Submitted:

15 July 2025

Posted:

17 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

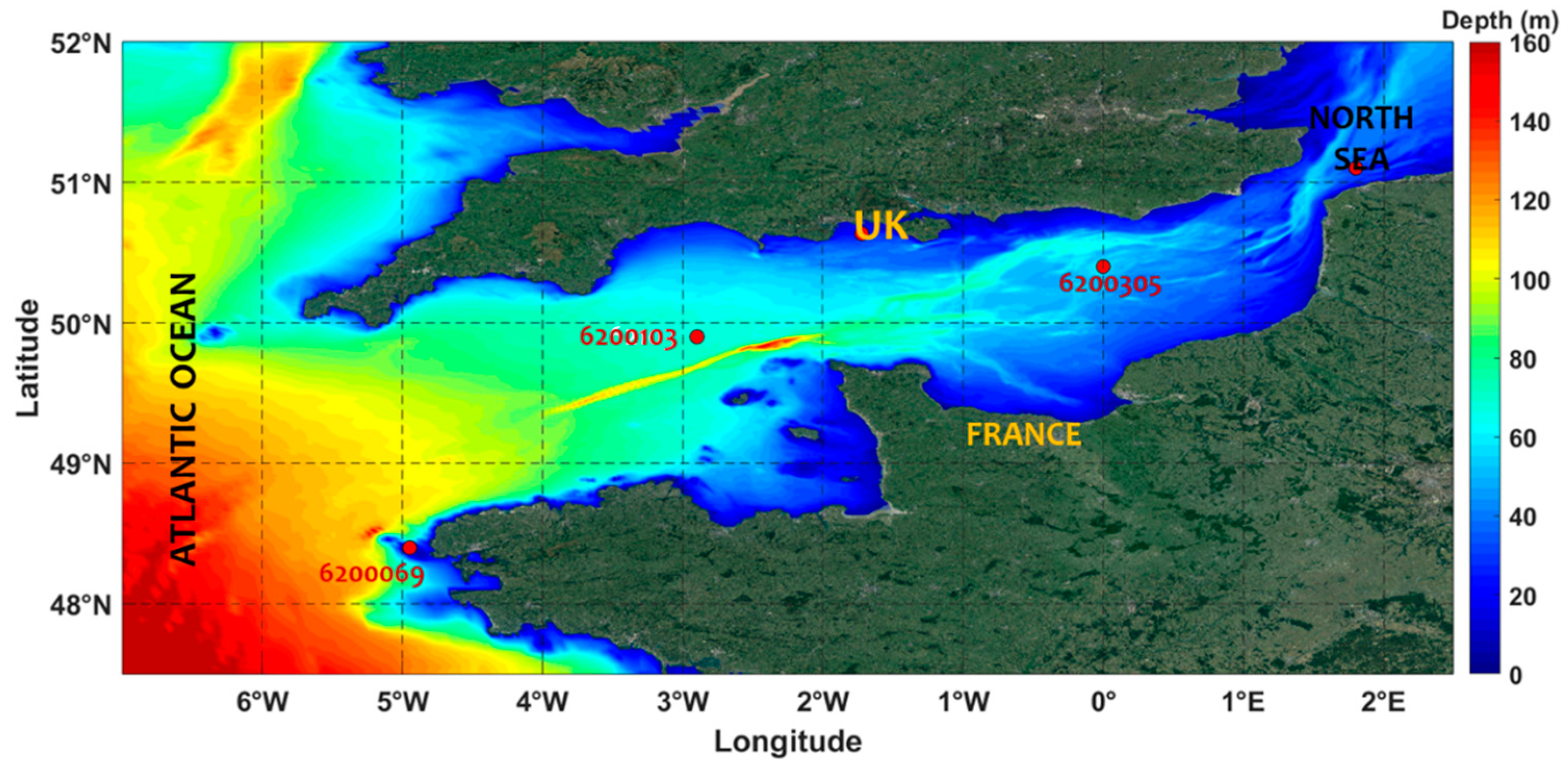

2.1. In-Situ Observations

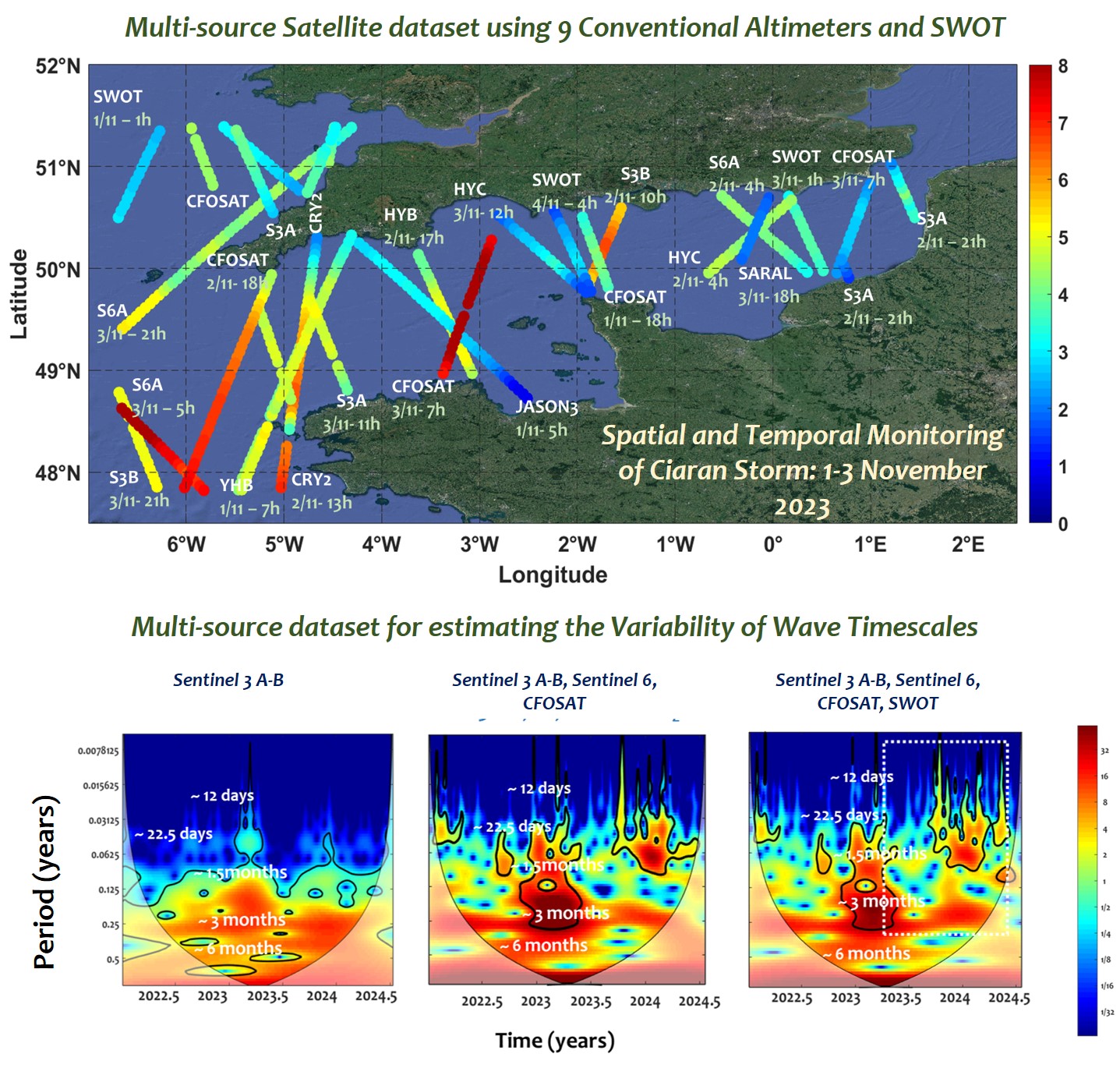

2.2. Altimetry Observations: SWOT and Conventional Missions

2.2.1. SWOT Altimetry Data

2.2.2. Conventional Altimetry Data

2.3. Methodology

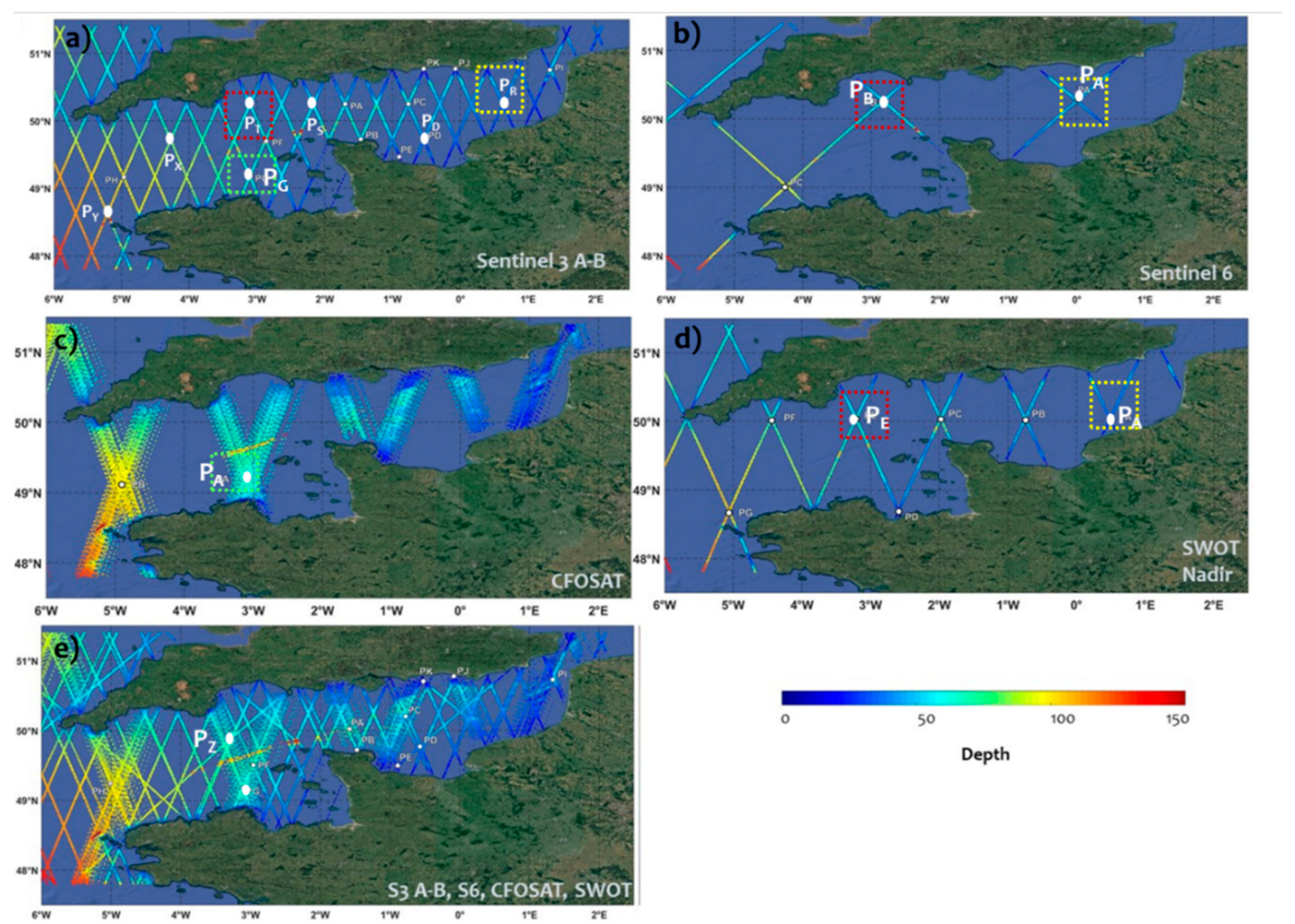

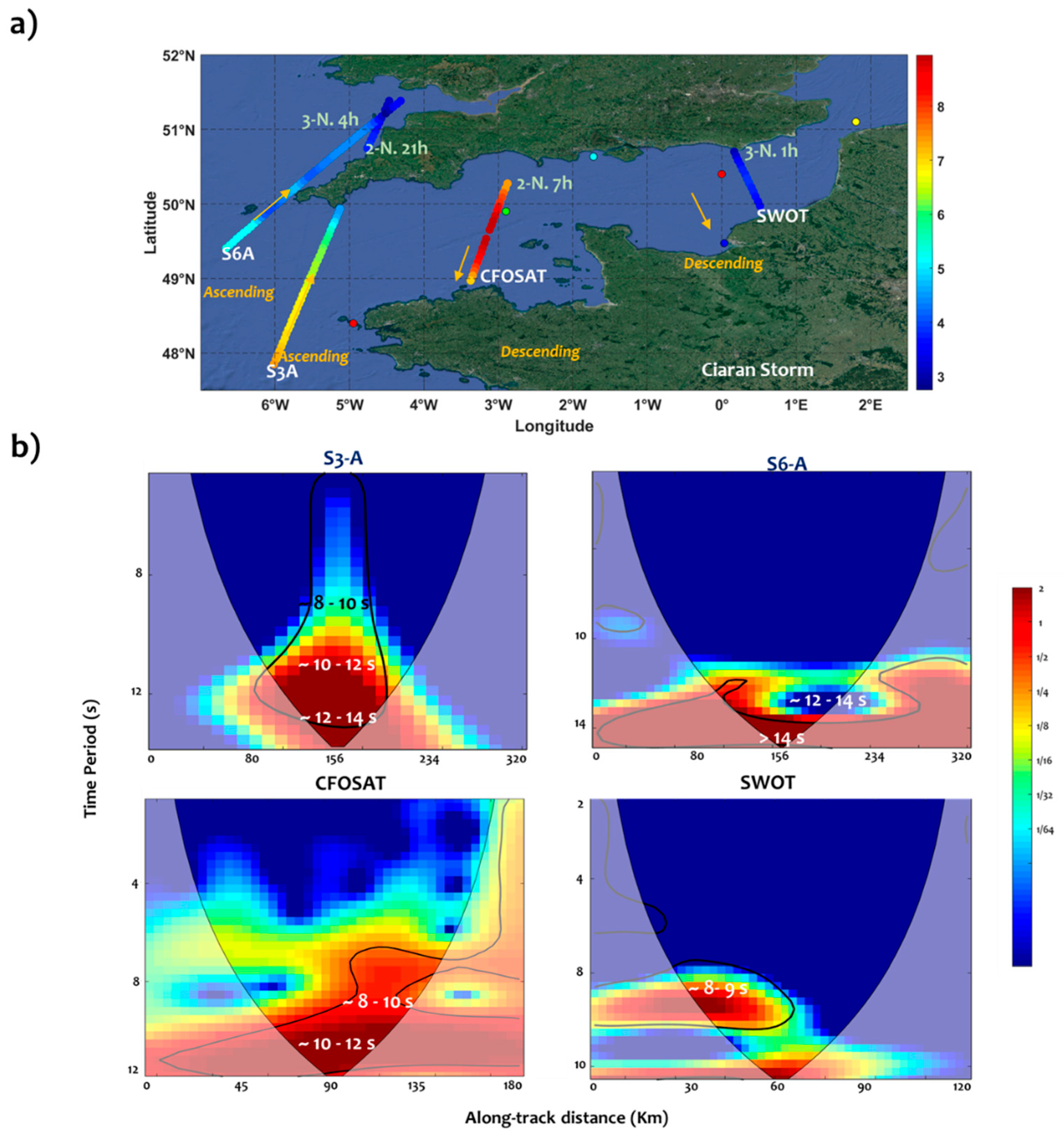

2.3.1. Multi-Source Altimetry Coverage in the English Channel

2.3.2. Spectral Analysis of Altimetry Data

3. Results

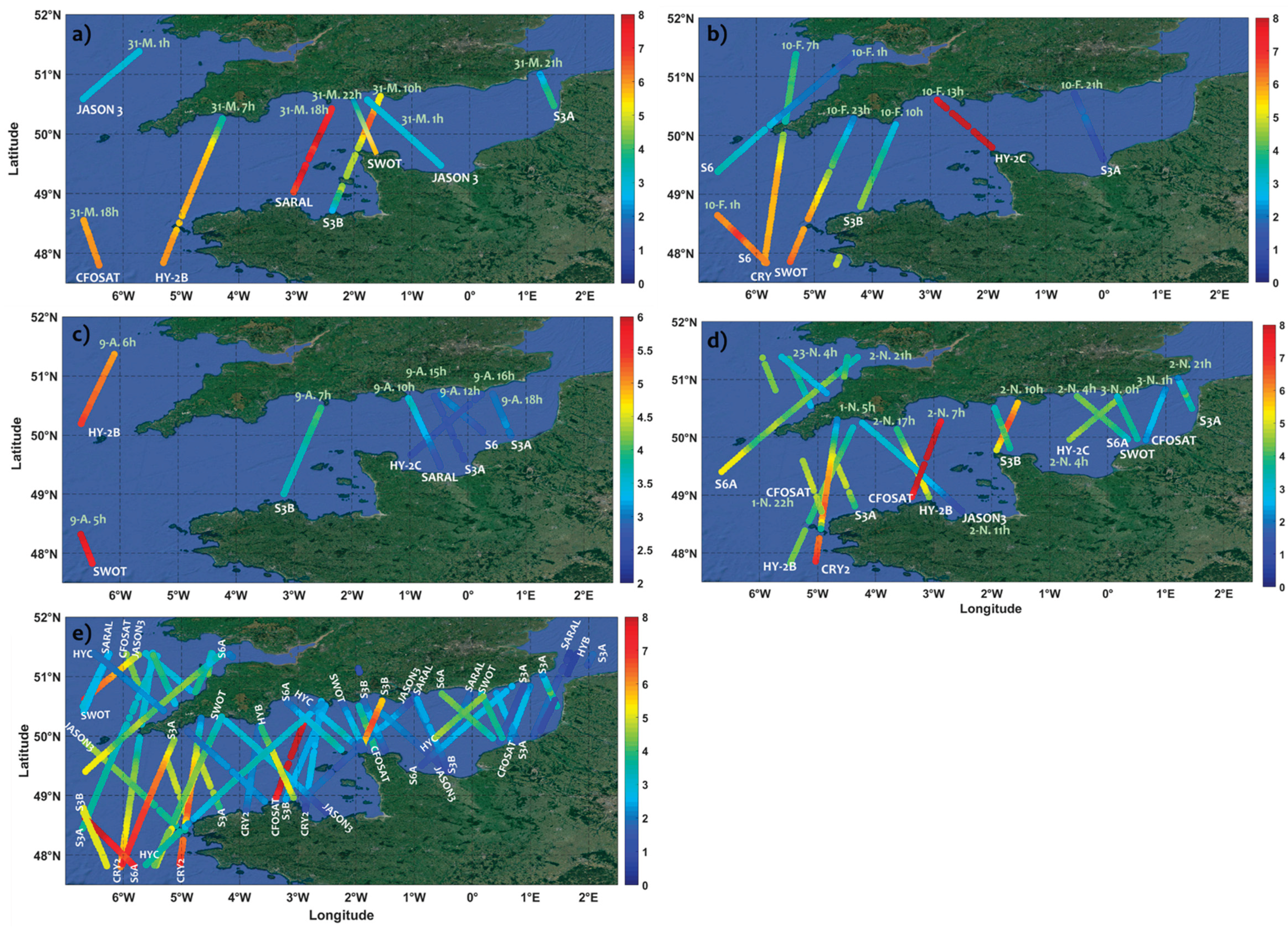

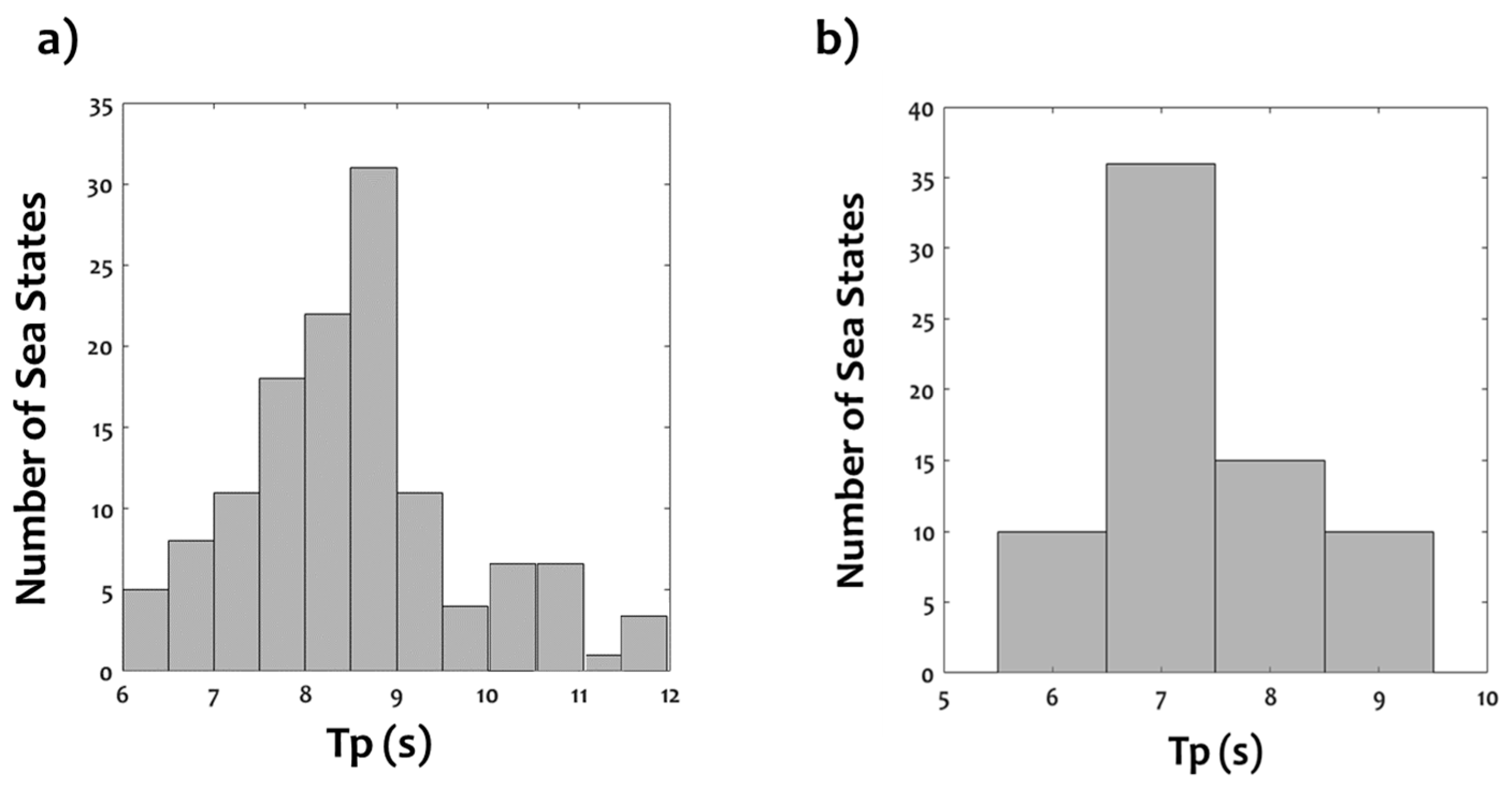

3.1. Monitoring of Waves During Storm Events

3.2. Time-Evolution of Nearshore and Coastal Waves

3.3. Spatial-Evolution of Wave Features Along the Altimeter Tracks

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nicholls, R. J., and C. Small. Improved estimates of coastal population and exposure to hazards released; Eos Trans. AGU, 83(28), 301–305; 2002. [CrossRef]

- Switzer, A. D. Coastal hazards: storms and tsunamis; Coast. Environ. Glob. Change,2017; pp 104-127.

- Masselink, G., & Gehrels, R. Coastal Environments and Global Change, 2015 Wiley-Blackwell. [CrossRef]

- Kreibich, H., Van Loon A.F., Schröter, K., Ward, P.J., Mazzoleni, M., Sairam, N., Abeshu, G.W., Agafonova, S., AghaKouchak, A., Aksoy, H., Alvarez-Garreton, C., A. The challenge of unprecedented floods and droughts in risk management. Nature, 2022; Aug;608(7921):80-86. Epub 2022 Aug 3. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ji, T., Guosheng, L., Zhang, Y. Observing storm surges in China's coastal areas by integrating multi-source satellite altimeters, Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci., 2019; Volume 225, 106224, ISSN 0272-7714; 2019. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0272771419300253).

- Dodet, G., Castelle, B., Masselink, G., Scott, T., Davidson, M., Floc'h, F., Jackson, D., & Suanez, S. Beach recovery from extreme storm activity during the 2013–14 winter along the Atlantic coast of Europe. Earth Surf. Process. Landf., 2019, 44(1), 393-401. [CrossRef]

- Laignel, B., Vignudelli, S., Almar, R. et al. Observation of the Coastal Areas, Estuaries and Deltas from Space; Surv Geophys 44, 2023, 1309–1356 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, S., Kolahchi, A., Ablain, M., Adusumilli, S., Aich Bhowmick, S., …. al., Altimetry for the future : Building on 25 years of progress, Adv. Space Res., 2021, Volume 68, Issue 2, Pages 319-363, ISSN 0273-1177. [CrossRef]

- Bonnefond, P., Verron, J., Aublanc, J., Babu, K. N., Bergé-Nguyen, M., Cancet, M.,... & Watson, C. The benefits of the Ka-band as evidenced from the SARAL/AltiKa altimetric mission: Quality assessment and unique characteristics of AltiKa data. J. Remote Sens., 2018, 10(1), 83. [CrossRef]

- Quartly, G. D., Nencioli, F., Raynal, M., Bonnefond, P., Nilo Garcia, P., Garcia-Mondéjar, A., ... & Lucas, B. The roles of the S3MPC: Monitoring, validation and evolution of Sentinel-3 altimetry observations. J. Remote Sens., 2020, 12(11), 1763. [CrossRef]

- Idžanović, M., Ophaug, V., & Andersen, O. B. Coastal sea level from CryoSat-2 SARIn altimetry in Norway. Adv. Space Res., 2018, 62(6), 1344-1357.

- Han, G. Altimeter surveys, coastal tides, and shelf circulation. Encyclopedia of Coastal Science, 2027, eds C. W. Finkl and C. Makowski (Berlin: Springer Science & Business Media). [CrossRef]

- Schlembach, F., Passaro, M., Dettmering, D., Bidlot, J., Seitz, F.. Interference-sensitive coastal SAR altimetry retracking strategy for measuring significant wave height, Remote Sens. Environ. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Benveniste, J., Mandea, M., Melet, A., Ferrier, P. Earth observations for coastal hazards monitoring and international services: a European perspective. Surv. Geophys., 2020, 41(6):1185–1208. [CrossRef]

- Mears, C. A., and F. J. Wentz. A Satellite-Derived Lower-Tropospheric Atmospheric Temperature Dataset Using an Optimized Adjustment for Diurnal Effects. J. Climate, 2017, 30, 7695–7718. [CrossRef]

- Morrow, R., Fu, L. L., Ardhuin,, F., Benkiran, M., Chapron, M., et al. Global Observations of Fine-Scale Ocean Surface Topography With the Surface Water and Ocean Topography (SWOT) Mission. Front. mar. sci., 2017, 6, ⟨10.3389/fmars.2019.00232⟩. ⟨hal-02194574⟩.

- Fu, L.âL., Pavelsky, T., Cretaux, J.âF., Morrow, R., Farrar, J. T., Vaze, P., et al. The Surface Water and Ocean Topography Mission: A breakthrough in radar remote sensing of the ocean and land surface water. Geophys. Res. Lett., 2024, 51, e2023GL107652. [CrossRef]

- Ardhuin, F., Molero, B., Bohé, A., Nouguier, F., Collard, et al. Phase-Resolved Swells Across Ocean Basins in SWOT Altimetry Data: Revealing Centimeter Scale Wave Heights Including Coastal Reflection. Geophys. Res. Lett., 2024, Science from the Surface Water and Ocean Topograp hy Satellite Mission, 51 (16), pp.e2024GL109658. ff10.1029/2024GL109658ff.

- Bohé, A. , Chen, A., Dubois, P., Fore, A., & Molero, B., Peral, E., Raynal, M., Stiles, Bryan, Ardhuin, F., Hay, A., Legresy, B., Lenain, L., Bôas, A. Measuring Significant Wave Height Fields in Two Dimensions at Kilometric Scales With SWOT. IEEE Trans. Geosci., Remote Sens., 2025, PP. 1-1. 10.1109/TGRS.2025.3551605.

- Mendoza, E. T., Jimenez, J. A., and Mateo, J.: A coastal storms intensity scale for the Catalan sea (NW Mediterranean). Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci., 2024, 11, 2453–2462. [CrossRef]

- Castelle, B., Marieu, V., Bujan, S., Splintre, K., Robinet, A., Senechal, N., Ferreira, S.. Impact of the Winter 2013-2014 Series of Severe Western Europe Storms on a Double-Barred Sandy Coast: Beach and Dune Erosion and Megacusp Embayments. Geomorphology, 2015, 238, 135-148. [CrossRef]

- López Solano, C., Turki, E.I., Mendoza, E.T. et al. Hydrodynamic modelling for simulating nearshore waves and sea levels: classification of extreme events from the English Channel to the Normandy coasts. Nat Hazards, 2024, 120, 13951–13973. [CrossRef]

- PL D-105502, “SWOT Algorithm Theoretical Basis Document: Level 2 KaRIn Low Rate Sea Surface Height -L2_LR_SSH Science Algorithm Software,”.

- EMODnet Bathymetry Portal. Available online: https://www.emodnet-bathymetry.eu/data-products (accessed on 4 September 2023).

- Turki, I., Massei, N., Laignel, B.. Linking Sea Level Dynamic and Exceptional Events to Large-scale Atmospheric Circulation Variability: Case of Seine Bay, France. Oceanologia, 2019, 61 (3) (2019), pp. 321-330. [CrossRef]

- Turki, I., Massei, N., Laignel, B., Shafiei, H. Effects of Global Climate Oscillations on Intermonthly to Interannual Variability of Sea levels along the English Channel Coasts (NW France). Oceanologia, 2020,Volume 62, Issue 2, 2020, Pages 226-242, ISSN 0078-3234. [CrossRef]

- Labat, D. Recent advances in wavelet analyses: Part 1. A review of concepts. J. Hydrol., 2005, 314 (1–4) (2005), pp. 275-288. [CrossRef]

- Torrence, C., Compo, G.P. A practical guide to wavelet analysis B. Am. Meterol. Soc., 1998, 79 , pp. 61-78. [CrossRef]

- Cazenave, A., Palanisamy, H., Ablain, M. Contemporary sea level changes from satellite altimetry: What have we learned? What are the new challenges?, Adv Space Res, 2018, Volume 62, Issue 7, 2018, Pages 1639-1653. ISSN 0273-1177. [CrossRef]

- Peng, F., Deng, X. Validation of Sentinel-3A SAR mode sea level anomalies around the Australian coastal region. Remote Sens. Environ., 2020, Volume 237, 2020, 111548. [CrossRef]

- De Carlo, M., & Ardhuin, F. Along-track resolution and uncertainty of altimeter-derived wave height and sea level: Re-defining the significant wave height in extreme storm. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans, 2014, 129, e2023JC020832. [CrossRef]

- Rieu, P., Moreau, T., Cadier, E., Raynal, M., Clerc, S., Donlon, C., & Maraldi, C.. Exploiting the Sentinel-3 tandem phase dataset and azimuth oversampling to better characterize the sensitivity of SAR altimeter sea surface height to long ocean waves. Adv Space Res,, 2021, 67(1), 253–265. [CrossRef]

- Rieu, P., Moreau, T., Raynal, M., Cadier, E., Thibaut, P., Borde, F., et al. First SAR altimeter tandem phase: A unique opportunity to better characterize open ocean SAR altimetry signals with unfocused and focused processing. Ocean Surface Topography Science Team, 21–25 October 2019.

- Jianjun K., Runyu M., Yiting C., Hongli, F., Comparative analysis of significant wave height between a new Southern Ocean buoy and satellite altimeter. Atmos. Ocean. Sci. Lett., 2021, Volume 14, Issue 5, 2021, 100044, ISSN 1674-2834. [CrossRef]

- Skandrani, C., Lefevre, J. M., Queffeulou, P. Impact of Multisatellite Altimeter Data Assimilation on Wave Analysis and Forecast. Mar. Geod., 2004, 27(3–4), 511–533; 200. [CrossRef]

- Seemanth, M., Remya, P.G., Aich Bhowmick, S., Sharma, R., Nair, T.M.B., Kumar, R., Chakraborty, A. Implementation of altimeter data assimilation on a regional wave forecasting system and its impact on wave and swell surge forecast in the Indian Ocean, Ocean Eng., 2021,Volume 237; 2021; 109585, ISSN 0029-8018. [CrossRef]

- Chaigneau, A. A., Law-Chune, S., Melet, A., Voldoire, A., Reffray, G., and Aouf, L. Impact of sea level changes on future wave conditions along the coasts of western Europe, Ocean Sci., 2023, 19, 1123–1143. [CrossRef]

- Moreau, T., Tran, N., Tison, C., Le Gac, S., Boy, F., & Boy, F. Impact of long ocean waves on wave height retrieval from SAR altimetry data. Adv. Space Res., 2018, 62(6), 1434–1444. [CrossRef]

- Reale, F., Carratelli, E., Laiz, I., Di Leo, A., & Fenoglio-Marc, L. Wave orbital velocity effects on radar doppler altimeter for sea monitoring. J. Mar. Sci. Eng, 2020, 8(6). [CrossRef]

| STORM | Duration | Hs (max), Tm | E storm (m2/h) |

| Mathis 31/03 (4 am) – 01/04 (6 am) - 2023 |

|||

| 26 hours | 5 m, 9 s | 360.42 | |

|

Noah 12/04 (1 pm) – 13/04 (5 am) - 2023 |

16 hours |

4.7 m, 9 s | 249.44 |

|

Ciaran 01/11 (10 pm) – 03/11 (4 am) |

30 hours |

5,8 m, 11 s |

530.75 |

|

Karlotta 10/02 (10 am) – 11/02 (7 am) |

21 hours |

5,27 m, 8 s |

517.93 |

|

Pierrick 09/04 (10 am) – 09/04 (3 pm) |

13 hours | 4,8 m, 8 s | 173.1 |

| Satellite Altimetry | Agency | Mission Duration | Altitude (km) | Inclination (°) | Repeat Cycle (days) |

| Saral | ISRO/CNES | 2023.02 | 800 | 98.55 | 35 |

| Cryosat-2 | ESA | 2010.04 | 717 | 92 | 30 |

| Jason-3 | NASA/CNES | 2016.01 | 1336 | 66 | 10 |

| Sentinel-3A/B | ESA | 2016.02/2018.04 | 814.5 | 98.65 | 27 |

| Sentinel-6A | ESA | 2020.11 | 1336 | 66 | 10 |

| Hai Yang-2B | CNSA | 2018.10 | 973 | 99.3 | 14 |

| CFOSAT | CNES/CNSA | 2018.10 | 500 | 97 | 13 |

| SWOT | NASA/CNES | 2022.12 | 890 | 77.6 | 21 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).