023, 66, 15944–15959. [CrossRef]

- Zou, Z.; Dou, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, J.; Gao, B.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, L.; Sun, C.; et al. RNA M5C Oxidation by TET2 Regulates Chromatin State and Leukaemogenesis. Nature 2024. [CrossRef]

- Amort, T.; Rieder, D.; Wille, A.; Khokhlova-Cubberley, D.; Riml, C.; Trixl, L.; Jia, X.Y.; Micura, R.; Lusser, A. Distinct 5-Methylcytosine Profiles in Poly(A) RNA from Mouse Embryonic Stem Cells and Brain. Genome Biol 2017, 18. [CrossRef]

- Bohnsack, K.E.; Höbartner, C.; Bohnsack, M.T. Eukaryotic 5-Methylcytosine (M 5 C) RNA Methyltransferases: Mechanisms, Cellular Functions, and Links to Disease. Genes (Basel) 2019, 10.

- Goll, M.G.; Kirpekar, F.; Maggert, K.A.; Yoder, J.A.; Hsieh, C.-L.; Zhang, X.; Golic, K.G.; Jacobsen, S.E.; Bestor, T.H. Methylation of TRNA Asp by the DNA Methyltransferase Homolog Dnmt2;

- Blanco, S.; Dietmann, S.; Flores, J. V; Hussain, S.; Kutter, C.; Humphreys, P.; Lukk, M.; Lombard, P.; Treps, L.; Popis, M.; et al. Aberrant Methylation of t RNA s Links Cellular Stress to Neuro-developmental Disorders . EMBO J 2014, 33, 2020–2039. [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.; Sajini, A.A.; Blanco, S.; Dietmann, S.; Lombard, P.; Sugimoto, Y.; Paramor, M.; Gleeson, J.G.; Odom, D.T.; Ule, J.; et al. NSun2-Mediated Cytosine-5 Methylation of Vault Noncoding RNA Determines Its Processing into Regulatory Small RNAs. Cell Rep 2013, 4, 255–261. [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Guerrero, C.R.; Zhong, N.; Amato, N.J.; Liu, Y.; Liu, S.; Cai, Q.; Ji, D.; Jin, S.G.; Niedernhofer, L.J.; et al. Tet-Mediated Formation of 5-Hydroxymethylcytosine in RNA. J Am Chem Soc 2014, 136, 11582–11585. [CrossRef]

- Moran-Crusio, K.; Reavie, L.; Shih, A.; Abdel-Wahab, O.; Ndiaye-Lobry, D.; Lobry, C.; Figueroa, M.E.; Vasanthakumar, A.; Patel, J.; Zhao, X.; et al. Tet2 Loss Leads to Increased Hematopoietic Stem Cell Self-Renewal and Myeloid Transformation. Cancer Cell 2011, 20, 11–24. [CrossRef]

- Delhommeau, F.; Dupont, S.; Valle, V. Della; James, C.; Trannoy, S.; Massé, A.; Kosmider, O.; Le Couedic, J.-P.; Robert, F.; Alberdi, A.; et al. Mutation in TET2 in Myeloid Cancers. New England Journal of Medicine 2009, 360, 2289–2301. [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Bajpai, A.K.; Wu, F.; Lu, W.; Xu, L.; Mao, J.; Li, Q.; Pan, Q.; Lu, L.; Wang, X. 5-Methylcytosine RNA Modification Regulators-Based Patterns and Features of Immune Microenvironment in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Aging 2024. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, H.; Dong, L.; Zhang, X.; Xue, M.; Ren, L.; Bi, H.; Ghoda, L.Y.; Wunderlich, M.; Mulloy, J.C.; et al. Mitochondrial RNA Methylation By METTL17 Rewires Metabolism and Regulates Retrograde Mitochondrial-Nuclear Communication in AML. Blood 2024, 144, 625–625. [CrossRef]

- Ge, J.; Yu, Y.T. RNA Pseudouridylation: New Insights into an Old Modification. Trends Biochem Sci 2013, 38, 210–218.

- Mcmahon, M.; Contreras, A.; Ruggero, D. Small RNAs with Big Implications: New Insights into H/ACA SnoRNA Function and Their Role in Human Disease. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA 2015, 6, 173–189.

- Schwartz, S.; Bernstein, D.A.; Mumbach, M.R.; Jovanovic, M.; Herbst, R.H.; León-Ricardo, B.X.; Engreitz, J.M.; Guttman, M.; Satija, R.; Lander, E.S.; et al. Transcriptome-Wide Mapping Reveals Widespread Dynamic-Regulated Pseudouridylation of NcRNA and MRNA. Cell 2014, 159, 148–162. [CrossRef]

- Grosjean, H.; Sprinzl, M.; Steinberg, S. Posttranscriptiona||y Modified Nucleosides in Transfer RNA: Their Locations and Frequencies; 1995; Vol. 77;.

- Motorin, Y.; Helm, M. TRNA Stabilization by Modified Nucleotides. Biochemistry 2010, 49, 4934–4944.

- Liang, X.H.; Liu, Q.; Fournier, M.J. Loss of RRNA Modifications in the Decoding Center of the Ribosome Impairs Translation and Strongly Delays Pre-RRNA Processing. RNA 2009, 15, 1716–1728. [CrossRef]

- Piekna-Przybylska, D.; Przybylski, P.; Baudin-Baillieu, A.; Rousset, J.P.; Fournier, M.J. Ribosome Performance Is Enhanced by a Rich Cluster of Pseudouridines in the A-Site Finger Region of the Large Subunit. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2008, 283, 26026–26036. [CrossRef]

- Yu, A.T.; Ge, J.; Yu, Y.T. Pseudouridines in Spliceosomal SnRNAs. Protein Cell 2011, 2, 712–725.

- Su, H.; Hu, J.; Huang, L.; Yang, Y.; Thenoz, M.; Kuchmiy, A.; Hu, Y.; Li, P.; Feng, H.; Zhou, Y.; et al. SHQ1 Regulation of RNA Splicing Is Required for T-Lymphoblastic Leukemia Cell Survival. Nat Commun 2018, 9. [CrossRef]

- Karikó, K.; Muramatsu, H.; Keller, J.M.; Weissman, D. Increased Erythropoiesis in Mice Injected with Submicrogram Quantities of Pseudouridine-Containing MRNA Encoding Erythropoietin. Molecular Therapy 2012, 20, 948–953. [CrossRef]

- Kurimoto, R.; Chiba, T.; Ito, Y.; Matsushima, T.; Yano, Y.; Miyata, K.; Yashiro, Y.; Suzuki, T.; Tomita, K.; Asahara, H. The TRNA Pseudouridine Synthase TruB1 Regulates the Maturation of Let-7 MiRNA. EMBO J 2020, 39. [CrossRef]

- Herridge, R.P.; Dolata, J.; Migliori, V.; de Santis Alves, C.; Borges, F.; Schorn, A.J.; van Ex, F.; Lin, A.; Bajczyk, M.; Parent, J.S.; et al. Pseudouridine Guides Germline Small RNA Transport and Epigenetic Inheritance. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2024. [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Shi, D.; Yang, S.; Lian, Y.; Li, H.; Cao, M.; He, Y.; Zhang, L.; Qiu, C.; Liu, T.; et al. Mitochondrial TRNA Pseudouridylation Governs Erythropoiesis. Blood 2024, 144, 657–671. [CrossRef]

- Guzzi, N.; Muthukumar, S.; Cieśla, M.; Todisco, G.; Ngoc, P.C.T.; Madej, M.; Munita, R.; Fazio, S.; Ekström, S.; Mortera-Blanco, T.; et al. Pseudouridine-Modified TRNA Fragments Repress Aberrant Protein Synthesis and Predict Leukaemic Progression in Myelodysplastic Syndrome. Nat Cell Biol 2022, 24, 299–306. [CrossRef]

- Bellodi, C.; McMahon, M.; Contreras, A.; Juliano, D.; Kopmar, N.; Nakamura, T.; Maltby, D.; Burlingame, A.; Savage, S.A.; Shimamura, A.; et al. H/ACA Small RNA Dysfunctions in Disease Reveal Key Roles for Noncoding RNA Modifications in Hematopoietic Stem Cell Differentiation. Cell Rep 2013, 3, 1493–1502. [CrossRef]

- Iwakawa, H.; Tomari, Y. Life of RISC: Formation, Action, and Degradation of RNA-Induced Silencing Complex. Mol Cell 2022, 82, 30–43. [CrossRef]

- Castanotto, D.; Lingeman, R.; Riggs, A.D.; Rossi, J.J. CRM1 Mediates Nuclear-Cytoplasmic Shuttling of Mature MicroRNAs. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2009, 106, 21655–21659. [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Li, L.; Wang, D.; Zhang, C.-Y.; Zen, K. Importin 8 Regulates the Transport of Mature MicroRNAs into the Cell Nucleus. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2014, 289, 10270–10275. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, H.-W.; Wentzel, E.A.; Mendell, J.T. A Hexanucleotide Element Directs MicroRNA Nuclear Import. Science (1979) 2007, 315, 97–100. [CrossRef]

- Turunen, T.A.; Roberts, T.C.; Laitinen, P.; Väänänen, M.-A.; Korhonen, P.; Malm, T.; Ylä-Herttuala, S.; Turunen, M.P. Changes in Nuclear and Cytoplasmic MicroRNA Distribution in Response to Hypoxic Stress. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 10332. [CrossRef]

- Zisoulis, D.G.; Kai, Z.S.; Chang, R.K.; Pasquinelli, A.E. Autoregulation of MicroRNA Biogenesis by Let-7 and Argonaute. Nature 2012, 486, 541–544. [CrossRef]

- Nishi, K.; Nishi, A.; Nagasawa, T.; Ui-Tei, K. Human TNRC6A Is an Argonaute-Navigator Protein for MicroRNA-Mediated Gene Silencing in the Nucleus. RNA 2013, 19, 17–35. [CrossRef]

- Jeffries, C.D.; Fried, H.M.; Perkins, D.O. Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Localization of Neural Stem Cell MicroRNAs. RNA 2011, 17, 675–686. [CrossRef]

- Zardo, G.; Ciolfi, A.; Vian, L.; Starnes, L.M.; Billi, M.; Racanicchi, S.; Maresca, C.; Fazi, F.; Travaglini, L.; Noguera, N.; et al. Polycombs and MicroRNA-223 Regulate Human Granulopoiesis by Transcriptional Control of Target Gene Expression. Blood 2012, 119, 4034–4046. [CrossRef]

- Fazi, F.; Rosa, A.; Fatica, A.; Gelmetti, V.; De Marchis, M.L.; Nervi, C.; Bozzoni, I. A Minicircuitry Comprised of MicroRNA-223 and Transcription Factors NFI-A and C/EBPα Regulates Human Granulopoiesis. Cell 2005, 123, 819–831. [CrossRef]

- Pulikkan, J.A.; Dengler, V.; Peramangalam, P.S.; Peer Zada, A.A.; Müller-Tidow, C.; Bohlander, S.K.; Tenen, D.G.; Behre, G. Cell-Cycle Regulator E2F1 and MicroRNA-223 Comprise an Autoregulatory Negative Feedback Loop in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Blood 2010, 115, 1768–1778. [CrossRef]

- Rasko, J.E.J.; Wong, J.J.-L. Nuclear MicroRNAs in Normal Hemopoiesis and Cancer. J Hematol Oncol 2017, 10, 8. [CrossRef]

- Hegde, V.L.; Tomar, S.; Jackson, A.; Rao, R.; Yang, X.; Singh, U.P.; Singh, N.P.; Nagarkatti, P.S.; Nagarkatti, M. Distinct MicroRNA Expression Profile and Targeted Biological Pathways in Functional Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells Induced by Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinol in Vivo. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2013, 288, 36810–36826. [CrossRef]

- Porse, B.T.; Bryder, D.; Theilgaard-Mönch, K.; Hasemann, M.S.; Anderson, K.; Damgaard, I.; Jacobsen, S.E.W.; Nerlov, C. Loss of C/EBPα Cell Cycle Control Increases Myeloid Progenitor Proliferation and Transforms the Neutrophil Granulocyte Lineage. Journal of Experimental Medicine 2005, 202, 85–96. [CrossRef]

- Bauer, M.; Vaxevanis, C.; Heimer, N.; Al-Ali, H.K.; Jaekel, N.; Bachmann, M.; Wickenhauser, C.; Seliger, B. Expression, Regulation and Function of MicroRNA as Important Players in the Transition of MDS to Secondary AML and Their Cross Talk to RNA-Binding Proteins. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 7140. [CrossRef]

- Haferlach, T.; Nagata, Y.; Grossmann, V.; Okuno, Y.; Bacher, U.; Nagae, G.; Schnittger, S.; Sanada, M.; Kon, A.; Alpermann, T.; et al. Landscape of Genetic Lesions in 944 Patients with Myelodysplastic Syndromes. Leukemia 2014, 28, 241–247. [CrossRef]

- Papaemmanuil, E.; Cazzola, M.; Boultwood, J.; Malcovati, L.; Vyas, P.; Bowen, D.; Pellagatti, A.; Wainscoat, J.S.; Hellstrom-Lindberg, E.; Gambacorti-Passerini, C.; et al. Somatic SF3B1 Mutation in Myelodysplasia with Ring Sideroblasts . New England Journal of Medicine 2011, 365, 1384–1395. [CrossRef]

- Berezikov, E.; Chung, W.-J.; Willis, J.; Cuppen, E.; Lai, E.C. Mammalian Mirtron Genes. Mol Cell 2007, 28, 328–336. [CrossRef]

- Aslan, D.; Garde, C.; Katrine Nygaard, M.; Søgaard Helbo, A.; Dimopoulos, K.; Werner Hansen, J.; Tang Severinsen, M.; Bach Treppendahl, M.; Dissing Sjø, L.; Grønbaek, K.; et al. Tumor Suppressor MicroRNAs Are Downregulated in Myelodysplastic Syndrome with Spliceosome Mutations; 2016;

- Mercer, T.R.; Neph, S.; Dinger, M.E.; Crawford, J.; Smith, M.A.; Shearwood, A.-M.J.; Haugen, E.; Bracken, C.P.; Rackham, O.; Stamatoyannopoulos, J.A.; et al. The Human Mitochondrial Transcriptome. Cell 2011, 146, 645–658. [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; An, X.; Xiao, Y.; Sun, X.; Li, S.; Wang, Y.; Sun, W.; Yu, D. Mitochondrial-Related MicroRNAs and Their Roles in Cellular Senescence. Front Physiol 2024, 14. [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Fan, G.; Song, S.; Jiang, Y.; Qian, C.; Zhang, W.; Su, Q.; Xue, X.; Zhuang, W.; Li, B. PiRNA-30473 Contributes to Tumorigenesis and Poor Prognosis by Regulating M6A RNA Methylation in DLBCL. Blood 2021, 137, 1603–1614. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Qu, L.; Sang, L.; Wu, X.; Jiang, A.; Liu, J.; Lin, A. Micropeptides Translated from Putative Long Noncoding RNAs. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 2022. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Xu, M.; Huang, S. Long Noncoding RNAs: Emerging Regulators of Normal and Malignant Hematopoiesis. Blood 2021, 138, 2327–2336. [CrossRef]

- van Heesch, S.; van Iterson, M.; Jacobi, J.; Boymans, S.; Essers, P.B.; de Bruijn, E.; Hao, W.; MacInnes, A.W.; Cuppen, E.; Simonis, M. Extensive Localization of Long Noncoding RNAs to the Cytosol and Mono- and Polyribosomal Complexes. Genome Biol 2014, 15, R6. [CrossRef]

- Djebali, S.; Davis, C.A.; Merkel, A.; Dobin, A.; Lassmann, T.; Mortazavi, A.; Tanzer, A.; Lagarde, J.; Lin, W.; Schlesinger, F.; et al. Landscape of Transcription in Human Cells. Nature 2012, 489, 101–108. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Luo, H.; Feng, Y.; Guryanova, O.A.; Xu, J.; Chen, S.; Lai, Q.; Sharma, A.; Xu, B.; Zhao, Z.; et al. HOXBLINC Long Non-Coding RNA Activation Promotes Leukemogenesis in NPM1-Mutant Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Nat Commun 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Beyá, M.; Brunet, S.; Nomdedéu, J.; Pratcorona, M.; Cordeiro, A.; Gallardo, D.; Escoda, L.; Tormo, M.; Heras, I.; Ribera, J.M.; et al. The LincRNA HOTAIRM1, Located in the HOXA Genomic Region, Is Expressed in Acute Myeloid Leukemia, Impacts Prognosis in Patients in the Intermediate-Risk Cytogenetic Category, and Is Associated with a Distinctive MicroRNA Signature. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 31613–31627. [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.C.; Yang, Y.W.; Liu, B.; Sanyal, A.; Corces-Zimmerman, R.; Chen, Y.; Lajoie, B.R.; Protacio, A.; Flynn, R.A.; Gupta, R.A.; et al. A Long Noncoding RNA Maintains Active Chromatin to Coordinate Homeotic Gene Expression. Nature 2011, 472, 120–126. [CrossRef]

- Gourvest, M.; De Clara, E.; Wu, H.-C.; Touriol, C.; Meggetto, F.; De Thé, H.; Pyronnet, S.; Brousset, P.; Bousquet, M. A Novel Leukemic Route of Mutant NPM1 through Nuclear Import of the Overexpressed Long Noncoding RNA LONA. Leukemia 2021, 35, 2784–2798. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, Z.; Bai, X.; Chen, X.; Wang, M.; Wu, Y.; Wu, H. LncRNA UCA1 Promotes the Progression of AML by Upregulating the Expression of CXCR4 and CYP1B1 by Affecting the Stability of METTL14. J Oncol 2022, 2022, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Fu, L.; Hong, P.; Feng, W. MALAT-1 Regulates the AML Progression by Promoting the M6A Modification of ZEB1. Acta Biochim Pol 2023. [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, M.E.; Clayton, D.A. Nuclear RNase MRP Is Required for Correct Processing of Pre-5.8S RRNA in Saccharomyces Cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol 1993, 13, 7935–7941. [CrossRef]

- Maida, Y.; Yasukawa, M.; Furuuchi, M.; Lassmann, T.; Possemato, R.; Okamoto, N.; Kasim, V.; Hayashizaki, Y.; Hahn, W.C.; Masutomi, K. An RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase Formed by TERT and the RMRP RNA. Nature 2009, 461, 230–235. [CrossRef]

- Noh, J.H.; Kim, K.M.; Abdelmohsen, K.; Yoon, J.-H.; Panda, A.C.; Munk, R.; Kim, J.; Curtis, J.; Moad, C.A.; Wohler, C.M.; et al. HuR and GRSF1 Modulate the Nuclear Export and Mitochondrial Localization of the LncRNA RMRP. Genes Dev 2016, 30, 1224–1239. [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Zhang, H.; Mei, Y.; Wu, M. Reciprocal Regulation of HIF-1α and LincRNA-P21 Modulates the Warburg Effect. Mol Cell 2014, 53, 88–100. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, P.; Xiong, Q.; Wu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Z.; Fleming, J.; Gao, D.; Bi, L.; Ge, F. Quantitative Proteomics Analysis Reveals Novel Insights into Mechanisms of Action of Long Noncoding RNA Hox Transcript Antisense Intergenic RNA (HOTAIR) in HeLa Cells*. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics 2015, 14, 1447–1463. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Sun, L.; Wang, R.R.; Hu, J.-F.; Cui, J. The Effects of Mitochondria-Associated Long Noncoding RNAs in Cancer Mitochondria: New Players in an Old Arena. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2018, 131, 76–82. [CrossRef]

- Rackham, O.; Shearwood, A.-M.J.; Mercer, T.R.; Davies, S.M.K.; Mattick, J.S.; Filipovska, A. Long Noncoding RNAs Are Generated from the Mitochondrial Genome and Regulated by Nuclear-Encoded Proteins. RNA 2011, 17, 2085–2093. [CrossRef]

- Landerer, E.; Villegas, J.; Burzio, V.A.; Oliveira, L.; Villota, C.; Lopez, C.; Restovic, F.; Martinez, R.; Castillo, O.; Burzio, L.O. Nuclear Localization of the Mitochondrial NcRNAs in Normal and Cancer Cells. Cellular Oncology 2011, 34, 297–305. [CrossRef]

- Bianchessi, V.; Badi, I.; Bertolotti, M.; Nigro, P.; D’Alessandra, Y.; Capogrossi, M.C.; Zanobini, M.; Pompilio, G.; Raucci, A.; Lauri, A. The Mitochondrial LncRNA ASncmtRNA-2 Is Induced in Aging and Replicative Senescence in Endothelial Cells. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2015, 81, 62–70. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Sun, H.; Wang, C.; Liu, W.; Liu, M.; Zhu, Y.; Xu, W.; Jin, H.; Li, J. Mitochondrial Genome-Derived CircRNA Mc-COX2 Functions as an Oncogene in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 2020, 20, 801–811. [CrossRef]

- Burzio, V.A.; Villota, C.; Villegas, J.; Landerer, E.; Boccardo, E.; Villa, L.L.; Martínez, R.; Lopez, C.; Gaete, F.; Toro, V.; et al. Expression of a Family of Noncoding Mitochondrial RNAs Distinguishes Normal from Cancer Cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2009, 106, 9430–9434. [CrossRef]

- Querfeld, C.; Foss, F.M.; Kim, Y.H.; Pinter-Brown, L.; William, B.M.; Porcu, P.; Pacheco, T.; Haverkos, B.M.; DeSimone, J.; Guitart, J.; et al. Phase 1 Trial of Cobomarsen, an Inhibitor of Mir-155, in Cutaneous T Cell Lymphoma. Blood 2018, 132, 2903–2903. [CrossRef]

| Inhibitor | target | disease | REF |

|---|---|---|---|

| R-2 hydroxyglutarate (FTO inhibitor) | inhibits aerobic glycolysis without affecting HSCs | sensitive leukemia cells | [50] |

| FB23 and FB23-2 (FTO inhibitor) |

Directly bind to FTO and inhibit he progression of human AML cells | AML | [60] |

| glutathione (GSH) bioimprinted nanocomposite material, GNPIPP12MA, loaded with FTO inhibitors | GNPIPP12MA targets the FTO/m6A pathway, synergistically enhancing anti-leukemia effects by depleting GSH | leukemia stem cells | [61] |

| Zantrene (FTO inhibitor) |

Targeted inhibitor of FTO | AML | Phase I clinical trial (NCT05456269) |

| 2-(2-hydroxyethylsulfanyl)acetic acid (RD3) and 4-[(methyl)amino]-3,6-dioxo (RD6) (ALKBH5 inhibitors) | Decreased cell viability at low concentrations | Leukemia cell lines | [62] |

| Pyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidine (DO-2728a) (ALKBH5 inhibitor) | Enhances m6A modification abundance and impedes cell cycle progression | AML | [63] |

| MiRNA | Regulation in MDS/AML vs healthy or AA (aplastic anemia) |

|---|---|

| hsa-miR-130a-3p | Significantly higher in de novo MDS vs AA |

| hsa-miR-221-3p | Significantly higher in de novo MDS vs AA |

| hsa-miR-126-3p | Significantly higher in de novo MDS vs AA |

| hsa-miR-27b-3p | Significantly higher in de novo MDS vs AA |

| hsa-miR-196b-5p | Significantly higher in de novo MDS vs AA |

| hsa-let-7e-5p | Upregulated in de novo MDS vs AA |

| hsa-miR-181c-5p | Associated with progression to sAML |

| hsa-miR-155 | Downregulated in MDS (prognostic value) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).