Submitted:

17 July 2025

Posted:

18 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

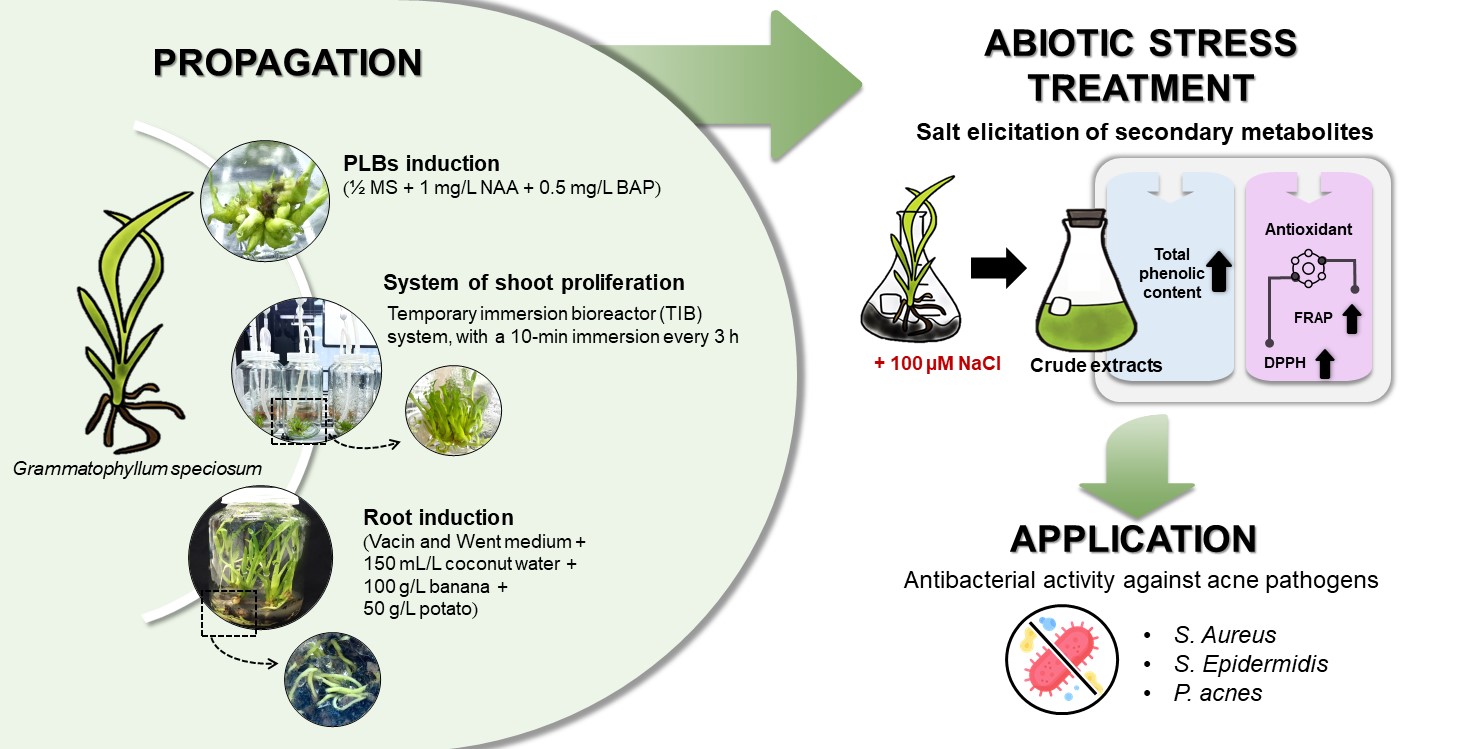

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

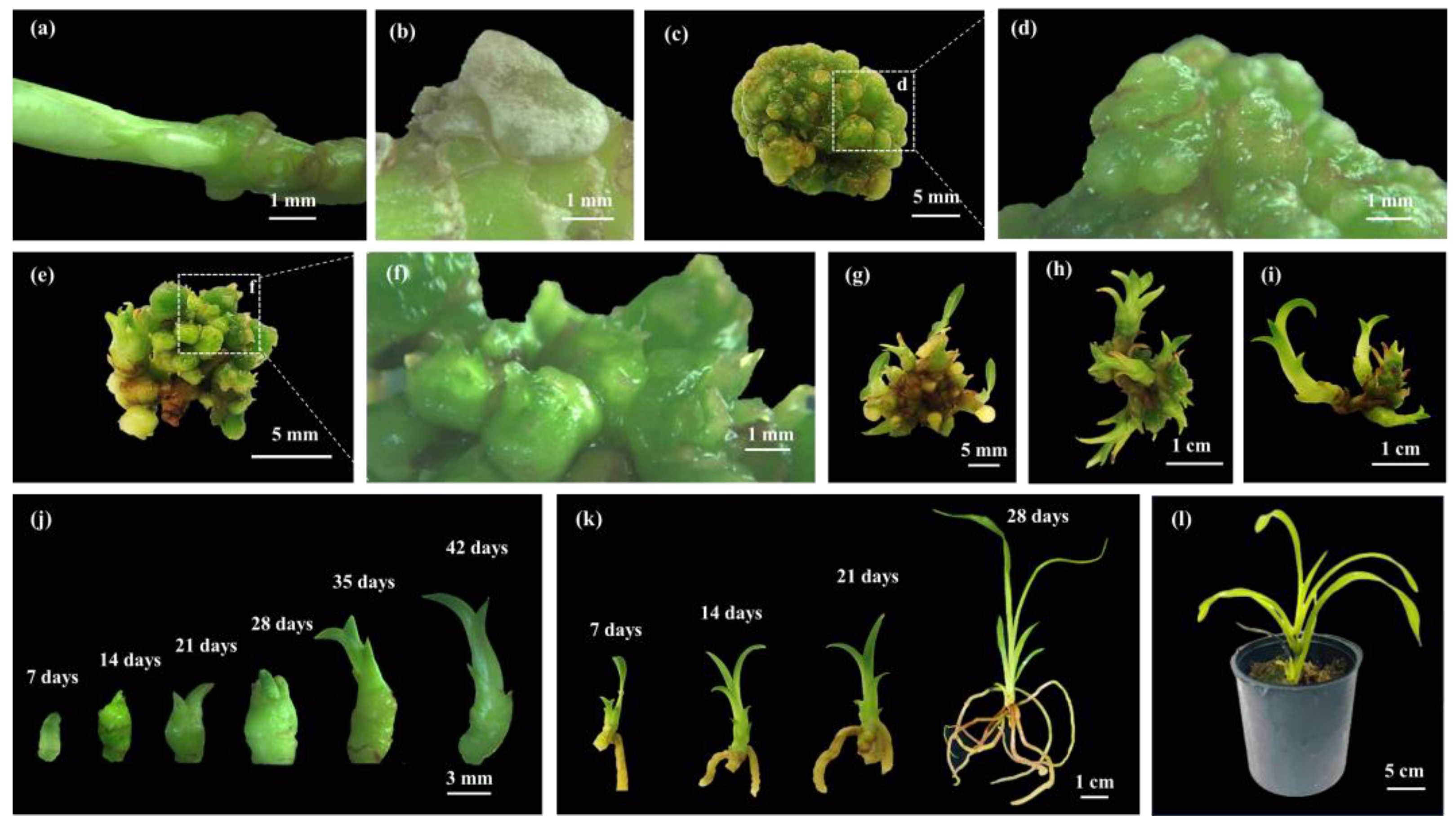

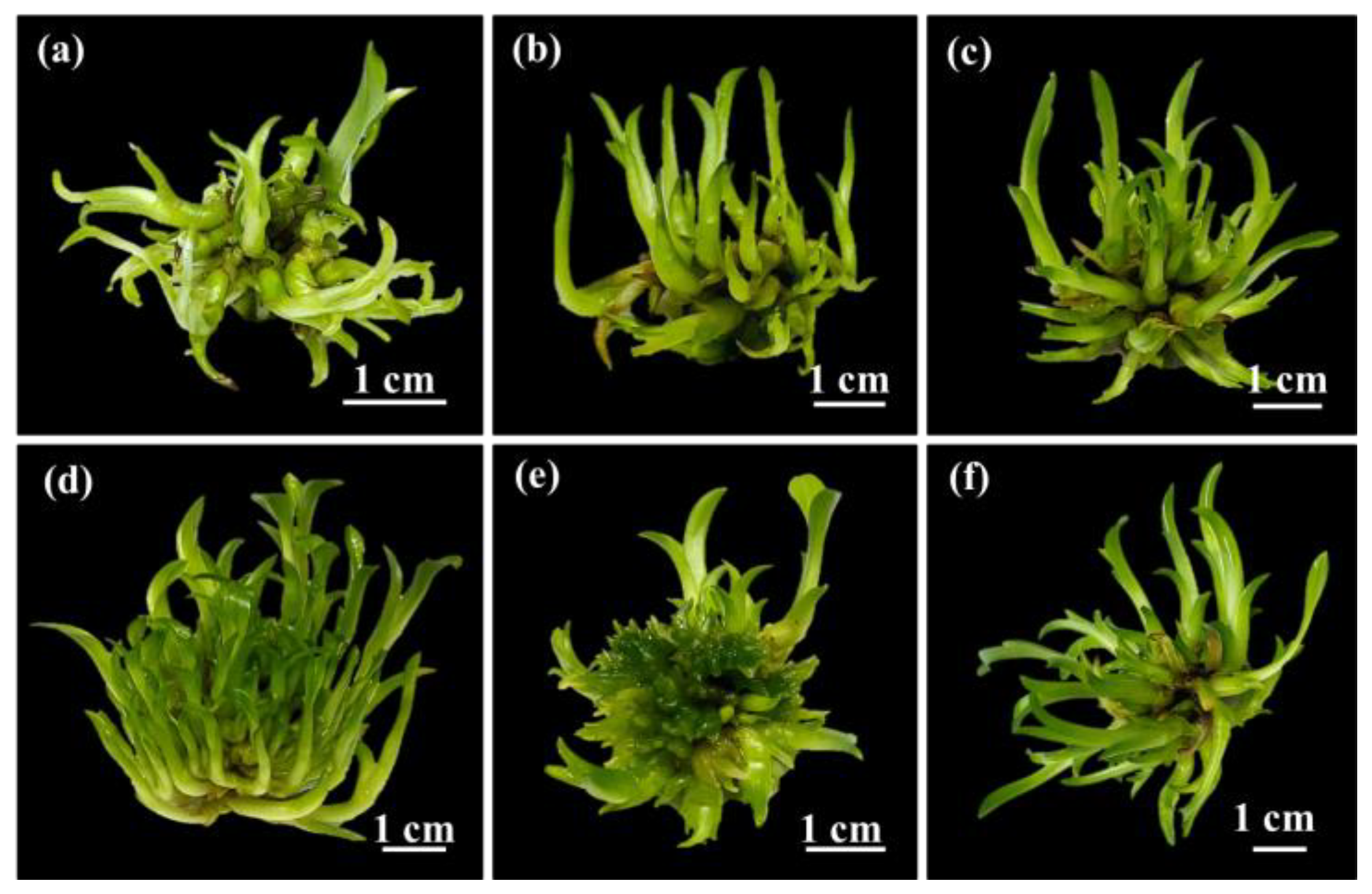

2.1. Induction of Protocorm-like Bodies

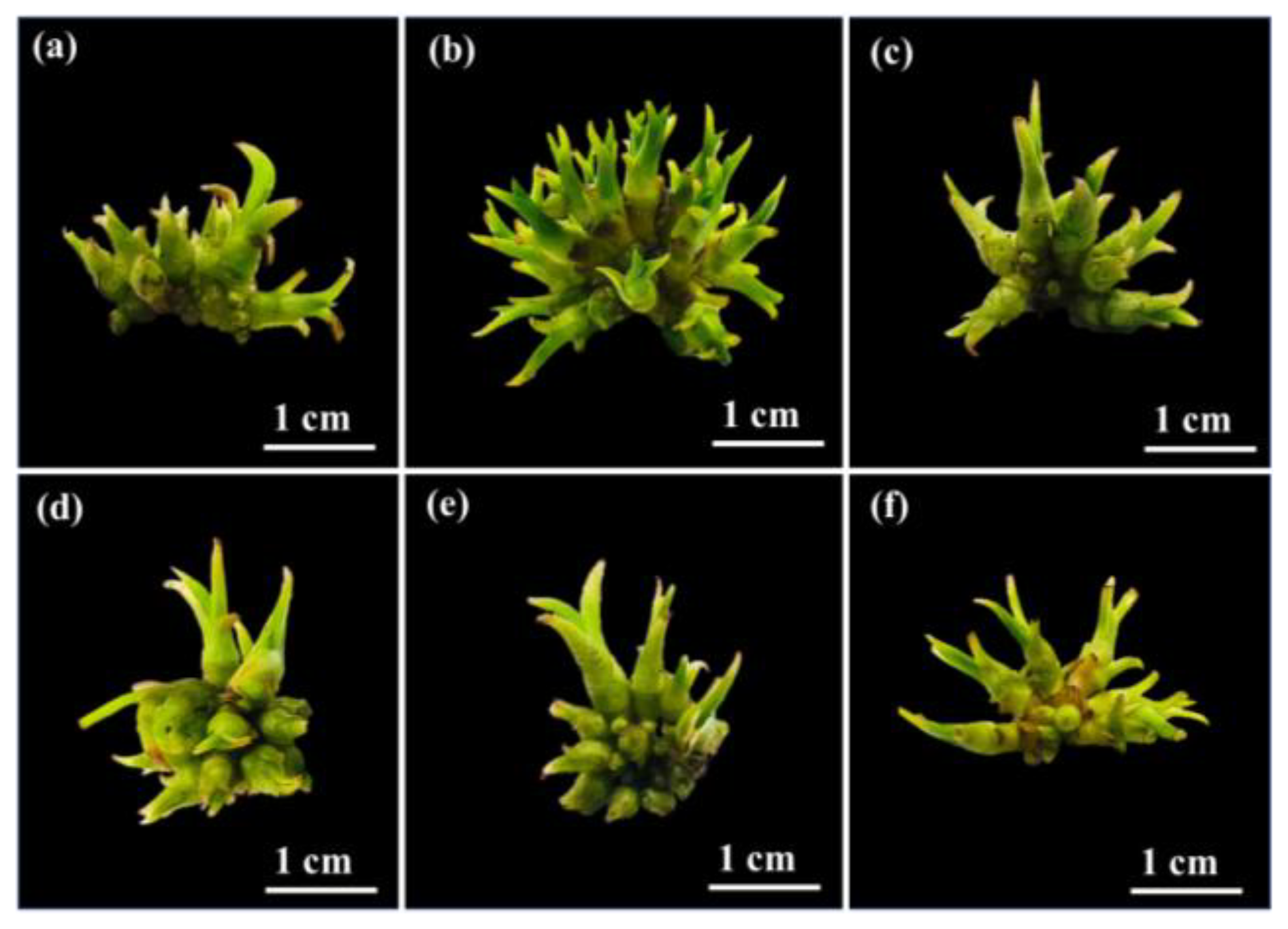

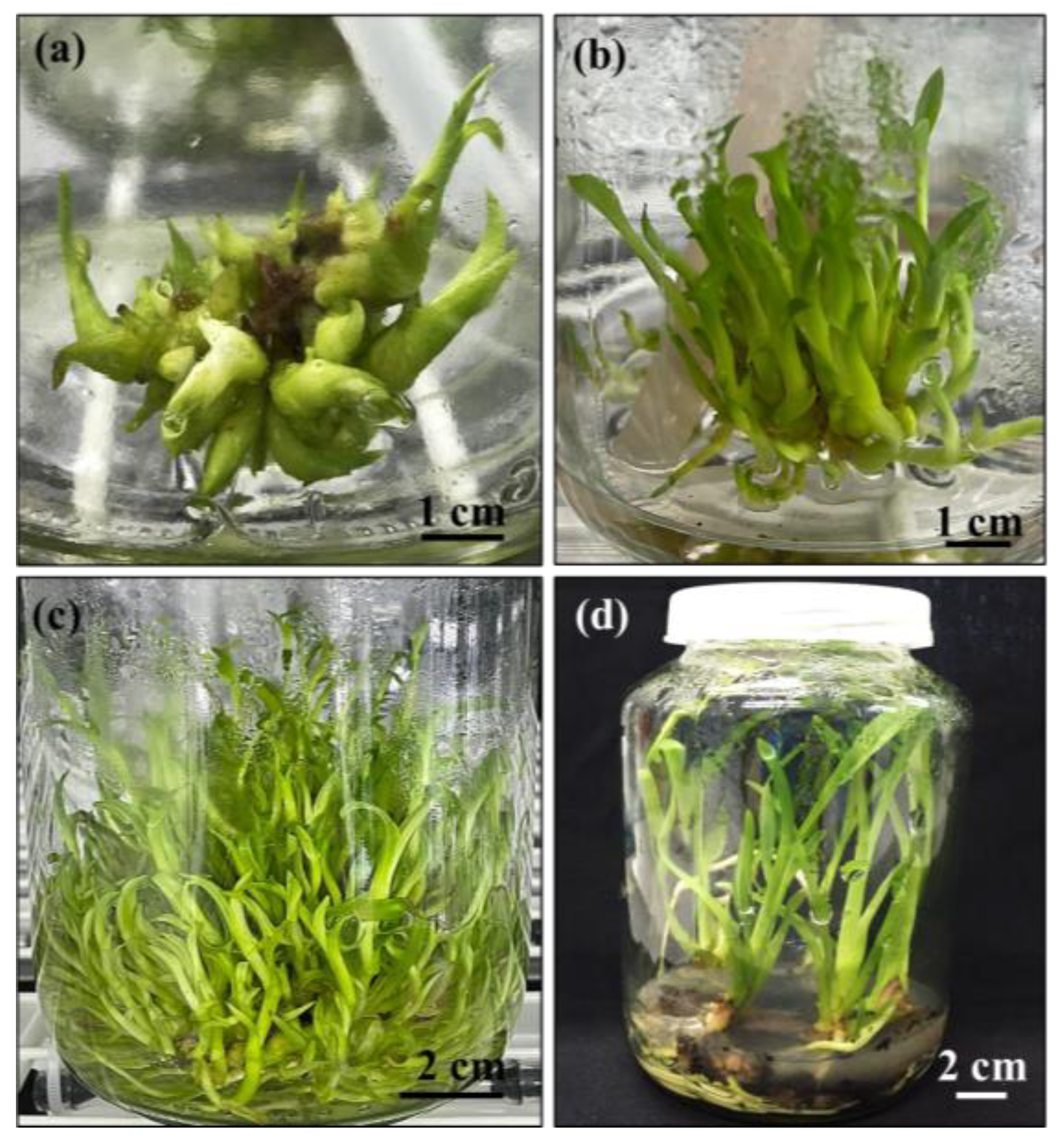

2.2. Effect of Different Immersion Times and Frequencies on Shoot Multiplication

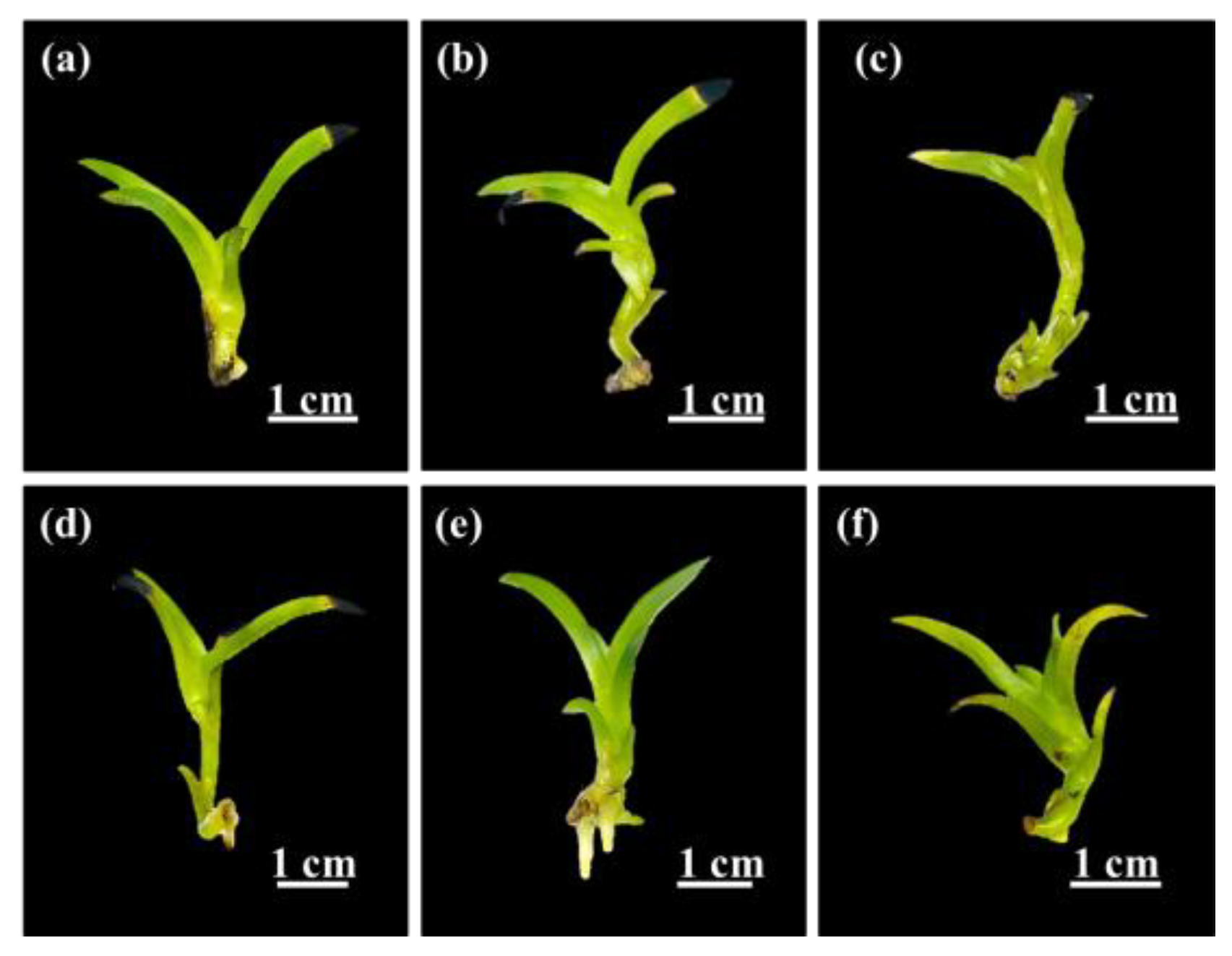

2.3. Root Induction

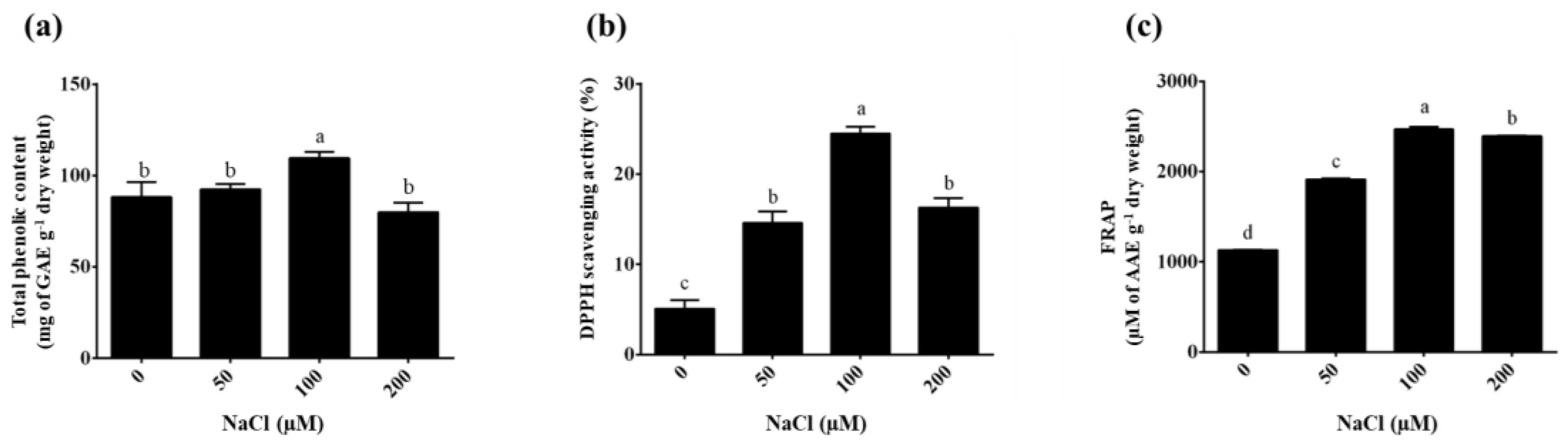

2.4. Effect of NaCl Stress on Total Phenolic Content

2.5. Antioxidant Activity

2.6. Antibacterial Activity

3. Materials and Methods

Plant Materials and Induction of Protocorm-like Bodies

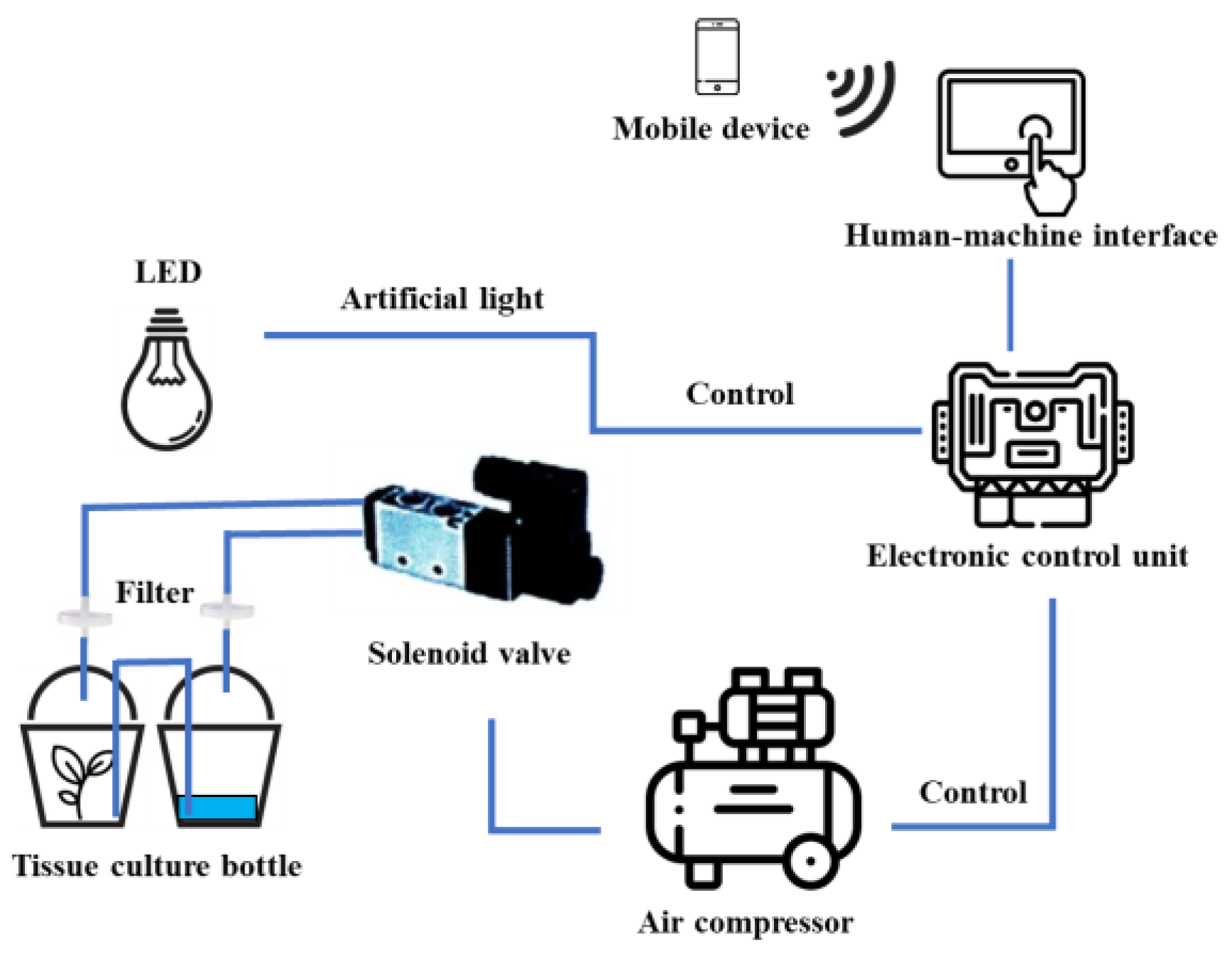

Optimization of High Efficiency Shoot Multiplication

Root Induction

Morphological Evaluation

Sodium Chloride Stress Treatments

Preparation of Crude Extract

Quantification of Total Phenolic Content

DPPH Radical Scavenging Assay

Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power Assay

Antibacterial Activity

Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yam, T.W.; Chua, J.; Tay, F.; Ang, P. Conservation of the Native Orchids Through Seedling Culture and Reintroduction—A Singapore Experience. Bot. Rev. 2010, 76, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teoh, E.S. Medicinal orchids of Asia; Springer, Switzerland: 2016.

- Chowjarean, V.; Sadabpod, K.; Mejía-Aranguré, J. Antiproliferative Effect of Grammatophyllum speciosum Ethanolic Extract and Its Bioactive Compound on Human Breast Cancer Cells. Sci. World J. 2021, 2021, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yingchutrakul, Y.; Sittisaree, W.; Mahatnirunkul, T.; Chomtong, T.; Tulyananda, T.; Krobthong, S. Cosmeceutical Potentials of Grammatophyllum speciosum Extracts: Anti-Inflammations and Anti-Collagenase Activities with Phytochemical Profile Analysis Using an Untargeted Metabolomics Approach. Cosmetics 2021, 8, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowjarean V, Phiboonchaiyanan PP, Harikarnpakdee S. Skin brightening efficacy of grammatophyllum speciosum: a prospective, split-face, randomized placebo-controlled study. Sustainability [Internet]. 2022; 14(24).

- Etienne, H.; Berthouly, M. Temporary immersion systems in plant micropropagation. Plant Cell, Tissue Organ Cult. (PCTOC) 2002, 69, 215–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathore J, Rathore V, Shekhawat N, Singh R, Liler G, Phulwaria M, et al. Micropropagation of woody plants. Plant biotechnology and molecular markers: Springer; 2004. p. 195-205.

- Espinosa-Leal, C.A.; Puente-Garza, C.A.; García-Lara, S. In vitro plant tissue culture: means for production of biological active compounds. Planta 2018, 248, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esyanti, R.R.; Adhitama, N.; Manurung, R. Efficiency Evaluation of Vanda Tricolor Growth in Temporary Immerse System Bioreactor and Thin Layer Culture System. J. Adv. Agric. Technol. 2016, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvard D, Cote F, Teisson C. Comparison of methods of liquid medium culture for banana micropropagation: Effects of temporary immersion of explants. Plant cell, tissue and organ culture. 1993;32:55-60.

- Lorenzo, J.C.; Ojeda, E.; Espinosa, A.; Borroto, C. Field performance of temporary immersion bioreactor-derived sugarcane plants. Vitr. Cell. Dev. Biol. - Plant 2001, 37, 803–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis COD, Silva ABD, Landgraf PRC, Batista JA, Jacome GAR. Bioreactor in the micropropagation of ornamental pineapple. Ornamental Horticulture. 2018;24:182-7.

- Bello-Bello, J.J.; Schettino-Salomón, S.; Ortega-Espinoza, J.; Spinoso-Castillo, J.L. A temporary immersion system for mass micropropagation of pitahaya (Hylocereus undatus). 3 Biotech 2021, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gautam, S.; Solis-Gracia, N.; Teale, M.K.; Mandadi, K.; da Silva, J.A.; Vales, M.I. Development of an in vitro Microtuberization and Temporary Immersion Bioreactor System to Evaluate Heat Stress Tolerance in Potatoes (Solanum tuberosum L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Carlo, A.; Tarraf, W.; Lambardi, M.; Benelli, C. Temporary Immersion System for Production of Biomass and Bioactive Compounds from Medicinal Plants. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rout, G.; Samantaray, S.; Das, P. In vitro manipulation and propagation of medicinal plants. Biotechnol. Adv. 2000, 18, 91–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, K.-C.; Dedicova, B.; Johansson, S.; Lelu-Walter, M.-A.; Egertsdotter, U. Temporary immersion bioreactor system for propagation by somatic embryogenesis of hybrid larch (Larix × eurolepis Henry). Biotechnol. Rep. 2021, 32, e00684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farahani F, Majd A. Comparison of liquid culture methods and effect of temporary immersion bioreactor on growth and multiplication of banana (Musa, cv. Dwarf Cavendish). African Journal of Biotechnology. 2012;11(33):8302-8.

- Ahmadian, M.; Babaei, A.; Shokri, S.; Hessami, S. Micropropagation of carnation ( Dianthus caryophyllus L. ) in liquid medium by temporary immersion bioreactor in comparison with solid culture. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 2017, 15, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vendrame, W.A.; Xu, J.; Beleski, D.G. Micropropagation of Brassavola nodosa (L.) Lindl. using SETIS™ bioreactor. Plant Cell, Tissue Organ Cult. (PCTOC) 2023, 153, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritsche, Y.; Deola, F.; da Silva, D.A.; Holderbaum, D.F.; Guerra, M.P. Cattleya tigrina (Orchidaceae) in vitro regeneration: Main factors for optimal protocorm-like body induction and multiplication, plantlet regeneration, and cytogenetic stability. South Afr. J. Bot. 2022, 149, 96–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.-Y.; Murthy, H.N.; Moh, S.H.; Cui, Y.-Y.; Lee, E.-J.; Paek, K.-Y. Production of biomass and bioactive compounds in protocorm cultures of Dendrobium candidum Wall ex Lindl. using balloon type bubble bioreactors. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2014, 53, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang B, Niu Z, Zhou A, Zhang D, Xue Q, Liu W, et al. Micropropagation of Dendrobium nobile Lindl. plantlets by temporary immersion bioreactor. Journal of Biobased Materials and Bioenergy. 2019;13(3):395-400.

- Kang F, Hsu S, Shen R. Virus elimination through meristem culture and rapid clonal propagation by temporary immersion system in Phalaenopsis. Journal of the Taiwan Society for Horticultural Science. 2011;57(3):207-18.

- Spinoso-Castillo, J.L.; Chavez-Santoscoy, R.A.; Bogdanchikova, N.; Pérez-Sato, J.A.; Morales-Ramos, V.; Bello-Bello, J.J. Antimicrobial and hormetic effects of silver nanoparticles on in vitro regeneration of vanilla (Vanilla planifolia Jacks. ex Andrews) using a temporary immersion system. Plant Cell, Tissue Organ Cult. (PCTOC) 2017, 129, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obchant, T. Orchids of Thailand. Baanlaesuan. 2003.

- Nitcha, L. Academic documents "Grammatophyllum speciosum". 2016.

- Samala, S.; Te-Chato, S.; Yenchon, S.; Thammasiri, K. Protocorm-like body proliferation of Grammatophyllum speciosum through asymbiotic seed germination. ScienceAsia 2014, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.-H.; Liu, Y.-B.; Zhang, X.-S. Auxin–Cytokinin Interaction Regulates Meristem Development. Mol. Plant 2011, 4, 616–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangena, P. Benzyl adenine in plant tissue culture-succinct analysis of the overall influence in soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merrill.] seed and shoot culture establishment. Journal of Biotech Research. 2020;11:23-34.

- Moubayidin, L.; Di Mambro, R.; Sabatini, S. Cytokinin–auxin crosstalk. Trends Plant Sci. 2009, 14, 557–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madhulatha, P.; Anbalagan, M.; Jayachandran, S.; Sakthivel, N. Influence of Liquid Pulse Treatment with Growth Regulators on in vitro Propagation of Banana (Musa spp. AAA). Plant Cell, Tissue Organ Cult. (PCTOC) 2004, 76, 189–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari N, Othman RY, Khalid N. Effect of benzylaminopurine (BAP) pulsing on in vitro shoot multiplication of Musa acuminata (banana) cv. Berangan. African Journal of Biotechnology. 2011;10:2446-50.

- Rahman, M. In vitro Response and Shoot Multiplication of Banana with BAP and NAA. Asian J. Plant Sci. 2004, 3, 406–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekmekçigil, M.; Bayraktar, M.; Akkuş, Ö.; Gürel, A. High-frequency protocorm-like bodies and shoot regeneration through a combination of thin cell layer and RITA® temporary immersion bioreactor in Cattleya forbesii Lindl. Plant Cell, Tissue Organ Cult. (PCTOC) 2018, 136, 451–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murashige, T.; Skoog, F. A Revised Medium for Rapid Growth and Bioassays with Tobacco Tissue Cultures. Physiol. Plant. 1962, 15, 473–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vacin, E.F.; Went, F.W. Some pH Changes in Nutrient Solutions. Bot. Gaz. 1949, 110, 605–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelberg, J.W.; Delgado, M.P.; Tomkins, J.T. Spent medium analysis for liquid culture micropropagation of Hemerocallis on Murashige and Skoog medium. Vitr. Cell. Dev. Biol. - Plant 2009, 46, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salsabila, S.N.; Fatimah, K.; Noorhazira, S.; Halimatun, T.S.T.A.B.; Aurifullah, M.; Suhana, Z. Effect of Coconut Water and Peptone in Micropropagation of Phalaenopsis amabilis (L.) Blume Orchid.CONFERENCE NAME, LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, COUNTRYDATE OF CONFERENCE; p. 012002.

- De Stefano, D.; Costa, B.N.S.; Downing, J.; Fallahi, E.; Khoddamzadeh, A.A. In-Vitro Micropropagation and Acclimatization of an Endangered Native Orchid Using Organic Supplements. Am. J. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 380–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowjarean V, Sucontphunt A, Vchirawongkwin S, Charoonratana T, Songsak T, Harikarnpakdee S, et al. Validated RP-HPLC method for quantification of gastrodin in ethanolic extract from the pseudobulbs of grammatophyllum speciosum blume. Malays. J. Anal. Sci. 2018, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nag, S.; Kumaria, S. In silico characterization and transcriptional modulation of phenylalanine ammonia lyase (PAL) by abiotic stresses in the medicinal orchid Vanda coerulea Griff. ex Lindl. Phytochemistry 2018, 156, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khenifi; M, L. ; Boudjeniba; Kameli Effects of salt stress on micropropagation of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.). Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2011, 10, 7840–7845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, M.; Mishra, A.; Jha, B. NaCl plays a key role for in vitro micropropagation of Salicornia brachiata, an extreme halophyte. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2012, 35, 313–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alturki, S. Effect of NaCl on Growth and Development of in vitro Plants of Date Palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.) ‘Khainazi’ Cultivar. Asian J. Plant Sci. 2018, 17, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, M. Effect of salt stress on in vitro organogenesis from nodal explant of Limnophila aromatica (Lamk.) Merr. and Bacopa monnieri (L.) Wettst. and their physio-morphological and biochemical responses. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2020, 26, 803–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li Y, Zhang Y, Feng F, Liang D, Cheng L, Ma F, et al. Overexpression of a Malus vacuolar Na+/H+ antiporter gene (MdNHX1) in apple rootstock M. 26 and its influence on salt tolerance. Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture (PCTOC). 2010;102:337-45.

- Kumar, K.; Debnath, P.; Singh, S.; Kumar, N. An Overview of Plant Phenolics and Their Involvement in Abiotic Stress Tolerance. Stresses 2023, 3, 570–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagananda G, Rajath S, Shankar PA, Rajani ML. Phytochemical evaluation and in vitro free radical scavenging activity of successive whole plant extract of orchid Cottonia Peduncularis. Res Art Biol Sci. 2013;3:91.

- Athipornchai, A.; Jullapo, N. Tyrosinase inhibitory and antioxidant activities of Orchid (Dendrobium spp.). South Afr. J. Bot. 2018, 119, 188–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashmi, K.; Shweta, S.; Sudeshna, C.; Vrushala, P.; Kekuda, T.; Raghavendra, H. Antibacterial and Radical Scavenging Activity of Selected Orchids of Karnataka, India. Sci. Technol. Arts Res. J. 2015, 4, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chand MB, Paudel MR, Pant B. The antioxidant activity of selected wild orchids of Nepal. Journal of Coastal Life Medicine. 2016;4(9):731-6.

- Sahakitpichan, P.; Mahidol, C.; Disadee, W.; Chimnoi, N.; Ruchirawat, S.; Kanchanapoom, T. Glucopyranosyloxybenzyl derivatives of (R)-2-benzylmalic acid and (R)-eucomic acid, and an aromatic glucoside from the pseudobulbs of Grammatophyllum speciosum. Tetrahedron 2013, 69, 1031–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 54. Duan X-H, Li Z-L, Yang D-S, Zhang F-L, Lin Q, Dai R. Study on the chemical constituents of Gastrodia elata. Journal of Chinese medicinal materials 2013, 36, 1608–11.

- Borges, A.; Ferreira, C.; Saavedra, M.J.; Simões, M. Antibacterial Activity and Mode of Action of Ferulic and Gallic Acids Against Pathogenic Bacteria. Microb. Drug Resist. 2013, 19, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouarab-Chibane, L.; Forquet, V.; Lantéri, P.; Clément, Y.; Léonard-Akkari, L.; Oulahal, N.; Degraeve, P.; Bordes, C. Antibacterial Properties of Polyphenols: Characterization and QSAR (Quantitative Structure–Activity Relationship) Models. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Cortazar, M.; López-Gayou, V.; Tortoriello, J.; Domínguez-Mendoza, B.E.; Ríos-Cortes, A.M.; Delgado-Macuil, R.; Hernández-Beteta, E.E.; Blé-González, E.A.; Zamilpa, A. Antimicrobial gastrodin derivatives isolated from Bacopa procumbens. Phytochem. Lett. 2019, 31, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamczak, A.; Ożarowski, M.; Karpiński, T.M. Antibacterial Activity of Some Flavonoids and Organic Acids Widely Distributed in Plants. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 9, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irimescu LS, Digută CF, Encea RŞ, Matei F. Preliminary study on the antimicrobial potential of phalaenopsis orchids methanolic extracts. Scientific Bulletin Series F Biotechnologies. 2020;24(2):149-53.

- Olivares CG, editor final degree project of biotechnology studies on the inhibitory potential of orchid extracts against acne associated bacteria 2020.

- Attard, E. A rapid microtitre plate Folin-Ciocalteu method for the assessment of polyphenols. Open Life Sci. 2013, 8, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herald, T.J.; Gadgil, P.; Tilley, M. High-throughput micro plate assays for screening flavonoid content and DPPH-scavenging activity in sorghum bran and flour. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2012, 92, 2326–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benzie, I.F.F.; Strain, J.J. The ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) as a measure of “antioxidant power”: The FRAP assay. Anal. Biochem. 1996, 239, 70–76. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0003269796902924.

- Basri, D.; Fan, S. The potential of aqueous and acetone extracts of galls ofQuercus infectoriaas antibacterial agents. Indian J. Pharmacol. 2005, 37, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment |

Hormone (mg/L) |

Number of shoots explant-1 | Fresh growth index | |||||

| BAP | NAA | 28 days | 35 days | 42 days | 28 days | 35 days | 42 days | |

| T1 | - | - | 9.00 ± 1.73b | 18.33 ± 1.53b | 19.33 ± 1.15b | 0.63 ± 0.11 | 5.44 ± 0.46b | 6.69 ± 0.40b |

| T2 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 16.00 ± 1.73a | 32.33 ± 2.52a | 35.00 ± 3.00a | 1.00 ± 0.34 | 8.78 ± 2.09a | 9.92 ± 1.31a |

| T3 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 7.67 ± 0.58bc | 18.00 ± 2.00b | 18.67 ± 2.08b | 0.55 ± 0.15 | 5.14 ± 0.77b | 6.41 ± 0.77bc |

| T4 | 2.0 | 0.5 | 4.33 ± 2.31c | 10.67 ± 1.15c | 12.33 ± 1.53c | 0.23 ± 0.07 | 4.44 ± 1.07bc | 4.88 ± 0.60cd |

| T5 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 8.00 ± 1.00bc | 12.67 ± 2.08c | 13.67 ± 1.53c | 0.66 ± 0.12 | 4.89 ± 0.19bc | 5.83 ± 0.06bc |

| T6 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 5.67 ± 1.15bc | 6.33 ± 1.15d | 6.67 ±0.58d | 0.38 ± 0.06 | 3.17 ± 1.11c | 3.82 ± 0.77d |

| Treatment | Immersion frequency | No. shoots/explant |

Shoot height (cm) |

Fresh growth index | |

| Time day-1 | Immersion | ||||

| IF1 | 8 | 5 min, every 3 h | 20.00 ± 0.82d | 2.77 ± 0.31bc | 0.23 ± 0.02c |

| IF2 | 4 | 5 min, every 6 h | 38.00 ± 2.94c | 1.93 ± 0.12bc | 2.12 ± 0.63b |

| IF3 | 2 | 5 min, every 12 h | 33.00 ± 3.27cd | 1.10 ± 0.33cd | 2.32 ± 0.50b |

| IF4 | 8 | 10 min, every 3 h | 127.00 ± 2.16a | 5.00 ± 0.51a | 4.26 ± 0.52a |

| IF5 | 4 | 10 min, every 6 h | 95.33 ± 7.59b | 1.27 ± 0.12d | 3.21 ± 0.59ab |

| IF6 | 2 | 10 min, every 12 h | 47.33 ± 5.56c | 3.70 ± 0.45b | 3.05 ± 0.50ab |

| Treatment | Medium |

Hormone (mg L-1) |

No. roots /explant |

Length of root (cm) |

Fresh growth index |

Shoot Height (cm) |

No. Leaves explant-1 |

Length of leaf (cm) |

|

| ½ MS | BAP | NAA | |||||||

| RT1 | ½ MS ½ MS |

1.0 | 0.5 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 0.40 ± 0.10 b | 1.17 ± 0.50 c | 2.35 ± 0.15 | 4.50 ± 0.50 | 1.25 ± 0.05 |

| RT2 | - | 0.5 | 0.50 ± 0.50b | 0.20 ± 0.20 b | 2.42 ± 0.08 | 3.45 ± 0.35 | 3.50 ± 0.50 | 2.20 ± 0.30 | |

| RT3 | MS | 1.0 | 0.5 | nd | nd | 1.75 ± 0.08 b | 2.65 ± 0.15 | 4.50 ± 0.50 | 0.95 ± 0.15 |

| RT4 | MS | - | 0.5 | nd | nd | 1.83 ± 0.17 b | 2.75 ± 0.25 | 3.50 ± 0.50 | 1.75 ± 0.25 |

| RT5 | VW* | - | - | 2.50 ± 0.50a | 1.35 ± 0.15 a | 3.92 ± 0.25 a | 2.85 ± 0.05 | 4.50 ± 0.50 | 2.25 ± 0.15 |

| RT6 | VW* | - | - | 0.50 ± 0.50b | 0.50 ± 0.50 b | 3.00 ± 0.33 ab | 3.35 ± 0.15 | 3.50 ± 0.50 | 0.95 ± 0.25 |

| Bacterium | MIC(mg mL-1) | MBC(mg mL-1) |

| S. aureus | 12.8 | 25.6 |

| S. epidermidis | 25.6 | 51.2 |

| P. acnes | 6.4 | 12.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).