1. Introduction

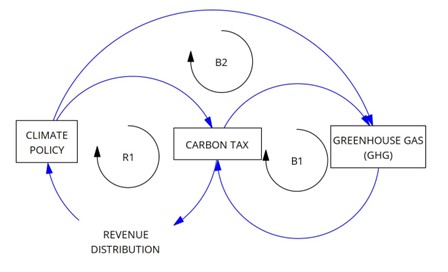

The proposed framework operates as a complex and interactive system defined by three critical causal loops that work in concert to regulate emissions while ensuring political durability. The central mechanism is the B1: The Climate Action Control Loop, a fundamental balancing loop designed to be the primary driver of change; here, high levels of GHG emissions create the necessary pressure and justification for a strong POLICY, which in turn defines and implements a TAX on polluters. This tax directly incentivizes industries to reduce their emissions, thus working to continuously close the gap between the current emissions level and the desired climate target. To ensure this core loop is sustainable and avoids political failure, it is powered by R1: The Policy Support Flywheel, a reinforcing loop that creates a virtuous cycle. In this flywheel, the TAX generates significant public revenue, which is strategically distributed back to households and industries through dividends and green funds, building widespread public and political support that strengthens the POLICY’s legitimacy and makes it easier to maintain or increase the tax rate over time. However, the framework must simultaneously navigate the inherent challenge presented by B2: The Revenue Erosion Loop, a counteracting balancing force where the policy’s very success in reducing GHG emissions inherently shrinks the tax base, causing a decline in TAX REVENUE. This potential drop in funding threatens to weaken the popular support programs that R1 relies upon, which could, in turn, erode the political capital needed to sustain the POLICY, creating a long-term drag that must be managed for the system to succeed.

Figure 1.

The Dynamics of a Self-Sustaining Carbon Tax Framework.

Figure 1.

The Dynamics of a Self-Sustaining Carbon Tax Framework.

1.1. Global and National Context

On the international stage, Malaysia has solidified its commitment to addressing climate change through its updated Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) submitted to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). In line with its commitments under the Paris Agreement, Malaysia aims to unconditionally reduce its greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions intensity across the economy by 45% by 2030, compared to its 2005 emissions intensity (Government of Malaysia, 2021). This commitment is further reinforced by the nation’s long-term aspiration to achieve net-zero GHG emissions as early as 2050, a goal enshrined in the Twelfth Malaysia Plan (Ministry of Economy, 2021). These aspirations set Malaysia on a transitional path towards low-carbon development, demanding the formulation of transformative policies and effective implementation mechanisms.

1.2. Problem Statement

As Malaysia advances its ambitious climate agenda, the nation is presented with a series of strategic opportunities for economic enhancement and policy innovation. First, the evolving international trade landscape, including the European Union’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), provides a compelling catalyst for Malaysia to future-proof its export sector. This mechanism is an invitation to innovate and align our high-value products with global low-carbon benchmarks, thereby enhancing their long-term market access and resilience. Second, the National Energy Transition Roadmap (NETR) outlines a significant opportunity to mobilize substantial green investment, unlocking innovative revenue streams to finance our forward-looking energy evolution. This creates a clear pathway for developing a vibrant, high-value green economy. Third, by engaging in constructive dialogue with our industry partners, particularly our vital small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), we are gathering valuable feedback to co-create carefully calibrated transition pathways. This collaborative approach ensures that the introduction of any new carbon pricing instrument is equitable and supports the continued competitiveness of all economic sectors. Finally, the government is undertaking a period of deliberate and consultative policy formulation to craft a robust legislative architecture for climate action. This measured approach ensures that the resulting framework will provide the clarity and long-term predictability needed to foster private sector confidence and anchor significant, high-quality investments. This dynamic interplay of international trends and domestic priorities presents a clear mandate for a holistic and forward-looking policy framework that will position Malaysia as a leader in the regional green transition.

1.3. Objectives and Contribution of the Paper

In response to these challenges, this paper aims to present a detailed, practical, and implementable carbon tax framework for Malaysia. Its primary objective is to design a mechanism that not only effectively reduces GHG emissions but also safeguards economic competitiveness, ensures social equity, and provides a sustainable revenue stream for the nation’s green transition agenda. The core contribution of this paper lies in its pragmatic approach: integrating mature, existing administrative mechanisms under the Inland Revenue Board (LHDN) and the Royal Malaysian Customs Department (JKDM) with international best practices. This approach aligns with expert recommendations to employ existing institutional capacities to ensure an efficient and cost-effective rollout (Basto & Miller, 2017). Furthermore, this paper adapts elements from globally successful Monitoring, Reporting, and Verification (MRV) systems to serve as the foundation for ensuring the transparency and credibility of emissions data.

1.4. Structure of the Paper

This paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 presents a contextual analysis of Malaysia’s emissions profile and a literature review of carbon pricing design principles.

Section 3 details the methodology for the proposed carbon tax framework, covering its tax structure, MRV system, revenue recycling mechanisms, and industry support measures.

Section 4 analyzes the fiscal and economic implications of the proposal, including an applied case study and a risk analysis.

Section 5 outlines the implementation framework in terms of governance and legislation. Finally,

Section 6 concludes by summarizing the paper’s key contributions and suggests directions for future research.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Malaysia’s Emissions and Economic Profile

An effective carbon pricing policy must be tailored to the nation’s specific economic structure and emissions sources. In Malaysia, GHG emissions are heavily concentrated in a few key sectors. The energy sector, primarily from electricity generation using fossil fuels, and the industrial sector, including manufacturing and construction, are the largest contributors to the national emissions profile. This is illustrated in the emissions data published in the Department of Environment’s annual reports (Jabatan Alam Sekitar, 2023). A trend analysis of Malaysia’s emissions over the past two decades shows a consistent upward trajectory closely correlated with economic growth, underscoring the carbon intensity of the nation’s development model (International Energy Agency, 2022). The significant contribution of stationary sources in the power and industrial sectors provides a clear and compelling justification for the proposed framework’s initial focus (Phase 1) on these entities, as they represent the most substantial and administratively accessible sources for emissions reduction.

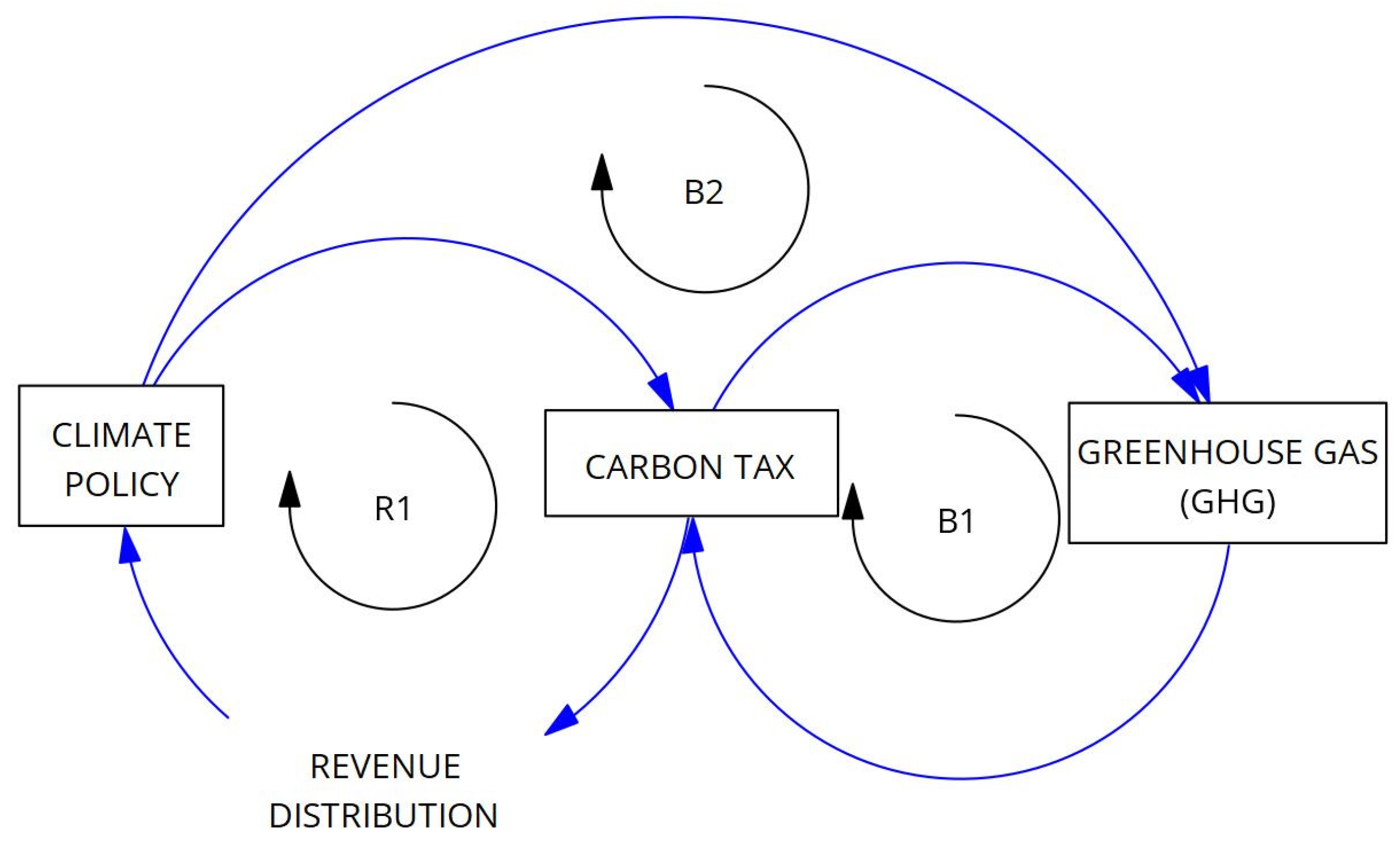

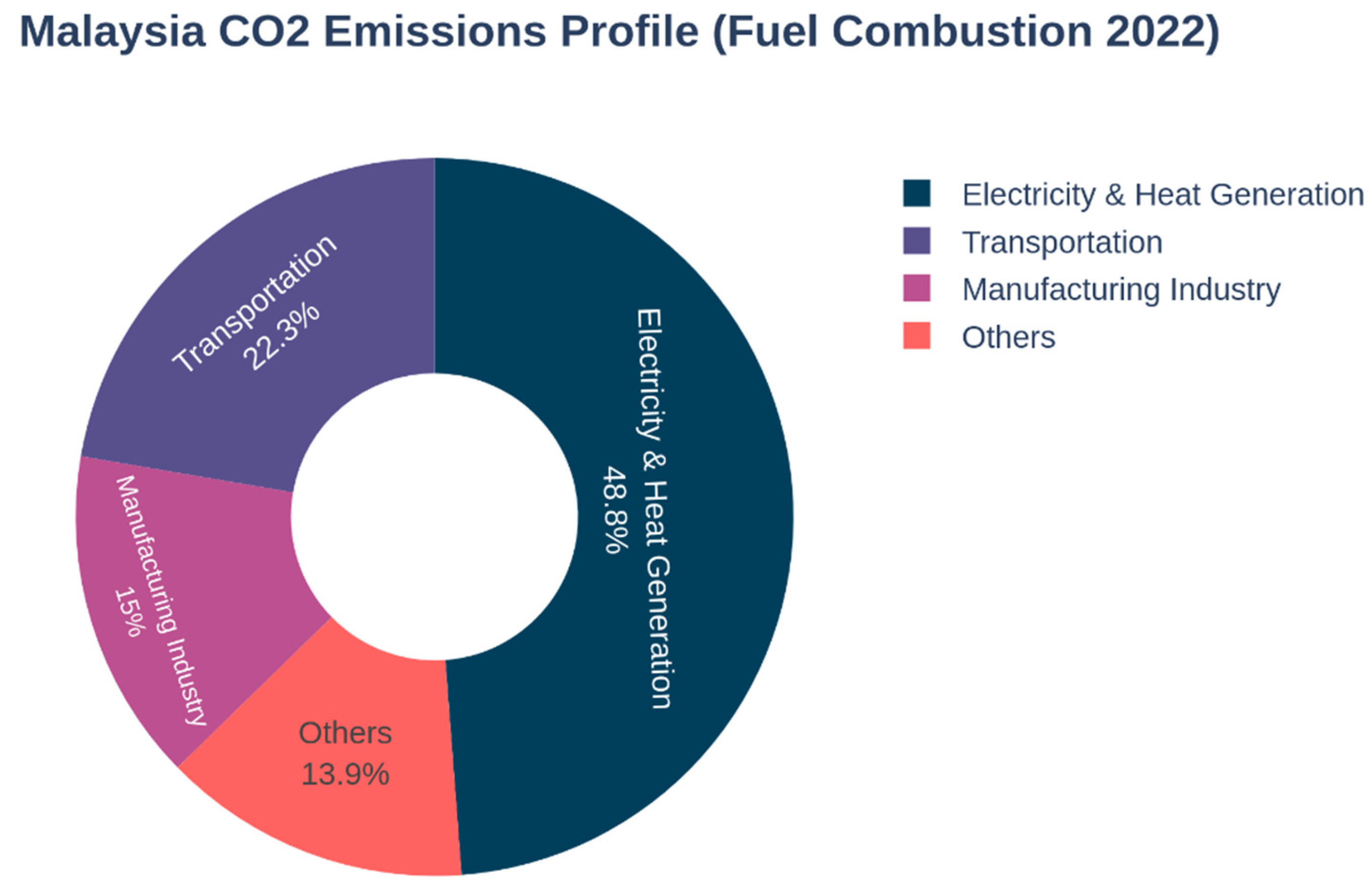

An analysis of Malaysia’s carbon dioxide emissions from 2000 to 2023 reveals a consistent and significant upward trend, with total annual emissions from fuel combustion more than doubling from 137.5 million tonnes to 283 million tonnes over the 23-year period. This sustained growth indicates a strong correlation between the nation’s economic development and its carbon output. A detailed sectoral breakdown for the year 2022 identifies the primary sources of these emissions, with Electricity and Heat Generation being the most significant contributor, accounting for nearly half (48.8%) of the total. The transportation sector follows as the second-largest emitter at 22.3%, with the manufacturing industry contributing a further 15%. Although a minor and temporary decline in emissions was observed in 2020, dropping to 270 million tonnes, the long-term trajectory quickly resumed its upward path. These findings collectively underscore that Malaysia’s rising CO2 emissions profile is predominantly driven by its energy and transportation sectors, pinpointing these areas as critical for the implementation of future climate change mitigation strategies.

Figure 2.

Malaysia’s CO2 Emissions Profile by Sector in year 2022.

Figure 2.

Malaysia’s CO2 Emissions Profile by Sector in year 2022.

Figure 3.

Annual CO2 Emissions Trend, 2000-2023.

Figure 3.

Annual CO2 Emissions Trend, 2000-2023.

2.2. International Comparison

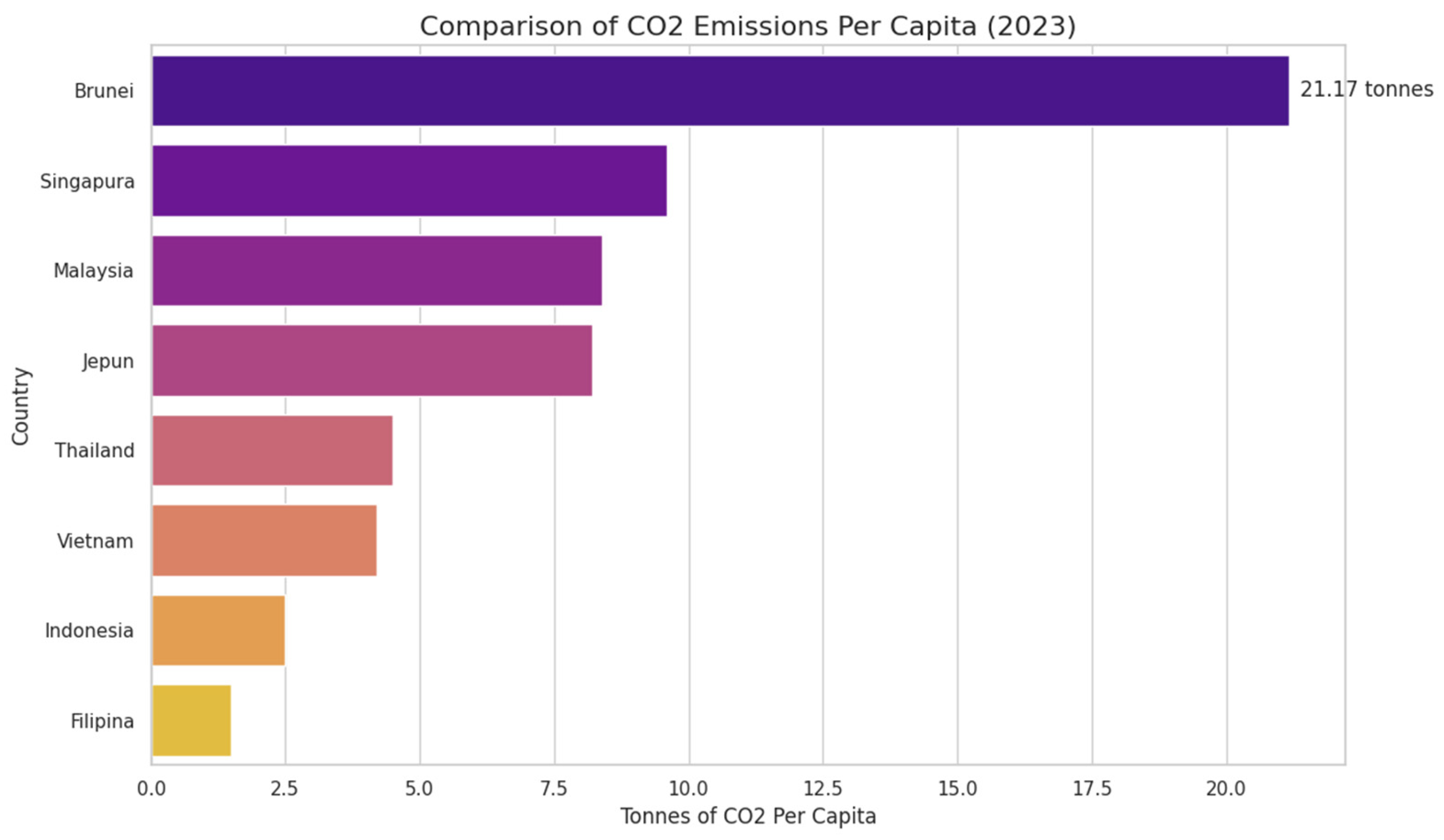

On a per capita basis, Malaysia’s CO2 emissions are among the highest in the ASEAN region and are comparable to those of some developed economies. This highlights both the nation’s development progress and the carbon-intensive nature of that progress (World Bank, 2024). As countries globally adopt climate policies, it is crucial for Malaysia to learn from established international precedents. The framework proposed in this paper draws significant inspiration from Singapore’s carbon pricing mechanism, particularly its robust Monitoring, Reporting, and Verification (MRV) system. Singapore’s approach, legislated under its Carbon Pricing Act, provides a clear, transparent, and credible process for measuring emissions from large industrial facilities (Ministry of Sustainability and the Environment, Singapore, 2023). Its success serves as a best-practice benchmark for the digital MRV system (MyCARR) proposed for Malaysia, demonstrating how a clear legislative and technical foundation can foster trust and ensure compliance.

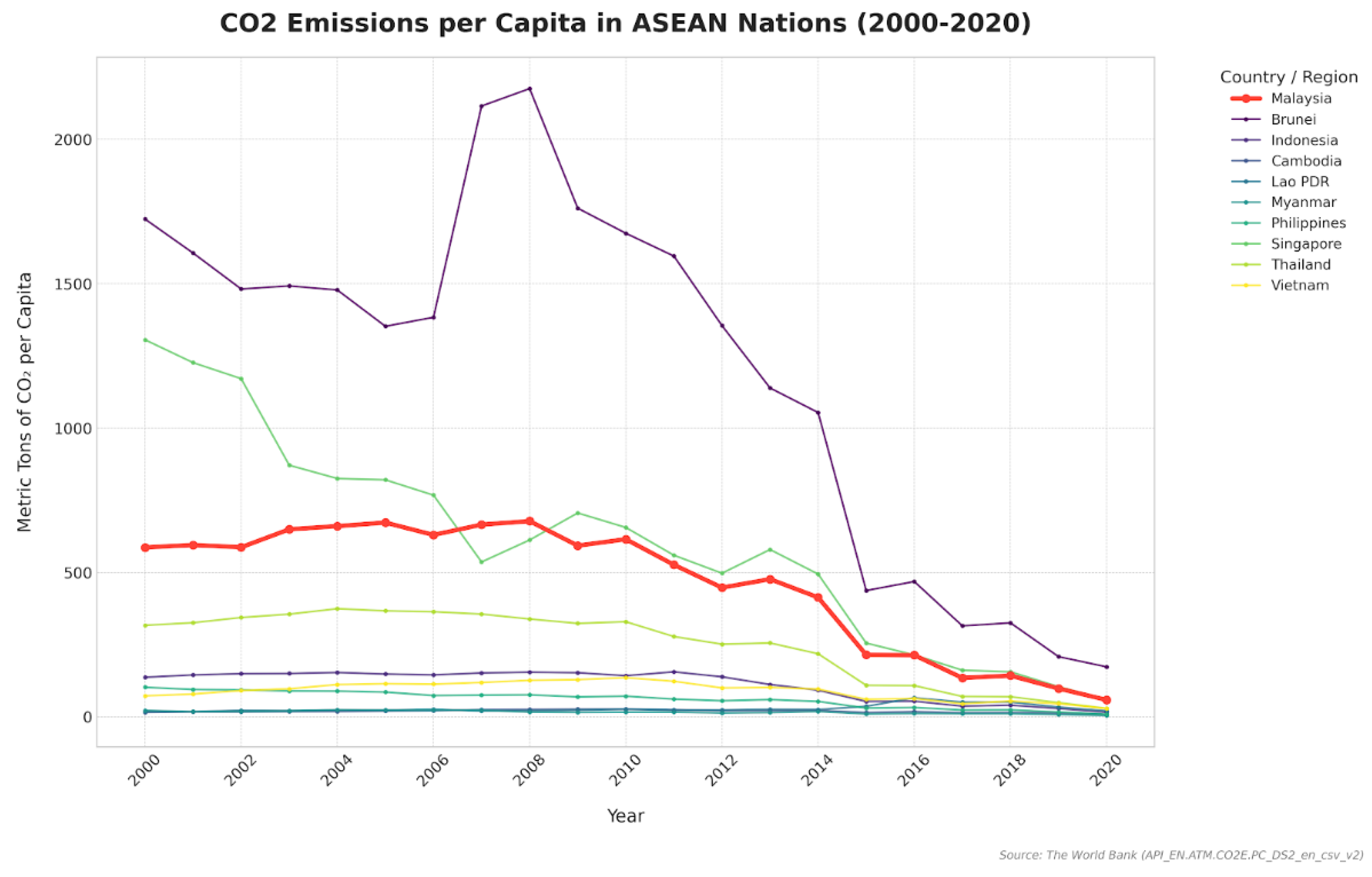

An analysis of per capita carbon dioxide emissions across the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) from 2000 to 2020 reveals a region of significant internal divergence rather than a single, unified trend. The block can be broadly categorized into distinct tiers of emitters, with the overall regional dynamic being heavily influenced by the downward trajectory of its highest per capita emitters. Notably, Brunei, historically the region’s highest emitter, experienced a dramatic peak of over 2,000 metric tons per capita around 2007, followed by a steep and consistent decline to levels comparable with other member states by 2020. Similarly, upper-middle emitters like Malaysia and Singapore demonstrated a stabilization and subsequent gradual decline in per capita emissions, particularly in the latter half of the period. In stark contrast, most ASEAN nations, including populous countries like Indonesia, Vietnam, and the Philippines, maintained consistently low and relatively stable per capita emissions throughout the two decades. Therefore, the overall regional trend points towards a reduction in per capita emissions, driven primarily by corrections in the highest-emitting countries, while the larger, developing economies have not yet shown significant increases in their per capita carbon footprint.

Figure 4.

Trends in Carbon Dioxide Emissions per Capita for Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Member States, 2000-2020.

Figure 4.

Trends in Carbon Dioxide Emissions per Capita for Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Member States, 2000-2020.

Figure 5.

Per Capita CO2 Emissions Comparison: Malaysia vs. Regional & Developed Nations.

Figure 5.

Per Capita CO2 Emissions Comparison: Malaysia vs. Regional & Developed Nations.

2.3. Carbon Pricing Design Principles

The theoretical underpinning of carbon pricing is the “polluter pays” principle, which internalizes the external costs of climate change. Globally, this is achieved through two primary instruments: a carbon tax or an Emissions Trading System (ETS). A carbon tax provides price certainty, making it straightforward for businesses to factor the cost of carbon into their investment decisions. ETS provides quantity certainty by setting a cap on total emissions, but can result in price volatility (Goulder, 2013). This paper proposes a carbon tax for its administrative simplicity and price predictability, which are crucial for an initial rollout. Furthermore, a critical principle for successful carbon pricing design is the strategic use of the revenue generated. Research consistently shows that public and political acceptance of a carbon tax is significantly higher when the revenue is transparently “recycled” back into the economy. This can be done to enhance social equity, for instance by providing dividends to low-income households, or to support green growth by funding decarbonization technologies, thereby ensuring the policy is not only effective but also fair (Boyce, 2018; Klenert et al., 2018).

3. Methodology

This section details the proposed architecture of the Malaysian Carbon Tax. The framework is built on four core objectives and integrates a robust technical foundation with a pragmatic, phased-in tax structure and carefully designed support mechanisms. The proposed high-level administrative and governance framework is structured around four distinct but interconnected pillars: Policy & Oversight, Industry & Emitters, Tax Administration & Collection, and a Technical Framework for Monitoring, Reporting, and Verification (MRV). This system employs a dual-taxation strategy, imposing an upstream tax on fuel suppliers administered by a customs authority (such as JKDM) and a downstream tax on industrial process emissions from key sectors like steel and cement, to be collected by an inland revenue body (like LHDN). A central component of this architecture is a robust MRV process managed by a designated technical authority (e.g., NRES), which would operate a digital portal for emissions reporting, approve monitoring plans, and accredit independent auditors to ensure data accuracy and transparency. For strategic direction, a high-level Carbon Price Council, co-chaired by the Ministry of Finance and the technical authority, will be formed to set overall policy, dynamically review tax rates, and oversee revenue allocation. Adopting this structure ensures a clear separation of duties between policymaking, technical verification, and tax collection, thereby creating a robust and transparent system for the effective implementation of a national carbon pricing policy.

Figure 6.

The Proposed High-Level Administrative & Governance Framework for Carbon Tax.

Figure 6.

The Proposed High-Level Administrative & Governance Framework for Carbon Tax.

3.1. Core Objectives

This framework is strategically designed around four pillars of national enhancement to guide Malaysia’s next phase of economic development. It aims to catalyze innovation across industries by creating a market environment that rewards efficiency and encourages a forward-looking transition to a low carbon operating model, aligning perfectly with national climate aspirations. Furthermore, the framework is architected to bolster the global competitiveness of key economic sectors, proactively positioning Malaysian businesses to thrive in an evolving international marketplace. A core principle of this initiative is to foster an inclusive and equitable transition, where the proceeds are reinvested to empower communities and support households, ensuring that the benefits of progress are shared by all Malaysians. Finally, this will unlock a significant stream of green investment, mobilizing dedicated capital to fund the nation’s ambitious energy transition and build a more resilient, sustainable future for generations to come.

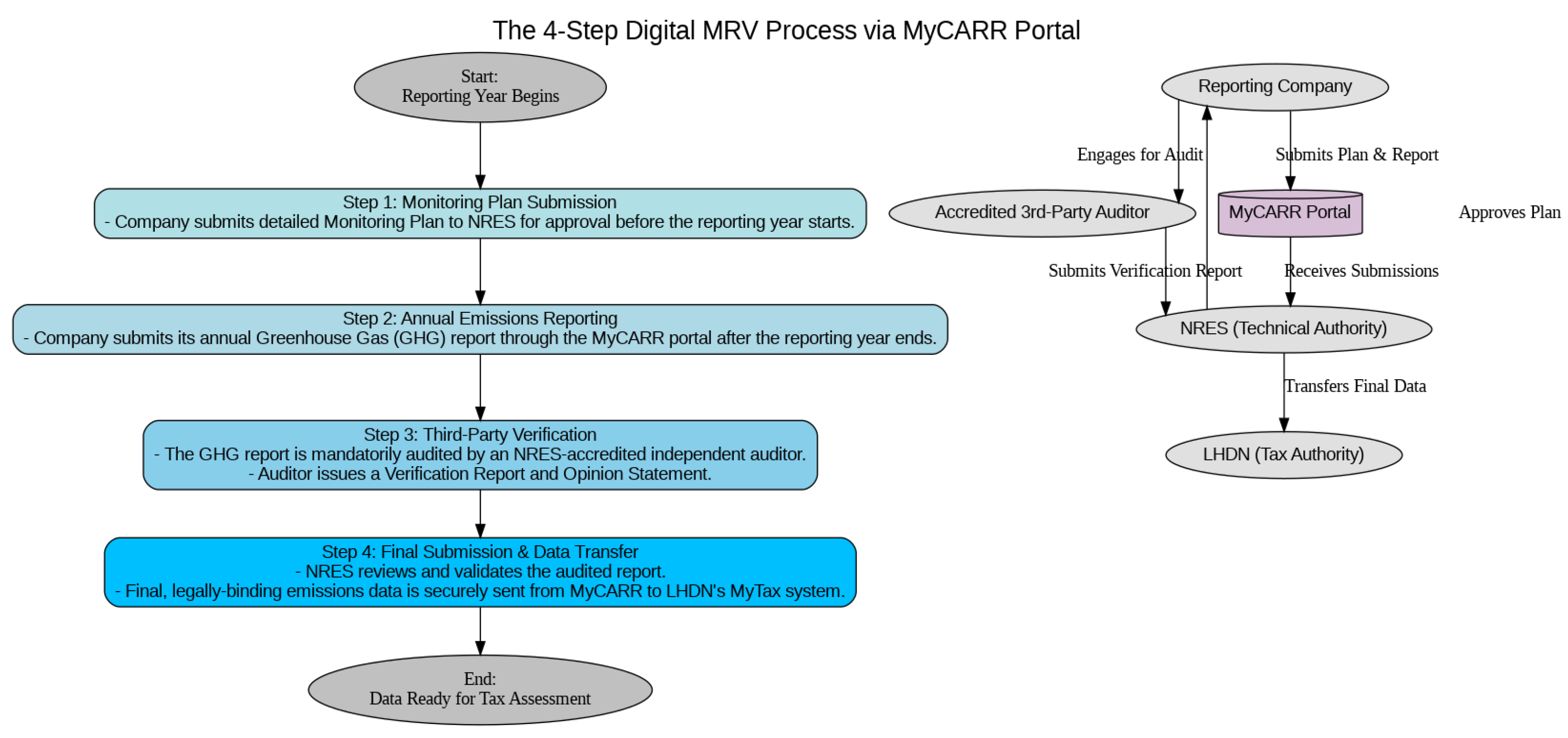

3.2. Technical Foundation: Digital MRV System (MyCARR)

The credibility of any carbon pricing policy rests on the accuracy and transparency of its emissions data. The technical foundation of the framework is the mandatory, digital-first Malaysian Carbon & Attribute Reporting & Registration (MyCARR) system, to be managed by the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Sustainability (NRES) as the central authority. Its legal authority would stem from a new, standalone Carbon Tax Act, or potentially a broader climate change bill like a Rang Undang-Undang Perubahan Iklim (RUUPIN). Under this Act, NRES, as the central technical regulator, would enact specific Carbon Tax (Monitoring, Reporting and Verification) Regulations.

Figure 7.

The Proposed 4-Step Digital MRV Process via MyCARR Portal.

Figure 7.

The Proposed 4-Step Digital MRV Process via MyCARR Portal.

These regulations would detail technical specifics, for instance, by mandating that facilities with annual emissions exceeding a set limit, such as 25,000 tonnes of CO2e, must report. Furthermore, the regulations would define the scope of covered greenhouse gases like CO2, CH4, and N2O, aligning with international guidelines from the IPCC. To ensure the credibility of this data, which is essential for the entire framework, the accreditation standards for third-party auditors would be based on stringent international best practices, such as ISO 14065 and ISO 14064-3. This approach ensures that all verified emissions reports provide a ‘reasonable level of assurance’, building on the framework’s principle of using independent auditors to guarantee data integrity.

The proposed framework is underpinned by a 4-step digital Monitoring, Reporting, and Verification (MRV) process, facilitated through the centralized MyCARR Portal to ensure data integrity for tax assessment. The process commences before the reporting year with Step 1, where companies must submit a detailed Monitoring Plan to the technical authority (NRES) for approval. Following the reporting year, in Step 2, companies submit their annual Greenhouse Gas (GHG) reports via the MyCARR portal. A critical integrity check occurs in Step 3, which mandates that the GHG report be verified by an NRES-accredited independent third-party auditor, who then issues a formal Verification Report and Opinion Statement. The process concludes with Step 4, where NRES reviews the validated audited report and executes a secure transfer of the final, legally binding emissions data to the tax authority’s (LHDN) system, making the data ready for assessment. This structured workflow establishes a clear and auditable trail, with distinct roles for the reporting entity, auditor, and government authorities, thereby creating a robust and transparent foundation for the carbon tax mechanism.

3.3. Phased and Hybrid Tax Structure

This document outlines a proposed carbon tax framework for Malaysia, designed to integrate a high-level economic rationale with a practical and phased implementation plan. The approach utilizes a hybrid tax model that utilizes existing Malaysian customs and tax systems to ensure precise, efficient, and effective administration of the levy. The core objective is to establish a policy that is both economically sound and administratively feasible.

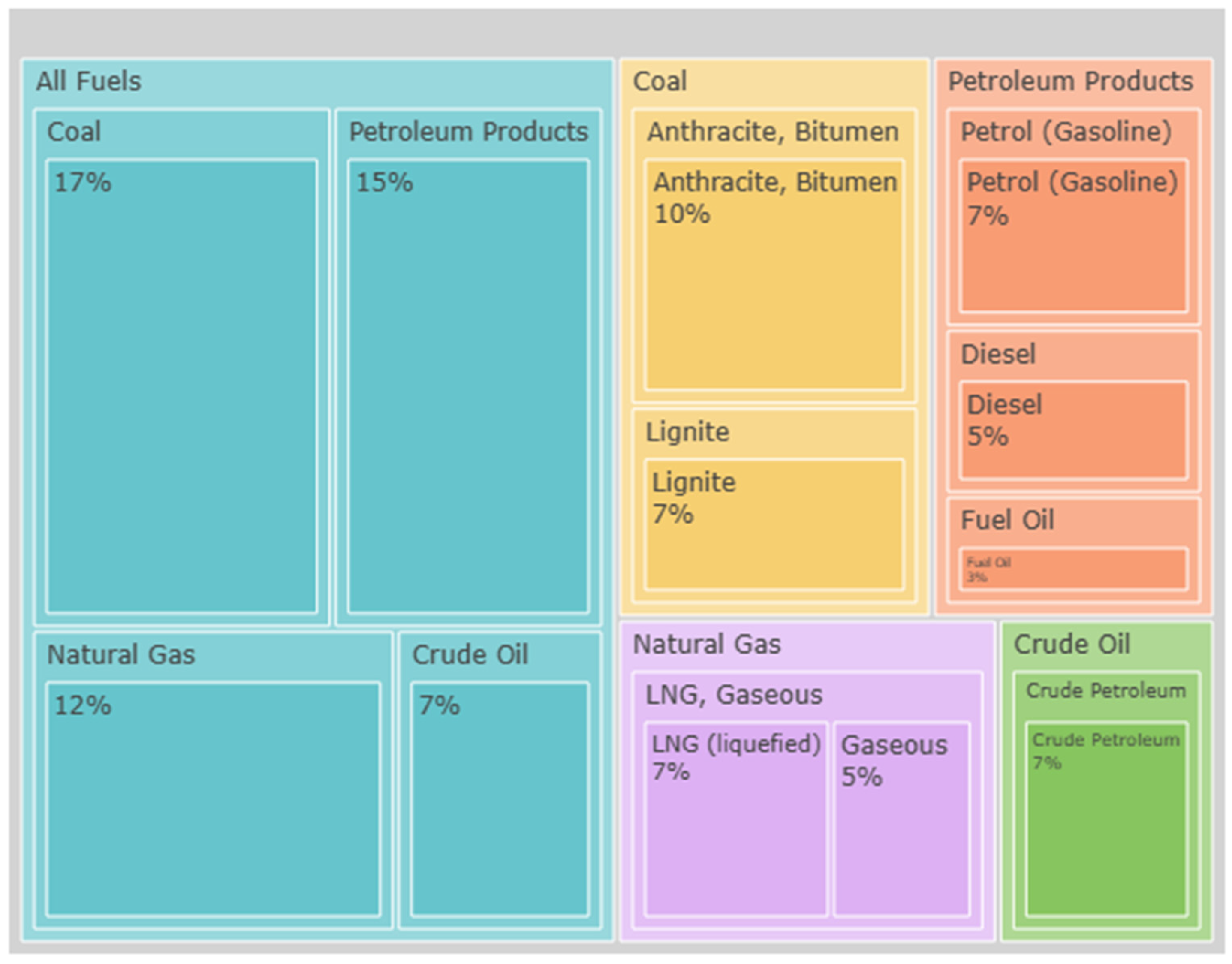

Figure 8.

The Proposed Fuel Categories Covered by Upstream Carbon Levy.

Figure 8.

The Proposed Fuel Categories Covered by Upstream Carbon Levy.

To minimize economic shock and allow for administrative capacity building, the framework proposes a phased implementation, with Phase 1 targeting the largest and most accessible emissions sources. This initial phase utilizes a hybrid tax model to achieve comprehensive coverage. An upstream tax on fuels will be applied as an excise duty on the carbon content of fossil fuels like coal, natural gas, and petroleum at their point of import or production, to be administered by the Royal Malaysian Customs Department (JKDM). Concurrently, a downstream tax will be applied directly to non-energy, industrial process emissions from large facilities, such as those from chemical reactions in cement or steel production. This component will be administered by the Inland Revenue Board (LHDN) and integrated into its corporate tax assessment cycle, a hybrid strategy recognized as a best practice for its broad coverage and administrative efficiency.

The downstream component of the carbon tax would be administered by the Inland Revenue Board (LHDN), with its core administration integrated into the existing Self-Assessment System (SAS). To facilitate this, a new, dedicated tax form, notionally titled Borang Cukai Karbon (Borang CK), could be introduced for mandatory e-filing through the MyTax portal. This form would be the primary instrument for operationalizing the double taxation prevention mechanism. The structure of Borang CK would be designed for clarity and automation. For instance, Part B of the form would calculate the gross tax liability, a section that could be auto-populated using verified emissions data transmitted securely from the NRES MyCARR portal. Subsequently, Part C would allow facilities to claim credit for the upstream tax already paid on fuels, thereby preventing double taxation. Companies would input their fuel combustion emissions data from their MRV report, and the system would calculate the corresponding credit value. Finally, Part D would automatically calculate the final tax payable by subtracting the upstream credit from the gross liability. To further streamline the process, companies could incorporate these tax payments into their existing monthly installment plans (Skim CP204) and make final payments through standard LHDN channels like ByrHASiL.

The proposed initial tax rate is set at RM40 per tonne of CO2-equivalent, which is approximately USD 8.50. To provide a predictable price trajectory for business and investment planning, the framework includes a scheduled escalation of RM15 every two years. This gradual and transparent increase is designed to help the market adapt while steadily advancing the nation’s climate objectives.

The upstream fuel levy is a central component of Phase 1, targeting primary fuels that collectively account for 51% of the intended tax base. For coal, which represents 17% of this base, the levy will be applied as a specific rate in Ringgit Malaysia per metric tonne at the point of import. This targets Anthracite and Bitumen under HS Code 27.01 and Lignite under HS Code 27.02. Petroleum products constitute 15% of the levy base, with the tax applied as a specific rate per liter at the refinery gate or point of import. This would cover key fuels such as petrol under HS Code 2710.12, and diesel and fuel oil under HS Code 2710.19. Furthermore, the proposal assigns 12% of the levy-base to Natural Gas and 7% to Crude Petroleum. For Natural Gas, a more accurate tax based on energy content, such as RM per GigaJoule or MMBtu, is suggested to cover both its liquefied (HS Code 2711.11) and gaseous (HS Code 2711.21) forms. For Crude Petroleum (HS Code 27.09), a specific rate per barrel or per metric tonne would be applied at the most upstream point of the supply chain. This ensures the levy’s impact is embedded in the cost and distributed across all resulting products.

The core principles guiding this proposal are a phased implementation to manage economic impact, a hybrid model combining upstream and downstream taxes for comprehensive coverage, and an integrated approach that links policy objectives to existing administrative frameworks. By using targeted and tailored mechanisms, such as specific HS codes and varied tax rate structures, the framework ensures both administrative feasibility and accuracy. Adopting this integrated framework would equip Malaysia with a sophisticated and comprehensive carbon pricing policy that is both economically sound and administratively practical.

3.4. Revenue Recycling and Social Equity

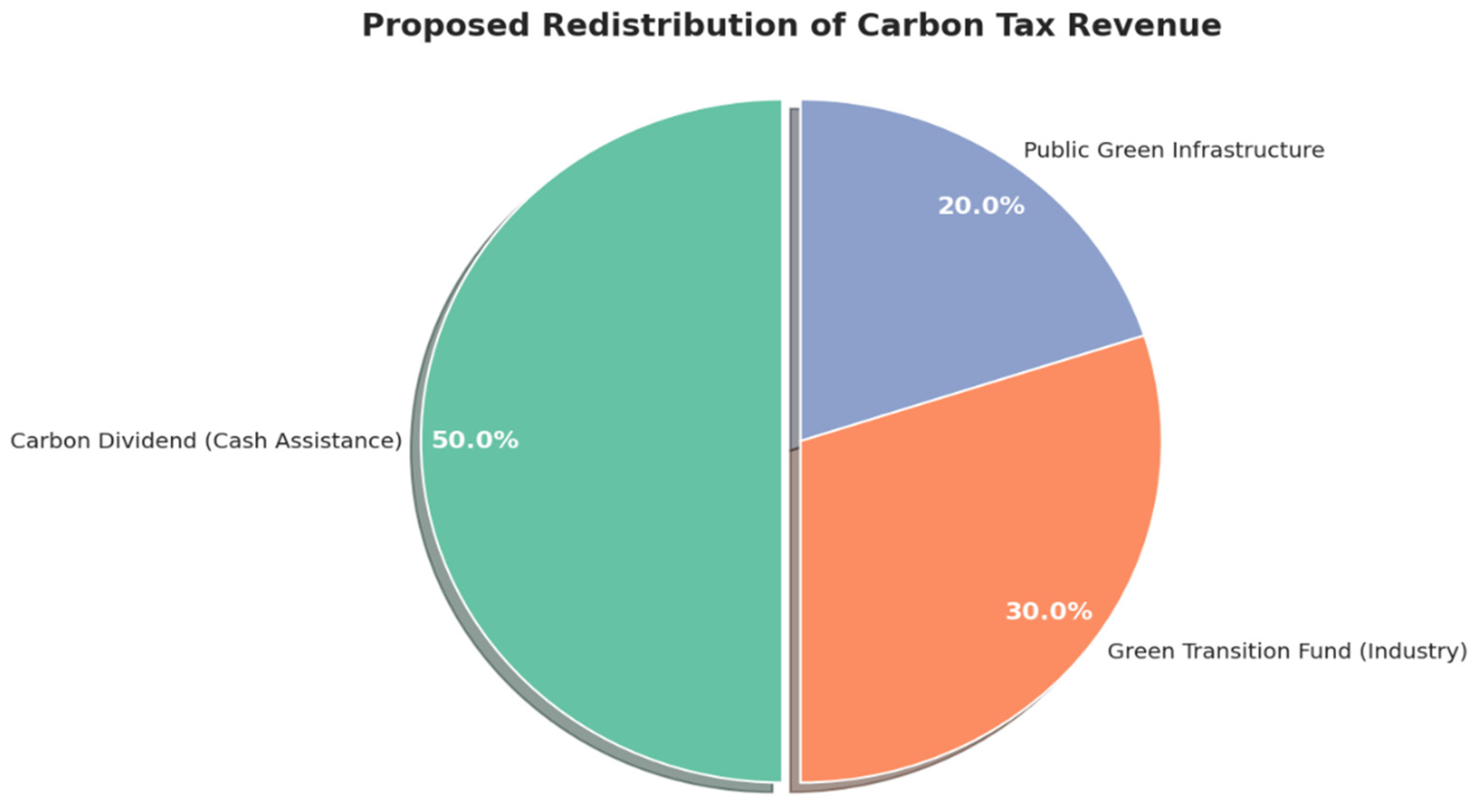

We propose that a cornerstone of the carbon tax framework should be the principle that 100% of the revenue generated is segregated into a dedicated fund and transparently recycled back into the economy. To achieve this, the structure should move beyond a theoretical choice between models by adopting a comprehensive hybrid approach that strategically combines the core tenets of both a “Carbon Dividend” and a “Green Growth” model. This integrated design would ensure the transition is not only economically sustainable but also socially equitable.

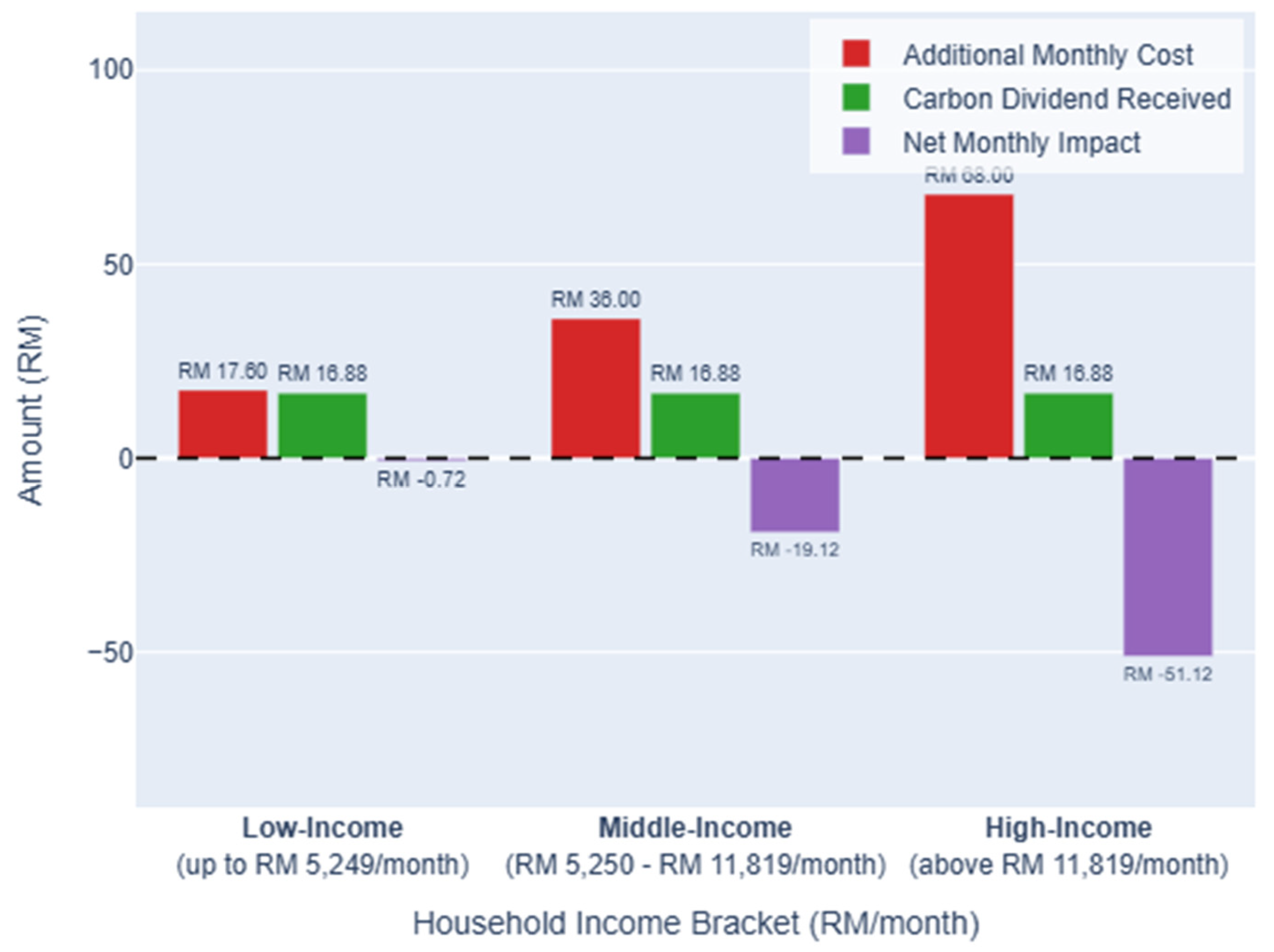

To directly address the potential regressive impacts of the tax, this revenue recycling strategy should be designed to prioritize household protection. It is recommended that a significant portion, precisely 50% of all revenue collected, be returned directly to the public as a Carbon Dividend in the form of cash assistance. This “Carbon Dividend” element would serve to neutralize the impact of higher costs for households. An analysis of this proposed redistribution indicates a clear progressive design. While the tax would impose additional monthly costs across all income levels, a flat-rate dividend, calculated here at RM 16.88, would disproportionately benefit lower-income households. This would mean low-income households are almost entirely compensated, facing a negligible net monthly cost of RM 0.72. Such a strategy has been shown to increase public acceptance and ensure social equity, effectively protecting the most vulnerable segments of the population (Klenert et al., 2018).

To complement direct household support, the remaining revenue ought to be channelled into a national “Green Growth” model via a Green Transition Fund. This fund should then be divided, with a proposed 30% of total revenue allocated to support industrial decarbonization projects and provide grants and soft loans for SMEs to adopt cleaner technologies. The final 20% should be invested in public green infrastructure, such as renewable energy projects and the expansion of electric vehicle charging networks. Adopting this dual investment strategy would mirror the function of established international mechanisms like the EU’s Just Transition Fund (European Commission, 2023), ensuring that while households are protected, society contributes to and benefits from a broader, state-funded transition. Under this model, middle- and high-income households would bear a greater net financial burden of RM 19.12 and RM 51.12 per month, respectively, ensuring all segments of society contribute equitably to the cost of carbon emissions.

Figure 9.

Proposed Allocation of Carbon Tax Revenue.

Figure 9.

Proposed Allocation of Carbon Tax Revenue.

Figure 10.

Simulated Net Monthly Impact on Households by Income Brackets.

Figure 10.

Simulated Net Monthly Impact on Households by Income Brackets.

3.5. Industry Support and Competitiveness Mechanisms

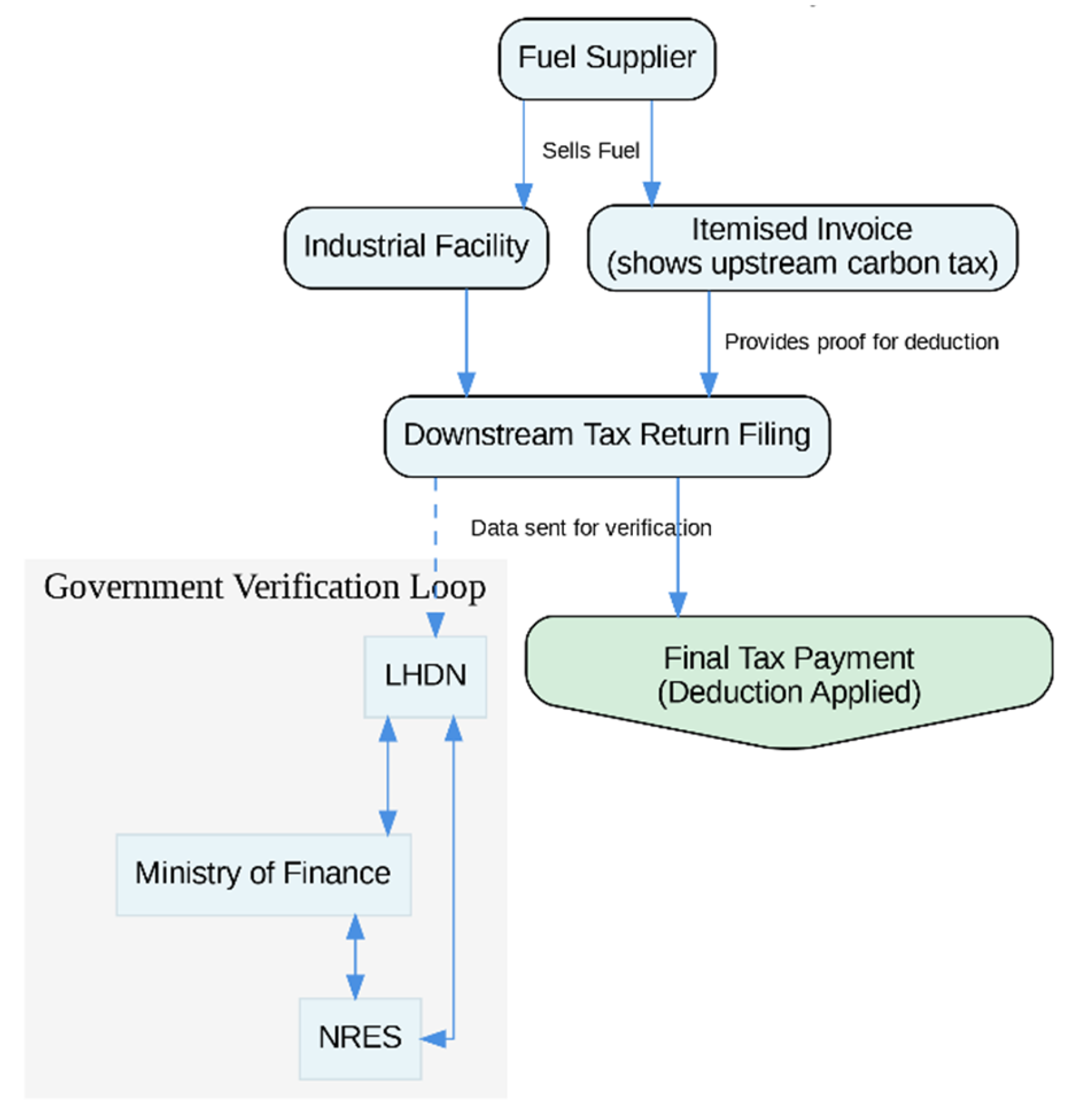

To mitigate the impact on industry and prevent carbon leakage, three key support mechanisms are built into the framework. First, a Double Taxation Prevention Mechanism will be established to ensure no emission is taxed twice under the hybrid upstream-downstream model. This will be achieved through a transparent and automated tax credit system designed for administrative simplicity. Drawing on international precedent, the system will feature a direct deduction process for facilities liable under the downstream tax. Fuel suppliers will be mandated to clearly itemise the carbon tax component on invoices, allowing liable entities to use this documentation as direct evidence for a deduction when filing their emissions tax returns through a digital reconciliation system. To safeguard fiscal integrity, a robust data-sharing process between the Ministry of Finance, LHDN, and NRES will be implemented to verify all credits claimed.

Figure 11.

Proposed Double Taxation Prevention System.

Figure 11.

Proposed Double Taxation Prevention System.

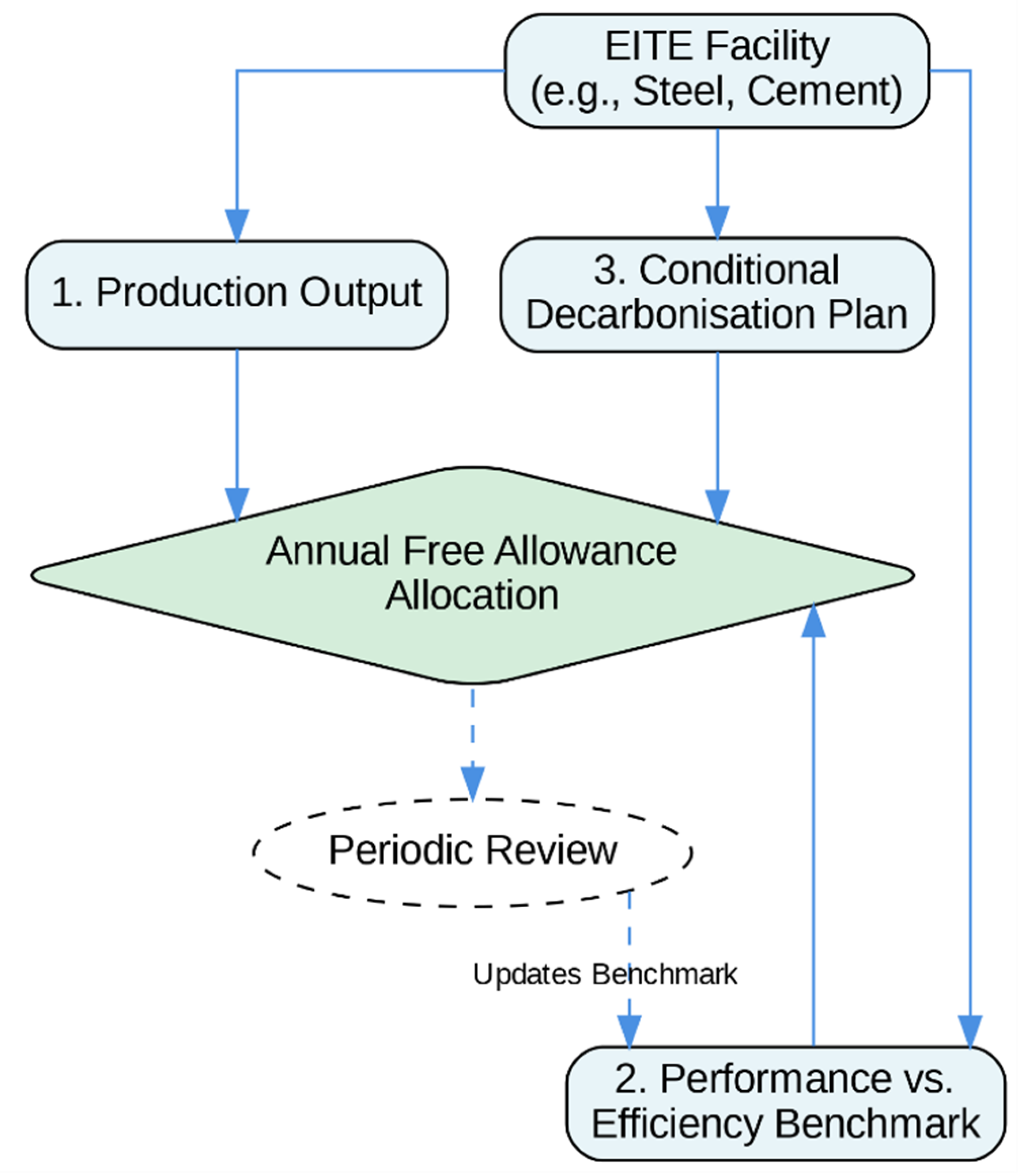

Second, to ease the transition for Emissions-Intensive, Trade-Exposed (EITE) sectors like steel and cement, the framework will provide temporary Transitional Allowances. Rather than a simple allocation, this support will be delivered through a dynamic and performance-based system designed to actively drive innovation. Free allowances will be distributed based on a facility’s production output and its emissions intensity relative to a stringent efficiency benchmark, set against the top-performing installations in the sector. These allocations will be adjusted periodically to reflect changes in production levels, preventing over-allocation and rewarding early action. Furthermore, to ensure this support directly contributes to long-term climate goals, a portion of the allowances may be made conditional upon companies developing and implementing credible, verified decarbonisation roadmaps.

Figure 12.

Proposed Dynamic Transitional Allowances.

Figure 12.

Proposed Dynamic Transitional Allowances.

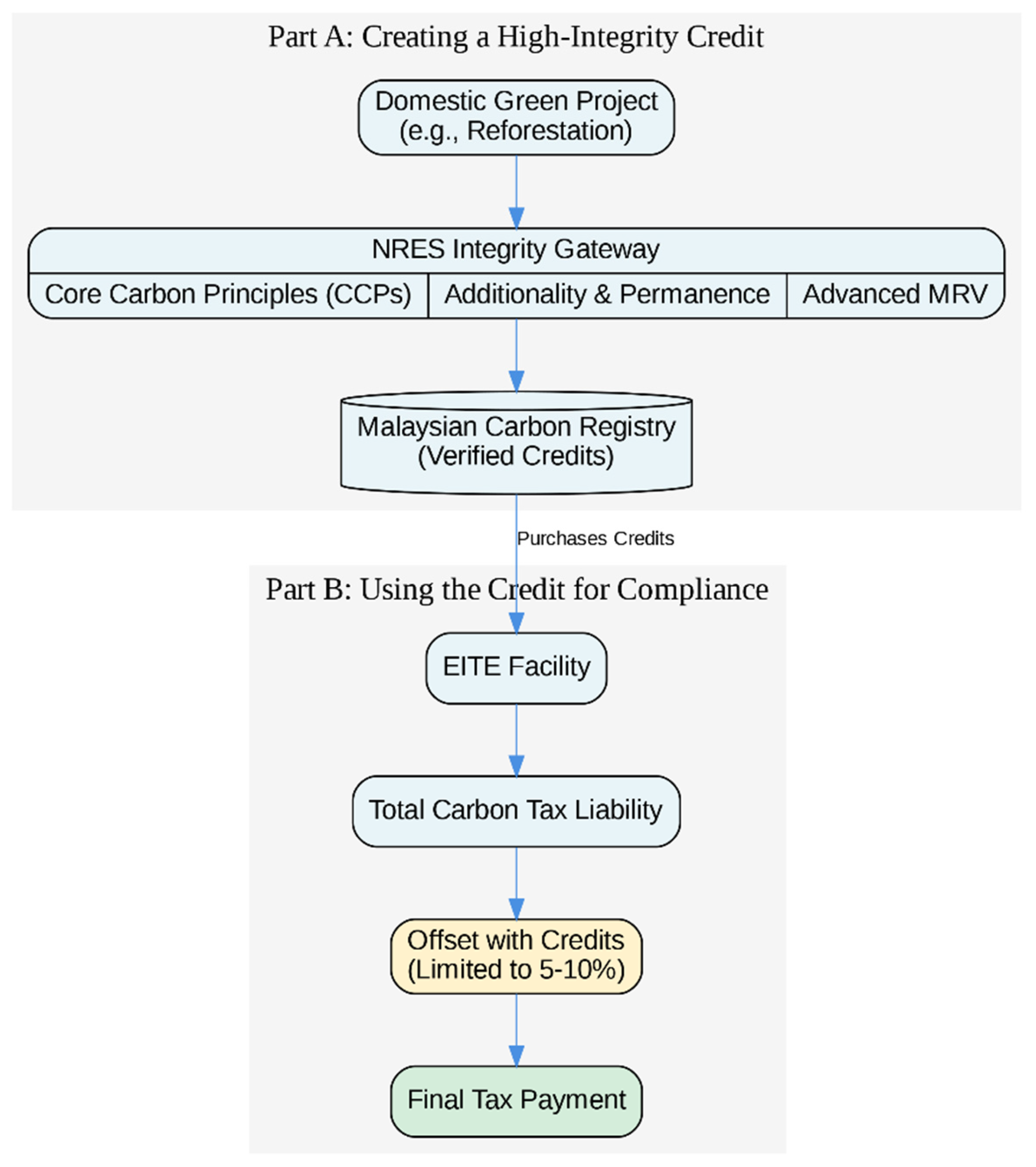

Third, a Carbon Offset Mechanism will be included to provide compliance flexibility and stimulate investment in high-quality local green projects. Companies will be permitted to use domestically generated carbon credits to offset a limited portion (e.g., 5-10%) of their tax liability. To ensure environmental integrity and prevent greenwashing, this mechanism will be protected by stringent guardrails. All eligible credits must be approved by NRES and meet the high-integrity standards of the Core Carbon Principles (CCPs). NRES will operationalise these principles by creating a public registry of approved projects, defining rigorous criteria for project “additionality” and “permanence,” and mandating advanced Monitoring, Reporting, and Verification (MRV) technologies. This ensures that only real, verified emissions reductions are counted towards compliance.

Figure 13.

Proposed High Integrity Credit Flow.

Figure 13.

Proposed High Integrity Credit Flow.

4. Analysis & Discussion

4.1. Case Study: Application in the Steel Sector

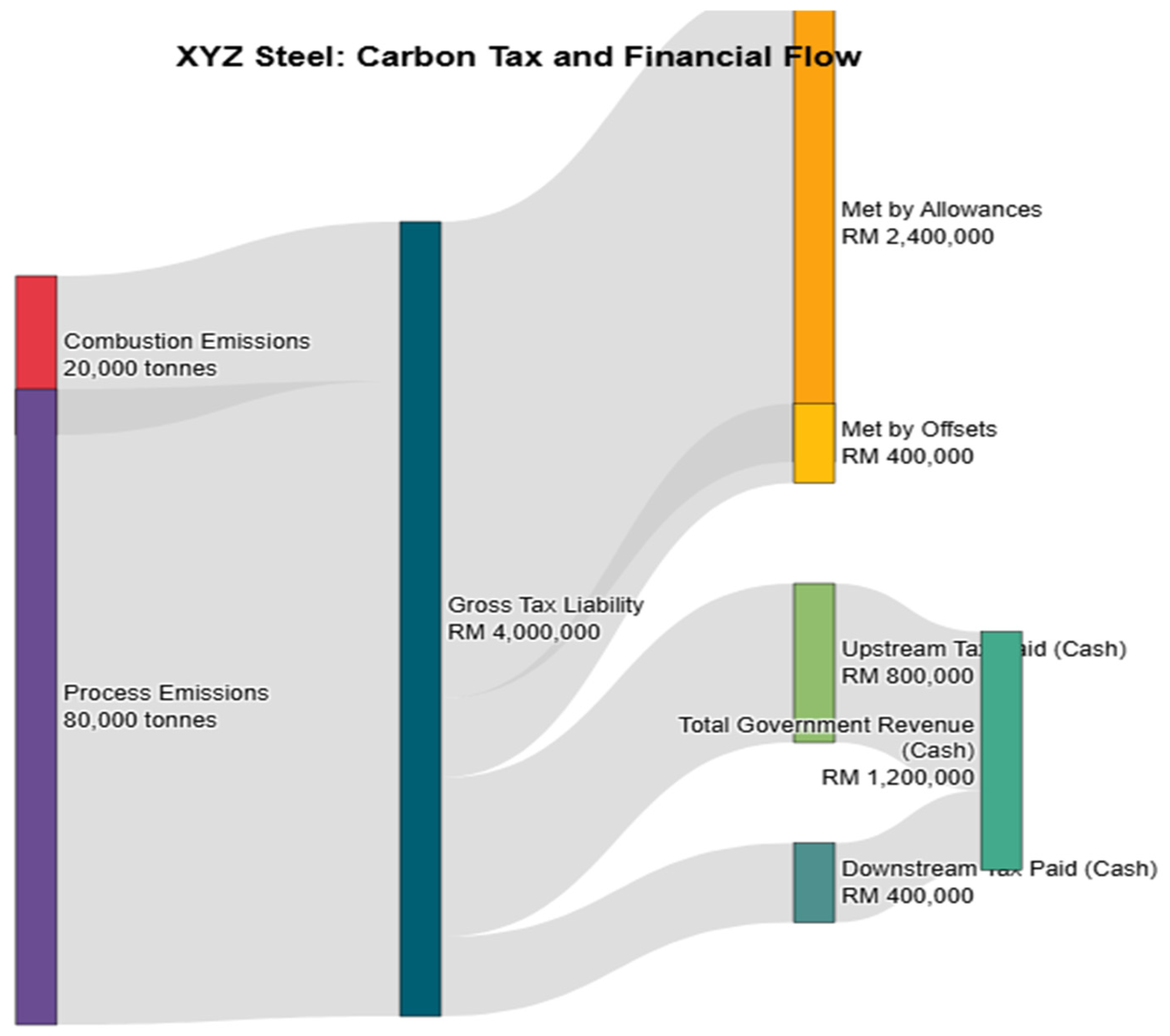

To illustrate the practical application of the proposed carbon tax framework, a hypothetical case study of “XYZ Steel,” a mid-sized steel mill in Malaysia, is considered. This example demonstrates how the various components of the system would function in a real-world industrial setting.

The process begins with the Monitoring, Reporting, and Verification (MRV) phase. At the start of the compliance year, XYZ Steel registers on the MyCARR portal and submits its Monitoring Plan. This plan details its specific emissions sources, which include natural gas for heating and process emissions resulting from the use of carbon as a reductant. Throughout the year, the company diligently tracks its fuel consumption and production data. Following the conclusion of the year, XYZ Steel calculates its total emissions and submits its Annual Emissions Report through the MyCARR portal. To ensure accuracy and credibility, an independent auditor accredited by the National Registration of Emission Sources (NRES) conducts a Third-Party Verification (TPV) of the submitted data, which is then finalized in the registry.

The verified report indicates that XYZ Steel emitted 100,000 tonnes of CO₂ equivalent (CO₂e). With an initial carbon tax rate set at RM40 per tonne, the company’s gross tax liability amounts to RM4,000,000. However, the framework includes several support mechanisms to ease the financial burden on industries. As a trade-exposed entity, XYZ Steel is granted a Transitional Allowance that covers 60% of its emissions in the first year. This allowance shields 60,000 tonnes of emissions from taxation, reducing the liability by RM2,400,000. Furthermore, the company receives a credit for the upstream excise tax already paid on its natural gas consumption, which is calculated to be RM800,000, preventing double taxation. Consequently, XYZ Steel’s net tax liability is reduced to RM800,000, calculated as RM4,000,000 (Gross Liability) - RM2,400,000 (Transitional Allowance) - RM800,000 (Upstream Tax Credit).

To manage its remaining tax obligation, XYZ Steel opts to utilize the Carbon Offset Mechanism. The company purchases 20,000 high-integrity carbon credits from a domestic forestry project listed on the Bursa Carbon Exchange. Although these credits are equivalent to 20,000 tonnes of CO₂e, the framework imposes a 10% limit on the use of offsets against gross emissions. Therefore, XYZ Steel can only use 10,000 credits, which corresponds to a value of RM400,000 at the established tax rate, to meet its liability. This case study effectively demonstrates how the layered mechanisms of MRV, allowances, tax credits, and offsets interact to establish a firm yet fair compliance pathway. This integrated approach incentivizes companies to reduce their emissions while simultaneously safeguarding their competitiveness in the market.

Figure 14.

Sankey Diagram of Compliance Journey for XYZ Steel.

Figure 14.

Sankey Diagram of Compliance Journey for XYZ Steel.

Figure 15.

Simulation on How Carbon Offset Mechanism Reduces Tax Liability.

Figure 15.

Simulation on How Carbon Offset Mechanism Reduces Tax Liability.

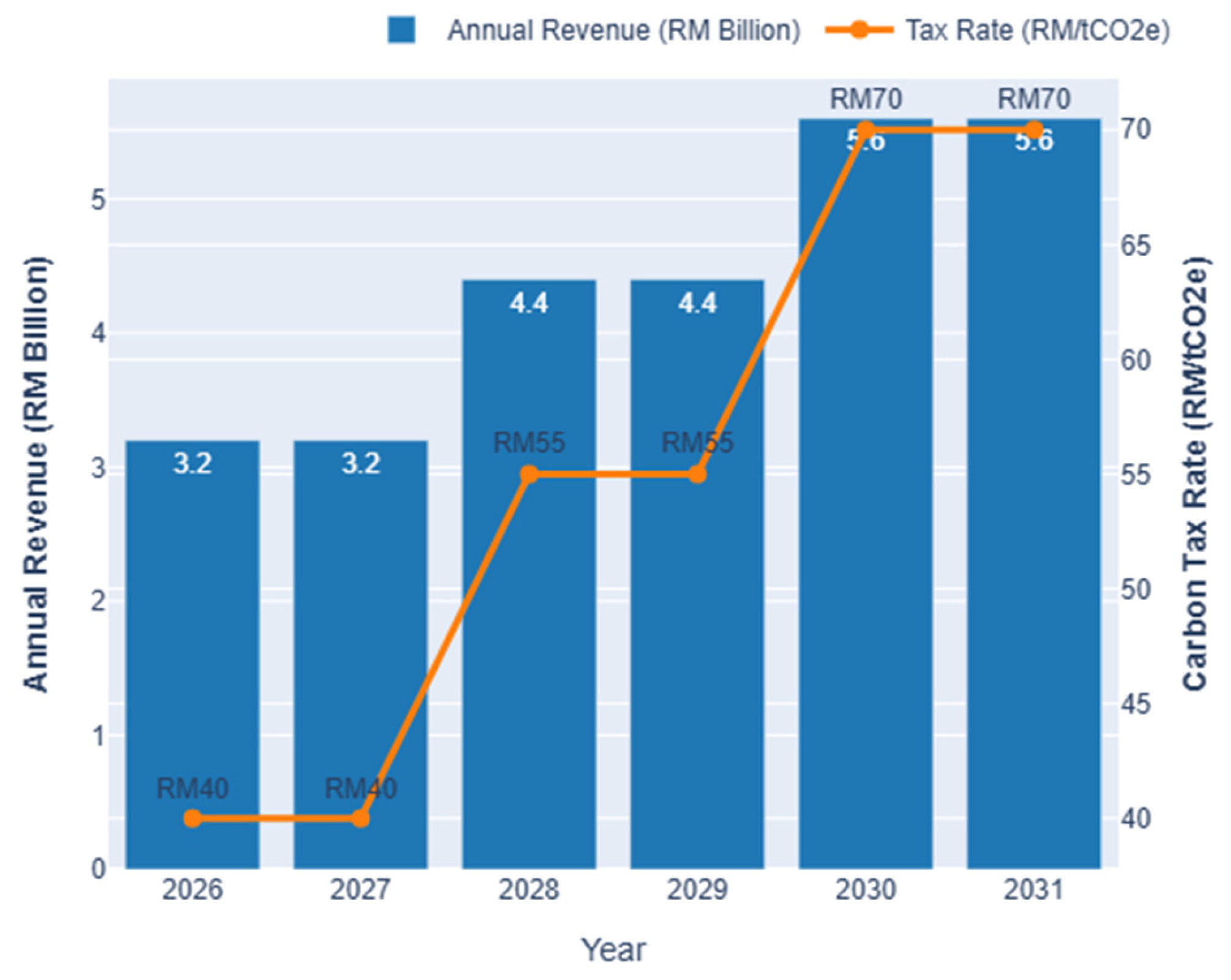

4.2. Fiscal and Economic Impact Projections

The proposed carbon tax framework outlines a phased implementation designed to generate significant and predictable revenue. Projections for the 2026-2031 period indicate the tax will start at RM40 per tonne for the first two years, generating an estimated annual revenue of RM3.2 billion. The rate is scheduled to increase to RM55 per tonne in 2028, boosting annual revenue to a projected RM4.4 billion. A further increase to RM70 per tonne is set for 2030, which is expected to raise annual revenue to RM5.6 billion. This substantial fiscal resource is earmarked for funding the Green Transition Fund and providing carbon dividends to the public.

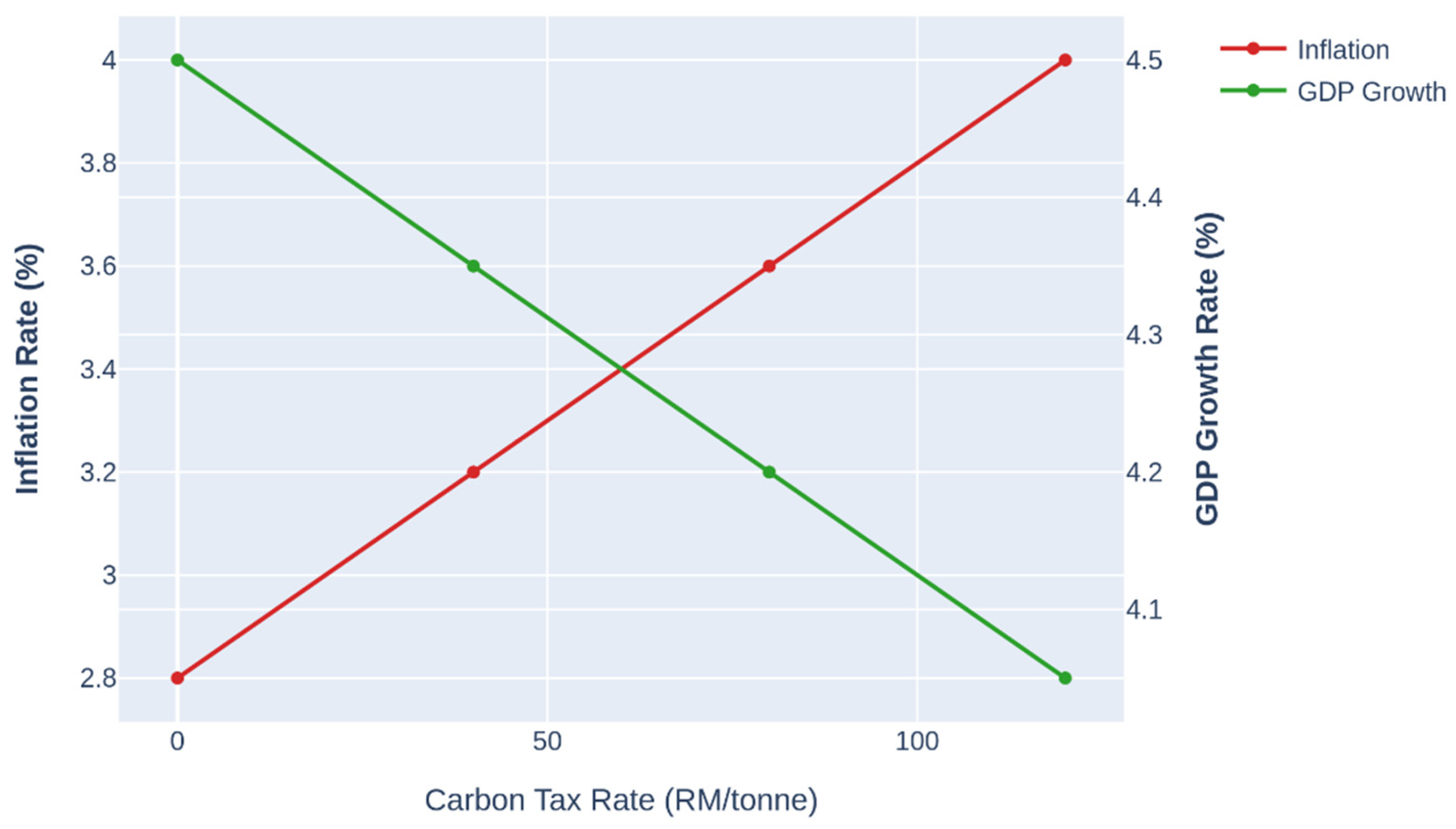

While a carbon tax can have inflationary effects, this framework’s design actively mitigates this risk. The revenue recycling mechanism, through direct cash transfers, is structured to protect vulnerable groups. The carbon dividend is projected to almost entirely offset the increased cost of living for low-income households (earning up to RM 5,249/month), while providing partial relief to middle-income households (earning between RM 5,250 and RM 11,819/month).

Macroeconomically, the policy acknowledges a trade-off. The same sensitivity analysis indicates that the tax may exert a slight drag on GDP in the short term, with the growth rate expected to decrease from 4.5% to 4.1% as the tax rate approaches RM100 per tonne. This short-term impact is expected to be counteracted over time by the productive investments made through the Green Transition Fund. These investments are intended to spur innovation, create green jobs, and enhance national energy efficiency. This approach aligns with findings from broad literature reviews which suggest that the macroeconomic impacts of a well-designed carbon tax in developing countries are typically modest and manageable (Van Parys & Faehn, 2021).

Figure 16.

Projected Revenue and Scheduled Tax Rate Increases (2026-2031).

Figure 16.

Projected Revenue and Scheduled Tax Rate Increases (2026-2031).

Figure 17.

Conceptual Macroeconomic Sensitivity Analysis.

Figure 17.

Conceptual Macroeconomic Sensitivity Analysis.

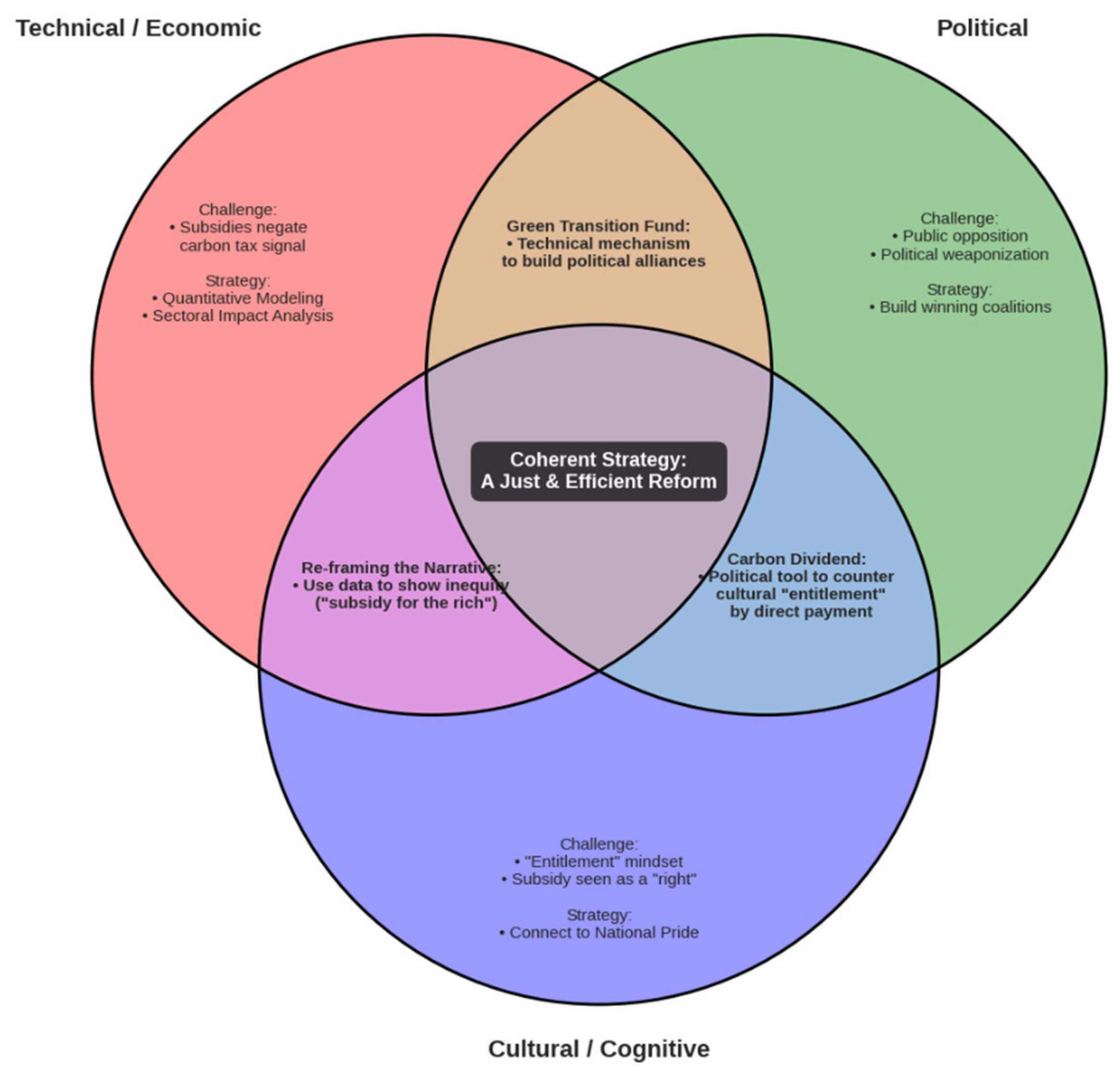

4.3. Risk Analysis and Long-Term Governance: A Triple Lens Approach

A robust framework must not only be well-designed but also resilient to long-term risks. To ensure its durability and effectiveness, we will analyze key governance challenges through the Triple Lens Framework, a methodology prominently associated with the MIT Sloan School of Management. This analytical approach posits that complex strategic challenges must be viewed through three interconnected perspectives: the Technical/Economic, the Political, and the Cultural/Cognitive. By applying this framework, we can develop a more holistic understanding of potential risks and design governance structures that are technically sound, politically viable, and culturally resonant.

The most significant risk to the framework is the potential for policy incoherence, specifically the conflict between a carbon tax and existing fuel subsidies. A comprehensive analysis using the Triple Lens Framework reveals the multi-faceted nature of this challenge. From a technical/economic standpoint, the risk is clear and quantifiable, as the carbon tax signal is rendered ineffective if negated by a larger, opposing subsidy. As the IMF (2021) argues, “getting energy prices right is a prerequisite for efficient climate policy.” The technical solution, therefore, requires a clear roadmap for subsidy rationalization. Politically, blanket subsidies represent a major obstacle, as their removal risks significant public backlash. The governance solution must therefore include astute mechanisms, such as a “Carbon Dividend,” to manage the interests of potential “losers” and mitigate political fallout. The deepest risk, however, is cultural/cognitive. In Malaysia, fuel subsidies are often perceived as an entitlement. A long-term governance strategy must therefore include a sustained campaign to reframe this narrative, shifting the focus from a “lost benefit” to a progressive investment in a more competitive and modern nation.

To ensure the framework remains credible and fair over time, two additional governance pillars are essential. Firstly, to manage economic and scientific uncertainty, the framework must incorporate a dynamic rate review mechanism. From a technical perspective, a pre-scheduled, transparent review by the Carbon Council provides economic soundness and allows for adjustments based on the latest data. Politically and culturally, this process builds long-term investor certainty and public trust by mirroring international best practices and reinforcing a culture of evidence-based governance.

Secondly, to foster investor confidence, a transparent and impartial dispute resolution framework is critical. To ensure this, a clear, multi-tiered system could be established to handle disagreements fairly and efficiently. Initially, for disputes of a technical nature concerning emissions data or monitoring methodologies, companies would first appeal to a dedicated technical appeals committee within NRES. Subsequently, for disagreements regarding tax assessments or credit calculations, companies would utilize the existing statutory appeal bodies, such as the Pesuruhjaya Khas Cukai Pendapatan for matters under LHDN, or the Tribunal Rayuan Kastam for issues related to JKDM. Finally, to ensure full access to legal recourse, decisions from these tribunals could still be challenged in the High Court, aligning the framework with established legal processes. Benchmarking this framework against globally respected rules, such as those of ICSID (2022), signals that the system is not subject to arbitrary influence but is grounded in a culture of procedural fairness, assuring all parties of a predictable and just process.

Figure 18.

Triple Lens Framework on Fuel Subsidy Challenge.

Figure 18.

Triple Lens Framework on Fuel Subsidy Challenge.

5. Implementation Framework

A well-designed policy requires a clear, detailed, and robust implementation plan. This section outlines the suggested governance structure, the necessary legislative actions, and a phased, actionable timeline designed to bring the Malaysian Carbon Tax framework into reality effectively and smoothly.

5.1. Governance Structure

The framework’s success is contingent upon a clear division of roles and a strong mandate for the key government bodies involved. It is suggested that the governance structure be formalized by establishing a new, high-level Carbon Council to act as an independent advisory and oversight body with a clear legislative mandate. To ensure balanced and expert advice, its members should be drawn from academia, key industry sectors, climate science experts, and civil society organizations, supported by a permanent secretariat to ensure it operates with authority and technical credibility, like successful international models like the New Zealand Climate Change Commission (New Zealand Climate Change Commission, 2024). Concurrently, the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Sustainability (NRES) should be designated as the central technical regulator, receiving dedicated funding to manage its responsibilities, which include operating the MyCARR digital MRV system and setting technical standards. The Inland Revenue Board (LHDN) and Royal Malaysian Customs Department (JKDM) are proposed as the primary collection agents, and it is suggested that a formal inter-agency committee be established between these bodies and NRES to streamline data sharing, ensure consistent enforcement, and prevent tax revenue leakage, leveraging their existing infrastructure while enhancing coordination.

5.2. Legislative Framework

To provide legal certainty and a durable foundation for a national carbon pricing policy, two key legislative actions are strongly recommended. The first is the enactment of a new, standalone Carbon Tax Act of Parliament. It is crucial that this primary legislation codify all core components of the framework, including the scope of sectoral coverage, detailed Monitoring, Reporting, and Verification (MRV) requirements, the powers of a new Carbon Council, and the legal establishment of a Green Transition Fund and potential Carbon Dividend. This Act should also specify the rights and obligations of covered entities. It is further suggested that the drafting process includes a mandatory public consultation period to enhance transparency and secure a broad stakeholder buy-in.

The second required action is a targeted amendment to the Excise Act 1976 to legally empower the Royal Malaysian Customs Department (JKDM) to collect an upstream tax on fossil fuels. This amendment should explicitly establish the carbon content of fuels as a dutiable item, an approach consistent with established international legal practice (Kreiser & Ashiabor, 2013). It should be drafted in close consultation with legal and customs experts to avoid implementation loopholes and ensure a robust collection mechanism.

Under the authority of this amended Excise Act, a specific ‘Levi Karbon’ (Carbon Levy) could then be introduced and detailed through subsidiary legislation, such as an amendment to the Perintah Duti Eksais 2022. The levy rate would be determined by a transparent formula: Levy Rate (RM/unit) = Emission Factor (tCO₂e/unit) × Carbon Price (RM/tCO₂e). To illustrate, using a proposed initial carbon price of RM40.00 per tonne of CO₂e for petrol (HS Code 2710.12), the calculation would be 0.0023 tCO₂e/liter × RM40.00/tCO₂e, resulting in a levy of RM0.092 per liter, which would be added to any existing duties.

The collection of this carbon levy would be seamlessly integrated into the current customs framework managed by JKDM. For importers, the levy would be declared and paid at the point of entry using Borang Kastam No. 1. Concurrently, licensed local manufacturers, such as oil refineries, would remit the levy payment directly to JKDM before their products are released into the domestic market. This comprehensive approach ensures that the high-level legal framework established by a new Carbon Tax Act is translated into a practical, enforceable, and effective carbon pricing instrument.

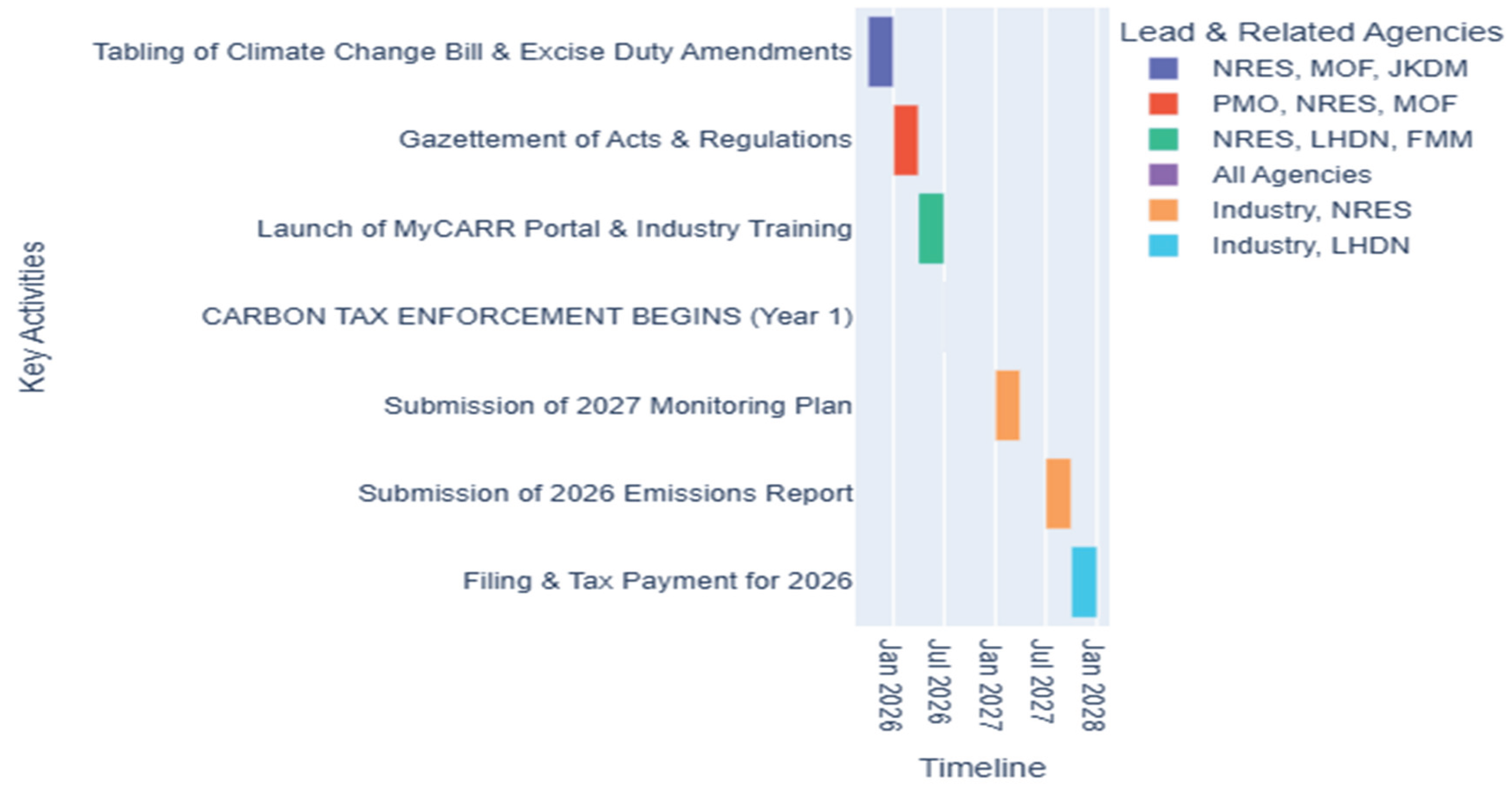

5.3. Implementation Timeline

A phased and realistic four-year timeline is proposed to ensure a smooth transition from policy design to full implementation. The implementation process commences in 2025, which is designated as the foundation and consultation phase. During this initial year, the focus will be on establishing the Carbon Council and its secretariat, forming a legislative committee to draft the necessary laws, and engaging in intensive, structured consultations with all relevant stakeholders. The second year, 2026, is dedicated to legislation and capacity building. The primary objective for this year is the tabling and passing of the new Carbon Tax Act and its related amendments in Parliament. Concurrently, development and testing of the MyCARR digital system will begin, alongside the rollout of a nationwide training program for industries that will be affected by the new tax. The third year, 2027, will serve as a systems trial and familiarization period. This will feature a mandatory but no-penalty “dry run” of the MyCARR system, allowing companies to adapt to the new reporting requirements and providing an opportunity for the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Sustainability (NRES) to resolve any technical issues with dedicated support. Finally, January 2028 will mark the official launch of Phase 1 of the Carbon Tax. This date signifies the beginning of the first official compliance period for emissions generated in the 2028 calendar year. The first tax payments under this new framework will subsequently be due in the first half of 2029, followed by a post-launch review to address any immediate challenges and ensure the system is functioning as intended.

Figure 19.

Proposed Implementation Timeline (2025-2028).

Figure 19.

Proposed Implementation Timeline (2025-2028).