Submitted:

01 July 2025

Posted:

17 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Patient Recruitment and Ethics

Vaccine Production and Application

Quality of Life Assessment

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

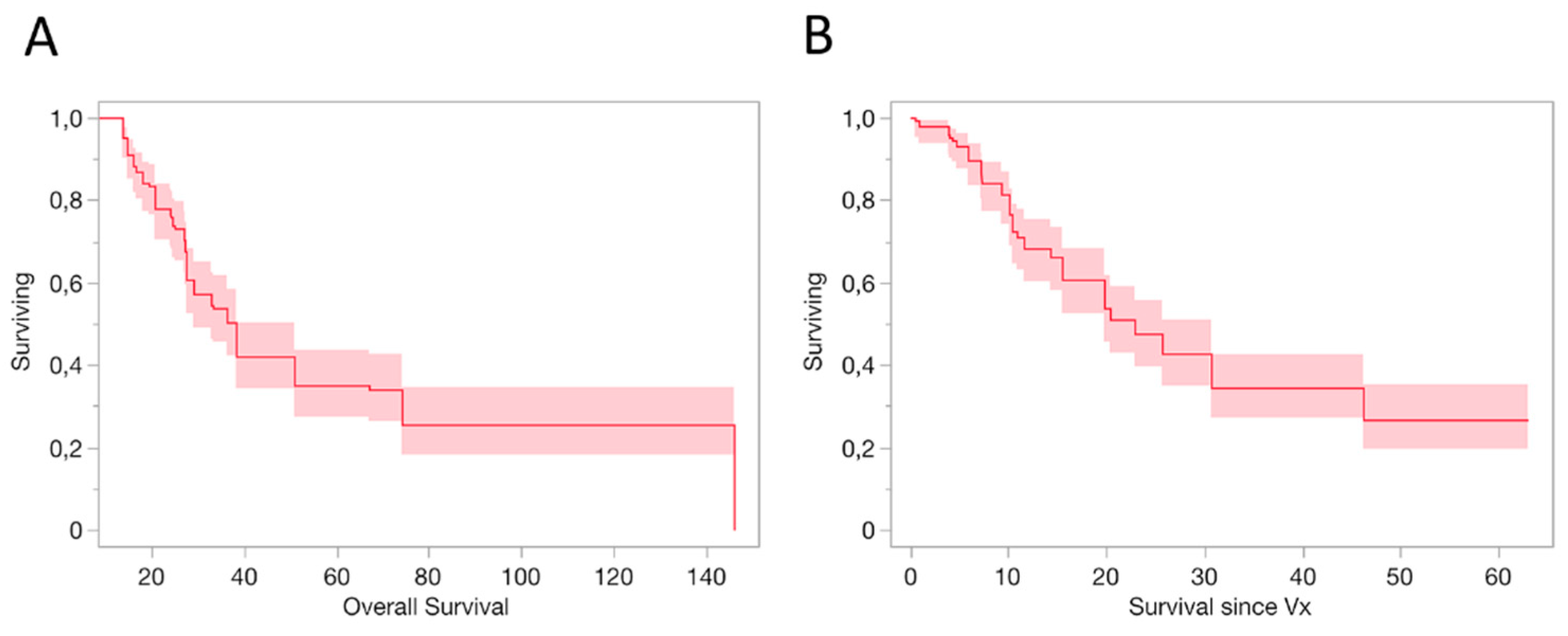

3.1. Survival Outcomes

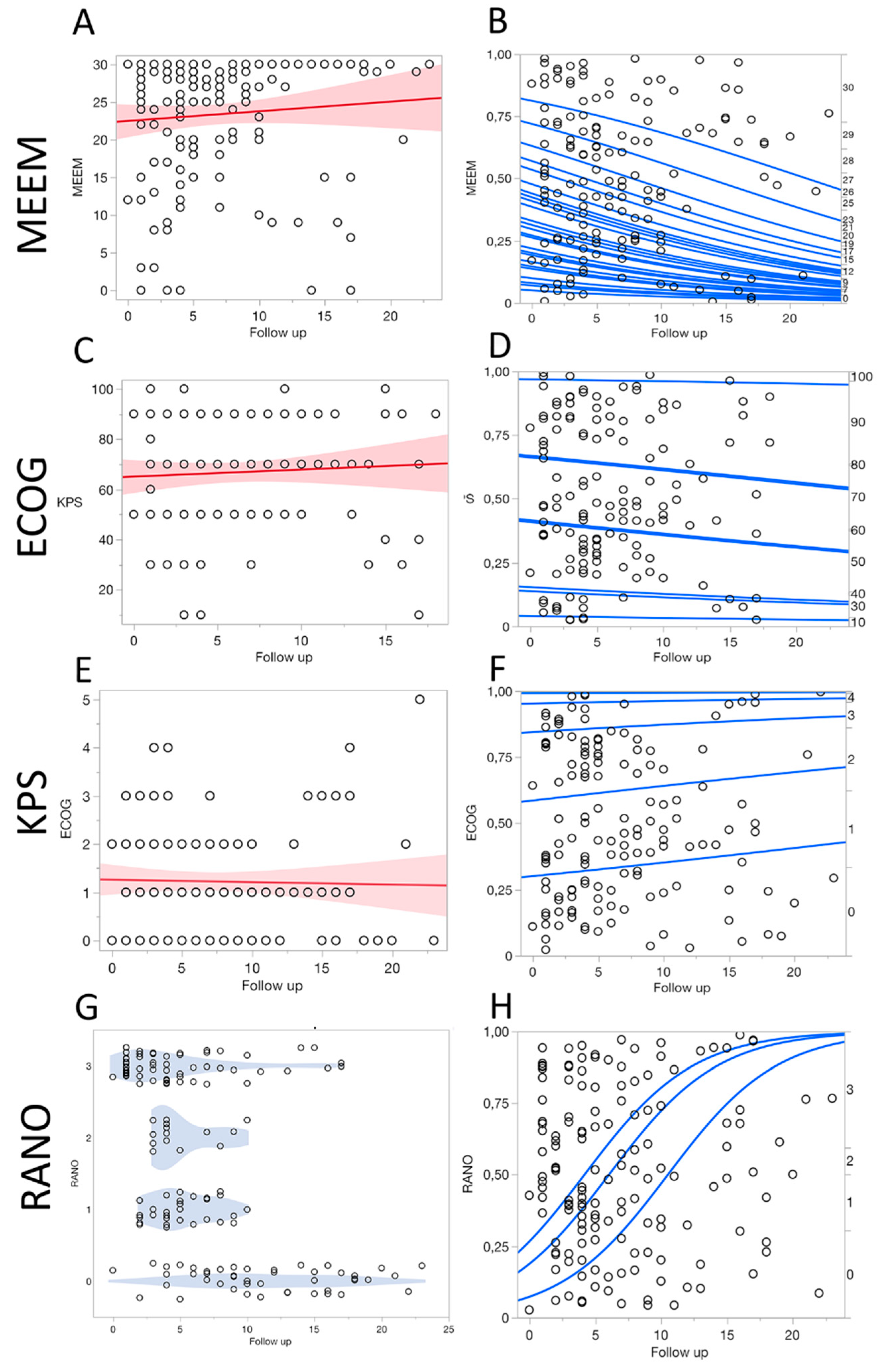

3.2. Survival Outcomes

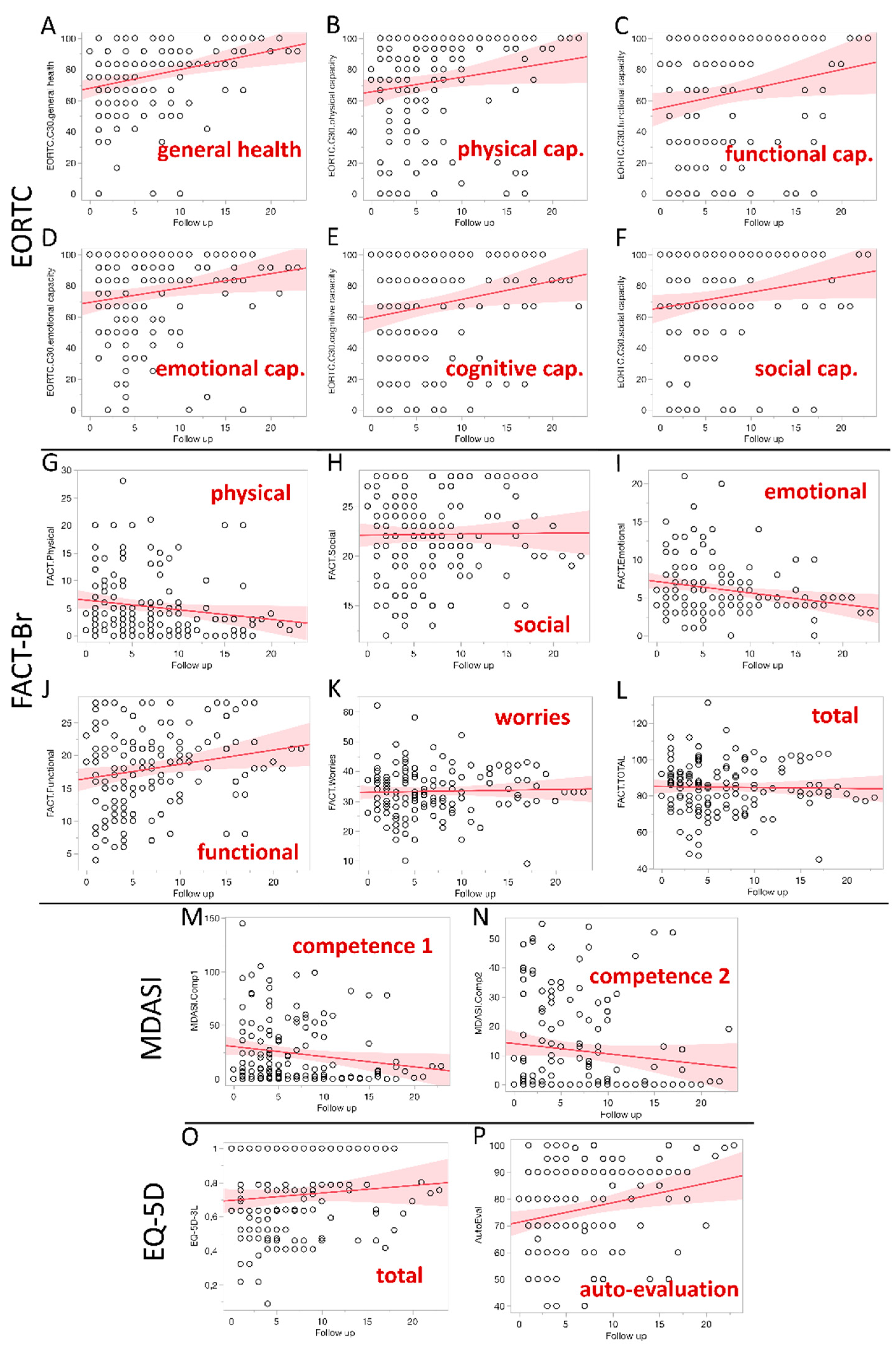

3.3. Survival Outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CNS | Central Nervous System |

| DC | Dendritic Cell |

| ECOG | Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group |

| EORTC | European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) |

| FACT | Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy |

| GBM | Glioblastoma |

| HRQoL | Health-Related QoL |

| KPS | Karnofsky Performance Status |

| MDASI-BT | MD Anderson Symptom Inventory Brain Tumor |

| MEEM | Mini-Mental State Examination |

| PBMC | Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells |

| QLQ-C30 | Quality of Life Questionnaire |

| QoL | Quality of life |

References

- Cella D.F.; Tuslky D.S. Quality of life in cancer. Definition, purpose and method of measurement. Cancer Invest 1993, 11:327-336.

- Osoba D. Measuring the effect of cancer on health-related quality of life. Pharmacoeconomics 1995, 7(4):308-19. [CrossRef]

- Till J.E., McNeil B.J., Bush R.S. Measurements of multiple components of quality of life. Cancer Treat Sympt 1984, 1:177.

- Gotay C.C., Korn E.L., McCabe M.S., Moore T.D., Cheson B.D. Quality-of-life assessment in cancer treatment protocols: research issues in protocol development. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1992, 15;84(8):575-9. [CrossRef]

- Heimans J.J., Taphoorn M.J. Impact of brain tumour treatment on quality of life. J Neurol. 2002, 249(8):955-60.

- Osoba D., Brada M., Prados M.D., Yung W.K. Effect of disease burden on health-related quality of life in patients with malignant gliomas. Neuro Oncol 2000, 2(4):221-8.

- Klein M., Taphoorn M.J., Heimans J.J., van der Ploeg H.M., Vandertop W.P., Smit E.F., Leenstra S., Tulleken C.A., Boogerd W., Belderbos J.S., Cleijne W., Aaronson N.K. Neurobehavioral status and health-related quality of life in newly diagnosed high-grade glioma patients. J Clin Oncol. 2001, 15;19(20):4037-47. [CrossRef]

- Imperato J.P., Paleologos N.A., Vick N.A. Effects of treatment on long-term survivors with malignant astrocytomas. Ann Neurol. 1990, 28(6):818-22. [CrossRef]

- Gregor A., Cull A., Traynor E., Stewart M., Lander F., Love S. Neuropsychometric evaluation of long-term survivors of adult brain tumours: relationship with tumour and treatment parameters. Radiother Oncol. 1996, 41(1):55-9. [CrossRef]

- Henriksson R., Asklund T., Poulsen H.S. Impact of therapy on quality of life, neurocognitive function and their correlates in glioblastoma multiforme: a review. J Neurooncol. 2011, 104(3):639-46. [CrossRef]

- Samman R.R., Timraz J.H., Mosalem Al-Nakhli A., Haidar S., Muhammad Q., Irfan Thalib H., Hafez Mousa A., Samy Kharoub M. The Impact of Brain Tumors on Emotional and Behavioral Functioning. Cureus. 2024, 8;16(12):e75315.

- Fujii D.E., Wylie A.M., Nathan J.H. Neurocognition and long-term prediction of quality of life in outpatients with severe and persistent mental illness. Schizophr Res. 2004, 1;69(1):67-73.

- Giovagnoli A.R., Silvani A., Colombo E., Boiardi A. Facets and determinants of quality of life in patients with recurrent high grade glioma. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005, 76(4):562-8. [CrossRef]

- Li J., Bentzen S.M., Li J., Renschler M., Mehta M.P. Relationship between neurocognitive function and quality of life after whole-brain radiotherapy in patients with brain metastasis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008, 1;71(1):64-70. [CrossRef]

- Cheng J.X., Zhang X., Liu B.L. Health-related quality of life in patients with high-grade glioma. Neuro Oncol. 2009, 11:41–50. [CrossRef]

- Peres N., Lepski G.A., Fogolin C.S., Evangelista G.C.M., Flatow E.A., de Oliveira J.V., Pinho M.P., Bergami-Santos P.C., Barbuto J.A.M. Profiling of Tumor-Infiltrating Immune Cells and Their Impact on Survival in Glioblastoma Patients Undergoing Immunotherapy with Dendritic Cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2024, 12;25(10):5275. [CrossRef]

- Lepski G., Bergami-Santos P.C., Pinho M.P., Chauca-Torres N.E., Evangelista G.C.M., Teixeira S.F., Flatow E., de Oliveira J.V., Fogolin C., Peres N., Arévalo A., Alves V.A.F., Barbuto J.A.M. Adjuvant Vaccination with Allogenic Dendritic Cells Significantly Prolongs Overall Survival in High-Grade Gliomas: Results of a Phase II Trial. Cancers 2023, 15;15(4):1239. [CrossRef]

- Pinho M.P., Lepski G.A., Rehder R., Chauca-Torres N.E., Evangelista G.C.M., Teixeira S.F., Flatow E.A., de Oliveira J.V., Fogolin C.S., Peres N., Arévalo A., Alves V., Barbuto J.A.M., Bergami-Santos P.C. Near-Complete Remission of Glioblastoma in a Patient Treated with an Allogenic Dendritic Cell-Based Vaccine: The Role of Tumor-Specific CD4+T-Cell Cytokine Secretion Pattern in Predicting Response and Recurrence. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 12;23(10):5396. [CrossRef]

- Reardon D.A., Freeman G., Wu C.,.et al. Immunotherapy advances for glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol 2014, 16:1441-58.

- Steinman R.M. Decisions about dendritic cells: past, present, and future. Annu Rev Immunol 2012, 30:1-22. [CrossRef]

- Patente T.A., Pinho M.P., Oliveira A.A., Evangelista G.C.M., Bergami-Santos P.C., Barbuto J.A.M. Human Dendritic Cells: Their Heterogeneity and Clinical Application Potential in Cancer Immunotherapy. Front Immunol 2018;9:3176. [CrossRef]

- Palucka K, Banchereau J. Cancer immunotherapy via dendritic cells. Nat Rev Cancer 2012, 12:265-77.

- Ostrom Q.T., Bauchet L., Davis F.G., Deltour I., Fisher J.L., Langer C.E., Pekmezci M., Schwartzbaum J.A., Turner M.C., Walsh K.M., Wrensch M.R., Barnholtz-Sloan J.S. The epidemiology of glioma in adults: a "state of the science" review. Neuro Oncol. 2014, 16(7):896-913. [CrossRef]

- Bleeker F.E., Molenaar R.J., Leenstra S. Recent advances in the molecular understanding of glioblastoma. J Neurooncol 2012, 108:11-27. [CrossRef]

- Weathers S.P., Gilbert M.R. Current challenges in designing GBM trials for immunotherapy. J Neurooncol 2015;123:331-7. [CrossRef]

- Stupp R., Mason W.P., van den Bent M.J., et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med 2005, 352:987-96. [CrossRef]

- Louis D.N., Perry A., Wesseling P., et al. The 2021 WHO Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: a summary. Neuro Oncol 2021, 23:1231-51. [CrossRef]

- Mooney J., Bernstock J.D., Ilyas A., et al. Current Approaches and Challenges in the Molecular Therapeutic Targeting of Glioblastoma. World Neurosurg 2019, 129:90-100. [CrossRef]

- Garside R., Pitt M., Anderson R., Rogers G., Dyer M., Mealing S., Somerville M., Price A., Stein K. The effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of carmustine implants and temozolomide for the treatment of newly diagnosed high-grade glioma: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2007, 11(45):iii-iv, ix-221. [CrossRef]

- Klein M., Heimans J.J., Aaronson N.K., van der Ploeg H.M., Grit J., Muller M., Postma T.J., Mooij J.J., Boerman R.H., Beute G.N., Ossenkoppele G.J., van Imhoff G.W., Dekker A.W., Jolles J., Slotman B.J., Struikmans H., Taphoorn M.J. Effect of radiotherapy and other treatment-related factors on mid-term to long-term cognitive sequelae in low-grade gliomas: a comparative study. Lancet. 2002, 2;360(9343):1361-8.

- Hempen C., Weiss E., Hess C.F. Dexamethasone treatment in patients with brain metastases and primary brain tumors: do the benefits outweigh the side-effects? Support Care Cancer. 2002, 10(4):322-8.

- Sturdza A., Millar B.A., Bana N., Laperriere N., Pond G., Wong R.K., Bezjak A. The use and toxicity of steroids in the management of patients with brain metastases. Support Care Cancer. 2008, 16(9):1041-8.

- Taphoorn M.J. Neurocognitive sequelae in the treatment of low-grade gliomas. Semin Oncol. 2003, 30(6 Suppl 19):45-8. [CrossRef]

- Klein M., Taphoorn M.J., Heimans J.J., van der Ploeg H.M., Vandertop W.P., Smit E.F., Leenstra S., Tulleken C.A., Boogerd W., Belderbos J.S., Cleijne W., Aaronson N.K. Neurobehavioral status and health-related quality of life in newly diagnosed high-grade glioma patients. J Clin Oncol. 2001, 15;19(20):4037-47. [CrossRef]

- Taphoorn M.J., Stupp R., Coens C., Osoba D., Kortmann R., van den Bent M.J., Mason W., Mirimanoff R.O., Baumert B.G., Eisenhauer E., Forsyth P., Bottomley A. Health-related quality of life in patients with glioblastoma: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2005, 6(12):937-44. [CrossRef]

- Brada M., Hoang-Xuan K., Rampling R., Dietrich P.Y., Dirix L.Y., Macdonald D., Heimans J.J., Zonnenberg B.A., Bravo-Marques J.M., Henriksson R., Stupp R., Yue N., Bruner J., Dugan M., Rao S., Zaknoen S. Multicenter phase II trial of temozolomide in patients with glioblastoma multiforme at first relapse. Ann Oncol. 2001, 12(2):259-66. [CrossRef]

- Osoba D., Brada M., Yung W.K., Prados M.. Health-related quality of life in patients treated with temozolomide versus procarbazine for recurrent glioblastoma multiforme. J Clin Oncol. 2000, 18(7):1481-91. [CrossRef]

- Cloughesy T., Vredenburgh J.J., Day B. et al. Updated safety and survival of patients with relapsed glioblastoma treated with bevacizumab in the BRAIN study. J Clin Oncol 2010, 28(suppl; abstr 2008). [CrossRef]

- Zuniga R.M., Torcuator R., Jain R., Anderson J., Doyle T., Ellika S., Schultz L., Mikkelsen T. Efficacy, safety and patterns of response and recurrence in patients with recurrent high-grade gliomas treated with bevacizumab plus irinotecan. J Neurooncol. 2009, 91(3):329-36. [CrossRef]

- Barbuto, J.A.; Ensina, L.F.; Neves, A.R.; Bergami-Santos, P.; Leite, K.R.; Marques, R.; Costa, F.; Martins, S.C.; Camara-Lopes, L.H.; Buzaid, A.C. Dendritic cell-tumor cell hybrid vaccination for metastatic cancer. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2004, 53, 1111–1118. [CrossRef]

- Taphoorn M.J., Klein M. Cognitive deficits in adult patients with brain tumours. Lancet Neurol. 2004, 3(3):159-68. [CrossRef]

- Ownsworth T., Hawkes A., Steginga S., Walker D., Shum D. A biopsychosocial perspective on adjustment and quality of life following brain tumor: a systematic evaluation of the literature. Disabil Rehabil. 2009, 31(13):1038-55. [CrossRef]

- Gehring K., Sitskoorn M.M., Aaronson N.K., Taphoorn M.J. Interventions for cognitive deficits in adults with brain tumours. Lancet Neurol. 2008, 7(6):548-60. [CrossRef]

- Liu R., Page M., Solheim K., Fox S., Chang S.M. Quality of life in adults with brain tumors: current knowledge and future directions. Neuro Oncol. 2009, 11(3):330-9.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).