1. Introduction

The urgency of the climate crisis demands rapid and decisive action. According to scientific projections, even optimistic scenarios predict that global surface temperature will continue to rise until at least the middle of this century. Without drastic reductions in CO

2 and other greenhouse gas emissions in the coming decades, exceeding the 1.5°C and 2°C thresholds is inevitable [

1]. This entails immense risks, as many of the changes that have already occurred and will occur in the future, particularly in the ocean, at the ice sheets, and in global sea levels, will be irreversible over centuries to millennia [

1]. These so-called tipping points mark critical thresholds in the climate system, beyond which irreversible processes are triggered [

2].

In addition to planetary tipping points, there are also so-called social tipping points. These refer to sub-areas of the global socio-economic system in which decisive changes can take place that lead to a rapid reduction in anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions. Otto et al. (2020) have identified six key social tipping points based on expert surveys and an extensive literature review, including the education system [

3]. These tipping points are particularly significant because the tipping of such a subsystem can be triggered by targeted “social tipping interventions”, such as the promotion of climate education and social engagement. Such interventions could bring about a rapid transition to a global state of net zero greenhouse gas emissions [

3].

Studies indicate that, while general knowledge of climate change is present in a majority of people, it still has room for significant improvement [

4,

5]. Germany will fail to meet its climate targets if no substantial changes take place [

6]. Thus, there is a gap between the German population's awareness of the climate crisis and their willingness to engage in and to support climate-protective action. This gap is also evident in the study “Environmental Awareness in Germany 2022,” a representative population survey conducted by the German Federal Environment Ministry and the German Federal Environment Agency with over 2000 participants aged 14 and up [

7]. Results showed that the knowledge level, measured by environmental cognition, is significantly more pronounced than the action level. This study was also able to show that environmental behavior and environmental cognition increase with the level of education [

7], therefore raising the central question of how to move from knowledge of the problem to active and long-term action and an associated change in one's own behavior.

This question is the subject of numerous models in environmental psychology [

8,

9,

10]. Most models share the basic assumption that sustainable behavior starts with an awareness of the problem and a resulting intention. Various theoretical approaches have been developed that explain different drivers of the motivation for sustainable behavior: On the one hand, there are norm-activation models, which interpret sustainable behavior as pro-socially motivated patterns of behavior [

11]. Moral norms play a central role here, which arise from strong self-related commitments to reduce harm to other people, animals, ecosystems, etc. often arise from a discrepancy between one's own actions and social norms [

9,

11]. Several studies have shown this link between moral norms and sustainable behavior [

12,

13,

14].

On the other hand, there are rational choice models, which explain sustainable behavior as driven by self-interested motivation, including, for example, the theory of planned behavior proposed by Ajzen (1991) [

8]. The basic assumption here is that people strive to receive rewards and avoid punishments. The decision for or against a behavior is based on a consideration of the perceived positive and negative consequences for one's own well-being. In addition to personal attitudes, the expectations of significant others and the perceived behavioral control, i.e. the confidence in one's own ability to carry out the behavior, also play a role [

8,

9].

More recent approaches, such as the model of environmental behavior developed by Bamberg and Möser (2007), attempt to combine both approaches [

9]. They explain the intention to engage in sustainable behavior as an interplay of various factors from both models. While these models describe in detail which variables influence behavioral intention, the temporal process of action generation itself is largely neglected. Martens's Integrated Action Model goes one step further and regards sustainable action as a multistage process [

15]. However, the model ends with the execution of the action, without examining the transition to long-term action. Furthermore, the model provides no information about specific interventions and instruments for determining the phase in which a person currently finds themselves.

1.2. Theoretical framework – The transtheoretical model of behavior change (TTM)

One model that considers the entire process of action generation, from lack of intention to long-term action, is the Transtheoretical Model of Behavior Change (TTM) [

16]. This stage model was developed primarily for health prevention, such as smoking [

17,

18], diabetes [

19] or vaccinations [

20], but also with topics such as mobile phone use [

21] or academic performance [

22,

23]. What all studies have in common is that they aim at fundamental and targeted changes in individual behavior. Even if people want to adjust their behavior towards climate-friendly action, fundamental changes in habitual action sequences are required. In this situation, similarly to smoking cessation, it is important to recognize undesirable behavior and thinking patterns and to change them permanently. In all cases, the individual is required to reevaluate their previous behavior and establish new routines. Despite these parallels, TTM has been applied to sustainable behavior in only a small number of studies to date [

10,

24].

In the TTM, an individual's current level of readiness to act and the type of support for behavior change are linked. Depending on how far an individual has progressed in thinking about a problem, they have different information needs and experience different interactions as reinforcing and motivating [

25].

In essence, the TTM describes behavioral changes in individuals as a dynamic process characterized by actively moving through several stages that build on each other. These so-called “stages of change” (SoCs) represent the central construct of the model and represent the temporal dimension of the change process. As the stages progress, the actors experience changes in their attitudes, emotions, and behavior [

22,

25].

The model typically divides the process of behavior change into five discrete stages (precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance). The number of stages can vary depending on the variables examined, so a sixth stage, the stabilization stage, is added in studies of smoking cessation [

25].

Precontemplation: In this stage, the affected individuals have no motivation to change their behavior in the near future, often due to a lack of information, denial of the risks, or resignation after previous failed attempts. This stage is considered the most stable in the model because the individuals simply ignore or repress the consequences of their potentially problematic behavior, intentionally avoid dealing with it, and thus do not see a need to change their lifestyle. Without intervention, the probability of moving on to the next stage is low [

10,

25].

Contemplation: The individual is aware of their problematic behavior and motivated to change it, but is still undecided about the exact change. Although there is awareness of the problem, the decision to act in the near future often does not materialize because the pros and cons of changing the behavior are considered to be balanced [

10,

25].

Preparation: In this stage, the individual is highly motivated to change the problematic behavior. They express a clear intention to change and plan steps to implement them in their own lives. In this stage, they might even have experimented with some tentative changes [

10,

25].

Action: The individual has a strong will and takes active steps to change behavior in their personal environment. In this stage, the focus is on overt, observable behavior. Due to the difficulty of persisting, concrete ideas for action and experiences of success and confirmation through the visible perception of one's own actions [

10,

25].

Maintenance: After active change, the goal is to maintain the new behavior. The individual consolidates the strategies from the action stage and actively tries to prevent a relapse [

10,

25].

As a rule, the SoCs are not passed through linearly, but there are always relapses into earlier stages, especially from the action or maintenance stage. This can be triggered, among other things, by the fact that corresponding planned actions do not lead to the desired result or there are external changes in one's own environment that cause priorities, processes, or structures in everyday life to shift, thus also causing actions to be temporarily discontinued. The change process often takes a spiral form: after a relapse, people return to earlier stages but can learn from their experiences and move forward with better strategies [

25].

The TTM also describes the strategies that are necessary to move from one stage to the next. People who want to motivate others to act and support them in changing their behavior need these strategies to work with individuals who are in different stages in order to move them “forward” in the SoCs [

25].

Two other central constructs of the TTM are the decision balance and the self-efficacy. The decision balance describes the weighing of the subjectively perceived advantages and disadvantages of a behavioral change and influences the progress through the stages. In the early stages, the disadvantages often predominate, while in the later stages, the advantages are weighed more heavily. Self-efficacy describes a person's conviction in their ability to successfully carry out a certain behavior to achieve a certain result, even in difficult situations. This affects the initiation and choice of behavior, the level and duration of the effort, and how the person deals with stressful situations. Both constructs are important indicators of progress in the change process and predictors of the success or failure of behavioral changes [

25,

26].

In the present study, we focused on the construct SoCs, as it is instrumental to identify an individual’s motivation for behavior change, and guides subsequent measures that are appropriate to support the individual to move on to the next step.

1.2. Operationalization of the Stages of Change

In research on behavior change, there are a variety of questionnaires that measure the SoCs in relation to specific behaviors [

20,

23,

27]. For climate-conscious action, the Climate Change Stages of Change Questionnaire (CCSOCQ) was developed by Inman et al. (2022), which measures five discrete stages of behavioral change in the context of climate change [

10]. The study demonstrated that the TTM is a useful framework for conceptualizing the process of change in relation to sustainable action in the climate crisis and that CCSOCQ is a valid questionnaire for measuring SoCs in Portuguese-speaking parts of the world [

10].

However, to date, there has been no validated German-language questionnaire that captures the process of change towards sustainable behavior based on the SoCs. Such an instrument would be of great importance, however, as the TTM enables the development of targeted interventions that are tailored to the individual's respective stage. It also allows progress within the stages to be measured empirically.

The SoCs can be conceptualized as follows for sustainable action in the climate crisis: In the precontemplation stage, people are not yet motivated to actively contribute to a more sustainable future. They do not recognize the problem of the climate crisis and therefore do not see a necessity to change. People consciously avoid dealing with the climate crisis. In the contemplation stage, individuals have consciously dealt with the climate crisis and possible courses of action. Though they do not plan to take immediate action for sustainable change, yet, they are aware of the problem of the climate crisis and possible solutions, but are still skeptical about immediate changes in their living environment because they do not yet feel ready for them. In the preparation stage, individuals are highly motivated to contribute to solving the climate crisis by acting sustainably. They develop an intention to act and to implement sustainable action in their living environment in concrete terms. Some might even have taken the first steps towards change. In the action stage, individuals actively establish sustainable actions and behavior. In doing so, they achieve their goals and sustainably change structures as they engage in concrete implementation measures. In the final maintenance stage, people have adopted sustainable actions as a habit for a long time. Action strategies are further consolidated, and support structures are created. In addition, precautionary measures are taken to prevent a relapse [

10,

25].

1.3. Research Question and Hypothesis

The TTM provides the theoretical framework for the process of behavior change. Inman et al. (2022) successfully demonstrated that this model can be applied to both students and teachers in Portugal to describe behavior change in relation to climate-conscious action [

10]. On this basis, targeted interventions can be developed that motivate people to act more sustainably and thus help to address the climate crisis. Building on this work, we addressed the issue of whether the questionnaire is also valid in the German version. Therefore, the central aim of our study was to translate the CCSOCQ and validate it as a German-language instrument. This should prove the psychometric suitability of the questionnaire for German-speaking countries, in order to be able to empirically measure the change process towards sustainable behavior.

Inman et al. (2022) were able to demonstrate a five-factor structure using factor analysis, which corresponds to five discrete stages, to measure behavioral change in the context of climate change [

10]. This factor structure must also be verifiable for the German version. The following hypothesis could be formulated for this study:

H1: The factor structure of the original can be replicated in the German translation. Five discrete stages can also be found in the German version.

Self-efficacy represents a closely related construct to test convergent validity. The TTM predicts a permanent increase in self-efficacy across the stages up to the action stage. It is low in the precontemplation stage because the person has little confidence in their ability to change. As intention formation begins, self-efficacy slowly starts to increase, but the person often remains uncertain. In the preparation stage, the person shows growing confidence and develops specific plans for change, which is why self-efficacy increases rapidly. At the action stage, self-efficacy reaches its peak as the new behavior is already being implemented and only increases slowly or not at all up to the maintenance stage [

25]. In the study by Muroi and Bertone (2019), the authors used a parameter to measure the self-efficacy of participants concerning environmentally friendly behavior towards climate change [

28]. This parameter “Individual's perceived capability to enact change” (IPCEC) was translated into German and used for the present study to assess the self-efficacy of the participants. The following hypotheses could be stated for self-efficacy:

H2: The self-efficacy of individuals increases significantly over the Stage of Change up to the action stage, where it reaches its maximum and only rises slightly from there.

H3: The self-efficacy is significantly higher in the maintenance stage than in the precontemplation stage.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

A total of 815 participants took part in the study and completed the questionnaire in full. To be eligible for this study participants were required to be enrolled at a German higher education institution and had to be aged 18 or higher, therefore not requiring parental consent Data were collected over a period of 35 days as part of an online questionnaire between the end of January and the beginning of March 2020. Some interviews had to be removed from the data set for the following reasons: no consent for data analysis was given (

n = 4), respondents indicated that they had not taken the survey seriously (

n = 60), and respondents had chosen to take the interview in English (

n = 20) Ultimately,

N = 731 interviews were included in the analysis, which corresponds to an inclusion rate of 89.7%. A significant proportion of the students surveyed (89.5%) studied at our own institution. All 29,800 students who were enrolled at the time were invited to participate through a bulk mailing. In addition, the study was actively promoted via the university's social media accounts. To check the representativeness of the sample from our own institution we compared their statistics with students from other German universities (

n = 77) (see

Table 1). No significant differences were found, indicating that the sample from the group of students at our university is representative of a group of students at a German university (see

Table 1).

The mean age of the students surveyed was 23.8 years (

SD = 4.9) with 68.7% identifying as female, 27.5% as male, and 2.7% as gender non-conforming, with further 1.1% not providing information on their gender identity. It should be noted here that the proportion of female students at our university is 60% [

29].

2.2. Instruments

2.2.1. Climate Change Stages of Change Questionnaire (CCSOCQ)

The present study builds on the Climate Change Stages of Change Questionnaire (CCSOCQ) developed by Inman et al. in 2022 [

10]. based on their conceptual understanding of the TTM. The study by Inman et al. (2022) showed that the self-report questionnaire has adequate psychometric properties. The original questionnaire was administered in Portuguese and published in English. For the present study, the items were translated into German. This process was carried out in a group of four students of educational science as part of their bachelor theses [

30,

31,

32,

33]. The translation was carried out in several steps: First, the students translated the items independently, then machine translations were consulted using the programs DeepL and ChatGPT. To control for deviations from the original, the items were back-translated into English and errors were corrected [

31].

The questionnaire comprises a total of 15 items, which form five subscales with three items each. Each subscale represents a stage of behavior change: precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance. The answers are recorded on a five-point Likert scale from 1 (totally disagree) to 5 (totally agree) [

10].

The present study used the full set of 15 items, including one item (I really need to do something to prevent climate change), which was discarded in the original study due to unclear factor loadings [

10]. For the German translation, this item was edited in line with the concept of the contemplation stage in the model. This was done to check whether the item in the German version of this stage could be assigned to a stage with more clarity [

31,

32].

2.2.2. The Questionnaire for Measuring Self-Efficacy - Individual's Perceived Capability to Enact Change (IPCEC)

The “Individual's perceived capability to enact change” (IPCEC) proposed by Muroi and Bertone (2019) was used to assess the participants' self-efficacy regarding the usefulness of their own climate-friendly actions [

28]. In the original study, the questionnaire included a section on attitudes with 16 items that assessed attitudes towards climate change. Of these, 8 items measured the participants' self-efficacy, which fall under the parameter “perceived ability of the individual to bring about change” concerning environmentally friendly behavior in the face of climate change [

28]. Pertaining items were selected based on the guidelines for constructing self-efficacy scales from Banduras (2006) [

34]. These focus on the perception of individual abilities to change behavior despite the complex challenges of climate change. Covariables such as self-esteem, locus of control, and outcome expectancies were deliberately omitted [

28].

The eight items on self-efficacy relevant for this study were tested and published in English in the original study. An example of such an item would be: “I don t believe my behavior and everyday lifestyle contribute to climate change” [

28] (p. 143). For the present study, they were translated into German by the group of four students of educational science according to the procedure described in the previous section [

30,

31,

32,

33]. The original six-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree) was adapted to a five-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) for the current study. This adjustment was primarily intended to ensure better comparability with the CCSOCQ, which also implements a five-point Likert scale.

2.3. Data Collection and Statistical Analysis

Data collection was carried out using an online questionnaire presented through SoSci Survey. Two pre-tests were run before the survey was published. The first pre-test was carried out with eight participants, including two of the authors of this study. Based on the feedback, adjustments were made to the questionnaire. A second pre-test then confirmed the effectiveness of the changes made [

31]. The statistical program StataBE 17 V5 was used for the factorial analysis of the data. Further data analysis was carried out using the statistical program SPSS Statistics 29 V5. Data were examined for factorial and convergent validity and internal consistency in a multi-stage process and were descriptively analyzed.

2.3.1. Factorial Validity

The confirmatory factor analysis aimed to examine whether the same factor structure as in the original Portuguese study by Inman et al. (2022) could be replicated in the present sample [

10]. Since the factor structure was already predetermined by the original study, a confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to check whether the factor structure also applies to this study. In this factor analysis, a rotation analysis was carried out using the Quartimin-Oblique method. The maximum likelihood method was used as the estimation method. The number of factors was set at five, in line with the study by Inman et al. (2022) [

10].

2.3.2. Internal Consistency

Internal consistency was examined using Cronbach's alpha coefficient. Since this is a multidimensional questionnaire, Cronbach's alpha coefficient was calculated separately for each subscale. This included both the individual stages of the TTM and the subscale of self-efficacy.

2.3.3. Descriptive Statistics

To determine SoCs, the common algorithm for classifying participants into subgroups according to the study by Inman et al. (2022) was used [

10]. For each subgroup, the average score of the item scale from 1 to 5 was calculated. The highest average value of a subscale determines the assignment to a stage in the TTM. If several subscales had the same average value, the higher stage of change was assumed.

For the descriptive statistics, the percentage distribution of the individual participants to the different SoCs was calculated. In addition, the Z score profiles for the individual stages were calculated to enable a more detailed analysis.

2.3.4. Convergent Validity

To test convergent validity, self-efficacy was used as a closely related construct. For this purpose, the self-efficacy of the individual participants was determined using the IPCEC questionnaire [

28]. The scores were calculated as sum scores resulting in a value between 8 (lowest self-efficacy) and 40 (highest self-efficacy). In this way, the average self-efficacy for the participants in each stage could be determined.

A one-way ANOVA was used to test whether self-efficacy differ significantly between the SoCs followed by planned contrasts. In addition, the effect size was determined using the Eta-squared in order to evaluate the significance of the differences.

3. Results

3.1. Factorial Validity

The factor loadings of the confirmatory factor analysis are shown in

Table 2. Results of the analysis confirmed the five-factor structure. The items showed the strongest factor loading on the theoretically expected factors as in the original study [

10]. One exception was item C3, which, despite linguistic adjustment, again showed only a small loading of .32 on the factor “Contemplation”. The loadings of this item were similarly distributed across all factors. Since this item also did not show a larger load on any other factor, as it did in the original study by Inman et al. (2022), it was excluded from the study. For item M3, a small factor loading of .34 was also found at maintenance stage [

10]. However, since the factor loadings on the other factors were significantly lower, it was decided to keep this item in the analysis.

3.2. Internal Consistency

Table 3 shows the Cronbach's alpha coefficient for all measurements. Internal consistency for the scales of the German version of the CCSOCQ were good (

α > .80) for the subscales preparation and action, and acceptable for precontemplation and maintenance (

α > .70). For the subscale contemplation, only poor internal consistency could be returned, as in Inman et al.’s (2022) original study. This might be due to the fact that this scale was composed of only two items [

35]. Internal consistency for self-efficacy was questionable at (

α = .63).

3.3. Descriptive Statistics

Table 4 shows the distribution of the participants in the sample across the different SoCs, as well as the means and standard deviations for the scores achieved by these participants at each stage on the Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

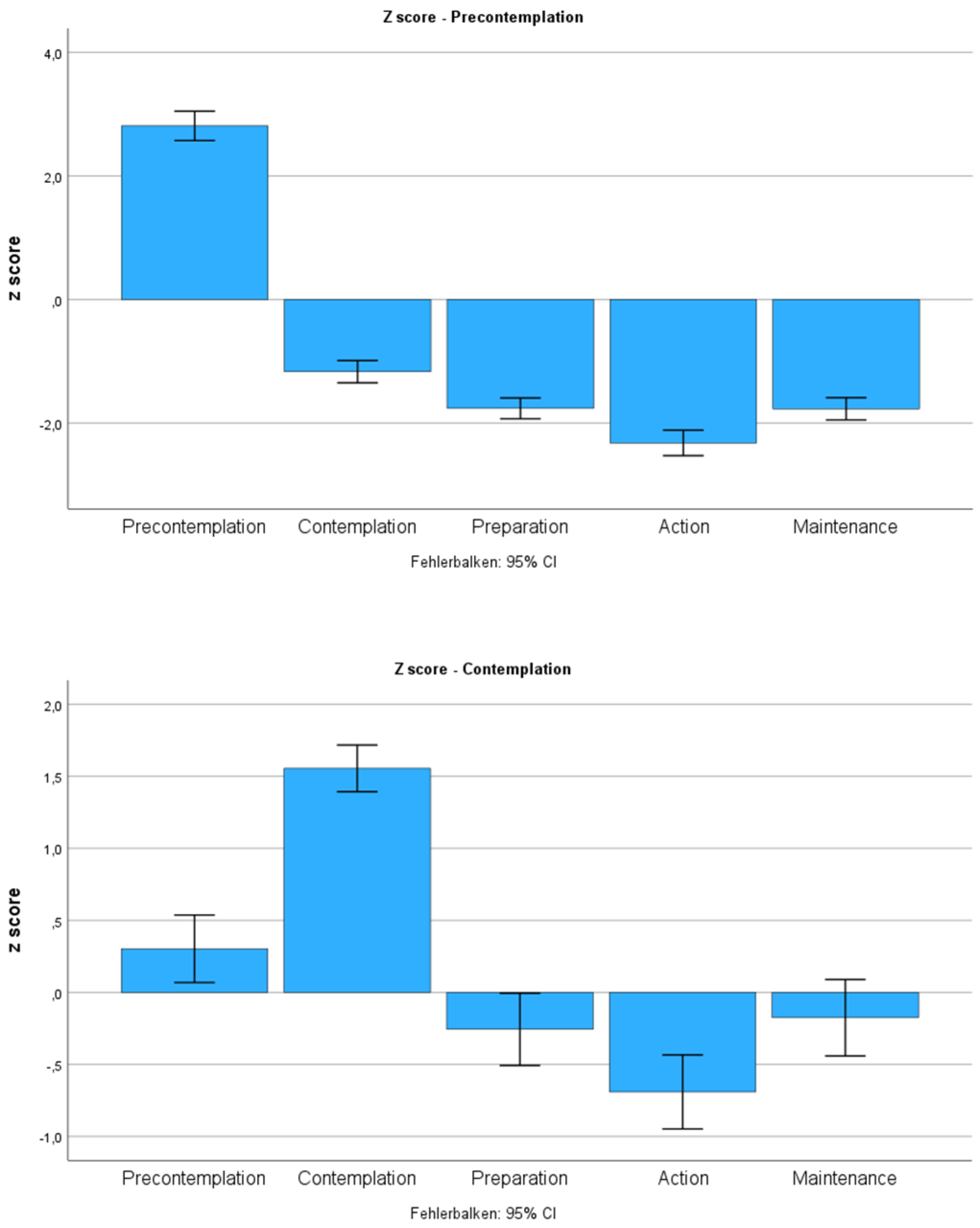

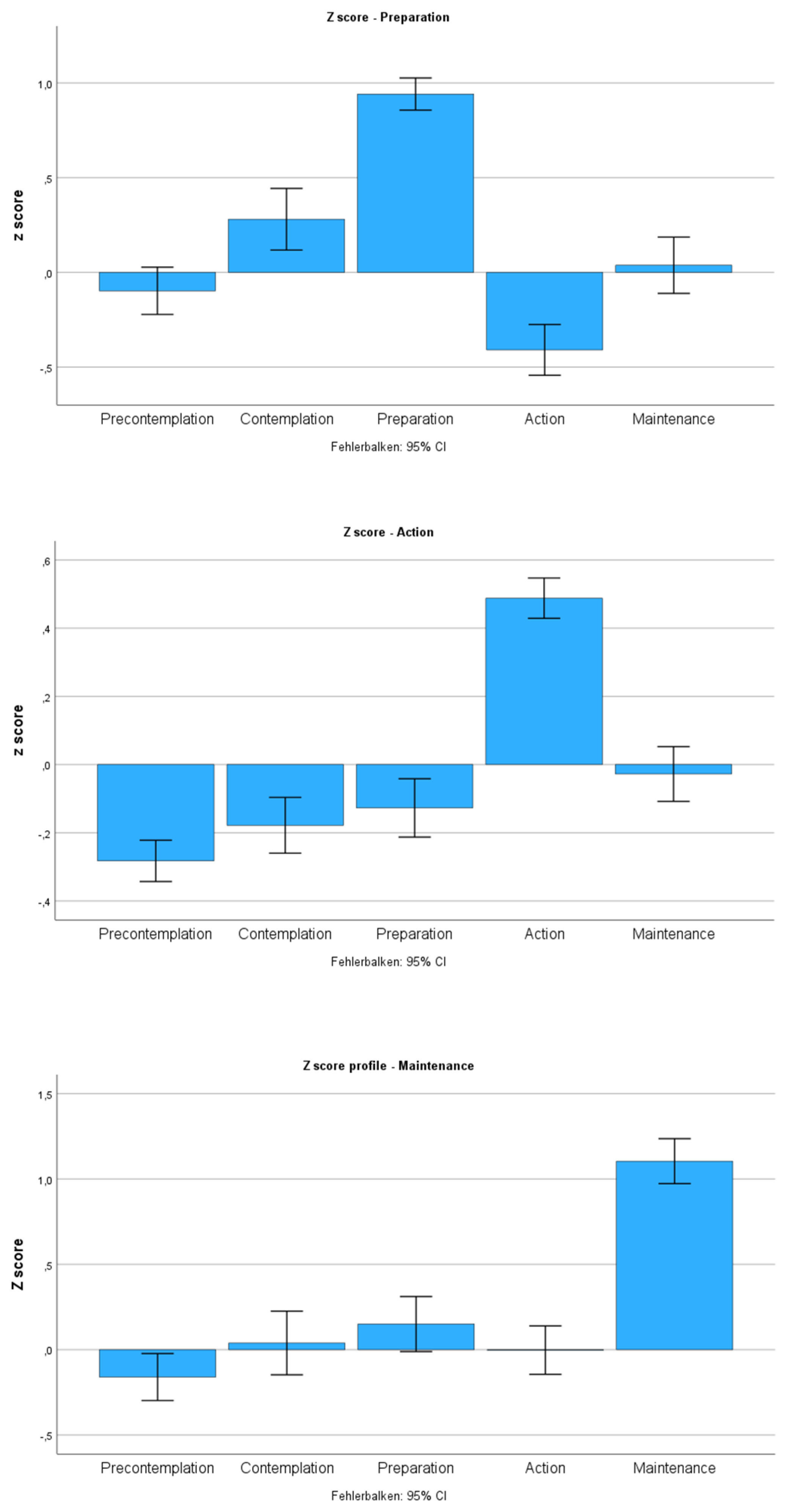

Participants were assigned to a stage of change according to their high score. To validate the assignment, the Z profiles for all five stages were inspected. The Z score profiles of the individual stages are visualized in

Figure 1. This demonstrates that the average values I for the stage of change to which participants had been assigned, was significantly higher than their values in the other stages.

3.4. Convergent Validity

The average values of the self-efficacy for the different stages of the TTM are shown in

Table 5. There was a steady increase in self-efficacy from the precontemplation stage to the action stage, with a slight decrease in the last stage, which still reached a slightly higher level than the preparation stage.

Table 6,

Table 7 and Table 8 show the results returned from the one-way ANOVA. Significant differences between the means of the individual subgroups corresponding to our model of the SoCs were found (see

Table 6). The paired comparison with the Bonferroni adjustment between the means of the individual stages also showed that the significance was mostly below .05 and that there were significant differences between the mean differences. Exceptions were the comparisons between stages contemplation and preparation and between stages preparation and maintenance, where no significant differences were found (see

Table 7).

The effect sizes of the one-way ANOVA, where calculated as eta-square value of .25 [

36] which indicates a large effect of the differences in self-efficacy between the stage.

4. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to validate the German language version of the CCSOCQ to empirically capture the process of change toward sustainable behavior against the background of the TTM. The evaluation of a student sample showed that the German-language version of the CCSOCQ questionnaire has the appropriate psychometric properties and can therefore be used as a diagnostic tool of the readiness for behavioral change in the field of sustainability. The questionnaire is suitable for determining the stage of behavioral change in individuals within the framework of the TTM.

The hypothesis that the factor structure of the original study by Inman et al. (2022) could be replicated was supported by the confirmatory factor analysis [

10]. The same 5-factor structure was identifiable, which speaks for factorial validity. The five identified factors could thus be mapped onto the SoCs. With the exception of one item, all items in the questionnaire could also be assigned to the same stages as in the original study.

The IPCEC questionnaire was used to test convergent validity by recording self-efficacy at different SoCs. Two hypotheses were formulated for this purpose. In line with the hypothesis, we found evidence that self-efficacy increases up to the action stage and remains relatively constant or even decreases in the final maintenance stage. Self-efficacy measures differed significantly between the stages precontemplation and contemplation, preparation and action, as well as action and maintenance. In contrast, self-efficacy in the stages contemplation and preparation was comparable, indicates a continuous transition between these two stages. This seems plausible since motivation formation in the contemplation stage and intention formation in the preparation stage are strongly linked.

The observation of a continuous increase up to the action stage and a slight drop of self-efficacy in the last stage is line with previous research. The observed decrease in self-efficacy in the maintenance stage can be explained by the fact that long-term sustainable action has become a habit for the actors so that they no longer actively think about their actions and also no longer consciously reflect on their self-efficacy.

The third hypothesis, that self-efficacy is significantly higher in the maintenance stage than in the precontemplation stage, was also confirmed. Here, too, a significant difference between the stages could be determined. To put sustainable behavior into practice over time builds a self-reinforcing cycle as individuals act in line with their goals, see the positive effects, and experience accomplishment and meaning.

The confirmation of the hypotheses about the interplay between self-efficacy with respect to climate friendly behavior and the stage of change indicated that convergent validity is present in the questionnaire. The Z score profiles indicated that the stages can be considered as sufficiently distinct, thus confirming the theoretical assumptions inherent in the TTM. Participants consistently achieved high scores in the stages assigned to them, while the mean values for the other stages were comparatively low. The distinction between profiles of participants in the preparation stage and in the contemplation stage was less pronounced. This might indicate that the transition between these stages tends to be more fluid. It would be a matter of future research to confirm if the step forward from the contemplation to the preparation stage is easier to take than between other stages.

The distribution of the sample participants across the individual stages of the TTM showed that 67.5% of the participants were in the action or maintenance stage, while only 6.2% could be assigned to the precontemplation stage. This meant that 94% of the participants reported that they were aware of the climate crisis.

The present study also revealed a gap between awareness about the climate crisis and active action to address the crisis, albeit less pronounced than in the population survey by Grothmann et al. (2023) [

7]. A reasoning for this could be because the sample of the present study was not representative of the German population as a whole, but rather consisted exclusively of university students. Students generally have a high level of education, which often correlates with more sustainable behavior. This assumption is supported by the study by Grothmann et al. (2023), in which the parameter for environmental behavior increased with the level of education [

7].

Looking at the maintenance stage, it was found that only 11.8% of participants showed long-term sustainable action. This value is in a similar range to the results of the study by Grothmann et al. (2023), in which 17% of respondents stated that they were actively involved in environmental and climate protection. Despite some deviations compared to the representative population survey by Grothmann et al., there were some similarities between the two studies, which confirmed the applicability of the CCSOCQ as a German-language questionnaire for analyzing the process of change toward sustainable action in the climate crisis [

7].

To sum up, the results of this study provide evidence for the validity of the German version of the CCSOCQ questionnaire. It can be used to identify the degree to which individuals are ready to change their behavior for more sustainable and climate friendly action. In line with the TTM it would now be a necessary next step to identify appropriate support measures for groups in each stage to stimulate progress.

4.2. Limitations and Perspectives for Further Research

In spite of the encouraging results of the study, some limitations must be addressed.

One of the first limitations is the study's methodological approach. Limitations arise from the use of questionnaires to obtain self-reports from the participants. This method carries the risk of cognitive distortions due to self-serving self-perception or gaps in memory, leading to an inaccurate assessment of one's own sustainable behavior or attitudes towards climate change. The effect of social desirability plays a particularly important role in this context: Participants tend to present themselves as more climate-conscious in their answers because this behavior is socially positively evaluated. In addition, errors can occur if participants tend towards extreme or middle answer options regardless of the content. To minimize these errors, data could also be collected from other reports and observations [

37].

Another limitation concerns the selection of the participants in the sample. Only students from German institutions of higher education were interviewed. This is not very representative of the German population as a whole, since it is only a specific subgroup with a certain level of education and a certain age range. It is therefore only possible to a limited extent to transfer the results to other social groups. The size of the sample was also much smaller compared to the original study by Inman et al. (2022) [

10]. Although this was sufficient to analyze the psychometric properties of the questionnaire overall, the analysis of the individual stages, especially the stages precontemplation and contemplation, showed that the sample size of 45 and 53 participants, respectively, was very small. This increases the risk of measurement errors and limits the significance of the results in these ranges.

Further limitations affect the CCSOCQ questionnaire. The biggest weakness of this questionnaire lies in the recording of the contemplation stage. This stage was only recorded with two items because one item had to be excluded due to an unclear factor loading. The problem with only two items was that this stage could not be assessed in a valid and reliable way. Further studies would need to adapt the wording of this item, so that the subscale for the stage of intention formation can be consolidated. A possible adaption to the phrasing could be: “I am beginning to understand that I have to do something about climate change.” This adaptation emphasizes the development over time of an emerging awareness of the problem, which is characteristic of this stage.

The last limitation concerns the IPCEC questionnaire, which, like CCSOCQ, was translated into German. While only the reliability was examined in the German translation, the convergent validity was not checked against another related questionnaire. It therefore remains unclear whether the translation has the same validity as the English-language original. However, the converging results that were returned are encouraging the assumption of construct validity.

Overall, the study provides a sound basis for further research with the validated German CCSOCQ questionnaire. A next step for future perspectives would be to use connect the diagnosis of the SoCs with a strategic intervention to facilitate behavioral change. The TTM suggests ten strategies, that support progress through the different stages of the model. Building on this, the challenge for future research is to interpret and transfer the strategies that have worked for behavior change in other areas to behavior change in the area of sustainable action. One possible research focus is to identify which strategies individuals used at the respective stages. Based on this, longitudinal studies can be developed to analyze how individuals progress through the stages over time, especially when they receive targeted interventions that are based on the strategies of the TTM – for example, embedded in educational programs.

5. Conclusions

The study aimed to validate a questionnaire for analyzing the SoCs towards sustainable action in the climate crisis for German-speaking countries and thus to make a scientific contribution to promoting sustainable behavior. The theoretical basis for this was the TTM, which defines five stages which individuals go through for effective behavior change. Building on the research by Inman et al. (2022) the Climate Change Stages of Change Questionnaire (CCSOCQ), was translated into German and tested for its psychometric properties in German Higher Education students. The study confirmed that the TTM also provides a useful framework in German-speaking countries for analyzing change processes towards sustainable action to address the climate crisis. Overall, the results showed that the translated German version of the CCSOCQ questionnaire is a valid and reliable instrument for determining the SoCs in the field of sustainable and climate friendly behavior.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.G. and M.I.; methodology, M.I.; software, T.G.; data curation, T.G.; writing—original draft preparation, T.G.; writing—review and editing, T.G., M.I. and K.W.; visualization, T.G..; supervision, M.I and K.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The authors confirm that the study was conducted in compliance with the practice as specified by the Declaration of Helsinki and as approved by the Ethics Committee of the Institute of Psychology. Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the method of the study as participation was voluntary, non-invasive, completely anonymous and did not involve deception or manipulation.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CCSOCQ |

Climate Change Stages of Change Questionnaire |

| IPCEC |

Individual's perceived capability to enact change |

| SoC |

Stage of Change |

| TTM |

Transtheoretical Model |

References

- IPCC Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, United Kingdom, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Lenton, T.M.; Held, H.; Hall, J.W.; Lucht, W.; Rahmstorf, S.; Schellnhuber, H.J. Tipping elements in the Earth´s climate system. PNAS 2008, 105(6), 1786–1793. [CrossRef]

- Otto, I.; Donges, J.F.; Cremades, R.; Bhowmik, A.; Hewitt, R.J.; Lucht, W.; Rockström, J.; Allerberger, F.; McCaffrey, M.; Doe, S.S.P.; Lenferna, A.; Morán, N.; van Vuuren, D., P.; Schellnhuber, H.J. Social tipping dynamics for stabilizing Earth´s climate by 2050. PNAS 2020, 117(5), 2354–2365. [CrossRef]

- Europäische Investitionsbank. EIB-Umfrage: Ältere kennen sich in Deutschland besser mit dem Klimawandel aus als Jüngere [EIB survey: Older people in Germany know more about climate change than younger people]. Available online: https://www.eib.org/de/press/all/2024-253-older-generations-in-germany-more-knowledgeable-about-climate-change-than-younger-generations-eib-survey-finds (accessed on July 14, 2025).

- Götz, M.; Mendel, C. Was Kinder und Jugendliche in Deutschland über den Klimawandel wissen [What children and Adolscents in Germany know about climate change]. TELEVIZION 2024, 37(1), 1– 7.

- Expertenrat für Klimafragen (ERK). Feststellung zur Prüfung der Treibhausgas-Projektionsdaten 2024. Feststellung gemäß §16 Abs. 2 in Verbindung mit §12 Abs. 1 Satz 4 Bundes-Klimaschutzgesetz [Assessment for testing greenhousegas-projection data 2024. Assessment according to §16, sec. 2 and §12, sec. 1, sentence 4 Federal Climate Action Act]. Available online: https://expertenrat-klima.de/content/uploads/2024/07/ERK2024_Feststellung-zur-Pruefung-Projektionsdaten-2024.pdf (accessed on July 14, 2025).

- Grothmann, T.; Frick, V.; Harnisch, R. Umweltbewusstsein in Deutschland 2022. Ergebnisse einer repräsentativen Bevölkerungsumfrage [Environmental awareness in Germany in 2022: results of a representative population survey]. Bundesministerium für Umwelt, Naturschutz, nukleare Sicherheit und Verbraucherschutz (BMUV), Umweltbundesamt (UBA): Berlin, Germany, 2023.

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 1991, 50(2), 179–211.

- Bamberg, S.; Möser, G. Twenty years after Hines, Hungerford, and Tomera: A new meta-analyses of pro-environmental behaviour. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2007, 27(1), 14–25. [CrossRef]

- Inman, R.A.; Moreira, P.A.S.; Faria, S.; Araújo Marta, D.C.; Pedras, S.; Lopes, J.C. An application of the transtheoretical model to climate change prevention: Validation of the climate change stages of change questionnaire in middle school students and their schoolteachers. Environmental Education Research 2022, 28(7), 1003–1022. [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Normative influences on altruism. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 1977, 10, 221–279.

- Guagnano, G.A.; Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T. Influences on attitude–behaviour relationships: A natural experiment with curbside recycling. Environment and Behaviour 1995, 27(5), 699–718. [CrossRef]

- Hunecke, M.; Blöhbaum, A.; Matthies, E.; Höger, R. Responsibility and environment—Ecological norm orientation and external factors in the domain of travel mode choice behaviour. Environment and Behaviour 2001, 33(6), 845–867. [CrossRef]

- Thøgersen, J. The ethical consumer. Moral norms and packaging choice. Journal of Consumer Policy 1999, 22(4), 439–460. [CrossRef]

- Martens, T. (2012). Was ist aus dem Integrierten Handlungsmodell geworden? [What happened to the Integrated Action Model]. In. Item-Reponse-Modelle in der sozialwissenschaftlichen Forschung; Kempf, W., Langeheine, R., Eds.; Regener: Berlin, Germany, 2012; pp. 210–229. [CrossRef]

- Prochaska, J.O.; DiClemente, C.C. Stages and Processes of Self-Change of Smoking – Toward An Integrative Model of Change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 1983, 51(3), 390–395. [CrossRef]

- Armitage, C.J.; Arden, M.A. How Useful Are the Stages of Change for Targeting Interventions? Randomized Test of a Brief Intervention to Reduce Smoking. Health Psychology 2008, 27(6), 789–798. [CrossRef]

- Park, M.H.; H.-Y. Song. Transtheoretical model to predict the stages of changes in smoking cessation behavior among adolescents. Frontiers in Public Health 2024, 12, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Kalampakorn, S.; Powwattana, A.; Sillabutra, J.; Liu, G. A Transtheoretical Model-Based Online Intervention to Improve Medication Adherence for Chinese Adults Newly Diagnosed With Type 2 Diabetes: A Mixed-Method Study. Journal of Primary Care & Community Health 2024, 15, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Sacco, A.; Robbins, M.L.; Paiva, A.L.; Monahan, K.; Lindsey, H.; Reyes, C.; Rusnock, A. Measuring Motivation for COVID-19 Vaccination: An Application of the Transtheoretical Model. American Journal of Health Promotion 2023, 37(8), 1109–1120. [CrossRef]

- Noroozi, A.; Mondanizadee, R.; Tahmasebi, R. Effect of Educational Intervention on Reducing Mobile Phone Addiction: Application of Transtheoretical Model. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences 2024, 18(2), 1–10, . [CrossRef]

- Moreira, P.A.S.; Faria, V.; Cunha, D.; Inman, R.A.; Rocha, M. Applying the Transtheoretical Model to Adolescent Academic Performance Using a Person-Centered Approach: A Latent Cluster Analysis. Learning and Individual Differences 2020, 78, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Moreira, P.; Moreira, F.; Cunha, D.; Inman, R.A. The Academic Performance Stages of Change Inventory (APSCI): an Application of the Transtheoretical Model to Academic Performance. International Journal of School & Educational Psychology 2020, 8(3), 199–212. [CrossRef]

- Howell, R.A. Using the transtheoretical model of behavioural change to understand the processes through which climate change films might encourage mitigation action. International Journal of Sustainable Development 2014, 17(2), 137–159. [CrossRef]

- Keller, S.; Kaluza, G.; Basler, H.-D. Motivierung zur Verhaltensänderung. Prozessorientierte Patientenedukation nach dem Transtheoretischen Modell der Verhaltensänderung [Motivation for behavior change. Process-oriented patient education according to the Transtheoretical Model of Behavior Change]. Psychomed 2001, 13(2), 101–111.

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behavioral Change. Psychological Review 1977, 84(2), 191–215. [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.; Franklin, J. The Transtheoretical Model and Study Skills. Behaviour Change 2007, 24(2), 99–113. [CrossRef]

- Muroi, S.K.; Bertone, E. From Thoughts to Actions: The Importance of Climate Change Education in Enhancing Students Self-Efficacy. Australian Journal of Environmental Education 2019, 35(2), 123–144. [CrossRef]

- xxx. Zahlenspiegel 2022/23 [Registrar Report]; xxx Berichtswesen: Mainz, Germany, 2024.

- Braun, M. Eine Anwendung des transtheoretischen Modells auf das Bewusstsein für Nachhaltigkeit: Geschlechterspezifische Unterschiede bei Studierenden. bachelor thesis, Johannes Gutenberg-Universität, Mainz, 2024.

- Cremer, F. Klima retten mit Persönlichkeit? Untersuchungen zum Zusammenhang von Persönlichkeitsmerkmalen und Verhaltensänderung im Klimawandel. bachelor thesis, Johannes Gutenberg-Universität, Mainz, 2024.

- Schuster, L.J. Die Rolle der Selbstwirksamkeitserwartung bei der Handlungsbereitschaft gegen den Klimawandel. bachelor thesis, Johannes Gutenberg-Universität, Mainz, 2024.

- Wieber, C.S. Bildung für nachhaltige Entwicklung: Studie über Verhaltensänderung von Student*Innen im Zusammenhang mit dem Klimawandel anhand des Transtheoretischen Modells. bachelor thesis, Johannes Gutenberg-Universität, Mainz, 2024.

- Bandura, A. Guide for constructing self-efficacy scales. In. Self-efficacy Beliefs of Adolescents; Pajares, F., Urdan, T.S., Eds.; IAP: Charlotte, United States of America, 2006; pp. 307–337.

- Ziegler, M.; Kemper, C.J.; Kruyen, P. Short Scales – Five Misunderstandings and Ways to Overcome Them. Journal of Individual Differences 2014, 35(4), 185–189. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analyses for Behavioral Science, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, United States of America, 1988.

- Döring, N.; Bortz, J. Forschungsmethoden und Evaluation in den Sozial- und Humanwissenschaften [Research Methods and Evaluation in the Social and Human Sciences], 5th ed.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, Germany, 2016.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).