1. Introduction

Microorganisms exist in nearly all natural environments. Their populations typically thrive in environments where favourable temperatures, moisture and nutrients support their development and reproduction [

1,

2]. In societies where faecal waste is inadequately managed and released into the environment untreated, pathogenic microorganisms can accumulate in high concentrations and are readily disseminated through various reservoirs [

3,

4]. Moreover, research has demonstrated that cockroaches act as carriers of pathogenic microorganisms. Their actions enable them to contaminate foods, utensils, kitchen areas, and other household environments as well as surfaces [

5]. Cockroach droppings may harbour bacteria that cause foodborne illnesses, as well as fungi and other harmful pathogens [

5,

6,

7].

Environmental surfaces constitute critical reservoirs for pathogen transmission. Pathogenic bacteria can persist on fomites for extended durations, with their survival influenced by environmental factors such as temperature, humidity, and the presence of other microorganisms. Faecal contamination from both human and animal sources is prevalent on household surfaces, including floors, in low-income communities, elevating the risk of human disease. Prior research has documented the presence of

Escherichia coli on various fomites, such as kitchen surfaces and cloths, toilet fixtures, door handles, and bathroom surfaces [

4,

8,

9]. These contaminated surfaces act as vectors for transmission, posing a significant health risk, particularly for foodborne illnesses.

Foodborne diseases constitute a significant and increasingly prevalent global public health challenge, encompassing a wide range of illnesses. While often manifesting as gastrointestinal symptoms, these diseases can also present with neurological, immunological, and other systemic effects [

10]. Ingestion of contaminated food can lead to multi-organ failure, resulting in significant morbidity and mortality [

11].

Observed globally and continuing to rise, the emergence and spread of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) are driven by factors such as the inappropriate use of antimicrobials, inadequate infection prevention and control measures, and weak regulation of antimicrobial use [

12,

13]. Frequently used household cleaning products may not effectively eliminate common household bacteria [

14,

15]. Furthermore, research indicates that sporadic or inconsistent use of disinfectants is ineffective in reducing bacterial counts in kitchen environments. In contrast, adherence to a prescribed, regular cleaning and disinfection protocol has been shown to be effective in bacterial reduction [

15].

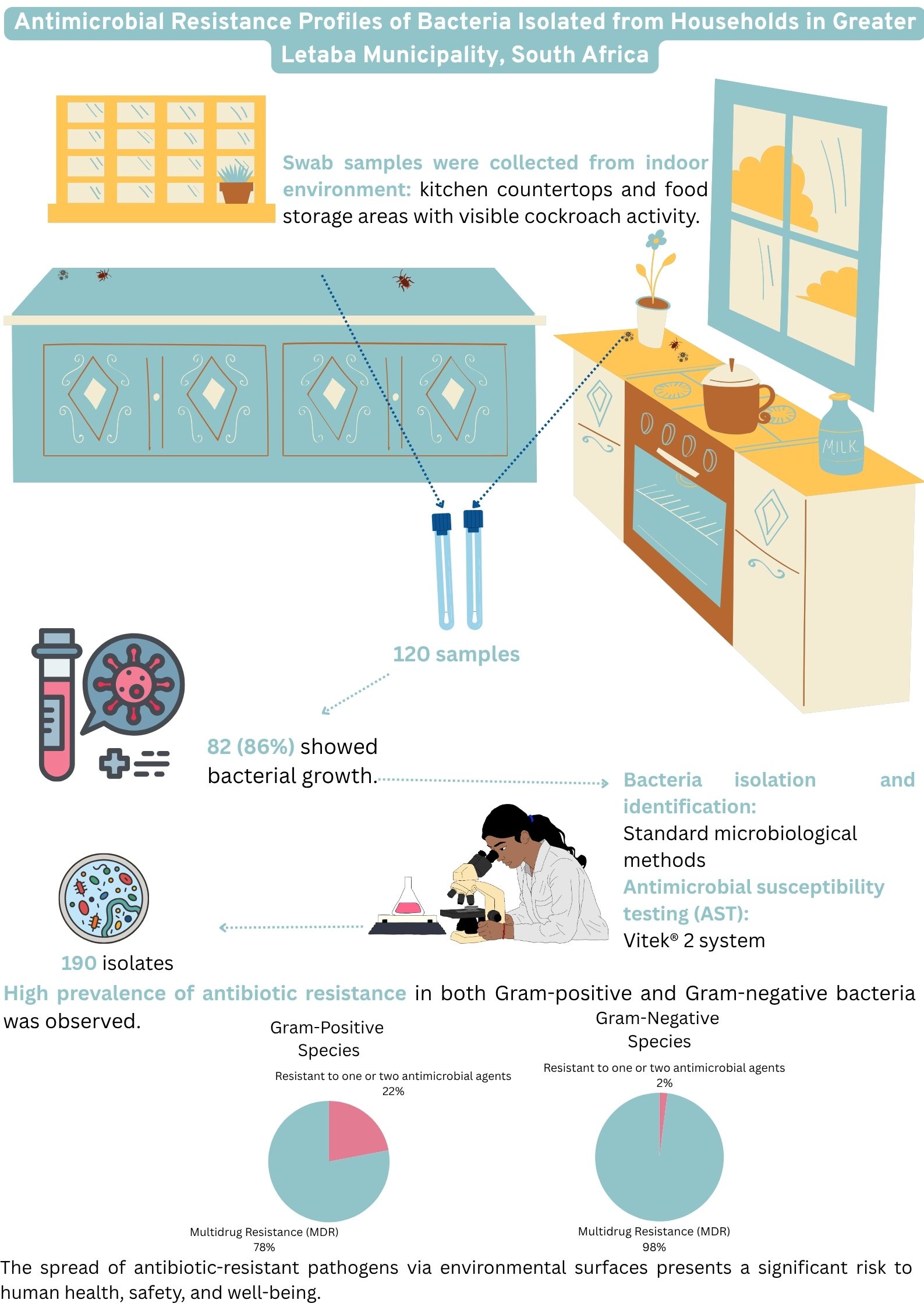

The aim was to determine microbial surface contamination and to determine antimicrobial resistance profile of bacteria isolated from the indoor surface where the presence of cockroaches was observed in households of Greater Letaba Municipality (GLM), South Africa.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Setting

A cross-sectional study was undertaken in March 2021 across six villages located in the rural areas of the Greater Letaba Municipality, Limpopo Province, South Africa.

2.2. Surface Sampling

Sterile, single-use, regular-sized traditional rayon swabs containing Amies Agar Gel (COPAN, LASEC SA) were utilized for sample collection. These swabs were employed to gather specimens from strategically selected sites, including kitchen countertops and food storage areas exhibiting evidence of cockroach activity. Indicators of such activity included the presence of live cockroaches, exoskeletons, fecal matter, eggs, egg cases, and proximity to cockroach traps. To ensure thorough sampling, each swab was rotated across the surface to collect material from all sides, covering an area of at least 10 x 10 cm. The swabs were assigned unique pseudonymous identification numbers. Following collection, the swabs were placed in transport media and maintained at a controlled temperature of 2–8 °C. The samples were then securely transported to the Water and Health Research Centre (WHRC) laboratory at the University of Johannesburg, where they were stored under appropriate conditions for subsequent bacterial analysis.

2.3. Microbial Testing

Standard microbiological methods were employed for the isolation and identification of bacterial species. Swab samples were inoculated onto seven types of selective agar media to facilitate the isolation of specific bacterial species: Mannitol Salt agar (for

Staphylococcus aureus), Slanetz and Bartley agar (for

Enterococcus faecium), Coliform Chromoselect agar for (

Escherichia coli), MacConkey agar for (

Enterobacter spp.), Campylobacter agar base (for

Acinetobacter baumannii), Pseudomonas Cetrimide agar (for

Pseudomonas aeruginosa), and Klebsiella Chromoselect agar (for

Klebsiella pneumoniae). The plates were placed in an incubator for 24-48 hours at 37°C. Presumptive colonies were sub-cultured on nutrient or Müller Hinton agar to obtain pure isolates. Isolates were further cultured on Müller Hinton agar and identified using the Vitek® 2 system. Prior to Vitek® 2 analysis, Gram staining was performed to confirm Gram-stain characteristics. Isolates were suspended in 0.45% saline solution to achieve a 0.5-0.63 McFarland standard, as per manufacturer's instructions, before inoculation onto Vitek® 2 identification cards [

16].

2.4. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) was performed using Vitek® 2 system cards (AST-N256 for Gram-negative bacilli and AST-P645 for Gram-positive cocci). AST results were analyzed by the Vitek® 2 system and subsequently evaluated in accordance with the clinical breakpoints established by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) and the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) [

17,

18].

2.5. Quality Assurance

All tests were rigorously repeated. Quality control measures were implemented throughout the Vitek® 2 system analysis of both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria. The AST cards incorporated internal growth control wells, serving as an essential component of the quality assurance process. These controls served to establish the reliability and validity of the test results. Furthermore, strict adherence to standardized protocols and manufacturer's recommendations was maintained to ensure the consistency and reproducibility of the research.

2.6. Data Analysis

Data entry and analysis were carried out with Microsoft Excel 2016. Cross-tabulations were utilized to calculate the percentage of isolates of each species exhibiting susceptibility, intermediate resistance, or resistance to the tested antimicrobial agents.

3. Results

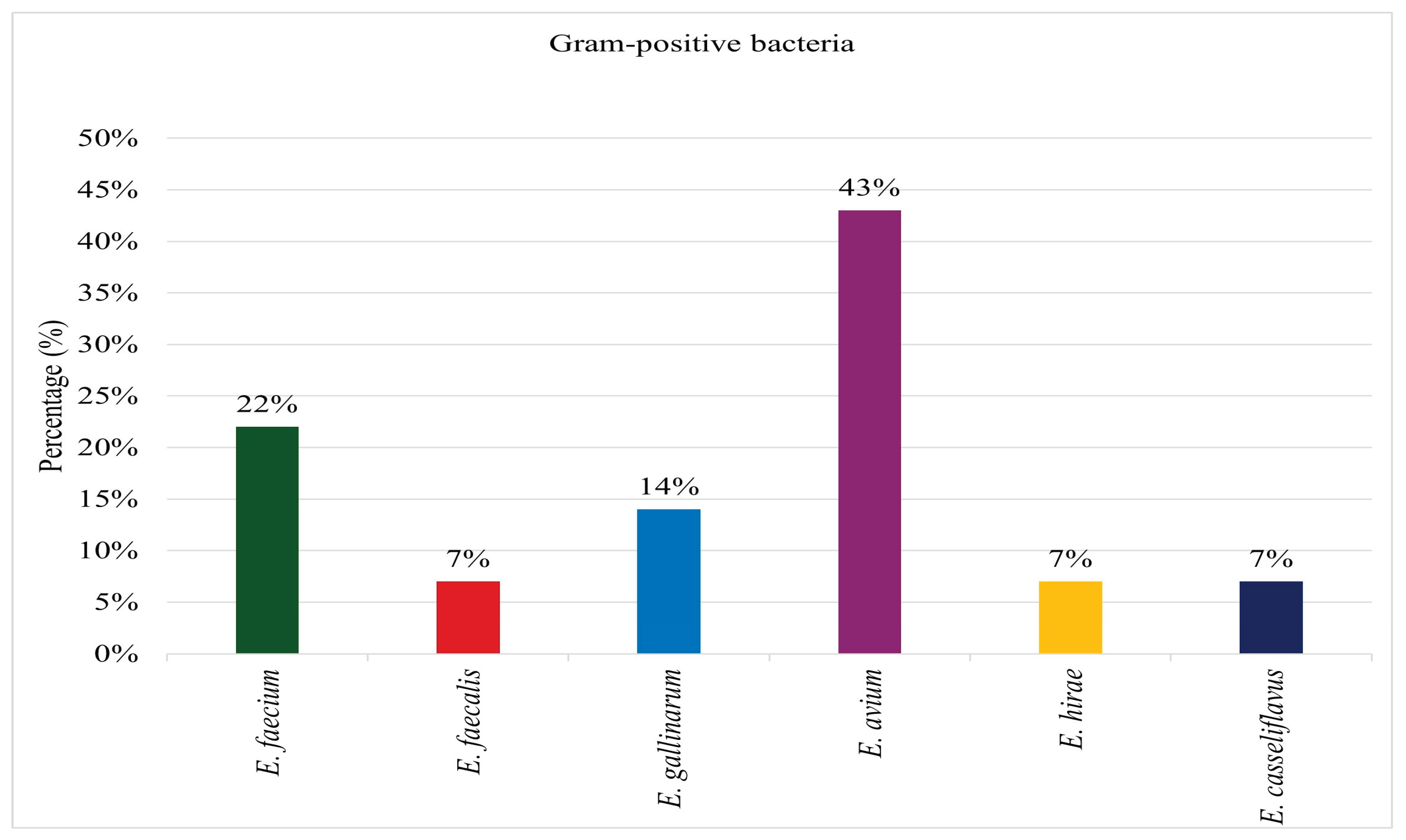

Hundred and twenty swab samples were collected, of which 82 (86%) exhibited bacterial growth. From these samples, 190 bacterial isolates were identified. Among the identified isolates, 176 (93%) were classified as Gram-negative species, while 14 (7%) were identified as Gram-positive species. All 14 (100%) Gram-positive isolates recovered from the sampled surfaces were identified as

Enterococcus species as depicted on

Figure 1. Among these, 3 isolates (22%) were classified as

Enterococcus faecium, 1 (7%) as

Enterococcus faecalis, 2 (14%) as

Enterococcus gallinarum, 6 (43%) as

Enterococcus avium, 1 (7%) as

Enterococcus hirae, and 1 (7%) as

Enterococcus casseliflavus.

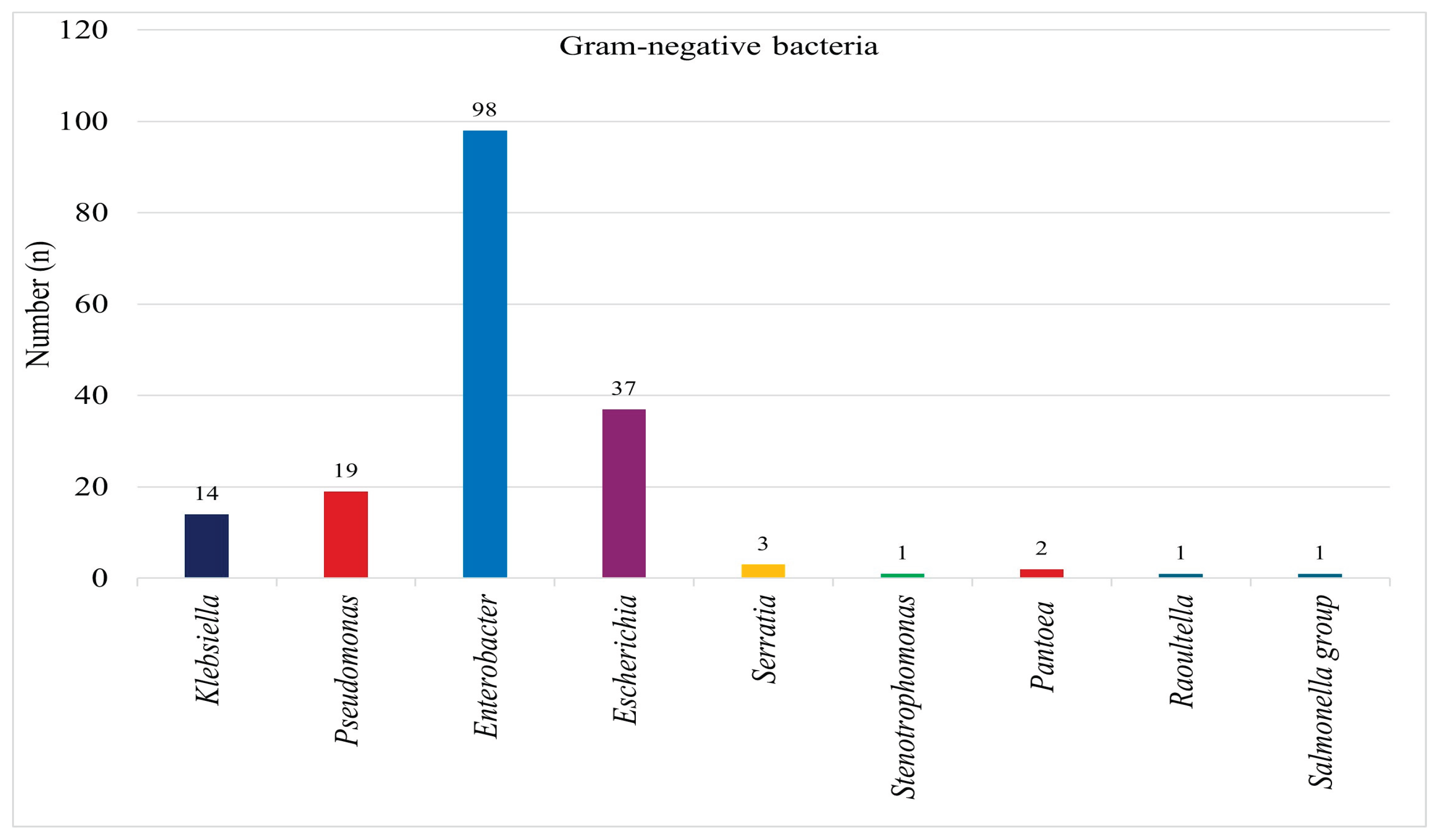

Among the 176 Gram-negative bacterial isolates, 14 (7%) were identified as

Klebsiella species, 19 (11%) as

Pseudomonas species, 98 (55%) as

Enterobacter species, 37 (21%) as

Escherichia species, 3 (2%) as

Serratia species, 1 (1%) as

Stenotrophomonas, 2 (1%) as

Pantoea, 1 (1%) as

Raoultella, and 1 (1%) as

Salmonella species as indicated on

Figure 2.

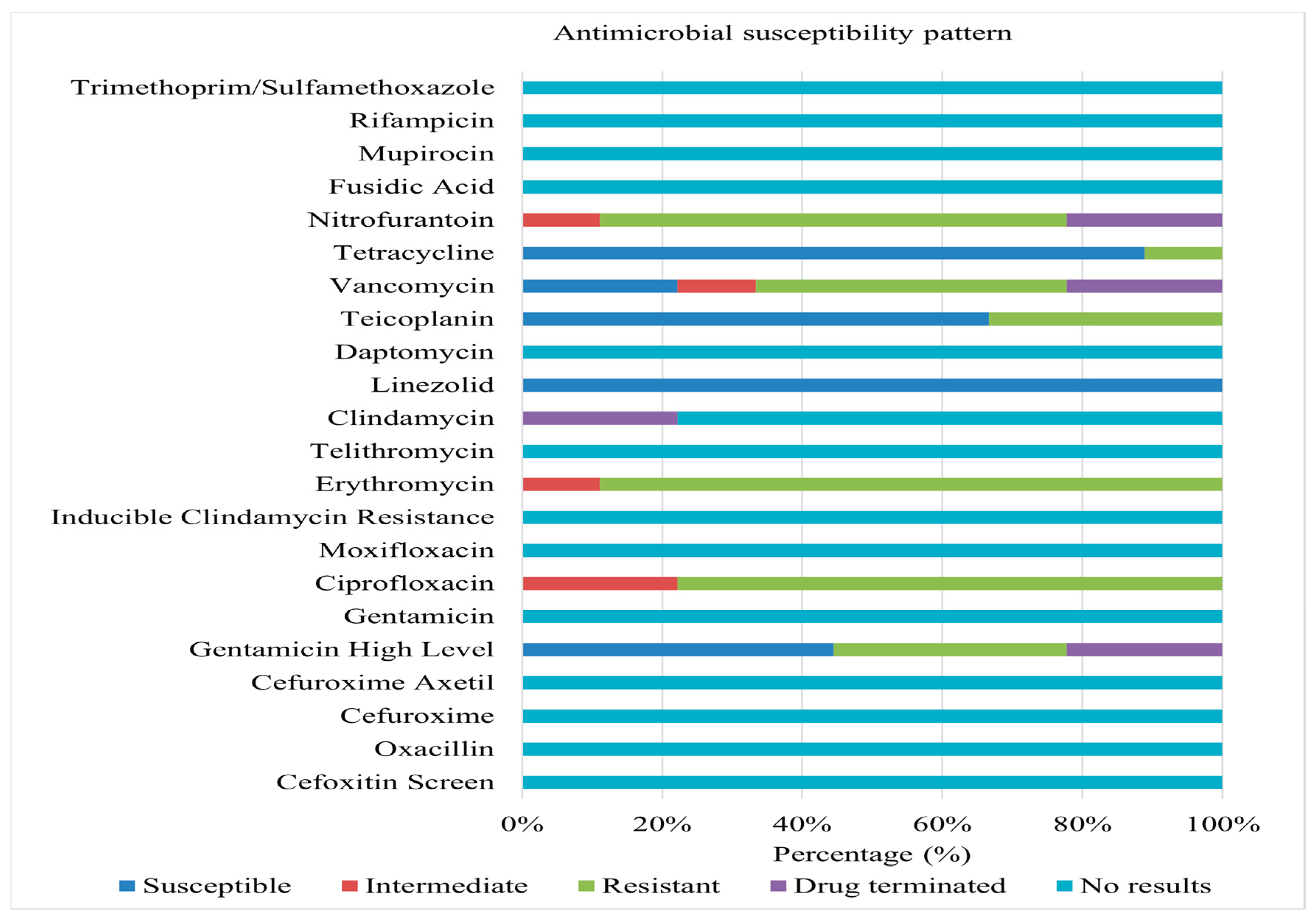

Nine Enterococcus spp. isolates were subjected to antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Among these, 7 (78%) exhibited MDR. The remaining 2 (22%) displayed non-susceptibility to one or two antimicrobials. Of the MDR isolates, 4 (57%) were identified as Enterococcus faecium, 2 (29%) as E. gallinarum, and 1 (14%) as E. hirae. Among the isolates non-susceptible to one or two antimicrobials, 1 (50%) were E. avium, and the other 1 (50%) were E. casseliflavus.

Figure 3 summarizes the antimicrobial susceptibility results of Gram-positive isolates from environmental surfaces. Hundred percent susceptibility was observed for linezolid and several other antibiotics.

In contrast, high levels of resistance were documented for ciprofloxacin, erythromycin, vancomycin, and nitrofurantoin, with some isolates demonstrating intermediate susceptibility. E. faecium isolates demonstrated complete resistance to erythromycin and nitrofurantoin, with high levels of resistance also observed against ciprofloxacin and vancomycin. All isolates exhibited susceptibility to linezolid and tetracycline, while a significant proportion displayed high-level susceptibility to gentamicin (synergistic effects) and teicoplanin. E. gallinarum isolates exhibited a pan-resistant phenotype, demonstrating 100% resistance to ciprofloxacin, teicoplanin, erythromycin, and vancomycin, along with resistance to three other antimicrobials. Only intermediate susceptibility was observed against nitrofurantoin. E. hirae isolates displayed a multidrug-resistant (MDR) pattern, exhibiting high-level resistance to gentamicin, erythromycin, teicoplanin, and nitrofurantoin. In contrast, 100% susceptibility was observed for linezolid and tetracycline. Enterococcus casseliflavus isolates exhibited resistance to ciprofloxacin, erythromycin, and teicoplanin, while remaining susceptible to linezolid and tetracycline. E. avium isolates exhibited non-susceptibility to fluoroquinolones and were ineffective against four antimicrobial agents. Conversely, 100% susceptibility was observed for linezolid, teicoplanin, and tetracycline.

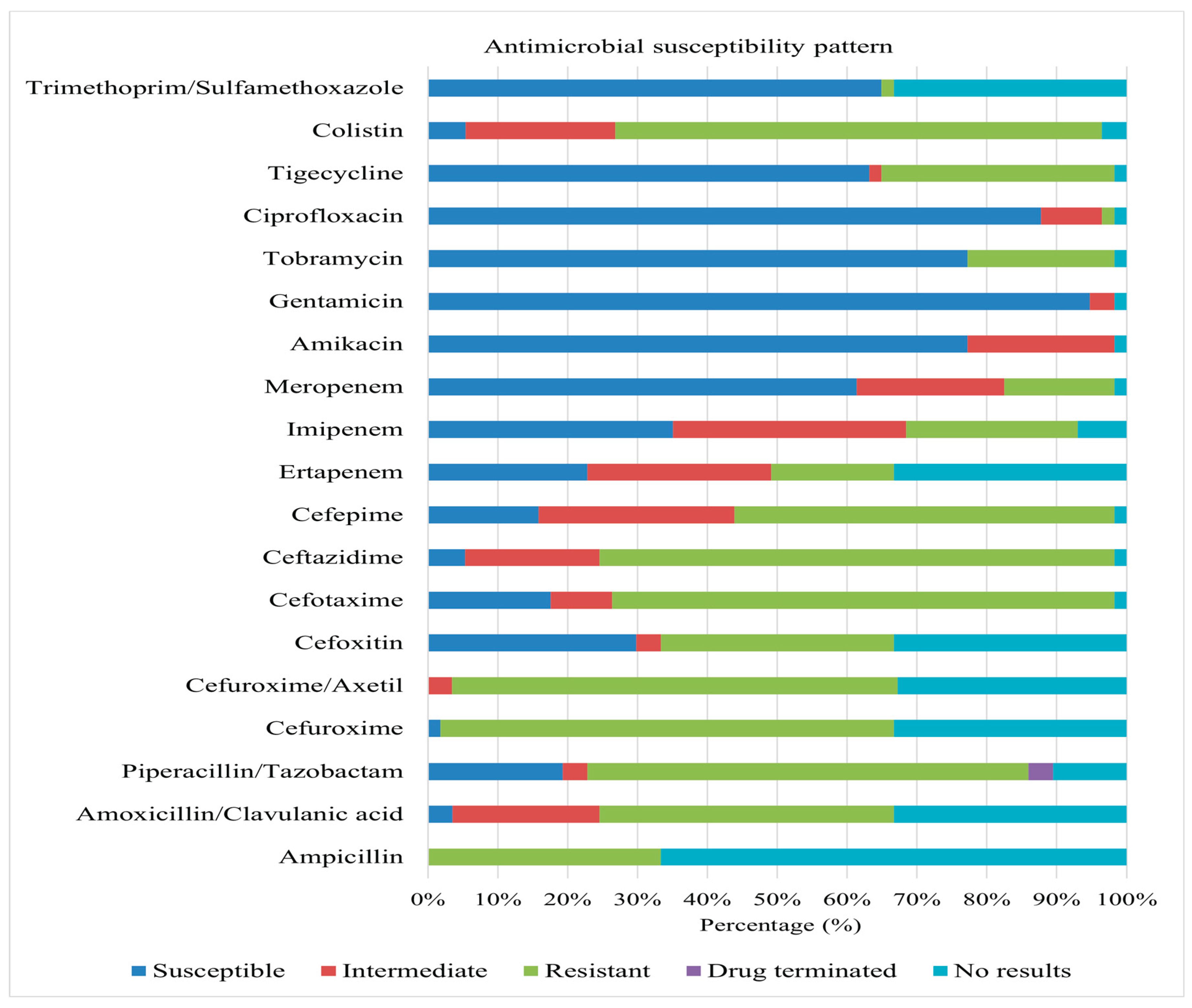

A total of 57 Gram-negative bacterial isolates were recovered and subjected to AST. The predominant species identified were Pseudomonas aeruginosa (32%), Klebsiella oxytoca (16%), and Enterobacter cloacae complex (11%). Other species encountered included Enterobacter aerogenes, Enterobacter cancerogenus, Serratia fonticola, Serratia marcescens, Klebsiella pneumoniae subsp. ozaenae, Klebsiella pneumoniae ssp. pneumoniae, Citrobacter amalonaticus, Raoultella planticola, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, Pantoea agglomerans, and Salmonella spp.

A high prevalence of MDR was observed, with 56 (98%) of isolates exhibiting non-susceptibility to one or more antimicrobial agents.

Figure 4 summarizes the antimicrobial susceptibility profiles of these isolates. Significant resistance levels were observed against a broad spectrum of antibiotics, including ampicillin, colistin, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, anti-pseudomonal penicillins (piperacillin/tazobactam), extended-spectrum cephalosporins (cefotaxime, ceftazidime, cefepime), and non-extended-spectrum cephalosporins (cefuroxime, cefuroxime-axetil).

Overall, high levels of susceptibility were observed for aminoglycosides (amikacin, gentamicin, and tobramycin), meropenem, tigecycline, ciprofloxacin, and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole across multiple species. Conversely, significant resistance was observed against various antimicrobial classes, including carbapenems, cephalosporins, and colistin. E. aerogenes demonstrated complete resistance to colistin, imipenem, non-extended spectrum cephalosporins, cefoxitin, ceftazidime, and piperacillin/tazobactam. E. cancerogenus showed complete resistance to carbapenems, cefuroxime, cefuroxime-axetil, cefoxitin, piperacillin/tazobactam, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, and colistin. S. fonticola demonstrated complete resistance to carbapenems, extended and non-extended spectrum cephalosporins, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, and colistin.

C. amalonaticus displayed complete resistance to non-extended spectrum cephalosporins, colistin, piperacillin/tazobactam, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, and imipenem. S. marcescens displayed non-susceptibility to colistin, ceftazidime, cefotaxime, cefuroxime, cefuroxime-axetil, and amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, with substantial non-susceptibility to tobramycin and cefepime. K. oxytoca demonstrated complete (100%) non-susceptibility to ampicillin and non-extended spectrum cephalosporins. Klebsiella pneumoniae subsp. ozaenae demonstrated complete resistance to non-extended spectrum cephalosporins, ampicillin, and colistin. K. pneumoniae ssp. pneumoniae exhibited total resistance to non-extended spectrum cephalosporins, ampicillin, and colistin. R. planticola is completely resistant to colistin, imipenem, and ampicillin. P. aeruginosa displayed 100% resistance to extended spectrum cephalosporins, tigecycline, and piperacillin/tazobactam. P. agglomerans is entirely non-susceptible to non-extended spectrum cephalosporins, with notable non-susceptibility to ceftazidime and cefotaxime. Salmonella spp. exhibited 100% resistance to tigecycline, meropenem, ertapenem, cefoxitin, ampicillin, extended spectrum cephalosporins, piperacillin/tazobactam, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, and non-extended spectrum cephalosporins. S. maltophilia demonstrated complete resistance to trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole.

4. Discussion

This study observed a higher prevalence of microbial contamination (86%) on indoor surfaces compared to findings in previous research. For instance, Othman [

19] reported contamination with pathogenic microorganisms in 84% of kitchens sampled, with swabs collected from items such as kitchen towels, gas stove knobs, refrigerator handles, water taps, and sponges. Similarly, Oxford et al. [

15] found that 28% of surfaces and items examined exhibited moderate to heavy bacterial growth, with kitchen cloths (86%) and taps (52%) demonstrating the highest levels of contamination. Adiga et al. [

20] further supported these findings, with 64% of 50 samples collected from 10 kitchens harbouring pathogenic microorganisms. These results collectively emphasize the significant microbial burden associated with inanimate objects within kitchen environments.

This study aligns with previous work by Jeong et al. [

21], Oxford et al. [

15], Othman [

19] and others, reported bacterial contamination on indoor surfaces and within kitchen environments. However, Gram-negative bacteria exhibited a higher prevalence in the present investigation.

Enterobacter spp. was frequently isolated, followed by

Klebsiella spp.,

Pseudomonas spp.,

Escherichia spp., and

Serratia spp. In contrast,

Enterococcus spp. dominated the Gram-positive isolates, with

E. avium being the most prevalent.

Previous studies have also identified a range of bacterial contaminants. Othman [

19] reported the presence of

E. coli, Klebsiella spp.

, Salmonella spp

., S. aureus, Shigella spp.,

S. epidermidis, and

Micrococcus spp. Adiga et al. [

20] isolated

K. pneumoniae, Proteus species, S. epidermidis, E. coli, S. aureus, and

Enterobacter spp. Mehta and Akhlak [

22] identified

S. aureus, S. pneumoniae, Shigella spp.,

E. coli, and

K. pneumoniae on household surfaces. Jeong et al. [

21] further demonstrated the presence of

Pseudomonas,

Pantoea,

Bacillus,

Firmicutes,

Staphylococcus, and

Streptococcus species on contaminated surfaces, illustrating the diversity of bacterial contaminants. Similarly, a study by Flores et al. [

23] identified bacterial associated with

Firmicutes,

Bacteroidetes,

Proteobacteria, and

Actinobacteria. These findings collectively highlight the persistent and diverse bacterial contamination of indoor environments, particularly in kitchen areas.

Both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria are known to persist on dry, inanimate surfaces under humid and adverse conditions for extended periods, thereby acting as reservoirs for transmission [

24]. This persistence poses a public health concern as these surfaces can serve as contact points, potentially causing infections in individuals exposed to them. An analysis of nine bacterial isolates obtained from this current study revealed that 78% of the isolates demonstrated resistance to three or more antimicrobial agents, meeting the definition MDR. The remaining 22% exhibited non-susceptibility to only one or two of the antimicrobial agents tested. MDR isolates were predominantly

E. faecium (57%), followed by

E. gallinarum (29%) and

E. hirae (14%). In contrast, isolates showing non-susceptibility to one or two antimicrobial agents were evenly distributed and identified as

E. avium as well as

E. casseliflavus.

The study highlighted erythromycin resistance as the most common (89% of isolates), followed by resistance to ciprofloxacin (77%), nitrofurantoin (67%), vancomycin (67%), teicoplanin (33%), and high-level gentamicin (33%). These findings underscore the concerning prevalence of antimicrobial resistance among Enterococcus species isolated from kitchen environments. Such resistance poses a significant public health risk, especially in kitchens where food is prepared and consumed, as it increases the potential for cross-contamination and foodborne illness in rural households. Poor hygiene practices may contribute to the presence of MDR Enterococcus in kitchens. Insufficient handwashing and inadequate cleaning and disinfection of surfaces can facilitate the spread of pathogenic bacteria.

Additionally, the studies suggested that pests, particularly cockroaches, could play a role in disseminating antimicrobial-resistant bacteria [

5,

6,

7]. Samples were collected from areas where cockroach activity was evident. It is likely that cockroaches that come into contact with the contaminated surfaces may also acquire these pathogens and transfer them to other fomites, including food and water, exacerbating the risk of disease transmission.

The data further revealed that Gram-positive bacteria predominantly exhibited resistance to erythromycin, ciprofloxacin, nitrofurantoin, vancomycin, teicoplanin, and gentamicin. Among Gram-negative bacteria, MDR was widespread. Resistance to key antimicrobial agents, including ampicillin, colistin, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, anti-pseudomonal penicillins, extended-spectrum cephalosporins, and non-extended-spectrum cephalosporins, was particularly pronounced. These findings align with previous research documenting the persistence and dissemination of MDR bacteria in household environments, emphasizing the need for improved hygiene practices and pest control measures to mitigate the risks associated with antimicrobial resistance [

15,

21,

23]. Enhanced public health strategies are essential to address this growing concern and reduce the potential for foodborne illnesses and the spread of resistant pathogens.

5. Conclusions

Cross-contamination represents a significant contributor to foodborne illness outbreaks, and household surfaces serve as potential reservoirs for various pathogens. This study demonstrated a high prevalence of antibiotic resistance among both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria isolated from household floors. The dissemination of antibiotic-resistant pathogens through environmental surfaces poses a serious threat to human health, safety, and well-being. These findings highlight the critical importance of stringent hygiene practices and proactive public health measures to prevent disease transmission. Moreover, the data provide valuable insights for informing disease prevention strategies, promoting hygiene awareness, and guiding policy development to establish healthier and safer living environments for communities worldwide.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.L.M., T.G.B. and N.N.; methodology, M.L.M., T.G.B. and N.N.; software, M.L.M. and T.G.B.; validation M.L.M.; formal analysis, M.L.M., T.G.B. and N.N.; investigation, M.L.M.; resources, T.G.B.; data curation, M.L.M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.L.M.; writing—review and editing, M.L.M., T.G.B. and N.N.; visualization, M.L.M., T.G.B. and N.N.; supervision, T.G.B. and N.N.; project administration, M.L.M.; funding acquisition, T.G.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded by Water and Health Research Centre, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Johannesburg.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by University of Johannesburg Faculty of Health Sciences (FHS) Research Ethics Committee (REC-866-2020, 7 December 2020), the Higher Degree Committee (HCD-01-105-2020, 7 December 2020), and the Greater Letaba Municipality (10 February 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contributions of all the data collectors and households from Ward 2 of Bolobedu, Greater Letaba Municipality and the laboratory assistants from the Water and Health Research Centre at the University of Johannesburg.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GLM |

Greater Letaba Municipality |

| AST |

Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing |

| MDR |

Multidrug Resistance |

| WHRC |

Water and Health Research Centre |

| CLSI |

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute |

| EUCAST |

European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing |

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

References

- David Greenwood; Richard C. B. Slack; JOhn F. Peutherer Medical Microbiology 16th Edition; Elsevier Science Limited, 2002; ISBN 978-81-312-0100-8.

- Otu-Bassey, I.B.; Ewaoche, I.S.; Okon, B.F.; Ibor, U.A. Microbial Contamination of Household Refrigerators in Calabar Metropolis-Nigeria. American Journal of Epidemiology and Infectious Disease 2017.

- Julian, T.R. Environmental Transmission of Diarrheal Pathogens in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Environ. Sci.: Processes Impacts 2016, 18, 944–955. [CrossRef]

- Exum, N.; Kosek, M.; Davis, M.; Schwab, K. Surface Sampling Collection and Culture Methods for Escherichia Coli in Household Environments with High Fecal Contamination. IJERPH 2017, 14, 947. [CrossRef]

- Moges, F.; Eshetie, S.; Endris, M.; Huruy, K.; Muluye, D.; Feleke, T.; G/Silassie, F.; Ayalew, G.; Nagappan, R. Cockroaches as a Source of High Bacterial Pathogens with Multidrug Resistant Strains in Gondar Town, Ethiopia. BioMed Research International 2016, 2016, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Czajka, E.; Pancer, K.; Kochman, M.; Gliniewicz, A.; Sawicka, B.; Rabczenko, D.; Stypułkowska-Misiurewicz, H. [Characteristics of bacteria isolated from body surface of German cockroaches caught in hospitals]. Przegl Epidemiol 2003, 57, 655–662.

- Pai, H.-H.; Chen, W.-C.; Peng, C.-F. Isolation of Bacteria with Antibiotic Resistance from Household Cockroaches (Periplaneta Americana and Blattella Germanica). Acta Trop 2005, 93, 259–265. [CrossRef]

- Zambrano, L.D.; Levy, K.; Menezes, N.P.; Freeman, M.C. Human Diarrhea Infections Associated with Domestic Animal Husbandry: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Transactions of The Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 2014, 108, 313–325. [CrossRef]

- Harris, A.R.; Pickering, A.J.; Harris, M.; Doza, S.; Islam, M.S.; Unicomb, L.; Luby, S.; Davis, J.; Boehm, A.B. Ruminants Contribute Fecal Contamination to the Urban Household Environment in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 4642–4649. [CrossRef]

- Agi, V.N.; Aleru, C.P.; Uweh, E.J. Bacterial Contamination of Some Domestic and Laboratory Refrigerators in Port Harcourt Metropolis. In Proceedings of the European Journal of Health Sciences; February 28, 2021; Vol. 6, pp. 16–34.

-

WHO Estimates of the Global Burden of Foodborne Diseases: Foodborne Disease Burden Epidemiology Reference Group 2007-2015; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2015; ISBN 978-92-4-156516-5.

- Moghnieh, R.; Araj, G.F.; Awad, L.; Daoud, Z.; Mokhbat, J.E.; Jisr, T.; Abdallah, D.; Azar, N.; Irani-Hakimeh, N.; Balkis, M.M.; et al. A Compilation of Antimicrobial Susceptibility Data from a Network of 13 Lebanese Hospitals Reflecting the National Situation during 2015-2016. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2019, 8, 41. [CrossRef]

- Atalay, Y.A.; Mengistie, E.; Tolcha, A.; Birhan, B.; Asmare, G.; Gebeyehu, N.A.; Gelaw, K.A. Indoor Air Bacterial Load and Antibiotic Susceptibility Pattern of Isolates at Adare General Hospital in Hawassa, Ethiopia. Front Public Health 2023, 11, 1194850. [CrossRef]

- Erdogrul, O.; Erbilir, F. Microorganisms in Kitchen Sponges. Internet Journal of Food Safety 2005, 6, 17–25.

- Oxford, J.; Berezin, E.N.; Courvalin, P.; Dwyer, D.; Exner, M.; Jana, L.A.; Kaku, M.; Lee, C.; Letlape, K.; Low, D.E.; et al. An International Survey of Bacterial Contamination and Householders’ Knowledge, Attitudes and Perceptions of Hygiene. Journal of Infection Prevention 2013, 14, 132–138. [CrossRef]

- Pincus, D.H. Microbial Identification Using the bioMérieux VITEK® 2 System’. Encyclopedia of Rapid Microbiological Methods 2010.

- CLSI M100 31st Edition Released | News | CLSI Available online: https://clsi.org/about/news/clsi-publishes-m100-performance-standards-for-antimicrobial-susceptibility-testing-31st-edition/ (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- Eucast: The 13.0 Versions of Breakpoints, Dosing and QC (2023) Published. Available online: https://www.eucast.org/eucast_news/news_singleview?tx_ttnews%5Btt_news%5D=518&cHash=2509b0db92646dffba041406dcc9f20c (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- Othman, A.S. Isolation and Microbiological Identification of Bacterial Contaminants in Food and Household Surfaces: How to Deal Safely. Egyptian Pharmaceutical Journal 2015, 14, 50. [CrossRef]

- Adiga, I.; Shobha, K.; Mustaffa, M.; Bismi, N.; Yusof, N.; Ibrahim, N.; Nor, N. Bacterial Contamination in the Kitchen: Could It Be Pathogenic?; April 16 2012.

- Jeong, J.S.; Choi, J.K.; Jeong, I.S.; Paek, K.R.; In, H.-K.; Park, K.D. A nationwide survey on the hand washing behavior and awareness. J Prev Med Public Health 2007, 40, 197. [CrossRef]

- Mehta, J.; Akhlak, M. Isolation and Identification of Bacterial Contamination from Commonly Used Household Surfaces. JETIR 2018, 5, 697–705.

- Flores, G.E.; Bates, S.T.; Caporaso, J.G.; Lauber, C.L.; Leff, J.W.; Knight, R.; Fierer, N. Diversity, Distribution and Sources of Bacteria in Residential Kitchens. Environmental Microbiology 2013, 15, 588–596. [CrossRef]

- Birru, M.; Mengistu, M.; Siraj, M.; Aklilu, A.; Boru, K.; Woldemariam, M.; Biresaw, G.; Seid, M.; Manilal, A. Magnitude, Diversity, and Antibiograms of Bacteria Isolated from Patient-Care Equipment and Inanimate Objects of Selected Wards in Arba Minch General Hospital, Southern Ethiopia. Res Rep Trop Med 2021, 12, 39–49. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).