Introduction

Mood disorders represent a major global health burden, with depression and bipolar disorder constituting two of the most prevalent and disabling forms. Among them, anxiety-induced depression (AoD) remains understudied in terms of its longitudinal course and neurodevelopmental risks. Emerging evidence suggests that anxiety, particularly when chronic and untreated during adolescence, may serve not only as a comorbid symptom but as a prodromal phase of more severe affective disorders. This paper aims to explore the neurobiological trajectory that links chronic anxiety to depression and, in high-risk individuals, to eventual bipolar conversion. This paper further hypothesizes that AoD may not only heighten bipolar risk but also shape its eventual subtype, favoring Bipolar II or Rapid Cycling due to white matter vulnerabilities.

Theoretical Background

The comorbidity of anxiety and depression has long been recognized, yet most nosological frameworks, such as DSM-5 and ICD-11, conceptualize them as parallel or overlapping disorders rather than causally connected phases in a unified pathological trajectory. However, clinical observations frequently report that early-life anxiety, especially generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) and social anxiety, often precedes the onset of major depressive disorder (MDD), suggesting a potential sequential relationship.

Neurodevelopmentally, adolescence represents a period of heightened vulnerability to affective dysregulation due to rapid structural remodeling in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus. During this stage, persistent anxiety symptoms may promote maladaptive plasticity in emotion-related circuits, particularly via GABAergic overactivation, disrupted excitatory/inhibitory (E/I) balance, and stress-induced synaptic pruning. These early neural changes, if unresolved, may transition into the affective and cognitive patterns characteristic of MDD.

More concerningly, a subset of individuals with anxiety-originated depression (AoD) may develop features typical of bipolar disorder (BD) over time, including affective lability, impulsivity, and treatment resistance. This phenomenon raises the hypothesis that AoD constitutes a distinct neuroprogressive subtype of mood disorder, one that differs mechanistically from primary MDD and may require specific early-stage identification and intervention strategies.

Neurobiological Features of Anxiety-Originated Depression

Anxiety-originated depression (AoD) is often characterized by early alterations in inhibitory neural systems, particularly within the prefrontal cortex. Prolonged GABAergic overactivation, as observed in adolescents with persistent anxiety symptoms, may lead to structural degeneration of prefrontal pyramidal neurons. A recent optogenetic study in juvenile mice demonstrated that 7 days of sustained GABA activation resulted in a 28% reduction in dendritic spine density, a change comparable to 21-day chronic stress models.

This imbalance in excitatory/inhibitory (E/I) signaling not only disrupts prefrontal connectivity, but also impairs feedback regulation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, making the brain more vulnerable to glucocorticoid-mediated toxicity. Additionally, microglial surveillance is altered, with sustained stress and elevated GABA levels triggering premature or excessive synaptic pruning. Epigenetic dysregulations, such as H3K9me3 enrichment at the Grin2a promoter and miR-132 methylation, further suppress NMDA receptor activity and BDNF translation, limiting compensatory plasticity.

These changes collectively suggest that AoD is not merely “depression with anxiety traits,” but a distinct biological condition marked by unique neurotoxic trajectories that prime the brain for affective instability and reduced resilience.

Neurotoxic Progression and Bipolar Conversion

While some individuals with AoD exhibit partial remission after standard antidepressant treatment, others follow a progressively deteriorating course. Clinical studies show that patients with an early anxiety-depression profile are significantly more likely to develop bipolar features—particularly mixed episodes, impulsivity, and affective lability—within 5–7 years of onset.

This transition may be mediated by a compounding neurotoxic cascade: GABA-induced dendritic atrophy → impaired HPA feedback → glucocorticoid accumulation → synaptic scaffolding loss (e.g., PSD-95 degradation) → NMDA receptor overactivation → microglial hyperactivation → excessive synaptic pruning in prefrontal and hippocampal circuits. Once this loop becomes self-reinforcing, even minimal stress may trigger functional disintegration.

Furthermore, adolescent vulnerability amplifies the impact of this progression. Epigenetically, miR-218 dysregulation during this stage can disrupt prefrontal synaptic remodeling and increase BD risk. Functional imaging studies reveal that individuals with AoD exhibit reduced prefrontal-limbic coherence and poor emotion–cognition integration—a hallmark observed in bipolar I conversion trajectories.

Pharmacological Overload and Network Fragility

Both selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and benzodiazepines (BZDs) are widely prescribed for anxiety and depression, yet their excessive use—particularly in adolescents with anxiety-originated depression—may paradoxically exacerbate neuroprogressive trajectories.

Supratherapeutic doses of SSRIs can desensitize 5-HT1A receptors, suppress hippocampal neurogenesis, and disrupt prefrontal–hippocampal coherence. Meanwhile, benzodiazepine overdose impairs mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, leading to ATP depletion in energy-sensitive brain regions. This metabolic disruption can weaken synaptic maintenance, compromise glutamate clearance, and intensify NMDA-mediated excitotoxicity.

Together, pharmacological overload may act as an iatrogenic “second hit,” magnifying endogenous vulnerabilities and accelerating the transition from affective instability to bipolar conversion—especially when mood-stabilizing interventions are lacking. These iatrogenic effects may be particularly detrimental in individuals with pre-existing white matter vulnerability, as seen in AoD cases, further accelerating the progression toward more refractory bipolar subtypes.

Theoretical Model: A Neuroprogressive Pathway from Anxiety to Bipolar Disorder

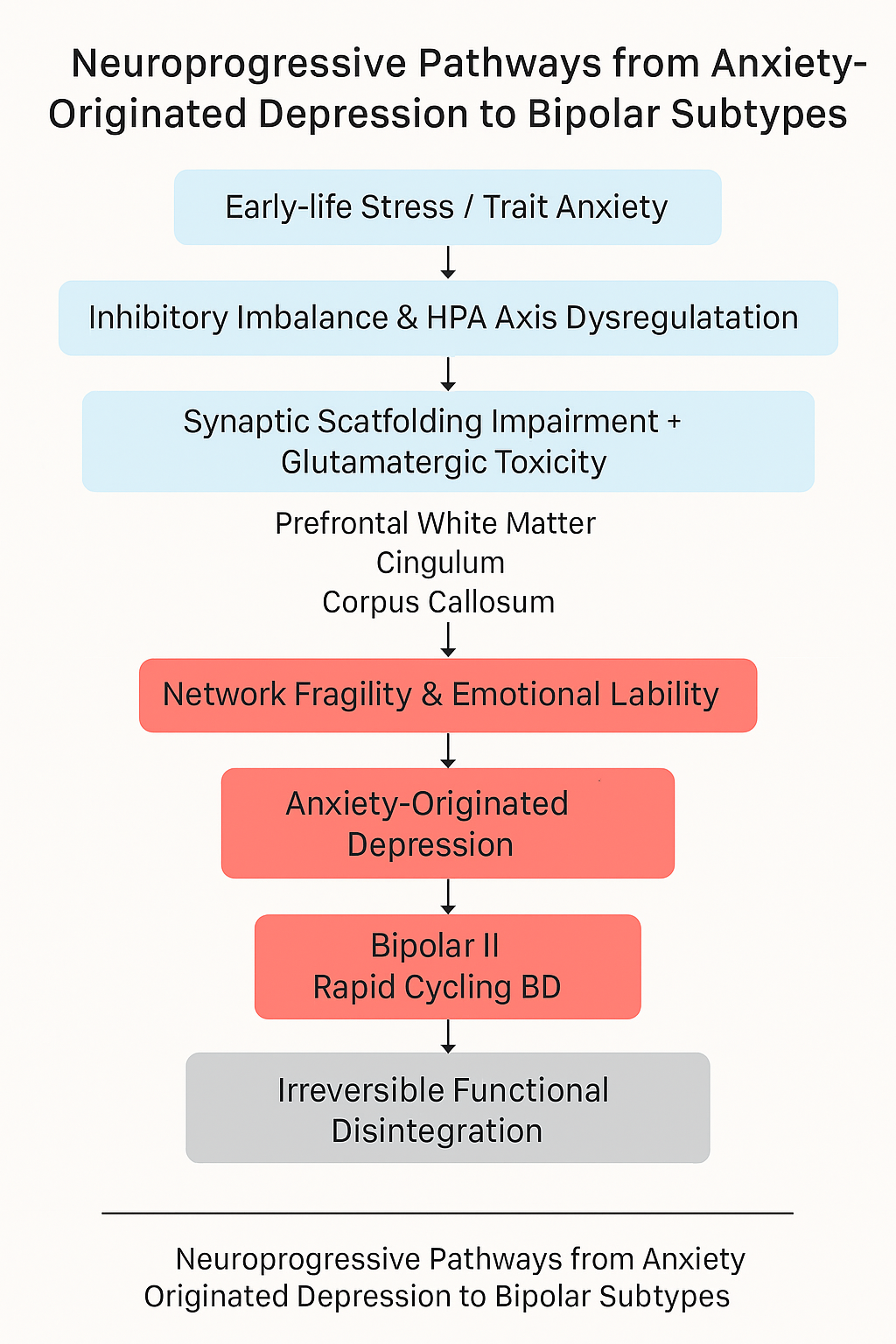

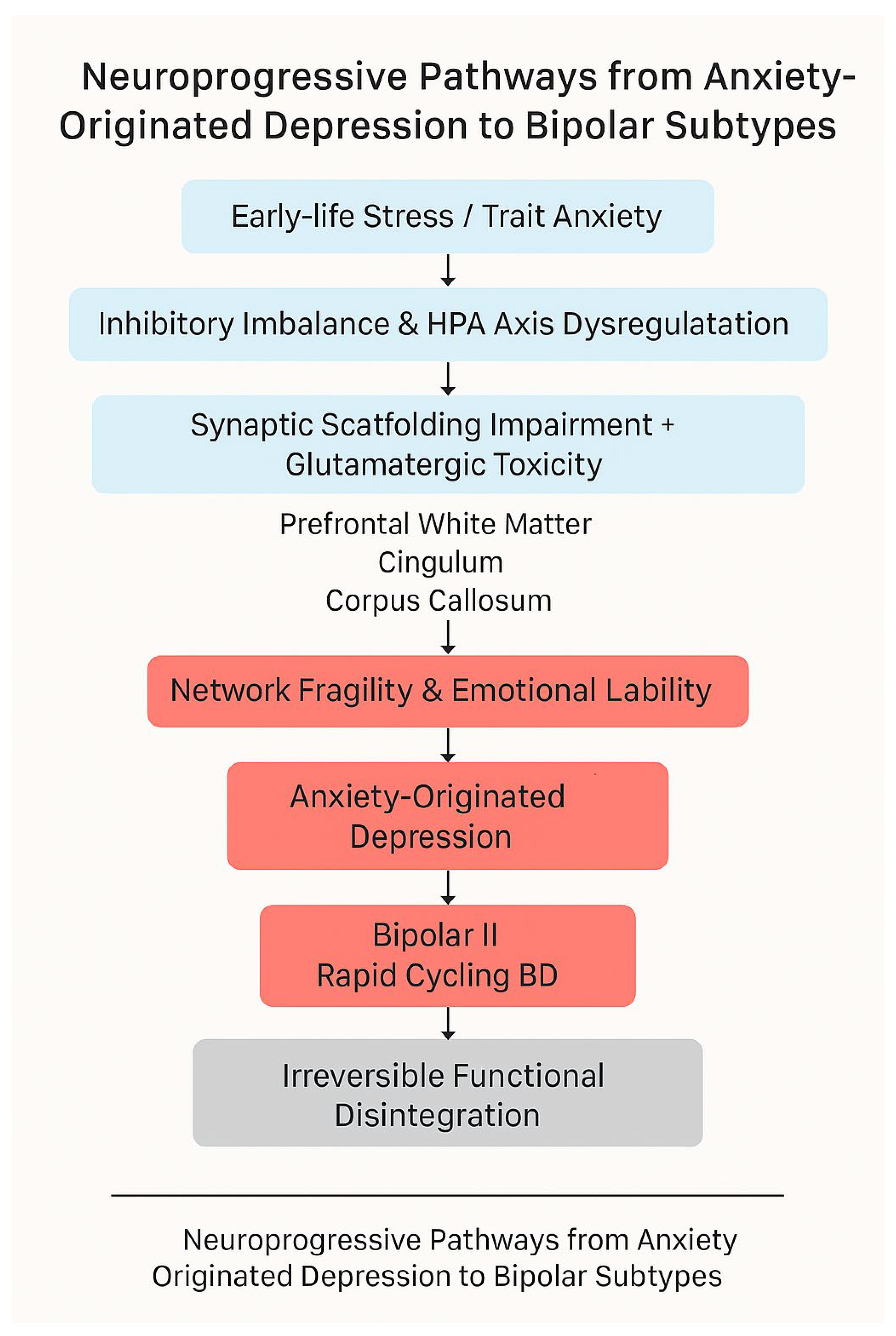

We propose a neuroprogressive model in which chronic anxiety initiates a cascade of pathological changes that gradually reshape the emotional and cognitive architecture of the brain. The model unfolds in the following sequential stages:

Chronic Anxiety & HPA Axis Overactivation

Persistent psychological threat perception chronically activates the HPA axis, leading to sustained glucocorticoid exposure.

GABAergic Overactivation & Prefrontal Synaptic Impairment

Excessive GABA activity in adolescence reduces hippocampal-prefrontal dendritic spine density and disrupts excitatory/inhibitory (E/I) balance.

Glucocorticoid Accumulation & Synaptic Scaffolding Loss

HPA dysregulation results in elevated cortisol, degrading scaffolding proteins (e.g., PSD-95), weakening hippocampal-prefrontal connectivity.

NMDA Receptor Overactivation & Microglial Hyperactivity

Excess glutamate activates NMDA receptors, triggering neuroinflammation and aberrant synaptic pruning by microglia.

Functional Network Disintegration

The cumulative effect leads to prefrontal-limbic decoupling, emotional instability, and heightened risk of bipolar transition.

This stepwise degeneration transforms what begins as anxiety-related affective disturbance into a structurally ingrained, treatment-resistant mood disorder.

Clinical Implications and Diagnostic Challenges

Given the proposed link between AoD and specific bipolar subtypes, understanding its clinical implications becomes imperative.

Recognizing AoD as a potential precursor to specific bipolar subtypes carries important clinical implications. Traditional diagnostic frameworks often categorize anxious-depressive syndromes under unipolar depression, overlooking longitudinal trajectory and neuroprogressive risks. The tendency to misclassify early prodromal states of bipolar disorder delays intervention and may inadvertently contribute to worse long-term outcomes.

Furthermore, AoD patients frequently present with high levels of internalized distress and cognitive inhibition, making them less likely to disclose affective instability until manic or hypomanic symptoms become overt. Diagnostic tools that rely solely on current mood symptoms may thus miss underlying vulnerability to bipolar conversion.

Clinicians should be trained to identify neurocognitive warning signs, including white matter damage and memory consolidation deficits, and utilize neuroimaging or longitudinal affective profiling where feasible. Incorporating early life stress history, inhibitory control performance, and trait anxiety markers into diagnostic decision-making may enhance predictive validity for bipolar onset and subtype trajectory.

Future Directions and Intervention Strategies

To prevent the irreversible neurodegeneration associated with AoD-to-BD conversion, early identification and targeted intervention are paramount. Neuroprotective strategies—such as anti-inflammatory treatment, glutamatergic modulation, and myelin repair agents—should be explored in high-risk AoD populations, especially those with visible white matter disruption.

Behavioral therapies tailored to inhibitory dysfunction (e.g., cognitive control training, mindfulness-based stress reduction) may offer adjunctive benefits, potentially restoring top-down regulation in prefrontal networks. Longitudinal digital phenotyping could aid in real-time detection of affective instability before syndromal thresholds are crossed.

Future studies should focus on delineating subtype-specific neural biomarkers and intervention response profiles. The trajectory from AoD to BD may be modifiable—if caught early enough—with consequences not only for preventing bipolar onset but also for shaping which subtype develops. Such stratified strategies may not only prevent irreversible deterioration but also restore long-term affective stability.”

Conclusion

Anxiety-induced depression should be reconceptualized not merely as a depressive subtype with anxious features, but as a dynamic neuroprogressive condition with unique developmental risks. Our model underscores how early-life stress and inhibitory imbalance initiate a cascade of neurobiological damage that compromises prefrontal–hippocampal circuits and primes the brain for affective instability. Moreover, AoD may preferentially lead to Bipolar II or Rapid Cycling subtypes due to selective white matter vulnerabilities, especially when left untreated. Early detection and targeted neuroprotective interventions may thus not only prevent irreversible network disintegration but also influence the eventual bipolar subtype trajectory.

References

- Alloy, L. B., Abramson, L. Y., Walshaw, P. D., Cogswell, A., Hughes, M. E., Iacoviello, B. M., ... & Hogan, M. E. (2015). Behavioral approach system (BAS)-relevant cognitive styles and bipolar spectrum disorders: Concurrent and prospective associations. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, *124*(4), 840–855. [CrossRef]

- Perugi, G., Pallucchini, A., Rizzato, S., & Madaro, D. (2017). Anxiety disorders and bipolar disorder comorbidity: A clinical and therapeutic challenge. Frontiers in Psychiatry, *8*, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Benedetti, F., Bollettini, I., Barberini, M., Radaelli, D., Poletti, S., Locatelli, C., ... & Colombo, C. (2011). Lithium and GABAergic effects on brain activation during emotional tasks in bipolar depression. Psychological Medicine, *41*(10), 2119–2131.

- Benedetti, F., Yeh, P. H., Bellani, M., Radaelli, D., Nicoletti, M. A., Poletti, S., ... & Brambilla, P. (2013). Disruption of white matter integrity in bipolar depression as a possible structural marker of illness. Biological Psychiatry, *74*(6), 422–432. [CrossRef]

- Cruz, N., Sánchez-Moreno, J., Torres, F., Goikolea, J. M., Valentí, M., Vieta, E., & Martinez-Aran, A. (2008). Clinical predictors of rapid cycling in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disorders, *10*(6), 718–725. [CrossRef]

- Korgaonkar, M. S., Grieve, S. M., Etkin, A., Koslow, S. H., Williams, L. M., & Gordon, E. (2014). Using multimodal neuroimaging to dissect the role of white matter abnormalities in bipolar disorder. Molecular Psychiatry, *19*(12), 1234–1240. [CrossRef]

- Mahon, K., Burdick, K. E., Wu, J., Ardekani, B. A., & Szeszko, P. R. (2009). Relationship between white matter integrity and cognitive function in early bipolar disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders, *114*(1–3), 153–162. [CrossRef]

- Depue, R. A., & Iacono, W. G. (1989). Neurobehavioral aspects of affective disorders. Annual Review of Psychology, *40*(1), 457–492. [CrossRef]

- Hibar, D. P., Westlye, L. T., van Erp, T. G. M., Rasmussen, J., Leonardo, C. D., Faskowitz, J., ... & Thompson, P. M. (2018). Subcortical volumetric abnormalities in bipolar disorder. Molecular Psychiatry, *23*(3), 639–646. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Wang, Y., Hu, J., Li, T., & Zhang, X. (2021). Disrupted white matter microstructural integrity in first-episode, drug-naive patients with anxiety disorders. NeuroImage: Clinical, *30*, 102574. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., Su, S., & Liu, C. (2023). Longitudinal mapping of rapid cycling and bipolar subtypes using neuroimaging. Journal of Affective Disorders, *326*, 122–130. [CrossRef]

- Favre, P., Pauling, M., Stout, J., Hozer, F., Sarrazin, S., Abé, C., ... & Houenou, J. (2019). Widespread white matter microstructural abnormalities in bipolar disorder: Evidence from mega- and meta-analyses across 3,033 individuals. Biological Psychiatry, *86*(1), 35–44. [CrossRef]

- Gitlin, M., & Malhi, G. S. (2020). The difficult lives of bipolar II disorder. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, *54*(9), 803–805. [CrossRef]

- Perugi, G., Hantouche, E., Vannucchi, G., Pinto, O., & Vieta, E. (2017). Anxiety symptoms as precursors of bipolar disorder: A longitudinal analysis. BMC Psychiatry, *17*, Article 271.

- Schneck, C. D., Miklowitz, D. J., Calabrese, J. R., Allen, M. H., Thomas, M. R., Wisniewski, S. R., ... & Sachs, G. S. (2004). Phenomenology of rapid-cycling bipolar disorder: Data from the first 500 participants in the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program. The British Journal of Psychiatry, *184*(Suppl 44), s30–s36. [CrossRef]

- Tondo, L., Baldessarini, R. J., Hennen, J., & Floris, G. (2003). Rapid cycling bipolar disorder: Effects of long-term treatments. American Journal of Psychiatry, *160*(5), 904–910. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).