1. Introduction

Managers frequently make strategic resource allocation decisions by choosing from multiple options under conditions of uncertainty. The behavioral theory of the firm offers valuable insights into these processes (Cyert & March, 1963). Some research within this framework conceptualizes market share as an indicator of overall firm performance, demonstrating that deviations from aspiration levels influence subsequent corporate actions such as inter-firm network formation (Baum et al., 2005), firm growth (Greve, 2008), and new product introduction (Joseph & Gaba, 2015). Separately, Greve (1998) treated regional market share as a reflection of market position, showing that changes in this position relative to aspiration levels drive subsequent organizational change. Such responses occur because boundedly rational managers often simplify their assessment of market performance, frequently converting it into measures of market share gains or losses (Cyert & March, 1963). Consequently, firms tend to be more motivated to initiate organizational change when their market share falls below their aspiration levels. Conversely, exceeding these aspirations can lead to satisficing with the current situation and reduced extent of change (Jordan & Audia, 2012). In parallel, research has indicated that shifts in regional market attractiveness can stimulate subsequent market expansion efforts by firms (Barreto, 2012).

Although existing research has separately examined the impacts of market share and market attractiveness on various firm behaviors, less attention has been paid to how these two critical factors interact to influence decisions regarding market retrenchment, particularly partial retrenchment from regional markets. The purpose of this study was to explore this interplay. Existing research grounded in the behavioral theory of the firm has largely focused on proactive behaviors such as risk-taking, innovative activities, mergers and acquisitions, and strategic change (Shinkle, 2011). However, with a few notable exceptions, such as Shimizu (2007), who analyzed the divestment of previously acquired units, and Vidal and Mitchell (2015), who examined how performance feedback influences complete and partial divestitures, the specific dynamics of retrenchment behaviors remain less understood. Allocating excessive resources to a market is undesirable because it can lead to inefficiencies (Arrfelt et al., 2013). However, managers may hesitate to withdraw from markets because such actions often compel them to acknowledge previous human or financial losses (Staw, 1976). Therefore, I argue that it is crucial to investigate which specific types of market information managers focus on, how they interpret that information, and, critically, how the combination of these interpretations shapes their market retrenchment decisions.

This study uses prefecture-level operational data from Japanese life insurance companies from 2006 to 2019 to test its hypotheses. Japan’s working-age population peaked in 1995 and has declined since, due to an aging society and a low birthrate. This demographic shift has been more pronounced in rural areas than in urban centers, prompting life insurance companies to reassess their nationwide sales office networks. Life insurance products primarily provide financial protection to bereaved families after the death of a primary earner; thus, a shrinking customer base reduces a region’s market attractiveness. This decline often leads life insurance companies to consolidate or close local sales offices, reflecting a form of market retrenchment. Therefore, during this period, Japan’s life insurance industry offers a suitable context for examining how market attractiveness and performance influence market retrenchment decisions.

The analysis reveals that the influence of changes in market share on market retrenchment is not uniform but contingent on the level of market attractiveness. This interplay leads to distinct retrenchment behaviors under varying market appeal and performance conditions. For example, in markets of average attractiveness, neither a market share gain nor loss had a clear effect on retrenchment. However, substantial losses and gains in market share are associated with less retrenchment in highly attractive markets. Conversely, in markets with low attractiveness, substantial losses and gains are associated with more retrenchment. These findings underscore that life insurance companies, when evaluating regional market retrenchment, consider not only changes in their market share but also the attractiveness of the specific region, leading to complex decision-making patterns.

2. Theory and Hypotheses

2.1. Market Attractiveness

Previous studies on the behavioral theory of the firm have extensively explored how organizational behavior is influenced by performance relative to both overall firm goals and specific action goals (Kim et al., 2015). Overall firm goals typically encompass broad indicators of corporate performance such as return on assets (ROA), stock price, and firm size. In contrast, specific action goals pertain to narrower metrics, including business unit outcomes, product sales performance, and market reactions to strategic announcements, such as acquisitions. Central to this research stream is the "performance feedback" mechanism, where firms assess their actual performance against aspiration levels—defined as "the smallest outcome that would be deemed satisfactory by the decision maker" (Schneider, 1992, p. 1053). Deviations from these aspiration levels significantly shape a firm’s exploratory behaviors and resource allocation strategies, prompting corrective actions in response to performance shortfalls or reinforcement strategies when performance exceeds expectations.

Building on this foundation, Barreto (2012) integrated insights from the behavioral theory of the firm and the attention-based view to emphasize the role of market attractiveness in organizational decisions regarding market expansion. In this context, market expansion refers to the scope and selection of multiple market opportunities that competing firms pursue. Barreto’s empirical findings demonstrate that market attractiveness, defined by regional demographic characteristics and the market presence of competitors, significantly drives a bank’s decisions to open new branches. Critically, this relationship exists independently of market-level performance considerations, underscoring that organizational search and selection behaviors are also stimulated by exogenous environmental factors. By demonstrating that the availability of attractive market opportunities independently fosters future-oriented organizational actions, Barreto’s study enriches traditional performance feedback frameworks by introducing external market conditions as influential stimuli in organizational decision-making processes.

According to the behavioral theory of the firm, organizations simplify complex decision-making processes by selectively focusing managerial attention on salient environmental cues that align with their core objectives (Cyert & March, 1963; Ocasio, 1997). Barreto (2012), building upon this foundation, emphasized that market attractiveness plays a crucial role in guiding organizational attention and strategic decisions. Specifically, firms are likely to allocate greater attention and resources to markets perceived as highly attractive because these markets align closely with a firm’s primary objective of profit maximization (Greve, 2008; Joseph & Gaba, 2015). Conversely, when market attractiveness diminishes, managerial attention is often drawn to the challenges posed by these less attractive markets (Ocasio, 1997), leading to strategic retrenchment and resource reallocation (Kuusela et al., 2017; Vidal & Mitchell, 2015). Therefore, a high level of market attractiveness acts as a strong incentive to maintain or enhance market presence, whereas a low level of market attractiveness prompts market retrenchment. Accordingly, I propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1. The higher the market attractiveness, the lower a firm’s market retrenchment.

2.2. Market Share Changes in Markets with Average Attractiveness

Some studies in the behavioral theory have used market share as a measure of overall firm performance (Baum et al., 2005; Joseph & Gaba, 2015). For instance, Baum et al. (2005) explored syndicate underwriting by investment banks. They found that organizations engage in problem-driven search when their market share falls below their aspiration level. Under these conditions, firms recognize that current approaches are insufficient to achieve their market share goals, prompting them to undertake riskier and more novel actions. Consequently, they tend to establish syndicate relationships with nonlocal banks in their social networks.

Baum et al. (2005) also demonstrated that surpassing market share aspiration levels leads organizations to engage in slack-driven search. Exceeding performance targets generates additional resources or organizational slack, allowing firms to tolerate higher risks and experiment with new approaches rather than strictly adhering to existing practices. This slack facilitates the formation of syndicate relationships with nonlocal banks, reflecting willingness to pursue novel opportunities and innovative behaviors.

Particularly relevant to the present study’s focus on firms operating in multiple local markets, Greve (1998) reported that radio stations were less likely to change their formats when their market share exceeded their aspiration level. When market share exceeds the aspiration level, radio stations tend to be satisfied with their performance. This satisfaction, in turn, increases participants’ incentive to maintain the status quo, diminishing their perceived need and motivation to undertake risky format changes. Conversely, when market share falls below the aspiration level, dissatisfaction with the current situation typically intensifies, thereby strengthening firms’ motivation to make changes to improve performance.

Building on these insights, I investigate how year-over-year changes in market share—specifically, market share losses and gains—influence a firm’s retrenchment decisions in markets with average attractiveness. One perspective, drawing from the behavioral theory of the firm and research on organizational problem-solving (Cyert & March, 1963; Greve, 1998), suggests that a market share loss is likely to be perceived by managers as a significant performance shortfall—a deviation from aspirations that demands corrective action. According to Greve (1998), managers often interpret such losses as problems localized to a specific market, prompting them to intensify efforts to regain their footing. This can manifest as increased investment, renewed marketing initiatives, or other forms of market expansion activities aimed at recovering the lost share. From this viewpoint, a market share loss would motivate actions contrary to retrenchment, thereby leading to a decrease in market retrenchment or even a renewed commitment to expansion. This response might be particularly salient if managers are influenced by loss aversion, becoming more risk-seeking in their attempts to recover previous losses (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979).

Conversely, an alternative perspective posits that a loss in market share can serve as a stark indicator to managers that the firm is facing a competitive disadvantage relative to its rivals in that particular market (Porter, 1980). This loss may be interpreted as evidence that the firm’s offerings are less appealing, its cost structure is uncompetitive, or its strategic positioning has weakened. In such a scenario, particularly in a market that offers only average attractiveness—meaning it lacks strong growth prospects or high profit potential to justify a difficult turnaround battle—managers might conclude that further investment would be uneconomical (Harrigan, 1980). Prudent resource allocation would then dictate a strategy for conserving resources by scaling back operations in underperforming markets. These resources could then be redeployed to more attractive or promising markets where the firm has a stronger competitive standing or perceives better opportunities (Bettis & Mahajan, 1985). Consequently, this interpretation would lead to an increase in market retrenchment as the firm seeks to cut losses and optimize its overall portfolio.

Given these two contrasting theoretical arguments, the specific context of a market with average attractiveness becomes crucial. In such markets, the strategic imperative is ambiguous. The market is not so unattractive to make immediate retrenchment the obvious choice, nor is it so attractive to unequivocally warrant an aggressive fight to regain share despite recent losses. Therefore, managers may find themselves facing a genuine dilemma. Some may adopt a problem-solving approach, viewing the share loss as a temporary setback to be overcome. Others may adopt the competitive disadvantage lens, viewing the loss as a signal to withdraw and reallocate.

These two distinct managerial interpretations and their corresponding strategic responses are both plausible in markets of average attractiveness. One interpretation pushes toward reduced retrenchment (or expansion), while the other pushes toward increased retrenchment. Consequently, their effects may counteract each other. The presence of these opposing forces could lead to a situation where, on average, a loss in market share does not result in a consistent, directional change in the firm’s propensity to retrench from that market. Therefore, I propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2.

When market attractiveness is at an average level, a loss in market share relative to the previous year leads to no change in market retrenchment.

Continuing this line of inquiry, I now shift my focus to the implications of a firm experiencing a gain in market share relative to the previous year, specifically within markets of average attractiveness. While market share losses in such contexts may elicit divergent managerial interpretations and thus ambiguous effects on retrenchment, I propose that a market share gain generates more consistent motivations that collectively argue against market retrenchment. This proposition is supported by two primary theoretical perspectives.

First, drawing upon the behavioral theory of the firm (Cyert & March, 1963) and the work of Greve (1998), a market share gain is likely to engender managerial satisfaction. In his study of radio stations, Greve (1998) found that organizations with market share above their aspiration levels were less likely to change their formats. This reluctance to change when performing well, a core tenet of aspiration-level adaptation, indicates that satisfaction with the current state and strategy is often fostered by exceeding performance targets. Managers content with their firm’s performance in a specific market would perceive less need for substantial strategic retrenchment. They are likely inclined to maintain the status quo to preserve the favorable performance trajectory. In a market with average attractiveness, incentives for aggressive expansion or immediate retrenchment are typically not overwhelming. In such settings, this satisfaction with a positive trend becomes particularly influential, reinforcing the decision to continue current operations rather than pursue the disruptive and resource-diverting act of market retrenchment.

Second, managers can interpret a gain in market share as a clear signal of a firm’s competitive advantage in that particular market (Porter, 1980). This improved standing relative to competitors might stem from more effective sales proposals, higher personnel efficiency in sales activities, stronger brand recognition in the region, and more effective strategic positioning. Even in a market that only has average attractiveness and lacks exceptional growth prospects or high profit potential, a demonstrated and growing competitive advantage is a valuable capability. Managers would likely view this as an opportunity to consolidate their position and further leverage their strengths. The positive performance signified by the market share gain may also generate organizational slack in the focal market (Cyert & March, 1963). In the context of a recognized competitive advantage, this slack is more likely to be reinvested to fortify the current market position rather than to fund retrenchment or geographic diversification away from a proven area of success, thereby enhancing profitability or stability. From this perspective, a reasonable response would be to reinforce success through continued commitment or even cautious expansion, rather than initiating market retrenchment and ceding hard-won ground.

Unlike the conflicting pressures potentially arising from market share loss, these two managerial responses to a market share gain—satisfaction derived from surpassing aspirations (Greve, 1998) and the recognition of a competitive advantage (Porter, 1980)—are not contradictory. The desire to maintain satisfactory performance, which is rooted in the behavioral theory of the firm, and the strategic imperative to capitalize on an evident competitive strength converge. This convergence provides robust motivation for managers to resist market retrenchment. In markets of average attractiveness, where the strategic path is not always clear, a positive performance signal, such as a market share gain, provides a compelling rationale to stay the course or even deepen commitment, thereby reducing the extent of retrenchment. Therefore, I propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3.

When market attractiveness is at an average level, a gain in market share relative to the previous year decreases market retrenchment.

2.3. Market Share Changes in Markets with High and Low Attractiveness

I now turn to situations in which market attractiveness is either high or low. In these contrasting contexts, I argue that a loss in market share relative to the previous year tends to have a more predictable—but opposite—effect on market retrenchment. The underlying level of market attractiveness substantially shapes this effect.

First, consider a firm that has experienced a loss in market share in a highly attractive market. As discussed in relation to Hypothesis 1, high market attractiveness provides a strong incentive for firms to maintain or strengthen their market presence, driven by factors such as favorable growth prospects and high profit potential. Building on the attention-based view (Ocasio, 1997, 2011). Barreto (2012) emphasized that attractive market opportunities can prompt forward-looking organizational actions independent of traditional performance feedback. The identification and assessment of such opportunities are central to strategic decision-making (Shane & Venkataraman, 2000; Christensen & Bower, 1996). When an insurance company loses market share in such an environment, managers are unlikely to interpret the loss as a signal to withdraw. Instead, consistent with the problem-driven search perspective in the behavioral theory of the firm (Cyert & March, 1963; Greve, 1998), managers may regard loss as a localized issue requiring corrective action. High market attractiveness justifies continued investment because long-term rewards are potentially substantial. Managers may respond by increasing marketing efforts, investing in service innovation, or improving operational efficiency to recover market share. As a result, a loss in market share is expected to decrease market retrenchment in such valuable and opportunity-rich markets.

In contrast, consider a firm that loses market share in a market with low attractiveness. As suggested by the logic underlying Hypothesis 1, low market attractiveness naturally orients firms toward market retrenchment. These markets often provide limited growth potential, low profit margins, or declining strategic value, making continued investments less appealing (Porter, 1980). The loss in market share in such contexts reinforces the rationale for withdrawal. It serves as further evidence of a competitive disadvantage or an eroding position in a market that already lacks strategic value (Harrigan, 1980). Moreover, managers may pay less attention to such markets because of their low attractiveness (Ocasio, 1997; Barreto, 2012), making withdrawal an even more likely outcome. Allocating resources to defend or regain market share in these contexts is likely to be seen as inefficient, particularly when more promising alternatives are available (Bettis & Mahajan, 1985). As such, resource reallocation favors market retrenchment to optimize the overall portfolio. Thus, loss in market share is expected to increase market retrenchment in low-attractiveness markets.

These contrasting responses indicate that the effect of market share loss on market retrenchment is systematically shaped by the market context. In highly attractive markets, strategic importance and potential returns motivate firms to persist. In contrast, in less attractive markets, particularly when performance declines, market retrenchment becomes a more reasonable and urgent course of action. Therefore, I propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4.

When market attractiveness is at a high (low) level, a loss in market share relative to the previous year decreases (increases) market retrenchment.

Building on the logic that market attractiveness moderates a firm’s response to market share changes, this study examines how a gain in market share affects market retrenchment under conditions of high or low market attractiveness.

First, when a firm gains market share in a highly attractive market, the rationale for decreasing market retrenchment is strengthened. High market attractiveness already provides a strong incentive for continued—or even increased—commitment (Porter, 1980; Barreto, 2012). A gain in market share further reinforces managerial perceptions of success and competitive advantage (Greve, 1998). This convergence of positive signals—an attractive market and improved firm performance—likely strengthens managerial confidence and increases their willingness to invest further to solidify or expand their position. Managers would have little reason to scale back operations and may instead pursue aggressive growth. Therefore, in highly attractive markets, a gain in market share is expected to significantly decrease market retrenchment, potentially more so than in markets with average attractiveness.

The situation differs significantly when a firm gains market share in a market with low attractiveness. While such a gain is a positive performance signal, its implications for retrenchment are more complex and may follow two distinct, though not mutually exclusive, managerial logics. One possibility is that managers interpret the gain through a harvest strategy lens (Harrigan, 1980). Acknowledging the market’s limited long-term prospects (Porter, 1980), firms may view the improved position as an opportunity to maximize short-term cash flows with minimal additional investment or to exit the market in a more controlled and profitable manner (Bettis & Mahajan, 1985). In this view, the gain does not signal a renewed commitment but rather facilitates a strategic withdrawal.

Alternatively, managers—constrained by bounded rationality and limited organizational resources (Cyert & March, 1963)—may reach a similar retrenchment decisions through different rationales. They conclude that the fundamental market outlook remains poor despite recent gains (Harrigan, 1980). If maintaining or building on this gain requires disproportionate effort or investment, the gain may highlight the opportunity cost of remaining in the market when more promising alternatives exist (Bettis & Mahajan, 1985). Rather than encouraging further investment, the gain could trigger increased market retrenchment to redirect resources to more attractive markets and avoid deeper involvement in a low-potential environment. Therefore, I propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 5.

When market attractiveness is at a high (low) level, a gain in market share relative to the previous year decreases (increases) market retrenchment.

Table 1 summarizes the hypotheses regarding the effects of market share changes and market attractiveness on market retrenchment. "Increases" and "Decreases" respectively indicate a hypothesized increase and decrease in market retrenchment. "No changes" indicates the hypothesis (H2) that market retrenchment will not change under specific conditions.

3. Methods

3.1. Research Setting

To test the hypotheses developed in this study, I employ firm-prefecture level panel data from life insurance companies operating in Japan between 2006 and 2019. The Japanese life insurance industry provides a particularly instructive context for examining how market share and attractiveness shifts influence market retrenchment decisions. Historically, life insurance distribution in Japan centered on face-to-face interactions, which cultivated strong relationships between sales staff and customers. During Japan’s high economic growth period, major life insurance companies aggressively expanded their physical presence, establishing extensive nationwide networks of sales offices. These companies adopted strategies that focused on office-based customer service and direct door-to-door sales. However, the economic landscape transformed following the collapse of Japan’s asset bubble in the early 1990s. This transformation accelerated depopulation in rural regions, primarily due to declining national birthrates and significant out-migration of younger individuals and families with children toward major urban centers. These population shifts have substantially eroded the attractiveness of many rural markets to life insurance companies. Specifically, these markets lost a core customer segment—households raising children—which typically have a higher demand for life insurance products. Consequently, life insurance companies that had once invested heavily in broad national sales networks began to strategically consolidate or close their sales offices in these less profitable regional markets to enhance operational efficiency. Therefore, the recent trajectory of the Japanese life insurance industry offers a rich empirical setting to analyze how declining regional market attractiveness influences firms’ market retrenchment strategies.

Data on sales activities in the 47 prefectures and firm-level data were obtained from the annual editions of the Statistics of Life Insurance Business, published by Hoken Kenkyujo Ltd. Because this publication is sold only in print, the authors manually digitized the data. In addition, demographic data for each prefecture were obtained from a database provided by the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications.

The initial dataset was acquired from 2006 to 2019. Data from boundary years 2006 and 2019 were used exclusively to calculate independent and dependent variables derived from year-over-year differences. This study investigates the extent to which life insurance companies, already established in a regional market, reduced their number of sales offices. To operationalize this focus on adjustments by incumbent firms with ongoing operations, I excluded firm-prefecture-year observations if a company had no sales offices in a given prefecture in year t or no sales offices in that same prefecture in year t+1. The latter condition includes instances of complete withdrawal from the prefecture. Given these criteria, the final analytical sample comprises firms that maintained at least one sales office in a specific prefecture in both year t and the subsequent year t+1. This sample consists of 4,223 firm-prefecture-year observations, representing 16 life insurance companies across Japan’s 47 prefectures, covering the period from 2007 to 2018.

3.2. Variables

The dependent variable in this study is market retrenchment, measured as the decrease in the number of sales offices (a positive integer) operated by the focal life insurance company within each focal prefecture from year t to year t+1.

The independent variables are market attractiveness, share gain, and loss. Following Barreto (2012), market attractiveness is calculated based on the ratio of demand to supply in each prefecture. For the demand side, I used the number of households (in thousands). The number of households is a more appropriate measure than population when assessing the demand for life insurance across prefectures. Life insurance policies are typically purchased at the household level, primarily by breadwinners who seek to provide financial protection for their dependents. Furthermore, households better represent the decision-making unit for financial products such as life insurance. In contrast to population figures, which include children and other individuals who generally do not make purchasing decisions, household counts more accurately reflect the number and characteristics of potential life insurance customers. For the supply side, I used the number of sales offices operated by all competing life insurance companies (i.e., all life insurance companies excluding the focal firm). This market attractiveness variable was then standardized to facilitate the interpretation of the analysis results.

To construct the two independent variables related to market share, I first calculated the market share (%) of the focal life insurance company in each prefecture. This was done by dividing the number of insurance contracts by the total number of insurance contracts held by all life insurance companies in that prefecture and then multiplying the result by 100.

Market share gain and

loss are derived from a spline function of the change in market share from year t-1 to year t. These can be represented by the following equations (Marsh & Cormier, 2001):

This spline function approach allows for separate examination of the effects of positive changes (gains) and negative changes (losses) in market share. This approach, which uses the previous year’s performance as a reference point, is consistent with the concept of historical aspiration level within the behavioral theory of the firm, and a similar approach can be found in Audia and Brion (2007).

In this study, I include several control variables at the firm-prefecture level are included to control for the competitive environment of the local market. Market households represents the number of households (in thousands) in the focal prefecture. Market competition density is the number of sales offices maintained by competing life insurance companies in a prefecture. Own local density is the number of focal life insurance company sales offices in the focal prefecture. Prefecture size is measured as the land area of the prefecture (in square kilometers) divided by 100,000.

To control for individual firm characteristics, I also incorporate several firm-level variables. ROA is calculated as the current year’s surplus divided by total assets. Firm slack is measured as the average of three standardized slack variables: absorbed slack, unabsorbed slack, and potential slack (Greve, 2003). Absorbed slack is the ratio of operating expenses to premium income. Unabsorbed slack is the ratio of cash, deposits, and call loans to total liabilities. Potential slack is the ratio of debt to equity. Firm size is the natural logarithm of total premium income, which is an appropriate measure of firm size for insurance companies (Greve, 2008). Geographic diversification is measured as one minus the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI). The HHI is a common measure of market concentration calculated by squaring the market share of each firm operating in a market and then summing the resulting numbers. A higher HHI indicates greater market concentration; consequently, a lower value for the geographic diversification measure indicates less diversification.

The initial strategy for managing time-specific effects was to incorporate a full set of year dummy variables. However, this approach resulted in Stata not reporting the Wald chi-squared statistic for overall model significance. This is a common issue when the estimated parameters are numerous relative to the data clusters and is a documented concern with clustered standard errors (Cameron and Miller, 2015). In my study, employing numerous year dummies with the chosen panel data model and 16 firm clusters substantially increased the parameter count. This compromised the asymptotic Wald test’s reliability, a known issue for statistical methods that account for within-cluster data correlation (Liang and Zeger, 1986; Hardin and Hilbe, 2002).

This high parameter count, which led to the unreported Wald chi-squared statistic, prompted a more parsimonious approach to modeling temporal trends. Consequently, the individual year dummies are replaced with a continuous industry clock variable constructed by subtracting the base year 2007 from the year variable. This reduces the model parameters while controlling for secular time trends. Dowell and Killaly (2009), who analyze similar firm-market-year observations, also use an industry clock.

Similarly, including firm-specific dummies to control for unobserved time-invariant firm heterogeneity also led to the non-reporting of the Wald chi-squared statistic, likely because these additional dummies substantially increased the number of parameters relative to clusters. Consequently, firm-specific dummies were excluded from the final model. The model uses standard errors clustered by firm to address potential within-firm error correlation and heteroskedasticity (Liang and Zeger, 1986). However, excluding firm-specific dummies means that estimated coefficients may suffer omitted variable bias if unobserved time-invariant firm characteristics correlate with the included explanatory variables (Wooldridge, 2010). This limitation warrants consideration when interpreting the results.

3.3. Model

To address potential multicollinearity within the dataset, I calculated the variance inflation factors (VIFs) using ordinary least squares (OLS) models, consistent with Barreto (2012). My analysis identified two pairs of control variables for which the VIFs significantly surpassed the commonly accepted benchmark of 10 (Kennedy, 2008). The first pair included market households and market competition density, and the second consisted of firm size and geographic diversification. These sets of variables exhibited strong intercorrelation, which introduced multicollinearity issues. Therefore, I applied an orthogonalization technique. Specifically, I employed a modified Gram-Schmidt procedure was employed using the orthog command in Stata. After this procedure, the dataset was then reevaluated for multicollinearity. Subsequent VIF calculations confirmed that all variable VIFs were reduced to acceptable levels.

The dependent variable in this study is the count variable. While the Poisson distribution is a common starting point for modeling count data, it assumes that the mean and variance of the distribution are equal (equidispersion) (Cameron & Trivedi, 2013). However, count data in practice often exhibit overdispersion (variance greater than the mean) or underdispersion (variance less than the mean). In my analysis, the Stata output for the Generalized Estimating Equations (GEEs) model indicated that the dispersion parameter was less than unity, suggesting that the equidispersion assumption of the Poisson model was not met. This finding indicates a potential underdispersion of the data. The negative binomial distribution provides a more flexible alternative as it can account for such departures from equidispersion by including an additional parameter to model the dispersion (Hilbe, 2011). Therefore, to appropriately model the count nature of the dependent variable and address the observed dispersion, a negative binomial distribution was employed for the analysis.

My research uses panel data on insurance company market retrenchment across multiple prefectures and employs negative binomial regressions with GEEs (Hubbard et al. 2010). While various control variables are incorporated, it is crucial to address potential remaining within-firm correlations across prefectures. GEEs are well-suited for this because they allow for an estimated, rather than assumed, error-term correlation matrix, unlike models that assume an identity matrix typical of independent observations (Liang & Zeger, 1986); this approach also helps in considering spatial dependence. Following previous studies (Barreto, 2012; Rhee & Haunschild, 2006), I conducted negative binomial regressions with GEEs, specifying an exchangeable correlation matrix (Ballinger, 2004). This approach manages any remaining nonindependence of errors across markets for the same insurance company, reflecting the potential correlation of observations for the same insurance company within a given year. Furthermore, the Huber-White robust variance estimator ensures valid standard errors even if the specified correlation structure does not perfectly capture actual within-group correlations (Huber, 1967; White, 1980).

In analyzing my panel data with GEE using Stata's xtgee command with the family(nbinomial), link(log), and i(firm) options, I initially considered specifying a working correlation structure of corr(exchangeable). This choice is based on the theoretical expectation that observations within the same firm over time are likely to exhibit some degree of consistent, nonzero correlation. However, the model that employed the corr(exchangeable) structure failed to converge. To address this issue, I adopted a more simplified working correlation structure, corr(independent), which assumes no correlation between observations within the same firm after accounting for covariates. This specification allowed the model to converge.

I employed the vce(robust) option to obtain the robust (Huber-White/sandwich) standard errors (Huber, 1967; White, 1980). The use of robust standard errors in the GEE provides valid inferences for the estimated coefficients and their standard errors even if the chosen working correlation structure is misspecified, provided that the mean model itself is correctly specified. Therefore, although the corr(independent) structure assumes no within-firm correlation, my inferences are robust to potential deviations from this assumption. Although the vce(robust) option ensures the consistency of the parameter estimates and the validity of the standard errors, the choice of a working correlation structure can affect the estimation efficiency. If the true underlying correlation structure is indeed closer to corr(exchangeable), using corr(independent) might result in less efficient estimates (that is, larger standard errors) compared to what could have been achieved with a correctly specified and converged corr(exchangeable) model. Nevertheless, achieving model convergence is a prerequisite for obtaining interpretable results, and the corr(independent) structure, in conjunction with robust standard errors, provides a valid and practical approach in this instance.

4. Results

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics and Pearson’s correlations for all variables (N = 4223). The average

market retrenchment was 0.763 (SD = 2.065), indicating varied retrenchment activity.

Market retrenchment shows significant correlations (

p < 0.05, |r| > 0.029). It is positively correlated with

market households (r = 0.412),

own local density (r = 0.617), and

market attractiveness (r = 0.083). Conversely, it is negatively correlated with

market share loss (r = −0.073),

market competition density (r = −0.219), and

industry clock (r = −0.109). The correlation with

market share gain (r = −0.028) is not statistically significant.

Table 3 presents the results of the negative binomial regression models with GEEs used to predict

market retrenchment. Model 1 only included control variables (Wald chi-squared = 3337.22). Model 2 introduces only

market attractiveness as an independent variable, showing a statistically significant improvement in model fit (Wald chi-squared = 3687.22; the change in Wald chi-squared, ΔWald chi-squared = 350.00, for Δdf = 1, is significant,

p < 0.01) compared to Model 1. Model 3 adds only the two independent variables from the spline function related to

market share change (

market share loss and

gain) to Model 1, also demonstrating a statistically significant improvement in fit (Wald chi-squared = 5318.94; ΔWald chi-squared = 1981.72, for Δdf = 2, is significant,

p < 0.01). Model 4 includes market

attractiveness and share change variables. This model shows a statistically significant improvement in fit over Model 2 (to which

market share change variables were added: ΔWald chi-squared = 2300.67, for Δdf = 2, is significant,

p < 0.01) and over Model 3 (to which

market attractiveness was added: ΔWald chi-squared = 668.95, for Δdf = 1, is significant,

p < 0.01), with a Wald chi-squared of 5987.89. Finally, Model 5, the full model, includes the interaction terms between

market share change and

market attractiveness. The addition of these interaction terms resulted in a statistically significant improvement in model fit compared to Model 4 (Wald chi-squared = 92977.05; a joint Wald chi-squared test of the interaction terms, Wald chi-squared(2) = 19.41,

p < 0.01, confirms this improvement). The Wald chi-squared statistics were significant for all models (

p < 0.01), indicating good overall model fit and progressive improvement as key variables and interactions are added (Jaccard & Turrisi, 2003).

Hypothesis 1 predicts that higher market attractiveness is associated with lower market retrenchment. This hypothesis was tested using Models 2 and 4. In Model 2, the coefficient for market attractiveness is positive and statistically significant (β = 0.124, p < 0.05). Similarly, in Model 4, the coefficient for market attractiveness remained positive and statistically significant (β = 0.123, p < 0.05). However, the sign of the coefficient is positive in both models, which is contrary to the prediction of Hypothesis 1. This result suggests that higher market attractiveness is associated with greater market retrenchment. Therefore, Hypothesis 1 is not supported.

Hypothesis 2 proposes that when market attractiveness is at an average level, a previous-year loss in market share leads to no change in market retrenchment. This hypothesis concerns the effect of market share loss when market attractiveness is at its mean. In Model 4, the coefficient for market share loss is 0.059 and is not statistically significant (p > 0.10). For confirmation, Model 3, which does not include market attractiveness, also shows a nonsignificant coefficient for market share loss (β = 0.064, p > 0.10). In Model 5, which includes the interaction term, the main effect of market share loss (−0.038, p > 0.10) specifically represents this effect at average market attractiveness (where the standardized market attractiveness variable is 0). The nonsignificance is consistent with the prediction of no change, thus supporting Hypothesis 2.

Hypothesis 3 posits that when market attractiveness is at an average level, a previous-year gain in market share decreases market retrenchment. This hypothesis concerns the effect of market share gain when market attractiveness is at its mean. Model 4, which includes market attractiveness as a control, shows that the coefficient for market share gain is −0.202 and statistically significant (p < 0.01). Model 3, which does not include market attractiveness, also shows a significant negative coefficient for market share gain (β = −0.204, p < 0.01). However, in Model 5, which includes the interaction term, the main effect of market share gain (−0.073, p > 0.10) represents this effect at average market attractiveness (where the standardized market attractiveness variable is 0), and this specific coefficient is not significant. Although Models 3 and 4 (which do not account for interaction effects) suggested a significant negative relationship, the findings from Model 5, which is more comprehensive as it accounts for interaction effects, do not provide clear support for a direct negative effect of market share gain on average market attractiveness. Therefore, I conclude that Hypothesis 3 is not supported.

Hypothesis 4 concerns the moderating effect of market attractiveness on the relationship between market share loss and market retrenchment. It was predicted that when market attractiveness is high, a loss in market share decreases market retrenchment, and when it is low, a loss in market share increases market retrenchment. This hypothesis was tested using Model 5. The interaction term market share loss × market attractiveness in Model 5 is positive and significant (β = 0.135, p < 0.01). To interpret this interaction, for high market attractiveness (e.g., +1 SD), the effect of a one-unit loss in market share (represented by a value of −1 for the market share loss variable) on market retrenchment is calculated as (−0.038 * −1) + (0.135 * −1 * 1) = 0.038 0.135 = −0.097. This negative effect indicates that in highly attractive markets, loss of market share decreases market retrenchment, supporting the first part of Hypothesis 4. Conversely, for low market attractiveness (e.g., −1 SD), the effect of a one-unit loss in market share on market retrenchment is (−0.038 * −1) + (0.135 * −1 * −1) = 0.038 + 0.135 = 0.173. This positive effect indicates that in markets with low market attractiveness, loss of market share leads to an increase in market retrenchment, supporting the second part of Hypothesis 4. Collectively, these findings support Hypothesis 4. The collective significance of these interaction terms, confirmed by the joint Wald test noted earlier when discussing Model 5, lends overall support to the hypothesized moderating role of market attractiveness.

Hypothesis 5 addresses the moderating effect of market attractiveness on the relationship between market share gain and market retrenchment. It was predicted that when market attractiveness is high, a gain in market share decreases market retrenchment, and when it is low, a gain in market share increases market retrenchment. This hypothesis was tested using Model 5. The interaction term market share gain × market attractiveness in Model 5 is negative and significant (β = −0.115, p < 0.01). To interpret this interaction, for high market attractiveness (e.g., +1 SD), the effect of a one-unit gain in market share (represented by a value of +1 for the market share gain variable) on market retrenchment is (−0.073 * 1) + (−0.115 * 1 * 1) = 0.073 − 0.115 = −0.188. This negative effect indicates that in highly attractive markets, a market share gain decreases market retrenchment, supporting the first part of Hypothesis 5. Conversely, for low market attractiveness (e.g., −1 SD), the effect of a one-unit gain in market share on market retrenchment is (−0.073 * 1) + (−0.115 * 1 * −1) = −0.073 + 0.115 = 0.042. This positive effect indicates that in markets with low market attractiveness, a market share gain leads to an increase in market retrenchment, supporting the second part of Hypothesis 5. Thus, Hypothesis 5 is supported. As mentioned under Hypothesis 4, the joint Wald chi-square test of the interaction terms further supports the overall significance of these moderating effects.

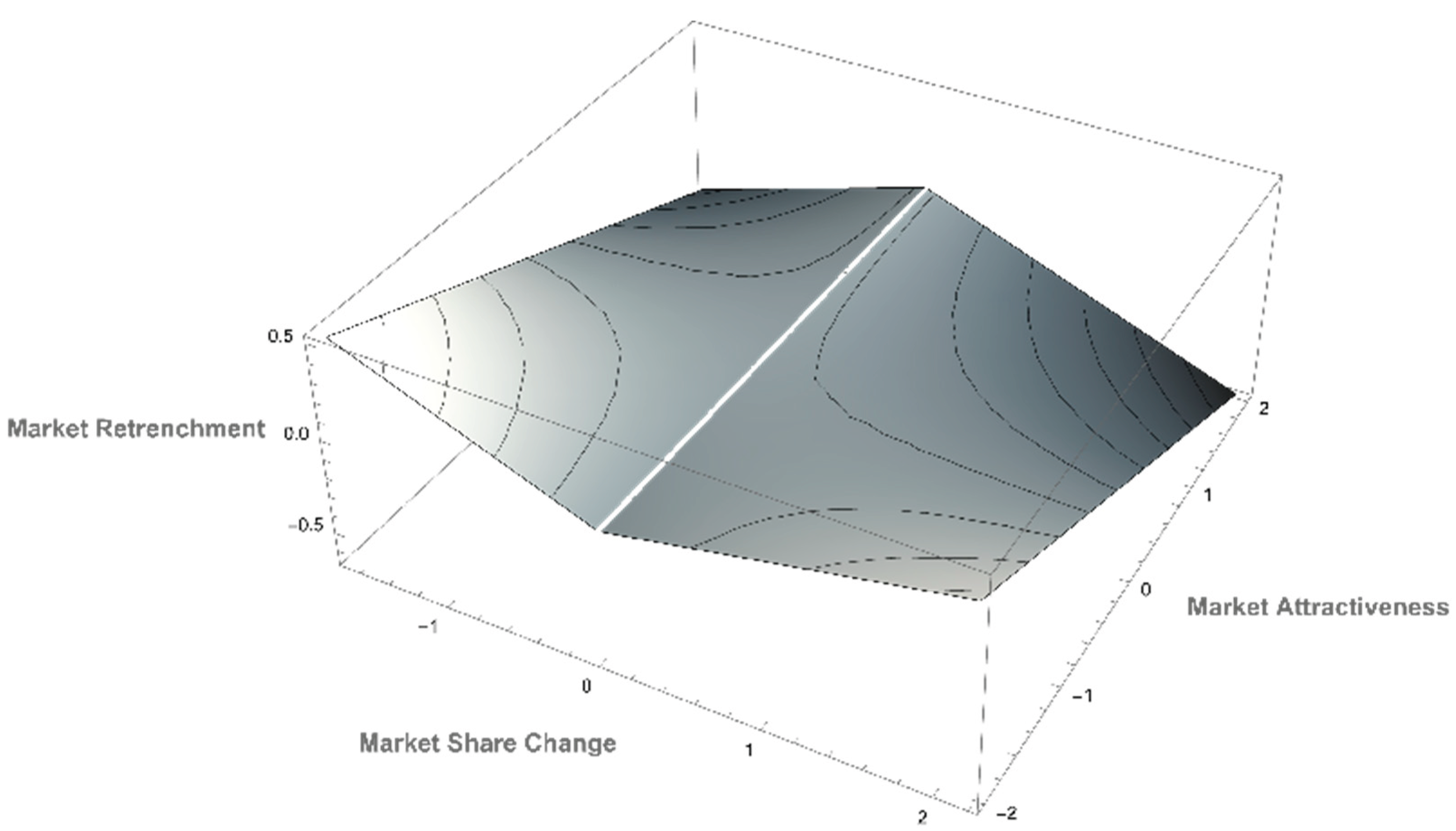

Figure 1 visually represents the interactive effects of

market share change and

attractiveness on

market retrenchment, as detailed in the results for Hypotheses 4 and 5. The three-dimensional plot illustrates how the predicted values of

market retrenchment (vertical axis) are shaped by the interplay of two horizontal axes:

market share change and

market attractiveness. The "

market share change" axis (one horizontal dimension) distinguishes between market share losses (negative values) and gains (positive values). This axis covers a range of approximately ±2 standard deviations (SD) of

market share change, where a value of 0 indicates no change in market share from the previous year. For example, a value of −1 signifies a 1% decrease in market share from the previous year. The "

market attractiveness" axis (the other horizontal dimension) indicates the SD from the mean. A value of 0 represents average

market attractiveness, whereas values such as +2 or 2 indicate

market attractiveness with two SD above or below the average, respectively.

Specifically, the plot’s surface demonstrates that when market attractiveness is high (e.g., at +2 SD), loss and gain in market share (e.g., moving toward −2 SD or +2 SD on the market share change axis) are associated with a decrease in predicted market retrenchment. This trend is shown by the downward slope of the surface as changes in market share move away from zero at high levels of market attractiveness. Therefore, in highly attractive markets, a larger magnitude of market share change (either loss or gain) corresponds to less market retrenchment. Conversely, when market attractiveness is low (e.g., at −2 SD), both loss and gain in market share are associated with an increase in predicted market retrenchment. This trend is depicted by the upward slope of the surface as changes in market share move away from zero at low attractiveness levels. Consequently, in markets with low attractiveness, a larger magnitude of market share change (either loss or gain) leads to more market retrenchment.

At average levels of market attractiveness (i.e., 0 SD from the mean), the relationship between market share change and market retrenchment appears nearly flat. This observation aligns with the statistical analysis, which indicates that in markets with average attractiveness, neither market share losses nor gains significantly influence market retrenchment decisions.

Finally, when

the change in market share is near zero, the surface of the plot is nearly flat regardless of

the market attractiveness. This indicates that if there is little change in market share,

market attractiveness has minimal influence on

market retrenchment decisions. Overall,

Figure 1 encapsulates the core finding that the predicted level of an insurance company’s market retrenchment is contingent upon the combined influence of

market share changes and the attractiveness of the market in question.

5. Discussion

This study investigates how changes in regional market share and market attractiveness influence a life insurance company’s decision regarding market retrenchment from regional markets, drawing upon the behavioral theory of the firm. The findings offer significant contributions to our understanding of strategic corporate decision-making, particularly in the context of market withdraw.

The primary contribution of this research is its application and extension of the behavioral theory of the firm to the specific context of Japanese life insurance companies’ market retrenchment. This moves beyond simplistic views of firms reacting to market share changes or market attractiveness in isolation. This study empirically demonstrates that life insurance companies make market retrenchment decisions by concurrently considering their performance (market share change) within a regional market and the attractiveness of that market. This integrated perspective is crucial because the results show that the influence of market share change on retrenchment is significantly shaped by the level of market attractiveness, and this influence is reciprocal. For instance, in highly attractive markets, the greater the market share change (whether a loss or a gain), the more significant the market retrenchment. This is because a substantial loss in such a prized market is considered to trigger intensive problemistic search and resource mobilization aimed at recovery, as the market’s high value justifies the effort to defend or reclaim share. Conversely, a substantial gain is thought to reinforce the market’s perceived value and the firm’s competitive strength, encouraging further commitment and investment in slack resources to consolidate the successful position rather than considering withdrawal. In contrast, in markets with low market attractiveness, the greater the fluctuation in market share (whether a loss or a gain), the more market retrenchment was promoted. It is considered that a significant loss in an unpromising market likely accelerates retrenchment because further investments are not justified. Moreover, a significant gain in such a market is also thought to lead to increased retrenchment; this may reflect a "harvest and exit" strategy where temporary gains are capitalized upon before a planned withdrawal, or a strategic decision that resources are better allocated elsewhere despite the gain, given the market’s fundamental unattractiveness.

Second, this study builds upon and extends previous research, Barreto (2012), who established that firms respond to market attractiveness when making market expansion decisions. My research contributes by examining the retrenchment context and by identifying regional-level performance—specifically, market share change—as a key moderating factor in how market attractiveness influences retrenchment decisions. While Barreto (2012) highlighted the direct pull of attractive markets for growth, my findings reveal a more complex dynamic for retrenchment: the strategic value of a market (attractiveness) interacts with the firm’s actual success or failure (market share change) within it to determine the extent of withdraw. Contrary to the initial hypothesis, higher market attractiveness, in isolation, positively influenced an increase in market retrenchment. However, when market share performance is considered, the role of attractiveness becomes clearer. Specifically, when market attractiveness is high, greater fluctuations in market share tend to make insurance companies want to stay. Conversely, when market attractiveness is low, greater fluctuations in market share tend to make it more prone to retrenchment.

Third, by adopting an analytical focus that differs from previous research, this study offers new insights into the behavioral theory of the firm and contributes to its theoretical development. Much of the existing literature within this theoretical tradition has concentrated on performance feedback relative to overall firm goals. This study, however, highlights the existence and significance of performance feedback related to a more specific action goal—in this case, sales performance within a particular regional market. I demonstrate not only that this regional-level performance feedback influences strategic actions like market retrenchment but also that market attractiveness acts as a crucial moderator of this feedback. The finding that in markets of average attractiveness, market share loss did not significantly lead to retrenchment, while share gain also did not significantly decrease it, suggests a zone of managerial ambiguity where the specific action goal feedback (share change) is not strongly guided by market context, potentially leading to inconsistent responses. This contrasts sharply with high or low-attractiveness markets where the moderating effect of attractiveness provides a clearer direction. This focus on specific action goals and their contextual moderation offers a more granular understanding of how firms adapt and make strategic choices.

These results extend the behavioral theory of the firm by highlighting how the environmental context (i.e., market attractiveness) systematically shapes a life insurance company’s response to performance feedback (i.e., market share change at the regional level). It moves beyond a simple problemistic versus slack search dichotomy by showing that the same performance signal (loss or gain) can lead to opposite strategic actions (less vs. more retrenchment) depending on the attractiveness of the market. Managers do not react to market share changes in a vacuum; they combine this internal performance indicator with external market assessments to make complex resource allocation decisions like market retrenchment.

From a practical standpoint, by recognizing the behavioral tendencies of competitors and a firm’s own company in regional market retrenchment strategies, as revealed by this study, more rational and potentially counter-cyclical decision-making can be achieved. For instance, the finding that gaining market share in a region with low market attractiveness typically prompts corporate market retrenchment—perhaps due to a "harvest and exit" mentality or a perception that resources are better used in more attractive markets—highlights a potential behavioral bias. A purely rational assessment, however, might suggest that remaining in the market could be the more logical long-term decision if the cost of maintaining or even slightly growing that share is low. This holds true even if the market is not highly attractive, provided the company has a competitive advantage and the market still contributes positively to overall profitability. Understanding that competitors might also be prone to such "behavioral" retrenchment in unattractive markets could even present an opportunity to consolidate a position with relatively little competitive pressure. Managers should therefore be cautious about automatically following industry trends or internal heuristics without a deeper, context-specific rational analysis, as behavioral factors might unduly influence decisions, either by prompting withdrawal or, conversely, by causing hesitation to exit.

This study has several limitations that open avenues for future research. First, the analysis is based on data from a single industry (Japanese life insurance companies) in a single country. Future research could examine whether these findings can be generalized to other industries and national contexts with different competitive dynamics and institutional environments. Second, although I used market share change as a key performance indicator, the reasons behind these changes (e.g., competitive actions, changes in customer preferences, regulatory shifts) were not explicitly modeled. Investigating managers’ attributions of changes in market share could provide deeper insights. Third, market retrenchment was measured by the reduction in the number of sales offices. Future studies could explore other forms or degrees of retrenchment, such as reducing product lines, marketing expenditures, or a complete market exit. Finally, while the behavioral theory of the firm provides a strong theoretical lens, directly measuring managerial cognitions, aspirations, and decision-making heuristics would offer a more fine-grained understanding of the mechanisms at play.

6. Conclusions

This study significantly contributes to the understanding of market retrenchment by applying and extending the behavioral theory of the firm. This study demonstrates three key points. First, life insurance companies’ retrenchment decisions are a function of the interplay between regional market share changes and market attractiveness. Second, it underscores how regional performance moderates actions driven by market attractiveness. Third, it highlights the importance of performance feedback on specific action goals, moderated by the market context. The findings underscore that managers’ responses to performance feedback are highly contingent on the perceived strategic value of the market, leading to complex and sometimes counterintuitive strategic choices.

Funding

This research was funded by the KAMPO Foundation under its FY 2020 Research Grant program.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data analyzed in this study were manually digitized by the author from printed publications legally purchased from Hoken Kenkyujo Ltd. (Japan). The publisher ceased operations as of May 2, 2024 and was no longer in business. Therefore, no official data repositories or permission sources are currently available. Access to these original printed publications may be limited to academic libraries or specialized archives.

Acknowledgments

I gratefully acknowledge the generous financial support provided by the KAMPO Foundation. I also wish to recognize the invaluable publishing contribution of Hoken Kenkyujo Ltd.—now, regrettably, no longer in operation—whose publication Statistics of Life Insurance Business served as a crucial data source for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| VIF |

Variance Inflation Factors |

| OLS |

Ordinary Least Squares |

| GEE |

Generalized Estimating Equations |

| ROA |

Return on Assets |

| HHI |

Herfindahl-Hirschman Index |

| SD |

standard deviations |

References

- Arrfelt, M.; Wiseman, R.M.; Hult, G.T.M. Looking Backward Instead of Forward: Aspiration-Driven Influences on the Efficiency of the Capital Allocation Process. Acad. Manag. J. 2013, 56, 1081–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballinger, G.A. Using Generalized Estimating Equations for Longitudinal Data Analysis. Organ. Res. Methods 2004, 7, 127–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, W.P.; Sorenson, O. The Red Queen in organizational creation and development. Ind. Corp. Chang. 2002, 11, 289–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, J.A.C.; Rowley, T.J.; Shipilov, A.V.; Chuang, Y.-T. Dancing with Strangers: Aspiration Performance and the Search for Underwriting Syndicate Partners. Adm. Sci. Q. 2005, 50, 536–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettis, R.A.; Mahajan, V. Risk/Return Performance of Diversified Firms. Manag. Sci. 1985, 31, 785–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, R.; Blau, P.M. Inequality and heterogeneity: A primitive theory of social structure (Vol. 7); Free Press: New York, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Bourgeois, L.J. ; Iii On the Measurement of Organizational Slack. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1981, 6, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, A.C.; Miller, D.L. A Practitioner’s Guide to Cluster-Robust Inference. J. Hum. Resour. 2015, 50, 317–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, A.C.; Trivedi, P.K. Regression analysis of count data; Cambridge university press, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, C.M.; Bower, J.L. Customer power, strategic investment, and the failure of leading firms. Strateg. Manag. J. 1996, 17, 197–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyert, R.M.; March, J.G. A behavioral theory of the firm; Prentive-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Dowell, G.; Killaly, B. Effect of Resource Variation and Firm Experience on Market Entry Decisions: Evidence from U.S. Telecommunication Firms' International Expansion Decisions. Organ. Sci. 2009, 20, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greve, H.R. Performance, Aspirations, and Risky Organizational Change. Adm. Sci. Q. 1998, 43, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greve, H.R. A Behavioral Theory of R&D Expenditures and Innovations: Evidence from Shipbuilding. Acad. Manag. J. 2003, 46, 685–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greve, H.R. A Behavioral Theory of Firm Growth: Sequential Attention to Size and Performance Goals. Acad. Manag. J. 2008, 51, 476–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardin, J.W.; Hilbe, J.M. Generalized estimating equations; chapman and hall/CRC, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Harrigan, K.R. Strategy Formulation in Declining Industries. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1980, 5, 599–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilbe, J.M. Negative binomial regression; Cambridge University Press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard, A.E.; Ahern, J.; Fletscher, N.L.; Van der Laan, M.; Lippman, S.A.; Jewell, N.; Bruckner, T.; Satariano, W.A. To GEE or not to GEE: Comparing Population average and mixed models for estimating the associations between neighborhood risk factors and health. Epidemiology 2010, 21, 467–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huber, P.J. (1967). The behavior of maximum likelihood estimates under nonstandard conditions. Proceedings of the fifth Berkeley symposium on mathematical statistics and probability, volume 1: statistics.

- Jaccard, J.; Turrisi, R. Interaction effects in multiple regression; Sage, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, A.H.; Audia, P.G. Self-Enhancement and Learning from Performance Feedback. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2012, 37, 211–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, J.; Gaba, V. The fog of feedback: Ambiguity and firm responses to multiple aspiration levels. Strat. Manag. J. 2014, 36, 1960–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D.; Tversky, A. Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica 1979, 47, 263–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, P. A guide to econometrics; John Wiley & Sons, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.-Y.; Finkelstein, S.; Haleblian, J. All Aspirations are not Created Equal: The Differential Effects of Historical and Social Aspirations on Acquisition Behavior. Acad. Manag. J. 2015, 58, 1361–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuusela, P.; Keil, T.; Maula, M. Driven by aspirations, but in what direction? Performance shortfalls, slack resources, and resource-consuming vs. resource-freeing organizational change. Strat. Manag. J. 2016, 38, 1101–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, K.-Y.; Zeger, S.L. Longitudinal Data Analysis Using Generalized Linear Models. Biometrika 1986, 73, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocasio, W. Towards an Attention-Based View of the Firm. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 187–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocasio, W. Attention to Attention. Organ. Sci. 2011, 22, 1286–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. Competitive strategy: Techniques for analyzing industries and competition (Vol. 300); Free Press, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Rhee, M.; Haunschild, P.R. The liability of good reputation: A study of product recalls in the U.S. automobile industry. Organ. Sci. 2006, 17, 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, S.L. Framing and conflict: Aspiration level contingency, the status quo, and current theories of risky choice. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 1992, 18, 1040–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shane, S.; Venkataraman, S. The Promise of Entrepreneurship as a Field of Research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2000, 25, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, K. Prospect Theory, Behavioral Theory, and the Threat-Rigidity Thesis: Combinative Effects on Organizational Decisions to Divest Formerly Acquired Units. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 1495–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinkle, G.A. Organizational Aspirations, Reference Points, and Goals. J. Manag. 2011, 38, 415–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staw, B.M. Knee-deep in the big muddy: a study of escalating commitment to a chosen course of action. Organ. Behav. Hum. Perform. 1976, 16, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, E.; Mitchell, W. Adding by Subtracting: The Relationship Between Performance Feedback and Resource Reconfiguration Through Divestitures. Organ. Sci. 2015, 26, 1101–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, H. A Heteroskedasticity-Consistent Covariance Matrix Estimator and a Direct Test for Heteroskedasticity. Econometrica 1980, 48, 817–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wooldridge, J.M. Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data; MIT press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).