1. Introduction

Tissue engineering (TE) is defined as the combination of cells, engineering materials, and biochemical factors to restore, maintain, or enhance biological functions, thereby contributing to the regeneration of damaged tissues and organs (Rondón et al., 2025). A key component in this field is the scaffold—three-dimensional structures that provide physical support and a favorable environment for cells to adhere, proliferate, differentiate, and form new tissue. Fabricating these scaffolds requires biomaterials that meet essential properties such as biocompatibility, biodegradability, porosity, and adequate mechanical strength.

On the other hand, cellulose—recognized as the main structural component of plant cell walls—is one of the most abundant natural polymers found in nature. Its structure and properties have been widely used to drive significant advances in the biomedical field. However, its chemical modification can be more complex than other polysaccharides, representing both a challenge and an advantage for its use as a biomaterial (Muhammad et al., 2024). Derivatives such as cellulose ethers and esters are among the most common excipients in oral pharmaceutical formulations (Brady et al., 2017). Moreover, their biocompatibility and biodegradability are key qualities that support their biomedical application.

Among these derivatives, Hydroxyethyl Cellulose (HEC) stands out as one of the most promising. This polymer has drawn significant attention due to its physicochemical properties, including water solubility, adjustable viscosity, and its ability to form stable gels. These characteristics make it versatile and especially useful in tissue engineering applications. HEC has shown great potential in fabricating scaffolds, cell-supporting matrices, and controlled drug delivery systems, contributing to developing more effective and safer solutions in regenerative medicine. However, despite its potential, we still need to deepen our understanding of its composition, mechanisms of action, and specific biomedical applications. Therefore, this research aims to thoroughly analyze and evaluate the functional properties of HEC as a biomaterial for scaffold fabrication and its applicability in tissue engineering (Naeem et al., 2023).

2. Methodology

The methodology used in the development of this research is a comprehensive documentary-exploratory review, structured into the following stages:

Information Gathering: Academic databases such as ScienceDirect, PubMed, Scopus, Google Scholar, and ResearchGate were consulted using key search terms including “Hydroxyethyl Cellulose”, “Scaffolds”, “Tissue Engineering”, and “Tissue Regeneration”. The search focused on publications from the years 2014 to 2025.

Source Selection and Organization: Mendeley's reference management software was used to classify and organize the selected documents based on criteria such as composition, properties, mechanisms of action, and biomedical applications. Priority was given to relevant studies and high-impact systematic reviews.

Thematic Structuring: The gathered information was organized according to predefined subtopics, allowing for a clear assessment of each source's relevance within the proposed analytical framework.

Critical Evaluation: The data collected underwent a reflective and reasonable analysis to establish solid conclusions that support the study’s objectives.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. What is HEC?

Hydroxyethyl Cellulose (HEC) is a cellulose ether derived from plants' cell walls, such as cotton or wood, produced through a reaction with ethylene oxide. It is a non-ionic, non-toxic, water-soluble, biocompatible, and biodegradable polysaccharide whose physicochemical properties make it a versatile polymer with applications in food, cosmetic, pharmaceutical, and packaging industries (Zhang et al., 2022). Various products primarily use it as a thickening, binding, and stabilizing agent.

Structurally, HEC comprises glucose units linked by special bonds known as β-1,4-glycosidic linkages (

Figure 1). It is obtained by chemically modifying natural cellulose—usually sourced from wood or cotton—through a process known as ethoxylation. In this process, hydroxyethyl groups (–CH₂CH₂OH) are added to the cellulose using ethylene oxide. This compound, ethylene oxide, can be produced from natural materials such as ethanol, glycerol, or sorbitol, allowing HEC to be considered a renewable or "bio-based" product (Michaelis et al., 2025).

Hydroxyethyl Cellulose (HEC) production begins with a crucial step: the activation of cellulose using a sodium hydroxide solution. This treatment causes the cellulose fibers to swell and become more reactive, facilitating the subsequent stages of the process. Once the cellulose is alkalized, it reacts with ethylene oxide, a compound that binds to the hydroxyl groups of the cellulose, forming ether linkages. This reaction, known as etherification, incorporates hydroxyethyl groups, which enhance the material’s water solubility and functional properties. To complete the process, the product is neutralized with an acid—typically acetic acid—to stabilize it and adjust its pH. An essential aspect of this process is that the amount of ethylene oxide used can be carefully controlled, allowing regulation of the polymer’s degree of substitution (DS). This parameter is critical, as it directly affects the final product's viscosity and suitability for various applications (Abdel-Halim, 2014).

3.1.1. Physical and Chemical Properties of HEC

Structurally, the hydroxyethyl group is attached to the oxygen atom of the hydroxyl group through an ether bond, forming a branched structure at the glucose ring's C2, C3, or C6 positions. The result is a molecule with a main cellulose backbone that retains its linear form but features hydroxyethylated side branches. This structure makes HEC highly soluble in water, forming transparent and stable solutions. It exhibits tunable rheological behavior depending on its molecular weight and degree of substitution (

Table 1). Additionally, since it is non-ionic, HEC is compatible with other active substances and does not interfere with sensitive ingredients (National Center for Biotechnology Information, 2025).

Overall, the physical and chemical properties of HEC provide a clear understanding of its behavior at both the molecular and functional levels. These characteristics help to better assess its performance in various environments, particularly in aqueous and biological systems. Furthermore, they directly influence their effectiveness in specific biomedical applications, such as scaffolds for tissue engineering.

3.1.2. General Applications of HEC

Currently, excipients play a significant role in the pharmaceutical field, as they work alongside active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) to ensure the effectiveness and stability of medications. Although considered inactive components, excipients are essential for guaranteeing drug stability, controlled release, and efficient administration. Properly selecting an excipient is critical to ensure that the final product is safe, effective, and has good bioavailability.

Hydroxyethyl Cellulose (HEC) stands out due to its functional properties and compliance with the standards established by the United States Pharmacopeia/National Formulary (USP/NF) and the European Pharmacopoeia (Ph. Eur.). It has also been recognized for its effectiveness as a rheology modifier in sugar-free oral liquid formulations, improving the product’s physical stability, texture, and sensory acceptability while reducing the risk of sedimentation and issues associated with traditional sugar-based thickeners (Kumar et al., 2023; Arai & Shikata, 2020).

The inappropriate choice of excipients can compromise the stability of a formulation and may even cause toxic effects. This highlights the importance of sourcing HEC from manufacturers that offer high-quality and reliable production processes.

The following properties qualify Hydroxyethyl Cellulose as a high-standard excipient in the pharmaceutical industry, as documented in recent studies:

Flexible or swellable at high temperatures (135–140 °C).

Water-soluble due to hydroxyethyl groups that increase polarity and allow extensive hydrogen bonding, enabling solubility in cold and hot water without turbidity points.

Viscosity can be finely tuned depending on concentration and molecular weight, allowing precise control based on the formulation type.

Non-ionic nature, offering high compatibility with anionic ingredients, salts, cosolvents, and other polymers.

Non-toxic, non-reactive with APIs, non-glycogenic, and non-carcinogenic, making it suitable for pediatric, geriatric, and diabetic populations (Kumar et al., 2023).

Pharmaceutical Applications

Although HEC does not have direct pharmacological activity, it plays critical roles in drug formulation and delivery:

Solid dosage forms (e.g., tablets): In oral tablets, HEC acts as a binder, coating agent, and controlled-release agent. It helps tablets maintain their shape, disintegrate appropriately, and release the active ingredient gradually. For instance, it has been used in vitamin B12 tablets to prolong their release.

Oral liquid suspensions: Due to its adjustable viscosity and compatibility with various substances, HEC is ideal as a thickener in sugar-free syrups. These are especially beneficial for pediatric or diabetic patients, improving texture and stability without adding glycogenic agents.

Injectable drugs: HEC can be used to create injectable systems that prolong the presence of the drug in the body. This reduces the frequency of administration, which is particularly advantageous in hospital settings and long-term treatments (Kumar et al., 2023).

Ophthalmic and Dermatological Applications

Eye drops: HEC is a mucoadhesive agent in ophthalmic formulations that prolongs the drug's contact time on the ocular surface. This enhances therapeutic efficacy and patient comfort (Kumar et al., 2023).

Dermatological creams and gels: HEC is widely used as a base in creams and gels due to its thickening, stabilizing, and absorption-enhancing properties. Its biocompatibility makes it suitable for sensitive formulations, such as those for burns or reactive skin (Kumar et al., 2023).

Veterinary and Food Applications

Veterinary use: HEC is an excipient in animal formulations, including healing gels and suspensions. It has also been applied as a stabilizer in pest control products that do not harm beneficial insects like bees (Kumar et al., 2023).

Food industry use: In the food industry, HEC is a stabilizer and thickener in products such as ice cream and refrigerated dairy beverages, helping prevent crystallization and improve final texture (Kumar et al., 2023).

3.2. Tissue Engineering

Tissue engineering (TE) has emerged as a modern and promising biomedical engineering branch that addresses critical challenges in regenerative medicine. Its primary goal is to create artificial tissues and organs capable of replacing damaged or diseased ones, thereby improving patients’ quality of life and life expectancy. This multidisciplinary field combines engineering, biology, and materials science knowledge to design tissues that mimic natural structures. Unlike mechanical devices such as artificial hearts or ventricular pumps (already in clinical use), tissue engineering seeks to create functional biological organs using living cells and biomaterials that resemble the extracellular matrix.

The importance of this discipline lies in the global shortage of organs available for transplant. Through TE, it could be possible to manufacture personalized biological organs, reducing waiting lists and decreasing dependency on human donors (Rondón et al., 2024). The core idea behind TE is that the human body can heal itself naturally. This regenerative capacity depends on the type of tissues or organ involved, the level of damage, the degree of functional loss, and the number of tissues affected. However, due to significant advances in medical technology, this natural healing process has improved dramatically (Roldán et al., 2016).

In recent years, there has been a global surge in research focused on developing tissues and organs for various human body systems, including:

Cardiovascular: artificial cardiac muscle, blood vessels, valves, and bioartificial hearts.

Musculoskeletal: bone, cartilage, tendons, and muscle tissue.

Respiratory system: artificial trachea and lung tissue.

Urinary system: kidneys, bladders, ureters, and urethras.

Digestive system: liver, pancreas, intestines, and esophagus.

Skin and the central nervous system are also active areas of research.

One of the most valuable methods in TE is 3D artificial tissue fabrication, which represents a significant advancement in the field. While specific techniques vary depending on the type of tissue or organ being developed, many follow a series of common steps, refined through research conducted in universities and research centers around the world (Rondón et al., 2025):

Cell source: The process begins with selecting cells—the “raw material” of artificial tissue. These cells are isolated, purified, expanded, and analyzed for suitability. Cells may come from animal or human sources, including stem cells (either embryonic or adult, such as those derived from bone marrow). It’s also essential to determine whether the cells are autologous (from the same patient) or allogeneic (from a donor).

Biomaterial synthesis: Biomaterials are used to mimic the body’s natural extracellular matrix. They serve as a scaffold that supports cell growth and tissue formation. These materials can include polymers, ceramics, or metals, chosen based on the type of tissue being engineered.

Genetic manipulation: Before seeding cells onto the scaffold, specific strategies can be applied to enhance regeneration. One strategy involves modifying growth factors—natural proteins that promote cell division, growth, and differentiation. Thanks to advances in bioengineering, these proteins can now be tailored for longer activity in the body, controlled release, and improved attachment to scaffold materials (Ren et al., 2020).

Scaffold cellularization: At this stage, selected cells are seeded onto the biomaterial scaffold. They aim to adhere properly, distribute evenly, and begin functioning like a real tissue. This step is crucial, as it determines whether the tissue will develop in an organized and functional manner.

Sensor technology: Throughout tissue development, sensors are integrated to monitor progress. These sensors measure cell growth, cellular interactions, and tissue function. This information allows researchers to adjust environmental conditions to optimize the final product.

Bioreactor use: The human body constantly exposes tissues to stimuli such as electrical impulses, movement, or fluid pressure. Bioreactors are used to simulate these conditions and promote proper tissue maturation. These devices replicate the natural physiological environment, encouraging tissue development and functionality.

Vascularization: To function within the body, capillaries must nourish the artificial tissue. This step involves integrating blood vessels into the tissue, allowing oxygen and nutrient transport to keep the tissue alive and functional.

In vivo evaluation: Finally, once the tissue is complete, it is tested in animal models or clinical trials. The aim is to determine whether it can effectively replace, repair, or enhance the function of a damaged organ or tissue in a living organism (Rondón et al., 2025).

3.2.1. Applications of Hydroxyethyl Cellulose (HEC) in Tissue Engineering

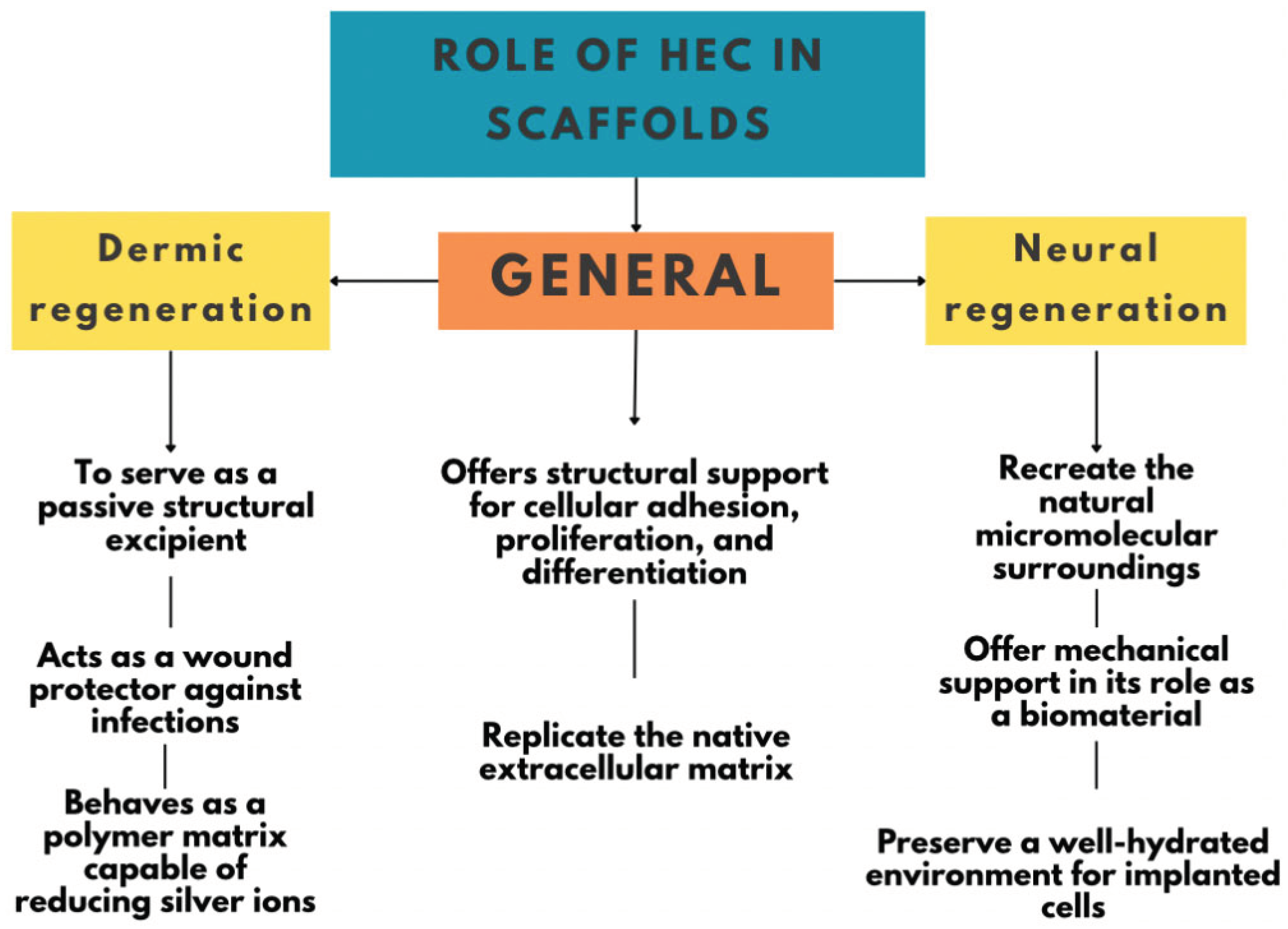

Thanks to its unique characteristics, particularly its hydrophilic and non-toxic nature, Hydroxyethyl Cellulose (HEC) is an ideal polymer for designing three-dimensional scaffolds that mimic the natural extracellular matrix. These scaffolds provide structural support for cell adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation. Its adaptable rheological behavior and ease of processing allow it to be fabricated in various formats, such as gels or sponges, broadening its applicability to soft tissues and those requiring higher mechanical strength (Zulkifli et al., 2014).

One specific area where HEC-based scaffolds have been studied is in nerve regeneration, where tissue engineering has gained increasing importance due to the limitations associated with repairing injuries in the nervous system, particularly in complex regions such as the trigeminal nerve (

Table 2). In response to this challenge, HEC-based scaffolds have shown promising results due to their ability to simulate the natural microcellular environment, providing both structural support and favorable conditions for long-term cell culture (Mabrouk et al., 2022).

A recent study on the biocompatibility of HEC/glycine scaffolds doped with ruthenium oxide (RuO₂) has further advanced this approach. This research highlights that HEC not only fulfills the fundamental criteria for effective scaffolds, such as porosity, cellular compatibility, and water retention capacity, but can also be enhanced by incorporating bioactive additives. The study emphasizes that successful artificial nerve tissue restoration depends on several factors: the mechanical stability of the biomaterial, its biocompatibility, and the integration of cellular signals such as bioactive molecules or progenitor cells. In this context, HEC is a suitable biomaterial due to its ability to form stable polymeric networks and hydrophilic nature, which helps maintain optimal hydration conditions for implanted cells (Mabrouk et al., 2022).

In addition, a more recent investigation explored HEC-based scaffolds incorporating silver nanoparticles (AgNPs), aimed at applications in skin regeneration. These scaffolds were developed through a green synthesis method without toxic agents, using HEC as the polymer matrix and the silver-reducing agent. The result was the formation of highly porous structures with pore sizes ideal for cell migration and proliferation, high water retention capacity, and inherent antimicrobial properties provided by the AgNPs (Zulkifli et al., 2017).

This second study underscores that HEC/AgNP scaffolds offer a biocompatible and highly functional platform capable of protecting wounds from infection, promoting healing, and maintaining a moist, favorable environment. Their demonstrated thermal stability, interconnected porosity, and low in vitro cytotoxicity reinforce their potential for use in dermal repair therapies and other soft tissue engineering applications.

Both findings demonstrate that HEC is not merely a passive structural excipient but a versatile and adaptable platform in tissue engineering. It can integrate with bioactive components to meet specific needs in contexts such as nerve and skin regeneration. Its ability to be modified and functionalized makes it a strategic tool for developing advanced regenerative therapies (Khodadadi Yazdi et al., 2024).

Figure 2

4. Future Perspectives

In recent years, Hydroxyethyl Cellulose (HEC) has seen growing prominence in biomedical engineering, not only due to its favorable physicochemical properties, but also because of its adaptability to emerging technologies. Its biocompatibility, ability to form hydrogels, and tunable rheological behavior make it an ideal candidate for future applications such as 3D bioprinting, scaffold development in tissue engineering, drug delivery systems, and broader clinical use.

These advancements are made possible by evolving biomaterial processing techniques, integrating bioactive systems like growth factors, and increasing demand for sustainable and efficient solutions in the clinical field. The potential of HEC has been further reinforced by progress in biomedical manufacturing technologies and the development of functional, clinically applicable biomaterials.

Within the advancing landscape of bio-fabrication, HEC and other similar hydrogels are emerging as key materials in developing intelligent biomedical structures through 3D printing—and more recently, 4D printing. This innovative technology adds a temporal dimension to printed structures, allowing materials such as shape-memory hydrogels to transform in response to stimuli like temperature, pH, or humidity (Appuhamillage et al., 2024). The integration of materials like HEC with advanced 4D printing technologies is expected to enable the design of personalized medical devices that can actively respond to physiological conditions. This includes implants that adapt to anatomical changes, wound dressings that release drugs in response to specific biological signals, and printed organs that mimic real tissue functions (Appuhamillage et al., 2024).

Recent research has also highlighted HEC's potential as a structural agent in the formation of nanomaterials. A notable example is the study by He et al. (2024), in which HEC facilitated the assembly of gold atoms into flat and orderly structures without toxic chemicals. This breakthrough illustrates that HEC is useful in regenerative medicine and in developing sensors, microelectronic devices, and stimuli-responsive technologies, positioning it as a material with significant promise for the future.

5. Conclusions

Tissue engineering represents one of the most significant advances in contemporary regenerative medicine, offering solutions to restore, replace, or enhance damaged tissues and organs. In this study, developing and applying suitable biomaterials for fabricating three-dimensional scaffolds has been a scientific priority. Hydroxyethyl Cellulose (HEC) is one of the most promising natural polymers. Throughout this theoretical review, the potential of HEC as a central component in tissue engineering strategies has been explored, both for its essential properties and its remarkable versatility in being modified and adapted for various therapeutic purposes.

The analysis revealed that HEC is not merely a cellulose derivative, but a functional biomaterial with desirable characteristics: it is water-soluble, biocompatible, and capable of forming porous structures that mimic the extracellular matrix, facilitating cell adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation. Most notably, HEC demonstrates a remarkable capacity for adaptation. Thanks to its chemical structure, it can be functionalized or combined with other compounds—such as ruthenium oxide, silver nanoparticles, or bioactive proteins—to suit different tissue repair contexts. For example, it can be used in nervous tissue regeneration or dermal wound healing, depending on the therapeutic approach. This flexibility makes HEC a highly effective biomaterial capable of adapting to each specific tissue type's architecture, stiffness, and biological needs.

Finally, HEC not only meets the basic requirements of biomaterials for regenerative medicine but also has the potential to adapt to a wide range of clinical needs, reinforcing its value within the field of biomedical engineering. Suppose research continues to enhance its functionality through integration with other bioactive components. In that case, HEC is likely to play a key role in developing more effective, safer, and accessible regenerative therapies for various tissue types.

Funding

This research was funded by the Biomedical Engineering Department, Polytechnic University of Puerto Rico, PR 00918 USA.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abdel Halim, E.S. Chemical Modification of Cellulose Extracted from Sugarcane Bagasse: Preparation of Hydroxyethyl Cellulose. Arab. J. Chem. 2014, 7, 362–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appuhamillage, G.A.; Ambagaspitiya, S.S.; Dassanayake, R.S.; Wijenayake, A. 3D and 4D Printing of Biomedical Materials: Current Trends, Challenges, and Future Outlook. Explor. Med. 2024, 5, 17–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arai, K.; Shikata, T. Hydration/Dehydration Behavior of Hydroxyethyl Cellulose Ether in Aqueous Solution. Molecules 2020, 25, 4726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aravamudhan, A.; Ramos, D.M.; Nada, A.; Kumbar, S.G. Natural Polymers: Polysaccharides and Their Derivatives for Biomedical Applications. In Natural and Synthetic Biomedical Polymers; Kumbar, S.G., Laurencin, C.T., Deng, M., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 67–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, J.E.; Dürig, T.; Lee, P.I.; Li, J.-X. Methyl Cellulose. In ScienceDirect Topics; 2017. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/agricultural-and-biological-sciences/methyl-cellulose.

- Gañán, P.; Zuluaga, R.; Castro, C.; Restrepo Osorio, A.; Velásquez Cock, J.; Osorio, M.; Molina, C. Celulosa: Un Polímero de Siempre con Mucho Futuro. Simp. Nac. Biopolímeros, 2017; 2256 1013, 1–4. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/319361290_Celulosa_un_polimero_de_siempre_con_mucho_futuro.

- He, L.; Shen, B.; Ren, Y.; Mao, H.; Yin, J.; Dai, W.; Zhao, S.; Yang, H. Hydroxyethylcellulose Directed Synthesis of Gold Microplates with Hydrogen Peroxide in an Aqueous Phase. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 8789–8796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khodadadi Yazdi, M.; Seidi, F.; Hejna, A.; Zarrintaj, P.; Rabiee, N.; Kucinska-Lipka, J.; Bencherif, S.A. Tailor-Made Polysaccharides for Biomedical Applications. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2024, 7, 4193–4230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, V.J.; Dantuluri, A.K.; Liu, Y.; Durig, T. Hydroxyethylcellulose as a Versatile Viscosity Modifier in the Development of Sugar Free, Elegant Oral Liquid Formulations. Int. J. Curr. Res. Chem. Pharm. Sci. 2023, 10, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabrouk, M.; Ismail, E.; Beherei, H.H.; Abu Bakr, N.; et al. Biocompatibility of Hydroxyethyl Cellulose/Glycine/RuO₂ Composite Scaffolds for Neural Like Cells. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2022, 283, 125978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelis, J.U.; Kiese, S.; Hofmann, S.; Lohner, T.; Eisner, P. Elastohydrodynamic Lubrication of Aqueous Hydroxyethyl Cellulose–Glycerol Lubricants. Tribol. Int. 2025, 191, 110563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, D.R.A.; Zaman, M.Z.; Ariyantoro, A.R. Sustainable Materials and Infrastructures for the Food Industry. In Sustainable Materials for Transitional and Alternative Food Production; Haghi, A.K., Gutiérrez, T.J., Thomas, S., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, A.; Yu, C.; Wang, X.; Peng, M.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y. Hydroxyethyl Cellulose Based Hydrogels as Controlled Release Carriers for Amorphous Solid Dispersion of Bioactive Components of Radix Paeonia Alba. Molecules 2023, 28, 7320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. Hydroxyethyl Cellulose (CID=24846132). PubChem Compound Summary, National Library of Medicine, 2025. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/24846132.

- Ren, X.; Zhao, M.; Lash, B.; Martino, M.M.; Julier, Z. Growth Factor Engineering Strategies for Regenerative Medicine Applications. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 7, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reproductive BioMedicine Online. Hydroxyethyl Cellulose. In ScienceDirect Topics: Medicine and Dentistry. Elsevier. 2014. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/medicine-and-dentistry/hydroxyethyl-cellulose.

- Roldán Vasco, S.; Vargas Isaza, C.A.; Mejía Suaza, M.L.; Zapata Giraldo, J. Ingeniería de Tejidos y Aplicaciones; Fondo Editorial ITM: Medellín, Colombia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rondón, J.; Muñiz, C.; Lugo, C.; Farinas Coronado, W.; Gonzalez Lizardo, A. Bioethics in Biomedical Engineering. Ciencia e Ingeniería 2024, 45, 159–168. [Google Scholar]

- Rondón, J.; Sánchez-Martínez, V.; Lugo, C.; Gonzalez-Lizardo, A. Tissue Engineering: Advancements, Challenges and Future Perspectives. Ciencia e Ingeniería 2025, 46. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Guo, H.; Luo, W.; Chen, G.; Xiao, N.; Xiao, G.; Liu, C. Development of Functional Hydroxyethyl Cellulose Based Composite Films for Food Packaging Applications. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 989893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zulkifli, F.H.; Hussain, F.S.J.; Zeyohannes, S.S.; Abdull Rasad, M.S.B.; Yusuff, M.M. A Facile Synthesis Method of Hydroxyethyl Cellulose–Silver Nanoparticle Scaffolds for Skin Tissue Engineering Applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2017, 79, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zulkifli, F.H.; Jahir Hussain, F.S.; Abdull Rasad, M.S.B.; Mohd Yusoff, M. Nanostructured Materials from Hydroxyethyl Cellulose for Skin Tissue Engineering. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 114, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).