3. Results

In the context of accelerating digitalization and the increasing complexity of innovation in the financial sector, central banks are faced with the dual challenge of supporting technological progress while safeguarding financial stability and consumer protection. To respond to this dynamic, the National Bank of Romania (NBR) considered, as early as 2019, the strategic necessity of establishing a dedicated FinTech Innovation Hub. This initiative was aligned with the broader European trend of institutionalizing supervisory instruments aimed at monitoring and guiding innovation in the payment and financial services sectors.

Given the NBR’s statutory responsibilities, particularly those related to the oversight of payment service providers (including but not limited to credit institutions, payment institutions and electronic money institutions), the Innovation Hub was positioned under the coordination of the Oversight of financial market infrastructures and payments Department. The key objective was to offer a structured platform for dialogue with entities developing or deploying technological innovations in payment instruments, with a specific focus on areas such as strong customer authentication, secure communications, data protection, operational and ICT risk management, as well as continuity planning.

Engagement with market participants through the Innovation Hub enabled the NBR to assess the regulatory classification of new types of financial services and especially of payment services, understanding business models and identify associated risks and benefits. The increasing demand for such interaction reflected the growing number of FinTech entities exploring innovations such as artificial intelligence, data analytics and blockchain for the delivery of financial services. The implementation of the revised Payment Services Directive (PSD2) acted as a catalyst, prompting both incumbent and non-traditional actors to seek interpretive clarity on new regulatory obligations and opportunities.

The primary objectives of the FinTech Innovation Hub implemented by NBR are:

to support and encourage innovation in payments and payment instruments, for the benefit of both service users and providers;

to identify risks associated with technological developments and to provide supervisory feedback to help mitigate these risks;

to foster the safe and inclusive growth of the payments market in line with EU regulatory developments and international best practices.

To achieve these goals, the Innovation Hub provides tailored guidance to both regulated and unregulated entities intending to introduce novel or significantly enhanced financial products. While the Innovation Hub does not issue binding opinions or authorizations, it plays a crucial role in helping entities navigate applicable regulatory frameworks and prepare for potential licensing procedures, thereby contributing to market transparency and compliance-readiness.

The Innovation Hub also seeks to increase regulatory flexibility by identifying implementation barriers and knowledge gaps, thus facilitating a more informed and proportionate regulatory stance. Importantly, the Innovation Hub serves as a monitoring mechanism for emerging risks, particularly in operational resilience and ICT security, and promotes the responsible adoption of innovation.

The Innovation Hub was also designed as a visible contact point, accessible through a dedicated section of the NBR website, offering resources such as guidance documents, summaries of relevant European initiatives and feedback channels for market participants.

Supervisory Methodology and Engagement Process

The NBR’s Innovation Hub operates on an open, continuous basis, without fixed deadlines for engagement, allowing for iterative assessment of ongoing developments. The methodology adopted comprises several sequential stages:

(a) submission of an “initial innovation form” through the web interface, containing essential information about the product/service, technology used and intended use cases;

(b) prioritization and screening by the Oversight Department, based on risk relevance and strategic potential;

(c) elaboration of a structured risk sheet and potential request for additional information;

(d) delivery of a reasoned, non-binding supervisory opinion regarding regulatory classification, potential authorization requirements and identified ICT/security risks.

Coordination with European institutions such as the EBA, the ECB, and the European Commission is considered essential in order to align supervisory interpretations and promote consistent regulatory practices across Member States.

The Role of the NBR’s FinTech Innovation Hub in Supporting Payment Innovation

In line with broader European efforts to promote safe and effective digital financial transformation, the National Bank of Romania (NBR) initiated the creation of a FinTech Innovation Hub (FIH) in 2019. This initiative was designed as a supervisory tool to monitor emerging technologies in the payment services ecosystem and to support the secure development of innovative financial solutions. The Hub serves as a national contact point for entities involved in developing new payment technologies and instruments, with the aim of identifying necessary regulatory or supervisory measures to ensure market safety, technological integrity and user trust.

FIHs have become a widespread supervisory instrument across the EU, with at least one such contact point established in every Member State, although regulatory sandboxes remain operational in only a limited number of jurisdictions [

2,

25]. Romania joined this collective European approach in September 2019, integrating its national efforts within the broader monitoring framework coordinated at EU level.

Through the Innovation Hub, the NBR continuously monitors the innovation environment in the payment domain, focusing on:

- -

identifying and assessing innovative solutions in payment services and instruments;

- -

evaluating ICT and cybersecurity risks and identifying appropriate mitigating measures;

- -

determining proportional and adequate supervisory tools to guide FinTech firms in aligning with regulatory expectations.

Between its inception and the end of 2023, the Innovation Hub received 68 applications from various entities proposing innovative business models, primarily in the field of payments. Based on the maturity and development potential of the proposals, the Oversight Department conducted bilateral consultations to support implementation. In many cases, collaboration with internal authorization departments was required, as the proposed services fell within the scope of regulated activities.

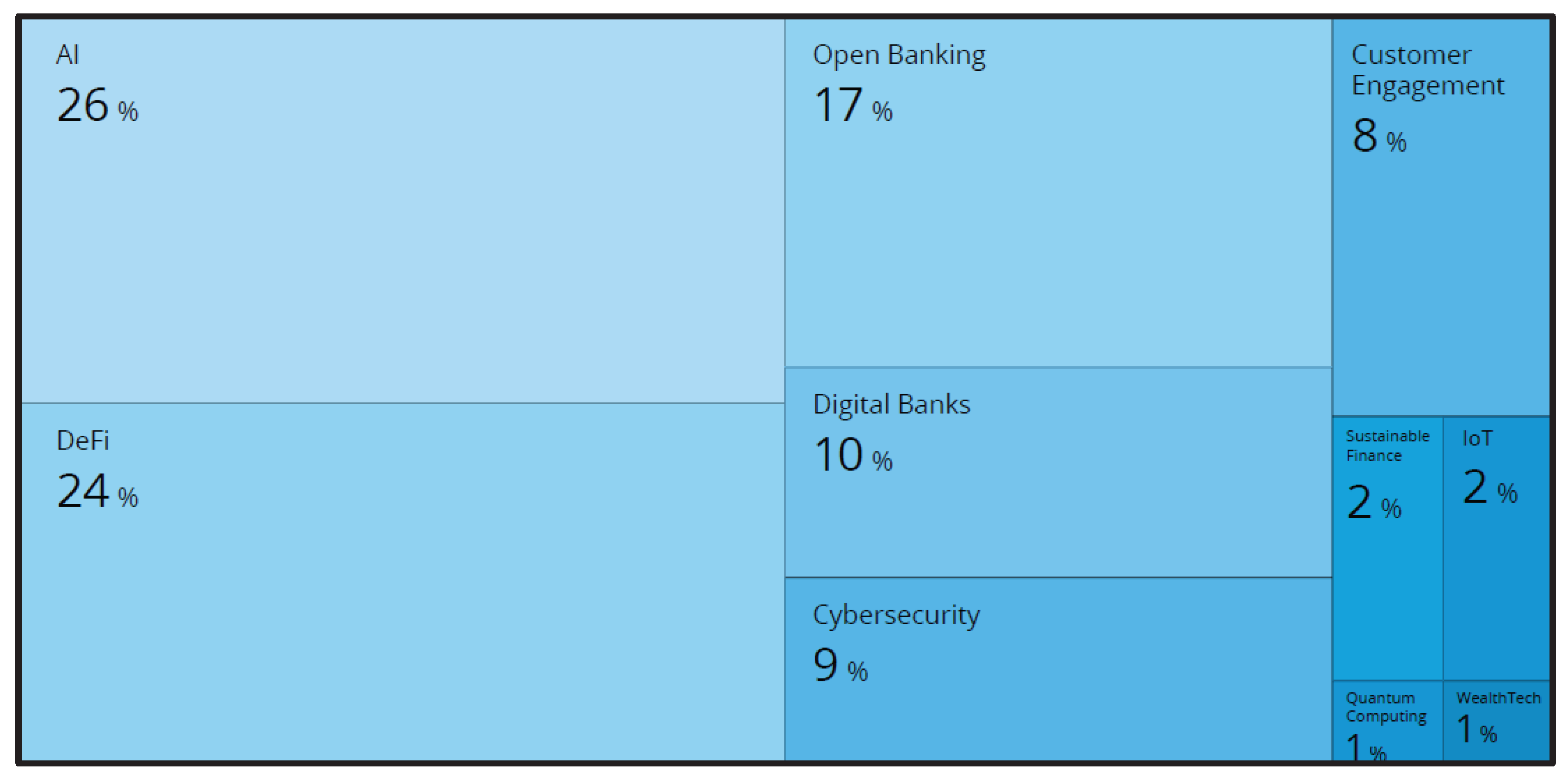

Between 2019 and 2023, the Innovation Hub registered 66 unique submissions, with the following distribution:

- -

31%: entities seeking authorization as payment service providers (PSPs), including those offering account information services (AIS) or payment initiation services (PIS) under PSD2 or issuing electronic money;

- -

42%: technology providers supporting payment service providers (PSPs) through digital services, with potential for future regulatory authorization;

- -

4%: firms proposing crowdfunding or crowdlending platforms, typically within the remit of the national capital markets supervisor (ASF);

- -

3%: RegTech solutions aiming to support compliance and regulatory reporting through technology-driven frameworks;

- -

6%: solutions exploring central bank digital currency (CBDC) models or related infrastructure.

approximately two-thirds (66%) of all applications focused directly on payment-related innovations, confirming the sector’s leading role in FinTech development. These initiatives mirror European trends, where payment services represent the most dynamic and rapidly evolving segment of financial innovation [

2,

3,

20,

21,

22]. All these data are summarized in

Table 1.

Analysis of the submissions revealed several structural barriers to market entry for FinTech’s, including the need for greater flexibility in the secondary regulatory framework and increased clarity on supervisory expectations regarding licensing procedures. Based on these findings, the NBR initiated a revision of its internal rules concerning the assessment of documentation submitted during formal authorization processes, with particular attention to the principle of proportionality and the nature of the services proposed.

Furthermore, the Innovation Hub experience served as a basis for launching a broader institutional reflection on additional innovation-monitoring tools, including the potential design of a Regulatory or Digital Sandbox. This reflection aims to better understand the challenges faced by the Romanian FinTech ecosystem and to support a more agile regulatory environment.

The establishment of the Innovation Hub by the National Bank of Romania has fulfilled a dual institutional role: as an interface between regulators and market innovators and as a channel for regulatory introspection. While its operational scope has remained advisory, the initiative has produced tangible institutional effects and revealed the structural characteristics of Romania’s evolving FinTech landscape.

The role and impact of the Romanian Innovation Hub has been as a:

One of the most visible effects of the Innovation Hub was the normalization of structured dialogue between authorities and non-bank innovators. In a jurisdiction where regulatory engagement had traditionally followed formal, document-based logic, the Hub introduced a more accessible, consultative model, without compromising legal consistency. This shift contributed to a reduced informational distance between supervisors and market actors.

Although the Innovation Hub did not issue formal opinions, its mere existence acted as a signaling mechanism indicating that the regulatory authority is willing to engage, listen and provide guidance (within defined limits). This reputational dimension is especially valuable in emerging markets where trust in regulatory and supervisory institutions may be unevenly distributed and access to interpretive clarity is often concentrated among incumbent actors (banks).

Another lesson learned relates to the function of the Hub as a low-risk instrument for institutional modernization. In contexts where sandbox legislation or binding pilot regimes may be legally or politically sensitive, innovation hubs offer a gradual, reversible and cost-effective entry point into innovation governance. The Romanian case illustrates how such platforms can generate internal coordination effects and market outreach without requiring structural legal reform.

In practice, the Innovation Hub helped clarify internal roles, encouraged risk-based thinking in frontier areas and offered regulators a vantage point from which to observe innovation trajectories without assuming regulatory allowance. Its non-intrusive nature preserved supervisory independence while still promoting an open posture toward innovation, a balance that proved valuable in the absence of more complex experimentation frameworks.

Despite its contributions, the Innovation Hub’s structural limitations must be acknowledged. Its nature limited public visibility and transparency related to the results, which may have reduced its reach among less connected or resource-constrained innovators. Additionally, the absence of direct policy feedback loops constrained its influence on long-term rulemaking.

Nevertheless, its implementation created institutional preconditions for future expansion, such as the development of the internal innovation analysis protocols, cross-functional training modules, which can support more ambitious frameworks in the future, such as structured sandboxes, cross-border pilot projects or DORA-compliant digital oversight modules.

While its main role was to be a facilitation tool for innovators in the private sector, the Romanian Innovation Hub also functioned as a mirror for supervisory capacity. The diversity of topics submitted, ranging from digital wallets and biometric authentication to cross-border open banking schemes, revealed areas where internal expertise required updating or deeper coordination across departments.

Through its consultative practice, the Innovation Hub provided early signals on emergent market practices, legal ambiguities and technological adoption patterns in the national market. This knowledge was subsequently leveraged to inform supervisory training sessions and to adjust guidance in certain domains (such as in the application of the principle of proportionality in digital business models). These outcomes confirm international observations that innovation facilitators can strengthen supervisory preparedness, not only enable compliance dialogue [

10,

19].

Lessons Learned and Emerging Challenges

Since its establishment in 2019, the Romanian Innovation Hub has confirmed a growing mismatch between the pace of technological development and the capacity of regulatory frameworks to absorb and respond to innovation. This so-called “pacing problem” is not unique to Romania but reflects a wider structural issue affecting supervisory institutions globally. Several factors contribute to this gap:

- -

the technical complexity of many new innovations makes rapid regulatory response difficult;

- -

the exponential growth potential of FinTech models creates challenges in monitoring and enforcement;

- -

the emergence of new business models and ecosystems raises novel questions regarding liability, data governance and systemic risks;

- -

the increasing cross-border nature of innovation complicates the delineation of regulatory competences and demands deeper EU coordination.

In our opinion there might be some interrelated reasons that could explain why regulatory authorities are struggling to keep pace with changes arising from these innovations. The first one we appreciate is the degree of technical complexity associated with several innovations in the sector and, secondly, the astonishing pace at which FinTech can grow. All these data are summarized in

Table 2.

Technology-driven innovation has been a constant feature of the financial sector for decades. At present, their pace and scope (potential applications of digital technologies spanning across areas such as payments and investment) is however leading to radical and far-reaching changes in traditional markets and thus several regulatory challenges. These challenges owe, among other phenomena, to the emergence of new business models, major impacts on competition and market efficiencies and implications for data security and privacy. Another significant challenge encountered by central banks in this context concerns the complexity of clearly attributing and distributing legal liability across actors involved in innovative financial ecosystems, coupled with the pressing need to prevent the escalation and systemic spread of fraudulent practices [

1,

4,

7,

27,

42,

43]. More generally, regulatory action needs to strike a balance between mitigating potential risks and enabling the development of innovations that can be beneficial for the economy and society as a whole.

We consider that, in this context of agile and intense developments of the FinTech innovation process there is also need for an innovative regulatory approach to support testing new technologies as an essential tool for central banks to better understand them. Regulatory sandboxes, for example, offer opportunities to implement and test disruptive technologies in a controlled regulatory environment while helping central banks to gain valuable insights to identify the right regulatory (or non-regulatory) approach.

Additional options worth exploring by the central banks include the need to develop new regulations that are outcome-oriented, allowing for the creation of testing spaces and innovation facilities and other related support mechanisms, as well as issuing specific guidelines. Furthermore, the rapid cross-border implications of Fintech innovations justify strengthening international and European regulatory cooperation and further developing anticipatory regulatory approaches.

From a central bank’s perspective, one of the most critical issues is balancing the need to protect financial stability and consumer interests, while avoiding the premature stifling of innovation. In this regard, the Innovation Hub has proven useful in identifying high-risk areas and guiding entities toward compliance, but further instruments may be required to test technologies in controlled environments.

One such tool is the regulatory sandbox, which allows authorities to observe real-world application of innovative models under limited, monitored conditions. This can yield valuable insights into the effectiveness of current regulations and inform the design of outcome-based rules. Beyond sandboxes, other approaches include the development of anticipatory regulatory strategies, soft-law instruments such as guidelines, and institutionalized cross-border collaboration frameworks [

8,

15].

We consider the main strategic challenges to be:

The increasing reliance on advanced digital infrastructures has significantly raised the stakes for central banks in terms of supervisory obligations. New technological paradigms, such as real-time payment systems, distributed ledger technologies (DLT), cloud-based architectures and the integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning (AI/ML) into financial risk models, are reshaping the systemic relevance of core infrastructures. While these innovations promise greater efficiency and accessibility, they also introduce heightened exposure to cyber threats, operational disruptions and critical third-party dependencies. In this environment, ensuring the operational resilience of payment and settlement systems becomes not only a technical requirement, but a strategic priority for safeguarding trust and systemic integrity.

The traditional boundaries of the supervisory authority are increasingly blurred by the emergence of novel business models operating across regulatory domains and geographical borders. Entities such as platform-based financial intermediaries or digital conglomerates frequently operate beyond the reach of sector-specific prudential regulation, even though their cumulative activity may pose risks to financial stability. This raises questions about regulatory perimeter adequacy and supervisory reach. Furthermore, central banks face growing pressure to enhance their capabilities in data governance - namely, the ability to access, process and interpret high-quality supervisory data in real time - to enable informed oversight and agile intervention [

7]. The strategic capacity to manage structured and unstructured data has become a foundational element of modern supervisory infrastructure.

Disparities in regulatory frameworks, divergent national approaches to data localization, and unequal technological capabilities across jurisdictions create an increasingly fragmented regulatory landscape. Such fragmentation complicates the development of consistent supervisory responses, especially in areas involving cross-border financial innovation. Moreover, these asymmetries are particularly acute in emerging and developing economies, which often struggle to align financial innovation with domestic objectives such as financial inclusion, consumer protection, cybersecurity and digital sovereignty. Without targeted support and coordination at the international level, there is a risk that technological progress may exacerbate rather than reduce structural inequalities across jurisdictions.

Ultimately, the effectiveness of central banks in supervising innovation will depend on their capacity to adopt agile, risk-sensitive and cooperative approaches, supported by continuous institutional learning and stakeholder engagement.

The operationalization of the Innovation Hub by the National Bank of Romania (NBR) marks a significant milestone in fostering dialogue between financial authorities and market innovators. This initiative aimed to create an accessible entry point for emerging financial service providers to better understand the regulatory perimeter, while facilitating the regulator’s understanding of novel business models, with a view toward inclusive innovation and systemic stability.

The implementation of the Innovation Hub by the National Bank of Romania has provided a valuable case study in regulatory engagement with emerging technologies, particularly in a jurisdiction characterized by a traditionally bank-centric financial ecosystem. A systematic analysis of the first operational cycle reveals several interrelated lessons relevant for both domestic regulatory design and the broader European conversation on innovation facilitation. The analysis of the Innovation Hub’s implementation revealed several key lessons:

The Romanian Innovation Hub was launched as a structured platform for regulatory consultation. Unlike more permissive or sandbox-based instruments, the Romanian Hub operates on an advisory basis without conferring preferential treatment or legal waivers, thereby maintaining regulatory neutrality. This structure proved particularly valuable in upholding trust from both incumbents and new entrants and avoiding asymmetric supervision.

A critical success factor was the clear internal delimitation of roles, whereby oversight, prudential and legal experts jointly assessed each submission that needed an authorization. This interdepartmental structure facilitated comprehensive evaluation of innovation proposals, while allowing the regulator to preserve its institutional boundaries.

Yet, an early challenge was the perceived complexity of procedures and the uncertainty regarding the outcome of engagement, particularly among smaller FinTech entities. To address this, the NBR introduced more transparent communication templates and clarified the scope of feedback that could be expected.

Despite the advisory nature of the Innovation Hub, participation offered an informal yet structured validation for innovators seeking funding or building compliance in the context of seeking a future authorization.

Regulatory innovation initiatives require a clear institutional mandate and procedural predictability in order to gain market trust. The Romanian model, built around a cross-departmental review mechanism and without legislative amendments, succeeded in maintaining perceived neutrality and avoiding conflicts with formal supervisory procedures. However, the absence of legally binding outcomes initially limited its perceived utility among some FinTech actors, especially those unfamiliar with the functioning of regulatory institutions. This suggests that clarity of purpose, combined with transparent non-binding feedback protocols, is essential in the early phases.

Moreover, internal coordination proved critical to maintain consistency and avoid fragmentation in the response to inquiries. The centralized channeling of innovation-related queries through the Innovation Hub (rather than via informal departmental contacts) helped ensure that all queries received consistent consideration. This internal coherence also created an opportunity to identify systemic themes across seemingly disparate proposals.

The Innovation Hub’s first years of activity revealed a concentration of interest around several recurring themes, including payment initiation services (PIS), account information services (AIS), electronic money issuance and smart contract-based automation. While some proposals focused on marginal improvements to existing services (such as customer experience optimization), others presented more transformative use-cases involving DLT-enabled settlement layers, biometric authentication and AI-driven credit scoring.

However, less than 20% of the inquiries were assessed as involving substantial regulatory uncertainty. A considerable share of applicants sought clarification on basic licensing thresholds, particularly in the context of the PSD2 and e-money regimes. This underscores the persistent information asymmetries and highlights the relevance of regulatory guidance even in the absence of new legal questions. It is worth mentioning that the role of national hubs is not just relevant for the national setting, but also in ensuring consistency and reducing cross-border regulatory arbitrage, as Romania is a member of the European Union and it ensures the application of the relevant European and national legal requirements.

From a technological perspective, the applications analyzed revealed certain maturity gaps. While the Romanian FinTech ecosystem displays high adaptability in user interface (UI) development and digital onboarding tools, there is limited in-house capacity of the FinTech’s to design back-end architectures with robust security layers. This imbalance translates into increased reliance on third-party providers for core functionalities, with implications for both operational resilience and oversight complexity under frameworks such as DORA ). This observation reinforces international findings regarding the uneven technological depth across innovation clusters in emerging markets [

16].

Another significant lesson concerns the nature of the issues raised by applicants. Although the Hub’s mission was to assist with navigating regulatory complexity, a majority of queries did not involve high-consequence legal grey zones or legal innovation but rather requests stemming from limited regulatory literacy - basic requests for clarification regarding licensing thresholds, registration requirements or scope limitations under current legislation, such as PSD2 and the e-money directive.

From a supervisory perspective, this outcome underscores the persistent asymmetry in access to regulatory interpretation tools and reaffirms the need for public-facing guidance documents and simplified regulatory explainers. In addition, some inquiries revealed confusion about the relationship between national regulatory frameworks and EU-level directives, suggesting a need for better articulation of subsidiarity boundaries in public communication. This reflects the fact that innovation support mechanisms must be designed not only to address disruptive technologies but also to bridge routine informational gaps.

An additional point of interest is the temporal mismatch between the development cycle of FinTech solutions (if the commercial model had evolved or been withdrawn) and the institutional pace of regulatory clarification.

A lesson learned from the Romanian experience relates to the internal value of the Innovation Hub as a driver of supervisory modernization. While originally conceived as a communication bridge toward the market, the platform also served as a mirror through which the authority identified areas of internal vulnerability. Therefore, a valuable effect of Romania’s Innovation Hub was its function as a trigger for institutional introspection. While its formal objective was to assist market actors navigating legal and procedural ambiguities, the platform also revealed gaps in regulatory preparedness related to some aspects of the emergent technologies. These learning effects are manifested across multiple dimensions: organizational, cognitive, procedural, and inter-departmental.

Firstly, the diversity of queries, ranging from biometric identity verification and API connectivity to AI-enabled credit scoring and token-based remuneration, surfaced supervisory knowledge asymmetries and limitations in interpretive agility. In particular, cases involving overlapping regulatory frameworks exposed the need for cross-functional collaboration and more granular internal guidance.

Secondly, the Hub functioned as a catalyst for internal training, prompting the development of thematic briefings, technology-specific checklists and inter-departmental knowledge-sharing sessions. These initiatives strengthened the internal supervisory capacity related to FinTech-specific risks, especially those related to outsourcing chains, real-time data flows and interfacing with non-bank platforms.

Thirdly, the Innovation Hub helped to institutionalize new modes of thinking about innovation - not as a marginal, optional dimension of supervision, but as a structural driver of change across all regulatory functions. Interviews with staff involved in the review process suggest that participation in the Innovation Hub prompted a reconsideration of how proportionality, risk-based assessment and regulatory neutrality are operationalized in emerging domains. This shift from rule-centric to context-sensitive supervision mirrors the broader evolution of financial oversight in data-rich environments.

Finally, the Hub enhanced interdepartmental reflexivity by facilitating the creation of common interpretive baselines across departments.

The NBR initiated targeted internal briefings and cross-functional workshops to build capacity in emerging domains. This learning-by-interaction model confirms the hypothesis that innovation engagement mechanisms contribute to institutional adaptability beyond their immediate consultative function.

Beyond its role as a consultation platform, the Innovation Hub served as a monitoring tool for detecting different innovations development patterns into the financial market, risk propagation and innovation bottlenecks. The structured interaction between innovators and supervisors enabled the authority to early identify emerging risks—such as those related to digital identity, remote customer due diligence or the aggregation of financial data across institutions (open banking and eventually open finance market).

Several lessons emerged from this process. Firstly, innovation often outpaces legal clarity, especially when technological convergence blurs the boundaries between regulated and unregulated activities. Secondly, the degree of regulatory uncertainty varies by institutional profile: start-ups are often unsure about basic definitions and scope conditions, while established players may seek interpretative clarifications on advanced topics (ex. the regulatory perimeter of algorithmic decision-making). Thirdly, the absence of a national framework for innovation testing within certain rules, namely a legislative sandbox, limits the possibilities for supervised experimentation. However, the cost and legal complexity of such frameworks must be weighed against their marginal benefit in small, bank-dominated ecosystems, such as Romania [

44].

The Romanian experience validates the hypothesis that Innovation Hubs can strengthen internal supervisory capacity. The cases reviewed revealed knowledge gaps that prompted the revision of written sectoral guidance to comply with the legislative requirements.

Regulatory authorities seek to strike a balanced approach that maximizes the benefits of financial innovation while safeguarding consumer interests and preserving systemic stability. One method for achieving this is by introducing transparent and consistent evaluation frameworks for emerging financial products and services. Such frameworks reduce the risk of regulatory arbitrage, whereby entities exploit inconsistencies or gaps in supervision to gain undue competitive advantages. Furthermore, regulators may employ tools such as stress testing and scenario analysis to examine the potential systemic implications of innovation and to enhance the financial system’s capacity to absorb external shocks.

Policy Feedback and Structural Constraints

While the Romanian Innovation Hub generated useful insights into regulatory friction points, the translation of these insights into systemic reform remained partial and under-institutionalized. In principle, one of the critical contributions of Innovation Hubs is to act as feeders into rule-making and supervisory modernization, transforming recurrent bottlenecks or thematic inconsistencies into agenda items for procedural or legislative adjustment.

In practice, however, several structural constraints limited the policy impact of Hub’s findings:

- the Innovation Hub operated without a dedicated innovation policy liaison unit, responsible for aggregating thematic trends, synthesizing engagement outcomes and informing institutional strategies. This lack of structured feedback loops limited the Hub’s influence beyond the boundaries of operational interaction;- the legislative environment in Romania, characterized by relatively prescriptive licensing conditions and limited flexibility in procedural interpretation reduced the space for policy experimentation or proactive adjustment, also taking into consideration the fact that most requirements applicable for the financial system are regulated at the European level, in order to provide harmonization within the European Union, with limited space for the implementation of national options. For example, while several Hub applicants identified barriers related to authorization process overall, cloud governance, experience requirements, interface standardization, anti-money laundering (AML), counter-financing of terrorism (CFT) requirements – with most stemming from known-your customer (KYC) requirements, the absence of a sandbox-like legal architecture meant that no temporary derogation or interpretive flexibility could be offered, even in cases when the risks involved would have been minimal or manageable;

- the low visibility of the Innovation Hub among other public authorities and its limited integration into national digital or FinTech strategies meant that cross-sectoral synergies were largely unexplored. This diminished the potential of the Hub to act as a node in broader regulatory innovation networks, a function increasingly recognized as essential in interconnected financial ecosystems.

Overall, while the Hub successfully performed its role as an interface and internal radar, its contribution to structural regulatory evolution remains contingent on the development of formal feedback instruments, cross-institutional coordination mechanisms and procedural flexibility in future legislative frameworks.

Policy Recommendations and Implementation Guidelines

Drawing from Romania’s Innovation Hub experience, several strategic recommendations can be formulated to enhance the operational, institutional and policy relevance of such innovation facilitation mechanisms. These insights are particularly important for authorities in bank-dominated markets where the innovation ecosystem remains emergent and risk-sensitive supervision must be preserved.

Innovation support should reflect the diversity of applicant profiles and the heterogeneity of regulatory complexity across proposals. A tiered approach -distinguishing between basic queries, interpretative uncertainties and strategic innovation with system-level relevance would allow more efficient resource allocation.

While the Romanian Innovation Hub benefited from internal coordination, applicants frequently reported limited visibility regarding the review process and timelines. Publishing anonymized examples of past inquiries (with regulatory responses), alongside an indicative response timeframe, could enhance procedural trust without compromising confidentiality. Moreover, clear disclaimers regarding the legal nature of feedback should accompany all engagements.

Innovation hubs generate high-value, structured data on trends, technologies and regulatory frictions. However, in most cases, including Romania, such data remains underutilized institutionally. Authorities should consider embedding Innovation Hub outputs into their dashboards or cross-functional alert systems, particularly to track market entry patterns, technology adoption risks or cross-border regulatory pressures.

An effective innovation strategy requires internal feedback mechanisms that link Innovation Hub activities with regulatory drafting units. In the Romanian case, while initial consultations influenced internal training and licensing practices, no structured pathway existed to channel recurring regulatory questions into forward-looking policy reform agendas. A dedicated Innovation Policy Liaison function could ensure institutional learning is captured and institutionalized.

To mitigate regulatory arbitrage and promote consistency across EU jurisdictions, Romania’s Innovation Hub could be integrated more actively into cross-border frameworks such as the European Forum for Innovation Facilitators (EFIF). Joint consultations, shared registries of recurring themes and pilot testing of interoperable policy templates may increase efficiency and reduce duplication.

While legislative constraints currently preclude the implementation of a formal sandbox in Romania, a modular, non-binding experimental interface could be piloted under the Innovation Hub for selected use cases with transformative potential. This model would allow testing supervisory approaches without committing to regulatory allowance.

In emerging ecosystems where regulatory complexity, legacy infrastructure and interpretive uncertainty combine to limit market access, Innovation Hubs can play a critical role in helping new entrants (particularly payment-focused FinTech’s, that the Romanian Innovation Hub focused on) overcome structural barriers. Drawing from both Romania’s experience and established international frameworks, several operational and policy-oriented practices can be identified to enhance the value of Innovation Hubs as enablers of inclusive financial innovation:

One of the most cited challenges by payment innovators relates to the authorization process, particularly for entities unfamiliar with the financial sector. To address this, Innovation Hubs should adopt modular support schemes that segment applicants by their maturity level and regulatory proximity (ex. pre-licensing advisory, ongoing compliance dialogue, post-authorization adjustment). This approach, implemented by institutions such as the Dutch AFM and the UK FCA, helps reduce uncertainty while allocating supervisory resources proportionally.

Difficulties in understanding and implementing AML/KYC requirements have been consistently reported by FinTech’s.

Innovation Hubs should develop clear guidance packages for payment service providers regarding acceptable digital onboarding procedures, risk-based customer due diligence models and the use of public or certified third-party identity validation tools. Additionally, Innovation Hubs can help bridge the information asymmetry regarding available national identity data sources, such as eID systems or public registries.

A recurring obstacle is the regulatory ambiguity surrounding the use of cloud computing services, particularly in jurisdictions where supervisory guidance is limited or fragmented. To reduce friction, Innovation Hubs should offer pre-engagement diagnostics on cloud compliance, including documentation requirements, auditability expectations and data sovereignty implications. These consultations can reference DORA-compliant principles and should involve cross-departmental input from ICT risk units.

Innovation Hubs should play an active role in communicating clarified regulatory expectations concerning the licensing process for payment service providers, with particular emphasis on operational and security requirements, including those related to governance and internal control frameworks.

In Romania, the absence of consolidated public templates (other than the legal requirements which are public) and guidelines has contributed to perceived inaccessibility. Publishing past cases in the form of anonymized case studies, synthetic decision trees and a checklist of all requirements (documentation and implementation needed), that could be used for orientation, not binding interpretation, could reduce the cognitive compliance burden for first-time applicants.

Many applicants report a lack of access to standardized application programming interfaces (APIs), validation interfaces, or test environments needed to build PSD2-compliant solutions. Innovation Hubs should collaborate with central infrastructure providers (e.g., payment systems operators, ID issuers) to offer sandbox-like environments for testing onboarding flows, strong customer authentication, and consent mechanisms under supervised conditions. Such environments could accelerate product readiness and reduce regulatory friction.

Given the limited and rather small number of third-party providers operating in several Member States — including Romania — Innovation Hubs could enhance their support function by establishing dedicated consultation tracks for specific categories such as account information service providers, payment initiation service providers and non-bank acquirers. These tracks should focus on identifying and addressing practical implementation challenges, particularly those related to access to bank APIs, the functionality of fallback mechanisms, and the availability and quality of data. Such an approach would be consistent with the recommendations set out by the European Forum for Innovation Facilitators [

2].

Finally, Innovation Hubs could act as conduits for regulatory improvement, not just interpretation. When recurring issues are identified, these insights must be translated into institutional feedback loops toward legislative or procedural reform, although the initiation of an update of the European legislation is not that fast (e.g., it requires consultation and negotiation between all member states). But the information about the national context and priorities is useful during the mentioned negotiations and review of the updated proposals.