Submitted:

17 July 2025

Posted:

21 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

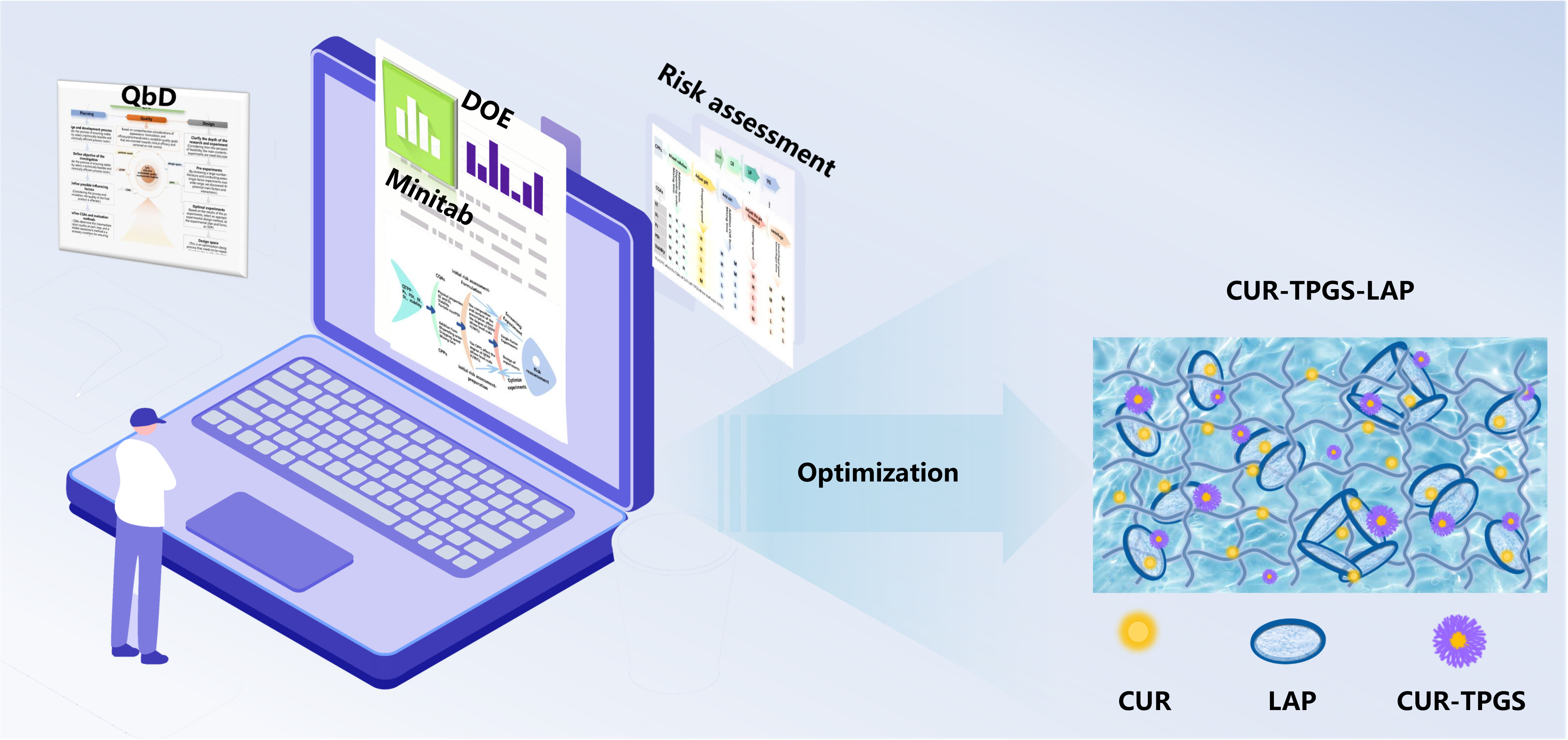

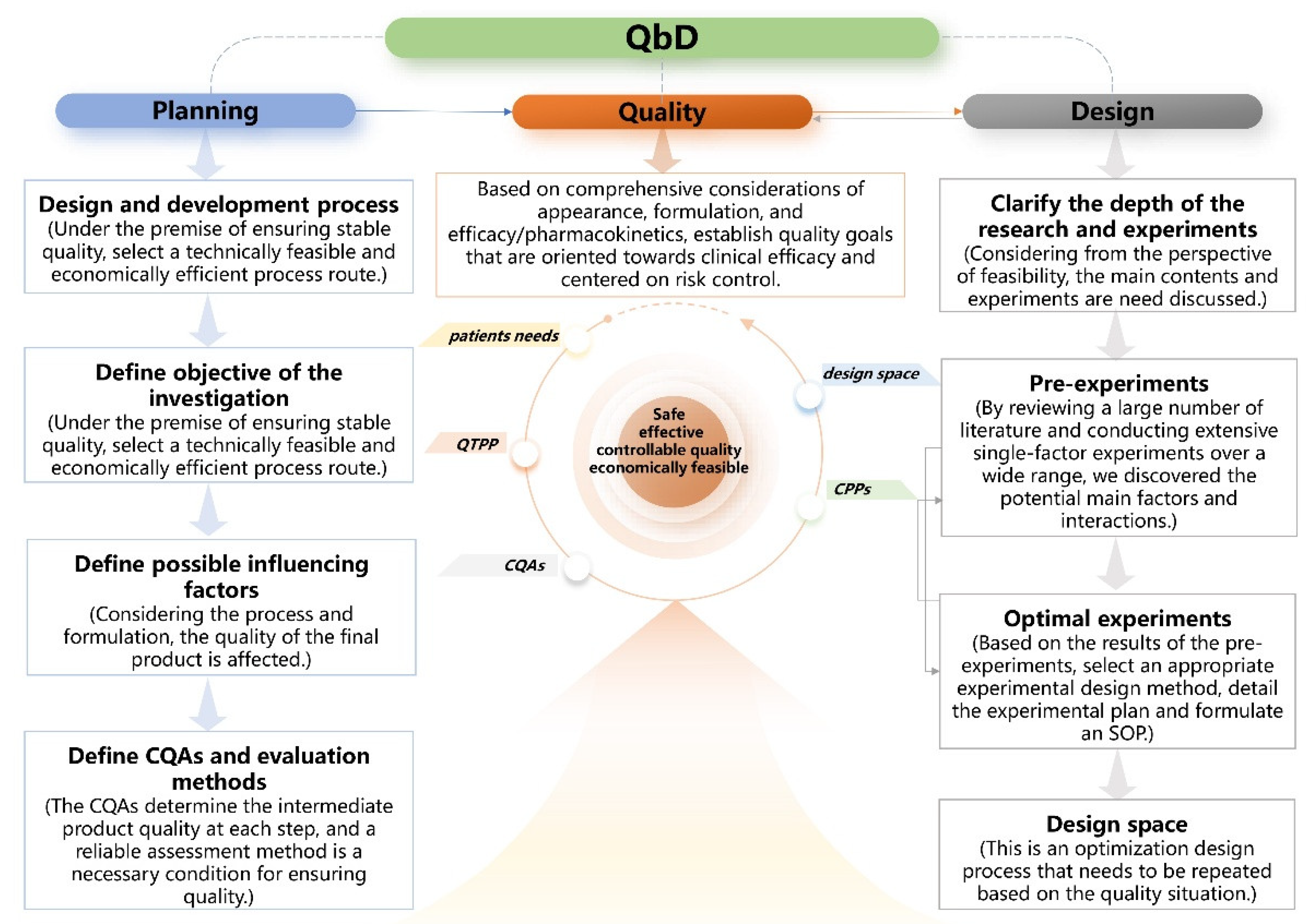

2.1. Development of the QbD Knowledge Space

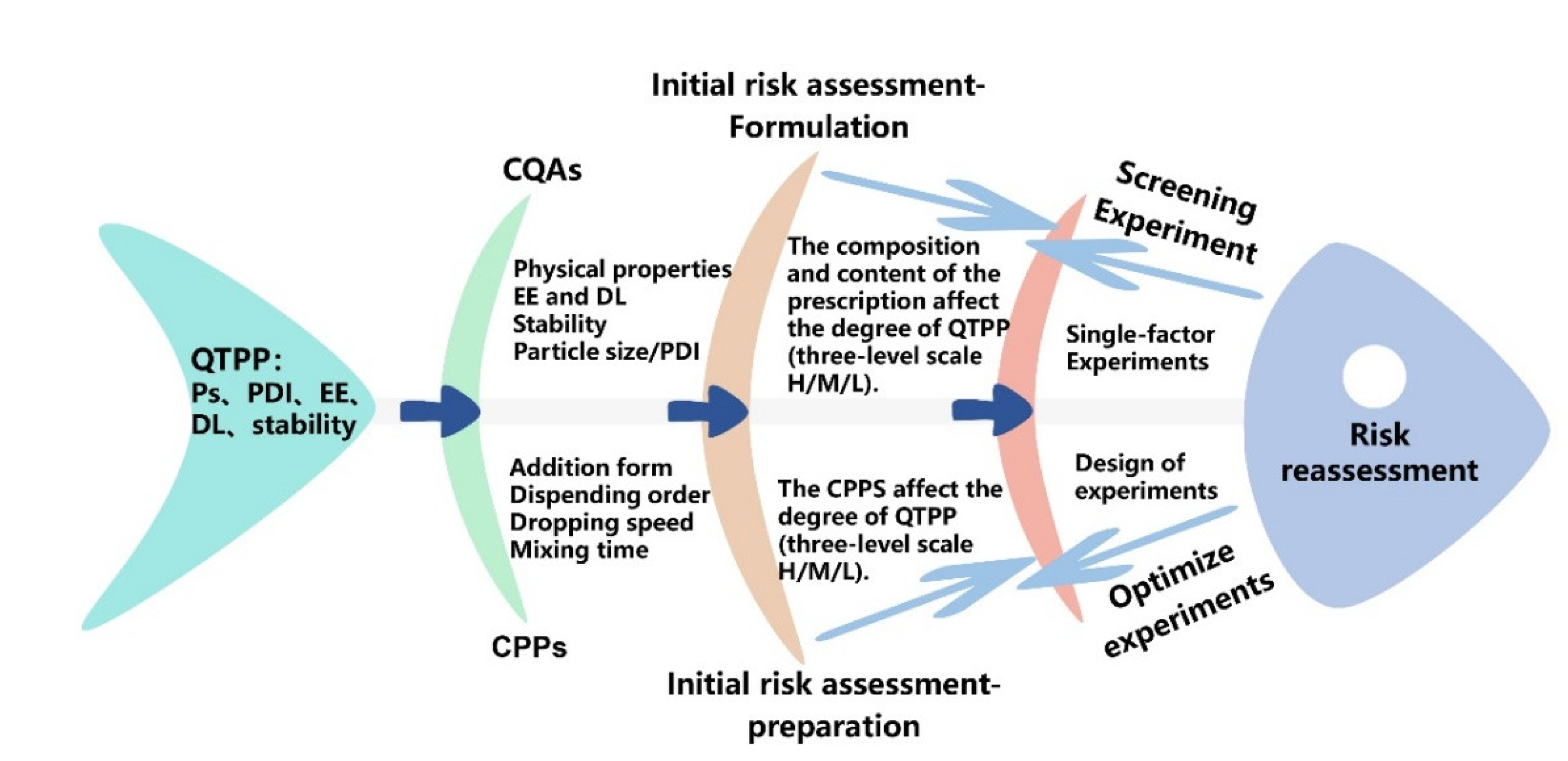

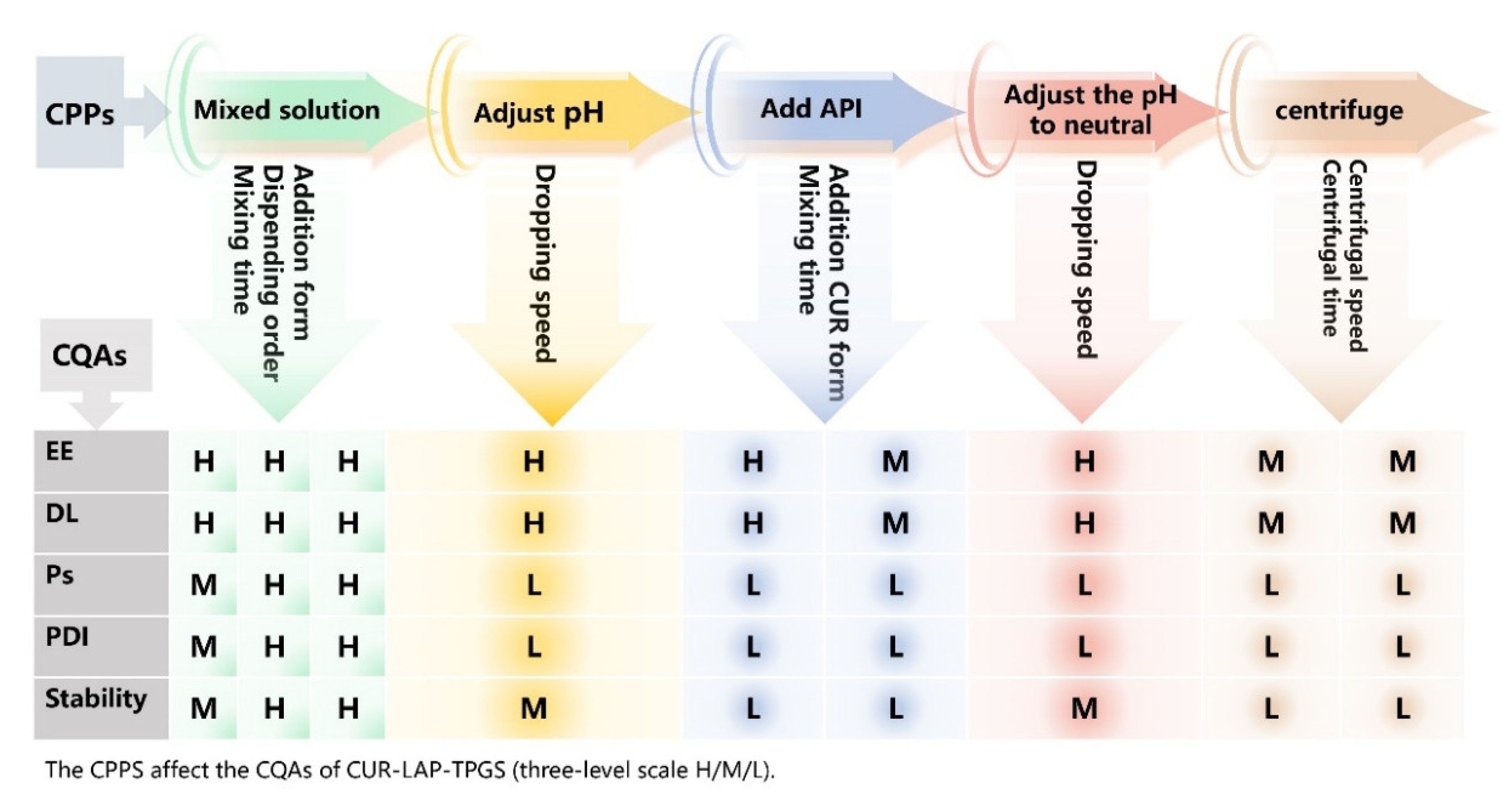

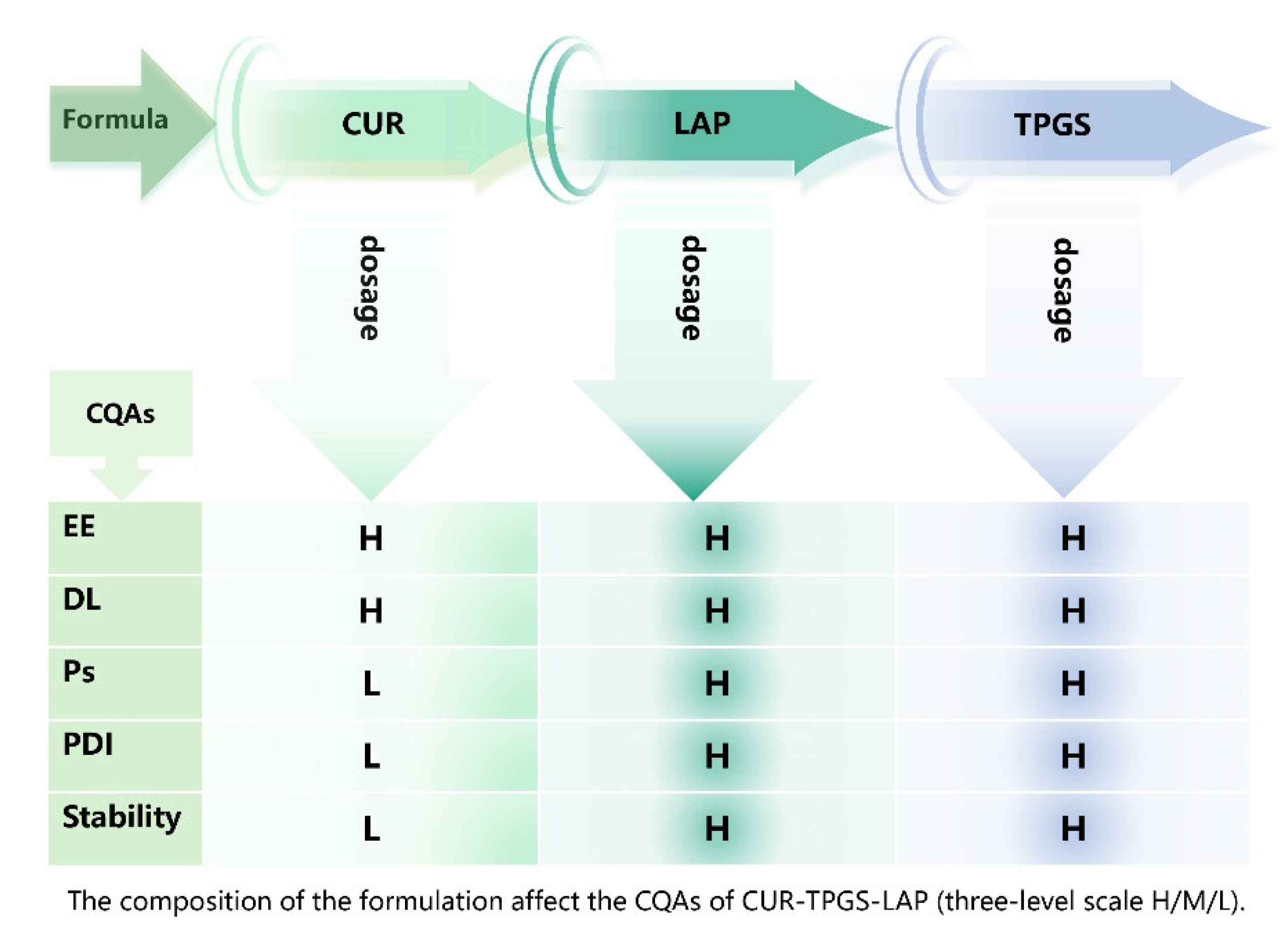

2.2. Initial Identification of QTPP, CQA, and CPP Elements

2.3. Pre-Experiment Results and Risk Re-Assessment

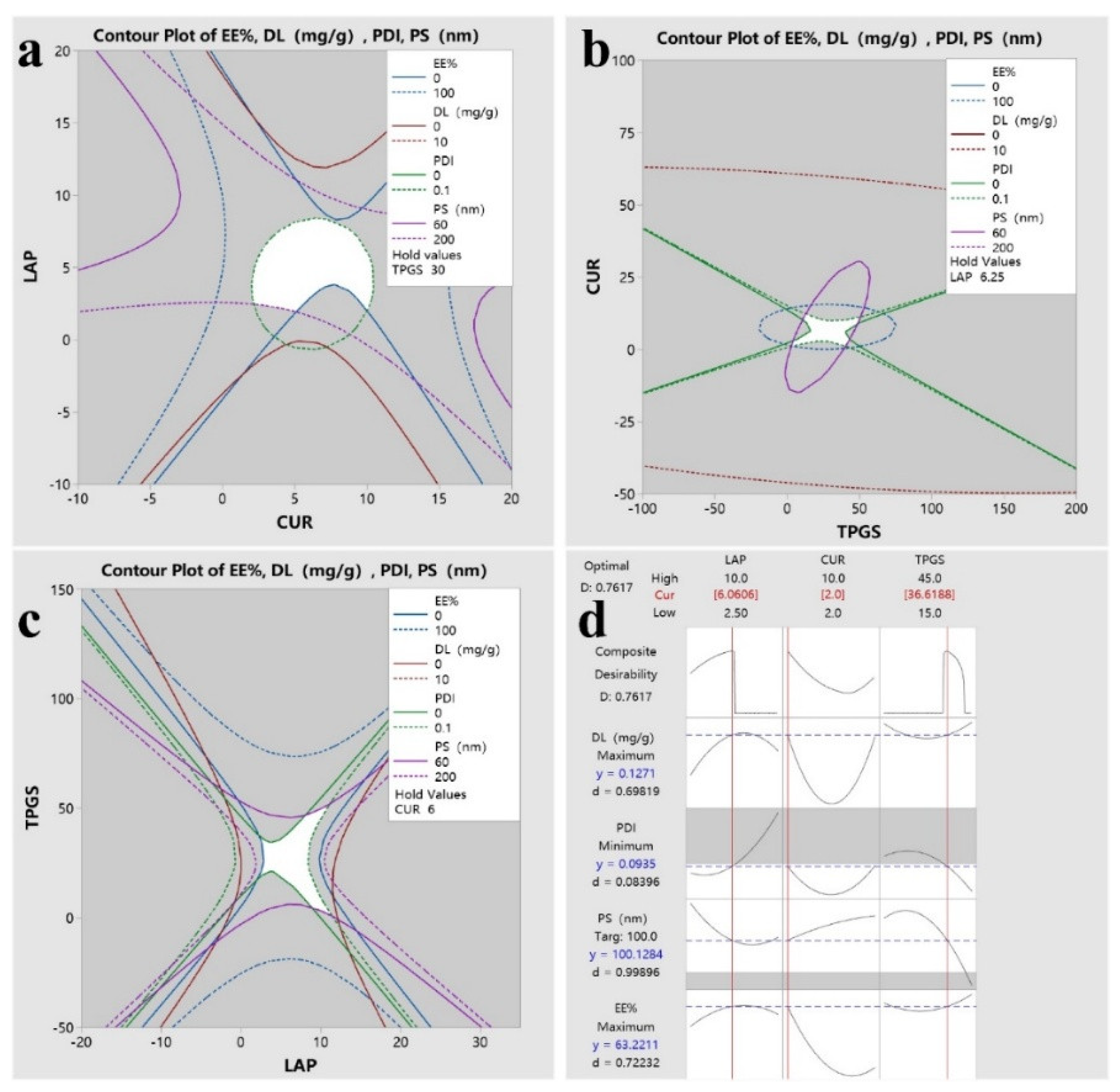

2.4. Results of DoE

2.5. The Characterization Results of the Optimal Prescription

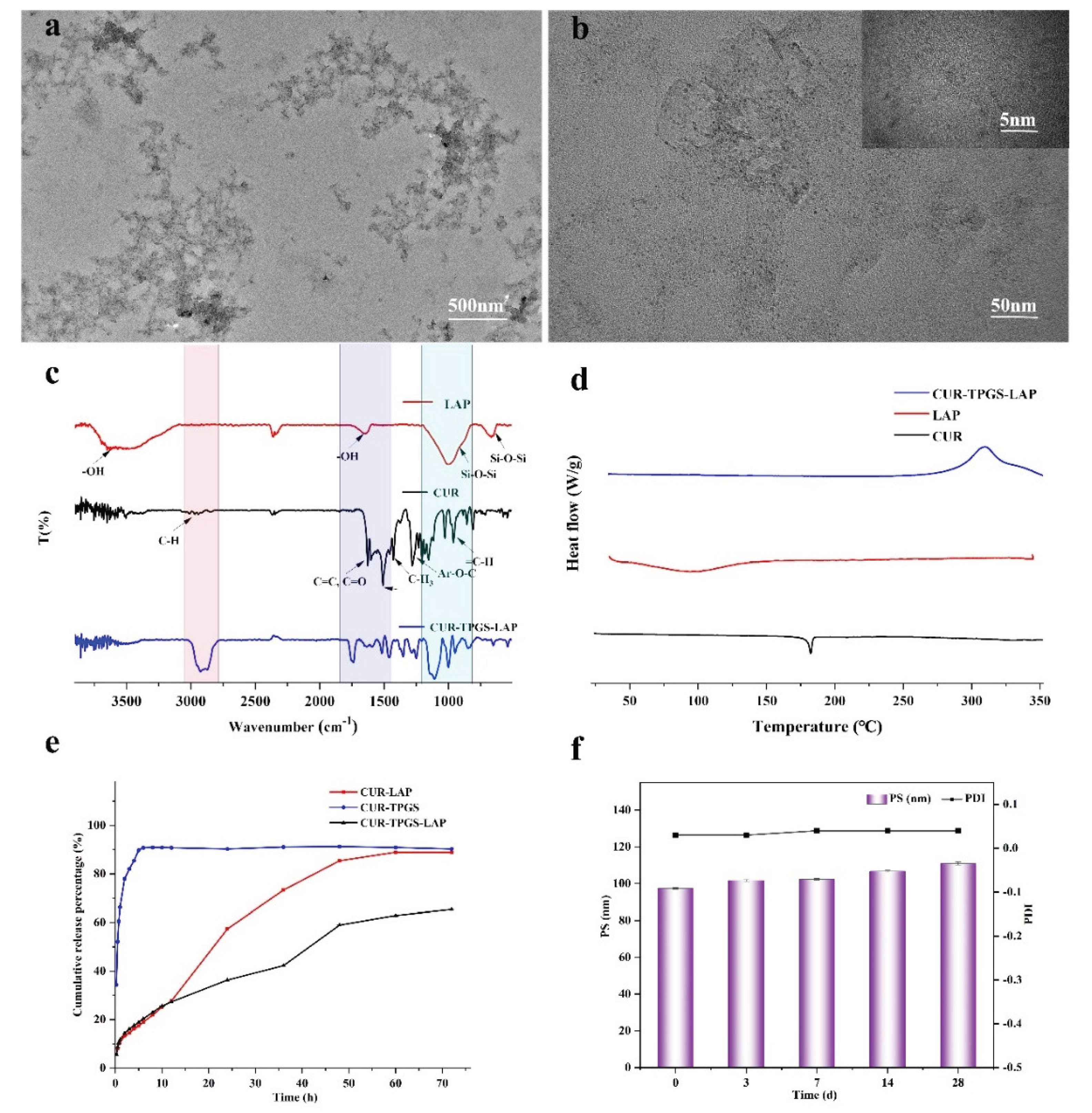

2.5.1. TEM

2.5.2. FTIR

2.5.3. DSC

2.5.4. In Vitro Drug Release

2.5.5. Stability

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Methods

4.2.1. Process of the QbD Design

4.2.2. Determine Elements of the QTPP

4.2.3. Determine Elements of the CQAs

4.2.4. Determine Elements of the CPPs

4.2.5. Risk Assessment of Formulation

4.2.6. Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| QbD | Quality by Design |

| QTPP | Quality Target Product Profile |

| CQAs | Critical Quality Attributes |

| CPPs | Critical process parameters |

| DOE | Design of Experiments |

| CUR | Curcumin |

| TPGS | Vitamin E polyethylene glycol succinate |

| LAP | Laponite |

| DL | Drug Loading |

| Ps | Particle size |

| EE | Encapsulation effi-ciency |

| PDI | Polydispersity Index |

| TEM | Transmission electron microscopy |

| FTIR | Fourier Transform infrared spectroscopy |

| DSC | Differential Scanning Calorimetry |

References

- Miao, L.; Kang, Y.; Zhang, X. F. , Nanotechnology for the theranostic opportunity of breast cancer lung metastasis: recent advancements and future challenges. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2024, 12, 1410017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unnikrishnan, G.; Joy, A.; Megha, M.; Kolanthai, E.; Senthilkumar, M. , Exploration of inorganic nanoparticles for revolutionary drug delivery applications: a critical review. Discov Nano 2023, 18(1), 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Zhao, J.; Lu, W.; Ma, Y.; Wang, X.; An, X.; Fan, Z. , The preparation of lactoferrin/magnesium silicate lithium injectable hydrogel and application in promoting wound healing. Int J Biol Macromol 2022, 220, 1501–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiaee, G.; Dimitrakakis, N.; Sharifzadeh, S.; Kim, H. J.; Avery, R. K.; Moghaddam, K. M.; Haghniaz, R.; Yalcintas, E. P.; Barros, N. R.; Karamikamkar, S.; Libanori, A.; Khademhosseini, A.; Khoshakhlagh, P. , Laponite-Based Nanomaterials for Drug Delivery. Adv Healthc Mater 2022, 11(7), e2102054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, P.; Kriplani, P. , Optimizing Transdermal Drug Delivery with Novasome Nanocarriers: A Quality by Design (QbD) Framework. Curr Drug Deliv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zagalo, D. M.; Sousa, J.; Simões, S. , Quality by design (QbD) approach in marketing authorization procedures of Non-Biological Complex Drugs: A critical evaluation. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 2022, 178, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, P. ; Muskan; Kriplani, P., Quality by design for Niosome-Based nanocarriers to improve transdermal drug delivery from lab to industry. Int J Pharm, 1247. [Google Scholar]

- Correia, A. C.; Moreira, J. N.; Sousa Lobo, J. M.; Silva, A. C. , Design of experiment (DoE) as a quality by design (QbD) tool to optimise formulations of lipid nanoparticles for nose-to-brain drug delivery. Expert Opin Drug Deliv 2023, 20(12), 1731–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cs, J.; Haider, M.; Rawas-Qalaji, M.; Sanpui, P. , Curcumin-loaded zein nanoparticles: A quality by design approach for enhanced drug delivery and cytotoxicity against cancer cells. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 2025, 245, 114319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamah, M.; Sipos, B.; Schelz, Z.; Zupkó, I.; Kiricsi, Á.; Szalenkó-Tőkés, Á.; Rovó, L.; Katona, G.; Balogh, G. T.; Csóka, I. , Development, in vitro and ex vivo characterization of lamotrigine-loaded bovine serum albumin nanoparticles using QbD approach. Drug Deliv 2025, 32(1), 2460693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bak, Y. W.; Woo, M. R.; Cho, H. J.; Kwon, T. K.; Im, H. T.; Cho, J. H.; Choi, H. G. , Advanced QbD-Based Process Optimization of Clopidogrel Tablets with Insights into Industrial Manufacturing Design. Pharmaceutics.

- Reddy, P. L.; Shanmugasundaram, S. , Optimizing Process Parameters for Controlled Drug Delivery: A Quality by Design (QbD) Approach in Naltrexone Microspheres. AAPS PharmSciTech 2024, 25(5), 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rampado, R.; Peer, D. , Design of experiments in the optimization of nanoparticle-based drug delivery systems. J Control Release 2023, 358, 398–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel Hamid, E. M.; Amer, A. M.; Mahmoud, A. K.; Mokbl, E. M.; Hassan, M. A.; Abdel-Monaim, M. O.; Amin, R. H.; Tharwat, K. M. , Box-Behnken design (BBD) for optimization and simulation of biolubricant production from biomass using aspen plus with techno-economic analysis. Sci Rep 2024, 14(1), 21769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M, M.; G, C.; A, B.-S.; CI, S.-D.; C, V.-I.; R, S.-E.; R, d. M. B.; F, L.; I, P.; R, N.; S, R. , Thixotropic Hydrogels Based on Laponite® and Cucurbituril for Delivery of Lipophilic Drug Molecules. ChemPlusChem 2024, 89(1), e202300370. [Google Scholar]

- Z, Z.; S, T.; SS, F. , Vitamin E TPGS as a molecular biomaterial for drug delivery. Biomaterials 2012, 33(19), 4889–906. [Google Scholar]

- SJ, L.; YI, J.; HK, P.; DH, K.; JS, O.; SG, L.; HC, L. , Enzyme-responsive doxorubicin release from dendrimer nanoparticles for anticancer drug delivery. International journal of nanomedicine 2015, 10, 5489–503. [Google Scholar]

- S, M.; J, Z.; B, L.; X, L.; T, W.; X, H.; P, C.; H, W.; Y, S.; G, P.; L, B. , A 3D bioprinted nano-laponite hydrogel construct promotes osteogenesis by activating PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Materials today. Bio 2022, 16, 100342. [Google Scholar]

- C, L.; F, J.; Z, X.; L, F.; Y, L.; S, W.; J, L.; XK, O. , Efficient Delivery of Curcumin by Alginate Oligosaccharide Coated Aminated Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles and In Vitro Anticancer Activity against Colon Cancer Cells. Pharmaceutics.

- ME, O.; AM, A.; NK, B.; AH, H.; R, G.; G, S. , Curcumin and Silver Doping Enhance the Spinnability and Antibacterial Activity of Melt-Electrospun Polybutylene Succinate Fibers. Nanomaterials (Basel, Switzerland).

- Prado, J. R.; Vyazovkin, S. , Activation energies of water vaporization from the bulk and from laponite, montmorillonite, and chitosan powders. Thermochimica Acta.

- Haghighi, E.; Abolmaali, S. S.; Dehshahri, A.; Mousavi Shaegh, S. A.; Azarpira, N.; Tamaddon, A. M. , Navigating the intricate in-vivo journey of lipid nanoparticles tailored for the targeted delivery of RNA therapeutics: a quality-by-design approach. J Nanobiotechnology 2024, 22(1), 710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J. H.; Yoon, T. H.; Ryu, S. W.; Kim, M. G.; Kim, G. H.; Oh, Y. J.; Lee, S. J.; Kwak, N. W.; Bang, K. H.; Kim, K. S. , Quality by Design (QbD)-Based Development of a Self-Nanoemulsifying Drug Delivery System for the Ocular Delivery of Flurbiprofen. Pharmaceutics.

- Liu, G.; An, D.; Li, J.; Deng, S. , Zein-based nanoparticles: Preparation, characterization, and pharmaceutical application. Front Pharmacol 2023, 14, 1120251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bushi, E.; Malaj, L.; Di Martino, P.; Mataj, G.; Myftari, B. , Formulation of semi solid dosage forms for topical application utilizing quality by design (QbD) approach. Drug Dev Ind Pharm 2025, 51(7), 670–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pielenhofer, J.; Meiser, S. L.; Gogoll, K.; Ciciliani, A. M.; Denny, M.; Klak, M.; Lang, B. M.; Staubach, P.; Grabbe, S.; Schild, H.; Radsak, M. P.; Spahn-Langguth, H.; Langguth, P. , Quality by Design (QbD) Approach for a Nanoparticulate Imiquimod Formulation as an Investigational Medicinal Product. Pharmaceutics.

- Koo, J.; Lim, C.; Oh, K. T. , Recent Advances in Intranasal Administration for Brain-Targeting Delivery: A Comprehensive Review of Lipid-Based Nanoparticles and Stimuli-Responsive Gel Formulations. Int J Nanomedicine 2024, 19, 1767–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurumukhi, V. C.; Bari, S. B. , Development of ritonavir-loaded nanostructured lipid carriers employing quality by design (QbD) as a tool: characterizations, permeability, and bioavailability studies. Drug Deliv Transl Res 2022, 12(7), 1753–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobó, D. G.; Németh, Z.; Sipos, B.; Cseh, M.; Pallagi, E.; Berkesi, D.; Kozma, G.; Kónya, Z.; Csóka, I. , Pharmaceutical Development and Design of Thermosensitive Liposomes Based on the QbD Approach. Molecules.

- Stealey, S. T.; Gaharwar, A. K.; Zustiak, S. P. , Laponite-Based Nanocomposite Hydrogels for Drug Delivery Applications. Pharmaceuticals (Basel).

- Pawar, N.; Peña-Figueroa, M.; Verde-Sesto, E.; Maestro, A.; Alvarez-Fernandez, A. , Exploring the Interaction of Lipid Bilayers with Curcumin-Laponite Nanoparticles: Implications for Drug Delivery and Therapeutic Applications. Small 2024, 20(52), e2406885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Singh, A.; Flora, S. J. S.; Shukla, R. , Box-Behnken Design Optimized TPGS Coated Bovine Serum Albumin Nanoparticles Loaded with Anastrozole. Curr Drug Deliv 2021, 18(8), 1136–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tejashree, W.; Swetha, K. L.; Aniruddha, R.; Ranendra Narayan, S.; Gautam, S. , Quality by design assisted optimization of temozolomide loaded PEGylated lyotropic liquid crystals: Investigating various formulation and process variables along with in-vitro characterization. Journal of Molecular Liquids 2022. [Google Scholar]

| Quality attributes | Is it a critical quality attribute? | Justification |

| Physical properties | No | Physical properties such as color, odor and appearance are not CQA, as these factors have no direct relationship with the efficacy of the formulation. |

| Encapsulation efficiency (EE)/ Drug Loading (DL) |

Yes | A higher encapsulation rate and drug loading capacity are crucial for achieving the maximum drug release and regulating the drug treatment concentration. Therefore, they are regarded as CQA. |

| Partical size (Ps/ Partical size distribution index (PDI) | Yes | Nanoparticles can more effectively pass through biological membranes within the appropriate nanoscale range, thereby improving solubility and absorption properties and enhancing the bioavailability of drugs. Therefore, they are regarded as CQA. |

| Stability | Yes | The stability of nanoparticles has a significant impact on the release of drugs and their efficacy. Therefore, it is regarded as a CQA |

| Ingredient | state | DL(mg/g) | EE(%) | Ps (nm) | PDI |

| CUR | solution | 0.01±0.00 | 12.87±0.04 | 2670.00±1565.22 | 0.45±0.06 |

| powder | 0.01±0.00 | 14.99±0.11 | 1220.33±319.28 | 0.40±0.05 | |

| TPGS | - | 0.004±0.00 | 15.03±0.04 | 339.67±11.73 | 0.35±0.10 |

| + | 0.01±0.00 | 22.83±0.04 | 204.00±6.16 | 0.26±0.02 | |

| LAP | solution | 0.01±0.00 | 16.96±0.07 | 138.33±1.25 | 0.21±0.01 |

| powder | 0.02±0.00 | 29.85±0.14 | 118.67±0.94 | 0.12±0.01 |

| Factors(mg) | Levels | ||

| -1 | 0 | 1 | |

| X1 | 2.5 | 6.25 | 10 |

| X2 | 2 | 6 | 10 |

| X3 | 15 | 30 | 45 |

| Run Order | factors | ||||||

| A | B | C | Y1 | Y2 | Y3 | Y4 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.14 | 13.57 | 128.0 | 0.041 |

| 2 | -1 | -1 | 0 | 0.06 | 30.75 | 223.0 | 0.023 |

| 3 | 1 | 0 | -1 | 0.03 | 4.23 | 206.0 | 0.059 |

| 4 | -1 | 0 | 1 | 0.06 | 10.58 | 48.4 | 0.032 |

| 5 | 0 | -1 | 1 | 0.17 | 85.90 | 46.6 | 0.028 |

| 6 | 1 | -1 | 0 | 0.09 | 44.37 | 121.0 | 0.336 |

| 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.06 | 9.97 | 169.0 | 0.035 |

| 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.06 | 9.92 | 141.0 | 0.043 |

| 9 | 0 | -1 | -1 | 0.15 | 75.56 | 107.0 | 0.151 |

| 10 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.05 | 8.88 | 103.0 | 0.045 |

| 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.06 | 9.92 | 143.0 | 0.025 |

| 12 | -1 | 0 | -1 | 0.05 | 8.94 | 167.0 | 0.037 |

| 13 | 0 | 1 | -1 | 0.05 | 5.16 | 76.5 | 0.03 |

| 14 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0.10 | 9.83 | 202.0 | 0.318 |

| 15 | -1 | 1 | 0 | 0.12 | 11.47 | 172.0 | 0.034 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).