1. Introduction: The Taming of the Infinite

Infinity has haunted human thought for millennia, often viewed as a paradoxical notion (Moore, 2018). Georg Cantor (1890) subjected infinity to mathematical treatment, developing set theory and establishing a formal system for comparing infinite sets using one-to-one correspondence, or bijection (Dauben, 2020).His earth-shattering conclusion was that not all infinities are created equal. He proved the existence of a smallest infinity, Aleph-null (ℵ₀), the cardinality of the set of natural numbers, and demonstrated that the infinity of the real number continuum (c) was demonstrably larger (Cantor, 1890).

This "paradise" that Cantor created, as David Hilbert famously called it, became the bedrock of 20th-century mathematics (Cohen, 2024). Yet, this paradise was not without its serpents. Critics like Leopold Kronecker and Henri Poincaré recoiled from the abstract, non-intuitive nature of "actual" infinities—completed, static totalities that exist independently of any human or mechanical process (Darrigol, 2024). They championed a more classical, Aristotelian view of "potential" infinity: a process that can be continued indefinitely but is never finished (Builes & Wilson, 2022).

Early critiques were philosophical, but fractal geometry, developed by Benoît Mandelbrot in the late 20th century, offered a powerful language for dissent. Fractals depict infinity through geometric complexity, process, and structure rather than abstract cardinality.This article explores how fractal geometry serves as a profound counterargument to the hegemony of the Cantorian worldview, suggesting that its focus on "how many" overlooks the equally vital question of "how complex."

2. The Cantorian Edifice: An Infinity of Discrete Quantities

At the heart of Cantorianism is a radical conceptual leap: treating infinite sets as complete, self-contained objects, or actual infinities (Builes & Wilson, 2022). The primary tool for comparing these objects is not traditional measurement but bijection. If a one-to-one mapping can be found between the elements of two sets, they are declared to have the same cardinal number, regardless of their apparent structure. This leads to counter-intuitive results, such as the set of even numbers being the same size as the set of all natural numbers, and the set of rational numbers being no larger than either (Poincaré, 2024).

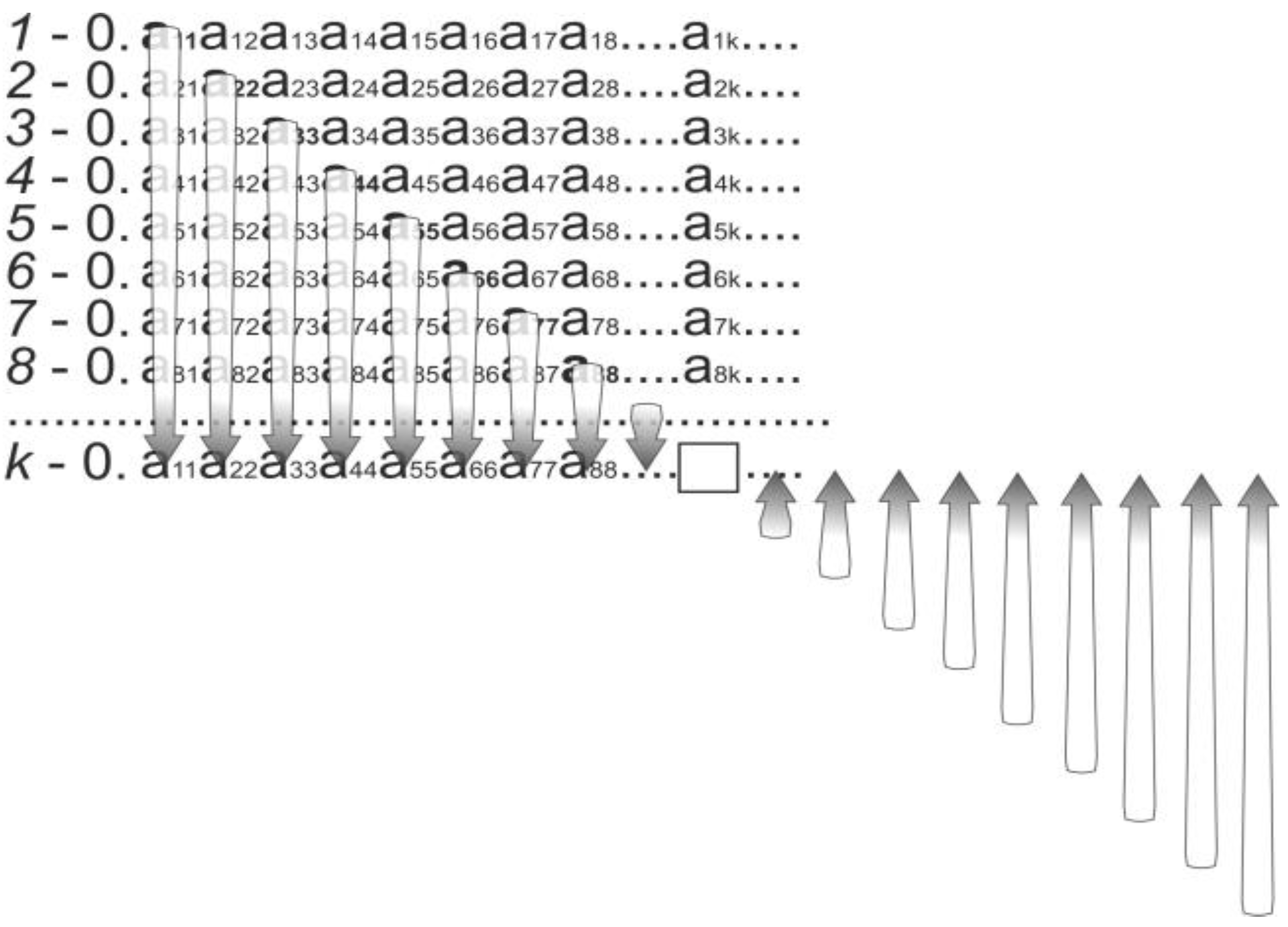

Cantor's most celebrated proof, the diagonal argument, established the uncountability of the real numbers, thereby proving a fundamental schism in the infinite. He demonstrated that no bijection could ever be constructed between the natural numbers (ℵ₀) and the real numbers on a line segment [0,1], whose cardinality is the continuum, c (Farmelo, 2019).

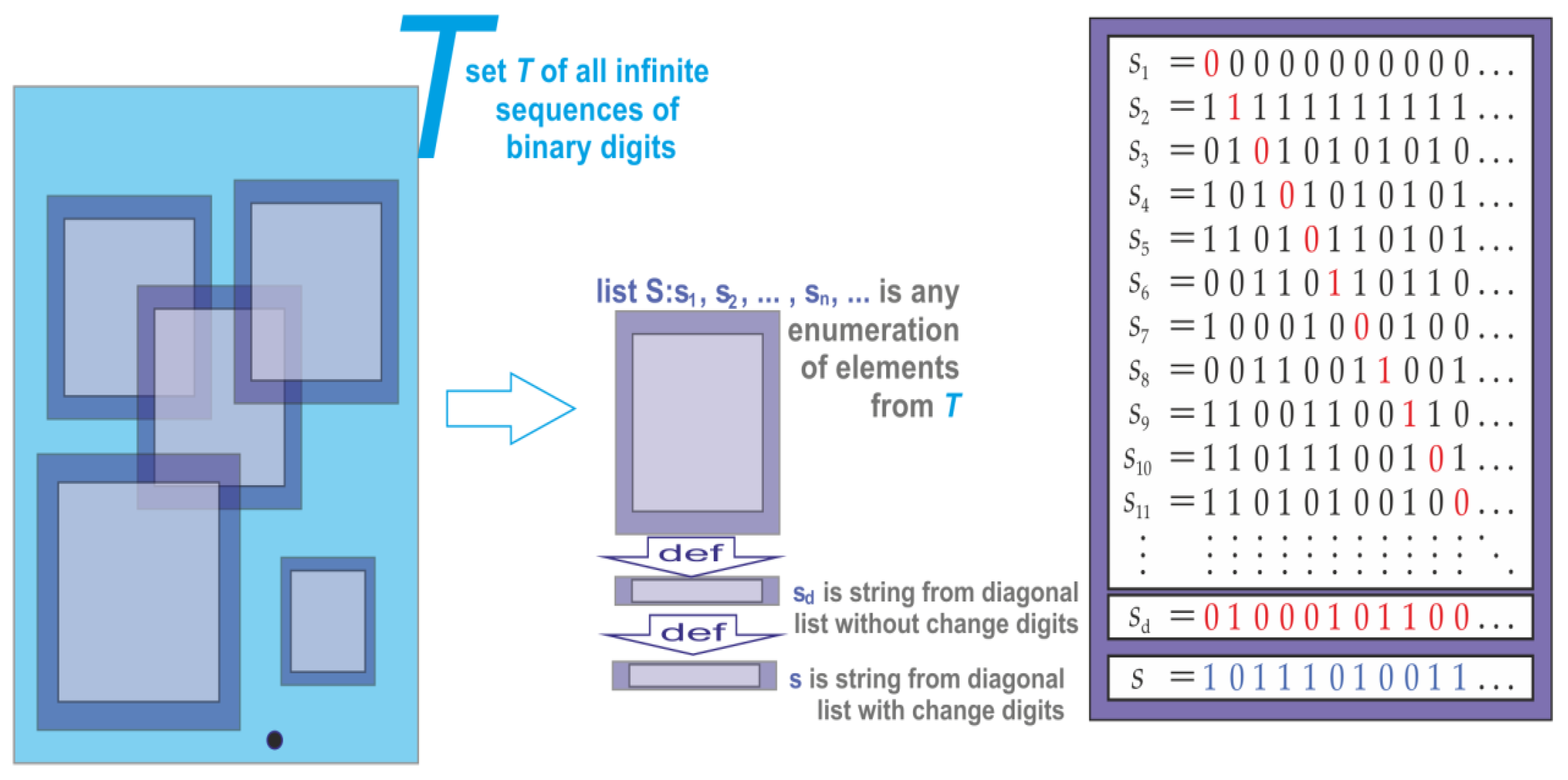

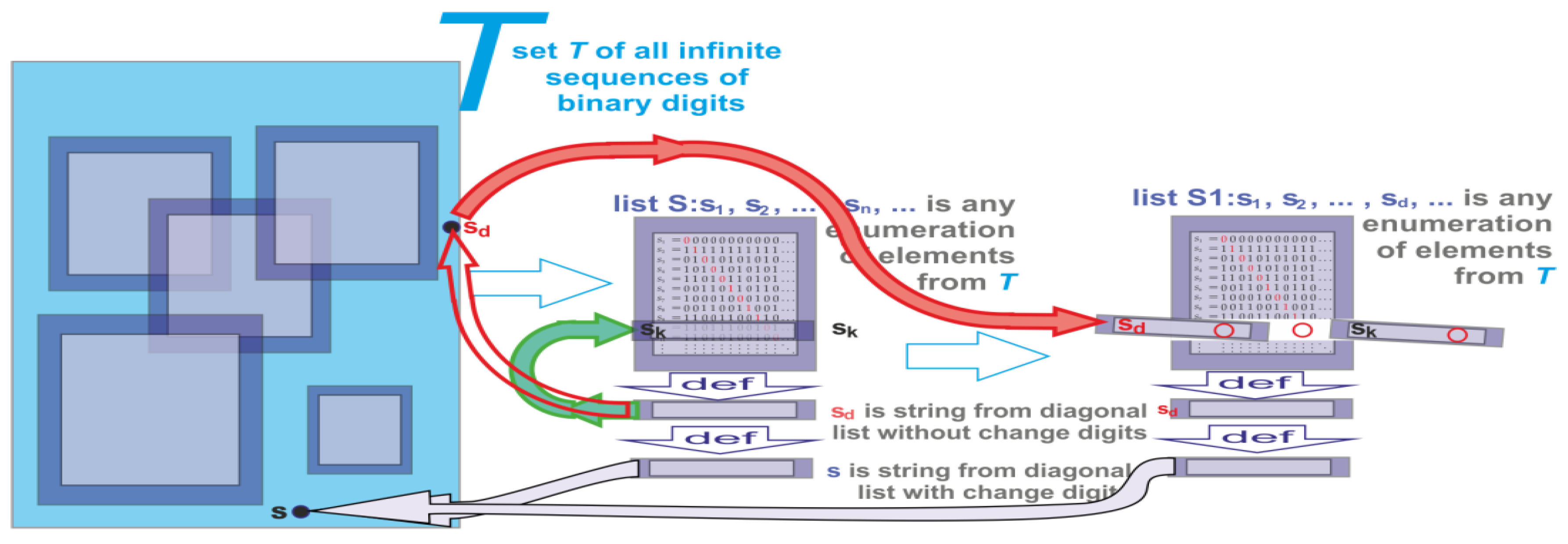

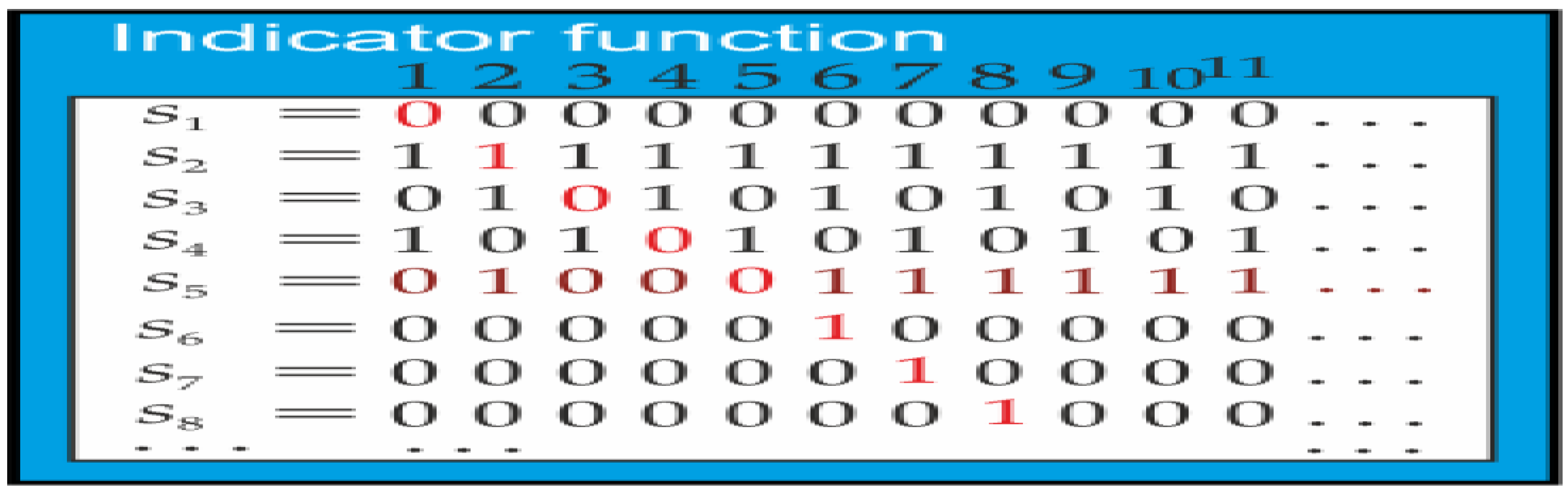

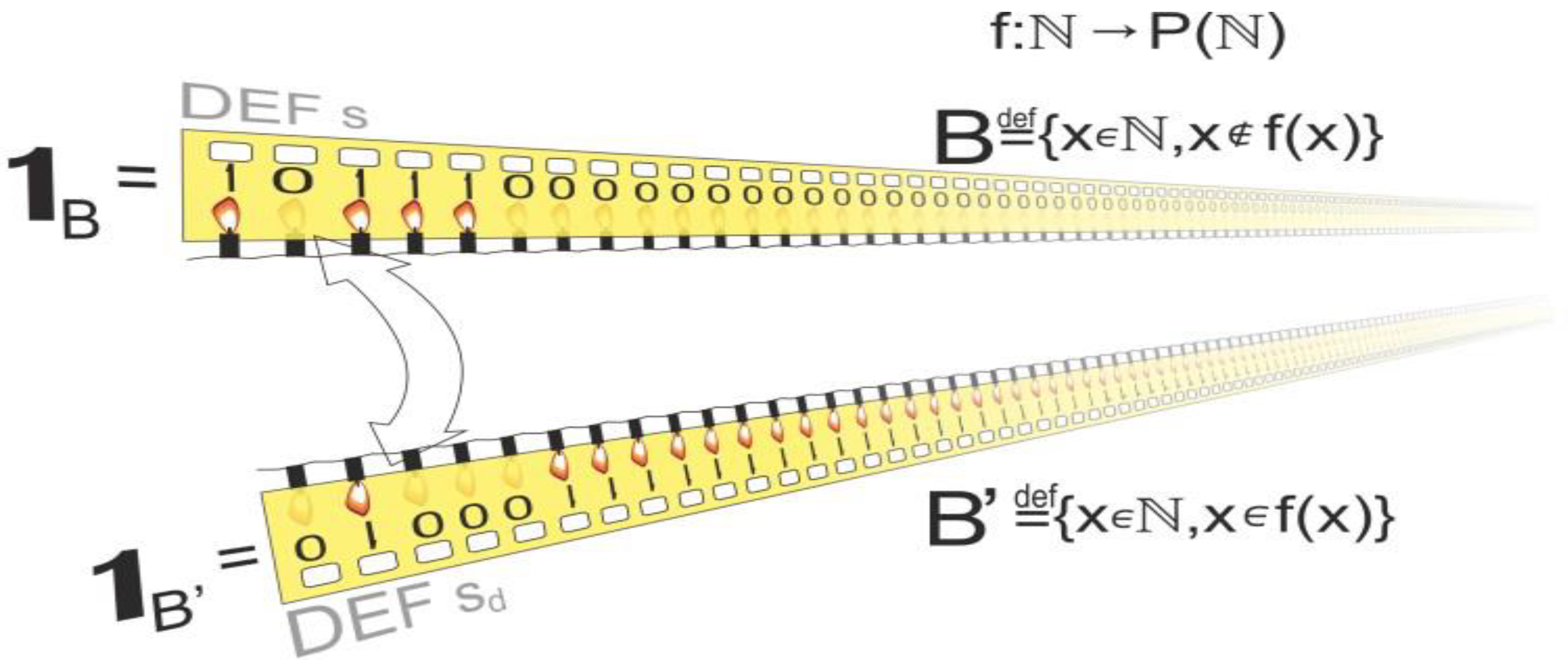

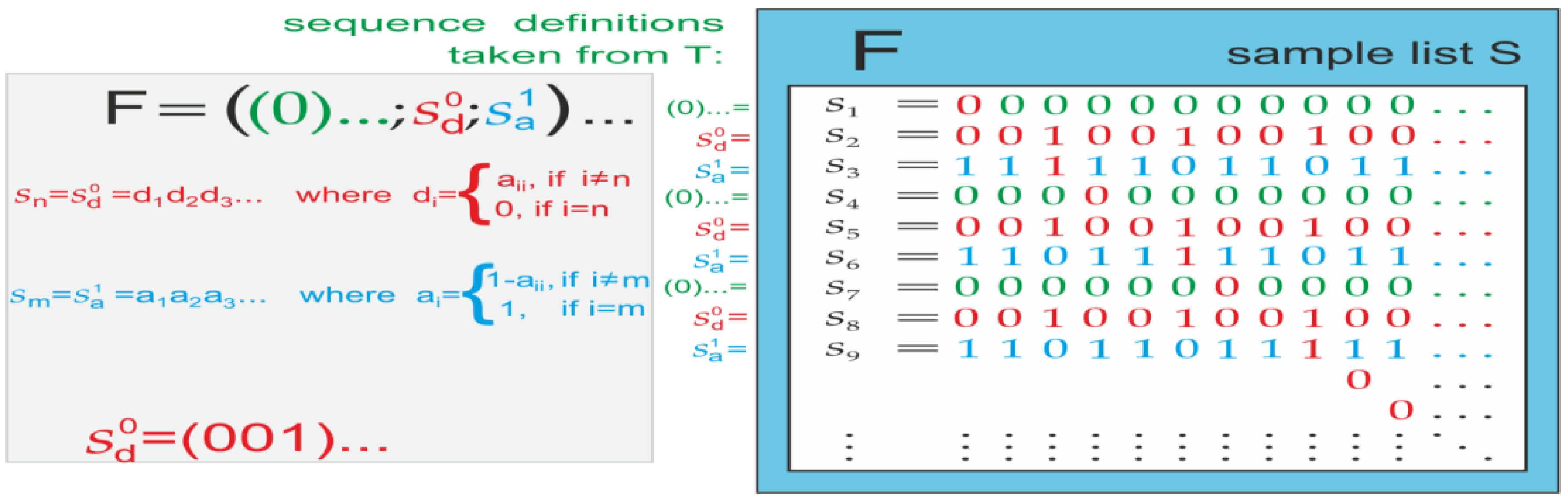

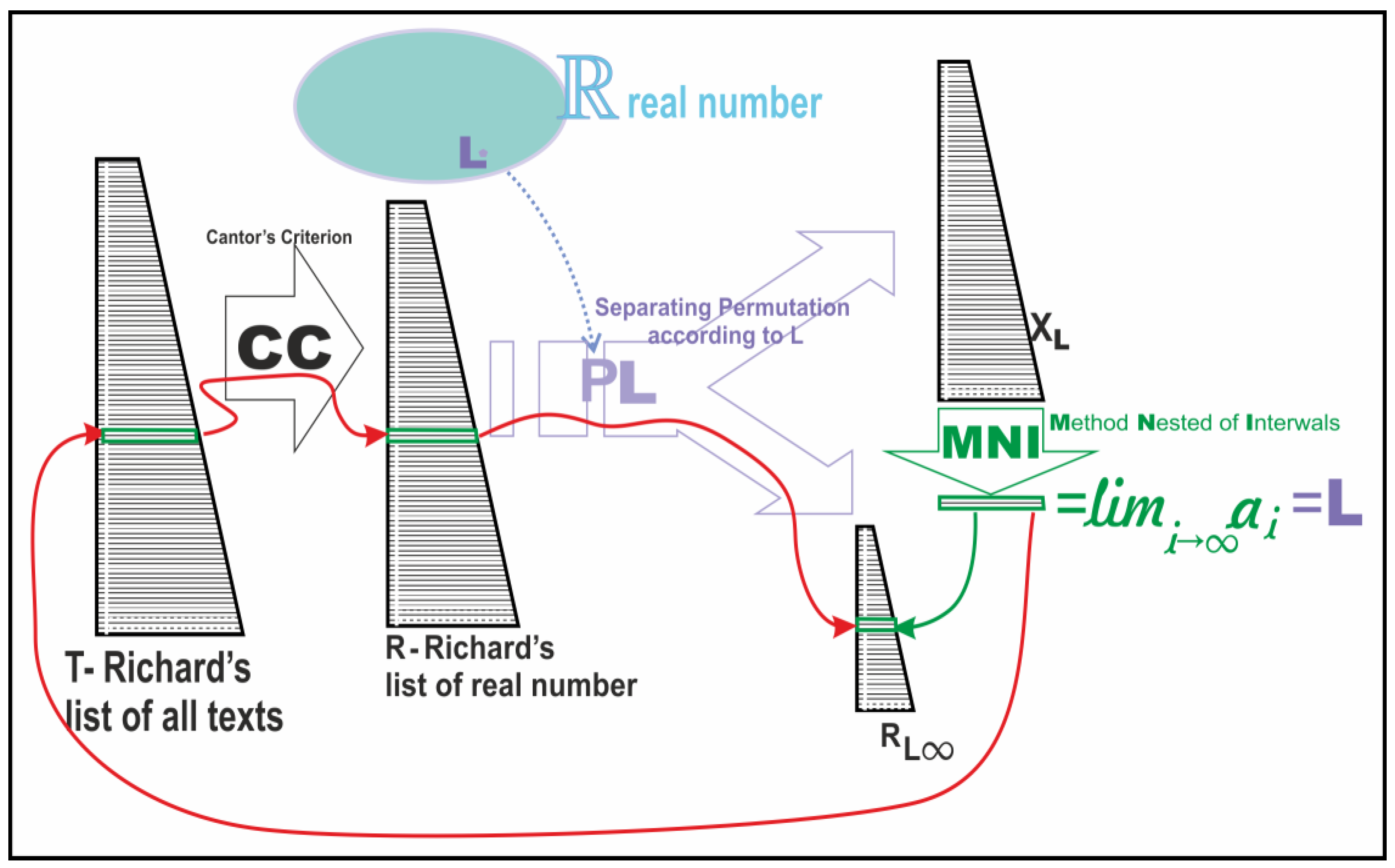

In (Burkiet, 2025), the author discussed Cantor's lemma using modern symbols to explain how infinite sequences of 0s and 1s can represent all possible subsets of natural numbers (ℕ). Cantor's diagonal argument (CDA) claims that for any list of these sequences, you can create a new sequence that differs from every sequence in the list, showing that not all subsets can be listed (i.e., some are uncountable). The author points out that Cantor's assumption that his method works for any complete list is flawed, as it is possible to construct a list where his diagonal method fails. Delving into visualisation, it is suggested to look at

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 (Burkiet, 2025).

Figure 1 illustrates Cantor's Diagonal Argument (CDA), showing that some sets, like real numbers, are "uncountable" and cannot be listed like natural numbers. The figure highlights how CDA constructs a new number differing from each list number, proving no complete list of real numbers exists.

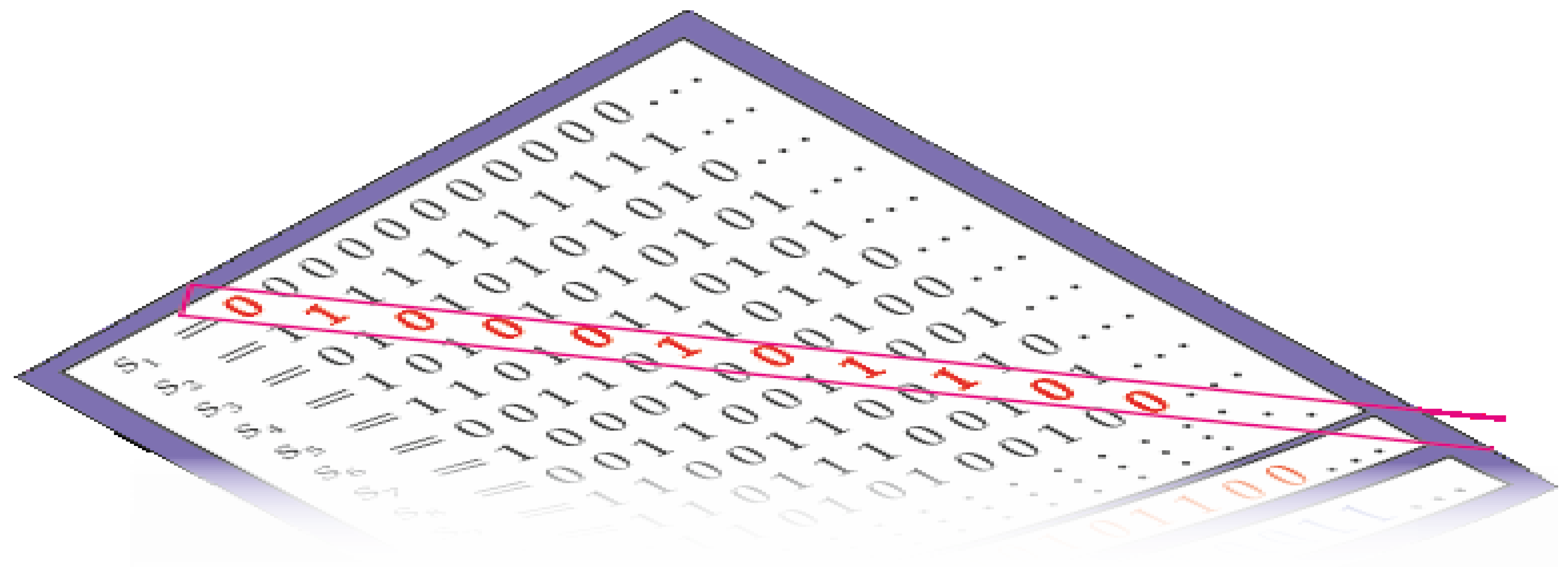

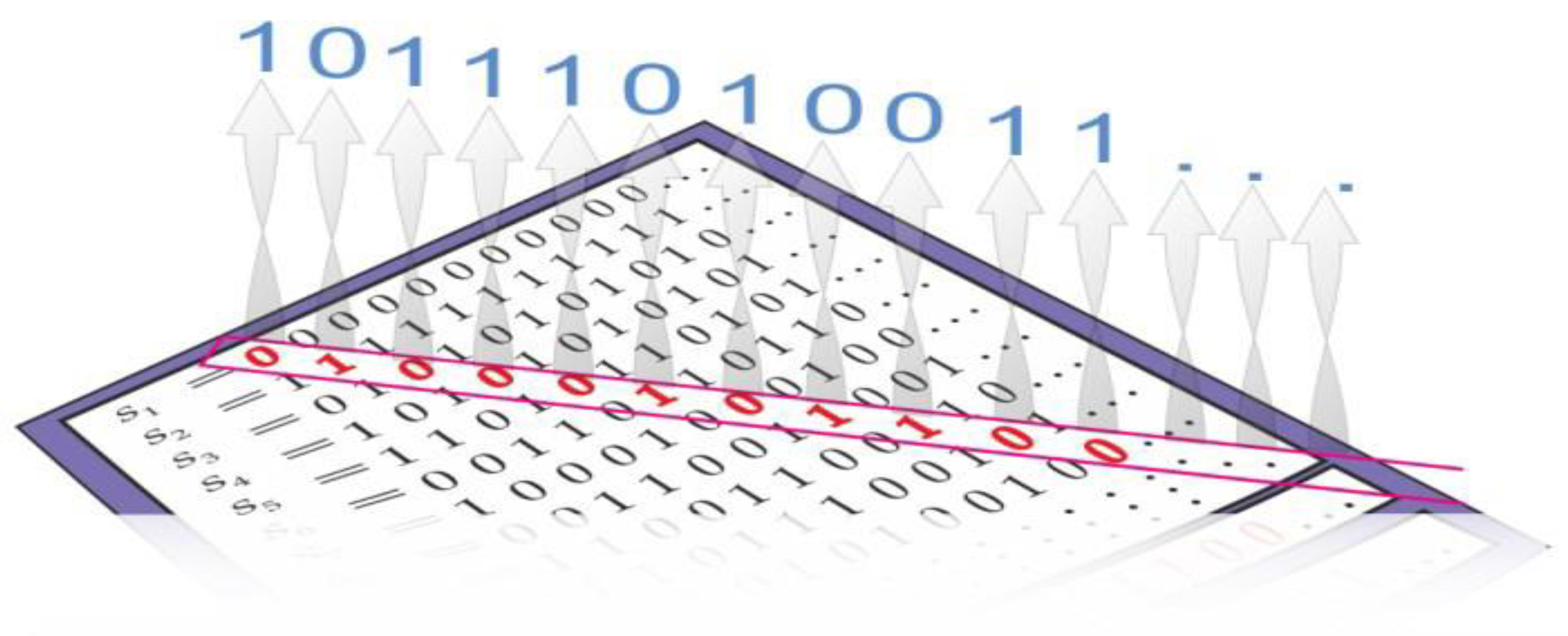

Extracting the diagonal is a key step in Cantor's Diagonal Argument (

Figure 2), which shows some sets are uncountable. It involves creating a new sequence from the diagonal of a two-dimensional list of sequences. This new sequence differs from every sequence in the original list, proving that not all sequences can be listed, demonstrating the existence of uncountable sets.

Changing digits from diagonal to antidiagonal is a method in CDA. Instead of selecting diagonal digits, you choose antidiagonal digits (

Figure 3), creating a new number that differs from each original list number at one digit. This demonstrates the list cannot contain all possible numbers, highlighting that there are more real numbers than can be counted, leading to uncountable sets.

The existence of a list containing a diagonal string for any antidiagonal refers to a concept in CDA, which shows that you can create a new sequence (the diagonal) from a list of sequences. This new sequence differs from each entry in the list at least at one position, meaning it cannot be found in the original list. This idea is used to demonstrate that there are more real numbers than natural numbers, suggesting the existence of uncountable sets. This is showcased through

Figure 4.

Figure 5 demonstrates the Indicator functions as mathematical tools used to represent whether elements belong to a specific subset. For a given set, the indicator function assigns a value of 1 to elements that are in the set and a value of 0 to those that are not. In the context of Cantor's work, the indicator function helps illustrate properties of sets, particularly when examining contradictions related to uncountable sets and their complements.

Figure 6 visualises how CDA would provide a new set, called set B, by changing the characters on the diagonal of a list to their opposites. Set B cannot be part of the original list, leading to a contradiction of uncountable sets. The author (Burkiet, 2025) explained equivalent definitions describe sets without changing elements, clarifying relationships between sets and their complements.

Real numbers are the set of numbers that include all the rational numbers (like fractions) and all the irrational numbers (like the square root of 2 or

), which cannot be expressed as simple fractions. Inserting a diagonal definition in line

refers to CDA, where a new real number is created by changing the digits of the numbers listed in a sequence, ensuring that this new number differs from each number in the list at least at one position. This process demonstrates that there are more real numbers than natural numbers, leading to the conclusion that real numbers are uncountable, see

Figure 7.

.

In the context of CDA (Burkiet, 2025), a list with corrected diagonals and antidiagonals refers to a method of identifying elements in a sequence that are constructed to show how certain numbers can be excluded from a list, as in

Figure 8. Diagonal elements are from the original list; antidiagonal elements change each diagonal element, demonstrating more real numbers than can be listed, concluding that some sets are uncountable. This concept is central to understanding contradictions in infinity and uncountable sets.

The "Method of Nested Intervals" is a mathematical technique used to find points in a space by repeatedly narrowing down intervals that contain those points(See

Figure 9). The phrase "depriving the Method Nested of Interval of defective self-reference" suggests that the author is proposing a way to eliminate contradictions that arise from self-referential definitions within this method. Essentially, the goal is to refine the method so that it avoids ambiguities and contradictions, leading to clearer and more reliable results in identifying points within those intervals.

This elegant proof cemented a hierarchical vision of infinity: a ladder of transfinite cardinals (ℵ₀, ℵ₁, ℵ₂, …) where each successive Aleph is unimaginably larger than the last. The entire system, however, relies on accepting infinite sets as static, platonic objects. The line segment from [0,1] is not seen as a space to be traversed but as a pre-existing, complete collection of points. This abstraction detaches infinity from physical or geometric intuition, a move that many found deeply unsettling (Lv , 2024; Ratcliffe, 2024). The Cantorian framework is essentially a quantitative science of the infinite; it counts points.

3. The Fractal Perspective: Infinity as a Generative Process

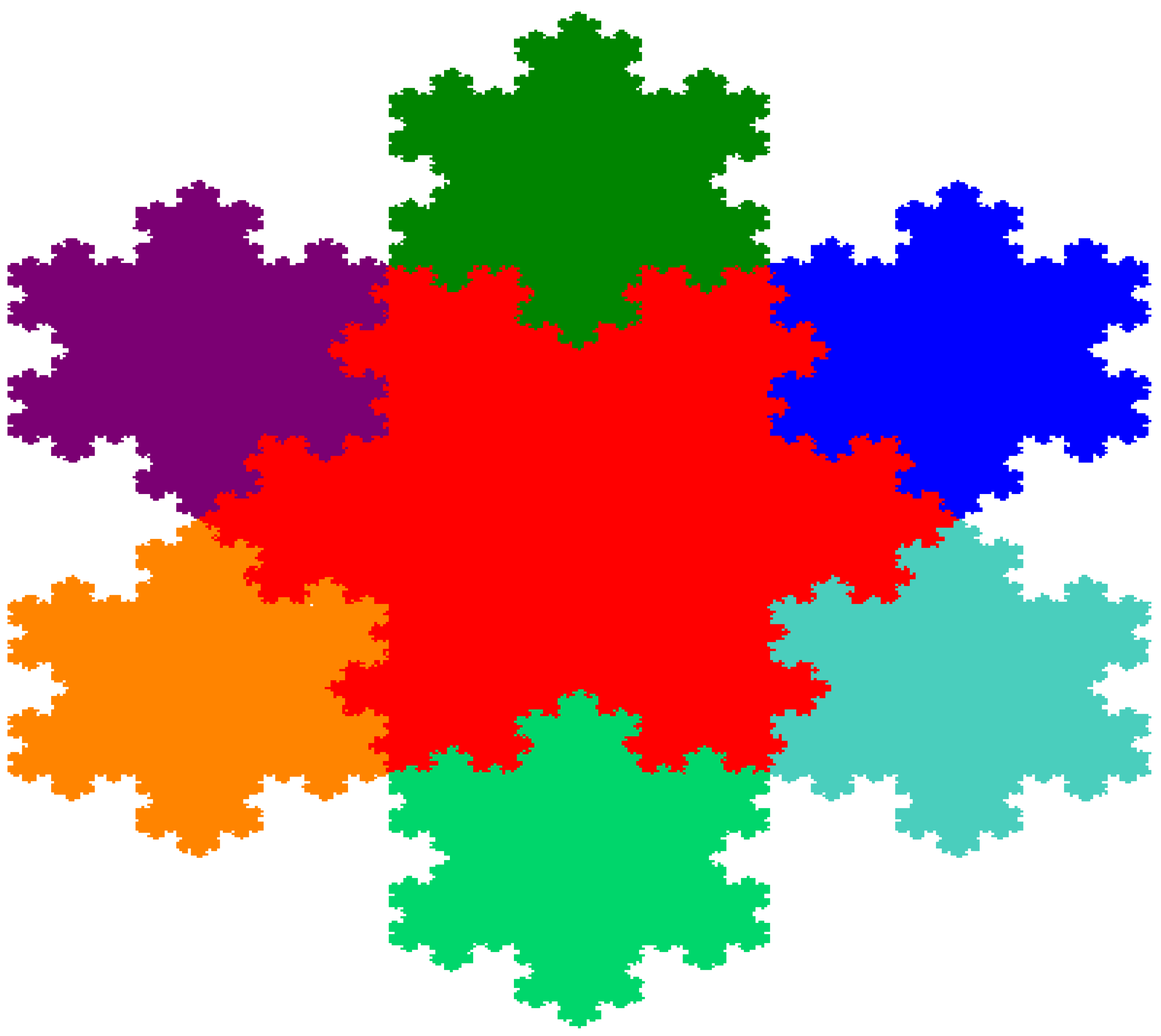

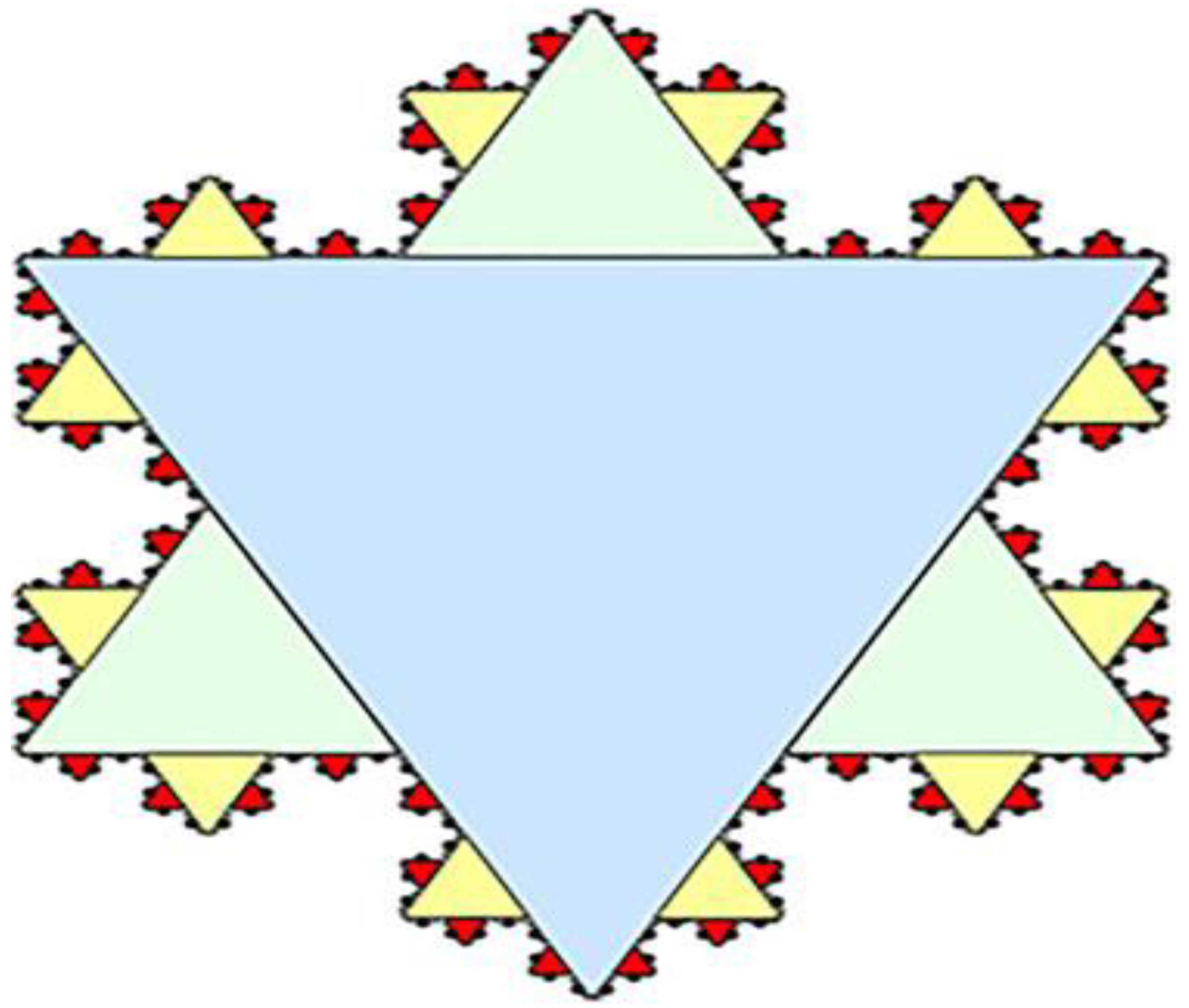

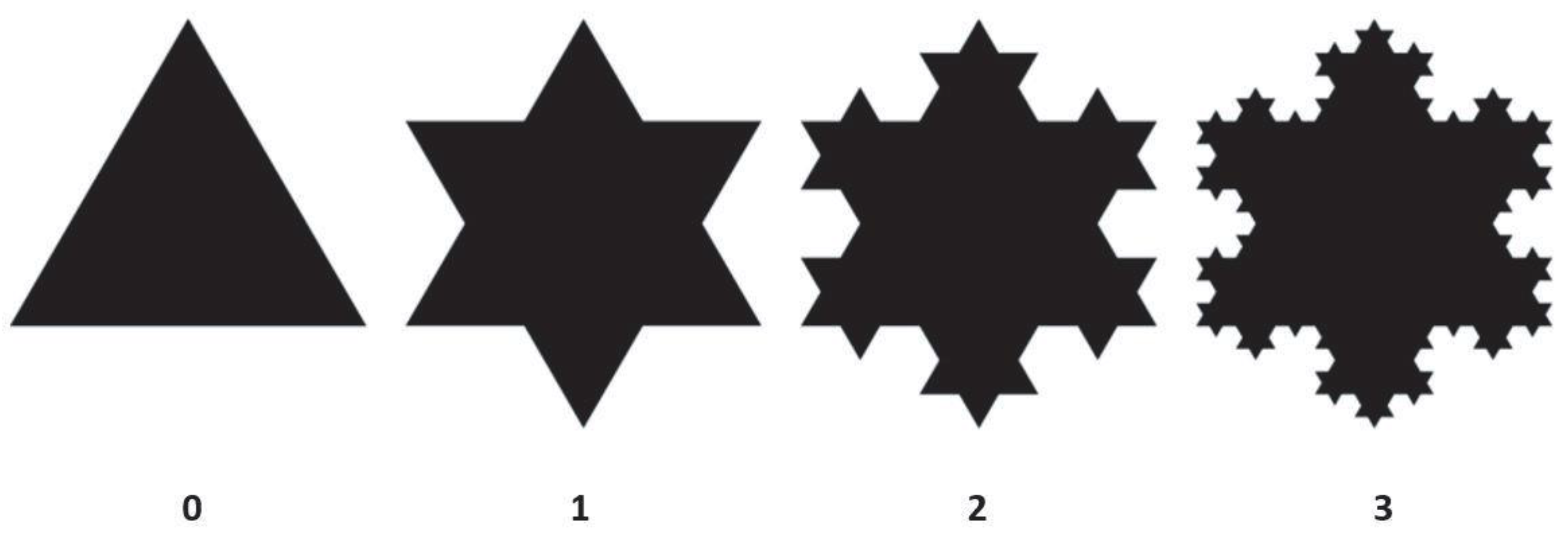

Fractal geometry, as articulated by Mandelbrot and combined with educatory mathematics(Mageed and Bhat, 2022; Mageed, 2023; Mageed, 2024 a-m, Mageed and Li, 2025; Mageed, 2025 a-m), offers a starkly different conception of infinity. A fractal is a geometric object characterized by self-similarity across all scales and, most critically, a non-integer dimension (Fraser, 2020). Unlike the smooth, idealized shapes of Euclidean geometry, fractals are rough, fragmented, and infinitely complex. Consider the Koch Snowflake, a classic fractal construction.

One begins with an equilateral triangle. In the first iteration, the middle third of each side is replaced with two new sides, forming a smaller equilateral triangle pointing outwards. This process is then repeated on every new line segment, ad infinitum (Peitgen et al., 2004).

In the late twentieth century, Benoit Mandelbrot (Mageed and Bhat, 2022; Mageed, 2023; Mageed, 2024 a-m, Mageed and Li, 2025; Mageed, 2025 a-m) revolutionised the intriguing world of fractals, which are objects that exhibit self-similarity across different scales. One of the most stunning examples in this category is the Koch Snowflake, as depicted in

Figure 10(Husain et al., 2021) and

Figure 11 (c.f., Peitgen et al., 2004), a wonderful work of grace and clarity. The amazing geometry of Koch snowflake is manifested through visualisation.

The Koch curve presents a direct challenge to classical and Cantorian thinking. At each step of its construction, the total length of the curve increases by a factor of 4/3. It all begins with an equilateral triangle known as the initiator. In each stage of the process, or iteration, the middle third of each line segment is changed by two sides of a smaller equilateral triangle pointing outward—this is known as the generator.

As the number of iterations approaches infinity, the curve's length also approaches infinity. Yet, this infinitely long line encloses a finite, calculable area (Akhmet et al., 2020). This paradox immediately highlights the inadequacy of traditional measurement.

And this process goes on forever (von Koch, 1904; Aravindraj et al., 2023). The visual illustration is showcased by

Figure 12(c.f., Aravindraj et al., 2023).

What’s truly remarkable about the Koch snowflake is that it has two well-known properties. First, its perimeter is infinite. The boundary length rises by a factor of with each iteration, resulting in an ever-expanding perimeter as the iterations continue indefinitely. Second, despite its infinite perimeter, the area is finite, eventually reducing to (8/5) the area of the original triangle (Akhmet et al., 2020). This intriguing mix of finite and infinite measurements within a single geometric shape is a fundamental aspect of fractal geometry. Additionally, the Koch curve is continuous everywhere but differentiable nowhere, which posed a significant challenge to traditional calculus (Husain et al., 2022a, 2022b). It has a Hausdorff dimension of , which indicates its "roughness" or ability to fill space. This means that is more than simply a one-dimensional line but not nearly a two-dimensional plane (Bunimovich and Skums (2024). While these qualities are well understood, they pave the way for even more profound, unresolved concerns.

More profoundly, the Koch curve embodies potential infinity. It is not a static object but the result of an unending process. Its "existence" is defined by the algorithm that generates it. One cannot "hold" the completed object; one can only understand its generative rule and its properties at the limit (Venegas Aravena & Cordaro, 2025). This stands in direct opposition to Cantor's insistence on the actual, completed infinite. For the fractalism, infinity is not a destination but a journey of infinite recursion (Su, 2020).

This process-oriented view culminates in the concept of fractal dimension, or Hausdorff dimension (Edgar, 2019). While a line is one-dimensional and a plane is two-dimensional, the Koch curve has a dimension of log(4)/log(3) ≈ 1.26. This non-integer value provides a measure of its complexity and space-filling capacity. It tells us how it occupies space, a quality entirely missed by Cantorian cardinality. From a Cantorian perspective, the set of points on the Koch curve has the same cardinality (c) as a simple straight line (Mageed and Bhat, 2022; Mageed, 2023; Mageed, 2024 a-m, Mageed and Li, 2025; Mageed, 2025 a-m).The formalist sees no difference in their "size." The geometer, however, sees a universe of difference in their structure, a difference elegantly captured by the fractal dimension.

4. Juxtaposing the Infinities: Cardinality vs. Complexity

The conflict between Cantorian formalism and the fractal perspective is thus a conflict of foundational questions. Cantor asks, "How many points?" while the fractal geometer asks, "How is the structure organized?" and "How does it fill space?" (Weinberg, 2022).Let us visualize this contrast. Imagine two sets of points, both with cardinality c. • Set A: The points on a smooth line segment from [0,1]. This is the canonical Cantorian continuum. It is uniform, simple, and one-dimensional. • Set B: The points on a space-filling curve, such as the Peano curve, or a highly complex fractal like the boundary of the Mandelbrot set.

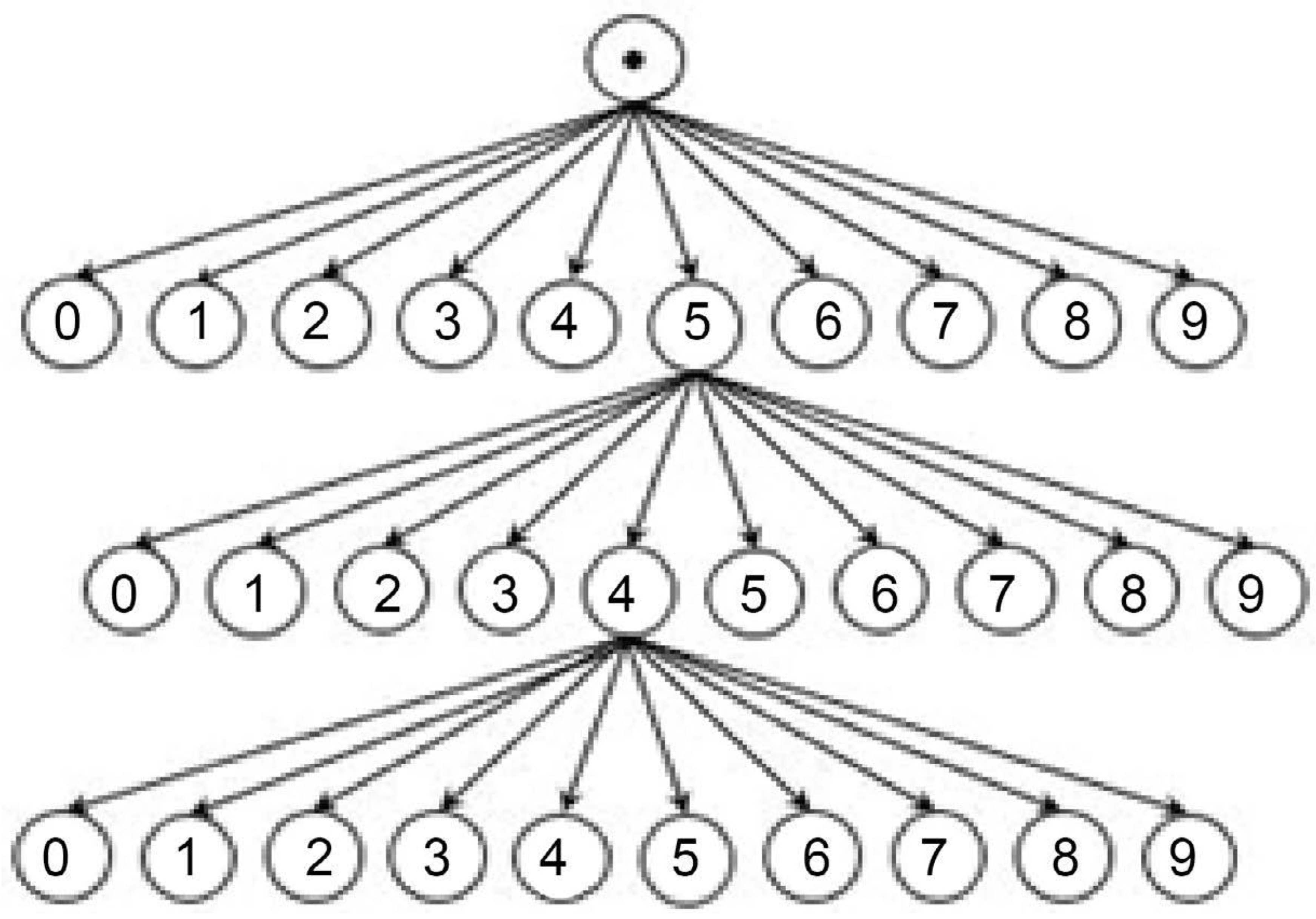

The work of (Jackson, 2025) discussed different types of infinity, focusing on "countable infinity," which includes natural numbers (like 0, 1, 2, 3, ...) and the spaces on a Turing machine's tape. It argues that the infinite paths in an "infinity tree," which represent decimal numbers between 0 and 1, can be written down on a Turing machine's tape, showing that these paths are also countably infinite. The author emphasizes that this approach does not consider decimal equivalences (like 0.3999... being the same as 0.4000...) and concludes that the set of numbers in the range [0, 1] is countably infinite.

The "infinity tree" (Jackson, 2025) is a conceptual structure used to represent the real numbers between 0 and 1 (See

Figure 13(c.f., Jackson, 2025). It starts with a root node labelled as a decimal point (0), and each node branches out to 10 unique nodes labelled with the digits 0 through 9, creating a tree-like pattern. This structure is designed so that no two nodes point to the same node, ensuring a clear and non-repeating path through the tree, which helps in understanding the concept of countability in mathematics.

The Turing machine (Jackson, 2025) uses twelve infinite tapes to efficiently process paths in the infinity tree. One tape serves as the input, containing decimal representations of paths from the root node to a certain level, while other serves as the output for the next level. The remaining ten tapes, called branch tapes, help extend these paths to the child nodes, allowing the machine to systematically generate and store all paths through the tree as it progresses through each level.

The Turing machine described in the text is a theoretical model that can generate all the real numbers between 0 and 1 by writing them down on an infinite tape, using an infinite number of steps. This process suggests that the set of real numbers in that interval is countably infinite, meaning it can be matched with the natural numbers. Additionally, the text argues that the structure called the "infinity tree" also contains only a countable number of paths, indicating that every real number in that range can be generated by the Turing machine without missing any.

In discussion of a special type of Turing machine called an "infinite time Turing machine" (ITTM), which can perform calculations for an infinite number of steps while keeping track of the information it generates. This machine operates using a set of rules that dictate how it reads and writes symbols on a tape, allowing it to process an infinite sequence of tasks. The paper argues that this ITTM can generate all real numbers between 0 and 1 using a finite number of tapes and an infinite number of computation steps, challenging traditional views on the countability of real numbers.

In his work "What is Cantor’s Continuum Problem?", Gödel argues that Cantor's theory of cardinality(Parker, 2019), which states that two sets have the same number of elements if there is a one-to-one correspondence (bijection) between them, is uniquely valid. However, recent scholars have proposed alternative theories of cardinality that align with standard set theory (ZFC) and offer useful mathematical properties that Cantor's theory does not. The author critiques Gödel's argument by pointing out that its foundational assumptions are not strong enough to dismiss other perspectives and that Gödel's conclusion about the uniqueness of Cantor's theory is logically flawed.

In (Parker, 2019), the author discusses the concept of "cardinality," which refers to the number of elements in a collection. The central idea is that Cantor's Bijection Principle (BP) states that if two sets can be paired off one-to-one, they have the same number of elements. The author critiques Gödel's argument that Cantor's definition of cardinality is the only valid one, suggesting that there are alternative theories that challenge this view and that Gödel's reasoning has flaws, particularly in assuming that BP must apply universally to all sets.

The author (Parker, 2019) explored Gödel's argument about Cantor's definition of cardinality, which suggests that there should be a single definition of number that applies to all types of elements without considering their differences. However, the author argues that Gödel's reasoning is flawed because it doesn't convincingly dismiss other valid concepts of cardinality, and his conclusion that Cantor's definition is the only acceptable one is not well-supported. Ultimately, the author believes that while Gödel's argument is interesting, it fails to prove that Cantor's approach is uniquely correct or that we have no other reasonable options.

The main issue with Gödel's argument is that it relies on premises that are not universally accepted(Parker, 2019), particularly the idea that qualitatively similar sets should have the same number of elements. Critics argue that this assumption is not necessarily true and that different concepts of cardinality can be valid, especially in practical applications. Additionally, Gödel's conclusion that his theory of cardinality is the only acceptable one fails because it does not adequately consider alternative theories that might also be useful or intuitive.

(Parker, 2019) provided critiques Gödel's argument for why Cantor's definition of cardinality (the concept of counting sets) should be accepted as the only valid one. It points out that even if we agree with Gödel's starting points, his conclusion doesn't logically follow because he assumes that a principle that works for one type of objects (like physical ones) must apply to all types of objects, which isn't necessarily true. The author argues that there are alternative definitions of cardinality that could also be valid, showing that Gödel's reasoning is flawed.

Gödel's argument suggests that Cantor's Bijection Principle (BP) (Parker, 2019), which states that two sets have the same number of elements if there is a one-to-one correspondence between them, should apply to all sets, including those made of physical objects. However, the author argues that Gödel's reasoning is flawed because it doesn't adequately dismiss other valid theories of cardinality that may not follow BP but are still consistent with established set theory (ZFC). Ultimately, while Cantor's theory is significant and widely accepted, there are alternative approaches to understanding cardinality that also have merit and could be useful in different contexts.

According to Cantor's metric, Set A and Set B are equivalent in size. His system provides no language to describe the staggering difference in their geometric complexity, information content, and structural organization. Cantorian formalism flattens this rich topography into a single number: c (Rucker, 2019).

Fractal dimension, however, reveals the profound distinction. The simple line has a dimension of 1. A space-filling curve has a dimension of 2, indicating its plane-covering nature. The Mandelbrot set's boundary, one of the most complex objects in mathematics, also has a dimension of exactly 2 (Edgar, 2019), signifying a level of intricacy that far surpasses a simple line.

This is not a mathematical contradiction of Cantor's proofs. The bijections that equate the cardinality of sets are logically sound within their axiomatic system (Abarca, 2023). Rather, it is a philosophical and practical challenge to the sufficiency of that system. The fractal perspective argues that by focusing exclusively on cardinality, we gain a precise but impoverished understanding of the infinite. We learn the number of atoms in a statue but nothing of its form (Xiang et al., 2023). The visual and intuitive power of fractals serves as a constant reminder that infinity possesses qualities—like structure, depth, and generative potential—that transcend mere numerosity (Kessler, 2022).

5. Conclusions: Towards a Pluralistic Infinity

Cantorian formalism was a monumental achievement, providing a rigorous language for an aspect of infinity that had previously been intractable. Its model of a static, actual infinity composed of discrete points organized into a hierarchy of cardinalities remains a cornerstone of pure mathematics. However, the visual and conceptual universe revealed by fractal geometry serves as a powerful counter-narrative.Fractals re-center the discussion on process, complexity, and geometric intuition. They embody a potential infinity, one that is perpetually unfolding through iterative rules. Their non-integer dimensions provide a nuanced measure of structure that is completely invisible to the lens of cardinality. By placing a smooth line next to a Koch curve or the Mandelbrot set, we are visually confronted with the limitations of a purely quantitative description of the infinite.The argument is not that Cantor was "wrong," but that the Cantorian framework is not the only valid or useful way to conceptualize infinity. Just as non-Euclidean geometries did not invalidate Euclid but rather revealed its contextual limits, fractal geometry does not invalidate Cantor but rather highlights the specificity of his perspective (Aguiar e Oliveira Jr, 2022). The infinity of set theory is an infinity of abstraction and quantity. The infinity of fractals is an infinity of structure, process, and visual complexity. Acknowledging both allows for a richer, more pluralistic mathematics, one that embraces the infinite not as a single, settled concept, but as a deep and multifaceted domain that continues to unfold in surprising and beautiful ways.

References

- Abarca, J. A. L. (2023). Four axioms for a theory of rhythmic sets and their implications. Online Journal of Music Sciences 2023, 8, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar e Oliveira Jr, H. (2022). Deterministic sampling from uniform distributions with Sierpiński space-filling curves. Computational Statistics 2022, 37, 535–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhmet, M. , Fen, M. O., & Alejaily, E. M. Dynamics with chaos and fractals, Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Vol. 380. [Google Scholar]

- Aravindraj, E. , Nagarajan, G., & Ramanathan, P. (2023). Koch snowflake fractal embedded octagonal patch antenna with hexagonal split ring for ultra-wide band and 5G applications. Prog. Electromagn. Res. C 2023, 135, 95–106. [Google Scholar]

- Builes, D. , & Wilson, J. M. (2022). In defense of countabilism. Philosophical Studies 2022, 179, 2199–2236. [Google Scholar]

- Builes, D. , & Wilson, J. M. (2022). In defense of countabilism. >Philosophical Studies 2022, 179(7), 2199–2236. [Google Scholar]

- Bunimovich, L. , & Skums, P. (2024). Fractal networks: Topology, dimension, and complexity. Chaos: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Nonlinear Science, 2024; 34, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Burkiet, A. (2025). Identifying Cantor’s Diagonal Argument as an Antinomy: Exploring Complementary Analysis Techniques. Journal of Applied Mathematics and Computation, 2025; 9, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Cantor, G. (1890). Ueber eine elementare Frage der Mannigfaltigketislehre. Jahresbericht der Deutschen Mathematiker-Vereinigung 1890, 1, 72–78. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, H. (2024). The Principle of the Infinitesmal Method and Its History, BoD–Books on Demand.

- Darrigol, O. (2023). Poincaré and the reaction principle in electrodynamics. Philosophia Scientiæ, 2023; 272, 63–125. [Google Scholar]

- Dauben, J. W. (2020). Georg Cantor: His mathematics and philosophy of the infinite.

- Edgar, G. A. (2019). Classics on fractals, CRC Press.

- Edgar, G. A. (2019). Classics on fractals, CRC Press.

- Farmelo, G. (2019). The universe speaks in numbers: how modern maths reveals nature's deepest secrets, Faber & Faber.

- Fraser, J. M. (2020). Assouad dimension and fractal geometry, Cambridge University Press; Vol. 222.

- Hallett, M. (1984). Cantorian set theory and limitation of size. Clarendon Press.

- Husain, A. , Nanda, M. N., Chowdary, M. S., & Sajid, M. (2022a). Fractals: an eclectic survey, part-I. Fractal and Fractional, 2022a; 6, 2, 89. [Google Scholar]

- Husain, A. , Nanda, M. N., Chowdary, M. S., & Sajid, M. (2022b). Fractals: An eclectic survey, part II. Fractal and Fractional 2022b, 6(7), 379. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, P. C. (2025). Countability of Infinite Paths in the Infinity Tree: Proof of the Continuum Hypothesis in a Non-Cantorian Infinity Theory. Advances in Pure Mathematics 2025, 15, 73–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, V. (2022). Mathematics declaring the glory of God. Verbum et ecclesia 2022, 43, 2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, H. V. (1904). Sur une courbe continue sans tangente, obtenue par une construction géométrique élémentaire. Arkiv for Matematik, Astronomi och Fysik 1904, 1, 681–704. [Google Scholar]

- potential. Journal of Physics A: Mathematical and Theoretical.

- Lv, S. (2024). Formalism in the History of Philosophical Mathematics: Beyond Logicism and Intuitionism. perspectives 2024, 88. [Google Scholar]

- Mageed, I. A. , & Bhat, A. H. (2022). Generalized Z-Entropy (Gze) and fractal dimensions. Appl. math 2022, 16, 829–834. [Google Scholar]

- Mageed, I. A. (2023). Fractal Dimension (Df) of Ismail’s Fourth Entropy (with Fractal Applications to Algorithms, Haptics, and Transportation. In 2023 international conference on computer and applications (ICCA) (pp. 1-6). IEEE.

- Mageed, I. A. (2024a). The Fractal Dimension Theory of Ismail's Third Entropy with Fractal Applications to CubeSat Technologies and Education. Complexity Analysis and Applications 2024, 1(1), 66–78. [Google Scholar]

- Mageed, I. A. (2024b). Fractal Dimension of the Generalized Z-Entropy of The Rényian Formalism of Stable Queue with Some Potential Applications of Fractal Dimension to Big Data Analytics.

- Mageed, I. A. (2024c). Fractal Dimension (Df) Theory of Ismail’s Entropy (IE) with Potential Df Applications to Structural Engineering. Journal of Intelligent Communication 2024, 3(2), 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mageed, I. A. (2024d). The Generalized Z-Entropy’s Fractal Dimension within the Context of the Rényian Formalism Applied to a Stable M/G/1 Queue and the Fractal Dimension’s Significance to Revolutionize Big Data Analytics. J Sen Net Data Comm 2024, 4(2), 01–11. [Google Scholar]

- Mageed, I. A. (2024e). Do You Speak The Mighty Triad?(Poetry, Mathematics and Music) Innovative Teaching of Mathematics. MDPI preprints.

- Mageed, I. A. , & Mohamed, M.(2023). Chromatin can speak Fractals: A review.

- Mageed, I.A. (2024f). Do You Speak The Mighty Triad?(Poetry, Mathematics and Music) Innovative Teaching of Mathematics. MDPI Preprints.

- Mageed, I.A. (2024g). The Mathematization of Puzzles or Puzzling Mathematics Innovative Teaching of Mathematics. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Mageed, I.A. (2024h). Let’s All Dance and Play Mathematics Innovative Teaching of Mathematics. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Mageed, I.A. (2024i). AI-Generated Abstract Expressionism Inspiring Creativity Through Ismail A Mageed's Internal Monologues in Poetic Form. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Mageed, I.A. (2024j). Let’s All Dance and Play Mathematics Innovative Teaching of Mathematics. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Mageed, I.A. (2024k). AI-Generated Abstract Expressionism Inspiring Creativity Through Ismail A Mageed's Internal Monologues in Poetic Form. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Mageed, I. A. (2024l). Fractal Dimension (Df) Theory of Ismail's entropy (IE) with Potential Df applications to Smart Cities. J Sen Net Data Comm 2024l, 4, 01–10. [Google Scholar]

- Mageed, I. A. (2024m). Entropic Advancement To Education. Int J Med Net, (2024; 2, 6, 01–10. [Google Scholar]

- Mageed, I. A. , & Nazir, A. R. (2024). AI-Generated Abstract Expressionism Inspiring Creativity through Ismail A Mageed's Internal Monologues in Poetic Form. Annals of Process Engineering and Management (2024, 1(1), 33–85. [Google Scholar]

- Mageed, I. A. (2025a). The Hidden Poetry & Music of Mathematics for Teaching Professionals: Inspiring Students through the Art of Mathematics: A Guide for Educators. Eliva Press. https://www.elivabooks.com/en/book/book-1450104825.

- Mageed, I.A. (2025b). The Hidden Dancing & Physical Education of Mathematics for Teaching Professionals. Eliva Press. https://www.elivabooks.com/en/book/book-7724827898.

- Mageed, I.A. (2025c). Does Infinity Exist? Crossroads Between Mathematics, Physics, and.

- Philosophy. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Mageed, I.A. (2025d). The Islamization of Mathematics: A Philosophical and Pedagogical Inquiry. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Mageed, I.A. (2025e). Phenomenal Fractal Geometric Techniques in Mathematics Education for Key Stage 2 Students: A New Paradigm for Teaching Multiplication Tables. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Mageed, I.A. (2025f). Re-Writing the History of Mechanics: From the Islamic Golden Age to the Newtonian Synthesis. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Mageed, I.A. (2025g). The Secret Wit in Teaching Mathematics: A Guide to Professionals. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Mageed, I.A. (2025h). The Hidden Mathematics to Promote Next- Generation Creative Writing Pedagogy for Professionals: The Algorithmic Muse. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Mageed, I.A. (2025i). Do You Speak The Phenomenal Koch snowflake Fractal? Open Problems and Prospects. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Mageed, I.A. (2025j). Navigating Meta-Universes of Melded Infinities: A Theoretical Exploration of the Mind's Ontological Power. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Mageed, I.A. (2025k). Surpassing Beyond Boundaries: Open Mathematical Challenges in AI-Driven Robot Control. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Mageed, I.A. (2025l). The Dawn of a New Fractal Scalpel: Navigating the Landscape of Next-Generation Surgery. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Mageed, I. A. (2025m). Fractals Across the Cosmos: From Microscopic Life to Galactic Structures. MDPI Preprints.

- Mageed, I. A. , & Li, H. (2025). The Golden Ticket: Searching the Impossible Fractal Geometrical Parallels to solve the Millennium, P vs. NP Open Problem. MDPI Preprints.

- Moore, A. W. (2018). The infinite (3rd ed.). Routledge.

- Parker, M. W. (2019). Gödel's Argument for Cantorian Cardinality. Noûs 2019, 53(2), 375–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peitgen, H. O. , Jürgens, H., Saupe, D., & Feigenbaum, M. J. (2004). Chaos and fractals: new frontiers of science Vol. 106, Springer–604.

- Poincaré, H. (2024). The logic of infinity, BEYOND BOOKS HUB.

- Ratcliffe, M. (2024). On losing certainty. Phenomenology and the cognitive sciences, 1–19.

- Rucker, R. V. (2019). Infinity and the mind: The science and philosophy of the infinite, Princeton University Press.

- Su, F. (2020). Mathematics for human flourishing, Yale University Press.

- Venegas Aravena, P. , & Cordaro, E. G. (2025). On the limits of knowledge and the evolution of the physical laws in non-Euclidean universes. PhilSci-Archive, 2025; 2, 1, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg, S. (2022). The first three minutes: a modern view of the origin of the universe. basic books.

- Xiang, W. , Li, Y. In , Ren, Y., Jiang, F., Xin, C., Gupta, V., ... & Liang, Y. (2023, October). Gödel: Unified large-scale resource management and scheduling at bytedance. In Proceedings of the 2023 ACM Symposium on Cloud Computing (pp. 308-323).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).