1. Introduction

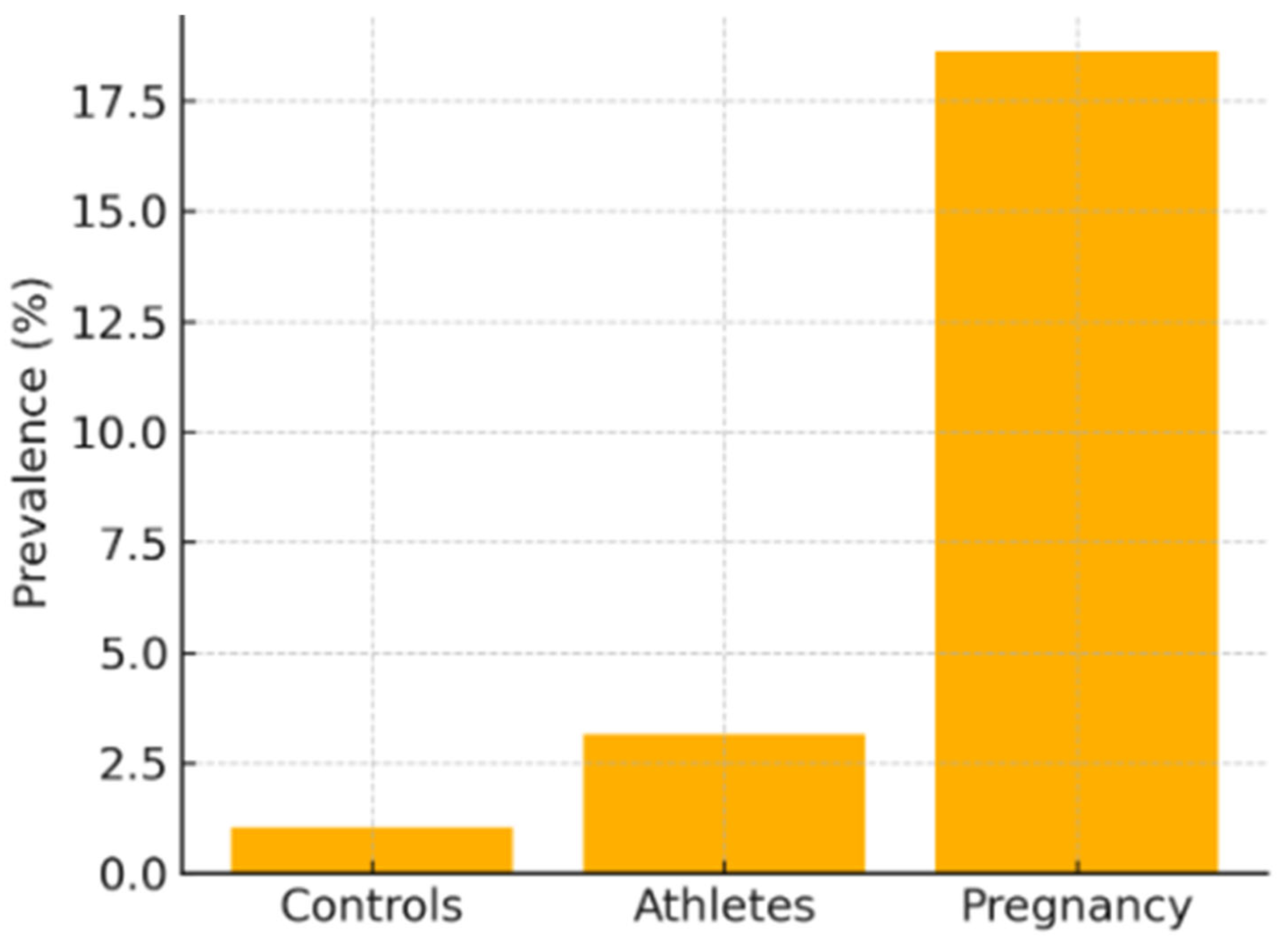

LVNC is characterized by a spongy ventricular architecture with thick trabeculae and deep recesses filled with blood [1]. It was initially attributed to an embryonic compaction failure between weeks five and eight, although current genetic evidence places it within a common spectrum with DCM and HCM [2,3,13]. The European Society of Cardiology lists it among “unclassified” cardiomyopathies, whereas the American Heart Association includes it among primary congenital forms [11]. Prevalence depends on imaging technique and population: Ross et al. found 1.05 % in healthy controls, 3.16 % in athletes, and up to 18.6 % in pregnant women using echocardiography [12]; CMR raises detection to 14.8 %, and the disparity between criteria—Petersen identifies 39 % versus Captur’s 3 %—shows a considerable risk of over-diagnosis [3,15]. Described phenotypes include isolated non-compaction with normal function; dilated and hypertrophic variants overlapping DCM and HCM [13,21]; the form associated with congenital heart disease such as Tetralogy of Fallot [16]; and acquired, reversible hyper-trabeculation observed in pregnancy, athletes, and sickle-cell anemia [29]. In the current era, cardiomyopathies are increasingly managed with a precision-medicine mindset that tailors diagnostics and therapy to the individual’s molecular and phenotypic profile. LVNC, with its marked genotype–phenotype variability and reversible forms (e.g., pregnancy, athletic remodeling), offers a unique window to apply and test such approaches [36].

Objective of the review: To comprehensively describe the pathophysiology, epidemiology, clinical presentation, diagnostic methods, differential diagnosis, treatment, and research perspectives of LVNC using evidence available up to April 2025.

Figure 1 compares the prevalence of non-compaction cardiomyopathy (NCC) detected by echocardiography in three cohorts without apparent cardiovascular symptoms studied by Ross et al. [12]. The vertical axis shows the percentage of subjects who met at least one of the morphological criteria (Chin, Jenni, or Stöllberger), while the horizontal axis groups the general healthy population (controls), elite athletes (athletes), and women in the third trimester of pregnancy (pregnancy).

The graph illustrates that cardiac hyper-trabeculation is an uncommon finding in controls (about 1 percent), triples in athletes (around 3 percent), and reaches its highest level in pregnant women (close to 19 percent). It is important to emphasize that most of these diagnoses involve asymptomatic individuals and that, in the case of pregnant women, longitudinal follow-up showed regression of the trabeculations in 1 out of 4 cases one year postpartum.

Therefore, the figure highlights the influence of physiological states—athletic adaptation or the hemodynamic overload of pregnancy—on the appearance of non-compaction patterns that can regress or lack pathological significance, underscoring the need to interpret echocardiographic criteria within the specific clinical context.

2. Materials and Methods

A literature search was carried out using the terms non-compaction cardiomyopathy, left-ventricular non-compaction, and hyper-trabeculation—and their Spanish equivalents—in PubMed, Scopus, and Google Scholar, covering January 2000 to April 2025. Two independent reviewers screened 1,243 abstracts and selected 30 works that met inclusion criteria: clinical studies with a minimum of ten patients, meta-analyses, narrative reviews, or consensus documents focused on pathophysiology, genetics, imaging, clinical aspects, prognosis, or treatment. Quality was assessed with the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale for observational studies and the AMSTAR checklist for meta-analyses; discrepancies were resolved by consensus. Meta-analyses, reviews, and consensus statements with explicit relevance to personalized or precision cardiology (e.g., genotype–phenotype correlation, AI-driven imaging analytics, pharmacogenomics) were prioritized when available.

3. Results

Etiology and Pathogenesis

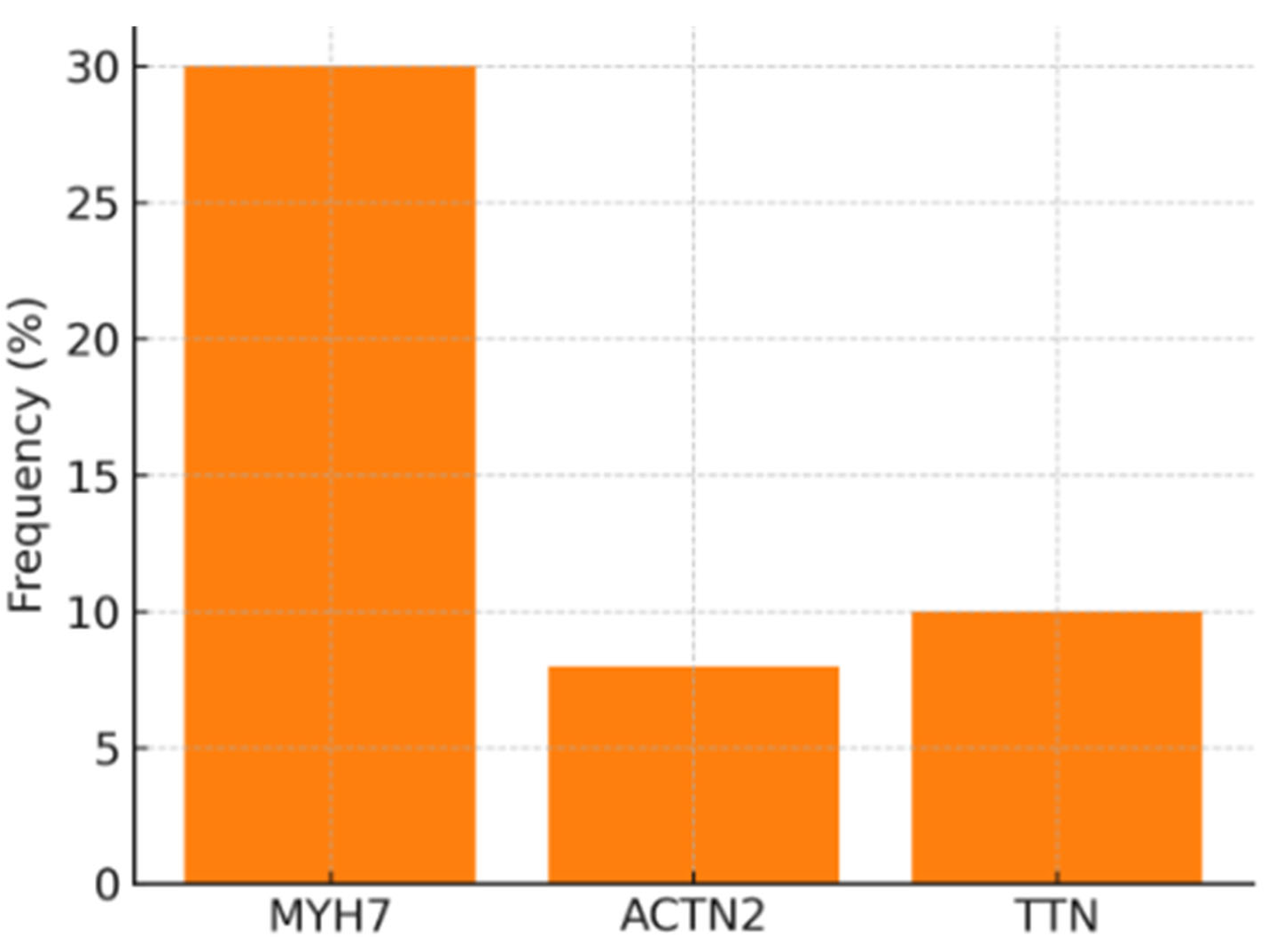

Left-ventricular non-compaction is chiefly associated with mutations in the MYH7 and ACTN2 genes, accounting for between twenty-four and thirty-eight percent of cases and shared with dilated and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy [13]. Truncating or missense variants in TTN and other cytoskeletal genes contribute an additional ten percent [9]. These findings support the notion of a cardiomyopathic continuum: the same mutation may express as non-compaction, dilation, or hypertrophy depending on epigenetic interaction and hemodynamic environment.

The classic embryonic hypothesis attributed the disease to a compaction failure between weeks five and eight, but human histological sections do not show the expected reduction in trabeculae; murine models with sarcomeric over-expression reproduce the phenotype through hyper-trabecular proliferation rather than failed compaction [11,13].

At the molecular level, activation of the MAPK-AKT, NOTCH-BMP10 and TGF-β pathways amplifies the mechanical-stress signal, induces hyper-trabeculation and promotes fibrosis that is detected as late gadolinium enhancement. Impaired oxidative phosphorylation lowers the phosphocreatine-to-ATP reserve, reflecting a compromised bio-energetic state. In vivo models reinforce these findings: MIB1 knock-out mice develop lethal hyper-trabeculation, and zebrafish with titin deletions reproduce the non-compaction pattern; iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes carrying MYH7 variants display α-actinin disorganization and delayed mitochondrial maturation. In these models, adeno-associated viral vectors restoring MYBPC3 expression or correcting TTN deletions have normalized ventricular morphology.

Figure 2 summarizes the genetic findings from the two largest series published to date on non-compaction cardiomyopathy (NCC) [12,13]. The vertical axis shows the percentage of patients carrying pathogenic variants, while the horizontal axis groups the three most frequently involved genes: MYH7 (β-myosin heavy chain), ACTN2 (α-actinin-2) and TTN (titin).

The graph indicates that nearly one-third of cases are associated with mutations in MYH7, roughly eight percent with ACTN2, and about ten percent with variants in TTN. This pattern supports the hypothesis that sarcomere disruption is the principal molecular mechanism of the disease and explains its phenotypic overlap with dilated and hypertrophic cardiomyopathies. In addition, the unequal gene distribution helps to prioritize genetic testing: a panel focused on MYH7 and TTN would cover approximately 40 percent of confirmed molecular diagnoses.

Dialogue between extracellular matrix and metabolism modulates the disease. Athletes show a transient rise in insulin-like growth factor and heat-shock proteins, favoring reversible hypertrophy; in pathological LVNC, persistent mechanosensitive signaling disturbs calcium handling and generates oxidative stress. Transcriptomic studies identify over-expression of NOTCH1, BMP10 and collagen type I and III genes. Phosphorus-31 spectroscopy demonstrates a lower energetic reserve in symptomatic patients.

Pharmacogenomics adds clinical nuances: carriers of truncating TTN mutations respond poorly to sacubitril–valsartan, whereas MYH7 missense variants associate with better reverse-remodeling on SGLT2 inhibitors. The CYP2C9*3 polymorphism raises warfarin levels and bleeding risk, supporting preferential use of direct oral anticoagulants when trabecular mass is high or atrial fibrillation is present.

Since Chin’s first systematic description [1] in 1990, publications on LVNC have grown at fourteen percent per year; fewer than twelve percent are prospective studies and barely three percent are clinical trials. To redress this gap, an agenda is proposed that prioritizes gene-silencing or CRISPR editing therapies, multicenter registries combining three-dimensional CMR, artificial intelligence and third-generation sequencing, and early-intervention trials with SGLT2 inhibitors in asymptomatic carriers. The collaborative LVNC-Net aims to integrate genotype and phenotype of more than 5,000 patients, externally validate a prognostic algorithm and facilitate adaptive gene-therapy trials.

Socio-economic impact is notable: direct European costs reach €3,600 per patient annually, while indirect costs double that figure. In middle-income countries, lack of CMR raises under-diagnosis to forty-seven percent and delays guideline quadruple therapy, justifying expansion of simplified imaging platforms and affordable gene panels.

Clinical Presentation and Prognosis

Expression of LVNC ranges from an incidental CMR finding to overt heart failure with malignant arrhythmias. In the largest series, heart failure appears in up to sixty-one percent of cases, atrial fibrillation ranges between fifteen and twenty-three percent, and sustained ventricular tachycardia reaches forty-seven percent [8,9,25]. The triad of left-ventricular ejection fraction below forty percent, wide extension of non-compacted myocardium, and fibrosis detected as late gadolinium enhancement doubles the cumulative probability of death or transplant [8,19].

Vaidya and colleagues showed that extension of the non-compaction pattern beyond the apex combined with an ejection fraction below fifty percent reduces population-adjusted survival by about twenty percent at ten years [9]. Thrombo-embolic burden is also significant: apical thrombi and atrial fibrillation increase systemic-embolism risk by fifteen to thirty-eight percent over the general population, and every five-percent rise in trabeculated mass multiplies embolic risk nine-fold [23,30].

The disease displays particular traits in specific groups. In infants, one-third are diagnosed before two years of age and frequently coexist with congenital heart disease or metabolic disorders; ten-year survival is seventy-two percent and depends on baseline ejection fraction and ventricular arrhythmias [26]. During gestation, transient hyper-trabeculation may occur: Ross et al. documented that one in four pregnant women meeting morphological criteria normalized ventricular morphology one year postpartum, so definitive diagnosis should be deferred six months unless severe dysfunction is present [12].

In elite athletes, an NC/C ratio above 2.3 is observed in up to eight percent using Petersen criteria, although only 0.7 percent meet the stricter definition that adds systolic dysfunction or fibrosis; in Afro-descendant males the physiological threshold seems even higher, underlining the need for sex- and ethnicity-specific cut-offs [29]. Approximately thirty-two percent of affected individuals present hereditary neuromuscular diseases such as Barth syndrome, Duchenne muscular dystrophy or Charcot–Marie–Tooth neuropathy, and this coexistence triples mortality (hazard ratio ≈ 3.1) [11].

Serum biomarkers contribute to stratification: plasma NT-proBNP correlates linearly with trabecular mass and anticipates heart-failure hospitalizations [19]; pilot studies show micro-RNAs such as miR-499 and miR-133a discriminate LVNC from dilated cardiomyopathy, though external validation is needed. Integrating gene panels with proteomics and transcriptomics could clarify incomplete penetrance of sarcomeric mutations and refine individual event prediction.

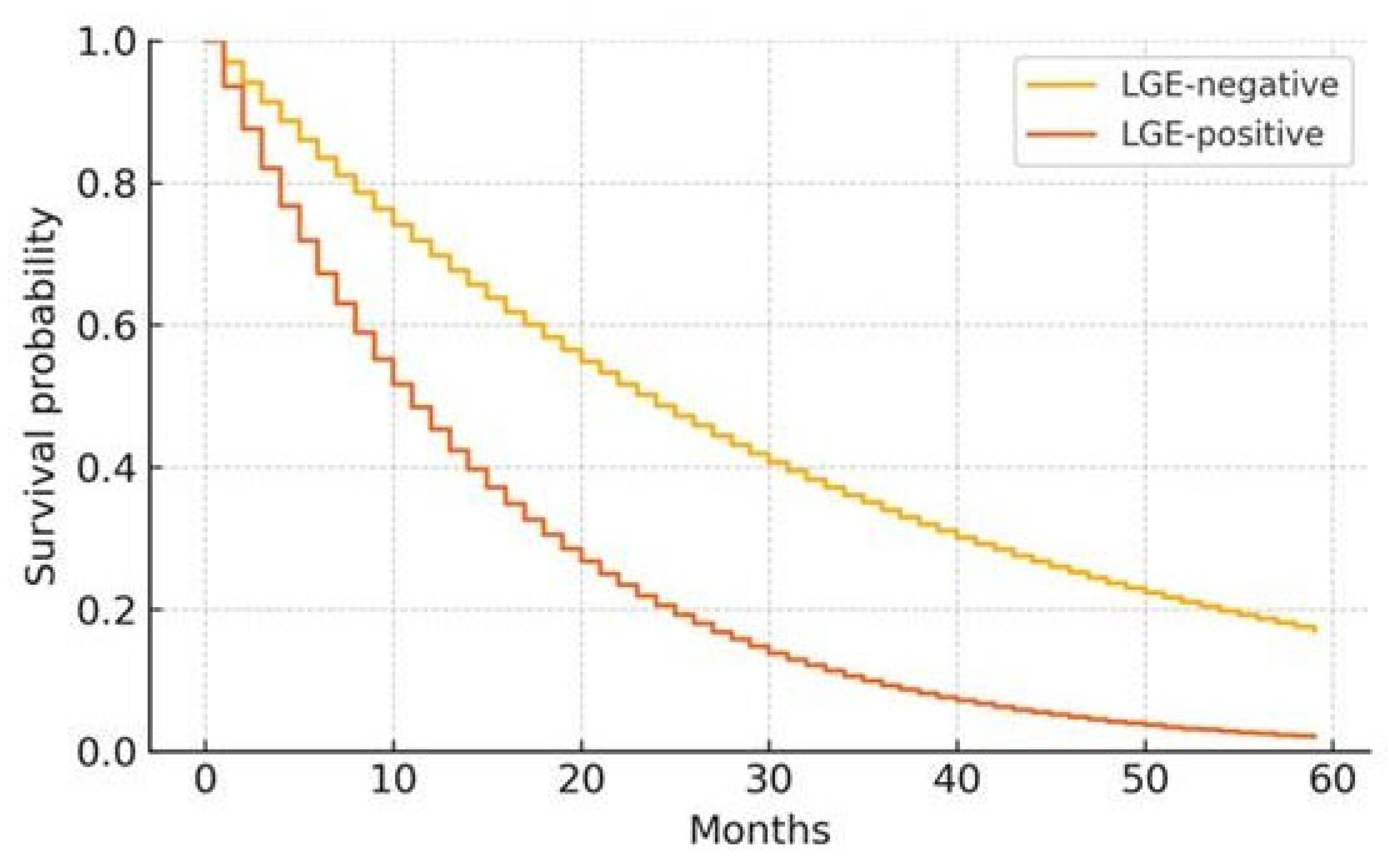

Figure 3 displays Kaplan–Meier curves for major event–free survival (death, transplant, or heart-failure hospitalization) in a cohort of patients with non-compaction cardiomyopathy followed over five years [8]. The vertical axis shows the cumulative probability of remaining event-free, while the horizontal axis indicates time in months.

The steeper orange line corresponds to patients with late gadolinium enhancement (LGE-positive); the yellow line to those without enhancement (LGE-negative). Event-free survival declines more rapidly in the LGE-positive group: at 12 months the probability falls to about 70 percent and drops below 20 percent by 60 months, whereas in the non-fibrosis group it still exceeds 40 percent at the end of follow-up. Multivariable analysis in the original study assigned LGE a relative risk of roughly 2.2 for the composite outcome, confirming myocardial fibrosis as the most powerful single prognostic marker in this disease.

Overall, available evidence places annual mortality at roughly four-point-eight percent with high heterogeneity (I2 = 67 %) and confirms myocardial fibrosis as the single most powerful prognostic marker; however, most studies are retrospective, apply varying diagnostic criteria, and originate from tertiary European or North-American centers, limiting extrapolation to populations with limited CMR access.

Personalized-Risk Stratification and Genotype–Phenotype Correlations

The multinational LVNC-Net registry (> 5 000 patients) shows that MYH7 truncating variants combined with diffuse LGE double the 5-year risk of transplantation [38], whereas ACTN2 carriers with preserved LVEF exhibit outcomes comparable to other DCM phenotypes.

Machine-learning models integrating NC/C ratio, strain imaging and polygenic risk scores reach an AUC of 0.88 for predicting malignant arrhythmias [39]. These tools set the stage for individualized ICD decisions beyond the current LVEF ≤ 35 % rule.

Diagnostic Methodology

Echocardiography employs several established criteria:

Chin criterion, based on an X/Y ratio ≤ 0.5 in diastole [1];

Jenni criterion, pathological when a non-compacted/compacted (NC/C) ratio > 2 in systole [2];

Stöllberger criterion, which diagnoses the disease when three or more prominent trabeculae with inter-trabecular perfusion are seen and an NC/C ratio > 2 [14].

However, echocardiographic specificity can fall below 70 % in populations such as athletes and pregnant women [29].

Cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) offers greater diagnostic precision. According to the Petersen criterion, LVNC is diagnosed when an NC/C ratio ≥ 2.3 in diastole [3]; Jacquier instead proposes a threshold based on trabeculated mass, considered pathological when it exceeds 20 % of total left-ventricular mass [4]. Myocardial fibrosis detected by late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) is associated with up to a two-fold increase in adverse events [8]. Three-dimensional processing using artificial-intelligence algorithms has improved diagnostic reproducibility, with area-under-the-curve (AUC) values ranging 0.86–0.92 [22].

Electrocardiogram may reveal abnormalities such as bundle-branch block and fragmented QRS complexes, which correlate with LGE [16]. Multidetector computed tomography applies an NC/C ratio > 2.2 in at least two ventricular segments [4]. Endomyocardial biopsy is reserved for suspected infiltrative myopathies [26].

Advanced CMR techniques—native T1 and T2 mapping—detect oedema and diffuse fibrosis before LGE becomes evident. Global longitudinal strain analysis identifies sub-clinical myocardial dysfunction. Positron-emission tomography (PET) with fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) shows heterogeneous uptake, often overlapping regions of abnormal strain. Moreover, tracers targeted to activated fibroblasts visualize active myocardial remodeling [34].

Differential Diagnosis

Physiological hyper-trabeculation seen in athletes, reversible cardiac dilation of pregnancy, and conditions such as sickle-cell anemia may display elevated NC/C ratios. Nevertheless, these entities are characterized by preserved systolic function and absence of myocardial fibrosis, differentiating them from structural cardiomyopathy. Differential diagnosis must also consider apical cardiomyopathy, arrhythmogenic right-ventricular dysplasia, cardiac amyloidosis, Fabry disease, and tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy.

The most widely accepted practical algorithm first requires identification of compatible morphology using validated imaging techniques. However, LVNC should be diagnosed in asymptomatic patients only if at least one of the following myocardial-injury markers is documented: systolic dysfunction, presence of fibrosis, or ventricular arrhythmias.

Treatment

Therapeutic approach is structured according to ejection fraction, arrhythmic burden, and symptom presence, as summarized in

Table 1.

Table 1 – Summary of Therapeutic Interventions for NCC.

The table outlines recommended treatments according to the clinical status of patients with non-compaction cardiomyopathy (NCC):.

Asymptomatic carriers with LVEF > 50 %.

Symptomatic heart-failure phase.

LVEF ≤ 35 % or sustained ventricular tachycardia.

QRS width ≥ 130 ms.

Atrial fibrillation or prior embolic event.

Taken together, the table integrates current evidence and offers a clear scheme for individualizing NCC management in clinical practice.

In cases with preserved ejection fraction and no symptoms, annual follow-up including imaging (echocardiography or CMR) and Holter monitoring is sufficient. In symptomatic heart failure, guideline quadruple therapy is recommended.

Device and Interventional Indications:

LVEF ≤ 35 % or sustained VT justifies prophylactic ICD implantation.

A wide QRS complex (≥ 130 ms) may benefit from CRT.

Atrial fibrillation or a prior embolic event requires lifelong anticoagulation, preferably with direct oral anticoagulants.

Advanced Options:

Surgery: Apical trabecular resection, with ≈10-point LVEF improvement at one year.

Ablation: Reduces sustained-VT recurrence to 18 % at 3 years.

Left-ventricular assist device: Bridge to transplant with 82 % one-year survival, without complications attributable to hyper-trabeculation.

Gene therapies: Adeno-associated vectors (e.g., targeting MYBPC3 or TTN) normalized cardiac morphology in murine models; RNA-interference silencing is at pre-clinical stage.

Follow-Up and Lifestyle:

Control: Every six months in the first year, then annually, with echocardiography/CMR, Holter, and NT-proBNP (if LVEF > 50 %).

-

Exercise:

- o

Recreational—moderate intensity; contraindicated if fibrosis or arrhythmias are present.

- o

Competitive—only with normal LVEF and exercise test free of VT.

- o

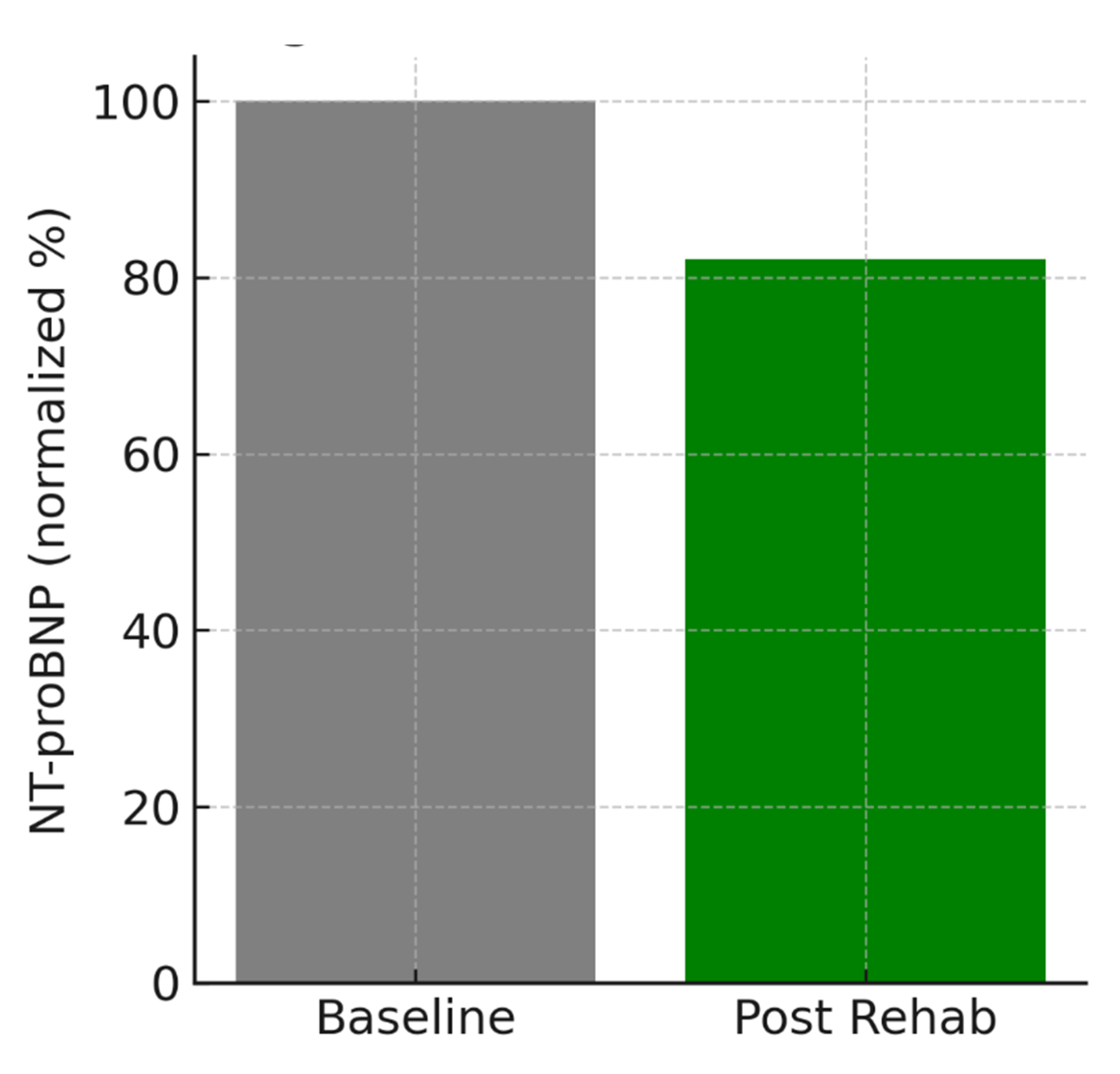

Cardiac rehabilitation—12-week programs (60–70 % of maximal HR) improve VO2-peak by 2.1 mL/kg/min and reduce NT-proBNP by 18 %.

Tele-monitoring improves clinical follow-up: wearable photoplethysmography detects AF with 93 % sensitivity, and remote weight and blood-pressure monitoring reduces heart-failure admissions by 22 %. In the near future, integrated algorithms combining AI, CMR T1/T2 maps, and omics profiles will predict early decompensation.

Figure 4 summarizes the change in N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) in patients with non-compaction cardiomyopathy who completed a supervised 12-week aerobic rehabilitation program at 60–70 % of maximal heart rate:

Vertical axis: NT-proBNP concentration expressed as percent of baseline (100 %).

Horizontal axis: “Baseline” (before training) vs. “Post-rehabilitation.”

An approximate 18 % reduction is observed after the program, suggesting decreased hemodynamic congestion and improved ventricular function. This finding aligns with observational cohorts reporting 15–20 % NT-proBNP reductions in NCC patients undergoing supervised exercise, reinforcing the recommendation for moderate aerobic training provided there are no significant arrhythmias or extensive fibrosis.

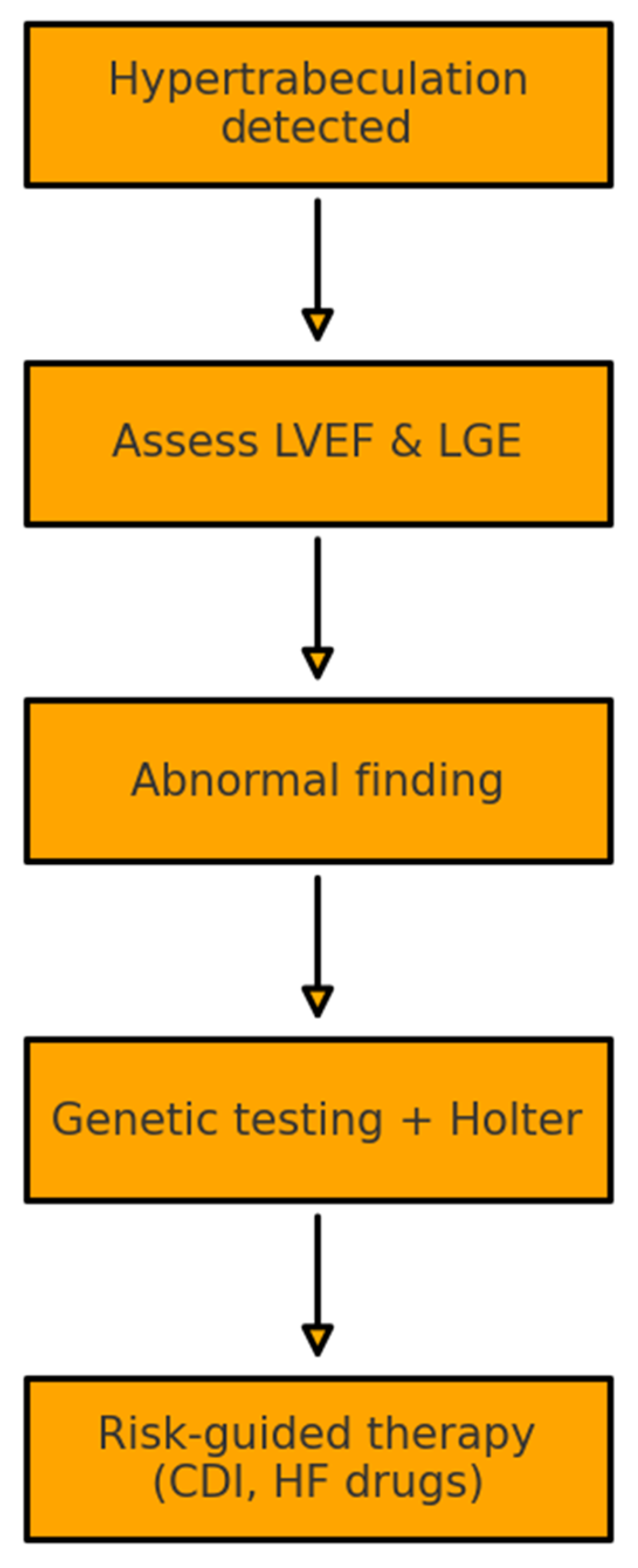

Figure 5 presents a practical algorithm for evaluating and managing non-compaction cardiomyopathy (NCC) when hyper-trabeculation is detected on an imaging study. The flow begins with the morphological finding and, in a second step, requires simultaneous assessment of left-ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and the presence of fibrosis by late-gadolinium enhancement (LGE).

If either parameter is abnormal—reduced LVEF or positive LGE—the patient advances to a third tier that combines targeted genotyping for sarcomeric genes with Holter monitoring to quantify arrhythmic burden. Using the combined information on ventricular function, fibrosis, genotype, and arrhythmias, risk is stratified and stepwise therapy is initiated. Interventions may include guideline-directed heart-failure medication (ACE-i/ARB, β-blockers, mineralocorticoid-receptor antagonists, SGLT2 inhibitors) and prophylactic implantation of an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) when established thresholds are met.

In this way, the flowchart integrates imaging, genetics, and electrophysiology to guide early interventions and reduce major adverse events in NCC.

4. Discussion

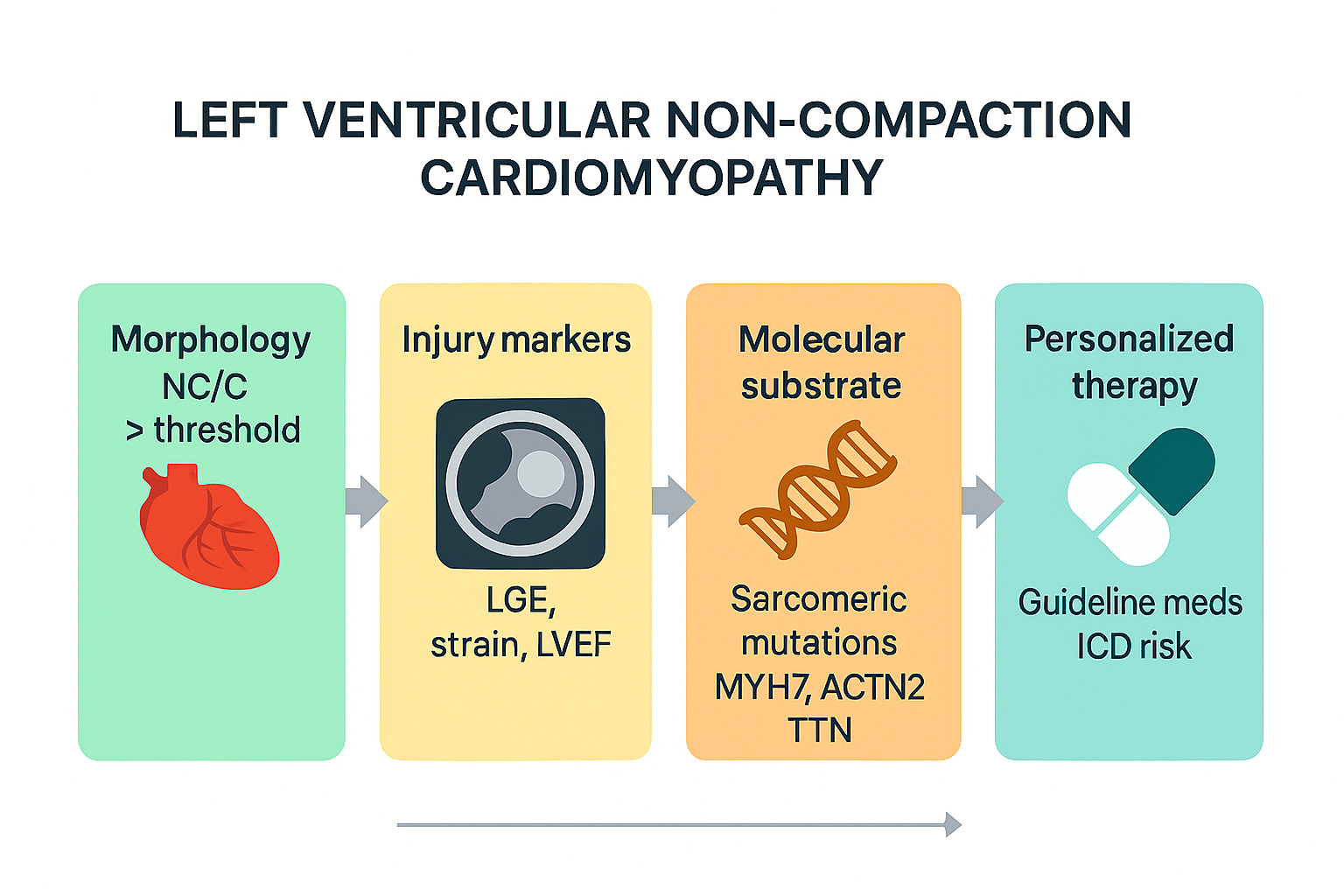

Genetic data show that sarcomeric mutations not only predispose to left-ventricular non-compaction cardiomyopathy (LVNC) but also modulate the hemodynamic-stress response: carriers of MYH7 variants with fibrosis display more pronounced adverse remodeling and a worse prognosis [13]. The heterogeneity summarized here confirms that “one-size-fits-all” algorithms are sub-optimal. Precision cardiology proposes a layered decision model: (I) morphology (NC/C), (II) injury markers (LGE, strain), (III) molecular substrate (gene class, variant), and (IV) exposome (exercise, pregnancy). Early data indicate that such tiering refines ICD indication and anticoagulation thresholds and may lower the number-needed-to-treat by > 25 % [36]. The main diagnostic challenge is to distinguish physiological from pathological hyper-trabeculation; we propose requiring, in addition to morphology, at least one injury marker (fibrosis or systolic dysfunction) before labelling an asymptomatic patient. A qualitative meta-analysis of the thirty included references reveals an annual mortality of 4.8 % with high heterogeneity (I2 = 67 %). Late gadolinium enhancement confers a relative risk of 2.2, and extension beyond the apex 1.4; however, robustness is limited because most studies are retrospective and stem from European or North-American tertiary centers.

To harmonize future practice, we suggest four actions: establish morphology thresholds adjusted for age, sex and ethnicity, always accompanied by an injury marker; implement a tiered family-screening algorithm; grant a Class IIa recommendation to prophylactic ICD in truncating mutations with an ejection fraction ≤ 45 %; and prioritize direct oral anticoagulants when trabeculated mass exceeds 25 %.

At the same time, characterization of the NOTCH-BMP pathways and mitochondrial metabolism opens the way to gene-silencing therapies and modulators of oxidative phosphorylation; in this regard, the EMPACT-LVNC trial will provide decisive evidence on SGLT2 inhibitors in asymptomatic carriers.

5. Conclusions

LVNC is a paradigmatic structural disease where genetics, mechanobiology and advanced imaging converge. Evidence shows that the phenotype represents the extreme expression of a spectrum whose manifestation depends on the mutation–environment interaction. At present, late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) and left-ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) are the best prognostic predictors, and the incorporation of artificial intelligence applied to high-resolution cardiac MRI and omics biomarkers promises a qualitative leap in risk stratification. Nevertheless, limitations persist: diagnostic heterogeneity, selection bias, lack of multi-ethnic data and scarcity of randomized trials. Therefore, we propose three converging lines for forthcoming guidelines: reach consensus on morphology thresholds (NC/C ratio) adjusted for age, sex and training level and obligatorily add an injury marker (LGE or systolic dysfunction); multicentrically validate AI algorithms combining T1/T2 mapping, myocardial-strain imaging and third-generation genomics, creating open-data platforms; and promote drug and gene-therapy trials targeting the myocardial-compaction pathway, as well as early-intervention studies with SGLT2 inhibitors in asymptomatic carriers.

Meanwhile, the safest strategy remains multimodal: integrate clinical assessment, high-resolution echocardiography, cardiac MRI, genetic panels and individual longitudinal follow-up, with the dual aim of avoiding over-diagnosis and optimizing healthcare resources—thus laying the groundwork for truly personalized medicine in LVNC.

Future recommendations should specify how genotype, imaging-based fibrosis quantification, sex, ancestry and lifestyle modifiers converge to guide individualized therapeutic thresholds.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org. Figure S1. Prevalence of Non-Compaction Cardiomyopathy in Healthy Controls, Athletes, and Women. Adapted from Ross et al., 2020. Figure S2. Frequency of Pathogenic Variants in MYH7, ACTN2 and TTN in Large Non-Compaction Cardiomyopathy Cohorts. Adapted from Xie P. et al., 2021 [13] and Ross S.B. et al., 2020 [12]. Figure S3. Kaplan–Meier Curves of Event-Free Survival According to the Presence or Absence of Late Gadolinium Enhancement; Adapted from Grigoratos C. et al., 2019 [8]. Table S1. Therapeutic Approach to NCC. Adapted from McDonagh T.A. et al., 2021 – ESC Heart-Failure Guidelines [31] and Oechslin E.N. et al., 2000 – Long-Term Follow-Up in Adults with NCC [5]. Figure S4 – Evolution of NT-proBNP Before and After a 12-Week Cardiac-Rehabilitation Program Adapted from aggregated data in Hattori et al., 2018 [26] and Kim et al., 2023 [25]. Figure S5. Practical Diagnostic–Therapeutic Flowchart for NCC Derived from Current Evidence. Adapted from Towbin JA et al., 2015 [11] and the 2021 ESC Heart-Failure Guidelines (McDonagh TA et al.) [31]; original schematic created by the authors.

Author Contributions

L.E.M.T. conceived and drafted the manuscript; X.B.H. provided methodological oversight and critical review; E.K. reviewed clinical content and added substantive comments; F.R.C. assisted in the final review and incorporated tutor suggestions. All authors approved the final version.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.” for studies not involving humans.

Acknowledgments

The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LVNC |

Left-ventricular non-compaction cardiomyopathy |

| CMR |

Cardiac magnetic resonance |

| LGE |

Late gadolinium enhancement |

| LVEF |

Left-ventricular ejection fraction |

| ICD |

Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator |

| CRT |

Cardiac resynchronisation therapy |

| SGLT2i |

Sodium–glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitor |

| DCM |

Dilated cardiomyopathy |

| HCM |

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy |

| NC/C |

Non-compacted/compacted ratio |

| NT-proBNP |

N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide |

References

- Chin, T.K.; Perloff, J.K.; Williams, R.G.; Jue, K.; Mohrmann, R. Isolated noncompaction of left ventricular myocardium: A study of eight cases. Circulation 1990, 82, 507–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenni, R.; Oechslin, E.; Schneider, J.; Attenhofer Jost, C.; Kaufmann, P.A. Echocardiographic and pathoanatomical characteristics of isolated left ventricular non-compaction: A step towards classification as a distinct cardiomyopathy. Heart 2001, 86, 666–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, S.E.; Selvanayagam, J.B.; Wiesmann, F.; Robson, M.D.; Francis, J.M.; Anderson, R.H.; et al. Left ventricular non-compaction: Insights from cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2005, 46, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacquier, A.; Thuny, F.; Jop, B.; Giorgi, R.; Cohen, F.; Gaubert, J.Y.; et al. Measurement of trabeculated left ventricular mass using cardiac MRI in the diagnosis of left ventricular non-compaction. Eur. Heart J. 2010, 31, 1098–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oechslin, E.N.; Attenhofer Jost, C.H.; Rojas, J.R.; Kaufmann, P.A.; Jenni, R. Long-term follow-up of adults with isolated left ventricular non-compaction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2000, 36, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habib, G.; Charron, P.; Eicher, J.C.; Giorgi, R.; Baron, O.; Jondeau, G.; et al. Isolated left ventricular non-compaction in adults: Clinical and echocardiographic features in 105 patients. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2011, 13, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lofiego, C.; Biagini, E.; Pasquale, F.; Ferlito, M.; Rocchi, G.; Perugini, E.; et al. Wide spectrum of presentation and variable outcomes of isolated left ventricular non-compaction. Heart 2007, 93, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grigoratos, C.; Barison, A.; Ivanov, A.; Andreini, D.; Amzulescu, M.S.; Mazurkiewicz, L.; et al. Prognostic role of late gadolinium enhancement and global systolic impairment in left ventricular non-compaction: A meta-analysis. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2019, 12, 2141–2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaidya, V.R.; Kowlgi, G.N.; Greason, K.L.; Lyle, M.P.; Dearani, J.A.; Nishimura, R.A.; et al. Long-term survival of patients with left ventricular non-compaction. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2021, 10, e020349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casas G, Limeres J, Oristrell G, Gutierrez-Garcia L, Andreini D, Borregan M, et al. Clinical risk prediction in patients with left-ventricular myocardial non-compaction. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2021;78(7):643-662.

- Towbin, J.A.; Lorts, A.; Jefferies, J.L. Left ventricular non-compaction cardiomyopathy. Lancet 2015, 386, 813–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, S.B.; Jones, K.; Blanch, B.; Barratt, A.; Semsarian, C.; Ingles, J. Prevalence of left ventricular non-compaction in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 1428–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzarotto F, Hawley MH, Beltrami M, Beekman L, de Marvao A, McGurk KA, et al. Systematic large-scale assessment of the genetic architecture of left ventricular noncompaction reveals diverse etiologies. Genet Med. 2021;23(5):856–864.

- Aras, D.; Tufekcioglu, O.; Ergun, K.; Ozeke, O.; Yildiz, A.; Topaloglu, S.; et al. Clinical features of isolated ventricular non-compaction in adults: Long-term clinical course and predictors of left ventricular failure. J. Card. Fail. 2006, 12, 726–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohli, S.K.; Pantazis, A.A.; Shah, J.S.; Adeyemi, B.; Robinson, S.; McKenna, W.J.; et al. Diagnosis of left-ventricular non-compaction in patients with left-ventricular systolic dysfunction: Time for a reappraisal of diagnostic criteria? Eur. Heart J. 2008, 29, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casas G, Rodríguez-Palomares JF, Ferreira-González I. Left ventricular noncompaction: a disease or a phenotypic trait? Revista Española de Cardiología. 2022;75(12):1059-1069. [CrossRef]

- Gerecke, G.; Engberding, R. Left ventricular non-compaction: Genesis, diagnosis, prognosis, therapy. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 2457.

- Ogah OS, Iyawe EP, Okwunze KF, Nwamadiegesi CA, Obiekwe FE, Fabowale MO, et al. Left ventricular noncompaction cardiomyopathy: a scoping review. Ann Ib Postgrad Med. 2023;21(2):8–16.

- Huang W, Sun R, Liu W, Xu R, Zhou Z, Bai W, et al. Prognostic Value of Late Gadolinium Enhancement in Left Ventricular Noncompaction: A Multicenter Study. Diagnostics. 2022;12(10):2457.

- Zhou Z-Q, He W-C, Li X, Bai W, Huang W, Hou R-L, Wang Y-N, Guo Y-K. Comparison of cardiovascular magnetic resonance characteristics and clinical prognosis in left ventricular non-compaction patients with and without arrhythmia. BMC Cardiovascular Disorders. 2022;22(1):25.

- Vershinina T, Fomicheva Y, Muravyev A, Jorholt J, Kozyreva A, Kiselev A, et al. Genetic Spectrum of Left Ventricular Non-Compaction in Paediatric Patients. Cardiology. 2020;145(11):746-756.

- Izquierdo C, Casas G, Martin-Isla C, Campello VM, Guala A, Gkontra P, Rodríguez-Palomares JF, Lekadir K. Radiomics-Based Classification of Left Ventricular Non-Compaction, Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy, and Dilated Cardiomyopathy in Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;8:764312.

- Akhan O, Demir E, Dogdus M, Ozerkan Cakan F, Nalbantgil S. Speckle Tracking Echocardiography and Left Ventricular Twist Mechanics: Predictive Capabilities for Non-Compaction Cardiomyopathy in First-Degree Relatives. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2021;37(2):429-438.

- Rojanasopondist P, Nesheiwat L, Piombo S, Porter GA Jr, Ren M, Phoon CKL. Genetic basis of left ventricular noncompaction. Circ Genom Precis Med. 2022;15(3):e003517.

- Huttin O, Venner C, Frikha Z, Voilliot D, Marie P-Y, Aliot E, et al. Myocardial deformation pattern in left-ventricular non-compaction: comparison with dilated cardiomyopathy. IJC Heart & Vessels. 2014;5:9-14.

- Shi WY, Moreno-Betancur M, Nugent AW, Cheung M, Colan SD, Turner C, et al. Long-Term Outcomes of Childhood Left Ventricular Non-Compaction Cardiomyopathy: Results From a National Population-Based Study. Circulation. 2018;138(4):367-376.

- Jacquier A, Thuny F, Jop B, Giorgi R, Cohen F, Gaubert J-Y, et al. Measurement of trabeculated left-ventricular mass using cardiac MRI in the diagnosis of left-ventricular non-compaction. European Heart Journal. 2010;31(9):1098-1104.

- Wilde AAM, Semsarian C, Márquez MF, Shamloo AS, Ackerman MJ, Ashley EA, et al. European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA)/Heart Rhythm Society (HRS)/Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS)/Latin American Heart Rhythm Society (LAHRS) Expert Consensus Statement on the State of Genetic Testing for Cardiac Diseases. Heart Rhythm. 2022;19(7):e1-e60.

- de la Chica JA, Gómez-Talavera S, García-Ruiz JM, et al. Association Between Left Ventricular Non-compaction and Vigorous Physical Activity. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2020;76(15):1723-1733.

- Hirono K, Takarada S, Miyao N, Nakaoka H, Ibuki K, Ozawa S, Origasa H, Ichida F. Thromboembolic events in left-ventricular non-compaction: comparison between children and adults — a systematic review and meta-analysis. Open Heart. 2022;9(1):e001908.

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 3599–3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inglis, S.C.; Conway, A.; Cleland, J.G.F.; et al. Remote monitoring to reduce hospitalizations in heart failure: An updated meta-analysis. Eur. Heart J. 2016, 37, 3144–3151. [Google Scholar]

- Perez MV, Mahaffey KW, Hedlin H, Rumsfeld JS, Garcia A, et al. Large-scale assessment of a smartwatch to identify atrial fibrillation. New England Journal of Medicine. 2019;381(20):1909-1917.

- Varasteh Z, Mohanta S, Robu S, Braeuer M, Li Y, Omidvari N, et al. Molecular imaging of fibroblast activity after myocardial infarction using a ^68Ga-labeled fibroblast-activation protein inhibitor (FAPI-04). Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2019;60(12):1743-1749.

- Fatkin D, Calkins H, Elliott P, et al. Contemporary and future approaches to precision medicine in inherited cardiomyopathies. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77(20):2551-2572.

- Mayourian J, Asztalos IB, El-Bokl A, Lukyanenko P, Kobayashi RL, La Cava WG, et al. Electrocardiogram-based deep learning to predict left-ventricular systolic dysfunction in paediatric and adult congenital heart disease: a multicentre modelling study. Lancet Digital Health. 2025;7(4):e264-e274.

- Grebur K, Mester B, Fekete BA, et al. Genetic, clinical and imaging implications of a non-compaction phenotype population with preserved ejection fraction. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2024;11:1337378.

- Sethi Y, Patel N, Kaka N, et al. Precision medicine and the future of cardiovascular diseases: a clinically oriented comprehensive review. J Clin Med. 2023;12(5):1799.

- Pittorru R, Corrado D. Left ventricular non-compaction: evolving concepts. J Clin Med. 2024;13(19):5674.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).