Submitted:

16 July 2025

Posted:

17 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

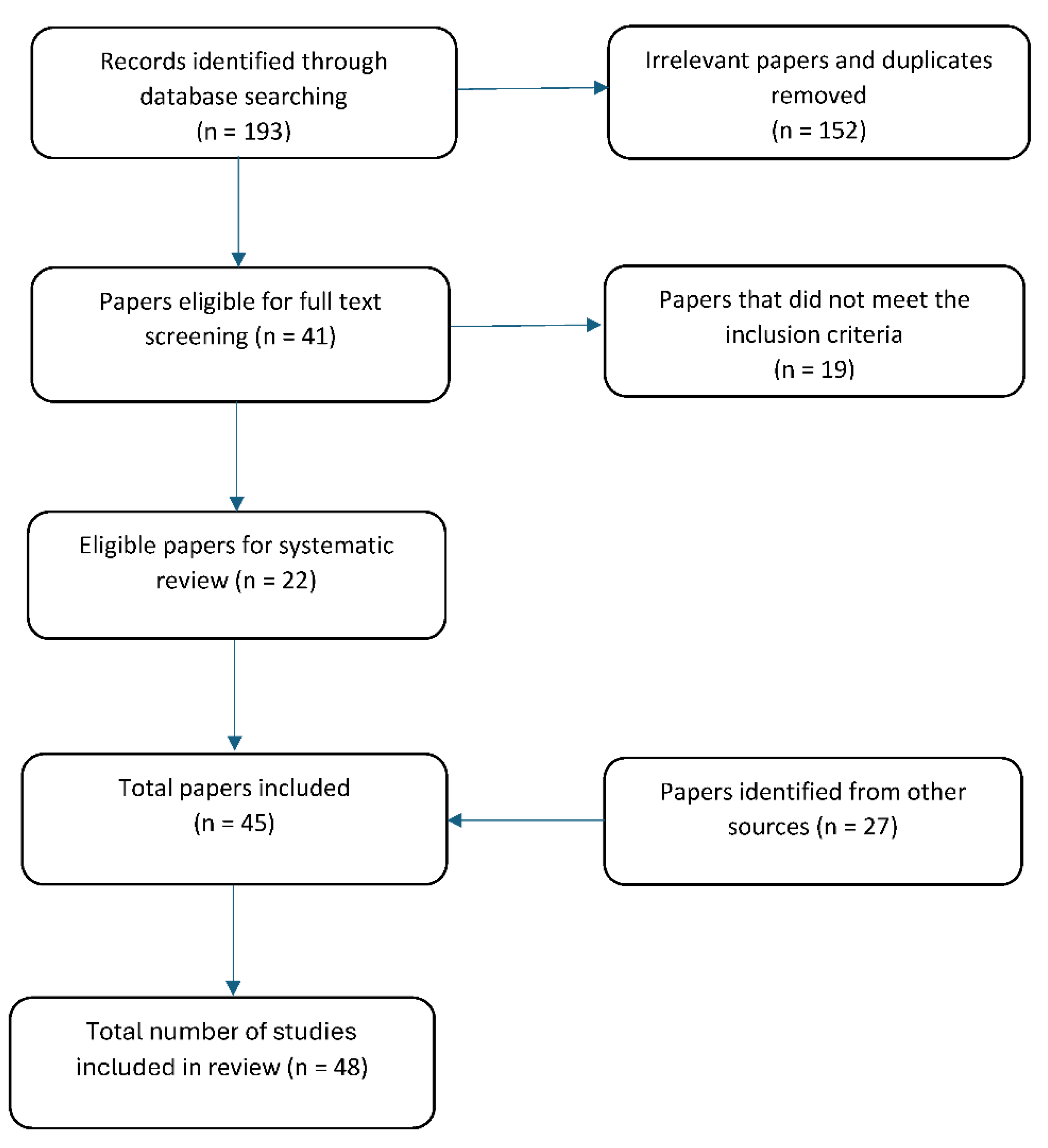

3.1. Database Search

3.2. Leptin and Adiposity in Mammals, Birds, Reptiles and Fish

4. Discussion

4.1. Sub-Eutherian Mammals and Reptiles—Further Research Required

4.2. Birds and Fish – Evidence for No Adipostatic Function

4.3. Eutherian Mammals – Evidence for Species-Specific Functionality

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DEXA | Duel-Energy X-ray Absorptiometry |

References

- Zhang, Y.M. , et al., Positional cloning of the mouse obese gene and its human homologue. Nature 1994, 372, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denver, R.J., R. M. Bonett, and G.C. Boorse, Evolution of leptin structure and function. Neuroendocrinology 2011, 94, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prokop, J.W. , et al., Discovery of the elusive leptin in birds: identification of several 'missing links' in the evolution of leptin and its receptor. PLoS One 2014, 9, e92751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman-Einat, M. , et al., Discovery and characterization of the first genuine avian leptin gene in the rock dove (Columba livia). Endocrinology 2014, 155, 3376–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wauman, J., L. Zabeau, and J. Tavernier, The Leptin Receptor Complex: Heavier Than Expected? Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2017, 8, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosseau, K. , et al., Photoperiodic Regulation of Leptin Resistance in the Seasonally Breeding Siberian Hamster (Phodopus sungorus). Endocrinology 2002, 148, 3083–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Townsend, K.L., T. H. Kunz, and E.P. Widmaier, Changes in body mass, serum leptin, and mRNA levels of leptin receptor isoforms during the premigratory period in Myotis lucifugus. J Comp Physiol B 2008, 178, 217–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sprent, J., S. M. Jones, and S.C. Nicol, Does leptin signal adiposity in the egg-laying mammal, Tachyglossus aculeatus? Gen Comp Endocrinol 2012, 178, 372–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffiths, M. , The Biology of Monotremes, ed. A. Press. 1978, New York.

- Spanovich, S., P. H. Niewiarowski, and R.L. Londraville, Seasonal effects on circulating leptin in the lizard Sceloporus undulatus from two populations. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol 2006, 143, 507–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quillfeldt, P. , et al., Relationship between plasma leptin-like protein levels, begging and provisioning in nestling thin-billed prions Pachyptila belcheri. Gen Comp Endocrinol 2009, 161, 171–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kordonowy, L.L., J. P. McMurtry, and T.D. Williams, Variation in plasma leptin-like immunoreactivity in free-living European starlings (Sturnus vulgaris). Gen Comp Endocrinol 2010, 166, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Froiland, E. , et al., Seasonal appetite regulation in the anadromous Arctic charr: evidence for a role of adiposity in the regulation of appetite but not for leptin in signalling adiposity. Gen Comp Endocrinol 2012, 178, 330–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tauson, A.H. and M. Forsberg, Body-weight changes are clearly reflected in plasma concentrations of leptin in female mink (Mustela vison). Br J Nutr 2002, 87, 101–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yosefi, S. , et al., Lack of leptin activity in blood samples of Adelie penguin and bar-tailed godwit. J Endocrinol 2010, 207, 113–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paolucci, M., M. Rocco, and E. Varricchio, Leptin presence in plasma, liver and fat bodies in the lizard Podarcis sicula- fluctuations throughout the reproductive cycle. Life Sciences 2001, 143, 3083–95. [Google Scholar]

- Salmeron, C. , et al., Effects of nutritional status on plasma leptin levels and in vitro regulation of adipocyte leptin expression and secretion in rainbow trout. Gen Comp Endocrinol 2015, 210, 114–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrow, G.E., S. M. Jones, and S.C. Nicol, Frozen embryos? Torpor during pregnancy in the Tasmanian short-beaked echidna Tachyglossus aculeatus setosus. General and Comparative Endocrinology 2017, 244, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weitten, M. , et al., Hormonal changes and energy substrate availability during the hibernation cycle of Syrian hamsters. Horm Behav 2013, 64, 611–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeeHong, P.A. , et al., Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) and chemical composition as measures of body composition of the short-beaked echidna (Tachyglossus aculeatus aculeatus). Australian Journal of Zoology 2019, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, C. , et al., Energetic consequences of seasonal breeding in female Japanese macaques (Macaca fuscata). Am J Phys Anthropol 2011, 146, 161–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Z.J. , et al., Seasonal changes of body mass and energy budget in striped hamsters: the role of leptin. Physiol Biochem Zool 2014, 87, 245–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spady, T.J. , et al., Leptin as a surrogate indicator of body fat in the American black bear. Ursus 2009, 20, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutton-Regester, K.J. , et al., Body fat and circulating leptin levels in the captive short-beaked echidna (Tachyglossus aculeatus). Journal of Comparative Physiology B 2024, 194, 457–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paolucci, M., M. Rocco, and E. Vachio, Leptin presence in plasma, liver and fat bodies in the lizard Podarcis sicula- fluctuations throughout the reproductive cycle. Life Sciences 2001, 69, 2399–2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nieminen, P. , et al., Endocrine response to fasting in the overwintering captive raccoon dog (Nyctereutes procyonoides). J Exp Zool A Comp Exp Biol 2004, 301, 919–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing, X., M. Yang, and D.H. Wang, The expression of leptin, hypothalamic neuropeptides and UCP1 before, during and after fattening in the Daurian ground squirrel (Spermophilus dauricus). Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol 2015, 184, 105–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filosa, S. , Biological and cytological aspects of the ovarian cycle in Lacerta s.sicula. Monitore Zoologico Italiano 1973, 7, 151–165. [Google Scholar]

- Seroussi, E. , et al., Identification of the long-sought leptin in chicken and duck: expression pattern of the highly GC-rich avian leptin fits an autocrine/Paracrine rather than endocrine function. Endocrinology 2016, 157, 737–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taouis, M. , et al., Cloning the chicken leptin gene. Gene 1998, 208, 239–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashwell, C.M. , et al., Hormonal regulation of leptin expression in broiler chickens. Am. J. Physiol. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 1999, 276, R226–R232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurokawa, T., S. Uji, and T. Suzuki, Identification of cDNA coding for a homologue to mammalian leptin from pufferfish, Takifugu rubripes. Peptides 2005, 26, 45–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuentes, E.N. , et al., Plasma leptin and growth hormone levels in the fine flounder (Paralichthys adspersus) increase gradually during fasting and decline rapidly after refeeding. General and Comparative Endocrinology 2012, 177, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Londraville, R.L. , et al., Comparative endocrinology of leptin: assessing function in a phylogenetic context. Gen Comp Endocrinol 2014, 203, 146–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortiz, R.M., C. E. Wade, and C.L. Ortiz, Effects of prolonged fasting on plasma cortisol and TH in postweaned northern elephant seal pups. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology 2001, 280, R790–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schradin, C. , et al., Leptin levels in free ranging striped mice (Rhabdomys pumilio) increase when food decreases: the ecological leptin hypothesis. Gen Comp Endocrinol 2014, 206, 139–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnould, J.P. , et al., Variation in plasma leptin levels in response to fasting in Antarctic fur seals (Arctocephalus gazella). J Comp Physiol B 2002, 172, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ahima, R.S. and J.S. Flier, Leptin. Review Annu Rev Physiol 2000, 62, 413–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nieminen, N. , et al., Plasma leptin and thyroxine of mink (Mustela vison) vary with gender, diet and subchronic exposure to PCBs. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology 2000, 127, 515–522. [Google Scholar]

| Author (year) | Taxa | Order | Species (Scientific name) | No. of animals | Sex | Evidence that leptin indicates adiposity? | Evidence of leptin decoupling or sensitivity? | Fat determination method (validated? Y/N) | Study duration | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soppela et al. (2008) | Mammal (eutherian) | Artiodactyla | Reindeer (Rangifer tarandus) | 16 | M | Yes | Yes | Body mass (N) | 4.5 months | ||||

| (Spady et al., 2009) | Mammal (eutherian) | Carnivora | American Black Bear (Ursus americanus) | 20 | M & F | Yes | No | Body fat % (NA) | 6 months | ||||

| Fuglei et al. (2004) | Mammal (Placental) | Carnivora | Arctic fox (Alopex lagopus) | 8 | M | No | No | Body mass (N) | 6 months | ||||

| Arnould et al. (2002) | Mammal (Placental) | Carnivora | Antarctic fur seal (Arctocephalus gazelle) | 28 | M & F | No | No | Body mass (Y) | 3-5 days | ||||

| (Nieminen et al., 2001) | Mammal (Placental) | Carnivora | Blue fox (Vulpes lagopus) | 11 | M & F | Yes | Yes | BMI (N) | 6 months | ||||

| Mustonen et al. (2005) | Mammal (Placental) | Carnivora | Blue fox (Vulpes lagopus) | 48 | M & F | Yes | Yes | BMI (Y) | 12 months | ||||

| Hissa et al. (1998) | Mammal (Placental) | Carnivora | European Brown bear (Ursus arctos arctos) | 6 | M & F | Yes | No | Fat reserves (NA) | 12 months | ||||

| Tauson et al. (2002) | Mammal (Placental) | Carnivora | Mink (Neovison vison) | 6 | F | Yes | No | Body mass (N) | 2 months | ||||

| Nieminen et al. (2000) | Mammal (eutherian) | Carnivora | Mink (Neovison vison) | 53 | F | No | No | BMI (N) | 5 months | ||||

| (Ortiz, Noren, et al., 2001) | Mammal (Placental) | Carnivora | Northern Elephant Seal (Mirounga angustirostris) | 40 | M & F | No | No | Fat mass (NA) | Unclear | ||||

| (Ortiz, Wade, et al., 2001) | Mammal (Placental) | Carnivora | Northern Elephant Seal (Mirounga angustirostris) | 15 | M & F | No | No | Body mass (N) | 7 weeks | ||||

| Kitao et al. (2011) | Mammal (Placental) | Carnivora | Racoon dog (Nyctereutes procyonoides) |

9 | M & F | Yes | Yes | Body fat % (NA) | 8 months | ||||

| Nieminen et al. (2004) | Mammal (Placental) | Carnivora | Racoon dog (Nyctereutes procyonoides) | 11 | M & F | Yes | Yes | BMI (N) | 6 months | ||||

| Nieminen et al. (2002) | Mammal (Placental) | Carnivora | Racoon dog (Nyctereutes procyonoides) | 33 | M & F | Yes | Yes | Body mass (Y) | 6 months | ||||

| Srivastava and Krishna (2008) | Mammal (Placental) | Chiroptera | Greater Asiatic yellow bat (Scotophilus heathi) | 120 | F | Yes | No | Fat Content & body mass (NA) | 12 months | ||||

| Banerjee et al. (2011) | Mammal (Placental) | Chiroptera | Indian short-nosed fruit bat (Cynopterus sphinx) | 72 | F | Yes | No | Body fat content & body mass (NA) | 12 months | ||||

| Banerjee et al. (2010) | Mammal (Placental) | Chiroptera | Indian short-nosed fruit bat (Cynopterus sphinx) | 76 | F | Yes | No | Body fat content & body mass (NA) | 10 months | ||||

| Widmaier et al. (1997) | Mammal (Placental) | Chiroptera | Little Brown Bat (Myotis lucifugus) | Unclear | F | No | No | Fat index (fat mass/lean dry mass) (NA) | 1 month | ||||

| Kronfeld-Schor et al. (2000) | Mammal (Placental) | Chiroptera | Little Brown Bat (Myotis lucifugus) | Unclear | F | Unclear | Yes | Body fat & body mass (NA) | 2 months | ||||

| Roy and Krishna (2010) | Mammal (Placental) | Chiroptera | Greater asiatic yellow bat (Scotophilus heathi) | Unclear | M | Yes | No | Body fat content & body mass (NA) | 12 months | ||||

| Srivastava and Krishna (2007) | Mammal (Placental) | Chiroptera | Greater asiatic yellow bat (Scotophilus heathi) | Unclear | F | Yes | No | Body fat content & body mass (NA) | 6 months | ||||

| Wang et al. (2006c) | Mammal (Placental) | Lagomorphs | Pikas (Ochotona curzoniae) | 40 | M & F | Yes | NR | Body fat content & body mass (NA) | 9 months | ||||

| Garcia et al. (2011) | Mammal (Placental) | Primate | Japanese macaques (Macaca fuscata) | 14 | F | No | No | BMI (N) | 2 months | ||||

| Whitten and Turner (2008) | Mammal (Placental) | Primate | Vervet Monkeys (Chlorocebus pygerythrus) | 116 | M & F | No | No | BMI (Y) | 12 months | ||||

| Li and Wang (2005) | Mammal (Placental) | Rodent | Brandt's Voles Microtis Brandti | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | No | Body fat content & body mass (NA) | 5 months | ||||

| Zhang and Wang (2006) | Mammal (Placental) | Rodent | Brandts voles (Microtis Brandti) | 16 | M & F | Yes | No | Body fat content & body mass (NA) | 4 weeks | ||||

| Zhang and Wang (2006) | Mammal (Placental) | Rodent | Brandts voles (Microtis Brandti) | 50 | M | Yes | No | Body fat content & body mass (NA) | 8 weeks | ||||

| Xing et al. (2015) | Mammal (Placental) | Rodent | Daurian Ground Squirrel (Spermophilus dauricus) | Unclear | F | Yes | Yes | Body fat content & body mass (NA) | 8 months | ||||

| Chen et al. (2012) | Mammal (Placental) | Rodent | Maximowiczi’s voles (Microtus maximowiczii) | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | No | Body fat content & body mass (NA) | 8 months | ||||

| Zhang and Wang (2007) | Mammal (Placental) | Rodent | Mongolian gerbils (Meriones unguiculatus) | 75 | M & F | Yes | Yes | Body fat content & body mass (NA) | 12 months | ||||

| Wang et al. (2006b) | Mammal (Placental) | Rodent | Root voles (Microtus oeconomu) | 10 | M & F | Yes | No | Body fat content & body mass (NA) | 10 months | ||||

| Wang et al. (2006a) | Mammal (Placental) | Rodent | Root voles (Microtus oeconomu) | 20 | M & F | Yes | No | Body fat content & body mass (NA) | 4 weeks | ||||

| Schradin et al. (2014) | Mammal (Placental) | Rodent | Striped mice (Rhabdomys pumilio) | Unclear | M & F | No | Yes | Body mass (N) | 12 months | ||||

| Zhao (2011) | Mammal (Placental) | Rodent | Striped hampsters (Cricetulus barabensis) | 64 | Unclear | No | No | Body fat content & body mass (NA) | 3 months | ||||

| Zhao et al. (2014) | Mammal (Placental) | Rodent | Striped hampsters (Cricetulus barabensis) | 52 | M | No | No | Body fat | 3 months | ||||

| Florant et al. (2004) | Mammal (Placental) | Rodent | Yellow bellied marmot (Marmota flaviventris) | 7 | M & F | Yes | Yes | Body fat & body mass (NA) | 12 months | ||||

| Sprent et al. (2012) | Mammal (prototherian) | Monotremata | Short beaked echidna (Tachyglossus aculeatus) | 34 | M & F | No | Yes | Lean body mass (N) | 36 months | ||||

| Yosefi et al. (2010) | Avian | Charadriiformes | Bar-tailed Godwit (Limosa lapponica) | Unclear | M & F | No | NA | Correlation of body fat mass, body mass & wing length (Y) | On arrival at landing site | ||||

| Yosefi et al. (2010) | Avian | Sphenisciformes | Adele penguin (Pygoscelis adeliae) | Unclear | M & F | No | NA | Isotope dilution approach (NA) | Pre-incubation and 45 days post egg laying | ||||

| Kordonowy et al. (2010) | Avian | Passiferormes | European starling (Sturnus vulgaris) | 57 | F | No | No | Body fat & body mass (NA | 4 months | ||||

| Quillfeldt et al. (2009) | Avian | Procellariiformes | Thin billed prion (Pachyptila belcheri) | Unclear | Unclear | No | No | Body condition (N) | 5 months | ||||

| Spanovich et al. (2006) | Reptile | Squamata | Eastern fence lizard (Sceloporus undulatus) | 60-180 | M & F | Unclear | Yes | Fat Stores (NA) | 12 months | ||||

| Paolucci et al. (2001) | Reptile | Squamata | Italian wall lizard (Podarcis sicula) | Unclear | F | Unclear | NA | Fat body mass (NA) | 9 months | ||||

| Froiland et al. (2012) | Fish | Salmoniformes | Arctic charr (Salvelinus alpinus) | 230 | M & F | No | No | Body fat & body mass (NA | 9 months | ||||

| (Salmeron et al., 2015) | Fish | Salmoniformes | Rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) | 92 | Unclear | No | No | Adipose Tissue mass (NA) | 8 WEEKS | ||||

|

Author (year) |

Species | Diet | Mature or immature | Long- or short-day breeder | Hibernate or migrate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soppela et al. (2008) | Reindeer | Herbivore | Immature | Long | No |

| Spady et al. (2009) | American Black Bear | Omnivore | Mature | Long | Yes |

| Fuglei et al. (2004) | Arctic fox | Carnivore | Mature | Long | No |

| Arnould et al. (2002) | Antarctic fur seal | Carnivore | Both | Long | No |

| Nieminen et al. (2001) | Blue fox | Omnivore | Mature | Short | No |

| Mustonen et al. (2005) | Blue fox | Omnivore | Mature | Short | No |

| Hissa et al. (1998) | European Brown bear | Omnivore | Mature | Long | Yes |

| Tauson et al. (2002) | Mink | Carnivore | Mature | Short | No |

| Nieminen et al. (2000) | Mink | Carnivore | Mature | Short | No |

| Ortiz et al. (2001) | Northern Elephant Seal | Carnivore | Immature | Short | No |

| Kitao et al. (2011) | Racoon dog | Omnivore | Mature | Long | Yes |

| Nieminen et al. (2004) | Racoon dog | Omnivore | Immature | Long | Yes |

| Nieminen et al. (2002) | Racoon dog | Omnivore | Immature | Long | Yes |

| Srivastava et al. (2008) | Greater Asiatic yellow bat | Insectivorous | Mature | Long | Yes |

| Banerjee et al. (2011) | Indian short-nosed fruit bat | Frugivore | Mature | Long | Yes |

| Banerjee et al. (2010) | Indian short-nosed fruit bat | Frugivore | Mature | Long | Yes |

| Widmaier et al. (1997) | Little Brown Bat | Insectivorous | Mature | Long | Yes |

| Townsend et al. (2008) | Little Brown Bat | Insectivorous | Mature | Long | Yes |

| Kronfeld-Schor et al. (2000) | Little Brown Bat | Insectivore | Mature | Long | Yes |

| Roy et al. (2010) | Greater asiatic yellow bat | Insectivorous | Mature | Long | Yes |

| Srivastava et al. (2007) | Greater asiatic yellow bat | Insectivorous | Mature | Long | Yes |

| Wang et al. (2006) | Pikas | Herbivore | Mature | Long | No |

| Garcia et al. (2011) | Japanese macaques | Omnivore | Mature | Short | No |

| Garcia et al. (2010) | Japanese macaques | Omnivore | Mature | Short | No |

| Whitten et al. (2008) | Vervet Monkeys | Herbivore | Mature | Long | No |

| Li et al. (2005) | Brandt's Voles | Omnivore | Unclear | Long | No |

| Zhang et al. (2006) | Brandts voles | Omnivore | Mature | Long | No |

| Xing et al. (2015) | Daurian Ground Squirrel | Herbivore | Mature | Long | Yes |

| Chen et al. (2012) | Maximowiczi’s voles | Herbivore | Mature | Long | No |

| Zhang et al. (2007) | Mongolian gerbils | Herbivore | Mature | Long | No |

| Wang et al. (2006) | Root voles | Omnivore | Mature | Long | No |

| Wang et al. (2006) | Root voles | Omnivore | Mature | Long | No |

| Schradin, et al. (2014) | Striped mice | Omnivore | Mature | Long | No |

| Zhao et al. (2011) | Striped hamsters | Omnivore | Mature | Long | Yes |

| Zhao et al. (2014) | Striped hamsters | Omnivore | Mature | Long | Yes |

| Florant et al. (2004) | Yellow bellied marmot | Herbivore | Mature | Long | Yes |

| Sprent et al. (2012) | Short beaked echidna | Insectivorous | Mature | Short | Yes |

| Yosefi et al. (2010) | Bar-tailed Godwit | Omnivore | Mature | Unclear | Yes |

| Yosefi et al. (2010) | Adele penguin | Carnivore | Mature | Long | Yes |

| Kordonowy et al. (2010) | European starlings | Omnivore | Immature | Long | Yes |

| Quillfeldt et al. (2009) | Thin billed prions | Carnivore | Immature | Long | Yes |

| Spanovich, et al. (2006) | Eastern fence lizard | Insectivorous | Mature | Long | Yes |

| Paolucci et al. (2001) | Italian wall lizard | Insectivorous | Mature | Long | Yes |

| Froiland et al. (2012) | Arctic charr | Insectivore | Immature | Long | No |

| Salmeron, et al. (2015) | Rainbow trout | Carnivore | Mature | Long | No |

| Does leptin signal adiposity? | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | No. species in group | Yes (%) | No (%) | Unclear (%) |

| Order | ||||

| Carnivora | 8 | 4 (50) | 3 (37) | 1 (12) |

| Chiprotera | 4 | 3 (75) | 1 (25) | 0 |

| Rodent | 8 | 5 (63) | 3 (37) | 0 |

| Primate | 4 | 2 (50) | 2 (50) | 0 |

| Diet | ||||

| Herbivore | 6 | 4 (67) | 2 (33) | 0 |

| Insectivore | 2 | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | 0 |

| Carnivore | 4 | 0 | 3 (75) | 1 (25) |

| Omnivore | 9 | 6 (67) | 3 (33) | 0 |

| Hibernating species | 9 | 7 (78) | 2 (22) | 0 |

| Timing of breeding season | ||||

| Long-day | 19 | 13 (68) | 6 (32) | 0 |

| Short-day | 5 | 1 (20) | 3 (60) | 1(20) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).