1. Introduction

Using boat for recreational purposes is becoming more and more popular around the world and is especially important in Europe. Twenty-three of the 27 EU Member States have a coastal border with 68,000 km of coastline [

1]. Over 6 million boats are kept in European waters, while some 36 million Europeans participate regularly in boating activities [

2], generating important economic activity in which tourism plays an important role. Nautical tourism is popular across the EU [

3], and the Mediterranean Sea is recognized as one of the world's most important nautical tourism hubs [

4].

However, the definition of nautical tourism is not yet firmly established [

5,

6,

7], and, consequently, in addition to issues related to the inconsistent use of different terms [

8], there is a lack of clear criteria to distinguish between tourism and non-tourism activities within recreational boating. It results in incomplete coverage and incomparability of data related to recreational boating since it has been defined differently in individual countries' institutional and statistical frameworks [

9]. That can be illustrated by a noticeable discrepancy between studies that define nautical tourism based on overnight stays on board, exclusively [

10,

11], and those that also include same-day activities at sea [

12,

13]. This inconsistency resulted in efforts to harmonize definitions in line with tourism statistics.

The evolution in the conceptualization of same-day yachting within the broader framework of nautical tourism is demonstrated by different approaches to defining nautical tourism in two papers by Benevolo [

10] and Spinelli & Benevolo [

6]. In the 2011 work, Benevolo [

10] distinguishes sharply between recreational boating and nautical tourism. She defines nautical tourism as a specific subset of marine tourism that includes travel and overnight stay on a pleasure craft. According to this view, recreational boating, which may involve day-trips or localized leisure activities without overnight accommodation, is not considered tourism. In the 2022 paper co-authored with Spinelli [

6], Benevolo acknowledges that although same-day yachting does not fulfill the requirement of an overnight stay, it shares many core features with nautical tourism in which the primary motivation for going on a trip is to enjoy sailing and related experiences on water and land for recreation, sports, entertainment, or other needs [

14,

15].

However, in addition to taking into consideration of the motives and activities involved in nautical tourism, as well as the aspect of length of a trip, a more precise definition of nautical tourism also requires the introduction of the concept of the usual environment as a key demand-side determinant of tourism activity. The unique spatial and geographical characteristics of the marine environment make the concept of the usual environment particularly complex in the context of nautical tourism [

11], especially evident in the domestic same-day visitor segment. At the same time, assessing the economic effects of domestic visitors in this type of tourism should 'scrupulously avoid including any effects of expenditures or other consumption activities of local residents remaining in their usual environment' [

16] (p. 140).

The purpose of the research is therefore to assess the need for a more thorough and precise approach to the implementation of the usual environment criterion for measuring the size of nautical tourism demand. Using the example of Croatia as a country where nautical tourism accounts for a significant part of total tourism activity [

17], the paper looks at the criteria for assessing domestic nautical tourism demand based on both secondary data analysis and primary research.

Following the introduction, the paper starts with a literature review related to the concept of the usual environment, with an insight into the specifics of the assessment of the usual environment in nautical tourism. The third chapter presents the volume and characteristics of nautical tourism in Croatia, and identifies issues in measuring the size of nautical tourism due to the vague and blurry understanding of the concept of the usual environment. The fourth chapter presents the methods of the primary research conducted on the population of residents who are recreational boat owners. The results of the research are presented in the fifth chapter. The sixth chapter provides a discussion, conclusions, and recommendations for a more accurate and precise assessment of the size of nautical tourism.

2. The Literature Review

The concept of the usual environment is considered a crucial determinant of the demand side of tourism flows, particularly in the context of same-day visitors. The concept has evolved from a simple definition based on physical distance to a more complex one that incorporates personal, cultural, and experiential dimensions. Use of the criteria of 'the crossing of administrative borders or the distance from the place of usual residence, the duration of the visit, the frequency of the visit, the purpose of the visit' [

18] (p. 19/192) involves numerous challenges in the assessment of the physical and monetary size of tourism, which is augmented in the process of international harmonization.

The International Recommendation for Tourism Statistics from 2008 [IRTS 2008] states that 'The usual environment of an individual….. is the geographical area (though not necessarily a contiguous one) within which an individual conducts his/her regular life routines.' [

19] (p. 12). IRTS 2008 also stresses that each country should precisely define the regularity and frequency of tourism trips in the context of its tourism statistics. Due to the differences among countries, Eurostat [

20] concluded that it is nearly impossible to draw up a strict framework, so it is desirable to consider the respondents' subjective feelings when determining the usual environment. However, to collect tourism statistics from a demand side perspective, Eurostat recommends applying an operational criterion, the so-called cascade system. Same-day visitors and tourists are delimited through evaluation of the following criteria which should all be fulfilled at the same time for determining the tourism activity:

Purpose of the visit: the trip is not part of the regular life routines of the traveler;

Crossing of administrative borders: visits outside the municipality just as a general rule;

Duration of the visit: at least 3 hours for same-day visitors or one overnight for tourists;

Frequency of the visit: less than one trip per week over a longer period.

The criterion 'distance from the place of usual residence' is included implicitly through the criteria of the crossing of administrative borders and the duration of the visit. Allowing the possibility that tourist activity can also be carried out in the usual environment and to link demand and supply side information on domestic tourism, Eurostat [

20] recommends that all overnights in tourist accommodation establishments be treated as tourist overnights, i.e. overnights outside the usual environment. Similarly, trips to vacation homes are usually considered tourism trips.

Since comparable and coherent statistical information on tourism is a prerequisite for quantifying the size and impact of tourism, individual countries should follow internationally recognized standards [

21,

22]. However, the common interpretation of the usual environment has not been established across the EU [

23,

24]. In order to apply the recommended cascade system, National statistical offices in EU countries have established different 'hard/objective' systems in determining the usual environment. Some countries use the distance threshold as an alternative criterion for administrative borders, while others do not apply the criteria of frequency of visits and minimum length of trip in order to minimize the influence of 'subjectivity, confusion and unsystematic variation' [

25] (p. 19) in data collection.

The different approach to assessment of usual environment not only questions the comparisons of tourism activity among countries but also the adequacy of measuring the size of tourism consumption and its implications on the production of tourism activities and the generation of tourism added value at the level of individual countries. Moreover, it also questions the accuracy of tourism sustainability indicators calculation. The need for harmonized operationalization [

26] and embedded subjectivity prompted numerous scholars to contribute to a better understanding of the concept of the usual environment.

Govers et al. [

27] delve into the complexities of defining the 'usual environment' within tourism research, suggesting a flexible approach to accommodate the diverse experiences of tourists. They challenge the application of rule-of-thumb distance measures for delineating the 'usual environment', highlighting the complexity of determining what constitutes an individual's usual environment, especially in highly urbanized areas. Although the authors confirm the ‘usual environment’ as a distance related concept, they emphasize its subjective nature and suggest a more context-specific approach to its definition, arguing for integrating both exogenous (objective) and endogenous (subjective) assessments. The findings underscore the importance of understanding the 'usual environment' in tourism statistics and the challenges in operationalizing this concept for accurate and meaningful analysis. Yu et al. [

28] emphasize the role of personal perception in defining one's tourist status. Their research identifies a clear distance threshold (about 75 miles) that influences self-categorization as tourists, supporting the technical approach to defining tourism. The findings reveal that first-time visitors, those traveling for pleasure, women, and individuals from the lower middle class are more likely to consider themselves tourists.

Diaz-Soria [

29] further challenges the traditional boundaries between the 'usual' and 'tourist' environments, bridging the gap between the identities of tourists and residents. The paper suggests that adopting a tourist gaze in familiar locales enables a re-discovery and appreciation of one's immediate surroundings. Suriñach et al. [

30] contribute to this discourse by proposing a methodological approach to accurately capture day trips in urban environments.

Post-tourism introduces an additional aspect to the understanding of tourist activity. It focuses on the search for authentic tourism experiences [

31], which are marked by personal participation and spiritual interaction with the environment [

32]. Such experience can be achieved in the usual environment as well, if it provides a departure from daily life [

33].

The concept of the usual environment is particularly complex in the context of nautical tourism [

11]. Unlike mainland tourism, where geographical boundaries are more precise, the boundaries in nautical tourism are more fluid, making it difficult to define what constitutes a usual environment from an individual/subjective perspective. This issue is almost completely neglected in the literature. For example, Diakomihalis [

34] incorporates the aspect of distance into his discussion of the characteristics of nautical tourism. However, he does not contextualize it within the usual environment concept. Comprehensive bibliometric analyses [

9,

35] of the evolution of nautical tourism research do not directly address the concept of the 'usual environment', nor explicitly define 'nautical tourism'. Furthermore, the recent literature review on yachting [

36] points to the growing interest in topics related to nautical tourism, such as innovation, consumer experience, sustainability, and yacht-related events. However, the analysis did not single out the issue of the availability and quality of data in nautical tourism. Moreover, the analysis does not address the issue of understanding the term usual environment as the basis for distinguishing recreational from tourism activities in nautical environment.

In summary, while the concept of the usual environment is central to distinguishing tourism from recreational activities, it remains underexplored in the context of nautical tourism. Despite its relevance, the usual environment is rarely addressed in empirical studies of nautical tourism, and it is largely absent from recent thematic reviews. This gap is particularly striking given the growing attention to topics such as innovation, consumer experience, and sustainability. The literature overlooks questions about the availability and quality of data and the criteria for classifying activities as tourism - such as fluidity of spatial boundaries at sea - that poses significant conceptual and methodological challenges. The following section focuses on nautical tourism in Croatia, where statistical indicators suggest that same-day recreational boating is significantly underestimated. To better understand this issue, it is essential to address the assessment of the usual environment within the nautical tourism context.

3. Nautical Tourism in Croatia

The sea is a part of Europe's identity, and sailing is an important motive for travel to Mediterranean countries. Italy is the most important country in the recreational boating sector in the Mediterranean and the second most important worldwide. It has more than 500 marinas and harbors with around 160,000 berths and 85,000 registered pleasure crafts [

37]. Spain has around 300 marinas with 130,000 berths, 78% located in the Mediterranean region [

38]. France has around 106,000 berths in marinas in the Mediterranean Sea, almost half the country’s total berth capacity [

39].

Croatia has 224 nautical tourism ports with around 19,000 berths, of which 85 are marinas [

40]. Additionally, there are more than 46,000 berths available exclusively for the local population, so-called communal berths and 22,000 berths allocated for nautical tourists in numerous public ports along the Adriatic coast. There were more than 122,000 boats registered in 2018 in Croatia, of which 106,000 were registered for personal use [

41,

42,

43].

The official tourism statistics from the demand side shows that inhabitants of coastal regions of Croatia almost do not undertake same-day trips on recreational boats [

44]. Data are collected by the survey regularly carried out by the Croatian Bureau of Statistics since 2014 under Regulation (EU) No 692/2011 [

18]. The 2022 survey was conducted on a representative sample of 22,000 Croatian citizens aged 15 and over, covering, among others, the characteristics of same-day trips.

A total of 4.0 million domestic, private, and business same-day trips were undertaken in 2022 by 3.9 million Croatian residents [

45]. Of these, 1.3 million inhabitants of Adriatic Croatia accounted for 1.25 million private and business same-day trips (

Table 1). However, only 22.5 thousand of 1.25 million same-day trips—representing just 1.8 percent—were carried out by boat as the main mode of transport. Notably, no same-day boat trips were recorded for residents of Primorje-Gorski Kotar, Lika-Senj, or Šibenik-Knin counties. Same-day trips by boat were registered in only three of the seven Adriatic counties: Split-Dalmatia, Zadar, and Istria. Within this group, Split-Dalmatia County alone accounted for two-thirds of all same-day boat trips in the Adriatic Croatia, with nearly all (98 percent) of those trips taking place within the county itself.

These figures suggest that the role of recreational boating, particularly for same-day trips, may be significantly underestimated in official tourism statistics. The reason is twofold: (i) the sample size of the survey and low rate of incidence of same-day trips by boat, and (ii) perception of the usual environment when taking same-day trips by boat, especially by recreational boat. However, same-day trips by boat refer not only to nautical (yachting) tourism, but also to trips by sea and coastal passenger water transport as the main means of transport (i.e. catamarans or ferries used by passengers only). This partly explains why Split-Dalmatia County generates a lot of same-day trips by boat in Adriatic Croatia as it is characterized by many populated islands that are well connected by public sea passenger transport.

Further, the lack of a record of same-day boat trips in four out of seven coastal counties, including the County of Primorje-gorje, which has the highest number of registered boats, implies that there is a methodological issue in detecting and measuring this segment of tourist activity, partly due to the perception of the usual environment by residents using recreational boats. Since the survey Tourist Activity of the Population of the Republic of Croatia is one of the key sources for assessing the size of domestic tourism [

46], this affects the assessment of not only the size of nautical tourism but also the overall tourist expenditure and the contribution of tourism to the economy. Therefore, qualitative exploratory research has been conducted to improve understanding of the perception of the usual environment among recreational boat owners.

4. Methods

This paper takes the position that the nautical tourism should be within the scope of tourism statistics, particularly in countries where it is one of the relevant tourism products, despite Eurostat’s [

20] recommendation to exclude marinas from the scope of tourism statistics. It is, therefore, necessary to address the challenges related to the extreme complexity of data collection and the measurement of tourist activity generated by recreational boating.

A fundamental step in establishing a methodological framework for measuring the size of nautical tourism is the application of the usual environment concept to distinguish tourism from recreational boating. As the literature review has shown, this process raises several important issues: (i) the relevance of administrative boundaries at sea, (ii) the perceived distance in relation to the type and speed of the vessel, (iii) the frequency of sailing as a regular seasonal activity, and (iv) the treatment of the vessel as a form of accommodation and its potential equivalence to a second home.

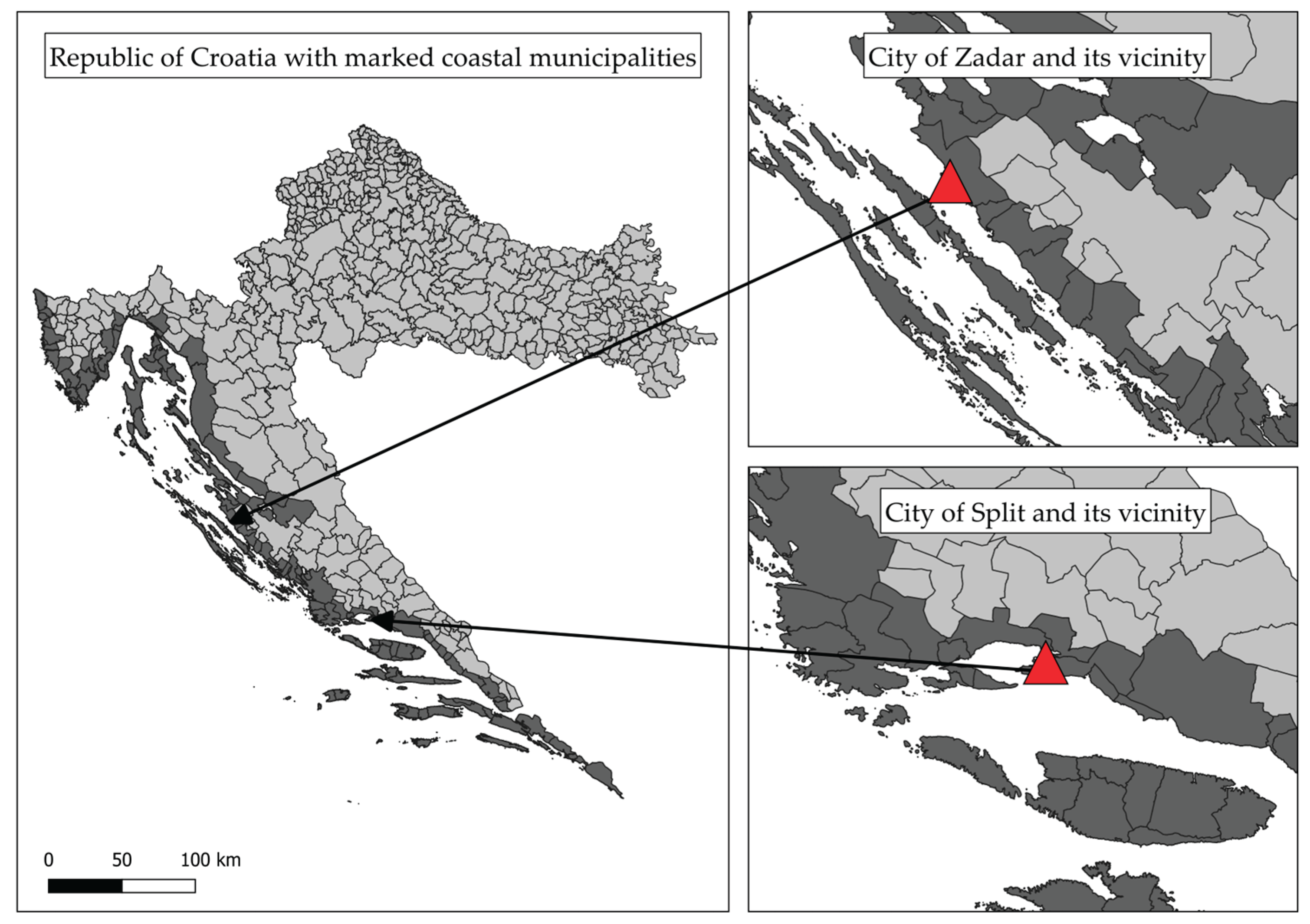

A primary research was conducted to assess the perception of the concept of the usual environment among boat owners with respect to taking a same-day boat trip. Additionally, the goal was to analyze the factors that impact this perception. The target population were residents of coastal cities and municipalities. As the research was focused on same-day trips, the issue of using a boat as accommodation was not tackled.

The research employed a qualitative approach, utilizing in-depth interviews to gather detailed insights from boat owners in two Croatian coastal cities – the City of Split and the City of Zadar (

Figure 1). The cities of Split and Zadar were selected for this research based on specific criteria that identified them as relevant sites for examining daily boating practices:

The study sample was selected using a combination of convenience sampling and the snowball sampling approach. Initially, boat owners were identified and contacted through local boating clubs, marinas, and personal networks in Split and Zadar, taking advantage of readily accessible contacts to quickly gather a preliminary group of respondents. Subsequently, the snowball sampling technique was employed, where initial respondents were asked to provide references to other boat owners interested in participating in the research.

A semi-structured guide was used as a research instrument to ensure that key topics were consistently covered while allowing for flexibility to explore individual experiences and perspectives. The semi-structured guide included three main topics:

Basic sociodemographic, type of boat, and location of berth;

Boat usage patterns, destinations, and routes: frequency and season of use, travel party, trip duration, travel distance, motives and activities, destination and route preferences;

Perception of boating as a lifestyle versus tourism trips, i.e. attitudes towards the usual environment, since besides the operational criteria for collecting tourism statistics it is also important to consider the subjective feelings of the respondent when determining the usual environment [

20].

The interviews were conducted by the authors, through an online meeting platform or mobile phones. The interviews were announced in advance and the oral informed consent was obtained at the beginning of the interview. Prior to obtaining the consent, the participants were informed on the purpose of the research, data collection process and analysis, as well as on the anonymity and confidentiality of their participation. The interviews lasted 30 to 45 minutes. Some of the interviews were, following the participant’s consent, recorded and transcribed, while for the others the notes were taken during the interview. Content analysis was applied to analyze the interview data according to the specified topics.

A total of 17 boat owners participated in the study (10 respondents from Split and seven from Zadar). The decision to stop at 17 responses was driven by data saturation, as the information had become repetitive, and consistent patterns across participants were observed. Thus, 17 responses were sufficient to achieve a comprehensive understanding of the research topic. Owners of both sailboats (9 respondents) and motorboats (8 respondents) were included. Regarding the age groups, three were between 30 and 39 years of age, six from 40 to 49, five from 50 to 59, and three were older than 60 years of age.

5. Results

The research results are presented according to the following topics relevant for interpreting subjective and objective criteria of usual environment assessment on same-day boat trips: (i) frequency and season of use, (ii) travel party and trip duration, (iii) travel distance and destination preferences, (iv) motives and activities, and (v) perception of boating as a lifestyle and tourism trip.

5.1. Frequency and Season of Use

Respondents primarily use their boats during the summer months, engaging in frequent same-day and weekend trips from May to October, along with some extended trips during vacation periods. In winter, the most common activity is fishing with friends and participating in regattas.

The frequency and season of use largely depend on the type of vessels and motives for sailing. Those in sailing boats, in contrast to those in motorboats, use their vessels throughout the year, with the most passionate “accumulating up to 60 days at sea”, as mentioned by respondent no. 2 engaged also in regattas (Split, sailing boat). However, one motor-boat owner (respondent no. 7 from Split) also spend between 50 and 60 days per year at sea. As he noted: “Whenever I have a free time, I go to the sea for sport fishing”.

5.2. Travel Party and Trip Duration

Many respondents mentioned traveling with family and friends, who make up most common travel party on a boat trip, especially in the summer.

Although the questions directed respondents to discuss one-day trips, they often pointed out that multi-day trips are the most common type of voyage. Consequently, weekend trips (two to three days) are prevalent, with some preferring one-day outings, particularly for swimming/bathing or fishing. Longer trips are less common but occur occasionally.

Owners of sailing boats tend to use their boats for multi-day trips mostly due to the speed of sailing boats. Respondent no. 2 (Split, sailing boat) emphasized that for owners of sailing boats “it makes no sense to go out just for one day.” As he further elaborated, it takes several hours to reach more attractive destinations, as “the nicer places are further away.” However, some sailboat owners also enjoy same-day trips for quick sailing practice or a leisure trip. Respondents no. 4, 5, and 9 (all from Split) stated that they do go on same-day outings, most often during the summer, primarily for swimming or fishing. On the other hand, owners of motorboats prefer shorter, more frequent trips, often for fishing and day voyages. For instance, respondent no. 17 (Zadar, motorboat) explained, “during the season, I mostly take same-day trips due to work obligations.” However, technical complexity and operational demands can limit the frequency or spontaneity of same-day boating, even within the motorboat segment. Respondent no. 8 (Split, motorboat) explained that his boat requires significant preparation and handling, stating that “a boat is not for just going out for one day - a vessel needs preparation before setting out; it’s not suitable for simple day trips.”

Younger boat owners are more likely to engage in shorter, more frequent trips, often due to time constraints related to work and family as mentioned by respondents no. 9 (Split, sailing boat) and no. 14 (Zadar, motor boat). In contrast, older owners, especially retirees, often use their boats more extensively, taking longer trips and more frequent outings.

5.3. Travel Distance and Destination Preferences

Trips typically stay within a short to moderate range due to the nature of day trips or short weekend getaways. Long-distance voyages are usually reserved for more extended vacations.

Common destinations for same-day trips or short weekend getaways include destinations on nearby islands, for boat owners in both Split and Zadar. In all cases, journeys entailed crossing administrative boundaries.

Some boaters emphasized the need to travel beyond the immediate coastal area to find less crowded locations. Respondent no. 13 (Zadar, motorboat) noted that “you need to go 20 to 30 minutes away from Zadar, even there it’s crowded with boats.” Their typical outings are Saturday and/or Sunday day trips from 9 a.m. to 6 p.m., often framed as family excursions or informal gatherings. These trips involve anchoring offshore and spending the day on the boat, illustrating a common same-day boating pattern that combines socializing and leisure in natural settings. Respondent no. 17 (Zadar, motorboat) reported similar distances for same-day outings, typically heading to a spot “around 2.5 nautical miles from Zadar”, further confirming that same-day boaters often stay within a relatively short range but still seek some degree of seclusion. However, the perception of the respondents is that increased volume and vessel size are reducing the availability of quiet, natural anchorages and altering the traditional boating experience. Respondents no. 2 and 3 (sailing boat owners, both from Split) noted that “today there are too many boats; nautical tourism is oversized.”

Although environmental concerns were not explicitly addressed in the interview guide, several respondents spontaneously expressed awareness of ecological pressures, particularly related to the growth of charter fleets, overcrowding of coastal areas and marine pollution.

5.4. Motives and Activities

The primary motives for using boats are recreation, sport and socializing to ‘relax and unwind’.

Activities include swimming, fishing, participating in sailing regattas and events, and general leisure. Getting off the boat at destinations is rare, and when it does happen, it's usually related to visits to shops, bars, and restaurants.

A number of respondents emphasized a preference for free anchorages over marinas or organized ports, often to avoid fees and crowded environments. For example, respondent no. 5 (Split, sailing boat) stated that they “don’t go off the boat, avoid entering ports (where fees apply), don’t moor - we choose quiet bays and anchor there.” This reflects a nature-oriented approach to boating, where the vessel itself becomes both the means and the destination of leisure.

The choice of anchorage versus mooring in a port often depends on the duration of the trip and associated costs. When going out for a swim or a short leisure trip, respondents typically anchor in small bays where no fees are charged. However, for longer holiday trips, boaters may enter towns or ports - depending on mooring costs. Respondent no. 9 (Zadar, sailing boat) noted that mooring fees have become quite substantial, influencing their behavior and explained: “If we don’t pay for mooring, we’ll go to a restaurant; but if we do pay, we eat on the boat instead” illustrating a substitution effect under the budget constraint.

5.5. Perception of Boating as a Lifestyle and Tourism Trip

A deep personal connection to the sea is evident among all respondents. Many owners view boating as an integral part of their lifestyle rather than a form of tourism. For them, it is a part of their daily life and routine, as well as a cultural practice. Boating is seen as a natural extension of living on the coast. Many respondents do not consider their boating activities as tourism but as an activity within their usual environment. Day trips and weekend outings are not seen as trips. As respondents no. 5 (Split, sailing boat) emphasized “Is going on the boat tourism? No, it is an integral part of our life.” However, taking trips to the same destination using the alternative main means of public sea transport (ferry, catamaran) is seen as a tourist trip.

Some respondents recognize elements of tourist activity in sailing, regardless of whether the trips are same-day or multi-day. Respondents no. 12, 14 and 17, all motor-boat owners from Zadar and respondent no. 8 (Split, motorboat) consider same-day boat trip as tourism activity. However, contrasting opinions are common within this group. “Being at sea is a different experience than just watching the sea” the respondent no. 1 (Split, motorboat) noted, and further elaborated that “a boat is not a part of the usual environment”. Staying on a vessel is described by the same respondent as “a break from the everyday life”, while for the respondent no 4 (Split, sailing boat) it is “pure zen, another world, a great memory wipe”. However, somewhat contradictory, he continued: “it is a normal way of life for me, I don't feel like a tourist”.

For young boat owners, boating is ‘more of a recreational activity than a lifestyle’, while older ones tend to have a stronger connection to the sea as part of their cultural identity and daily routine. Owners of sailing boats often view sailing as a sport, stressing the skill and effort required for sailing. Motorboat owners view motorboating as a convenient and quick way to enjoy the sea.

6. Discussion and Conclusion

The in-depth interviews provide an insight into the boating practices and perceptions among recreational boat owners in the two large Croatian coastal cities Split and Zadar. The distinction between boating as a lifestyle and as a tourism activity is pronounced, with many owners integrating boating into their usual environment. This is in line with Jennings [

47] who stresses the fuzziness of boundaries among sport, recreation, leisure, tourism activities and lifestyle. Differences between sailboat and motorboat owners and between different age groups highlight the diverse ways boating is experienced in these coastal cities. Same-day voyages are practiced by all boat owners, with motorboat owners particularly favoring these short voyages for their convenience and ease.

Boating is deeply integrated into the lifestyles of the interviewees, providing freedom, tranquility, and a unique way to experience and appreciate the marine environment. Most respondents utilize their boats predominantly for leisure activities, including fishing, sailing, and swimming. They see boating primarily as a form of relaxation, an escape from daily routines rather than a purely recreational activity, even when they are participating in regattas. The frequency of use varies, with most owners taking advantage of weekend trips while daily trips are less frequent.

Although boat owners generally do not consider same-day recreational boat trips as tourism activity, the identified characteristics of these trips indicate that they fulfil the three operational criteria of the cascade system for recognizing the tourism nature of travel [

20]:

Crossing of administrative borders: Although the term 'administrative borders' at sea is somewhat blurry, the findings confirm that respondents crossed administrative borders on most trips as they have usually visited the locations in another administrative units;

Duration of the visit: All trips lasted more than three hours;

Frequency of the visit: Less than one same-day boat trip is made per week over a longer period, especially in view of the seasonality of boating, an activity that is more pronounced during the summer months.

When it comes to the purpose of a visit criterion, the conclusion is not straightforward, as respondents’ opinions were divided. The findings highlight the importance of capturing the respondent's subjective feelings in determining the usual environment in nautical tourism. For some respondents, recreational boating is not part of regular life routines but an escape from daily routines, while other respondents often emphasize that recreational boating is deeply integrated into their lifestyles.

However, it can be concluded that the subjective perception of the usual environment comes from using one's own boat. From the perspective of many respondents, aside from authenticity, motivation, activity and place [

48], sailing on their own boat is a criterion for distinguishing between tourism and non-tourism activities. A journey made to the same destination, as by one’s own boat, by other means of transport for which a fare is charged is always considered an excursion or a tourist trip. Similarly, respondents distinguished accommodation in a hotel, assessed as tourism, and accommodation on their own boat, viewed as a stay in a second home. A minority of respondents put sailing on their own boats into the category of trips and acknowledge their tourism character, not differentiating between types of transport when defining a tourist trip.

The results thus indicate that trips with one's own vessel for leisure and recreation, whether same-day or multi-day, almost always represent an exit from the usual environment and are, therefore, a tourism activity, although respondents do not necessarily recognize this. This is especially relevant when considering the settings of post-tourist activity [

33].

Although boat owners do not recognize recreational boat trips as a tourism activity, application of the criteria defined by the cascade system [

20] implies that those trips can be considered as tourism activity. Therefore, the number of recreational boat trips, especially same-day trips, estimated from the survey on Tourist activity of the population of the Republic of Croatia [

44] is underestimated. Due to the same methodological framework of the survey on the trips of EU residents and participation in tourism [

20], it is reasonable to assume that this type of tourism activity is also underestimated in other EU countries, especially those with many recreational boats owned by residents. The underestimates of the overall demand for nautical tourism affect different pillars of the efficiency of the sustainable development management researched by numerous academics such as Carreno and Lloret [

49], Cerchiello [

50], Trstenjak et al. [

51] and Ukić Boljat et al. [

52]. It also underestimates domestic tourism expenditures and leads to an underestimation of tourism’s gross added value within the framework of the tourism satellite account. Therefore, understanding of the economic contribution of nautical tourism requires harmonized approach to the tourism statistics with emphasis on data coverage in collecting, organization and dissemination [

53] of nautical tourism data.

While these issues may not affect significantly all countries, they highlight the need to re-evaluate the factors and methods used to define the concept of the "usual environment" in the context of nautical tourism. This re-evaluation is a crucial step toward harmonizing the methodological approach for assessing the overall contribution of nautical tourism within the tourism satellite account framework. Assuming that the overall economic contribution of nautical tourism should not be overlooked, the proposed re-evaluation of the concept of usual environment, particularly within the European Union and by Eurostat, should prioritize two main areas.

First, it should involve a more refined elaboration of the usual environment concept when applying it specifically to nautical tourism. This primarily relates to the: (i) addressing the classification of a recreational boat as both a mode of transport and accommodation, (ii) relationship between administrative and geographical boundaries, and the (iii) relationship between the shore and the sea parts of the (usual or not usual) environment from the perspective of different segments of nautical tourism demand. Second, it should aim to improve the methodological framework of the survey on participation in tourism. This would involve: (i) distinguishing the use of vessels as passenger maritime transport from the use of privately owned recreational boats, and (ii) providing additional instructions when the respondent is not sure whether or not his/her nautical trip is outside the usual environment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.I. and Z.M.; methodology, Z.M.; software, Z.M.; validation, N.I. and Z.M.; formal analysis, N.I. and Z.M.; investigation, N.I. and Z.M.; resources, N.I. and Z.M.; data curation, Z.M.; writing—original draft preparation, N.I. and Z.M.; writing—review and editing, N.I. and Z.M.; visualization, N.I.; supervision, N.I.; project administration, Z.M.; funding acquisition, N.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work has been supported by the Croatian Ministry of Science, Education, and Youth under the NextGeneration EU program.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study did not require ethical approval in accordance with the Croatian Law and the Institute’s for Tourism Ethical Codex.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed verbal consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data (interviews’ transcripts in the Croatian language) supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The working version of the paper was presented at the 63rd ERSA congress organized from 26 to 30 August 2024 on Terceira Island, Portugal; Special Session S41. Assessing the economic impacts of tourism. The authors thank Antonio Zelić, PhD, Lidija Petrić, PhD, and Nora Mustać, PhD for assistance in in-depth interviews’ organization (participant recruitment).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EU |

European Union |

| IRTS 2008 |

International Recommendation for Tourism Statistics from 2008 |

References

- European Environmental Agency. Europe's seas and coasts. 2020. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/themes/water/europes-seas-and-coasts/europes-seas-and-coasts (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- European Boating Industry. Facts & Figures. 2024. Available online: https://www.europeanboatingindustry.eu/about-the-industry/facts-and-figures (assessed 15 July 2024).

- European Commission: Directorate-General for Maritime Affairs and Fisheries, Deloitte, ICF, IEEP, Marine South East and Sea Teach. Assessment of the impact of business development improvements around nautical tourism – Final report. 2017. Publications Office: Luxemburg City, Luxemburg. Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2771/26485 (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Gómez, A. G.; Balaguer, P.; Fernández-Mora, À.; Tintoré, J. Mapping the nautical carrying capacity of anchoring areas of the Balearic Islands’ coast. Marine Policy 2023, 155. [CrossRef]

- Luković, T. Nautical tourism and its function in the economic development of Europe. In Visions for Global Tourism Industry–Creating and Sustaining Competitive Strategies; Kasimoglu, M., Ed.; InTech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2012, pp. 399-430.

- Spinelli, R.; Benevolo, C. Towards a new body of marine tourism research: A scoping literature review of nautical tourism. Journal of outdoor Recreation and Tourism 2022, 40. [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, L.; Lopes, E.; Almeida, G. G. F. D.; Lima Santos, L.; Sousa, B.; Simões, J.; Perna, F. Features of nautical tourism in Portugal—Projected destination image with a sustainability marketing approach. Sustainability 2023, 15(11). [CrossRef]

- Moreno, M. J.; Otamendi, F. J. Fostering Nautical Tourism in the Balearic Islands. Sustainability 2017, 9 (12), pp. 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, R. M. M.; Milán García, J.; De Pablo Valenciano, J. Analysis and trends of global research on nautical, maritime and marine tourism. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 2021, 9(1), 93. [CrossRef]

- Benevolo, C. Problematiche di sostenibilità nell'ambito del turismo nautico in Italia. Impresa Progetto-Electronic Journal of Management 2011, (2), Available online: https://www.impresaprogetto.it/sites/impresaprogetto.it/files/articles/2_-_2011_-_wp_benevolo.pdf (assessed July 15 2024).

- Marusic, Z.; Ivandic, N.; Horak, S. Nautical Tourism within TSA framework: case of Croatia. In Proceedings of the 13th Global Forum on Tourism Statistics, Nara, Japan, 17-18 November 2014 (pp. 1-15).

- Sidman, C. F.; Fik, T. J. Modeling spatial patterns of recreational boaters: vessel, behavioral, and geographic considerations. Leisure Sciences 2005, 27(2), 175-189. [CrossRef]

- Beardmore, B. Boater perceptions of environmental issues affecting lakes in Northern Wisconsin. JAWRA Journal of the American Water Resources Association 2015, 51(2), 537-549. [CrossRef]

- Luković, T. Nautical tourism–definition and classification. Ekonomski pregled 2007, 58(11), 689-708, Available online: https://hrcak.srce.hr/18087 (assessed July 15 2024).

- Horak, S. (2014). Turizam i promet. Vern: Zagreb, Croatia, 2014; p. 264.

- Frechtling, D. C. The tourism satellite account: A primer. Annals of Tourism Research 2010, 37(1), 136-153. [CrossRef]

- Horak, S.; Marusic, Z.; Favro, S. Competitiveness of Croatian nautical tourism. Tourism in Marine Environments 2006, 3(2), 145-161. [CrossRef]

- Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2011/692/oj (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- United Nations and World Tourism Organization. International Recommendations for Tourism Statistics 2008 (IRTS 2008); United Nations: New York, USA, 2010; Available online: https://unstats.un.org/unsd/publication/seriesm/seriesm_83rev1e.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Eurostat. Methodological manual for tourism statistics, Version 3.1, 2014; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/3859598/6454997/KS-GQ-14-013-EN-N.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Masiero, L. International tourism statistics: UNWTO benchmark and cross-country comparison of definitions and sampling issues. Statistics and TSA: Issue Paper Series, 2016.

- Pratt, S.; Tolkach, D. The politics of tourism statistics. International Journal of Tourism Research 2018, 20(3), 299-307. [CrossRef]

- Antolini, F.; Grassini, L. Issues in tourism statistics: A critical review. Social Indicators Research 2020, 150(3), 1021-1042. [CrossRef]

- Antolini, F.; Grassini, L. Methodological problems in the economic measurement of tourism: the need for new sources of information. Quality & Quantity 2020, 54(5-6), 1769-1780. [CrossRef]

- Department of Economic and Social Affairs, United Nations. International Recommendations for Tourism Statistics 2008: Compilation Guide. Statistical Papers (Ser. M) No. 94. United Nations: New York, USA, 2016; p. 295, Available online: https://unstats.un.org/unsd/tradeserv/tourism/E-IRTS-Comp-Guide%202008%20For%20Web.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Smith, S. L. How far is far enough? Operationalizing the concept of “usual environment”. Tourism Analysis 1999, 4(3-4), 137-143.

- Govers, R.; Van Hecke, E.; Cabus, P. Delineating tourism: Defining the usual environment. Annals of Tourism Research 2008, 35(4), 1053-1073. [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Kim, N.; Chen, C. C.; Schwartz, Z. Are you a tourist? Tourism definition from the tourist perspective. Tourism Analysis 2012, 17(4), 445-457. [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Soria, I. Being a tourist as a chosen experience in a proximity destination. Tourism Geographies 2016, 19(1), 96–117. [CrossRef]

- Suriñach, J.; Casanovas, J. A.; André, M.; Murillo, J.; Romaní, J. An operational definition of day trips: Methodological proposal and application to the case of the province of Barcelona. Tourism Economics 2019, 25(6), 964-986. [CrossRef]

- Feifer, M. Going places. The ways of the tourist from Imperial Rome to the present day. MacMillan London Limited: London, United Kingdom, 1985, p. 288.

- Jansson, A. Rethinking post-tourism in the age of social media. Annals of Tourism Research 2018, 69, 101-110. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Guo, Z.; Cai, J.; Liu, H.; Luo, Q. Post-tourism in the usual environment: From the perspective of unusual mood. Tourism Management 2022, 89. [CrossRef]

- Diakomihalis, M. N. Greek maritime tourism: evolution, structures and prospects. Research in Transportation Economics 2007, 21, 419-455. [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, R. M. M. Nautical tourism: a bibliometric analysis. Journal of Spatial and Organizational Dynamics 2020, 8(4), 320-330, Available online: https://www.cieo.pt/journal/J_4_2020/article4.pdf (assessed July 15 2024).

- Luna-Cortes, G. Research on yachting: a systematic review of the literature. Tourism in Marine Environments 2023, 18(1-2), 47-58. [CrossRef]

- The Italian Government Tourist Board. Marine tourism in Italy, 2024. Available online: https://www.enit.it/en/marine-tourism-in-italy (assessed July 15 2024).

- Itransporte. Coastal beauties, 2021. Available online: https://www.revistaitransporte.com/index.html@p=4664.html (assessed July 15 2024).

- Statista. Berths in French maritime ports 2018, by maritime area, 2023. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1233963/number-berths-ports-france-maritime-area (assessed July 15 2024).

- Croatian Bureau of Statistics. Nautical Tourism – Capacity and Turnover of Ports, 2023, 2024. Available online: https://podaci.dzs.hr/2023/en/58174 (assessed July 15 2024).

- Ministry of the Sea, Transport and Infrastructure. Nacionalni plan razvoja luka otvorenih za javni promet od županijskog i lokalnog značaja, 2016. Available online: https://mmpi.gov.hr/UserDocsImages/arhiva/PREZENTACIJA%20FDR%20-FINAL.pptx10112016.pdf (assessed July 15 2024).

- Ministry of the Sea, Transport and Infrastructure. CIMIS base (internal data), 2023.

- Ministry of the Sea, Transport and Infrastructure. Statistical report: number of registered boats on 2018-01-22 according to organizational units for all harbormasters’ offices (internal data), 2018.

- Croatian Bureau of Statistics. Tourist Activity of the Population of the Republic of Croatia in 2022, 2023. Available online: https://podaci.dzs.hr/2023/en/58194 (assessed July 15 2024).

- Croatian Bureau of Statistics. Census 2021, 2022. Available online: https://podaci.dzs.hr/en/statistics/population/census/ (assessed July 15 2024).

- Ivandić, N.; Marušić, Z. Implementation of tourism satellite account: Assessing the Contribution of Tourism to the Croatian Economy. In Evolution of Destination Planning and Strategy: The Rise of Tourism in Croatia, Dwyer, L., Tomljenović, R., Čorak, S., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2017, pp. 149-171. [CrossRef]

- Jennings, G. Sailing/cruising. In Water-Based Tourism, Sport, Leisure, and Recreation Experiences, Jennings, G., Ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, United Kingdom, 2007, pp. 23-45. [CrossRef]

- Gammon, S. Key components of sport tourist experiences. In Routledge Handbook of the Tourist Experience, Sharpley, R., Ed., Routledge: London and New York, 2021, pp. 424-437. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/363093546.

- Carreño, A.; Lloret, J. Environmental impacts of increasing leisure boating activity in Mediterranean coastal waters. Ocean & Coastal Management 2021, 209. [CrossRef]

- Cerchiello, G. The sustainability of recreational boating. The case study of anchoring boats in Jávea (Alicante). Revista Investigaciones Turísticas 2018, 16, 165-195, DOI. [CrossRef]

- Trstenjak, A.; Žiković, S.; Mansour, H. Making nautical tourism greener in the Mediterranean. Sustainability 2020, 12(16), 6693. [CrossRef]

- Ukić Boljat, H.; Grubišić, N.; Slišković, M. The impact of nautical activities on the environment—A systematic review of research. Sustainability 2021, 13(19). [CrossRef]

- Figini, P.; Patuelli, R. Estimating the economic impact of tourism in the European Union: Review and computation. Journal of Travel Research 2022, 61(6), 1409-1423. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).