1. Introduction

Over the past decade, Cryo-EM has become the method of choice for structure/function studies of membrane proteins. While the combination of direct detector cameras [

1] improved automated electron microscopes [

2] and sophisticated software algorithms [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7] have made obtaining high resolution data much easier than in the past, membrane proteins still retain some intrinsic properties that result in practical experimental difficulties. One of the key bottlenecks in studying the structure of membrane proteins is extracting them from their natural lipid bilayer, whilst maintaining their essential native structure and biochemical function [

8]. Advances in cryogenic electron tomography (cryo-ET) have made the study of some larger membrane proteins possible

in situ [

9,

10,

11]; many projects still require the purification of the isolated protein. Traditionally, detergents have been employed as agents to replace the lipid membrane, facilitating solubilisation and stabilising membrane proteins by acting as a proxy for the membrane environment. Detergents function as amphipathic molecules that interact simultaneously with both hydrophobic and hydrophilic regions of proteins, forming micelles that keep membrane proteins soluble in aqueous solution [

12]. Within the body of a micelle, the hydrophobic tails of the detergent molecules partition to form a hydrophobic core, which can then stably integrate hydrophobic compounds such as lipids and the non-polar amino acids within a protein. This central hydrophobic core is shielded from the aqueous environment by hydrophilic head groups on the detergent molecules, which interact with water through hydrogen bonding/electrostatic interactions and stabilise a micelle in solution [

13,

14]. Micelles are generally spheres or oblate discs, with the akyl chain length essentially determining the micelle dimensions [

15]. However detergents can form an array of alternative concentration dependant structures including inverted micelles, bilayers and worm-like tubes [

16] which are generally not appropriate for single particle studies.

Historically, the most ubiquitous and successful detergents in membrane protein purifications have been Beta-octyl-glucoside (BOG) and n-Dodecyl-β-D-maltose (DDM) [

17]. These are both non-ionic detergents frequently used to solubilise integral membrane proteins, mainly because they are considered ‘mild’; i.e. they pull proteins out of the membrane, maintain protein stability but do not denature them. This mildness is quantified by a combination of biochemical functional assays combined with structural appraisal. This contrasts with the harsher detergents such as Sodium Dodecyl sulfate (SDS), which will fully unfold and denature most proteins [

18]. Newer detergents have been developed, such as Lauryl Maltose Neopentyl Glycol (LMNG) with preferential properties including smaller and uniform micelles, a low critical micelle concentration (CMC), meaning fewer free detergent molecules are present, which in turn improves image quality [

19]. LMNG also appears to have hydrophobic tails with reduced mobility that enhances stability of micelles by improved packing around transmembrane helices [

20]. Micelles of the detergent n-dodecyl-β-melibioside (β-DDMB) may also be useful for smaller membrane proteins; a variety of experiments have shown β-DDM is ~30Kda smaller than DDM [

21]. To address these limitations of detergents, several alternative methodologies have been developed, including bicelles [

22] nanodiscs [

23,

24], styrene maleic acid lipid particles [

25] and amphipols [

26,

27,

28]. These innovative approaches offer some distinct strategic advantages in maintaining protein stability and functionality during purification, but as with every research methodology do not represent a panacea.

Nanodisc is a description for a nanoscale assembly of phospholipids within a stabilizing belt, typically an amphiphilic ‘membrane scaffold protein’ (MSP) [

11]. Apolipoprotein-I ApoA-I has been widely used as an MSP because it is composed of repeating series of short amphiphilic helices that can stably wrap around a lipid bilayer most commonly as two strands organised in an intercalated anti-parallel fashion [

29,

30]. Nanodiscs are assembled by mixing a detergent-solubilised protein with lipids and an MSP, then removing detergent in a process akin to reconstitution into liposomes. Therefore, the preparation of nanodiscs requires an initial use of detergent, can be relatively costly compared to single detergent use and requires considerable optimisation. Additional purification is usually required after the nanodisc formation to remove empty discs from the preparation. However, proteins prepared in this way are often stable, functional and amenable to characterisation by cryo-EM [

30,

31].

Styrene maleic acid (SMA) lipid particles (SMALPs) also consist of membrane proteins embedded in lipid and surrounded by a stabilizing amphipathic belt, in this case a styrene-co-maleic acid polymer [

25]. SMALPs offer a convenient and cost-effective alternative to detergents for membrane protein solubilisation and stabilisation [

32,

33], though their application in cryo-EM remains limited. SMALPs form spontaneously when styrene maleic acid copolymers are added to biological membranes, encapsulating membrane proteins and surrounding lipids into ~10 nm discs. As a result, they are sometimes referred to as ‘native nanodiscs’ [

34]. Notably, the copolymer is required only during solubilisation; the subsequent buffers are free of both polymer and detergent. Evidence suggests that SMALPs enhance the structural and functional stability of membrane proteins compared to detergent-based methods, likely due to the retention of native lipids [

35,

36]. This makes SMALPs a practical tool for membrane protein purification and analysis. Numerous proteins have now been purified using SMA [

37,

38,

39] and related polymers such as di-isobutylene maleic acid (DIBMA) [

40,

41]. One of the earliest cryo-EM applications involved AcrB in SMALPs [

33,

42], followed by the structure of alternative complex III from the respiratory chain of

Flavobacterium johnsoniae, where protein bound lipids were clearly resolved in the complex [

43].

Despite these successes and promise, cryo-EM studies using SMALPs remain relatively rare. Anecdotal reports suggest resolution may be limited, potentially due to the amorphous ice, though this has not been systematically investigated. Some studies have used SMA for solubilisation and purification prior to transferring proteins into amphipols or nanodiscs for cryo-EM [

44]. Additionally, a growing number of alternative polymers are being explored for their potential to improve the results from structural studies. Most of these iterate on the core styrene-maleic acid backbone, but with better control of polymer composition and properties [

45,

46].

Amphipols share similarities with both detergents and SMA [

47]. They are amphiphilic polymers designed to keep membrane proteins soluble in water when isolated from a membrane, but like detergents they form assemblies without significant lipid content [

48]. Rather than forming a micelle to solubilize hydrophobic transmembrane protein regions, they adsorb onto the hydrophobic transmembrane surfaces of proteins, shielding them from water and preventing denaturation [

47,

49]. No interference from micelles affects characterisation of proteins prepared in this way, and amphipols, like SMA, are used only once during a purification. However, amphipols rarely directly solubilize proteins from membranes and typically rely on an initial detergent purification. Depending on the protein, amphipols may provide a more stable environment for proteins than detergents, and have been used successfully for structure determination [

50].

In summary, while working with membrane protein systems, the use of detergents is sometimes unavoidable due to various experimental constraints. When this is the case, it is important to be aware of the potential complications they can introduce, especially in structural studies. This commentary research paper highlights several common issues that may arise throughout the Cryo-EM workflow when detergents are involved. It also offers practical insights, troubleshooting tips, and strategic approaches to help researchers navigate these challenges more effectively and improve the overall quality of their structural data.

3. Results & Discussion

Problems with membrane protein samples often only become apparent once a project moves to EM with grid preparation and image acquisition. At this stage, issues such as crystalline ice contamination and particle behaviour on grids (

Issue 1), or the dominance of empty detergent micelles in vitreous ice (

Issue 2), may emerge in the EM data. At the University of Manchester, the cryo-EM platform works closely with the BIOMOLs platform to support researchers through this critical early phase: an approach we recommend as best practice (see [

57]). To minimise these challenges before microscopy begins, a comprehensive buffer and detergent screen (e.g. Vitro-ease has a six-detergent matrix) can help identify optimal conditions (cf. [

58]). In our experience, around 50% of new projects start with sub-optimal buffer or detergent combinations which can be readily improved. Early screening is essential before investing in cryo-EM, where consumables (e.g., grids, C-clips, auto-grid cartridges) can cost approximately £400 per 10-grid batch. When combined with Mass Photometry (e.g. REFYN [

59]), this screening can provide valuable insights into sample degradation, aggregation, oligomeric state, and purity; saving significant staff time and avoiding unproductive efforts.

3.1. Issue 1: ‘Concave Lensing’ of Vitreous Ice in the Preparation of Cryo Grids

Preparing vitreous ice on cryo specific holey EM grids such as Quantifoils or C-flats [

60,

61], can produce a sample spreading problem with uneven particle distribution, that is endemic in cryo studies of membrane proteins (

Figure 1A, B). When a detergent is added to a buffer, one physical effect is a lowering of the surface tension of the solution, as the hydrophobic tails of the detergent molecules partition to the air water interface. [

62]. This has the effect of reducing the surface tension of a solution, such that it will spread much easier [

63]. On cryo-EM grids, we frequently observe a phenomenon we term

‘Concave Lensing’, shown in

Figure 1.

In this membrane protein sample, the decreased surface tension of the solution across the Quantifoil hole has caused the solution to thin from the centre outwards forming a concave lens shape across the hole. This is probably exacerbated by the slightly bevelled edge apparent in Quantifoil grids. This has several sample effects that can be observed in the data. Firstly, the centre of the hole has very thin ice that gradually thickens outwards as the vitreous ice is tracked towards the carbon surface. From a cryo processing point-of-view, this thin amorphous ice is problematic because it is usually unstable and will burn or rip in an electron beam very easily [

64,

65]. If it doesn’t burn or rip, it will usually produce excessive particle motion in the vitreous ice which may not be correctable [

66]. Secondly, the central volume within the thin amorphous ice section is so small the protein may not physically fit in it. The amorphous ice then pushes the sample towards the edges of the carbon in a gradient and this has the effect of the overlapping particles in layers. Finally, this pushing effect in a limited gradient can exacerbate problems with particle orientation and

Figure 1 shows the particles are nearly exclusively orientated in a top-view orientation which makes 3D processing impossible. The particles around the lip of the thinnest central area, have congregated around with a regular interparticle distance indicating a boundary interaction. Other studies have shown an optimal concentration of detergent between 0.05 and 0.4%

(w/v) and that the presence of a low concentration of detergent with a high critical micellar concentration may protect protein from denaturation effects at the air-water interface [

67].

The most commonly used instrument for preparing Cryo-EM grids is the Vitrobot [

68]. It is worth highlighting a detail often overlooked by inexperienced users: visually inspecting the blotting papers used during excess sample removal (

Figure 1C). The Vitrobot MK IV controls amorphous ice thickness using a simple method and robotically presses 2 discs of filter-paper onto a cryo EM grid suspended by tweezers within a humidity control chamber. The blotting is thus controlled by the length of blot time and how tightly the 2 discs of filter paper come together (the blot ‘force’). With detergent-purified samples, it is common to observe that standard blotting conditions produce larger overlapping blot circles, as the sample tends to spread more readily,

Figure 1C. In our experience, reducing the blot force slightly (thereby applying less pressure to the grids) can help mitigate this effect and in turn reduce the lensing artefact on imaged grids. When these problems inevitably arise, we have found that a systematic, matrix-style approach—testing variables such as grid type, grid-bar metal, hole size, and spacing—can be particularly effective. Alternative Cryo-EM grids such as UltrAuFoil and HexAuFoil [

60,

69] feature full metal surfaces and support smaller hole diameters of 0.6 µm and 0.31 µm respectively, offer promising alternatives. Their hexagonal packing and reduced hole size may promote more uniform amorphous ice distribution within the holes. This can be especially advantageous for membrane proteins and may help prevent the vitreous ice buckling under electron beam irradiation.

Another issue that may arise, even where concave lensing is avoided, is

‘Interface Accumulation’. This phenomenon can occur with all proteins but is more commonly observed in detergent based membrane protein preparations. It typically presents as a ring of protein adhering to the carbon/ice boundary, as shown in

Figure 2. The underlying causes of this phenomenon remain unclear. However, there is a notable charge difference between glow-discharged carbon and the thin buffer layer and this may provide a preferential environment for many proteins.. While not as experimentally limiting as lensing, interface accumulation can still significantly reduce the number of ‘pickable’ particles available for analysis, because so many are pushing against the rim of carbon. As a result, more images and additional initial processing time may be required. It is also worth considering using a different grid preparation system in these cases. Most labs use the TF Vitrobot as their work-horse instrument for grid preparation because they are relatively cheap and usually produce usable grids to bootstrap into a project [

68]. Some other possibilities include the Chameleon [

70], Cryogenium [

71] or Spotiton [

72] which may be particularly advantageous for detergent membrane protein samples. The Chameleon robot uses blot free ‘self-wicking’ grids and a nl scale direct volume dispenser onto the grid surface, so excessive spreading of samples can be avoided. The wicking generally occurs on the millsecond scale compared to seconds for the Vitrobot and so ice thickness in real time can be more precisely monitored. However the Chameleon does generally require a higher protein concentration (>5 mg/ml) and so up-concentration of micelles can emerge as a new problem (see Issue 2). The Spotiton system uses a completely different approach and uses a inkjet style spray of sample in the picolitre to nanolitre volume scale and directly applies the sample to grid in such small amounts blotting is not required [

72].

Excessive sample spreading and the formation of ‘concave lensing’ remains the most challenging issue for membrane protein grid preparation. If these alternatives fail to resolve the issue, switching to a different detergent or solubilising agent may be the only viable solution.

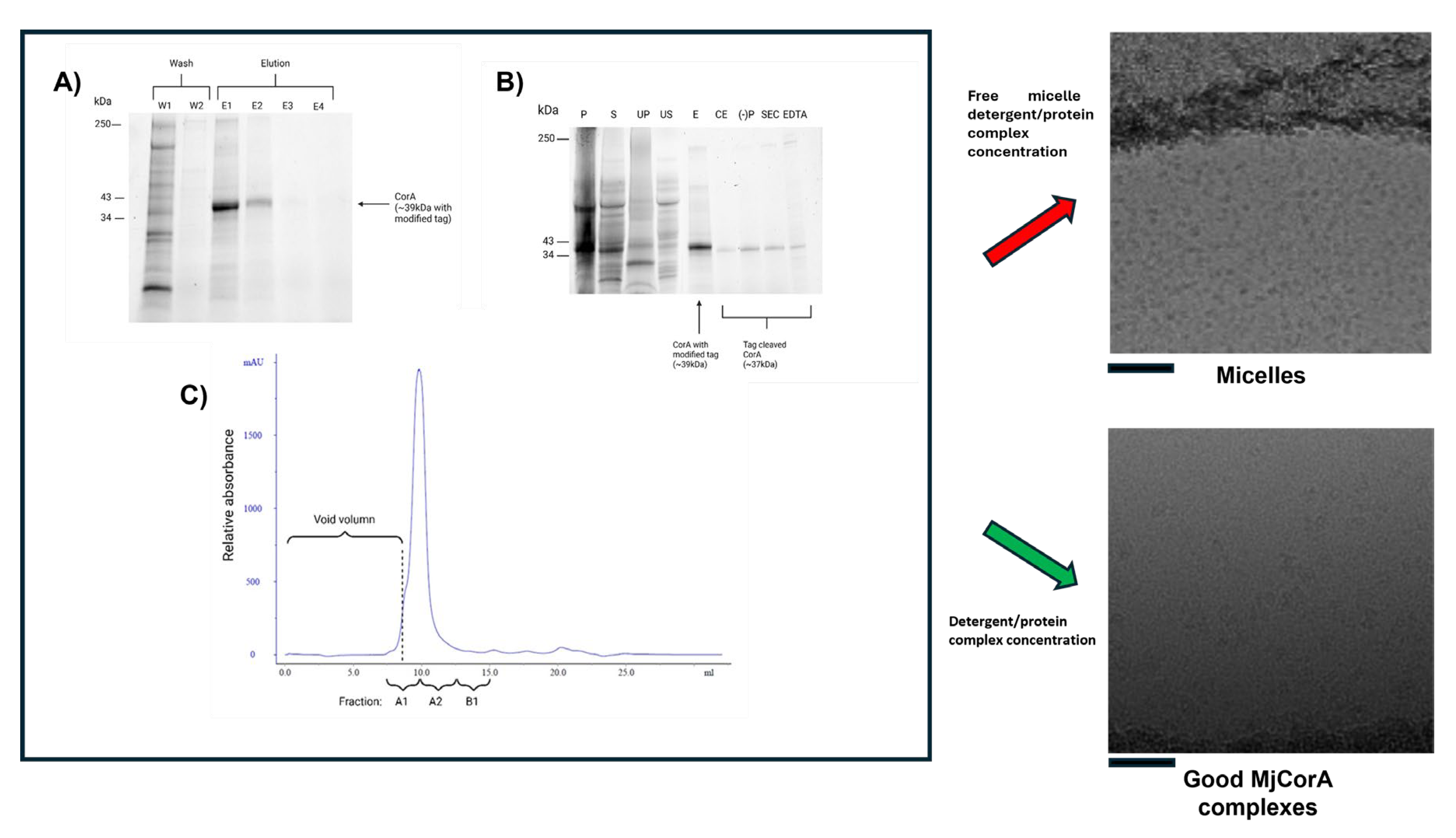

3.2. Issue 2: Empty Micelle ‘Up-Concentration’

A related challenge to the issue of ‘

Concave Lensing’ arises when samples become overwhelmed by excess empty detergent micelles—despite purity metrics suggesting otherwise. In

Figure 3, we illustrate a clear example we encountered during the initial purification of the divalent metal ion transporter protein MjCorA in DDM. Panels 3A–C clearly show the protein is present at high purity and at concentrations that should be readily visible by cryo-EM. The purification followed a multi-step protocol previously optimized for sample stability and solubility [

51]:

Detergent is maintained throughout to preserve membrane protein solubility. However, early cryo-EM grid screenings revealed a consistent result with no visible protein. The EM field was dominated by uniform, empty micelles (

Figure 3, top right panel). Initially, we used excess detergent in chromatography buffers to ensure the protein remained soluble and to prevent aggregation. After affinity purification, detergent levels were reduced to approach the critical micelle concentration (CMC) during SEC. Since DDM has negligible absorbance at 280 nm and is disrupted by SDS during electrophoresis, these micelles remained essentially invisible during purification.

Figure 3.

Micelle domination at the end of purification. A) Purification of MjCorA protein via Ni-NTA affinity. SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) of fractions from the affinity purification of the MjCorA protein are shown. W1/2: Wash steps; E1-4: Elution with imidazole.

B) SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) illustrating the purification of the MjCorA protein. Lanes show representative fractions from each purification step. P: Pellet of E.coli lysate; S: Supernatant of lysate; UP: membrane isolation ultracentrifugation pellet; US: corresponding ultracentrifugation supernatant; E: Pooled Eluant from NiNTA affinity; CE: product after thrombin digestion; (-)P: Flow through of negative purification; SEC: Pooled eluants after size exclusion chromatography; EDTA: EDTA treated MjCorA.

C) Size-exclusion chromatography analysis of MjCorA. Fractions analysed by SDS_PAGE for purity are labelled, those pooled for Cryo-EM analysis are A1, A2. Panels to the right show the effect of centricon treatment on the final cryo-EM data fields. Image scale bars = 500 Å. Raw gel data is provided in

Figure S1.

Figure 3.

Micelle domination at the end of purification. A) Purification of MjCorA protein via Ni-NTA affinity. SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) of fractions from the affinity purification of the MjCorA protein are shown. W1/2: Wash steps; E1-4: Elution with imidazole.

B) SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) illustrating the purification of the MjCorA protein. Lanes show representative fractions from each purification step. P: Pellet of E.coli lysate; S: Supernatant of lysate; UP: membrane isolation ultracentrifugation pellet; US: corresponding ultracentrifugation supernatant; E: Pooled Eluant from NiNTA affinity; CE: product after thrombin digestion; (-)P: Flow through of negative purification; SEC: Pooled eluants after size exclusion chromatography; EDTA: EDTA treated MjCorA.

C) Size-exclusion chromatography analysis of MjCorA. Fractions analysed by SDS_PAGE for purity are labelled, those pooled for Cryo-EM analysis are A1, A2. Panels to the right show the effect of centricon treatment on the final cryo-EM data fields. Image scale bars = 500 Å. Raw gel data is provided in

Figure S1.

Systematic control experiments eventually linked the issue to the final concentration step using centrifugal concentrators Centricons (or equivalent membrane concentrators). In our hands the important factors are the use of a reconstituted cellulose membrane with a large molecular weight cut off. Free micelles and monomeric detergent should pass through the concentrator membrane with other buffer components: Thus, preserving the solution conditions for the membrane protein whilst concentrating the detergent protein complex alone. The size and aggregation number of a DDM micelle has been determined by neutron scattering [

73] giving an approximate micelle molecular weight of 66kDa. Using 100kDa concentrators pre-washed with detergent-free buffer before use reproducibly eliminated the problem of excess free micelles (

Figure 3, lower right panel). This subtle, but significant artifact is one we have encountered across multiple membrane protein systems (P-gp, CFTR, WzzB

ST, MjCorA). We recommend that novice users consider this possibility if they observe similar issues—especially when their cryo-EM grids appear dominated by micelles rather than populated with identifiable protein.

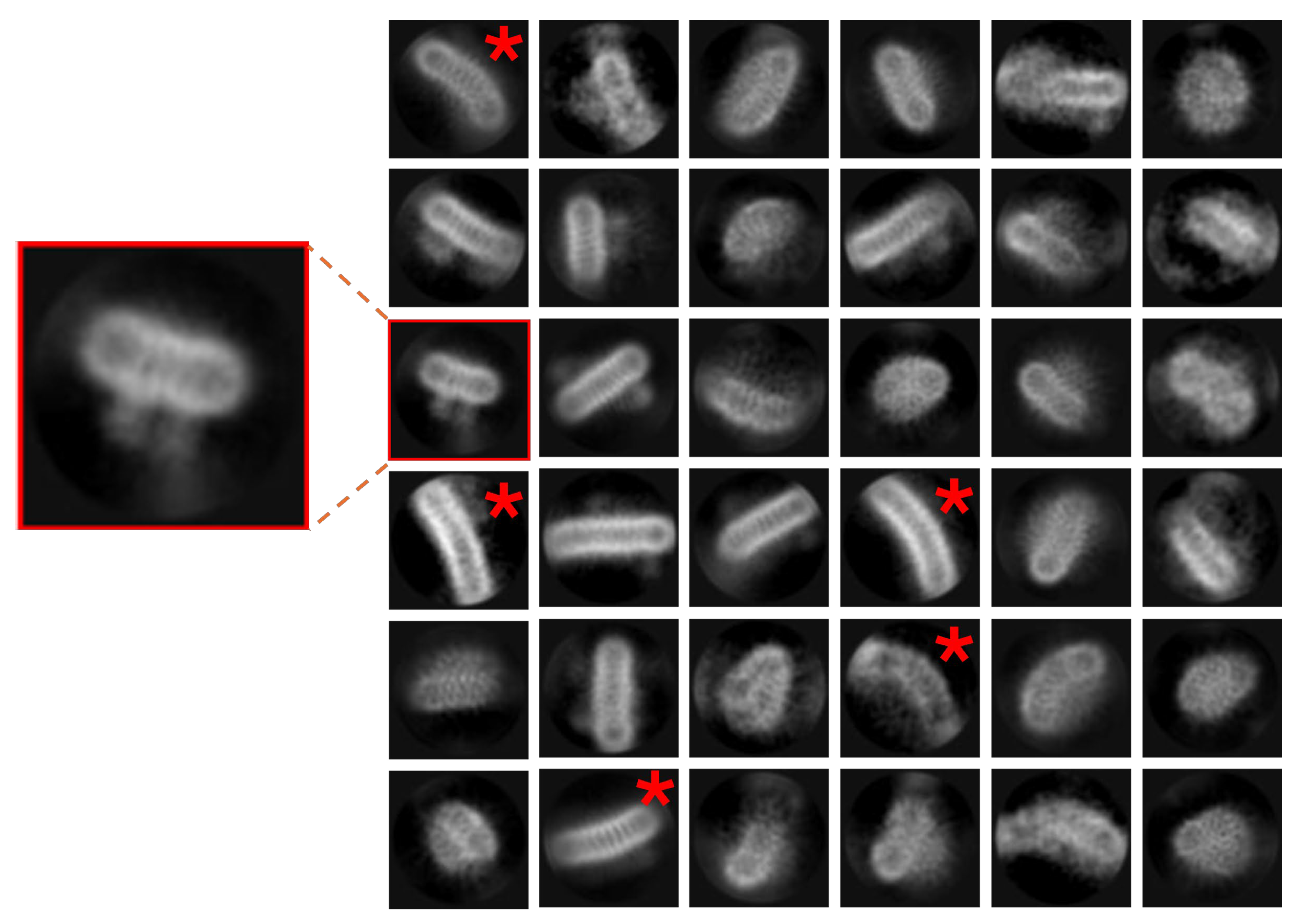

3.3. Issue 3: Empty Micelles ‘Swamping’ of 2D Classification & Unusual Micelle Structures

As discussed in the previous section, when handling detergent solubilised membrane proteins, the detergent must be kept at a concentration above the CMC to stabilise the bulk solvent behaviour of the sample. The free, empty micelles when concentrated are also observable in micrographs. For some membrane proteins, especially those which are small or completely embedded within the membrane with little-to-no protruding protein densities, these empty micelles can often be visually indistinguishable from micelles containing protein. In these systems, the full extent of the issue is often only apparent at the 2D classification stage of data processing, where secondary structure features like transmembrane helices in the micelle should become readily visible.

Figure 4 highlights this issue in a small membrane protein. Even after running through 2 rounds of 2D classifications and reducing the dataset size by ~93%, the sample remains comminated with empty micelles, essentially because the shell of the micelle head layer is a strong low resolution feature with high contrast. In ‘normal’ datasets, repeated rounds of 2D classification can be used to clean particle datasets from contaminating particles, aggregates or carbon rim, but this is computationally expensive and time consuming. The dominating of holes with empty detergent micelles reduces the number of particles of protein in the image, requiring in effect more data to be collected. This issue can become more pronounced when concentrating low yielding proteins after SEC, or when adding detergent solubilised hydrophobic substrates to a membrane protein sample. An attempt to improve the sample in

Figure 4 was made through purification in DDM with the incorporation of a lipidic substratein an attempt to obtain a co-structure. However, following the final purification steps, a high concentration of detergent micelle was still present in the solution. Only after repeated rounds of 2D classification was it possible to distinguish the protein from the empty micelles. If this problem persists, it is worth swopping between different software packages and trying different variations on the 2D class sorting.

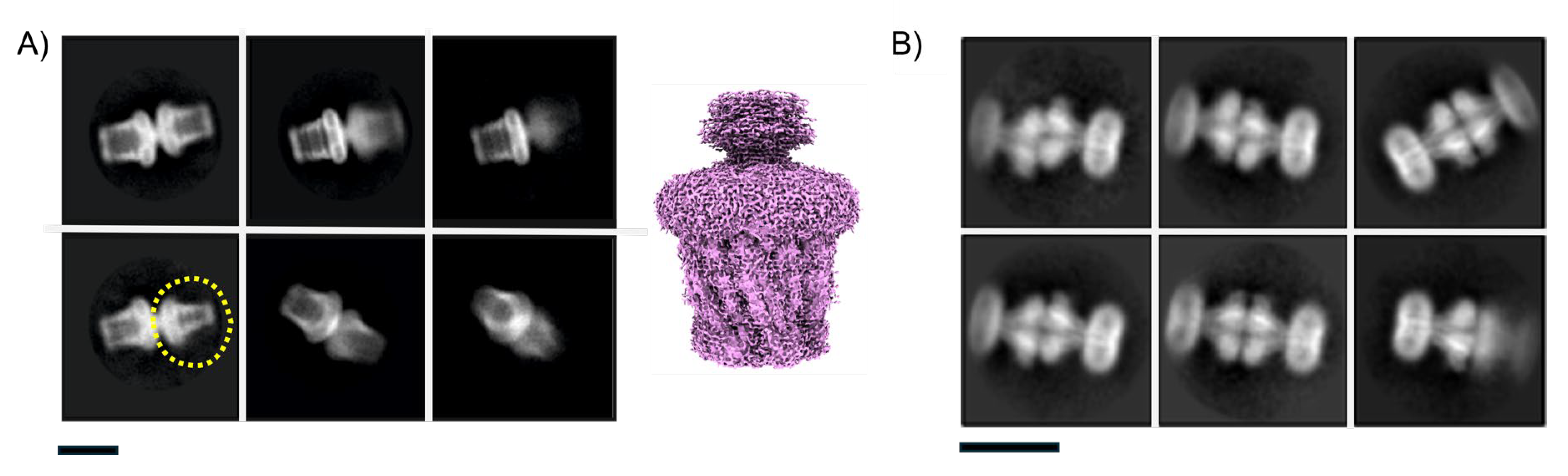

Figure 5 presents an example where unusual detergent micelle architectures can be observed in the micrograph images. In this example, the detergent LMNG has formed ‘traditional’ structures which are to be expected, as highlighted in the red box, but additional larger structures have also become apparent during 2D classification. Non-ionic detergents like LMNG are known to be able to form elongated, worm like structures [

67,

74]. The appearance of these structures is related the over concentration of the detergent used (which can increase during a final concentration step as noted above). Although these larger structures are usually clearly visible in the micrographs, and may not appear to cause an issue initially, they can cause issues during the particle classification, and add more time to the data processing pipeline. Careful optimisation and possible lowering of the detergent concentration used should alleviate any issue.

In general, removing excess detergent always presents a challenge, since the detergent

must be present above the CMC to prevent protein denaturation. As such, one must always have an excess of detergent present and free micelles will almost always be present – the goal is to minimise this. One possible solution to this issue is to employ ion-exchange chromatography as an additional step following gel filtration chromatography. The protein can be bound to a column and eluted in a smaller volume, thus concentrating the protein without concentrating detergent micelles. Additionally, the concentration of detergent can be lowered at the gel filtration step to closer to the CMC (for example ~1.5x CMC) [

75]. Similarly, gradient centrifugation approaches such as GraDeR can be used to separate empty detergent micelles from detergent solubilised proteins [

76]. The suitability for these approaches are likely to be protein dependent. Additionally, low CMC detergents can also be trialled. Lauryl Maltose Neopentyl Glycol (LMNG) for example is often used for membrane proteins as it has a low CMC and is difficult to displace with another detergent. As such, the detergent remains bound to the protein even in the absence of excess detergents. Performing the final gel filtration step in buffers without detergent can be considered, however this is likely to result in sample aggregation and denaturation. If a researcher does persist with this type of data, it may worth trying to change the sensitivity of the resolution and CTF parameters to bypass the very low resolution signal micelles can contribute in the image processing software, but this can create as many problems as it solves.

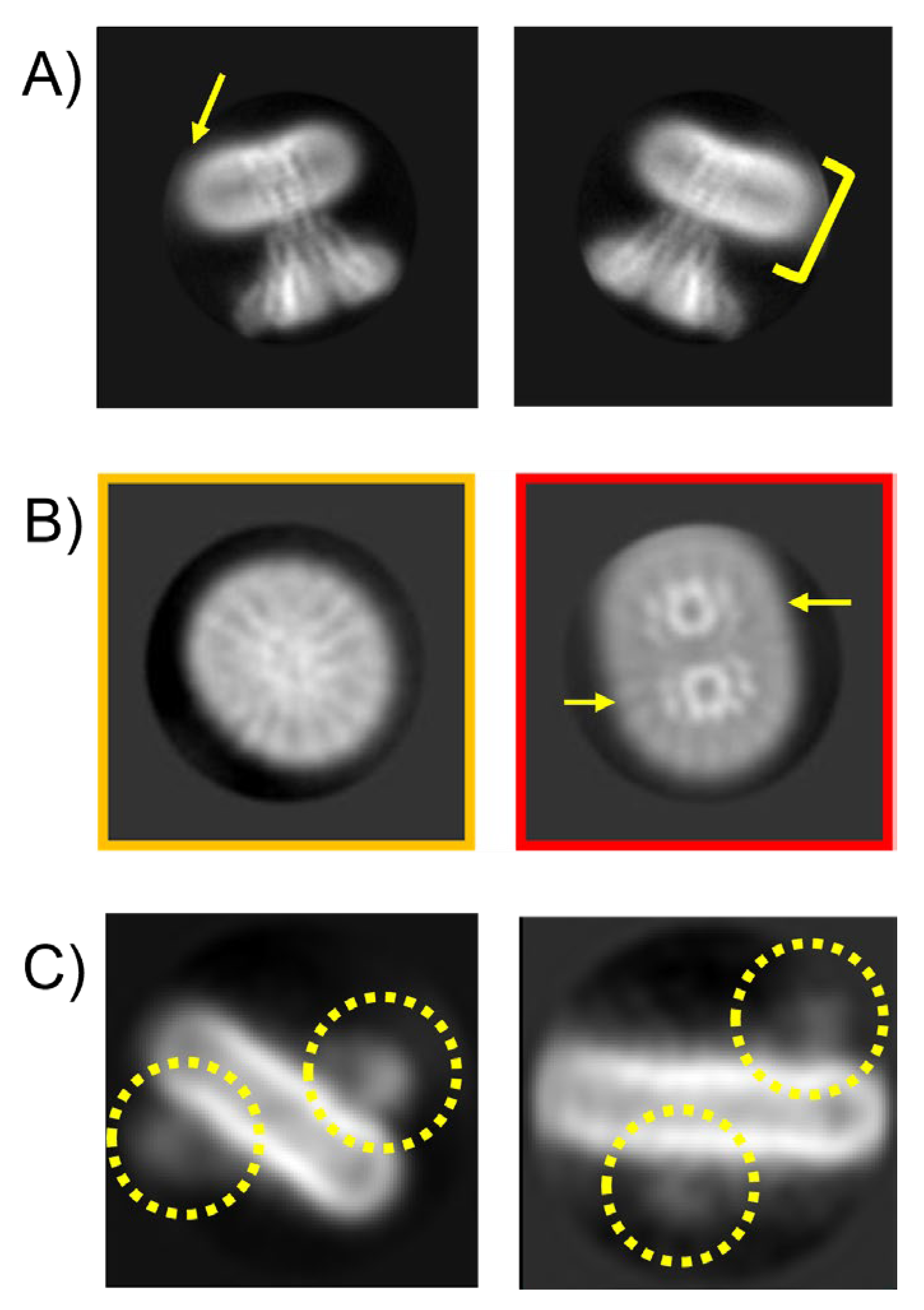

3.4. Issue 4: Projection Contamination from Detergent Driven Oligomerisation

Membrane proteins often exhibit unexpected associations, including the formation of pseudo-D-symmetrical arrangements. D-Symmetry is frequently found in modular enzymes [

77] which have a structure with 1 n-fold rotational axis and a second two-fold axes perpendicular to the main rotational axis. In contrast to complexes like chaperones where the D symmetry is related to structure and allosteric control (e.g. GroeEL), in membrane proteins it is likely artefactual and non-physiological; although in highly curved membrane structures found in mitochondria or chloroplasts, the folding means it may possible.

Figure 6 presents two distinct examples of such none physiological interactions, each demonstrating different structural interfaces:

(A) The capsular polysaccharide protein complex WzzB

ST forms an end-to-end assembly via the micelle-facing surface;

(B) The divalent ion channel MjCorA exhibits a similar end-to-end interaction, but through its cytoplasmic extensions, or "legs," which protrude from the membrane. From a 2D image processing standpoint, these interactions can complicate particle averaging. ‘Contaminated’ side views can be discarded or tightly masked, but top-views can persist. The interface is also not exact, so there is some slide resulting in less precise alignment. It is apparent as the projections start to tilt, the contaminating under layer influences signal,

Figure 6A lower panel. In strictly side-on orientations, particles can be selected, aggressively masked, and centered to exclude density contributions from adjacent particles. However, challenges arise when side views are partially tilted, making it difficult to distinguish overlapping densities. This issue is exacerbated in top-views looking down the long axis, where contaminating density from underlying particles is harder to eliminate. In the case of WzzB

ST, the pseudo-D symmetry is approximate and slides reducing the resolution in both halves of the pseudo complex, necessitating more aggressive data pruning. This reduces the achievable resolution or requires larger datasets to compensate. For the MjCorA, some interactions appear more specific, with discernible secondary structure at the interface between complexes meaning the D-symmetry has precise interaction, but cannot be physiological because of the arrangement of the cell membrane

in vivo. These top-view particles cannot be reliably used and should either be excluded from the dataset or subjected to more complex particle subtraction workflows. Both these scenarios increase computational demands, particularly GPU usage and processing time.

A surface-rendered reconstruction of a WzzB

ST complex, generated using loose particle selection and without masking, illustrates how these artifacts manifest in 3D processing (Figure6A, right). Compared to the final high resolution dataset (see

Figure 9 later ), the resolution is lower, and a diffuse density is visible beneath the micelle—attributed to contributions from misaligned, overlapping particles.

3.5. Issue 5: Irregular Micelle Insertions

Another 2D processing issue that only becomes apparent after substantial analysis is that protein insertion into micelles is not always uniform or predictable. As shown in

Figure 7, proteins can exhibit unusual organisations within micelles. For example, in

Figure 7A, the protein sits asymmetrically, off-center within the micelle. Micelles are flexible, dynamic structures that can deform easily or even merge with one another, so this behaviour can be expected. It can, however, lead to uneven detergent distribution, especially around proteins with irregular or tilted transmembrane helices (unpublished observations on ABCB6) or amphipathic surface regions. In some cases, particularly when using a high protein-to-detergent ratio, micelles may encapsulate multiple protein complexes (

Figure 7B).

Additionally, larger micelles can accommodate proteins in random up/down orientations (

Figure 7C), further complicating analysis. Unlike micelles, native membranes have intrinsic lipid asymmetry. For instance, the E. coli outer membrane contains lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in the outer leaflet and phospholipids in the inner leaflet. This asymmetry is essential for membrane function and is actively maintained by dedicated lipid transport proteins [

78]. Interestingly, the first high-resolution structure of human CFTR was only achieved after adding 0.2% cholesterol to the detergent LMNG [

79]. Cholesterol stabilizes membranes by intercalating between lipid tails and broadening the membrane’s phase transition temperature[

80]. In contrast, micelles are chemically uniform and lack the structural complexity of a lipid bilayer.

These micelle-related issues can lead to significant processing inefficiencies and wasted computational effort.

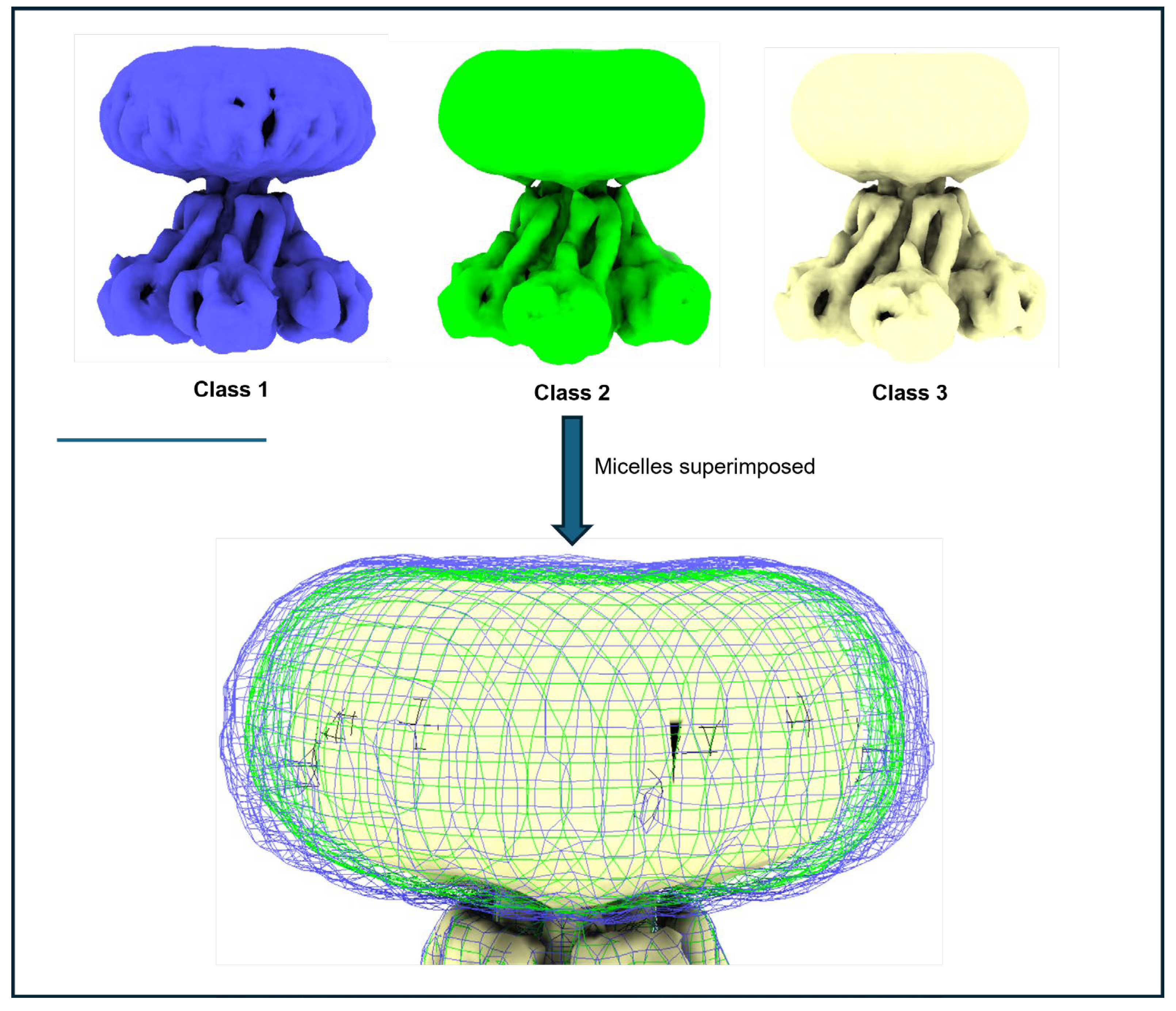

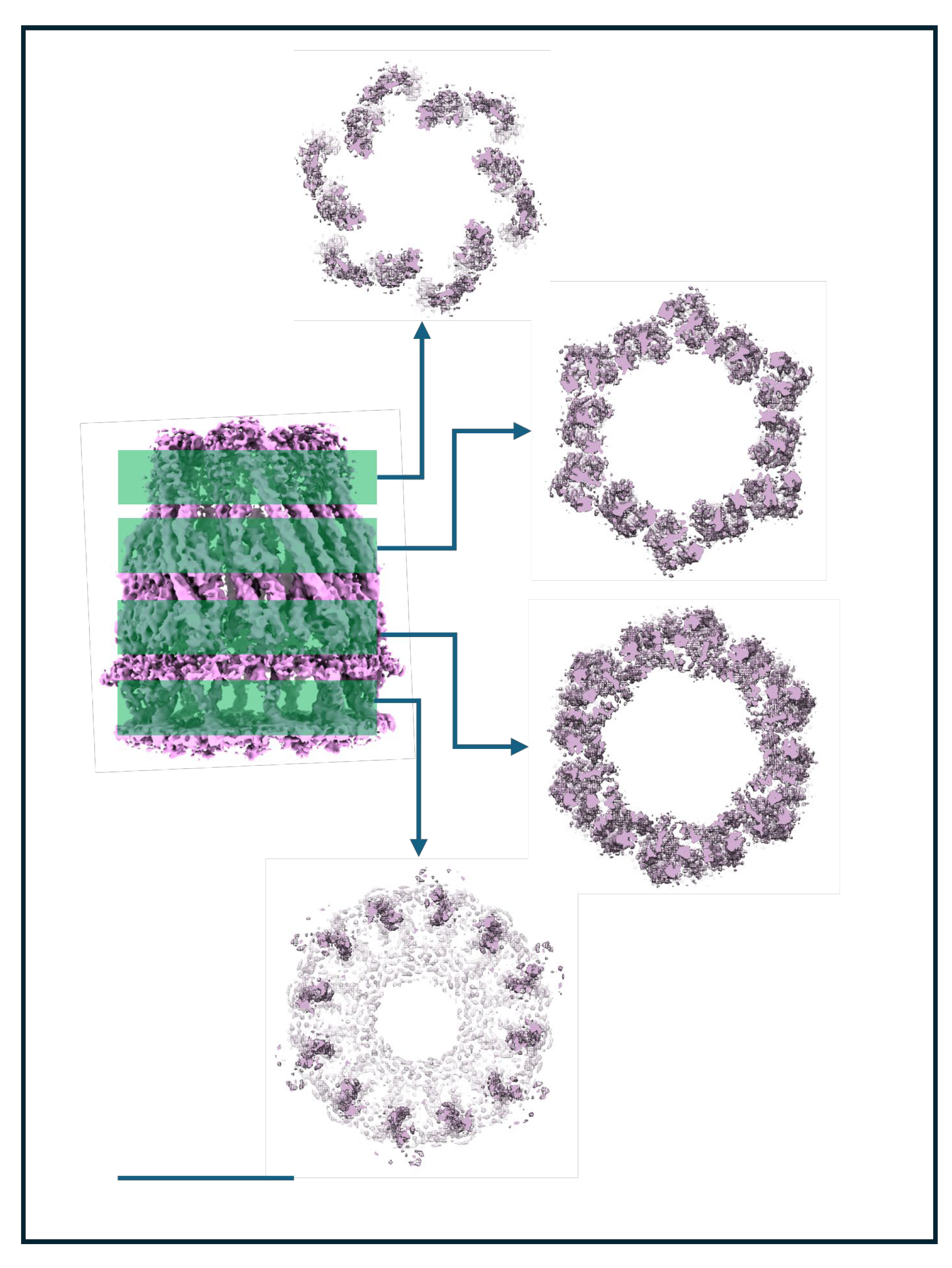

3.6. Issue 6: Variable Micelle Dimensions in 3D Structures

During 3D heterogeneity classification in software such as RELION or CryoSPARC (discussed in [

81]), the primary goal is to sort datasets into distinct conformational states, separate intact complexes from partially assembled or damaged ones, and enhance resolution by focusing on more homogeneous subsets of data. While achieving the highest possible resolution is often the main objective, the discarded classes can also provide valuable insights into sample characteristics.

This becomes especially relevant when working with detergent-solubilised proteins, where micelle variability often dominates these analyses.

Figure 8 illustrates this using an initial 3D classification of a MjCorA dataset. Three preliminary structures were generated from a cleaned 2D dataset of ~550,000 particles. At lower resolution, the main difference among them is the width of the DDM micelle. In this case, the pentameric protein complex is relatively rigid and conformationally stable, with very little difference, while the micelle varies in size by ~15% in the X/Y plane. Although later processing steps—such as selective masking, particle subtraction, and BLUSH [

3] can reduce these effects, early analyses are often confounded by micelle variability, which can obscure meaningful protein differences and complicate interpretation.

3.7. Issue 7: Unusual Symmetries

The common assumption when extracting a membrane protein into detergent is that a single functional unit—monomeric or oligomeric—is reconstituted into one micelle. However, as shown in

Figure 7B/C, this is not always the case. A further complication is the ability to generate high-resolution structures whose biological relevance remains unclear (

Figure 9).

WzzB

st is a bacterial inner membrane protein involved in lipopolysaccharide (LPS) O-antigen biosynthesis, a key component of the Gram-negative outer membrane. As a polysaccharide co-polymerase, WzzB

st regulates the modal chain length of O-antigen polysaccharides, which are critical for virulence, immune evasion, and resistance to environmental stress [

82]. It does not polymerize sugars directly but ensures consistent chain length. Previous cryo-EM studies of WzzB

st and its homologs have revealed oligomeric assemblies forming either C4 octamers [

83], C8 octamers[

84] or C12 dodecamers [

52]. The physiological relevance of these forms remains unclear, though the C8 symmetry aligns with other LPS assembly components such as Wza [

85] and the most recent structure reveals that the protein WzyE, a glycosyltransferase, sits within the chamber at the periplasmic face and controls polymerisation of polymer presumably extruded through Wzz like a nozzle to the outer membrane components [

83]. In our earlier C12 dodecameric dataset [

52], additional analysis has revealed a sub-organization of a dodecamer with C6 symmetry, with the dodecamer forming a ring of dimers within the micelle. Our previous work reported the WzzB

st dodecamer at 9 Å resolution. In this follow-up, we improved resolution to ~4.2Å, primarily through better sample preparation: cleaner grids, higher particle concentration, and thinner ice (see

Figure 2). The improved algorithms in BLUSH, also allow for better particle separation on other projects [

86] and on occasion excessive particle binning in early analysis can overlook subtlety in particle orientations and organisation.

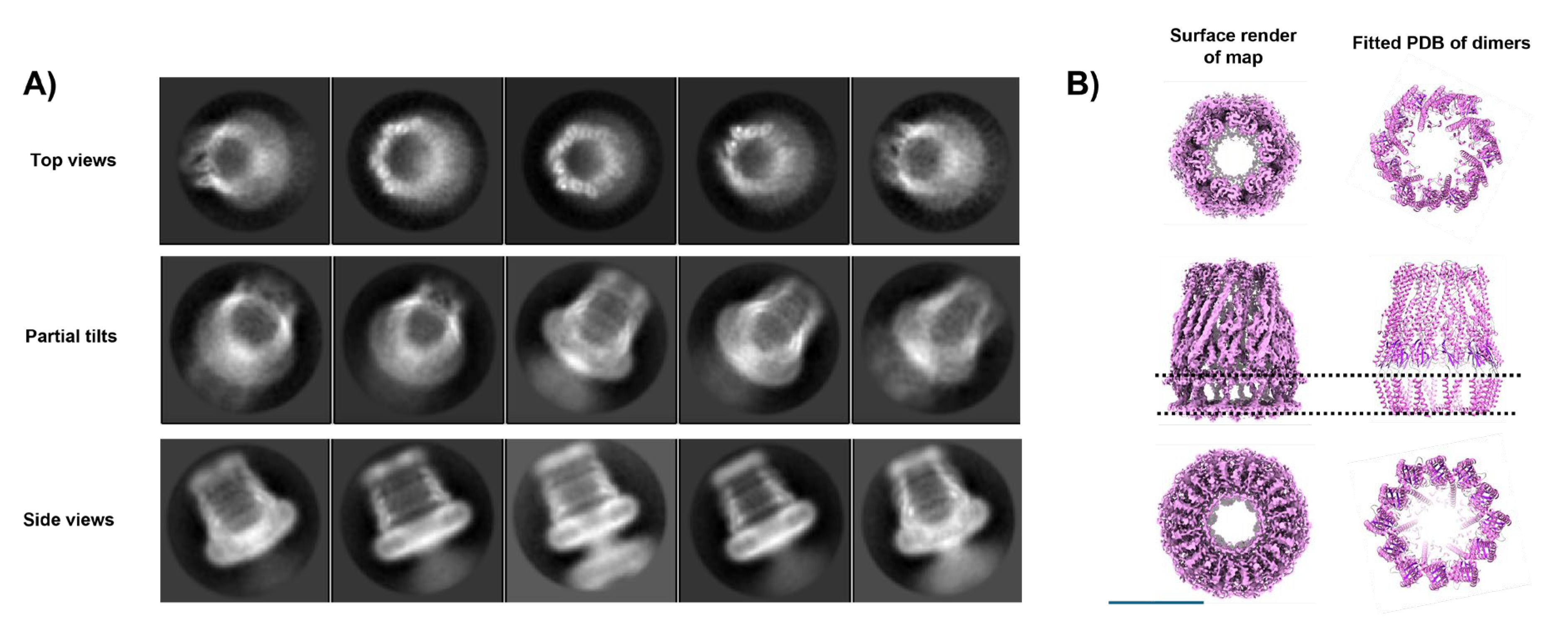

This improvement was evident immediately in the reference-free 2D classes. Side views revealed helices in both periplasmic and transmembrane regions, while top views showed 12 radially arranged subunits that displayed a distinct hexagonal shape, indicating C6 symmetry despite the dodecameric composition (

Figure 9A). There was another smaller oligomer present in the sample,

Figure 6A. We were unable to solve this due to lack of complementary orientations but size estimates are consistent with a tetramer. The 3D structure of the WzzB

st dodecamer reveals a bell-shaped hollow chamber oriented toward the periplasmic face of the inner membrane, consistent with previous structural work. While earlier work applied C12 symmetry [

52], the higher-resolution data of the subset, now show the oligomer in this preparation forms a ring of six dimers (

Figure 9B). The two transmembrane helices form a unique cross-braced motif, further stabilized by opposing cytosolic N- and C-terminal amphipathic helices. Oligomerisation is primarily driven by periplasmic domain residues, with each dimer associating via a large interface dominated by α-helical elements. Notably, no subunit-subunit contacts are observed within the lipid-embedded region. The overall dodecameric complex is offset into a corrugated C6 ring of WzzB

st dimers, though this symmetry is largely restricted to the periplasmic region; the transmembrane domains and termini show only minor deviations from C12 symmetry.

Figure 10 illustrates this phenomena with volume slices through the height of complex.

The transmembrane helices appear aligned not only by adjacent periplasmic domains but also by the cytoplasmic N- and C-termini, which stabilise the structure on the cytoplasmic face. These features are visible from the cytoplasmic view, where clear densities sit beneath the detergent micelle, perpendicular to the C6 symmetry axis (

Figure 9B &

Figure S2). The atomic model reveals a well-defined amphipathic helix at the N-terminus and a more loosely structured, marginally amphipathic helix at the C-terminus (

Figure S2), which correspond to these well.

In summary, the structure while interesting, is something of an enigma. It’s novel, distinct from previously published forms, and marked by a unique C6 arrangement. This hints the complex may form monomers or dimers capable of supporting a ratcheting assembly mechanism in vivo, or has several conformational variants that may assemble or disassemble throughout the different stages of LPS synthesis. While dimer contacts are clearly driven by protein interactions outside the micelle, the micelle itself adopts an unusual donut-like micelle torus, in contrast to the typical disc-like detergent micelles. The detergent may allow the protein to adopt different symmetries within the same oligomeric form resulting in the effects seen in Cryo-EM at high resolution.Clearly this system needs further refinement and highlights the ambiguity that using detergent can bring to a system. An alternative solubilisation system would help in this case to resolve the significance.

Figure 1.

A) Micrograph of a detergent solubilised membrane protein in a hole on a Quantifoil 1.3/1.2 carbon grid demonstrating ‘Concave Lensing’. Image courtesy of Dr. Jessica Kleiz-Ferreira (KU Leuven), with imaging conditions described in the Methods. Scale bar = 500 Å. B) The thin empty ice in the middle of the hole forces the protein to the edge of the hole, where it has adopted a preferred orientation; shown in cartoon. C) Blotting patterns on a used Vitrobot Mark IV filter paper – the spreading tendency of detergent solutions can be seen as larger overlapping blotting spots.

Figure 1.

A) Micrograph of a detergent solubilised membrane protein in a hole on a Quantifoil 1.3/1.2 carbon grid demonstrating ‘Concave Lensing’. Image courtesy of Dr. Jessica Kleiz-Ferreira (KU Leuven), with imaging conditions described in the Methods. Scale bar = 500 Å. B) The thin empty ice in the middle of the hole forces the protein to the edge of the hole, where it has adopted a preferred orientation; shown in cartoon. C) Blotting patterns on a used Vitrobot Mark IV filter paper – the spreading tendency of detergent solutions can be seen as larger overlapping blotting spots.

Figure 2.

Particle accumulation along the carbon rim at the ice/carbon interface. An example EM field of WzzBst has avoided concave lensing, but ~40-50% of observable particles have accumulated around the edge of the carbon (red circles). Complexes picked for analysis are shown in 200 Å yellow selection boxes. Particles can also be observed on the carbon – some examples are shown in dotted circles. The Fourier transform shows the resolution extending in the image past the diffuse ice ring at 3.7 Å resolution. Scale Bar = 500 Å.

Figure 2.

Particle accumulation along the carbon rim at the ice/carbon interface. An example EM field of WzzBst has avoided concave lensing, but ~40-50% of observable particles have accumulated around the edge of the carbon (red circles). Complexes picked for analysis are shown in 200 Å yellow selection boxes. Particles can also be observed on the carbon – some examples are shown in dotted circles. The Fourier transform shows the resolution extending in the image past the diffuse ice ring at 3.7 Å resolution. Scale Bar = 500 Å.

Figure 4.

Micelles may ‘swamp’ out repeated 2D classifications of a bacterial membrane bound glycosyltransferase enzyme. A) Results of the first round of 2D classification are shown on the left (sub-set of the entire data set) where only micelles are apparently visible due to the averaging of 2D classification. On the right B), following repeated 2D rounds of classification, some protein classes are visible (highlighted in red box) but micelles still dominate the classes. Box = 462 Å2.

Figure 4.

Micelles may ‘swamp’ out repeated 2D classifications of a bacterial membrane bound glycosyltransferase enzyme. A) Results of the first round of 2D classification are shown on the left (sub-set of the entire data set) where only micelles are apparently visible due to the averaging of 2D classification. On the right B), following repeated 2D rounds of classification, some protein classes are visible (highlighted in red box) but micelles still dominate the classes. Box = 462 Å2.

Figure 5.

Unusual micellular artifacts and structures. Some detergents (such as 2,2-didecylpropane-1,3-bis-β-D-maltopyranoside (LMNG) used in the example here) are prone to forming an array of micelle structures with different sizes, lengths and unusual curvature (red *) which can complicate data analysis. 2D classes for this membrane protein should resemble projections in the red box. Box size = 170 Å2.

Figure 5.

Unusual micellular artifacts and structures. Some detergents (such as 2,2-didecylpropane-1,3-bis-β-D-maltopyranoside (LMNG) used in the example here) are prone to forming an array of micelle structures with different sizes, lengths and unusual curvature (red *) which can complicate data analysis. 2D classes for this membrane protein should resemble projections in the red box. Box size = 170 Å2.

Figure 6.

‘Projection contamination’ by non-physiological detergent/buffer driven interactions may cause processing issues. Pseudo D-Symmetrical complexes via membrane face A) WzzBst or via cytoplasmic domains B) McCorA in high Mg solutionThere is also a D form with a mix of oligomeric forms – the smaller oligomer is circled in yellow (bottom left. The purple surface render shows a 3D reconstruction from particles in A) with no masking to illustrate how the lower layer introduces noise and blur. ). Scale bars correspond to 200 Å in each panel.

Figure 6.

‘Projection contamination’ by non-physiological detergent/buffer driven interactions may cause processing issues. Pseudo D-Symmetrical complexes via membrane face A) WzzBst or via cytoplasmic domains B) McCorA in high Mg solutionThere is also a D form with a mix of oligomeric forms – the smaller oligomer is circled in yellow (bottom left. The purple surface render shows a 3D reconstruction from particles in A) with no masking to illustrate how the lower layer introduces noise and blur. ). Scale bars correspond to 200 Å in each panel.

Figure 7.

Protein insertion in the micelle can be non-uniform. A) shows 2D classes of McCorA showing asymmetric micelle insertion (yellow arrow) in DDM while the bar indicates some micelle averaging blur caused by variability. B) 2D Class averages of an MFS transporter in DDM micelles. Artifacts appear where in some micelles one protein is present (yellow class) whilst in others two proteins are present (red class – yellow arrows). C) 2D class averages of a membrane protein in LMNG show up/down insertion into the same micelle: extra-membrane domains are circled in broken yellow. Box sizes correspond to 271, 131 & 170 Å2 in A-C respectively.

Figure 7.

Protein insertion in the micelle can be non-uniform. A) shows 2D classes of McCorA showing asymmetric micelle insertion (yellow arrow) in DDM while the bar indicates some micelle averaging blur caused by variability. B) 2D Class averages of an MFS transporter in DDM micelles. Artifacts appear where in some micelles one protein is present (yellow class) whilst in others two proteins are present (red class – yellow arrows). C) 2D class averages of a membrane protein in LMNG show up/down insertion into the same micelle: extra-membrane domains are circled in broken yellow. Box sizes correspond to 271, 131 & 170 Å2 in A-C respectively.

Figure 8.

Variable micelle dimensions as a single issue of 3D heterogeneity. In the initial 3D classification of a MjCorA dataset (binned x4 to ~4.24 Å/pixel) there is very little conformational variability present in the protein; protein has a cc fit of 0.99 with resolution limited to ~6Å. At lower resolution sorting, micelle variability is a main source of heterogeneity in 3D samples and the micelle can vary in width by ~20 Å (~15%). Scale bar= 100Å.

Figure 8.

Variable micelle dimensions as a single issue of 3D heterogeneity. In the initial 3D classification of a MjCorA dataset (binned x4 to ~4.24 Å/pixel) there is very little conformational variability present in the protein; protein has a cc fit of 0.99 with resolution limited to ~6Å. At lower resolution sorting, micelle variability is a main source of heterogeneity in 3D samples and the micelle can vary in width by ~20 Å (~15%). Scale bar= 100Å.

Figure 9.

Unusual Symmetry effects of a purified Wzz sample. A subset of data from a supplemented dataset of the inner membrane protein Wzz demonstrates a clear C6 sub-arrangement of a dodecamer in A) 2D class averages (box = 200Å2) and B) the resulting 3D map with a fitted atomic model of the Wzz C6 ring (represented as ribbons). The position of transmembrane helices and inner membrane region is shown by the dotted lines. Scale Bar= 100Å.

Figure 9.

Unusual Symmetry effects of a purified Wzz sample. A subset of data from a supplemented dataset of the inner membrane protein Wzz demonstrates a clear C6 sub-arrangement of a dodecamer in A) 2D class averages (box = 200Å2) and B) the resulting 3D map with a fitted atomic model of the Wzz C6 ring (represented as ribbons). The position of transmembrane helices and inner membrane region is shown by the dotted lines. Scale Bar= 100Å.

Figure 10.

Symmetry strength through the C6 Wzz complex. Slices in different potions of the C6 Wzz structure show the complex has strong C6 deviations in loops and periplasmic helices, while the transmembrane helices within the micelle are only mild offset from a C12 ring. Scale Bar=100 Å.

Figure 10.

Symmetry strength through the C6 Wzz complex. Slices in different potions of the C6 Wzz structure show the complex has strong C6 deviations in loops and periplasmic helices, while the transmembrane helices within the micelle are only mild offset from a C12 ring. Scale Bar=100 Å.

Table 1.

Cryo-EM and image analysis details for sample preparation and data processing.

Table 1.

Cryo-EM and image analysis details for sample preparation and data processing.

| Sample |

MjCorA |

WzzBST

|

| Grid type |

C-Flat T40 – 200 or 300 Au mesh 1.3/1.2 |

Quantifoil – 300 Cu mesh 1.3/1.2 (chloroform washed) |

| Glow Discharge |

Emitek K100X: 25 mv for 30 sec glow discharge |

Solarus II 955: 20V/5V with 1:1 H2:O2 20 sec |

| Sample Volume |

3 ml |

| Grid blotting parameters |

4-6 secs in Vitrobot IV: 5 sec wait (100% humidity) at 220C |

2-4 secs in Vitrobot IV (95% humidity) at 220C |

| Microscope |

KRIOS G2 300 Kv |

| Sampling |

1.06 or 1.072 Å/px |

1.06 Å/px |

| Total dose |

40 e/ Å 2

|

60 e/ Å2

|

| Defocus (uM) |

-0.75 to –2.25 |

-1.0 to –2.25 |

| Images used |

25,000-36,000 total |

~5000 total |

| Camera |

Gatan K3 or F4i/Selectris |

Gatan K3 |

| MotionCorr |

512 or 1024 FFT box and 5x5 patches |

| CTF correction |

CTFFIND 4.1 [53] |

| CTF resolution |

30 Å, 2.5 Å (min,max) |

| Processing |

Relion 5.0 with BLUSH [3] |

| Symmetry |

C1, C6, C12 |

C1 & C5 |