Submitted:

17 July 2025

Posted:

18 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Atmospheric Rossby Waves

1.2. Oceanic Rossby Waves

1.2.1. The Indian Ocean

1.2.2. The Pacific Ocean

1.3. Conditions for Resonant Forcing

1.4. Resonant Forcing of Quasi-Stationary Rossby Waves

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data

2.2. In Search of a Unified Explanation of Resonant Forcing of Quasi-Stationary Rossby Waves

2.3. Resonant Forcing in Harmonic and Subharmonic Modes

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Rossby Waves in the Tropical Oceans

3.1.1. The Tropical Pacific

- The annual Rossby wave system

- The quadrennial wave system

- The 8-year period wave system

- Coupling of the wave systems

3.1.2. The Tropical Atlantic

- The annual wave systems

- The semi-annual wave systems

3.1.3. The Tropical Indian Ocean

- The semi-annual wave system

- The annual wave system

3.2. Quasi-Stationary Rossby Waves in the Tropopause

3.2.1. The Northern Hemisphere

- The fundamental wave

- Harmonics and subharmonics

3.2.2. The Southern Hemisphere

- The fundamental wave

- Harmonics and subharmonics

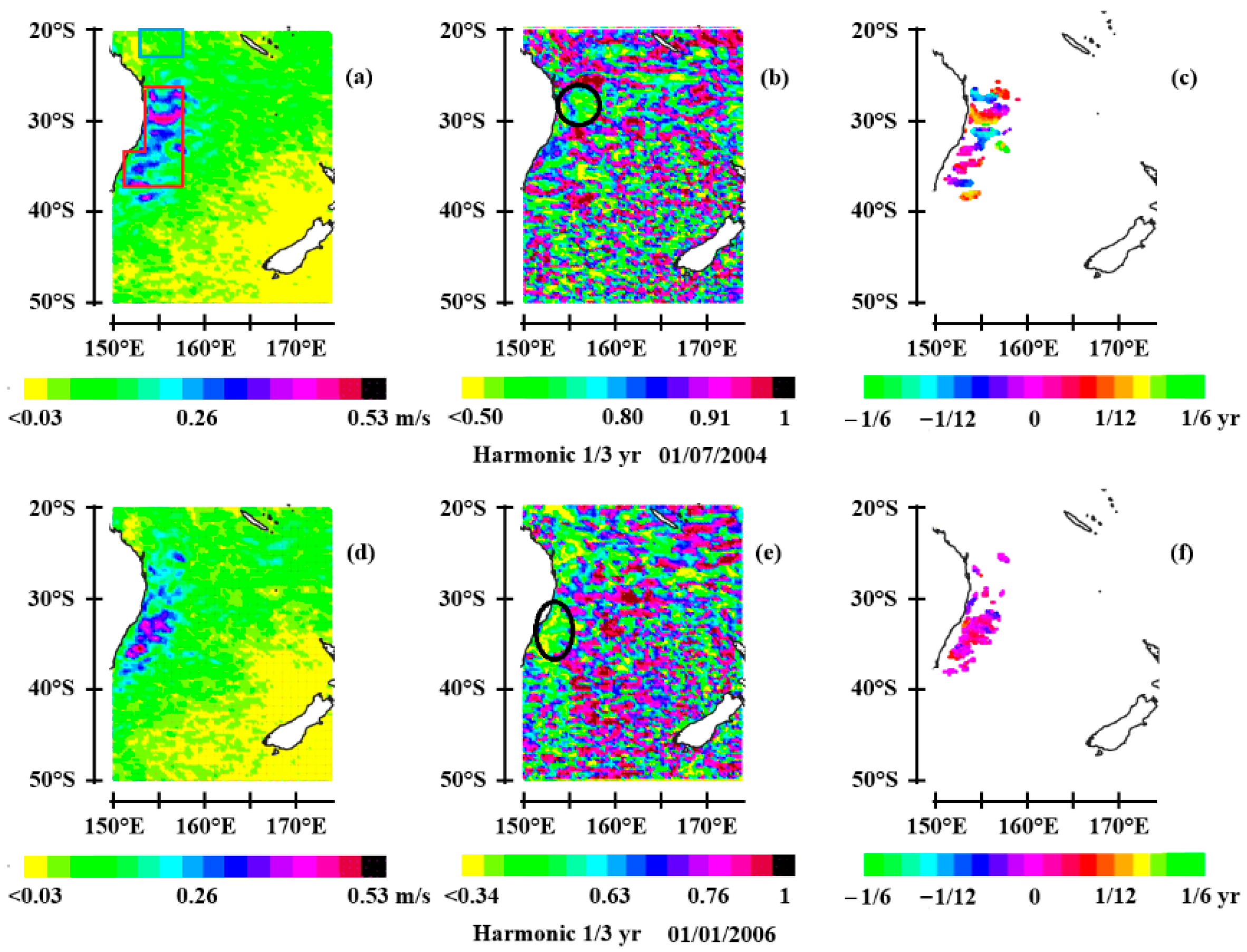

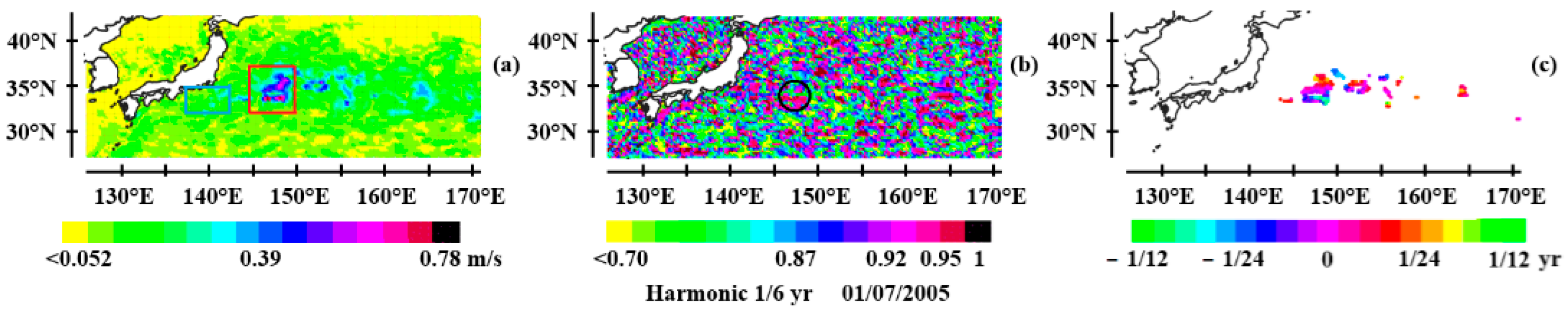

3.3. Oceanic Rossby Waves at Mid-Latitudes

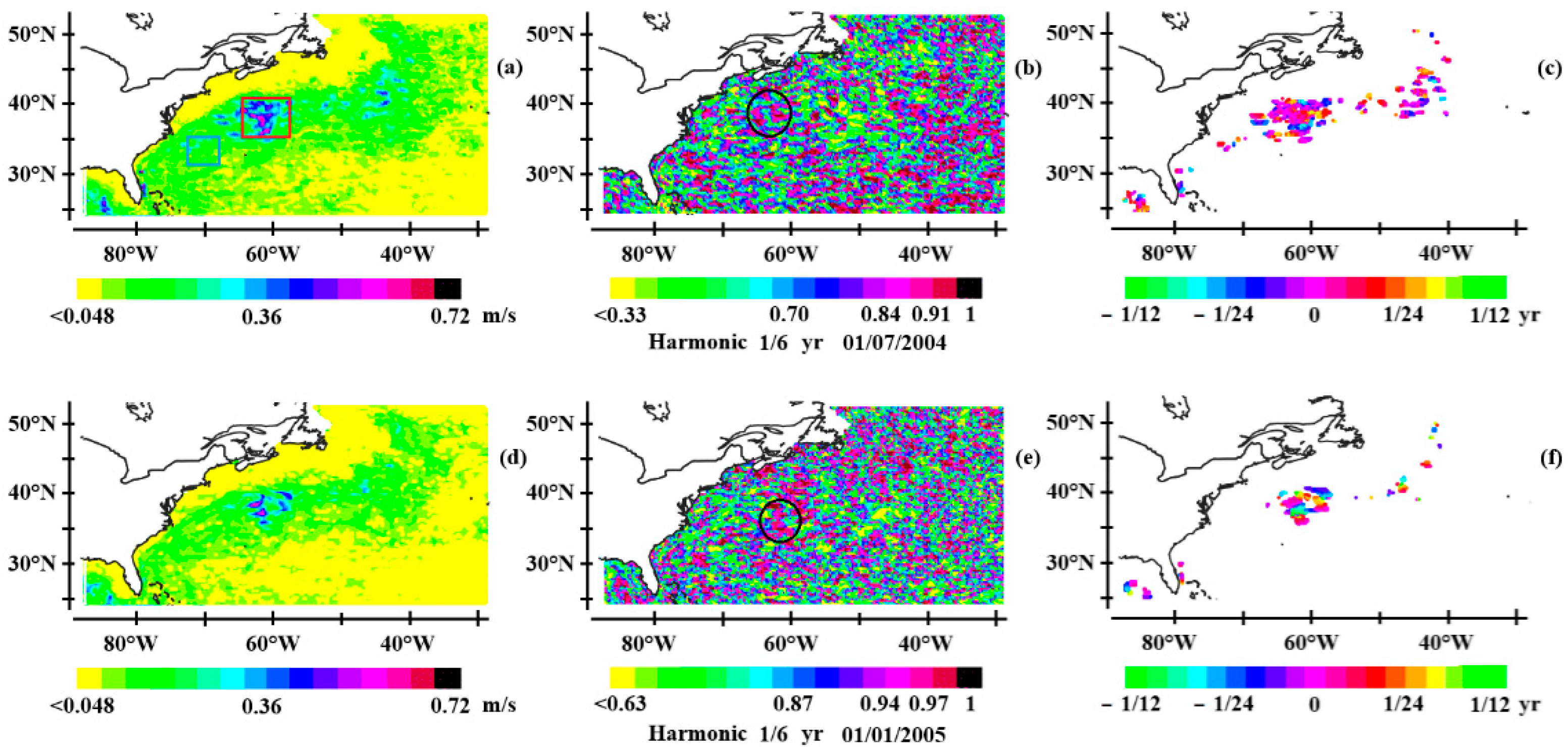

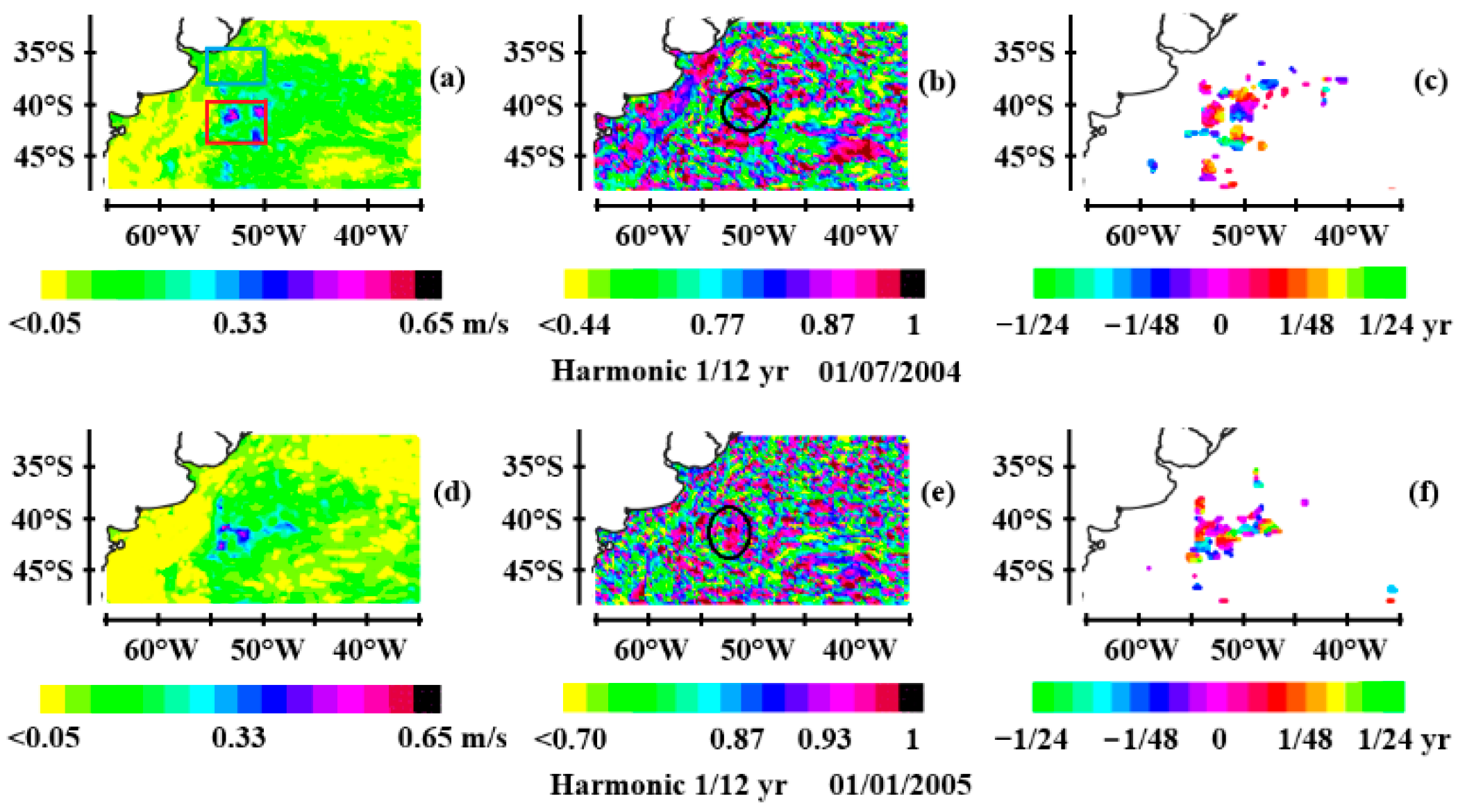

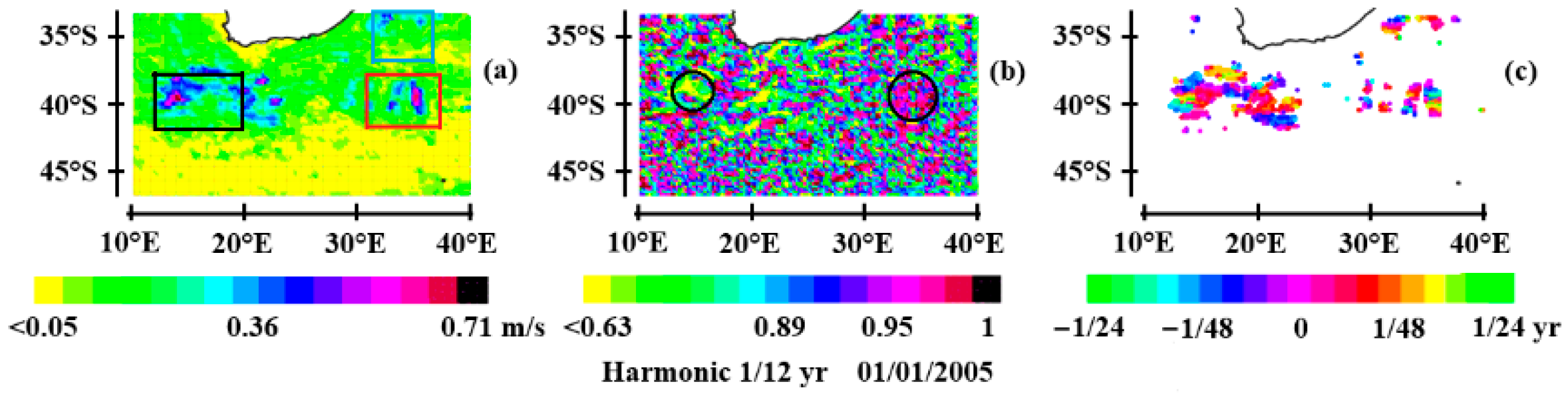

3.3.1. Observations of Rossby Waves at Mid-Latitudes

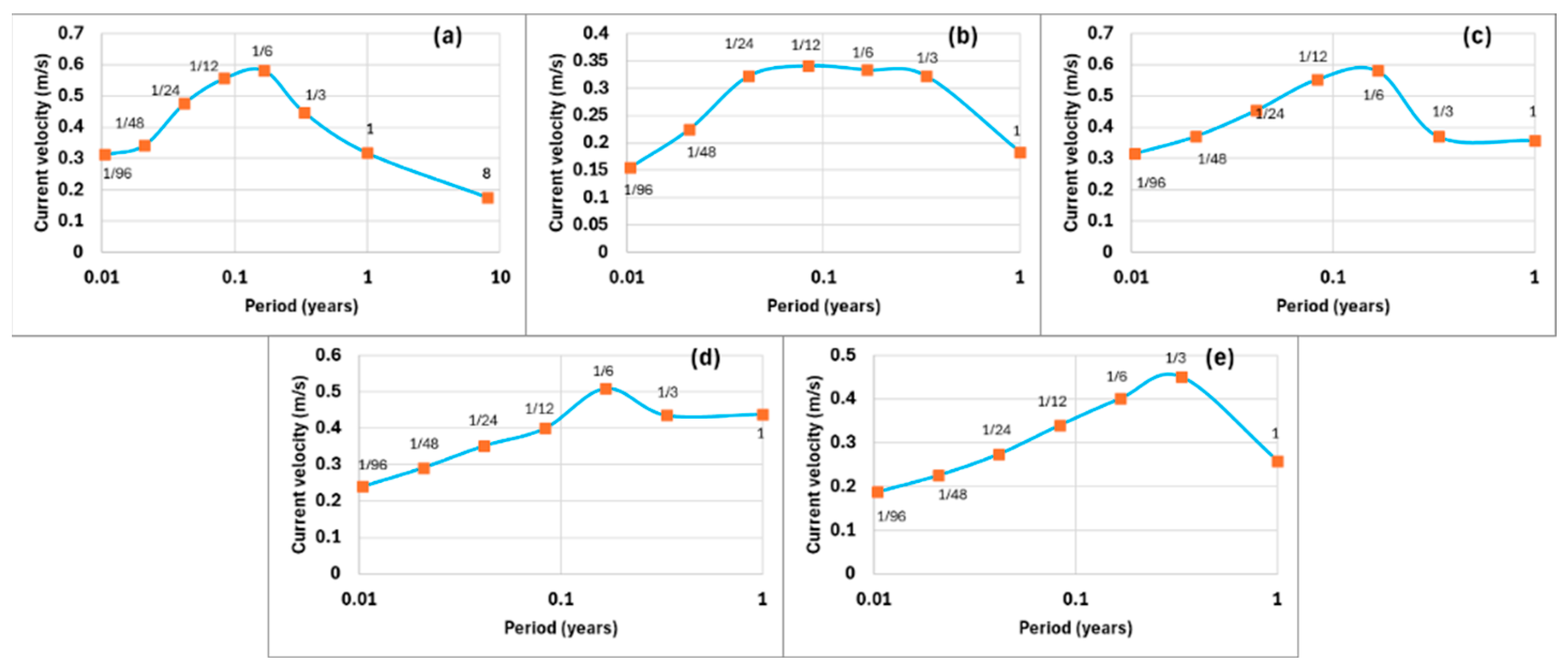

3.3.2. Amplification of the Modulated Current Velocity

3.3.3. Impact on Climate

3.3.4. Global Warming

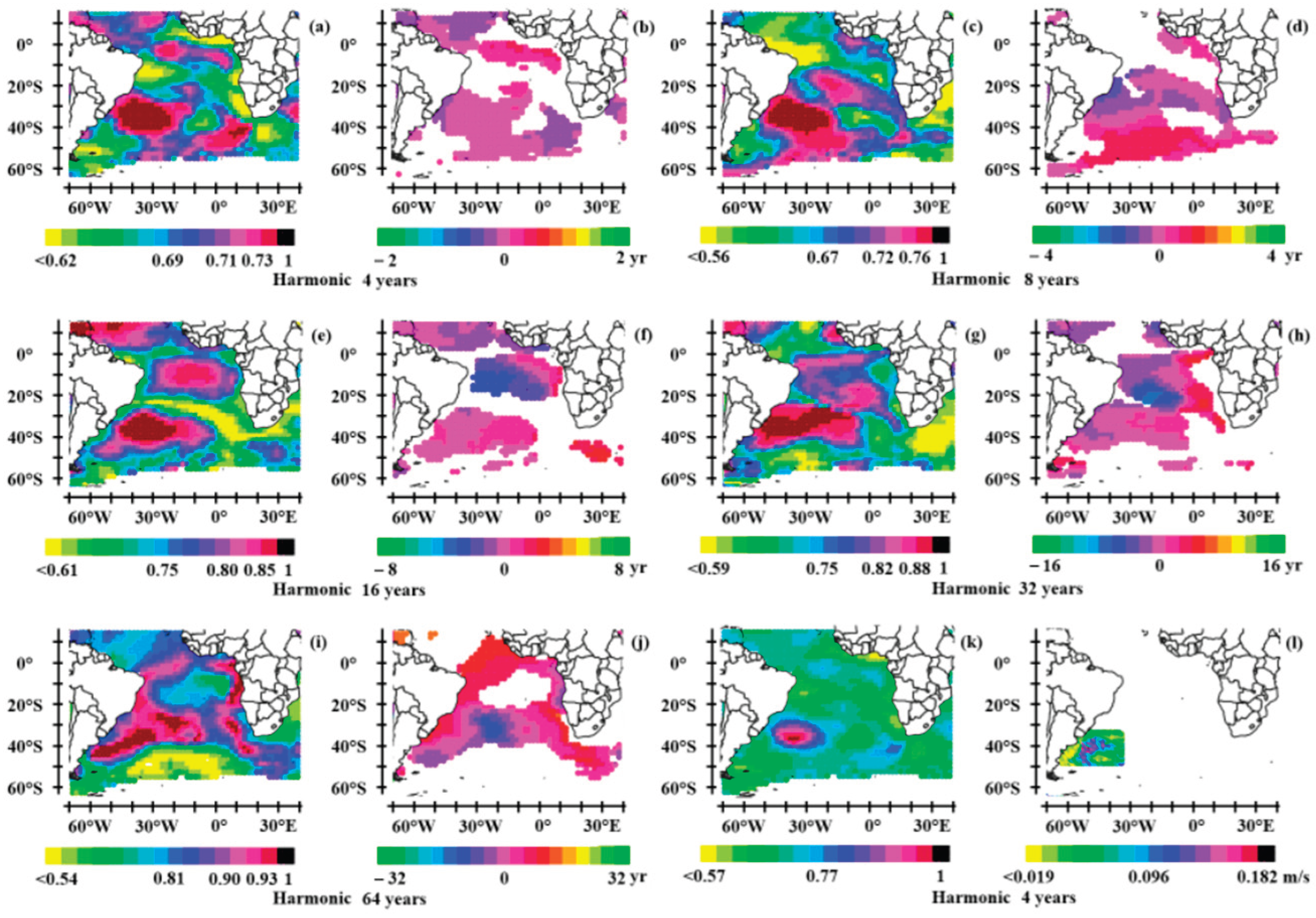

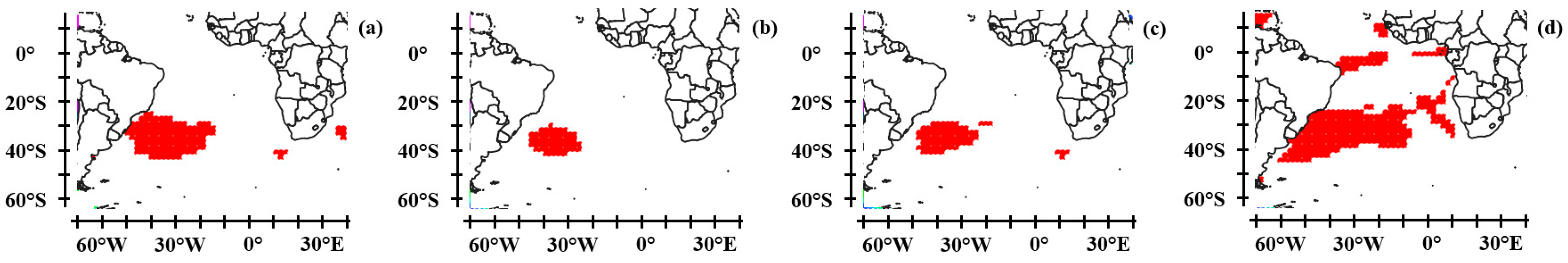

3.4. Gyral Rossby Waves (GRWs)

4. Conclusions

4.1. Rossby Waves in Tropical Oceans

4.2. Rossby Waves at the Tropopause

4.3. Oceanic Rossby Waves at Mid-Latitudes

- In the North and South Atlantic, the thermocline behaves as a resonant cavity with rigid boundaries at the edges of the western boundary currents, i.e. the Gulf Stream and the Brazil Current, traversed by first-baroclinic mode, first-meridional mode Rossby waves.

- In the Indian Ocean, the retroflection of the Agulhas Current south of the African continent causes resonance in two different ways west and east of the Cape of Good Hope: resonance of second-baroclinic mode Rossby waves in the first case, and first-baroclinic mode Rossby waves in the second.

- The resonant forcing of second-baroclinic mode Rossby waves is also observed in the East Australian Current as it flows along Australia. In the North Pacific, resonant forcing of first-baroclinic mode Rossby waves is observed along the Kuroshio, off the east coast of Japan.

4.4. Gyral Rossby Waves (GRWs)

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Madden, R. A. (1979), Observations of large-scale traveling Rossby waves, Rev. Geophys., 17(8), 1935–1949. [CrossRef]

- Madden, R. A. and P. R. Julian, 1972: Further evidence of global-scale 5-day pressure waves. J. Atmos. Sci., 29, 1464–1469.

- Madden, R. A. and P. R. Julian,1973: Reply. J. Atmos. Sci., 30, 935–940.

- Madden, R. A., 1978: Further evidence of traveling planetary waves. J. Atmos. Sci., 35, 1605–1618. [CrossRef]

- Ahlquist, J. E., 1982: Normal-mode global Rossby waves: Theory and observations. J. Atmos. Sci., 39, 193–202. [CrossRef]

- Hirota, I., and T. Hirooka, 1984: Normal mode Rossby waves observed in the upper stratosphere. Part I: First symmetric modes of zonal wavenumbers 1 and 2. J. Atmos. Sci., 41, 1253–1267. [CrossRef]

- Hirooka, T., and I. Hirota, 1985: Normal mode Rossby waves observed in the upper stratosphere. Part II: Second antisymmetric and symmetric modes of zonal wavenumbers 1 and 2. J. Atmos. Sci., 42, 536–548. [CrossRef]

- Hirooka, T., and I. Hirota, 1989: Further evidence of normal mode Rossby waves. Pure Appl. Geophys., 130, 277–289. [CrossRef]

- Hirooka, T., 2000: Normal Mode Rossby Waves as Revealed by UARS/ISAMS Observations. J. Atmos. Sci., 57, 1277–1285. [CrossRef]

- Maosheng He & Jeffrey M. Forbes, Rossby wave second harmonic generation observed in the middle atmosphere, Nature Communications (2022) 13:7544. [CrossRef]

- S. Mubashshir Ali, Matthias Röthlisberger, Tess Parker, Kai Kornhuber, and Olivia Martius, Recurrent Rossby waves during Southeast Australian heatwaves and links to quasi-resonant amplification and atmospheric blocks, 2022, Weather and Climate Dynamics. [CrossRef]

- Han W., J. P. McCreary, Y. Masumoto, J. Vialard, and B. Duncan, 2011: Basin resonances in the equatorial Indian Ocean. J. Phys. Oceanogr., 41, 1252–1270. [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.,W. Han, D.X. Wang, W.Q. Wang, Q. Xie, J. Chen, and G. X. Chen, 2018: Features of the equatorial intermediate current associated with basin resonance in the Indian Ocean. J. Phys. Oceanogr., 48, 1333–1347. [CrossRef]

- Huang et al., Baroclinic Characteristics and Energetics of Annual Rossby Waves in the Southern Tropical Indian Ocean, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Gent, P., K. O’Neill, and M. Cane, 1983: A model of the semi-annual oscillation in the equatorial Indian Ocean. J. Phys. Oceanogr., 13, 2148–2160. [CrossRef]

- Reverdin, G., 1987: The upper equatorial Indian Ocean: The climatological seasonal cycle. J. Phys. Oceanogr., 17, 903–927. [CrossRef]

- Han, J.P. McCreary, D. L. T. Anderson, and A. J. Mariano, 1999: Dynamics of the eastward surface jets in the equatorial Indian Ocean. J. Phys. Oceanogr., 29, 2191–2209. [CrossRef]

- YUAN D., HAN W., Roles of Equatorial Waves and Western Boundary Reflection in the Seasonal Circulation of the Equatorial Indian Ocean, 2005, J. Phys. Oceanogr.,36, 930-944. [CrossRef]

- Jensen, T. G., 1993: Equatorial variability and resonance in a wind-driven Indian Ocean model. J. Geophys. Res., 98, 22 533–22 552. [CrossRef]

- Nagura, M., and M. J. McPhaden (2012), The dynamics of wind-driven intraseasonal variability in the equatorial Indian Ocean, J. Geophys. Res., 117, C02001. [CrossRef]

- McCreary, J.P., Shetye, S.R. (2023). Equatorial Ocean: Periodic Forcing. In: Observations and Dynamics of Circulations in the North Indian Ocean. Atmosphere, Earth, Ocean & Space. Springer, Singapore. [CrossRef]

- White, W. B., The resonant response of interannual baroclinic Rossby waves to wind forcing in the eastern mid-latitude North Pacific, J. Phys. Oceanog., 15, 403–415, 1985. [CrossRef]

- White, W.B., S. Pazan and B. Li, 1985: Processes of short-term climatic variability in the baroclinic structure of the interior Western Tropical North Pacific. J. Phys. Oceanogr., 15, 386-402. [CrossRef]

- Graham, N., T.P. Barnett, V.G. Panchang, O.M. Smedsted, 1.1. O'Brien, and R.M. Chervin, 1989: The response of a linear model of the tropical Pacific to surface wind from the NCAR general circulation model. J. Phys. Oeeanogr., 19, 1222-1243. [CrossRef]

- Jacob, R., C. Schafer, I. Foster, M. Tobis, and J. Anderson (2001), Computational design and performance of the Fast Ocean-Atmosphere Model, version one, in Proceedings of the 2001 International Conference on Computational Science, edited by V. N. Alexandrov, J. J. Dongarra, and C. J. K. Tan, pp. 175–184, Springer, New York.

- White, W. B., and Z. Liu (2008), Resonant excitation of the quasi-decadal oscillation by the 11-year signal in the Sun’s irradiance, J. Geophys. Res., 113, C01002. [CrossRef]

- PRIMEAU F., Long Rossby Wave Basin-Crossing Time and the Resonance of Low-Frequency Basin Modes, 2002, J. Phys. Oceanogr., 32, 2652–2665. [CrossRef]

- Skákala, J., & Bruun, J. T. (2018). A mechanism for Pacific interdecadal resonances. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 123, 6549–6561. [CrossRef]

- Gent R., Forced standing equatorial ocean wave modes, 1981, Journal of Marine Research.

- Cane, M. A. and E. S. Sarachik. 1976. Forced baroclinic ocean motions. I. The linear equatorial unbounded case. J. Mar. Res., 34, 629-665.

- CESSI P. AND F. PRIMEAU, Dissipative Selection of Low-Frequency Modes in a Reduced-Gravity Basin, 2001, J. Phys. Oceanogr., 31, 127–137. [CrossRef]

- Cessi P., Louazel S., Decadal Oceanic Response to Stochastic Wind Forcing, 2001, J. Phys. Oceanogr., 31, 3020–3029. [CrossRef]

- Capotondi, A., M.A. Alexander, and C. Deser, 2003: Why are there Rossby wave maxima in the Pacific at 108 S and 138 N? J. Phys. Oceanogr., 33, 1549–1563. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, G. C., 2011: Deep signatures of southern tropical Indian Ocean annual Rossby waves. J. Phys. Oceanogr., 41, 1958-1964. [CrossRef]

- Pinault, J.-L. Resonant Forcing by Solar Declination of Rossby Waves at the Tropopause and Implications in Extreme Events, Precipitation, and Heat Waves—Part 1: Theory. Atmosphere 2024, 15(5), 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinault, J.-L. Resonant Forcing by Solar Declination of Rossby Waves at the Tropopause and Implications in Extreme Precipitation Events and Heat Waves—Part 2: Case Studies, Projections in the Context of Climate Change. Atmosphere 2024, 15(10), 1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonjean, F., and G. S. E. Lagerloef. 2002. Diagnostic model and analysis of the surface currents in the tropical Pacific Ocean, American Meteorological Society, 32. [CrossRef]

- ESR; Dohan, Kathleen. 2022. Ocean Surface Current Analyses Real-time (OSCAR) Surface Currents - Final 0.25 Degree (Version 2.0). Ver. 2.0. PO.DAAC, CA, USA. [CrossRef]

- Kanamitsu, M.; Ebisuzaki, W.; Woollen, J.; Yang, S.-K.; Hnilo, J.J.; Fiorino, M.; Potter, G.L. NCEP-DOE AMIP-II Reanalysis (R-2). Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2002, 83, 1631–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.M.; Banzon, V.F.; Vose, R.S.; Thorne, P.W.; Boyer, T.; Menne, M.J.; Zhang, H.-M.; Lawrimore, J.H.; Huang, B.; Chepurin, G. Extended Reconstructed Sea Surface Temperatures Version 5 (ERSSTv5): Upgrades, Validations, and Intercomparisons. J. Clim. 2017, 30, 8179–8205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NOAA Extended Reconstructed SST V5. A global Monthly SST Analysis from 1854 to the Present Derived from ICOADS Data with Missing Data Filled in by Statistical Methods. Available online: http://www.esrl.noaa.gov/psd/data/gridded/data.noaa.ersst.v5.html (accessed on 7 June 2025).

- GILL A.E. (1982) Atmosphere–Ocean Dynamics, International Geophysics Series,30, Academic Press, 662pp.

- Pinault J.-L. Modulated Response of Subtropical Gyres: Positive Feedback Loop, Subharmonic Modes, Resonant Solar and Orbital Forcing, J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2018, 6, 107. [CrossRef]

- Pinault, J.-L. Resonantly Forced Baroclinic Waves in the Oceans: Subharmonic Modes, J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2018, 6, 78; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinault, J.-L. The Anticipation of the ENSO: What Resonantly Forced Baroclinic Waves Can Teach Us (Part II). J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2018, 6, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinault J.-L. Anticipation of ENSO: what teach us the resonantly forced baroclinic waves, 2016, Geophysical & Astrophysical Fluid Dynamics, 110:6, 518-528. [CrossRef]

- Torrence, C.; Compo, G.P. A practical guide for wavelet analysis. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 1998, 79, 61–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinault, J.-L. Long Wave Resonance in Tropical Oceans and Implications on Climate: The Pacific Ocean. Pure Appl. Go-phys., 2015, Springer International Publishing.

- Cravatte, S.; Kessler, W.S.; Marin, F. Intermediate Zonal Jets in the Tropical Pacific Ocean Observed by Argo Floats. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 2012, 42, 1475–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinault J.-L. Long Wave Resonance in Tropical Oceans and Implications on Climate: the Atlantic Ocean, 2013, Pure Appl. Geophys. 170 (2013), 1913–1930. [CrossRef]

- Pinault J.-L. Resonance of baroclinic waves in the tropical oceans: The Indian Ocean and the far western Pacific, Dynamics of Atmospheres and Oceans, 89, 2020, 101119. [CrossRef]

- Pinault J-L, Global warming and rainfall oscillation in the 5–10 yr band in Western Europe and Eastern North America, 2012, Climatic Change. [CrossRef]

- Pinault J-L, Regions Subject to Rainfall Oscillation in the 5–10 Year Band, Climate 2018, 6, 2. [CrossRef]

- Pinault, J.-L. The Moist Adiabat, Key of the Climate Response to Anthropogenic Forcing, Climate 2020, 8, 45. [CrossRef]

- Pinault J.-L. The Milankovitch Theory Revisited to Explain the Mid-Pleistocene and Early Quaternary Transitions, Atmosphere 2025, 16, 702. [CrossRef]

- Pinault, J.-L. Weakening of the Geostrophic Component of the Gulf Stream: A Positive Feedback Loop on the Melting of the Arctic Ice Sheet. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).