3.1. Identifying Medulloblastoma Patients Eligible for Targeted Therapies

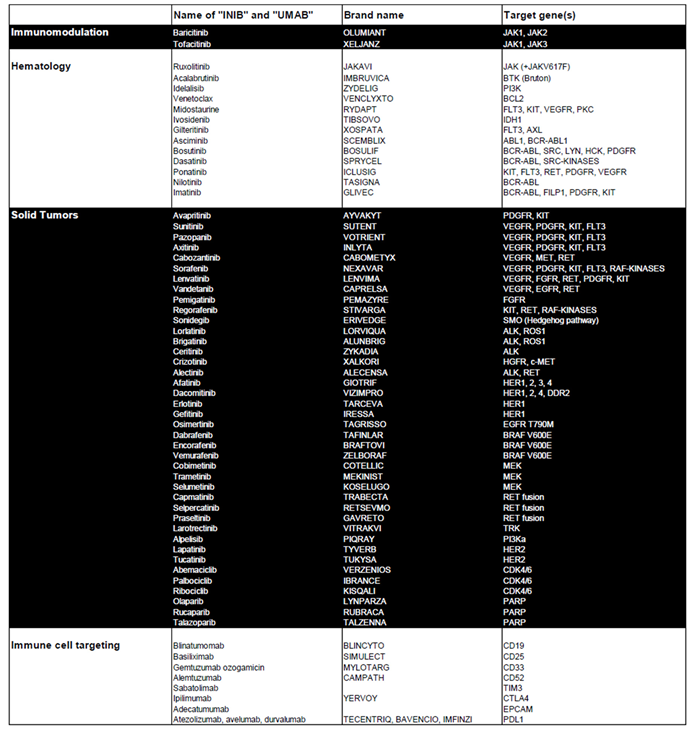

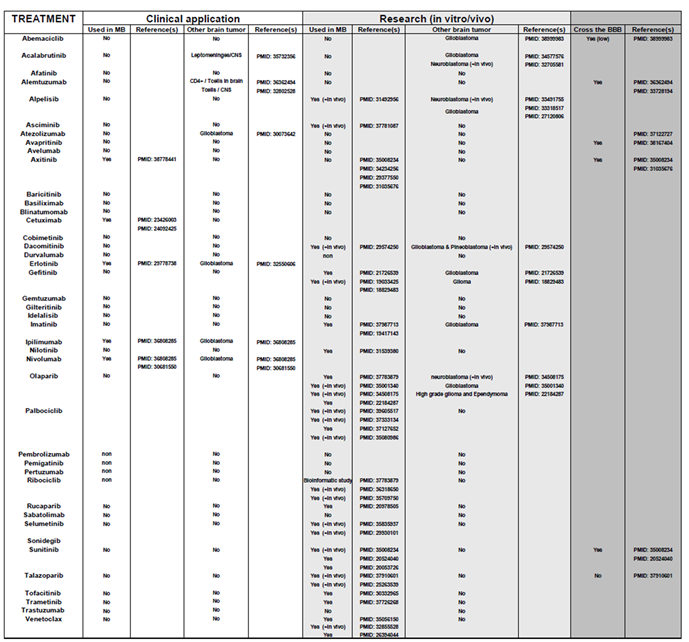

Table 1 highlights kinase and apoptosis inhibitors that target specific genes in tumor cells and are used in the treatment of both hematological and solid tumors. It also includes immunological modulators that act on specific targets expressed by transformed immune cells or on pathways involved in immune tolerance. Our aim was to explore the potential of repositioning these clinically validated therapies for the treatment of pediatric medulloblastoma.

To validate their relevance, we analyzed the relationship between these genes and overall patient survival (OS) using the Cavalli et al. cohort, the only publicly available dataset with survival data [

12]. For each gene associated with a targeted therapy, Kaplan-Meier survival curves were generated via the R2 platform, employing the optimal cutoff values. Initially, Kaplan-Meier survival curves were generated for each gene, accompanied by their respective raw P-values and Bonferroni-corrected P-values. Approximately 300 curves were produced, which are presented in

Supplementary Figure S1. Based on this analysis,

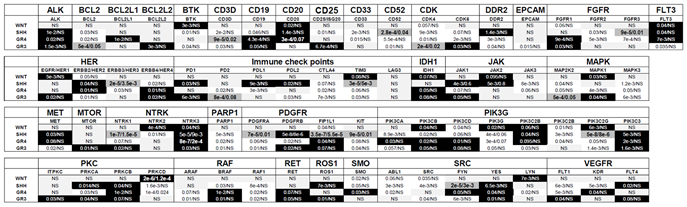

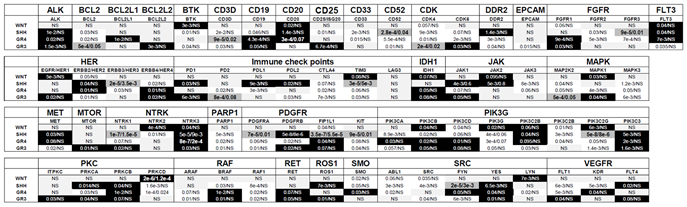

Table 2 summarizes the raw and Bonferroni-corrected P-values for each gene across the molecular subgroups of medulloblastoma (WNT, SHH, Group 3, and Group 4).

From

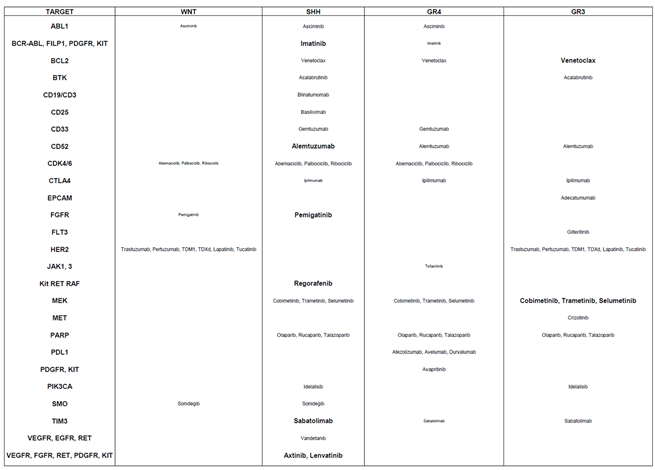

Table 2, several genes were identified as relevant therapeutic targets due to their overexpression being associated with shorter OS. The corresponding treatments are outlined in

Table 3. Genes with statistically significant associations (raw and Bonferroni-corrected P-values < 0.05) were prioritized for potential efficacy of targeted therapy within specific genetic subgroups:

SHH subgroup: Relevant targets included BCR-ABL, FILP1, PDGFR, Kit, CD52, FGFR, RET, RAF, TIM3, and VEGFR, with corresponding treatments Imatinib, Alemtuzumab, Pemigatinib, Regorafenib, Sabatolimab, Axitinib and Lenvatinib.

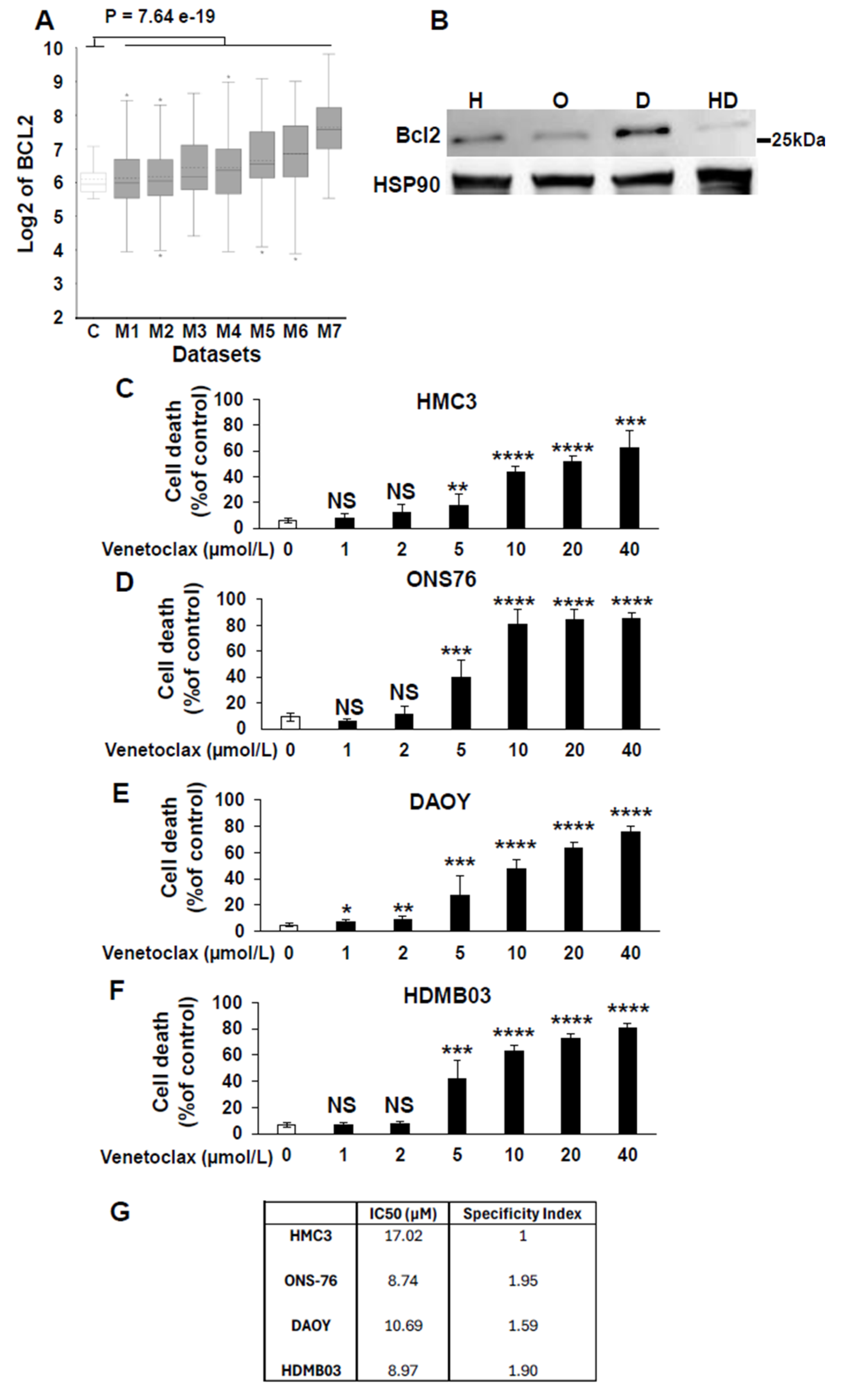

Group 3 tumors: Key genes identified were BCL2 and MEK2, with potential treatments Venetoclax and MEK inhibitors such as Cobimetinib, Trametinib, or Selumetinib.

WNT subgroup: Targetable genes included ABL1, CDK4/6, FGFR, HER2, and SMO, with suggested therapies such as Asciminib, Abemaciclib, Palbociclib, Ribociclib, Pemigatinib, Trastuzumab, Pertuzumab, T-DM1, T-DXd, Lapatinib, Tucatinib, and Sonidegib.

Table 1.

Overview of Approved Targeted Therapies for Solid and Hematologic Tumors. This table provides a detailed summary of targeted therapies currently approved for the treatment of solid and hematologic tumors. It includes the associated pathologies, the generic names of the treatments, their corresponding brand names, and the specific genes they target.

Table 1.

Overview of Approved Targeted Therapies for Solid and Hematologic Tumors. This table provides a detailed summary of targeted therapies currently approved for the treatment of solid and hematologic tumors. It includes the associated pathologies, the generic names of the treatments, their corresponding brand names, and the specific genes they target.

Group 4 tumors: Although no targets were highly statistically significant, several potential candidates were identified, including ABL1 (Asciminib), BCR-ABL, FILP1, PDGFR, Kit (Imatinib), BCL2 (Venetoclax), CD33 (Gemtuzumab), CD52 (Alemtuzumab), CDK4/6 (Abemaciclib, Palbociclib, Ribociclib), CTLA4 (Ipilimumab), JAK1/3 (Tofacitinib), MEK (Cobimetinib, Trametinib, Selumetinib), PARP (Olaparib, Rucaparib, Talazoparib), PDL1 (Atezolizumab, Avelumab, Durvalumab), PDGFR/KIT (Avapritinib), and TIM3 (Sabatolimab).

This classification provides a framework for repositioning specific drugs to treat pediatric medulloblastoma, offering novel therapeutic opportunities tailored to the genetic profiles of the tumor subgroups.

Table 2.

Association Between Targeted Genes and Patient Survival Across Medulloblastoma Subgroups. This table illustrates the relationship between genes targeted by the therapies listed in

Table 1 and overall survival (OS) across various genetic subgroups of medulloblastoma. The analyzed genes or gene families are displayed alongside their respective P-values, calculated using the R2 platform with the optimal cutoff method. Two P-values are provided for each gene: the first represents the raw significance, while the second reflects the Bonferroni-corrected significance. Genes are visually categorized based on their prognostic association using background colors:

White background: Genes linked to shorter OS;

Black background: Genes linked to longer OS;

Dark grey background with enlarged text: Genes associated with a poor prognosis, indicated by both raw and Bonferroni-corrected P-values < 0.05;

Light grey background: Non-significant (NS) genes with no clear survival impact. This classification provides an intuitive visual summary of the survival impact of specific genes across medulloblastoma subgroups, facilitating a better understanding of their prognostic relevance.

Table 2.

Association Between Targeted Genes and Patient Survival Across Medulloblastoma Subgroups. This table illustrates the relationship between genes targeted by the therapies listed in

Table 1 and overall survival (OS) across various genetic subgroups of medulloblastoma. The analyzed genes or gene families are displayed alongside their respective P-values, calculated using the R2 platform with the optimal cutoff method. Two P-values are provided for each gene: the first represents the raw significance, while the second reflects the Bonferroni-corrected significance. Genes are visually categorized based on their prognostic association using background colors:

White background: Genes linked to shorter OS;

Black background: Genes linked to longer OS;

Dark grey background with enlarged text: Genes associated with a poor prognosis, indicated by both raw and Bonferroni-corrected P-values < 0.05;

Light grey background: Non-significant (NS) genes with no clear survival impact. This classification provides an intuitive visual summary of the survival impact of specific genes across medulloblastoma subgroups, facilitating a better understanding of their prognostic relevance.

|

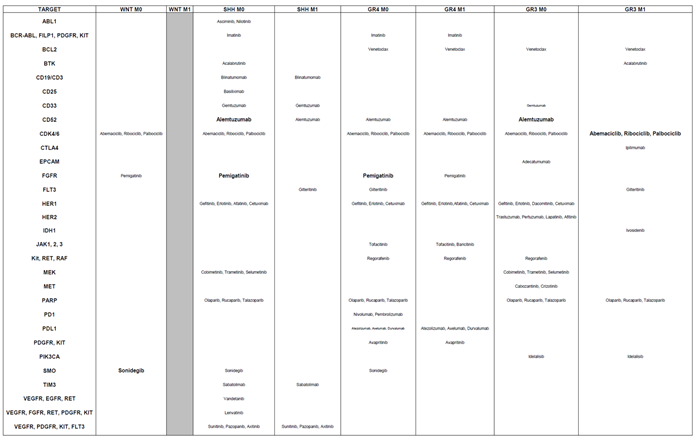

Table 3.

Alignment of Targeted Therapies with Gene-Survival Associations Across Medulloblastoma Subgroups. This table outlines the positioning of targeted therapies based on the survival impact of their corresponding genes across medulloblastoma subgroups. It highlights the most suitable treatments for each subgroup, determined by the lowest P-value: Small characters: Indicate a trend toward significance. Medium characters: Denote a statistically significant raw P-value. Large characters: Represent both raw and Bonferroni-corrected P-values as statistically significant. This table aids in identifying the most effective targeted therapies for each medulloblastoma subgroup, guided by gene-survival correlations.

Table 3.

Alignment of Targeted Therapies with Gene-Survival Associations Across Medulloblastoma Subgroups. This table outlines the positioning of targeted therapies based on the survival impact of their corresponding genes across medulloblastoma subgroups. It highlights the most suitable treatments for each subgroup, determined by the lowest P-value: Small characters: Indicate a trend toward significance. Medium characters: Denote a statistically significant raw P-value. Large characters: Represent both raw and Bonferroni-corrected P-values as statistically significant. This table aids in identifying the most effective targeted therapies for each medulloblastoma subgroup, guided by gene-survival correlations.

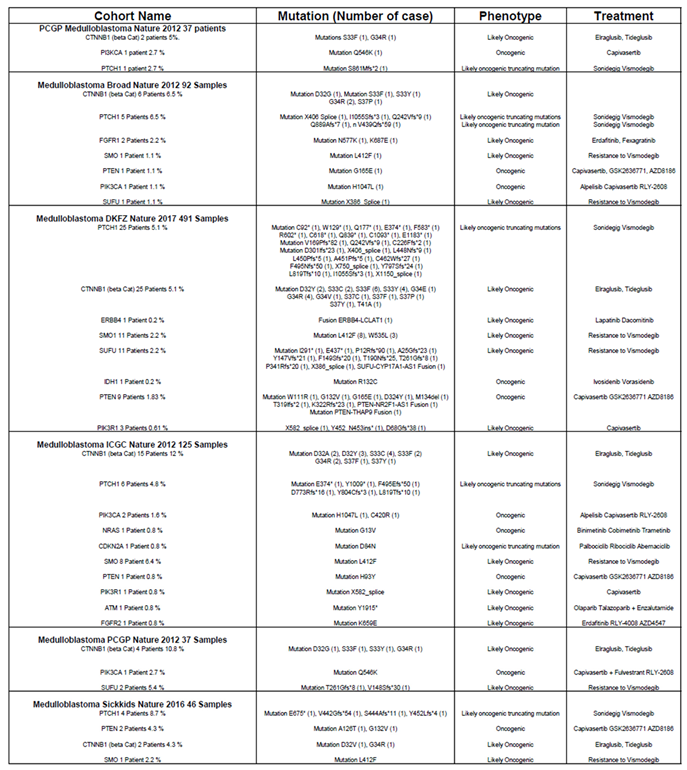

3.2. Stratification of Patients by Metastatic Status

Our previous research on gene expressions associated with kidney cancer and medulloblastoma aggressiveness revealed a potential reversal in the impact on OS depending on metastatic status (non-metastatic, M0, versus metastatic, M1). Notably, the prognostic significance of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor C (VEGFC), a key gene in lymphatic vessel development, displayed opposing trends in M0 and M1 contexts [

24,

25]. Therefore, we reiterate our analysis considering this important parameter. Approximately 700 curves were produced, which are presented in

Supplementary Figure S2. Based on this analysis,

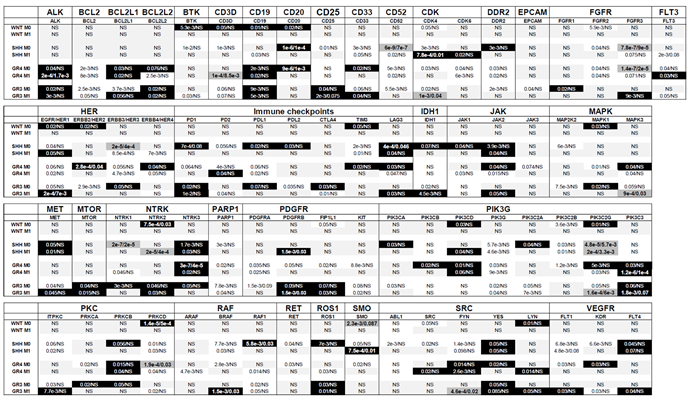

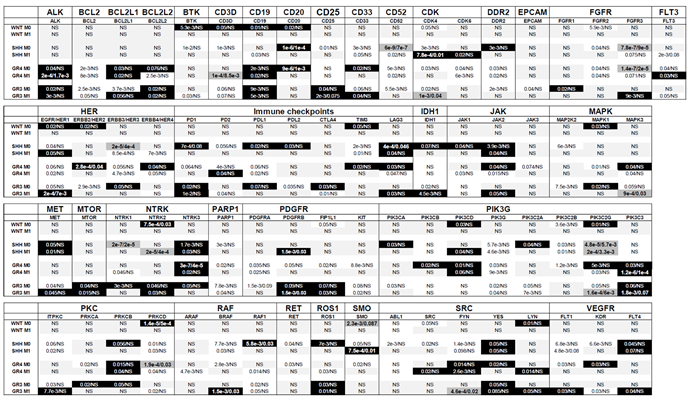

Table 4 summarizes the raw and Bonferroni-corrected P-values for each gene across the molecular subgroups of medulloblastoma and the metastatic status, M0/M1 (WNT, SHH, Group 3, and Group 4).

Table 4.

Association Between Targeted Genes and Patient Survival Across Medulloblastoma Subgroups Considering Metastatic Status (M0, M1). This table explores the association of genes targeted by the therapies listed in

Table 1 with overall survival (OS) in medulloblastoma patients, stratified by metastatic status (M0: non-metastatic, M1: metastatic). The analyzed genes or gene families are presented alongside their respective P-values, calculated using the R2 platform based on the optimal cutoff approach. Two P-values are reported for each gene: the raw significance value and the Bonferroni-corrected significance value. Genes are visually categorized using background colors to reflect their prognostic impact: White background: Genes associated with shorter OS; Black background: Genes associated with longer OS; Dark grey background with enlarged text: Genes associated with a poor prognosis, indicated by both raw and Bonferroni-corrected P-values < 0.05; Light grey background: Non-significant (NS) genes with no discernible impact on OS. This visual classification highlights the survival implications of specific genes across medulloblastoma subgroups while considering the patients’ metastatic status, providing valuable insights into prognostic and therapeutic considerations.

Table 4.

Association Between Targeted Genes and Patient Survival Across Medulloblastoma Subgroups Considering Metastatic Status (M0, M1). This table explores the association of genes targeted by the therapies listed in

Table 1 with overall survival (OS) in medulloblastoma patients, stratified by metastatic status (M0: non-metastatic, M1: metastatic). The analyzed genes or gene families are presented alongside their respective P-values, calculated using the R2 platform based on the optimal cutoff approach. Two P-values are reported for each gene: the raw significance value and the Bonferroni-corrected significance value. Genes are visually categorized using background colors to reflect their prognostic impact: White background: Genes associated with shorter OS; Black background: Genes associated with longer OS; Dark grey background with enlarged text: Genes associated with a poor prognosis, indicated by both raw and Bonferroni-corrected P-values < 0.05; Light grey background: Non-significant (NS) genes with no discernible impact on OS. This visual classification highlights the survival implications of specific genes across medulloblastoma subgroups while considering the patients’ metastatic status, providing valuable insights into prognostic and therapeutic considerations.

|

From

Table 4, several genes emerged as relevant therapeutic targets, but their prognostic significance for OS varied depending on metastatic status. For example,

BCL2L1 was associated with poor prognosis in non-metastatic (M0) Group 3 patients but exhibited a favorable prognosis in metastatic (M1) Group 3 patients. Similarly, genes such as

CDK4,

HER1, and

SMO showed differing prognostic roles between M0 and M1 patients in the SHH subgroup, while

HER1,

MET, and

ITPKC displayed similar contrasting behavior in Group 3 patients. Additionally,

FLT3 and

PD2 were poor prognostic markers for Group 4 M0 patients but indicated good prognosis in Group 4 M1 patients.

Conversely, certain genes exhibited reversed prognostic associations between M0 and M1 stages. For example, BCL2L2, HER4, LAG3, JAK2, and MAPK3 were linked to favorable prognosis in M0 Group 4 patients but poor prognosis in M1 Group 4 patients. Similarly, CTLA4 was a favorable prognostic marker in M0 Group 3 patients but indicated poor prognosis in M1 Group 3 patients.

These results highlight that the prognostic behavior of certain genes depends significantly on tumor stage, reinforcing the importance of metastatic status in defining their clinical relevance. However, most genes demonstrate consistent prognostic behavior across both stages.

Genes associated with good prognosis were identified as being more significant in different patient groups based on metastatic status. In M0 patients, the genes BTK, CD3D, CD19, CD20, CD33, DDR2, FGFR1, HER1, HER2, HER3, HER4, PD1, PDL1, PDL2, TIM3, LAG3, IDH1, JAK1, JAK2, MAPK1, NTRK1, NTRK3, PIK3CA, PIK3CD, PIK3C2A, PIK3C2G, PRKCB, PRKCD, RAF1, ROS1, LYN, KDR, and FLT4 demonstrated greater significance. Meanwhile, in M1 patients, genes such as CD19, CD25, CDK6, FGFR3, PD1, MET, MTOR, NTRK2, PDGFRB, FIP1L1, PIK3C3, BRAF, ROS1, FYN, LYN, and FLT4 were identified as more significant.

Conversely, genes associated with poor prognosis also showed variation in significance based on metastatic status. In M0 patients, the genes BCL2, BTK, CD3D, CD25, CD33, CD52, CDK4, DDR2, EPCAM, FGFR2, FGFR3, HER3, PD1, PD2, PDL2, TIM3, JAK3, MAP2K2, MAPK1, NTRK1, PARP1, PDGFRA, PDGFRB, FIP1L1, KIT, PIK3G, PIK3C2B, PRKCA, PRKCD, BRAF, RAF1, RET, SMO, ABL1, SRC, FYN, and KDR were more significant. In contrast, in M1 patients, the genes BTK, CD3D, CD19, CDK4, CDK6, DDR2, FLT3, HER1, HER4, PD2, PDL1, JAK1, MAPK3, NTRK1, NTRK2, PDGFRA, KIT, PIK3G, PIK3C2A, PIK3C2B, PIK3C2G, ITPKC, PRKCD, ARAF, RAF1, ROS1, FYN, FLT1, and KDR showed higher significance.

These findings underscore the critical role of metastatic status in determining the prognostic significance and therapeutic prioritization of target genes. This distinction is vital for guiding gene-specific treatment strategies and optimizing therapeutic outcomes in medulloblastoma.

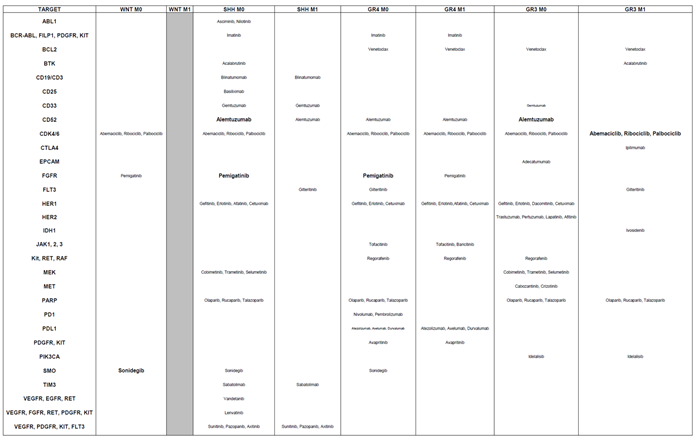

Through the deconvolution of genes associated with aggressiveness, we identified targeted therapies tailored to each genetic subgroup and their corresponding metastatic status (

Table 5).

This updated table incorporates considerations for both genetic subgroups and tumor stages, in contrast to the previous table, which focused solely on genetic subgroups without accounting for tumor metastatic status. For the WNT subgroup, several therapies showed promise for M0 patients, who represented most of the cohort. These included Abemaciclib, Ribociclib, and Palbociclib (CDK inhibitors), Pemigaptinib (FGFR inhibitor), and, unexpectedly, Sonidegib (SMO inhibitor), which was originally designed for SHH patients. However, targeting HER2 was not beneficial for M0 patients in this subgroup.

In the SHH subgroup, Venetoclax (BCL2 inhibitor), Ipilimumab (CTLA4 checkpoint inhibitor), and Alpelisib (PIK3CA inhibitor) were found to be irrelevant for both M0 and M1 patients. Conversely, therapies such as Gilteritinib (FLT3 inhibitor), Sunitinib, Pazopanib, and Axitinib (targeting VEGFR, PDGFR, KIT, and FLT3) demonstrated potential greater effectiveness.

For Group 4, therapies such as Asciminib (ABL1 inhibitor), Gemtuzumab (CD33-directed agent), Ipilimumab (CTLA4 inhibitor), and Cobimetinib, Trametinib, and Selumetinib (MAP2K2 inhibitors), and Sabatolimab (TIM3), were no longer relevant for either M0 or M1 patients. However, potential treatments included Gilteritinib (FLT3 inhibitor), Gefitinib, Erlotinib, Afatinib, and Cetuximab (EGFR-targeting agents), as well as Regorafenib (targeting KIT, RET, and RAF), Nivolumab and Pembrolizumab (PD1 inhibitors), and Idelalisib (PIK3CA inhibitor).

For Group 3, Sabatolimab (TIM3) was suspected to have no effect for both M0 and M1 patients. In contrast, promising drugs included Abemaciclib, Ribociclib, and Palbociclib (CDK inhibitors), Gefitinib, Erlotinib, Dacomitinib, and Cetuximab (EGFR-targeting), along with Ivosidenib (IDH1 inhibitor), Regorafenib (targeting KIT, RET, and RAF), and Cabozantinib (targeting VEGFR, MET, and RET).These findings underscore the importance of considering differences in tumor stages—localized (M0) versus metastatic (M1)—when repositioning treatments. The choice of therapy should be informed by these distinctions, particularly at diagnosis, relapse, or based on whether the tumor is localized or has spread.

Table 5.

Alignment of Targeted Therapies with Gene-Survival Associations Across Medulloblastoma Subgroups Considering M0 and M1 Status. This table aligns targeted therapies with the survival impact of their corresponding genes across medulloblastoma subgroups, considering the metastatic status (M0: non-metastatic; M1: metastatic). The therapies are categorized based on the statistical significance of the association between the targeted gene and overall survival (OS), as determined by the lowest P-value. The significance levels are represented using text size: Small characters: Indicate a trend toward significance (suggestive but not statistically confirmed); Medium characters: Denote a statistically significant association based on raw P-values; Large characters: Represent statistically significant associations confirmed by both raw and Bonferroni-corrected P-values. This framework identifies the most promising therapies for each subgroup, offering a nuanced understanding of therapeutic relevance in the context of metastatic status and gene-survival dynamics.

Table 5.

Alignment of Targeted Therapies with Gene-Survival Associations Across Medulloblastoma Subgroups Considering M0 and M1 Status. This table aligns targeted therapies with the survival impact of their corresponding genes across medulloblastoma subgroups, considering the metastatic status (M0: non-metastatic; M1: metastatic). The therapies are categorized based on the statistical significance of the association between the targeted gene and overall survival (OS), as determined by the lowest P-value. The significance levels are represented using text size: Small characters: Indicate a trend toward significance (suggestive but not statistically confirmed); Medium characters: Denote a statistically significant association based on raw P-values; Large characters: Represent statistically significant associations confirmed by both raw and Bonferroni-corrected P-values. This framework identifies the most promising therapies for each subgroup, offering a nuanced understanding of therapeutic relevance in the context of metastatic status and gene-survival dynamics.

|