1. Introduction

The emergence of the Metaverse as a virtual extension of our physical world has transformed various sectors, with healthcare experiencing particularly significant impacts [

1,

2,

3]. Virtual healthcare environments now offer unprecedented opportunities for remote patient monitoring, telemedicine, and collaborative medical services [

4]. For elderly populations - a demographic expected to comprise more than 22% of the global population by 2050 [

5,

6] - these technologies address critical challenges in accessibility and continuous monitoring of healthcare [

7]. According to recent statistics, nearly 40% of seniors in the United States live alone, creating an urgent need for innovative safety monitoring solutions [

8].

Virtual healthcare environments rely on avatars and digital twins (DT), virtual representations of patients and physical objects, to facilitate remote monitoring and interactions [

9]. These digital entities serve as the interface between healthcare providers and patients, allowing real-time assessment of health status, adherence to medications, and safety conditions [

10]. In the context of elder care, DTs can detect falls, monitor vital signs, and alert caregivers to potential emergencies without requiring physical presence [

11].

However, the growing sophistication of Deepfake technologies poses significant security threats to these virtual healthcare systems [

12]. Malicious actors can potentially create fraudulent avatars or manipulate existing ones to misrepresent patient conditions, leading to misdiagnosis, delayed interventions, or inappropriate medical decisions [

13]. The data manipulation vulnerability is particularly concerning in elder care, where patients may have limited technological ability to identify or report suspicious activities [

14]. Traditional authentication methods, including passwords, biometrics, and token-based approaches, are increasingly inadequate against advanced Deepfake attacks [

15]. These conventional security measures operate entirely within the digital domain, lacking a verifiable connection to the physical world they claim to represent [

16]. The digital-to-physical disconnect creates a fundamental security vulnerability in which digital representations can be manipulated without corresponding changes in physical reality [

17].

To address this critical digital-to-physical gap, we propose SAVE (Securing Avatars in Virtual Environments), a novel framework that leverages physical environmental fingerprints to authenticate avatars and detect Deepfake attacks in virtual healthcare settings. Our approach utilizes electric network frequency (ENF) signals, which are subtle fluctuations in the frequency of the power grid that are location-specific and time-variant, to establish a verifiable link between virtual avatars and their physical counterparts [

18]. This paper is an extension of our work previously reported in a conference paper [

19].

ENF signals have previously shown effectiveness in digital forensics [

20], media authentication [

21], and geolocation verification [

22]. These signals possess several advantageous properties for security applications: ubiquitous in environments with electrical infrastructure, difficult to predict or replicate without physical presence, and naturally synchronized between geographical regions connected to the same power grid [

23]. By embedding ENF fingerprints into the data used to update avatars, SAVE creates an authentication mechanism that is inherently tied to physical reality.

The primary contributions of this paper include:

Novel Authentication Framework: We introduce SAVE, a comprehensive framework for securing avatars in virtual healthcare environments using environmental fingerprinting based on ENF signals.

Implementation in Elder Care: We demonstrate the practical application of SAVE in a lightweight Metaverse-based nursing home designed to monitor elderly people living alone, showcasing its relevance to critical healthcare applications.

Security Evaluation: We evaluate SAVE against multiple attack scenarios, including unauthorized device access, device ID spoofing, and replay attacks, providing empirical evidence of its effectiveness in detecting Deepfake attempts.

Usability Considerations: We address the unique requirements of elder care applications, ensuring that security enhancements do not introduce additional complexity for elderly users or healthcare providers.

Although previous research has explored various aspects of Metaverse security [

24], avatar authentication [

25], and DT healthcare applications [

26], SAVE represents the first comprehensive framework that leverages physical environmental fingerprints specifically to secure virtual healthcare representations.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews related work in Metaverse security, ENF-based authentication, and DTs in healthcare.

Section 3 details the design and architecture of the SAVE framework.

Section 4 describes our implementation in a virtual elder care environment.

Section 5 presents our experimental evaluation and results.

Section 6 discusses implications, limitations, and future directions, and

Section 7 concludes the paper.

2. Background and Related Works

The increasing adoption of Metaverse in e-Healthcare has introduced novel challenges related to the security and authenticity of virtual entities. This section provides a review of current research in Metaverse security, ENF-based authentication, and DT applications in healthcare, establishing the foundation for our SAVE framework.

2.1. Metaverse Security and Authentication

The Metaverse represents a convergence of physical and virtual realities, creating immersive environments in which users interact through digital avatars [

2,

27]. While offering unprecedented opportunities for remote collaboration and services, these virtual worlds introduce complex security challenges. A comprehensive survey of Metaverse security identifies authentication of virtual entities as a critical concern, particularly as the boundaries between physical and digital identities become increasingly blurred [

12].

Current

authentication schemes for Metaverse environments mainly rely on traditional approaches adapted to virtual contexts. A three-factor authentication scheme was proposed based on elliptic curve cryptography (ECC) that improves security while maintaining lower computational overhead compared to alternative approaches [

15]. However, the ECC method remains vulnerable to sophisticated side-channel analysis attacks. A chameleon signature-based framework has been suggested that connects users’ real identities with their virtual avatars [

17]. Although innovative, the chameleon approach necessitates periodic verification checks, which increase computational demands.

Biometric authentication has emerged as a promising direction for securing avatars. Fuzzy logic is combined with biometric data to create unique signatures for authentication [

14], which captures hand tremor patterns using convolutional neural networks (CNN) to generate distinctive biometric identifiers. Although CNNs possess these advances, current authentication methods remain vulnerable to AI-driven deepfake attacks, which can synthesize biometric data or mimic authorized behavior patterns [

4].

2.2. ENF Signals in Security Applications

ENF signals refer to slight fluctuations in power grid frequency around nominal values (60 Hz in North America, 50 Hz in Europe and Asia) [

18]. These fluctuations result from the continuous balance of power supply and demand throughout the electrical grid and create unique, time-variant signatures that are consistent between locations connected to the same power grid [

23]. ENF signals have gained attention in security applications due to their distinctive properties. As demonstrated by earlier researchers [

18], ENF signals are:

Ubiquitous in environments with electrical infrastructure;

Difficult to predict or artificially replicate;

Temporally unique, creating time-specific signatures; and

Regionally consistent across connected power grids.

ENF signals recorded simultaneously from locations 180 miles apart show nearly identical fluctuation patterns, highlighting their potential for authentication applications [

23]. Researchers have applied ENF signals in various security domains, such as digital multimedia forensics [

20], where ENF signals verify the time and location of recordings, and smart grid infrastructure security [

28], where ENF signals are adopted to authenticate the sensing data to secure the critical infrastructure. ENF signals have also been used to detect malicious frame injection attacks in surveillance systems, demonstrating high accuracy in the identification of manipulated video content [

21]. Furthermore, researchers explored ENF signals as entropy generators in distributed systems, establishing their utility for security applications beyond forensics [

22].

Despite these advantages, ENF-based authentication faces limitations, particularly in environments without reliable access to power grid signals. This constraint requires complementary approaches when implementing security in diverse settings [

29].

2.3. Digital Twins in Healthcare

DTs, virtual representations of physical entities that mirror their characteristics, behaviors, and states, have emerged as powerful tools in healthcare applications [

9]. By integrating data from multiple sources, including remote and wearable sensors, these virtual models enable real-time monitoring, simulation, and analysis of patients’ conditions [

10]. The application of DTs in healthcare spans numerous domains. The fundamental aspects of DTs are described for simulation, highlighting their potential for personalized medicine [

9]. A review of recent developments in DT in healthcare identified chronic disease monitoring as a primary application area [

10]. For elderly care specifically, DTs have been shown to enable precision and personalized dementia care through continuous monitoring and predictive analytics [

11].

Specialized applications include a semi-active DT model for the evaluation of carotid stenosis [

26], which combines computational mechanics with computer vision to assess severity based on head vibrations. Similarly, DT models are developed to assess intracranial aneurysms, allowing the monitoring of potentially dangerous conditions through virtual simulations [

30].

For elderly patients, DTs offer particular benefits in the management of chronic conditions that require continuous monitoring [

31]. By creating virtual representations based on physiological data from wearable devices, healthcare platforms can provide timely analysis and alerts to potential health problems [

11,

32]. A virtual biometric capability is especially valuable for seniors living alone, who represent a significant proportion of the elderly population in developed countries [

8].

2.4. Elder Care Monitoring Systems

The growing elderly population presents unique healthcare challenges, particularly for those living independently. According to the US Census Bureau [

8], nearly 40% of seniors live alone, creating significant demand for remote monitoring solutions. These individuals face increased risks of accidents, delayed medical interventions, and complications from chronic diseases [

33].

Current monitoring approaches range from simple emergency alert systems to sophisticated IoT-based platforms. Sun and Chen [

32] developed a lightweight human action recognition system for real-time elderly monitoring, focusing on fall detection and activity classification. Their approach demonstrates the feasibility of continuous monitoring while respecting privacy concerns. Virtual environments extend these capabilities by creating immersive spaces where healthcare providers can visualize and interact with patient digital representations. Considering technical and resource constraints for a comprehensive full-scale mirror of the physical space, researchers introduced the Microverse concept, a task-oriented edge-scale Metaverse specifically designed for applications such as elderly monitoring [

25]. The Microverse framework provides a virtual environment where avatars represent seniors’ real-time status based on sensor data, enabling healthcare providers to remotely monitor multiple patients.

Although these technologies offer remarkable capabilities for elder care, they also introduce significant security vulnerabilities. The authenticity of virtual representations is critical, particularly in healthcare settings, where decisions affecting physical well-being rely on virtual information [

12]. Traditional authentication methods may be insufficient against sophisticated attacks, highlighting the need for novel approaches that bridge physical and virtual security [

16].

2.5. Research Gap

Despite significant advances in Metaverse security, ENF-based authentication, and healthcare DTs, critical gaps remain in the security of virtual healthcare environments against deepfake attacks. Existing authentication frameworks focus primarily on user identity verification rather than ensuring the ongoing authenticity of avatar updates. Furthermore, while ENF signals have demonstrated effectiveness in forensic applications, their potential to secure real-time healthcare monitoring in virtual environments remains unexplored. Our SAVE framework addresses these gaps by:

Extending ENF-based authentication to virtual healthcare environments;

Creating a continuous validation mechanism for avatar updates;

Implementing a multi-layered security approach specifically designed for elderly care monitoring; and

Providing robust protection against sophisticated deepfake attacks targeting healthcare DTs.

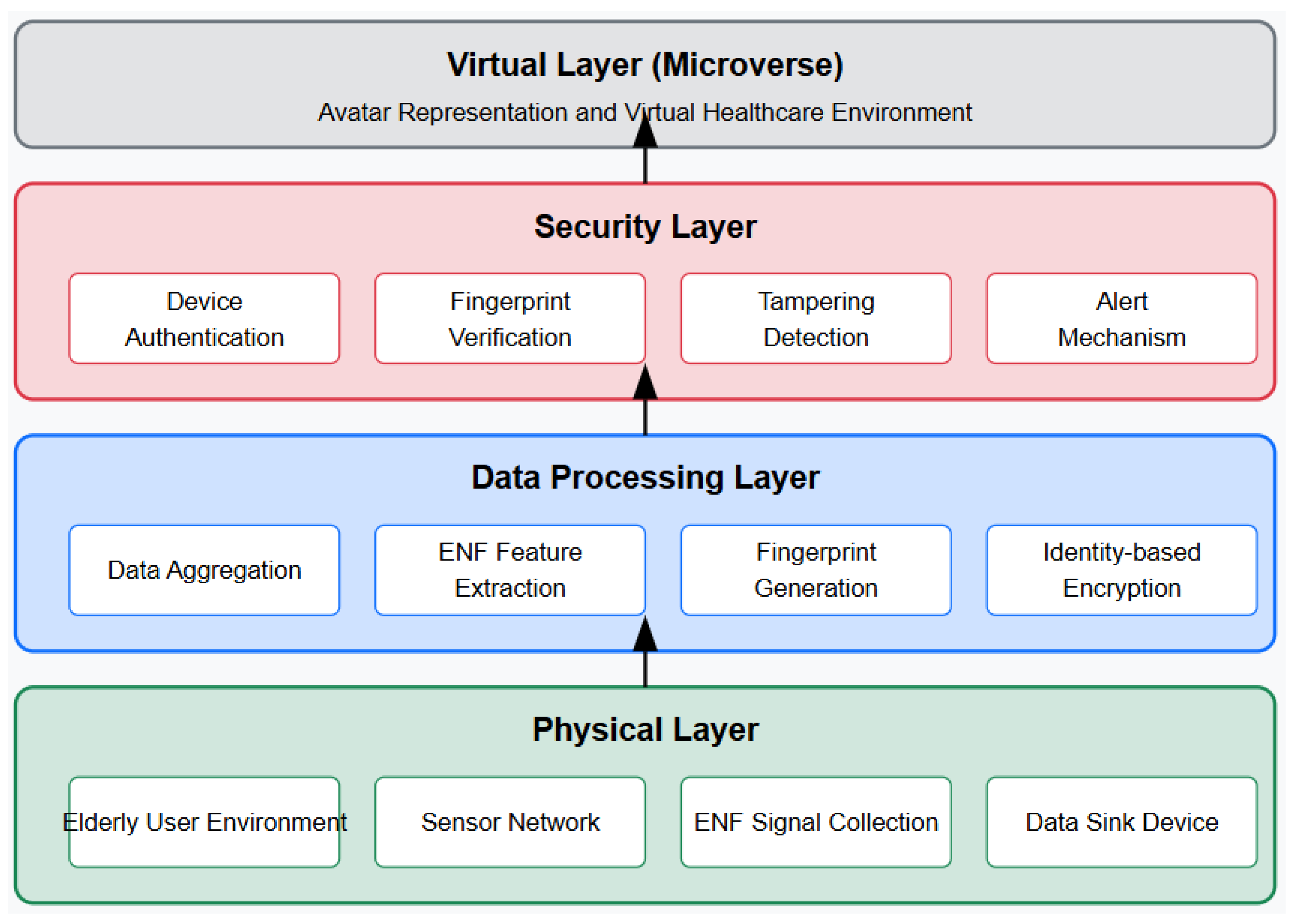

3. SAVE: System Design and Architecture

Figure 1 illustrates the high-level layered architecture of the SAVE framework, which consists of four interconnected layers designed to protect avatars in virtual healthcare settings. The SAVE framework follows a bottom-up approach, with information flowing from the physical world to its virtual representation. At the foundation lies the

Physical Layer, where data is collected from the elderly user’s environment through various sensors and ENF signal monitoring devices. This data then moves upward to the

Data Processing Layer, where it is aggregated, analyzed, and transformed into secure, verifiable fingerprints. The

Security Layer forms the crucial verification barrier, authenticating devices, validating ENF fingerprints, detecting tampering attempts, and triggering alerts when necessary. Finally, at the top lies the

Virtual Layer (Microverse), where authenticated information manifests itself as trusted and secure avatar representations within the virtual healthcare environment. This multi-layered architecture ensures that virtual representations of elderly users remain faithful to physical reality, protected against deepfake attacks and manipulation.

3.1. System Overview

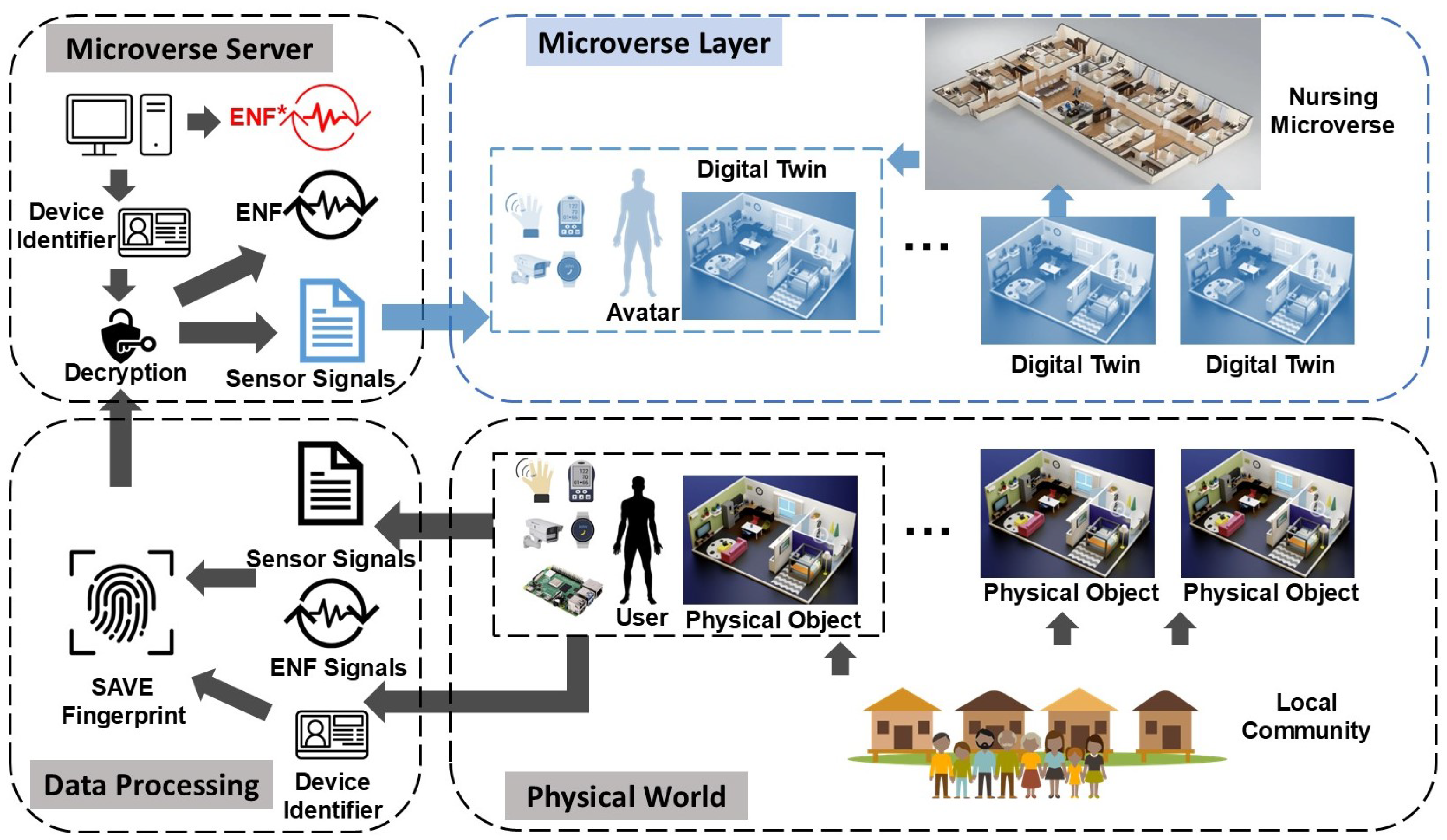

Based on the rationale for the design shown in

Figure 1, a more detailed virtual health system is proposed and illustrated in

Figure 2, which combines SAVE with the microverse instance to provide robust monitoring for elderly care. To protect the digital twinning process and detect Deepfake-style forgeries, the proposed system employs an ENF-based digital fingerprinting technique. ENF signals are subtle fluctuations in the frequency of the power grid that are inherently time-dependent and location-specific. These unique characteristics make ENF signals extremely difficult to fabricate or reproduce artificially.

Figure 2 depicts the Physical World layer, where sensor-equipped devices continuously monitor these ambient ENF traces, either through the pickup of electrical signals or through audio components susceptible to electromagnetic interference [

22].

From these ENF readings, a distinctive digital fingerprint is generated that encapsulates both temporal and spatial signal attributes. This fingerprint is then encrypted using a unique device identifier (ID), creating a secure binding between the data, the user’s physical location, and the exact time of capture. This encryption process, shown in the bottom-left Encryption block of the diagram, ensures that only the originating device or a verified party can decrypt and authenticate the data.

Upon transmission to the Microverse Server, the fingerprint is decrypted using the device ID or an associated cryptographic key. During the same time, the server records its own ENF signal as a reference. The decrypted user fingerprint is then compared with the server-side ENF trace. Because ENF signals are inherently tamper-evident, any modification, spoofing, or replay attack will lead to discrepancies between the two traces. If such inconsistencies are detected, the data is flagged as potentially manipulated or untrustworthy.

This

identity-based encryption (IBE) approach can integrate various cryptographic schemes, including RSA (Rivest-Shamir-Adleman), Digital Signature Algorithm (DSA), or Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC), depending on system requirements [

34]. In resource-constrained environments, such as edge devices used for virtual healthcare, ECC is particularly advantageous due to its shorter key lengths and lower computational overhead [

15,

35,

36]. ECC operates on a set of points that meet the equation of the elliptic curve

, where

a and

b are constants. These points, together with a special point at infinity, form a cryptographic group used for secure key exchange and identity verification.

3.2. ENF-Based Environmental Fingerprinting

The exponential growth of interconnected sensor networks within intelligent environments, such as smart homes, eldercare systems, and ambient assisted living platforms, has introduced new challenges in ensuring secure and efficient data authentication. Conventional cryptographic schemes, while effective, often impose significant computational and energy burdens that are unsuitable for resource-constrained edge devices. To address efficiency, we incorporate ENF signatures as an environmental authentication mechanism, providing a lightweight, context-aware method to verify data integrity and provenance.

ENF signals arise from subtle fluctuations in the frequency of the electrical power grid. These fluctuations are inherently time-varying and geographically localized, offering unique signatures that are difficult to forge or replicate. Previous studies have demonstrated the feasibility of using ENF traces as environmental fingerprints embedded in multimedia recordings or acquired directly through electromagnetic interference [

37]. In the SAVE framework, this principle is extended to a wide range of sensors, including audio, video, and physiological sensors, used in senior safety and health monitoring systems.

The ENF trace is either passively embedded within captured multimedia data or explicitly recorded using dedicated ENF capture sensors. These redundant ENF channels not only enhance resilience against device failures, but also support cross-validation across distributed sensing nodes. By associating ENF traces with time and location, the system inherently binds each data sample to its spatio-temporal context, enabling robust environmental authentication.

To perform ENF-based verification, we implement a signal estimation module using short-time Fourier transform (STFT) for frequency domain analysis and correlation coefficient matching to assess temporal consistency between signal segments [

21]. These lightweight signal processing techniques allow real-time comparison of ENF traces recorded from multiple independent sources. If the correlation between the server-side and device-side ENF traces falls below a predefined threshold, the data is flagged as suspicious or potentially manipulated.

While ENF signals are technically accessible to external actors, their effectiveness as an authentication tool is greatly strengthened when coupled with unique device IDs. This hybrid approach establishes a two-factor verification scheme: the environmental ENF signal and a device-specific cryptographic ID. Even if adversaries gain access to one component, the absence of the other, either the correct environmental signal or the authenticated device identity, renders spoofing attempts ineffective. This dual-authentication method significantly increases resistance to remote tampering, replay attacks, and sensor impersonation in decentralized monitoring environments. Together, the integration of ENF fingerprinting and device-level IDs forms a scalable, low-overhead authentication strategy suitable for edge-enabled health monitoring and smart community deployments.

3.3. Secure Authentication Framework

3.3.1. Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC)

Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC) is a highly efficient member of the public-key cryptography family, renowned for offering strong security with significantly smaller key sizes compared to traditional schemes such as RSA and DSA. The ECC is based on the algebraic structure of elliptic curves over finite fields, where the security is based on the computational intractability of the Discrete Logarithm Problem of Elliptic Curves (ECDLP) [

38]. Due to its lower computational overhead, ECC has emerged as an ideal cryptographic solution for resource-constrained environments, including edge computing and Internet of Medical Things (IoMT) infrastructures commonly deployed in virtual health monitoring systems [

15,

35,

36].

Unlike RSA, which requires key sizes of 2048 bits or more to achieve robust security, ECC can deliver equivalent levels of protection using keys as small as 256 bits. This substantial reduction in key length leads to reduced processing time, memory usage, and power consumption, critical advantages for edge devices such as wearable sensors, mobile health monitors, and smart gateways, where energy and computational resources are inherently limited. In these environments, efficient cryptographic operations are essential for real-time data protection and secure communication between distributed healthcare networks.

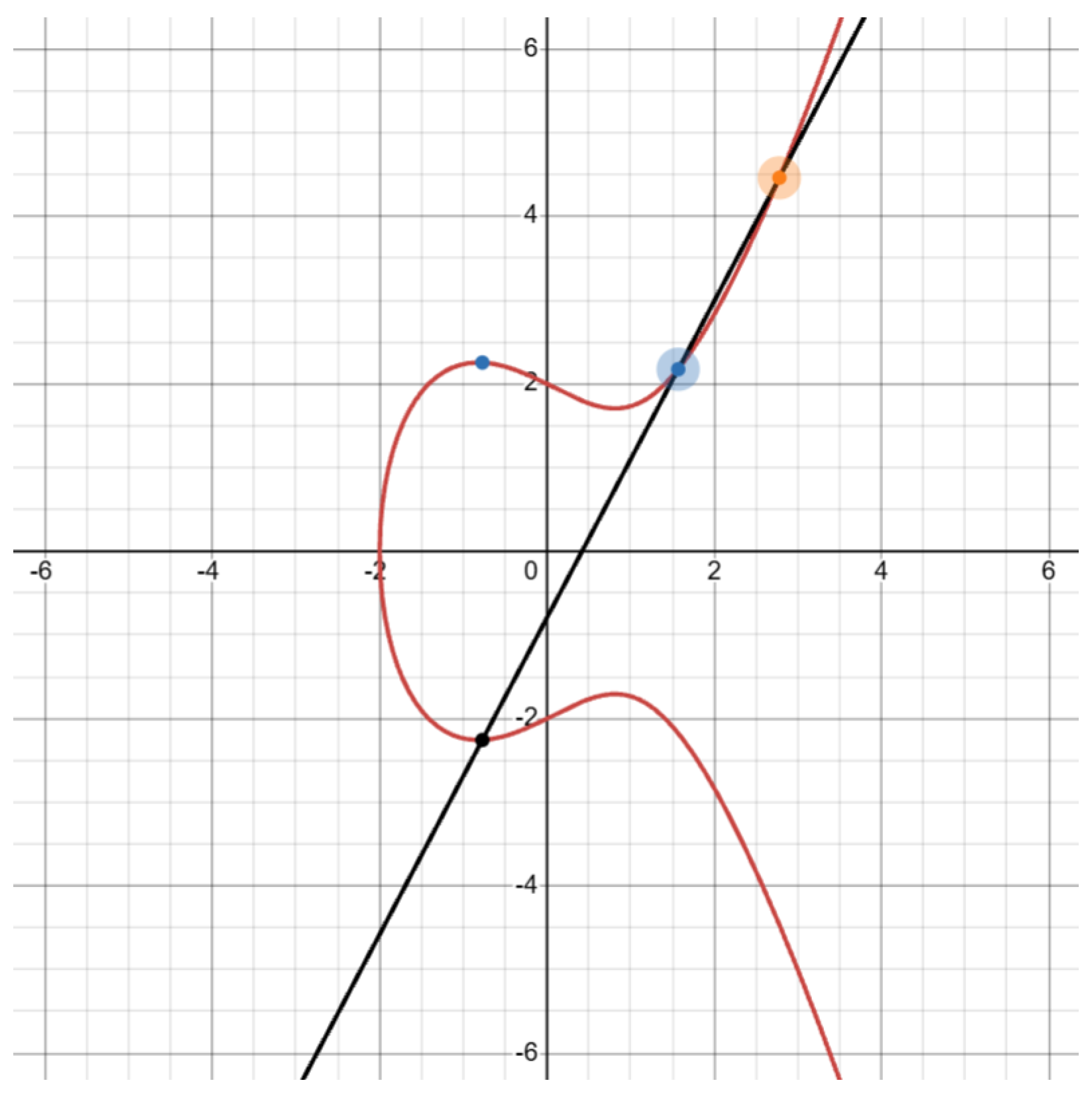

The core of ECC lies in the use of elliptic curves, which are sets of points that satisfy a specific mathematical equation, typically expressed as:

, where

a and

b are real or integer coefficients that define the shape of the curve. The points that satisfy this equation, along with a distinguished element known as the point at infinity, form a finite abelian group under a well-defined addition operation. This group structure enables cryptographic operations such as key generation, digital signatures, and encryption.

Figure 3 illustrates a typical elliptic curve of the form

, demonstrating the geometric interpretation of the underlying algebra.

In the context of virtual healthcare systems, ECC can be seamlessly integrated into secure communication protocols and authentication frameworks, ensuring data integrity and confidentiality without overwhelming the computational limits of edge devices. Its adaptability to constrained environments makes ECC a promising foundational component for next-generation secure telehealth infrastructures.

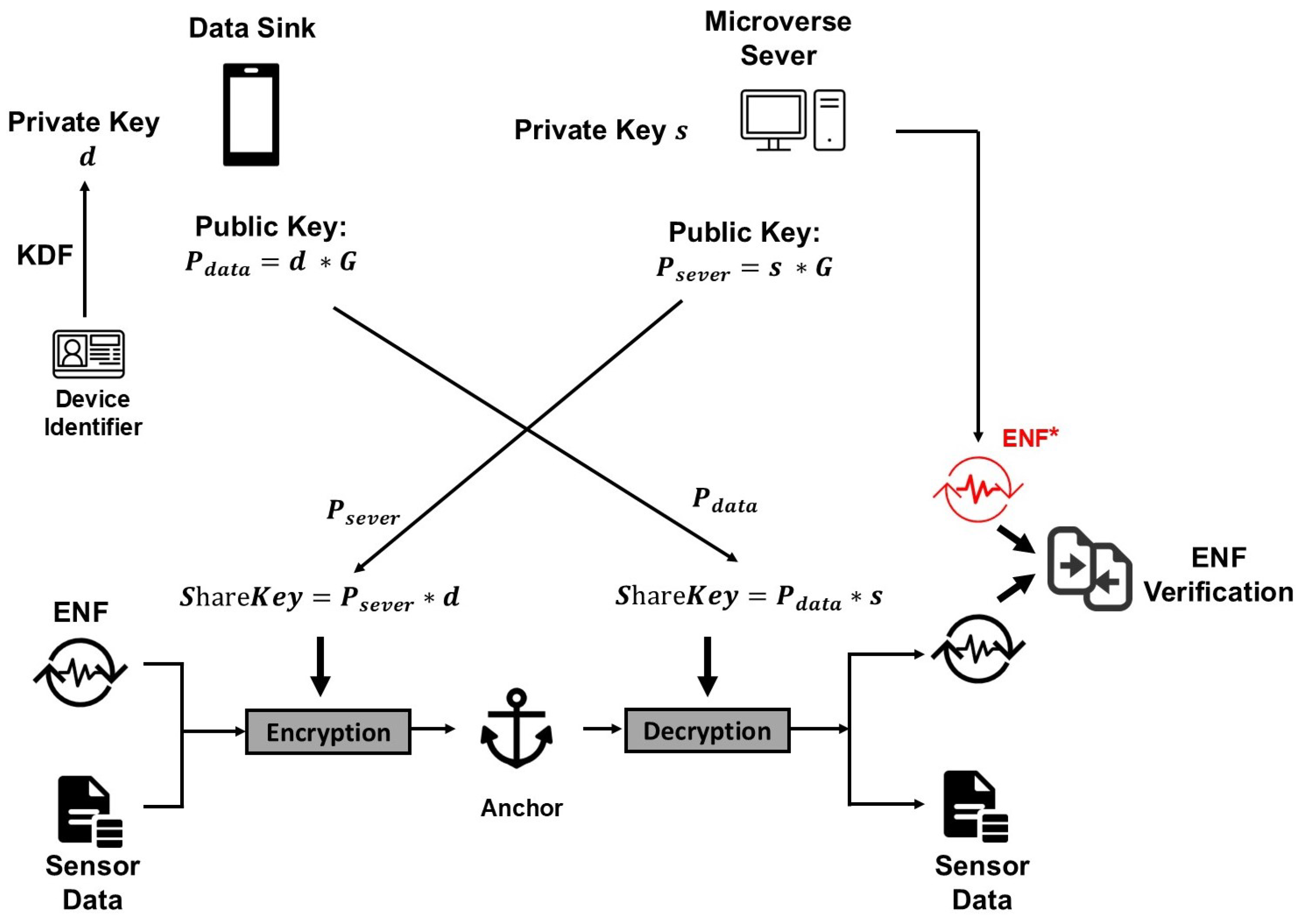

3.3.2. ECDH-Based Key Exchange Scheme

Elliptic Curve Diffie–Hellman (ECDH) is an efficient and secure key exchange protocol derived from the classical Diffie–Hellman Key Exchange (DHKE) scheme [

39]. While traditional DHKE relies on modular exponentiation over large prime fields, ECDH replaces this operation with elliptic curve point multiplication, significantly reducing computational complexity while maintaining equivalent cryptographic strength.

In an ECDH protocol, both the data sink (e.g., an edge device or client) and the server independently generate their own private keys, denoted by

d and

s, respectively. These private keys are used to compute the corresponding public keys by multiplying them by a predefined generator point

G on the elliptic curve. The security of the scheme is grounded in the mathematical property of elliptic curve point multiplication, which ensures that the following equality holds:

This equivalence property allows both communicating parties to independently compute a shared secret key without directly transmitting it over the communication channel. The shared key can then be used to encrypt and decrypt messages using a symmetric encryption algorithm.

The ECDH key exchange process is illustrated in

Figure 4 and summarized as follows:

The data sink generates the private key d based on the device identifier using the Key Derivation Function (KDF) and computes its public key: .

The server generates a random private key s and computes its public key: .

The data sink and the server exchange their public keys.

The data sink computes the shared key: .

The server computes the shared key: .

Both parties now possess the same shared secret key for symmetric encryption and decryption.

This protocol ensures that even if an adversary intercepts the public keys during transmission, the shared secret remains secure due to the computational hardness of the ECDLP. Consequently, ECDH is particularly well suited for bandwidth- and power-constrained environments such as IoMT and edge-based healthcare systems.

4. Implementation in Virtual Elder Care

To evaluate the effectiveness and demonstrate the practical feasibility of the proposed SAVE scheme, we present a detailed case study set within the context of a real-time patient monitoring system. The SAVE prototype is deployed in a virtual nursing home environment constructed using the Microverse platform, which provides a highly interactive and immersive DT framework. By simulating realistic healthcare scenarios, the case study allows us to assess the performance of the SAVE scheme in terms of security, responsiveness, and scalability of the system under dynamic and heterogeneous IoT conditions commonly encountered in smart healthcare infrastructures.

4.1. Microverse-Based Nursing Home Environment

The right portion of

Figure 2 presents the layered architectural design of a Microverse-based virtual health monitoring system, inspired by the concept of the small-scale Metaverse [

25]. The SAVE architecture supports real-time, immersive patient monitoring within a smart senior care community by integrating physical sensing, virtual representation, and intelligent analysis.

In the physical layer, the system reflects the actual living conditions of elderly residents in smart homes or institutional care settings. Each physical unit, whether an apartment, a private room, or a nursing home suite, is equipped with a variety of sensors, including smart cameras for skeletal imaging, motion detectors, and inertial measurement units. These devices continuously collect health-relevant data from the environment and the residents themselves.

This physical space is mirrored in the Microverse layer, where a DT of both the resident and their environment is instantiated in real time. Each resident’s unit is mapped to a dedicated Microverse instance, providing a one-to-one correspondence between physical and virtual domains. Through this virtual replication, real-time monitoring and behavioral tracking are achieved, allowing for continuous and remote observation of the individual’s well-being. Within each instance, a Distributed Intelligent Health Monitoring (DIHM) framework is deployed to handle on-site data processing, anomaly detection, and rapid response generation. The localized intelligence enables timely interventions without relying solely on cloud-based infrastructure.

In terms of system integration, the Microverse architecture aligns with the edge–fog–cloud computing paradigm [

40]. Microverse instances operate primarily at the edge and fog layers, where computational proximity ensures low-latency responsiveness and efficient resource utilization for real-time healthcare services. As a natural extension, multiple Microverse instances can be federated into a broader Metaverse layer operating in the cloud. This higher-level integration opens opportunities for more sophisticated tasks such as advanced diagnostic analytics, long-term health trend modeling, and coordinated healthcare resource allocation across communities. However, the current paper focuses exclusively on the functionalities and capabilities of individual Microverse instances, with the community-level Metaverse vision left for future investigation.

To support immersive visualization and interaction, the Microverse environment is built using Unreal Engine 5 (UE5) [

41], a high-fidelity 3D modeling engine capable of generating life-like digital replicas.

Figure 5 shows that each resident’s living space is rendered with realistic furniture arrangements and layouts of the environment, while a personalized avatar is created to represent the individual within the virtual space. The avatar’s appearance and posture are continuously updated based on real-time sensor data, particularly skeletal information derived from the optic camera input. This dynamic avatar update mechanism ensures that visual cues, such as posture anomalies or fall detection, are intuitively communicated to caregivers and authorized agents via the system’s graphical user interface (GUI).

In addition, the GUI provides interactive monitoring features, including visual alerts, severity-based alarm levels, and status summaries, empowering caregivers with actionable insights. This tightly integrated virtual environment not only enhances situational awareness but also serves as a scalable foundation for intelligent, responsive eldercare in future smart communities.

4.2. Sensor Deployment

To enable real-time health monitoring within the Microverse-based nursing home environment, a heterogeneous set of sensors is strategically deployed in each residential unit to capture multi-modal data streams reflecting both the physical environment and the physiological conditions of the elderly resident. These sensors form the critical data acquisition layer that drives intelligent analytics, human activity recognition (HAR), and virtual representations within the Microverse system [

42,

43].

4.2.1. Hardware Configuration

The sensor network includes the following core components:

Motion Sensors: Passive Infrared (PIR) and ultrasonic motion sensors are installed at key locations (e.g., near beds, doors, and bathrooms) to detect movement patterns, presence, and activity levels. These are essential for behavioral profiling and fall detection.

Smart Cameras: Depth and RGB (red, green, and blue) cameras with embedded AI capabilities are deployed to perform real-time skeletal tracking, posture analysis, and anomaly detection. Cameras are installed at high vantage points to maximize coverage while preserving privacy through body-skeleton abstraction.

Thermometers: Non-contact infrared thermometers continuously measure ambient and body surface temperature. These sensors are placed in living quarters and integrated with bedside systems to monitor possible signs of fever or thermal stress.

Humidity Sensors: Capacitive humidity sensors are used to assess the level of moisture in the environment, ensuring that the conditions of the room remain within the medically recommended comfort thresholds for respiratory health.

All sensors are connected to a local edge computing unit, typically a single-board computer (e.g., NVIDIA Jetson Nano or Raspberry Pi 5), which performs initial data processing and facilitates communication with the Microverse engine via a secure local area network.

4.2.2. Data Collection Parameters

Each sensor type operates with a predefined sampling rate optimized for its function:

Motion Sensors: Sampled at 1–2 Hz, sufficient for capturing discrete activity events without excessive data redundancy.

Smart Cameras: Operate at 15–30 frames per second (fps), allowing smooth and accurate skeletal modeling and behavior inference.

Thermometers: Sampled every 0.1 seconds to capture gradual temperature fluctuations while saving energy.

Humidity Sensors: Sampled every 1–2 minutes, as the environmental humidity changes slowly over time.

To reduce bandwidth and computational overhead, an adaptive data fusion mechanism is implemented at the edge node [

44]. Motion events are stored as timestamped activity logs, while camera frames are processed to extract skeleton keypoints and only send summary vectors (e.g., joint angles, posture scores) to the virtual environment. Temperature and humidity readings are averaged over sliding windows (e.g., 5-minute intervals) unless anomalies are detected, in which case raw data are retained and transmitted.

Data transmission is managed via a lightweight and secure MQTT (Message Queuing Telemetry Transport) protocol for scalable communication between edge nodes and the Microverse platform. Real-time and critical alerts (e.g., fall detection, sudden fever spikes) are prioritized and transmitted immediately, while noncritical data are batched and sent periodically to reduce network load.

The combined sensing and transmission framework ensures a balance between continuous monitoring fidelity and system efficiency, enabling scalable deployment across multiple Microverse instances while preserving low latency and high reliability for time-sensitive healthcare scenarios.

4.3. Security Integration

In SAVE, the ENF signal is either directly extracted from a power line voltage via voltage sensors or indirectly captured using co-located audio/video devices susceptible to ENF-induced noise. The extracted ENF signature is embedded into the sensor data stream as timestamped frequency vectors. Each sensor node appends its local ENF sequence alongside its main payload (such as motion activity, temperature readings, or skeletal data), creating a synchronized data structure that includes environmental fingerprints.

A reference ENF sequence is collected simultaneously on the server side as ground truth using a dedicated ENF monitoring device. After receiving and processing the data sequence, the server performs a correlation analysis between the embedded ENF sequence and the reference ENF signal using a sliding-window approach. Specifically, the Pearson correlation coefficient is calculated in 2- to 10-second windows to assess the similarity between the two sequences. A correlation value close to 1 indicates consistent and reliable data. However, significant drops in correlation (e.g., below 0.8) are treated as potential indicators of tampering, synchronization failure, or device compromise.

To manage ENF anomalies, we design a multi-level alert scheme. A Level 1 alert is issued when the correlation dips moderately (e.g., 0.8 to 0.85) in isolated instances, flagging the data for logging without halting operations. Level 2 alerts are triggered by repeated or sustained correlation drops below 0.8, prompting the system to quarantine the affected data and initiate cross-checks from redundant sensor streams. Finally, a Level 3 alert represents a critical event where the correlation falls below 0.6, indicating a high probability of forgery or injection attacks. In this case, immediate notifications are sent to caregivers and system administrators, and automatic recovery actions are executed, such as restarting the edge node or switching to a backup instance.

5. Experimental Evaluation

5.1. Experimental Setup

To evaluate the feasibility of the proposed SAVE framework, we developed a proof-of-concept prototype system and conducted experiments within a controlled Microverse environment. The prototype was implemented primarily using Python and C++, and deployed over a physical local area network (LAN) to simulate realistic conditions. The experimental testbed, summarized in

Table 1, consists of a laptop (Alienware m15), a Raspberry Pi 5 (RPi 5) labeled RPi A, a webcam, and multiple environmental and biometric sensors. Additionally, seven more RPi5s, labeled as B to H, are also configured with the same software environment for further evaluation of scalability.

The laptop, located on a different floor of the building, functions as the Microverse server. It maintains the virtual environment and synchronizes avatar states in real time using biometric data streams, as illustrated in

Figure 5. The Rpi A is equipped with a smartwatch, a Logi webcam, and additional sensors, and operates as a data collection and transmission node. Each device, including the RPi A, is registered with a unique identifier on the Microverse server. Simultaneous acquisition of ENF signals is performed on each RPi 5 and laptop to enable temporal correlation and authentication.

5.2. Attack Scenarios

To validate the SAVE framework under adversarial conditions, we simulated three distinct attack scenarios using the collected ENF signals. Each scenario was repeated for ten experimental epochs, each epoch lasting 30 minutes. Attacks were triggered at randomly selected time points within each epoch to ensure variability and robustness in the evaluation. The three types of attacks are:

an attacker tries to feed fake data but has no information of the device ID (private keys) nor the elliptic curve;

an attacker obtained all information about encryption/decryption and intercepts the channel with deepfake data but is unaware of or does not have sufficient/correct information of current ENF signals; and

an attacker obtained all information about encryption/decryption from both agents and tampered with the user’s behavior description data using intercepted data packets from earlier communication.

5.3. Results Analysis

5.3.1. Attack Detection Effectiveness

In the first attack scenario, the absence of the correct cryptographic information prevents the adversary from successfully decrypting the ciphertext, allowing the SAVE framework to easily identify and reject the tampered data stream. Without valid decryption, the received data are unintelligible or misformed, providing a clear indication of compromise.

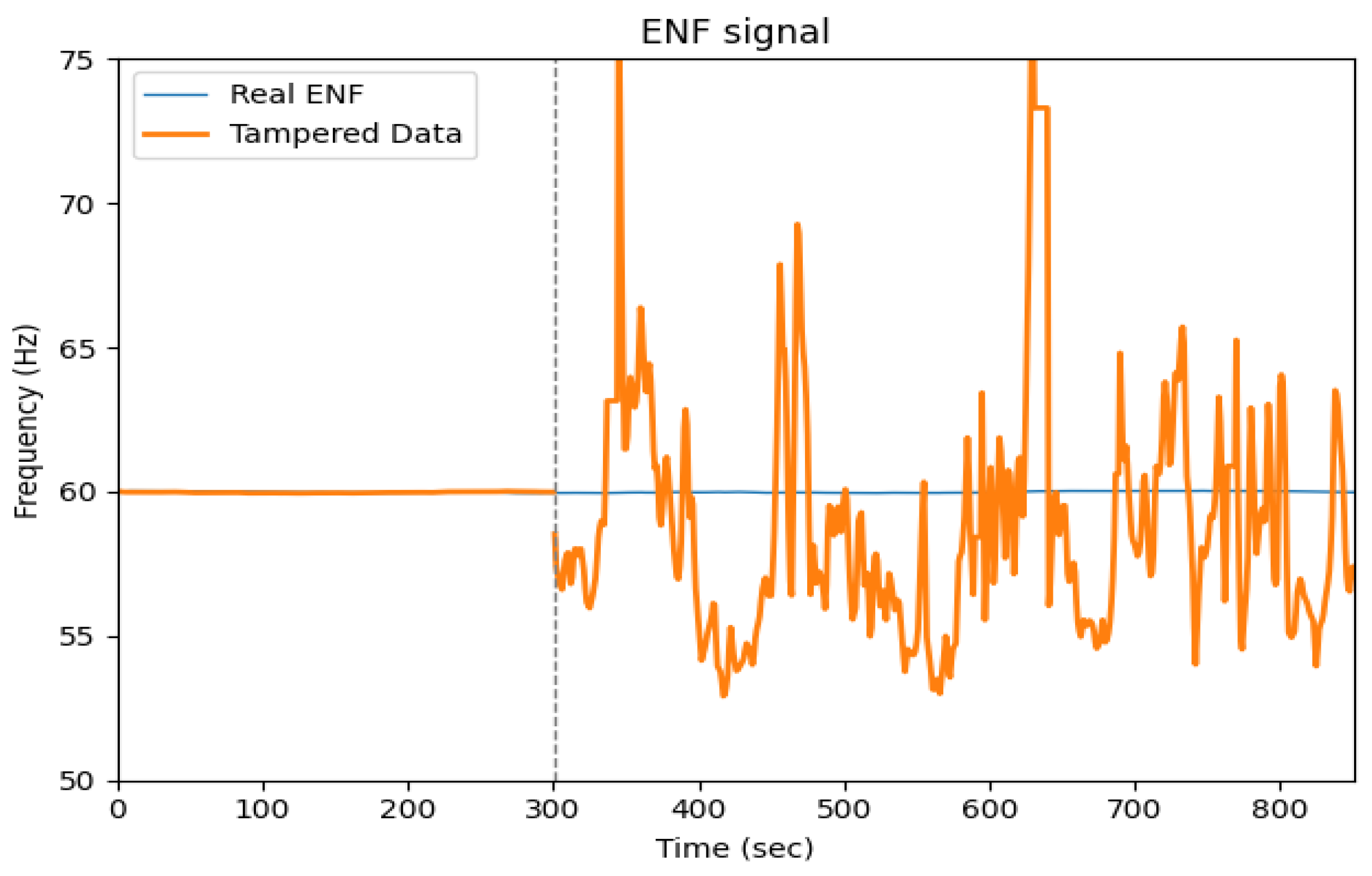

In the second scenario, we demonstrate a more subtle tampering attempt using heart rate data as a representative sensor signal. The original raw data includes not only the heart rate sequence (in beats per minute), but also the ENF. However, an attacker unaware of the embedded ENF may assume the data contains only physiological readings and may generate a synthetic (deepfaked) heart rate sequence without replicating or inserting the correct ENF.

Figure 6 highlights the ENF as a case study, where the synthetic heart rate waveform exhibits frequency and amplitude characteristics that differ significantly from those of the original ENF signal. This discrepancy leads to detectable inconsistencies between the physiological data and the environmental context. Our analysis demonstrates that even advanced tampering techniques fail to replicate the nuanced correlation between real-world anchors and sensor data. When subjected to frequency domain analysis, these mismatches allow for reliable detection of falsified signals, underscoring the robustness of environmental fingerprint-based authentication.

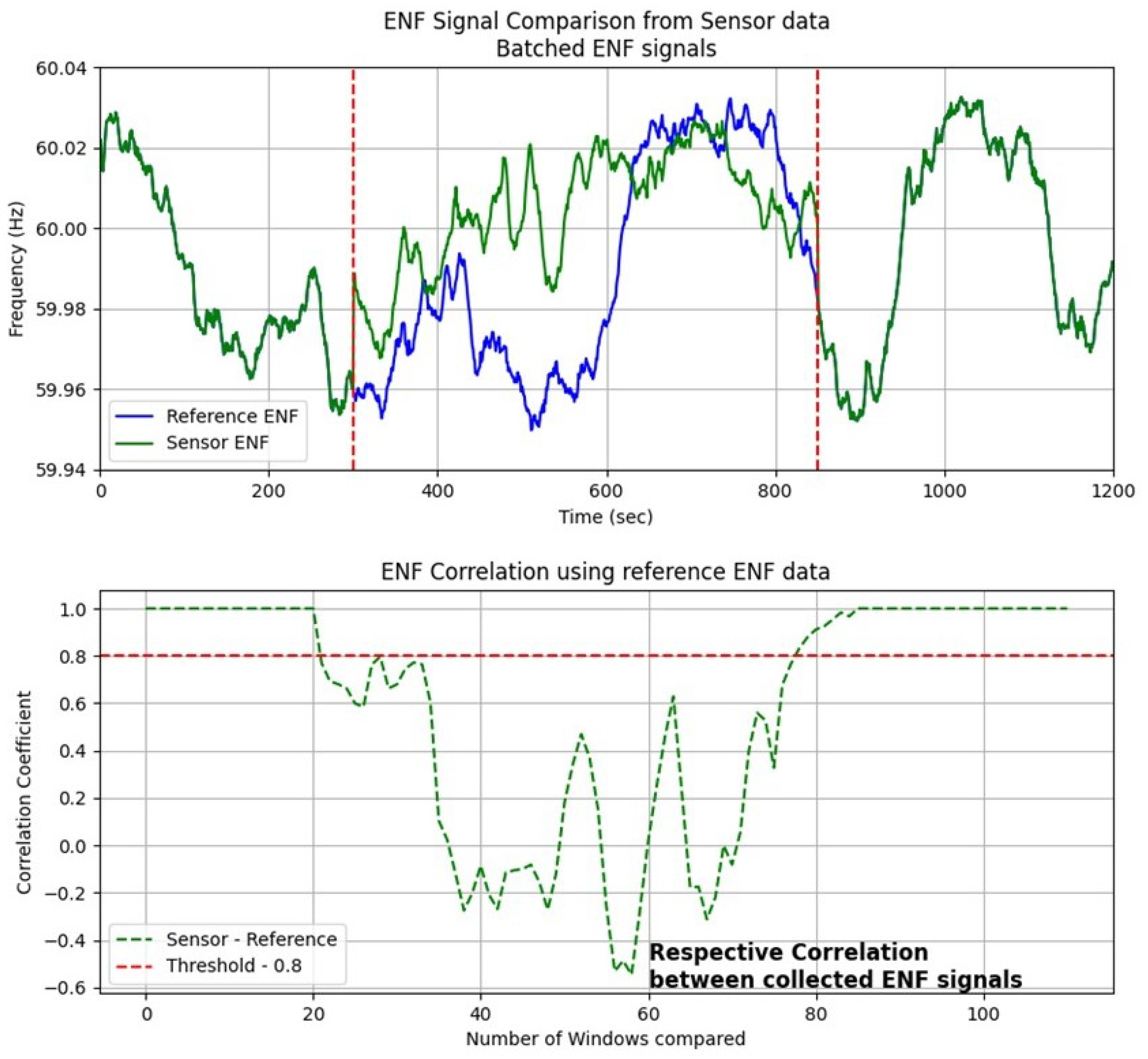

In the third scenario, the attacker is fully aware of the presence of ENF signals used for authentication within the system. To bypass the defense, the attacker attempts a replay attack by injecting previously intercepted data packets into the communication channel. To counteract this, the SAVE framework utilizes ENF signals as authentication anchors, using their high sampling rate, temporal uniqueness, and geographic consistency.

Figure 7 illustrates the SAVE continuous authentication process based on timestamp-synchronized ENF signal comparisons.

Figure 7 includes two complementary plots. The upper plot presents the raw ENF signals collected from two sources: the reference ENF (blue line), obtained on the server side, and the sensor-side ENF (green line), captured from the data sink device. Both signals are plotted as functions of time (in seconds), with frequency (Hz) on the vertical axis. The natural fluctuations in these waveforms reflect the time-varying characteristics that make the ENF a reliable environmental fingerprint. The regions highlighted between the red dashed vertical lines indicate the analysis windows where signal comparison is performed.

The lower plot quantifies the similarity of the signal using correlation coefficient analysis in multiple time windows. A correlation threshold of 0.8 is adopted based on previous empirical studies and associated false positive rates [

29]. The green curve shows the correlation values over time, while the red dashed horizontal line denotes the authentication threshold. A significant drop below this threshold, such as the one observed around window 40, indicates a likely tampering event, where the injected data do not align with the real-time ENF signature.

This experiment demonstrates that even in the presence of key compromise, replay attacks can be reliably detected. The attacker’s inability to regenerate authentic, temporally aligned ENF signals exposes the tampering, highlighting the robustness of SAVE to maintain continuous, real-time integrity verification through environmental fingerprinting.

5.3.2. Scalability Evaluation

To assess the scalability of the proposed IoT network architecture, we conducted an empirical evaluation of the end-to-end processing delay under varying device loads using the MQTT protocol [

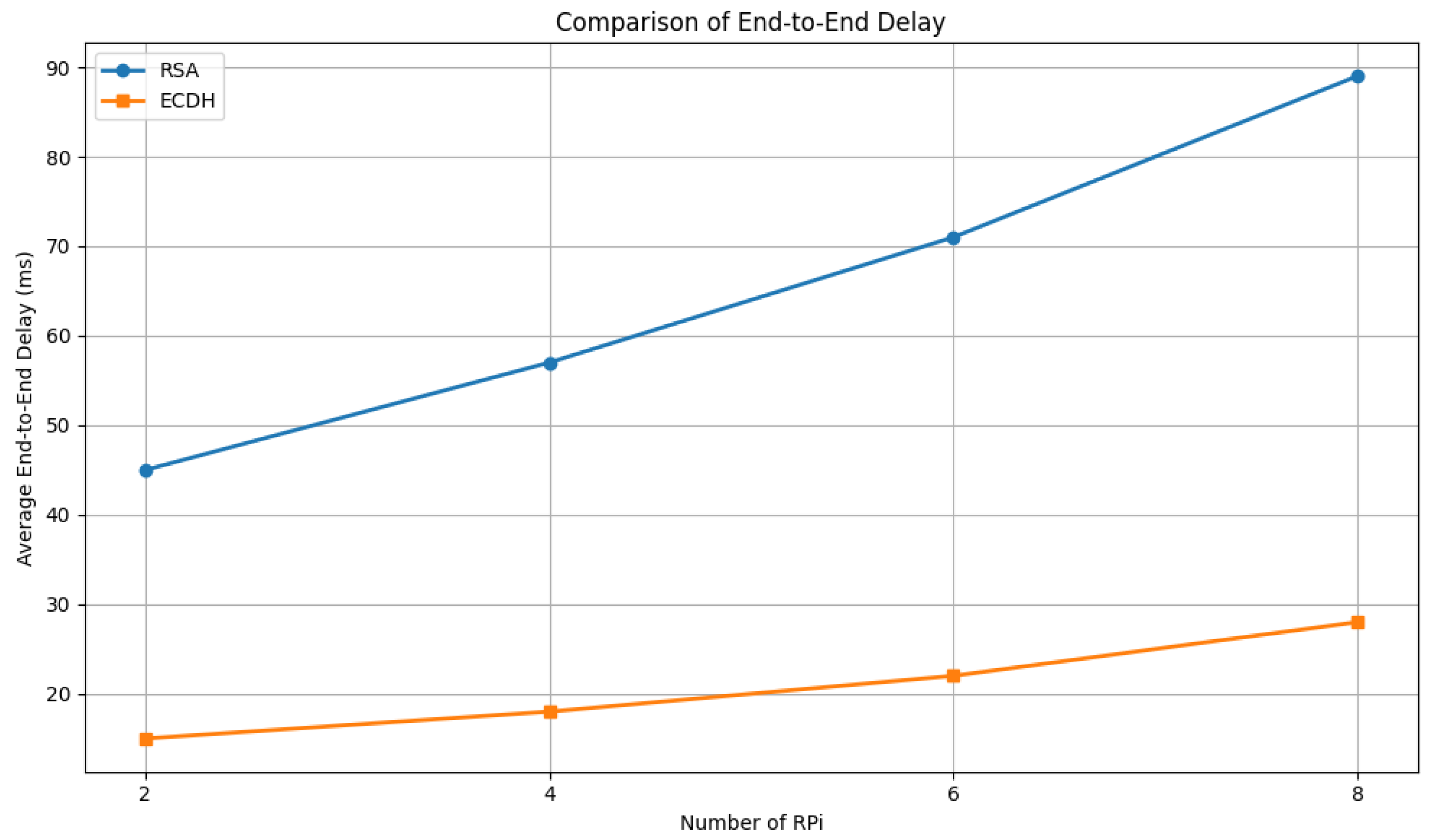

45]. The testbed consists of up to eight Raspberry Pi 5 (RPi5) nodes acting as the publishers and a centralized laptop server as the message “broker". Each RPi5 encrypts sensor data using a symmetric-key Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) key derived from an ECDH key exchange with the server and transmits the encrypted payload via MQTT. We also performed RSA-1024 as the reference method to evaluate the performance of ECDH (secp256r1).

The end-to-end delay is decomposed into three components:

Encryption Time: The time required to perform encryption of the plain text sensor data on the RPi5;

Transmission Time: The time taken to transmit the encrypted message over the MQTT protocol from the RPi5 to the server; and

Decryption Time: The time required to decipher the message received on the server.

To evaluate scalability, we incrementally increased the number of active RPi5 devices from two to eight and measured the average end-to-end delay across 100 messages per device. Each measurement captures the time interval from message creation and encryption in the RPi5 to successful decryption and parsing at the server. The results indicate a consistent increase in total processing time with the number of devices, primarily attributed to the cumulative transmission load and the concurrent message handling.

Figure 8 illustrates the relationship between the number of connected RPi5 devices and the average end-to-end delay. ECDH consistently outperforms RSA in terms of latency, with significantly lower delay values at each device count. Specifically, the average end-to-end delay for ECDH increases modestly from 15 ms to 28 ms as the number of devices grows from 2 to 8, reflecting a near-linear and scalable behavior. In contrast, RSA exhibits a steeper growth curve, with delays rising from 45 ms to 89 ms over the same range, indicating a higher computational overhead and poorer scalability. These results suggest that ECDH is more suitable for resource-constrained and latency-sensitive environments, offering more efficient key exchange without compromising responsiveness as device counts increase. The findings confirm ECDH as a lightweight and scalable alternative to RSA for secure communication in distributed IoT networks.

6. Discussions

6.1. Key Findings and Insights

This study demonstrates the feasibility and effectiveness of the SAVE framework for secure, real-time monitoring in smart healthcare environments, leveraging environmental fingerprinting via ENF signals. The integration of ENF-based authentication within the Microverse virtual nursing home platform offers several notable advantages in terms of data integrity verification, adversarial resilience, and operational scalability.

The results of the case study validate the robustness of ENF signal correlation as a lightweight yet effective authentication mechanism. Across simulated attack scenarios, the framework successfully identified data injection, replay, and deepfake attacks, even in the presence of key compromise. By embedding time-stamped ENF sequences into sensor data and performing continuous correlation analysis with a server-side reference signal, the SAVE system enables persistent and low-cost verification of data authenticity. The SAVE approach improves traditional cryptographic defenses by linking authentication to the spatio-temporal environmental context, which is inherently difficult for attackers to replicate.

Secondly, the real-time performance and low-latency characteristics of ECDH-AES-based communication confirm the practical applicability of the proposed system in dynamic IoT environments. Our evaluation of end-to-end delays under varying device counts showed that ECDH consistently achieves lower latency than RSA, scaling efficiently from two to eight RPi 5 nodes. The modest increase in delay (from 15 ms to 28 ms) under ECDH underscores its suitability for time-sensitive healthcare applications, where rapid data processing and responsiveness are crucial.

In addition, the use of a distributed edge–fog–cloud architecture via Microverse instances significantly reduces the reliance on centralized cloud services. By offloading data aggregation, anomaly detection, and initial ENF embedding to local edge nodes, the system achieves both scalability and resilience, supporting individualized monitoring while enabling community-wide integration in future Metaverse extensions.

The graphical interface, designed using Unreal Engine 5, also offers an intuitive and immersive visualization layer that bridges the physical and virtual realms. Through personalized avatars, skeletal tracking, and real-time alerts, caregivers can maintain situational awareness and respond quickly to anomalies without physically intervening.

6.2. Limitations

Despite the promising results, several limitations and practical considerations must be acknowledged.

First, ENF-based authentication is inherently dependent on the availability and quality of environmental power line signals. In certain wireless, outdoor, or off-grid environments, such as rural clinics or mobile care units, the absence of stable sources of ENF may hinder the effectiveness of this method. Additionally, the quality of ENF signals captured through indirect means (e.g., via microphones or cameras) may vary due to ambient noise, sampling resolution, or hardware differences, potentially reducing correlation accuracy.

Although the computational overhead of ENF correlation is relatively low, the real-time processing requirement across multiple time windows can become burdensome in large-scale deployments with high sensor density. Sliding-window correlation and anomaly detection, when performed continuously, can impose processing delays or increase power consumption on resource-constrained edge devices, particularly in configurations with multiple high-frame-rate smart cameras or biometric sensors.

The scalability of secure communication protocols such as MQTT combined with ECDH-AES encryption, while more efficient than RSA, still faces throughput and congestion challenges in networks with dozens or hundreds of devices. As the number of Microverse instances increases, message collision, broker saturation, and synchronization drift may introduce performance bottlenecks, especially in high-latency or lossy network environments.

6.3. Future Work

Although the proposed SAVE framework has demonstrated its effectiveness in real-time authentication and anomaly detection through ENF-based environmental fingerprinting, several promising avenues remain for future research and system enhancement.

An important direction is the extension of environmental fingerprinting beyond ENF signals to incorporate other physical-layer phenomena as authentication anchors. For example, ambient light fluctuations, electromagnetic interference patterns, acoustic signatures, or temperature noise can serve as complementary modalities to enrich the environmental context. By combining multiple environmental signals, the system can achieve greater robustness and resilience, especially in scenarios where one modality (e.g., ENF) may be weak or unavailable. This multimodal approach will also help reduce false positives and improve the system’s adaptability to various deployment environments.

The SAVE framework primarily focuses on continuous authentication and tamper detection at the sensor data level. Future efforts will explore tighter integration with other cybersecurity primitives, such as secure bootstrapping, blockchain-based audit trails, and federated identity management. For example, blockchain can be used to log ENF correlation scores as the Proof of ENF (PoENF) [

29] and to immutably support anomaly alerts [

46], thereby enhancing forensic traceability and trust management in distributed healthcare settings. Additionally, integrating SAVE with hardware-level security modules, such as trusted platform modules (TPMs) or physical unclonable functions (PUFs), may further safeguard device identities and key material, reducing the attack surface.

Although correlation analysis with fixed thresholds provides a lightweight and interpretable method to detect tampering, it may not fully capture the complexity of advanced attack patterns or subtle anomalies. Future work will incorporate machine learning (ML) techniques, such as time series classification, deep autoencoders, or graph-based anomaly detection, to model normal signal behavior and dynamically adapt to evolving threats. These ML models could learn contextual patterns in ENF or multimodal signals and offer probabilistic threat scoring, allowing more nuanced and adaptive alert mechanisms. Furthermore, edge-deployable learning models will be considered to support on-device intelligence without relying on centralized servers.

7. Conclusion

This paper introduces SAVE (Securing Avatars in Virtual Environments), a novel framework that addresses critical security challenges in virtual healthcare environments through environmental fingerprinting based on Electric Network Frequency (ENF) signals. As Metaverse technologies expand in healthcare applications, particularly for vulnerable populations such as elderly individuals living alone, ensuring the authenticity and integrity of virtual representations becomes paramount for maintaining trust and safety. The SAVE framework demonstrates that physical environmental fingerprints can effectively bridge the gap between virtual and physical realities by leveraging the unique temporal and spatial characteristics of ENF signals combined with elliptic-curve cryptography. Our experimental evaluation in a Microverse-based nursing home environment validates the approach’s effectiveness across multiple attack scenarios, successfully detecting unauthorized access, device spoofing, and replay attacks with high accuracy and minimal false positives.

Although the current implementation focuses on ENF signals as the primary environmental fingerprint, the SAVE framework architecture supports extension to incorporate additional environmental modalities such as ambient light patterns and acoustic signatures. This multimodal capability represents a significant advancement in securing virtual healthcare environments and establishes important foundations for future research in environmental fingerprinting in diverse deployment scenarios.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.Q., Y.C. and E.B.; methodology, Q.Q, and Y.C.; software, Q.Q.; validation, Q.Q. and Y.C.; formal analysis, Q.Q.; investigation, Q.Q.; resources, Y.C. and E.B.; data curation, Q.Q.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.Q., Y.C. and E.B.; writing—review and editing, Q.Q., Y.C. and E.B.; visualization, Q.Q.; supervision, Y.C. and E.B.; project administration, Y.C.; funding acquisition, Y.C.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AES |

Advanced Encryption Standard |

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| DHKE |

Diffie–Hellman Key Exchange |

| DIHM |

Distributed Intelligent Health Monitoring |

| DSA |

Digital Signature Algorithm |

| DT |

Digital Twin |

| ECC |

Elliptic Curve Cryptography |

| ECDH |

Elliptic Curve Diffie–Hellman |

| ECDLP |

Elliptic Curve Discrete Logarithm Problem |

| ENF |

Electric Network Frequency |

| FNR |

False Negative Rate |

| FPR |

False Positive Rate |

| FPS |

Frames per Second |

| GUI |

Graphic User Interface |

| HAR |

Human Activity Recognition |

| IBE |

Identity-based Encryption |

| IoMT |

Internet of Medical Things |

| IoT |

Internet of Things |

| KDF |

Key Deviation Function |

| LAN |

Local Area Network |

| LSTM |

Long Short Term Memory |

| ML |

Machine Learning |

| MQTT |

Message Queuing Telemetry Transport |

| PIR |

Passive Infrared |

| PoENF |

Proof of ENF |

| PRNG |

Pseudorandom Number Generator |

| PUF |

Physical Unclonable Functions |

| RGB |

red, green, and blue |

| RPi |

Raspberry Pi |

| RSA |

Rivest–Shamir–Adleman |

| STFT |

Short-time Fourier Transform |

| TPM |

Trusted Platform Modules |

| UE5 |

Unreal Engine 5 |

| UMG |

Unreal Motion Graphics |

References

- Bibri, S.E. The social shaping of the metaverse as an alternative to the imaginaries of data-driven smart Cities: A study in science, technology, and society. Smart Cities 2022, 5, 832–874. [CrossRef]

- Musamih, A.; Yaqoob, I.; Salah, K.; Jayaraman, R.; Al-Hammadi, Y.; Omar, M.; Ellahham, S. Metaverse in healthcare: Applications, challenges, and future directions. IEEE Consumer Electronics Magazine 2022, 12, 33–46. [CrossRef]

- Yeganeh, L.N.; Fenty, N.S.; Chen, Y.; Simpson, A.; Hatami, M. The future of education: A multi-layered metaverse classroom model for immersive and inclusive learning. Future Internet 2025, 17, 63. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Ning, H.; Lin, Y.; Wang, W.; Dhelim, S.; Farha, F.; Ding, J.; Daneshmand, M. A survey on the metaverse: The state-of-the-art, technologies, applications, and challenges. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2023, 10, 14671–14688. [CrossRef]

- Gu, D.; Andreev, K.; Dupre, M.E. Major trends in population growth around the world. China CDC weekly 2021, 3, 604. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navaneetham, K.; Arunachalam, D. Global population aging, 1950–2050. In Handbook of Aging, Health and Public Policy: Perspectives from Asia; Springer, 2023; pp. 1–18.

- Melgar, M. Use of respiratory syncytial virus vaccines in older adults: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2023. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report 2023, 72. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- US-Census-Bureau. The Older Population in the United States: 2023. https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2020/demo/p25-1145.html, 2024. Accessed: 2024-07-17.

- Boschert, S.; Rosen, R. Digital twin—the simulation aspect. Mechatronic futures: Challenges and solutions for mechatronic systems and their designers 2016, pp. 59–74.

- Sun, T.; He, X.; Li, Z. Digital twin in healthcare: Recent updates and challenges. Digital Health 2023, 9, 20552076221149651. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wickramasinghe, N.; Ulapane, N.; Andargoli, A.; Ossai, C.; Shuakat, N.; Nguyen, T.; Zelcer, J. Digital twins to enable better precision and personalized dementia care. JAMIA open 2022, 5, ooac072. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Su, Z.; Zhang, N.; Xing, R.; Liu, D.; Luan, T.H.; Shen, X. A survey on metaverse: Fundamentals, security, and privacy. IEEE communications surveys & tutorials 2022, 25, 319–352.

- Wang, J.; Makowski, S.; Cieślik, A.; Lv, H.; Lv, Z. Fake news in virtual community, virtual society, and metaverse: A survey. IEEE Transactions on Computational Social Systems 2023. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, B.B.; Gaurav, A.; Arya, V. Fuzzy logic and biometric-based lightweight cryptographic authentication for metaverse security. Applied Soft Computing 2024, 164, 111973. [CrossRef]

- Thakur, G.; Kumar, P.; Chen, C.M.; Vasilakos, A.V.; Prajapat, S.; et al. A robust privacy-preserving ecc-based three-factor authentication scheme for metaverse environment. Computer Communications 2023, 211, 271–285. [CrossRef]

- Ruiu, P.; Nitti, M.; Pilloni, V.; Cadoni, M.; Grosso, E.; Fadda, M. Metaverse & Human Digital Twin: Digital Identity, Biometrics, and Privacy in the Future Virtual Worlds. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction 2024, 8, 48. [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Zhang, Z.; Youliang, T.; Ma, J. A secure authentication framework to guarantee the traceability of avatars in metaverse. IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security 2023, 18, 3817–3832. [CrossRef]

- Grigoras, C. Applications of ENF criterion in forensic audio, video, computer and telecommunication analysis. Forensic science international 2007, 167, 136–145. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, Q.; Chen, Y. ANCHOR: authenticating avatars and virtual objects via anchors in the real world. In Proceedings of the Disruptive Technologies in Information Sciences IX. SPIE, 2025, Vol. 13480, pp. 237–253.

- Ngharamike, E.; Ang, L.M.; Seng, K.P.; Wang, M. ENF based digital multimedia forensics: Survey, application, challenges and future work. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 101241–101272. [CrossRef]

- Nagothu, D.; Chen, Y.; Blasch, E.; Aved, A.; Zhu, S. Detecting malicious false frame injection attacks on surveillance systems at the edge using electrical network frequency signals. Sensors 2019, 19, 2424. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagothu, D.; Xu, R.; Chen, Y.; Blasch, E.; Ardiles-Cruz, E. Application of Electrical Network Frequency as an Entropy Generator in Distributed Systems. In Proceedings of the NAECON 2023-IEEE National Aerospace and Electronics Conference. IEEE, 2023, pp. 233–238.

- Liu, Y.; You, S.; Yao, W.; Cui, Y.; Wu, L.; Zhou, D.; Zhao, J.; Liu, H.; Liu, Y. A distribution level wide area monitoring system for the electric power grid–FNET/GridEye. IEEE Access 2017, 5, 2329–2338. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, R.; Wu, N.; Chen, S.; Han, B. Will metaverse be nextg internet? vision, hype, and reality. IEEE network 2022, 36, 197–204. [CrossRef]

- Qu, Q.; Hatami, M.; Xu, R.; Nagothu, D.; Chen, Y.; Li, X.; Blasch, E.; Ardiles-Cruz, E.; Chen, G. The microverse: A task-oriented edge-scale metaverse. Future Internet 2024, 16, 60. [CrossRef]

- Chakshu, N.K.; Carson, J.; Sazonov, I.; Nithiarasu, P. A semi-active human digital twin model for detecting severity of carotid stenoses from head vibration—A coupled computational mechanics and computer vision method. International journal for numerical methods in biomedical engineering 2019, 35, e3180. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatami, M.; Qu, Q.; Chen, Y.; Kholidy, H.; Blasch, E.; Ardiles-Cruz, E. A survey of the real-time metaverse: Challenges and opportunities. Future Internet 2024, 16, 379. [CrossRef]

- Hatami, M.; Qu, Q.; Chen, Y.; Mohammadi, J.; Blasch, E.; Ardiles-Cruz, E. ANCHOR-Grid: Authenticating Smart Grid Digital Twins Using Real-World Anchors. Sensors 2025, 25, 2969. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagothu, D.; Xu, R.; Chen, Y.; Blasch, E.; Aved, A. Defakepro: Decentralized deepfake attacks detection using enf authentication. IT Professional 2022, 24, 46–52. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, T.; Takao, H.; Rapaka, S.; Fujimura, S.; Ioan Nita, C.; Uchiyama, Y.; Ohno, H.; Otani, K.; Dahmani, C.; Mihalef, V.; et al. Rupture risk of small unruptured intracranial aneurysms in Japanese adults. Stroke 2020, 51, 641–643. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barabási, A.L.; Gulbahce, N.; Loscalzo, J. Network medicine: a network-based approach to human disease. Nature reviews genetics 2011, 12, 56–68. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Chen, Y. Real-time elderly monitoring for senior safety by lightweight human action recognition. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 16th International Symposium on Medical Information and Communication Technology (ISMICT). IEEE, 2022, pp. 1–6.

- of Sciences, N.A. Factors that affect health-care utilization. In Health-Care Utilization as a Proxy in Disability Determination; National Academies Press (US), 2018.

- Shamir, A. Identity-based cryptosystems and signature schemes. In Proceedings of the Advances in Cryptology: Proceedings of CRYPTO 84 4. Springer, 1985, pp. 47–53.

- Hammi, B.; Fayad, A.; Khatoun, R.; Zeadally, S.; Begriche, Y. A lightweight ECC-based authentication scheme for Internet of Things (IoT). IEEE Systems Journal 2020, 14, 3440–3450. [CrossRef]

- Subashini, A.; Raju, P.K. Hybrid AES model with elliptic curve and ID based key generation for IOT in telemedicine. Measurement: Sensors 2023, 28, 100824. [CrossRef]

- Hajj-Ahmad, A.; Garg, R.; Wu, M. Instantaneous frequency estimation and localization for ENF signals. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of The 2012 Asia Pacific Signal and Information Processing Association Annual Summit and Conference, 2012, pp. 1–10.

- Menezes, A. Evaluation of security level of cryptography: The elliptic curve discrete logarithm problem (ECDLP). University of Waterloo 2001, 14, 1–24.

- Haakegaard, R.; Lang, J. The elliptic curve diffie-hellman (ecdh). Online at https://koclab.cs.ucsb.edu/teaching/ecc/project/2015Projects/ Haakegaard+ Lang.pdf 2015.

- Munir, A.; Kwon, J.; Lee, J.H.; Kong, J.; Blasch, E.; Aved, A.J.; Muhammad, K. FogSurv: A fog-assisted architecture for urban surveillance using artificial intelligence and data fusion. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 111938–111959. [CrossRef]

- El-Wajeh, Y.A.; Hatton, P.V.; Lee, N.J. Unreal Engine 5 and immersive surgical training: translating advances in gaming technology into extended-reality surgical simulation training programmes. British Journal of Surgery 2022, 109, 470–471. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Li, J.; Blasch, E.; Qu, Q. Future Outdoor Safety Monitoring: Integrating Human Activity Recognition with the Internet of Physical–Virtual Things. Applied Sciences 2025, 15, 3434. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Andrews, J.; Mu, H.; Vakil, A.; Ewing, R.; Blasch, E.; Li, J. Interpretable passive multi-modal sensor fusion for human identification and activity recognition. Sensors 2022, 22, 5787. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munir, A.; Blasch, E.; Kwon, J.; Kong, J.; Aved, A. Artificial intelligence and data fusion at the edge. IEEE Aerospace and Electronic Systems Magazine 2021, 36, 62–78. [CrossRef]

- Soni, D.; Makwana, A. A survey on mqtt: a protocol of internet of things (iot). In Proceedings of the International conference on telecommunication, power analysis and computing techniques (ICTPACT-2017), 2017, Vol. 20.

- Xu, R.; Chen, Y.; Blasch, E. Lightweight Blockchain for Internet of Things: Rationale and a Case Study. In Proceedings of the SPIE Spotlight Series. SPIE Bellingham, WA, USA, 2023.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).