1. Overview

Each person is born with a few novel genetic changes, known as

de novo mutations, that occur either during gamete formation or during embryogenesis [

1]. Both DNA repair and apoptotic machinery are effective to remove the damaged germ cells [

2], while these elimination capacities decline in the late spermatogenesis, allowing the accumulation of DNA lesions in the sperm(atids) [

2,

3]. The retained DNA damage in sperm is experimentally proven to induce embryonic developmental defects and congenital abnormalities in the next generation [

4] unless it is repaired by maternal factors after fertilization [

5]. Owing to the absence of homologous templates, zygotic repair of paternal double-strand breaks (DSBs) depends on non-homologous repair mechanisms that are considered error-prone. This can explain why

de novo mutations including copy number variations in the next generation are mostly of paternal origin [

6]. In somatic cells, single-strand breaks (SSBs) are the most common DNA lesions, with tens of thousands induced daily in each cell [

7]. Base excision repair is a primary response pathway for the repair of deleterious DNA lesions [

8], including non-bulky DNA adducts, apurinic/apyrimidinic (AP) sites [

9], and SSBs. If unrepaired or incorrectly repaired, these lesions threaten genetic integrity through their potential conversion to DSBs during DNA replication. DSBs are the most difficult DNA lesions to repair, and the critical threshold of DSBs in a nucleus may be very low [

10,

11]. The number of DSBs is not proportional to the incidence of deleterious DNA lesions, because those over a critical threshold cause fertilization failure or pregnancy loss. Detection of the early symptoms of DNA fragmentation is essential as a diagnostic measure in clinical assisted reproductive technology (ART). Considering their relative frequencies, single-nuclear DSBs and SSBs, including AP sites, are preferably analyzed together.

Numerous studies have focused on the effects of DNA damage on fertilization, post-implantation embryo development [

12], and sperm-derived congenital anomalies in ART [

13]. Over the past two decades, nonspecific single-nuclear DNA damage in human sperm has been examined with the comet assay (CA) [

14,

15], sperm chromatin structure assay (SCSA) [

16,

17], sperm chromatin dispersion test [

18,

19], and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling assay [

20]. We prepared human sperm with or without DNA fragmentation and examined their cellular properties [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]. Comparative studies using these two extremes suggested that the abovementioned techniques did not pass the first step of qualitative validation [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]. Their underlying principles and technical shortcomings alerted us to the importance of comparative standards, calibration curves, required sensitivity, and eligibility criteria for test subjects in validating the quantitative performance of analytical methods in this field. In the CA, conventional submarine gel electrophoresis (SGE) is used, and the degree of DNA damage is evaluated as the number of granular segments discharged from the origin, the so-called comet tail [

14,

15]. We developed mono-dimensional single-cell pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (1D-SCPFG) to address the technical shortcomings of SGE [

26,

27]. Accordingly, the naked DNA mass, prepared from human sperm by means of in-gel tryptic digestion, discharged long-chain fibers from the origin, and fibrous and granular segments separated beyond the tips of the fibers. Subsequently, we developed a novel angle-modulated two-dimensional single-cell pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (2D-SCPFGE) [

25,

28]. Upon continued electrophoresis after 150° rotation, long-chain fibers unexpectedly extended obliquely backwards from the origin, and fibrous segments were drawn out from a bundle of long-chain fibers that extended during the first electrophoresis. Even employed pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, one-dimensional current produced false-negatives for DNA fragmentation analysis [

25,

28].

2D-SCPFG is an unprecedented technique, we accumulated the following technical competencies to exclude false-positive and -negative: 1) purification of motile sperm without DNA fragmentation and immotile sperm with end-stage fragmentation from human semen, for use in comparative standards and as test objects; 2) low-temperature liquid storage in a non-aqueous solvent to protect the sequential integrity of the DNA; 3) dissemination and adherence of the sperm to a glass slide; 4) embedding of the sperm into a thin agarose film; 5) in-gel swelling of the tightly packed nucleus; 6) in-gel proteolysis of nucleoproteins to prepare the naked DNA fibers; 7) development of a round electrophoresis tank with three electrode pairs; 8) the composition of the antioxidative electrophoresis buffer; 9) development of angle-modulated 2D-SCPFGE for the separation of long fibrous segments from intact fibers; 10) 2D-alignment of single-nuclear naked DNA fibers; 11) development of post-electrophoretic fluorescent staining, and anti-DNA fragmentation additives to protect the DNA sequence under excitation with blue light; and 12) image processing of the region of interest (ROI).

Although 2D-SCPFGE was developed as a tool for DNA fragmentation analysis, with angle rotation providing various 2D-alignments of single-nuclear DNA fibers, from another perspective, it opens up new horizons in the huge DNA science, as explored in this review.

2. Observation of DNA in Macro- and Micro-PFGE

Agarose can be used to form large-pore, thermoplastic gels consisting of bundles of polysaccharide chains held together by hydrogen-bond cross-linking. SGE with a mono-directional current is the most commonly performed macroscopic gel electrophoresis for DNA analysis. From the perspective of the present review, its most fundamental components are proteolysis of the cell mass, subsequent deproteination (for example, by means of spin columns with glass-fiber filters), and migration of the naked DNA through several or more centimeters of the gel. As the phosphate ions in the DNA are fully dissociated, anionic DNA migrates to the cathode, regardless of the pH of the electrophoresis buffer, at a rate inversely proportional to the size of the DNA. The composition and ionic strength of the buffers, as well as the voltage–current characteristics, influence the electrophoretic behavior of DNA. The simultaneous electrophoresis of a set of known DNA size markers can be used to control for such variation, enabling the size determination of a DNA fragment in base pairs according to its electrophoretic mobility.

Macro-PFGE, developed by Schwartz and Cantor in 1984 [

29], permits the determination of DNA fragment sizes of up to 10 Mb. The gel size is similar to that for normal SGE; however, the most distinctive feature of macro-PFGE is that the direction of the voltage is periodically switched, causing large DNA to migrate in a zigzag pattern through the agarose pores [

30,

31]. As long DNA is very fragile and susceptible to shearing forces, the mass of pure cultured prokaryotes is embedded in an agarose plug and proteolyzed; moreover, pre-electrophoretic downsizing with restriction endonucleases is necessary for migration of segments of prokaryotic DNA in macro-PFGE. Currently, bacterial DNA fingerprinting is the main application of macro-PFGE, whereas its use for eukaryotes is limited to yeast [

29].

Single-cell micro-PFGE [

25,

26,

27,

28] is quite different from the abovementioned two macroscopic methods. The test objects are free cells or those dispersed from eukaryotes. These are either suspended in a melted agarose to form a thin film on the glass slide, or disseminated on the glass slide by means of automatic centrifugal smearing and embedded in agarose to form thin films. After in-gel proteolysis, the mixture of intact chromosomal DNA and segments of various lengths is electrophoresed without downsizing by restriction endonucleases. The electrophoretic profiles are observed via fluorescent microscopy.

3. Preparation of Comparative Standards for DNA Fragmentation Analyses

We previously prepared human motile sperm without DNA fragmentation and immotile sperm with end-stage DNA fragmentation for use as comparative standards in DNA fragmentation analyses, as detailed below [

25,

28]. In clinical ART, the former can be used for

in vitro fertilization as well as intra-cytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI).

3.1. Equilibrium Sedimentation in OptiPrep

Sperm concentration and motility are evaluated according to the World Health Organization reference manual [

32]. We diluted semen specimens three times with 20 mmol/L HEPES buffered Hanks’ solution (pH 7.4; hereafter referred to as “Hanks”). OptiPrep density gradient medium (Axis Shield, San Jose, CA, USA) was made isotonic with 20 mmol/L HEPES-NaOH (pH 7.4), Hanks’ powder, and 2.0 mg/mL human serum albumin (apparent density: 1.17 g/mL; hereafter referred to as “OP”). The suspension was layered on 0.5 mL OP and centrifuged at 600 ×

g for 10 min. The precipitate and interphase layer were resuspended to 1.0 mL. It was layered on 0.5 mL OP and ultracentrifuged at 10,000 ×

g for 10 min to separate the interphase layer from the sediment [

25,

28].

3.2. Differential-Velocity Sedimentation in Percoll

The interphase layer and the sediment were retrieved separately, diluted several times with Hanks, and centrifuged in a 90% Percoll (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA) density gradient as described previously [

21,

22,

25,

28]. The 90% Percoll was made isotonic with 20 mmol/L HEPES-NaOH (pH 7.4), Hanks’ powder, and 2.0 mg/mL human serum albumin (apparent density: 1.12 g/mL; hereafter referred to as “Percoll”). Thereafter, 5.0 mL Percoll was placed in a conical test tube (15 mL) and 1.0 mL Hanks was added. This solution was subjected to 10 revolutions at an angle of 30° to create a linear density gradient. The sperm suspension was loaded on the gradient and centrifuged in a swing-out rotor at 400 ×

g for 30 min. The motile sperm without DNA fragmentation were retrieved in the interface layer of OP/the sediment of Percoll. Hanks (1.0 mL) was layered on the sediment of the Percoll (0.2 mL) and incubated for 60 min at ambient temperature. Motile sperm that swam up into the upper half of Hanks were recovered. Immotile sperm with end-stage DNA fragmentation were obtained from the sediment of OP /the intermediate layer of Percoll [

21,

22,

25,

28]. The motile and immotile sperm are termed “purified sperm” (PS) and “denatured sperm” (DS), respectively. The cellular features of these two extremes differ greatly, corresponding to sperm that have not yet and those that have already undergone apoptosis and been denatured, respectively [

21,

22,

25,

28]. PS were prepared from a dozen semen samples; the preparation that yielded the highest negative rate for DNA fragmentation by means of 1D-SCPFGE was employed as the standard. DS was prepared from the same semen samples. PS and DS were preserved in the low-temperature-storage medium (see section 5-5).

4. Lessons Learnt from Conventional Analytical Methods

Before newly developed analytical methods are used for clinical diagnoses, they have to pass multistep validations by using the comparative standards. Conventional DNA damage analyses cannot pass the first step of quantitative validations owing to their underlying principles and technical issues.

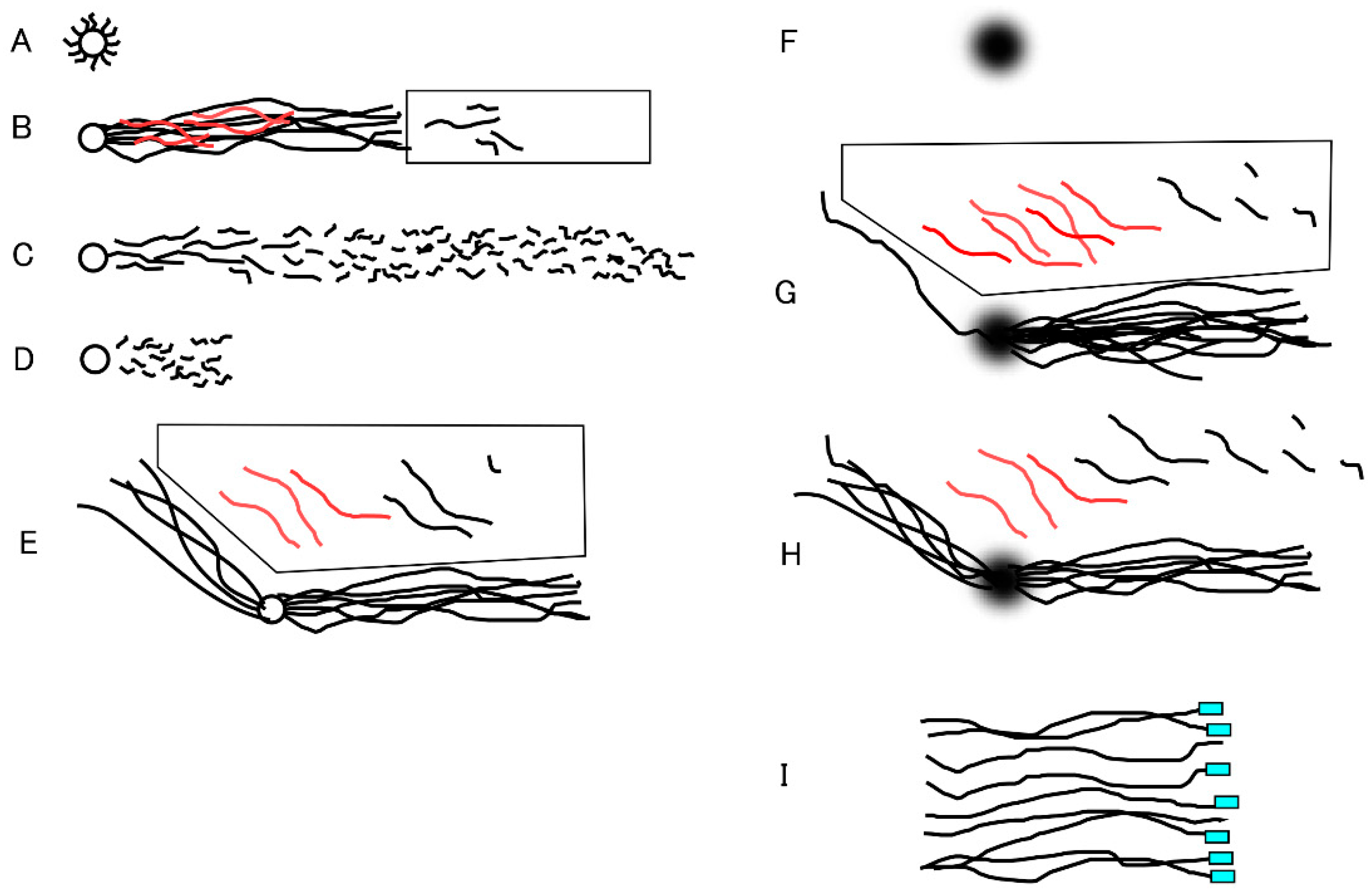

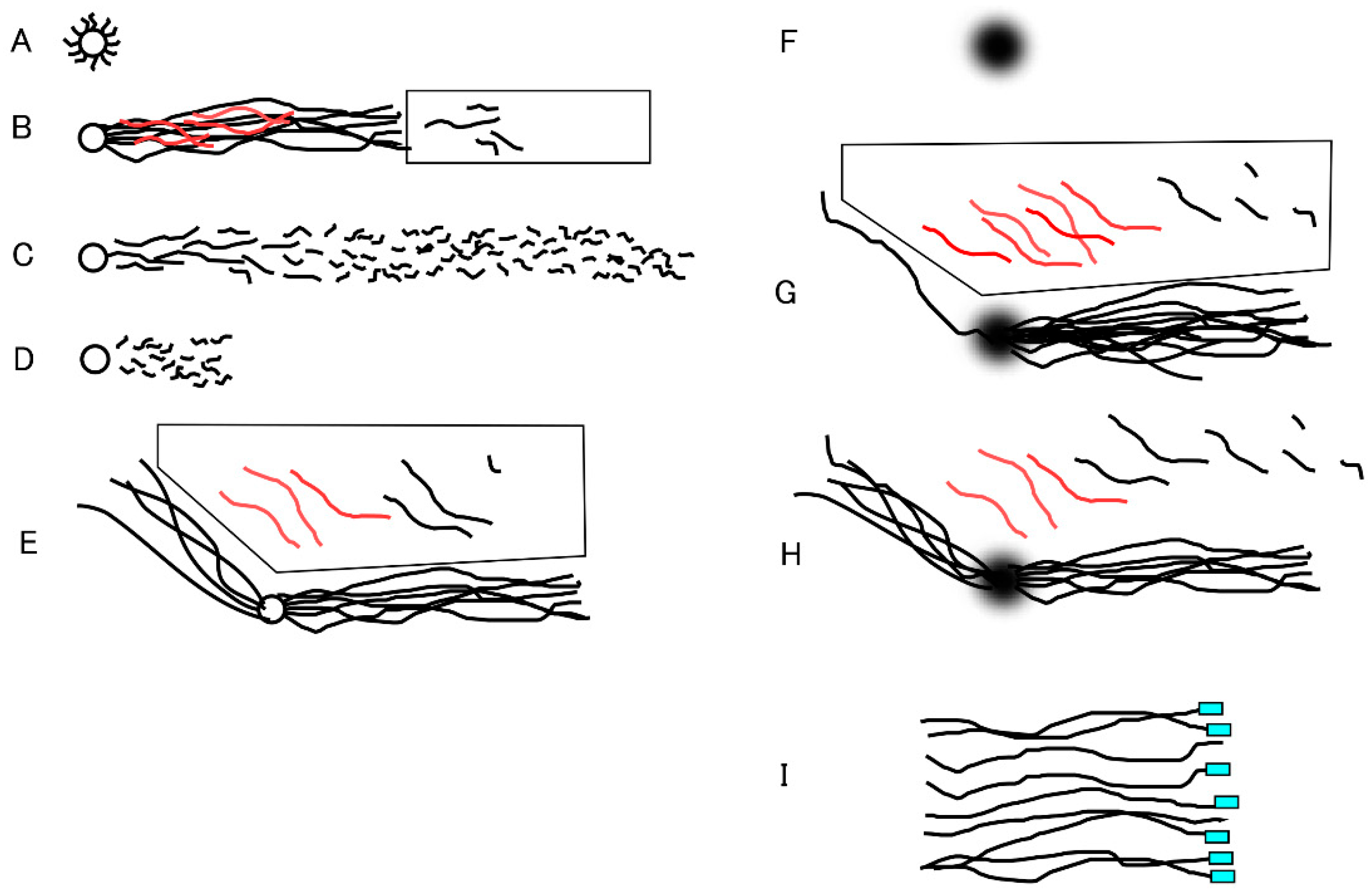

Figure 1 illustrates the course of development of 1D- and 2D-SCPFGE, and

Table I summarizes the updated protocol for 1D- and 2D-SCPFGE. This section explains the issues with SCSA and CA.

4.1. SCSA Overlooks Interference of Nucleoproteins

SCSA employs a simple bisection principle wherein the intercalation of monomeric acridine orange (AO) into double-stranded DNA or the adsorption of oligomeric AO to single-stranded DNA yields green or red fluorescence, respectively [

16,

17]. Several experiments proved that AO cannot detect DNA damage in human sperm: AO staining cannot distinguish PS from DS under a microscope or via flow cytometry; the nucleus and cytoplasm of lymphocytes yield green and red fluorescence, respectively; and in-gel tryptic digestion removes the red fluorescence [

21,

25]. These phenomena suggested that green fluorescence resulted from intercalated AO, and red fluorescence from AO adsorbing to nucleoproteins rather than single-stranded DNA. DNA fluorescent probes often interact with various intercellular materials besides DNA, and the fact that SCSA does not account for the interference of nucleoproteins [

21,

25] taught us the importance of quantitative validations by using PS and DS.

A technical issue with SCSA is that unseparated human semen is used as the test specimen [

16,

17]. Even in normozoospermia, over half the sperm in a given semen sample have already been denatured to a state of end-stage fragmentation [

23]. As mentioned in section 3, PS is a preferable alternative in clinical ART. The aim of DNA damage analyses is to detect early symptoms in the separated PS; the unseparated semen are ineligible.

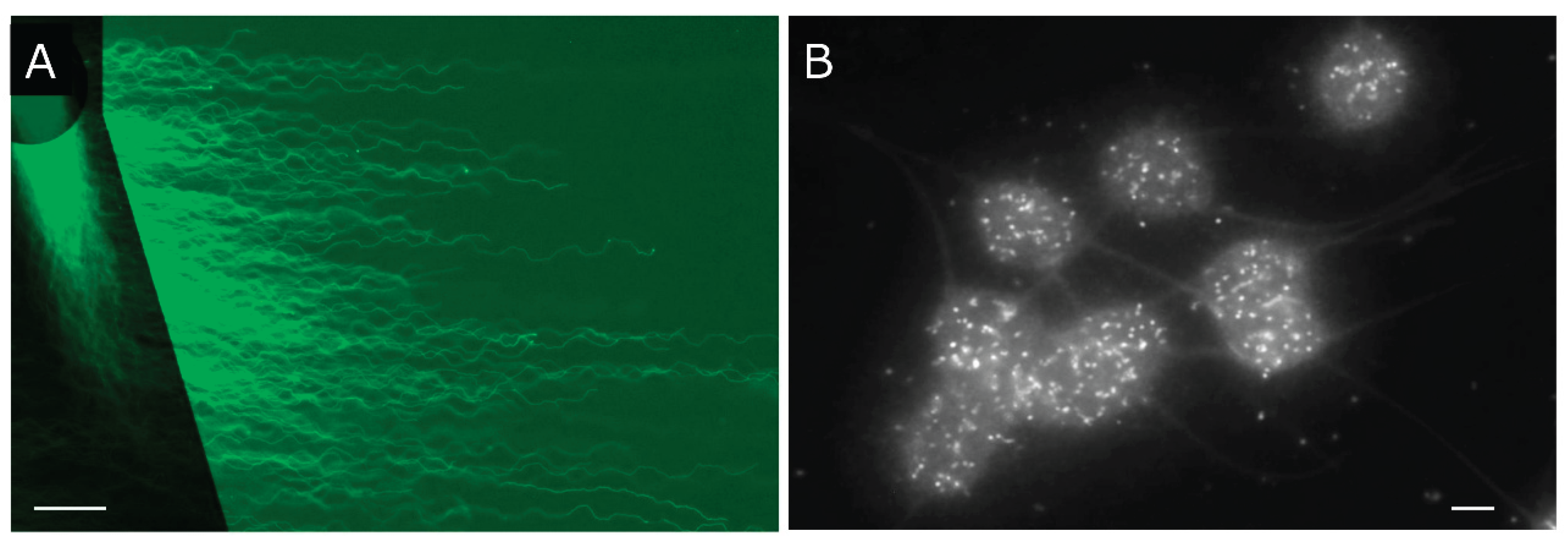

4.2. Lack of in-Gel Proteolysis and SCPFGE Impairs the Sensitivity of the Neutral and Alkaline CA

In the neutral CA, a high-salt extraction of nucleoproteins and conventional SGE are used, and the degree of DNA damage is evaluated from the number of granular segments (the comet tail) [

14,

15]. High-salt extraction and SGE discharged granular segments from DS (

Figure 1D) but not elongated long-chain fibers from PS. 1D-SCPFGE pulled out long chain fibers (

Figure 1B) from the in-gel proteolyzed PS (

Figure 1A). In-gel proteolysis of DS yields a dramatic increase in the number of granular segments (

Figure 1C) [

22]. 1D-SCPFGE visualized the progress of DNA fragmentation in human sperm; first, a few large fibrous segments appear beyond the anterior end of a bundle of elongated long-chain fibers, and cleavage proceeds until almost all the DNA fibers are shredded into granular segments [

26,

27]. The neutral CA can only be used to detect the end-stage fragmentation.

Human sperm nucleoproteins consist of protamines [

33,

34], histones [

35], condensins [

36], and cohesins [

36]. The DNA–nucleoprotein complex is fixed to the nuclear membrane via the nuclear matrix [

37,

38]. Although high-salt solutions are widely used to extract protamines [

39], unextracted nucleoproteins remain fixed both to intact DNA fibers and segments. Only a fraction of the granular segments escape such fixation are discharged as the comet tail. Comparative experiments between PS and DS revealed the importance of in-gel proteolysis and SCPFGE, as neither the SCSA nor the neutral CA account for the interference of nucleoproteins, and only naked DNA is analyzable via electrophoresis.

Alkaline-labile sites (ALSs) such as AP sites [

8,

9] lead to DNA strand cleavage at a high pH. The alkaline CA, in which DNA is treated with 300 mmol/L NaOH [

14,

15], induces DSBs from SSBs and at ALSs. Alkaline-based SSB assays have high risks of overestimation. When PS are treated with 30 mmol/L NaOH, 1D-SCPFGE with in-gel proteolysis results in the discharge of larger amounts of granular segments than the neutral CA with high-salt extraction and SGE [

22]. At least some of the nucleoproteins tolerate to high alkalinity, remaining fixed to the newly generated granular segments via alkaline hydrolysis and preventing migration. A lack of in-gel proteolysis produces false-negative results in both the neutral and alkaline CAs.

Alkaline-based SSB assays are technically challenging. As the dose-response curve of alkaline hydrolysis is very steep, chemical equivalents of NaOH that selectively cleave SSBs but maintain the sequence integrity of double strands have to be accurately defined to ensure reproducibility. The test objects are limited to naked DNA fibers. Another issue is that diluted NaOH is challenging to handle under atmospheric conditions. Commercially available granular NaOH is a deliquescent material and is partly converted into Na2CO3 via adsorption of CO2 in the air. When NaOH stock solution is prepared on a weight/volume basis, it has to be calibrated via acid–base titration on each occasion. Thus, we employ validated NaOH reference solutions for volumetric analyses for all experiments.

5. Technical Specifications for 1D- and 2D-SCPFGE

Operating procedures of 1D- and 2D-SCPFGE are similar. The latter differs only in that one or more angle rotations are introduced after the first electrophoresis. This section introduces the technical specifications of SCPFGE.

5.1. Adherence of Agarose Film to a Glass Surface

For agarose adhesion, we used commercially available MAS-coated glass slides (Matsunami, Tokyo, Japan), on which amino residues have been introduced via chemical surface modification to prevent stripping of the histological section from the slide. The agarose for embedding was bound to the slide at an acidic pH. As described in section 5-3, we modified the pH of the agarose for embedding from 4.7 (acetate buffer) [

22,

25,

26,

27] to 9.0 (Na

2CO

3-NaHCO

3). Although agarose interacts with the ionized amino residues via hydrogen bonds at an acidic pH, it does not interact with those non-ionic residues at pH 9.0.

The surface of the glass slide (2.5 × 6.0 cm area) was coated with 30 mL of 1.0% low-melting-temperature agarose (agarose GB; Nippon Gene, Tokyo, Japan; melts at around 80 °C and gelates at around 25 °C). Once dehydrated, agarose firmly fixes to the glass surface and the agarose for embedding adheres via hydroxyl–hydroxyl hydrogen bonds.

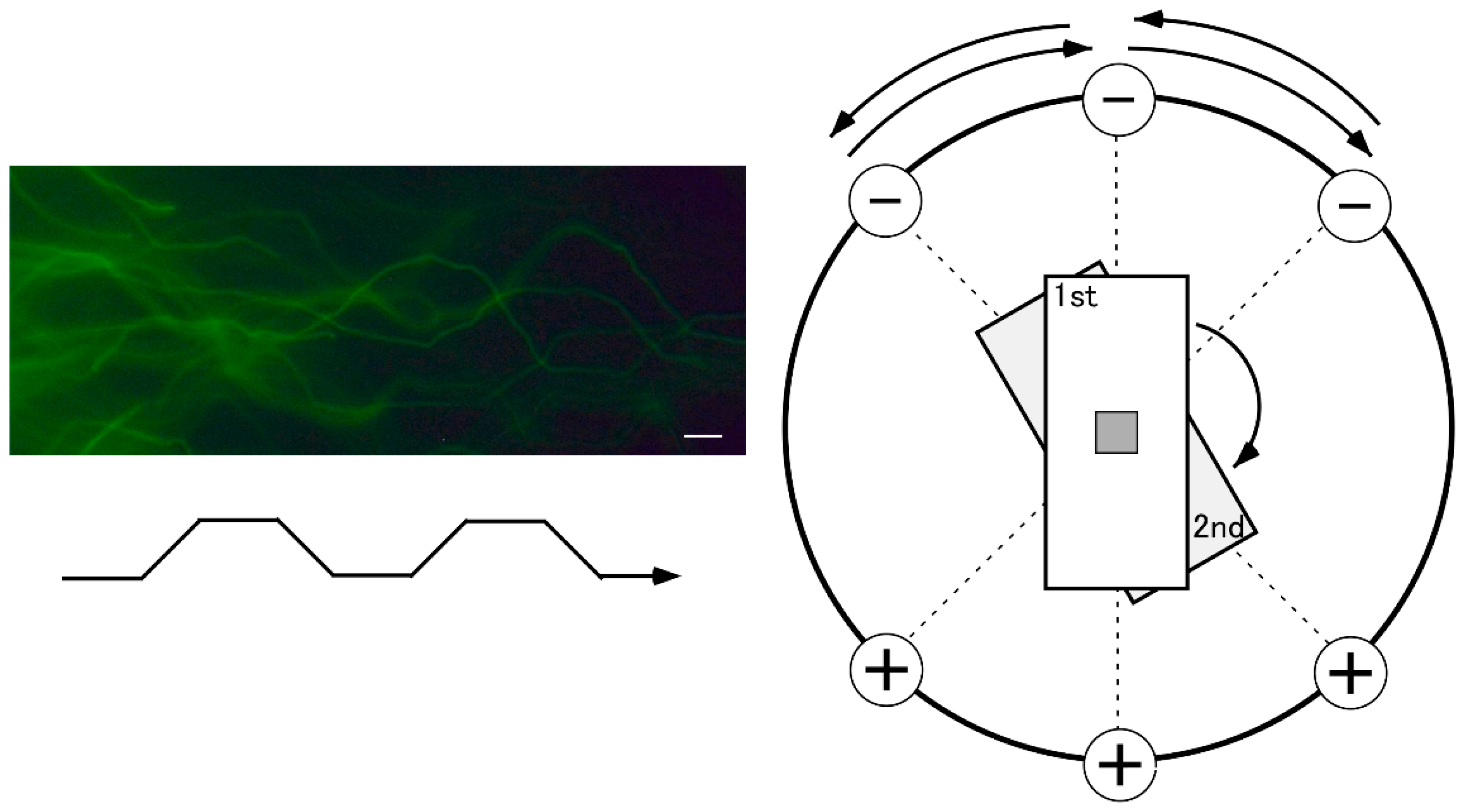

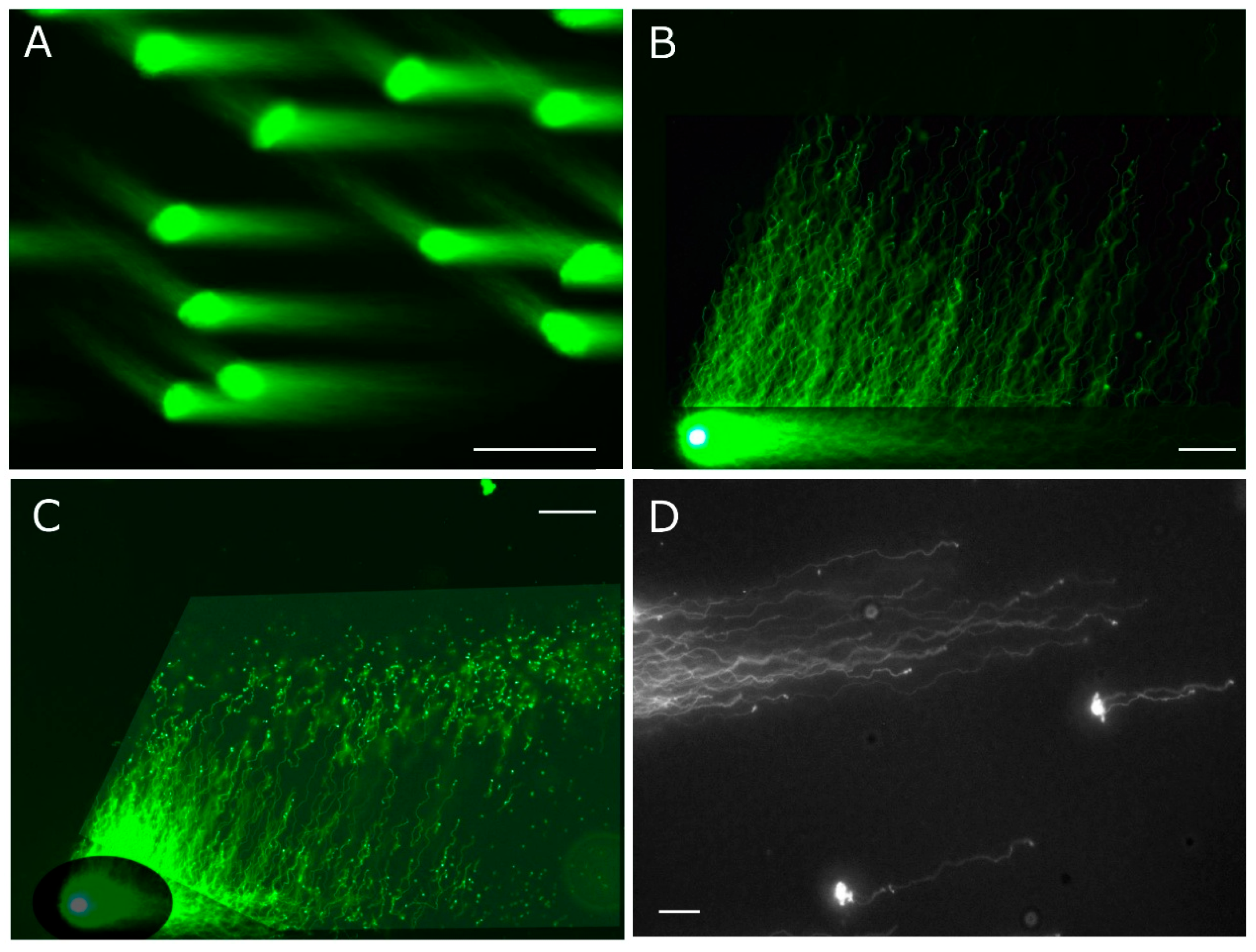

5.2. Equipment for SCPFGE

Figure 2 is a schematic illustration of the round electrophoresis tank for 2D-SCPFGE, equipped with three pairs of electrodes arranged 45 degrees apart. The apparatus should be placed on a stable, level surface. Five glass slides with gel films are stacked vertically in a rack with a pivot for rotation. The embedded DNA should be exactly positioned upon the pivot at the intersection point of the three currents. Electrophoresis is performed at a constant voltage (3.5 V/cm), with 4.0 s switching intervals in the following sequence: left, center, and right, after which the process is repeated in reverse order. We built a time-switching controller in-house. The electrophoresis buffer was deeper than 4 cm to allow immersion of all five slides. We designed a combination of weak organic electrolytes (see section 5-6) to avoid overcurrent of the power supply. High-magnification photography in

Figure 2 reveals the S-shaped tracks of the naked long-chain fibers according to the updated protocol for 2D-SCPFGE (Table I). This shape is altered by the voltage, switching interval, ionic strength of the electrophoresis buffer, and pore size of the agarose.

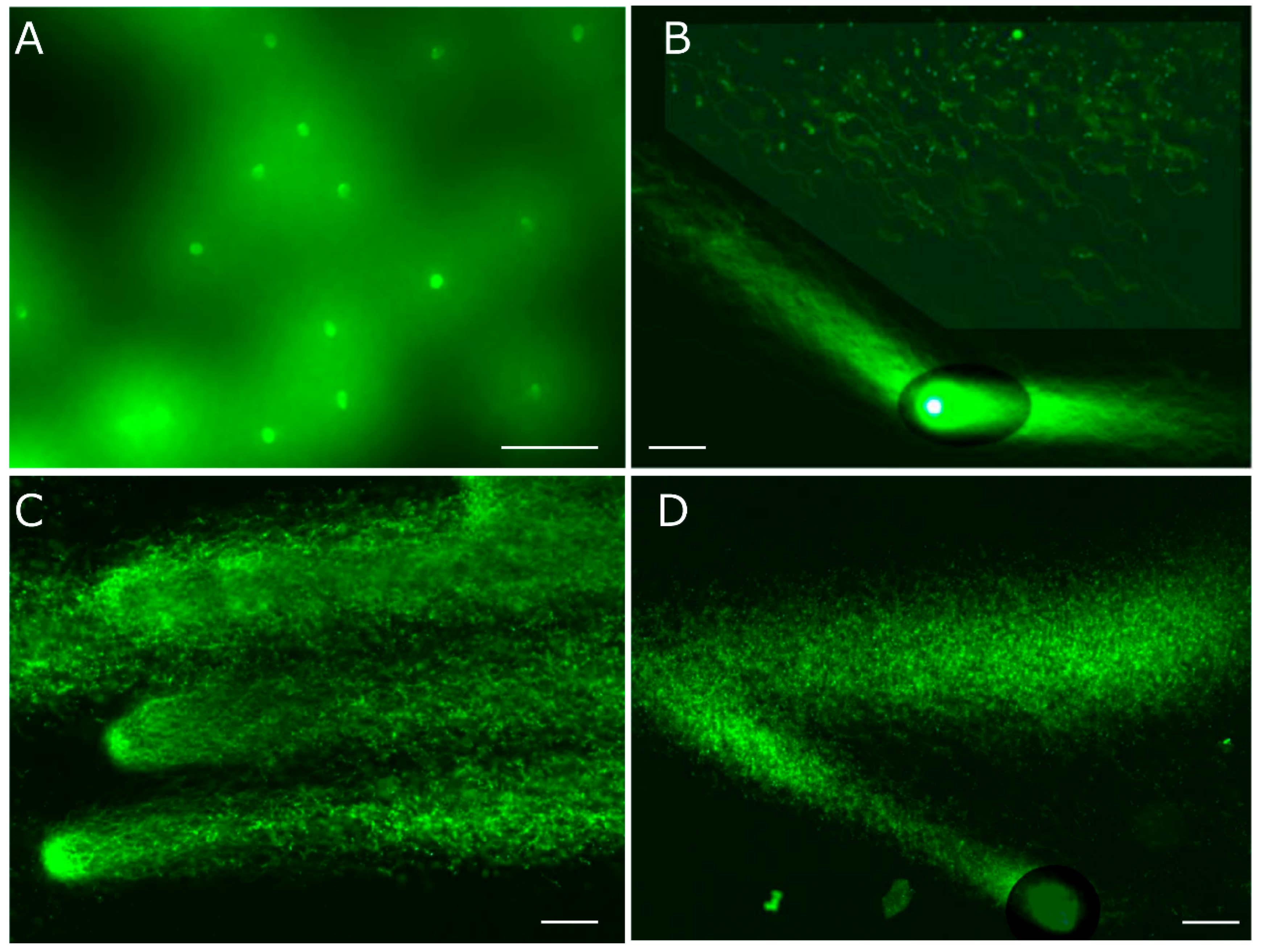

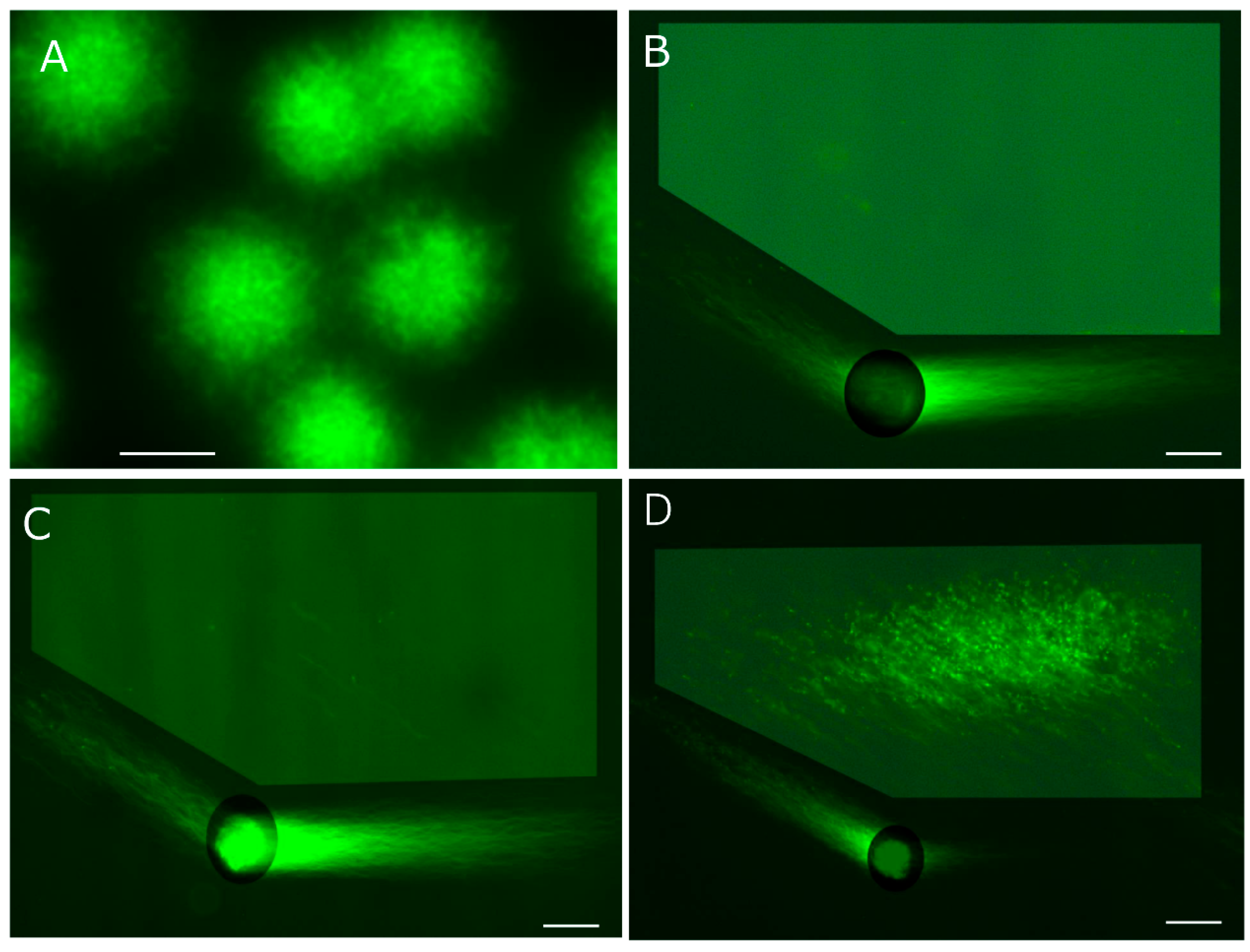

5.3. Simultaneous in-Gel Swelling and Proteolysis

1D-SCPFGE with in-gel proteolysis results in a linear arrangement of the elongated long-chain fibers and the segments (

Figure 1C) [

22,

26,

27]. Former protocols for SCPFGE solidified the agarose immediately after embedding to avoid launching in-gel proteolysis, and the tightly packed DNA mass remained visible as a small, bright core (

Figure 3A). We developed 2D-SCPFGE-0-150 (6/4 min) [

28], in which the gel was turned 150 degrees after the first electrophoresis. All the segments that were previously separated beyond the tips of the elongated long chain fibers became oriented obliquely backward and assembled in the shooting range of a charge-coupled device camera with 200× magnification (Figures 1E and 3B). The second electrophoresis produced unexpected results: additional long-chain fibers were discharged obliquely backwards from the origin and spread out in a fan-like shape (

Figure 1E) [

28]. The long fibrous segments were drawn out from a bundle of elongated fibers to the inner angle of the fan (

Figure 3B). The bright core was still visible at the origin.

Figure 3C,D show 1D- and 2D-SCPFGE profile of DS, almost all the fibers had already been shredded to granular segments, there found no bright core at the origin. 1D-SCPFGE is sufficiently sensitive and rather convenient for observing the advanced and end stages of fragmentation.

To maximize the number of long-chain fibers drawn out in two directions, the tightly packed DNA mass was swollen via simultaneous in-gel swelling and proteolysis (

Figure 1F and

Figure 4A). As summarized in Table I, the protocol of SCPFGE was thoroughly revised. Human sperm (2 × 10

2) were adhered to the agarose-coated glass slide by means of centrifugal auto-smearing. Specifically, 0.5 mL of 0.4% agarose GB (0.1M Na

2CO

3-NaHCO

3, pH 9.0, 0.02% SDS, 1.0 mmol/L EDTA) was melted at 85 °C for 10 min, and each 10 mL proteinase K (recombinant, 20 mg/mL; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), 0.5 mol/L dithiothreitol (DTT) in 0.1 mol/L acetate buffer (pH 4.7), and 1.0 mol/L edaravone (3-methyl-1-phenyl-2-pyrazolin-5-one; ED) in DMSO were added at 42 °C just before use (final concentration: 0.38% of agarose). An aliquot (60 mL) of this solution was mounted on the sperm and covered with a glass slip (2.4 × 2.4 cm) for a thickness of 100 mm. The in-gel swelling (37 °C), chilling on ice (4 °C), and proteolysis (45 °C), described below, were performed in a moisture chamber. The pharmacological features of ED are discussed in detail in sections 5-5, 5-6, and 5-7.

The agarose was immediately chilled on ice for 5 min, followed by in-gel proteolysis at 45 °C for 10 min, the mass of DNA was enclosed in a small, bright core (corresponding to

Figure 3A), Although 2D-SCPFGE-0-150 yielded elongation of long-chain fibers in two directions, some of them remained in the small, bright core at the origin (corresponding to

Figure 3B). When the agarose was incubated at 37 °C for 5 min on a hot plate prior to chilling on ice, the semisolid agarose allowed swelling of the sperm heads without free diffusion of the fibers (

Figure 4A). The increased void space facilitated the permeation of proteinase K. Following such swelling, the first electrophoresis resulted in the discharge of a larger number of long-chain DNA from the swelling mass, whereas those discharged obliquely backward during the second round were dramatically decreased (

Figure 1G and

Figure 4B–D). This profile suggests that the swelling of the DNA mass untangled the fibers, pulling them out more efficiently. After bright enhancement of the ROI, no segments were observed in the inner angle of the fan was deemed as intact according to our tentative definition (see sections 5-7 and 7) (

Figure 4B).

Figure 4C,D represented the typical profiles of early and advanced stages of fragmentation, respectively. If the agarose was incubated at 42 °C for 10 min before chilling, the sperm heads melted, and DNA fibers were diffused freely in the liquefied agarose.

The most important factor for simultaneous in-gel swelling and proteolysis is the alteration of pH of the agarose for embedding from 4.7 to 9.0. The acid dissociation constants of the two thiol residues in DTT are 9.2 and 10.1, respectively, which is why the inter- and intra-disulfide bonds among protamines must be reduced at a pH higher than 9. The optimum pH of proteinase K is 8 or higher [

40]. The guanidino residues of arginine in protamines form ionic bonds with the phosphates in DNA, and the coexistence of DTT and other compounds with sulfate residues, such as SDS, competitively dissociate the DNA–protamine complex at pH 9 or higher, resulting in swelling of the sperm head. SDS exhibited the most potent swelling activity among the organic compounds examined. Only 0.005% SDS yields head swelling in the suspension, whereas the optimum concentration in the semisolid agarose was 0.02%; a higher concentration of SDS caused dispersion of DNA fibers.

In our previous studies, we employed highly purified bovine pancreatic trypsin (EC.3.4.21.4) [

41] for in-gel proteolysis. The substrate specificity and pH dependency for its enzymatic activity are optimal for the digestion of the DNA–protamine complex. Protamines are arginine-rich, basic proteins, and trypsin specifically cleaves the carboxyl ends of lysine and arginine residues [

41]. If the sperm is embedded in agarose containing trypsin at pH 9.0, the DNA mass quickly diffuses. As the activity of trypsin is strictly dependent on pH, it can be kept inactive at a pH of 4.7 until the gel solidifies and reactivated by immersion of the gel into cell-lytic reagents (pH 8). Commercially supplied twice-crystallized bovine trypsin is usually contaminated with pancreatic deoxyribonucleases (DNases), and affinity chromatography, using lima bean trypsin inhibitor-conjugated Sephacryl [

42], is necessary to remove autolyzed trypsin and DNases. Purified trypsin is readily autolyzed and should be stored in solution at a pH < 2.0. Trypsin is undoubtedly optimal for in-gel proteolysis but lacks versatility. Proteinase K [

40] has a chymotrypsin-like broad substrate specificity for aliphatic and aromatic residues of amino acids, and is active over a wide pH range; ready-to-use preparations are supplied commercially for the extraction of DNA from somatic cells. Its substrate specificity is, however, unfit for protamines [

28]. Competitive dissociation of the protamine–DNA complexes with DTT and SDS, and subsequent digestion of other nucleoproteins with proteinase K, allows migration of DNA fibers via SCPFGE [

28]. Overall, rigorous management of the pH, temperature, moisture level, antioxidants, and time are essential to ensure reproducibility in simultaneous in-gel swelling and proteolysis.

5.4. Eligibility Criteria of Test Sperm for SCPFGE

We became acutely aware of the importance of eligibility criteria for test objects when we investigated immunological infertility via anti-sperm antibodies (ASAs) [

23]. During those investigations, Immunoglobin G was partially purified from the serum of the female partner, and the localization of antigenic sites on PS and DS were compared by means of indirect immunofluorescence staining. PS was highly immunogenic for ASAs, but DS had lost antigenicity [

23]. Previous researchers did not account for the heterogeneity of human semen. Even in normozoospermic semen, DS accounts for the majority of sperm, and the examination of ASAs in unseparated sperm produces false-negative results [

23]. The aim of DNA fragmentation analysis is to detect early symptoms in PS. However, once the sperm are fixed and stained or embedded and lysed, the type of sperm from which the DNA is derived is difficult to determine. The eligibility criteria for test specimens should be rigorously defined and should be limited to PS. As shown in section 4-1, SCSA also fails this eligibility criterion.

5.5. Low-Temperature Liquid Storage of Human Sperm

Motile sperm analyzed via 1D-SCPFGE immediately after preparation did not exhibit noticeable differences in electrophoretic features compared to those analyzed after cryopreservation. Using 2D-SCPFGE, we observed unexpected physical damage to the DNA sequence caused by ice crystals. Upon comparison by means 2D-SCPFGE-0-150, the cryopreserved sample yielded substantially higher rates of fibrous segments, but not granular segments, after the second round of electrophoresis, than fresh samples and those stored in low-temperature liquid form [

28]. In the current usage of 2D-SCPFGE to detect naturally occurring DNA fragmentation, the artifactual fibrous segments due to cryopreservation cause false-positive results. If examinations have to be postponed, the previous report used an anti-freezing medium that includes 50% propanediol for liquid storage [

28]. Certain water-soluble, non-aqueous solvents, such as ethylene glycol, propanediol, and glycerin, are far better stabilizers of DNA sequence than water. We developed a modified low-temperature liquid storage medium (0.5 mmol/L EDTA, 0.05% Triton X100, 10 mmol/L ED in anhydrous ethylene glycol) to protect sequence integrity. ED is a scavenger of multiple reactive oxygen species (ROS) [

43,

44]. To minimize the moisture content, the aqueous buffer containing the sperm should comprise < 5% of the liquid storage medium. Although we have confirmed the excellent protective performance of this formula for DNA protection, it has limited practical use.

As described in section 5-1, the sperm is adhered to the agarose-coated glass slide via hydroxyl–hydroxyl hydrogen bonding, and the two hydroxyl residues of ethylene glycol competitively inhibits that adhesion. At least 1000-fold dilution is necessary to enable sperm adherence. At present, we tentatively recommend ethylene glycol as the solvent of choice for low-temperature liquid storage. We are attempting to identify an organic solvent that does not form hydrogen bonds. The sample stored in ethylene glycol is diluted in an appropriate aqueous medium that contains 10 mmol/L ED and 0.5 mmol/L EDTA just prior to analysis.

PS holds great advantages as a substrate for DNA cleavage analyses (see section 6). We have already established the procedures to separate the motile sperm without DNA fragmentation and subsequently verify the DNA sequentiality by means of 2D-SCPFGE. Sperm are non-cell cycling cells, and the tightly packed DNA–nucleoprotein complex protects long-chain DNA fibers. Low-temperature liquid storage permits long-term preservation of DNA without sequential damage. In livestock farming, the seed bull is selected through progeny testing, and the selected bull will have the highest fecundity, including DNA integrity. The separation procedures for human sperm are also suitable for bull sperm without any modification. Depending on availability, purified bull sperm may be the best substrate for DNA cleavage analyses.

5.6. Antioxidative Electrophoresis Buffer

In contrast to proteins with a unique-isoelectric point, anionic DNA migrates to the cathode regardless of the pH of the electrophoresis buffer. For example, its electrophoretic mobilities are similar in acetate-NaOH (pH 3.9), Tris-acetate (pH8.2), and Na

2CO

3-NaHCO

3 (pH 10.0) buffers. The pH range is limited by the tolerance of phosphodiester bonds for acid and alkaline hydrolysis. Electrolysis at the cathode generates singlet oxygen. Electrophoresis buffers containing ED becomes brown near the cathode over time owing to ROS-induced oxidation, and the dissolved oxygen also discolors ED even when no current is applied. The addition of ascorbic acid (AA) suppresses the discoloration of ED, suggesting the importance of water-soluble ROS scavengers in the electrophoresis of DNA. The antioxidative activity of AA covers ROS such as superoxide anions, hydrogen peroxide, and singlet oxygen, as well as hydroxyl radicals [

45]. ED is also a scavenger of multiple free radicals [

43,

45,

46], and is particularly effective against hydroxyl radicals [

47]. Although ED is soluble in lower alcohol and DMSO, and relatively stable in these non-aqueous solvents, it is, however, poorly soluble and readily oxidized in water. As the cathode generates singlet oxygen, we adopted AA as an inexpensive radical scavenger in the electrophoresis buffer. As described in section 6-1, the pro-oxidant action of AA in the presence of transition metals such as Fe and Cu must be considered [

48,

49], and EDTA inhibits such action. As EDTA is a tetramer of acetic acid, we use salt-free EDTA as a substitute for acetic acid. AA powder corresponding to 10 mmol/L is dissolved in the basic solution (20 mmol/L Tris, 1.0 mmol/L EDTA solution, pH 9.2) just before use, and the resulting solution has a pH of 8.0.

5.7. DNA Staining with Fluorescent Dye and Brightening of Digital Images

We used an epifluorescence microscope with a green filter (Axio Imager A1; Carl Zeiss Microimaging, Jena, Germany) to observe the electrophoretic profile, and recorded still images with a high-resolution charge-coupled device camera (AxioCam HRC; Carl Zeiss Microimaging) with 0.4 s exposure. After electrophoresis, the gel film (60 mL) was equilibrated with an antioxidative electrophoresis buffer, and an equal volume of staining solution (X3000 SYBR Gold (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), 0.2 mol/L ED in DMSO) was mounted for 5 min. Excess dye was removed using blotting paper. After staining, the equilibrated gel contained 0.1 mol/L ED, 5.0 mmol/L AA, and 0.5 mmol/L EDTA in 50% DMSO.

Photo-bleaching under the fluorescence microscope involves degradation of the dye molecule by ROS [

50]. SYBR Gold is one of the most sensitive fluorescence dyes for double-stranded DNA, with a high tolerance for photo-bleaching. When observing the naked DNA fibers dyed with SYBR Gold under a fluorescence microscope, those suspended in water were extremely fragile. The synergistic effects of the shearing force due to Brownian motion and exposure of excitation via blue light visibly cleaved the sequence down to granular segments. After SCPFGE, the elongated fibers fixed in the agarose network were quiescent, whereas prolonged exposure of the excitation with blue light caused DNA fragmentation [

21]. If prolonged exposure cleaves the fibrous segments in the ROI, the artifactually produced granular segments cause false-positive results. Thus, dark images due to short exposure times have to be brightened; for this, we used pseudo-exposure in Photoshop CS6 (Adobe, San Jose, CA, USA). At present, the absence of visible segments in the ROI after image enhancement is deemed sufficient to label the DNA sequentially intact. Direct observation through an ocular lens is more sensitive than observation via the digital camera. When we determined the rate of DNA fragmentation by eye, we counted more than 100 sperm. We discuss the definition of “intact” sperm in DNA fragmentation analyses in section 7.

The synergy of 5.0 mmol/L AA and 0.1 mol/L ED in 50% DMSO exhibits potent anti-DNA fragmentation activity under the excitation light. In general, DNA fluorescent dyes usually consist of cationic and hydrophobic regions; the former, usually tertiary amines, bind with the phosphates in the DNA backbone, whereas the latter produce fluorescence via intercalation into the major and/or minor grooves of DNA. When SYBR Gold is dissolved in lower alcohol, hydrophobic environment suppressed intercalation, and DNA fibers are deformed owing to dehydration. At present, DMSO is the optimum solvent for SYBR Gold staining and the anti-DNA fragmentation activity of AA and ED. Moreover, DMSO acts as a free radical scavenger, particularly preventing DNA nicking mediated by ionizing radiation or iron/hydrogen peroxide-generated hydroxyl radicals [

51]. These agents do not deform DNA fibers, and the anti-DNA fragmentation effect continues during prolonged exposure.

When the swollen DNA mass (

Figure 4A) is stained with the abovementioned formula prior to 1D-SCPFGE, the long-chain fibers are scarcely discharged from the origin. The electrophoretic mobility of DNA is dependent on the anionic phosphates in the backbone. The lack of discharge may be caused by the reduction in the negative charge due to the binding of a large quantity of SYBR Gold molecules to the sequence. DMSO facilitates the intercalation of the dye, resulting in fluorescence enhancement. Use of the present formula is limited to post-electrophoretic staining.

5.8. Accuracy Control of SCPFGE

As is well known, agarose forms a thermoplastic, large-pore gel via cross-linking of bundles of polysaccharide chains by hydrogen bonding. Commercially supplied agarose preparations are diverse in terms of melting and gelation temperatures and mechanical gel strength, depending on the number of hydrogen-bond cross-links. SGE in agarose is the most common technique performed in molecular biology, and researchers often do not consider the diversity in agarose. The most important technical competency in SCPFGE is the choice of agarose preparation. Extra-large pores are necessary for electro-elongation of naked DNA fibers, which means that cross-links should be sparce; such a gel has a low melting point and weak mechanical strength. The gel film is made at the minimum gelation concentration to maximize the pore size. For instance, when we ascertained the optimum concentration of agarose GB for SCPFGE, we discovered that a 0.38% gel promoted the elongation of fibers, the fibers were substantially shorter in a 0.55% gel, and a 0.29% solution did not gelate. In-gel swelling causes the tightly packed DNA mass to untangle (

Figure 1G and

Figure 4A), resulting in an increased discharge of long-chain DNA during the first electrophoresis and a decrease in the obliquely backward discharge during the second electrophoresis (

Figure 4B,C). If some of the water in the gel film evaporated during in-gel swelling and proteolysis, the above effects were cancelled out, as shown in

Figure 1H; shrinkage of the pore size increased the number of fibers discharged obliquely backward during the second electrophoresis. Thus, detection of early symptoms of naturally occurring fragmentation is technically difficult, and the experimental procedures summarized in Table I were optimized for 0.4% agarose GB under careful moisture control. Even at the same concentration, commonly used high cross-linking preparations may produce false-negative results. When another preparation is used, careful and accurate control using PS is indispensable to ensure reproducibility. Particularly, the temperature for in-gel swelling and the concentration of agarose should be optimized to yield electrophoretic profiles similar to those obtained using 0.38% agarose GB.

6. DNA Cleavage Analyses

2D-SCPFGE has been developed as a diagnostic measure to observe the early symptoms of naturally occurring DNA fragmentation. All the efforts described in sections 3-5 were focused on not only how the enhancement of sensitivity but also the avoidance of artifactual fragmentation during in vitro processing.

To date, we have examined artificial cleavage of DNA by means of heat denaturation [

26], alkaline hydrolysis (section 4-2) [

22], Brownian motion (section 5-7) [

21], excitation by blue light (section 5-7) [

21], hydroxyl radicals produced via the Fenton reaction (section 6-1) [

48], DNase I [

26], and a restriction endonuclease (EcoRI; section 6-2) [

28]. We also noted that ice crystals generate fine mechanical damage that is detectable only via 2D-SCPFGE (section 5-5) [

28]. Naked long-chain fibers are extremely sensitive to chemical and physical factors; they are readily cleaved down to granular segments, mimicking end-stage fragmentation. Hence, to avoid artifactual cleavage, careful attention (see sections 3-5) is indispensable to observe the early symptoms of naturally occurring DNA fragmentation. In practical use, 1D-SCPFGE is a sufficiently sensitive tool for the detection of chemical cleavages, in which case the techniques described in sections 3-5 are optional. As the substrate for cleavage testing, the DNA integrity of the sperm population should be confirmed via 1D- or 2D-SCPFGE according to the required sensitivity.

Figure 5A shows the massed profiles of 2D-SCPFGE-0-150 for use in the substrate. All the sperm was deemed to be intact. The sample was preserved in the low-temperature liquid storage medium.

6.1. Dose-Dependent DNA Cleavage by Hydroxyl Radicals

AA produces hydroxyl radicals in the presence of transitional metals via the Fenton reaction [

45]. 1D-SCPFGE revealed that a single administration of sodium ascorbate (AA-Na) to sperm from which the plasma membrane was extracted with Triton X-100 promoted DNA fragmentation in a dose-dependent manner [

48], a mere 1.0 μmol/L AA-Na carved out various lengths of fibrous segments long-chain fibers. As the concentration of AA-Na was increased, fibrous segments became shorter and the number of granular segments increased. Ultimately, almost all the fibers were degraded into granular segments and the mass at the origin was diminished at 100 μmol/L AA-Na. This degradation was completely suppressed in the presence of 0.5 mmol/L EDTA 2Na. A single administration of AA-Na did not result in cleavage of the naked DNA fibers, whereas the addition of 0.5 mmol/L CuSO

4 promoted the action. The co-administration of 1.0 mmol/L ED completely inhibited the action of AA-Na and CuSO

4 [

48].

When discussing the impact of ROS on cellular functions, including DNA integrity, we have to consider time, distance, and shielding, as ROS are short-lived and only oxidize a few molecules at the site of their formation. Exogenous AA reacts with transitional metals in the nucleus of plasma-membrane-extracted sperm, whereas swimming sperm enveloped with an intact plasma membrane are shielded from extracellular AA [

48]. As AA does not function as a pro-oxidant in the presence of EDTA, we used AA and EDTA as counter-ions of Tris to establish an antioxidative electrophoresis buffer (see section 5-6).

6.2. Convenience of 2D-SPFGE for Analyses of Enzymatic DNA Cleavage

In macroscopic PFGE, the activity of proteinase K is terminated with phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride prior to the application of restriction endonucleases. As proteinase K is washed out from the gel film during the first electrophoresis in 2D-SCPFGE, enzymatic DNA cleavage can be observed without the need to inhibit proteinase K. Naked DNA fibers are preferable as the enzymatic substrate to avoid steric hindrance caused by the tightly packed DNA–nucleoproteins complex [

28]. For the control, a bundle of long-chain fibers is elongated during the first electrophoresis of 2D-SCPFGE-0-75 (3/3 min). In the second electrophoresis, those fibers are elongated obliquely forward and aligned to each other without overlapping (

Figure 5B). For the test sample, the glass slide is ejected after the first electrophoresis and the enzyme solution is mounted on the gel film. The segments are elongated obliquely forward, and the first electrophoresis served as proof that they were newly generated from the long-chain fibers. We previously reported the dose-dependent action of EcoR1 [

28]. When treated with 27.7 U/mL EcoR1, almost all the long-chain fibers elongated during the first electrophoresis were cleaved into segments of diverse sizes (

Figure 5C). As the concentration of endonuclease was increased, the size of segment fibers were cleaved into shorter fragments. For DNA-cleaving enzymes that require divalent cations, EDTA in the electrophoresis buffer must be trapped. For instance, when the action of DNase I is investigated, excess MgCl

2 and CaCl

2 may be used in the designated reaction buffer to trap EDTA. Under those circumstances, DNase I digests all the long fibers into granular segments without preconditioning. In general, the electrophoresis buffer should be removed prior to examination of enzymatic activity.

7. Preparation of Huge DNA Segments to Mimic Early-Stage Fragmentation for 2D-SCPFGE

The current 2D-SCPFGE protocol is the most sensitive method to visualize single-nuclear DNA fibers. In theory, the longest segments arise from chromosome 1 being cleaved in half; however, whether such long segments can be separated using this protocol remains unclear. To determine its limit of separation, a set of chromosomal-level DNA fibers are required as calibration standards. We planned to use prokaryotic DNA fibers as calibration standards for 2D-SCPFGE, but they were too short to adopt as size markers for very large eukaryotic DNA segments (

Figure 5D). Such standards would have to be prepared via artificial cleavage of PS. At present, no such procedure exists. Until such standards can be prepared, 2D-SCPFGE will remain a semiquantitative analysis for early-stage fragmentation. We tentatively propose 2D-SCPFGE as a reasonably accurate method to determine DNA sequentiality, and sperm without long DNA segments in the ROI after image processing may be defined as “intact.”

8. Future Work – Telomeric Ends and Cut Ends

Although 2D-SCPFGE was developed to separate huge DNA segments, with one or more angle rotations yielding various 2D-alignments of DNA fibers [

28]. We are exploring a novel approach for DNA fragmentation analysis. Fluorescent

in situ hybridization (FISH) enables mapping of specific DNA sequences in metaphase chromosomes and interphase nuclei. FISH on naked DNA fibers yields the highest mapping resolution. The alignment of long-chain fibers without overlapping is the first step of our research endeavor.

Figure 6A shows the profile of a set of single-nuclear DNA fibers generated via 2D-SCPFGE-(-75)-0 (3/5 min). The elongated long chain fibers were aligned laterally without overlapping.

Figure 6B shows our preliminary experiment with telomeric FISH. The repeat sequence of human telomeres [

52] was visualized via peptide nucleic acid (PNA) FISH. PNA is a nucleobase oligomer in which the entire backbone has been replaced by a backbone composed of

N-(2-aminoethyl) glycine units. It can be used to identify specific DNA and RNA sequences, binding via strand invasion and forming a stable PNA/DNA/PNA triplex with a looped-out DNA strand [

53]. The disseminated fluorescent signals suggested that the swollen DNA mass hybridized with the PNA telomere probe. The fluorescent signals at the tips of the fibers represent the telomeric ends, and ends without such signals represent the cut ends (

Figure 1I). Human sperm has 46 telomeric ends, the cut ends increase as the chromosomes are cleaved into more segments. After alignment of a set of single-nuclear long-chain fibers, we deemed sperm with at least one cut end as damaged. The biggest unsolved technical problem is the solid-phase fixation and stabilization of such fibers. As elongated naked DNA is very fragile in an aqueous solution, it cannot tolerate the hybridization process. We have observed that certain non-aqueous solvents, such as ethylene glycol (section 5-5) and DMSO (section 5-7), are effective in stabilizing the sequence. DMSO is often employed to lower the melting point of DNA molecules to facilitate hybridization in FISH. If the DNA is cleaved somewhat during the labeling process, the position of the telomeric region can still be identified. This technique may develop into a highly sensitive method to detect the early symptoms of DNA fragmentation.

9. Remarks on Basic and Clinical Studies

As illustrated in the present review, the quantification of naturally occurring early-stage fragmentation is technically challenging, it is essential to establish the detailed instructions to exclude false-positive and -negative. We accumulated technical competencies for various steps of 2D-SCPFGE to optimize its quantitative performance. In-gel proteolyzed naked DNA is eligible as a test specimen, they are, however, susceptible to ROS, and antioxidants are necessary to avoid artifactual sequential damages in vitro. Unexpectedly, cryopreservation also induced artifacts. Although the updated protocol for 2D-SCPFGE was refined from the former protocol, it remains a semiquantitative analysis technique.

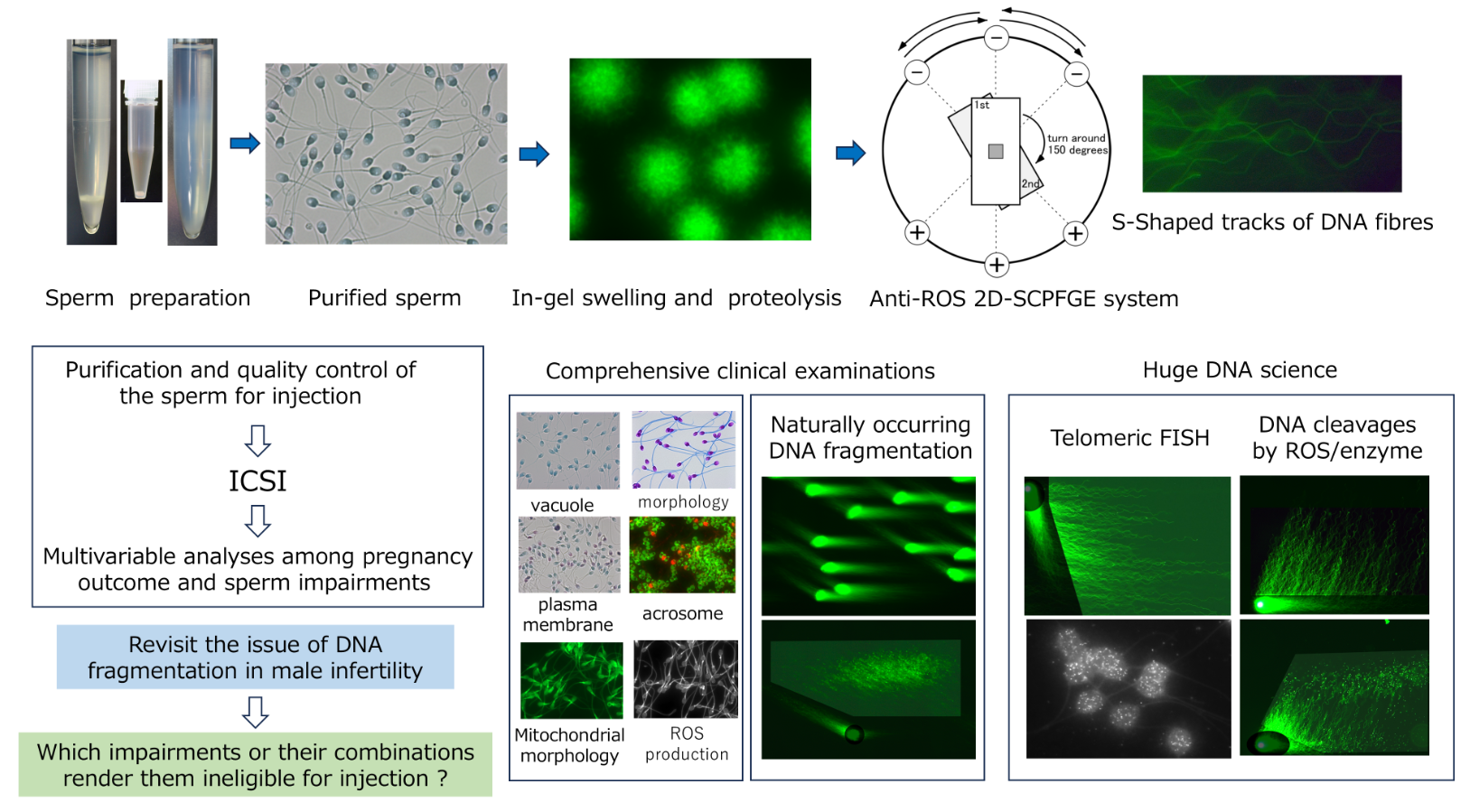

For many years, intraoperative sperm selection in ICSI usually depended on gross morphology and motility under bright-field optics. We have developed several preoperative clinical examinations besides 2D-SCPFGE: sperm-specific dye- and lectin-exclusion assays for the assessment of plasma and acrosomal membranes [

24]; dye-retention assays for the assessment of mitochondrial organelle membranes and endogenous ROS in the mitochondria [

24]; and visualization of vacuoles in the sperm head [

54,

55]. Investigations using these techniques highlighted that the separated motile sperm often had various impairments besides DNA damage. Therefore, the eligibility criteria for injectable sperm in clinical ICSI has become more complex, as such impairments cannot be detected via bright-field optics.

To date, many cohort studies have concluded that DNA damage is a major factor in fertilization, post-implantation embryo development [

12], and sperm-derived congenital anomalies in ART [

13]. Those conclusions were, however, derived from the conventional methods (see section 4). The fundamental framework of preoperative sperm examination is the clarification of which impairments or their combinations in the motile sperm render them ineligible for injection. This highlights the importance of a multifaceted approach. Cohort studies should contain well-designed, multivariable analyses with special consideration of confounding factors. Further accumulation of technical competencies, not only for 2D-SCPFGE, but also for other techniques are urgent tasks, as it will enable us to revisit the issue of male infertility and DNA fragmentation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.K. and Y.O.; methodology, S.K. and Y.O.; validation, S.K. and Y.O.; formal analysis, S.K. and Y.O.; investigation, S.K. and Y.O.; resources, S.K. and Y.O.; data curation, S.K. and Y.O.; writing—original draft preparation, S.K. and Y.O.; writing—review and editing, S.K. and Y.O.; visualization, S.K. and Y.O.; supervision, S.K. and Y.O.; project administration, S.K. and Y.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This review referred our previous reports, the institutional review board statements and the approvals were written in each article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed in the present study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare the absence of any conflicting interests.

References

- Acuna-Hidalgo, R.; Veltman, J.A.; Hoischen, A. New insights into the generation and role of de novo mutations in health and disease. Genome Biol 2016, 17, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricci, G.; Perticarari, S.; Fragonas, E.; Giolo, E.; Canova, S.C.; Pozzobon, C.S.; Guaschino, S.G.; Presani, G. Apoptosis in human sperm: Its correlation with semen quality and the presence of leukocytes. Hum Reprod 2002, 17, 2665–2672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakanishi., Y.; Shiratsuchi, A. Nakanishi. Y.; Shiratsuchi, A. Phagocytic Removal of Apoptotic Spermatogenic Cells by Sertoli Cells: Mechanisms and Consequences. Biol Pharma Bull 2004, 27, 13–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Middelkamp, S. ; Van Tol, Helena, T.A.; Spierings, D.; Boymans, S.; Guryev, V.; Roelen, B.; Lansdorp, P.; Cuppen, E.; Kuijk, E. Sperm DNA damage causes genomic instability in early embryonic development. Sci Adv 2020, 6, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchetti, F.; Essers, J.; Kanaar, R.; Wyrobek, A.J. Disruption of maternal DNA repair increases sperm-derived chromosomal aberrations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007, 104, 17725–17729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hehir-Kwa, J.Y.; Rodríguez-Santiago, B.; Vissers, LE.; de Leeuw, N.; Pfundt, R.; Buitelaar, J.K.; Pérez-Jurado, L.A.; Veltman, J.A. De novo copy number variants associated with intellectual disability have a paternal origin and age bias. J Med Genet 2011, 48, 776–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tubbs, A.; Nussenzweig, A. Endogenous DNA damage as a source of genomic instability in cancer. Cell 2017, 168, 644–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atamna, H.; Cheung, I.; Ames, B.N. A method for detecting abasic sites in living cells: Age-dependent changes in base excision repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2000, 97, 686–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borlè, MT. Formation, detection, and repair of AP sites. Mutation Res 1987, 181, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Gent, D.C.; Hoeijmakers, J.H.; Kanaar, R. Chromosomal stability and the DNA double-stranded break connection. Nat Rev Genet 2001, 2, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceccaldi, R.; Rondinelli, B.; D’Andrea, A.D. Repair pathway choices and consequences at the double-strand break. Trends Cell Biol 2016, 26, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borini, A.; Tarozzi, N.; Bizzaro, D.; Bonu, M.A.; Fava, L. Sperm DNA fragmentation: Paternal effect on early post-implantation embryo development in ART. Hum Reprod 2006, 21, 2876–2881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wennerholm, U.B.; Bergh, C.; Hamberger, L.; Lundin, K.; Nilsson, L.; Wikland, M.; Källén, B. Incidence of congenital malformations in children born after ICSI. Hum Reprod 2000, 15, 944–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tice, R.R.; Agurell, E. ; Anderson. D.; Burlinson, B.; Hartmann, A.; Kobayashi, H.; Miyamae, Y.: Rojas, E.; Ryu, J.C.; Sasaki, Y.F. Single cell gel/comet assay: Guidelines for in vitro and in vivo genetic toxicology testing. Environ Mol Mutagen 2000, 35, 206–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olive, P.L.; Banáth, J.P. The comet assay: A method to measure DNA damage in individual cells. Nat Protoc 2006, 1, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evenson, D.P. The sperm chromatin structure assay (SCSA®) and other sperm DNA fragmentation tests for evaluation of sperm nuclear DNA integrity as related to fertility. Anim Reprod Sci 2016, 169, 56–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Brakel, J.; Dinkelman-Smit, M.; de Muinck Keizer-Schrama, S.M.P.F.; Hazebroek, F.W.J.; Dohle, G.R. Sperm DNA damage measured by sperm chromatin structure assay in men with a history of undescended testes. Andrology 2017, 5, 838–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández, J.L.; Muriel, L.; Rivero, M.T.; Goyanes, V.; Vazquez, R. The sperm chromatin dispersion test: A simple method for the determination of sperm DNA fragmentation. J Androl 2003, 24, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández, J.L.; Johnston, S.; Gosálvez, J. Sperm chromatin dispersion (SCD) assay. In A Clinician’s Guide to Sperm DNA and Chromatin Damage; Zini A, Agarwal A. (eds), Springer Nature: Barling, AR, USA, 2018 pp.137-152.

- Crowley, L.C.; Brooke, J.; Marfell, B.J.; Waterhouse, N.J. Detection of DNA Fragmentation in Apoptotic Cells by TUNEL. Cold Spring Harb Protoc 2016, pdb.prot087221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaneko, S.; Takamatsu, K. Re-evaluation of Sperm Chromatin Structure Assay (SCSA). J Med Diagn Methods 2023, 12, 399. [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko, S.; Takamatsu, K. Revalidation of the sperm chromatin dispersion test and the comet assay using intercomparative studies between purified human sperm without and with end-stage DNA fragmentation. J Med Diagn Methods 2023, 12, 406. [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko, S.; Takamatsu, K. Re-Evaluation of Significance of Anti-Sperm Antibodies in Clinical Immune Infertility-Antigenicity of Human Sperm Diminishes during DNA Fragmentation. J Med Diagn Methods 2023, 12, 439. [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko, S.; Okada, Y.; Takamatsu, K. Sperm Specific Two-Step Dye Exclusion Assays to Evaluate Integrity of Plasma and Organelle Membranes-New Approach for Quality Assurance of the Sperm for Intra-Cytoplasmic Sperm Injection. J Med Diagn Methods 2024, 12, 450. [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko, S.; Okada, Y. Revalidation of DNA Fragmentation Analyses for Human Sperm - Measurement Principles, Comparative Standards, Calibration Curve, Required Sensitivity, and Eligibility Criteria for Test Sperm. Biology 2024, 13, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaneko, S.; Yoshida, J.; Ishikawa, H.; Takamatsu, K. Single-cell pulsed-field gel electrophoresis to detect the early stage of DNA fragmentation in human sperm nuclei. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e42257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaneko, S.; Yoshida, J.; Ishikawa, H.; Takamatsu, K. (1) Single-nuclear DNA instability analyses by means of single-cell pulsed-field gel electrophoresis - Technical problems of the comet assay and their solutions for quantitative measurements. J Mol Biomark Diagn 2013, S5, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, S.; Takamatsu, K. Angle modulated two-dimensional single cell pulsed-field gel electrophoresis for detecting early symptoms of DNA fragmentation in human sperm nuclei. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, D.C.; Cantor, C.R. Separation of yeast chromosome-sized DNAs by pulsed field gradient gel electrophoresis. Cell 1984, 37, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaufmann, M.E. Pulsed-Field Gel Electrophoresis. Molecular Bacteriology; Woodfold. N.; Johnson, N.P. (eds), Springer Nature: Barling, AR, USA, Methods in Molecular Medicine 1998 15, pp. 33–50.

- Lopez-Canovas, L.; Martinez Benitez, M.B.; Herrera Isidron, J.A.; Flores Soto, E. Pulsed Field Gel Electrophoresis: Past, present, and future. Anal Biochem 2019, 573, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO laboratory manual for the examination and processing of human semen, sixth edition. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021 pp 20-25.

- Balhorn, R. The protamine family of sperm nuclear proteins. Genome Biol 2007, 8, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres-Flores, U.; Hernández-Hernández, A. The interplay between replacement and retention of histones in the sperm genome. Front Genet 2020, 11, 780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okada, Y. Sperm chromatin condensation: Epigenetic mechanisms to compact the genome and spatiotemporal regulation from inside and outside the nucleus. Genes Genet Syst 2022, 97, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagstrom, K.A; Meyer, B.J. Condensin and cohesin: More than chromosome compactor and glue. Nat Rev Genet 2003, 4, 520–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nickerson, J. Experimental observations of a nuclear matrix. J Cell Sci 2001, 114, 463–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaman, J.A.; Yamauchi, Y.; Ward, W.S. Function of the sperm nuclear matrix. Arch Androl 2007, 53, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ada Soler-Ventura, A.; Castillo, J.; de la Iglesia, A.; Jodar, M.; Barrachina, F.; Ballesca, J.L.; Oliva, R. Mammalian sperm protamine extraction and analysis, a step-by-step detailed protocol and brief review of protamine alterations. Protein Pept Lett 2018, 25, 424–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebeling, W.; Hennrich, N.; Klockow, M.; Metz, H.; Orth, H.D.; Lang, H. Proteinase K from Tritirachium album Limber. Eur J Biochem 1974, 47, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawlings, N.D.; Barrett, A.J. Families of serine peptidases. Methods Enzymol 1994, 244, 19–61. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jameson, G.W.; Elmore, D.T. Affinity chromatography of bovine trypsin. A rapid separation of bovine α- and β-trypsin. Biochem J 1974, 141, 555–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomatsuri, N.; Yoshida, N. ; Takagi, T; Katada, K.; Isozaki, Y.; Imamoto, E.; Uchiyama, K.; Kokura, S.; Ichikawa, H.; Naito, Y.; et.al. Edaravone, A Newly Developed Radical Scavenger, Protects against Ischemia-reperfusion Injury of the small Intestine in Rats. Int J Mol Med 2004, 13, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pérez-González, A.; Annia Galano, A. OH Radical Scavenging Activity of Edaravone: Mechanism and Kinetics. J Phys Chem B 2011, 115, 1306–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, R.C.; Bode, A.M. Biology of free radical scavengers: an evaluation of ascorbate. FASBEJ 1993, 7, 1135–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amekura, S.; Shiozawa, K.; Kiryu, C.; Yamamoto, Y.; Fujisawa, A. Edaravone, a scavenger for multiple reactive oxygen species, reacts with singlet oxygen to yield 2-oxo-3-(phenylhydrazono)-butanoic acid. J Clin Biochem Nutr 2022, 70, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tokumaru, O.; Shuto, Y.; Ogata, K.; Kamibayashi, M.; Bacal, K.; Takei, H.; Yokoi, I.; Kitano, T. Dose-dependency of multiple free radical-scavenging activity of edaravone. J Surg Res 2018, 228, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaneko, S.; Yoshida, J.; Takamatsu, K. Direct visualization of ascorbic acid inducing double-stranded breaks in single nuclear DNA using single-cell pulsed field gel electrophoresis. Indian J App Res 2015, 5, 248–252. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, J.; Griffiths, P.T.; Campbell, S.J.; Utinger, B.; Kalberer, M.; Paulson, S.E. Ascorbate oxidation by iron, copper and reactive oxygen species: review, model development, and derivation of key rate constants. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 7417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Q.; Jockusch, S.; Zhou, Z.; Blanchard, S.C. The contribution of reactive oxygen species to the photobleaching of organic fluorophores. Photochem Photobiol 2014, 90, 448–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Repine, J.E.; Pfenninger, O.W.; Talmage, D.W.; Pettijohn, D.E. Dimethyl sulfoxide prevents DNA nicking mediated by ionizing radiation or iron/hydrogen peroxide-generated hydroxyl radical. PNAS 1981, 78, 1001–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moyzis, R.K.; Buckingham, J.M.; Cram, L.S.; Dani, M.; Deaven, L.L.; Jones, M.D.; Meyne, J.; Ratliff, R.L.; Wu, J.R. A highly conserved repetitive DNA sequence, (TTAGGG)n, present at the telomeres of human chromosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1988, 85, 6622–6626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shakeel, S.; Karim, S.; Ali, A. Peptide nucleic acid (PNA) - a review. J Chem Technol Biotechnol. [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, S.; Yoshida, J.; Takamatsu, K. Low density regions of DNA in human sperm appear as vacuoles after translucent staining with reactive blue 2. J Med Diagn Methods 2013, 2, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, S.; Okada, Y.; Yokota, S.; Takamatsu, K. Reactive Blue Dye: Highlights of Vacuoles in Human Sperm. J Med Diagn Methods 2023, 12, 400. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of long-chain fibers and fibrous and granular segments in 1D- and 2D-SCPFGE. A: In-gel proteolyzed DNA mass without in-gel swelling (former protocol). B: 1D-SCPFGE linearly arranged long-chain fibers and segments. The rectangular window beyond the tips of the elongated long-chain fibers shows ROI. If no segments was found in ROI, the former protocol was deemed to be sequentially intact. Fibrous segments (the red lines) remained entangled in the bundle of long-chain fibers, causing a false negative. C: End-stage fragmentation. D: CA lacks in-gel proteolysis and SPFGE, it cannot elongate the long-chain fibers, and smaller granular segments are observed compared with those in C. E: The original 2D-SCPFGE-0-150 without in-gel swelling. All the segments separated beyond the tips of the elongated long-chain fibers in the first electrophoresis were oriented obliquely backward and assembled in the polygonal window. F: DNA mass after simultaneous in-gel swelling and proteolysis, G: In the first electrophoresis, the swollen DNA mass discharged a greater number of long-chain fibers than that in E. H: Evaporation of some of the water in the gel film hindered all the efforts, number of fibers discharged obliquely backward were increased again. Thus, all of the processes should be performed in the moisture chamber to obtain the profile in G. I: Expected profile of telomeric analysis. The image illustrates the tip ends of a set of single-nuclear long-chain fibers aligned by means of 2D-SCPFE-(-75)-0. The telomeric regions are labeled with PNA-FISH. The fluorescent signal at the tips represents the telomeric end, and those without signals represent cut ends.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of long-chain fibers and fibrous and granular segments in 1D- and 2D-SCPFGE. A: In-gel proteolyzed DNA mass without in-gel swelling (former protocol). B: 1D-SCPFGE linearly arranged long-chain fibers and segments. The rectangular window beyond the tips of the elongated long-chain fibers shows ROI. If no segments was found in ROI, the former protocol was deemed to be sequentially intact. Fibrous segments (the red lines) remained entangled in the bundle of long-chain fibers, causing a false negative. C: End-stage fragmentation. D: CA lacks in-gel proteolysis and SPFGE, it cannot elongate the long-chain fibers, and smaller granular segments are observed compared with those in C. E: The original 2D-SCPFGE-0-150 without in-gel swelling. All the segments separated beyond the tips of the elongated long-chain fibers in the first electrophoresis were oriented obliquely backward and assembled in the polygonal window. F: DNA mass after simultaneous in-gel swelling and proteolysis, G: In the first electrophoresis, the swollen DNA mass discharged a greater number of long-chain fibers than that in E. H: Evaporation of some of the water in the gel film hindered all the efforts, number of fibers discharged obliquely backward were increased again. Thus, all of the processes should be performed in the moisture chamber to obtain the profile in G. I: Expected profile of telomeric analysis. The image illustrates the tip ends of a set of single-nuclear long-chain fibers aligned by means of 2D-SCPFE-(-75)-0. The telomeric regions are labeled with PNA-FISH. The fluorescent signal at the tips represents the telomeric end, and those without signals represent cut ends.

Figure 2.

Schematic illustration of the round electrophoresis tank and rotation of the rack for 2D-SCPFGE-0-15. Centrifugal auto-smearing was used to adhere human sperm to a 5 × 5 mm area of the agarose-coated glass slide. The important technical aspect is the positioning of this area exactly on the intersection point of the three currents. Positioning error causes deformation of the electrophoretic profiles. The long-chain fibers migrate in S-shaped curves according to the switching intervals. Scale bars represents 10 µm.

Figure 2.

Schematic illustration of the round electrophoresis tank and rotation of the rack for 2D-SCPFGE-0-15. Centrifugal auto-smearing was used to adhere human sperm to a 5 × 5 mm area of the agarose-coated glass slide. The important technical aspect is the positioning of this area exactly on the intersection point of the three currents. Positioning error causes deformation of the electrophoretic profiles. The long-chain fibers migrate in S-shaped curves according to the switching intervals. Scale bars represents 10 µm.

Figure 3.

The former protocol of D-SCPFGE-0-150 without in-gel swelling. A: After embedding, the agarose was immediately chilled on ice for 5 min, followed by in-gel proteolysis at 45 °C for 10 min. The tightly packed DNA mass was visible as a small, bright core. B: 2D-SCPFGE-0-150 elongated long-chain fibers in two directions, while the bright core remained at the origin. C: 1D-SCPFGE profile of the end-stage fragmentation in DS, D: 2D-SCPFGE profile of the end-stage fragmentation in DS. Scale bars represent 50 µm.

Figure 3.

The former protocol of D-SCPFGE-0-150 without in-gel swelling. A: After embedding, the agarose was immediately chilled on ice for 5 min, followed by in-gel proteolysis at 45 °C for 10 min. The tightly packed DNA mass was visible as a small, bright core. B: 2D-SCPFGE-0-150 elongated long-chain fibers in two directions, while the bright core remained at the origin. C: 1D-SCPFGE profile of the end-stage fragmentation in DS, D: 2D-SCPFGE profile of the end-stage fragmentation in DS. Scale bars represent 50 µm.

Figure 4.

The updated protocol of 2D-SCPFGE-0-150 with in-gel swelling. A: The agarose was kept at 37 °C for 5 min prior to chilling on ice, resulting in swelling of the sperm heads without free diffusion of the fibers. The bright core disappeared. The photographs B, C, and D show the typical profiles of DNA fragmentation. B: When compared with

Figure 3B, a larger number of long-chain fibers were discharged from the swelling mass during the first electrophoresis, those discharged obliquely backward at the second run were decreased. This is the typical profile of intact sperm, no segments were detected in the ROI. C: The typical profile of the early stage fragmentation, a few long fibrous segments were found in ROI. D: The typical profile of advanced stage fragmentation, various sizes of fibrous and granular segments were assembled in ROI. Scale bars represent 50 µm.

Figure 4.

The updated protocol of 2D-SCPFGE-0-150 with in-gel swelling. A: The agarose was kept at 37 °C for 5 min prior to chilling on ice, resulting in swelling of the sperm heads without free diffusion of the fibers. The bright core disappeared. The photographs B, C, and D show the typical profiles of DNA fragmentation. B: When compared with

Figure 3B, a larger number of long-chain fibers were discharged from the swelling mass during the first electrophoresis, those discharged obliquely backward at the second run were decreased. This is the typical profile of intact sperm, no segments were detected in the ROI. C: The typical profile of the early stage fragmentation, a few long fibrous segments were found in ROI. D: The typical profile of advanced stage fragmentation, various sizes of fibrous and granular segments were assembled in ROI. Scale bars represent 50 µm.

Figure 5.

Analyses of enzymatic DNA cleavage and prokaryotic DNA. A: The integrity of DNA for use as the substrate was validated by means of 2D-SCPFGE-0-150. B: 2D-SCPFGE-0-75 (3 /3 min), in which the long-chain fibers were aligned without overlapping. C: The gel was ejected from the rack after the first electrophoresis, mounted the reaction mixture (27.7 U EcoR1/mL in 50 μL of 50 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 100 mmol/L NaCl, 10 mmol/L MgCl2, and 1.0 mmol/L DTT), and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min in a moisture chamber. Thereafter, the slides were placed on the rack and rotated 75° for the second electrophoresis. Scale bars in A, B, and C represent 50 µm, respectively. D: The profile of prokaryotic DNA in 1D-SCPFGE. Some bacteria contaminated in a culture medium was added in PS. The photograph was taken as monochrome images to enhance the weak fluorescence. Scale bar represents 10 µm.

Figure 5.

Analyses of enzymatic DNA cleavage and prokaryotic DNA. A: The integrity of DNA for use as the substrate was validated by means of 2D-SCPFGE-0-150. B: 2D-SCPFGE-0-75 (3 /3 min), in which the long-chain fibers were aligned without overlapping. C: The gel was ejected from the rack after the first electrophoresis, mounted the reaction mixture (27.7 U EcoR1/mL in 50 μL of 50 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 100 mmol/L NaCl, 10 mmol/L MgCl2, and 1.0 mmol/L DTT), and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min in a moisture chamber. Thereafter, the slides were placed on the rack and rotated 75° for the second electrophoresis. Scale bars in A, B, and C represent 50 µm, respectively. D: The profile of prokaryotic DNA in 1D-SCPFGE. Some bacteria contaminated in a culture medium was added in PS. The photograph was taken as monochrome images to enhance the weak fluorescence. Scale bar represents 10 µm.

Figure 6.

2D-SCPFGE-(-75)-0 proposes a new perspective on DNA fragmentation analysis. A: Profile of a set of single-nuclear DNA fibers by means of 2D-SCPFGE-(-75)-0 (3/5 min). Scale bar represents 50 µm. B: PS were adhered to a plane glass slide and swollen with 5.0 mmol/L DTT, pH 9.0, for 5 min. The repeat sequence of human telomeres (TTAGGG) was visualized according to the FISH protocol provided in the peptide nucleic acid (PNA) FISH Telomere/FITC kit (Dako Cytomation, Glostrup, Denmark). Scale bar represents 10 µm.

Figure 6.

2D-SCPFGE-(-75)-0 proposes a new perspective on DNA fragmentation analysis. A: Profile of a set of single-nuclear DNA fibers by means of 2D-SCPFGE-(-75)-0 (3/5 min). Scale bar represents 50 µm. B: PS were adhered to a plane glass slide and swollen with 5.0 mmol/L DTT, pH 9.0, for 5 min. The repeat sequence of human telomeres (TTAGGG) was visualized according to the FISH protocol provided in the peptide nucleic acid (PNA) FISH Telomere/FITC kit (Dako Cytomation, Glostrup, Denmark). Scale bar represents 10 µm.

Table I.

Technical modifications of SCPFGE.

Table I.

Technical modifications of SCPFGE.

| |

Procedure, equipment |

Former protocol for 1D-SCPFGE |

Updated protocol for 2D-SCPFGE |

| 1 |

Usage |

DNA fragmentation analysis |

DNA fragmentation analysis

2D-alignment of DNA fibers |

| 2 |

Preparation for test sperm |

OptiPrep, Percoll density gradient, swim-up |

OptiPrep, Percoll density gradient, swim-up |

| 3 |

Storage of test sperm |

Cryopreservation in Hanks’ solution |

Low-temperature liquid storage |

| 4 |

Dilution of test sperm

|

Hanks’ solution |

Hanks’ solution, EDTA, ED |

| 5 |

Glass slide |

MAS-coated glass slide |

Agarose-coated glass slide |

| 6 |

Agarose for embedding |

Low melting point agarose, pH 4.7, EDTA, Triton X-100, trypsin |

low melting point agarose, pH 9.0, SDS,

EDTA, Proteinase K, DTT, ED |

| 7 |

In-gel swelling |

None |

Keep the gel in moisture chamber at 37 °C for 5 min |

| 8 |

Solidify agarose |

Immediately after embedding, chill in refrigerator for 30 min |

Chill on ice for 5 min |

| 9 |

In-gel proteolysis

|

hexa-metaphosphate or SDS, DTT, EDTA, pH 8.0, at 37 °C for 30 min |

Keep the gel in moisture chamber at 45 °C for 10 min |

| 10 |

Electrophoresis |

2 pairs of electrodes

Tris-acetate, pH 8.0

Pulsed-field current: 1.5-2.5 V/cm Switching interval: 4-8 s |

3 pairs of electrodes

Tris-EDTA-AA, pH 8.0

Pulsed-field current: 3.5 V/cm

Switching interval: 4 s |

| 11 |

Mode of separation |

Linearly arranged long-chain fibers and segments |

One or more angle rotations providing various 2D-alignments of DNA fibers |

| 12 |

DNA staining |

SYBR Gold in Hanks’ solution |

SYBR Gold in 50% DMSO |

| 13 |

Anti-DNA fragmentation |

None |

Tris-EDTA-AA, ED, DMSO |

| 14 |

Image processing |

None |

Digital brightening of DNA in ROI |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).