1. Introduction

The cenotaph dedicated to Antonio Canova, built by his students in 1827, had manifested some alteration features three decades after its construction. In particular, the alteration forms reported at that time concerned the formation of stains on the surfaces of the marble elements and some fractures in the lumachella stone coverings the basement of the monument [

1]. The first photographic documentation dates back to the beginning of XX century, during some important conservation works carried out to re-instate the stability of the monument. The survey of the conservation state of the monument had highlighted static problems and the presence of some yellowish and greyish areas (

Figure 1). At that time the marble surfaces were not affected by any material loss. In the last quarter of XX century some deterioration features have been observed. In particular some areas were affected by salt efflorescence and detachment of small surface pieces of marble. People responsible for the conservation of the monument decided to make a restoration intervention using acrylic resin without a preliminary identification of the causes of deterioration.

Almost two decades after the aforementioned restoration, the situation had further worsened (

Figure 2, a, b) and the Superintendence for Architectural and Landscape Heritage of Venice had planned to intervene with a conservation project that would be preceded by a diagnostic investigation aimed at understanding the causes that had significantly accelerated the further loss of marble surface portions.

It is important to point out that based on the consolidated experience gained from studies carried out since the 1970s in numerous Venetian churches and historic buildings, significant losses of material located at a certain height from the ground were observed [

2]. These alterations were generally due to the salt crystallization, whose saline species, in relation to their mobility, migrate vertically to different heights before crystallizing [

3,

4,

5,

6]. From measurements carried out in many Venetian buildings, salts deriving from chlorides and nitrates were found at greater heights than those deriving from sulphates due to their different mobility. Crystallization can occurs on the surface forming white efflorescences, or inside the substrate, nearby the surface, forming non visible salt crypto-efflorescences or sub-efflorescences [

7]. These last are more dangerous because growing inside the capillaries they exert a pressure on the capillary walls breaking them.

2. Previous Studies

Macroscopic observation of the frequent formation of droplets [

8,

9] on some areas of the group of sculptures led the authorities responsible for their conservation to plan a survey to investigate the microclimatic conditions that could be responsible of the phenomena observed (

Figure 3).

Measurements of surface temperature on different areas of the statues’ surfaces have revealed the slow change of surface temperature with respect to the surroundings air temperature fluctuations. The thinner parts of statues such as arms, legs and hands show a faster change of surface temperature in relation to sudden neighbouring air temperature fluctuations. One of the factors responsible of this behaviour is the ventilation which is lowering the surface temperature due to the heat exchange with the air of the church [

10].

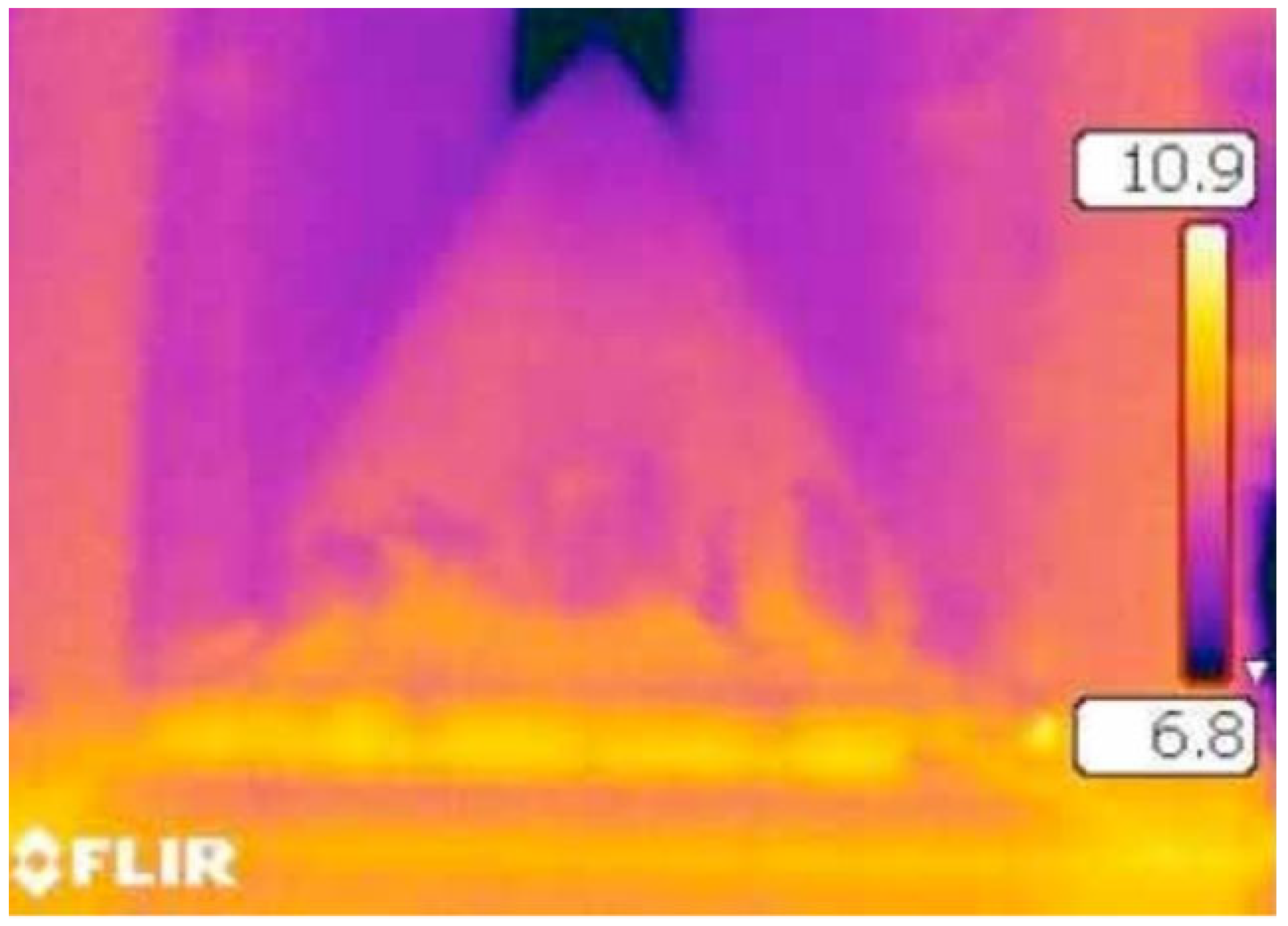

The thermal behaviour of the cenotaph was also investigated using a thermographic survey [

11]. Measurements of the pyramid basement and of the lower steps showed a higher temperature than the other areas and in particular the temperature decreased progressively with elevation from the church floor (

Figure 4).

This temperature decrease seems to be in relation with the reduction of the thickness of the monument structure. The higher temperature measured in correspondence to the pyramid basement (greater thickness) in contact with the church floor indicates that the heat source could be attributed to the presence of higher moisture content.

Another issue regarding the lower temperature of the statues compared to the supporting steps was taken into consideration. This different behaviour can be ascribed to the construction typology of the statues which have a lower mass with respect to the steps of the pyramid and consequently they have a lower humidity content.

Thermographic investigations of the roof and upper parts of vertical walls indicated that water infiltrations were absent [

11].

Thermographic survey, in a transient heating regime, was also carried out on the detachment areas visually observed. This technique allows us to individuate deterioration areas which were not visible because they are in a latent phase which precedes the detachment which will take place successively.

The most important finding from the above investigations was the monitoring of detachment areas which have a greater extension than those visually perceived, i.e., in some areas of the

Sleeping Genius’s head (

Figure 5a and

Figure 5b). These areas are characterised by a pronounced convexity (strongly curved surfaces) in which the more frequent evaporative cycles are taking place and they are responsible for a heavier deterioration process compared to the nearby flat areas or areas with a lesser degree of curvature [

2].

Microclimatic studies on the monument established that the droplet formation ascribed to condensation processes is not very frequent. According to these studies, biological colonization is responsible for the increase in volume which is detaching thin marble layers from the substratum [

10].

As this biological mechanism seemed not to be reliable, people responsible for the conservation asked for the reliability of this hypothesis to be verified.

Our diagnostic plan was designed to identify the causes of alteration taking into account the building construction techniques of the monument. In fact, many problems were probably related to the structure, which is supporting all the weight of the marble blocks of the steps, the pyramid and the sculptures. As the brick structure is in close contact with the moisture of foundations, it was also decided to investigate the water content in order to evaluate if the capillary rise is influencing the presence of water droplets on the marble surface (see

Figure 3) and if it may be related to salt efflorescence occurrence.

3. Present Survey

The investigations above discussed established that droplets formation could be ascribed to the migration of capillary rising damp in correspondence to high tide events. However, the droplets percolating on the surface did not show the formation of salts along the edges of their percolation path as it has been frequently observed in the church of Santa Maria dei Miracoli [

12,

13,

14,

15] (see

Figure 6). As the conclusions of previous studies were not explaining the sharp increase of deterioration processes observed in different areas, that has caused the loss of large pieces of marble details from the surface of the statues the Superintendence responsible of funerary monument conservation decided to carry out further investigations that could provide useful input for the preparation of the restoration project.

In order to satisfy this condition, our diagnostic plan was focused on studying the existence of capillary rise phenomenon in relation to the structure characteristics of the cenotaph. At the same time, it was investigated the reason why some areas are more damaged than other ones [

3].

It was surprising that the areas where droplets are present are not very damaged whereas some other parts have suffered serious damage. For instance, the chest of the

Sleeping Genius or the robes of the women (

Figure 2a,b), show the presence of salt crystals associated with a marked exfoliation of thin marble layers, while droplets present on the face of the

Sleeping Genius were not causing any damage.

4. Materials and Methods

Samples from decayed areas were taken following European standard EN 16085 [

16]: these were micro-flake samples, representative of the different forms of decay observed. Bulk samples for the measurement of moisture and salt content were also taken for investigations into the rising damp process.

Optical microscope (OM) and scanning electron microscope equipped with a dispersive energy micro-analyser (ESEM-EDS) were used for cross-section observation. The characterization of bulk samples was performed by X-ray diffraction (XRD), while X-ray fluorescence (XRF) with WDS sequential spectrometry was used for the elemental composition analysis. Anion concentrations such as sulphates, nitrates, chlorides and oxalates were measured by ion chromatography (IC) following the European standard EN 16455 [

17]. The morphological characteristics of micro-flake samples were observed by examining 3D samples using secondary electrons of scanning electron microscopy (SEM). The presence of organic compounds was determined by infrared spectroscopy FT-IR

5. Results

5.1. Structure Underlying Carrara Marble Statues and Steps and Related Moisture Content

In Venice the masonry brick structure of historic buildings and churches has an important role on the transmission of moisture from the foundations toward the marble applied as coverings of the brick structure.

As there were no information in the archives regarding the construction typology of the masonry structure it was necessary to make an inspection by removing the lumachella ashlars (

Figure 7) and by drilling the compact Istrian stone (thickness 22 cm) supporting the first marble step. The supporting structure of the marble monument is in direct contact with the foundations which in turn are in contact with the lagoon water (

Figure 7).

In order to ascertain the state of conservation of the cenotaph marbles, the moisture content in the structure behind the marble steps, on which the statues rest, was measured at various heights.

At the church floor bricks are completely saturated with a moisture content around 26%. This high-water content is maintaining constant up to 90 cm of elevation. Above this height, moisture content is decreasing slowly up to 140 cm of elevation. Above this eight, the water content is decreasing more rapidly and at the pyramid base (200 cm) it is reduced to 8.5%. Above pyramid base, at 235 cm of elevation, the moisture drops furtherly to 2-3%, that is corresponding to the maximum height of the capillary rise front (

Figure 8).

The data obtained indicated that the brick supporting structure is completely water saturated and as there are no discontinuity between the brick structure and the marble blocks or statues the capillary rising damp process is causing the migration of salts from brick structure towards the external marble surfaces.

In contrast with the high moisture content of the brick structure the Istrian stone blocks, in contact with the brick structure, have a very low moisture content, approximately 50 times lower. This is due to the different porosity of the two materials. From the measurements taken, it is clear that the very porous brick structure is close to saturation. Moisture drops dramatically in the Istrian stone blocks (22 cm thickness) because the latter, having a very low porosity, absorbs limited quantities of water. The same happens for marble. The larger extension of deterioration areas is localised approximately from 150 to 250 cm.

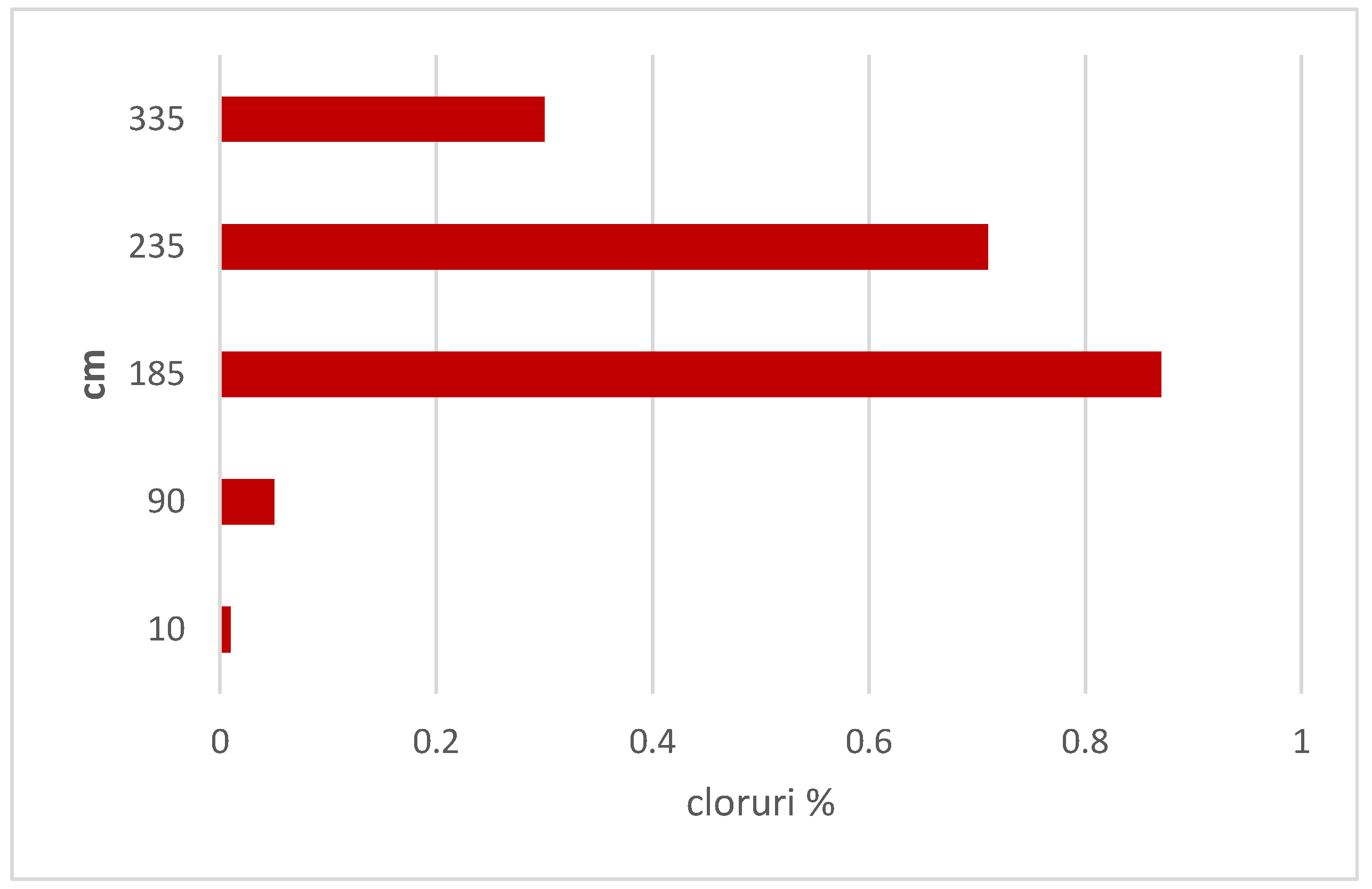

Regarding the salt content, chlorides and nitrates are present in higher quantities than sulphates and migrate vertically to higher heights than sulphates, due to their higher mobility and thus confirming the results obtained in other cases studied [

7]. Furthermore, there is an increasing concentration of chlorides towards the external surface in accordance with the lower moisture content measured (

Figure 9). From the data the capillary rise phenomenon is active up to an elevation of approximately 180-250 cm where the solution is enriched in chlorides near the surface and sodium chloride crystallizing is causing exfoliation and disintegration of surface marble layer.

5.2. Macroscopic Features of Marble Surface

Water migration in the capillary brick structure transports ions coming from the cenotaph foundations and the driving force responsible for the rise is progressively counterbalanced by water vapour evaporation. With elevation the driving force is decreasing and at a certain level the capillary rise front is stopping because the driving rising force is completely counterbalanced by the water vapour evaporation rate and the ion concentration in the solution is reaching the oversaturation conditions with consequent salt crystallization nearby the surface. The increase in volume of the crystals exerts considerable pressure in the capillaries close to the surface, causing the breaking of their walls with the detachment of thin marble flakes, followed by a progressive disintegration of the marble’s calcite crystals. Depending on the structure and texture of the material, subject to this mechanical action, exfoliation and detachment of thin marble layers take place [

2].

The observed alteration features can be grouped according to the following classification:

-

a)

Rough whitish areas. The surface of the marble is rough, opaque and generally the white-grey marble surface is turning to whitish due to the change of refractive index consequent to the formation of exogeneous crystals responsible of the detachment of thin marble layers. These alteration features are present quite widely on the marble steps and on some areas of the sculptures (

Figure 10).

-

b)

Areas with exfoliation of superficial marble scales. The alteration process is more advanced than the above described and exfoliation of superficial marble layers is detaching from the substrate (

Figure 11).

-

c)

Areas with missing portions of marble. This is a more advanced decay in which the material has already detached. These visible deterioration forms are present on the

Sleeping Genius (

Figure 2 a), on the statues of

Painting and

Architecture (Figure 2 b) and on some parts of the steps.

-

d)

Areas with reddish circular spots (

Figure 12). These appear localized in some areas and the surface is rough and opaque as in the whitish areas before described (

Figure 10).

-

e)

Areas of surface turning to greyish characterized by marble smooth surface without any evident alteration (

Figure 13).

5.3. Optical and Scanning Electron Microscope Analyses

In order to explain the different alteration features before described some small samples were taken from the different areas and analysed at the optical and scanning electron microscope.

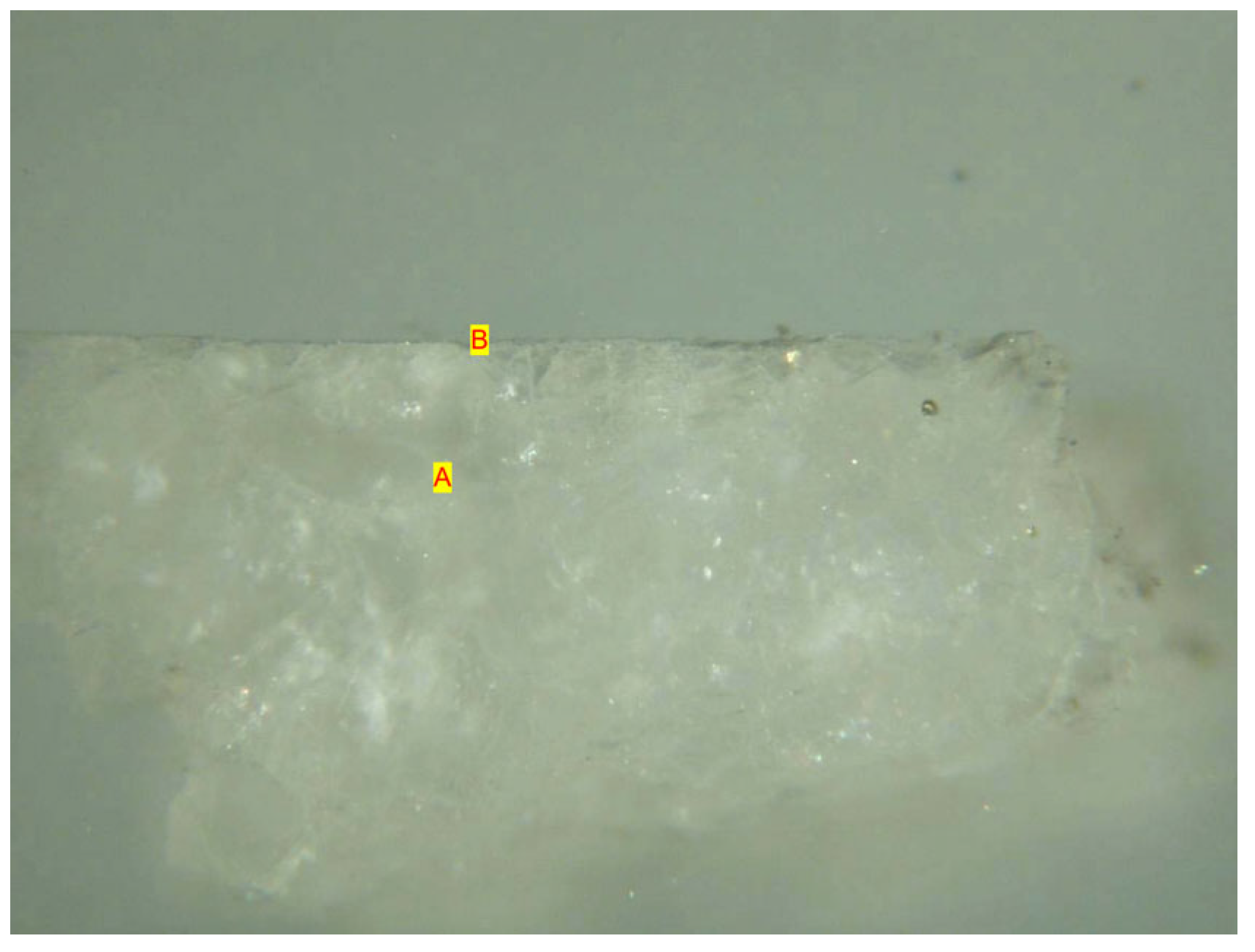

Type a) Rough and whitish areas (

Figure 10). Cross-sections analyses show a fair amount of interstitial micro-cracks caused by the sodium chloride crystallization. This is the initial stage of deterioration in which calcite crystals detach from each other and the structure becomes less compact and the marble appearance change from white-grey to whitish colour (

Figure 14a,b).

In some areas the intergranular interstices had extended longitudinally to form a line of discontinuity almost parallel to the external surface (

Figure 15). This stage represents a level that precedes exfoliation of thin marble layers.

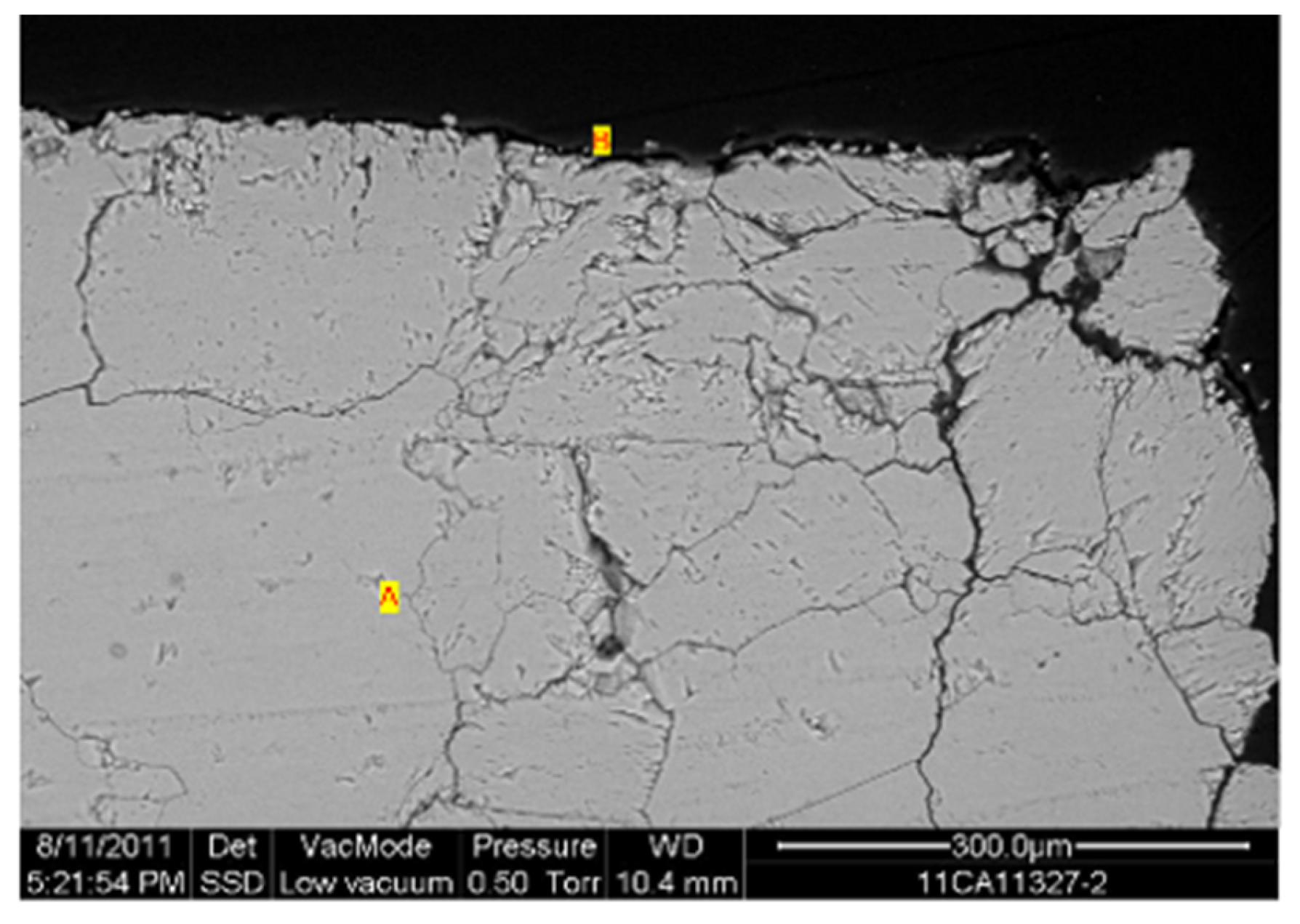

Type b) Areas with exfoliation of superficial marble scales (multilayer). A progressive marble detachment flakes is observed (

Figure 11 and

Figure 16). Examination of a cross-section of a multilayer exfoliation scale shows eleven flake layers (

Figure 16). Among the various layers sodium chloride crystals were detected and they are responsible for the scale’s detachment. Microanalysis also emphasize the presence of potassium chloride and gypsum.

Figure 16.

Multilayer exfoliation of marble. Enlargement of

Figure 11.

Figure 16.

Multilayer exfoliation of marble. Enlargement of

Figure 11.

Figure 17.

Cross-section at SEM. Eleven layers were observed. The black layer on the top is ascribed to a wax treatment, the first layer is 480 µm thick and all the subsequent layers are about 300 µm each one. The total thickness is about 3 mm.

Figure 17.

Cross-section at SEM. Eleven layers were observed. The black layer on the top is ascribed to a wax treatment, the first layer is 480 µm thick and all the subsequent layers are about 300 µm each one. The total thickness is about 3 mm.

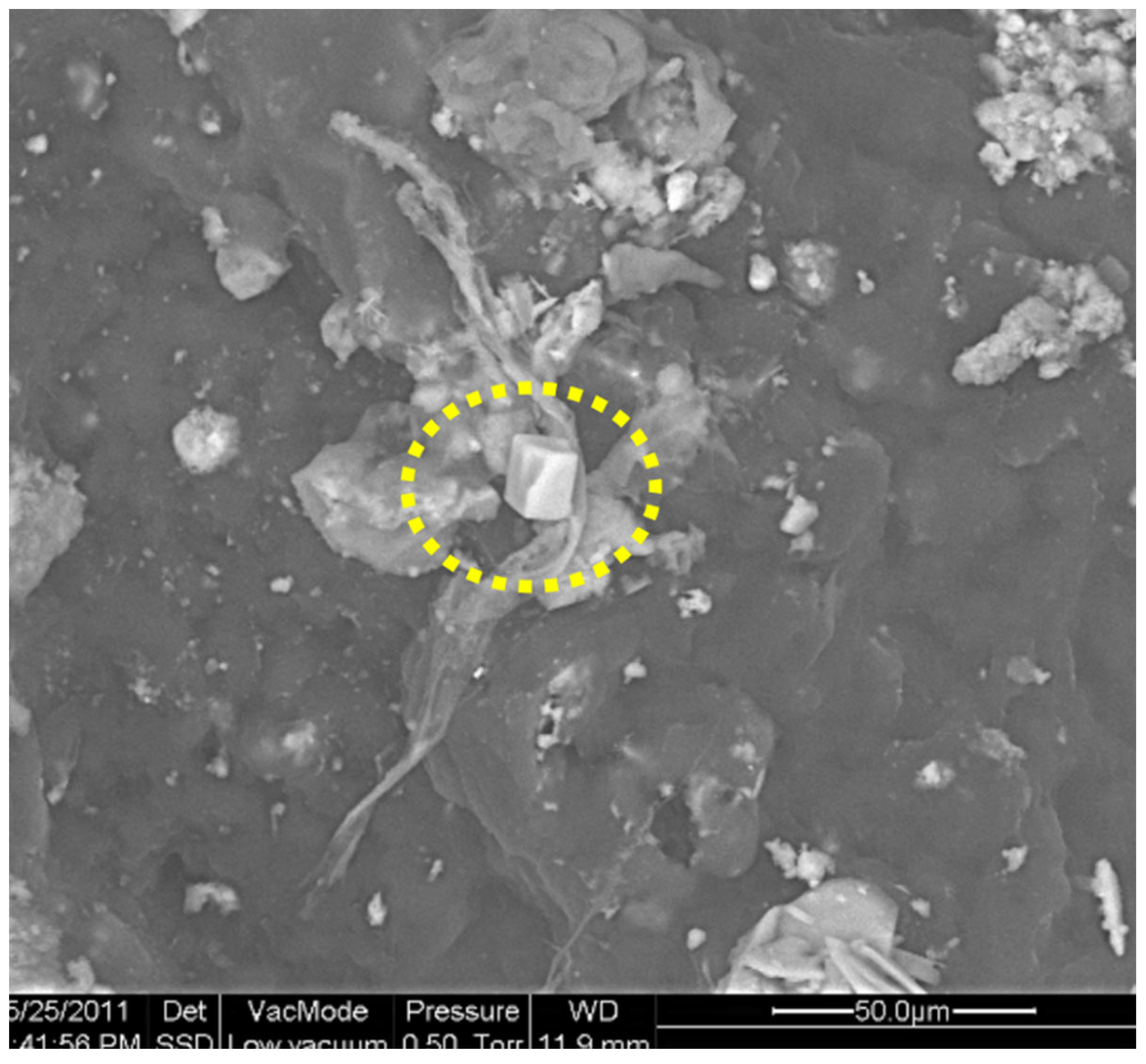

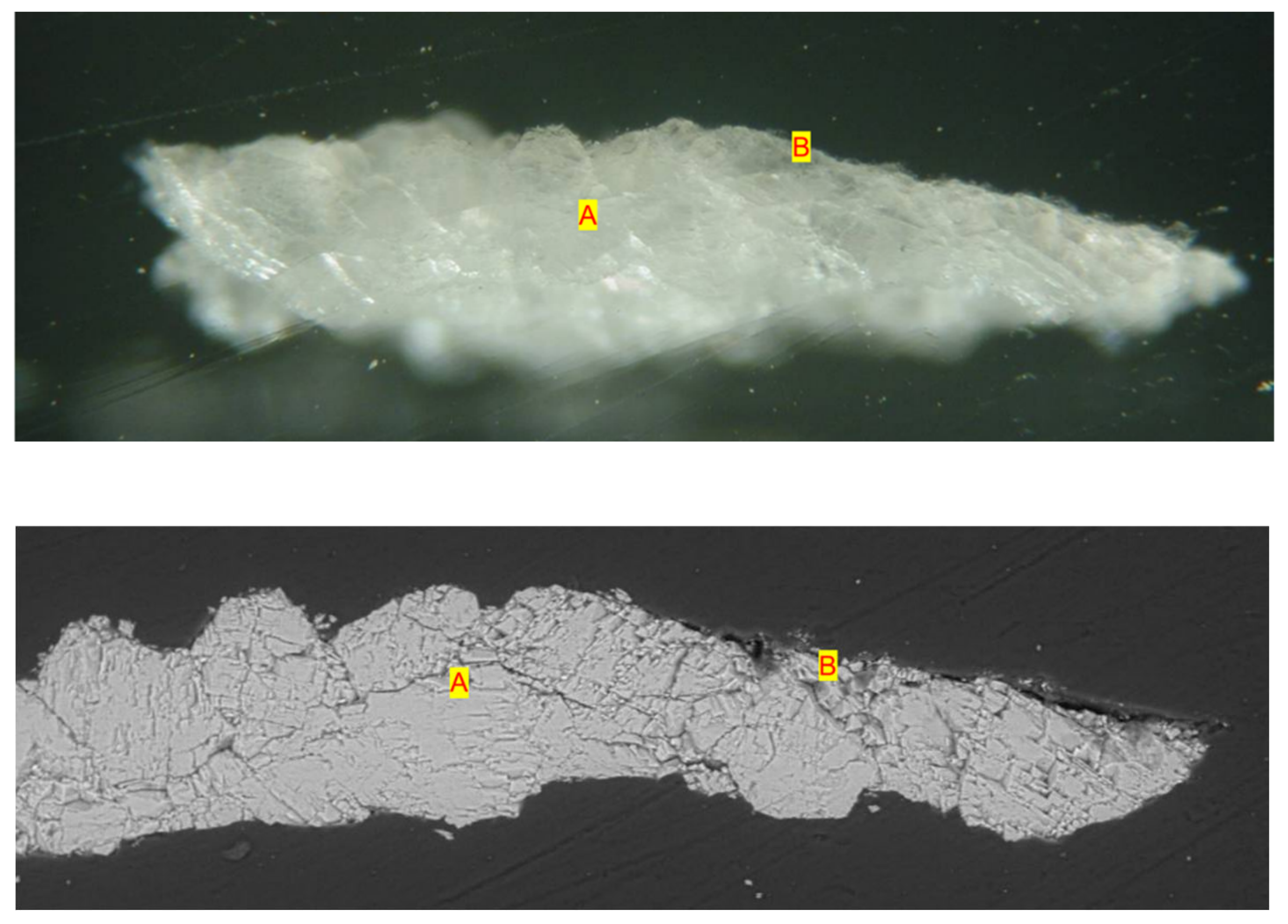

Sodium chloride crystals were observed in between the exfoliation layer (Figure 18 and Figure 19). They are responsible of detachment of thin marble layer.

Figure 18.

SEM analysis of the surface. Sodium chloride crystals, inside the yellow circle, are visible.

Figure 18.

SEM analysis of the surface. Sodium chloride crystals, inside the yellow circle, are visible.

Figure 19.

a) SEM observation of cross-section exfoliation scale. In the yellow circle sodium chloride crystals growing in between the exfoliation layers; b) The same crystals at higher enlargement. The crystal growing is responsible of the scale detachment.

Figure 19.

a) SEM observation of cross-section exfoliation scale. In the yellow circle sodium chloride crystals growing in between the exfoliation layers; b) The same crystals at higher enlargement. The crystal growing is responsible of the scale detachment.

Type d) Areas with reddish circular spots (

Figure 12). The presence of hydrated iron oxides was identified, most likely generated by oxidation of iron linchpin that were used to fix the marble blocks. According to some authors iron is firstly oxidized to ferrous ion (Fe II), which in presence of moisture is forrming a mixture of ferrous and ferric hydroxide. The hydrated iron oxide migrating in the carbonate substrate reacts with carbonate anions of the matrix forming colloidal oxy-hydroxy ferric carbonate Fe

(III)6 O

(2+X) (OH)

(12+2x) · (H

2O)x (CO

3), which in turn diffuses through the carbonate matrix and when it reaches to saturation condition a red precipitate of lepidocrocite (γFeOOH) takes place (18-20). A radial diffusion of these colloidal solution give the red-orange circular sposts (

Figure 12), often with particular shapes, such as Liesegang rings [21]. The formation of Liesegang rings represent a phenomenon of periodic precipitation, observed both in simulated chemical systems constituted by ions scattered in a colloidal medium in gel state, and in natural systems (sedimentary rocks). Such phenomenon causes the formation of colored ring bands more or less regular. At the optical micrscope the colloidal iron oxides is diffusing in the crystal intertices and covering calcite crystal (Figure 20).

Figure 20.

Iron oxide colloidal compounds are responsible of the red-orange colour visible.

Figure 20.

Iron oxide colloidal compounds are responsible of the red-orange colour visible.

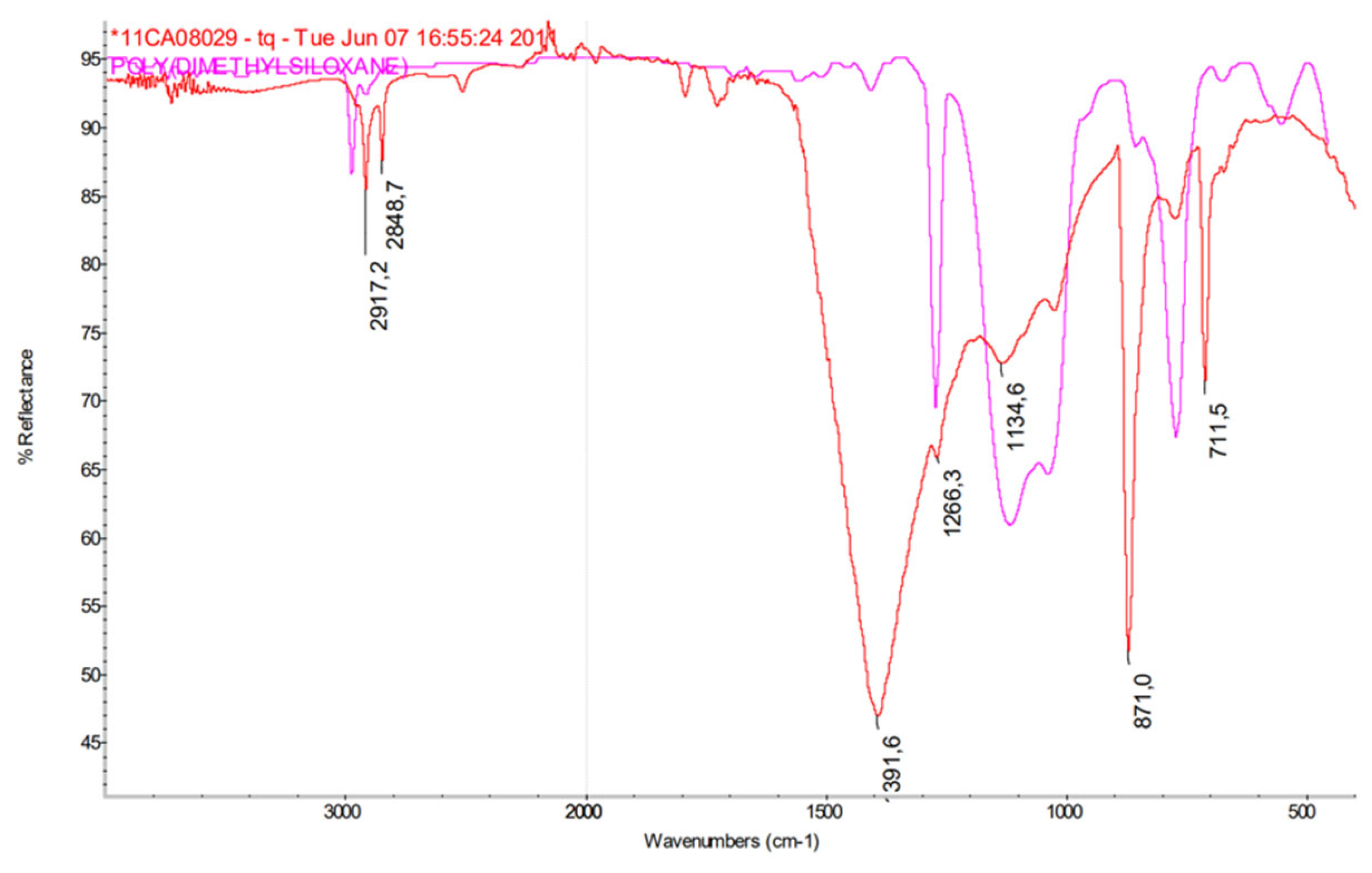

Type e) Areas of surface turning to greyish (

Figure 13). The cross-section optical microscopic observation shows a compact internal structure which indicates a good state of conservation. On the surface, the presence of wax (Figure 21) and traces of acrylic and siloxane compounds was found (Figure 22). The wax is probably ascribed to ancient treatments, while the synthetic products are ascribed to the 1993 intervention and to some maintenance not present in the archive documents.

Figure 21.

SEM observation of the surface. A grey dark non-crystalline organic-based layer is covering the marble surface. In the yellow circle a sodium chloride crystal has broken the organic-based layer.

Figure 21.

SEM observation of the surface. A grey dark non-crystalline organic-based layer is covering the marble surface. In the yellow circle a sodium chloride crystal has broken the organic-based layer.

Figure 22.

FTIR spectrum of the greyish surface layer showing the presence of siloxane.

Figure 22.

FTIR spectrum of the greyish surface layer showing the presence of siloxane.

4. Discussion

According to the results obtained the marble steps and the pyramid basement are supported by a brick structure which is completely embedded by lagoon water. The rising damp migrating from the foundations is transporting sodium and chloride ions through bricks and marble porosity. When solutions reach the oversaturation conditions salt crystallization takes place. As these conditions depend on the driving force of capillary suction and on the water vapor evaporation rate, crystallization can take place outside the surface (efflorescence) (Figure 21) or at sub-surface level (crypto-efflorescence) (

Figure 16, Figure 17, Figure 18 and Figure 19).

The same mechanism is active all over the monument and the deterioration features observed represent the different stage of deterioration recorded during the survey.

The first stage of deterioration is characterized by rough and whitish surface due to the accumulation of sodium chloride nearby the external surface (less dense substrate). In these areas the whitish colour is ascribed to a change of refractive index. These areas are quite widely present on the marble steps and in some parts of the sculptures (

Figure 10 and

Figure 14).

A second stage of deterioration is characterized by partially detached marble flakes (multilayer exfoliation) from the substrate. Crystallization initially occurs near the external surface and continues towards the internal layers, separating marble flakes mostly in parallel layers (

Figure 11,

Figure 16 and Figure 17).

A third stage of deterioration is characterized by the complete missing of marble portions as it is visible on the

Sleeping Genius (

Figure 2a) and

Painting and Architecture statues (

Figure 2b). These more damaged areas are corresponding to the maximum capillary rise front (between 150 and 250 cm) which present the highest salt crystallization pressure.

A specific alteration feature is represented by the

formation of reddish circular spots which are localized in some areas and the surface is rough and opaque similar to the whitish areas before described (

Figure 10). These alterations are ascribed to linchpin oxidation to colloidal iron oxides which slowly diffuse through the porosity of marble.

Summarizing the main cause of deterioration is due to the large amount of moisture coming from the brick structure, which is transporting the soluble salts of the lagoon. The marble steps and pyramid, being closely in contact with brick structure, are continuously embedded by soluble salts solutions. The water evaporation from the surface of the marble steps causes the enrichment in salt concentration near the surface and when ion saturation conditions are reached crystallization takes place. When the latter occurs near the surface, mechanical tensions breaking the capillaries occurs.

As we have already seen, sub-surface crystallization at the third stage normally occurs near the maximum height of water capillary rise front, which can vary between 150 and 250 cm from the church floor. The steps of the cenotaph are between 100 and 200 cm and they are affected by the initial stage of deterioration and to a minimal extent by the second stage of deterioration. In the case of the statues of Painting, Architecture and the Sleeping Genius, the third stage of deterioration is observed at a height of approximately 200 cm. Other areas of deterioration at the third stage can be observed in correspondence with the draperies of the statues and the garland and other convex surfaces that are characterized by more frequent evaporation cycles than flat or slightly curved surfaces. The greater frequency of evaporation cycles leads to a greater number of crystallization cycles and therefore to an acceleration of the decay processes with greater losses of material.

Last observation is related to the observed turning of white-grey marble toward greyish ascribed to a chromatic alteration of the wax-based treatments. Wax application most likely dates back to the final phase of the construction of the cenotaph and may have been periodically repeated as a maintenance practice in use in subsequent periods.

In the 1993 intervention, acrylic or acryl-siloxane resins were applied, which were identified by our survey and by the previous 2009 survey. This intervention together with the initial wax treatment exacerbated the phenomena of sub-surface crystallization, accelerating the decay processes.

5. Conclusions

At the end of our survey, it was evident that the presence of such an important source of moisture, quantitatively superior to most of historic Venetian buildings, was responsible for the visible phenomena of deterioration observed. Therefore, before to start any conservation intervention it is recommended to stop the rising damp process by isolating the brick structure from the marble steps and statues. Furthermore, since the marble elements were completely salt embedded it is necessary to remove all statues and marble elements at least up to three meters of elevation from the church floor. For the marble elements above three meters it is sufficient to proceed with the removal of the surface wax.

The removed marble statues and steps should be desalinated by immersion in deionized water tanks. A similar procedure had been adopted for the marble slabs of the church of Santa Maria dei Miracoli and for the statues of San Giobbe church in Venice.

The brick structure should be dehumidified and desalinated by using poultices according to EN 17891 [22]. Successively, the brick structure should be insulated to stop the transmission of moisture from the foundations to the marble elements.

The proposed intervention is radical and certainly entailed very significant technological and structural difficulties, however almost similar interventions had already been undertaken on other Venetian monuments.

Funding

This research received funds from Venice in Peril Fund.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy reasons.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the Superintendence for the Architectural and Landscape Heritage of Venice.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Soprintendenza per i Beni Architettonici e il Paesaggio di Venezia e Laguna, Chiesa Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari, Progetti generali di restauri 1858-1862, prot. 283, 1856, Venezia.

- Amoroso, GG.; Fassina, V. Stone Decay and Conservation, Elsevier, Amsterdam, 1983, pp. 453.

- Arnold, A.; Zehnder, K. Salt weathering on monuments, in Proceedings of the 1st International Symposium, The Conservation of Monuments in the Mediterranean Basin, Bari, 1989, pp. 31-58.

- Dohene, E. Salt weathering: A selective review. In Natural Stone, Weathering Phenomena, Conservation Strategies and Case Studies; Geological Society Special Publication n. 205; Siegesmung, S., Weiss, T., Vollbrecht, A., Eds.; Geological Society Publications: London, UK, 2002; pp. 51–64. [Google Scholar]

- Scherer, G.W. Stress from crystallization of salt. Cem. Concr. Res. 2004, 34, 1613–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez Navarro, C.; Dohene, E. Salt weathering: Influence of evaporation rate, supersaturation and crystallization pattern. Earth Surface Process. Landf. 1999, 24, 191–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewin, S.Z. The mechanism of masonry decay through crystallization, in: S.M. Barkin (Ed.), Preprints Conservation Historical Stone Buildings Monuments, National Academic Press, Washington DC, USA, 1982, pp. 120–144.

- Camuffo, D.; Del Monte, M.; Sabbioni, C. Influenza delle precipitazioni e della condensazione sul degrado superficlae dei monumenti in marmo e calcare. Bollettino d’Arte, Supplemento al n. 41, Materiali laidei, Roma, 1987, pp.15-36.

- Camuffo, D. Microclimate for cultural heritage, Elsevier, Amsterdam, p. 416.

- Camuffo, D.; Bertolin, C. Relazione sul microclima del monumento a Antonio Canova, Basilica di Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari, Venezia, Rapporto alla SBAP di Venezia e Laguna, Research Grant n. 09-04 FR 3240216228, CNR Padova, 2010.

- Rizzi, F.; Giorio, R. Basilica Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari, Cenotafio di Antonio Canova, Misure dell’umidità e analisi dei sali solubili, Rapporto alla SBAP di Venezia e Laguna, Venezia 2009.

- Fassina, V.; Favaro, M.; Naccari, A. Principal decay patterns on Venetian monuments, in Natural Stone, Weathering phenomena, Conservation Strategies and case Studies, eds. S. Siegesmund, A. Volbrecht and T. Weiss, The Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 205, 002, pp. 381-391. [CrossRef]

- Fassina, V.; Schilling, M.R.; Keeney, J.; Khanijan, H. Weathering of marble in relation to atmospheric pollution and man-made intervention on the church façade of S. Maria del Giglio in Venice. Air pollution and Cultural Heritage, Ed. C. Saiz Jimenez, 15 August 2004, CRC Press, London, pp. 117-126. [CrossRef]

- Fassina, V. A survey on air pollution and deterioration of stonework in Venice, Atmospheric Environment, 12, 1978, pp. 2205-2211. [CrossRef]

- Fassina, V. New findings on past treatments carried out on stone and marble monuments’ surfaces. Science of the Total Environment, Volume 167, issues 1–3, 1995, 185–203. [CrossRef]

-

EN 16085; Conservation of Cultural Property—Methodology for Sampling from Materials of CULTURAL Property—General Rules. CEN (European Committee for Standardization): Bruxelles, Belgium, 2012.

-

EN 16455; Conservation of Cultural Heritage—Extraction and Determination of Soluble Salts in Natural Stone and Related Materials Used in and from Cultural Heritage. CEN (European Committee for Standardization): Bruxelles, Belgium, 2014.

- Legrand, L.; Mazerolles, L.; Chausse, A. The oxidation of carbonate green rust into ferric phases: solid-state reaction or transformation via solution, Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, Vol. 68, No. 17, 2004, pp. 3497–3507.

- Génin, J.M.R.; Refait, Ph.; Simon, L.; Drissi, S.H. Preparation and Eh–pH diagrams of Fe(II)–Fe(III) green rust compounds; hyperfine interaction characteristics and stoichiometry of hydroxy-chloride, -sulphate and –carbonate, Hyperfine Interactions, 111 1998, 313–318.

- Ruby C. et al., Oxidation modes and thermodynamics of FeII-III oxyhydroxycarbonate green rust: dissolution-precipitation versus in-situ deprotonation; about the fougerite mineral, Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta, June 2009.

- Van Hook, A. Supersaturation and Liesegang Ring Formation. I, in The Journal of Physical Chemistry, vol. 42, n. 9, 1937, pp. 1191–1200. [CrossRef]

-

EN 17891; Conservation of Cultural Heritage—Desalination of Porous Inorganic Materials by Poultices. CEN (European Committee for Standardization): Bruxelles, Belgium, 2023.

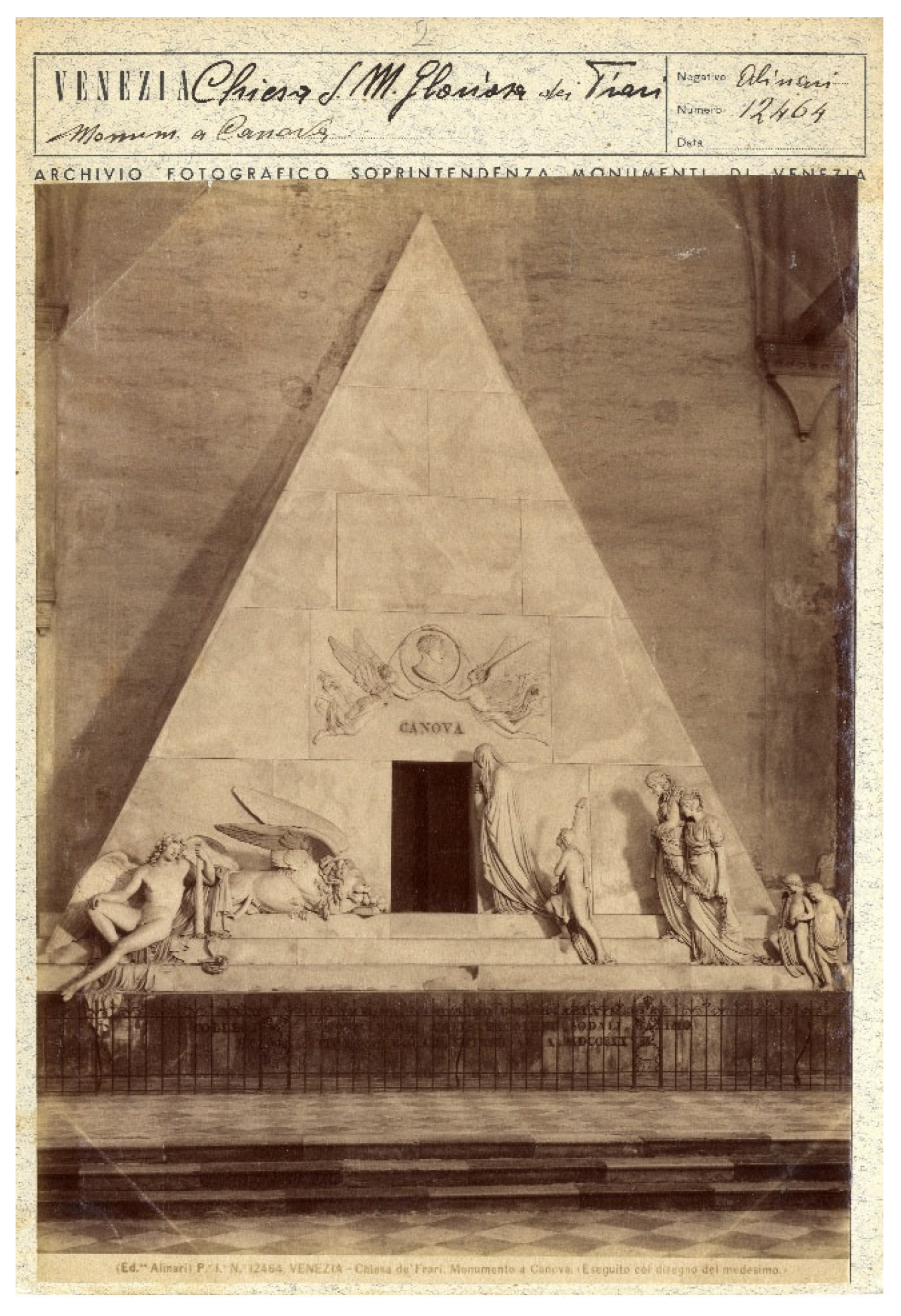

Figure 1.

The cenotaph to Antonio Canova. From the left the Sleeping Genius and the lion; the Sculpture bringing Canova heart inside a cinerary urn; the Genius with the mortuary torch; Painting and Architecture; Tutelary Genes with lit mortuary torches (Courtesy of Superintendence for Architectural and Landscape Heritage of Venice-Alinari photograph).

Figure 1.

The cenotaph to Antonio Canova. From the left the Sleeping Genius and the lion; the Sculpture bringing Canova heart inside a cinerary urn; the Genius with the mortuary torch; Painting and Architecture; Tutelary Genes with lit mortuary torches (Courtesy of Superintendence for Architectural and Landscape Heritage of Venice-Alinari photograph).

Figure 2.

a) Detail of marble exfoliation on the chest of the Sleeping Genius showing the underlying whitish salt crystal. b) Detail of the marble exfoliation of the garments of Painting and Architecture.

Figure 2.

a) Detail of marble exfoliation on the chest of the Sleeping Genius showing the underlying whitish salt crystal. b) Detail of the marble exfoliation of the garments of Painting and Architecture.

Figure 3.

Droplet formation on the arm of the statue due to water vapour condensation.

Figure 3.

Droplet formation on the arm of the statue due to water vapour condensation.

Figure 4.

Thermographic image of the cenotaph. Basement is warmer than statues.

Figure 4.

Thermographic image of the cenotaph. Basement is warmer than statues.

Figure 5.

a) The Sleeping Genius. b) The hairs of the Sleeping Genius appear yellow at IR observation: this indicates some not visible detachments of marble surface (Courtesy of Camuffo).

Figure 5.

a) The Sleeping Genius. b) The hairs of the Sleeping Genius appear yellow at IR observation: this indicates some not visible detachments of marble surface (Courtesy of Camuffo).

Figure 6.

Santa Maria dei Miracoli Church. On the lower part salt efflorescence are visible; on the upper part sub-efflorescence are detaching small flakes of marble.

Figure 6.

Santa Maria dei Miracoli Church. On the lower part salt efflorescence are visible; on the upper part sub-efflorescence are detaching small flakes of marble.

Figure 7.

The supporting structure is formed by a rather regular brick structure. Carrara marble steps having a triangular section are in close contact with the underlying brick. The moisture in the brick structure has a water content near the saturation of brick porosity and it is easily transmitted to the Carrara marble steps.

Figure 7.

The supporting structure is formed by a rather regular brick structure. Carrara marble steps having a triangular section are in close contact with the underlying brick. The moisture in the brick structure has a water content near the saturation of brick porosity and it is easily transmitted to the Carrara marble steps.

Figure 8.

Percentage of water content at different heights. Up to 90 cm the water content is close to the brick saturation. Increasing elevation from the church floor, the moisture content is decreasing. This behaviour is present when the rising damp is active.

Figure 8.

Percentage of water content at different heights. Up to 90 cm the water content is close to the brick saturation. Increasing elevation from the church floor, the moisture content is decreasing. This behaviour is present when the rising damp is active.

Figure 9.

Percentage of chlorides versus elevation in the brick structure. Higher chloride content is from 185 and 235 cm.

Figure 9.

Percentage of chlorides versus elevation in the brick structure. Higher chloride content is from 185 and 235 cm.

Figure 10.

Whitish surface areas, slightly eroded. The explanation of this feature is discussed by optical and SEM microscope analyses. The pale yellowing areas are ascribed to iron oxides formation due to oxidation of small particle of pyrite (FeS2). The yellowing is a natural weathering alteration due to the presence of this small iron impurities in the Carrara marble.

Figure 10.

Whitish surface areas, slightly eroded. The explanation of this feature is discussed by optical and SEM microscope analyses. The pale yellowing areas are ascribed to iron oxides formation due to oxidation of small particle of pyrite (FeS2). The yellowing is a natural weathering alteration due to the presence of this small iron impurities in the Carrara marble.

Figure 11.

Exfoliation of thin marble layers due to salt crystallization at sub-surface level.

Figure 11.

Exfoliation of thin marble layers due to salt crystallization at sub-surface level.

Figure 12.

Red spots formation due to colloidal iron oxide radial diffusion.

Figure 12.

Red spots formation due to colloidal iron oxide radial diffusion.

Figure 13.

Marble of the lower left leg of the statue has darkened. This chromatic alteration is ascribed to a colour change of past wax maintenance treatment (see Figure 20).

Figure 13.

Marble of the lower left leg of the statue has darkened. This chromatic alteration is ascribed to a colour change of past wax maintenance treatment (see Figure 20).

Figure 14.

a) Cross-section at the optical microscope (80 x enlargements). Interstitial detachment of calcite crystals is visible; b) The same sample at SEM shows a clearly separation of calcite crystals. The lower density of surface layer is responsible of the whitish aspect visually observed. In this area the whitish surface is representing the initial stage of marble deterioration.

Figure 14.

a) Cross-section at the optical microscope (80 x enlargements). Interstitial detachment of calcite crystals is visible; b) The same sample at SEM shows a clearly separation of calcite crystals. The lower density of surface layer is responsible of the whitish aspect visually observed. In this area the whitish surface is representing the initial stage of marble deterioration.

Figure 15.

a) Cross-section at optical microscope shows interstitial calcite crystals detachment (layer a) as before observed. The thin grey layer B is the wax treatment. Enlargement 80x. b) At SEM the interstitial spaces are increased with respect to

Figure 14. This is a more advanced stage of deterioration. The black layer B on the upper part is a remaining of wax maintenance treatment.

Figure 15.

a) Cross-section at optical microscope shows interstitial calcite crystals detachment (layer a) as before observed. The thin grey layer B is the wax treatment. Enlargement 80x. b) At SEM the interstitial spaces are increased with respect to

Figure 14. This is a more advanced stage of deterioration. The black layer B on the upper part is a remaining of wax maintenance treatment.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).